Abstract

Influenza virus infections of carnivores—primarily in dogs and in large and small cats—have been repeatedly observed to be caused by a number of direct spillovers of avian viruses or in infections by human or swine viruses. In addition, there have also been prolonged epizootics of an H3N8 equine influenza virus in dogs starting around 1999, of an H3N2 avian influenza virus in domestic dog populations in Asia and in the United States that started around 2004, and an outbreak of an avian H7N2 influenza virus among cats in an animal shelter in the United States in 2016. The impact of influenza viruses in domesticated companion animals and their zoonotic or panzootic potential poses significant questions for veterinary and human health.

There are as many as 900 million domesticated dogs and 600 million domesticated cats worldwide, with most existing as household pets and others forming semidomesticated populations that include “village dogs” or urban feral cats that live adjacent to human populations. The number of companion dogs has increased rapidly since the beginning of the twentieth century, and there are now nearly 75 million in the United States and 43 million in Western Europe, with growing numbers in the Eastern Hemisphere. Fully domesticated companion cats exist in similar numbers to dogs in the United States and in many other parts of the world. Most companion animals are housed in small numbers in residential homes and many have no or only brief and infrequent contact with other members of the same species, so that transmission of influenza is inefficient. However, some domestic dogs and cats live in high-contact networks in urban social locales—in day or boarding kennels or in animal shelters—and some dogs are housed in dense populations for meat production. Under such conditions, the contact networks among dogs and cats allow sustained transmission of some influenza virus lineages if they enter those populations, resulting in sustained outbreaks and epidemic or panzootic potential. The close contacts between dogs and cats with humans also raises further questions about the zoonotic potential of their influenza viruses, as well as about the likelihood of infection of dogs or cats by human influenza viruses.

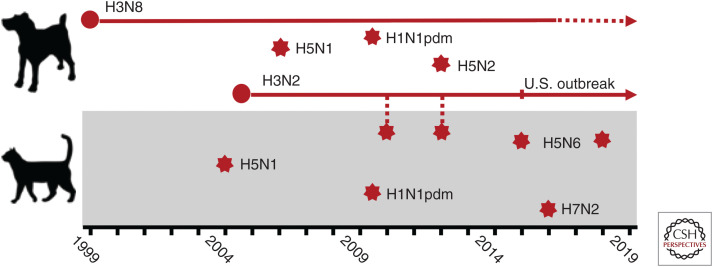

Here, we review our understanding to date of influenza virus in canine and feline lineages, which includes both established outbreaks in dogs and occasional spillover events in both dogs and cats (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of major canine outbreaks as well as canine and feline spillover events since 1999. Outbreaks of equine-origin H3N8 and avian-origin H3N2 in dogs have been sustained in dog populations, with a major contraction (or possible resolution) of H3N8. Major spillover subtypes include H5N1, H5N2, H5N6, H7N2, and H1N1pdm. Dog-to-cat cross-species transmissions have been observed with canine influenza virus (CIV) H3N2 in Korea.

CANINE INFLUENZA VIRUSES

Domesticated dogs have lived with human populations for several millennia, potentially creating a risk of transmission risk of pathogens from humans to dogs and the reverse. Past surveys have noted relatively low but consistent levels of seroconversion of dogs to human influenza strains. Given the likely high levels of exposure of dogs to those viruses in human homes, this indicates that they have a low level of susceptibility to human influenza viruses. However, there are no clear historical records of outbreaks or epidemics of influenza in dogs, and dogs were generally not considered to be natural hosts to influenza viruses before the identification of H3N8 canine influenza virus (CIV) in Florida in 2004.

H3N8 Canine and Equine Influenza Viruses

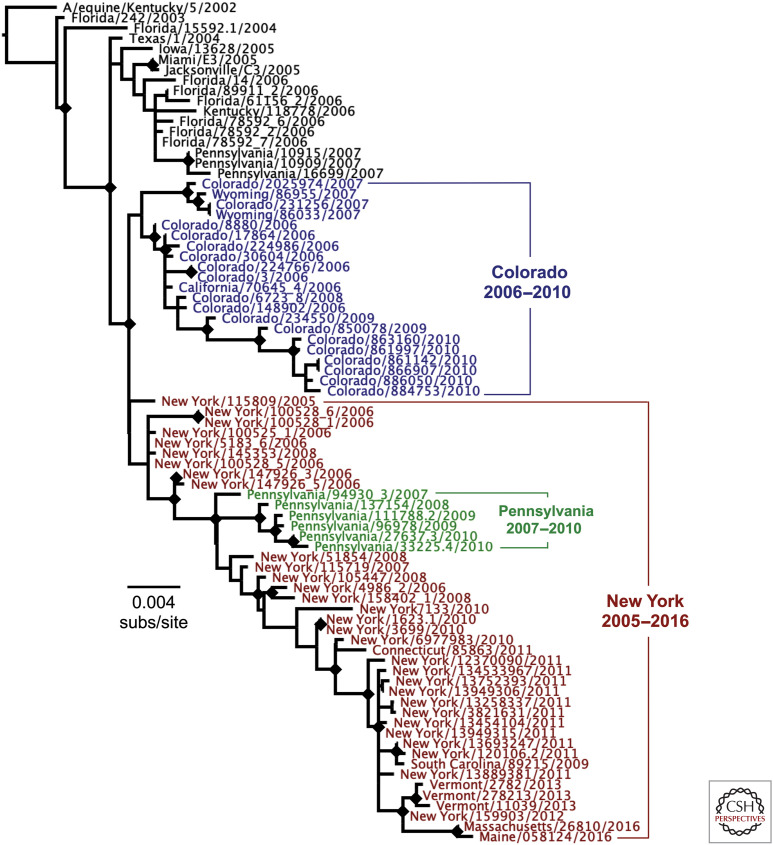

The H3N8 CIV was derived from the H3N8 equine influenza virus (EIV), being first identified in 2004 in greyhounds in Florida at a training facility (Crawford et al. 2005). Subsequent sequence analysis showed that the canine virus arose from the transfer of a single Florida 1 clade EIV into dogs. That virus had been infecting the greyhounds since ∼1999, and infected dogs, including greyhounds, had carried the virus to many parts of the United States to cause localized outbreaks (Payungporn et al. 2008). Following recognition of that CIV, the outbreak was largely controlled in greyhounds and in most areas of the United States, and the virus continued to circulate in Colorado and in the Northeastern United States, including New York and Pennsylvania, but with additional outbreaks in other nearby states (Hayward et al. 2010). It appears that the virus circulated in the Philadelphia area for a few years between 2009 and 2012, resulting in a separate genetic clade of the virus developing (Fig. 2). The virus circulated in Colorado until ∼2010–2012, when it appears to have died out. The virus continued to circulate in the Northeastern states until ∼2016, apparently persisting among dogs in animal shelters in New York for several years and spreading to other locations along with dogs from those shelters (Fig. 2) (Dalziel et al. 2014; Pecoraro et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Evolutionary relationships among the hemagglutinins (HAs) of the H3N8 canine influenza virus (CIV) since the emergence of that virus in dogs. All available HA sequences were used in the analysis and were outgroup-rooted on a 2002 H3N8 equine influenza virus HA sequence (strain A/equine/Kentucky/5/2002). Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the maximum likelihood (ML) method available in PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel 2003), using a general time-reversible (GTR) substitution model, gamma-distrusted (Γ) rate variation among sites, and bootstrap resampling (100 replicates). Diamonds at nodes indicate bootstrap support in ≥70 out of 100 replicates. Regional lineages were seen to develop in Colorado (blue) and in New York (red) and nearby states in the United States, as well as a sublineage that arose around Philadelphia (green) between 2007 and 2010.

Although sequence analyses show that a single H3N8 EIV initiated the epidemic in the United States, there have been other reported spillovers of EIV into dogs, including a limited outbreak among foxhounds in the United Kingdom in 2002 (Newton et al. 2007; Daly et al. 2008) and infection of individual dogs in Australia during an outbreak in that country in 2007 (Kirkland et al. 2010; Crispe et al. 2011). Experimental studies show that EIV isolates have the ability to replicate in dogs when those are housed in close proximity to infected horses or after experimental inoculation (Yamanaka et al. 2009, 2010; Pecoraro et al. 2013). In contrast, isolates of the H3N8 CIV do not appear to efficiently infect horses even when directly challenged, and they also did not infect equine tracheal cells in culture (Yamanaka et al. 2012; Gonzalez et al. 2014; Feng et al. 2015). There is also no evidence of transmission of CIV H3N8 from infected dogs to their human companions or contacts (Krueger et al. 2014).

H3N2 Canine Influenza Virus in Asia and the United States

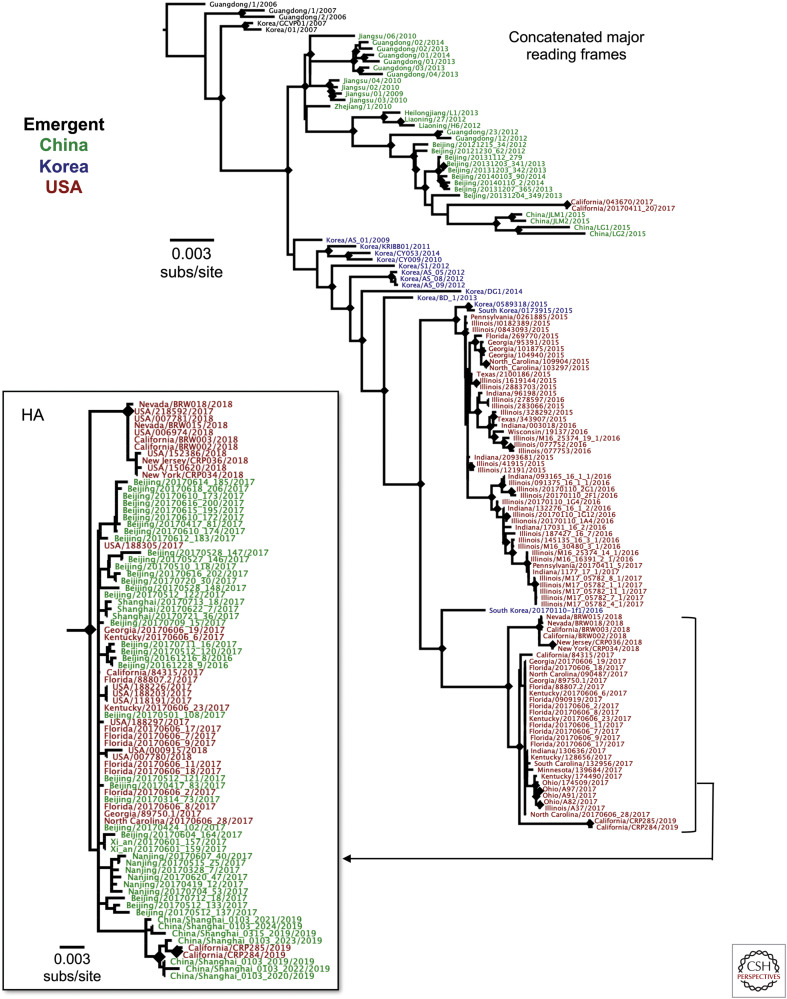

The H3N2 CIV (Fig. 3) appears to have been directly derived from an avian influenza virus that was introduced into dogs in China or Korea ∼2004–2005 (Zhu et al. 2015). A direct ancestral virus has not been identified in birds, but the closest known sequences of each genome segment fall among avian viruses circulating in Asia. The virus was found among dogs in both China and South Korea by 2006, and it appears that the virus then spread endemically within each country. Other outbreaks of canine disease have been reported in Thailand, but those do not appear to have resulted in sustained epidemics (Bunpapong et al. 2014). The H3N2 CIV was first reported in the United States in early 2015, when there was an outbreak of respiratory disease in dogs in Chicago and in nearby areas of Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin. A second outbreak that was seeded from that initial outbreak occurred in Georgia and nearby states, but that appears to have died out within a few months. Analysis of the 2015 H3N2 CIV from the United States showed that it was introduced into the United States from South Korea, likely along with dogs rescued from meat production farms in that country (Voorhees et al. 2017). Some later outbreaks of H3N2 CIV in the United States and in Canada also appear to involve introductions of the virus from either Korea or China, and those spread for varying distances over the periods of the outbreaks (Fig. 3B) (Weese et al. 2019). The epizoology of the H3N2 CIV involved introduction of viruses into an area (city or region) to cause a localized outbreak, which generally died out in a few weeks, likely once populations of dogs in kennels or animal shelters had been infected and had become immune. The main exception to this pattern appears to have been in the Chicago area, where the virus continued to spread at low levels for a number of years after being introduced in 2015 (Newbury et al. 2016; Voorhees et al. 2018) although possibly dying out in 2018 or 2019. In some cases, viruses introduced into various regions of the United States from Asia were detected early after introduction of the infected dogs, and subsequent spread was prevented by quarantine or other infection-control procedures. The epidemiology of the virus in Asia is not well-described, but likely involves viral persistence in both animal shelters and kennels, as well as in farms where dogs are raised for meat production (Lee et al. 2009; Su et al. 2013a).

Figure 3.

Evolutionary relationships among H3N2 canine influenza virus (CIV) in China, Korea, and the United States, showing how the viruses spread among the different regions. An analysis of available full genome sequences, in which the eight genome segment open reading frames are concatenated. The tree is outgroup-rooted on the earliest available H3N2 CIV sequence in the database (A/canine/Guangdong/1/2006). Just eight of 149 genome sequences contained reassortant viruses, as determined by RDP4 analysis (Martin et al. 2015), and were removed before analysis. Phylogenetic relationships were determined using the maximum likelihood (ML) method available in PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel 2003), using a general time-reversible (GTR) substitution model, gamma-distrusted (Γ) rate variation among sites, and bootstrap resampling (100 replicates). Diamonds at nodes indicate bootstrap support in ≥70 of 100 replicates. Colors indicate countries of origin from Korea (blue), China (green), or the United States (red). An analysis of the hemagglutinin (HA) segment sequences (inset) available for 2017–2019 isolates of H3N2 CIV show the close relationships between those viruses in the United States and China.

Pathogenesis of the CIV Infections

The H3N8 and H3N2 CIVs cause similar diseases in dogs, with the main symptoms being the result of upper respiratory tract infection (Castleman et al. 2010; Song et al. 2011a; Pulit-Penaloza et al. 2017). In naive animals the viruses reach peak titers by 3–4 d after exposure, and highest titers of virus are found in the nose, with significant amounts of virus also being found in pharyngeal secretions and the trachea. The dogs generally develop a fever of ∼39.5°C, and many develop a cough; only a very small proportion develop pneumonia or more severe disease (Lee et al. 2011). Mortality is <1% in most cases. Viral shedding peaks around days 3–4 after infection and decreases rapidly by around days 5–7, although transient low-level shedding of the H3N2 CIV has been reported up until around day 20 (Song et al. 2011a; Newbury et al. 2016).

SPILLOVERS INTO DOGS AND CATS

Domesticated pet dogs and cats are frequently exposed to human and other influenza viruses and may become infected on occasions, although in most cases there appears to be no onward transmission. Semidomesticated animals may also come in contact with infected birds, either in dense markets or farms, in some cases taking in avian influenza viruses by ingestion. In addition, as domesticated dogs and cats may be housed in close proximity within houses and animal shelters, cross-transmission may occur between those species, as has been seen in feline cases of CIV H3N2 lineages (Song et al. 2011b; Jeoung et al. 2013).

Human Influenza Virus Spillover into Dogs and Cats

Both dogs and cats were found to be susceptible to human influenza strains during surveys conducted during the 1970s. Serological surveys showed that dog populations had low percentages of animals that had seroconverted for human influenza viruses in the United States, Europe, and South or East Asia, including H3N2, H1N1, and influenza B viruses (Nikitin et al. 1972; Fyson et al. 1975; Kilbourne and Kehoe 1975; Romváry et al. 1975; Chang et al. 1976; Madhavan and Agarwal 1976; Onta et al. 1978; Houser and Heuschele 1980). Experimental inoculation of dogs with human H3N2 (A/Hong Kong/1/68) also resulted in infection, shed virus, and seroconversion, but with no obvious clinical signs (Paniker and Nair 1972). Following the 2009 human pandemic H1N1 (H1N1pdm), a number of cases of human influenza infection in dogs were documented (Dundon et al. 2010; Piccirillo et al. 2010; Seiler et al. 2010; Said et al. 2011; Damiani et al. 2012; Yin et al. 2014; Su et al. 2019; Tangwangvivat et al. 2019). Some reassortants between the human H1N1pdm and CIV H3N2 were reported from dogs in South Korea, indicating that there were mixed infections and some onward transmission of those viruses, although only one example of each reassortant has been reported (Song et al. 2012; Na et al. 2015). Full genome sequencing of more than 100 H3N8 or H3N2 CIVs collected from dogs in the United States revealed no reassortants with any other viruses or between those two CIV variants (Hayward et al. 2010; Voorhees et al. 2018).

A domestic cat was found to be infected with avian influenza in a case in the 1940s and experimental inoculation resulted in infection and disease (Nakamura and Iwasa 1942); surveys of cats for seroconversion to human IAVs in the 1960s and 1970s showed a low level of positive results, indicating some previous infections (Paniker and Nair 1970; Fyson et al. 1975; Romváry et al. 1975; Onta et al. 1978), although experimental inoculation confirmed that cats were susceptible to human strains (Paniker and Nair 1972). Surveillance following the emergence of 2009 H1N1pdm showed a number of infections in cats (including fatalities) for that virus (Löhr et al. 2010; Pingret et al. 2010; Sponseller et al. 2010; Campagnolo et al. 2011; Fiorentini et al. 2011; McCullers et al. 2011; Su et al. 2013b; Pigott et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Knight et al. 2016; Tangwangvivat et al. 2019), and experimental inoculations also confirmed susceptibility of cats to that strain (Bao et al. 2010; van den Brand et al. 2010). Cats are generally at low seroprevalence for other human influenza strains (Ali et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2015b; Ibrahim et al. 2016).

In a recent survey, dogs in Southern China presenting with respiratory disease to veterinary clinics were tested for the presence of influenza viruses, revealing the presence of a variety of different viruses containing combinations of canine, avian, swine, and human influenza viruses (Chen et al. 2018). Those included H1N1pdm, swine North American triple reassortant H3N2, and swine Eurasian-like avian H1N1, as well as reassortants between those viruses and CIV H3N2. These results highlight the potential ability of dogs to be a “mixing vessel” of diverse-origin influenza strains into novel reassortants.

Avian Influenza Virus in Cats

In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that a number of household cats in Thailand had been infected with a highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 strain, and at least one of the cats had been in contact with dead chickens (see who.int/csr/don/2004_02_20/en/). Further cases of H5N1 infections that year in Thailand were found in captive tigers and leopards that were fed infected chickens (Keawcharoen et al. 2004); some tigers became infected despite not being fed infected chickens, suggesting cat-to-cat transmission (Thanawongnuwech et al. 2005). Experimental inoculation of or feeding of meat from infected birds to domestic cats with H5N1 avian influenza viruses confirmed their susceptibility, as well as horizontal transmission between cats (Nakamura and Iwasa 1942; Kuiken et al. 2004; Rimmelzwaan et al. 2006).

A number of single cases of H5N1 HPAI cat infections in different parts of the world have also been reported, mostly associated with recent avian outbreaks or direct contact/feeding by the cats (Songserm et al. 2006; Yingst et al. 2006; Amonsin et al. 2007; Klopfleisch et al. 2007). Although most cases were referred for diagnosis because of disease or death, some subclinical infections also occurred, indicating that not all were severe (Leschnik et al. 2007). Infections of cats with HPAI was in some cases marked by significant infection pathology in the gastrointestinal tract, in addition to systemic spread to other tissues (Vahlenkamp et al. 2010; Reperant et al. 2012). Challenge in cats with an attenuated H5N6 low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) strain resulted in subclinical infections and viral shedding, and those cats were protected against HPAI H5N1 viruses (Vahlenkamp et al. 2008), suggesting that cross-strain protection may be sufficient to limit outbreak potential (Ayyalasomayajula et al. 2008). Field sero-surveys have confirmed that H5N1 HPAI exposures in cats remain fairly rare and most often coincide with wild or market bird outbreaks (Marschall et al. 2008; Desvaux et al. 2009; Sun et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2015).

The evidence of H5N1 HPAI infections in cats has led to several surveys and studies of their potential as hosts for other avian influenza strains. A fatal H5N6 infection in a cat in China followed 2014 outbreak cases in humans and preceded a poultry outbreak (Yu et al. 2015), whereas two novel H5N6 reassortants (with viral RNA segments derived from H9N2 and H7N9 viruses) were identified in cats in 2016 (Cao et al. 2017). Additional cases of H5N6 infections were found in cats in South Korea in proximity to a farm outbreak (Lee et al. 2018). Although there have been no other widely reported natural cases of avian-origin spillovers in cats, successful experimental infections include H5N2 (from an infected dog) (Hai-xia et al. 2014), H3N8 (from an equine lineage) (Su et al. 2014), H9N2 (Zhang et al. 2013), H7N7 (from an isolated human case) (van Riel et al. 2010), and LPAI H1N9 and H6N4 viruses endemic in shorebirds (Driskell et al. 2013).

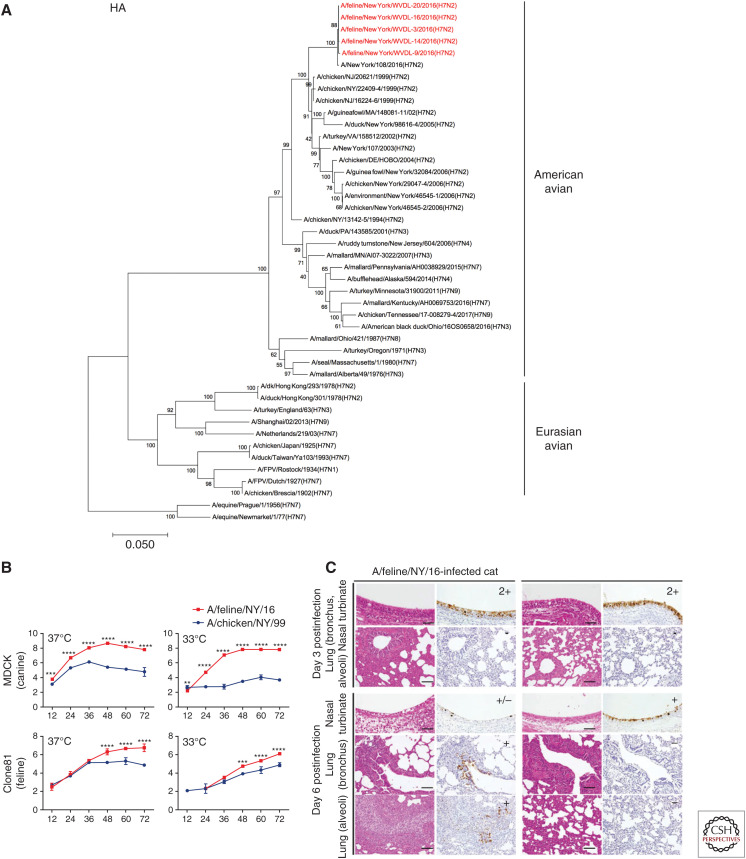

Outbreak of H7N2 Influenza Avian Influenza Virus in Cats in the United States

This outbreak occurred in late 2016 among cats housed in an animal shelter in New York state (Lee et al. 2017; Newbury et al. 2017). The cats were subsequently moved into a separate facility to facilitate control efforts, but because of the large number of cats in the shelter it took a number of weeks to bring the outbreak under control (Blachere et al. 2018). A human infection was observed in one of the veterinarians involved in the control program at the shelter, in whom virus was sampled from the respiratory tract, but no clinical disease was observed (Belser et al. 2017; Marinova-Petkova et al. 2017). Sequence and phylogenetic analysis showed that the virus closely matched circulating avian H7N2 in the New York area over the preceding decade (Fig. 4A). Comparative to an avian H7N2 lineage, the feline H7N2 isolate (A/feline/NY/2016) showed improved replication in mammalian cell lines (Fig. 4B) and pervasive infection of the feline respiratory tract (Fig. 4C) consistent with mammalian adaptation. Disease was rather mild, yet experimental and natural transmission was observed, suggesting further monitoring of shelter animals would be a good precaution for both human health risk and good veterinary health of companion animals (Hatta et al. 2018).

Figure 4.

H7N2 influenza in cats from 2016 New York outbreak. (A) Phylogenetic tree of influenza A viral hemagglutinin (HA) showing that feline H7N2 is closely related to avian lineages circulating in the United States. (B) Tissue culture replication of outbreak H7N2 (against comparative avian lineage) shows greater titers in mammalian cells. Virus titer (Log10PFU/mL) at hours postinfection. (C) Immunohistochemistry of nucleoprotein (NP) in sections of intranasally infected cats. Viral antigen suggests greater pervasive feline respiratory infection with outbreak H7N2 isolate. (A, Reproduced from Hatta et al. 2018, courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

INFLUENZA INFECTIONS OF OTHER MEMBERS OF THE ORDER CARNIVORA

Infections have occasionally been observed with influenza in multiple diverse suborders of carnivores besides cats and dogs. In particular, some members of the Mustalidae family are quite susceptible and have been closely studied. Ferrets have long been known to be highly susceptible to infection by human and many other influenza viruses and are used as a model for studying infection and transmission by those viruses (Bouvier and Lowen 2010; Belser et al. 2018). Mink are closely related to ferrets, and infections and outbreaks by many strains of avian, human, and swine influenza viruses on fur farms have been reported, including H10N4 (Berg et al. 1990), swine H3N2 (Gagnon et al. 2009), H1N1pdm (Åkerstedt et al. 2012), H1N2 (Yoon et al. 2012), H9N2 (Zhang et al. 2015a; Yong-Feng et al. 2017), and H5N1 (Jiang et al. 2017). However, it is likely that, in the wild, ferrets and mink (and most other wild carnivores) are too dispersed and do not come in contact sufficiently often enough to be able to allow more than a few individuals to be infected with a virus after any spillover event.

Seals and related Pinnipeds are infected by influenza viruses, likely because of exposure to avian influenza viruses in their environment in addition to close-contact herding ecology during beaching. Notable avian influenza spillovers have included H7N7 in 1980 in Cape Cod (United States) (Geraci et al. 1982), H3N8 in 2011 also in the Northeast United States (Anthony et al. 2012), and H10N7 in 2014 in Denmark and Sweden (Bodewes et al. 2015). These major cases of avian spillover involved harbor seals developing pneumonia with significant die-off owing to infection. It has also been reported that some seal populations sustain recurring influenza B virus infections originating from humans (Bodewes et al. 2013). Marine carnivores represent a unique interface of avian and mammalian influenza hosts at coastal waterways.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

It is now clear that dogs and cats are naturally but variably susceptible to many influenza virus strains from other hosts, including birds and mammals, but that biological and ecological barriers commonly reduce or prevent transmission. However, in some cases, sufficiently dense and well-connected populations exist to allow outbreaks or epidemics to occur, and those may be difficult to control in the absence of a concerted strategy. Although some reassortants between different strains of influenza have been reported in both dogs and cats, those appear to have not created extended outbreaks or epidemics to date. However, the close connections between dogs and cats with humans means that exposure of many humans of all ages and of varying health status is likely to occur, so that continued surveillance and control of feline and canine viruses seems necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Center of Research in Influenza Pathogenesis (CRIP), a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)-funded Center of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) under contract HHSN272201400008C to C.R.P., and by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 GM080533 to C.R.P. I.E.H.V. was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) award DGE-1650441.

This article has been made freely available online courtesy of TAUNS Laboratories.

Footnotes

Editors: Gabriele Neumann and Yoshihiro Kawaoka

Additional Perspectives on Influenza: The Cutting Edge available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Åkerstedt J, Valheim M, Germundsson A, Moldal T, Lie KI, Falk M, Hungnes O. 2012. Pneumonia caused by influenza A H1N1 2009 virus in farmed American mink (Neovison vison). Vet Rec 170: 362 10.1136/vr.100512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Daniels JB, Zhang Y, Rodriguez-Palacios A, Hayes-Ozello K, Mathes L, Lee CW. 2011. Pandemic and seasonal human influenza virus infections in domestic cats: prevalence, association with respiratory disease, and seasonality patterns. J Clin Microbiol 49: 4101–4105. 10.1128/JCM.05415-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amonsin A, Songserm T, Chutinimitkul S, Jam-On R, Sae-Heng N, Pariyothorn N, Payungporn S, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. 2007. Genetic analysis of influenza A virus (H5N1) derived from domestic cat and dog in Thailand. Arch Virol 152: 1925–1933. 10.1007/s00705-007-1010-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony SJ, St Leger JA, Pugliares K, Ip HS, Chan JM, Carpenter ZW, Navarrete-Macias I, Sanchez-Leon M, Saliki JT, Pedersen J, et al. 2012. Emergence of fatal avian influenza in New England harbor seals. mBio 3: e00166–00112. 10.1128/mBio.00166-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyalasomayajula S, DeLaurentis DA, Moore GE, Glickman LT. 2008. A network model of H5N1 avian influenza transmission dynamics in domestic cats. Zoonoses Public Health 55: 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Xu L, Zhan L, Deng W, Zhu H, Gao H, Sun H, Ma C, Lv Q, Li F, et al. 2010. Challenge and polymorphism analysis of the novel A (H1N1) influenza virus to normal animals. Virus Res 151: 60–65. 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Pulit-Penaloza JA, Sun X, Brock N, Pappas C, Creager HM, Zeng H, Tumpey TM, Maines TR. 2017. A novel A(H7N2) influenza virus isolated from a veterinarian caring for cats in a New York City animal shelter causes mild disease and transmits poorly in the ferret model. J Virol 91: e00672-17 10.1128/JVI.00672-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Barclay W, Barr I, Fouchier RAM, Matsuyama R, Nishiura H, Peiris M, Russell CJ, Subbarao K, Zhu H, et al. 2018. Ferrets as models for influenza virus transmission studies and pandemic risk assessments. Emerging Infect Dis 24: 965–971. 10.3201/eid2406.172114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Englund L, Abusugra IA, Klingeborn B, Linné T. 1990. Close relationship between mink influenza (H10N4) and concomitantly circulating avian influenza viruses. Arch Virol 113: 61–71. 10.1007/BF01318353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blachere FM, Lindsley WG, Weber AM, Beezhold DH, Thewlis RE, Mead KR, Noti JD. 2018. Detection of an avian lineage influenza A(H7N2) virus in air and surface samples at a New York City feline quarantine facility. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 12: 613–622. 10.1111/irv.12572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodewes R, Morick D, de Mutsert G, Osinga N, Bestebroer T, van der Vliet S, Smits SL, Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RAM, et al. 2013. Recurring influenza B virus infections in seals. Emerging Infect Dis 19: 511–512. 10.3201/eid1903.120965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodewes R, Bestebroer TM, van der Vries E, Verhagen JH, Herfst S, Koopmans MP, Fouchier RAM, Pfankuche VM, Wohlsein P, Siebert U, et al. 2015. Avian influenza A(H10N7) virus–associated mass deaths among harbor seals. Emerging Infect Dis 21: 720–722. 10.3201/eid2104.141675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier NM, Lowen AC. 2010. Animal models for influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission. Viruses 2: 1530–1563. 10.3390/v20801530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunpapong N, Nonthabenjawan N, Chaiwong S, Tangwangvivat R, Boonyapisitsopa S, Jairak W, Tuanudom R, Prakairungnamthip D, Suradhat S, Thanawongnuwech R, et al. 2014. Genetic characterization of canine influenza A virus (H3N2) in Thailand. Virus Genes 48: 56–63. 10.1007/s11262-013-0978-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnolo ER, Rankin JT, Daverio SA, Hunt EA, Lute JR, Tewari D, Acland HM, Ostrowski SR, Moll ME, Urdaneta VV, et al. 2011. Fatal pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus infection in a Pennsylvania domestic cat. Zoonoses Public Health 58: 500–507. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yang F, Wu H, Xu L. 2017. Genetic characterization of novel reassortant H5N6-subtype influenza viruses isolated from cats in eastern China. Arch Virol 162: 3501–3505. 10.1007/s00705-017-3490-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castleman WL, Powe JR, Crawford PC, Gibbs EPJ, Dubovi EJ, Donis RO, Hanshaw D. 2010. Canine H3N8 influenza virus infection in dogs and mice. Vet Pathol 47: 507–517. 10.1177/0300985810363718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CP, New AE, Taylor JF, Chiang HS. 1976. Influenza virus isolations from dogs during a human epidemic in Taiwan. Int J Zoonoses 3: 61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Trovão NS, Wang G, Zhao W, He P, Zhou H, Mo Y, Wei Z, Ouyang K, Huang W, et al. 2018. Emergence and evolution of novel reassortant influenza A viruses in canines in Southern China. MBio 9: e00909-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford PC, Dubovi EJ, Castleman WL, Stephenson I, Gibbs EPJ, Chen L, Smith C, Hill RC, Ferro P, Pompey J, et al. 2005. Transmission of equine influenza virus to dogs. Science 310: 482–485. 10.1126/science.1117950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispe E, Finlaison DS, Hurt AC, Kirkland PD. 2011. Infection of dogs with equine influenza virus: evidence for transmission from horses during the Australian outbreak. Aust Vet J 89: 27–28. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2011.00734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly JM, Blunden AS, Macrae S, Miller J, Bowman SJ, Kolodziejek J, Nowotny N, Smith KC. 2008. Transmission of equine influenza virus to English foxhounds. Emerging Infect Dis 14: 461–464. 10.3201/eid1403.070643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel BD, Huang K, Geoghegan JL, Arinaminpathy N, Dubovi EJ, Grenfell BT, Ellner SP, Holmes EC, Parrish CR. 2014. Contact heterogeneity, rather than transmission efficiency, limits the emergence and spread of canine influenza virus. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004455 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani AM, Kalthoff D, Beer M, Müller E, Osterrieder N. 2012. Serological survey in dogs and cats for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in Germany. Zoonoses Public Health 59: 549–552. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux S, Marx N, Ong S, Gaidet N, Hunt M, Manuguerra JC, Sorn S, Peiris M, Van der Werf S, Reynes JM. 2009. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) outbreak in captive wild birds and cats, Cambodia. Emerging Infect Dis 15: 475–478. 10.3201/eid1503.081410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driskell EA, Jones CA, Berghaus RD, Stallknecht DE, Howerth EW, Tompkins SM. 2013. Domestic cats are susceptible to infection with low pathogenic avian influenza viruses from shorebirds. Vet Pathol 50: 39–45. 10.1177/0300985812452578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundon WG, De Benedictis P, Viale E, Capua I. 2010. Serologic evidence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection in dogs, Italy. Emerging Infect Dis 16: 2019–2021. 10.3201/eid1612.100514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng KH, Gonzalez G, Deng L, Yu H, Tse VL, Huang L, Huang K, Wasik BR, Zhou B, Wentworth DE, et al. 2015. Equine and canine influenza H3N8 viruses show minimal biological differences despite phylogenetic divergence. J Virol 89: 6860–6873. 10.1128/JVI.00521-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini L, Taddei R, Moreno A, Gelmetti D, Barbieri I, De Marco MA, Tosi G, Cordioli P, Massi P. 2011. Influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus outbreak in a cat colony in Italy. Zoonoses Public Health 58: 573–581. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01406.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyson RE, Westwood JC, Brunner AH. 1975. An immunoprecipitin study of the incidence of influenza A antibodies in animal sera in the Ottawa area. Can J Microbiol 21: 1089–1101. 10.1139/m75-159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon CA, Spearman G, Hamel A, Godson DL, Fortin A, Fontaine G, Tremblay D. 2009. Characterization of a Canadian mink H3N2 influenza A virus isolate genetically related to triple reassortant swine influenza virus. J Clin Microbiol 47: 796–799. 10.1128/JCM.01228-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraci JR, St Aubin DJ, Barker IK, Webster RG, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Ruhnke HL, Prescott JH, Early G, Baker AS, et al. 1982. Mass mortality of harbor seals: pneumonia associated with influenza A virus. Science 215: 1129–1131. 10.1126/science.7063847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez G, Marshall JF, Morrell J, Robb D, McCauley JW, Perez DR, Parrish CR, Murcia PR. 2014. Infection and pathogenesis of canine, equine, and human influenza viruses in canine tracheas. J Virol 88: 9208–9219. 10.1128/JVI.00887-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2003. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol 52: 696–704. 10.1080/10635150390235520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai-xia F, Yuan-yuan L, Qian-qian S, Zong-shuai L, Feng-xia Z, Yan-li Z, Shi-jin J, Zhi-jing X. 2014. Interspecies transmission of canine influenza virus H5N2 to cats and chickens by close contact with experimentally infected dogs. Vet Microbiol 170: 414–417. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Zhong G, Gao Y, Nakajima N, Fan S, Chiba S, Deering KM, Ito M, Imai M, Kiso M, et al. 2018. Characterization of a feline influenza A(H7N2) virus. Emerging Infect Dis 24: 75–86. 10.3201/eid2401.171240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward JJ, Dubovi EJ, Scarlett JM, Janeczko S, Holmes EC, Parrish CR. 2010. Microevolution of canine influenza virus in shelters and its molecular epidemiology in the United States. J Virol 84: 12636–12645. 10.1128/JVI.01350-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser RE, Heuschele WP. 1980. Evidence of prior infection with influenza A/Texas/77 (H3N2) virus in dogs with clinical parainfluenza. Can J Comp Med 44: 396–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M, Ali A, Daniels JB, Lee CW. 2016. Post-pandemic seroprevalence of human influenza viruses in domestic cats. J Vet Sci 17: 515–521. 10.4142/jvs.2016.17.4.515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung HY, Lim SI, Shin BH, Lim JA, Song JY, Song DS, Kang BK, Moon HJ, An DJ. 2013. A novel canine influenza H3N2 virus isolated from cats in an animal shelter. Vet Microbiol 165: 281–286. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Wang S, Zhang C, Li J, Hou G, Peng C, Chen J, Shan H. 2017. Characterization of H5N1 highly pathogenic mink influenza viruses in eastern China. Vet Microbiol 201: 225–230. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keawcharoen J, Oraveerakul K, Kuiken T, Fouchier RAM, Amonsin A, Payungporn S, Noppornpanth S, Wattanodorn S, Theambooniers A, Tantilertcharoen R, et al. 2004. Avian influenza H5N1 in tigers and leopards. Emerging Infect Dis 10: 2189–2191. 10.3201/eid1012.040759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne ED, Kehoe JM. 1975. Demonstration of antibodies to both hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigens of H3N2 influenza A virus in domestic dogs. Intervirology 6: 315–318. 10.1159/000149485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland PD, Finlaison DS, Crispe E, Hurt AC. 2010. Influenza virus transmission from horses to dogs, Australia. Emerging Infect Dis 16: 699–702. 10.3201/eid1604.091489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klopfleisch R, Wolf PU, Uhl W, Gerst S, Harder T, Starick E, Vahlenkamp TW, Mettenleiter TC, Teifke JP. 2007. Distribution of lesions and antigen of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A/Swan/Germany/R65/06 (H5N1) in domestic cats after presumptive infection by wild birds. Vet Pathol 44: 261–268. 10.1354/vp.44-3-261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight CG, Davies JL, Joseph T, Ondrich S, Rosa BV. 2016. Pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection in a Canadian cat. Can Vet J 57: 497–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger WS, Heil GL, Yoon KJ, Gray GC. 2014. No evidence for zoonotic transmission of H3N8 canine influenza virus among US adults occupationally exposed to dogs. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 8: 99–106. 10.1111/irv.12208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken T, Rimmelzwaan G, van Riel D, van Amerongen G, Baars M, Fouchier R, Osterhaus A. 2004. Avian H5N1 influenza in cats. Science 306: 241 10.1126/science.1102287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Song D, Kang B, Kang D, Yoo J, Jung K, Na G, Lee K, Park B, Oh J. 2009. A serological survey of avian origin canine H3N2 influenza virus in dogs in Korea. Vet Microbiol 137: 359–362. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YN, Lee HJ, Lee DH, Kim JH, Park HM, Nahm SS, Lee JB, Park SY, Choi IS, Song CS. 2011. Severe canine influenza in dogs correlates with hyperchemokinemia and high viral load. Virology 417: 57–63. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CT, Slavinski S, Schiff C, Merlino M, Daskalakis D, Liu D, Rakeman JL, Misener M, Thompson C, Leung YL, et al. 2017. Outbreak of influenza A(H7N2) among cats in an animal shelter with cat-to-human transmission—New York City, 2016. Clin Infect Dis 65: 1927–1929. 10.1093/cid/cix668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Lee EK, Lee H, Heo GB, Lee YN, Jung JY, Bae YC, So B, Lee YJ, Choi EJ. 2018. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N6) in domestic cats, South Korea. Emerging Infect Dis 24: 2343–2347. 10.3201/eid2412.180290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leschnik M, Weikel J, Möstl K, Revilla-Fernández S, Wodak E, Bagó Z, Vanek E, Benetka V, Hess M, Thalhammer JG. 2007. Subclinical infection with avian influenza A (H5N1) virus in cats. Emerging Infect Dis 13: 243–247. 10.3201/eid1302.060608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löhr CV, DeBess EE, Baker RJ, Hiett SL, Hoffman KA, Murdoch VJ, Fischer KA, Mulrooney DM, Selman RL, Hammill-Black WM. 2010. Pathology and viral antigen distribution of lethal pneumonia in domestic cats due to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus. Vet Pathol 47: 378–386. 10.1177/0300985810368393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan HN, Agarwal SC. 1976. Sero-epidemiology of human and canine influenza in Pondicherry, South India, during 1971–1974. Indian J Med Res 64: 835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinova-Petkova A, Laplante J, Jang Y, Lynch B, Zanders N, Rodriguez M, Jones J, Thor S, Hodges E, De La Cruz JA, et al. 2017. Avian influenza A(H7N2) virus in human exposed to sick cats, New York, USA, 2016. Emerging Infect Dis 23 10.3201/eid2312.170798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall J, Schulz B, Harder Priv-Doz TC, Vahlenkamp Priv-Doz TW, Huebner J, Huisinga E, Hartmann K. 2008. Prevalence of influenza A H5N1 virus in cats from areas with occurrence of highly pathogenic avian influenza in birds. J Feline Med Surg 10: 355–358. 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. 2015. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol 1: vev003 10.1093/ve/vev003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullers JA, Van De Velde L-A, Schultz RD, Mitchell CG, Halford CR, Boyd KL, Schultz-Cherry S. 2011. Seroprevalence of seasonal and pandemic influenza A viruses in domestic cats. Arch Virol 156: 117–120. 10.1007/s00705-010-0809-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na W, Lyoo KS, Song E, Hong M, Yeom M, Moon H, Kang BK, Kim DJ, Kim JK, Song D. 2015. Viral dominance of reassortants between canine influenza H3N2 and pandemic (2009) H1N1 viruses from a naturally co-infected dog. Virol J 12: 134 10.1186/s12985-015-0343-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura J, Iwasa T. 1942. On the fowl-pest infection in cat. Jpn J Vet Sci 4: 511–523. 10.1292/jvms1939.4.511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury S, Godhardt-Cooper J, Poulsen KP, Cigel F, Balanoff L, Toohey-Kurth K. 2016. Prolonged intermittent virus shedding during an outbreak of canine influenza A H3N2 virus infection in dogs in three Chicago area shelters: 16 cases (March to May 2015). J Am Vet Med Assoc 248: 1022–1026. 10.2460/javma.248.9.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury SP, Cigel F, Killian ML, Leutenegger CM, Seguin MA, Crossley B, Brennen R, Suarez DL, Torchetti M, Toohey-Kurth K. 2017. First detection of avian lineage H7N2 in Felis catus. Genome Announc 5: e00457–17. 10.1128/genomeA.00457-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton R, Cooke A, Elton D, Bryant N, Rash A, Bowman S, Blunden T, Miller J, Hammond T-A, Camm I, et al. 2007. Canine influenza virus: cross-species transmission from horses. Vet Rec 161: 142–143. 10.1136/vr.161.4.142-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikitin A, Cohen D, Todd JD, Lief FS. 1972. Epidemiological studies of A-Hong Kong-68 virus infection in dogs. Bull World Health Organ 47: 471–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onta T, Kida H, Kawano J, Matsuoka Y, Yanagawa R. 1978. Distribution of antibodies against various influenza A viruses in animals. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 40: 451–454. 10.1292/jvms1939.40.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniker CK, Nair CM. 1970. Infection with A2 Hong Kong influenza virus in domestic cats. Bull World Health Organ 43: 859–862. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniker CK, Nair CM. 1972. Experimental infection of animals with influenzavirus types A and B. Bull World Health Organ 47: 461–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payungporn S, Crawford PC, Kouo TS, Chen L, Pompey J, Castleman WL, Dubovi EJ, Katz JM, Donis RO. 2008. Influenza A virus (H3N8) in dogs with respiratory disease, Florida. Emerging Infect Dis 14: 902–908. 10.3201/eid1406.071270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro HL, Bennett S, Garretson K, Quintana AM, Lunn KF, Landolt GA. 2013. Comparison of the infectivity and transmission of contemporary canine and equine H3N8 influenza viruses in dogs. Vet Med Int 2013: 874521 10.1155/2013/874521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro HL, Bennett S, Huyvaert KP, Spindel ME, Landolt GA. 2014. Epidemiology and ecology of H3N8 canine influenza viruses in US shelter dogs. J Vet Intern Med 28: 311–318. 10.1111/jvim.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccirillo A, Pasotto D, Martin AM, Cordioli P. 2010. Serological survey for influenza type A viruses in domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) and cats (Felis catus) in north-eastern Italy. Zoonoses Public Health 57: 239–243. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott AM, Haak CE, Breshears MA, Linklater AKJ. 2014. Acute bronchointerstitial pneumonia in two indoor cats exposed to the H1N1 influenza virus. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 24: 715–723. 10.1111/vec.12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingret JL, Rivière D, Lafon S, Etiévant M, Boucraut-Baralon C. 2010. Epidemiological survey of H1N1 influenza virus in cats in France. Vet Rec 166: 307 10.1136/vr.c1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulit-Penaloza JA, Simpson N, Yang H, Creager HM, Jones J, Carney P, Belser JA, Yang G, Chang J, Zeng H, et al. 2017. Assessment of molecular, antigenic, and pathological features of canine influenza A(H3N2) viruses that emerged in the United States. J Infect Dis 216: S499–S507. 10.1093/infdis/jiw620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reperant LA, van de Bildt MWG, van Amerongen G, Leijten LME, Watson S, Palser A, Kellam P, Eissens AC, Frijlink HW, Osterhaus ADME, et al. 2012. Marked endotheliotropism of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 following intestinal inoculation in cats. J Virol 86: 1158–1165. 10.1128/JVI.06375-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmelzwaan GF, van Riel D, Baars M, Bestebroer TM, van Amerongen G, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME, Kuiken T. 2006. Influenza A virus (H5N1) infection in cats causes systemic disease with potential novel routes of virus spread within and between hosts. Am J Pathol 168: 176–183. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romváry J, Rózsa J, Farkas E. 1975. Infection of dogs and cats with the Hong Kong influenza A (H3N2) virus during an epidemic period in Hungary. Acta Vet Acad Sci Hung 25: 255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said AWA, Usui T, Shinya K, Ono E, Ito T, Hikasa Y, Matsuu A, Takeuchi T, Sugiyama A, Nishii N, et al. 2011. A sero-survey of subtype H3 influenza A virus infection in dogs and cats in Japan. J Vet Med Sci 73: 541–544. 10.1292/jvms.10-0428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler BM, Yoon KJ, Andreasen CB, Block SM, Marsden S, Blitvich BJ. 2010. Antibodies to influenza A virus (H1 and H3) in companion animals in Iowa, USA. Vet Rec 167: 705–707. 10.1136/vr.c5120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Moon H, Jung K, Yeom M, Kim H, Han S, An D, Oh J, Kim J, Park B, et al. 2011a. Association between nasal shedding and fever that influenza A (H3N2) induces in dogs. Virol J 8: 1 10.1186/1743-422X-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song DS, An DJ, Moon HJ, Yeom MJ, Jeong HY, Jeong WS, Park SJ, Kim HK, Han SY, Oh JS, et al. 2011b. Interspecies transmission of the canine influenza H3N2 virus to domestic cats in South Korea, 2010. J Gen Virol 92: 2350–2355. 10.1099/vir.0.033522-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Moon HJ, An DJ, Jeoung HY, Kim H, Yeom MJ, Hong M, Nam JH, Park SJ, Park BK, et al. 2012. A novel reassortant canine H3N1 influenza virus between pandemic H1N1 and canine H3N2 influenza viruses in Korea. J Gen Virol 93: 551–554. 10.1099/vir.0.037739-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songserm T, Amonsin A, Jam-on R, Sae-Heng N, Meemak N, Pariyothorn N, Payungporn S, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. 2006. Avian influenza H5N1 in naturally infected domestic cat. Emerging Infect Dis 12: 681–683. 10.3201/eid1204.051396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sponseller BA, Strait E, Jergens A, Trujillo J, Harmon K, Koster L, Jenkins-Moore M, Killian M, Swenson S, Bender H, et al. 2010. Influenza A pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection in domestic cat. Emerging Infect Dis 16: 534–537. 10.3201/eid1603.091737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Chen Y, Zhao FR, Chen JD, Xie JX, Chen ZM, Huang Z, Hu YM, Zhang MZ, Tan LK, et al. 2013a. Avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza virus circulating in farmed dogs in Guangdong, China. Infect Genet Evol 19: 251–256. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Yuan L, Li H, Chen J, Xie J, Huang Z, Jia K, Li S. 2013b. Serologic evidence of pandemic influenza virus H1N1 2009 infection in cats in China. Clin Vaccine Immunol 20: 115–117. 10.1128/CVI.00618-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Wang L, Fu X, He S, Hong M, Zhou P, Lai A, Gray G, Li S. 2014. Equine influenza A(H3N8) virus infection in cats. Emerging Infect Dis 20: 2096–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Kinoshita R, Gray J, Ji Y, Yu D, Peiris JSM, Yen HL. 2019. Seroprevalence of dogs in Hong Kong to human and canine influenza viruses. Vet Rec Open 6: e000327 10.1136/vetreco-2018-000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhou P, He S, Luo Y, Jia K, Fu C, Sun Y, He H, Tu L, Ning Z, et al. 2015. Sparse serological evidence of H5N1 avian influenza virus infections in domestic cats, northeastern China. Microb Pathog 82: 27–30. 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangwangvivat R, Chanvatik S, Charoenkul K, Chaiyawong S, Janethanakit T, Tuanudom R, Prakairungnamthip D, Boonyapisitsopa S, Bunpapong N, Amonsin A. 2019. Evidence of pandemic H1N1 influenza exposure in dogs and cats, Thailand: a serological survey. Zoonoses Public Health 66: 349–353. 10.1111/zph.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanawongnuwech R, Amonsin A, Tantilertcharoen R, Damrongwatanapokin S, Theamboonlers A, Payungporn S, Nanthapornphiphat K, Ratanamungklanon S, Tunak E, Songserm T, et al. 2005. Probable tiger-to-tiger transmission of avian influenza H5N1. Emerging Infect Dis 11: 699–701. 10.3201/eid1105.050007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahlenkamp TW, Harder TC, Giese M, Lin F, Teifke JP, Klopfleisch R, Hoffmann R, Tarpey I, Beer M, Mettenleiter TC. 2008. Protection of cats against lethal influenza H5N1 challenge infection. J Gen Virol 89: 968–974. 10.1099/vir.0.83552-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahlenkamp TW, Teifke JP, Harder TC, Beer M, Mettenleiter TC. 2010. Systemic influenza virus H5N1 infection in cats after gastrointestinal exposure. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 4: 379–386. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00173.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brand JMA, Stittelaar KJ, van Amerongen G, van de Bildt MWG, Leijten LME, Kuiken T, Osterhaus ADME. 2010. Experimental pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus infection of cats. Emerging Infect Dis 16: 1745–1747. 10.3201/eid1611.100845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riel D, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, Osterhaus ADME, Kuiken T. 2010. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H7N7 isolated from a fatal human case causes respiratory disease in cats but does not spread systemically. Am J Pathol 177: 2185–2190. 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees IEH, Glaser AL, Toohey-Kurth K, Newbury S, Dalziel BD, Dubovi EJ, Poulsen K, Leutenegger C, Willgert KJE, Brisbane-Cohen L, et al. 2017. Spread of canine influenza A(H3N2) virus, United States. Emerging Infect Dis 23: 1950–1957. 10.3201/eid2312.170246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees IEH, Dalziel BD, Glaser A, Dubovi EJ, Murcia PR, Newbury S, Toohey-Kurth K, Su S, Kriti D, Van Bakel H, et al. 2018. Multiple incursions and recurrent epidemic fade-out of H3N2 canine influenza A virus in the United States. J Virol 92: e00323-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weese JS, Anderson MEC, Berhane Y, Doyle KF, Leutenegger C, Chan R, Chiunti M, Marchildon K, Dumouchelle N, DeGelder T, et al. 2019. Emergence and containment of canine influenza virus A(H3N2), Ontario, Canada, 2017–2018. Emerging Infect Dis 25: 1810–1816. 10.3201/eid2510.190196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T, Nemoto M, Tsujimura K, Kondo T, Matsumura T. 2009. Interspecies transmission of equine influenza virus (H3N8) to dogs by close contact with experimentally infected horses. Vet Microbiol 139: 351–355. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T, Tsujimura K, Kondo T, Matsumura T, Ishida H, Kiso M, Hidari KIPJ, Suzuki T. 2010. Infectivity and pathogenicity of canine H3N8 influenza A virus in horses. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 4: 345–351. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00157.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T, Nemoto M, Bannai H, Tsujimura K, Kondo T, Matsumura T, Muranaka M, Ueno T, Kinoshita Y, Niwa H, et al. 2012. No evidence of horizontal infection in horses kept in close contact with dogs experimentally infected with canine influenza A virus (H3N8). Acta Vet Scand 54: 25 10.1186/1751-0147-54-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Zhao FR, Zhou DH, Wei P, Chang HY. 2014. Serological report of pandemic and seasonal human influenza virus infection in dogs in southern China. Arch Virol 159: 2877–2882. 10.1007/s00705-014-2119-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yingst SL, Saad MD, Felt SA. 2006. Qinghai-like H5N1 from domestic cats, northern Iraq. Emerging Infect Dis 12: 1295–1297. 10.3201/eid1708.060264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong-Feng Z, Fei-Fei D, Jia-Yu Y, Feng-Xia Z, Chang-Qing J, Jian-Li W, Shou-Yu G, Kai C, Chuan-Yi L, Xue-Hua W, et al. 2017. Intraspecies and interspecies transmission of mink H9N2 influenza virus. Sci Rep 7: 7429 10.1038/s41598-017-07879-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K-J, Schwartz K, Sun D, Zhang J, Hildebrandt H. 2012. Naturally occurring influenza A virus subtype H1N2 infection in a Midwest United States mink (Mustela vison) ranch. J Vet Diagn Invest 24: 388–391. 10.1177/1040638711428349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Gao X, Wang T, Li Y, Li Y, Xu Y, Chu D, Sun H, Wu C, Li S, et al. 2015. Fatal H5N6 avian influenza virus infection in a domestic cat and wild birds in China. Sci Rep 5: 10704 10.1038/srep10704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Zhang Z, Yu Z, Li L, Cheng K, Wang T, Huang G, Yang S, Zhao Y, Feng N, et al. 2013. Domestic cats and dogs are susceptible to H9N2 avian influenza virus. Virus Res 175: 52–57. 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Xuan Y, Shan H, Yang H, Wang J, Wang K, Li G, Qiao J. 2015a. Avian influenza virus H9N2 infections in farmed minks. Virol J 12: 180 10.1186/s12985-015-0411-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Shen Y, Du L, Wang R, Jiang B, Sun H, Pu J, Lin D, Wang M, Liu J, et al. 2015b. Serological survey of canine H3N2, pandemic H1N1/09, and human seasonal H3N2 influenza viruses in cats in northern China, 2010-2014. Virol J 12: 50 10.1186/s12985-015-0285-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FR, Liu CG, Yin X, Zhou DH, Wei P, Chang HY. 2014. Serological report of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection among cats in northeastern China in 2012-02 and 2013-03. Virol J 11: 49 10.1186/1743-422X-11-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao FR, Zhou DH, Zhang YG, Shao JJ, Lin T, Li YF, Wei P, Chang HY. 2015. Detection prevalence of H5N1 avian influenza virus among stray cats in eastern China. J Med Virol 87: 1436–1440. 10.1002/jmv.24216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, He S, Sun L, He H, Ji F, Sun Y, Jia K, Ning Z, Wang H, Yuan L, et al. 2015. Serological evidence of avian influenza virus and canine influenza virus infections among stray cats in live poultry markets, China. Vet Microbiol 175: 369–373. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Hughes J, Murcia PR. 2015. Origins and evolutionary dynamics of H3N2 canine influenza virus. J Virol 89: 5406–5418. 10.1128/JVI.03395-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]