Abstract

Aim

First responder (FR) programmes dispatch professional FRs (police and/or firefighters) or citizen responders to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and use automated external defibrillators (AED) in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). We aimed to describe management of FR-programmes across Europe in response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

In June 2020, we conducted a cross-sectional survey sent to OHCA registry representatives in 18 European countries with active FR-programmes. The survey was administered by e-mail and included questions regarding management of both citizen responder and FR-programmes. A follow-up question was conducted in October 2020 assessing management during a potential “second wave” of COVID-19.

Results

All representatives responded (response rate = 100%). Fourteen regions dispatched citizen responders and 17 regions dispatched professional FRs (9 regions dispatched both). Responses were post-hoc divided into three categories: FR activation continued unchanged, FR activation continued with restrictions, or FR activation temporarily paused. For citizen responders, regions either temporarily paused activation (n = 7, 50.0%) or continued activation with restrictions (n = 7, 50.0%). The most common restriction was to omit rescue breaths and perform compression-only CPR. For professional FRs, nine regions continued activation with restrictions (52.9%) and five regions (29.4%) continued activation unchanged, but with personal protective equipment available for the professional FRs. In three regions (17.6%), activation of professional FRs temporarily paused.

Conclusion

Most regions changed management of FR-programmes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies are needed to investigate the consequences of pausing or restricting FR-programmes for bystander CPR and AED use, and how this may impact patient outcome.

Keywords: CPR, AED, OHCA, Citizen responder, Corona

Introduction

First responder (FR) programmes are part of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) response in many regions in Europe.1 They include activation of citizen responders and/or professional FRs (firefighters and/or police) to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and/or use automated external defibrillators (AED) before arrival of the Emergency Medical Services (EMS).2, 3, 4, 5 FR-programmes can decrease time to resuscitation6, 7, 8 and are therefore an important part of the system of care strategy “Chain of Survival” to increase survival following OHCA.9 Regulation of FR-programmes are often controlled by local EMS organisations and variations in management differ within countries and between countries in Europe.1

The outbreak of the novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.10 The outbreak has led to changes in recommendations for management of OHCA patients in the prehospital setting to prevent transmission of the virus to the care provider.11, 12 It is recommended that all FRs should wear personal protective equipment (PPE),12 but the high demand for PPE during the pandemic has led to a supply shortage in some regions,13, 14 and providing PPE to citizen responders in particular is not feasible since they are often lay persons and some programmes include thousands of citizen responders. Since management of FR-programmes differs between regions in Europe,1 it is likely to differ during the COVID-19 pandemic as well. Management needs to consider the balance of potential risk of exposing FRs to COVID-19 and increase the chance of improved outcome for the OHCA patient, strongly associated with bystander CPR and rapid defibrillation.15, 16

We aimed to investigate differences in strategies for FR-programmes management during the COVID-19 pandemic across European regions. This can be used as basis for strategic management of FR-programmes during unpredictable changes in the prehospital setting such as a pandemic.

Methods

We identified regions through a previous study from 2019 describing dispatched FR-programmes in Europe.1 We included 18 countries with active FR-programmes before the COVID-19 pandemic. Nine of them dispatched both citizen responders and professional FRs, 3 dispatched only citizen responders, and six dispatched only professional FRs. The included countries and respective regions are described in Supplemental Table 1.

A citizen responder is a person who volunteers to be dispatched to perform CPR and/or use an AED if located close to an OHCA. Citizen responder programmes can include lay persons or others such as off-duty healthcare professionals or taxi drivers. Citizen responders are activated by the emergency dispatch centre in case of a suspected OHCA. They are either alerted through smartphone applications or text-message systems. Professional FRs are defined as firefighters and/or police who are dispatched by the emergency dispatch centre. Professional FRs are often equipped with AEDs. This categorisation was defined when conducting the survey and accepted by the included regions. Details of each region’s FR programme have been previously described.1

We collected information from all countries by direct contact via e-mail in June 2020. All representatives for OHCA registries were asked a personalised open question with the possibility to respond with detailed information about how they managed their FR-programmes in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. A second attempt was made to get non-responding representatives to take part after approximately 7 days. Since the COVID-19 pandemic evolved in many countries after June 2020, regions could have experienced a second increase in number of persons with COVID-19 (a “second wave”). Therefore, a follow-up question was sent out in the end of October 2020 to assess how the included regions managed their FR-programmes during a potential second wave.

Results

The response rate was 100% (18 out of 18 countries). Management of FR-programmes differed between regions. Responses for both citizen responders and professional FRs were categorised post-hoc into three groups: 1) activation of FR-programmes remained unchanged, 2) FR activation continued with restrictions, or 3) FR activation temporarily paused.

Citizen responder programmes

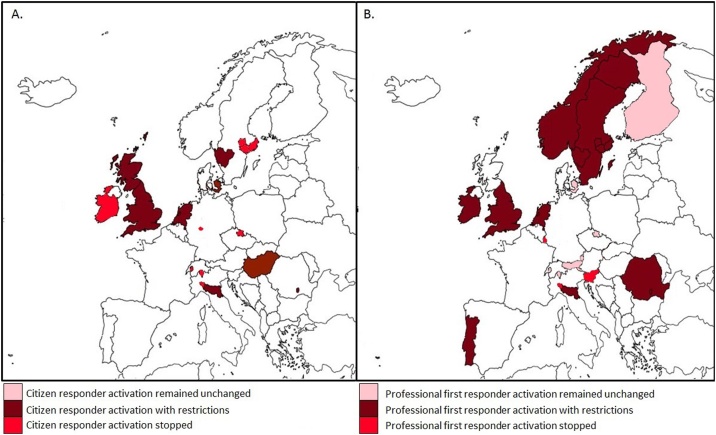

Regions either paused activation of citizen responders temporarily (7 out of 14) or had their citizen responder programme active but with restrictions (7 out of 14) (Fig. 1A). The most common restriction was informing citizen responders not to perform rescue breaths but to instead perform compression-only CPR (Table 1). Only two regions changed management during the second wave of COVID-19. Switzerland activated their citizen responder programme, but the region had not experienced a second wave yet when the survey was conducted. Czech Republic also activated their citizen responder programme, but all citizen responders where instructed to follow ERC guidelines for resuscitation during COVID-19 (Table 1).12

Fig. 1.

Management of First Responder Programmes Across European Regions during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Map over regions in Europe. Only regions included in the present study are coloured.

Table 1.

Description of management of citizen responder programmes across European regions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Country Region |

Activation unchanged | Activation with restrictions | Activation temporarily paused | Are changes made in management during the second wave of COVID-19? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Czech Republic Hradec Kralove Region |

Activation temporarily paused. | Yes, activation was not paused, but dispatched citizens were instructed to follow the new ERC COVID-19 guidelines. | ||

| Denmark The Capital Region |

Compression-only CPR. Do not accept alarm if your daily work is essential for the community or you are in a risk group for COVID-19. Use glows and disinfect/wash hands before and after resuscitation. |

No | ||

| England South Central Ambulance Services NHS Foundation Trust |

Mandatory to use Level 3 PPE to perform airway procedure. Responders wear Level 2 and should therefore put cloth or similar over patient’s mouth and nose when performing CPR and use AED. | No | ||

| Germany Marburg-Biedenkopf |

Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| Hungary | Compression-only CPR. Do not check for breathing, only check for signs of life from the side of the patient. |

No | ||

| Ireland | Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| Italy Emilia Romagna |

Compression-only CPR, except for children and hypoxic cardiac arrests. Surgical mask, cloth or similar over patient’s mouth. |

No | ||

| Italy Lombardia |

Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| The Netherlands | Compression-only CPR for unknown COVID-19 status. If COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, CPR is not recommended, only attach and use an AED. Citizen responders >50 years of age are not dispatched. |

No | ||

| Romania (Bucharest) | Compression-only CPR for unknown COVID-19 status. If COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, compression-only CPR, except for children. Mask is recommended. |

No | ||

| Scotland | Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| Sweden Stockholm, Västra Götaland, Sörmland, Östergötland, Västmanland |

Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| Sweden Blekinge, Kronoberg |

Compression-only CPR if COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, except for children and hypoxic cardiac arrests. Standard CPR guidelines if COVID-19 is not suspected. |

No | ||

| Switzerland Ticino, Berne, Fribourg |

Activation temporarily paused. | Yes, currently all systems are active. * |

AED, automated external defibrillator; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PPE, personal protective equipment. *Countries or regions where an increase in COVID-19 cases (a second wave) has not yet been detected.

Professional FRs

Half of the regions (9 out of 17) continued activation of professional FRs but with restrictions (Fig. 1B). Like citizen responder programmes, the most common restriction was to omit rescue breaths and perform compression-only CPR (Table 2). Five regions (29.4%) continued activation unchanged, but the professional FRs were equipped with PPE to reduce risk of virus contamination. Finally, in three regions (17.6%), activation of professional FRs temporarily paused. During the second wave of COVID-19, most regions continued with the same management. Slovenia restarted their professional FR programme but was not affected by a second wave when the survey was conducted.

Table 2.

Description of management of professional FRs across european regions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Country Region |

Activation unchanged | Activation with restrictions | Activation temporarily paused | Are changes made in management during the second wave of COVID-19? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria Vorarlberg, the Tyrol, and Salzburg |

Professional FRs are equipped with PPE. | No | ||

| Czech Republic Hradec Kralove Region |

Professional FRs are equipped with PPE. | No | ||

| Denmark The Capital Region |

Professional FRs are equipped with PPE. | No | ||

| England South Central Ambulance Services NHS Foundation Trust |

Mandatory to use Level 3 PPE to perform airway procedure. Responders wear Level 2 and should therefore put cloth or similar over patient’s mouth and nose when performing CPR and use AED. | No | ||

| Finland | Professional FRs are equipped with PPE. | No | ||

| Ireland | Firefighters are equipped with PPE. Activation of police temporarily paused. |

No | ||

| Italy Emilia Romagna |

Compression-only CPR except for children and hypoxic cardiac arrests. Cloth or similar over patient’s mouth and nose. |

No | ||

| Italy Lombardia |

Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| Luxembourg | Activation temporarily paused. | No | ||

| The Netherlands | Compression-only CPR for unknown COVID-19 status. If COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, CPR is not recommended, only attach and use an AED. |

No | ||

| Norway | Great regional variations, but general national guidelines were: In low risk of COVID-19 and children, standard CPR guidelines but compression-only CPR accepted. In high risk of COVID-19: only professional FRs who are trained in PPE are activated. |

No | ||

| Portugal | Compression-only CPR if COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected. Standard CPR guidelines if COVID-19 is not suspected. |

No | ||

| Romania | Mask recommended. | |||

| Slovenia | Activation temporarily paused. | Yes, activation was restarted, but with ongoing discussions about management during a second wave * | ||

| Sweden Stockholm, Västra Götaland, Sörmland, Östergötland, Västmanland |

Compression-only CPR if COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, except for children and hypoxic cardiac arrests. Standard CPR guidelines if COVID-19 is not suspected. |

No | ||

| Sweden Blekinge, Kronoberg |

Compression-only CPR if COVID-19 is confirmed or suspected, except for children and hypoxic cardiac arrests. Standard CPR guidelines if COVID-19 is not suspected. |

No | ||

| Switzerland Ticino, Berne, Fribourg |

Professional FRs are equipped with PPE. | No * |

AED, automated external defibrillator; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PPE, personal protective equipment. *Countries or regions where an increase in COVID-19 cases (a second wave) has not yet been detected.

Discussion

In this study we described management of FR-programmes in 18 European countries during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most regions temporarily paused activation of citizen responders and professional FRs, or continued activation but with restrictions. The most common restriction was to omit rescue breaths and instead perform compression-only CPR. In regions where activation of professional FRs continued, they were equipped with PPE.

An increase in OHCA with a decrease in survival has been described in two meta-analyses during the COVID-19 pandemic.17, 18 The decrease in survival is still unexplained but is likely dependent on multiple factors such as higher proportion of OHCAs in private homes, longer EMS response time due to increased workload, or a potential fear of starting CPR by bystanders because of risk of virus transmission.15, 16, 19 Knowledge about the risk of coronavirus transmission during resuscitation is still undescribed.20 Aerosol spreading during compression-only CPR has been described in a simulation and a cadaver model,21 but a meta-analysis assessing risk of transmission of SARS-CoV during the SARS outbreaks in 2002–2003 found no significant increase in risk of transmission when performing CPR.22 In Seattle, Sayre et al. estimated a risk of COVID-19 transmission of 10% when performing compression-only CPR. They found that <10% of OHCA patients had COVID-19 which resulted in a theoretical risk of death for rescuers of 1 in 10,000 (with a mortality of 1% for COVID-19).15 Providing FRs with PPE is essential to prevent patient-to-provider transmission but providing PPE to citizen responders is difficult. New guidelines suggest that bystander should place a cloth or use a face mask over the patients nose and mouth to prevent aerosol spread.12 A potential decrease in bystander interventions and AED use is conceivable during the COVID-19.15, 23 Since dispatch of professional FRs and citizen responders has been associated with an increase in bystander CPR and AED use,2, 3, 4, 5 it is important to investigate the consequences of temporarily pausing or restricting FR-programmes for bystander interventions and the effect on patient outcome when evaluating the strategies for prehospital management of OHCA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

ERC guidelines for resuscitation during the COVID-19 pandemic were published on April 24, 2020.12 Most included regions changed recommendations for prehospital management of OHCA in the first months of the COVID-19 outbreak and some even before the ERC guidelines were published. As the pandemic evolved, management changed for all regions and is still under close evaluation as many regions have experienced both a decrease and an increase (a second wave) in COVID-19 prevalence. Most regions kept their FR-programmes paused or with restrictions during the second wave. After the pandemic, information about the importance of bystander CPR and use of AED is crucial to prevent a step back in community engagement for OHCA resuscitation that has been achieved in the last twenty years.

This study provides an overview over management strategies for FR-programmes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. OHCA experts from well-established European networks included in the original 2019 study1 were re-consulted. The aim of the previous study was to identify the most common FR-programmes to provide a basis for understanding the development of FR-programmes at a European level. Therefore, not all FR-programmes on an individual level may have been identified. Moreover, not all countries in Europe were included and our results are therefore not representative for all of Europe. Further, we did not receive specific information about the decision basis for each region’s management and we cannot identify best practice for management of FR-programmes since we did not have information on bystander interventions nor patient outcome. Further studies are therefore needed to investigate the consequences for patient outcome.

Conclusion

Most regions included in this study changed management of FR-programmes to adapt to the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies are needed to investigate the consequences of temporarily pausing or implementing restrictions for FR-programmes on CPR and AED use, and how this may impact patient outcome.

Authors’ contributions

LA: study conception and design, analyses and interpretation of data, writing the manuscript

IO: study conception and design, data collection, analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

FF: study conception and design, analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

CdG: study conception and design, interpretation of data, revision manuscript

RS: analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

JSK: study conception and design, interpretation of data, revision manuscript

CMH: analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

RWK: analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

HLT: analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

MB: study conception and design, analyses and interpretation of data, revision manuscript

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript

Conflict of interest

None declared

Grant support

This work has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under acronym ESCAPE-NET, registered under grant agreement No 733381, and the European Union's COST programme under acronym PARQ, registered under grant agreement No CA19137. Dr. Andelius, Dr. Malta Hansen, Dr. Samsoe Kjoelbye, and Dr. Folke have received research grants from TrygFonden. Dr. Malta Hansen has received research grant from Helsefonden. Dr. Malta Hansen and Dr. Folke have received unrestricted research grants from Laerdal Foundation.

Acknowledgement

We greatly appreciate the contributions of Martin Jonsson (MSc, from Sweden), Anatolij Truhlar (MD, PhD, from the Czech Republic), Michael Baubin (MD, PhD, from Austria), Cristina Granja (MD, PhD, from Portugal), Ari Salo (MD, PhD, from Finland), Siobhan Masterson (PhD, from Ireland), Nicola Dunbar (from England), Enrico Baldi (MD, from Italy [Region of Lombardia]), Federico Semararo (MD, from Italy [Region of Emilia Romagna]), Nagy Enikő (from Hungary), Pascal Stammet (MD, PhD from Luxembourg), Andrej Markota (MD, PhD) and Janez Strnad (MD, PhD) (from Slovenia), Ingvild Tjelmeland (MSc) and Jo Kramer-Johansen (MD, from Norway), Roman Burkart (MD, from Switzerland), Diana Cimpoesu (MD, PhD from Romania) and Dennis Rupp (from Germany) for their cooperation and data collection. Also, we would like to thank all other respondents who so generously shared their expert opinion and knowledge to make this study possible.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2020.100075.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Oving I., Masterson S., Tjelmeland I.B.M., Jonsson M., Semeraro F., Ringh M., Truhlar A., Cimpoesu D., Folke F., Beesems S.G., Koster R.W., Tan H.L., Blom M.T. First-response treatment after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a survey of current practices across 29 countries in Europe. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2019;27:112. doi: 10.1186/s13049-019-0689-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen C.M., Kragholm K., Granger C.B., Pearson D.A., Tyson C., Monk L., Corbett C., Nelson R.D., Dupre M.E., Fosbol E.L., Strauss B., Fordyce C.B., McNally B., Jollis J.G. The role of bystanders, first responders, and emergency medical service providers in timely defibrillation and related outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Results from a statewide registry. Resuscitation. 2015;96:303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zijlstra J.A., Stieglis R., Riedijk F. Smeekes M, van der Worp WE and Koster RW. Local lay rescuers with AEDs, alerted by text messages, contribute to early defibrillation in a Dutch out-of-hospital cardiac arrest dispatch system. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1444–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringh M., Rosenqvist M., Hollenberg J., Jonsson M., Fredman D., Nordberg P., Jarnbert-Pettersson H., Hasselqvist-Ax I., Riva G., Svensson L. Mobile-phone dispatch of laypersons for CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2316–2325. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andelius L., Malta Hansen C., Lippert F.K., Karlsson L., Torp-Pedersen C., Kjær Ersbøll A., Køber L., Collatz Christensen H., Blomberg S.N., Gislason G.H., Folke F. Smartphone Activation of Citizen Responders to Facilitate Defibrillation in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husain S., Eisenberg M. Police AED programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2013;84:1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bækgaard J.S., Viereck S., Møller T.P., Ersbøll A.K., Lippert F., Folke F. The Effects of Public Access Defibrillation on Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Circulation. 2017;136:954–965. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scquizzato T., Pallanch O., Belletti A., Frontera A., Cabrini L., Zangrillo A., Landoni G. Enhancing citizens response to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review of mobile-phone systems to alert citizens as first responders. Resuscitation. 2020;152:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolan J. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 1. Introduction. Resuscitation. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization WH. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Accessed April 4, 2020.

- 11.Perkins G.D., Morley P.T., Nolan J.P., Soar J., Berg K., Olasveengen T., Wyckoff M., Greif R., Singletary N., Castren M., de Caen A., Wang T., Escalante R., Merchant R.M., Hazinski M., Kloeck D., Heriot G., Couper K., Neumar R. International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation: COVID-19 consensus on science, treatment recommendations and task force insights. Resuscitation. 2020;151:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolan J.P., Monsieurs K.G., Bossaert L., Böttiger B.W., Greif R., Lott C., Madar J., Olasveengen T.M., Roehr C.C., Semeraro F., Soar J., Van de Voorde P., Zideman D.A., Perkins G.D. European Resuscitation Council COVID-19 Guidelines Executive Summary. Resuscitation. 2020;153:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J., Rodgers Y.V.M. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savoia E., Argentini G., Gori D., Neri E., Piltch-Loeb R., Fantini M.P. Factors associated with access and use of PPE during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study of Italian physicians. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayre M.R., Barnard L.M., Counts C.R., Drucker C.J., Kudenchuk P.J., Rea T.D., Eisenberg M.S. Prevalence of COVID-19 in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: implications for bystander CPR. Circulation. 2020 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldi E., Sechi G.M., Mare C., Canevari F., Brancaglione A., Primi R., Klersy C., Palo A., Contri E., Ronchi V., Beretta G., Reali F., Parogni P., Facchin F., Rizzi U., Bussi D., Ruggeri S., Oltrona Visconti L., Savastano S. COVID-19 kills at home: the close relationship between the epidemic and the increase of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim Z.J., Ponnapa Reddy M., Afroz A., Billah B., Shekar K., Subramaniam A. Incidence and outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in the COVID-19 era: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scquizzato T., Landoni G., Paoli A., Lembo R., Fominskiy E., Kuzovlev A., Likhvantsev V., Zangrillo A. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan HL How does COVID-19 kill at home and what should we do about it? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3055–3057. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couper K., Taylor-Phillips S., Grove A., Freeman K., Osokogu O., Court R., Mehrabian A., Morley P.T., Nolan J.P., Soar J., Perkins G.D. COVID-19 in cardiac arrest and infection risk to rescuers: a systematic review. Resuscitation. 2020;151:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ott M., Milazzo A., Liebau S., Jaki C., Schilling T., Krohn A., Heymer J. Exploration of strategies to reduce aerosol-spread during chest compressions: A simulation and cadaver model. Resuscitation. 2020;152:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran K., Cimon K., Severn M., Pessoa-Silva C.L., Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marijon E., Karam N., Jost D., Perrot D., Frattini B., Derkenne C., Sharifzadehgan A., Waldmann V., Beganton F., Narayanan K., Lafont A., Bougouin W., Jouven X. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris, France: a population-based, observational study. The Lancet Public health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.