Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the prevalence of depression and loneliness during the US COVID-19 response, and examine their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections.

Methods

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey of a nationally representative sample of American adults (n = 1010), aged 18–94, running from April 10–20, 2020. We assessed depressive symptoms (CES-D-10 scale), loneliness (UCLA 3-Item Loneliness scale), and frequency of in-person and remote social connections (4 items, e.g., hugging family member, video chats) and sexual connections (4 items, e.g., partnered sexual activity, dating app use).

Results

One-third of participants (32%) reported depressive symptoms, and loneliness was high [mean (SD): 4.4 (1.7)]. Those with depressive symptoms were more likely to be women, aged 20–29, unmarried, and low-income. Very frequent in-person connections were generally associated with lower depression and loneliness; frequent remote connections were not.

Conclusions

Depression and loneliness were elevated during the early US COVID-19 response. Those who maintained very frequent in-person, but not remote, social and sexual connections had better mental health outcomes. While COVID-19 social restrictions remain necessary, it will be critical to expand mental health services to serve those most at-risk and identify effective ways of maintaining social and sexual connections from a distance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00127-020-02002-8.

Keywords: Depression, Loneliness, COVID-19, Social isolation, American adults

Introduction

The spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to unprecedented changes in the daily lives of Americans. Measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, including social distancing and sheltering in place, limit people’s ability to maintain social, relational, and sexual connections and, accordingly, may have dramatic consequences for people’s psychological well-being [1, 2]. Social isolation, which is essentially mandated to reduce transmission of COVID-19, has been previously linked to loneliness and negative mental health outcomes in numerous populations [3, 4]. Further, recent research has shown that the spread of COVID-19 and the related public health response have had negative effects on people’s emotional well-being [5–8], with more than one-third of American adults reporting serious changes in their mental health due to the COVID-19 spread and response [9, 10] .

Under normal conditions, depression is common worldwide and has a significant health burden, affecting some 264 million people each year, according to the World Health Organization [11]. Loneliness is also prevalent and strongly correlated with adverse mental and physical health outcomes, including depression [12]. In the United States, depression has increased among adults over the last decade [13], largely among young adults and women [14]. Recent estimates from the National Institute of Mental Health indicate that 17.3 million American adults (7.1%) experienced a major depressive episode in 2017 [15]. Loneliness tends to follow similar demographic trends as depression, with elevated levels observed in women and young adults, but also among low-income and unmarried people [12, 16].

While previous studies have evaluated the psychological consequences of other respiratory disease epidemics [17–20], few studies have been conducted to assess these outcomes related to the current COVID-19 pandemic [5–7]. To our knowledge, no COVID-19-era study has yet estimated the population-representative prevalence of depression and loneliness in American adults. Further, there is limited understanding of how social and sexual connections are associated with mental well-being amidst a global pandemic and the associated containment measures such as quarantine, social distancing, and self-isolation.

This study fills these knowledge gaps by estimating the population-representative prevalence of depression and loneliness in American adults during the early stages of the COVID-19 spread and restrictions, and by examining the frequency of social and sexual connections as potential predictors of these mental health outcomes.

Methods

Study setting, participants, and data collection

We conducted a nationally representative online survey of American adults (age 18 + years) from April 10–20, 2020—the 2020 National Survey of Sexual and Reproductive Health During COVID-19. Participants were recruited into the study using the Ipsos KnowledgePanel, a nationally representative, probability-based sample established using address-based sampling via the U.S. Postal Service’s Delivery Sequence File. Other studies have long used Ipsos Knowledge Panel surveys to underpin high-quality and generalizable results [21–23]. Using an equal probability selection method, members of the panel were sampled and invited to participate in our study. Sampled participants were emailed an invitation and link to an online survey querying information on mental health, relationships, sexual behaviors. Ipsos maintains an incentive program for participation in individual surveys, including sweepstakes/raffles for prizes and cash rewards. Ethical approval for the study protocol was provided by the Indiana University Human Subjects Office (#2004194314).

Key variables

We assessed two key outcomes: depression and loneliness. We measured depression with the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, which queries the frequency of experiencing 10 depressive symptoms in the last week (scale items reproduced in Table S1) [24]. As in other studies [25, 26], we used a scale cutpoint of greater than or equal to 10 to identify those likely experiencing significant depressive symptoms.

We measured loneliness with the UCLA 3-item Loneliness scale, which queries the frequency with which respondents felt that they lacked companionship, felt left out, and felt isolated from others (scale items reproduced in Table S1) [27]. For this survey, we adapted the scale to reference a one month reporting window to align with the timing of the early COVID-19 response. We calculated the continuous scale score (possible range 3–9), and used a score of 4 or greater to define a dichotomous loneliness category for comparison with prior studies [28, 29]. We used a more conservative loneliness definition (score of 6 or greater) for categorization for subsequent analyses. This categorization decision was made to address concerns about the likely lower discriminatory value of one of the scale items (‘How often do you feel isolated from others?’).

As a sensitivity analysis, we also modeled the depression and loneliness outcomes as continuous scale scores to examine the influence of our decisions to dichotomize our key outcomes (Table S2). The results were largely consistent in both direction and magnitude to the primary results with dichotomized outcomes, indicating robustness to this coding decision. Because one of the CESD-10 scale items specifically queries experiences with loneliness, we conducted a second sensitivity analysis removing this item (Table S2). We found generally similar results with and without its exclusion, suggesting that the inclusion of this item is unlikely to be driving any similarities in results observed using the depression and loneliness scales.

We assessed the frequency of eight social and sexual connection exposures with reference to the time frame of the last month, each with response categories: not at all, once or a few times, 1–3 times a week, and almost every day. We grouped the social connections into in-person (hug/kiss a family member, visit a non-household friend or family member) and remote (video chat with friend/family, send/receive a letter in the mail). Similarly, we grouped the sexual connections into in-person (hug/kiss a partner, partnered sexual activities: mutual masturbation, oral sex, or intercourse) and remote (sex over phone, video chat or texting; use of dating or hookup app). Few endorsed these final two remote sexual exposures at high frequency, so for those we combined the ‘1–3 times a week’ and ‘almost every day’ responses. We also assessed relationship tension among participants reporting romantic relationship. We measured romantic tension with an item that queried whether participants noted increased tension or arguments with their partner due to COVID-19 spread and restrictions. We categorized responses into ‘yes’ (often, sometimes, or rarely) and ‘no’ (no significant change, or feeling more connected).

We assessed other key demographic variables with data maintained in the Ipsos KnowledgePanel: gender; age, in years, categorized in 10-year increments; race/ethnicity; marital status; region: northeast, south, Midwest, west; household size, and household makeup (living alone, children under 13 years in home). To assess the potential importance of living with a romantic partner, we created a dichotomous relationship status variable separating participants who lived with a romantic partner from participants who did not live with a romantic partner, either because their romantic partner lived elsewhere or because they did not have a romantic partner.

Statistical analysis

To account for any differential nonresponse that may have produced different distributions between our survey sample and the overall Ipsos KnowledgePanel, all analyses were conducted on a sample weighted to the overall to the geo-demographic distribution of the United States based on US Census data. The magnitude of missing data was < 5% for all variables, so we conducted complete case analyses. We calculated descriptive estimates of the prevalence of depressive symptoms and loneliness, and used chi-square and t tests to assess which categorical and continuous demographic variables differed significantly by depression status. We used log-binomial regression to estimate the associations between each of the nine exposures (frequency of social and sexual connections and relationship tension) and each of the two mental health outcomes (depression and loneliness). We estimated these associations in unadjusted models, and in models adjusted for gender, age, marital status, and income. To examine whether the associations differed by relationship status, we added an interaction term between relationship status and each of the nine exposures, dichotomizing the frequency variables at 1–3 times per week (at or above/below). We estimated stratified results and used the magnitude of differences in point estimates and Wald p values to inform our conclusions around effect measure modification. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.4.

Results

Of the 1632 KnowledgePanel members invited to participate in the study, 1010 completed the survey for a 61.9% response rate. The weighted sample was 52% female, 63% non-Hispanic White, 12% non-Hispanic Black, 16% Hispanic, and 9% other race or multiple races. Most (62%) were married, and one-third (33%) had a college education or higher (Table 1). The demographic differences between the weighted and the unweighted sample were minor. The ages of those in the sample ranged from 18 to 94 years and the weighted median age was 48 years (IQR 32–62).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the unweighted and weighted sample, overall and by depressive symptoms in 1010 American adults, April 10–20, 2020

| Characteristic | Unweighted Overall N = 1010 |

Weighted Overall N = 1010 |

Major depressive symptoms1 N = 304 |

Below threshold for major depressive symptoms1 N = 657 |

Test statistic2 | p value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 516 (51.1) | 521 (51.6) | 179 (58.9) | 315 (47.9) | 10.01 | 0.002 |

| Male | 494 (48.9) | 489 (48.4) | 125 (41.1) | 342 (52.1) | ||

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–19 | 15 (1.5) | 27 (2.7) | 10 (3.4) | 14 (2.2) | 29.64 | < 0.0001 |

| 20–29 | 114 (11.3) | 184 (18.2) | 76 (24.9) | 99 (15.1) | ||

| 30–39 | 156 (15.5) | 175 (17.4) | 55 (17.9) | 106 (16.1) | ||

| 40–49 | 138 (13.7) | 142 (14.1) | 45 (14.6) | 92 (14.0) | ||

| 50–59 | 215 (21.3) | 185 (18.3) | 59 (19.4) | 119 (18.1) | ||

| 60–69 | 206 (20.4) | 165 (16.3) | 33 (10.9) | 126 (19.3) | ||

| 70–79 | 129 (12.8) | 103 (10.2) | 23 (7.6) | 76 (11.6) | ||

| 80 + | 37 (3.7) | 28 (2.8) | 3 (1.1) | 24 (3.7) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 721 (71.4) | 639 (63.2) | 182 (59.7) | 434 (66.1) | 3.87 | 0.3 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 85 (8.4) | 119 (11.8) | 41 (13.6) | 71 (10.8) | ||

| Other or 2 + races, non-Hispanic | 81 (8.0) | 87 (8.6) | 29 (9.6) | 53 (8.1) | ||

| Hispanic | 123 (12.2) | 165 (16.4) | 52 (17.2) | 99 (15.1) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or living with partner | 668 (66.1) | 622 (61.6) | 152 (50.0) | 444 (67.5) | 32.36 | < 0.0001 |

| Separated/divorced | 129 (12.8) | 124 (12.3) | 40 (13.1) | 76 (11.6) | ||

| Widowed | 44 (4.4) | 40 (3.6) | 14 (4.6) | 23 (3.6) | ||

| Never married | 169 (16.7) | 224 (22.2) | 98 (32.3) | 114 (17.3) | ||

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 189 (18.7) | 177 (17.5) | 52 (17.1) | 111 (17.0) | 0.9641 | 0.8 |

| Midwest | 228 (22.6) | 210 (20.8) | 66 (21.6) | 134 (20.4) | ||

| South | 341 (33.8) | 383 (37.9) | 110 (36.1) | 258 (39.2) | ||

| West | 252 (25.0) | 240 (23.8) | 77 (25.2) | 154 (23.4) | ||

| Household income | ||||||

| < $25 k | 95 (9.4) | 136 (13.5) | 61 (20.2) | 69 (10.6) | 25.94 | 0.0005 |

| $25-49 k | 174 (17.2) | 184 (18.2) | 54 (17.7) | 120 (18.3) | ||

| $50-74 k | 183 (18.1) | 174 (17.2) | 57 (18.6) | 105 (15.9) | ||

| $75-99 k | 147 (14.6) | 141 (14.0) | 32 (10.5) | 105 (16.0) | ||

| $100-124 k | 108 (10.7) | 103 (10.3) | 33 (10.8) | 67 (10.2) | ||

| $125-149 k | 73 (7.2) | 66 (6.5) | 112 (3.8) | 52 (7.9) | ||

| $150-174 k | 90 (8.9) | 82 (8.1) | 25 (8.1) | 53 (8.0) | ||

| $175 k + | 140 (13.9) | 124 (12.3) | 32 (10.4) | 86 (13.1) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 75 (7.4) | 98 (9.7) | 39 (12.7) | 52 (7.9) | 5.68 | 0.1 |

| High school | 278 (27.5) | 295 (29.2) | 83 (27.4) | 186 (28.4) | ||

| Some college | 273 (27.0) | 281 (27.8) | 85 (28.1) | 189 (28.7) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 384 (38.0) | 336 (33.3) | 97 (31.9) | 230 (35.0) | ||

| Children in home (< 13 years) | ||||||

| Yes | 194 (19.2) | 223 (22.0) | 67 (22.0) | 145 (22.0) | 0.99 | 1.0 |

| No | 816 (80.8) | 787 (78.0) | 238 (78.0) | 512 (78.0) | ||

| Living alone | ||||||

| Yes | 190 (18.8) | 184 (18.2) | 66 (21.5) | 107 (16.3) | 3.87 | 0.05 |

| No | 820 (81.2) | 826 (81.8) | 239 (78.5) | 550 (83.7) | ||

| Household size | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.65 (1.50) | 2.77 (1.60) | 2.72 (1.66) | 2.81 (1.58) | 0.86 | 0.4 |

| Loneliness scale3 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.31 (1.69) | 4.37 (1.74) | 5.48 (2.08) | 3.90 (1.33) | − 14.36 | < 0.0001 |

SD standard deviation

1Major depressive symptoms measured with the CES-D-10 scale. Possible scores range 0–30. The frequency of missing data for this variable was n = 44 (4.4%)

2Test statistics and associated P values are chi-square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables

3Loneliness measured with the UCLA 3-Item Loneliness scale. Possible scores ranged 3–9. The frequency of missing observations for this variable was n = 19 (1.9%)

The weighted prevalence of major depressive symptoms in the last week was 31.7% (95% CI 28.9, 34.8%). People reporting major depressive symptoms were more likely to be women, age 20–29, unmarried, in the lowest income bracket, and living alone compared to people not reporting major depressive symptoms. Loneliness scale scores were also significantly higher among those with major depressive symptoms [mean (SD) 5.5 (2.1)], than among those without [mean (SD) 3.9 (1.3)]. The weighted prevalence of loneliness was 54.0% (95% CI 51.0, 57.2%) using our first definition, and 23.8% (95% CI 21.3, 26.6%) using our second definition.

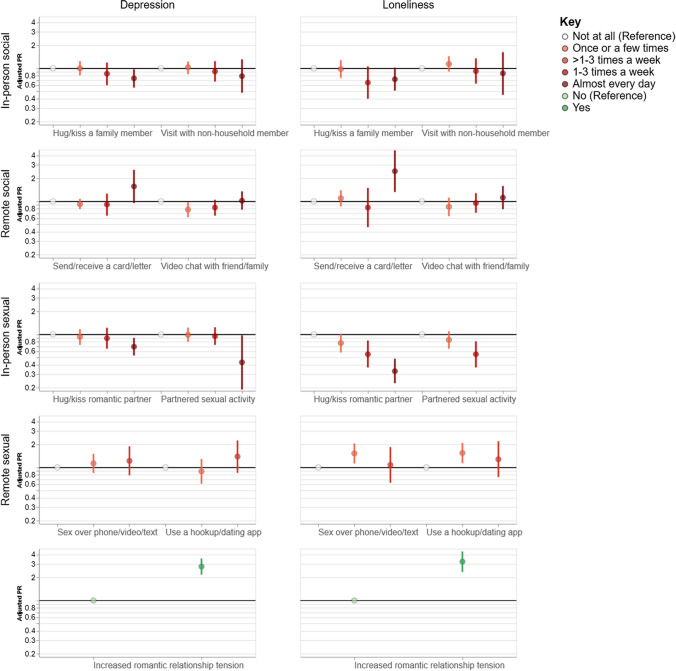

Very frequent in-person social connections generally trended toward an association with lower depression and loneliness prevalence, but very frequent remote social connections did not (Table 2, Fig. 1). Compared to those who reported ‘not at all,’ people who hugged or kissed a family member almost every day in last month were 26% less likely to report major depressive symptoms [aPR (95% CI) 0.74 (0.56, 0.97)], and 28% less likely to report loneliness [aPR (95% CI) 0.72 (0.51, 1.02)]. Though not statistically significant, we observed similar trends for the exposure of in-person visits with non-household members [aPRdepression (95% CI) 0.79 (0.48, 1.31) and aPRloneliness (95% CI) 0.86 (0.51, 1.02)]. This trend was not observed for remote social connections (video chats and sending/receiving letters in the mail). Relative to ‘not at all’ responses, high frequency of video chats were not associated with lower depression or loneliness prevalence [aPR (95% CI) 1.02 (0.78, 1.35) and aPR (95% CI) 1.12 (0.79, 1.59), respectively], whereas those with high frequency of sending/receiving letters tended towards higher depression and loneliness [aPR (95% CI) 1.57 (0.95, 2.59) and aPR (95% CI) 2.49 (1.33, 4.65), respectively]. However, at more infrequent levels (once or a few times in the last month), video chats were associated with lower prevalence of depressive symptoms [aPR (95% CI) 0.78 (0.62, 0.98)].

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted log-binomial regression for the associations between frequency of social and sexual connections and outcomes of depression and loneliness

| Exposure variables | Weighted N (%) | Depressive symptoms | Loneliness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | PR (95%CI) | aPR1 (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) | PR (95% CI) | aPR1 (95% CI) | ||

| In-person social connection in last month | |||||||

| Hug or kiss a family member (not partner) | |||||||

| Not at all | 519 (51.6) | 32.5 | 1 | 1 | 26.4 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 196 (19.5) | 37.1 | 1.14 (0.91, 1.43) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) | 26.8 | 1.01 (0.77, 1.34) | 0.98 (0.75, 1.28) |

| 1–3 times a week | 84 (8.4) | 31 | 0.95 (0.67, 1.36) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.19) | 17.2 | 0.65 (0.40, 1.07) | 0.65 (0.40, 1.06) |

| Almost every day | 206 (20.5) | 24.9 | 0.77 (0.58, 1.00) | 0.74 (0.56, 0.97) | 17.1 | 0.65 (0.46, 0.90) | 0.72 (0.51, 1.02) |

| Missing | n = 6 | ||||||

| In-person visit with non-household member | |||||||

| Not at all | 499 (49.8) | 30.4 | 1 | 1 | 21.9 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 353 (35.3) | 34.3 | 1.13 (0.93, 1.38) | 1.03 (0.84, 1.23) | 27.7 | 1.26 (1.00, 1.60) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.44) |

| 1–3 times a week | 110 (10.9) | 29.8 | 0.98 (0.71, 1.36) | 0.91 (0.67, 1.24) | 21.4 | 0.98 (0.66, 1.45) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.35) |

| Almost every day | 40 (4.0) | 28.5 | 0.94 (0.56, 1.58) | 0.79 (0.48, 1.31) | 20 | 0.91 (0.47, 1.76) | 0.86 (0.45, 1.63) |

| Missing | n = 9 | ||||||

| Remote social connection in last month | |||||||

| Send or receive a card or letter in the mail | |||||||

| Not at all | 614 (61.2) | 33.5 | 1 | 1 | 24.3 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 322 (32.2) | 27.4 | 0.82 (0.66, 0.99) | 0.92 (0.79, 1.08) | 23 | 0.94 (0.74, 1.21) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.40) |

| 1–3 times a week | 52 (5.2) | 26.6 | 0.79 (0.50, 1.27) | 0.91 (0.65, 1.26) | 17.8 | 0.73 (0.40, 1.33) | 0.83, 0.46, 1.50) |

| Almost every day | 14 (1.4) | 70 | 2.09 (1.45, 3.00) | 1.57 (0.95, 2.59) | 45.8 | 1.88 (1.01, 3.50) | 2.49 (1.33, 4.65) |

| Missing | n = 7 | ||||||

| Video chat with friend/family member | |||||||

| Not at all | 328 (32.8) | 33.8 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 321 (32.0) | 28.1 | 0.83 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98) | 21.6 | 0.86 (0.65, 1.15) | 0.85, 0.64, 1.12) |

| 1–3 times a week | 239 (23.8) | 30.7 | 0.91 (0.71, 1.16) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.05) | 23.7 | 0.95 (0.71, 1.28) | 0.95 (0.71, 1.28) |

| Almost every day | 114 (11.4) | 38 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.49) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.35) | 27 | 1.08 (0.76, 1.55) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.59) |

| Missing | n = 8 | ||||||

| In-person sexual connection in last month | |||||||

| Hug or kiss romantic partner | |||||||

| Not at all | 333 (33.4) | 37.9 | 1 | 1 | 37.1 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 179 (18.0) | 35.3 | 0.93 (0.73, 1.19) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.17) | 27.5 | 0.74 (0.56, 0.98) | 0.77 (0.58, 1.02) |

| 1–3 times a week | 116 (11.7) | 32.4 | 0.86 (0.63, 1.16) | 0.89 (0.65, 1.22) | 20.5 | 0.55 (0.38, 0.81) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.83) |

| Almost every day | 370 (37.0) | 23.9 | 0.63 (0.50, 0.80) | 0.69 (0.53, 0.90) | 11.3 | 0.31 (0.22, 0.42) | 0.33 (0.23, 0.48) |

| Missing | n = 12 | ||||||

| Partnered sexual activity2 | |||||||

| Not at all | 518 (53.0) | 32.7 | 1 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 240 (24.5) | 32.9 | 1.01 (0.80, 1.26) | 0.99 (0.80, 1.23) | 24 | 0.83 (0.63, 1.08) | 0.85 (0.65, 1.10) |

| 1–3 times a week | 186 (19.0) | 30.4 | 0.93 (0.72, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.73, 1.24) | 14.8 | 0.51 (0.35, 0.74) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.81) |

| Almost every day | 34 (3.5) | 15.1 | 0.46 (0.20, 1.05) | 0.43 (0.19, 0.97) | 0 | *** | *** |

| Missing | n = 33 | ||||||

| Remote sexual connection in last month | |||||||

| Sex over phone, video chat, or texting3 | |||||||

| Not at all | 888 (90.9) | 30.7 | 1 | 1 | 22.2 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 63 (6.4) | 45 | 1.47 (1.09, 1.97) | 1.13 (0.85, 1.51) | 42.4 | 1.91 (1.40, 2.61) | 1.55 (1.14, 2.10) |

| > 1–3 times a week | 26 (2.6) | 43 | 1.41 (0.87, 2.24) | 1.22 (0.79, 1.89) | 32.9 | 1.48 (0.84, 2.61) | 1.28 (0.75, 2.21) |

| Missing | n = 33 | ||||||

| Use a hookup or dating app3 | |||||||

| Not at all | 947 (94.3) | 30.7 | 1 | 1 | 22.8 | 1 | 1 |

| Once or a few times | 34 (3.4) | 39.5 | 1.29 (0.82, 2.01) | 0.89 (0.61, 1.29) | 26.5 | 1.16 (0.65, 2.06) | 0.76 (0.43, 1.34) |

| > 1–3 times a week | 23 (2.3) | 62.5 | 2.04 (1.47, 2.83) | 1.39 (0.85, 2.26) | 59.5 | 2.61 (1.83, 3.72) | 2.08 (1.49, 2.89) |

| Missing | n = 6 | ||||||

| Increased romantic relationship tension4 | |||||||

| No | 492 (66.3) | 16.8 | 1 | 1 | 10.7 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 250 (33.7) | 51.3 | 3.06 (2.42, 3.87) | 2.79 (2.19, 3.55) | 33.8 | 3.16 (2.32, 4.31) | 3.23 (2.37, 4.39) |

| Missing | n = 4 | ||||||

PR prevalence ratio, aPR adjusted prevalence ratio, CI confidence interval

1Covariates are age, gender, marital status, and income

2Partnered sexual activity defined as mutual masturbation, oral sex, or intercourse

3Few people reported sex over the phone, video chat, or texting (n = 3) and using hookup or dating app (n = 11) every day, so we combined this category with 1–3 times a week for the most frequent category

4Restricted to those who reported a romantic partner (weighted n = 746)

Fig. 1.

Associations between frequencies of social and sexual connections and outcomes of depressive symptoms (left panel) and loneliness (right panel) in 1010 American adults, April 10–20, 2020. Circles indicate adjusted prevalence ratios and bars indicate 95% confidence intervals

Similarly, very frequent in-person sexual connections generally trended toward associations with lower prevalence of depression and loneliness in ways that remote sexual connections did not (Table 2, Fig. 1). For the hug/kiss and partnered sex exposures, a dose–response relationship was observed where, relative to ‘not at all’ responses, increasing frequencies were associated with decreased depression and loneliness prevalence. Those who endorsed the most frequent hug/kiss exposure were 31% less likely to report depressive symptoms and 67% less likely to report loneliness [aPR (95% CI) 0.69 (0.53, 0.90) and aPR (95% CI) 0.33 (0.23, 0.48), respectively]. Those who endorsed the most frequent partnered sex exposure were 57% less likely to report depressive symptoms [aPR (95% CI) 0.43 (0.19, 0.97)]. No participant with partnered sex at this high frequency had loneliness scores above 6. Relatively few participants endorsed very frequent remote sex or dating app usage, but those who did tended to have higher rates of depression and loneliness. However, these estimates were measured imprecisely with wide confidence limits often spanning the null. Participants who endorsed experiencing increased tension with their romantic partner due to COVID-19 spread and restrictions were more likely to report major depressive symptoms [aPR (95% CI) 2.79 (2.19, 3.55)] and loneliness [aPR (95% CI) 3.23 (2.37, 4.39)].

The patterns for the associations between social and sexual connections and mental health outcomes generally did not differ depending on if the participant lived with a romantic partner (Table 3). One possible exception to this trend emerged for the remote sex over phone, video chat, or texting outcome, though the low numbers of participants reporting this exposure frequently limited the precision of our estimates. For participants who lived with a partner, more frequent remote sex was associated with lower depression and loneliness [aPR (95% CI) 0.89 (0.38, 2.07) and aPR (95% CI) 0.34 (0.04, 2.70), respectively], while the opposite was true for participants who did not live with a partner [aPR (95% CI) 1.66 (0.97, 2.84) and aPR (95% CI) 1.45 (0.85, 2.48), respectively, Wald p values for interaction both = 0.2].

Table 3.

Adjusted log-binomial regression for the associations between frequency of social and sexual connections and outcomes of depression and loneliness, stratified by sexual relationship type (living with partner vs not living with partner)

| Exposure variables | Depressive symptoms | p value | Loneliness | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live with a partner aPR1 (95%CI) | Do not live with a partner aPR1 (95% CI) | Wald value for interaction | Live with a partner aPR1 (95%CI) | Do not live with a partner aPR1 (95% CI) | Wald value for interaction | |||

| In-person social connection in last month | ||||||||

| Hug or kiss a family member (not partner) | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 1.76 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.6 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 0.68 (0.50, 0.91) | 0.91 (0.66, 1.25) | 0.63 (0.41, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.50, 1.07) | ||||

| In-person visit with non-household member | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 0.14 | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | 0.20 | 0.6 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 0.94 (0.65, 1.37) | 0.85 (0.59, 1.24) | 0.91 (0.53, 1.55) | 0.77 (0.51, 1.18) | ||||

| Remote social connection in last month | ||||||||

| Send or receive a card or letter in the mail | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 0.29 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.5 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 1.23 (0.79, 1.91) | 1.47 (0.92. 2/34) | 1.39 (0.78, 2.48) | 1.00 (0.48, 2.07) | ||||

| Video chat with friend/family member | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.3 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 0.93 (0.72, 1.21) | 0.94 (0.65, 1.36) | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58) | ||||

| In-person sexual connection in last month | ||||||||

| Hug or kiss romantic partner | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 1.86 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.5 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 0.68 (0.52, 0.89) | 0.94 (0.64, 1.38) | 0.44 (0.31, 0.64) | 0.56 (0.32, 0.97) | ||||

| Partnered sexual activity2 | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 1.24 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 | 0.4 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 0.81 (0.61, 1.08) | 1.12 (0.69, 1.82) | 0.48 (0.30, 0.76) | 0.71 (0.35, 1.43) | ||||

| Remote sexual connection in last month | ||||||||

| Sex over phone, video chat, or texting3 | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 1.49 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 1.76 | 0.2 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 0.89 (0.38, 2.07) | 1.66 (0.97, 2.84) | 0.34 (0.04, 2.71) | 1.45 (0.85, 2.48) | ||||

| Use a hookup or dating app3 | ||||||||

| < 1–3 times a week | 1 | 1 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 1 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.6 |

| 1–3 times a week or more | 1.61 (0.88, 2.95) | 1.67 (1.13, 2.48) | 1.79 (0.71, 4.49) | 2.28 (1.62, 3.22) | ||||

| Increased romantic relationship tension4 | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 3.14 | 0.08 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 3.16 (2.39, 4.17) | 2.00 (1.30, 3.08) | 3.26 (2.23, 4.74) | 3.27 (1.95, 5.47) | ||||

aPR adjusted prevalence ratio, CI confidence interval

1Covariates are age, gender, and income. Marital status excluded because of overlapping definition with stratifying variable

2Partnered sexual activity defined as mutual masturbation, oral sex, or intercourse

3Few people reported sex over the phone, video chat, or texting (n = 3) and using hookup or dating app (n = 11) every day, so we combined this category with 1–3 times a week for the most frequent category

4Restricted to those who reported a romantic partner (weighted n = 746)

Discussion

In a nationally representative probability survey of American adults taking place during the early phases of the COVID-19 response (April 2020), we found high levels of significant depressive symptoms and loneliness. Very frequent in-person social and sexual contacts during the time of COVID-19 restrictions in the last month were generally associated with lower prevalence of depression and loneliness, while remote contacts were not similarly protective. We also found that relationship tension due to COVID-19 spread and restrictions was strongly predictive of depression and loneliness. Our findings suggest that the COVID-19 spread and response has had a tremendous mental health impact on Americans.

We found that nearly one-third of Americans reported depressive symptoms in April 2020, notably much higher than previous estimates among American adults. From 2013 to 2016, the prevalence of major depression in a given 2 week period in US adults age 20 + years was 8%, nearly 4 times lower than our estimate [30]. Similarly, the mean loneliness score we found (4.4) was higher than prior estimates in three western European countries (3.5–3.7) [31], and the prevalence of loneliness we found in our general US population (Definition 1: 54%), is a similar magnitude as previously observed in older and elderly Americans (43–56%) [28, 29]. Patterns of higher depression prevalence among women, young adults, and people with lower incomes have been observed in previous studies [14, 30]. We also observed these gender, age, and socioeconomic patterns in our study, suggesting that while the magnitude of depression may be expanding during the time of COVID-19 spread and restrictions, the disproportionate burden continues to be felt in these populations.

The observed relationships between social and sexual connections and the outcomes of depression and loneliness are largely consistent with our understanding of the importance of human connection for mental health and well-being. Close touching in family interactions and among relationship partners has been associated with decreased heart rate, higher levels of oxytocin, and lower levels of cortisol [32, 33]; which, in turn could provide important mental health protections. These kinds of connections cannot easily be recreated with remote technology where direct touch is not possible, though some researchers have explored this through “huggable” and other similar communication devices [34]. We also know that common technical difficulties with video calls can cause misattributed negative feelings towards people on the call [35], perhaps contributing to the null effects we observed for remote connections and mental health outcomes. As the COVID-19 spread and response have dramatically limited access to many previously routine and familiar options for human connection, our findings are consistent with an explanation that the decreased frequency of social and sexual connections is contributing to poor mental health outcomes. In addition to limiting people’s social interactions, restrictions have also likely resulted in many people missing counseling or therapy appointments or other activities (e.g., exercise, massage, support group meetings, etc.) that may have been supportive of their mental health.

There are several other plausible explanations for the observed relationship between social and sexual connections and mental health outcomes. First, people who are struggling with poor mental health and feelings of isolation during COVID-19 restrictions may be reaching out more frequently for remote connections. As this was a cross-sectional study, our ability to infer temporality is limited. Future studies with a longitudinal design would be better able to disentangle the temporal relationships between social/sexual connections and mental health outcomes. Second, we used self-reported data for our key exposure and outcome assessments, with the potential for biased results. However, web-based surveys have shown to be effective modes to elicit sensitive sexual behaviors from study participants, alleviating some of the bias concern [36]. Similarly, our depression and loneliness scales are widely used in web-based surveys, are validated, and have good psychometric properties [24, 27]. However, their use could be complemented with clinical assessments in future studies. Relatedly, it is not yet known how these scales perform during times of social restrictions when daily lives have shifted so dramatically. It is possible that the wording of certain items (e.g., ‘How often do you feel isolated from others?’) may lose their discriminatory ability in times where isolation is essentially mandated. For this reason, we used a more conservative categorical definition of loneliness for our analyses than has been commonly used in prior studies. We also did not explore whether participants had run out of prescription medication supportive of their mental health or had missed counseling or therapy visits.

A key strength of this study is its external validity. Our findings are broadly representative of the US adult population during the early stages of the US COVID-19 response. However, these results may not hold during later phases of the COVID-19 response, or for countries outside of the US. Surveys should be conducted at frequent intervals and in other countries affected by COVID-19 to update our understanding of the changing mental health landscape across time and space.

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms and loneliness are being experienced at very high levels in Americans during the COVID-19 spread and response. At this time, social restrictions are a critical tool to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and its associated morbidity and mortality. Our findings should not be interpreted in support of prematurely lifting these necessary restrictions. Rather, public health and mental health professionals should be aware of the increasing mental health needs that are likely co-occurring with the COVID-19 response, and funding should be allocated to expand mental health services to those most likely to be experiencing poor mental health. Women, young adults, and low-income Americans seem to be particularly at-risk for these outcomes. We also found that Americans who could maintain very frequent in-person social and sexual connections appeared to have better mental health outcomes, though remote connections did not appear to confer the same benefits. Given that extra-household connections are not advised at this time and possibly will be contraindicated intermittently in the future, a mental health priority should be to identify innovative and effective ways of supporting interpersonal connections from a distance.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MR and DH conceived the study. DH, MR, ML, and DH designed the survey. MR conducted the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with key drafting contributions from ML and scientific contributions from DH, TF, and DH. SK created the data visualization. MR, ML, DH, TF, SK, and DH contributed to the interpretation of the findings, critical review of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding

The 2020 National Survey of Sexual and Reproductive Health During COVID-19 (NSRHDC) was generously supported by grants from Pure Romance as well the Indiana University Office of the Vice Provost for Research.

Data availability

Data available from first author upon request.

Code availability

Code available from first author upon request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the study protocol was provided by the Indiana University Human Subjects Office (#2004194314).

References

- 1.Holmes EA et al. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews T, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(3):339–348. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor HO, et al. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30(2):229–246. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barari S et al. (2020) Evaluating COVID-19 public health messaging in Italy: self-reported compliance and growing mental health concerns

- 6.Hou Z et al. (2020) Assessment of public attention, risk perception, emotional and behavioural responses to the COVID-19 outbreak: social media surveillance in China

- 7.Li S et al. (2020) The impact of COVID-19 Epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: a study on active weibo users. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jackson C, Newall M, Americans Adapting to the Coronavirus Pause. 2020 [cited 2020 April 28]. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/axios-ipsos-coronavirus-index

- 9.Kirzinger A et al. (2020) KFF Health Tracking Poll—Early April 2020: the Impact Of Coronavirus On Life In America. [cited 2020 April 28]. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/report/kff-health-tracking-poll-early-april-2020/

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. New Poll: COVID-19 Impacting Mental Well-Being: Americans Feeling Anxious, Especially for Loved Ones; Older Adults are Less Anxious. 2020 [cited 2020 April 28]. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-americans-feeling-anxious-especially-for-loved-ones-older-adults-are-less-anxious

- 11.GBD Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce LD, et al. Loneliness in the United States: a 2018 national panel survey of demographic, structural, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics. Am J Health Promot. 2019;33(8):1123–1133. doi: 10.1177/0890117119856551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu B, et al. Trends in depression among Adults in the United States, NHANES 2005–2016. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twenge JM, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185–199. doi: 10.1037/abn0000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Mental Health. Major Depression. 2019 April 28, 2020]. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml

- 16.Das A. Loneliness does (not) have cardiometabolic effects: a longitudinal study of older adults in two countries. Soc Sci Med. 2019;223:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cowling BJ, et al. Community psychological and behavioral responses through the first wave of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(6):867–876. doi: 10.1086/655811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu X et al. (2008) Changes in emotion of the Chinese public in regard to the SARS period. 36(4): 447–454

- 19.Chong MY, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127–133. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuishi K, et al. Psychological impact of the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on general hospital workers in Kobe. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;66(4):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2012.02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson A, et al. The next generation of users: prevalence and longitudinal patterns of tobacco use among US young adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1429–1436. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall JP, et al. Effect of Medicaid expansion on workforce participation for people with disabilities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):262–264. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai J, et al. Homelessness among a nationally representative sample of US veterans: prevalence, service utilization, and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(6):907–916. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1210-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohout FJ, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andresen EM, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. Am J Prev Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W et al. (2012) Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PloS One 7(7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hughes ME, et al. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1078–1084. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: the impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1013–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes JP, Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013-2016. 2018: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- 31.Rico-Uribe LA, et al. Loneliness, social networks, and health: a cross-sectional study in three countries. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0145264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon I, et al. Oxytocin, cortisol, and triadic family interactions. Physiol Behav. 2010;101(5):679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Field T. Touch for socioemotional and physical well-being: a review. Dev Rev. 2010;30(4):367–383. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumioka H, et al. Huggable communication medium decreases cortisol levels. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/srep03034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenenberg K, Raake A, Koeppe J. Why are you so slow?–Misattribution of transmission delay to attributes of the conversation partner at the far-end. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2014;72(5):477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burkill S et al. (2016) Using the web to collect data on sensitive behaviours: a study looking at mode effects on the British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. PloS One 11(2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available from first author upon request.

Code available from first author upon request.