Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global threat to women’s health and may be elevated among those exposed to traumatic events in post-conflict settings, such as Liberia. The purpose of this study was to examine potential mediators between lifetime exposure to traumatic events (i.e., war-related trauma, community violence) with recent experiences of IPV among 183 young, pregnant women in Monrovia, Liberia. Hypothesized mediators included mental health (depression, posttraumatic stress symptoms), insecure attachment style (anxious and avoidant attachment), and attitudes indicative of norms of violence (attitudes justifying wife beating). We tested a parallel multiple mediation model using the PROCESS method with bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping to test confidence intervals (CI). Results show that 45% of the sample had experienced any physical, sexual, or emotional IPV in their lifetime, and 32% in the 2 months prior to the interview. Exposure to traumatic events was positively associated with recent IPV severity (β = .40, p < .01). Taken together, depression, anxious attachment style, and justification of wife beating significantly mediated the relationship between exposure to traumatic events and experience of IPV (β = .15, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.31]). Only anxious attachment style (β = .07, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.16]) and justification of wife beating (β = .05, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.16]) were identified as individual mediators. This study reinforces pregnancy as an important window for both violence and mental health screening and intervention for young Liberian women. Furthermore, it adds to our theoretical understanding of mechanisms in which long-term exposure to traumatic events may lead to elevated rates of IPV in Liberia, and points to the need for trauma-informed counseling and multilevel gender transformative public health approaches to address violence against women.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, trauma, mental health, women, pregnancy, Liberia

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health problem with severe consequences for physical, sexual, mental, and social wellness (World Health Organization [WHO], 2017). A total of 30% of ever-partnered women experience IPV in their lifetime (WHO, 2017), making IPV a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality for women globally. Moreover, it is well documented that IPV is associated with a myriad of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, and suicide attempts (Devries et al., 2014; Devries et al., 2013; Kessler et al., 2017). IPV has also been linked to poor reproductive health outcomes, such as unintended pregnancy, infant morbidity and mortality, sexually transmitted infections, and HIV (Li et al., 2014; Pallitto et al., 2013; Sarkar, 2008). Although IPV is one of the most common forms of violence against women occurring across settings and cultures (WHO, 2017), it is especially elevated in low-resource countries that are recovering from conflict-related violence, trauma, and disease outbreaks, such as Liberia (Kelly, Colantuoni, Robinson, & Decker, 2018; Rubenstein, Lu, MacFarlane, & Stark, 2017; Stark & Ager, 2011).

Understanding Liberia’s history of civil war, political instability, and disease outbreak is central to understanding the country’s high prevalence of IPV. Between 1989 and 2003, civil war displaced a third of the population and resulted in 250,000 deaths (Ellis, 2006). The civil conflict was characterized by widespread violence and infractions against humanity (National Transitional Government of Liberia, 2004), including killing, torture, forced labor, rape, sexual assault, and forced marriages (Annan, Blattman, Mazurana, & Carlson, 2008; Liebling-Kalifani et al., 2011). Violence against women reached unprecedented levels during the civil war. Reports estimate that up to 70% of women in Liberia have experienced some form of gender-based violence in their lifetime, with intimate partners reported as the perpetrators of more than 95% of reported gender-based violence cases (Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, National AIDS Control Program, & Macro International Inc, 2008; Stark & Ager, 2011). Similar to other conflict-affected settings such as Uganda, Thailand, Palestine, Sierra Leone, and Côte d’Ivoire (Annan & Brier, 2010; Clark et al., 2010; Falb, McCormick, Hemenway, Anfinson, & Silverman, 2013; Gupta et al., 2014; Gupta, Reed, Kelly, Stein, & Williams, 2012; Saile, Neuner, Ertl, & Catani, 2013), Liberian women and men who have experienced higher levels of conflict-related violence/trauma also report higher levels of IPV victimization and perpetration, respectively, both during and after conflict (Kelly et al., 2018; Vinck & Pham, 2013). These associations have been observed even 10 years post-conflict in Liberia (Vinck & Pham, 2013).

In addition to exposure to conflict-related trauma, Liberians have also endured trauma related to the more recent 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic. The epidemic devastated Liberia, resulting in 10,678 suspected and laboratory-confirmed cases, approximately 4,810 deaths, and widespread fear and stigma (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017; Van Bortel et al., 2016). Fear of contagion, the loss of loved ones, separation from family, and exposure to mass death was experienced by those in areas affected by the epidemic (Rabelo et al., 2016; Schwerdtle, De Clerck, & Plummer, 2017). The epidemic also resulted in a rise in community violence (Cohn & Kutalek, 2016; Cousins, 2018). Although not systematically monitored, multinational organizations reported an increase in gender-based violence in Liberia and other Ebola-affected countries during and after the epidemic (Korkoyah & Wreh, 2015). Thus, exposure to trauma associated with the Ebola epidemic could have similar population-level effects as conflict-related trauma on IPV incidence.

Collectively, the trauma associated with the occurrence of multiple devastating events may have lasting effects on the incidence of IPV in Liberia. However, explorations of pathways between exposure to traumatic events with IPV in post-conflict settings are limited. Among the complex multilevel pathways theorized (Devakumar, Birch, Osrin, Sondorp, & Wells, 2014; Kinyanda et al., 2016; Levy, 2002; Mootz, Stabb, & Mollen, 2017), mental health outcomes are one mechanism for further investigation. In Liberia, individuals exposed to war-related traumatic events report high rates of depression and PTSD, which in some cases have persisted long after the end of conflict (Galea et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2008; Rockers, Kruk, Saydee, Varpilah, & Galea, 2010; Vinck & Pham, 2013). High rates of depression, PTSD, and psychological distress have also been observed among Ebola survivors (Rabelo et al., 2016; Schwerdtle et al., 2017). These mental health outcomes, in turn, have been found to be risk factors for IPV victimization and perpetration in non-conflict settings (Reingle, Jennings, Connell, Businelle, & Chartier, 2014; Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004; Yakubovich et al., 2018). While there are less studies focused in conflict-affected settings, a few studies associate negative mental health outcomes and risk of IPV in post-conflict settings (J. Gupta et al., 2014; Kinyanda et al., 2016; Rees et al., 2016; Usta, Farver, & Zein, 2008). In particular, one study found that childhood trauma, and PTSD, depression, and disability together mediated conflict-related trauma exposure and IPV among Afghan women (Jewkes, Corboz, & Gibbs, 2018).

Relationship and family dynamics are changed by exposure to community violence and associated traumatic events. Intergenerational effects include changes to family structure and stability (Levey et al., 2017), increased perpetration of child abuse and neglect (Catani, 2010; Crombach & Bambonyé, 2015), and diminished parental capacity and mental health (Berckmoes, De Jong, & Reis, 2017; Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, & Brennan, 2015; Panter-Brick, Grimon, & Eggerman, 2014). These factors and other forms of interpersonal trauma are considered risk factors for the development of insecure attachment, including anxious and avoidant attachment in adulthood in developed settings, refugee populations, and war-affected populations (Dalgaard, Todd, Daniel, & Montgomery, 2016; Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, & Holland, 2013; Morina, Schnyder, Schick, Nickerson, & Bryant, 2016; Widom, Czaja, Kozakowski, & Chauhan, 2018). Anxious attachment is characterized by fear of rejection and abandonment in intimate relationships, while avoidant attachment is characterized by discomfort with intimacy and the desire for independence. Although evidence is mixed (Velotti, Beomonte Zobel, Rogier, & Tambelli, 2018), both attachment styles have been linked to an increased likelihood of IPV victimization, revictimization, and perpetration in developed settings (Doumas, Pearson, Elgin, & McKinley, 2008; Lewis et al., 2017; McClellan & Killeen, 2000; Sandberg, Valdez, Engle, & Menghrajani, 2019). Thus, for young women in Liberia who grew up during and post-civil war, attachment style could be an additional mechanism explaining the relationship between lifetime exposure to traumatic events and recent experience of IPV.

In addition, exposure to gender-based violence and other forms of mass violence have lasting effects on gender inequitable norms and the acceptance of violence against women. Liberia ranked 154 out of 160 countries on the United Nations 2017 Gender Inequity Index (United Nations Development Program, 2017), a measure associated with both acceptance and occurrence of IPV within and between country analyses (Redding, Ruiz-Cantero, Fernández-Sáez, & Guijarro-Garvi, 2017; Tran, Nguyen, & Fisher, 2016; Willie & Kershaw, 2019). In a study with 592 young women in post-conflict Liberia, attitudes accepting physical IPV were prevalent and associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing IPV (Callands, Sipsma, Betancourt, & Hansen, 2013). Thus, attitudes justifying violence against women may also mediate the relationship between exposure to traumatic war/community-violence-related events and IPV experience among women.

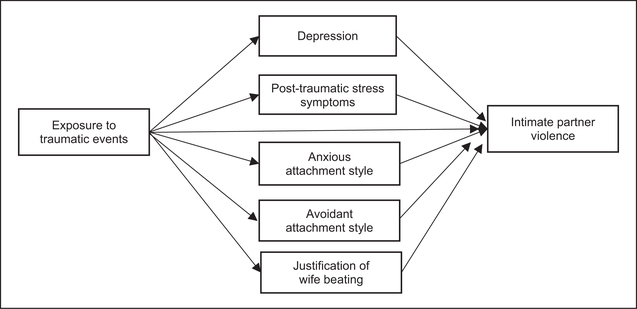

Although there is increased recognition and concern about elevated incidence of IPV in post-conflict settings, more research is needed to understand how exposure to traumatic events in this context increases women’s risk of IPV. We examined potential mediators between lifetime exposure to traumatic events (i.e., war-related trauma, community violence) with recent experiences of IPV among young, pregnant women in Monrovia, Liberia. We focused on this population because young women between the ages of 15 and 24 are more likely to experience IPV than any other age group in Liberia (Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services et al., 2008), and pregnancy represents a time of increased risk for both mental health outcomes and IPV in vulnerable populations (Osok, Kigamwa, Huang, Grote, & Kumar, 2018; Rees et al., 2016; Taillieu & Brownridge, 2010). Moreover, experiencing IPV during pregnancy is of significant public health concern as it increases the risk for infant mortality and morbidity and negative mental health outcomes in mothers (Alhusen, Ray, Sharps, & Bullock, 2015; Mahenge, Likindikoki, Stockl, & Mbwambo, 2013; Rurangirwa, Mogren, Ntaganira, Govender, & Krantz, 2018). Based on the literature cited above, we hypothesize mental health outcomes (depression, PTSD), insecure attachment style (anxious and avoidant attachment), and attitudes indicative of norms of violence (attitudes justifying wife beating) will be independently associated with exposure to traumatic events (related to war, community violence) and IPV and may mediate the trauma-IPV relationship. These hypotheses are displayed in the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the hypothesized parallel multiple mediation model of the relationship between experience of war-related trauma and intimate partner violence.

Method

This cross-sectional study included a researcher-administered survey with 183 pregnant women recruited from a community health clinic in Monrovia, the capital city of Liberia. The data used for this analysis were part of a larger study focused on sexual and mental health of young pregnant women. Clinicians referred pregnant women receiving prenatal care from this clinic to a research assistant to learn about the study. The research assistant then conducted a ten minute assessment of eligibility administered through computer-assistant personal interviewing (CAPI) software due to low literacy in the population. Eligibility criteria included (a) receiving or had received prenatal services from the local community health clinic, (b) 18 to 30 years old, (c) residing in Monrovia, (d) between 13 and 24 weeks of gestational age, (e) and no pregnancy-related medical problems. The research assistant obtained written informed consent from women who were eligible and interested in participating, and then administered a questionnaire that lasted 90 minutes in a private setting in the community health clinic using CAPI software. In total, 195 women completed the questionnaire. However, 12 women did not answer any of the IPV items; therefore, only 183 women were included in this analysis. Participants received $6 and a meal to compensate them for their time and travel. All study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards in the United States and Liberia.

Measures

The study measures were culturally adapted through a four-stage process (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, & Ferraz, 2000): (a) we began with the initial translation of the measures from English to Liberian English (the primary language/dialect of our sample) by local community members; (b) next, we worked with key informants to ensure key concepts in the materials were relevant to the Liberian context and cultural norms; (c) measures were then back-translated by key informants to ensure that the meaning and context of material was maintained through translation; and, finally, (d) an expert panel of Liberian key informants, fluent in English and Liberian English and experienced in behavioral research, reviewed and came to consensus on semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence.

Of the sociodemographics measured, we included the following as potential covariates in our analysis: age (continuous), education (dichotomized for analysis as primary grade or less, and secondary or greater), in a relationship (yes/no), any living children (yes/no), employed (yes/no).

Our primary independent variable, exposure to traumatic events, was measured with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; Mollica et al., 1992). This scale was designed to assess torture, trauma, or trauma-related events as they relate to mass violence or conflict. The scale was adapted for the Liberian context in partnership with the aforementioned expert panel of Liberian key informants. Respondents indicated whether they had experienced particular traumatic events (yes/no) assessed through 39 items (e.g., have you seen people fighting war, been taken from your family by force, seen the killings of people), which were summed for a total score (Cronbach’s α in present sample = .90).

Of the hypothesized mediators for this analysis, we measured two mental health factors (depression, PTSD), two relationship factors (anxious and avoidant attachment style), and one measure of norms of violence (attitudes justifying wife beating). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001), a nine-item scale designed for clinicians to diagnose depression and monitor treatment response. The items assess the frequency and severity in which participants experience different depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. We adapted the scale responses from a 4- to a 3-point scale for our study population: severity: 0 = not at all difficult, 1 = sometimes difficult, 2 = too difficult; frequency: 0 = not at all, 1 = some days, 2 = every day (Cronbach’s α in present sample = .70). PTSD symptoms were measured with the 17-item PTSD Checklist (PCL-C), for which participants rated the severity of PTSD symptoms over the prior 30 days (Ruggiero, Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1994). We amended the response scale from 5 to 4 points: 0 = not at all, 1 = sometimes, 2 = most of the time, 3 = all of the time (Cronbach’s α in present sample = .76).

Two subscales of the 34-item Experiences in Close Relationships–Revised (ECR-R) Questionnaire were used to measure anxious attachment style and avoidant attachment style (Fraley, 2002; Fraley & Shaver, 2000; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). Anxious attachment items measure the participants’ fear of rejection and abandonment in intimate relationships (e.g., I worry that my boyfriend doesn’t love me/won’t stay with me). High scores on avoidant attachment items represent individuals who are uncomfortable with intimacy and seek independence (e.g., I prefer not to be too close to boyfriends/I find it hard to allow myself to depend on boyfriends). The original scale used a 7-point Likert-type scale, which was adapted to a 4-point Likert-type scale for our study population: 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = most of the time, 3 = always (Cronbach’s α in present sample for anxious attachment = .91 and avoidant attachment = .93).

A scale developed by Briere (1997) and used in the Liberian Demographic and Health Survey (Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services et al., 2008) was used to measure attitudes justifying wife beating in five different situations: (a) going out without telling husband, (b) not taking good care of children, (c) arguing with husband, (d) denying husband in bed, and (e) not cooking well. Responses were on a 4-point scale: 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = most of the time, 3 = always. The total scale was summed for analysis (Cronbach’s α in present sample = .74).

The study outcome, IPV, was measured with the Severity of Violence Against Women Scale (SVAW; Marshall, 1992). A total of 43 items of the original 49-item scale were included to evaluate the seriousness of violence experienced by women by an intimate partner in the prior 12 months, which included a range of emotional (e.g., threatened physical violence, spoiling something you own), physical (e.g., being slapped, hit, punched, pushed, or experienced other use of bodily force), and sexual abuse experiences (e.g., forced sex). Women were asked how often in the prior year they experienced these acts. Response options were on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = never to 3 = 3 or more times. The total scale was summed for analysis (Cronbach’s α in present sample = .91). In addition to the SVAW, used as our outcome measure, respondents were also asked in single items about their experience of physical, sexual, or emotional IPV in their lifetime, as well as in the prior 2 months (while pregnant). We present these results within participant characteristics to add more description to women’s experience with IPV.

Data Analysis Approach

In SPSS version 24, we first tested bivariate correlations between all variables to determine if all hypothesized mediators should remain in the final model (i.e., were independently associated with both trauma and IPV) and to identify covariates to control for in the final model. We tested age, education, relationship status, any living children, and employment as potential covariates, as we expected them to associate with our model variables. Those that remained statistically significant (p < .05) in their relationship to exposure to traumatic events or IPV would be retained in the final model. We then tested a parallel multiple mediation model using the PROCESS method for SPSS version 24 developed by Hayes (2013) to examine mediators of the relationship between exposure to traumatic events and IPV. We chose to use a parallel multiple mediation model over simple mediation approach, as it allows for comparison of the sizes of the indirect effects through different mediators. Our hypothesized conceptual model (see Figure 1) included the independent variable (exposure to traumatic events), the dependent variable (IPV), and five proposed mediators (depression, PTSD, anxious attachment, avoidant attachment, wife-beating attitudes).

Our mediation test required the assessment of multiple pathways. The a path included the assessment of the effect of the independent variable (traumatic events) on the mediators. The b path consisted of analyzing the effect of each mediator variable on the dependent variable (IPV), controlling for the independent variable and all mediator variables. For the c′ path, we regressed traumatic events and all mediators onto IPV to assess the indirect effect of exposure to traumatic events on IPV through our mediators. We used the bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping method to test confidence intervals (CIs), which does not assume normality of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect and offers relatively greater power and better Type I error rates compared with other mediation approaches (Hayes, 2013). Following Preacher and Hayes (2008), 95% CIs were used for the indirect effects, and 10,000 bootstrapping samples were generated.

Results

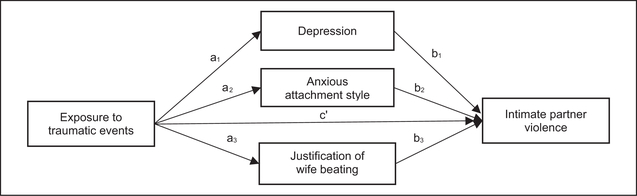

Table 1 displays sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Descriptive data and bivariate correlations of the variables included in the multiple mediation model are displayed in Table 2. PTSD was not independently associated with IPV, and anxious attachment was not associated with trauma or IPV. Therefore, we excluded both variables from our final model. The final tested model is displayed in Figure 2, which controlled for age; all other hypothesized covariates (education, relationship status, any living children, employment) were trimmed from the model (p < .10).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Liberia 2016 (N = 183).

| n (%) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 22.78 (3.68) | 18–30 |

| Education | ||

| No education | 15 (8.20%) | |

| Primary (Grade 1–6) | 52 (28.42%) | |

| Secondary (Grade 7–9) | 46 (25.14% | |

| High school (Grade 10–12) | 63 (34.42%) | |

| Some college or vocational training | 7 (3.82%) | |

| Relationship status | ||

| Not in a relationship | 15 (8.20%) | |

| In a relationship | 168 (91.80%) | |

| Any living children | ||

| No | 99 (50.8%) | |

| Yes | 96 (49.20%) | |

| Employed | ||

| No | 91 (49.70%) | |

| Yes | 92 (50.30%) | |

| Any lifetime experience of IPV | ||

| No | 100 (54.60%) | |

| Yes | 83 (45.40%) | |

| Any recent experience of IPV (prior 2 months) | ||

| No | 124 (67.80%) | |

| Yes | 59 (32.30%) |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence, inclusive of emotional, physical, and sexual intimate partner violence.

Table 2.

Descriptive Information and Bivariate Correlations Between the Assessed Variables, Liberia 2016 (N = 183).

| Severity of IPV | T rauma Exposure | Depression | PTSD | Anxious Attachment | Avoidant Attachment | Justification of Wife Beating | M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of 1PV | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3.68 | 5.65 | 0–19 |

| Trauma exposure | .40** | — | — | — | — | — | — | 6.60 | 3.69 | 1–21 |

| Depression | .23** | .39** | — | — | — | — | — | 4.22 | 2.41 | 0–10 |

| PTSD | .12 | 49** | .46** | — | — | — | — | 5.40 | 4.14 | 0–22 |

| Anxious attachment | .31 ** | 22** | .17* | .19* | — | — | — | 9.94 | 6.88 | 2–35 |

| Avoidant attachment | .06 | .1 1 | .08 | 21 ** | .34** | — | — | 24.22 | 8.16 | 0–47 |

| Justification of wife beating | .23** | .18* | .1 1 | .18* | .08 | −.04 | — | 0.63 | 1.16 | 0–6 |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

The tested parallel multiple mediation model of the relationship between exposure to traumatic events and experience of intimate partner violence.

Multiple Mediator Model of the Relationship Between Exposure to Traumatic Events and IPV

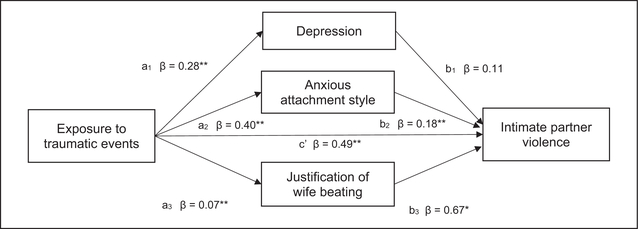

Figure 3 illustrates the findings of our multiple mediator model’s direct effects (indirect effects are reported in Table 3). The three proposed mediators were first regressed onto traumatic events (a path). We found greater exposure to traumatic events was associated with greater depression (β = .28; 95% CI = [0.18, 0.37]; p < .001), greater anxious attachment style (β = .40; 95% CI = [0.12, 0.67]; p = .005), and greater justification of wife beating (β = .07; 95% CI = [0.03, 0.15]; p = .002).

Figure 3.

Multiple mediation model of relationships between experience of wartime trauma, multiple mediators, and experience of intimate partner violence.

Note. Age is controlled for in this model.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Table 3.

Mediation of the Effect of Exposure to Traumatic Events on Experience of Intimate Partner Violence Through Depression, Anxious Attachment Style, and Wife-Beating Attitudes, Liberia 2016 (N = 183).

| Bootstrapping | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product of Coefficients |

Bias-Corrected and Accelerated CI |

|||

| Point Estimate | SE | 95% Lower | 95% Upper | |

| Depression | 0.029 | 0.047 | −0.067 | 0.117 |

| Anxious attachment | 0.073 | 0.033 | 0.026 | 0.161 |

| Justification of wife beating | 0.050 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.159 |

| Total | 0.152 | 0.070 | 0.031 | 0.3141 |

Note. Age is controlled for in this model. SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval.

In our assessment of all hypothesized mediators with IPV, which controlled for all mediators and exposure to traumatic events, anxious attachment style was associated with greater severity of IPV (β = .18; 95% CI = [0.07, 0.29]; p = .001), as were greater scores on the wife-beating attitudes scale (β = .67; 95% CI = [0.15, 1.33]; p = .04). Depression was not associated with IPV at a statistically significant level (β = .11; 95% CI = [–0.23, 0.44]; p = .52).

Finally, for the c′ path, we regressed traumatic events and all mediators onto IPV to assess the indirect effect of exposure to traumatic events on IPV through our mediators. The results show a positive and significant association (β = .15, 95% CI = [0.26, 0.73], p < .001).

Table 3 includes the results of the multiple mediation analysis. Statistical significance of mediators is indicated by 95% CIs that do not contain zero. The results show that taken together, depression, anxious attachment style, and justification of wife beating significantly mediated the relationship between exposure to traumatic events and experience of IPV (see total in Table 3). However, as individual mediators, only anxious attachment style and justification of wife beating were found to mediate this relationship.

Discussion

Liberia’s history of multiple devastating events over the prior three decades has left several generations of the population exposed to significant trauma. All women in our sample of pregnant young women in Monrovia, Liberia experienced one or more traumatic events, primarily related to war and community violence in their lifetime, even though most were born toward the end or after Liberia’s civil war. The results of the study show that greater exposure to traumatic events is associated with greater likelihood and severity of IPV victimization among young pregnant women. These findings support a growing body of work demonstrating elevated incidence of IPV in post-conflict settings and among individuals who have experienced trauma related to war and community violence (Annan & Brier, 2010; Clark et al., 2010; Falb et al., 2013; J. Gupta et al., 2014; J. Gupta et al., 2012; Jewkes et al., 2018; Kelly et al., 2018; Saile et al., 2013; Vinck & Pham, 2013). Importantly, this study adds to our understanding of pathways that potentially explain the trauma-IPV relationship using mediation analysis. We found greater exposure to traumatic events was independently associated with greater rates of depression, PTSD, anxious attachment, and attitudes justifying wife beating, all of which, apart from PTSD, were independently associated with experience of IPV among young pregnant women. However, only anxious attachment and attitudes justifying wife beating were identified as statistically significant individual mediators of the trauma-IPV relationship.

This study supports our hypothesis that greater exposure to traumatic events in a post-conflict setting may influence the development of insecure attachment, which in turn increases women’s risk of IPV victimization. Experiencing war and the long-term consequences of such events on communities (e.g., poverty, family separation, continued community violence) can influence a child’s sense of attachment through a loss of security, predictability, family unit stability and structure, and supportive community networks and institutions (Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, & Brennan, 2013). For example, Liberia’s civil war resulted in an estimated 340,000 orphaned children (Collins, 2015; Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services, 2008). Research has demonstrated childhood trauma, including separation from parents, is predictive of insecure attachment in adults (Bryant et al., 2017). Qualitative research in post-conflict Liberia reported adolescents who experienced disruptions in early relationships suffered from disconnection from their families and communities, in addition to other negative psychosocial and emotional health consequences (Levey et al., 2017).

This finding also contributes to our understanding of the relationship between attachment style and IPV. Insecure attachment styles have been linked to an increased likelihood of IPV victimization and perpetration in developed settings (Doumas et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2017; McClellan & Killeen, 2000; Sandberg et al., 2019). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis examining this relationship found a considerable number of studies reporting no association, and very few studies with this aim conducted in low-income countries (Velotti et al., 2018). In our study, anxious attachment was identified as a mediator between trauma exposure and IPV. However, avoidant attachment was not independently associated with IPV. Future research should continue to explore the intergenerational effects that war and other forms of community trauma can have on attachment and interpersonal relationships to better understand elevated IPV incidence in post-conflict settings.

We also found support for our hypothesis that young pregnant women who have been exposed to trauma would be more likely to endorse violence against women. As anticipated, this in part explained the relationship between trauma exposure and IPV, adding to other studies demonstrating acceptance of violence against women is associated with victimization (e.g., Allen & Devitt, 2012; Callands et al., 2013). This relationship is likely bidirectional, with IPV exposure influencing women’s learned acceptance of this behavior. However, individual attitudes endorsing violence against women are also an indicator of broader community norms that endorse gender inequitable attitudes and a culture of violence more broadly. In conflict-affected settings where gender-based violence was used as a war tactic, community violence can have lasting effects on broader acceptance of violence against women. Thus, young pregnant women who have experienced greater traumatic events in our sample may be connected to networks with more acceptance of violence against women and gender inequity, and, in turn, more IPV perpetration. Kelly et al. (2018) demonstrated Liberian women who lived in a conflict fatality-affected district 5 years post-conflict were at a 50% increased risk of IPV exposure. Those in districts with 4 to 5 cumulative years of conflict were almost 90% more likely to experience IPV than those living in a district with no conflict (Kelly et al., 2018). Our study only assessed individual-level attitudes as a proxy for community norms. More research is needed that takes a multilevel approach to understanding the effects of broader community norms resulting from community violence on IPV incidence.

In addition to contributing to our theoretical understanding of mechanisms between trauma exposure and IPV, this study has important implications for intervention. Approximately 45% of young pregnant women in our sample reported experiencing any emotional, physical, or sexual IPV in their lifetime, and 32% had experienced at least one of these forms of abuse in the 2 months prior to our interview, while pregnant. While alarming, these rates are consistent with other estimates in Liberia (Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services et al., 2008; Stark & Ager, 2011), reinforcing the need for violence reduction interventions for young women in Liberia and highlighting pregnancy as a particularly important time frame for intervention. The WHO recommends clinical inquiry in antenatal care for women with conditions that could be caused or exacerbated by IPV (WHO, 2018). Universal screening for IPV paired with ongoing support services is recommended for women of reproductive age including pregnant/postpartum women in developed countries (Curry et al., 2018). However, even in resource-rich settings, implementation is low (Chisholm, Bullock, & Ferguson, 2017). Thus, research is needed in settings with low-capacity health systems such as Liberia to increase the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating IPV interventions into antenatal care, and to reach women not linked to services (WHO, 2011).

Our findings also point to the potential for trauma-informed counseling approaches for violence reduction in low-income post-conflict settings. Efficacy trials on trauma-informed IPV counseling show promise for IPV prevention and reduction but are largely conducted in developed settings (e.g., Creech, Benzer, Ebalu, Murphy, & Taft, 2018; Decker et al., 2017; Machtinger, Cuca, Khanna, Rose, & Kimberg, 2015; WHO, 2013), pointing to the need for research that adapts and tests trauma-informed IPV interventions for West African settings. Our study also demonstrates the need for IPV interventions that dually address mental health conditions. Although the mental health outcomes assessed in this study were not identified as mediators between trauma and IPV, both trauma and IPV were associated with depression, and trauma was associated with PTSD. This finding is consistent with syndemics theory (Singer, 2009; Singer & Clair, 2003) and research, which demonstrates a cumulative effect of early life trauma experience on multiple mental health conditions in adulthood that require integrated public health approaches (Singer, Bulled, Ostrach, & Mendenhall, 2017). We previously found support for a cumulative effect of exposure to trauma and other mental health and psychosocial conditions on engagement in transactional sex among this sample of young pregnant women in Liberia (see Sileo, Kershaw, & Callands, 2019).

Finally, our finding that attitudes toward wife beating contribute to women’s risk for IPV suggest the need for multilevel gender-transformative interventions, which broadly aim to reconfigure harmful masculine norms to improve men’s and women’s health and to shift beliefs, behaviors, and relationships toward gender equity (Dworkin, Fleming, & Colvin, 2015; Dworkin, Hatcher, Colvin, & Peacock, 2013; G. R. Gupta, 2000). Systematic reviews of gender-transformative interventions report that programs that engage individuals or groups of men and women to adopt gender-equitable attitudes have been successful at reducing IPV incidence and gender-inequitable attitudes in African settings (Casey, Carlson, Two Bulls, & Yager, 2018; Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, & Lippman, 2013). Individual-level interventions that combine community-or structural-level components may be even more effective (Dworkin et al., 2015; Dworkin, Treves-Kagan, & Lippman, 2013). Examples include campaigns to raise community awareness about violence against women (Hossain et al., 2014), and those that address young women’s economic dependence on men through conditional cash transfers (Kilburn et al., 2018). The scale up of these approaches in tandem with policy-level change (e.g., development and enforcement of laws to investigate and prosecute perpetrators of violence using due process) could together address norms that drive the IPV epidemic in Liberia and significantly reduce the high burden of morbidity, mortality, and economic costs associated with IPV (WHO, 2017). However, achieving this level of change will require concerted efforts and commitment across governmental and nongovernmental institutions to prioritize the end of IPV and gender-based violence more broadly.

Limitations

The generalizability of our findings is limited by our purposive sampling of women attending community health clinics in the capital city of Liberia. The relatively small sample size may have limited our ability to detect all existing associations. While our mediation analysis approach is an important contribution to the literature on pathways between trauma exposure and IPV, the cross-sectional and self-reported nature of the data prohibits conclusions about causality and the directional nature of the relationships examined. Only one other study that we are aware of has examined these relationships in a conflict-affected setting with path analysis, which was also cross-sectional (Jewkes et al., 2018). Future longitudinal research is needed to further elucidate these and other pathways, which can establish temporality and determine the direction of the correlations observed in our cross-sectional study, which are likely bidirectional. For example, depression may increase risk of experiencing IPV, but may also be a consequence of IPV. In addition, the measures used were adapted for this population to ensure cultural equivalence. However, adaptations may limit the ability to compare our findings with studies that have used the original scales. Despite these limitations, these data shed light on the intergenerational and long-term societal effects of trauma on IPV and contribute preliminary data to warrant more rigorous investigations on mental health, interpersonal, and normative pathways between exposure to trauma on experience of IPV among Liberian youth.

Conclusion

In this study of pregnant young women in Liberia, we found high rates of IPV, including experience of IPV during pregnancy. With dire consequences of IPV during pregnancy on both mother and infants, this study reinforces pregnancy as an important window for both violence and mental health screening and intervention for this population. In addition, this study adds to a growing literature that demonstrates cumulative exposure to traumatic events in post-conflict settings is associated with an increased risk of experiencing IPV and begins to fill a gap in the literature on potential pathways that explain this relationship. Anxious attachment style and attitudes justifying wife beating were identified as mediators between the trauma-IPV relationship. These findings not only contribute to our theoretical understanding of this relationship but point to the need for trauma-informed counseling and multilevel gender-transformative public health approaches to address violence against women.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project was supported by research funds from the National Institutes of Health and Fogarty International Center 5K01TW009660–03, Principal Investigator (PI): Tamora A. Callands. Katelyn M. Sileo was supported by a T32 Postdoctoral Fellowship Award on HIV Prevention from the National Institute of Mental Health NIH/NIMH 5T32MH020031–18, PI: Trace S. Kershaw.

Biography

Katelyn M. Sileo is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Kinesiology, Health, and Nutrition at the University of Texas at San Antonio. Her research focuses on the role of gender norms in health outcomes and the development of behavioral and health system interventions to improve HIV and reproductive health care engagement in global settings.

Trace S. Kershaw is Department Chair and professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences in the Yale School of Public Health. His research focuses on social and structural determinants of health among adolescents and emerging adults, with a focus on behavioral intervention development and the application of technologic methods to understand how social and geographic context influence health.

Shantesica Gilliam is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of Health Promotion and Behavior at the University of Georgia. Shantesica’s research focuses on the developing sexual health and HIV prevention strategies focused on reducing HIV stigma, racial and gender health disparities, and community violence and gender-based violence among racial and sexual minorities.

Erica Taylor is a second-year doctoral student in the Department of Health Promotion and Behavior at the University of Georgia. Her research focuses on the intersectionality of mental health and prenatal care in minority women living in low-resource areas, examining mental health implications of HIV diagnosis in pregnant women, and to explore stress reduction interventions guided by motivational interviewing in pregnant women.

Apoorva Kommajosula earned her BSc in Health Promotion at the University of Georgia and is an MPH candidate at Emory University. Her research interests in global health focus on analyzing barriers to health services in low- and middle-income countries and developing community-based interventions to promote health as well as health education in low-resource settings.

Tamora A. Callands is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Promotion and Behavior at the University of Georgia. Her research focuses on developing interventions to promote mental and sexual health among pregnant women in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), exploring facilitators and barriers to violence prevention in LMICs, and building social support for pregnant women in rural communities via technology.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alhusen JL, Ray E, Sharps P, & Bullock L (2015). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Journal of Women’s Health, 24, 100–106. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, & Devitt C (2012). Intimate partner violence and belief systems in Liberia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 3514–3531. doi: 10.1177/0886260512445382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annan J, Blattman C, Mazurana D, & Carlson K (2008). Women and girls at war: “Wives”, mothers, and fighters in the Lord’s Resistance Army. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.212.3544&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Annan J, & Brier M (2010). The risk of return: Intimate partner violence in Northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, & Ferraz MB (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25, 3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berckmoes LH, De Jong JTVM, & Reis R (2017). Intergenerational transmission of violence and resilience in conflict-affected Burundi: A qualitative study of why some children thrive despite duress. Global Mental Health, 4, e26–e26. doi: 10.1017/gmh.2017.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, McBain R, Newnham EA, & Brennan RT (2013). Trajectories of internalizing problems in war-affected Sierra Leonean youth: Examining conflict and postconflict factors. Child Development, 84, 455–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01861.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, McBain RK, Newnham EA, & Brennan RT (2015). The intergenerational impact of war: Longitudinal relationships between caregiver and child mental health in postconflict Sierra Leone. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 1101–1107. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J (1997). Predicting self-reported likelihood of battering: Attitudes and childhood experiences. Journal of Research in Personality, 21, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Creamer M, O’Donnell M, Forbes D, Felmingham KL, Silove D, & Nickerson A (2017). Separation from parents during childhood trauma predicts adult attachment security and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 47, 2028–2035. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callands TA, Sipsma HL, Betancourt TS, & Hansen NB (2013). Experiences and acceptance of intimate partner violence: Associations with sexually transmitted infection symptoms and ability to negotiate sexual safety among young Liberian women. Culture Health and Sexuality, 15, 680–694. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.779030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey E, Carlson J, Two Bulls S, & Yager A (2018). Gender transformative approaches to engaging men in gender-based violence prevention: A review and conceptual model. Trauma Violence Abuse, 19, 231–246. doi: 10.1177/1524838016650191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani C (2010). War in the home: A review of the relationship between family violence and war trauma. Verhaltenstherapie, 20(1), 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

- Chisholm CA, Bullock L, & Ferguson JEJ 2nd. (2017). Intimate partner violence and pregnancy: Screening and intervention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217, 145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CJ, Everson-Rose SA, Suglia SF, Btoush R, Alonso A, & Haj-Yahia MM (2010). Association between exposure to political violence and intimate-partner violence in the occupied Palestinian territory: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet, 375, 310–316. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61827-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn S, & Kutalek R (2016). Historical parallels, Ebola virus disease and cholera: Understanding community distrust and social violence with epidemics. PLoS Currents, 8. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.aa1f2b60e8d43939b43fb-d93e1a63a94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins P (2015). What happened to Liberia’s Ebola orphans? The new humanitarian. Retrieved from http://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2015/10/07/what-happened-liberia-s-ebola-orphans

- Cousins S (2018). Violence and community mistrust hamper Ebola response. Lancet Infectious Disease, 18, 1314–1315. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30658-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creech SK, Benzer JK, Ebalu T, Murphy CM, & Taft CT (2018). National implementation of a trauma-informed intervention for intimate partner violence in the Department of Veterans Affairs: First year outcomes. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 582–582. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3401-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombach A, & Bambonyé M (2015). Intergenerational violence in Burundi: Experienced childhood maltreatment increases the risk of abusive child rearing and intimate partner violence. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 26995. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, … Wong, J. B. (2018). Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. Journal of American Medical Association, 320, 1678–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard NT, Todd BK, Daniel SI, & Montgomery E (2016). The transmission of trauma in refugee families: Associations between intra-family trauma communication style, children’s attachment security and psychosocial adjustment. Attachment & Human Development, 18, 69–89. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1113305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Tomko C, Wingo E, Sawyer A, Peitzmeier S, Glass N, & Sherman SG (2017). A brief, trauma-informed intervention increases safety behavior and reduces HIV risk for drug-involved women who trade sex. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 75. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4624-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devakumar D, Birch M, Osrin D, Sondorp E, & Wells JCK (2014). The intergenerational effects of war on the health of children. BMC Medicine, 12, 57–57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, Mak J, Falder G, Graham K, … Heise L (2014). Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 109, 379–391. doi: 10.1111/add.12393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, … Watts CH (2013). Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Pearson CL, Elgin JE, & McKinley LL (2008). Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: The “mispairing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23, 616–634. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Fleming PJ, & Colvin CJ (2015). The promises and limitations of gender-transformative health programming with men: Critical reflections from the field. Culture Health Sexuality, 17, 128–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Hatcher AM, Colvin C, & Peacock D (2013). Impact of a gender-transformative HIV and antiviolence program on gender ideologies and masculinities in two rural, South African communities. Men and Masculinities, 16(2). doi: 10.1177/1097184X12469878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Treves-Kagan S, & Lippman SA (2013). Gender-transformative interventions to reduce HIV risks and violence with heterosexually-active men: A review of the global evidence. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 2845–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S (2006). The mask of Anarchy updated edition: The destruction of Liberia and the religious dimension of an African Civil War. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falb KL, McCormick MC, Hemenway D, Anfinson K, & Silverman JG (2013). Violence against refugee women along the Thai-Burma border. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics, 120, 279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC (2002). Attachment stability from infancy to adulthood: Meta-analysis and dynamic modeling of developmental mechanisms. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6, 123–151. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Owen MT, & Holland AS (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 817–838. doi: 10.1037/a0031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, & Shaver PR (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology, 4, 132–154. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, & Brennan KA (2000). An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Rockers PC, Saydee G, Macauley R, Varpilah ST, & Kruk ME (2010). Persistent psychopathology in the wake of civil war: Long-term post-traumatic stress disorder in Nimba County, Liberia. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1745–1751. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.179697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR (2000, July 9–14). Gender, sexuality, and HIV/AIDS: The what, the why, and the how. Paper presented at the XIII International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Falb KL, Carliner H, Hossain M, Kpebo D, & Annan J (2014). Associations between exposure to intimate partner violence, armed conflict, and probable PTSD among women in rural Cote d’Ivoire. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e96300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Reed E, Kelly J, Stein DJ, & Williams DR (2012). Men’s exposure to human rights violations and relations with perpetration of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(6), e2. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.112300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Abramsky T, Kone D, Bakayoko-Topolska M, … Watts C (2014). Working with men to prevent intimate partner violence in a conflict-affected setting: A pilot cluster randomized controlled trial in rural Côte d’Ivoire. BMC Public Health, 14, 339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Corboz J, & Gibbs A (2018). Trauma exposure and IPV experienced by Afghan women: Analysis of the baseline of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 13, e0201974. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K, Asher J, Rosborough S, Raja A, Panjabi R, Beadling C, & Lawry L (2008). Association of combatant status and sexual violence with health and mental health outcomes in postconflict Liberia. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300, 676–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JTD, Colantuoni E, Robinson C, & Decker MR (2018). From the battlefield to the bedroom: A multilevel analysis of the links between political conflict and intimate partner violence in Liberia. BMJ Global Health, 3(2), e000668. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, … Koenen KC (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(Suppl. 5), 1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburn KN, Pettifor A, Edwards JK, Selin A, Twine R, MacPhail C, … Kahn K (2018). Conditional cash transfers and the reduction in partner violence for young women: An investigation of causal pathways using evidence from a randomized experiment in South Africa (HPTN 068). Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21(Suppl. 1), 211. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinyanda E, Weiss HA, Mungherera M, Onyango-Mangen P, Ngabirano E, Kajungu R, … Patel V (2016). Intimate partner violence as seen in post-conflict eastern Uganda: Prevalence, risk factors and mental health consequences. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 16, 5. doi: 10.1186/s12914-016-0079-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkoyah DT, & Wreh F (2015). Ebola impact revealed: An assessment of the differing impact of the outbreak on women and men in Liberia. The Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection, UN Women, Oxfam, the Liberia WASH Consortium. Retrieved from https://www-cdn.oxfam.org/s3fs-public/file_attachments/rr-ebola-impact-women-men-liberia-010715-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey EJ, Oppenheim CE, Lange BC, Plasky NS, Harris BL, Lekpeh GG, … Borba CP (2017). A qualitative analysis of parental loss and family separation among youth in post-conflict Liberia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 12(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2016.1262978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BS (2002). Health and peace. Croatian Medical Journal, 43, 114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JB, Sullivan TP, Angley M, Callands T, Divney AA, Magriples U, … Kershaw TS (2017). Psychological and relational correlates of intimate partner violence profiles among pregnant adolescent couples. Aggressive Behavior, 43, 26–36. doi: 10.1002/ab.21659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Marshall CM, Rees HC, Nunez A, Ezeanolue EE, & Ehiri JE (2014). Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 18845. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.18845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services. (2008). 2008 national population and housing census. Author. Retrieved from http://www.lisgis.net/page_info.php?7d5f44532cbfc489b8db9e12e44eb820=MzQy [Google Scholar]

- Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, National AIDS Control Program, & Macro International Inc. (2008). Liberia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Monrovia: Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services & Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- Liebling-Kalifani H, Mwaka V, Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Were-Oguttu J, Kinyanda E, Kwekwe D, … Danuweli C (2011). Women war survivors of the 1989–2003 conflict in Liberia: The impact of sexual and gender-based violence. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 12(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Machtinger EL, Cuca YP, Khanna N, Rose CD, & Kimberg LS (2015). From treatment to healing: The promise of trauma-informed primary care. Women’s Health Issues, 25, 193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenge B, Likindikoki S, Stockl H, & Mbwambo J (2013). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and associated mental health symptoms among pregnant women in Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BJOG, 120, 940–946. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L (1992). Development of the severity of violence against women scales. Journal of Family Violence, 7, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- McClellan AC, & Killeen MR (2000). Attachment theory and violence toward women by male intimate partners. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32, 353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, & Lavelle J (1992). The Harvard trauma questionnaire. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180, 111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mootz JJ, Stabb SD, & Mollen D (2017). Gender-based violence and armed conflict: A community-informed socioecological conceptual model from Northeastern Uganda. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41, 368–388. doi: 10.1177/0361684317705086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina N, Schnyder U, Schick M, Nickerson A, & Bryant RA (2016). Attachment style and interpersonal trauma in refugees. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 1161–1168. doi: 10.1177/0004867416631432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Transitional Government of Liberia. (2004). Joint needs assessment. Monrovia: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Osok J, Kigamwa P, Huang K-Y, Grote N, & Kumar M (2018). Adversities and mental health needs of pregnant adolescents in Kenya: Identifying interpersonal, practical, and cultural barriers to care. BMC Women’s Health, 18(1), 96–96. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0581-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallitto CC, Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Heise L, Ellsberg M, & Watts C (2013). Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 120(1), 3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Grimon M-P, & Eggerman M (2014). Caregiver–child mental health: A prospective study in conflict and refugee settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 313–327. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabelo I, Lee V, Fallah MP, Massaquoi M, Evlampidou I, Crestani R, … Severy N (2016). Psychological distress among Ebola survivors discharged from an Ebola Treatment Unit in Monrovia, Liberia—A qualitative study. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, Article 142. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redding EM, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Fernández-Sáez J, & Guijarro-Garvi M (2017). Gender inequality and violence against women in Spain, 2006–2014: Towards a civilized society. Gaceta Sanitaria, 31(2), 82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees SJ, Tol W, Mohsin M, Tay AK, Tam N, dos Reis N, … Silove DM (2016). A high-risk group of pregnant women with elevated levels of conflict-related trauma, intimate partner violence, symptoms of depression and other forms of mental distress in post-conflict Timor-Leste. Translational Psychiatry, 6, e725. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reingle JM, Jennings WG, Connell NM, Businelle MS, & Chartier K (2014). On the pervasiveness of event-specific alcohol use, general substance use, and mental health problems as risk factors for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 2951–2970. doi: 10.1177/0886260514527172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockers PC, Kruk ME, Saydee G, Varpilah ST, & Galea S (2010). Village characteristics associated with posttraumatic stress symptoms in postconflict Liberia. Epidemiology, 21, 454–458. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181df5fae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein BL, Lu LZN, MacFarlane M, & Stark L (2017). Predictors of interpersonal violence in the household in humanitarian settings: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1524838017738724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Ben KD, Scotti JR, & Rabalais AE (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rurangirwa AA, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Govender K, & Krantz G (2018). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy in relation to non-psychotic mental health disorders in Rwanda: A cross-sectional population-based study. BMJ Open, 8, e021807. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saile R, Neuner F, Ertl V, & Catani C (2013). Prevalence and predictors of partner violence against women in the aftermath of war: A survey among couples in northern Uganda. Social Science and Medicine, 86, 17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg DA, Valdez CE, Engle JL, & Menghrajani E (2019). Attachment anxiety as a risk factor for subsequent intimate partner violence victimization: A 6-month prospective study among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 1410–1427. doi: 10.1177/0886260516651314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN (2008). The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28, 266–271. doi: 10.1080/01443610802042415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtle PM, De Clerck V, & Plummer V (2017). Experiences of Ebola survivors: Causes of distress and sources of resilience. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 32, 234–239. doi: 10.1017/s1049023X17000073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sileo KM, Kershaw TS, & Callands TA (2019). A syndemic of psychosocial and mental health problems in Liberia: Examining the link to transactional sex among young pregnant women. Global Public Health, 14(10), 1442–1453. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1607523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M (2009). Introduction to syndemics: A critical systems approach to public and community health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, & Mendenhall E (2017). Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. The Lancet, 4, 941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, & Clair S (2003). Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 17, 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark L, & Ager A (2011). A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12, 127134. doi: 10.1177/1524838011404252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, & Tritt D (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(1), 65–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taillieu TL, & Brownridge DA (2010). Violence against pregnant women: Prevalence, patterns, risk factors, theories, and directions for future research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15, 14–35. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran TD, Nguyen H, & Fisher J (2016). Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women among women and men in 39 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE, 11, e0167438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Program. (2017). Human development reports: Table 5: Gender Inequality Index. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/GII

- Usta J, Farver JA, & Zein L (2008). Women, war, and violence: Surviving the experience. Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 793–804. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, Jambai M, Koroma AS, Muana AT, … Nellums LB (2016). Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community and international levels. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(3), 210–214. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.158543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velotti P, Beomonte Zobel S, Rogier G, & Tambelli R (2018). Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(1166). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P, & Pham PN (2013). Association of exposure to intimate-partner physical violence and potentially traumatic war-related events with mental health in Liberia. Social Science and Medicine, 77, 41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1994). PTSD Checklist–Civilian version. Boston, MA: National Center for PTSD, Behavioral Science Division. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Kozakowski SS, & Chauhan P (2018). Does adult attachment style mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental and physical health outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie TC, & Kershaw TS (2019). An ecological analysis of gender inequality and intimate partner violence in the United States. Prevention Medicine, 118, 257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2011). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Information sheet. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Fact Sheet: Violence against women. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendation on clinical diagnosis of intimate partner violence in pregnancy. Retrieved from https://extranet.who.int/rhl/topics/preconception-pregnancy-childbirth-and-postpartum-care/antenatalcare/who-recommendation-clinical-diagnosis-intimate-partner-violence-pregnancy [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich AR, Stockl H, Murray J, Melendez-Torres GJ, Steinert JI, Glavin CEY, & Humphreys DK (2018). Risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence against women: Systematic review and meta-analyses of prospective-longitudinal studies. American Journal Public Health, 108(7), e1–e11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]