Abstract

crAssphages are a broad group of diverse bacteriophages in the order Caudovirales that have been found to be highly abundant in the human gastrointestinal tract. Despite their high prevalence, we have an incomplete understanding of how crAssphages shape and respond to ecological and evolutionary dynamics in the gut. Here, we report genomes of crAssphages from feces of one South African woman and three infants. Across the complete genome sequences of the South African crAssphages described here, we identify particularly elevated positive selection in RNA polymerase and phage tail protein encoding genes, contrasted against purifying selection, genome-wide. We further validate these findings against a crAssphage genome from previous studies. Together, our results suggest hotspots of selection within crAssphage RNA polymerase and phage tail protein encoding genes are potentially mediated by interactions between crAssphages and their bacterial partners.

Keywords: bacteriophage, crAssphage, South Africa, selection, tail protein

The human gut virome is dominated by bacteriophages (Dutilh et al., 2014; Minot et al., 2011; Reyes et al., 2010). In the last decade, a ~97kb circular DNA phage genome, commonly referred to as crAssphage (from cross assembly of 12 fecal metagenomes), was identified and found to be the most abundant virus in the human gut (Dutilh et al., 2014). crAssphage-like contigs and genomes have been de novo assembled from fecal samples from various regions of the world and across health and disease states, emphasizing their high prevalence among human enteric microbiota (Edwards et al., 2019). Morphologically, crAssphages appear similar to members of the family Podoviridae (Shkoporov et al., 2018; Yutin et al., 2018), yet sequence-based approaches suggest a novel family level grouping within the order Caudovirales (Yutin et al., 2018). Comparative genomic analyses of human-associated crAssphage taxa have partitioned them into four candidate subfamilies composed of ten putative genera (Guerin et al., 2018).

Despite the abundance of crAssphage-like contigs and genomes detected in human fecal microbiota, little is known about the lifestyle or selective pressures acting on crAssphage genomes. Based on analysis of CRISPR spacers and other genomic features, it was speculated that crAssphages prey upon members of Bacteroides (Dutilh et al., 2014). Intuitively, this fits well with the Bacteroidetes-dominated community profile of human gut microbiota. Recently, certain members of the crAssphage group (ΦcrAss001) have been shown to stably infect Bacteroides intestinalis and are able to maintain long-term persistence in vivo, though the mechanisms underlying this relationship are unknown (Shkoporov et al., 2018). Furthermore, after long-term (23 days) interaction experiments between Bacteroides phage, ΦcrAss001 (accession # MH675552), and B. intestinalis, approximately half of isolated B. intestinalis colonies demonstrated complete resistance to the phage, indicating rapid evolution of bacterial interaction factors (Shkoporov et al., 2018). However, it remains unclear how this relationship impacts selective pressures acting across the crAssphage genome.

Our knowledge of bacterial-phage coevolution in the human gut is largely unexplored (Minot et al., 2011; Scanlan, 2017). Antagonistic interactions between bacteria and phages are crucial determinants of genomic evolution for both partners, and several studies have described these trends across diverse systems and environments (Brockhurst et al., 2007; Gomez and Buckling, 2011; Martiny et al., 2014; Schwartz and Lindell, 2017). In the gut environment, Minot et al. (2013) described rapid nucleotide substitution rates (>10−5 per nucleotide per day) in the lytic phage family Microviridae. With the establishment of a bacterial host for crAssphage taxa, evolutionary studies of selection in these host cells are likely to reveal some of the genomic consequences of bacterial-phage relationships in the gut.

Stool (sample ID: M186D4) was collected from a 24-year-old woman living with HIV enrolled in the InFANT study (Tchakoute et al., 2018) at a periurban clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. The participant was six days postpartum, was living with HIV with a CD4 lymphocyte count of 265 cells/mm3, and had initiated antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy with tenofovir, emtricitabine and efavirenz. In addition to the adult sample, four samples were also collected from infants without HIV (samples IDs C0521BD4, C0521BW15, C0526BW15 and C0531BW4). One infant (C0521B) samples were obtained at two time points; 4 days and 15 weeks of age. The samples were transported on ice and stored at −80°C until nucleic acid extraction. After defrosting, approximately 0.5g of fecal samples were homogenized in 20ml SM buffer as previously described (Kraberger et al., 2018) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was filtered sequentially through 0.45μm and 0.2μm Minisart (Sartorius AG, Germany) syringe filters. Filtered supernatants were incubated with lysozyme and Turbo DNAse (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 37°C for 1 hour to degrade nucleic acids not enclosed in virus particles.

Viral nucleic acid was extracted from 200μl of the filtrate using the High Pure viral nucleic acid kit (Roche Diagnostics, USA) following the standard protocol. Circular viral DNA was amplified using rolling circle amplification (RCA) with Illustra TempliPhi 100 amplification kit (GE Healthcare, USA). The RCA products were used to prepare a 250 bp insert DNA library for each sample following the manufacturer’s standard protocol. Shotgun sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform using 150bp paired end chemistry at Novogene (Hong Kong), or on an Illumina Novaseq6000 platform at North West Genomics Center (Seattle, WA USA).

Raw sequencing reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014) and then de novo assembled using SPAdes v 3.11.1 (Nurk et al., 2017). All de novo assembled contigs of >500 nts were aligned and annotated using a BLASTx search (Altschul and Lipman, 1990) against NCBI’s viral RefSeq protein database. Annotations were only applied if the E-value of the top hit was ≤ 1e−5. Open reading frames (ORFs) were identified using Glimmer (Delcher et al., 1999; Kearse et al., 2012) and annotated using an in-house reference protein database compiled from NCBI’s GenBank resource.

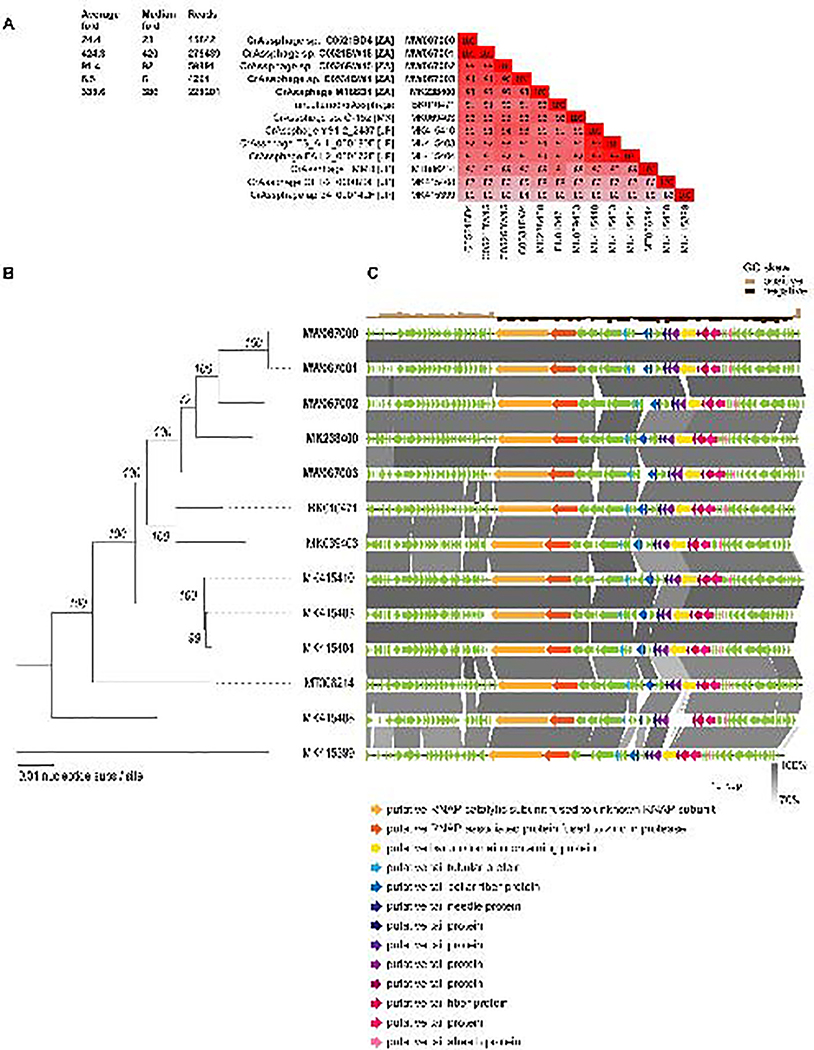

Sequence similarity searches of de novo assembled contigs resulted in the identification of various prokaryote and eukaryote-infecting viruses. In each of the fecal samples, we identified complete crAssphage genomes (Figure 1; 97,757 – 99,121 nts) that are most closely related to uncultured crAssphage (GenBank accession #BK010471), CrAssphage apr34_000142F (MK415399), CrAssphage ES_ALL_000190F (MK415403), CrAssphage FA1–2_000172F (MK415404), CrAssphage GF1–2_000079F (MK415408), CrAssphage LMMB (MT006214), CrAssphage sp. O-152 (MK069403) and CrAssphage YS1–2_2437 (MK415410). The five South African crAssphage genomes (referred by the patient fecal sample ID M186D4, C0521BD4, C0521BW15, C0526BW15 and C0531BW4) were fully closed with 6–420-fold median coverage (Figure 1A). We identified and annotated >80 ORFs (Figure 1C) and protein coding sequences. Of the 10 candidate genera proposed by Guerin et al (2018), the crAssphages in Figure 1 belonged in candidate genus I, with a genome-wide GC content of 29%. The two crAssphages from the same infant at day 4 (crAssphage C0521BD4, MW067000) and week 15 (crAssphage C0521BW15, MW067001) are 100% identical likely suggesting a dominant variant or temporal stability of the crAssphage. In general, the five South African crAssphages (Figure 1) all are more closely related to each other, sharing >93% genome-wide pairwise identity, versus 83–91% identity to the other eight most closely related crAsspages from Japan and Mexico, as well as the composite assembly of uncultured crAssphage (BK010471). Thus, it seems that the 13 crAssphages listed in Figure 1 form a distinct group of closely related phages.

Figure 1. Summary of crAssphage genomes identified in this study (in bold) as well as those that are most closely related.

A. Details of the read coverage and mapping for the five South African crAssphages identified in study and a pairwise identity comparison of the most closely related crAssphage genomes. B. An unrooted Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree inferred using PHYML 3.0 (Criscuolo, 2011) with substitution model GTR+G+I. Bootstrapped (1000 iterations) branch support is provided at each branch. C. Illustration of the crAssphages genome organization. Genes /coding regions discusses further in the manuscript are color codes. Blastn based similarity between genomes was determined using EasyFig (Sullivan et al., 2011) are shown.

For variant analysis, trimmed paired end reads were mapped to the genomes of the five South Africa crAssphages using the BWA v0.7.15 with default parameters (Li and Durbin, 2009). Samtools (v0.1.19) mpileup utility (Li et al., 2009) was used to calculate the per-nucleotide read coverage and variant frequency. Variants were detected and filtered using VarScan (Koboldt et al., 2009). Variants were only investigated further if there were, at minimum, five high quality reads supporting the variant, which was the lowest threshold for significance in our dataset utilizing an α value of 0.05. P values were calculated using a Fisher’s Exact test on read counts supporting the reference and variant alleles using VarScan (Table S1). Functional effects of identified variants were predicted using SnpEff (Cingolani et al., 2012) against a custom annotation database generated as part of this study and annotated as nonsynonymous (Nd) or synonymous (Sd) substitutions. The total number of nonsynonymous (N) and synonymous (S) sites for each protein coding sequence was calculated using SnpGenie (Nelson et al., 2015). The numbers of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions per site were estimated using the Jukes-Cantor formula:

where pN and pS indicate the proportions of nonsynonymous and synonymous substitutions, respectively, and can be estimated by and .

Across the genome assembled from the adult woman, crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400), we detected 40 significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and one insertion. After filtering, 40 SNPs were retained, of which 37 fell within coding regions (Table 1), leading to a variation rate of 1 variant per 2,443 nucleotides. The nucleotide substitution profile was composed of 33 transitions and 7 transversions, for a transition to transversion ratio of 4.71. Of the 37 variants that occurred within coding regions, 30 (78.9%) resulted in nonsynonymous substitutions (Nd), seven (18.4%) resulted in synonymous (Sd) mutations, and only one (2.6%) resulted in a nonsense mutation. The only insertion fell within a coding sequence for a tail tubular protein P22 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Functional annotation of variants in crAssphages M186D4, C0521BW15, and C0526BW15.

| Genome | Gene | Start | Stop | Length | Direction | Nd | Nonsense mutations | Sd | Insertion | N | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M186D4 | putative ssb single stranded DNA-binding protein | 388 | 1215 | 827 | forward | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 631.5 | 193.5 |

| M186D4 | hypothetical protein | 1381 | 1725 | 345 | forward | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 267.8333333 | 74.16666667 |

| M186D4 | putative SWI2/SNF2 ATPase 252C non-canonical Walker A motif | 19772 | 20590 | 819 | forward | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 645 | 171 |

| M186D4 | putative deoxynucleoside monophosphate kinase | 20936 | 21811 | 876 | forward | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 684 | 189 |

| M186D4 | coil containing protein | 22045 | 22827 | 783 | forward | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 619.6666667 | 160.3333333 |

| M186D4 | putative RNAP catalytic subunit fused to unknown RNAP subunit | 29489 | 41764 | 12276 | reverse | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 8090.833333 | 2295.166667 |

| M186D4 | putative RNAP associated protein fused to zincinprotease | 41832 | 47720 | 5889 | reverse | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3900.833333 | 1085.166667 |

| M186D4 | putative tail tubular protein P22 gp4 | 58024 | 59040 | 1016 | reverse | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 683.6666667 | 174.3333333 |

| M186D4 | putative phage tail fiber protein (DUF3751) | 61309 | 62769 | 1461 | reverse | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 984.3 | 260.67 |

| M186D4 | putative tail protein | 65848 | 66618 | 770 | reverse | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 498.3333333 | 137.6666667 |

| M186D4 | putative Bacon (Bacteroidetes-Associated Carbohydrate-binding) domain containing protein | 69585 | 73469 | 3885 | reverse | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2600.5 | 780.5 |

| M186D4 | putative tail protein | 73473 | 74294 | 821 | reverse | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 528.6666667 | 155.3333333 |

| M186D4 | putative tail fiber protein | 74320 | 76413 | 2093 | reverse | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1367.833333 | 402.1666667 |

| M186D4 | putative plasmid replication initiation protein RepL | 96778 | 97632 | 855 | forward | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 678.1666667 | 173.8333333 |

| C0521BW15 | putative phage tail fiber protein (DUF3751) | 62256 | 63716 | 1460 | reverse | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1081.666667 | 322.3333333 |

| C0526BW15 | hypothetical protein | 84080 | 85237 | 1157 | reverse | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 662.6666667 | 201.3333333 |

| C0526BW15 | putative phage tail fiber protein (DUF3751) | 63302 | 64762 | 1460 | reverse | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 905.1666667 | 246.8333333 |

| C0526BW15 | putative tail protein | 75466 | 76260 | 794 | reverse | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 492.8333333 | 128.1666667 |

| C0526BW15 | putative tail protein | 78409 | 81015 | 2606 | reverse | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1599.666667 | 461.3333333 |

Nd, Nonsynonymous mutations; Sd, synonymous mutations; N, nonsynonymous sites; S, synonymous sites

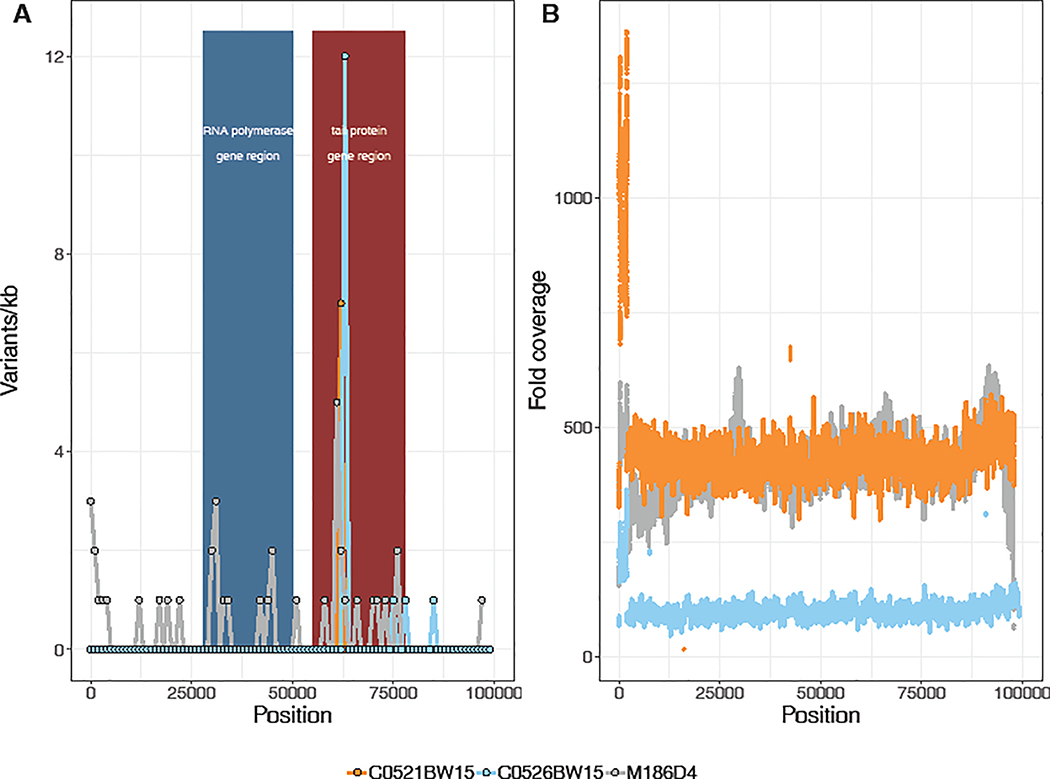

The distribution of SNPs across the genome of crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400) was nonuniform. An accumulation of mutations was apparent in two distinct genomic regions (Figure 2). These occurred in RNA polymerase genes that lie within genomic regions from ~30,000–48,000 nts and phage tail proteins in genomic regions from ~58,000–76,000 nts. Averaged across the genome, the dN/dS ratio was 0.54. When considering only RNA polymerase genes, the dN/dS ratio was 1.89. In phage tail proteins, dN/dS ratio was even further elevated, at 2.66. The gene with the highest SNP count was a putative phage tail-collar protein (DUF3751), which had a total of seven SNPs (Table 1). The variant with the highest frequency across the dataset was a T → C transition occurring within a putative Bacteroides-associated carbohydrate-binding often N-terminal (BACON) domain containing protein. When removing genes encoding RNA polymerase subunits and phage tail proteins from consideration, the genome-wide dN/dS ratio fell to 0.34.

Figure 2. Selective pressures are variable across the genome of several South African crAssphages.

A. The distribution of variants per kilobase across the genomes of three South African crAssphages. The region encoding RNA polymerase genes is colored blue. The region encoding phage tail proteins is colored red. B. The fold coverage of quality filtered reads across the genomes of each crAssphage taxon. CrAssphages M186D4 (MK238400) in grey lines, C0521BW15 (MW067001) in orange lines, C0526BW15 (MW067002) in blue lines.

To assess whether selective pressures were elevated in these genes across distinct crAssphage taxa, we performed variant annotation and analysis of the original crAssphage genome sequence (referenced here as uncultured crAssphage (BK010471); Figure S1, Table S2), as well as the two additional novel genomes generated as part of this study with sufficient high-quality reads of >50x median coverage. Many publicly available complete crAssphage genome sequences have been cross assembled from multiple individuals or represent pooled samples (Dutilh et al., 2014; Reyes et al., 2010; Shkoporov et al., 2018), which may introduce significant sequence variation and confound variant analysis. However, the individual datasets from which uncultured crAssphage (BK010471) was cross assembled were primarily composed of related mother-child pairs with low interpersonal viral diversity, thus representing an attractive option for cross validation (Reyes et al., 2010). Raw nucleotide sequences were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) from Study SRP002523. The raw reads from SRA sample SRR073438 were selected for variant analysis because that sample was collected exclusively from a related mother-twin triad. Genes and annotations were transferred from the associated published genome (GenBank accession #BK010471) using Prokka (Seemann, 2014). As observed for crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400), we detected a nonuniform distribution of SNPs across the genome of uncultured crAssphage (BK010471), despite even sequencing depth (Figure S1). Consistent with observations from crAssphage M186D4, SNPs persistently occurred in genes annotated as RNA polymerase and tail proteins, often resulting in nonsynonymous substitutions (Table S2). For uncultured crAssphage (BK010471), the genes with the highest SNP counts were a putative tail fiber protein and putative tail protein UGP073, both with three nonsynonymous substitutions (Nd) and zero synonymous substitutions (Sd, Table S2). Because all synonymous substitutions (Sd) occurring at significant levels were distributed across protein coding genes other than RNA polymerase and tail protein genes, we were not able to calculate dS values for those genes. However, average dN values were similar to those observed in tail protein genes in crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400) (uncultured crAssphage (BK010471): 0.0017, crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400): 0.0029). Similarly, for RNA polymerase genes, dN values were comparable between both genomes (uncultured crAssphage (BK010471): 0.0002, crAssphage M186D4 (MK238400): 0.0008). We performed variant analysis on two of the additional novel taxa identified in this study which both closed with >50x coverage. Uncultured crAssphages C0521BW15 (MW067001) and C0526BW15 (MW067002) displayed comparable dN values in tail protein genes (Figure 2; Table S2).

As an ecological niche, the gut environment imposes a dynamic range of selective pressures on the genomes of gut microbiota. Here, we assembled and analyzed five novel circularized full genomes of human crAssphages with >90% sequence similarity to that of the first described crAssphage genome (Dutilh et al., 2014). We identified differential selective pressures along these genomes, with hotspots of selection targeting groups of genes. We present evidence of substantial genetic heterogeneity and dynamic selective pressure across the genome of crAssphages M186D4 (MK238400), C0521BW15 (MW067001), C0526BW15 (MW067002), and uncultured crAssphage (BK010471). Many nucleotide polymorphisms occurred in protein coding regions and yielded a high ratio of substitution rates at nonsynonymous to synonymous sites (dN/dS) differentially across the genome, specifically implying strong positive selection at RNA polymerase and phage tail protein genes, and purifying selection genome wide.

The genomic selective pressures that we detected were primarily focused on two regions undergoing relatively elevated positive selection. These regions, from 30–48kb and 58–76kb, are comprised of genes from various clusters of orthologous groups (COGs), but the variation was localized into genes annotated as RNA polymerase subunits and phage tail proteins, respectively. Phage tail proteins are essential in mediating bacterial cell attachment and genome delivery. The putative protein with the highest SNP count and most variants is the putative phage tail fiber protein (DUF3751). This protein, while functionally uncharacterized, has been shown to mediate antagonistic interactions with bacterial taxa and is a conserved element in phage-derived bacterial tailocin complexes (Ghequire et al., 2015). Tailocins are bacterial protein complexes co-opted from bacteriophage that are morphologically and functionally similar to phage tail proteins and are critical to eukaryotic and bacterial cell binding (Ghequire and De Mot, 2015; Hockett et al., 2015). Yutin et al. predicted that crAssphages likely possessed a Podoviridae-like morphology based on protein sequence analysis (Yutin et al., 2018), and Shkoporov et al. confirmed this for the crass-like phage, ΦcrAss001, using imaging approaches (Shkoporov et al., 2018). However, most of the genomic variability between ΦcrAss001 and other crAssphages exists in the region encoding for tail proteins (Shkoporov et al., 2018), making direct comparison difficult. As such, it remains unclear if the putative DUF3751 tail fiber protein discussed here is involved in structural or host receptor recognition, attachment or adsorption functions. Additionally, we detected a high frequency variant in the BACON domain containing protein. de Jonge et al. recently showed that in crAssphage taxa where the BACON domain gene is proximal to tail protein genes, there is elevated evolutionary expansion of the crAss-BACON ORF, suggesting a potential role in Bacteroides cell surface binding (Jonge et al., 2019). Though it is unclear how this domain physically interacts with bacterial cell receptors, positive selection along this gene and tail proteins may represent a Red Queen scenario where the phage tail protein is adapting to constantly evolving target cell surface proteins. It is well known that coevolution with bacterial hosts directs phage genomic evolution and selective pressures. Adaptive evolution of phage tail proteins has been well documented in marine bacteriophage communities (Angly et al., 2009) and has been shown to facilitate an expanded host range. Our analysis of geographically distinct crAssphage variants, here, as well as recent work by Siranosian et al. suggest this phenomenon may also occur in the human gut (Siranosian et al., 2020). Additionally, long-term (23 day) phage/B. intestinalis co-cultivation experiments have shown that founder strains of crAssphage have severely limited ability to infect bacterial strains passaged for the length of the experiment (Shkoporov et al., 2018) indicating rapid, likely antagonistic, coevolution between crAssphage and bacterial host strains. This reduction in infection rate likely reflects nonsynonymous changes in bacterial cell surface receptors that are mediated by interaction with crAssphage tail proteins.

In summary, our results suggest genome-wide purifying selection in South African crAssphages, with episodic shifts of strong positive selection within RNA polymerase and phage tail protein genes. Elevated selective pressure of phage tail proteins may be due to antagonistic coevolution between crAssphage and bacterial targets, though further work is needed to demonstrate this conclusively.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Five complete crAssphage genomes from feces of South African woman and unrelated infants.

Elevated positive selection in RNA polymerase and phage tail protein genes.

Hotspots of selection may be mediated by selection pressure from bacterial partners.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the InFANT study team for collecting samples. We also thank all participants in the study for providing samples.

Funding: This study was funded in part by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program under award number P30AI027757, supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, NIDDK), and R01HD10223901A1. The InFANT study cohort was supported in part by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research HIV Vaccine Initiative grant number 01044-000, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH, grant numbers R01AI131302, AI120714-01A1 and R01HD102239-01A1. BPB is supported by F32 HD102290-01. DC is supported by a Wellcome Trust DELTAS Africa grant to the SANTHE programme (grant #107752/Z/15/Z).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability:

The annotated genome sequences for crAssphages M186D4, C0521BD4, C0521BW15, C0526BW15, C0531BW4, are available under GenBank accession numbers MK238400, MW067000, MW067001, MW067002, and MW067003, respectively. Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI SRA under BioProject PRJNA526942. The data, functions, and R script are available at https://github.com/itsmisterbrown/crAssphage_M186D4_analyses.

References

- Altschul SF, Lipman DJ, 1990. Protein database searches for multiple alignments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87(14), 5509–5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angly F, Youle M, Nosrat B, Srinagesh S, Rodriguez-Brito B, McNairnie P, Deyanat-Yazdi G, Breitbart M, Rohwer F, 2009. Genomic analysis of multiple Roseophage SIO1 strains. Environ Microbiol 11(11), 2863–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B, 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30(15), 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhurst MA, Morgan AD, Fenton A, Buckling A, 2007. Experimental coevolution with bacteria and phage. The Pseudomonas fluorescens--Phi2 model system. Infect Genet Evol 7(4), 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM, 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6(2), 80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criscuolo A, 2011. morePhyML: improving the phylogenetic tree space exploration with PhyML 3. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution 61(3), 944–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher AL, Harmon D, Kasif S, White O, Salzberg SL, 1999. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic acids research 27(23), 4636–4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh BE, Cassman N, McNair K, Sanchez SE, Silva GG, Boling L, Barr JJ, Speth DR, Seguritan V, Aziz RK, Felts B, Dinsdale EA, Mokili JL, Edwards RA, 2014. A highly abundant bacteriophage discovered in the unknown sequences of human faecal metagenomes. Nat Commun 5, 4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RA, Vega AA, Norman HM, Ohaeri M, Levi K, Dinsdale EA, Cinek O, Aziz RK, McNair K, Barr JJ, Bibby K, Brouns SJJ, Cazares A, de Jonge PA, Desnues C, Diaz Munoz SL, Fineran PC, Kurilshikov A, Lavigne R, Mazankova K, McCarthy DT, Nobrega FL, Reyes Munoz A, Tapia G, Trefault N, Tyakht AV, Vinuesa P, Wagemans J, Zhernakova A, Aarestrup FM, Ahmadov G, Alassaf A, Anton J, Asangba A, Billings EK, Cantu VA, Carlton JM, Cazares D, Cho GS, Condeff T, Cortes P, Cranfield M, Cuevas DA, De la Iglesia R, Decewicz P, Doane MP, Dominy NJ, Dziewit L, Elwasila BM, Eren AM, Franz C, Fu J, Garcia-Aljaro C, Ghedin E, Gulino KM, Haggerty JM, Head SR, Hendriksen RS, Hill C, Hyoty H, Ilina EN, Irwin MT, Jeffries TC, Jofre J, Junge RE, Kelley ST, Khan Mirzaei M, Kowalewski M, Kumaresan D, Leigh SR, Lipson D, Lisitsyna ES, Llagostera M, Maritz JM, Marr LC, McCann A, Molshanski-Mor S, Monteiro S, Moreira-Grez B, Morris M, Mugisha L, Muniesa M, Neve H, Nguyen NP, Nigro OD, Nilsson AS, O’Connell T, Odeh R, Oliver A, Piuri M, Prussin Ii AJ, Qimron U, Quan ZX, Rainetova P, Ramirez-Rojas A, Raya R, Reasor K, Rice GAO, Rossi A, Santos R, et al. , 2019. Global phylogeography and ancient evolution of the widespread human gut virus crAssphage. Nature microbiology 4(10), 1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghequire MG, Dillen Y, Lambrichts I, Proost P, Wattiez R, De Mot R, 2015. Different Ancestries of R Tailocins in Rhizospheric Pseudomonas Isolates. Genome Biol Evol 7(10), 2810–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghequire MGK, De Mot R, 2015. The Tailocin Tale: Peeling off Phage Tails. Trends in microbiology 23(10), 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez P, Buckling A, 2011. Bacteria-phage antagonistic coevolution in soil. Science 332(6025), 106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin E, Shkoporov A, Stockdale SR, Clooney AG, Ryan FJ, Sutton TDS, Draper LA, Gonzalez-Tortuero E, Ross RP, Hill C, 2018. Biology and Taxonomy of crAss-like Bacteriophages, the Most Abundant Virus in the Human Gut. Cell host & microbe 24(5), 653–664 e656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockett KL, Renner T, Baltrus DA, 2015. Independent Co-Option of a Tailed Bacteriophage into a Killing Complex in Pseudomonas. mBio 6(4), e00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonge PA, Meijenfeldt F, Rooijen LEV, Brouns SJJ, Dutilh BE, 2019. Evolution of BACON Domain Tandem Repeats in crAssphage and Novel Gut Bacteriophage Lineages. Viruses 11(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A, 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28(12), 1647–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt DC, Chen K, Wylie T, Larson DE, McLellan MD, Mardis ER, Weinstock GM, Wilson RK, Ding L, 2009. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics 25(17), 2283–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraberger S, Waits K, Ivan J, Newkirk E, VandeWoude S, Varsani A, 2018. Identification of circular single-stranded DNA viruses in faecal samples of Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis), moose (Alces alces) and snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) inhabiting the Colorado San Juan Mountains. Infect Genet Evol 64, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R, 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25(14), 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing, S., 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25(16), 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiny JB, Riemann L, Marston MF, Middelboe M, 2014. Antagonistic coevolution of marine planktonic viruses and their hosts. Ann Rev Mar Sci 6, 393–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minot S, Sinha R, Chen J, Li H, Keilbaugh SA, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD, 2011. The human gut virome: inter-individual variation and dynamic response to diet. Genome research 21(10), 1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CW, Moncla LH, Hughes AL, 2015. SNPGenie: estimating evolutionary parameters to detect natural selection using pooled next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31(22), 3709–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurk S, Meleshko D, Korobeynikov A, Pevzner PA, 2017. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome research 27(5), 824–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A, Haynes M, Hanson N, Angly FE, Heath AC, Rohwer F, Gordon JI, 2010. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature 466(7304), 334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan PD, 2017. Bacteria-Bacteriophage Coevolution in the Human Gut: Implications for Microbial Diversity and Functionality. Trends in microbiology 25(8), 614–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DA, Lindell D, 2017. Genetic hurdles limit the arms race between Prochlorococcus and the T7-like podoviruses infecting them. The ISME journal 11(8), 1836–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T, 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30(14), 2068–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkoporov AN, Khokhlova EV, Fitzgerald CB, Stockdale SR, Draper LA, Ross RP, Hill C, 2018. PhiCrAss001 represents the most abundant bacteriophage family in the human gut and infects Bacteroides intestinalis. Nat Commun 9(1), 4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siranosian BA, Tamburini FB, Sherlock G, Bhatt AS, 2020. Acquisition, transmission and strain diversity of human gut-colonizing crAss-like phages. Nat Commun 11(1), 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA, 2011. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27(7), 1009–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchakoute CT, Sainani KL, Osawe S, Datong P, Kiravu A, Rosenthal KL, Gray CM, Cameron DW, Abimiku A, Jaspan HB, team I.s., 2018. Breastfeeding mitigates the effects of maternal HIV on infant infectious morbidity in the Option B+ era. AIDS 32(16), 2383–2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutin N, Makarova KS, Gussow AB, Krupovic M, Segall A, Edwards RA, Koonin EV, 2018. Discovery of an expansive bacteriophage family that includes the most abundant viruses from the human gut. Nature microbiology 3(1), 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The annotated genome sequences for crAssphages M186D4, C0521BD4, C0521BW15, C0526BW15, C0531BW4, are available under GenBank accession numbers MK238400, MW067000, MW067001, MW067002, and MW067003, respectively. Raw sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI SRA under BioProject PRJNA526942. The data, functions, and R script are available at https://github.com/itsmisterbrown/crAssphage_M186D4_analyses.