Abstract

Key steps in the functionalization of an unactivated arene often involve its dihaptocoordination by a transition metal followed by insertion into the C–H bond. However, rarely are the η2-arene and aryl hydride species in measurable equilibrium. In this study, the benzene/phenyl hydride equilibrium is explored for the {WTp(NO)(PBu3)} (Bu = n-butyl; Tp = trispyrazoylborate) system as a function of temperature, solvent, ancillary ligand, and arene substituent. Both face-flip and ring-walk isomerizations are identified through spin-saturation exchange measurements, which both appear to operate through scission of a C–H bond. The effect of either an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituent is to increase the stability of both arene and aryl hydride isomers. Crystal structures, electrochemical measurements, and extensive NMR data further support these findings. Static density functional theory calculations of the benzene-to-phenyl hydride landscape suggest a single linear sequence for this transformation involving a sigma complex and oxidative cleavage transition state. Static DFT calculations also identified an η2-coordinated benzene complex in which the arene is held more loosely than in the ground state, primarily through dispersion forces. Although a single reaction pathway was identified by static calculations, quasiclassical direct dynamics simulations identified a network of several reaction pathways connecting the η2-benzene and phenyl hydride isomers, due to the relatively flat energy landscape.

Graphical Abstarct

INTRODUCTION

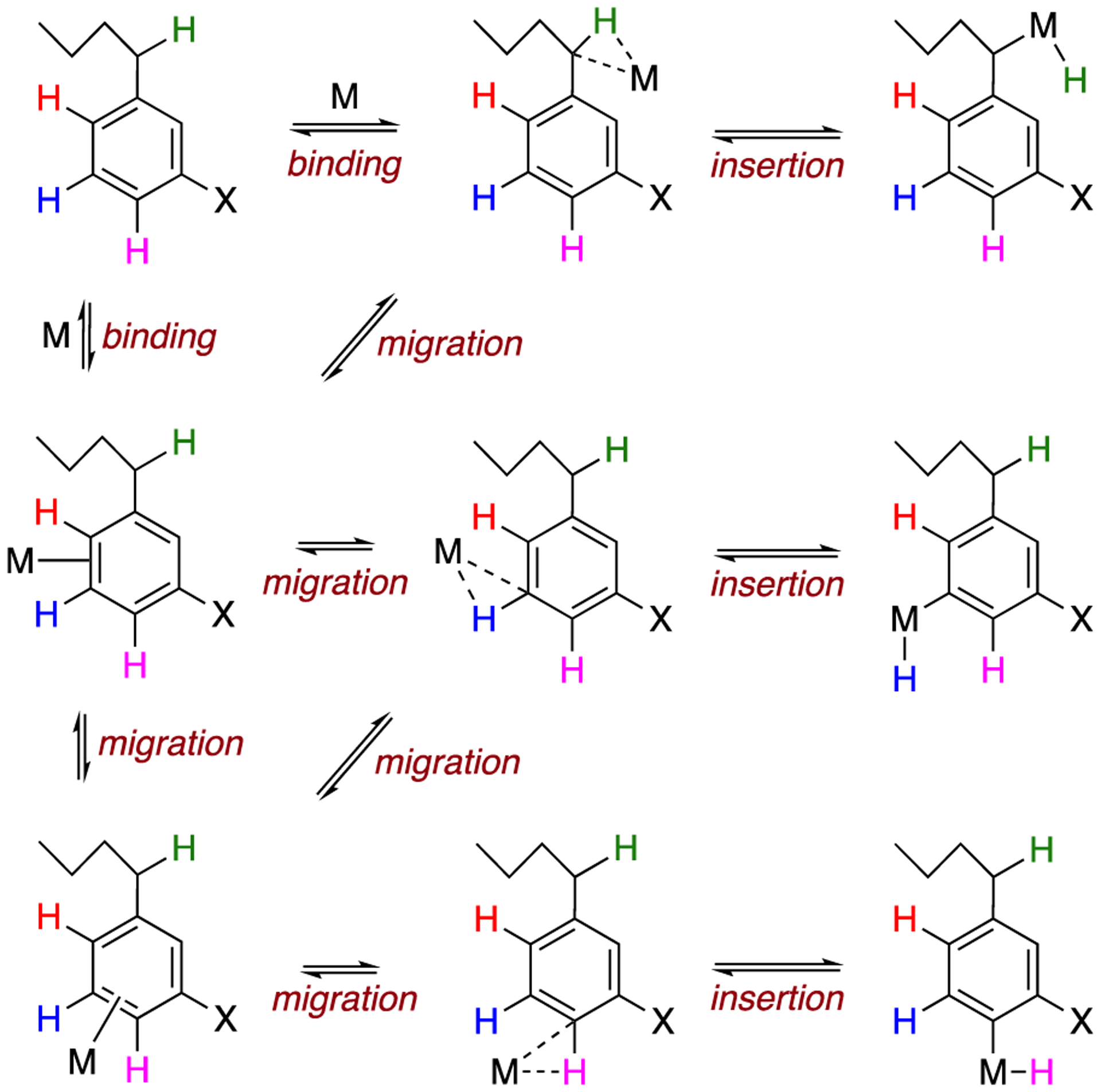

A major frontier of current synthetic-methods research is the functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds.1–4 For those methods employing π-basic transition-metal catalysts, the key step often involves the insertion of the metal (i.e., oxidative addition), and numerous studies have been carried out on systems that model this process.5–11 For aromatic molecules, chemoselectivity is a critical issue, not only between sp2 vs sp3 (e.g., benzylic) carbons but also between different positions within the aromatic ring. The latter is determined by both thermodynamic and kinetic factors, not only for insertion but also for the binding and migration events that precede it (Scheme 1). Thus, understanding the parameters for these processes, and how each is affected by substituents on the arene (X) and the electronic character of the metal (M), is key to designing high-performance, chemoselective catalysts.

Scheme 1.

Activation of an Aryl C–H Bond through Binding, Migration, and Insertion

Oxidative addition of an aryl C–H bond is typically thought to occur by the linear sequence of dihaptocoordination followed by C–H σ-bond coordination and cleavage to generate an aryl hydride (Scheme 1). This mechanism has been supported by equilibrium observations and kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) that suggest the existence of intermediates prior to metal insertion into the C–H bond.12,13 However, in many circumstances it is not known whether the intermediate is exclusively an η2-arene complex or also a “σ-complex”, where the metal straddles the C–H bond. Importantly, Bergman, Parkin, and others have demonstrated that dihapto π-coordination is not always a necessary precondition to C–H oxidative addition.13,14

Binding in η2-arene complexes ranges from relatively weak acid-base adducts15 to strong metal-arene bonding fortified through significant π-interactions. For the latter case, either the η2-arene complex, the aryl hydride, or in rare circumstances an equilibrium of both can be observed, depending on the metal, supporting ligands, and arene substrate.16–20 For example, Jones showed that at 60 °C, RhCp*(PMe3)(η2-naphthalene) exists in a 1:2 equilibrium ratio with RhCp*(PMe3)-(naphthyl)(H).21,22 This ratio can be altered by adjusting auxiliary ligands or temperature.22 However, for benzene, only the phenyl hydride was observed. In contrast, the pseudo-octahedral d6 benzene complexes of [Os(NH3)5]2+,23 {ReTp-(CO)(L)},24 and {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}17 resist the formation of a seven-coordinate phenyl hydride, and thus η2-benzene complexes are not only generally observed but are sufficiently stable that organic reactions can be carried out on the bound arene.17,23,24 Significantly, in the case of the tungsten complex WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene), a second set of resonances in the 1H NMR spectrum is observed (~10% of the major isomer) in acetone solution at 0 °C that includes a hydride signal at 9.32 ppm (JPH = 101 Hz; acetone). This feature suggests the presence of an observable η2-benzene/phenyl hydride equilibrium.25

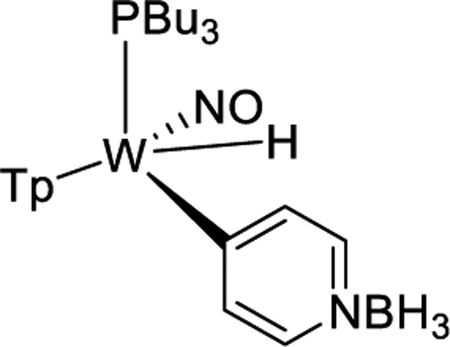

Herein, we report that for the system WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene), the replacement of PMe3 by PBu3 shifts the benzene/phenyl hydride equilibrium from a 10:1 to a 1:2.5 ratio (0 °C), making it an ideal candidate for a more in-depth study of the insertion process. Below, we examine the details of this equilibrium using 1H NMR NOESY experiments and thermodynamic data. Significantly, the hydride resonance corresponding to WTp(NO)(PBu3)(Ph)(H) is observed to undergo spin-saturation exchange with all six proton resonances of the η2-arene isomer. Additionally, there is rapid ring-walking around the benzene π-framework without a significant KIE or equilibrium isotope effect (EIE). We also explore the effects of various arene substituents (X; Scheme 1), where NOESY experiments reveal a face-flip isomerization process occurring at roughly the same rate as the oxidative addition.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations are used to outline the energy landscape for the WTp(NO)(PR3)(η2-benzene) → WTp(NO)(PR3)(Ph)(H) (R = Me and Bu) isomerization. These calculations show that on the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC),26 a σ-complex intervenes between the phenyl hydride and η2-form. Additionally, these static DFT calculations identify a direct π-coordination transition state as well as a long-range noncovalent W-benzene complex. Because the energy surface for η2-benzene → phenyl hydride isomerization is relatively flat and contains several weakly coordinating benzene intermediates, we used DFT quasiclassical direct dynamics simulations to examine transition-state connections. This revealed a network of isomerization pathways with non-IRC connections and nonstatistical intermediates.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthesis and Equilibrium Studies.

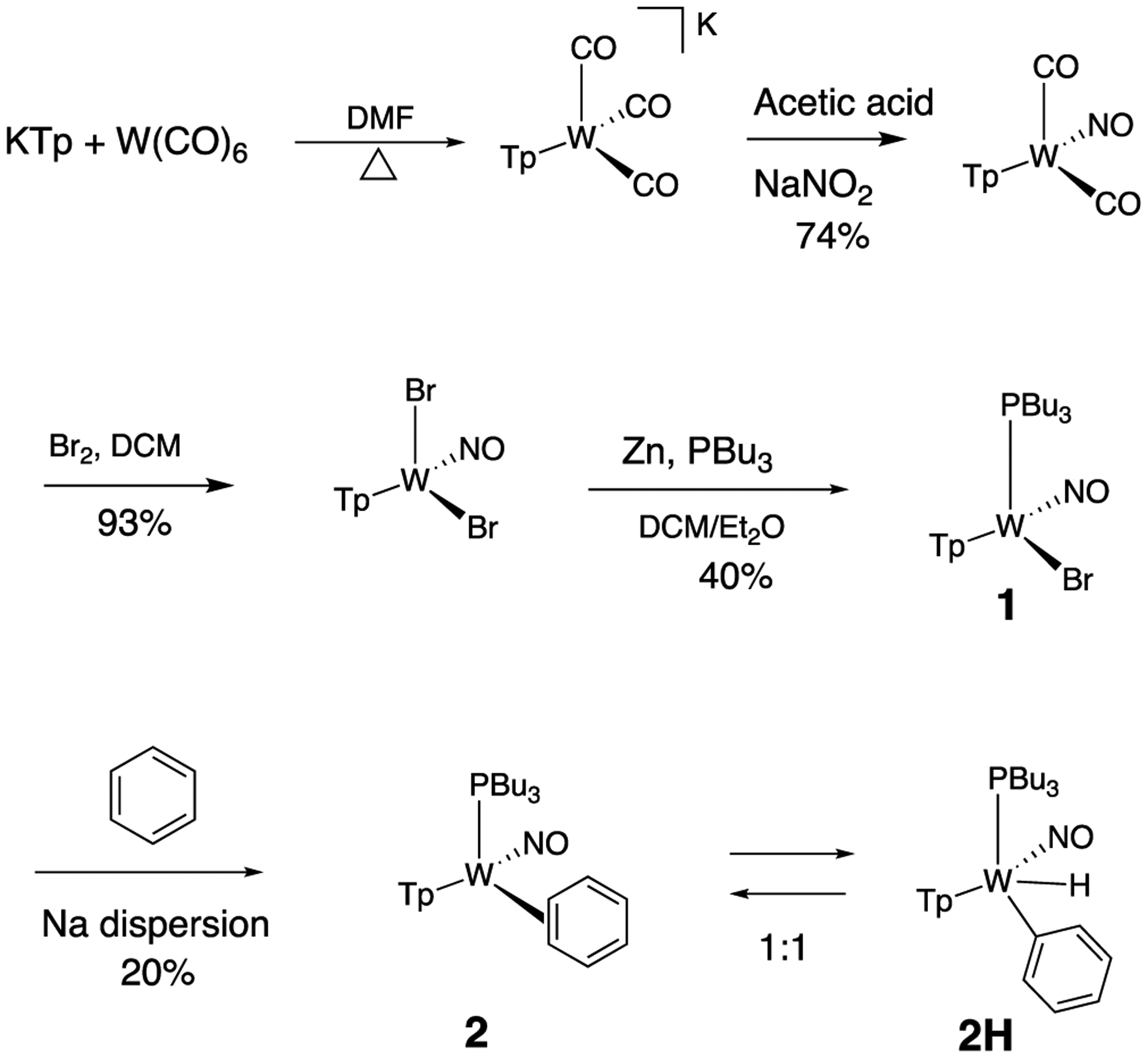

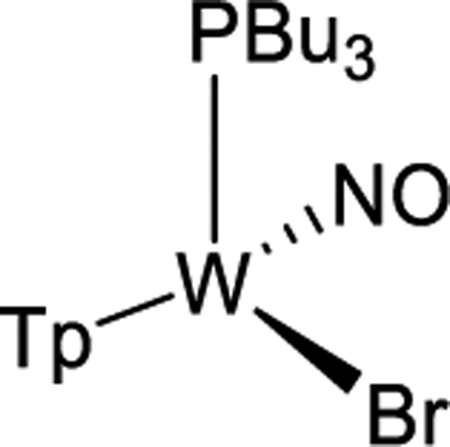

Using a modified literature procedure,27 WTp(NO)Br2 was prepared from W(CO)6 (Scheme 2). Combining WTp(NO)(Br)2 and PBu3 with zinc dust in a DCM/ether solvent mixture resulted in the formation of WTp(PBu3)(NO)(Br) (1). Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown of this paramagnetic complex via vapor diffusion of ether into a DCM solution of 1, and details are included in the Supporting Informaton. Infrared and electrochemical data (Supporting Informaton) are similar to those reported previously for WTp(PMe3)(NO)(Br).27

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Benzene Complex (2) and Its Phenyl Hydride Isomer (2H)

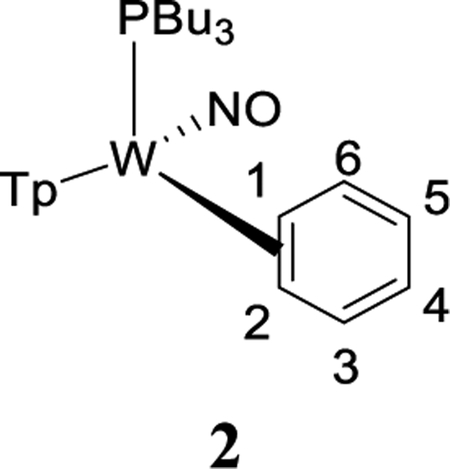

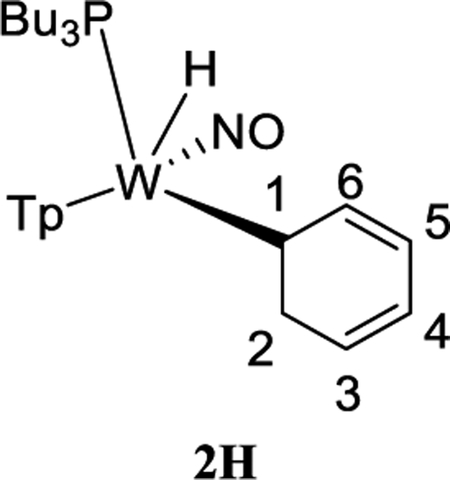

Treatment of 1 with sodium dispersed in benzene yields complex 2, isolated in 20% yield after chromatography. Complex 2 features an anodic wave in a cyclic voltammogram at Ep,a = −0.16 V, which is consistent with data collected for the η2-bound benzene complex WTp(NO)(PMe3)(benzene) (cf. −0.13 V).27 1H NMR analysis confirmed the identity of 2 as WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-benzene) in solution. However, a second set of NMR signals of equal intensity indicated the presence of the phenyl hydride isomer WTp(NO)(PBu3)(H)(Ph) (2H). Notably, 2H features a hydride doublet at 9.62 ppm (JPH = 97.3 Hz) that is accompanied by 183W satellites (JWH = 32.1 Hz). At 25 °C, 2 has a substitution half-life (t1/2 = 4 min) that is significantly less than its PMe3 complex (cf. t1/2 = 66 min).27 A weak IR absorption observed at 1989 cm−1 (cf. DFT prediction 1988 cm−1) taken of an isolated solid of 2/2H is tentatively assigned to a W–H vibrational mode. Even as a solid stored at −30 °C under inert atmosphere, the 2/2H mixture decomposes to uncharacterized paramagnetic materials after several weeks.

The equilibrium ratio of 2:2H in benzene-d6 is 1:1. When the isolated solid of 2/2H obtained from an ether/pentane precipitation was added to a cold solution (~10 °C) of benzene-d6 and monitored, an initial ratio of 2:2H of 1:3 was observed, which over time returned to a 1:1 ratio. While these observations suggest that the solid was enriched in the hydride isomer, attempts to grow crystals of 2H suitable for X-ray diffraction were unsuccessful.

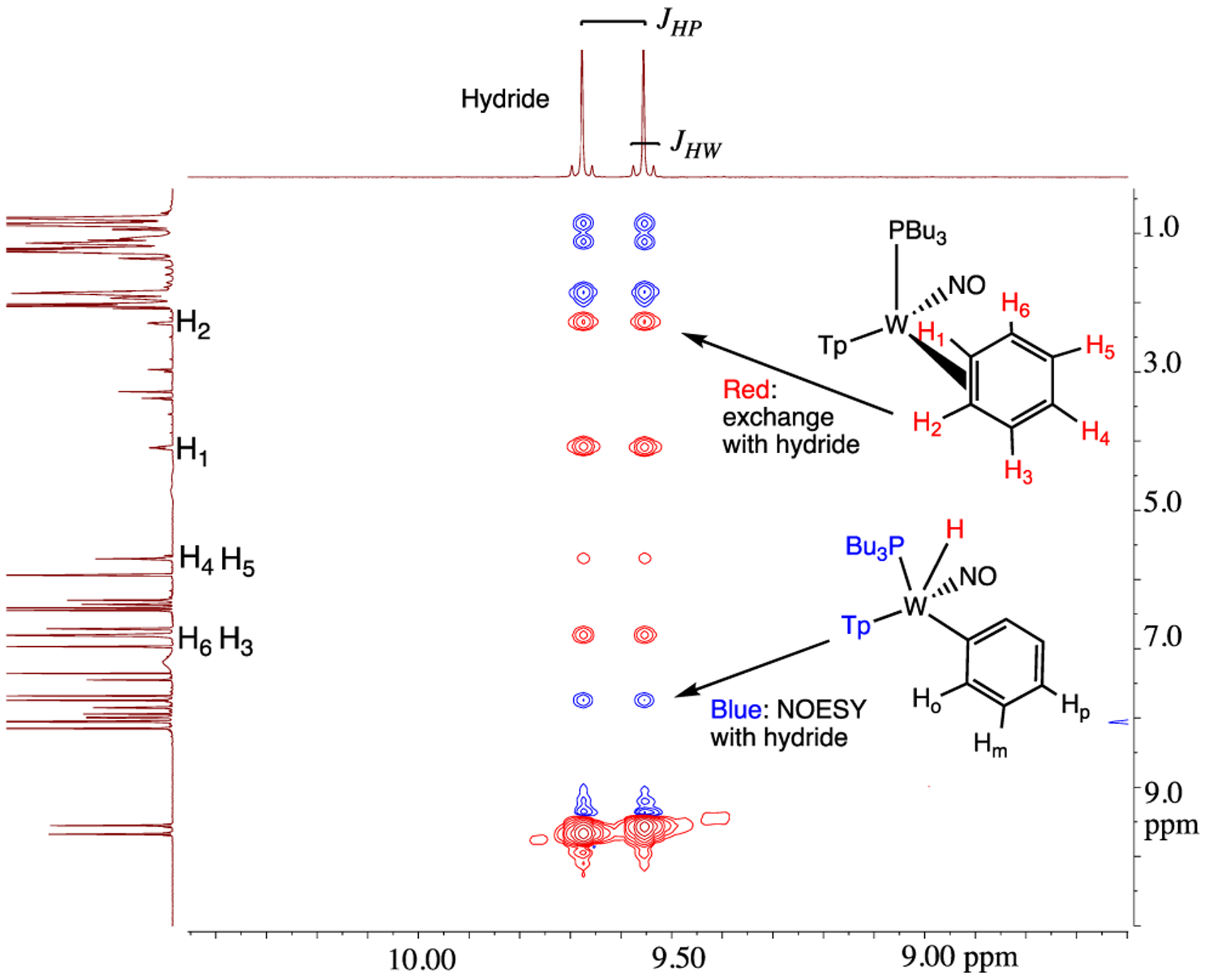

To better understand the mechanics of the 2/2H conversion, we carried out 1H NMR NOESY experiments of this mixture as an acetone-d6 solution at 0 °C (Figure 1). The η2-benzene complex (2) shows spin-saturation exchange with the phenyl hydride (2H), indicating that these two species are in dynamic equilibrium. Specifically, the tungsten hydride proton undergoes chemical exchange with every benzene ring proton of the dihaptocoordinated isomer, demonstrating that interconversion between 2 and 2H occurs on the seconds time scale at 0 °C. An exchange process was also detected between the benzene hydrogens in 2. A similar ring-walk was observed for the PMe3 analogue (0 °C).

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectrum of the hydride region and its NOESY correlations of 2/2H.

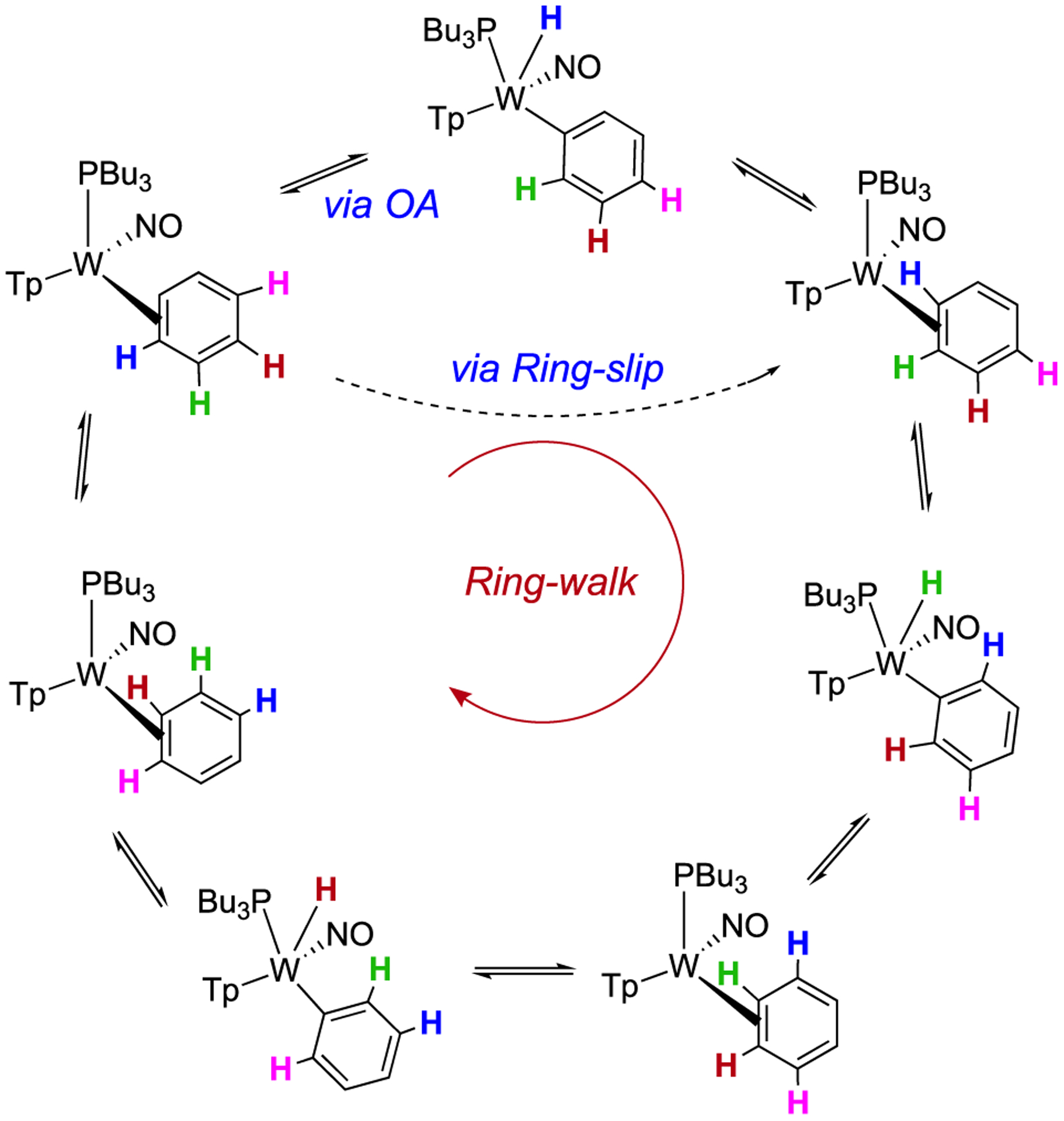

Using the H1 proton for 2 and line-broadening techniques, ΔG‡ for proton exchange within 2 was determined to be 16 ± 2 kcal/mol (35 °C). Similar correlation intensities in the NOESY data for both the benzene ring-walk (e.g., H1 of 2 ⇔ H6 of 2) and phenyl hydride (e.g., W–H of 2H ⇔ H1 of 2) exchanges suggest that these rates are similar if not identical. Using Tp4 protons that distinguish 2 from 2H, a free energy of activation (ΔG‡) for the conversion of 2 to 2H was determined to be 15 ± 2 kcal/mol (at the coalescence temperature of 44 °C). This value is similar to that determined for the ring-walk of 2 and suggests that the ring-walk process may involve C–H insertion (Scheme 3). However, the available data cannot rule out an alternative mechanism in which the tungsten moves from 1,2-η2 to 2,3-η2 without insertion into a C–H bond. This “ring-slip” pathway (i.e., an intrafacial isomerization) is shown in Scheme 3 for comparison. We note that NOESY data recorded for the deuterated analogue WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-benzene-d6) (2-d6) show correlation intensities resulting from exchange for the Tp ring protons that appear practically identical to what was observed for 2. This observation indicates that there is not a major kinetic or thermodynamic isotope effect for the oxidative addition process.

Scheme 3.

Isomerization and Spin-Saturation Exchange (Represented by Blue-, Green-, Red-, and Pink-Colored Hydrogens) for the Phenyl Hydride Complex (2H) and Its Benzene Isomer (2)

Static DFT Landscape for the C–H Insertion.

NOESY experiments established the dynamic equilibrium of the η2-benzene (2) and phenyl hydride (2H) complexes. Because the measured barriers are similar for ring-walk in the η2-benzene complex (2) and its conversion to the phenyl hydride complex (2H), this measurement was not able to determine if the ring-walking mechanism occurs only via an oxidative addition and reductive elimination sequence or if there is also a ring-slip mechanism in play. Additionally, the time scale of the NMR experiments is too long to capture key intermediates that may be only briefly sampled during the exchange process. Therefore, we used DFT calculations to explore intermediate and transition-state structures that connect the η2-benzene (2) and phenyl hydride (2H) complexes.

All stationary points were optimized with M0628 and M1129 functionals using the 6–31G**[LANL2DZ for W] basis set in Gaussian 16.30 These functionals were chosen because they provide accurate evaluation of the experimental isomerization energies and structures (see discussion below). Structures were confirmed as minima or transition states by vibrational frequency analysis. All transition-state structures have a single negative vibrational frequency. Rigid-rotor-harmonic-oscillator thermochemical corrections at 298 K and 1 atm were added using the default implementation in Gaussian 16. Optimizations and single-point calculations were performed using the SMD31 continuum solvent model for acetone, which provided an estimate of ΔGsolv that was added to gas-phase enthalpy and Gibbs free energy values.

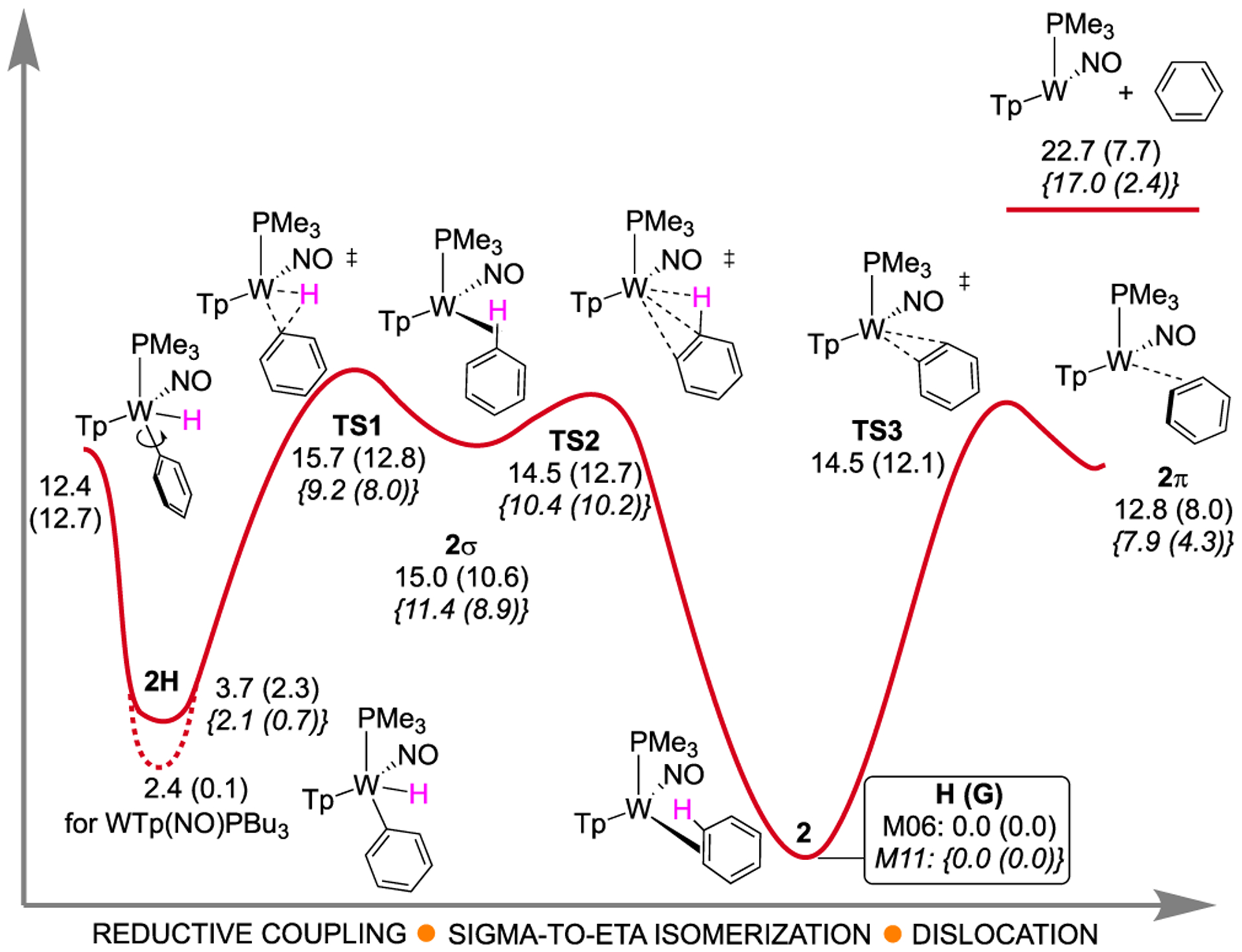

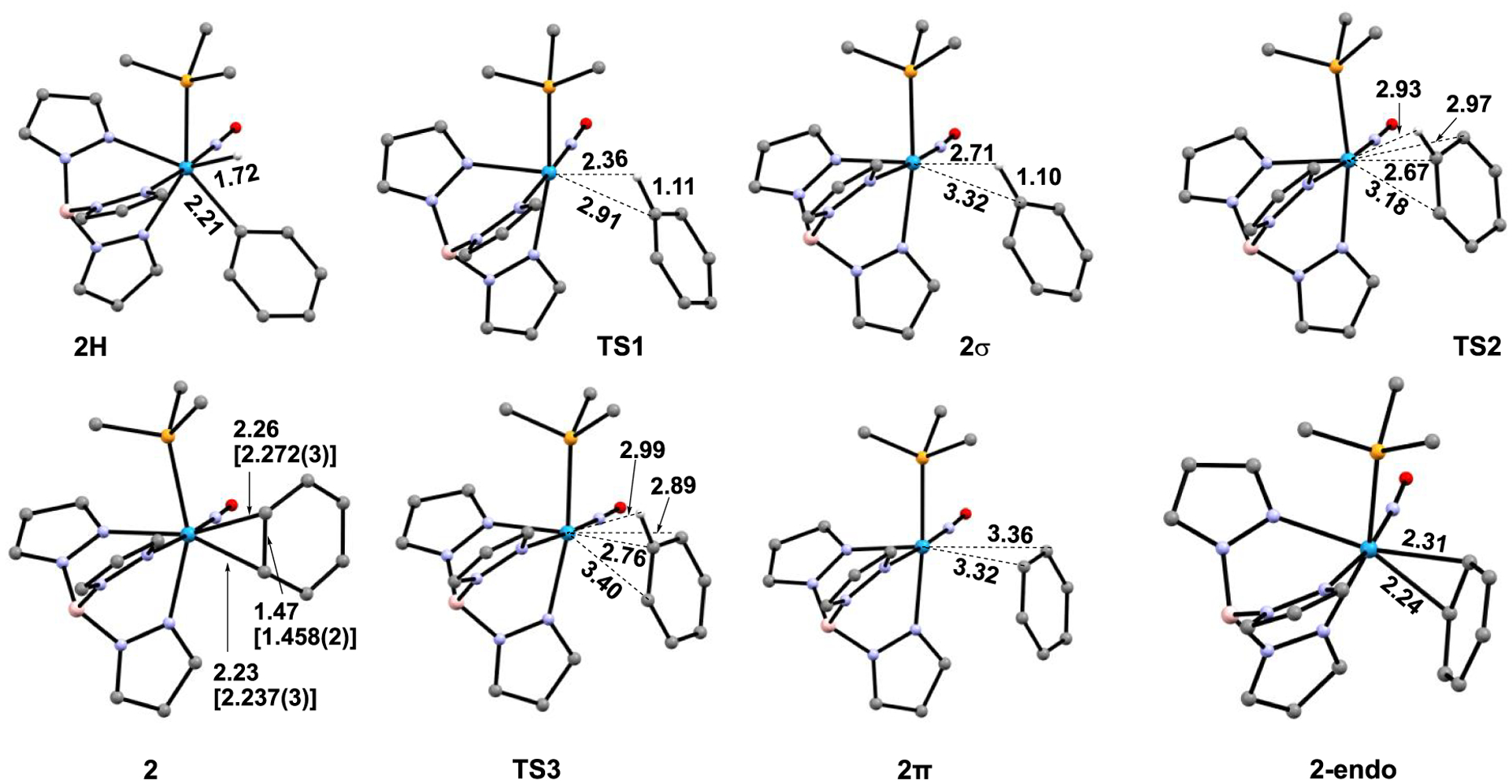

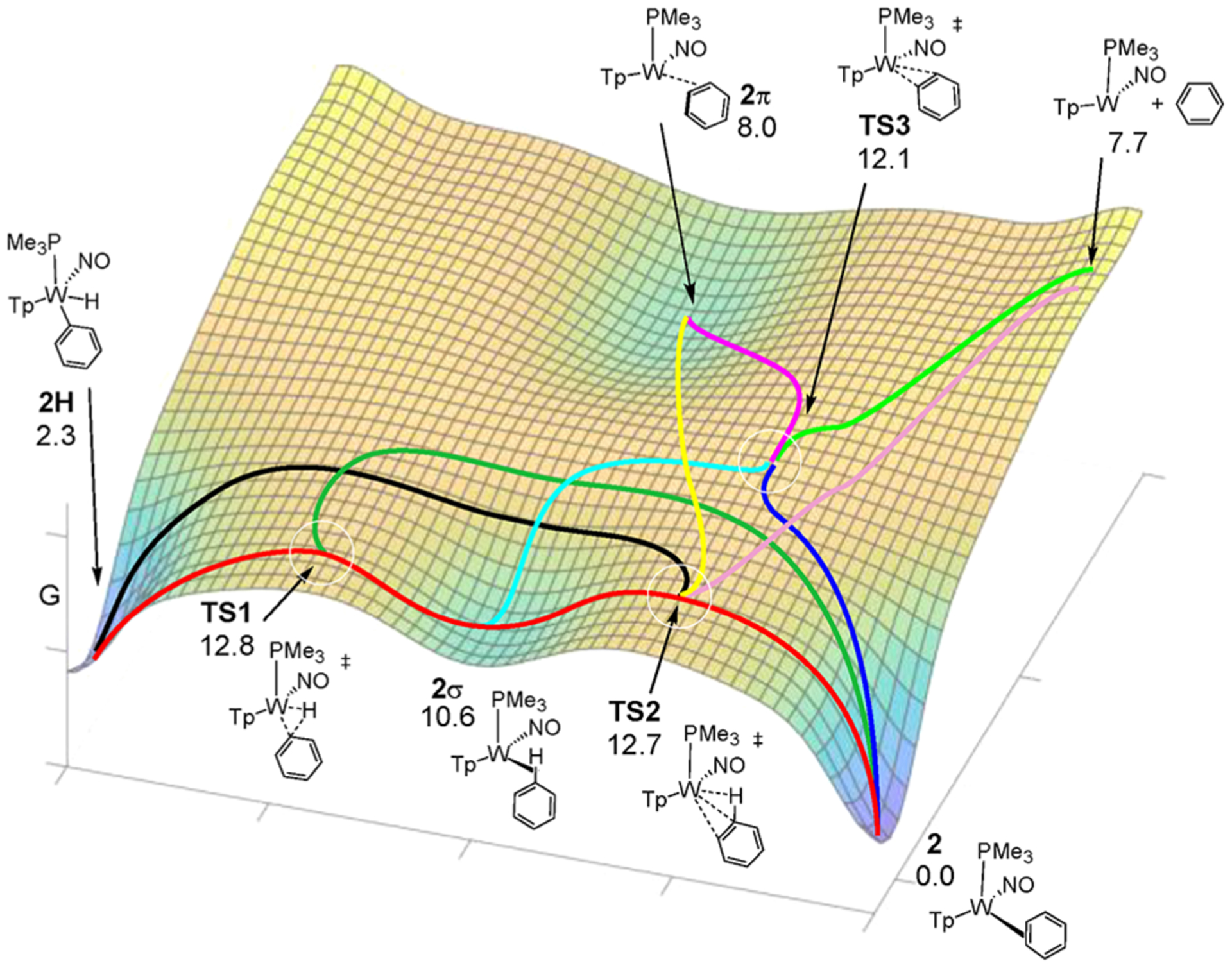

The static enthalpy and Gibbs energy landscape for WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene) in equilibrium with WTp(NO)(PMe3)(H)(Ph) is displayed in Figure 2. The 2 and 2H labels were used for PMe3 structures. A comparison of the M06 W–C bond lengths calculated for 2 with the SC-XRD-determined values for WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene)32 shows excellent agreement (within 0.01 Å; Figure 3). For M06, the ΔG value between 2 and 2H is 2.3 kcal/mol, which is within reasonable accuracy of the experimental value for a 10:1 ratio of benzene/hydride (=1.37 kcal/mol @ 25 °C). Use of a larger basis set, such as def2-TZVPD, changes this ΔG value by less than 0.5 kcal/mol (see the Supporting Informaton). The M11 functional gives an even closer ΔG value of 0.7 kcal/mol.

Figure 2.

M06/6–31G**[LANL2DZ] enthalpy and Gibbs (in parentheses) landscape for the isomerization of phenyl hydride to η2-benzene complex. M11/6–31G**[LANL2DZ] values are given in bracketed italics. The PBu3 groups of 2 and 2H were modeled as PMe3. Energies are reported in kcal/mol. Red: IRC connections for phenyl group rotation, reductive coupling, sigma to η2-arene isomerization, and partial benzene dislocation to 2π.

Figure 3.

M06-derived ground state, intermediate, and transition-state structures for WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene) to WTp(NO)(PMe3)(H)(Ph) isomerization. The PBu3 groups of 2 and 2H were modeled as PMe3. Distances reported in Å. Red = O; blue = N; orange = P; pink = B. Bracketed bond distances for structure 2 represent SC-XRD data (ref 32).

In order to test the validity of modeling the PBu3 system as the less complex PMe3 system, we also calculated the energy difference between WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-benzene) and WTp(NO)(PBu3)(H)(Ph) for comparison. For M06, ΔH and ΔG are 2.4 and 0.1 kcal/mol respectively, which is extremely close to representing the ~1:1 ratio of 2:2H with PBu3. M11 is also close but slightly overestimates the stability of the phenyl complex with a ΔG value of −1.4 kcal/mol. From either set of calculations, the replacement of methyls for butyls stabilizes the aryl hydride both entropically and enthalpically (vide infra). While these structures and calculations are not represented in the text, they are available in the Supporting Information.

Regarding the phenyl hydride complex 2H shown in Figure 3, a second isomer is possible in which the hydride and phenyl groups are transposed. That isomer is roughly 6 kcal/mol higher in enthalpy, and its structure and associated transition states are summarized in the Supporting Information but not considered further. Similarly, we located the conformational isomer to 2, 2-endo, which is 4 kcal/mol higher in energy where the benzene ring projects over the Tp ligand rather than the NO group.

A reductive coupling transition state TS1 was located with a M06 enthalpy barrier of 12.0 kcal/mol and a Gibbs free energy barrier of 10.5 kcal/mol, relative to 2H. As expected, this transition state features lengthened W-Ph (2.91 Å) and W–H (2.36 Å) bonds along with simultaneous, but very advanced (i.e., geometrically “late”), formation of the C–H bond (1.11 Å) (Figure 3). IRC calculations indicate that TS1 connects 2H to the intermediate 2σ, which is a C–H σ-complex. TS1 and 2H are geometrically very similar. Furthermore, the energy surface surrounding TS1 and 2σ is extremely flat. 2σ is <1 kcal/mol lower in enthalpy and ~2 kcal/mol lower in Gibbs energy than TS1. In addition, surrounding 2σ, we located transition state TS2 with a negative vibrational frequency of −70 cm−1, and IRC calculations suggest connection with the η2-benzene complex 2 through a rotational motion. TS2 has a Gibbs barrier of only 2.1 kcal/mol relative to 2σ, and the enthalpy of TS2 is slightly lower than that of 2σ, indicating that the sigma complex is in a very shallow energy well.

Geometrically, relative to 2, TS2 shows greatly elongated W–C bonds (2.67 and 3.18 Å, cf. 2.23, 2.26 Å for 2), as well as a weak W–H interaction (2.93 Å) and virtually no change to the C–H bond (1.09 Å). Hence, the transition from 2σ to TS2 could be described as the benzene beginning to dissociate from the metal and rotating the ring to bring the subject C–H bond roughly parallel to the HOMO of the {WTp(NO)(PMe3)} fragment (i.e., parallel to the W–P bond axis).33 Because TS2 has a geometric character of benzene dissociation and arene rotation, there is the possibility of non-IRC connections through this transition state, which will be discussed later.

From 2, transition states TS1 and TS2 have M06 free energy barriers of 12.8 and 12.7 kcal/mol, respectively.34 Both of these barriers are close to the experimental range for the free energy barrier estimate (15 ± 2 kcal/mol at 44 °C), which provides confidence that this DFT method provides an accurate representation of the energy surface. While M11 gives a slightly more accurate value for the 2 and 2H energy difference with PMe3, it underestimates the TS1 and TS2 barriers by ~5 kcal/mol (see the Supporting Information). All other functionals examined did not have as good of a performance compared to M06 (see the Supporting Information). We note that TS2 and 2σ are several kcal/mol lower than full dissociation on the enthalpy surface, and experimentally, 2H and 2 interconvert many cycles without being displaced by acetone solvent (t1/2 = 4 min for 2 and 66 min for the PMe3 analogue at 25 °C).32 This comparison with experiment suggests that the Gibbs energy of separated benzene and {WTp(NO)(PMe3)} should probably not be compared with the Gibbs energy of TS2 and 2σ using standard approximations since the translational entropy is likely overestimated.35

We also located the transition state for the W-Ph bond rotation of 2H. The enthalpy and Gibbs barriers for this process from 2H are 8.7 and 10.4 kcal/mol, which are lower than those for TS1 which indicates rapid W-Ph rotation compared to reductive coupling. Hence, this sequence provides a mechanism for interfacial isomerization (face-flip), as well as a ring-walk (vide infra).

In addition to locating the stationary points connecting 2H and 2, we also searched for structures that could potentially describe direct benzene coordination/dissociation to/from {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}. With M06, we located transition state TS3 (Figure 2 and Figure 3), where the negative vibrational frequency of −106 cm−1 indicates motion directly to and from the W metal center. While IRC calculations confirm that in one direction TS3 connects to a η2-benzene complex, the opposite direction was not definitive due to an incomplete connection, even with extremely small step sizes, presumably due to the flatness of the energy surface for benzene dissociation. It is unlikely that TS3 connects to separated benzene and {WTp(NO)(PMe3)} because these species are ~8 kcal/mol higher in enthalpy than TS3. Also, in TS3 the benzene approaches the tungsten with the interacting C–C bond parallel to the W-NO axis, and this orientation is perpendicular the benzene orientation in 2.

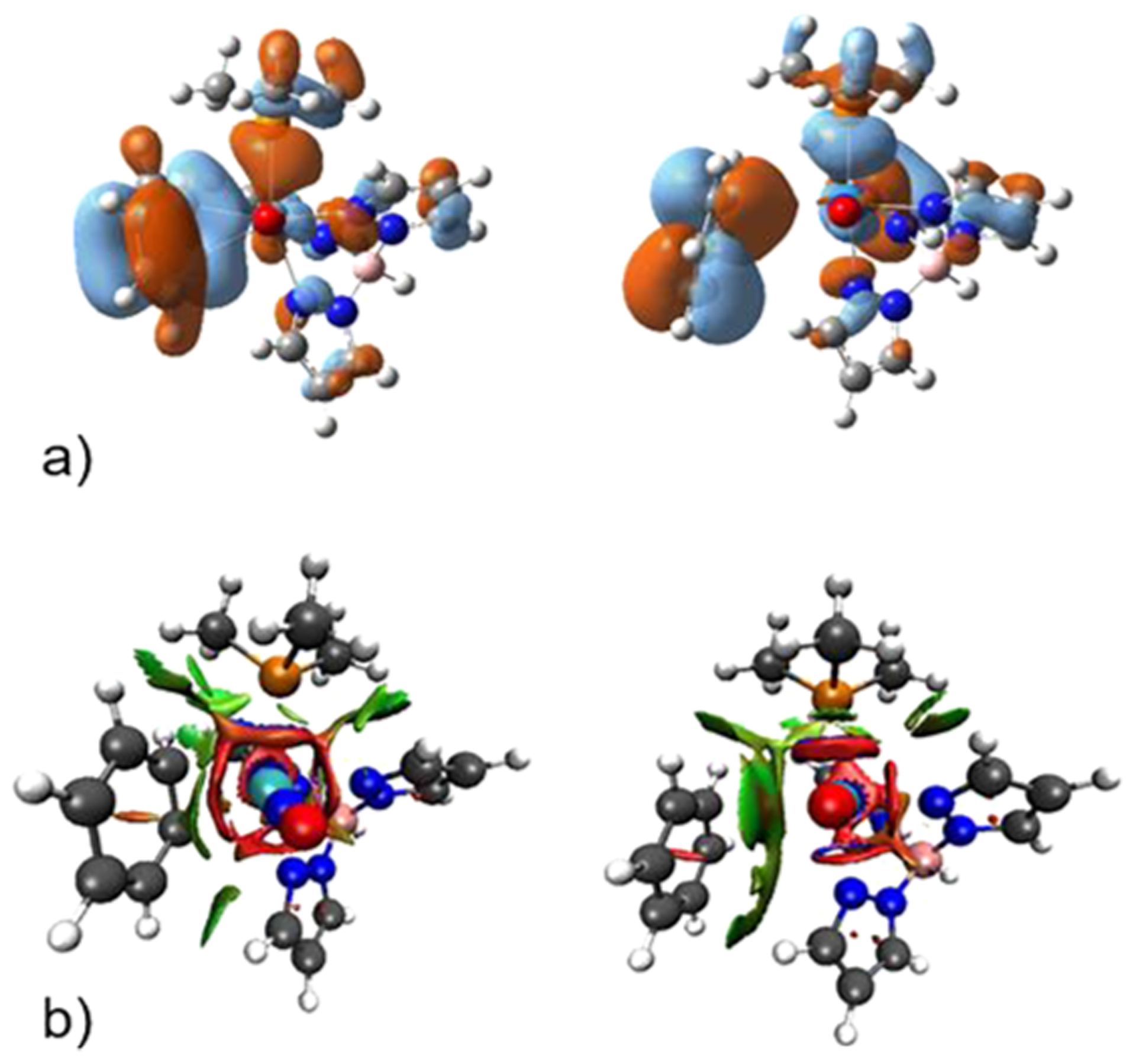

Because it is unlikely that TS3 connects to separated benzene and {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}, we searched for another possible WTp(NO)(PMe3)-benzene complex. This led to the location of the weak coordination complex 2π. In this complex, the W–C interaction distances are 3.32 and 3.36 Å (Figure 3), the C–C bond lengths within the aromatic ring are all roughly equal to the free aromatic (1.39 Å), and the C–C axis of the bound carbons, like TS3, is parallel to the W-NO axis. In contrast, for 2 the C–C axis is parallel to the W–P axis in order to maximize the backbonding interaction with the HOMO of {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}, i.e., the dπ-orbital that does not interact with the nitrosyl ligand. These features suggested to us that the η2-benzene complex 2 is a tight charge-transfer (orbital) interaction complex with bonding and backbonding interactions, while 2π is likely held together through dispersion interactions. We also confirmed that this structure can be located using DFT methods with an explicit dispersion term (see the Supporting Information). Figure 4a shows that only in the η2-arene complex is there significant frontier orbital overlap between benzene and the W metal center. Figure 4b compares the noncovalent interaction plots using NCIplot36 between these two complexes. This shows that the noncovalent interaction significantly increases as the W-benzene distance increases. An energy decomposition analysis using the absolutely localized molecular orbital (ALMO) method in Q-Chem confirmed that 2/3 of the W-benzene interaction in 2π is due to dispersion.37,38 In contrast, in 2 charge-transfer orbital interactions dominate the interaction stabilization (see Supporting Information for values).

Figure 4.

(a) M06-derived molecular orbitals (2: HOMO-3; 2π: HOMO-4) and (b) NCI plot comparisons of WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-benzene) (2) with the elongated WTp(NO)(PMe3)-benzene complex (2π).

Quasiclassical Direct Dynamics Simulations.

While the energy landscape connecting the phenyl hydride 2H with the η2-benzene 2 indicates that there is an intervening σ-complex intermediate (2σ) and a 2σ → 2 isomerization transition state (TS2, Figure 2), the flat shape of this surface suggests that there might be non-IRC motion and nonstatistical population of structures through the lack of internal vibrational energy redistribution (IVR). Also, IRC calculations were not definitive about the connection from 2 going through TS3, which is very close to TS2 in both energy and structure. Therefore, we carried out quasiclassical trajectory calculations with M06/6–31G**[LANL2DZ]. We also carried out trajectories with the M11 functional for comparison. M06/6–31G**[LANL2DZ] provides an accurate representation of the relative energies of structures compared with experiment. Trajectories were initialized and propagated in forward and reverse directions from all transition states using normal mode and thermal sampling that included zero-point energy at 273 K. Trajectories were propagated forward and reverse in mass-weighted Cartesian velocities with an approximate time step of 1 fs.

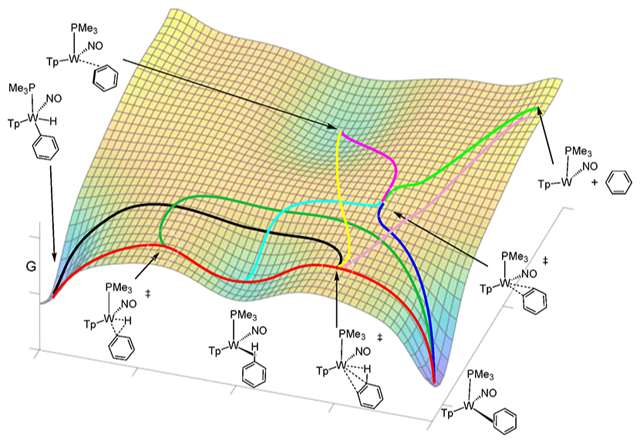

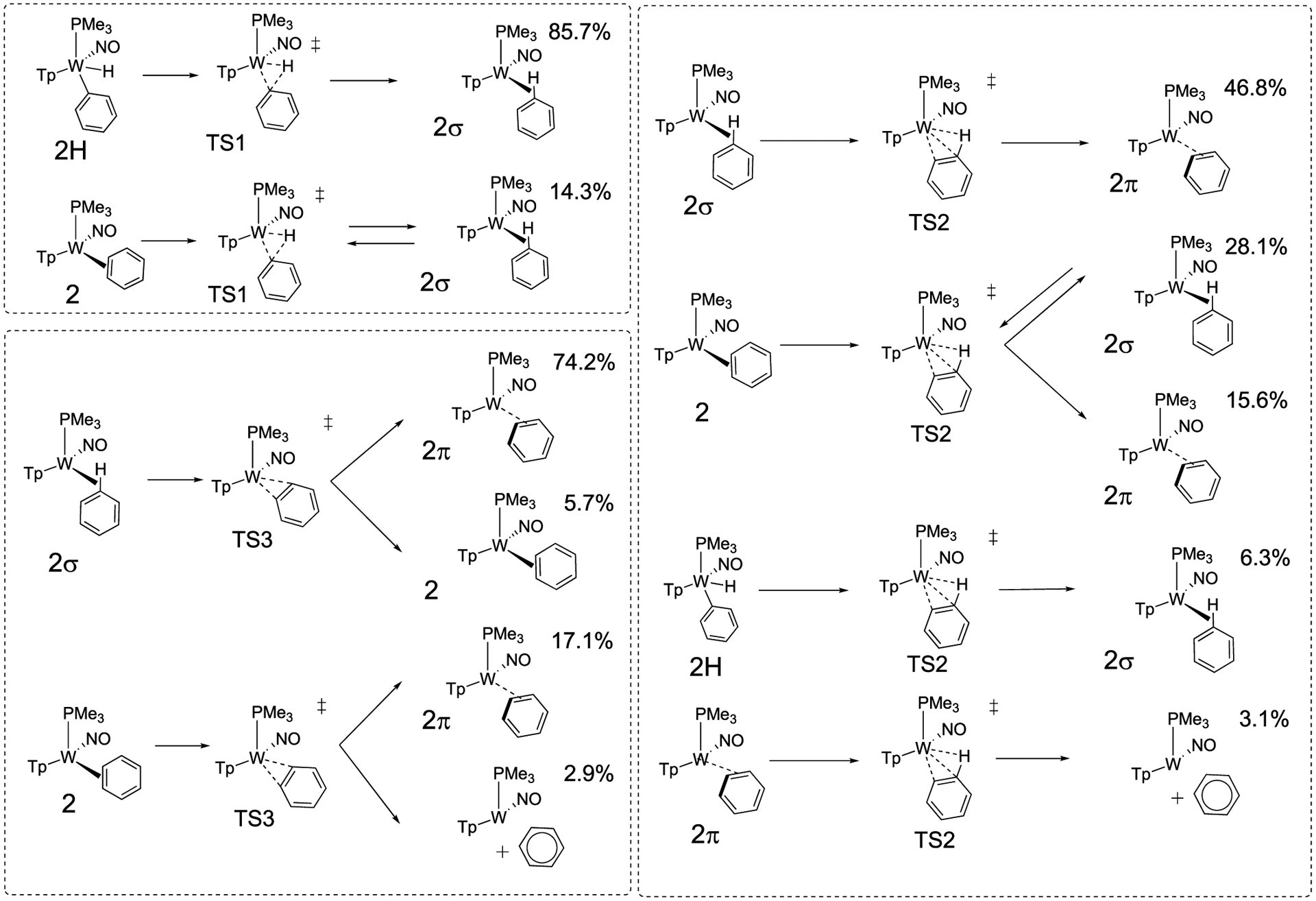

This trajectory analysis revealed several unexpected non-IRC connections where a transition state can lead to multiple products in each direction.39 The Supporting Information gives detailed categorization of all trajectories. Scheme 4 outlines all the unique reaction trajectories that proceed through TS1, TS2, and TS3 along with the relative percentage of each pathway that utilizes each of these transition states. Figure 5 offers a multidimensional model representation to visualize the network of pathways that the dynamics simulations reveal.

Scheme 4.

Outline of M06 Trajectory Connections to and Emanating from TS1, TS2, and TS3a

aPercentages are the relative amount of each pathway that utilize these transition states and do not include recrossing.

Figure 5.

Representation of the reaction coordinate network (Gibbs) connecting 2H, 2, 2σ, and 2π.

On the static energy surface shown in Figure 2, IRC calculations indicate that TS1 connects the phenyl hydride with 2σ. We propagated 42 M06 trajectories in the forward and reverse directions starting at TS1. Twenty-five trajectories connected energy minima passing through TS1 while 17 trajectories showed recrossing. In accord with this IRC perspective, all trajectories connect TS1 with 2σ. Eighty-six percent of all trajectories showed 2H → TS1 → 2σ connection (red path, Figure 5, Scheme 4). Recrossing trajectories were not considered in the relative percentages of reaction pathways reported in Scheme 4. With 24 additional M11 trajectories, we also found the majority of trajectories with this IRC connection (see the Supporting Information). For the direction of TS1 → 2H, we did not generally observe W-Ph bond rotation, and therefore this rotation is not coupled with the reductive coupling process. Unanticipated, approximately 14% of trajectories showed TS1 connecting the σ-complex (2σ) and the η2-benzene complex (2), without passing through TS2 (red and dark green paths, Figure 5). This demonstrates that the weak σ-complex, 2σ, and the energy surface surrounding it provide a pathway branching area for reductive coupling/oxidative cleavage and π-coordination. M11 trajectories also showed branching at 2σ but different than M06 trajectories ending at 2π rather than 2.

The static DFT surface (Figure 2) indicates that TS2 is slightly lower in energy than TS1. Therefore, during the 2H → 2 isomerization process 2σ will not only return to TS1 but will also achieve TS2. While on the static surface the IRC suggests that TS2 connects 2σ with 2, the energy surface surrounding TS2 is flat (orange-colored surface area in Figure 5), and dynamical effects are likely to impact pathways leading to and from TS2. Indeed, our 56 M06 trajectories revealed five unique reaction pathway connections that involve TS2, which are outlined in Scheme 4 and Figure 5. Importantly, the five connections shown in Scheme 4 include the first major connection for TS2: 2σ to 2π. Many of the structures arrived from TS2 evolved further. For example, some trajectories showed the ring alternating between a given 2σ and 2π (red and yellow paths) structure, while other trajectories evolved as a sequence of different 2σ and 2π structures such that multiple carbon and hydrogen atoms encounter the tungsten metal center (analogous to the ring-walk of the η2-arene 2). Similar to M06, 50 trajectories with M11 showed all the same major dynamical pathways with TS2, although not in the same quantitative ratio due to the limited number of trajectories possible to propagate with a very large system (see the Supporting Information).

Unexpectedly, the major reaction pathway that accounts for ~50% of the trajectories for TS2 involves the non-IRC conversion of 2σ to 2π (red and yellow paths, Figure 5) rather than the η2-arene 2. This dynamical connection is reasonable considering the geometry of TS2. As stated previously, while the negative vibrational frequency of TS2 shows mostly rotation of the arene, the W–C distances are very long and potentially closer to 2π than 2. While the most important result is the general pathway branching identified through TS2, and these results were modeled in continuum solvent, it is possible that modeling with explicit solvent might alter the percentage of branching toward 2 versus 2π, and the percentages through TS2 should be interpreted qualitatively. This interpretation is especially important due to the limited number of trajectories that are able to be examined with this very large system. However, it is not obvious if explicit solvent would diminish or enhance directing trajectories from TS2 toward 2π, especially because the timing of solvent translation is significantly longer than the 500–750 fs time scale of traversing through the TS2 zone.

The next significant trajectory pathway for TS2 accounts for >25% of trajectories and is the IRC-identified 2σ → 2 pathway. This pathway along with its microscopic reverse provides a mechanism for an intrafacial ring-walk isomerization (ring-slip) that does not require C–H cleavage. Roughly similar in magnitude, ~15% of the trajectories connected 2 → TS2 → 2π. This connection is outlined in Figure 5 with a red path from 2 to TS2 and then yellow from TS2 to 2π. This connection of 2π with 2 is perhaps not surprising since the W-πCC* interaction in 2 is significantly stronger than the W-σCH* interaction in 2σ.

Two other pathways account for ~10% of the trajectory connections. The small amount of these trajectories should be cautiously interpreted, especially since trajectories were not found with the M11 functional. These two trajectory pathways include 2H → TS2 → 2σ (black and red, Figure 5) and 2π → TS2 → [{WTp(NO)(PMe3)} + benzene] (yellow and dusty rose paths, Figure 5). This latter reaction pathway leading to benzene dissociation was unexpected and, similar to connections to 2π, might be significantly influenced by explicit solvation spheres. Again we note, however, that the experimental rate of benzene ring-walking (seconds time scale) is much faster than for benzene displacement by either benzene-d6 or acetone-d6 (hours time scale).

The static DFT surface indicates that when the η2-benzene complex 2 is formed there is a nearly equal barrier for going toward TS2 (red path, Figure 5) as there is to achieve TS3 (dark blue path, Figure 5). This suggests that during the isomerization process TS3 will also be sampled. We propagated 52 M06 trajectories through TS3. Thirty-five trajectories showed forward and reverse connections while 17 showed recrossing. Perhaps unexpected, for the fully connected reactive trajectories, the major pathway shown for TS3 in Scheme 4 is 2σ → TS3 → 2π (light blue and magenta paths, Figure 5), which accounts for nearly 75% of all connections. Only 17% of the trajectories connect the η2-benzene complex 2 with 2π through TS3 (dark blue and magenta). This indicates that TS3 should perhaps not be interpreted as a direct π-coordination transition state but rather a general coordination transition state where collisions can lead to either σ- (light blue path, Figure 5) or π- (dark blue path, Figure 5) type coordination. Also important, similar to trajectories for TS2, trajectories from TS3 moved through other intermediates after arriving at either 2σ or 2π and occasionally continued on to 2 or 2H.

Overall, the static DFT calculations suggest that during the isomerization process there is access to TS1, TS2, TS3, and possibly other intermediates and transition states, all roughly 4 kcal/mol below complete dissociation. The dynamics trajectories further revealed that all of these transition states provide a complex network for interconversion of 2H with 2σ, 2, and 2π, as illustrated in Figure 5. Significantly, the direct connection between 2H and dissociation (either via TS2 or TS1 and TS3) indicates by the principle of microscopic reversibility that η2-coordination is not necessary for insertion into the C–H bond.25 Finally, we note that while these calculations indicate pathways for ring-walking that do not require C–H oxidative addition (i.e., a ring-slip), the same is not true for face-flipping, which appears to require C–H scission followed by rotation of the phenyl-W bond.

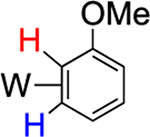

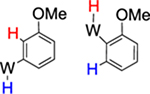

Substituent Effects.

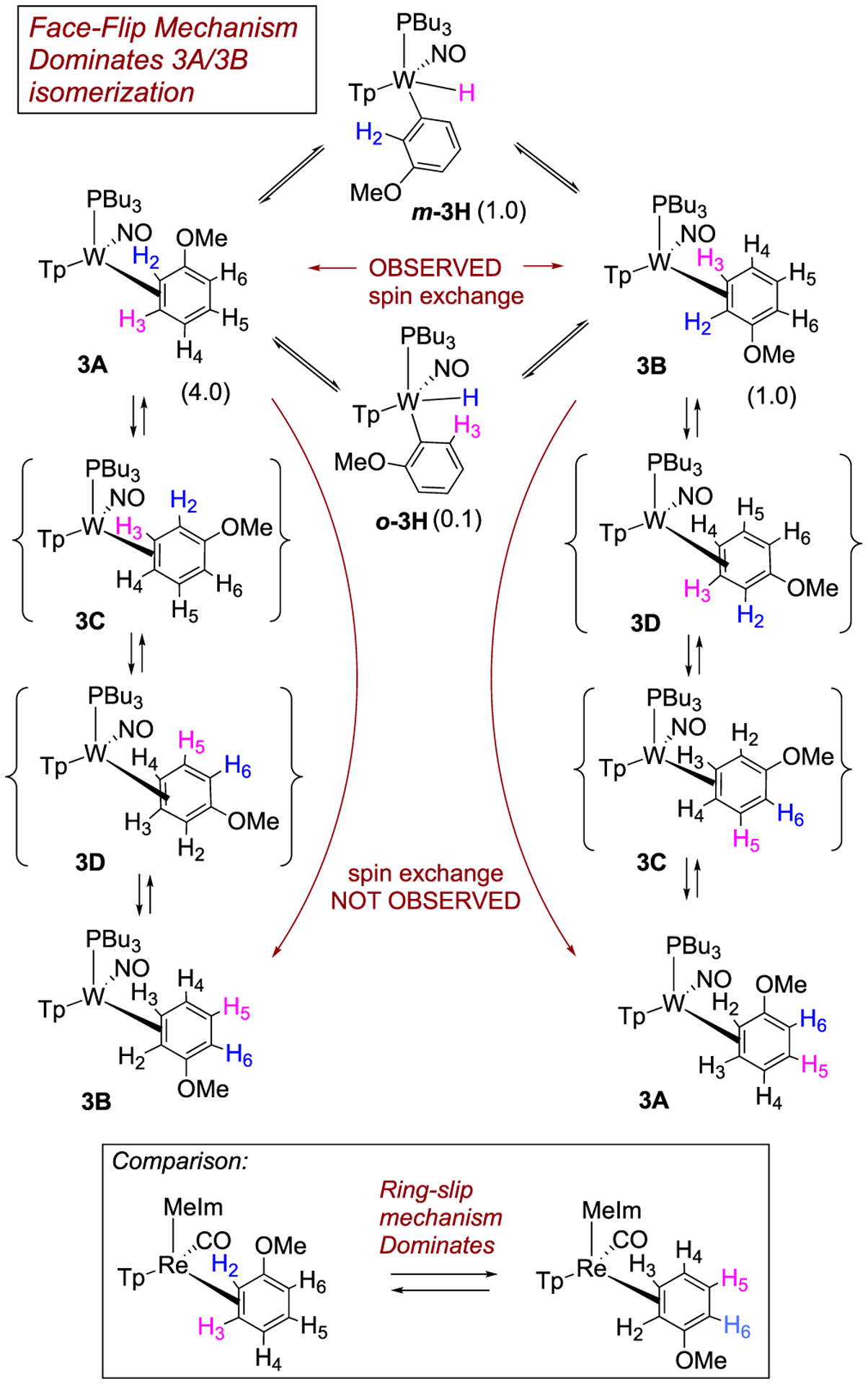

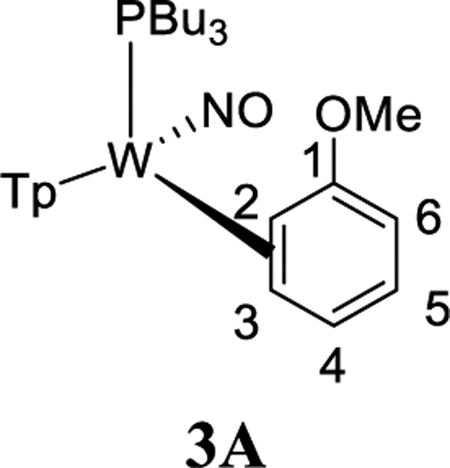

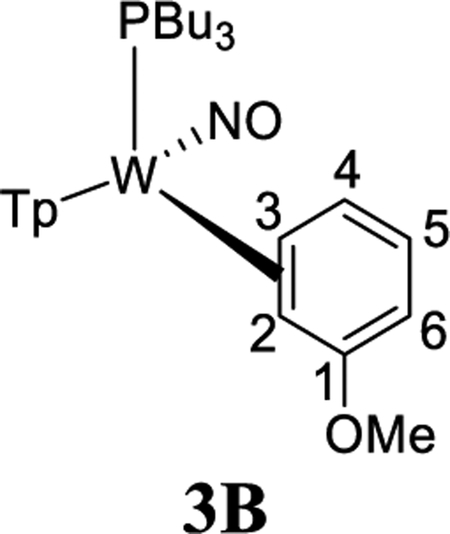

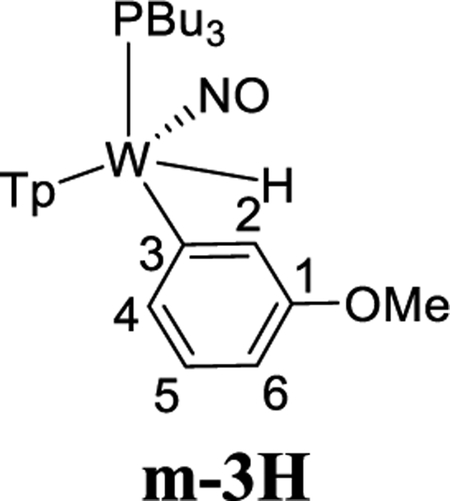

We next set out to determine how a substituent on the benzene ring affects the η2-benzene/phenyl hydride equilibrium, as well as how it affects the regioselectivity of these species. We began by examining the role of a π-donor group (OMe). Reduction of 1 with sodium dispersion in neat anisole led to the formation of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(anisole) (3), isolated as a 4:1:1 mixture of two η2-arene complexes 3A (4) and 3B (1), along with an aryl hydride species m-3H (1) (Scheme 5). We note selective oxidative addition at the meta position is in contrast to what is typically observed for anisole.40 Close examination reveals a minor amount of a second hydride complex (0.1) that we tentatively assign as o-3H (0.1), based on its chemical exchange with 3A and 3B (vide infra). Parenthetically, the anisole complex 3 can be prepared on a 15 g scale at 50% yield, a value comparable to that of the {WTp(NO)(PMe3)} analogue.27 This complex is stable for months while stored as a solid at low temperatures (−30 °C). The substitution half-life of 3 at 25 °C is ~20 min, making it a suitable synthon for {WTp(NO)(PBu3)}, especially in cases where a potential ligand is incompatible with the reducing capability of sodium.

Scheme 5.

Interconversion of 3A and 3B Occurs through C–H Insertion for Anisole Complex 3a

aBlue- and pink-colored hydrogens indicate observed or expected spin-saturation exchange for each mechanism.

NOESY data for an acetone solution of 3 indicate chemical exchange between all four anisole complex isomers in solution (3A, 3B, o-3H, m-3H; Scheme 5). Significantly, the only exchange observed between meta protons of the various isomers is H3 of 3A with H3 of 3B and the hydride of m-3H. Likewise, H2 of 3A exchanges with H2 of 3B and the weak hydride signal of o-3H. However, there is no exchange between the ortho proton H2 in 3A and the ortho proton H6 in either 3A or 3B, nor do the hydride signals exchange with H4 of either 3A or 3B. Although signals for the minor species o-3H are far too weak to fully characterize it, based on the chemical exchange of the hydride signal, we can confidently rule out this compound being the para hydride (p-3H).

These observations above indicate that for the η2-anisole diastereomers, the interconversion of 3A and 3B occurs via a face-flip (interfacial) isomerization, which must be significantly faster than a purported ring-slip (intrafacial isomerization). This is in contrast to that observed for the complex ReTp(CO)(MeIm)(η2-anisole) (MeIm = N-methylimidazole), which undergoes intrafacial isomerization (ring-slip) roughly four times faster than interfacial isomerization (face-flip; Scheme 5).41

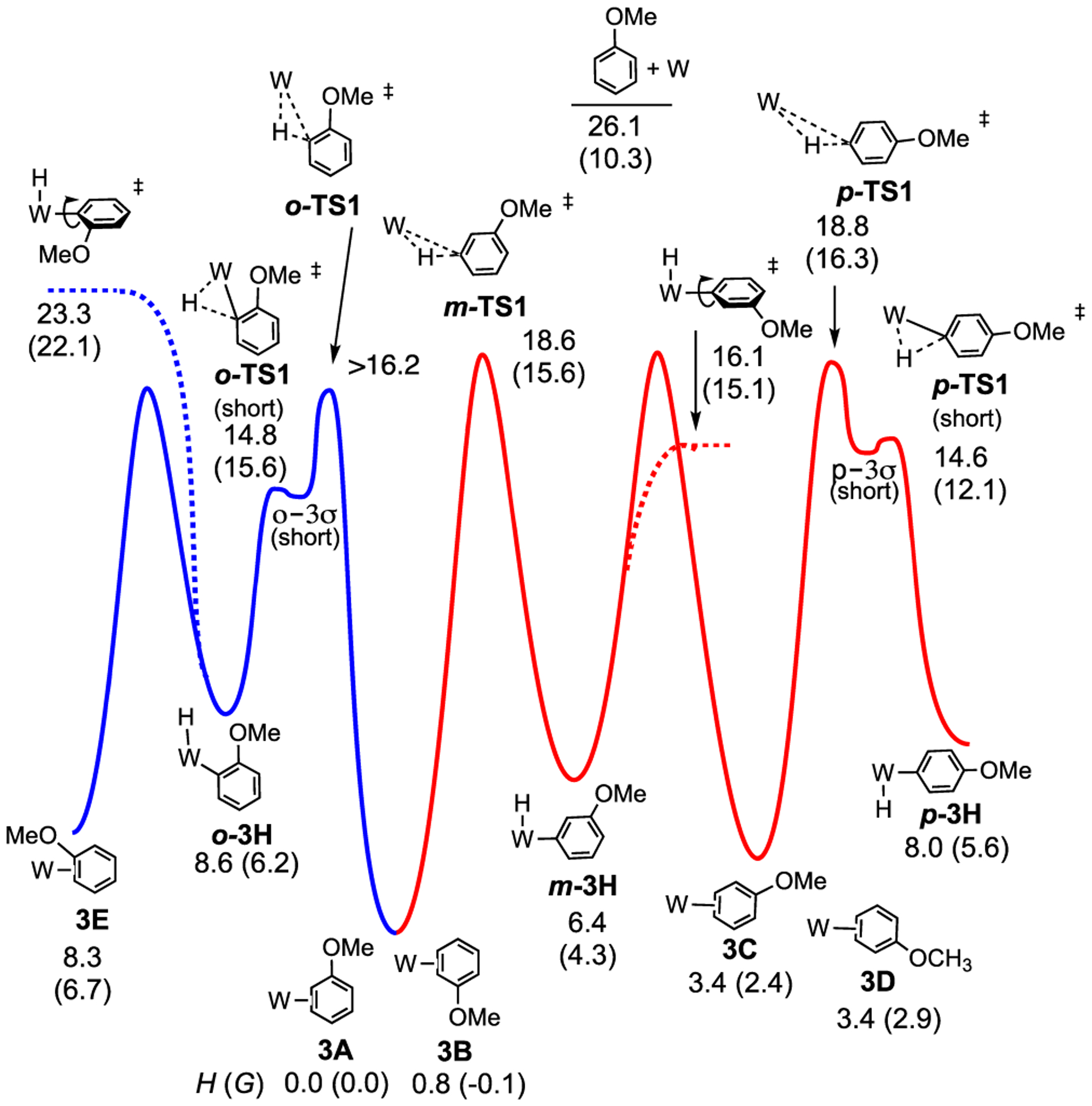

Possible mechanisms for both face-flip and ring-walk isomerization for the anisole complex were examined with DFT, and an abbreviated energy surface with π- and W–H complexes is shown in Figure 6. Consistent with experiment, the meta aryl hydride m-3H is 1.9 kcal/mol lower in Gibbs free energy than the ortho counterpart o-3H. However, as with benzene (2; Figure 2), both species are calculated (using PMe3) to be significantly higher in Gibbs free energy than the dominant 2,3-η2 isomers (3A and 3B; Figure 6). Another important comparison to experiment is that the M06 calculations show 3A and 3B to have nearly identical Gibbs energy values and 3B to be only 0.8 kcal/mol endothermic relative to 3A. Both of these values are consistent with the 4:1 ratio of 3A:3B found experimentally.

Figure 6.

M06-calculated structures and abbreviated reaction coordinate profile for an interfacial for anisole complex isomers. W = {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}; (kcal/mol). The energy of o-TS1 is estimated to be greater than the energy of o-3σ (long) = 16.3 kcal/mol (not shown).

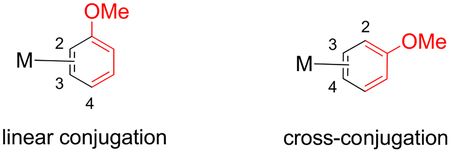

Calculations indicate that the 3,4-η2 isomers (3C, 3D) are 4–6 kcal/mol less stable (based on Gibbs energies; 4–6 kcal/mol more endothermic) than the 2,3-η2 counterparts (3A, 3B). There are two explanations for the difference in ground energies of 3A/3B compared to 3C/3D. First, metal coordination partially dearomatizes the system, leaving a 1,3-diene system. For 3A/3B, the OMe group is in linear conjugation while in 3C/3D the OMe group is in cross-conjugation (see the uncoordinated portion in red below).42 This notion is supported in the calculated C–O bond lengths for 3A (1.360 Å) and 3B (1.358 Å), which are shorter than for 3C (1.364 Å) and 3D (1.364 Å). For comparison, a SC-XRD study of 3A shows a C–O bond length of 1.336 Å (Supporting Information); cf. free anisole: 1.373 Å (SC-XRD)).43 Additionally, DFT analysis of 1-methoxycyclohexa-1,3-diene versus 2-methoxycyclohexa-1,3-diene shows an enthalpy difference of 2.5 kcal/mol. A second explanation is that the anisole π to W-dσ donor interaction is enhanced at the ortho position compared to the para position, which is consistent with the nodal properties of the occupied anisole π-orbitals (see the Supporting Information).44 The difference in orbital, charge-transfer interactions was confirmed using the ALMO method.

The blue pathway in Figure 6 shows that for 3A the oxidative cleavage transition state, o-TS1, has a Gibbs barrier of 12.7 kcal/mol and results in the W–H o-3H. The σ-complex intermediates (o-3σ, m-3σ, p-3σ), and σ to π transition states (o-TS2, m-TS2, p-TS2) are not shown on this energy surface. From o-3H it could be possible for W-aryl bond rotation followed by reductive coupling to lead to 3B, which constitutes a face-flip mechanism. However, due to the congestion of the aryl OMe group, the Gibbs barrier for rotation (shown as dotted lines) is 22.1 kcal/mol. Instead, the red pathway in Figure 6 through either complete or partial ring-walking provides a lower energy route for conversion, shown as beginning with 3B. From 3B there is a meta oxidative cleavage transition state, m-TS1, with a Gibbs barrier of 15.6 kcal/mol. This is similar to o-TS1 but lower than the rotation barrier in the blue pathway. The m-TS1 is higher than TS1 of the benzene complex, which is consistent with higher barriers and slower isomerization for trifluorotoluene (vida infra).

Interestingly, for both the ortho and para hydrides (o-3H, p-3H), the first transition state (o-TS1-short and p-TS1-short) varied considerably from the TS1 of benzene (Figure 6), and in the case of para, this transition state leads to a corresponding “short” sigma complex (p-3σ-short). A second transition state (p-TS1) and sigma complex (p-3σ) were also located, which more closely resembled those of benzene (TS1 and 2σ). For o-TS1-short and p-TS1-short the C–H insertion is significantly more developed than in the more loosely bound TS1 transition states, with longer C–H bonds (o-TS1: 1.31 Å; p-TS1: 1.28 Å) and shorter W–C bonds (o-TS1: 2.27 Å; p-TS1: 2.27 Å) compared to their benzene counterpart (TS1: C–H = 1.11 Å and W–C = 2.91 Å). We speculate that a sigma complex similar to p-3σ-short likely exists for the ortho hydride as well (o-3σ-short), but this was not located. These “short” sigma complexes and accompanying transition states were not located for the meta hydride, which evolved directly into m-TS1 (C–H = 1.11 Å and W–C = 2.83 Å) and m-3σ. Apparently, the π-donating property of the methoxy group provides the extra electron density in the ortho and para C–H bonds to stabilize the more conventional tightly bound sigma complexes, which then evolve into their loosely bound counterparts (o-3σ, p-3σ; Figure 6). See the Supporting Infomation for a more in-depth discussion on anisole transition states and σ-complexes.

Importantly, from m-3H there is the possibility of either continued ring-walking around the ring through oxidative cleavage/reductive coupling or W-aryl bond rotation, either of which would eventually lead to 3A. At m-3H the W-aryl bond rotation barrier is only 15.1 kcal/mol. We note that the relative energy of p-3H compared to those of o-3H and m-3H suggests that it should be a minor species and observed in a similar quantity to o-3H. However, experiments did not detect p-3H. While this might indicate that the traversing through 3C, 3D, p-TS1, and p-3H (i.e., a complete ring-walk) does not occur as rapidly as the face-flip mechanism, none of the transition-state barriers are sufficiently high to prohibit equilibration of all three aryl hydrides with their η2-arene counterparts at ambient temperature.

Interestingly, we found in the case of the anisole complex 3 that the ratio of 3 to 3H can be modulated by choice of solvent. Table S10 in the Supporting Information summarizes these results, where we find that the use of MeOH enhances the amount of dihaptocoordinate arene at equilibrium to 23:1. We speculate that hydrogen-bonding interactions with the basic NO ligand45 could result in an overall decrease in the electron density of the metal, and this could disfavor the formation of the oxidative addition process.

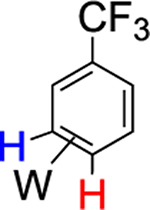

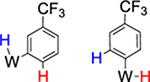

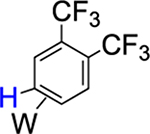

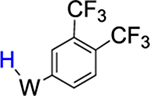

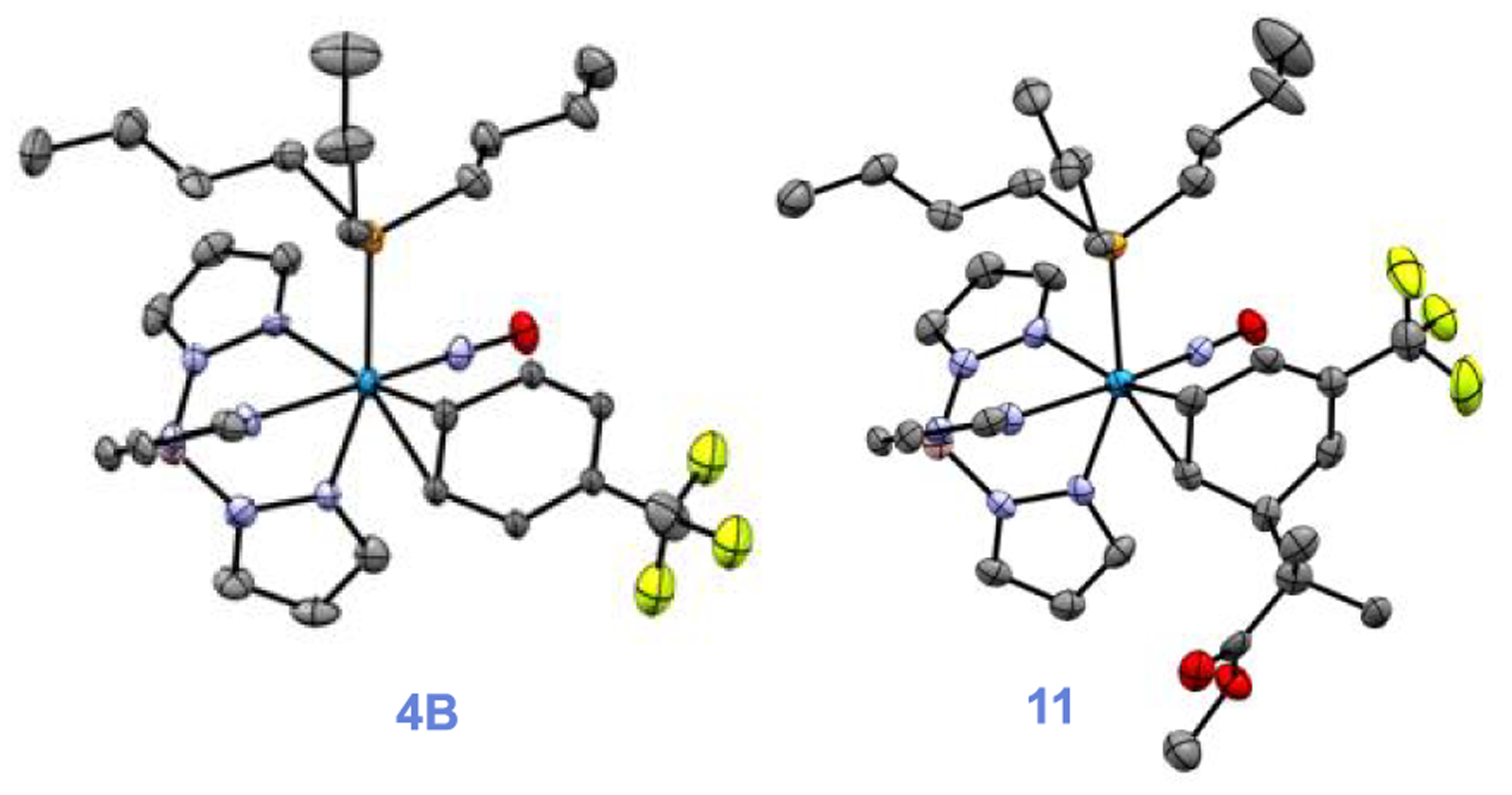

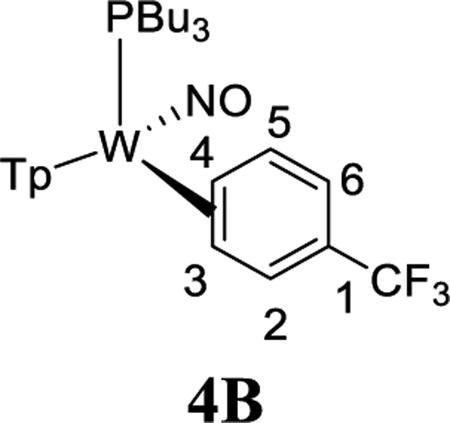

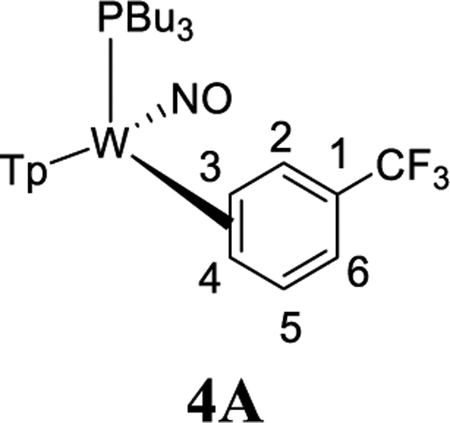

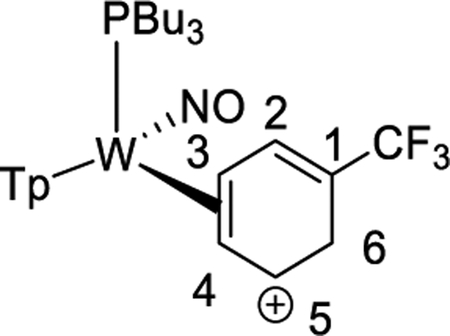

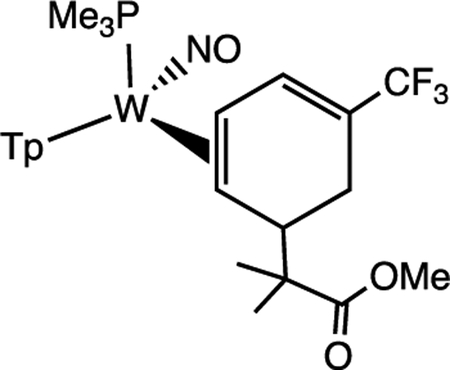

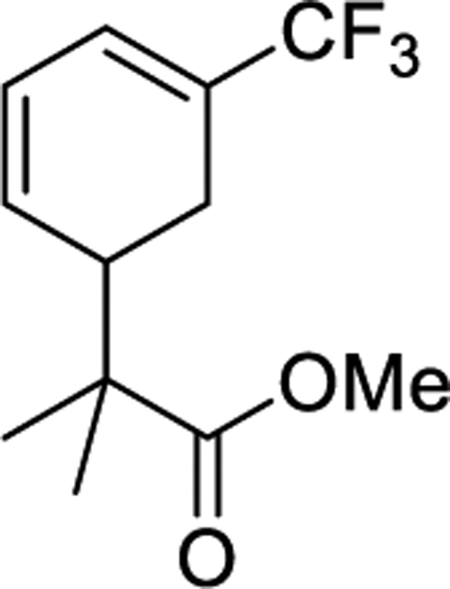

To study the effects of an electron-withdrawing substituent, we set out to prepare a complex of α,α,α-trifluorotoluene, using anisole complex 3 as a synthon for {WTp(NO)(PBu3)}. Crystals of the trifluorotoluene complex (4) suitable for X-ray diffraction were prepared from a DCM/hexanes (1:10) solution of 4 at −30 °C. A molecular structure determination reveals that in the solid state both 4A and 4B are present. An ORTEP diagram of the higher population species (81:19) is provided in the Supporting Information.

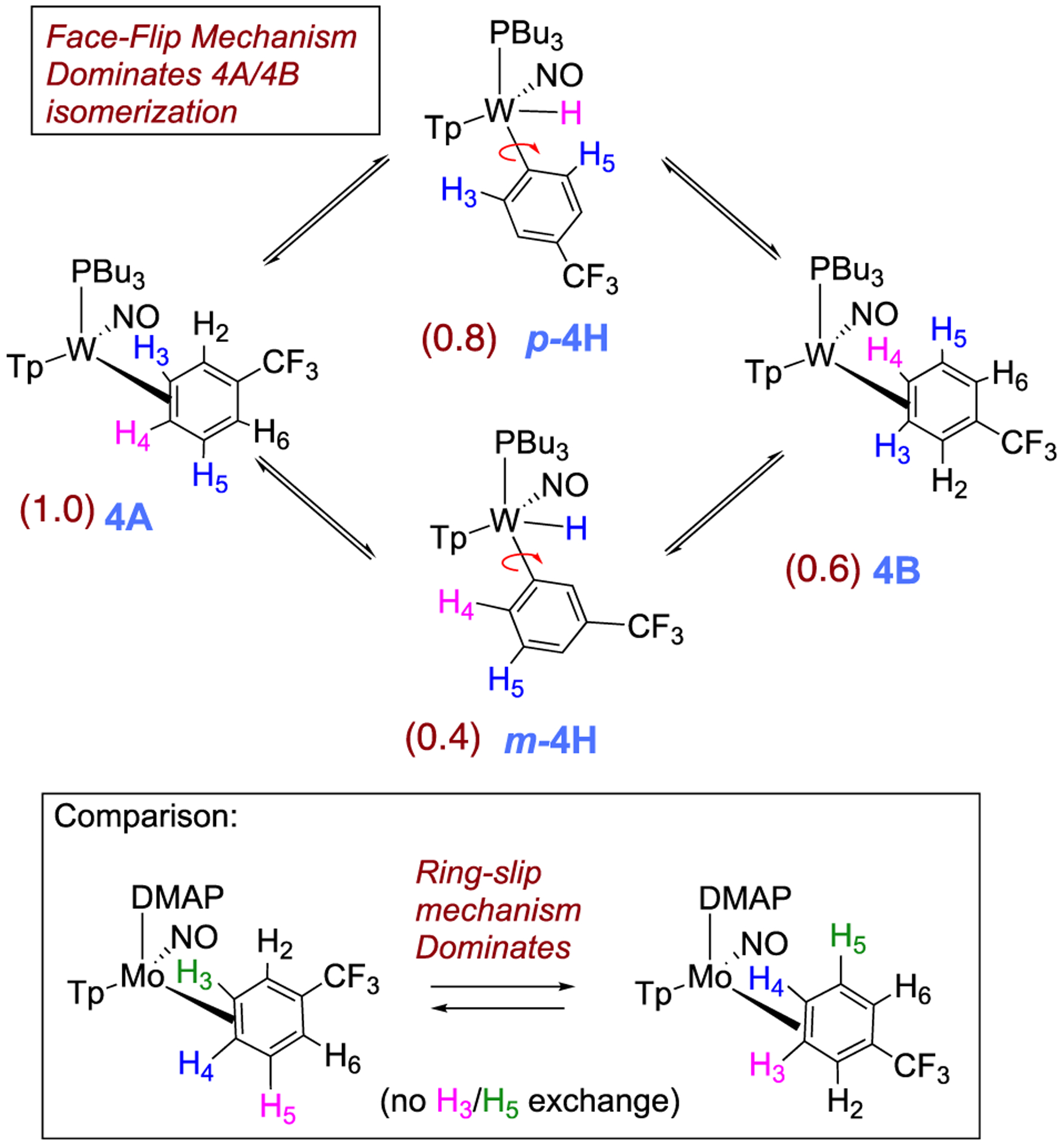

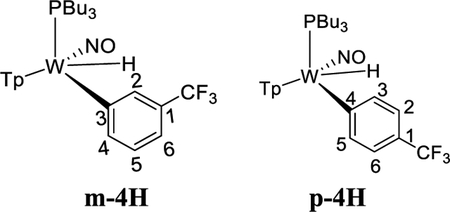

1H NMR analysis of the trifluorotoluene complex 4 reveals the presence of two η2-arene complexes (4A (1.0) and 4B (0.6)) along with two aryl hydrides (m-4H (0.4) and p-4H (0.8)). The 1:0.6 ratio of 4A and 4B is comparable to that of the PMe3 analogue.27 Interestingly, while exchanges on the time scale of the NOESY experiment were observed between the η2-arene and aryl hydride complexes for 2 and 3, no such exchange was observed for 4 at 25 °C. However, at 50 °C chemical exchange was observed between the para protons (H4) of 4A and 4B and the hydride for p-4H. Also, exchange occurred between the two meta protons (H3 and H5) of 4A and 4B and the hydride of m-4H (Scheme 6). Given that the η2-arene/aryl hydride equilibrium constant is close to unity for all three arene systems 2–4, the better π-accepting abilities of the electron-deficient CF3Ph appear to slow both the rate of oxidative addition and that of reductive elimination. In other words, the CF3 group not only stabilizes the η2-arene isomer, making the transition state energy to the aryl hydride larger, but also must stabilize the aryl hydride relative to this transition state in order to keep the arene/aryl hydride equilibrium constant for 4 close to unity. Consistent with this idea, we calculated the energy effect of the CF3 group on π-coordination and stabilization of the aryl hydride: 4A + benzene → 2 + trifluorotoluene, ΔH = 4.1 kcal/mol and ΔG = 3.5 kcal/mol; also, 4H + benzene → 2H + trifluorotoluene, ΔH = 2.2 kcal/mol and ΔG = 1.9 kcal/mol. These calculated exchange reactions support the idea that both the η2-arene and aryl hydride isomers are stabilized by the CF3 group. Our calculations suggest that the origin of the slower isomerization is mainly this ground-state stabilization because o-TS1-CF3+benzene → TS1 + trifluorotoluene is exothermic and exergonic with ΔH = −0.4 kcal/mol and ΔG = −1.3 kcal/mol.

Scheme 6.

Interfacial (Face-Flip) Isomerization for the Trifluorotoluene Complex (4A to 4B) Involving Two Different Aryl Hydride Intermediates (m-4H, p-4H)a

aValues in parentheses are equilibrium ratios in benzene-d6 at 25 °C.

The spin-transfer exchange observed with the trifluorotoluene system 4 is also consistent with an interfacial isomerization (“face-flip”) mechanism operating through an aryl hydride intermediate. In contrast, the previously reported MoTp(DMAP)(NO)(η2-3,4-trifluorotoluene) complex (DMAP = 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine) is able to interconvert between the analogous coordination diastereomers predominantly through an intrafacial mechanism (ring-slip) that is operative at ambient temperatures.46 We speculate that this difference in the predominant isomerization pathway between the Group 6 congeners is due to the more π-basic nature of the tungsten fragment. The further stabilization of the ground state for the tungsten system raises the barrier for the purported η2-arene → sigma-complex transition state that is likely on the path to ring-walk (see Scheme 6). For both the molybdenum and rhenium systems mentioned above, any purported C–H insertion would likely result in a face-flip isomerization, which is not observed in the corresponding NOESY data.41,46 Thus, C–H insertion is significantly slower than the ring-walk for both the Mo and Re complexes.

The temperature dependence of the C–H insertion process at the meta carbon was determined for a sample of 4 in acetonitrile-d3 solution over a temperature range of 20–55 °C. A van ‘t Hoff plot (Supporting Information) shows that the reductive elimination (m-4H → 4) is exothermic, with a ΔH° = −2.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol and ΔS° = −9.0 ± 0.6 eu. These values are in good agreement with those obtained for the naphthyl hydride to naphthalene conversion on {RhCp*(PMe3)} (cf. −4.1 kcal/mol, −12 eu),22 as well as that calculated for m-4H to 4A (−5.6 kcal/mol) and 2H to 2 (ΔH° = −4.0 kcal/mol).

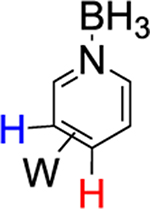

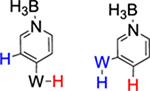

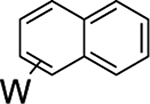

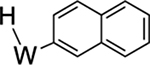

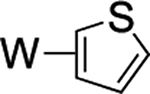

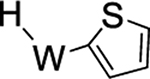

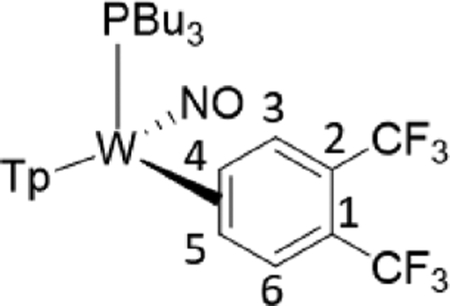

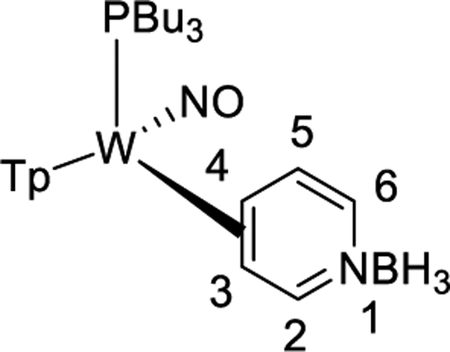

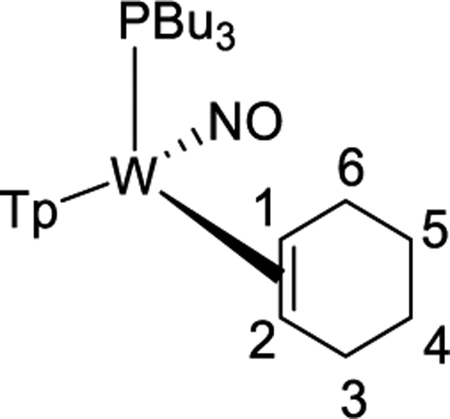

Beyond the complexes of benzene (2), anisole (3), and trifluorotoluene (4) already discussed, we surveyed o-hexafluoroxylene (5), pyridine-borane (6), naphthalene (7), thiophene (8), and cyclohexene (9). For the o-hexafluoroxylene benzene complex 5, while initially no C–H activated product was observed, over 5 days in benzene-d6 a new complex is formed in a 1:20 (5H:5) ratio that has resonances consistent with C–H activation (notably a new set of Tp4 protons at 5.76, 5.70, and 5.31 ppm) along with a resonance at 9.30 ppm with JPH = 98 Hz and JWP = 31 Hz) that grows in over time. Analogous to 4, the aryl hydride and η2-arene forms of 5 do not undergo spin-saturation exchange at ambient temperature, and no fluctional behavior was observed even when heating the reaction mixture to 50 °C. Thus, while substituents on the benzene ring have little impact on the arene/aryl hydride equilibrium, they can have a major impact on the kinetics of C–H activation, ranging from seconds (benzene) to hours (o-hexafluoroxylene) at ambient temperatures. For 7–9, no C–H activated isomer was observed, even upon heating (50 °C) or over extended time (18 d).

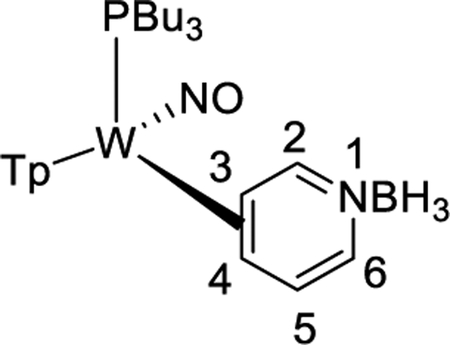

We briefly explored different classes of aromatic molecules to determine to what extent the η2-aromatic/aryl hydride differed as a function of the aromatic character of the ligand. For the pyridine-borane complex 6, a 1.1:1 mixture of 3,4- and 4,5-η2-pyridine isomers was identified in solution (Table 1),47 along with a small amounts of two pyridinyl hydride isomers 6H (5%; 9.40 ppm; JPH = 92.5, JWH = 26.3 Hz) and (6H′) (1%; 9.58 ppm; JPH = 96.0 Hz). We tentatively assign these as C4- and C3-aryl hydrides, but the available data are insufficient to fully assign these species. For the π-ligands in which η2-complexation disrupts less of the inherent aromatic stability of the ligand,5 the η2-bound form is heavily favored. Such is the case with thiophene (8), naphthalene (7), and cyclohexene (9; Table 1). In these cases, we presume that an increased thermodynamic stability relative to the aryl or vinyl hydride is the reason for the lack of a hydridic species. For the latter complexes (7–9), 1H NMR spectra closely match those of the PMe3 analogue, and characterization was not pursued further.27,48,49

Table 1.

Percentages of Dihaptocoordinated Aromatic Complexes and Their C–H Insertion Isomers at 25 °Cb

| η2-Arene | (% of total) | Aryl Hydride | (% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

46% (2) |  |

54% (equilibrium) |

|

82% (3) |  |

18% (equilibrium) 10 : 1 |

|

62% (4) |  |

38% (equilibrium) 2 : 1 |

|

95% (5) |  |

5% (equilibrium) |

|

90% (6) |  |

6% (equilibrium) 5 : 1a |

|

>99% (7) |  |

n.o. |

|

>99% (8) |  |

n.o. |

|

>99% (9) |  |

n.o. |

Assignment uncertain.

All values recorded in benzene-d6 except for 5 recorded in acetone-d6 and 9 in CDCl3. Where equilibrium has been conclusively verified, this is noted.

As has been noted by Jones and co-workers for the rhodium-based systems RhCp(L) and RhCp*(L) (L = PMe3, P(OMe)3),5 the equilibrium between η2-arene and C–H activated adducts depends on the extent of disruption to the π-system when dihaptocoordination occurs. Hence just as for RhCp*(PMe3), the [(η2-R2C=CHR)]/[(R2C=CR)(H)] equilibrium ratio decreases as the ligand is adjusted from alkene to naphthalene to benzene. This trend is followed for the WTp(NO)(PBu3) system. With regard to substituent effects, an interesting difference arises in the rhodium and tungsten systems. For RhCp*(PMe3)(arene), the addition of a methoxy arene substituent shifts the η2-naphthalene/naphthyl hydride equilibrium to heavily favor the η2-arene isomer.21 In a similar manner, the addition of two CF3 groups (p-hexafluoroxylene) shifts the benzene/phenyl hydride equilibrium to favor the η2-arene.50 In contrast, the introduction of either a OMe or a CF3 group to WTp(NO)(PMe3)(benzene) leaves the equilibrium constant practically unchanged, despite clearly stabilizing the complex with respect to ligand dissociation in both cases (Table 1). Yet, as noted above, the rate of C–H activation dramatically decreases with the addition of one or two CF3 groups.

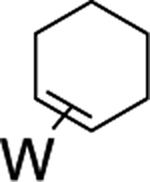

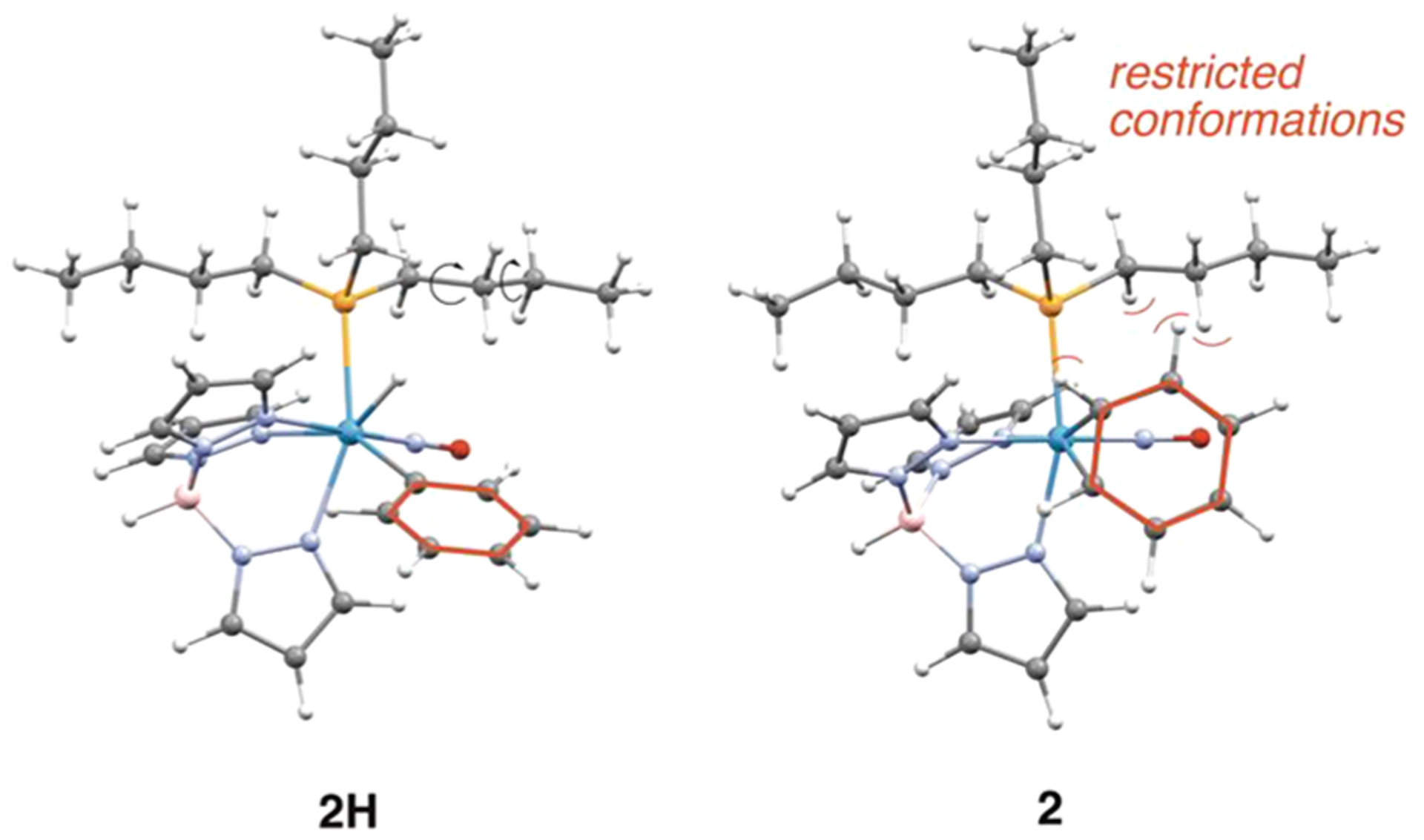

For the rhodium system discussed above,5 and as expected for oxidative addition in general,51 the more electron-rich the metal, the more favorable oxidative addition is expected to be. It is tempting to attribute the increased amount of aryl hydride in equilibrium for 2 compared to its PMe3 analogue to an increase in electron donation from the PBu3 ligand (cf. PMe3). However, structural comparisons show negligible differences in metal-alkene bond lengths between 10 and the previously reported WTp(NO)(PMe3)(η2-cyclohexene) (Supporting Information).52 Also, data collected from NMR and electrochemical experiments of the cyclohexene complex 10 closely resemble those of the analogous PMe3 system (Supporting Information).33 Further, while calculations indicate that ΔH for η2-benzene → phenyl hydride marginally increases (PMe3 3.7 kcal/mol cf. PBu3 2.4 kcal/mol; Supporting Information), the significant shift in the [η2-arene]/[aryl hydride] ratio (from K = 10 to K = 0.4; acetone, 0 °C) resulting when PMe3 is replaced by PBu3 could also be attributed to the decrease in entropy experienced by the butyl chains in 2, where their conformations have been restricted by the rigid η2-bound benzene ring (Figure 7). Consistent with this notion, the methyl/butyl switch also causes the half-life to acetone substitution to be reduced from an hour to 4 min (acetone solvolysis) at 25 °C.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the calculated structures for 2H and 2 illustrating the restricted conformations of the butyl chains on 2 as a result of the protruding benzene ring.

Synthetic Implications.

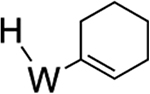

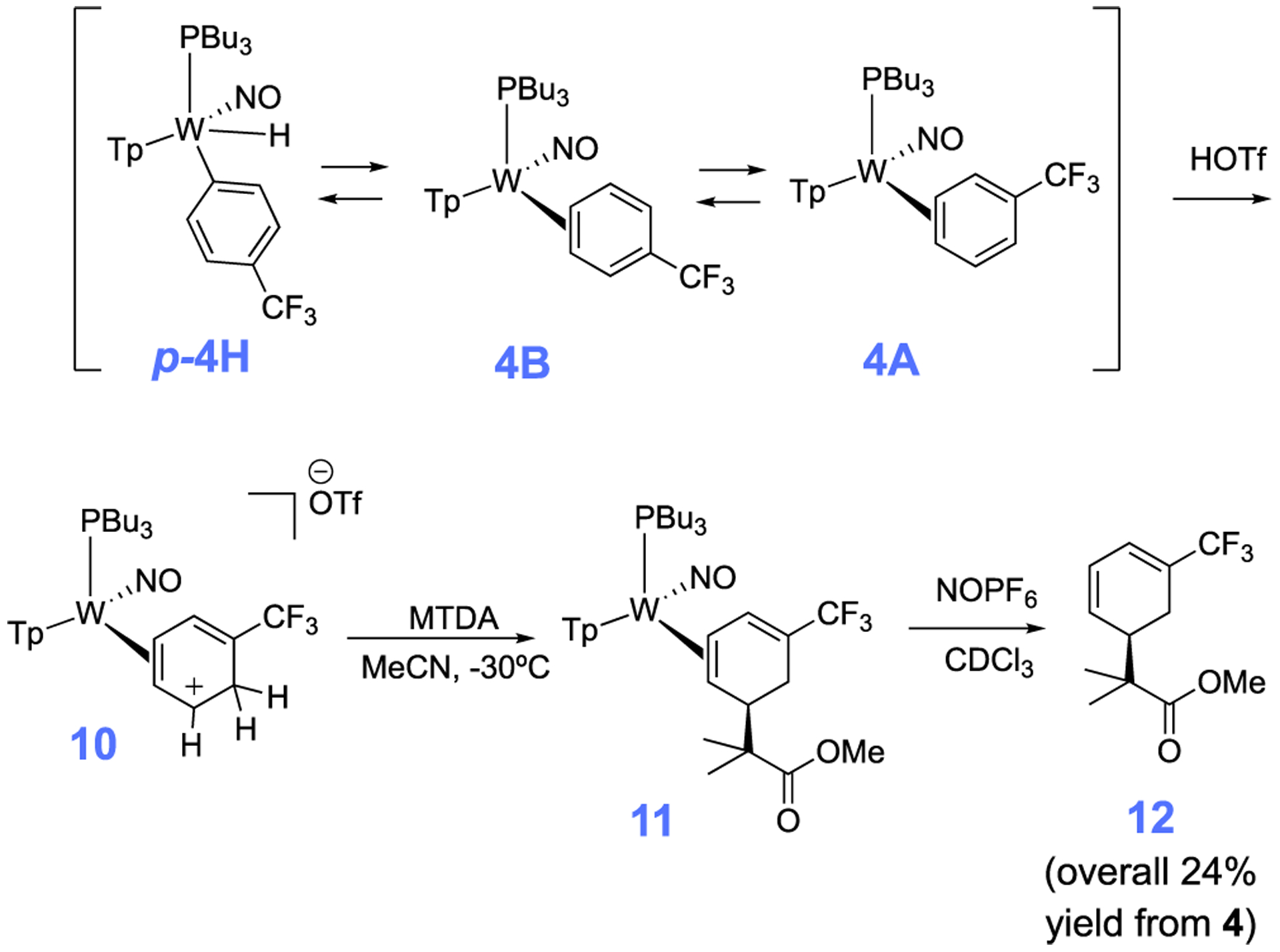

Although roughly 40% of the trifluorotoluene complex 4 is in the form of an aryl hydride, we found that upon treatment with strong acid (HOTf in MeCN) a single η2-arenium species (10) is formed with spectroscopic features consistent with a distorted η2-arenium intermediate.33 Subsequent treatment with the masked enolate MTDA (MTDA = methyl trimethylsilyl dimethylketene acetal) yields the η2-diene 11 prepared in situ (Scheme 7). This reactivity is fully consistent with that observed for the PMe3 analogue.53 A single-crystal XRD study of 11 (Figure 8) confirms the structure shown in Scheme 7. This complex (11) was subjected to oxidative decomplexation to provide the free organic methyl 2-methyl-2-(5-(trifluoromethyl)cyclohexa-2,4-dien-1-yl)propanoate (12) in 24% overall yield (the full characterization of this compound has been previously reported).53 For comparison, the same series of transformations using the PMe3 variant was accomplished with an overall yield of 32%. Compound 12 is a rare example of a diene with a CF3 substituent. Such compounds are of interest in Diels-Alder reactions42,43 and should be good candidates to participate in the inverse-electron-demand variant. As a practical note, in consideration of yields for all reactions starting from W(CO)6, we estimate that the cost to synthesize 12 starting from WTp(NO)(PBu3)(Br) is roughly 1/4th the cost in comparison to the published route from WTp(NO)(PMe3)(Br).53

Scheme 7.

Conversion of the Trifluorotoluene Complexes 4A, 4B, and 4H to a Functionalized Cyclohexadiene 12

Figure 8.

ORTEP diagrams (50% probablility) from SC-XRD studies of 4 and 11. 4A and 4B cocrystallize, and only 4B (major isomer) is shown; hydrogens and solvent not included for clarity.

CONCLUSIONS

The complex WTp(NO)(PBu3)(benzene) provides a rare example of an easily measurable equilibrium between an η2-benzene complex and its phenyl hydride isomer, with an equilibrium constant close to unity at ambient temperatures. We have explored how temperature, solvent, and substituents on the benzene ring affect this equilibrium and have carried out detailed DFT calculations that map out the pathways connecting these two ground states. Whereas conventional wisdom says that a single lowest energy pathway connects a dihaptocoordinated benzene complex to its phenyl hydride isomer, passing through a C–H sigma complex, our calculations reveal a network of intermediates and transition states connecting these two end points that are similar in energy, roughly 4 kcal/mol below dissociation, with multiple competitive dynamical pathways. We have also explored how these reaction pathways enable both interfacial (face-flip) and intrafacial (ring-slip) linkage isomerizations for the arene complex. Highlights of this study include:

Replacement of PMe3 by PBu3 creates an entropy penalty of roughly 2 kcal/mol at 298 K for the dihaptocoordinated isomer. This results in a significantly shorted substitution half-life (ΔG‡ decreases) and a significant increase in the arene/phenyl hydride equilibrium (ΔG decreases).

The bulkier phosphine does not appear to significantly increase the electron density at the metal, as gauged by electrochemical potential, IR absorptions, and solid-state structural data.

The η2-benzene and phenyl hydride isomers are connected through an intermediate best described as a C–H “σ-bond” complex. Two transition states (TS1 and TS2) are closely associated with this intermediate, and the energy surface for all three is remarkably flat. A third transition state (TS3) connects the η2-benzene isomer to another benzene complex, still bound η2, but held together primarily by dispersion forces.

Dynamics simulations reveal a complex network of pathways connecting oxidative addition, dihaptocoordination, and arene dissociation. In particular, these calculations show that dihaptocoordination is not a prerequisite for C–H activation.

In contrast to our previous findings with molybdenum, rhenium, and osmium η2-benzene complexes, the tungsten systems undergo isomerization between the various η2-arene isomers via a C–H insertion rather than via a ring-slip.

The addition of either an OMe or a CF3 substituent to the benzene ring increases the stability of both the η2-arene and the aryl hydride isomers (with little change in the equilibrium constant). This is especially notable for the CF3 analogue, which for the dihaptocoordinate form has a substitution half-life over 250 times longer and a calculated bond strength that is five kcal/mol more stable than its benzene analogue. The addition of a second CF3 group further extends this trend.

When one or two CF3 substituents are added to WTp(NO)(PBu3)(benzene), the rate of C–H activation dramatically decreases from a half-life of seconds to hours without significantly impacting the η2-arene/aryl hydride equilibrium constant.

While there is an apparent correlation between the position of dihapto-binding and the C–H bond that is activated toward oxidative addition (see Table 1), this correlation is not causal. The observed regioselectivity of oxidative addition in this system appears to be governed strictly by thermodynamic factors.

Despite the presence of a considerable amount of aryl hydride, the novel organic chemistry of the η2-trifluorotoluene ligand, initially reported for {WTp(NO)(PMe3)}, is not compromised by replacement of PMe3 with the bulkier phosphine, and the latter system is considerably more economical.

Returning to the larger subject of chemoselectivity of C–H functionalization, this study shows the role a substituent can play in determining not only the location of C–H insertion (consider the high selectivity for meta insertion of anisole) but also the rate of the insertion (with half-lives ranging from seconds to days). It also highlights the important role that temperature, solvent, and the “outer sphere” of the ligand set (e.g., butyl groups) can play in influencing the complex equilibria existing between multiple η2-arene and aryl hydride species.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Methods.

NMR spectra were obtained on 500, 600, or 800 MHz spectrometers. Chemical shifts are referenced to tertramethylsilane (TMS) utilizing residual 1H signals of the deuterated solvents as internal standards. Chemical shifts are reported in ppm, and coupling constants (J) are reported in hertz (Hz). Chemical shifts for 19F and 31P spectra were reported relative to standards of hexafluorobenzene (164.9 ppm) and triphenylphosphine (−6.00 ppm). Infrared spectra (IR) were recorded on a spectrometer as a solid with an ATR crystal accessory, and peaks are reported in cm−1. Electrochemical experiments were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere. Most cyclic voltammetric data were recorded at ambient temperature at 100 mV/s, unless otherwise noted, with a standard three-electrode cell from +1.8 to −1.8 V with a platinum working electrode, acetonitrile (MeCN) solvent, and tetrabutylammonium (TBAH) electrolyte (~1.0 M). All potentials are reported versus the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE) using cobaltocenium hexafluorophosphate (E1/2 = −0.78, −1.75 V) or ferrocene (E1/2 = 0.55 V) as an internal standard. Peak separation of all reversible couples was less than 100 mV. All synthetic reactions were performed in a glovebox under a dry nitrogen atmosphere unless otherwise noted. All solvents were purged with nitrogen prior to use. Deuterated solvents were used as received from Cambridge Isotopes and were purged with nitrogen under an inert atmosphere. When possible, pyrazole (Pz) protons of the (trispyrazolyl) borate (Tp) ligand were uniquely assigned (e.g., “Tp3B”) using two-dimensional NMR data (see Figure S1). If unambiguous assignments were not possible, Tp protons were labeled as “Tp3/5 or Tp4”. All J values for Tp protons are 2 (±0.4) Hz.

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(Br) (1).

A 100 mL round-bottom flask was charged with WTp(Br)2(NO) (18.48 g, 31.6 mmol) along with 80 mL of DCM that had been purged with N2(g), and the heterogeneous yellow reaction mixture was allowed to vigorously stir. Zn dust (7.05 g, 100.8 mmol) was added to this mixture followed immediately by the addition of tri(n-butyl)phosphine (10.03 g, 49.6 mmol). Initially the reaction mixture turned to a lime green color. The solution was allowed to sit for 40 min at which point the reaction mixture had turned to a deep green color. The reaction mixture was then loaded onto a medium 150 mL fritted disc that had been filled with 2 in. of neutral alumina and covered in DCM. The green reaction mixture was then eluted through the neutral alumina column, and a vibrant dark green band was eluted with DCM (200 mL) into a 500 mL filter flask. The DCM solvent was then concentrated in vacuo until ~100 mL of solvent remained. To this homogeneous green solution was added 200 mL of hexanes until a green precipitate was observed to form in solution. Filtering the heterogeneous green reaction mixture through a fine 60 mL fritted disk allowed for the recovery of a deep green crystalline solid. This solid was then washed with 3 × 20 mL of pentane and allowed to dry under dynamic vacuum in a desiccator for 6 h before a mass was taken (9.16 g, 42%). The paramagnetic nature of the compound prevented the use of NMR spectroscopy, but crystals of 1 of suitable quality for X-ray diffraction were grown utilizing vapor diffusion by dissolving in DCM and allowing ether to diffuse into the mixture over several days.

CV (MeCN) E1/2 = −1.36 V, Ep,a = 0.44 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2521 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1580 cm−1.

Anal. Calcd for C21H37BBrN7OPW: C, 35.57; H, 5.26; N, 13.87. Found: C, 35.67; H, 5.26; N, 13.99.

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-benzene) (2) and WTp(NO)(PBu3)(H)(C6H5) (2H).

A 250 mL oven-dried round-bottom flask was loaded with 1 (6.02 g, 8.50 mmol) followed by benzene (200 mL), and the homogeneous green reaction mixture was allowed to stir. To this solution was added 30–33% by weight sodium dispersion in paraffin (7.04 g, 54.0 mmol). After 4 h of stirring the reaction mixture had turned to a golden yellow color, and completion of the reaction was confirmed by cyclic voltammetry (no indication of 1). The golden brown reaction mixture was then filtered through a coarse 60 mL fritted disc that had been filled with 1 in. of Celite and set in pentane. The Celite was then washed with 100 mL of ether to collect a brown band that developed on the Celite. This reaction mixture was then loaded on a coarse 150 mL fritted disc that had been filled with 2 in. of silica and saturated with pentane. A yellow band was then eluted with a 10:1 ether:benzene mixture (300 mL total), collected, and then concentrated until 50 mL of solution remained. To this solution was added 200 mL of pentane. The volume was reduced by half in vacuo until a yellow solid precipitated from solution. The mixture was then filtered through a fine 30 mL fritted disc to isolate a vibrant yellow solid. This solid was then washed with chilled pentane (3 × 10 mL) and allowed to desiccate for 6 h to yield a bright yellow powder (1.21 g, 20%).

CV (MeCN) Ep,a = −0.16 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2504 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1564 cm−1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 8.00 (1H, d, Tp5), 7.99 (1H, d, Tp5), 7.94 (1H, d, Tp3), 7.85 (1H, d, Tp5), 7.45 (1H, d, Tp3C), 6.97 (1H, d, Tp3A), 6.81 (1H, buried, H6), 6.80 (1H, buried, H3), 6.36 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.30 (2H, overlapping t, Tp4), 5.70 (2H, overlapping m, H4 and H5), 4.11 (1H, m, H1), 2.30 (1H, m, H2), 1.26 (6H, m, PBu3), 1.14 (6H, overlapping with 2H, PBu3), 0.89 (6H, overlapping with 2H, PBu3), 0.76 (9H, t, J = 7.3, PBu3). 31P NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): −2.74 (JWP = 308). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 141.9 (Tp3/5), 141.3 (Tp3/5), 137.4 (Tp3/5), 136.6 (Tp3/5), 136.1 (Tp3/5), 134.4 (Tp3/5), 133.2 (C6), 128.9 (C3), 117.4 (C4/C5), 116.6 (C4/C5), 107.0 (Tp4), 106.9 (Tp4), 106.1 (Tp4), 63.9 (C2), 62.9 (C1, JPC = 8.6), 26.6, 26.0, 25.5, 25.1, 24.9, 22.6, 14.4 14.1 (overlapping PBu3 signals for 2 and 2H isomer).

IR: ν(WH) = 1989 cm−1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 9.62 (1H, m, JWP = 97.3, JWH = 31.1,W–H), 8.15 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 8.06 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 8.04 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.75 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.68 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.20 (2H, broad, H2 and H6), 6.97 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.20 (2H, broad, H3/H5), 6.81 (2H, t, J = 7.2, H2/6), 6.71 (1H, t, J = 7.2, H4), 6.45 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.41 (1H, t, Tp4), 5.94 (1H, t, Tp4), 1.26, 1.14, 0.89 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 2 and 2H isomers), 0.79 (9H, t, J = 7.3, PBu3). 31P NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): + 16.3 (JWP = 173). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 178.5 (C1, JPC = 6.0), 145.9 (Tp3/5), 145.7 (Tp3/5), 145.2 (Tp3/5), 138.3 (Tp3/5), 137.4 (Tp3/5), 137.3 (Tp3/5), 135.4 (C2/C6), 127.6 (C3/C5), 107.3 (Tp4), 107.0 (Tp4), 105.7 (Tp4), 26.6, 26.0, 25.5, 25.1, 24.9, 22.6, 14.4 14.1 (overlapping PBu3 signals for 2 and 2H isomers).

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-2,3-anisole) (3A and 3B) and WTp(NO)(PBu3)(H)(C6H4OMe) (o-3H and m-3H).

An oven-dried 250 mL round-bottom flask was charged with a stir bar and 200 mL of anisole, followed by complex 1 (11.35g, 16.0 mmol), and allowed to vigorously stir to generate a homogeneous green reaction mixture. Next 30–33% by weight sodium dispersion in paraffin (6.13 g, 88.8 mmol) was added. After 2.5 h, the reaction mixture had turned to a golden yellow color, and the reaction was confirmed to be completed by cyclic voltammetry after a ~ 2 mL aliquot of this reaction mixture had been filtered through a pipet column filled with Celite. The bulk golden brown reaction mixture was then filtered through a coarse 150 mL fritted disc that had been filled with 2 in. of Celite and saturated with anisole. Vacuum was applied to elute the colored filtrate, and the Celite plug was washed with 100 mL of addition anisole to collect the brown solution into a 500 mL filter flask. The filtrate was then loaded onto a 10 cm silica column on a coarse 150 mL fritted disc that had been set in pentane. After the entire filtrate had been loaded, the column was washed with 250 mL of pentane total to wash away free anisole. The column was then rinsed with ~200 mL of ether to elute a vibrant orange band. Once the orange band was near the bottom of the column, the clear filtrate was discarded and elution with ether continued so as to collect the desired product. The orange band on the column was eluted with a total of 700 mL and collected in a 1000 mL filter flask. In the filter flask the initially orange band now appears as a homogeneous yellow solution. The solvent was the removed in vacuo until the volume had been reduced to <100 mL of ether. To this solution was added 500 mL of pentane to generate a heterogeneous yellow mixture. The volume was reduced by half in vacuo, and the resulting yellow solid was filtered through a fine 60 mL fritted disc and washed with 3 × 30 mL of pentane to yield a vibrant yellow solid (5.79g, 49%). Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown from a DCM/pentane mixture that was allowed to sit at −30 °C over several hours to grow 3A and support the elemental composition of the complex.

CV (MeCN) Ep,a = −0.17 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2488 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1559 cm−1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 8.13 (1H, d, Tp3A), 8.00 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.97 (1H, d, Tp3/5B), 7.95 (1H, d, Tp5C), 7.84 (1H, d, Tp5A), 7.41 (1H, d, Tp3C), 6.41 (1H, overlap, H4), 6.35 (1H, t, Tp4B), 6.31 (1H, t, Tp4C), 6.27 (1H, t, Tp4A), 5.70 (1H, dd, J = 6.9, 1.7, H5), 5.08 (1H, d, J = 6.9, H6) 4.01 (1H, t, J = 10.7, H2), 3.68 (3H, s, OMe), 2.30 (1H, m, H3), 2.20, 2.03, 1.93, 1.86, 1.75, 1.27, 1.14, 1.00, 0.88, 0.78 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H). 31P NMR (DME, δ, 25 °C): −3.34 (JWP = 303). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 165.1 (C1), 145.7 (Tp3/5), 141.9 (Tp3/5), 141.5 (Tp3/5), 137.3 (Tp3/5), 136.7 (Tp3/5), 136.2 (Tp3/5), 124.8 (C4), 117.2 (C5), 107.0 (Tp4), 106.8 (Tp4), 105.9 (Tp4), 91.6 (C6), 64.5 (C3), 58.4 (C2, d, JPC = 10.9), 54.0 (OMe), 26.5, 26.0, 25.4, 25.1, 24.9, 22.9, 22.6, 14.0 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H).

1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 8.13 (1H, d, Tp3A), 8.05 (1H, d,Tp3B/C), 7.99 (1H, d, Tp3/5), (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.45 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.05 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.46(1H, d, Tp3C), 6.34 (1H, t, Tp4C), 6.30 (2H, overlapping resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H, Tp4A/B, and H4), 5.60 (1H, dd, J = 6.5, 2.1, H5), 4.89 (1H, d, J = 6.5, H6), 4.18 (1H, m, H3), 2.30 (1H, m, H2), 2.20, 2.03, 1.93, 1.86, 1.75, 1.27, 1.14, 1.00, 0.88, 0.78 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H). 31P NMR (DME, δ, 25 °C): −2.98 (JWP = 299). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 159.7 (C1), 135.0–147.0 overlapping Tp3/5 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H, 141.8 (Tp3/5), 145.8 (Tp3/5), 107.6 (Tp4), 106.5 (Tp4), 105.0 (Tp4). 125.0 (C4), 117.2 (C5 overlap with 3A), 88.8 (C6), 63.1 (C3, d, JPC = 11.1), 60.6 (C2), 53.9 (OMe), 26.5, 26.0, 25.4, 25.1, 24.9, 22.9, 22.6, 14.0 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H).

1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 9.57 (1H, m, JPH = 97.2, JWH = 31.2, W–H), 8.03 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.85 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.77 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.45 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.68 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.28 (1H, t, J = 8.05, H5), 7.05 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 6.92 (1H, s, H4), 6.76 (1H, broad, H6), 6.44 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.30 (2H, buried, H2, and Tp4), 5.95(1H, t, Tp4), 3.51 (3H, broad s, OMe). 2.20, 2.03, 1.93, 1.86, 1.75, 1.27, 1.14, 1.00, 0.88, 0.78 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H). 31P NMR (DME, δ, 25 °C): 15.55 (JWP = 176). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 180.1 (C3), 159.7 (C1), 144.3(Tp3/5), 142.9 (Tp3/5), 136.5 (Tp3/5), 135.2 (Tp3/5), 134.5 (Tp3/5), 130.9 (C4), 127.7 (C6), 125.0 (C2), 121.0 (C4), 107.3 (Tp4), 105.7 (Tp4), 106.4 (Tp4), 53.9 (OMe), 26.5, 26.0, 25.4, 25.1, 24.9, 22.9, 22.6, 14.0 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for 3A, 3B, m-3H).

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-3,4-a,a,a-trifluorotoluene) (4A and 4B) and WTp(NO)(PBu3)(H)(C6H5CF3) (p-4H and m-4H).

A 4-dram vial was charged with a stir pea, trifluorotoluene (2 mL, 16.2 mmol), and 2 (1.00 g, 1.35 mmol), and the initially homogeneous yellow reaction mixture was allowed to stir. Over time the reaction mixture turned from a homogeneous yellow to a heterogeneous yellow, and at the end of 6 h this reaction mixture was added to 10 mL of pentane and allowed to sit at −30 °C for 30 min. The heterogeneous yellow mixture was then filtered through a fine 15 mL fritted disc to yield a vibrant yellow-gold powder. This powder was washed with 3 × 10 mL of pentane that had been chilled to −30 °C and allowed to dry under active vacuum in a desiccator for 4 h and then in a static vacuum in a desiccator overnight. A mass was then taken the next day of the product, a vibrant yellow solid (0.716 g, 68%).

CV (MeCN) Ep,a = +0.10 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2519 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1567 cm−1. 1H NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 7.93 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.88–7.90 (4H, overlapping Tpd resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H), 7.80 (2H, overlapping d, Tp3/5), 7.33 (1H, d, J = 5.9, H2), 6.97 (2H, overlapping, H5), 6.33 (1H, t, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, Tp4), 6.31 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.25 (1H, t overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, m-4H and p-4H, Tp4), 5.76 (1H, overlapping d, H6), 3.89 (1H, m, H4), 2.08 (1H, m, H3), 1.83 (6H, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 1.24 (6H, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 1.08 (6H, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 0.80 (9H, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3). 31P NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 25 °C): −4.77 (JWP = 294). 19F-NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 25 °C): −62.88 (CF3, s). 13C NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 146.0 (3C, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, Tp3/5), (3C, 141.9, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, Tp3/5), 111.1 (C1 of 4B), 106.2 to 107.7 (Tp4, overlapping resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H), 126.0 or 125.3 (CF3, q, JCF = 269.0 or 267.0), 63.2 (C4, d, JPC = 9.2), 63.5 (C3), 25.3 (overlapping PBu3 resonances), 25.0 (overlapping PBu3 resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H), 22.8 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H), 13.9 (overlapping PBu3 resonances with 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H). Anal. Calcd for C28H42BF3N7OPW: C, 43.38; H, 5.46; N, 12.65. Found: C, 43.08; H, 5.52; N, 12.39..

1H NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 8.07 (1H, d, Tp3A), 7.90 (3H, overlapping d, Tp3/5), 7.79 (1H, d, Tp5A), 7.38 (1H, d, 5.13, H2), 7.29 (1H, d, Tp3C), 6.97 (1H, overlapping, H5), 6.33 (1H, t, Tp4B), 6.29 (1H, t, Tp4A), 6.25 (1H, t, Tp4C), 5.76 (1H, overlapping, H6), 3.76 (1H, m, H3), 2.17 (1H, m, H4), 1.83 (6H, overlapping with other isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 1.24 (6H, overlapping with other isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 1.08 (6H, overlapping with other isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3), 0.80 (9H, overlapping with other isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H, PBu3). 31P NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 25 °C): −5.09 (JWP = 294). 19F-NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 25 °C): −62.13 (CF3, s). 13C NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 146.0 (3C, overlapping with other isomers Tp3/5), (3C, 141.9 overlapping with other isomers), 135.7 (overlapping C2 and C5), 110.3 (C6), 126.0 or 125.3 (CF3, q, JCF = 269 or 267), 106.2 to 107.7 (overlapping Tp4 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H), 63.6 (C4), 60.3 (C3, d, JPC = 7.9), 25.3 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H and m-4H), 25.0 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H), 22.8 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B, p-4H, and m-4H), 13.9 (overlapping PBu3 resonances for isomers 4A, 4B,p-4H, and m-4H).

Select Resonances for m-4H and p-4H.

1H NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 9.59 (1H, m, JPH = 98, JWP = 30,W–H for p-4H), 9.56 (1H, m, JPH = 95, JWP = 30, W–H for m-4H), 7.64 (1H, d, overlapping Tpd for either p-4H or m-4H), 7.11 (1H, d, J = 7.19, Ph-ring proton for p-4H or m-4H), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 7.44, Ph-ring proton for p-4H or m-4H), 6.91 (3H, buried, overlapping Tpd for either p-4H or m-4H and H3/5 for p-4H), 5.95 (1H, t, Tp4 for m-4H), 5.94 (1H, t, Tp4 for p-4H). 31P NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 25 °C): 15.80 and 15.53, (JWP = 176 for 15.53 resonance, JWP = 174 for 15.80 resonance, p-4H and m-4H). 13C NMR (MeCN-d3, δ, 0 °C): 180.2 (overlapping C4 and C3 for p-4H and m-4H), 146.1 (Ph-ring carbon for p-4H), 145.0 (Ph-ring-carbon for m-4H), 136.3 (Ph-ring carbon for p-4H), 130.5 (Ph-ring carbon for p-4H).

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-4,5,-bis-trifluoromethylbenzene) (5).

A 4-dram vial was charged with a stir bar, 1,2-bis-(trifluoromethyl)benzene (2.00 g, 9.34 mmol), and 3 (0.103 g, 0.140 mmol), and the initially homogeneous yellow reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 24 h. Over time the reaction mixture turns from a homogeneous yellow to a light brown color, and at the end of 6 h this reaction mixture was added to 10 mL of pentane and allowed to sit at −30 °C for 16 h. Over time crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction developed, and the light tan solid was then isolated on a fine 15 mL fritted disc. This solid was then washed with 3 × 10 mL of pentane that had been chilled to −30 °C and allowed to dry under static vacuum for 16 h. A mass was then taken the next day of the product, a light tan solid (0.053 g, 45%). Atomic composition consistent with the crystal structure.

CV (MeCN) Ep,a = +0.47 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2490 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1587 cm−1. 1H NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): 8.18 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.80 (1H, d, J= 6.50, H6), 7.79 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.71 (1H, d, J= 5.9, H3), 7.30 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.28 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.26 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 6.71 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 5.75 (2H, overlapping t, Tp4), 5.69 (1H, t, Tp4), 3.42 (1H, m, H4), 2.12 (1H, m, H5), 1.71 (3H, m, PBu3), 1.59 (3H, m, PBu3), 1.15 (3H, m, PBu3), 1.10 (3H, m, PBu3), 0.91 (3H, m, PBu3), 0.78 (9H, t, J= 7.36, PBu3), 31P NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): −3.96 (JWP = 292). 19F-NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): −57.6 (3F, q, JFF = 12.6, CF3), −57.9 (3F, q, JFF = 12.6, CF3). 13C NMR (benzene-d6, δ, 25 °C): 145.6 (Tp3/5), 142.3 (Tp3/5), 140.7 (Tp3/5), 140.4 (C6, q, JCF = 7.2), 139.3 (broad, C3), 136.4 (Tp3/5), 135.8 (Tp3/5), 135.5 (Tp3/5), 125.1 (overlapping CF3 resonances, JCF = 270.0), 115.1 (q, JCF = 31.1, C1/C2), 113.2 (q, JCF = 31.1, C1/C2), 106.6 (Tp4), 106.5 (Tp4), 106.4 (Tp4), 60.1 (C5), 60.0 (C4, JPC = 9.3), 25.1 (d, JPC = 3.1, PBu3), 24.7 (d, JPC = 12.4, PBu3), 22.8 (d, JPC = 23.1, PBu3), 13.8 (PBu3).

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-3,4-pyridineborane) (6).

A solid of 3 (500 mg, 0.678 mmol) was added to a 4-dram vial containing stirring neat pyridine-borane (3.00 g, 32.3 mmol). After stirring for 2 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with 6 mL of THF, followed by 25 mL of Et2O and then 90 mL of hexanes. The solution was allowed to settle for 15 min, while a Celite column (1 cm tall) was prepared in a 15 mL medium porosity fritted disk. The solution was decanted through the Celite, leaving a green oil. The oil was again diluted with 6 mL of THF, followed by 25 mL of Et2O and then 90 mL of hexanes. The solution was decanted through the Celite, leaving a clumpy material in the vial. The material captured by the Celite was dissolved in 6 mL of THF and returned to the vial. Upon complete dissolution of all solids, the solution was diluted with 25 mL followed by 150 mL of hexanes. The precipitate was collected on the Celite column and then redissolved with 20 mL of THF. The resulting solution was diluted with 35 mL of Et2O and 150 mL of hexanes, forming a bright yellow precipitate. The precipitate was collected on a 15 mL medium porosity fritted funnel, rinsed with 2 × 5 mL of hexanes, transferred wet to a vial, and placed under dynamic vacuum (0.185 g, 38%).

CV (DMA) Ep,a = +0.59 V (NHE). IR: ν(BH) = 2519 cm−1, ν(BH3) = 2348, 2288, 2256 cm−1, ν(NO) = 1587 cm−1. 1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 15 °C): 8.62 (1H, d, J = 4.21, H2), 8.14 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 8.09 (1H, Tp3/5), 8.04 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.92 (2H, d overlapping, Tp3/5), 7.62 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 6.77 (1H, t, J = 6.34, H5), 6.44 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.37 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.34 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.18 (1H, d, J = 7.03, H6), 3.65 (1H, m, H3), 2.17 (1H, t, J = 7.54, H4), 1.92 (6H, m overlapping with minor, PBu3), 1.20 (12H, overlapping resonances and overlapping with minor, PBu3), 0.79 (9H, t, J = 7.51, PBu3). 31P NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 25 °C): −3.6 (PMe3, JWP = 284). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 167.7 (C2), 146.0 (Tp3/5), 142.3 (Tp3/5), 141.7 (Tp3/5), 138.2 (Tp3/5), 137.4 (Tp3/5), 136.7 (Tp3/5), 127.2 (C5/6), 125.3 (C5/6), 107.6 (Tp4 overlapping with minor), 107.4 (Tp4), 106.7 (Tp4), 61.1 (C4), 59.3 (C3, d, JPC = 7.1), 25.5 (PBu3 overlap with minor isomer), 25.0 (PBu3, overlap with minor isomer 6B), 23.4 (PBu3, d, JPC = 24.6), 14.0 (PBu3 overlap with minor isomer 6A). Anal. Calcd for C26H45B2N8OPW: C, 43.24; H, 6.28; N, 15.52. Found: C, 42.94; H, 6.31; N, 15.37.

1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 15 °C): 8.50 (1H, d, J = 4.50, H2), 8.10 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 8.09 (2H, d overlapping, Tp3/5), 8.01 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.92 (1H, d overlapping with major, Tp3/5), 7.59 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 6.74 (1H, t, J = 6.62, H5), 6.43 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.41 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.39 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.24 (1H, d, J = 6.62, H6), 3.92 (1H, m, H4), 2.07 (1H, buried, H3), 1.91 (6H, m overlapping with major, PBu3), 1.20 (12H, overlapping resonances and overlapping with major, PBu3), 0.77 (9H, t, J = 7.41, PBu3). 31P NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 25 °C): −3.9 (JWP = 291). 13C NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 0 °C): 169.9 (C2), 146.4 (Tp3/5), 144.1 (Tp3/5), 142.3 (Tp3/5), 138.1 (Tp3/5), 137.6 (Tp3/5), 136.7 (Tp3/5), 127.6 (C5/6), 126.7 (C5/6), 107.6 (Tp4 overlapping with minor), 107.5 (Tp4), 107.1 (Tp4), 61.4 (C4, d, JPC = 9.86), 58.8 (C3), 25.5 (PBu3 overlap with major isomer), 25.0 (PBu3, overlap with major isomer), 22.8 (PBu3, d, JPC = 24.2), 14.0 (PBu3 overlap with major isomer).

Partial HNMR data of 6H (5%): 1H NMR (acetone-d6, δ, 25 °C): 9.40 (1H, m, JPH = 92.5, JWH = 26.3, W–H), 8.20 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 8.08 (1H, Tp3/5), 7.80 (1H, d,Tp3/5), 7.79 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 7.14 (1H, d, Tp3/5), 6.53 (1H, t, Tp4), 6.14 (1H, t, Tp4). 6H′ (1%): 9.58 ppm with a JPH = 96.0 Hz (not enough signal to determine JWH).

Synthesis of WTp(NO)(PBu3)(η2-1,2-cyclohexene) (9).

To a 4-dram vial was added 3 (0.492 g, 0.67 mmol) along with cyclohexene (1 mL, 9.9 mmol). The initially heterogeneous yellow reaction mix was allowed to stir over 4 h, during which time the solution turned to a light homogeneous brown color. The reaction mixture was then added to 15 mL of pentane that had been chilled to −30 °C to precipitate out a light pink solid. This solid was then collected on a fine 15 mL fritted disc. The solid was then washed with 3 × 5 mL of pentane, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo and subsequently picked up in a minimal amount of DCM (1 mL) and added to 15 mL of standing pentane in a 4-dram vial. This solution was allowed to sit at −30 °C overnight during which time a light yellow solid precipitated from solution. Combining the masses of the two isolated fractions gave a final yield (0.235 g, 49% yield). Atomic composition of the complex consistent with the crystal structure.