Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to identify predictors of electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among teenagers.

Design and setting

A prospective population-based cohort study of schoolchildren in northern Sweden.

Participants

In 2006, a cohort study about asthma and allergic diseases among schoolchildren started within the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden studies. The study sample (n=2185) was recruited at age 7–8 years, and participated in questionnaire surveys at age 14–15 and 19 years. The questionnaire included questions about respiratory symptoms, living conditions, upper secondary education, physical activity, diet, health-related quality of life, parental smoking and parental occupation. Questions about tobacco use were included at age 14–15 and 19 years.

Primary outcome

E-cigarette use at age 19 years.

Results

At age 19 years, 21.4% had ever tried e-cigarettes and 4.2% were current users. Among those who were daily tobacco smokers at age 14–15 years, 60.9% had tried e-cigarettes at age 19 years compared with 19.1% of never-smokers and 34.0% of occasional smokers (p<0.001). Among those who had tried e-cigarettes, 28.1% were never smokers both at age 14–15 and 19 years, and 14.4% were never smokers among the current e-cigarette users. In unadjusted analyses, e-cigarette use was associated with daily smoking, use of snus and having a smoking father at age 14–15 years, as well as with attending vocational education, physical inactivity and unhealthy diet. In adjusted analyses, current e-cigarette use was associated with daily tobacco smoking at age 14–15 years (OR 6.27; 95% CI 3.12 to 12.58), attending a vocational art programme (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.04 to 4.77) and inversely associated with eating a healthy diet (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.92).

Conclusions

E-cigarette use was associated with personal and parental tobacco use, as well as with physical inactivity, unhealthy diet and attending vocational upper secondary education. Importantly, almost one-third of those who had tried e-cigarettes at age 19 years had never been tobacco smokers.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This paper presents data from a prospective cohort study with high response rates and few participants lost to follow-up.

Self-reported use of tobacco or e-cigarettes was not validated by objective measures.

E-cigarette use was measured only at the last follow-up.

Introduction

In the last 10 years, the use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) has increased rapidly among teenagers,1–3 but the increase seems to level off in some countries including England1 and Sweden.4 One explanation for their popularity may be that they are perceived as less harmful and less addictive than tobacco cigarettes.5–7 Although the levels are considerably lower than in conventional cigarette smoke, e-cigarette aerosol does contain carcinogenic and toxic substances8 9 and they can deliver similar nicotine levels as conventional cigarettes, and thereby cause nicotine addiction.10 11

Because e-cigarettes are portrayed as an alternative to tobacco smoking, studies of predictors for e-cigarette use have mostly evaluated the association with smoking conventional cigarettes.12 13 For instance, e-cigarette use was more common among current smokers than former smokers14 15 and younger smokers appear to be more prone to start using e-cigarettes than older smokers.15 16 A major concern regarding e-cigarettes is that they also seem to appeal to non-smoking teenagers17 18 and might serve as a gateway to initiation of tobacco smoking as well as other drugs.11 17 19 However, another explanation for the association between e-cigarette use and tobacco smoking may be that these behaviours share many risk factors such as social disadvantage, addictive behaviours, low academic achievement, and having family members or friends that smoke.20–24 These shared characteristics may serve as a common liability for any tobacco or nicotine product,25 26 which implies that the sequential order of product initiation is of less importance. Nevertheless, predictors of e-cigarette use need to be identified both among smoking and non-smoking teenagers, but prospective studies are lacking. In Sweden, smoking is more common among women, while the use of snus (smokeless, moist, grounded tobacco placed under the upper lip) and e-cigarettes is more common among men14 27–29; but there are no epidemiological studies on sex differences in e-cigarette use among Swedish teenagers.4

The aim of the present study was to identify predictors of e-cigarette use in a prospective population-based cohort study of teenagers in Sweden followed from 14–15 to 19 years of age.

Methods

Study sample

Within the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden studies, a population-based paediatric cohort study has been ongoing since 2006. The starting point was a parental questionnaire survey inviting all children in first and second grade (age 7–8 years) in three municipalities of northern Sweden: Luleå, Piteå and Kiruna.30–32 The cohort was followed up at age 14–15 years and 19 years. At age 19 years, the study sample consists of the 2185 individuals who participated in all surveys, corresponding to 82% of the invited and 78% of the original cohort (n=2819).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire surveys at age 14–15 years and 19 years were performed at school. The questionnaire included the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood core questionnaire33 with additional questions about asthma and allergic diseases including physician diagnoses, symptoms, use of medicine and heredity.30 Other questions included possible risk factors such as living conditions, physical activity, diet, parental smoking and parental occupation. In the questionnaire at the age of 14–15 years, questions about smoking and use of snus were included34; and at age 19 years, questions about e-cigarettes were added. At age 14–15 years, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the KIDSCREEN-10 questionnaire which consists of 10 items with responses on a 5-point ordinal scale.35 The crude values were transformed into a single score and poor HRQoL was defined as a value lower than the group mean score minus 0.5 SD.

Definitions

At age 14–15 years and 19 years, respectively, tobacco use was defined based on the questions ‘Do you smoke/use snus?’ as Never if they smoked/used snus ‘Never’; Occasional, if they smoked/used snus ‘Almost never’, ‘Monthly’ or ‘Weekly’; and Daily if they smoked/used snus ‘Almost daily’ or ‘Daily’. At age 19 years, the category Former smoker was also included in the analyses. Former smoker was defined as either self-reported former smoker in the questionnaire at age 19 years, or reporting being an occasional or daily smoker at age 14–15 years and non-smoker at age 19 years.

At age 19 years, e-cigarette use was defined based on the question ‘Do you use e-cigarettes?’ as Ever tried e-cigarettes if they responded ‘No, have quit’, ‘Have only tried’, ‘Use sometimes’ or ‘Use daily’; and Current e-cigarette user if they responded ‘Use sometimes’ or ‘Use daily’.

In Sweden, the upper secondary school education offers 3-year programmes that are vocational or preparatory for higher education (eg, economics, natural science, social science or technology). The programme is chosen at age 15 years and they attend the programme until graduation at age 19 years. We divided the vocational programmes into work shop (eg, building and construction, electricity, energy, vehicle, transport or industrial technology), service (eg, child and recreation, hotel and tourism, restaurant management, or health and social care) and art (theatre, dance or music).

Healthy diet was defined based on a score between 0 and 4 with 1 point each for: eating fish every week; eating a fruit every day; eating fast food less than every week and drinking soda less than every week. These four items were chosen based on recommendations by the Swedish National Food Agency.

Physical activity was defined as regular participation in sports or physical activity, not including physical education at school.

Parental socioeconomic status was based on parental occupation reported in a parentally completed questionnaire at age 7–8 years, defined according to the socioeconomic classification by Statistics Sweden36 and categorised into the following groups: manual workers in service, manual workers in industry, assistant non-manual employees, intermediate non-manual employees, self-employed, unemployed, and professionals and executives.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS statistics V.24. Differences in proportions between groups were analysed by the Χ2 test. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Individuals with missing data in questions about exposure to parental smoking (2.7%), tobacco use at age 14–15 years (0.97%–1.1%) and 19 years (1.0%–1.7%), and e-cigarette use at age 19 years (1.8%) were excluded from the analyses. Factors significantly associated with e-cigarette use in unadjusted analyses were included in adjusted logistic regression models. Sex was also included in the analysis. The results were expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. The adjusted analyses were also performed among those who were never smokers and did not use snus at age 14–15 years. A representativeness analysis was performed comparing the n=2185 individuals who participated in the follow-up surveys both at 14–15 years and 19 years with the n=634 individuals who did not participate in the follow-up surveys. Participants and non-participants were compared regarding sex, parental smoking habits, single-parent household and prevalence of asthma at recruitment.

Results

The prevalence of tobacco use at ages 14–15 and 19 years

At age 14–15 years, the majority of the adolescents were never smokers, 90.0% (table 1). The prevalence of occasional smoking was 6.8% and 3.2% were daily smokers, with similar prevalence in girls and boys. Daily use of snus was significantly more common among boys than girls, 5.0% vs 0.8%, p<0.001.

Table 1.

The prevalence of smoking and use of snus at age 14–15 years and 19 years, and e-cigarette use at age 19 years*

| Girls | Boys | Difference by sex, p value | All | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Parental smoking at age 14–15 years | |||||||

| Father smoker | 129/1034 | 12.5 | 127/1093 | 11.6 | 0.544 | 256/2127 | 12.0 |

| Mother smoker | 115/1036 | 11.1 | 146/1092 | 13.4 | 0.111 | 261/2128 | 12.3 |

| Tobacco use at age 14–15 years | |||||||

| Never smoker | 932/1053 | 88.5 | 1012/1108 | 91.3 | 1944/2161 | 90.0 | |

| Occasional smoker | 81/1053 | 7.7 | 67/1108 | 6.0 | 148/2161 | 6.8 | |

| Daily smoker | 40/1053 | 3.8 | 29/1108 | 2.6 | 0.083 | 69/2161 | 3.2 |

| Never snus user | 1036/1055 | 98.2 | 1034/1109 | 93.2 | 2070/2164 | 95.7 | |

| Occasional snus user | 11/1055 | 1.0 | 19/1109 | 1.7 | 30/2164 | 1.4 | |

| Daily snus user | 8/1055 | 0.8 | 56/1109 | 5.0 | <0.001 | 64/2164 | 3.0 |

| Tobacco use at age 19 years | |||||||

| Never smoker | 666/1044 | 63.8 | 662/1105 | 59.9 | 1328/2149 | 61.8 | |

| Former smoker | 14/1044 | 1.3 | 15/1105 | 1.4 | 29/2149 | 1.3 | |

| Occasional smoker | 267/1044 | 25.6 | 346/1105 | 31.3 | 613/2149 | 28.5 | |

| Daily smoker | 97/1044 | 9.3 | 82/1105 | 7.4 | 0.021 | 179/2149 | 8.3 |

| Daily snus user | 65/1052 | 6.2 | 247/1111 | 22.2 | <0.001 | 312/2163 | 14.4 |

| E-cigarette use at age 19 years | |||||||

| Ever tried/used e-cigarettes | 158/1049 | 15.1 | 302/1096 | 27.6 | <0.001 | 460/2145 | 21.4 |

| Current e-cigarette user | 36/1049 | 3.4 | 54/1096 | 4.9 | 0.084 | 90/2145 | 4.2 |

*Individuals with missing answers in the individual questions about tobacco use and e-cigarette use were excluded from the analysis.

e-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

At age 19 years, 61.8% were never smokers and 8.3% daily smokers. Occasional smoking was more common among boys than girls, 31.3% vs 25.6%; while daily smoking was more common among girls than boys, 9.3% vs 7.4% (p=0.021). Daily use of snus had increased to 14.4% and was still more common among boys.

The prevalence of e-cigarette use at age 19 years

At age 19 years, 21.4% (n=460) of the cohort had ever tried e-cigarettes, with a higher prevalence among boys than girls, 27.6% vs 15.1%, p<0.001, and 4.2% (n=90) were current e-cigarette users. The prevalence of dual use of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes was 1.7% (n=36), dual use of e-cigarettes and snus was 1.3% (n=28); while 0.5% (n=10) used all three products.

E-cigarette use at age 19 years in relation to tobacco use at age 14–15 years

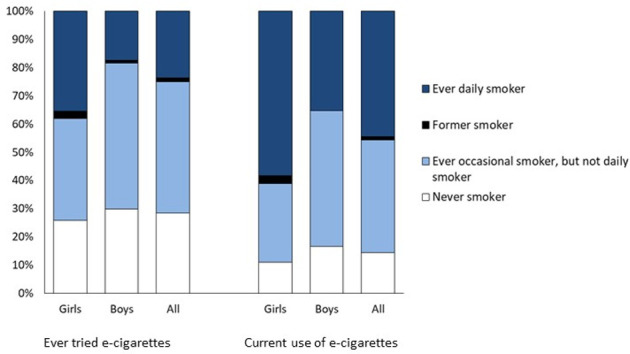

Among those who were daily tobacco smokers at age 14–15 years, 60.9% (n=39) had tried e-cigarettes at age 19 years, compared with 34.0% (n=50) among occasional smokers and 19.1% (n=364) among never smokers (p<0.001). Of the daily smokers at age 14–15 years, 28.1% (n=18) were current e-cigarette users compared with 7.5% (n=11) among occasional smokers and 3.2% (n=61) among never smokers (table 2). Of the current e-cigarette users at age 19 years, 14.4% reported being never smokers both at age 14–15 years and at 19 years (figure 1). Corresponding proportion of never smokers among those who had tried e-cigarettes was 28.5%. Among those who were former smokers at age 19 years, 24.1% (n=7) had tried e-cigarettes but only one individual was a current user. At age 19 years, there were 13 individuals reported having quit using e-cigarettes. Of them, 10 were occasional smokers, 2 daily smokers, 1 never smoker but none of them was a former smoker.

Table 2.

E-cigarette use at the age of 19 years in relation to smoking, use of snus and parental tobacco use at age 14–15 years*

| Ever tried/used e-cigarettes | Current e-cigarette use | |||||

| n | % | P value | n | % | P value | |

| Smoking at age 14–15 years | ||||||

| Never | 364/1910 | 19.1 | 61/1910 | 3.2 | ||

| Occasionally | 50/147 | 34.0 | 11/147 | 7.5 | ||

| Daily | 39/64 | 60.9 | <0.001 | 18/64 | 28.1 | <0.001 |

| Use of snus at age 14–15 years | ||||||

| Never | 405/2035 | 19.9 | 76/2035 | 3.7 | ||

| Occasionally | 16/28 | 57.1 | 5/28 | 17.9 | ||

| Daily | 31/61 | 50.8 | <0.001 | 9/61 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| Parental smoking at age 14–15 years | ||||||

| Father smoker, no | 374/1835 | 20.4 | 69/1835 | 3.8 | ||

| yes | 72/253 | 28.5 | 0.003 | 20/253 | 7.9 | 0.002 |

| Mother smoker, no | 368/1832 | 20.1 | 73/1832 | 4.0 | ||

| yes | 76/256 | 29.7 | <0.001 | 16/256 | 6.3 | 0.093 |

*Individuals with missing answers in the individual questions about tobacco use and e-cigarette use were excluded from the analysis.

e-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

Figure 1.

Smoking habits among e-cigarette users. The bars represent all those who had ever tried e-cigarettes and all current e-cigarette users at age 19 years, respectively. Never smoker, never smoker at age 14–15 and 19 years; ever occasional smoker, occasional smoker at age 14–15 or 19 years but not a daily smoker; former smoker, either self-reported former smoker at age 19 years or being a non-smoker or occasional smoker at 14–15 years and non-smoker at 19 years; ever daily smoker, daily smoker at 14–15 or 19 years. E-cigarettes, electronic cigarettes.

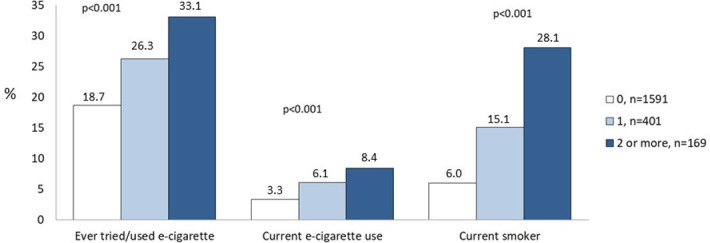

The prevalence of e-cigarette use, as well as current smoking at age 19 years, increased with increasing number of tobacco smoking family members (figure 2). Among those with two or more smoking family members, 33.1% had ever tried e-cigarettes and 8.4% were current users, compared with 18.7% and 3.3% among those with no smoking family members (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of ever and current e-cigarette use and current tobacco smoking at age 19 years in relation to number of smoking family members at age 14–15 years. E-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

Predictors of e-cigarette use

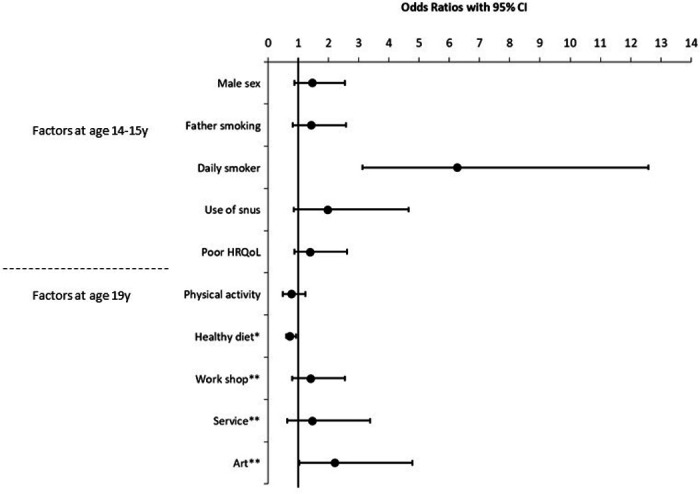

Unadjusted analyses are presented in the online supplemental table E1. Current e-cigarette use at age 19 years was associated with occasional and daily smoking, and use of snus at age 14–15 years. Further, it was associated with the vocational programmes of work shop, service and art using preparatory programmes as reference category. E-cigarette use was also associated with poor HRQoL, having a smoking father and inversely associated with physical activity and eating a healthy diet.

bmjopen-2020-040683supp001.pdf (121.2KB, pdf)

In the adjusted analyses, current e-cigarette use remained significantly associated with daily smoking (OR 6.27; 95% CI 3.12 to 12.58), the vocational programme of art (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.04 to 4.77) and inversely associated with eating a healthy diet (OR 0.74; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.92) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk factors for current e-cigarette use at age 19 years, analysed in an adjusted logistic regression analysis (including all factors listed in the figure) with the result expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. *Entered as a continuous variable (score 0–4); **upper secondary education, reference category: preparatory education. E-cigarette, electronic cigarette; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

In analyses stratified by sex, current e-cigarette use among the girls was associated with poor HRQoL at age 14–15 years (OR 2.92; 95% CI 1.25 to 6.81), the vocational programme of art (OR 3.13; 95% CI 1.17 to 8.34) and inversely associated with eating a healthy diet (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.91). Among the boys current e-cigarette use was significantly associated only with daily smoking (OR 5.37; 95% CI 1.94 to 14.84).

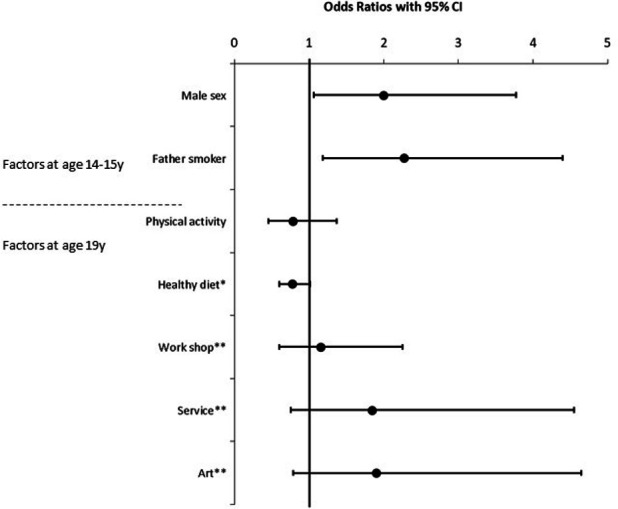

Predictors of e-cigarette use among non-tobacco users

Adjusted analyses were also performed among those who were never smokers and did not use snus at age 14–15 years, n=1827. Current e-cigarette use at age 19 years was associated with male sex (OR 2.00; 95% CI 1.06 to 3.77) and having a smoking father (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.19 to 4.39) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Risk factors for current e-cigarette use at age 19 years among the teenagers who were never smokers and did not use snus at age 14–15 years, analysed in an adjusted logistic regression analysis (including all factors listed in the figure) with the results expressed as ORs with 95% CIs. *Entered as a continuous variable (score 0–4); **upper secondary education, reference category: preparatory education. E-cigarette, electronic cigarette.

Analyses of representativeness

The sex distribution did not differ between participants (n=2185) and non-participants (n=634), male sex: 51.5% vs 54.6%, p=0.177. However, compared with the participants, the non-participants more often had a smoking mother (16.2% vs 26.7%, p<0.001), a smoking father (13.7% vs 21.3%, p<0.001), lived in a single-parent household (10.5% vs 19.7%, p<0.001) and reported having physician-diagnosed asthma (6.7% vs 10.4%, p=0.004) at recruitment. Further, a comparison between the n=2185 participants and the n=213 who participated at age 14–15 years but not at age 19 years showed a similar pattern in the characteristics.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, daily smoking, use of snus and having a smoking father at age 14–15 years predicted e-cigarette use at age 19 years. Furthermore, e-cigarette use was more common among boys and less common among teenagers who were physically active and ate a healthy diet. Among never smokers and non-snus users at age 14–15 years, male sex and having a smoking father predicted e-cigarette use at age 19 years. Importantly, almost one-third of those who had tried e-cigarettes at age 19 years had never been smokers.

Biologically, teenagers are particularly susceptible to nicotine addiction and it has been shown that occasional smoking at a young age is associated with greater likelihood of daily smoking and future nicotine dependence.37 38 Even occasional smoking is sufficient to develop abstinence symptoms38 and may increase the likelihood of trying new nicotine-delivery products out of curiosity.39 40 Thus, we were not surprised that smoking conventional cigarettes and using snus predicted e-cigarette use in our study. Although the prevalence of dual use was low, other studies have shown that the use of multiple tobacco and nicotine products has become more common particularly among young adults.41 The different properties and legislation of cigarettes, snus and e-cigarettes enable the user to choose product depending on the situation. We found that one-fifth of never smokers and never snus users, respectively, at age 14–15 years had tried e-cigarettes 4 years later. Moreover, almost one-third of e-cigarette users had never been a tobacco user, which is a cause for concern as it has been shown that e-cigarette use is a predictor of becoming a tobacco smoker.17 Finally, the teenagers in this cohort did not seem to use e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation method, as only one former smoker was a current e-cigarette user. Thus, due to the appeal of e-cigarettes among never smokers, our findings further undermine the claim that e-cigarettes are a useful harm-reduction product.

One explanation for the strong appeal of e-cigarettes to non-smoking teenagers may be the plethora of flavours, including fruits, sweets and desserts.42 43 In order to make e-cigarettes less appealing it has been suggested, for instance by the Food and Drug Administration in the USA that flavours other than tobacco, mint and menthol should be banned.44 The prominent taste of conventional cigarettes and most varieties of Swedish snus may avert teenagers from use. Consequently, e-cigarettes seem to appeal to new users that may not have initiated tobacco use otherwise, supporting the gateway theory.19

In line with other studies, we found that e-cigarette use was more common in boys than girls.23 24 45 One explanation may be that teenaged boys have a more risk-taking behaviour than girls and therefore are willing to try a new nicotine-delivery product. For a long time, tobacco smoking was more common among men than women in Sweden, but during the 1990s and 2000s it was more common among women.46 It may be that e-cigarette use follows the same pattern as the traditional tobacco epidemic, with a higher uptake among men in the beginning followed by an increase among women. Among teenagers, social role modelling may contribute to the choice of tobacco product as smoking is more common among mothers and daughters, while snus use is more common among fathers and sons.28 29 Unfortunately, we did not ask for parental e-cigarette use, but we did find that e-cigarette use was associated with having a smoking father and that it was more common the more family members who smoked, suggesting that parental smoking habits play an important role for e-cigarette uptake.

We did not find any associations with parental socioeconomic status, but e-cigarette use was more common among teenagers in vocational than preparatory upper secondary education. In Sweden, the vocational programmes mainly lead to jobs within the industry and service, while many attending preparatory programmes continue on to higher education. It is well known that smoking conventional cigarettes is associated with lower educational level, while studies of e-cigarette use have shown inconsistent results.14 47 Nevertheless, our results indicate that the associations between lower educational level and smoking conventional or electronic cigarettes seen among adults are present already in early teenage in the choice of education. Moreover, e-cigarette use was less common among the teenagers who were physically active and ate a healthy diet. Tobacco use, physical inactivity and unhealthy diet, as well as low educational level, are known risk factors for public health diseases, for instance cardiovascular disease, and regrettably, the same individuals often recur in all of these high-risk groups,48 49 in accordance with the common liability theory.19 25 Another interesting finding was that e-cigarette use was associated with poor HRQoL, particularly among the girls. An association between HRQoL and tobacco smoking has been demonstrated among teenagers.34 Thus, the predictors for e-cigarette use were to a large extent the same as for conventional cigarettes, which implies that the already available successful tobacco prevention measures only need minor modifications to also include e-cigarette use. Supporting teenagers to choose a healthy lifestyle without any tobacco or nicotine products is an important public health effort.

The strengths of the study include the prospective study design, with high initial participation rates and few individuals lost to follow-up. Among those lost to follow-up, there was a higher proportion of children having smoking parents than among those who participated in the survey at age 19 years. As having smoking parents and initiation of tobacco use in teenage are strongly correlated, we may have underestimated the prevalence of tobacco and e-cigarette use. On the other hand, most likely we have not overestimated the significance of the associations.50 Tobacco and e-cigarette use was based on self-reports and not verified by objective measures such as level of cotinine. However, the prevalence of smokers, snus and e-cigarette users was in line with the prevalence in corresponding ages reported in Swedish national surveys,4 supporting the external validity of our results. Questions about diet and physical activity were included in the questionnaire at age 19 years and thus represent cross-sectional associations with e-cigarette use. Another limitation is that the main focus of this cohort study is asthma and allergic diseases, and therefore we did not include questions about personality traits related to tobacco or nicotine product initiation, sensation-seeking behaviour, alcohol intake or other risk-taking behaviour in the questionnaire.

In conclusion, daily smoking, use of snus and having a smoking father at age 14–15 years predicted e-cigarette use at age 19 years. Furthermore, e-cigarette use was associated with male sex, physical inactivity, eating an unhealthy diet and attending vocational upper secondary education. Alarmingly, almost one-third of those who had tried e-cigarettes at age 19 years had never been smokers or used snus. Until the effects of e-cigarette use on respiratory and cardiovascular health have been fully elucidated, the rapid increase of e-cigarette use among teenagers needs to be curbed. In order to increase the efficacy of intervention efforts, the predictors and pattern of e-cigarette use among teenagers need to be studied in detail and our study contributes new knowledge in the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sigrid Sundberg, Ann-Christin Jonsson, Chatrin Wahlgren and Zandra Lundgren are acknowledged for data collection.

Footnotes

Twitter: @hedlin79

Contributors: LH participated in study design and data collection, performed the statistical analyses, drafted and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. HB, CS, ML and MA contributed to the analyses and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. ER is responsible for study conception and study design, participated in data collection, contributed to the analyses and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (20140264; 20170438; 20170696; 20180214), ALF—a regional agreement between Umeå University and Västerbotten County Council (RV-638731; RV-738451), the Swedish Asthma-Allergy Foundation (F2012-0036; F2012-0039), Visare Norr fund: Northern County Council’s Regional Federation (646191), and Norrbotten County Council (867371; 933163) are acknowledged for financial support.

Disclaimer: None of the funders had any role in study design, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Umeå, Sweden. At recruitment the parents gave consent for their child to participate. The participants gave written informed consent at the follow-up at 19 years.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Hammond D, Reid JL, Rynard VL, et al. Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: repeat national cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2019;365:l2219. 10.1136/bmj.l2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kapan A, Stefanac S, Sandner I, et al. Use of electronic cigarettes in European populations: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17061971. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bals R, Boyd J, Esposito S, et al. Electronic cigarettes: a task force report from the European respiratory Society. Eur Respir J 2019;53. 10.1183/13993003.01151-2018. [Epub ahead of print: 31 Jan 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and other drugs, (CAN) Skolelevers drogvanor 2019 (alcohol and drug use among students). Report number 187, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu Y, Guo Y, Liu K, et al. E-Cigarette awareness, use, and harm perception among adults: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165938. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glasser AM, Collins L, Pearson JL, et al. Overview of electronic nicotine delivery systems: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:e33–66. 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalkhoran S, Alvarado N, Vijayaraghavan M, et al. Patterns of and reasons for electronic cigarette use in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1122–9. 10.1007/s11606-017-4123-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control 2014;23:133–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams M, Villarreal A, Bozhilov K, et al. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PLoS One 2013;8:e57987. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeVito EE, Krishnan-Sarin S. E-Cigarettes: impact of E-Liquid components and device characteristics on nicotine exposure. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018;16:438–59. 10.2174/1570159X15666171016164430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ren M, Lotfipour S. Nicotine gateway effects on adolescent substance use. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:696–709. 10.5811/westjem.2019.7.41661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Lacy E, Fletcher A, Hewitt G, et al. Cross-Sectional study examining the prevalence, correlates and sequencing of electronic cigarette and tobacco use among 11-16-year olds in schools in Wales. BMJ Open 2017;7:e012784–012784. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tavolacci M-P, Vasiliu A, Romo L, et al. Patterns of electronic cigarette use in current and ever users among college students in France: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011344–011344. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hedman L, Backman H, Stridsman C, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with smoking habits, demographic factors, and respiratory symptoms. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e180789. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vardavas CI, Filippidis FT, Agaku IT. Determinants and prevalence of e-cigarette use throughout the European Union: a secondary analysis of 26 566 youth and adults from 27 Countries. Tob Control 2015;24:442–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li J, Newcombe R, Walton D. The prevalence, correlates and reasons for using electronic cigarettes among New Zealand adults. Addict Behav 2015;45:245–51. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:788–97. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Leventhal AM, et al. E-Cigarettes, cigarettes, and the prevalence of adolescent tobacco use. Pediatrics 2016;138. 10.1542/peds.2015-3983. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Jul 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Etter J-F. Gateway effects and electronic cigarettes. Addiction 2018;113:1776–83. 10.1111/add.13924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics 2015;136:308–17. 10.1542/peds.2015-0639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vogel EA, Ramo DE, Rubinstein ML. Prevalence and correlates of adolescents' e-cigarette use frequency and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;188:109–12. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cardenas VM, Breen PJ, Compadre CM, et al. The smoking habits of the family influence the uptake of e-cigarettes in US children. Ann Epidemiol 2015;25:60–2. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kinnunen JM, Ollila H, Minkkinen J, et al. A longitudinal study of predictors for adolescent electronic cigarette experimentation and comparison with conventional smoking. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. 10.3390/ijerph15020305. [Epub ahead of print: 09 Feb 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Babineau K, Taylor K, Clancy L. Electronic cigarette use among Irish youth: a cross sectional study of prevalence and associated factors. PLoS One 2015;10:e0126419. 10.1371/journal.pone.0126419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, et al. Common liability to addiction and "gateway hypothesis": theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;123 Suppl 1:S3–17. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim S, Selya AS. The relationship between electronic cigarette use and conventional cigarette smoking is largely attributable to shared risk factors. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1123–30. 10.1093/ntr/ntz157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leon ME, Lugo A, Boffetta P, et al. Smokeless tobacco use in Sweden and other 17 European countries. Eur J Public Health 2016;26:817–21. 10.1093/eurpub/ckw032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosendahl KI, Galanti MR, Gilljam H, et al. Smoking mothers and snuffing fathers: behavioural influences on youth tobacco use in a Swedish cohort. Tob Control 2003;12:74–8. 10.1136/tc.12.1.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hedman L, Bjerg A, Bjerg-Bäcklund A, et al. Factors related to tobacco use among teenagers. Respir Med 2007;101:496–502. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rönmark E, Bjerg A, Perzanowski M, et al. Major increase in allergic sensitization in schoolchildren from 1996 to 2006 in northern Sweden. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:357–63. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bjerg A, Sandström T, Lundbäck B, et al. Time trends in asthma and wheeze in Swedish children 1996-2006: prevalence and risk factors by sex. Allergy 2010;65:48–55. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bunne J, Moberg H, Hedman L, et al. Increase in allergic sensitization in schoolchildren: two cohorts compared 10 years apart. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5:e1:457–63. 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (Isaac): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J 1995;8:483–91. 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hedman L, Andersson M, Stridsman C, et al. Evaluation of a tobacco prevention programme among teenagers in Sweden. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007673–007673. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Rajmil L, et al. Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents' well-being and health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1487–500. 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Statistics Sweden Socio-Economic classification. MIS, 1982: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kendler KS, Myers J, Damaj MI, et al. Early smoking onset and risk for subsequent nicotine dependence: a monozygotic co-twin control study. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:408–13. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Siqueira LM, COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION . Nicotine and tobacco as substances of abuse in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20163436. 10.1542/peds.2016-3436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Margolis KA, Nguyen AB, Slavit WI, et al. E-Cigarette curiosity among U.S. middle and high school students: findings from the 2014 national youth tobacco survey. Prev Med 2016;89:1–6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kinnunen JM, Ollila H, Lindfors PL, et al. Changes in electronic cigarette use from 2013 to 2015 and reasons for use among Finnish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13. 10.3390/ijerph13111114. [Epub ahead of print: 09 Nov 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Osibogun O, Taleb ZB, Bahelah R, et al. Correlates of poly-tobacco use among youth and young adults: findings from the population assessment of tobacco and health study, 2013-2014. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;187:160–4. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patel D, Davis KC, Cox S, et al. Reasons for current e-cigarette use among U.S. adults. Prev Med 2016;93:14–20. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Publications Office of the European Union Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes: report; special Eurobarometer 458, 2018: 1–205. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2f01a3d1-0af2-11e8-966a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF [Google Scholar]

- 44. Drazen JM, Morrissey S, Campion EW. The dangerous flavors of e-cigarettes. N Engl J Med 2019;380:679–80. 10.1056/NEJMe1900484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Farsalinos KE, Poulas K, Voudris V, et al. Prevalence and correlates of current daily use of electronic cigarettes in the European Union: analysis of the 2014 Eurobarometer survey. Intern Emerg Med 2017;12:757–63. 10.1007/s11739-017-1643-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Backman H, Räisänen P, Hedman L, et al. Increased prevalence of allergic asthma from 1996 to 2006 and further to 2016-results from three population surveys. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:1426–35. 10.1111/cea.12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, et al. E-Cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob Control 2017;26:e85–91. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reas DL, Wisting L, Stedal K, et al. Unhealthy eating and weight dissatisfaction in adolescents who never, occasionally, or regularly use smokeless tobacco (Swedish snus). Int J Eat Disord 2019;52:846–54. 10.1002/eat.23085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Manuel DG, Perez R, Sanmartin C, et al. Measuring burden of unhealthy behaviours using a multivariable predictive approach: life expectancy lost in Canada attributable to smoking, alcohol, physical inactivity, and diet. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002082. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rönmark EP, Ekerljung L, Lötvall J, et al. Large scale questionnaire survey on respiratory health in Sweden: effects of late- and non-response. Respir Med 2009;103:1807–15. 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-040683supp001.pdf (121.2KB, pdf)