Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association of a high C-reactive protein (CRP) level at discharge from an acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) hospitalisation with the 1-year clinical outcomes.

Design

A post-hoc subanalysis of a prospective cohort study of patients hospitalised for ADHF (using the Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure (KCHF) registry) between October 2014 and March 2016 with a 1-year follow-up.

Setting

A physician-initiated multicentre registry enrolled consecutive hospitalised patients with ADHF for the first time at 19 secondary and tertiary hospitals in Japan.

Participants

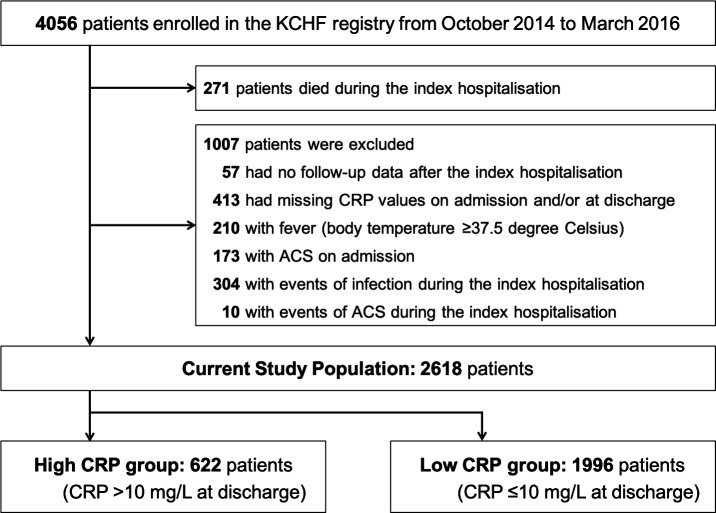

Among the 4056 patients enrolled in the KCHF registry, the present study population consisted of 2618 patients with an available CRP value both on admission and at discharge and post-discharge clinical follow-up data. We divided the patients into two groups, those with a high CRP level (>10 mg/L) and those with a low CRP level (≤10 mg/L) at discharge from the index hospitalisation.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was all-cause death after discharge from the index hospitalisation. The secondary outcome measures were heart failure hospitalisations, cardiovascular death and non-cardiovascular death.

Results

The high CRP group and low CRP group included 622 patients (24%) and 1996 patients (76%), respectively. During a median follow-up period of 468 days, the cumulative 1-year incidence of the primary outcome was significantly higher in the high CRP group than low CRP group (24.1% vs 13.9%, log-rank p<0.001). Even after a multivariable analysis, the excess mortality risk in the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group remained significant (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.71; p<0.001). The excess mortality risk was consistent regardless of the clinically relevant subgroup factors.

Conclusions

A high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation was associated with an excess mortality risk at 1 year.

Trial registration details

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02334891 (NCT02334891) https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000017241 (UMIN000015238).

Keywords: heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, adult cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was a large-scale, contemporary, multicentre, observational study clarifying the association of a high C-reactive protein (CRP) level at discharge from an acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) hospitalisation with the 1-year clinical outcomes.

The data for this study were prospectively collected from consecutive patients who were hospitalised due to ADHF in the real-world clinical practice in Japan.

This study examined whether a high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation was associated with an excess mortality risk at 1 year.

We could not fully address the effects of chronic inflammatory diseases such as autoimmune disease and malignancy on the clinical outcomes.

Introduction

The post-discharge mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) remains high and have not significantly improved over the past decade.1 The previous studies reported that the cumulative 1-year incidence of all-cause death in hospitalised patients with ADHF was approximately 20%, which was substantially higher than that in patients with chronic heart failure who remained free from ADHF hospitalisations.2 3 Thus, identification of patients with a high mortality risk is clinically relevant in hospitalised patients with ADHF.

The C-reactive protein (CRP) is a product of the liver regulated by cytokines, principally interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and activates the classical complement pathway and opsonises phagocytic ligands.4 5 The CRP has been established as a prognostic predictor of adverse events in patients with chronic heart failure,6–8 but has not been adequately established in patients with ADHF. Some previous studies have shown that high CRP levels on admission due to ADHF are associated with a high mortality after discharge;9–11 however, those results were affected by acute inflammatory responses such as a concomitant infection and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). On the other hand, the CRP level at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation might reflect a chronic inflammatory response and could be a more relevant prognostic predictor in hospitalised patients with ADHF. Thus, we aimed to examine the association of a high CRP level at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation with the 1-year clinical outcomes using a large contemporary all-comer study of patients with ADHF hospitalisations in Japan.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

The KCHF (Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure) registry was a physician-initiated, prospective, observational, multicentre cohort study enrolling consecutive patients who were hospitalised due to ADHF for the first time between October 2014 and March 2016, including patients with previous heart failure hospitalisations before October 2014. The participating centres were 19 secondary and tertiary hospitals, including rural and urban, as well as large and small institutions, in Japan. The design and patient enrolment in the KCHF registry were previously reported in detail.12 13 Briefly, we enrolled consecutive patients with ADHF as defined by the modified Framingham criteria, who were admitted to the participating hospitals and underwent heart failure-specific treatment requiring intravenous drugs within 24 hours after presenting to the hospitals. One-year clinical follow-up data were collected in October 2017. The attending physicians or research assistants at each participating hospital collected the clinical event data, including deaths and heart failure hospitalisations, during the follow-up from the hospital medical records or patients, their relatives or their referring physicians by phone and/or mailed questions.

Among the 4056 patients enrolled in the KCHF registry, 271 died during the index hospitalisation (figure 1). We excluded patients without data after the index hospitalisation (n=57), patients with missing CRP values on admission and/or at discharge (n=413), and those with a fever (n=210), ACS (n=173), infectious events during the index hospitalisation (n=304) and ACS events during the index hospitalisation (n=10). Finally, the present study population consisted of 2618 patients, including 1658 patients (63%) with first-ever heart failure hospitalisations, with an available CRP value both on admission and at discharge and post-discharge clinical follow-up data. According to the previously reported cut-off values,9 14 we divided the patients into two groups, those with a high CRP level (>10 mg/L) and those with a low CRP level (≤10 mg/L) at discharge from the index hospitalisation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CRP, C-reactive protein; KCHF, Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure.

Ethics

The investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committees at Kyoto University Hospital (local identifier: E2311) and at each participating hospital (online supplemental eAppendix 1). A waiver of written informed consent from each patient was approved, because it met the conditions included in the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies.12 13 No patients refused to participate in the study when contacted for follow-up.

bmjopen-2020-041068supp001.pdf (2MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or to interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Definitions

The CRP values were measured on admission and at discharge in each hospital using a normal-sensitivity or high-sensitivity assay. The CRP measurement in each hospital was standardised by the common reference interval developed by the Committee on Common Reference Intervals of the Japan Society of Clinical Chemistry.15 Fever was defined as a body temperature of >37.5 degree Celsius. Infection included viral infections, bacterial pneumonia, urinary tract infections, biliary tract infections, sepsis, unknown foci of the infections and other infections (online supplemental eTable 1). Heart failure was classified according to the baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) as that with a reduced LVEF (<40%) or preserved LVEF (≥40%). Anaemia was diagnosed if the value of the haemoglobin was <13 g/dL for men and <12 g/dL for women. The detailed definitions of the other patient characteristics are described in online supplemental eAppendix 2. The missing values are presented in online supplemental eTable 2.

The primary outcome measure in the present study was all-cause death after discharge from the index hospitalisation. Other outcome measures included heart failure hospitalisations, cardiovascular death and non-cardiovascular death. The causes of death were classified according to the VARC (Valve Academic Research Consortium) definitions,16 and were adjudicated by a clinical event committee.12 13 17 Death was regarded as cardiovascular in origin unless obvious non-cardiovascular causes could be identified. Cardiovascular death included death related to heart failure, acute myocardial infarctions, fatal ventricular arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death (SCD), other cardiac death, strokes, intracranial haemorrhages and other vascular death.17 SCD was defined as unexplained death of a previously stable patient, including fatal ventricular arrhythmias and cardiac arrest. Non-cardiovascular death included malignancy, infections, renal failure, liver failure, respiratory failure, bleeding and other causes.17 Heart failure hospitalisations were due to worsening heart failure, requiring intravenous drug therapy.12

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as the mean with the SD or median with the IQR based on their distribution. As for the patient characteristics, the categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test when appropriate; otherwise, the Fisher’s exact test was used. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on their distribution. The baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes including all-cause death, heart failure hospitalisations, cardiovascular death and non-cardiovascular death were compared between the high CRP and low CRP groups at discharge. We regarded the date of discharge as time zero for the clinical follow-up. The 1-year clinical follow-up was regarded as completed with an allowance of 1 month. Cumulative incidences were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and differences were assessed with the log-rank test. We constructed multivariable Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the risk of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group, with the results expressed as the HRs and 95% CIs. We included the following 25 clinically relevant risk-adjusting variables into the model: demographical variables (age ≥80 years, sex and body mass index (BMI) ≤22 kg/m2), variables related to heart failure (previous heart failure hospitalisation and LVEF <40% by echocardiography), variables related to comorbidities (atrial fibrillation or flutter, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, current smoking and chronic lung disease), living status (living alone and ambulatory), vital signs at presentation (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg and heart rate <60 bpm), laboratory tests on admission (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, albumin <3.0 g/dL, sodium <135 mEq/L and anaemia) and medications at discharge (ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, loop diuretics and tolvaptan) consistent with the previous reports,18–20 and history of malignancy as an additional variable into the model, as indicated in table 1. The continuous variables were dichotomised by clinically meaningful reference values or median values. To account for the competing risk of all-cause death, we used the Fine and Gray’s method to estimate the risk for heart failure hospitalisations in the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group. As sensitivity analyses, we constructed three additional multivariable Cox proportional hazard models. First, we set a lower cut-off value for the CRP, and estimated the risk of the group with a CRP level >3 mg/L relative to the group with a CRP level ≤3 mg/L for the primary outcome measure. Second, we excluded those patients with very high CRP levels (>50 mg/L) and estimated the risk of the high CRP group (CRP >10 mg/L) relative to the low CRP group (CRP ≤10 mg/L) for the primary outcome measure. Finally, based on the quartile of the CRP levels at discharge, we divided the entire cohort into four groups: Quartile 1 (≤1.3 mg/L), Quartile 2 (1.4 to 3.5 mg/L), Quartile 3 (3.6 to 9.5 mg/L) and Quartile 4 (≥9.6 mg/L). We compared the clinical outcomes across the CRP quartiles, and estimated the risk of Quartile 2, Quartile 3 and Quartile 4, relative to Quartile 1 for the primary outcome measure. In the post-hoc subgroup analysis, we evaluated the interaction between those subgroup factors such as the age, coronary artery disease and LVEF at baseline, and the risk of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group for the primary outcome measure in the Cox models. All statistical analyses were performed with EZR software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) or JMP V.14.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Two tailed p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Total (n=2618) | High CRP group CRP >10 mg/L (n=622) |

Low CRP group CRP ≤10 mg/L (n=1996) |

P value | |

| CRP at discharge, mg/L | 3.6 (1.4 to 9.6) | 19.6 (13.4 to 31.9) | 2.1 (1.0 to 4.9) | <0.001 |

| Lowest and highest decile, mg/L | 0.6 to 22.0 | 11.3 to 55.7 | 0.5 to 7.4 | |

| Delta CRP†, mg/L | 7.5±31.1 | −0.05±44.9 | 9.9±24.8 | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 15 (11 to 22) | 15 (10 to 23) | 15 (11 to 22) | 0.29 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 77.6±12.1 | 79.4±10.9 | 77.0±12.3 | <0.001 |

| ≥80 years* | 1354 (52%) | 354 (57%) | 1000 (50%) | 0.003 |

| Women* | 1186 (45%) | 240 (39%) | 946 (47%) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9±4.5 | 22.8±4.4 | 22.9±4.6 | 0.46 |

| ≤22 kg/m2* | 1161 (46%) | 263 (45%) | 898 (47%) | 0.55 |

| Aetiology | <0.001 | |||

| Coronary artery disease excluding ACS | 728 (28%) | 194 (31%) | 534 (27%) | |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 698 (27%) | 163 (26%) | 535 (27%) | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 442 (17%) | 76 (12%) | 366 (18%) | |

| Valvular heart disease | 532 (20%) | 130 (21%) | 402 (20%) | |

| Other heart disease | 65 (2.5%) | 24 (3.9%) | 41 (2.1%) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Previous heart failure hospitalisation* | 960 (37%) | 215 (35%) | 745 (38%) | 0.25 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter* | 1162 (44%) | 251 (40%) | 911 (46%) | 0.02 |

| Hypertension* | 1891 (72%) | 463 (74%) | 1428 (72%) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 936 (36%) | 228 (37%) | 708 (35%) | 0.59 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1010 (39%) | 244 (39%) | 766 (38%) | 0.70 |

| Previous myocardial infarction* | 584 (22%) | 155 (25%) | 429 (21%) | 0.07 |

| Previous stroke* | 414 (16%) | 110 (18%) | 304 (15%) | 0.14 |

| Previous PCI or CABG | 682 (26%) | 187 (30%) | 495 (25%) | 0.009 |

| Current smoking* | 324 (13%) | 80 (13%) | 244 (12%) | 0.60 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1153 (44%) | 302 (49%) | 851 (43%) | 0.009 |

| Chronic lung disease* | 345 (13%) | 105 (17%) | 240 (12%) | 0.002 |

| Malignancy* | 385 (15%) | 93 (15%) | 292 (15%) | 0.84 |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 468 (18%) | 132 (21%) | 336 (17%) | 0.01 |

| Social backgrounds | ||||

| Poor medical adherence | 458 (17%) | 108 (17%) | 350 (18%) | 0.92 |

| Living alone* | 563 (22%) | 118 (19%) | 445 (22%) | 0.08 |

| With occupation | 343 (13%) | 72 (12%) | 271 (14%) | 0.20 |

| Public financial assistance | 150 (5.7%) | 33 (5.3%) | 117 (5.9%) | 0.60 |

| Daily life activities | <0.001 | |||

| Ambulatory* | 2083 (80%) | 457 (74%) | 1626 (82%) | |

| Use of wheelchair, outdoor only | 189 (7.3%) | 56 (9.1%) | 133 (6.7%) | |

| Use of wheelchair, outdoor and indoor | 232 (8.9%) | 78 (13%) | 154 (7.8%) | |

| Bedridden | 90 (3.5%) | 25 (4.1%) | 65 (3.3%) | |

| Vital signs at presentation | ||||

| BP, mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic BP | 149±35 | 150±36 | 148±35 | 0.37 |

| <90 mm Hg* | 60 (2.3%) | 17 (2.7%) | 43 (2.2%) | 0.40 |

| Diastolic BP | 86±24 | 86±25 | 86±24 | 0.83 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 95±28 | 94±28 | 96±28 | 0.29 |

| <60 bpm* | 194 (7.5%) | 54 (8.8%) | 140 (7.1%) | 0.16 |

| Rhythms at presentation | 0.41 | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 1392 (53%) | 344 (55%) | 1048 (53%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 1018 (39%) | 234 (38%) | 784 (39%) | |

| Other rhythms | 208 (7.9%) | 44 (7.1%) | 164 (8.2%) | |

| NYHA class III or IV | 2259 (87%) | 547 (88%) | 1712 (86%) | 0.14 |

| Laboratory tests on admission | ||||

| LVEF, % | 46±16 | 46±16 | 46±17 | 0.83 |

| <40%* | 962 (38%) | 236 (39%) | 726 (37%) | 0.54 |

| ≥40% | 1598 (62%) | 375 (61%) | 1223 (63%) | |

| BNP, pg/mL | 707 (389 to 1218) | 749 (414 to 1302) | 693 (384 to 1192) | 0.09 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 5312 (2642 to 12 149) | 5638 (2814 to 16 398) | 5146 (2618 to 11 318) | 0.29 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.10 (0.82 to 1.59) | 1.12 (0.84 to 1.79) | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.54) | 0.004 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 47±23 | 45±24 | 47±23 | 0.03 |

| <30 mL/min/1.73m2* | 687 (26%) | 194 (31%) | 493 (25%) | 0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 23 (17 to 34) | 26 (19 to 36) | 23 (17 to 33) | ≤0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.5±0.5 | 3.4±0.5 | 3.5±0.5 | <0.001 |

| <3.0 g/dL* | 309 (12%) | 111 (18%) | 198 (10%) | <0.001 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 139±4.1 | 139±4.3 | 139±4.1 | 0.009 |

| <135 mEq/L* | 285 (11%) | 80 (13%) | 205 (10%) | 0.07 |

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 11.6±2.3 | 11.4±2.3 | 11.7±2.4 | 0.007 |

| Anaemia*‡ | 1710 (65%) | 435 (70%) | 1275 (64%) | 0.005 |

| CRP, mg/L | 5.0 (2.0 to 15) | 13 (3.9 to 33) | 4.0 (1.7 to 11) | <0.001 |

| >10 mg/L | 893 (34%) | 353 (57%) | 540 (27%) | <0.001 |

| Medications at discharge | ||||

| ACEIs or ARBs* | 1525 (58%) | 332 (53%) | 1193 (60%) | 0.005 |

| β-blockers* | 1768 (68%) | 413 (66%) | 1355 (68%) | 0.49 |

| Loop diuretics* | 2175 (83%) | 501 (81%) | 1674 (84%) | 0.054 |

| Thiazide | 155 (5.9%) | 33 (5.3%) | 122 (6.1%) | 0.46 |

| Tolvaptan* | 259 (9.9%) | 67 (11%) | 192 (9.6%) | 0.40 |

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as the mean±SD, or the median (IQR) based on their distributions. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on their distribution.

Missing values were presented in online supplemental eTable 2.

*Risk-adjusting variables selected for multivariable Cox proportional hazard models.

†Delta CRP levels were calculated according to the following equation: (the CRP levels on admission) – (the CRP levels at discharge).

‡Anaemia was defined by the WHO criteria (haemoglobin <12.0 g/dL in women and 13.0 g/dL in men).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BNP, brain-type natriuretic peptide; BP, blood pressure; bpm, beat per minute; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal-proBNP; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data sharing statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. No additional data available.

Results

Patient characteristics

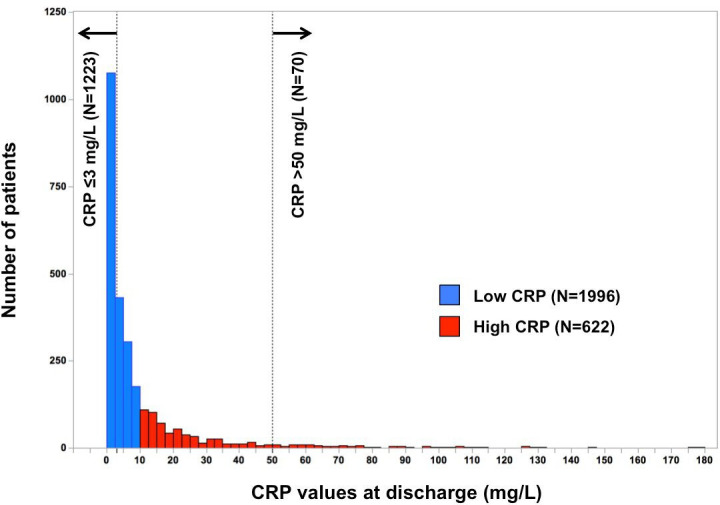

In the present study population, the median CRP level at discharge in the entire study population was 3.6 (IQR, 1.4 to 9.6) mg/L (figure 2). The high CRP group (CRP >10 mg/L) and low CRP group (CRP ≤10 mg/L) included 622 patients (24%) and 1996 patients (76%), respectively (figure 1). The baseline characteristics were significantly different in several aspects between the high and low CRP groups (table 1). Patients in the high CRP group were older, less frequently women, and more frequently had coronary artery disease excluding ACS, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, dementia, high blood urea nitrogen levels, low albumin levels, hyponatraemia and anaemia than those in the low CRP group. On the other hand, the patients in the low CRP group more frequently had an ambulatory status and the use of ACEIs or ARBs at discharge (table 1).

Figure 2.

Distribution of the CRP values at discharge. CRP, C-reactive protein.

Clinical outcomes

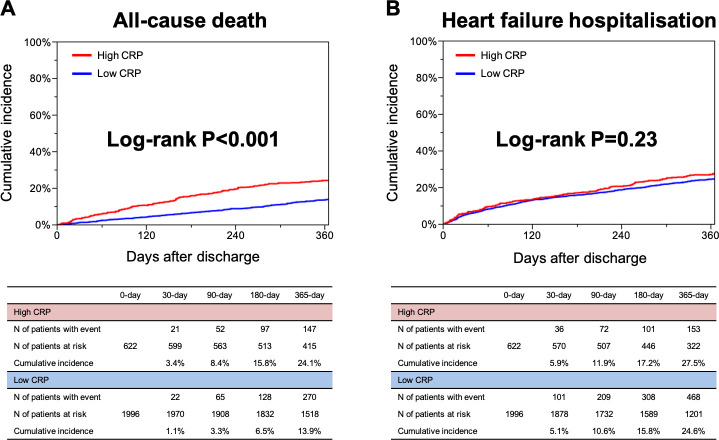

The median length of the follow-up was 468 (IQR, 362 to 637) days, with a 95.8% follow-up rate at 1 year. The cumulative 1-year incidence of the primary outcome measure (all-cause death after discharge) was significantly higher in the high CRP group than low CRP group (24.1% vs 13.9%, p<0.001) (figure 3A). After a multivariable analysis, the excess risk of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group remained significant for all-cause death (adjusted HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.19 to 1.71; p<0.001) (table 2). The excess adjusted risks of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group were also significant for cardiovascular death and non-cardiovascular death (adjusted HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.65; p=0.03, and adjusted HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.21 to 2.12; p<0.001, respectively) (table 2). The cumulative 1-year incidence of a heart failure hospitalisation after discharge was not different between the high and low CRP groups (27.5% vs 24.6%, p=0.23) (figure 3B). Even after a multivariable analysis, the risk of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group remained insignificant for a heart failure hospitalisation (adjusted HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.25; p=0.63) (table 2). Even after taking into account the competing risk of all-cause death, the cumulative 1-year incidence of a heart failure hospitalisation was not different between the high and low CRP groups (25.0% vs 23.8%, p=0.73) (online supplemental eFigure 1), and the adjusted risk of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group remained insignificant for a heart failure hospitalisation (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.80 to 1.16; p=0.69) (online supplemental eTable 3). The details of the causes of death in the high and low CRP groups are presented in table 3.

Figure 3.

The Kaplan-Meier curves (A) for all-cause death after discharge compared between the high CRP group (CRP >10 mg/L at discharge) versus low CRP group (CRP ≤10 mg/L at discharge), and (B) for heart failure hospitalisations after discharge compared between the high CRP group (CRP >10 mg/L at discharge) versus low CRP group (CRP ≤10 mg/L at discharge). CRP, C-reactive protein.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

| High CRP group CRP >10 mg/L (n=622) N of patients with event (cumulative 1-year incidence) |

Low CRP group CRP ≤10 mg/L (n=1996) N of patients with event (cumulative 1-year incidence) |

Crude HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| All-cause death | 190 (24.1%) | 391 (13.9%) | 1.75 (1.47 to 2.07) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.19 to 1.71) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular death | 107 (14.4%) | 247 (9.0%) | 1.56 (1.24 to 1.95) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.03 to 1.65) | 0.03 |

| Non-cardiovascular death | 83 (11.3%) | 144 (5.3%) | 2.07 (1.58 to 2.71) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.21 to 2.12) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure hospitalisation | 170 (27.5%) | 537 (24.6%) | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.32) | 0.24 | 1.04 (0.88 to 1.25) | 0.63 |

Number of patients with event was counted throughout the entire follow-up period because we used the Cox proportional hazard models which provided the HRs between the high and low CRP groups over the entire study duration, while the cumulative incidence was estimated at 1 year. The crude and adjusted HRs and 95% CIs of the high CRP group for the clinical outcome measures were estimated by the Cox proportional hazard models using the low CRP group as the reference. To adjust for potential confounders, we selected 25 clinically relevant confounders as indicated in table 1.

CRP, C-reactive protein.;

Table 3.

Causes of death compared between the high CRP group versus low CRP group during entire follow-up period

| Total N of patients with death (proportion among total death) |

High CRP group CRP >10 mg/L N of patients with death (proportion among total death) |

Low CRP group CRP ≤10 mg/L N of patients with death (proportion among total death) |

|

| All-cause death | 581 | 190 | 391 |

| Cardiovascular death | 367 (63%) | 111 (58%) | 256 (66%) |

| Heart failure death | 229 (39%) | 68 (36%) | 161 (41%) |

| Sudden cardiac death | 70 (12%) | 23 (12%) | 47 (12%) |

| Vascular death | 8 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (2.0%) |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 6 (1.0%) | 3 (1.6%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| Stroke or intracranial haemorrhage | 28 (4.8%) | 8 (4.2%) | 20 (5.1%) |

| Other cardiovascular death | 26 (4.5%) | 9 (4.7%) | 17 (4.3%) |

| Non-cardiovascular death | 212 (36%) | 79 (42%) | 133 (34%) |

| Malignancy | 48 (8.3%) | 19 (10%) | 29 (7.4%) |

| Infection | 76 (13%) | 27 (14%) | 49 (13%) |

| Fatal bleeding | 6 (1.0%) | 3 (1.6%) | 3 (0.8%) |

| Other gastrointestinal cause | 6 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 5 (1.3%) |

| Renal failure | 12 (2.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 10 (2.6%) |

| Liver failure | 5 (0.9%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| Respiratory failure | 22 (3.8%) | 9 (4.7%) | 13 (3.3%) |

| Other non-cardiovascular death | 37 (6.4%) | 15 (7.9%) | 22 (5.6%) |

| Unknown cause of death | 2 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.5%) |

Number of patients with death was counted throughout the entire follow-up period because we used the Cox proportional hazard models, which provided the HRs between the high and low CRP groups over the entire study duration.

CRP, C-reactive protein.

Sensitivity analysis

Even when we divided the patients into two groups of patients according to a CRP level of 3 mg/L (online supplemental eTable 4), the excess crude and adjusted risks in the CRP >3 mg/L group relative to the CRP ≤3 mg/L group for the primary outcome measure remained significant (adjusted HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.75; p<0.001) (online supplemental eTable 5). In addition, even after excluding the patients with a CRP level >50 mg/L (n=2548, online supplemental eTable 6), the excess crude and adjusted risks in the high CRP group (CRP >10 mg/L) relative to the low CRP group (CRP ≤10 mg/L) for the primary outcome measure remained significant (adjusted HR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.65; p=0.001) (online supplemental eTable 7). When we divided the entire cohort into four groups based on the quartile of the CRP levels at discharge, the cumulative 1-year incidence of the primary outcome measure increased incrementally from Quartile 1 to Quartile 4 (Quartile 1: 10.5%, Quartile 2: 12.9%, Quartile 3: 17.8% and Quartile 4: 23.7%, p<0.001) (online supplemental eFigure 2). Even after a multivariable analysis, the excess risk of Quartile 4 relative to Quartile 1 remained significant for the primary outcome measure (adjusted HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.51 to 2.52; p<0.001) (online supplemental eTable 8). The cumulative 1-year incidence of heart failure hospitalisations after discharge was not different across the CRP quartiles (23.4%, 23.1%, 27.4% and 27.3%, p=0.25) (online supplemental eFigure 2). Even after the multivariable analysis, the risk of Quartile 4 relative to Quartile 1 remained insignificant for heart failure hospitalisations (adjusted HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.29; p=0.71) (online supplemental eTable 8).

Subgroup analysis

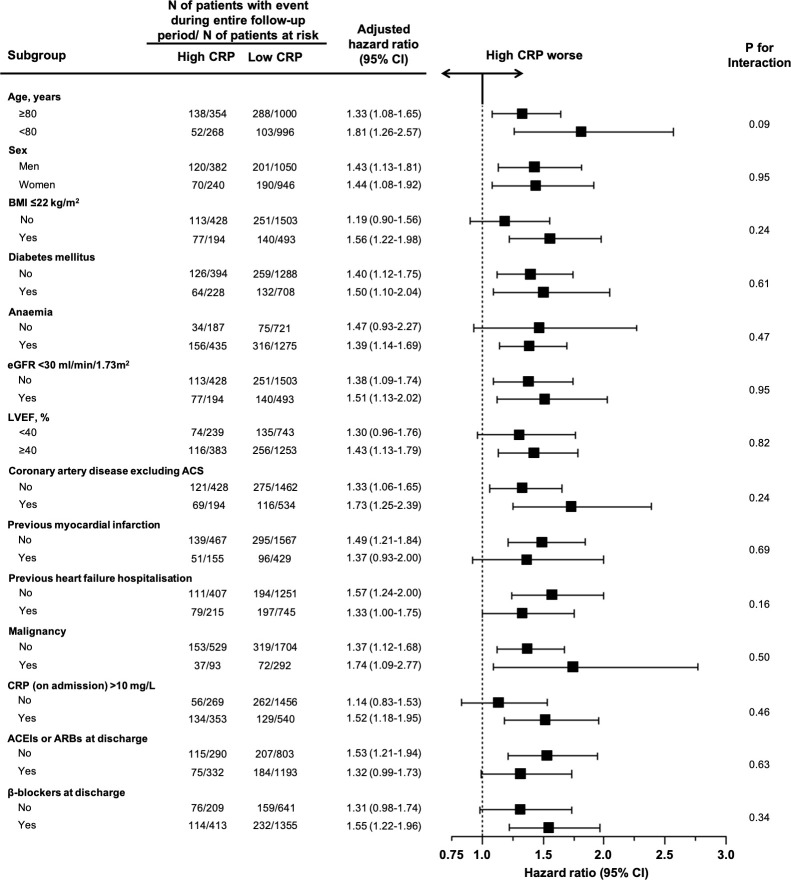

We conducted subgroup analyses stratified by the age, sex, BMI, diabetes mellitus, anaemia, renal dysfunction, LVEF, coronary artery disease excluding ACS, previous myocardial infarction, previous heart failure hospitalisation, malignancy, elevated CRP level (>10 mg/L) on admission, use of ACEIs or ARBs at discharge and use of β-blockers at discharge (figure 4). The CRP level at discharge was higher in the elderly patients (≥80 years), men, and patients with anaemia, renal dysfunction (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2), coronary artery disease excluding ACS, previous heart failure hospitalisations, elevated CRP levels on admission and the use of the ACEIs or ARBs at discharge (online supplemental eTable 9). The CRP level at discharge was not different regardless of a reduced or preserved LVEF (online supplemental eTable 9). An excess adjusted risk in the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group for the primary outcome measure was consistently seen across all the subgroups (figure 4). There were no significant interactions between the subgroup factors and effect of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group for the primary outcome measure (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis for the associations of the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group with all-cause deaths after discharge. Anaemia was defined by the WHO criteria (haemoglobin <12.0 g/dL in women and 13.0 g/dL in men). ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricularejection fraction.

Discussion

The main findings of the present study were as follows: (1) the high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge from the index hospitalisation for ADHF was associated with an excess adjusted risk for all-cause death at 1 year; (2) the excess mortality risk in the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group was consistent in all the clinically relevant subgroups; and (3) there was no significant excess risk for heart failure hospitalisations in the high CRP group compared with the low CRP group.

A high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge from the ADHF hospitalisation was a simple predictor of the 1-year mortality, which might have been partly due to the underlying inflammation that could not be controlled by classical ADHF therapies. Unfortunately, previous studies have failed to demonstrate the efficacy of heart failure-specific treatments targeting inflammation, such as a targeted anticytokine therapy using a TNF-α antagonist,21 immune modulation therapy22 and statin therapy,23 in chronic heart failure. However, a recent randomised controlled trial suggested that an IL-1β inhibitor dose-dependently reduced heart failure hospitalisations and the composite of heart failure hospitalisations or heart failure-related mortality in patients with a previous myocardial infarction and elevated high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP) levels.24 In the setting of ADHF, patients are haemodynamically unstable with marked congestion, which leads to bowel oedema and overgrowth of bacteria flora, resulting in inflammation.25 Precipitating inflammation or an infection triggers a haemodynamic collapse due to an increased oxygen demand and surge in the blood pressure in a substantial proportion of patients with ADHF.26 Thus, the elevated CRP levels at discharge may reflect a prolonged inflammatory response despite the treatment for ADHF. The efficacy of the therapies to block the upstream inflammation in ADHF has not yet been evaluated, and further study on this topic is warranted.

There is a paucity of data on the association of the CRP level at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation with the clinical outcomes. A previous study reported that a high CRP level (≥9.5 mg/L) at discharge was associated with an excess adjusted risk for mortality within 120 days; however, this excess risk in the high CRP level patients (≥9.5 mg/L) decreased markedly with time.14 Instead, a modestly elevated CRP level (1.2 to 9.5 mg/L) was associated with an excess adjusted risk for mortality in the long-term follow-up beyond 120 days (median, 510 (IQR, 381 to 765) days).14 Another previous study reported that the cumulative 3-month incidence of deaths or heart failure hospitalisations was significantly high for a high CRP level (>12.3 mg/L, upper third) at discharge in ADHF patients without a concomitant infection but not in those with a concomitant infection,27 however, this was not explicitly adjusted for the confounders. In the present study, a high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge was clearly associated with an excess adjusted mortality risk at 1 year in ADHF patients in whom a concomitant infection was excluded as much as possible. Several previous studies have suggested that circulating elevated levels of cytokines and cytokine receptors predict a worse clinical outcome in patients with heart failure.28 29 Further, a previous study demonstrated that cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) and their receptors were independent predictors of mortality in patients with advanced heart failure.30 IL-6 works between the upstream of CRP and downstream of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and the CRP values are easier to measure than both IL-6 and IL-1β. Therefore, the high CRP level could be a more relevant prognostic predictor in patients with heart failure.

The excess mortality risk in patients with a high CRP at discharge was consistent in all the clinically relevant subgroups. There is a paucity and inconsistency of data of the difference in the CRP levels between ADHF patients with a reduced LVEF and those with a preserved LVEF.11 31 A previous study reported that a decrease of at least 40% in the hsCRP during hospitalisations (hsCRP levels on admission minus those at discharge) was associated with a low adjusted risk for mortality at 3 years in ADHF patients with a preserved LVEF, but not in those with a reduced LVEF.32 In the present study, the CRP levels at discharge were not different regardless of a reduced or preserved LVEF. Furthermore, the excess mortality risk in patients with a high CRP at discharge was consistent regardless of a reduced or preserved LVEF, suggesting that the CRP levels on admission might have a different meaning between ADHF patients with a reduced LVEF and those with a preserved LVEF considering the previous report.32 Regarding the CRP levels on admission, the excess mortality risk in patients with a high CRP at discharge was consistent regardless of an elevated CRP level on admission. Consistent with the previous studies,33 34 the CRP levels at discharge were higher in the elderly patients and patients with coronary artery disease. However, the excess mortality risk in patients with a high CRP at discharge was consistent regardless of the age and presence of coronary artery disease. Thus, the high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge was a prognostic predictor across the wide spectrum of patients with ADHF.

There was no significant excess risk for heart failure hospitalisations in the high CRP group compared with the low CRP group. The association between the CRP levels and severity of systolic dysfunction or symptoms was controversial.6 35 In the present study, there was no significant difference in the proportion of a low LVEF or New York HeartAssociation (NYHA) class III/IV between the high and low CRP groups (table 1). These findings suggest that the association of the elevated CRP levels at discharge from ADHF hospitalisations with the mortality risk at 1 year might not reflect the severity of the systolic dysfunction or symptoms.

Study limitations

The present study had several limitations. First, we used the CRP values measured in each hospital using a normal-sensitivity or high-sensitivity assay, because the present study was based on an observational cohort study in daily clinical practice. This may have caused variability in the measurement of the CRP levels and might have led to an inconsistent classification of the high and low CRP groups. Second, we could not fully address the effects of chronic inflammatory diseases such as autoimmune disease and malignancy on the clinical outcomes. Thus, we conducted subgroup analyses stratified by malignancy, in which we did not find any significant interaction between malignancy and the excess mortality risk in patients with a high CRP. Third, we excluded patients with infections using the body temperature and physician’s judgement as much as possible. However, there was the possibility of a concomitant infection due to the complex nature of the infection. For example, we could not completely exclude patients who presented without a fever but still had a suspicion of an infection. Fourth, several subgroup analyses had the risk of a multiple comparison as well as a small sample size with a low statistical power. Finally, it is not clear how we could apply the present study findings in clinical practice.

Conclusions

A high CRP level (>10 mg/L) at discharge from an ADHF hospitalisation was associated with an excess mortality risk at 1 year.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support and collaboration of the co-investigators participating in the KCHF Registry. We also would like to express our gratitude to Mr John Martin for his grammatical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: YNi and TKat had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: YNi, TKat, TMorim, HY, YI, YT, EY, YY, TKit, RT, MIg, MKat, MTa, TJ, TI, KN, TKaw, AK, RN, YK, TMorin, KS, MKaw, YSe, MIn, MTo, YSa and TKim. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: YNi, TKat, HY, YI, YT, EY, YY, TKit, RT, MIg, MKat, MTa, TJ, TI, KN, TKaw, AK, RN, YK, TMorin, KS, MKaw, YSe, MIn, MTo, YF, YNa, KA, KKa, SS, KO, KKu, NO and YSa. Drafting of the manuscript: YNi, TKat, HY and TKim. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: YNi, TKat, HY, TKit and TKim. Statistical analysis: YNi, TKat and TMorim. Administrative, technical or material support: TKat, YSa and TKim. Supervision: TKat, TMorim, HY, YF, YNa, KA, KKa, SS, KO, KKu, NO, YSa and TKim.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (18059186) to TKat, KKu and NO. The founder had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: E2311), Shiga General Hospital (approval number: 20141120-01), Tenri Hospital (approval number: 640), Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital (approval number: 14094), Hyogo Prefectural Amagasaki General Medical Center (approval number: Rinri 26-32), National Hospital Organisation Kyoto Medical Center (approval number: 14-080), Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital (approved 11/12/2014), Okamoto Memorial Hospital (approval number: 201503), Japanese Red Cross Otsu Hospital (approval number: 318), Hikone Municipal Hospital (approval number: 26-17), Japanese Red Cross Osaka Hospital (approval number: 392), Shimabara Hospital (approval number: E2311), Kishiwada City Hospital (approval number: 12), Kansai Electric Power Hospital (approval number: 26-59), Shizuoka General Hospital (approval number: Rin14-11-47), Kurashiki Central Hospital (approval number: 1719), Kokura Memorial Hospital (approval number: 14111202), Kitano Hospital (approval number: P14-11-012) and Japanese Red Cross Wakayama Medical Center (approval number: 328). A waiver of written informed consent from each patient was granted by the institutional review boards of Kyoto University and each participating centre.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. No additional data available.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Kurmani S, Squire I. Acute heart failure: definition, classification and epidemiology. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2017;14:385–92. 10.1007/s11897-017-0351-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, et al. EURObservational research programme: regional differences and 1-year follow-up results of the heart failure pilot survey (ESC-HF Pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:808–17. 10.1093/eurjhf/hft050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavazzi L, Senni M, Metra M, et al. Multicenter prospective observational study on acute and chronic heart failure: one-year follow-up results of IN-HF (Italian network on heart failure) outcome registry. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:473–81. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendall MA, Patel P, Asante M, et al. Relation of serum cytokine concentrations to cardiovascular risk factors and coronary heart disease. Heart 1997;78:273–7. 10.1136/hrt.78.3.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anker SD, von Haehling S. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure: an overview. Heart 2004;90:464–70. 10.1136/hrt.2002.007005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand IS, Latini R, Florea VG, et al. C-reactive protein in heart failure: prognostic value and the effect of valsartan. Circulation 2005;112:1428–34. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.508465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windram JD, Loh PH, Rigby AS, et al. Relationship of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein to prognosis and other prognostic markers in outpatients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2007;153:1048–55. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellicori P, Zhang J, Cuthbert J, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in chronic heart failure: patient characteristics, phenotypes, and mode of death. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:91–100. 10.1093/cvr/cvz198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso-Martínez JL, Llorente-Diez B, Echegaray-Agara M, et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of improvement and readmission in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2002;4:331–6. 10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00021-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siirilä-Waris K, Lassus J, Melin J, et al. Characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of 1-year mortality in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Eur Heart J 2006;27:3011–7. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minami Y, Kajimoto K, Sato N, et al. C-reactive protein level on admission and time to and cause of death in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2017;3:148–56. 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcw054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto E, Kato T, Ozasa N, et al. Kyoto congestive heart failure (KCHF) study: rationale and design. ESC Heart Fail 2017;4:216–23. 10.1002/ehf2.12138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaku H, Ozasa N, Morimoto T, et al. Demographics, management, and in-hospital outcome of hospitalized acute heart failure syndrome patients in contemporary real clinical practice in japan- observations from the prospective, multicenter kyoto congestive heart failure (KCHF) registry. Circ J 2018;82:2811–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minami Y, Kajimoto K, Sato N, et al. Effect of elevated C-reactive protein level at discharge on long-term outcome in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2018;121:961–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichihara K, Yomamoto Y, Hotta T, et al. Collaborative derivation of reference intervals for major clinical laboratory tests in Japan. Ann Clin Biochem 2016;53:347–56. 10.1177/0004563215608875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the valve academic research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1438–54. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitai T, Miyakoshi C, Morimoto T, et al. Mode of death among Japanese adults with heart failure with preserved, Midrange, and reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e204296. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su K, Kato T, Toyofuku M, et al. Association of previous hospitalization for heart failure with increased mortality in patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation Reports 2019;1:517–24. 10.1253/circrep.CR-19-0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaku H, Kato T, Morimoto T, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of functional decline during hospitalisation in very old patients with acute decompensated heart failure: an observational study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e032674. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaku H, Kato T, Morimoto T, et al. Association of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist use with all-cause mortality and hospital readmission in older adults with acute decompensated heart failure. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e195892. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann DL, McMurray JJV, Packer M, et al. Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the randomized etanercept worldwide evaluation (renewal). Circulation 2004;109:1594–602. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124490.27666.B2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torre-Amione G, Anker SD, Bourge RC, et al. Results of a non-specific immunomodulation therapy in chronic heart failure (ACCLAIM trial): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet 2008;371:228–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60134-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:1231–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61240-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Everett BM, Cornel JH, Lainscak M, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with canakinumab for the prevention of hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2019;139:1289–99. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentova M, von Haehling S, Bauditz J, et al. Intestinal congestion and right ventricular dysfunction: a link with appetite loss, inflammation, and cachexia in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1684–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arrigo M, Gayat E, Parenica J, et al. Precipitating factors and 90-day outcome of acute heart failure: a report from the intercontinental great registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:201–8. 10.1002/ejhf.682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lourenço P, Paulo Araújo J, Paulo C, et al. Higher C-reactive protein predicts worse prognosis in acute heart failure only in noninfected patients. Clin Cardiol 2010;33:708–14. 10.1002/clc.20812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrari R, Bachetti T, Confortini R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor soluble receptors in patients with various degrees of congestive heart failure. Circulation 1995;92:1479–86. 10.1161/01.CIR.92.6.1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsutamoto T, Hisanaga T, Wada A, et al. Interleukin-6 spillover in the peripheral circulation increases with the severity of heart failure, and the high plasma level of interleukin-6 is an important prognostic predictor in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:391–8. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00494-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, et al. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (vest). Circulation 2001;103:2055–9. 10.1161/01.cir.103.16.2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tromp J, Khan MAF, Klip IJsbrandT, et al. Biomarker profiles in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6 10.1161/JAHA.116.003989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lourenço P, Pereira J, Ribeiro A, et al. C-reactive protein decrease associates with mortality reduction only in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Cardiovasc Med 2019;20:23–9. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosa GM, Scagliola R, Ghione P, et al. Predictors of cardiovascular outcome and rehospitalization in elderly patients with heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 2019;49:e13044. 10.1111/eci.13044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiuchi S, Hisatake S, Kabuki T, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index and C-reactive protein are useful parameters for identification of ischemic heart disease in acute heart failure patients. J Clin Med Res 2017;9:439–45. 10.14740/jocmr2994w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Boven N, Akkerhuis KM, Anroedh SS, et al. In search of an efficient strategy to monitor disease status of chronic heart failure outpatients: added value of blood biomarkers to clinical assessment. Neth Heart J 2017;25:634–42. 10.1007/s12471-017-1040-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041068supp001.pdf (2MB, pdf)