Abstract

Purpose

Viral diseases increasingly endanger the world public health because of the transient efficacy of antiviral therapies. The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been recently identified as caused by a new type of coronaviruses. This type of coronavirus binds to the human receptor through the Spike glycoprotein (S) Receptor Binding Domain (RBD). The spike protein is found in inaccessible (closed) or accessible (open) conformations in which the accessible conformation causes severe infection. Thus, this receptor is a significant target for antiviral drug design.

Methods

An attempt was made to recognize 111 natural and synthesized compounds in order to utilize them against SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein to inhibit Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) using simulation methods, such as molecular docking. The FAF-Drugs3, Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS), ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) databases along with Lipinski’s rules were used to evaluate the drug-like properties of the identified ligands. In order to analyze and identify the residues critical in the docking process of the spike glycoprotein, the interactions of proposed ligands with both conformations of the spike glycoprotein was simulated.

Results

The results showed that among the available ligands, seven ligands had significant interactions with the binding site of the spike glycoprotein, in which angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is bounded. Out of seven candidate molecules, six ligands exhibited drug-like characteristics. The results also demonstrated that fluorophenyl and propane groups of ligands had optimal interactions with the binding site of the spike glycoprotein.

Conclusion

According to the results, our findings indicated the ability of six ligands to prevent the binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein to its cognate receptor, providing novel compounds for the treatment of COVID-19.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42600-020-00122-3.

Keywords: Coronavirus 2019, Spike glycoprotein, Molecular docking, Fluorophenyl, Propane

Introduction

In December 2019, a newly identified coronavirus disease (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan city, China, which rapidly resulted in a global pandemic. Coronaviruses are the large family of viruses that belong to the Coronaviridae family. Based on genomic structures and phylogenetic relationships, the subfamily Coronavirinae includes four genera, namely, α-coronavirus, β-coronavirus, γ-coronavirus, and ∆-coronavirus (Woo et al. 2012). The newly identified coronavirus is named acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is categorized into the genus β-coronavirus (Hui et al. 2020), which causes respiratory and intestinal infections in animals and humans (Vijay and Perlman 2016). Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) has 79% and 50% similarity in genome sequences of Middle-East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), respectively (Lu et al. 2020). However, there are significant discrepancies in disease transmission and pathophysiology among these three infectious diseases (Cruz et al. 2020; Huang et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Studies have revealed that the rate of infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 is markedly higher than that of other members of the Coronaviridae family. It is now known that SARS-CoV-2 has a close relationship with the other two coronaviruses, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV (Organization, W.H 2020; Tai et al. 2020). However, there are still no antiviral medications and vaccines approved for the treatment and prevention of SARS-CoV-2. The structure of coronaviruses is mainly composed of the spike (S), envelopes (E), membranes (M), and nucleocapsid (N) (Zhou et al. 2018; Cui et al. 2019). Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) is a key enzyme that SARS-CoV and several coronaviruses can bind to it to enter lung epithelial cells (Kirchdoerfer et al. 2018; Song et al. 2018). The most current findings suggest that SARS-CoV-2 is able to bind ACE-2, expressing on the cell surface of its hosts by means of the spike protein (S protein) receptor-binding domain (Goswami and Bagchi 2020; Walls et al. 2020; Li et al. 2005). Thus, by blocking the binding site of the S proteins in ACE-2, the interaction of the virus-receptor complex would not be feasible, and infection cannot occur.

The spike glycoprotein, which forms a homo-trimer domain protruding from the outer surface of the virion, can facilitate the entry of the virus into host cells (Walls et al. 2016). The spike glycoprotein contains 1300 amino acids and is expressed as a single polypeptide chain (in the form of a precursor) and cleaved by host furin-like proteases to be converted into the amino (N)-terminal S1 subunit and the carboxyl (C)-terminal S2 subunit. The host cell binding, recognizing the host receptor, and the stabilization of host cell membrane and viral membrane fusion during infection are the significant roles that the spike glycoprotein is responsible (Du et al. 2009; Millet and Whittaker 2015). As shown in Fig. 1, the homo-trimers and a monomer protein of the S glycoprotein are represented, respectively. The two conformations of the spike glycoprotein are shown in Fig. 1a, in which the ectodomain trimer of the closed conformation has 3 symmetrical chains with 3 binding sites for ACE-2. These binding sites are very crucial in the crystallography of the SARS-CoV-2-ACE2 complex (Li et al. 2005). The accessible form of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein is an asymmetric reconstruction of the trimmer with a single subunit B domain (Fig. 1b) (Walls et al. 2020). These indicate that the spike glycoprotein trimers in the accessible form are present in severe infectious diseases caused by coronaviruses, while the inaccessible conformation is mostly detected in the common cold (Guan et al. 2003; Li et al. 2004; Wan et al. 2020). Based on recent evidence, the binding affinity of SARS-CoV for human ACE-2 is correlated with viral transmission rate, viral replication in distinct organisms, and the disease severity (Graham and Baric 2010; Hofmann and Pöhlmann 2004). It is believed that the most pathogenic forms of coronaviruses express the spike glycoprotein trimers spontaneously, inducing the inaccessible and accessible conformations in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, respectively (Walls et al. 2020). The subunits S1 and S2 are two functional subunits responsible for the host cell receptor and viral-cell membrane fusion that forms the spike glycoprotein (Walls et al. 2016; Belouzard et al. 2009; Bosch et al. 2003; Kirchdoerfer et al. 2016). The subunit S1 facilitates the virus-cell membrane complex by identifying specific receptors on the host cell surface (Li 2015; Li 2016; Lu et al. 2015; Graham and Baric 2010). A hydrophobic fusion peptide and two heptad repeat regions contain the subunit S2 (Song et al. 2018). Upon the attachment of the spike receptor-binding domain with the cell receptor ACE-2, some conformational changes occur in S1 and S2 subunits, leading to the exposure of the fusion loop and its insertion into the target cell membrane (Hofmann and Pöhlmann 2004; Lan et al. 2020). Different groups of ligands were known to block the binding of the spike glycoprotein to ACE-2, namely, antiviral agents, flavonoids, fluorophenyl, phenylpropanoids, and some drugs used for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2, compounds similar to fluorophenyl groups. These groups were virtually screened using the PubChem database, and finally, 3 compounds were chosen that had propane groups. Antiviral compounds have been used because of their antiviral properties and their effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2. Flavonoids are present in nearly all fruits and vegetables, as a category of natural substances with variable phenolic structures (Panche et al. 2016). These natural products are well known for beneficial effects on human health, such as antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and antiviral activity (Cushnie and Lamb 2005; Pietta 2000; Ren et al. 2003; Zhou and Li 2007). The fluorophenyl compounds are composed of fluorine plus phenyl groups. Studies have demonstrated that 2-fluorophenyl, 3-fluorophenyl, and 4-fluorophenyl groups have antibiotic and antifungal activity, so these compounds could be included in docking analyses in our study (Saleh et al. 2010). Phenylpropanoids are a class of plant secondary metabolites derived from aromatic amino acids, such as phenylalanine, found in many plants or tyrosine found in partial monocots (Deng and Lu 2017). These types of compounds are useful for human health, so phenylpropanoids could be applied for therapeutic purposes, such as producing antioxidants, anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and antibacterial substances (Korkina et al. 2011). In this study, using the molecular docking analysis, we sought to identify new active and stable inhibitors against the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein S1 subunit from a total of six different groups that are mentioned earlier. Thus, it is conceivable that blocking the interaction between the spike glycoprotein and ACE-2 can prevent the entry of the virus to the host cells. AutoDock Vina (http://autodock.scripps.edu) is a popular open-source application and used for molecular docking and the prediction of ligand-receptor interactions. In the drug discovery process, molecular docking is considered a computationally intensive and semi-valid method.

Fig. 1.

a Closed SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein trimer. b Opened SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein trimer. c The monomer of S glycoprotein with different subunits

Methods

Protein preparation

As mentioned above, subunit S1 in the B domain is responsible for different pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2; hence, in this experiment, only the B domain was examined in both accessible and inaccessible conformations of the spike glycoprotein. Both conformations of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein were downloaded from Protein Data Bank (Table 1) (Berman et al. 2000). First, MODELER 9.2 software was used for modeling missing residues located in the S1 subunit for both selected B domains. Following the modeling of the chains, the position of the amino acids was altered in both conformations, as in the accessible type 87 amino acids were deleted (amino acid 87 was converted into amino acid 1 in terms of the sequence order), while 102 amino acids were removed from the inaccessible type when both structures were downloaded from PDB (Webb and Sali 2016; Fiser and Do 2000). AutoDock Vina (http://autodock.scripps.edu) is a popular open-source application for molecular docking analysis, as well as the prediction of ligand-receptor interactions. In the drug discovery process, molecular docking is a computationally intensive and semi-reliable method. The B domains and ligands were then converted into the PDBQT format to undergo docking by the Autodock Vina software (Trott and Olson 2010). Before the docking process, polar hydrogens and Gasteiger charges were applied for the configuration of B domains and ligands. The Autodock Vina docking tool was utilized to examine the ligand binding on the B domain. Additionally, blind docking of ligands was performed to recognize the possible binding sites in the S1 subunit. To this aim, the entire protein was covered with the grid box of dimension 36.70×50×70.01 Å in the accessible form of the protein and 63.29×52.10×50.14 for the inaccessible form with grid spacing 1 Å. Finally, the conformations with high negative binding energy in binding sites mentioned in the recent study were chosen (Fig. 2) (Walls et al. 2020; Lan et al. 2020; Yan et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Crystal structures obtained from the RSCB protein data bank

| Protein | PDB ID | Type | Resolution (Å) | Missing residue in B chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein | 6VYB | Open state | 3.2 | 102 |

| SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein | 6VXX | Close state | 2.8 | 87 |

Fig. 2.

The steps of molecular docking of the B domain of S-protein and ligands are represented

Ligand preparation

The 3-D structures of ligands were extracted from ChemSpider and PubChem databases, and then the files were converted into the PDB format using the molecular visualization package of Chimera (Meng et al. 2006; Pettersen et al. 2004). In order to prepare and optimize the ligands for docking, polar hydrogen atoms were inserted, torsional degrees of freedom (nTDOF) were determined, and Gasteiger charges were calculated for all generated ligands. All ligands were ranked based on physicochemical properties, as shown in Table S1.

Ligand-receptor interaction analysis

In order to demonstrate inter-molecular interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, h-bonds, halogen bonds, and π/aromatic interactions), Accelrys Discovery Studio Visualizer software version 4.1 (ADSV) was applied. In addition, intermolecular hydrogen bonds were also examined using the LigPlot+ v.2.2, PyMol v.2.3.2, and UCSF Chimera.1.12 (Laskowski and Swindells n.d.; BIOVIA 2017; Studio 2008). By means of UCSF Chimera and ADSV, all hydrogen bonds were included, and the required edition was performed on ligand topology varieties.

Drug-like characteristics

It is necessary to analyze the main parameters associated with absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties such as the five rules of Lipinski, drug solubility, pharmacokinetic properties, molar refractivity, and drug likeliness in order to produce efficient medicines with proper therapeutic indices (Bueno 2020; Lipinski 2004). The drug design requires ADME analysis before the discovery process, at a period when multiple compounds are potential candidates; however, gaining access to physical samples is restricted. Therefore, the computational prediction of ADME for candidate ligands is virtually performed (Daina et al. 2017). The ADME analysis of all candidate ligands was carried out using online software (http://www.swissadme.ch). Lipinski’s rules state that an active oral compound should not violate more than one of five rules. Lipinski’s rules include having a molecular weight (MWT) ≤ 500, log P ≤ 5, H-bond donors ≤ 10, and H-bond acceptors ≤ 10 (Lipinski et al. 1997). Moreover, pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) identifies a variety of sub-structural features that may help to recognize compounds appearing as frequent ligands (promiscuous compounds) in several high-throughput biochemical screens (Baell and Holloway 2010), A web server, FAF3-Drugs, was used for filtering large compound libraries before in silico screening different analyses or related modeling studies (Lagorce et al. 2015).

Results

Molecular docking

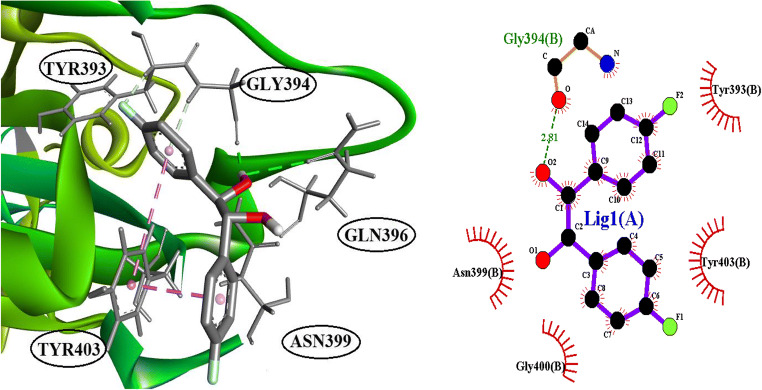

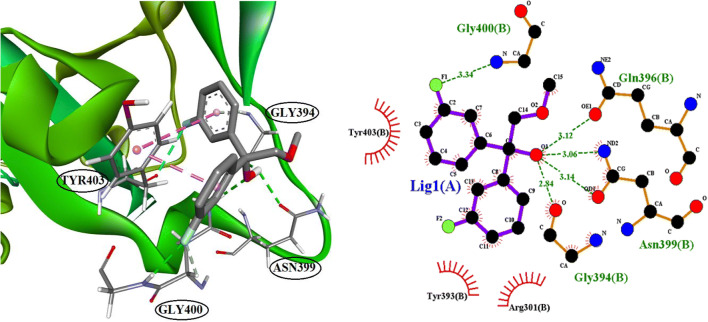

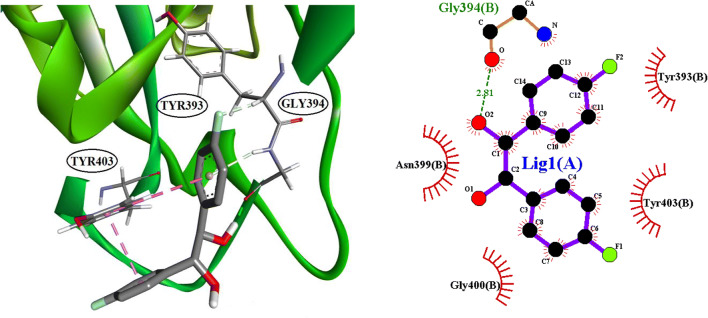

The identification of ligands, which are binding to the binding site of ACE2, was conducted by molecular docking. In this experiment, 111 compounds downloaded from the ChemSpider and PubChem databases were submitted to molecular docking software. All ligands with their chemical formula, binding affinity in accessible conformation, and SB domain residues interactions through hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds are shown in Table 2, in which the residues at the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex are bolded (the data of inaccessible conformation is also available as Supplementary File S2). According to molecular docking results, seven molecules were selected and subjected to drug-like filtering. The hydrogen-bond and hydrophobic interactions at the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE2 complex are bolded in Table 3 for both accessible and inaccessible conformations of the spike protein (Fig. 3). Rossicaside A has a hydrophobic binding site possessing Tyr347 in the accessible state, with a binding energy of −7.4 kcal/mol. As shown in Fig. 4, 1,2-ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) with a binding energy of −6.6 kcal/mol in the accessible conformation forms hydrogen bonds with Gly394 and three hydrophobic binding residues in which Tyr393 and Tyr403 are present at the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex. As depicted in Fig. 5, 1,2-propanediol, 3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) with a binding energy of −6.7 kcal/mol forms a hydrogen bond with Gly394, and its hydrophobic bond interacts with Tyr393, Asn399, and Tyr403 residues. Also, 1,1-bis(3-fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol with a binding energy of −6.6 kcal/mol in the accessible conformation forms hydrogen bonds with Gly394, Gln396, Asn399, and Gly400 residues while other hydrophobic interacting residues were Tyr393 and Tyr403 (Fig. 6). Besides, 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol also forms two hydrogen bonds with Gly394 and Asn399 residues and two hydrophobic bonds with Tyr393 and Tyr403 residues (Fig. 7). The seventh chosen ligand was (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol with a binding energy of −6.2 kcal/mol that forms hydrogen bonds with Gly394, Gln396, and Asn399 residues and hydrophobic bonds with Tyr393 and Tyr403 residues (Fig. 8). In inaccessible conformation, hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds are displayed in Table 1 (all hydrogen bonds in the closed state are shown in Supplementary File S2).

Table 2.

Result of 6vyb molecular docking with all ligands, which are under study in this work. Five ligand groups are ranked by binding affinity

| Ligand name | Chemical formula | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Residue interaction with ligand through hydrogen binding | Residues interaction with ligand through hydrophobic binding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-viruses | ||||

| Indinavir | C36H47N5O4 | −8.1 | Asn241, Asn335 | Phe240, Phe272, Leu339 |

| Maraviroc | C29H41F2N5O | −8 | G424 | Phe227, Ile230, Thr231, Asp287, Lys426 |

| Raltegravir | C20H21FN6O5 | −8 | Ser269, Trp334, Arg407 | Val265 |

| Saquinavir | C38H50N6O5 | −7.7 | Ser264, Pro425 | Val225, Ile230, Lys427 |

| Methylprednisolone | C22H30O5 | −7.6 | Arg253, Thr328, Gln414 | Phe362 |

| Etravirine | C20H15BrN6O | −7.5 | Ser271 | Phe240, Asn241, Phe272, Trp334, Leu339 |

| Acteoside | C29H36O1 | −7.3 | Phe240, Asn241, Asn335, Asn338, Gln404 | Phe272, Trp334 |

| Cyclosporin A | C62H111N11O12 | −7.2 | Arg253 | Phe290, Tyr294, Phe327, Thr328, Phe362, Leu415, Leu416 |

| Nelfinavir | C32H45N3O4S | −7.1 | Thr421, Cys423 | Phe227, Pro228, Ile230, Thr231, Val260, Lys426 |

| Efavirenz | C14H9ClF3NO2 | −7 | Thr328 | Tyr294, Pro324, Phe362 |

| Aldosterone | C21H28O5 | −6.9 | Arg253, Thr328, Glu414 | Phe362 |

| Delavirdine | C22H28N6O3S | −6.9 | Asn258 | Phe227, Asn258 |

| Alclometasone | C22H29ClO5 | −6.8 | Thr328, Pro361, Phe362 | Phe362, Glu414 |

| Abacavir | C14H18N6O | −6.7 | Ser269. Ser271 | Val265, Leu266, Phe272 |

| Atazanavir | C38H52N6O7 | −6.6 | Arg253 | Phe290, Tyr294, Phe328, Phe362, Leu415, Leu416 |

| Imiquimod | C14H16N4 | −6.6 | – | Leu266, Phe272, Trp334 |

| Lopinavir | C37H48N4O5 | −6.6 | Cys259 | Phe227, Pro228, Ile230, Thr231, Asn258, Val260, Lys426 |

| Entecavir | C12H15N5O3 | −6.5 | Cys259 | – |

| Sofosbuvir | C22H29FN3O9P | −6.5 | Cys259, Asn442 | Phe227, Pro228, Ile230, Asn258, Thr421, Lys426 |

| Zidovudine | C10H13N5O4 | −6.4 | Ala420, Gly424 | – |

| Stavudine | C10H12N2O4 | −6.3 | Ser269, Ser271 | Phe240, Phe272, Phe272, Leu339 |

| Telbivudine | C10H14N2O5 | −6.3 | Ser271, Arg407 | Phe240, Phe272, Trp334, Leu339 |

| Zalcitabine | C9H13N3O3 | −6.3 | Ser271 | Phe240, Leu266, Trp334 |

| Didanosine | C10H12N4O3 | −6.1 | Phe240, Asn241, Ser269, Ser271 | Phe272 |

| Nevirapine | C15H14N4O | −6.1 | – | Phe240, Phe272, Trp334 |

| Ribavirin | C8H12N4O5 | −6.1 | Arg352, Arg355, Ser367, Gln369 | – |

| Telaprevir | C36H53N7O6 | −6.1 | – | Phe227, Pro228, Ile230, Val260, Lys426, Asn442 |

| Emtricitabine | C8H10FN3O3S | −6 | Cys259, Thr421, Gly424, Lys426 | – |

| Ganciclovir | C9H13N5O4 | −5.9 | Phe240, Trp334, Arg407 | Ala242, Ser269, Ser271, Arg407 |

| Fosamprenavir | C25H36N3O9PS | −5.8 | Thr231 | Phe227, Pro228, Val260,Lys426 |

| Penciclovir | C10H15N5O3 | −5.8 | Phe227, Pro228, Asp262, Lys426 | Ile230, Pro425, Lys427 |

| Rimantadine | C12H21N | −5.8 | Cys234, Gly237 | Leu233, Phe236, Val265, Leu266 |

| Lamivudine | C8H11N3O3S | −5.7 | Pro228, Cys259, Thr421, Gly424, Lys426 | Thr231 |

| Valganciclovir | C14H22N6O5 | −5.7 | – | Phe240, Ser269, Ser271 |

| Aciclovir | C8H11N5O3 | −5.6 | Phe240, Asn241, Ser269, Ser271 | – |

| Gancyclovir | C9H13N5O4 | −5.6 | Phe240, Asn241 | – |

| Ritonavir | C37H48N6O5S2 | −5.6 | – | Pro228, Thr231, Val260, Asn442 |

| Tenofovir | C9H14N5O4P | −5.6 | Trp334 | Phe272, Trp334 |

| Valaciclovir | C13H20N6O4 | −5.6 | Asn241, Ser269, Trp334 | Leu339 |

| Famciclovir | C14H19N5O4 | −5.5 | Ala420 | Phe227, Ile230, Thr231, Val260 |

| Idoxuridine | C9H11IN2O5 | −5.5 | Trp334 | – |

| Oseltamivir | C16H28N2O4 | −5.5 | Asp318, Thr328, Ser412 | Pro324, Thr328, Phe362, Glu414 |

| Zanamivir | C12H20N4O7 | −5.5 | Arg226, Ser428, Gln478 | – |

| Amantadine | C10H17N | −5.3 | Pro228, Asn229 | Val260, Lys426 |

| Docosanol | C22H46O | −3.8 | – | Ile230, Leu233, Phe236, Val265, Leu266, Pro425 |

| Methoxyethanol | C3H8O2 | 2.9 | Arg352, Lys356, Ser367, Glu369 | – |

| Enfuvirtide | C204H301N51O64 | −2.2 | Ser257 | – |

| Drug of cov2 | ||||

| Baloxavir marboxil | C27H23F2N3O7S | −7.7 | – | Phe227, Pro228, Ile230, Thr231, Lys426, Asn442 |

| Indomethacin | C19H16ClNO4 | −7 | Pro228 | Ile230, Thr231, Val260, Lys426 |

| Azvudine | C9H11FN6O4 | −6.2 | Cys423, Gly424, Lys426 | – |

| Oseltamivir | C16H28N2O | −5.4 | Thr328, Ser412 | Pro324, Thr328, Pro361, Phe362, Glu414 |

| Chloroquine | C18H26ClN3 | −5.3 | THR328 | Tyr294, Thr328, Pro361, Phe326, Glu414 |

| Favipiravir | C5H4FN3O2 | −5 | Val239, Ala246, Asn252, Ser297 | |

| Flavonoids | ||||

| Ononin | C22H22O9 | −7.8 | Thr283, Asp287, Lys427 | Ile230, Pro425 |

| Genistein | C15H10O5 | −7.3 | Asn338 | Phe272, Leu339 |

| Luteolin | C15H10O6 | −7.2 | Ser273, Thr274, Tyr278, Tyr406 | Lys276, Val305, Arg306 |

| Morin | C15H10O7 | −7.2 | Asn241, Asn338 | Phe240 |

| Fisetin | C15H10O6 | −7.1 | Asp326, Thr328, Pro361, Phe413 | Pro324, Pro361 |

| Taxifolin | C15H12O7 | −7.1 | Ala242, Trp334, Arg407 | Phe240, Asn241, Phe272, Trp334, Leu339 |

| Galangin | C15H10O5 | −7 | Asn241, Asn338 | Phe240 |

| Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | −6.9 | Ser269, Asn338 | Phe240, Phe272 |

| Naringenin | C15H12O5 | −6.8 | Ala242, Trp334, Arg407 | Phe240, Asn241, Phe272, Trp334, Leu339 |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | −6.6 | Asp326, Thr328, Phe413 | Pro361, Phe362 |

| Fluorophenyl | ||||

| 1,2-Ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) | C14H12F2O2 | −6.7 | Gly394 |

Asn319, Tyr393 Tyr403 |

| 1,1-bis(3-Fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol | C15H14F2O2 | −6.6 |

Gly394, Gln396 Asn399, Gly400 |

Tyr393, Tyr403 |

| Phenylpropanoid | ||||

| Telmisartan | C33H30N4O2 | −8.8 | Asp262 | Val260, Ala261, Gly424,Pro425, Lys426,Lys427 |

| Sennoside | C42H38O20 | −8.6 | Arg253, Asp326, Thr328, Ser412, Arg364 | Phe327, Lys360, Pro361,Phe362,Phe413, Glu414 |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | C42H62O16 | −8.3 |

Pro228, Cys259, Cys423, Thr421, Lys426 |

Phe227, Asn229, Ile230,Arg287, Leu288, Cys289, Ala420, Val422 |

| Verbascoside | C29H36O15 | −8.1 | Val239, Ser247, Asn252, Ala250, Ser297, Asn348 | Arg244, Phe245, Ala246, Trp251, Tyr349, Leu350 |

| Orobanchoside | C29H36O16 | −8 | Cys259, Ala420, Thr421, Cys423, | Trp334, Asn335, Ser336, Asn337, Asn338, Ala270, Ser271, Phe274, Ser273 |

| Arenarioside | C34H44O19 | −7.9 | Pro228, Asn229, Thr421, Lys426, Asn442, Cyx259, Gln462 | Phe227, Ile230, Asn258, Cys259, Val260, Val422, Cys423, G424, Pro425 |

| Isomartynoside | C31H40O15 | −7.8 | Ser264, Pro425 | Gly424, Lys426, Lys427, Ser428, Val260, Ala261, Asp262 |

| Poliumoside | C35H46O19 | −7.8 | Thr421, Pro228, Cys259 | Phe227, Asn229, Ile230, Asn258, Val260, Asp287, Leu288, Cys289, Val422, Cys423, Gly424 |

| Teucrioside | C34H44O19 | −7.7 | Asp262, Ser264, Pro425, Ser428, Gln478 | Phe227, Pro228, Asn229, Ile230, Gly424, Lys426, Lys427 |

| Angoroside A | C34H44O19 | −7.7 | Cyx259, Gln462, Pro477 | Asn258, Val260 |

| Pheliposide | C36H46O20 | −7.6 | Asn232, Leu233, Gly237, Asn241, Thr243, Asp262 | Cys234, Pro235, Phe236, Ala 242, Val260, Ala261 |

| Rutin | C27H30O16 | −7.5 | Arg253, Asp326, Thr328, Pro361, Arg364, Phe413, Gln414 | Phe327, Gly329, Ser412 |

| Forsythoside B | C34H44O19 | −7.5 | Pro228, Cys259, Lue288, Ala420, Cys423, Gly424, Lys426 | Pro228 |

| Rossicaside A | C35H46O20 | −7.4 | Gln238, Val239, Ser247, Thr249, Trp251, Asn252, Arg253, Ser297 | Lys249, Ala250, Tyr347, Asn348, Tyr349, Leu350 |

| Forsythiaside A | C29H36O15 | −7.4 | Phe240, Asn241, Ala270, Ser271, Phe272, Asn335, Asn338, Tyr406 | Ser273, Trp334, Ser336, Asn337, Val401 |

| Purpureaside C | C35H46O20 | −7.4 | Leu288, Ala420, Thr421, Gln462 | Phe227 |

| Hesperidin | C28H34O15 | −7.4 | Pro228, Cys259, Thr421, Lys426 | Phe227, Val260 |

| Isoverbascoside | C29H36O1 | −7.4 | Ala244, Ser247, Trp251, Asn252, Ser297, Asn348 | Ala246, Phe245, Tyr249, Ala250 |

| Leucosceptoside A | C30H38O15 | −7.4 | Asp326, Thr328, Pro361, Glu414, Leu415 | Tyr294, Pro 324, Phe362, Leu415 |

| Corosolic acid | C30H48O4 | −7.3 | Ser273, Thr406 | Val305, Arg306, Ala309, Val401, Tyr406 |

| Calceolarioside C | C28H34O15 | −7.2 | Asn241, Ser271, Ser296, Trp334, Asn335, Asn338 | Asn241 |

| Eukovoside | C30H38O15 | −7.2 | Val239, Phe245, Ser247, Asn348, Ser297 | Tyr249, Ile366, Thr368 |

| Angoroside C | C36H48O19 | −7.1 | Asn229, Pro228, Thr231, Cys259, Thr421, Cys423, Lys426 | Phe227, Pro228, Val260 |

| Conandroside | C28H34O15 | −7.1 | Gln238, Ala250, Trp251, Asn252, Ser247, Ser297, Asn348 | Ala250, Ile366 |

| Losartan | C22H23ClN6O | −7.1 | Ser273, Arg306 | Thr274, Lys276, Val305, Arg306, Val331, Val401 |

| Martynoside | C31H40O15 | −7.1 | Ala246, Ser247, Asn252, Ser297, Asn348 | Tyr249, Ile366 |

| Suspensaside | C29H36O16 | −7.1 | Arg253, Thr328, Lys360, Arg364, Phe413, Glu414 | Tyr294, Phe362 |

| Cistanoside D | C31H40O15 | −7 | Thr328, Phe413, Gly414, Leu415 | Tyr294, Pro324, Pro361, Phe362,Leu415 |

| Osmanthuside B | C29H36O13 | −7 | Cys259, Ala420, Thr421, Cys423 | Phe227, Pro228, Thr231, Val260, Lys426, Pro477 |

| Tubuloside A | C37H48O21 | −6.9 | Arg253, Thr328, Asp326, Phe362, Arg364 | Pro324, Phe362, Glu363, Glu414 |

| Grayanoside B | C26H42O9 | −6.9 | Cys259, Thr421, Asn442 | Phe227, Thr231, Lys426 |

| Campneoside | C30H38O16 | −6.7 |

Pro228, Asn229, Cys259, Val260, Cys423 Gly424 |

Val260 |

| Cistanoside C | C30H38O15 | −6.7 | Pro228, Asn229, Cys259, Cys423 | Phe227, Val260 |

| Grayanoside A | C24H28O10 | −6.7 | T328, Pro361, Phe413 | Tyr294, Pro324, Phe362 |

| Oleuropein | C25H32O13 | −6.5 | Thr231, Asn258, Leu288, Ala420, Gly424 | THE231 |

| Tubuloside C | C37H48O21 | −6.3 | Arg253, Thr325, Arg364 | Pro324, Pro361, Phe362, Glu414, Leu416 |

| Salidroside | C14H20O7 | −6.1 | Ala242, Ser269, Thr334, Arg407 | Phe240, Trp334 |

| Propane | ||||

| 1,2-Propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) | C9H9F3O2 | −6.7 | Gly394 |

Tyr393, Asn399 Tyr403 |

| 1,1-Diphenyl propane-1,2-diol | C16H18O2 | −6.4 | Gly394, Asn399 |

Arg301, Tyr393 TYR403 |

| (S)-1,1-Diphenylpropane-1,2-diol | C15H16O2 | −6.2 |

Gly394, Gln396 Asn399 |

Tyr393, Tyr403 |

Table 3.

Summary of top seven ranked ligands screened against RBD of Spike 2019 n-cov2, with their respective classification, chemical formula, binding affinity, hydrogen, and hydrophobic interacting residues

| Ligand name | Open state | Closed state | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bond | Hydrophobic bond | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bond | Hydrophobic bond | |

| Rossicaside A | −7.5 |

Gln238 Val239 Ser247 Thr249 Trp251 Asn252 Arg253 Ser297 |

Lys249 Ala250 Tyr347 Asn348 Tyr349 Leu350 | −6.8 |

Ala257 Ser284 Ser286 Asn353 Asn350 |

Phe255 Leu354 |

| Etravirine | −7.4 | Ser271 |

Phe240 Asn241 Trp334 Leu339 |

−6.7 | Gly409 | Phe377 Glu429 |

| 1,2-Ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) | −6.7 | Gly394 |

Asn319 Tyr393 Tyr403 |

−6.7 | – |

Tyr408 Asn414 Tyr418 |

| 1,2-Propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) | −6.7 | Gly394 |

Tyr393 Asn399 Tyr403 |

−6.7 | Asn414 |

Tyr408 Asn414 |

| 1,1-bis(3-Fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol | −6.6 | Gly394 Gln396 Asn399 Gly400 | Tyr393 Tyr403 | −6.6 |

Gly409 Gln411 Asn414 Gly415 |

Tyr408 Asn414 Tyr418 |

| 1,1-Diphenyl propane-1,2-diol | −6.4 |

Gly394 Asn399 |

Arg301 Tyr393 TYR403 |

−6.4 |

Gln411 Asn414 |

Arg316 Tyr408 Tyr418 |

| (S)-1,1-Diphenylpropane-1,2-diol | −6.2 |

Gly394 Gln396 Asn399 |

Tyr393 Tyr403 |

−6.4 |

Gly409 Asn414 |

Arg316 Tyr408 Tyr418 |

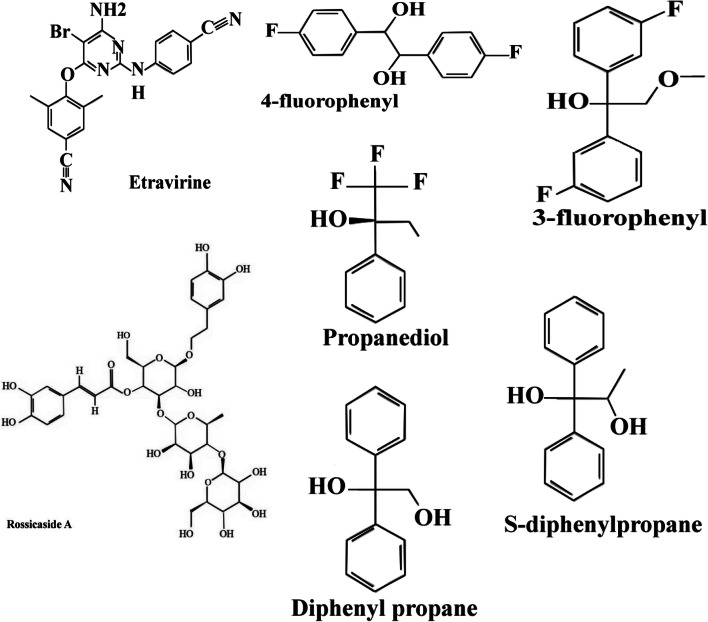

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of selected ligands. Ball and stick models show the optimized structures for molecular docking

Fig. 4.

The interacting binding site amino acid residue of SARS-CoV-2S with 1,2-ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) and LigPlot+ analyses results in the open state of binding conformation of 1,2-ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl)

Fig. 5.

The interacting binding site amino acid residue of SARS-CoV-2S with 1,2-propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) and LigPlot+ analyses results in the open state of binding conformation of 1,2-propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R)

Fig. 6.

The interacting binding site amino acid residue of SARS-CoV-2S with 1,1-bis(3-fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol and LigPlot+ analyses results in the open state of binding conformation of 1,1-bis(3-fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol

Fig. 7.

The interacting binding site amino acid residue of SARS-CoV-2S with 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol and LigPlot+ analyses results in the open state of binding conformation of 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol

Fig. 8.

The interacting binding site amino acid residue of SARS-CoV-2S with (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol and LigPlot+ analyses results in the open state of binding conformation of (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol

Drug-like characteristic of the chosen ligands

ADME database contains the latest and most comprehensive information about the interactions of substances with drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug transporters that are specific to humans. It is designed for use in drug research and development, including drug-drug interactions (Matter et al. 2001). In order to assess the pharmacokinetic characteristic of the chosen ligands, the drug-likeliness of 7 chosen ligands was evaluated based on Lipinski’s rule of five (Lipinski et al. 1997). (Lipinski et al. 1997). Lipinski’s rule of five suggests that weak absorption is more probable if more than 5 H-bond donors are involved, 10 H-bond acceptors, the molecular weight exceeds 500 Da, and the calculated high lipophilicity (LogP) exceeds 5 (Lipinski et al. 1997). The qualifying range for molar refractivity was within a range of 40–130, with a mean value of 97 (Matter et al. 2001). As shown in Table 3, Rossicaside A would not be suitable according to Lipinski’s rule of five since its molar refractivity is more than 130, and it violates three rules. The remaining ligands met the required criteria of MADE (Table 3). PAINS filtering was conducted to identify the presence of chemical groups belonging to the PAINS category. Six out of seven ligands were accepted as drug-like compounds, and the physicochemical filter passed without any structural caution (Table 4). Rossicaside A was discarded as a result of possessing the catechol group in the PAINS sub-structural moieties. Also, FAF3-Drugs filtering rejected Rossicaside A, while other ligands were accepted by this filtering.

Table 4.

FAF-Drugs3 and pan assay interference (PAINS) filtering of 7 identified ligands

| N | Ligand | FAF-Drugs3 filtering | PAINS filtering |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,1-Diphenylpropane-1,2-diol | Accepted | None |

| 2 | 1,2-Propanediol, 3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) | Accepted | None |

| 3 | 1,1-bis(3-Fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol | Accepted | None |

| 4 | 1,2-Ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) | Accepted | None |

| 5 | Etrinavir | Accepted | None |

| 6 | Rossicaside A | Rejected | Catechol |

| 7 | (S)-1,1-Diphenylpropane-1,2-diol | Accepted | None |

Discussion

In the specialized field of computer-aided drug design to discover new compounds, molecular docking is widely used to explore different forms of the binding interactions between the prospective drugs and various domains or active sites, as well as binding sites on target molecules (Raj et al. 2019; Hughes et al. 2011). For a decade, molecular docking has been a great tool for the exploration of potential compounds, and it is used to model atomic bindings between proteins and small molecules. This helps us to characterize the interactions of small molecules at the binding sites of the target proteins (Meng et al. 2011). In viral infections, due to the lack of successful antiviral therapies, there is an urgency to speed up the process of drug development to find new and effective drug candidates. The spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 plays significant roles in binding, fusion, and entry into the host cells (Yan et al. 2020). The B domain in this protein causes the formation of two open and closed forms of coronavirus. The B domain is in a heterotrimeric form with three different polypeptide chains, namely, chains A, B, and C; each constitutes a monomer (Walls et al. 2020). In this study, the B chain of the spike glycoprotein in both open and closed forms (PDB ID: 6vyb and 6vxx, respectively) was used to model the missing residues and molecular docking. To this purpose, 111 compounds were screened obtained from ChemSpider and PubChem databases (Table 1) to find the optimal ligands to block the B-chain binding site interacting with ACE-2. The compound IDs (CIDs) of selected ligands obtained from the PubChem database were as follows: CID 13916145, CID 193962, CID 2755890, CID 11095754, CID 53722331, CID 555451, and CID 736300, which interact with the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex with the energy binding affinity of −7.5 kcal/mol, −7.4 kcal/mol, −6.7 kcal/mol, −6.7 kcal/mol, −6.6 kcal/mol, −6.4 kcal/mol, and −6.2 kcal/mol, respectively. Among all different types of interactions that are usually analyzed, such as H-bond, π-π, and amide-π interactions, the ligand binding energy attracts further attention, and the characteristics of amino acids involved in the binding site are further assessed (Raj et al. 2019; Hughes et al. 2011). The final proposed ligand was Rossicaside A, which is a phenylpropanoid that along with its derivatives, is commonly found in fruits, vegetables, grains of cereals, beverages, spices, and herbs. They have antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and anti-cancer activities, as well as renoprotective, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, and hepato-protective effects (Jia et al. 2018; Shyr et al. 2006). Etravirine is a non-nucleoside and inhibitor of the reverse transcriptase enzyme, which is orally administered and prescribed for the treatment of AIDS in whom resistant to other anti-retrovirals (ARVs) (Croxtall 2012). Different combinations of this structure exist; for instance, 1,2-ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) and 1,1-bis(3-fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol are two fluorophenyl compounds that have hydrogen and hydrophobic interactions at the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE2 complex. Therefore, three ligands (1,2-propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R); 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol; and (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol) were used in our study since they had a similar structure to fluorophenyl compounds. Given the pharmacological properties of the selected ligands, it is concluded that many of the important pharmacophore properties required for adequate inhibition of SB protein are consistent with the six known ligands from the PubChem database. Moreover, their binding to the B chain in both conformations forms a stable complex with a sturdy network of hydrogen and hydrophobic bonds as well as critical residues, namely, Tyr347, Phe377, Tyr393, Gly394, Gln396, Asn399, Gly400, Tyr403, Tyr408, Gly409, Gln411, and Asn414 that were recently predicted as close-contact residues with the human cell host receptor (Walls et al. 2020; Shang et al. 2020). Using ADMEtox filtering, all of the identified ligands were assessed in terms of pharmacokinetic properties. Lipinski’s rule of five is commonly used to determine possible reactions between drugs and other non-drug target molecules. Based on these rules, potential drugs must have (a) molecular mass < 500 Da, (b) high hydrophobicity (expressed as LogP < 5), (c) less than 5 hydrogen bond donors, (d) less than 10 hydrogen bond acceptors, and (e) also the molar refractivity between 40 and 130. The drug-likeness is another factor assessed in ADMEtox filtering. In the case of having three parameters or higher mentioned earlier, a compound may be a candidate to act as a drug (Table 3). PAINS and FAF3-Drugs are two databases for the drug filtering process. FAF3-Drugs is a large filtering program that includes large libraries of compounds used for in silico screening or modeling of drug-protein interactions. PAINS filtering can also analyze thousands of compounds and their interaction with proteins within a few seconds, preventing further unnecessary analyses.

As displayed in Table 5, among seven final candidate ligands, Rossicaside A was excluded by these filtering methods, while the others were accepted. The molecular docking was employed to reveal whether there was any close interaction between potential ligands and the spike glycoprotein. Regardless of some drawbacks, such as in vitro conditions and not being the in vivo conditions, the use of molecular docking allows researchers to make more precise decisions within a shorter timeframe. The results showed acceptable binding affinity of Etravirine, 1,2-ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl), 1,2-propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R), 1,1-bis(3-fluorophenyl)-2-methoxy ethanol, 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol, and (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol, to the binding site of the spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex.

Table 5.

ADME properties of selected ligands against SB domain

| No. | Ligands | ADME properties | Drug likeliness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,1-Diphenyl propane-1,2-diol | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 242.13 g/mol | Yes |

| LogP (<5) | 1.809 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 2 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 2 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 67.72 | |||

| Violations | NO | |||

| 2 | 1,2-Propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl-(2R) | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 206.06 g/mol | Yes |

| LogP (<5) | 1.099 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 2 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 2 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 43.42 | |||

| Violations | NO | |||

| 3 | 1,1-bis(3-Fluorophenyl)-2-methoxyethanol | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 264.1 g/mol | Yes |

| LogP (<5) | 0.417 | |||

| H-bond donor (5) | 1 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 2 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 67.55 | |||

| Violations | NO | |||

| 4 | 1,2-Ethanediol,1,2-bis(4-fluorophenyl) | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 250.208 g/mol | |

| LogP (<5) | 0.148 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 2 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 2 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 62.94 | |||

| Violations | NO | |||

| 5 | Etravirine | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 434.05 g/mol | Yes |

| LogP (<5) | 0.904 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 2 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 7 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 109.56 | |||

| Violations | NO | |||

| 6 | Rossicaside A | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 786.26 g/mol | No |

| LogP (<5) | 2.244 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 12 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 20 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 180.81 | |||

| Violations | 3 | |||

| 7 | (S)-1,1-Diphenylpropane-1,2-diol | Molecular weight (<500 Da) | 228.12 g/mol | Yes |

| LogP (<5) | 1.392 | |||

| H-bond donar (5) | 2 | |||

| H-bond acceptor (<10) | 2 | |||

| Molar Refractivity (40–130) | 67.72 | |||

| Violations | No | |||

Conclusion

SARS-Cov-2 has emerged as a significant pandemic pathogen. It has been shown that the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein is a highly potent and critical target for the inhibition of COVID-19. In the present study, we attempted to seek the optimal ligands, using molecular docking, to have interactions with the B chain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex. Molecular docking selected six ligands (Etravirine [−7.4 kcal/mol], 4-fluorophenyl [−6.7 kcal/mol], 1,2-propanediol,3,3,3-trifluoro-2-phenyl [−6.7 kcal/mol], 3-fluorophenyl [6.6 kcal/mol], 1,1-diphenyl propane-1,2-diol [−6.4 kcal/mol], and (S)-1,1-diphenylpropane-1,2-diol [6.2 kcal/mol]) from different groups with potential inhibition and high affinity to the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein to prevent the formation of the spike glycoprotein-ACE-2 complex. The selected compounds were subsequently submitted to the ADME webserver to analyze the toxicity of compounds against the human cells. The compounds that met the required criteria could be tested in animal models to analyze the efficacy of these chemicals in vivo.

Limitations

Due to the high risk of this virus, the experimental part for this study was omitted.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 38 kb)

(DOCX 3044 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for helpful feedback and observations to the reviewers and editors, which helped enhance the paper quality.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants and animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Baell JB, Holloway GA. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem. 2010;53(7):2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belouzard S, Chu VC, Whittaker GR. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(14):5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman HM, et al. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIOVIA DS. Discovery studio visualizer. CA: San Diego; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CAM, Rottier PJM. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J Virol. 2003;77(16):8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, J., ADMETox: bringing nanotechnology closer to Lipinski’s rule of five, in Preclinical Evaluation of Antimicrobial Nanodrugs. 2020, Springer. p. 61–74.

- Croxtall JD. Etravirine. Drugs. 2012;72(6):847–869. doi: 10.2165/11209110-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.V.C.P., et al., Family-focused home care plan during a COVID-19 epidemic: a consensus statement by the PAFP task force on COVID-19. 2020.

- Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie TT, Lamb AJ. Antimicrobial activity of flavonoids. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;26(5):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Lu S. Biosynthesis and regulation of phenylpropanoids in plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2017;36(4):257–290. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2017.1402852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du L, et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(3):226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A, Do RKG. Modeling of loops in protein structures. Protein Sci. 2000;9(9):1753–1773. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, T. and B. Bagchi, Molecular docking study of receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein with saikosaponin, a triterpenoid natural product. 2020.

- Graham RL, Baric RS. Recombination, reservoirs, and the modular spike: mechanisms of coronavirus cross-species transmission. J Virol. 2010;84(7):3134–3146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01394-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ, Liu XL, Zhuang ZX, Cheung CL, Luo SW, Li PH, Zhang LJ, Guan YJ, Butt KM, Wong KL, Chan KW, Lim W, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Peiris JS, Poon LL. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302(5643):276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H, Pöhlmann S. Cellular entry of the SARS coronavirus. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12(10):466–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan China. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JP, Rees S, Kalindjian SB, Philpott KL. Principles of early drug discovery. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162(6):1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, Ippolito G, Mchugh TD, Memish ZA, Drosten C, Zumla A, Petersen E. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, He Y, Lu F. The structure-antioxidant activity relationship of dehydrodiferulates. Food Chem. 2018;269:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchdoerfer RN, Cottrell CA, Wang N, Pallesen J, Yassine HM, Turner HL, Corbett KS, Graham BS, McLellan J, Ward AB. Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein. Nature. 2016;531(7592):118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature17200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchdoerfer RN, et al. Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkina L, Kostyuk V, de Luca C, Pastore S. Plant phenylpropanoids as emerging anti-inflammatory agents. Mini reviews in medicinal chemistry. 2011;11(10):823–835. doi: 10.2174/138955711796575489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagorce D, Sperandio O, Baell JB, Miteva MA, Villoutreix BO. FAF-Drugs3: a web server for compound property calculation and chemical library design. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W200–W207. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan, J., et al., Crystal structure of the 2019-nCoV spike receptor-binding domain bound with the ACE2 receptor. bioRxiv, 2020.

- Laskowski RA, Swindells MB. LigPlot+: multiple ligand–protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. 2011. ACS Publications. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li F. Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: a decade of structural studies. J Virol. 2015;89(4):1954–1964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02615-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annual review of virology. 2016;3:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Greenough TC, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Somasundaran M, Sullivan JL, Farzan M, Choe H. Efficient replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in mouse cells is limited by murine angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J Virol. 2004;78(20):11429–11433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11429-11433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2004;1(4):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1997;23(1–3):3–25. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Wang Q, Gao GF. Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23(8):468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, Bi Y, Ma X, Zhan F, Wang L, Hu T, Zhou H, Hu Z, Zhou W, Zhao L, Chen J, Meng Y, Wang J, Lin Y, Yuan J, Xie Z, Ma J, Liu WJ, Wang D, Xu W, Holmes EC, Gao GF, Wu G, Chen W, Shi W, Tan W. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter H, Barighaus KH, Naumann T, Klabunde T, Pirard B. Computational approaches towards the rational design of drug-like compound libraries. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2001;4(6):453–475. doi: 10.2174/1386207013330896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF chimera. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7(1):339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, et al. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr Comp Aided Drug Des. 2011;7(2):146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet JK, Whittaker GR. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015;202:120–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H., Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 59. 2020.

- Panche A, Diwan A, Chandra S. Flavonoids: an overview. Journal of nutritional science. 2016;5:e47. doi: 10.1017/jns.2016.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietta P-G. Flavonoids as antioxidants. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(7):1035–1042. doi: 10.1021/np9904509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj, S., et al., Identification of lead molecules against potential drug target protein MAPK4 from L. donovani: An in-silico approach using docking, molecular dynamics and binding free energy calculation. PLoS One, 2019. 14(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ren W, Qiao Z, Wang H, Zhu L, Zhang L. Flavonoids: promising anticancer agents. Med Res Rev. 2003;23(4):519–534. doi: 10.1002/med.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh M, Abbott S, Perron V, Lauzon C, Penney C, Zacharie B. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 2-fluorophenyl-4, 6-disubstituted [1, 3, 5] triazines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(3):945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang, J., et al., Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature, 2020: p. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shyr M-H, Tsai T-H, Lin L-C. Rossicasins a, B and rosicaside F, three new phenylpropanoid glycosides from Boschniakia rossica. Chem Pharm Bull. 2006;54(2):252–254. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W, Gui M, Wang X, Xiang Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(8):e1007236. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studio, D., Discovery Studio. Accelrys [2.1], 2008.

- Tai, W., et al., Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 2020: p. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay R, Perlman S. Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome. Current opinion in virology. 2016;16:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls AC, Tortorici MA, Frenz B, Snijder J, Li W, Rey FA, DiMaio F, Bosch BJ, Veesler D. Glycan shield and epitope masking of a coronavirus spike protein observed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23(10):899–905. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;183:1735. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y., et al., Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol, 2020. 94(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., et al., Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Current protocols in bioinformatics. 2016;54(1):5.6. 1–5.6. 37. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo PC, Lau SK, Lam CS, Lau CC, Tsang AK, Lau JH, Bai R, Teng JL, Tsang CC, Wang M, Zheng BJ, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol. 2012;86(7):3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Li H-j. Bioactivities and clinical applications of flavonoids. Chinese New Drugs Journal. 2007;16(5):350. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Jiang S, Du L. Prospects for a MERS-CoV spike vaccine. Expert review of vaccines. 2018;17(8):677–686. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1506702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 38 kb)

(DOCX 3044 kb)