Abstract

Capsaicinoids are naturally specialized metabolites in pepper and are the main reason that Capsicum fruits have a pungent smell. During the synthesis of capsaicin, MYB transcription factors play key regulatory roles. In particular, R2R3-MYB subfamily genes are the most important members of the MYB family and are critical candidate factors in capsaicinoid biosynthesis. The 108 R2R3-MYB genes in pepper were identified in this study and all are shown to have two highly conserved MYB binding domains. Phylogenetic and structural analyses clustered CaR2R3-MYB genes into seven groups. Interspecies collinearity analysis found that the R2R3-MYB family contains 16 duplicated gene pairs and the highest gene density is on chromosome 00 and 03. The expression levels of CaR2R3-MYB differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and capsaicinoid-biosynthetic genes (CBGs) in fruit development stages were obtained via RNA-seq and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Co-expression analyses reveal that highly expressed CaR2R3-MYB genes are co-expressed with CBGs during early stages of pericarp and placenta development processes. It is speculated that six candidate CaR2R3-MYB genes are involved in regulating the synthesis of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin. This study is the first systematic analysis of the CaR2R3-MYB gene family and provided references for studying their molecular functions. At the same time, these results also laid the foundation for further research on the capsaicin characteristics of CaR2R3-MYB genes in pepper.

Keywords: Capsicum, CaR2R3-MYB family, capsaicinoid biosynthesis, expression analysis, co-expression

Introduction

Secondary metabolites are important compounds in plants to resist stress, deter herbivores, and prevent attack from some pathogens (Tewksbury et al., 2008). It is clear that plants have evolved their own special secondary metabolites on the basis of adaptations to the surrounding environment. Amongst these, the unique defensive chemical compounds produced by Capsicum, including capsaicin (CAP), dihydrocapsaicin (DhCAP), and several analogs, collectively known as capsaicinoids (CAPDs), are the most widely involved (Stewart et al., 2007). It is also known that CAPDs, unique flavoring substances in chili peppers, make peppers spicy but also influence the synthesis and accumulation of volatile aroma substances (Aza-González et al., 2011). In addition to self-protection, CPADs are also widely applied across industries including food, pharmaceuticals, and medical areas (Naves et al., 2019).

Thus, regarding CPAD biosynthetic pathways, CAP and DhCAP account for nearly 90% in pepper species, divided into phenylpropanoid and branched chain fatty acid pathways (Choi et al., 2006). One specific approach is to synthesize capsaicin by condensing vanillylamine molecules and to derive this compound from phenylalanine via branched chain fatty acids (between 9 and 11 carbon atoms), themselves synthesized from either valine or leucine (Arce-Rodriguez and Ochoa-Alejo, 2019). Indeed, as sequencing technology has developed, studies have revealed that Capsicum fruit biosynthesis is strongly influenced by genotype-environment interactions (Qin et al., 2014). Capsaicinoid-biosynthetic genes (CBGs) are expressed preferentially as typical response factors, specifically in the pericarp and placenta, during pepper fruit development processes (Liu et al., 2013). Studies have identified several structural CBGs [such as, CoMT, C4H, AT3, KAS, putative aminotransferase (pAMT), and Acl] involved in capsaicinoid biosynthesis (Von Wettsteinknowles et al., 2000); these accumulate in epidermal cell vesicles in placental tissue and start accumulating between 10 and 20 days post anthesis (DPA), increasing between 20 and 40 DPA (Arce-Rodriguez and Ochoa-Alejo, 2017). Orthologous genes in the pathways of other solanaceous plants (e.g., tomato and potato) are rarely expressed at this stage (Kim et al., 2014). Genetic studies have revealed that two leaky pAMT alleles (pamtL1 and pamtL2) as well as a loss-of-function pAMT allele reduce capsaicinoid levels (Tanaka et al., 2019), while mutations in acyltransferase (Pun1) and pAMT lead to disruption of the capsaicinoid biosynthesis putative gene ketoacyl-ACP reductase (CaKR1) and a loss of pungency (Koeda et al., 2019). It is also clear that Pun1 encodes an acyltransferase necessary to biosynthesize capsaicinoid (Stewart et al., 2005), and silenced AT3 negatively influences the transcription of CBGs (Arce-Rodriguez and Ochoa-Alejo, 2015). The bulk of CBGs exhibit tissue- and stage-specific expressions accompanying the gradual accumulation of capsaicinoids. The transcription factors Erf and Jerf within the complex ERF family are expressed early in fruit development and participate in regulation of the pungency phenotype in chili (Keyhaninejad et al., 2014). These observations show that transcription factors also participate and play key regulatory roles in capsaicin pathway synthesis and metabolism.

Myeloblastosis (MYB) is one of the most important and the largest transcription factor gene families (Dubos et al., 2002). The MYB gene is divided into four subfamilies based on incomplete MYB domain repeats (R), each containing about 52 amino acid residues. This group includes the 4R-MYB, 3R-MYB, R2R3-MYB, and MYB-related subfamilies which each contains a single or partial MYB-related repeat, respectively (Jia et al., 2004). Specifically, R2R3-MYB is the dominant subfamily, occurring in the largest numbers in most plants (Rosinski and Atchley, 1998). Different MYB-type family members have been identified in many species, including in Arabidopsis thaliana (196 members) (Dubos et al., 2002), and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) (162 members, of which 89 are R2R3-MYB type genes) (Wang et al., 2020). Similarly, 559 R2R3-MYBs have been identified in Solanaceae, including 119 complete sequences in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) (Gates et al., 2016). These genes have a wide range of functions and play pivotal regulatory roles in the synthesis of capsaicin. Methyl jasmonate induced CaMYB108 is also involved in the regulation of capsaicin biosynthesis and stamen development (Sun et al., 2019), while the silencing of this gene significantly reduces the expression of CBGs and capsaicinoid content. These observations showed that MYB genes are widely involved in the regulation of capsaicinoid biosynthetic pathway structural genes (Arce-Rodriguez and Ochoa-Alejo, 2017). Natural variations MYB31 and its elite allele WRKY9 can served as transcription regulation direct targets for pepper pungency levels. These pathways have determined the evolution of extremely pungent peppers (Zhu et al., 2019).

Currently, it remains unclear whether, or not, the members of the R2R3-MYB family have more genes involved in the capsaicinoid biosynthesis process in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and its regulatory network. Thus, 108 CaR2R3-MYB genes were identified in this study in both CM334 pepper and “Zunla-1” pepper genomes. Expression profiles in the pericarp and placenta were determined during fruit development, and co-expression networks of CaR2R3-MYB genes and CBGs were associated with gene structures, phylogenetic relationships, interspecies synteny, and cis-element compositions. The outcomes of this analysis imply that Capana01g000495, Capana02g000906, Capana02g003351, Capana07g001604, Capana08g000900, and Capana08g001690 are candidate CaR2R3-MYB genes involved in capsaicin biosynthesis.

Materials and Methods

The Identification of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors in Pepper

A high-quality draft genome sequence of both hot pepper C. annuum cv. CM334 (Criollo de Morelos 334) (C. annuum Cultivars in Mexico) and a Chinese inbred derivative “Zunla-1” (C. annuum Cultivars in China) were used as reference genomes in this study. A HMM profile of Myb_DNA-binding domain (PF00249) was downloaded from the Pfam database (Elgebali et al., 2019), while HMMER 3.0 was applied to identify MYB family members with E-values ≤ 0.01 threshold (Finn et al., 2011). Protein domains of R2R3-MYBs were validated via SMART-Normal online software (Letunic and Bork, 2018). Protein modeling was predicted using the SWISS-MODEL online tool (Schwede et al., 2003). Theoretical the isoelectric points (PI) and molecular weights (Mw) values were computed using the ExPaSy online tool (Gasteiger et al., 2003), and subcellular localization values were predicted using the Softberry service platform-ProtComp 9.0 (Predict the sub-cellular localization for Plant proteins) online tool1.

Gene Structure, Motifs, and Phylogenetic Analysis

The MEME v5.1.0 online tool (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States) was used to investigate conserved domains. Gene structures were analyzed using the Gene Structure Display Server (Hu et al., 2015). Full-length protein sequences of CaR2R3-MYB from C. annuum were aligned by ClustalW method, and used Gblocks2 online website to extract the gaps. Using unrooted neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree method of MEGA-X with the bootstrap test replicated 1,000 times (Kumar et al., 2018). The genome of Chinese inbred derivative “Zunla-1” acquired from pepper databases was used as the reference genome3.

Chromosomal Location and Synteny Analysis

MCScanX was used to perform gene synteny and collinearity analysis, with match score of 50, gap score of -3, match size of 5, and E-value of 1e–10 parameters to analyze and calculate in-species duplicated genes (Wang et al., 2012). The Circos based Perl approach shows both gene chromosome positions and the synteny relationship of the pepper R2R3-MYB family (Krzywinski et al., 2009). KaKs_Calculator 1.2 were used to estimate the synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates (Zhang et al., 2006).

Cis-Elements Analysis in Promoter Regions

The Bedtools software was used to select the length of 2.0 kb upstream sequence for each gene CDS sequence from its promoter region (Quinlan and Hall, 2010), and to examine cis-regulatory elements of promoter sequences by PlantCARE-Search for CARE website4. Plots are presented using Tbtools (Chen et al., 2020).

Materials and Transcriptome Data Analysis

A high-generation inbred Capsicum line 6421 was used for pepper development experiments. The Pericarp between 10 and 60 DAP (numbered G1–G11), the placenta and seed between 10 and 15 DAP (numbered ST1 and ST2), and the placenta between 20 and 60 DAP (numbered T3–T10) were taken from pepper fruit. The raw data for the transcriptome analysis used in this study were downloaded from Pepper Hub (Liu et al., 2017). The quality of sequencing data was controlled by Fastqc (Brown et al., 2017), and Trimmomatic-0.36 was used to filter the quality of the test data and remove low-quality sequences (Bolger et al., 2014). HISAT2 was used to compare two terminal sequencing reads to the reference genome of “Zunla-1” (Kim et al., 2014). The number of counts was calculated by using FeatureCounts (Yang et al., 2013). The R v3.6.1 language package DESeq2 was used to standardize counts data (Varet et al., 2016). FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) values were calculated to represent the gene expression.

Co-expression Analysis Based on RNA-Seq Data

The weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) package was used in R v3.6.1 language5. RNA-seq data were used to perform WGCNA analysis. The weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) method was used to construct a co-expression network. WGCNA analyzes the gene expression patterns of multiple samples through gene expression data (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008). By calculating the adjacent order function formed by the gene network and the difference coefficients of different nodes, the TOM similarity algorithm calculates the co-expression correlation matrix to express the gene correlation in the network. The correlation network diagram is drawn by extracting the non-weight coefficients (weight) of related CaR2R3-MYB and CBGs in the matrix. Cytoscape v3.6.0 was used to reveal a co-expression plot (Shannon et al., 2003).

Real Time Fluorescence Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA extraction was carried out using the TransZol kit (TransGen Biotech, Inc., Beijing, China). cDNA reverse transcription refers to use of the HiScript®IIQ RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) vazyme kit (Vazyme, Piscataway, NJ, United States). quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was carried out in LightCycle ∗ 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with 25 μL reaction system. Three biological repeats and three technical repeats were used to calculate the relative quantification according to the Ct values collected by the instrument. The formula is: 2−△△Ct = 2−[(Target gene control Ct−Target gene sample Ct)−(Reference gene control Ct−Reference gene sample Ct)]. The actin gene Capana04g001698 was used as reference gene which was selected from pepper. The primers of six CaR2R3-MYB DEGs and four CBGs were developed by GenScript Real-time PCR (TaqMan) Primer and Probes Design Tool6, which were listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Results

Genome-Wide Identification of CaR2R3-MYB Genes

On the basis of a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) MYB profile, there were 216 CaMYB genes in both CM334 and Zunla-1 genomic databases. Amongst CaMYB genes, 108 R2R3 type, two R3 type, one R4 type, and 105 MYB-related types were further classified by searching both Pfam and SMART databases within the pepper genome. Further, comparing CaR2R3-MYBs between Zunla-1 and CM334, 32 homologous gene pairs exhibited different chromosomal annotation information. R2R3 type genes were selected for further analysis and dubbed CaR2R3-MYB. Thus, Zunla-1 CaR2R3-MYBs were mainly used for the remaining analysis of this study.

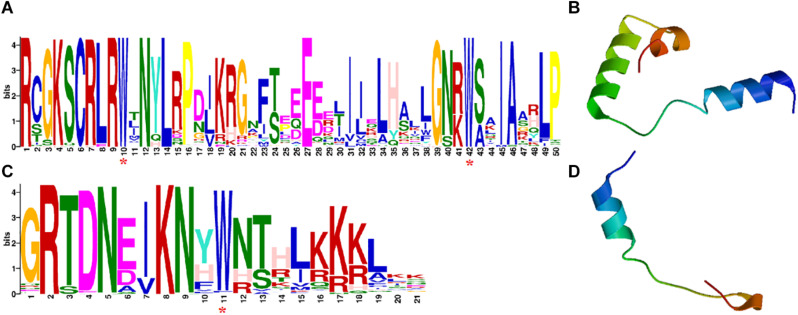

All CaR2R3-MYBs contain two highly conserved MYB binding domains. The motif logo of CaR2R3-MYBs has 50 amino acid residues in the R2 repeat and 21 amino acid residues in the R3 repeat, respectively (Figures 1A,C). The HTH structure of these two domains as revealed by three-dimensional (3D) protein structural models showed that CaR2R3-MYBs matches the typical characteristics of the R2R3-MYB family (Figures 1B,D). Supplementary Table 1 showed that the PI of CaR2R3-MYBs range between 4.76 (Capana06g000131) and 10.18 (Capana05g002248), while the Mw range between 12.6148 KD (Capana07g000392) and 109.76643 KD (Capana11g000012). Subcellular localization prediction revealed that 101 CaR2R3-MYBs are located in the nuclear while three CaR2R3-MYBs are located in the cytoplasmic, three CaR2R3-MYBs are located in the mitochondrial region, and one CaR2R3-MYB (Capana01g002201) is located in the extracellular zone. There were 93.5% CaR2R3-MYBs are transcription factors, the functions of 5.6% CaR2R3-MYBs were related to the cytoplasm and mitochondrial organelles.

FIGURE 1.

The domains of CaR2R3-MYB family genes and protein 3D structural models of R2 and R3 MYB repeats. (A) The R2 domain; (C) the R3 domain. The bit score indicates the information content for each position in the sequence while the purple asterisks below indicate the conserved tryptophan residues (Trp, W). (B) R2 repeats 3D structural model; (D) the R3 repeats 3D structure model.

Gene Structure, Motifs, and Phylogenetic Relationships of the CaR2R3-MYB Family

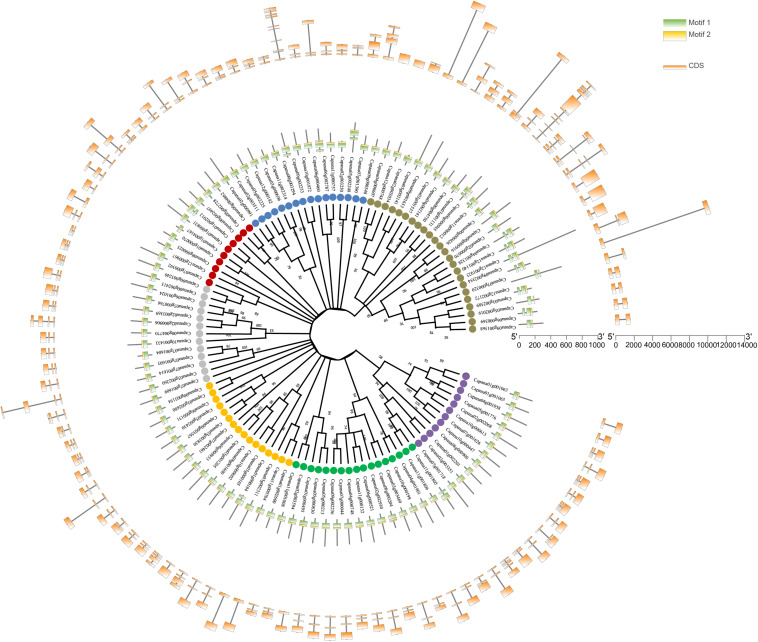

On the basis of statistically of high bootstrapping values, 108 CaR2R3-MYBs were separated into seven main groups in the unrooted phylogenetic tree based on protein sequences. All CaR2R3-MYB genes contained highly conserved MYB binding domains with two typical motifs, R1 and R2. Figure 2 showed the gene structure of exon-intron compositions on the outermost side of the circle. The numbers of exons range between 1 and 10 in CaR2R3-MYBs. Among them, 71 (65.7%) CaR2R3-MYBs have three exons, 22 (20.4%) CaR2R3-MYBs have two exons, seven CaR2R3-MYBs have four exons, four CaR2R3-MYBs have five exons, two CaR2R3-MYBs have five exons, and 10 exons and 11 exons have one CaR2R3-MYB each, respectively. These results revealed a high degree of sequence diversity which indicated that CaR2R3-MYBs may be related to formation mechanisms and evolutionary processes.

FIGURE 2.

Phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, and gene structural analysis of CaR2R3-MYBs. Phylogenetic tree in the middle of 108 CaR2R3-MYBs. This is an unrooted phylogenetic tree constructed via the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Colored dots distinguish seven groups, the distributions of conserved motifs in CaR2R3-MYBs. Two conserved putative motifs are indicated with green and yellow boxes. Exon/intron organization in CaR2R3-MYBs is in the outermost of the circle. Orange boxes represent coding sequence (CDS) regions while black lines show intron regions. Exon length can be inferred via the scale on the right side.

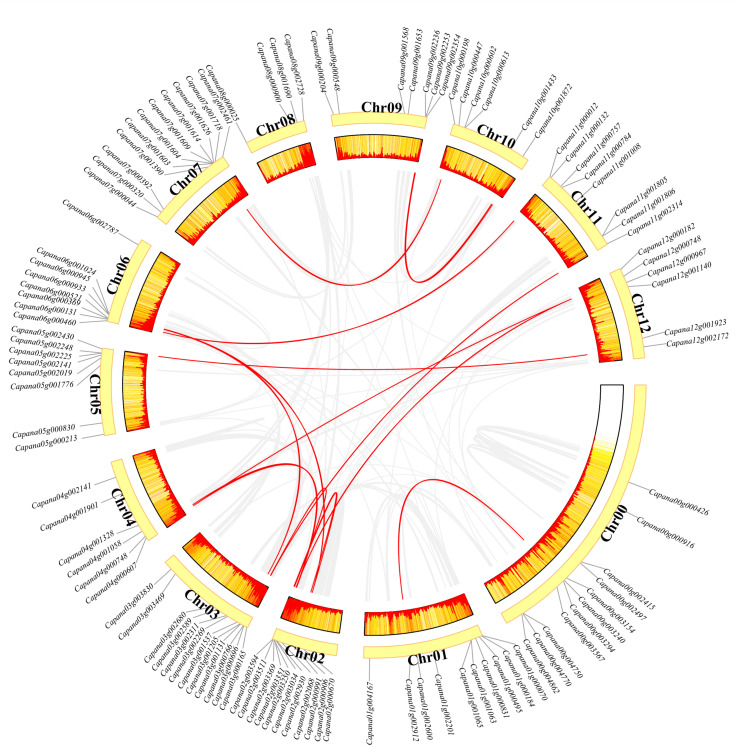

Chromosomal Location and Interspecies Synteny Analysis

All CaR2R3-MYB genes were mapped onto the 12 different chromosomes of the pepper genome including the unclear information “00g” chromosome and “01g” to “12g” chromosomes. Chromosome 00 and chromosome 03 contained most CaR2R3-MYBs (12 genes), while chromosome 01 had 10 CaR2R3-MYBs, chromosome 02 and chromosome 07 harbored 11 CaR2R3-MYBs, chromosome 04, 10, and 12 contained six CaR2R3-MYB genes, chromosome 05, 06, and 11 had eight CaR2R3-MYBs, chromosome 08 harbored four CaR2R3-MYBs, and chromosome 09 contained seven CaR2R3-MYBs (Figure 3). A heatmap showed that gene density on chromosome 03 is the highest and no annotation genes are present at the front of chromosome 00.

FIGURE 3.

Chromosomal location, gene density, and interspecies synteny of CaR2R3-MYBs. The positions of CaR2R3-MYB genes in the pepper genome are marked on chromosomes. A heatmap shows the gene density of each chromosome. Red lines in the middle indicate duplication gene pairs of CaR2R3-MYBs, while grey lines indicate genome duplication gene pairs, and Chr refers to chromosome.

The circos plot also revealed that 16 CaR2R3-MYB duplicated gene pairs are present. Non-synonymous mutation (Ka), synonymous mutation (Ks), and their ratios (Ka/Ks) were calculated to estimate selection pressure in duplicated genes. Ks values ranged between 0.46 and 2.3. In particular, Capana03g000696-Capana11g002314 had no Ks value (NaN), indicating that duplication caused mutation at the nucleic acid level but that the amino acid sequence remained unchanged. The Ka/Ks values of the CaR2R3-MYB duplicated gene pairs ranged between 0.128 and 0.5 (Table 1). Indeed, all Ka/Ks values were less than 1.00 suggesting that CaR2R3-MYB duplicated genes have undergone purifying selection during the evolutionary process. Minimum Ks and maximum Ka/Ks values were observed between the duplicated gene pair Capana03g001205-Capana06g000933, indicating that these two genes might have experienced more purified selection.

TABLE 1.

Duplication models for CaR2R3-MYB gene pairs in pepper.

| Duplicate gene pair | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | AverageS-sites | AverageN-sites |

| Capana00g003276-Capana01g002912 | 0.191183 | 0.719625 | 0.26567 | 72.58333 | 245.4167 |

| Capana02g000906-Capana02g003369 | 0.232616 | 0.816092 | 0.285037 | 189.6667 | 683.3333 |

| Capana02g000991-Capana02g003511 | 0.124785 | 0.635704 | 0.196295 | 120.3333 | 464.6667 |

| Capana02g003369-Capana03g000766 | 0.370969 | 2.304326 | 0.160988 | 193.75 | 688.25 |

| Capana02g003034-Capana04g000607 | 0.275051 | 1.776355 | 0.15484 | 199.0833 | 610.9167 |

| Capana02g002930-Capana04g000748 | 0.494677 | 1.560429 | 0.317013 | 196.6667 | 709.3333 |

| Capana02g000906-Capana06g001024 | 0.390622 | 1.592982 | 0.245214 | 214.9167 | 772.0833 |

| Capana02g003034-Capana12g000748 | 0.453205 | 1.669887 | 0.271399 | 161.6667 | 546.3333 |

| Capana03g001205-Capana06g000933 | 0.236095 | 0.46796 | 0.50452 | 178.3333 | 700.6667 |

| Capana03g000696-Capana11g002314 | 0.469324 | NaN | NaN | 164.25 | 654.75 |

| Capana04g000607-Capana12g000748 | 0.251881 | 1.535706 | 0.164016 | 163.1667 | 562.8333 |

| Capana05g002444-Capana12g002172 | 0.20509 | 1.593561 | 0.128699 | 124.1667 | 445.8333 |

| Capana06g000521-Capana11g000132 | 0.359847 | 0.854725 | 0.421009 | 174.1667 | 689.8333 |

| Capana07g001626-Capana10g000447 | 0.15329 | 0.858551 | 0.178545 | 199.6667 | 742.3333 |

| Capana09g002253-Capana10g001872 | 0.143859 | 0.747546 | 0.192441 | 79.25 | 301.75 |

| Capana09g002354-Capana10g001956 | 0.30921 | 1.488141 | 0.207783 | 220.4167 | 889.5833 |

Ks, Ka, and Ka/Ks values are shown.

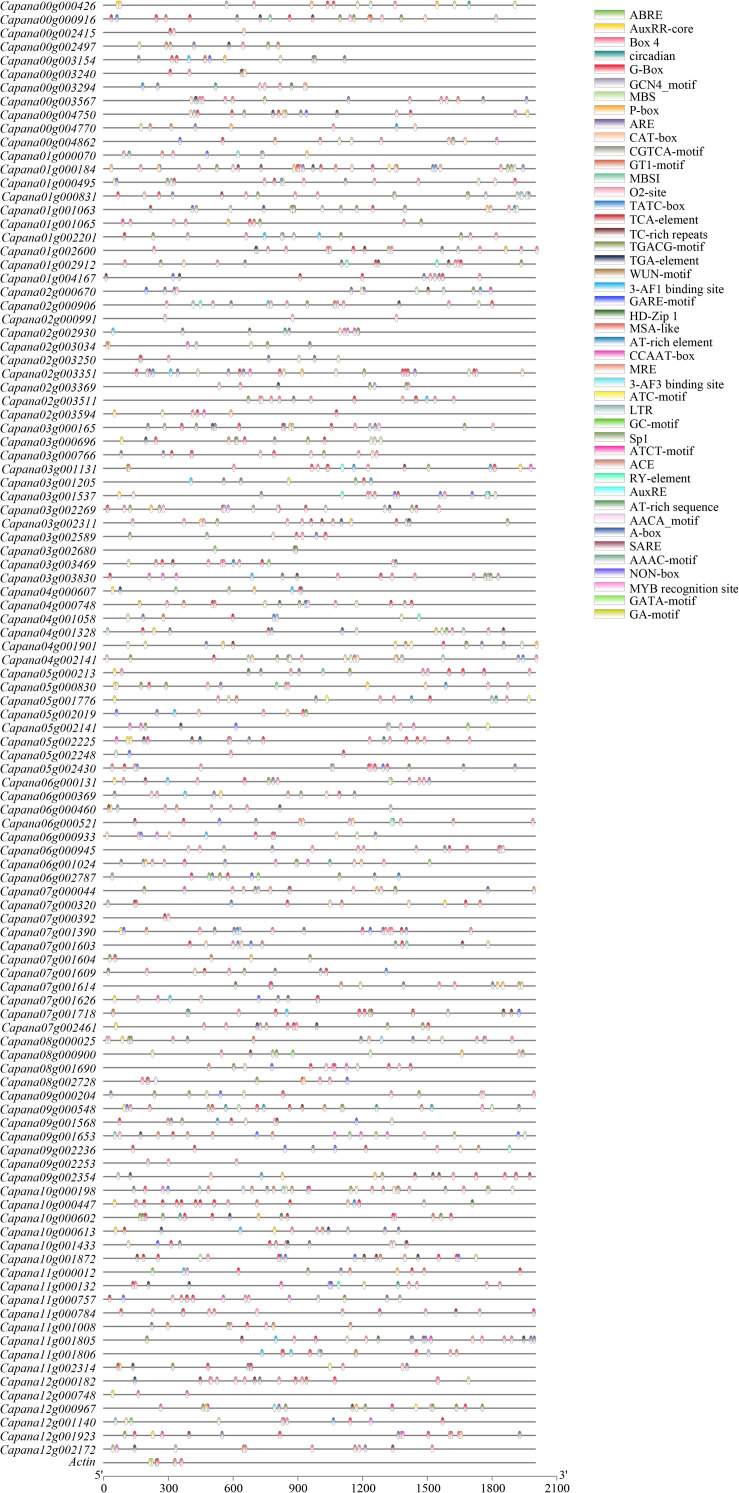

CaR2R3-MYB Putative Cis-Elements in Promoter Regions

The 2,000 base pairs (bp) upstream CaR2R3-MYB genes and actin gene sequences of the coding region were used to predict cis-regulatory elements via the PlantCARE online tool (Figure 4). A total of eight cellular development related cis-regulatory elements of CaR2R3-MYB genes were predicted on this basis, including meristem and endosperm expression, palisade mesophyll cells, flavonoid biosynthetic genes regulation, cell cycle regulation, and seed-specific regulation. There were 13 hormone-related cis-regulatory elements are also present, including abscisic acid, auxin, MeJA-, gibberellin-, and salicylic acid responsiveness as well as zein metabolism regulation. Similarly, 19 stress related cis-elements were also identified including light responsive elements, anaerobic induction, circadian control, anoxic specific inducibility, low-temperature responsiveness, defense and stress responsiveness, and wound-responsiveness. MBS and MRE are specifically MYB binding sites involved in drought-inducibility and light responsiveness (Supplementary Table 2). G-Box, ABRE, GT1-motif, MSA-like, and CCAAT-box were also present in the actin gene promoter region indicating that cis-elements are conserved in the promoter region of pepper genes.

FIGURE 4.

Predicted cis-elements in CaR2R3-MYBs promoters. Promoter sequences (−2,000 bp) of CaR2R3-MYBs and one actin gene were analyzed using PlantCARE. Different shapes and colors represent different elements. Annotations of cis-elements are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Expression of Capsaicinoid-Biosynthetic Genes and CaR2R3-MYB DEGs

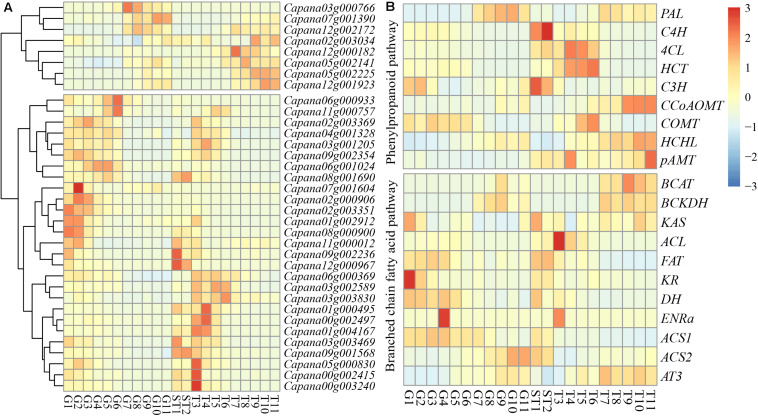

RNA-seq data from the pericarp between 10 days after germination (DAP) and 60 DAP, as well as from the placenta and seed between 10 and 15 DAP, and the placenta between 20 and 60 DAP were used to determine expression levels of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs and CBGs. A total of 35 (32.4%) CaR2R3-MYB DEGs of CaR2R3-MYB family genes from the pericarp between 10 and 60 DAP (adjust P-value < 0.01, | Log2foldchange| > 1) were identified. Nine DEGs were down-regulated while 26 genes were up-regulated (Supplementary Figure 1). The expression of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs can be separated into two groups (Figure 5A); the first part of expression levels was higher in late stage pericarp and placenta. There were eight CaR2R3-MYB DEGs in this part, of which seven were down-regulated genes. The expression of the other part was higher in the early stage of the pericarp, placenta and seed, and placenta, which contained 27 CaR2R3-MYB DEGs. Indeed, data suggested that CaR2R3-MYB genes are widely involved in the regulation of pepper fruit development process. The expression levels of CBGs in the capsaicinoid biosynthetic pathway were also identified (Figure 5B); C3H, COMT, KAS, FAT, KR, DH, ENRa, and ACS1 were highly expressed in the early stage of the pericarp. Throughout the placenta and seed development process, C4H, C3H, FAT, and DH were significantly expressed between 10 and 15 DAP. Data showed that 4CL, HCT, ACL, and ENRa were highly expressed in the early stage of the placenta, while CCoAOMT, HCHL, pAMT, BCAT, BCKDH, KAS, and AT3 were highly expressed in the late stage of the placenta.

FIGURE 5.

Expression patterns of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs and CBGs. Expression profiles using RNA-seq Fragments Per Kilobase Million (FPKM) data in the pericarp between ten DAP and 60 DAP (G1-G11), placenta and seed between ten DAP and 15 DAP (ST1 and ST2), and the placenta between 20 DAP and 60 DAP (T3-T10). (A) CaR2R3-MYB DEGs expression level (B) CBGs. CBGs including PAL: phenylalanine ammonia lyase; C4H: cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; 4CL: 4-coumaroyl-CoA ligase; HCT: hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; C3H: coumaroylshikimate/quinate 3-hydroxylase; CCoAOMT: caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase; COMT: caffeic acid O-methyl transferase; HCHL: hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA hydratase/lyase; pAMT: putative aminotransferase; in phenylpropanoid pathway, and BCAT: branched-chain amino acid transferase; KAS: ketoacyl-ACP synthase; ACL: acyl carrier protein; FAT: acyl-ACP thioesterase; ENR, enoyl-ACP reductase; KR, ketoacyl-ACP reductase; DH, hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydratase; ACS: acyl-CoA synthetase; AT: acyltransferase; in branched chain fatty acid pathway. The color scale at the left of each dendrogram represents log2 expression values, with red indicating high levels and blue indicating low levels of transcript abundance.

Co-expression Analysis of Capsaicinoid-Biosynthetic Genes and CaR2R3-MYBs

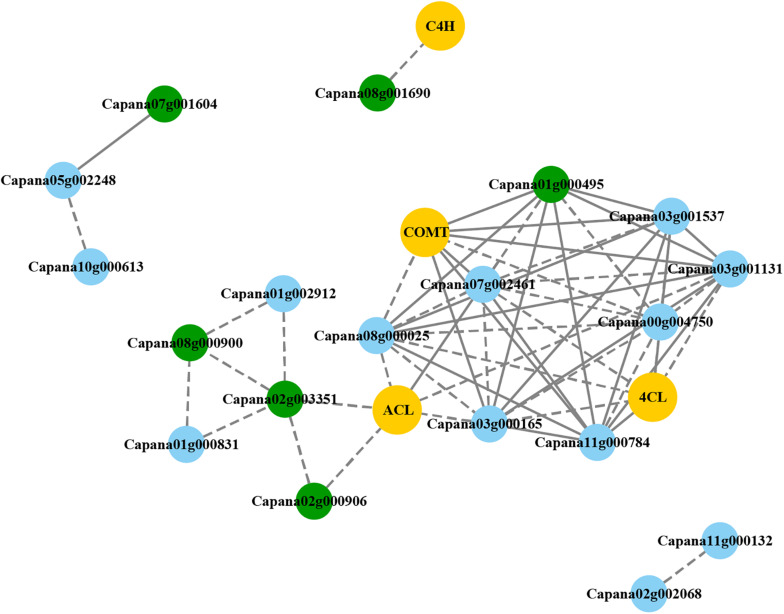

The expression levels of 108 CaR2R3-MYB, 35 CaR2R3-MYB DEGs, and 20 CBGs were used to predict candidate CaR2R3-MYB genes related to capsaicin synthesis. As shown in Figure 6, 19 CaR2R3-MYB genes are co-expressed with four CBGs. Indeed, in the phenylpropanoid pathway, C4H was co-expressed with Capana08g001690, while COMT was highly co-expressed with Capana07g002461, Capana03g000165, Capana11g000784, Capana03g001537, and Capana00g004750. Similarly, 4CL was co-expressed with Capana11g000784, and Capana03g001537. In a branched chain fatty acid pathway, ACL was co-expressed with Capana02g003351, Capana02g000906, Capana07g002461, Capana03g000165, Capana11g000784, Capana03g001537, Capana01g000495, Capana08g000025, Capana03g001131, and Capana00g004750. Six CaR2R3-MYB genes (Capana01g000495, Capana02g000906, Capana02g003351, Capana07g001604, Capana08g000900, and Capana08g001690) in the co-expression network were DEGs in the pericarp between 10 and 60 DAP. Data showed that these six CaR2R3-MYB DEGs are the candidate genes involved in capsaicin or capsanthin synthesis processes.

FIGURE 6.

Co-expression networks of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs and CBGs. Yellow boxes denote CBGs, blue boxes denote CaR2R3-MYB genes, and green boxes denote CaR2R3-MYB DEGs. The solid line indicates that the co-expression weight is higher, while the dotted line indicates that the co-expression weight is lower.

The real-time qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the transcription levels of Capana01g000495, Capana02g000906, Capana02g003351, Capana07g001604, Capana08g000900, and Capana08g001690 (Figure 7). Results illustrated that qRT-PCR and RNA-seq expression levels were similar for all six CaR2R3-MYB DEGs (Supplementary Figure 2). In terms of progressing fruit development, expression levels of Capana02g003351 and Capana08g000900 kept decreasing, while expression levels of Capana01g000495, Capana07g001604, Capana02g000906, and Capana08g001690 first increased and then decreased. It is revealed that these six CaR2R3-MYB genes play key roles as candidate genes in capsaicin synthesis.

FIGURE 7.

qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data of six candidate CaR2R3-MYB genes. Pericarp samples from G1, G3, G5, G7, and G10 show a series of expression changes in candidate CaR2R3-MYB genes. The orange line represents the qRT-PCR level while the blue line represents the RNA-seq level. CBGs are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Discussion

Identification and Characterization of CaR2R3-MYB Genes

Pepper (Capsicum) is famous for its spiciness and is an economically important Solanaceae family crop cultivated globally for its nutritional benefits. Reference genome sequencing of the two varieties of pepper cultivars, CM334 (Mexico), and Zunla-1 (Guizhou, China), was completed in 2014 (Kim et al., 2014; Qin et al., 2014). In the pepper genome, however, gene families have been widely identified via incomplete annotation files. A total of 104 CaNAC genes (Diao et al., 2018), 35 mTERF genes (CamTERFs) (Tang et al., 2019), nine CaCBL, and 26 CaCIPK genes in the pepper genome (Ma et al., 2019). Here, 108 CaR2R3-MYBs were identified in both the CM334 and Zunla-1 genome, less than those identified in Arabidopsis thaliana (Stracke et al., 2001). The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool Protein (BLASTP) was used to align homologous genes in these two genomes. Thus, 11 CaR2R3-MYBs had “00g” chromosomal records in the Zunla-1 genome (also annotated in the CM334 genome), while seven CaR2R3-MYBs had chromosomal annotation in the Zunla-1 genome but no records in the CM334 genome (Supplementary Table 1). The complementarity of CM334 and “Zunla-1” can contribute to improve the complete annotation of the pepper genome. A chromosomal location circos plot illustrates that CaR2R3-MYBs are distributed evenly among every chromosome.

In order to study the evolution and transcriptional features of CaR2R3-MYBs, the number and distribution of introns and exons were analyzed. The number of CDS in the CaR2R3-MYB gene varies between 1 and 10, with the largest number of genes in three exons. Genes within the same subclass have similar structures and predicted motifs. These results indicate that the gene structure of CaR2R3-MYBs is highly conserved; a total of 16 CaR2R3-MYB duplicated gene pairs were identified via interspecies synteny analysis. The existence of duplicated genes is the main reason for CaR2R3-MYB gene amplification, one reason for the large number of family genes (Wang et al., 2013). A phylogenetic tree was constructed using cluster analysis such that CaR2R3-MYBs were divided into seven subclasses. As a result of highly conserved features, CaR2R3-MYBs within the same subclass tended to have similar functions.

Different cis-regulatory elements in the promoter sequences of genes may produce different expression patterns (Islam et al., 2019). A total of eight cellular development related cis-regulatory elements, 19 stress related cis-elements, and 13 hormone-related cis-regulatory elements were present. This analysis demonstrates that most CaR2R3-MYBs have divergent regulatory elements compared with the actin gene. The CaR2R3-MYB gene family has highly different cis-regulatory elements in the promoter region, which may lead to CaR2R3-MYB gene functional divergence at the transcriptional level (Haberer et al., 2004).

Capsaicin Biosynthesis Related Expression Level of CaR2R3-MYBs

R2R3-MYB is recognized as the dominant MYB type gene with the largest number of members in most plants, widely involved in the regulation of plant morphogenesis, growth, metabolism, developmental processes, and responses to biotic or abiotic stresses (Rosinski and Atchley, 1998). In pepper plants, R2R3-MYB transcription factors also play significant roles. Virus-induced gene silencing has revealed that MYB and WD40 are involved in the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in chili pepper fruits (Aguilar-Barragan and Ochoa-Alejo, 2014), while the R2R3-MYB transcription factor and homolog gene may play a major role in abiotic stress signaling pathways (Seong et al., 2008). Three R2R3-MYB transcription factor genes, CaMYB1, CaMYB2, and CaMYB3, from C. annuum exhibited differential expression during fruit ripening (Guo et al., 2011).

R2R3-MYBs also play a specific regulatory role in the pepper capsaicin synthesis pathway. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor CaMYB31 is therefore also a candidate to control pungency in C. annuum; it is known that Jasmonate-Inducible CaMYB108, a typical R2R3-MYB gene, regulates capsaicinoid biosynthesis and stamen development in Capsicum (Sun et al., 2019). Capsaicin R2R3-MYB candidate genes were screened in this study and analyzed using pepper RNA-seq data. This enabled investigation of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs in pericarp, placenta and seed, and placenta. The expression levels of the 26 up-regulated DEGs in the early stages of pericarp, placenta and seed, as well as placenta development are typically increased. This illustrates that up-regulated CaR2R3-MYB DEGs respond during capsaicin synthesis.

The expression of CaR2R3-MYB DEGs is tissue-specific during plant development. Partial CaR2R3-MYB DEGs have the highest expression levels in the pericarp, while other genes are expressed in the placenta, remarkable tissue-specific expression differences. Partial genes such as Capana03g001205, Capana04g001328, Capana02g003369, Capana11g000757, and Capana09g002354 have almost detectable expressions in the early stages of both pericarp and placenta. Family genes only contain the duplicate gene pairs of Capana02g000906-Capana02g003369 and Capana02g000906-Capana06g001024; in Capsicum species, several key CBGs are also expressed at early stages in the pericarp, placenta and seed, and placenta. In both phenylpropanoid and branched chain fatty acid pathways, expression levels of CBGs in this treatment are similar to those previously determined (Kim et al., 2014). Numerous CaR2R3-MYB family genes are related to CBGs in expression level, indicating that CaR2R3-MYB genes may directly or indirectly participate in the capsaicinoid biosynthesis.

In the co-expression network of capsaicinoid biosynthetic pathway, MYB31 was co-expressed with 174 genes; amongst these co-expressed genes, 15 have been previously reported to be involved in CAPD biosynthesis (Zhu et al., 2019). Genes in the CaR2R3-MYB family co-expression network were identified; 19 were selected in the pericarp, placenta and seed, and placenta development process, which were co-expressed with CBGs that might be involved in capsaicinoid biosynthetic synthesis. Divergence expression of CaR2R3-MYB genes shape the pungent diversification in peppers. Six CaR2R3-MYB DEGs are candidate capsaicinoid biosynthetic related genes in this study, including MYB31 and other five CaR2R3-MYB. This research systematically studied the main characteristics of the CaR2R3-MYB gene family, and also provides an important reference for the study of transcription factors related to the capsaicin synthesis pathway. This study provides comprehensive information about pepper R2R3-MYB genes and can help determine the function of pepper R2R3-MYB genes. It also provides important candidate genes for capsaicinoid biosynthesis research.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn/.

Author Contributions

XZ, FL, XD, and JW designed the research. JW, YL, and BT conducted the experiments. JW and YL analyzed the data. JW wrote the manuscript. FL, LX, and JW revised the manuscript and improved the English. XZ and FL acquired the funding. All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U19A2028).

Softberry: http://www.softberry.com

“Zunla-1” Reference Genome: http://peppersequence.genomics.cn/

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.598183/full#supplementary-material

The DEGs of CaR2R3-MYB in pepper between pericarp in different stages (adjust P-value < 0.01, | Log2foldchange| > 1). Orange bars are up-regulated genes and blue are down-regulated DEGs.

qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data of four CBGs.

Expression patterns of capsaicinoid-biosynthetic related CaR2R3-MYB genes.

The basic information of R2R3-MYB gene family in Capsicum. List of predicted genes and related information include gene name (Zunla_1), CM334 homologous gene and gene locus, molecular details, and predicting subcellular localization.

Genes and primers used in the quantitative real-time PCR.

Cis-regulatory elements annotations.

References

- Aguilar-Barragan A., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2014). Virus-induced silencing of MYB and WD40 transcription factor genes affects the accumulation of anthocyanins in chilli pepper fruit. Biol. Plant. 58 567–574. 10.1007/s10535-014-0427-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arce-Rodriguez M. L., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2015). Silencing AT3 gene reduces the expression of pAmt, BCAT, Kas, and Acl genes involved in capsaicinoid biosynthesis in chili pepper fruits. Biol. Plant. 59 477–484. 10.1007/s10535-015-0525-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arce-Rodriguez M. L., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2017). An R2R3-MYB transcription factor regulates capsaicinoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 174 1359–1370. 10.1104/pp.17.00506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce-Rodriguez M. L., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2019). Biochemistry and molecular biology of capsaicinoid biosynthesis: recent advances and perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 38 1017–1030. 10.1007/s00299-019-02406-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aza-González C., Núñez-Palenius H. G., Ochoa-Alejo N. (2011). Molecular biology of capsaicinoid biosynthesis in chili pepper (Capsicum spp.). Plant Cell Rep. 30 695–706. 10.1007/s00299-010-0968-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Marc L., Bjoern U. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Pirrung M., Mccue L. A. (2017). FQC dashboard: integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive, and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics 33 3137–3139. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. J., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H. R., Frank M. H., He Y., et al. (2020). TBtools – an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13 1194–1202. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Suh B., Kozukue E., Kozukue N., Levin C., Friedman M. (2006). Analysis of the contents of pungent compounds in fresh korean red peppers and in pepper-containing foods. J. Agr. Food Chem. 54 9024–9031. 10.1021/jf061157z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao W., Snyder J. C., Wang S., Liu J., Pan B., Guo G., et al. (2018). Genome-wide analyses of the NAC transcription factor gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.): chromosome location, phylogeny, structure, expression patterns, cis-elements in the promoter, and interaction network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:1028. 10.3390/ijms19041028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C., Stracke R., Grotewold E., Weisshaar B., Martin C., Lepiniec L. (2002). MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 15 573–581. 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgebali S., Mistry J., Bateman A., Eddy S. R., Luciani A., Potter S. C., et al. (2019). The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 D427–D432. 10.1093/nar/gky995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Clements J., Eddy S. R. (2011). HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 29–37. 10.1093/nar/gkr367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E., Gattiker A., Hoogland C., Ivanyi I., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. M. (2003). ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3784–3788. 10.1093/nar/gkg563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates D. J., Strickler S. R., Mueller L. A., Olson B. J., Smith S. D. (2016). Diversification of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in the tomato family Solanaceae. J. Mol. Evol. 83 26–37. 10.1007/s00239-016-9750-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L. J., Liang L. H., Peng S. Q. (2011). Three R2R3-MYB transcription factor genes from Capsicum annuum showing differential expression during fruit ripening. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10 8267–8274. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer G., Hindemitt T., Meyers B. C., Mayer K. F. (2004). Transcriptional similarities, dissimilarities, and conservation of cis-elements in duplicated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 136 3009–3022. 10.1104/pp.104.046466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Jin J., Guo A., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. (2015). GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31 1296–1297. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam S., Sajib S. D., Jui Z. S., Arabia S., Ghosh A. (2019). Genome-wide identification of glutathione S-transferase gene family in pepper, its classification, and expression profiling under different anatomical and environmental conditions. Sci. Rep. 9:15. 10.1038/s41598-019-45320-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Clegg M. T., Jiang T. (2004). Evolutionary dynamics of the DNA-binding domains in putative R2R3-MYB genes identified from rice subspecies indica and japonica genomes. Plant Physiol. 134 575–585. 10.1104/pp.103.027201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyhaninejad N., Curry J., Romero J., Oconnell M. A. (2014). Fruit specific variability in capsaicinoid accumulation and transcription of structural and regulatory genes in Capsicum fruit. Plant Sci. 21 59–68. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Park M., Yeom S. I., Kim Y. M., Lee J. M., Lee H. A., et al. (2014). Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nat. Genet. 46 270–278. 10.1038/ng.2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeda S., Sato K., Saito H., Nagano A. J., Yasugi M., Kudoh H., et al. (2019). Mutation in the putative ketoacyl-ACP reductase CaKR1 induces loss of pungency in Capsicum. Theor. Appl. Genet. 132 65–80. 10.1007/s00122-018-3195-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M., Schein J. E., Birol I., Connors J. M., Gascoyne R. D., Horsman D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35 1547–1549. 10.1093/molbev/msy096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder P., Horvath S. (2008). WGCNA, an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 9:559. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2018). 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 D493–D496. 10.1093/nar/gkx922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Yu H., Deng Y., Zheng J., Liu M., Ou L., et al. (2017). PepperHub, an informatics HUB for the chili pepper research community. Mol. Plant 10 1129–1132. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li W., Wu Y., Chen C., Lei J. (2013). De Novo Transcriptome assembly in chili pepper (Capsicum frutescens) to identify genes involved in the biosynthesis of capsaicinoids. PLoS One 8:e48156. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Gai W., Qiao Y., Ali M., Wei A., Luo D., et al. (2019). Identification of CBL and CIPK gene families and functional characterization of CaCIPK1 under Phytophthora capsici in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). BMC Genomics 20:18. 10.1186/1471-2229-14-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves E. R., Silva L. D., Sulpice R., Araujo W. L., Nunesnesi A., Peres L. E., et al. (2019). Capsaicinoids: pungency beyond Capsicum. Trends Plant Sci. 24 109–120. 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Yu C., Shen Y., Fang X., Chen L., Min J., et al. (2014). Whole-genome sequencing of cultivated and wild peppers provides insights into Capsicum domestication and specialization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 5135–5140. 10.1073/pnas.1400975111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R., Hall I. M. (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26 841–842. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosinski J. A., Atchley W. R. (1998). Molecular evolution of the Myb family of transcription factors: evidence for polyphyletic origin. J. Mol. Evol. 46 74–83. 10.1007/PL00006285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (2003). SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3381–3385. 10.1073/pnas.0807484105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong E. S., Guo J., Wang M. H. (2008). The chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum) MYB transcription factor (CaMYB) is induced by abiotic stresses. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 17 193–196. 10.1007/BF03263285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Wang N. S., Ramage J. T. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C., Kang B., Liu K., Mazourek M., Moore S., Yoo E. Y., et al. (2005). The Pun1 gene for pungency in pepper encodes a putative acyltransferase. Plant J. 42 675–688. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C., Mazourek M., Stellari G. M., Oconnell M. A., Jahn M. (2007). Genetic control of pungency in C. chinense via the Pun1 locus. J. Exp. Bot. 58 979–991. 10.1093/jxb/erl243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R., Werber M., Weisshaar B. (2001). The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4 447–456. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00199-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B., Zhu Z., Chen C., Chen G., Cao B., Chen C., et al. (2019). Jasmonate-inducible R2R3-MYB transcription factor regulates capsaicinoid biosynthesis and stamen development in Capsicum. J. Agr. Food Chem. 67 10891–10903. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b04978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Asano T., Kanemitsu Y., Goto T., Yoshida Y., Yasuba K., et al. (2019). Positional differences of intronic transposons in pAMT affect the pungency level in chili pepper through altered splicing efficiency. Plant J. 100 693–705. 10.1111/tpj.14462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B., Xie L., Yi T., Lv J., Yang H., Cheng X., et al. (2019). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the mitochondrial transcription termination factors (mTERFs) in Capsicum annuum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:269. 10.3390/ijms21010269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury J. J., Reagan K. M., Machnicki N. J., Carlo T. A., Haak D. C., Penaloza A. L., et al. (2008). Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 11808–11811. 10.1073/pnas.0802691105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varet H., Brilletgueguen L., Coppee J., Dillies M. (2016). SARTools: a DESeq2- and EdgeR-based R pipeline for comprehensive differential analysis of RNA-Seq data. PLoS One 11:e0157022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Wettsteinknowles P., Olsen J. G., Mcguire K. A., Larsen S. (2000). Molecular aspects of β-ketoacyl synthase (KAS) catalysis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 28 601–607. 10.1042/BST0280601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Liu Y., Chen X. L., Kong Q. S. (2020). Characterization and divergence analysis of duplicated R2R3-MYB genes in watermelon. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 145 1–8. 10.21273/JASHS04849-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tan X., Paterson A. H. (2013). Different patterns of gene structure divergence following gene duplication in Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics 14:652. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tang H., Debarry J. D., Tan X., Li J., Wang X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e49. 10.1093/nar/gkr1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Smyth G. K., Wei S. (2013). FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30 923–930. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Li J., Zhao X., Wang J., Wong G., Yu J. (2006). KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 4 259–263. 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Sun B., Cai W., Zhou X., Mao Y., Chen C., et al. (2019). Natural variations in the MYB transcription factor MYB31 determine the evolution of extremely pungent peppers. New Phytol. 223 922–938. 10.1111/nph.15853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The DEGs of CaR2R3-MYB in pepper between pericarp in different stages (adjust P-value < 0.01, | Log2foldchange| > 1). Orange bars are up-regulated genes and blue are down-regulated DEGs.

qRT-PCR and RNA-seq data of four CBGs.

Expression patterns of capsaicinoid-biosynthetic related CaR2R3-MYB genes.

The basic information of R2R3-MYB gene family in Capsicum. List of predicted genes and related information include gene name (Zunla_1), CM334 homologous gene and gene locus, molecular details, and predicting subcellular localization.

Genes and primers used in the quantitative real-time PCR.

Cis-regulatory elements annotations.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://pepperhub.hzau.edu.cn/.