Abstract

Background:

Oncologic treatment has been associated with unemployment. As endometrial cancer is highly curable, it is important to assess whether patients experience employment disruption after treatment. We evaluated the frequency of employment change following endometrial cancer diagnosis, and assessed factors associated with a disruption in employment.

Methods:

A cohort of patients 18–63 years-old who were diagnosed with endometrial cancer (January 2009- December 2017) were identified in the Truven MarketScan database, an insurance claims database of commercially insured patients in the United States. All patients who were working full or part-time at diagnosis were included, and all employment changes during the year following diagnosis were identified. Clinical information, including use of chemotherapy and radiation, were identified using Common Procedural Terminology codes, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases codes. Cox proportional hazards models incorporating measured covariates were used to evaluate the impact of treatment and demographic variables on change in employment status.

Results:

A total of 4,381 women diagnosed with endometrial cancer who held a full-time or part-time job 12 months prior to diagnosis were identified. Median age at diagnosis was 55 and a minority of patients received adjuvant therapy; 7.9% received chemotherapy, 4.9% received external-beam radiation therapy, and 4.1% received chemoradiation. While most women continued to work following diagnosis, 21.7% (950) experienced a change in employment status. The majority (97.7%) of patients had a full-time job prior to diagnosis. In a multivariable analysis controlling for age, region of residence, comorbidities, insurance plan type and presence of adverse events, chemoradiation recipients were 34% more likely to experience a disruption in employment (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.01–1.78), compared to those who only underwent surgery.

Conclusion:

Approximately twenty-two percent of women with employer-subsidized health insurance experienced a change in employment status following the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, an often-curable disease. Chemoradiation was an independent predictor of change in employment.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, with more than 600,000 survivors estimated in 2020 [1]. While surviving this cancer is a common and welcome outcome, survivorship can be challenging given increasing medical expenditures [2,3], multiple surveillance visits, and the difficulty of managing long-term treatment side effects. Cancer survivorship has also been associated with unemployment, and 40–54% of adult cancer survivors report a decrease in work hours or cessation of work altogether after their diagnosis [4–7]. In patients with endometrial cancer, where over half of women will be younger than 65 [8], and more than 80% will survive beyond 5 years after their diagnosis [8], the impact of underemployment following endometrial cancer diagnosis could be substantial. Though short-term leave allows cancer patients to receive treatment, longer-term absences or permanent exit from the workforce could lead to loss of wages, job security, and employer-subsidized health insurance. Beyond the role of work in ensuring financial security, it is also an important component of restoring a sense of normality and psychological well-being [9], social interaction, and purpose in life after cancer [10].

While endometrial cancer is second only to breast cancer as the most common cancer among female survivors in the United States [11], data examining employment interruptions in endometrial cancer survivors are sparse and limited to single institution studies [12–14]. In studies including primarily breast cancer survivors, receipt of chemotherapy [15–17], older age [18], race [17,18], advanced cancer [17,19], type of insurance [18], and demanding jobs [17] have been associated with a disruption in employment.

The financial burden of cancer care in the setting of prolonged survival makes unemployment an important survivorship issue. Understanding the rates of employment disruption and factors that predict it could lead to more informative discussions about survivorship expectations and would allow for early intervention in groups of patients that are less likely to be re-employed following their treatment. Our goal was to characterize, in a population-based study, the proportion of patients who experienced a change in their workhours following endometrial cancer treatment and generate hypotheses about factors that predict employment disruption.

Methods

Data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of endometrial cancer patients identified in the Truven MarketScan database (IBM Watson Health, Cambridge, MA), an administrative claims database containing private insurance claims from approximately 150 large employers in the United States, which represents a national convenience sample of approximately 50 million patients under age 65 with employer-sponsored health insurance. De-identified patient-level inpatient and outpatient medical, procedural and pharmaceutical claims data can be abstracted from health insurance beneficiaries from more than 300 employer-sponsored health plans [20]. We utilized insurance claims from January 2009 through December 2017.

Cohort assembly

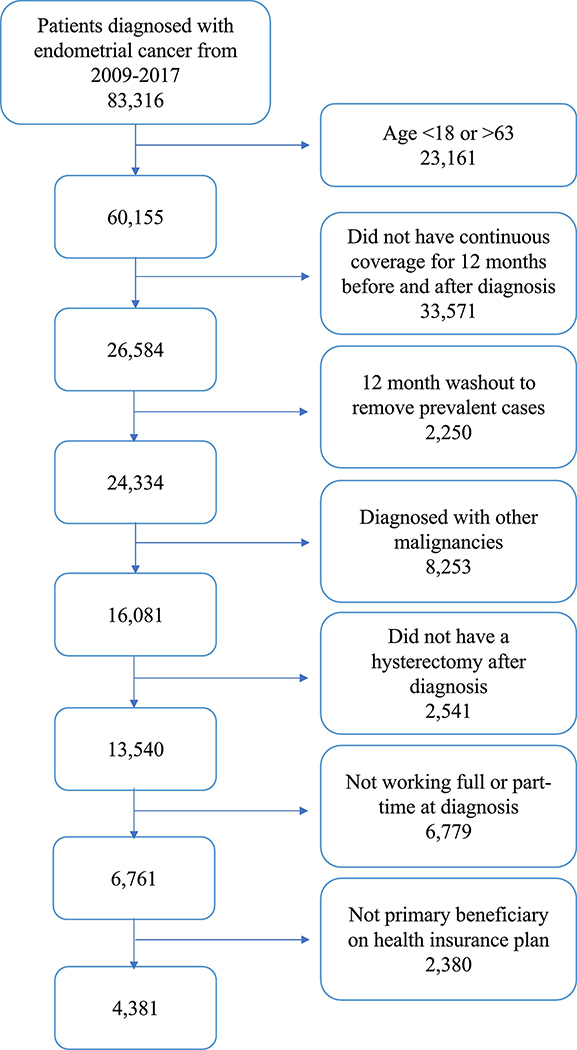

Our cohort included adult patients 18–63 years old who received a diagnosis of endometrial cancer using codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Editions [ICD-9, 182.0; ICD-10, C54.x] from 2009–2017 and were working full- or part-time at the time of diagnosis (Figure 1). To be included, patients had to receive an endometrial cancer diagnosis code in at least one inpatient claim [21] or at least two outpatient claims, 30 days apart [22]. Based on a validated algorithm to identify incident endometrial cancer cases, [22] we required a 12-month wash-out period without an endometrial cancer diagnosis code (ICD-9, ICD-10 see supplementary table 1) prior to the earliest endometrial cancer diagnosis in the study period. Therefore, we restricted our cohort to patients who were continuously covered for the 12 months before through the 12 months after their cancer diagnosis. As in a similar study [16], we included women enrolled through the first year following diagnosis as most cancer treatments would occur during this time. In addition, we only included patients who were the primary beneficiaries on their health-insurance plans to ensure that we were collecting the patient’s employment status and not her spouse’s. Patients with other cancer diagnoses were excluded. We also excluded women that did not undergo a hysterectomy for endometrial cancer following diagnosis, (identified by Common Procedural Terminology [CPT] codes) as we assumed these women were potentially medically unfit for surgery, had advanced-stage disease, recurrent disease, or had received fertility-sparing treatment with progestins. In these cases, we expect patients would have different employment outcomes than women undergoing standard treatment for newly diagnosed early-stage endometrial cancer. Finally, women with unavailable employment data and those who were not working full or part-time at the time of cancer diagnosis were excluded.

Fig. 1.

Cohort identification for endometrial cancer patients who were employed full-or part-time at diagnosis.

Employment status determination

The primary outcome of this study was the proportion of patients who experienced a change in employment after the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. To determine employment status at the time of diagnosis, we used definitions provided by the Truven MarketScan database that reflect categories reported by employer-sponsored health plans: full-time, part-time, early retiree, Medicare-eligible retiree, retiree (status unknown), Comprehensive Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA), long term disability, or other/unknown. Only women who were known to be working “full-time” or “part-time” at the time of their endometrial cancer diagnosis were included in the cohort. For the 12 months following diagnosis we recorded employment status on a monthly basis, using the aforementioned categories. A change in employment was noted when a patient who was working full- or part-time at diagnosis changed her status to any of the other categories. We assumed that each change in employment category following full- or part-time employment was associated with a decrease in the number of working hours or cessation of work altogether. This applied to the other/unknown category as well, because the change in status indicated that the patient was no longer working at her old job, and we assumed that the likelihood that a patient will start a new full-time job while receiving cancer treatment or recovering from surgery was low [16]. Patients were censored after their first employment change. Given that MarketScan does not link data among different employers we did not assess return to work following a change in employment status.

Patient characteristics

The secondary objective of this study was to assess available clinical factors associated with change in employment. We abstracted the following data: age at diagnosis, health plan type (health maintenance organization [HMO], preferred provider organization [PPO], Consumer-driven health plan [CDHP] or other), region of residence (northeast, north central, south, west), and year of diagnosis. The Klabunde modification of the Charlson comorbidity index [23] was used to assess for non-cancer related comorbidity; a score of zero meant that none of the included comorbidities were present. MarketScan does not contain other important covariates such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, and we were unable to include these variables in our analysis.

Receipt of adjuvant external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or chemotherapy was identified using ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes and CPT codes. Adjuvant treatment for endometrial cancer was categorized as follows: none, EBRT, chemotherapy, and chemoradiation (chemotherapy + EBRT). Given that brachytherapy was not expected to significantly contribute to toxicity [24], and in the setting of a limited sample size, we did not include receipt of brachytherapy in our model. In a secondary model we evaluated receipt of any adjuvant therapy compared to surgery alone.

Similarly, we used ICD-9/ICD-10 and CPT codes to identify the following adverse events: gastrointestinal complications, venous thrombo-embolic disease, fistula formation, hematologic complications, lymphedema, and infectious complications (pneumonia, sepsis, surgical site infection, deep abscess, urinary tract infection, clostridium difficile) in the year following diagnosis. Patients were categorized as follows: no events, 1 event, and 2 or more events. Finally, we identified metastatic disease using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for “secondary malignant neoplasm”, a term that is generally accepted as indicative of metastatic disease (supplementary table 1) in other anatomic sites [16,25].

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. The student’s t-test was utilized to assess differences in means of continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to assess the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics between those who experienced and those who did not experience a change in employment. A non-parametric trend test was employed to assess whether the proportion of patients who experienced an employment change varied over time. To adjust for unequal follow-up time, a Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (HR), and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were utilized to assess the importance of treatment group as an independent predictor of employment disruption when adjusting for age, insurance plan type, region of residence, year of diagnosis, comorbidity index score, and presence of adverse events. All statistical tests were 2-sided. A P-value < 0.05 and 95% CI not inclusive of the null (1.0) were considered statistically significant. All analyses were implemented in SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.11 (SAS Institute Inc.) This project was approved by our Institutional Review Board (protocol # 2020-0367).

Results

Of those reported to the Truven Marketscan database, we identified 83,316 patients who were diagnosed with endometrial cancer from January 2009 to December 2017. Prior to exclusions, 28.0% (n= 23,328) of patients were working full or part-time at the time of diagnosis. Briefly, we excluded the following patients: 23,161 based on age at diagnosis; 33,571 for inadequate continuous coverage; 2,250 prevalent cases; 8,253 patients with other malignancies; 2,541 who did not have a hysterectomy in the year following diagnosis; 6,779 who were not working full or part-time at diagnosis; and 2,380 who were not the primary beneficiaries on their health insurance plan. Therefore, our cohort included 4,381 patients who were working full or part-time when they were diagnosed. The entire cohort selection process is depicted in Figure 1, and the baseline characteristics of the included patients are displayed in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 55 (inter-quartile range 49–59) and the majority of patients had no co-morbidities, metastatic disease, or adverse events following treatment. Most patients (83.1%) did not receive any adjuvant therapy; 7.9% (n=344) received chemotherapy, 4.9% (n=214) received EBRT, and 4.1% (n=181) received chemoradiation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | Total Cohort (n= 4,381) | Cohort with Change in Employment status (n=950) | Cohort without Change in Employment Status (n=3,431) | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis n (%) | <.001 | |||

| 44 or less | 574 (13.1%) | 119 (12.5%) | 455 (13.3%) | |

| 45 to 49 | 530 (12.1%) | 100 (10.5%) | 430 (12.5%) | |

| 50 to 53 | 721 (16.5%) | 117 (12.3%) | 604 (17.6%) | |

| 54 to 57 | 1135 (25.9%) | 247 (26.0%) | 888 (25.9%) | |

| 58 to 63 | 1421 (32.4%) | 367 (38.7%) | 1054 (30.7%) | |

| Health Insurance Plan Type n (%)** | <0.001 | |||

| HMO | 673 (15.4%) | 130 (13.7%) | 543 (15.9%) | |

| PPO | 2465 (56.3%) | 495 (52.1%) | 1970 (57.4%) | |

| CDHP | 522 (11.9%) | 146 (15.4%) | 376 (10.9%) | |

| Other*** | 721 (16.4%) | 179 (18.8%) | 542 (15.8%) | |

| Region (n, %) | <.001 | |||

| Northeast | 772 (17.6%) | 177 (18.6%) | 595 (17.3%) | |

| North Central | 1052 (24.0%) | 270 (28.4%) | 783 (22.8%) | |

| South | 1720 (39.2%) | 294 (30.9%) | 1426 (41.6%) | |

| West | 831 (19.0%) | 208 (22.0%) | 623 (18.2%) | |

| Unknown | 5 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index n (%) | 0.158 | |||

| 0 | 3685 (84.1%) | 785 (82.6%) | 2900 (84.5%) | |

| 1+ | 696 (15.9%) | 165 (17.4%) | 531 (15.5%) | |

| Metastatic Status (n, %)~ | 0.008 | |||

| Non-metastatic | 3996 (91.2%) | 846 (89.1%) | 3150 (91.8%) | |

| Metastatic | 385 (8.8%) | 104 (10.9%) | 281 (8.2%) | |

| Treatment Group n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| No adjuvant treatment | 3642 (83.1%) | 753 (79.2%) | 2889 (84.2%) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy only | 344 (7.9%) | 91 (9.6%) | 253 (7.4%) | |

| Adjuvant EBRT | 214 (4.9%) | 52 (5.5%) | 162 (4.7%) | |

| Adjuvant chemoradiation | 181 (4.1%) | 54 (5.7%) | 127 (3.7%) | |

| Adverse Events n (%) | 0.807 | |||

| None | 3705 (84.6%) | 797 (83.9%) | 2908 (84.7%) | |

| 1 | 602 (13.7%) | 136 (14.3%) | 466 (13.6%) | |

| 2+ | 74 (1.7%) | 17 (1.8%) | 57 (1.7%) | |

| Year of Diagnosis n (%) | 0.232 | |||

| 2009 | 382 (8.7%) | 89 (9.4%) | 293 (8.5%) | |

| 2010 | 411 (9.4%) | 77 (8.1%) | 334 (9.7%) | |

| 2011 | 456 (10.4%) | 100 (10.5%) | 356 (10.4%) | |

| 2012 | 472 (10.8%) | 92 (9.7%) | 380 (11.1%) | |

| 2013 | 451 (10.3%) | 96 (10.1%) | 355 (10.3%) | |

| 2014 | 438 (9.9%) | 81 (8.5%) | 357 (10.4%) | |

| 2015 | 545 (12.4%) | 124 (13.1%) | 419 (12.2%) | |

| 2016 | 647 (14.8%) | 158 (16.6%) | 489 (14.3%) | |

| 2017 | 581 (13.3%) | 133 (14.0%) | 448 (13.1%) |

EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; HMO, Health maintenance organization; PPO, Preferred provider organization

P-values were derived using the chi-square test

There were 78 patients with unknown insurance plan type.

Other health insurance plans include: Comprehensive, point of service, point of service with capitation, high deductible health plan, and exclusive provider organization

Metastatic status was derived using ICD 9/ICD 10 codes

While most women had a consistent employment status in the 12 months following endometrial cancer diagnosis, 21.7% (n=950) had a change in employment status. Of those, 97.7% (n=928) had a full-time job and 2.3% (n=22) had a part-time job at the time of diagnosis. The most common employment changes were from full-time to other/unknown (78%), early retiree (7.9%), long term disability (5%), and COBRA (4.9%). No patient who previously had a part-time job increased her work hours to full-time. Women who experienced a change in employment were older (P<0.001), more likely to have a metastatic disease (P=0.008), and were more likely to have received adjuvant therapy following surgery (P=0.002). A non-parametric trend test revealed that there was a trend toward an increasing proportion of women who had a change in employment status during the study period (P=0.01).

In univariate analyses, age, health insurance plan type, Charlson comorbidity score and region were significantly associated with a change in employment status. In a cox proportional hazards model controlling for the measured covariates, having a healthcare plan other than an HMO was associated with employment change (HR 1.63 95% CI 1.32–2.02) and residence in the South appeared to have a protective association with employment status change (HR 0.7, 95% CI 0.58–0.84; Table 2). Adjuvant chemoradiation was associated with a 34% increased risk of employment change as compared to surgery alone (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.01–1.78). Receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with employment change, but was not statistically significant (HR 1.22, 95% CI 0.97–1.53). Adjuvant EBRT alone was not independently associated with a change in employment status. In a separate model combining all forms of adjuvant therapy, receipt of any treatment following surgery was associated with change in employment as compared to surgery alone (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02–1.43; Supplemental table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for change in employment

| Characteristics | HR (for change in employment) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| 44 or less | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 45 to 49 | 0.86 | 0.62–1.13 | 0.28 |

| 50 to 53 | 0.74 | 0.57–0.96 | 0.02 |

| 54 to 57 | 1.02 | 0.82–1.27 | 0.84 |

| 58 to 63 | 1.19 | 0.97–1.47 | 0.10 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 1+ | 1.19 | 1.00–1.42 | 0.05 |

| Health Insurance Plan Type | |||

| HMO | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| PPO | 1.15 | 0.94–1.41 | 0.17 |

| OTHER | 1.63 | 1.32–2.02 | <0.0001 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| North Central | 1.18 | 0.98–1.43 | 0.08 |

| South | 0.70 | 0.58–0.84 | 0.0002 |

| West | 1.19 | 0.97–1.47 | 0.09 |

| Unknown | 1.01 | 0.14–7.21 | 0.99 |

| Treatment Group | |||

| Surgery only | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Surgery followed by chemotherapy | 1.22 | 0.97–1.53 | 0.08 |

| Surgery followed by EBRT | 1.07 | 0.80–1.43 | 0.04 |

| Surgery followed by chemoradiation | 1.34 | 1.01–1.78 | 0.65 |

| Adverse Events | |||

| None | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 1 | 1.02 | 0.85–1.23 | 0.80 |

| 2+ | 0.97 | 0.6–1.58 | 0.91 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||

| 2009 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 2010 | 0.80 | 0.59–1.08 | 0.15 |

| 2011 | 0.91 | 0.69–1.22 | 0.54 |

| 2012 | 0.75 | 0.56–1.01 | 0.06 |

| 2013 | 0.87 | 0.65–1.16 | 0.33 |

| 2014 | 0.74 | 0.55–1.00 | 0.05 |

| 2015 | 0.87 | 0.66–1.15 | 0.34 |

| 2016 | 0.94 | 0.72–1.23 | 0.66 |

| 2017 | 0.89 | 0.67–1.18 | 0.41 |

HR, hazard ratio; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; HMO, Health maintenance organization; PPO, Preferred provider organization

Discussion

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States and specific data to inform loss of productivity following diagnosis and treatment are lacking, though this is a major life event. In this study we used a national insurance claims database to estimate the proportion of women that experienced a change in their employment status up to one year after diagnosis. We observed that approximately 22% of women with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer experienced a change in their employment status, and while granular details cannot be determined due to limitations of the database, this warrants further study. In a multivariable model, chemoradiation was associated with a 34% increased risk of employment-status change.

Studies have demonstrated that employment and financial viability are important priorities to cancer patients and their families [9,26]. Our finding that 22% of endometrial cancer patients experienced a change in employment is higher than reported for a breast cancer study utilizing a similar database and methodology where the proportion of employment change among 3233 patients was 7% [16]. The proportion of employment change in our study was also higher than those reported in other breast cancer studies [27,28], but similar to estimates reported in meta-analyses in breast [10,17] and mixed cancer types [29]. Many of the studies included in the meta-analyses, however, did not specifically enroll patients that were employed at the time of diagnosis, and consequently their estimates of unemployment may be higher.

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to assess the proportion of endometrial cancer patients who experienced a change in employment following treatment. Our result is notable as this cohort of women who were working for 12 months prior to their diagnosis (and had employer-sponsored insurance) was designed to represent a group with the highest yield for employment retention. Though stage, race, and other important prognostic variables are not available in the database, we assembled a cohort of patients with newly diagnosed endometrial cancer in whom we would expect long term employment to be undisturbed as most patients will be cured of their disease [30]. In addition, while our study has no control group, this estimate is to be interpreted in the context of the modern American work landscape where adults age 55–64 work more per year and stay in the workforce longer than in previous decades based on a Pew Research Center survey from 2016 [31].

Understanding subgroups of endometrial cancer patents that may be at particular risk of employment change or disruption is critical to developing tailored interventions to maximize functional recovery. Single institution studies [12,32] have examined factors associated with employment status in patients with gynecologic malignancies. A study of 97 patients with early-stage cervical cancer found that radical hysterectomy in combination with chemoradiation was negatively associated with return to work as compared to radical hysterectomy or chemoradiation alone [32]. Moreover, an interview-based study of gynecologic cancer survivors reported that chemotherapy and radiation were associated with work-related physical and cognitive limitations [14]. Similarly, we observed that receipt of chemoradiation independently predicted a change in employment. This is also consistent with studies conducted primarily in patients with breast cancer where receipt of adjuvant therapy was negatively associated with productivity [15–17,33]. Studies have also demonstrated that these negative associations may be long-lasting. In a survey-based study, Jagsi and colleagues found that chemotherapy was associated with unemployment 4 years after breast cancer diagnosis, even in patients that wanted to return to work [34]. While our study does not explain why chemoradiation is associated with employment disruption, it is likely that long-term toxicities such as lingering neuropathy, fatigue, and cognitive impacts contribute to the difficulty in remaining employed after cancer treatment [10,35–38]. Given the lack of granular data such as stage, grade and histology, we cannot rule out chemoradiation, or receipt of any adjuvant therapy as markers of advanced disease in this study. The differential association of therapy options with employment may aid patients and clinicians engaging in shared decision making about treatment options and counseling on survivorship expectations.

Another group that may be vulnerable to employment disruption are endometrial cancer survivors with chronic conditions. We found that the presence of comorbidities demonstrated a non-significant trend toward higher risk of employment change. In a study utilizing data from the Household component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Guy et al. demonstrated that annual lost productivity costs among survivors of cancer with four or more chronic conditions were $9,099 higher than survivors with no chronic conditions [39]. While this study was not specific to our patient population, the implicated chronic comorbidities were primarily of cardiac origin, which is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients [40].

Our findings are subject to a number of limitations. First, we could not adjust for oncologic variables that MarketScan does not contain (histology, grade, stage) and important patient characteristics such as race, socioeconomic status, and marital status. While having insurance plans such as a consumer-driven or high-deductible plans may relate to different occupations or income levels, these are important variables we were unable to adjust for. In addition, employment status was defined using categories reported by employers-sponsored plans to MarketScan. While we assume that changes in these categories reflect major changes in employment, the majority of recorded changes were from full or part-time to “other/unknown”, and it is not entirely clear what this variable signifies. In a study with similar methodology by Hassett and colleagues, there was a lower, but not insignificant proportion (12%) of patients whose employment status changed from full or part-time to “unknown”[16]. In their study, the categories coded by the database were not identical to those in ours and included only “unknown”, not “other/unknown”, which could explain some of the discrepancy. Hassett and colleagues still assumed that a change in status to “unknown” reflected a major change in employment status, as these women were not working in their old jobs and unlikely to start a new job while receiving treatment for cancer.

Moreover, given that MarketScan does not link different employers in the database, we were unable to use this data to capture return to work for a different employer. Furthermore, as we required continuous enrollment in the year following diagnosis, the women who may have disenrolled earlier were not captured, and thus our effect may be an underestimate of the proportion of women who had a change in employment status. Women who left the workforce, but maintained their benefits, via COBRA or other means, however, were included. We were also unable to capture changes occurring beyond 12 months. There is evidence, however, that cancer survivors that return to work will do so within 12 months from diagnosis [41,42].

Another limitation to generalizability is the inability to include women who received insurance benefits as dependents or spouses. It is possible, that these women may have been more likely to discontinue their employment, but the database does not capture employment information for women who were insured as part of a family member’s plan. National survey data are likely more appropriate to assess population-level employment change in women who are self-employed or beneficiaries on a relative’s insurance plan. In addition, interview-based studies found that maintaining coverage was often an incentive to stay in the workforce [26] and in this study all participants had employer-based insurance. While public insurance and lack of insurance have been associated with employment disruption following cancer therapy [18], this database only includes privately-insured patients. A similar analysis in a database including Medicaid-insured patients may reveal that our results underestimate the employment change in a population that does not have employer-sponsored insurance. It is also possible, however, that privately insured patients of higher socioeconomic status may have more social and financial supports in place to allow retirement, which would make our outcome an overestimate of the true impact of endometrial cancer on employment status. Finally, MarketScan primarily receives data from large employers, and patients employed by small firms are underrepresented.

In conclusion, in this study we identified that approximately one in five endometrial cancer survivors could experience employment disruption in the year following cancer diagnosis and that this is potentially mediated by adjuvant therapy and particularly chemoradiation. As this is a major life event, this issue warrants further study to develop a more granular understanding of variables that predict unemployment in patients with endometrial cancer, and how to overcome barriers to re-employment.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Employment disruption after endometrial cancer is an important and understudied life event

One in five endometrial cancer survivors may experience a change in employment

Receipt of chemoradiation may be a driver of this change

Acknowledgements:

Supported by The National Institute of Health’s National Cancer Institute Grants (K08CA234333; JARH), a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 48CA016672), and a National Institutes of Health T32 grant (#5T32 CA101642; RN) The funding sources were not involved in the development of the research hypothesis, study design, data analysis, or manuscript writing.

Conflict of interest statement:

Drs. Nitecki, Fu, Melamed, Lefkowits, Giordano and Rauh-Hain have nothing to disclose. Dr. Smith reports grants from Varian Medical Systems, other from Oncora Medical, outside the submitted work. Dr. Meyer reports grants from National Cancer Institute, during the conduct of the study; other from AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].American Cancer Society. Facts & Figures 2020. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, Ga: 2020, (n.d.). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/endometrial-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed June 14, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dottino JA, Rauh-Hain JA, Financial toxicity: An adverse effect worthy of a black box warning?, Gynecol. Oncol 156 (2020) 263–264. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR, Financial Hardships Experienced by Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review., J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109 (2017). 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].de Boer AGEM, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A, van Dijk FJH, Verbeek JHAM, Cancer survivors and unemployment: a meta-analysis and meta-regression., JAMA. 301 (2009) 753–62. 10.1001/jama.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Employment patterns of long-term cancer survivors., Psychooncology. 11 (n.d.) 188–98. 10.1002/pon.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Park J-H, Park E-C, Park J-H, Kim S-G, Lee S-Y, Job loss and re-employment of cancer patients in Korean employees: a nationwide retrospective cohort study., J. Clin. Oncol 26 (2008) 1302–9. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mehnert A, Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors, Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol 77 (2011) 109–130. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Uterine Cancer, (n.d.). https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html.

- [9].Sharp L, Carsin A-E, Timmons A, Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer, Psychooncology. 22 (2013) 745–755. 10.1002/pon.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid H, Nahar A, Mohd Taib N, Su T, Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review, BMC Public Health. 14 (2014) S8 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL, Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019., CA. Cancer J. Clin 69 (2019) 363–385. 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nakamura K, Masuyama H, Nishida T, Haraga J, Ida N, Saijo M, Haruma T, Kusumoto T, Seki N, Hiramatsu Y, Return to work after cancer treatment of gynecologic cancer in Japan., BMC Cancer. 16 (2016) 558 10.1186/s12885-016-2627-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bradley S, Rose S, Lutgendorf S, Costanzo E, Anderson B, Quality of life and mental health in cervical and endometrial cancer survivors., Gynecol. Oncol 100 (2006) 479–86. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nachreiner NM, Shanley R, Ghebre RG, Cancer and treatment effects on job task performance for gynecological cancer survivors., Work. 46 (2013) 433–8. 10.3233/WOR-131752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dumas A, Vaz Luis I, Bovagnet T, El Mouhebb M, Di Meglio A, Pinto S, Charles C, Dauchy S, Delaloge S, Arveux P, Coutant C, Cottu P, Lesur A, Lerebours F, Tredan O, Vanlemmens L, Levy C, Lemonnier J, Mesleard C, Andre F, Menvielle G, Impact of Breast Cancer Treatment on Employment: Results of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study (CANTO)., J. Clin. Oncol (2019) JCO1901726 10.1200/JCO.19.01726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL, Factors influencing changes in employment among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer., Cancer. 115 (2009) 2775–82. 10.1002/cncr.24301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang L, Hong BY, Kennedy SA, Chang Y, Hong CJ, Craigie S, Kwon HY, Romerosa B, Couban RJ, Reid S, Khan JS, McGillion M, Blinder V, Busse JW, Predictors of Unemployment After Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies., J. Clin. Oncol 36 (2018) 1868–1879. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ekenga CC, Pérez M, Margenthaler JA, Jeffe DB, Early-stage breast cancer and employment participation after 2 years of follow-up: A comparison with age-matched controls., Cancer. 124 (2018) 2026–2035. 10.1002/cncr.31270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].den Bakker CM, Anema JR, Huirne JAF, Twisk J, Bonjer HJ, Schaafsma FG, Predicting return to work among patients with colorectal cancer., Br. J. Surg 107 (2020) 140–148. 10.1002/bjs.11313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Truven Health Analytics: Marketscan, (n.d.). https://www.ibm.com/watson-health/about/truven-health-analytics (accessed June 15, 2020).

- [21].Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Stange KC, Dennis LK, Amini SB, Rimm AA, The Sensitivity of Medicare Claims Data for Case Ascertainment of Six Common Cancers, Med. Care 37 (1999) 436–444. 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Esposito DB, Banerjee G, Yin R, Russo L, Goldstein S, Patsner B, Lanes S, Development and Validation of an Algorithm to Identify Endometrial Adenocarcinoma in US Administrative Claims Data, J. Cancer Epidemiol 2019 (2019) 1–5. 10.1155/2019/1938952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL, Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data., J. Clin. Epidemiol 53 (2000) 1258–67. 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].de Boer SM, Nout RA, Jürgenliemk-Schulz IM, Jobsen JJ, Lutgens LCHW, van der Steen-Banasik EM, Mens JWM, Slot A, Stenfert Kroese MC, Oerlemans S, Putter H, Verhoeven-Adema KW, Nijman HW, Creutzberg CL, Long-Term Impact of Endometrial Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment on Health-Related Quality of Life and Cancer Survivorship: Results From the Randomized PORTEC-2 Trial, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol 93 (2015) 797–809. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Thomas SK, Brooks SE, Daniel Mullins C, Baquet CR, Merchant S, Use of ICD-9 coding as a proxy for stage of disease in lung cancer, Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf 11 (2002) 709–713. 10.1002/pds.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, Chubak J, Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study, J. Cancer Surviv 10 (2016) 1104–1111. 10.1007/s11764-016-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rosenberg SM, Vaz-Luis I, Gong J, Rajagopal PS, Ruddy KJ, Tamimi RM, Schapira L, Come S, Borges V, de Moor JS, Partridge AH, Employment trends in young women following a breast cancer diagnosis, Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 177 (2019) 207–214. 10.1007/s10549-019-05293-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z, Correlates of Return to Work for Breast Cancer Survivors, J. Clin. Oncol 24 (2006) 345–353. 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].de Boer AG, Torp S, Popa A, Horsboel T, Zadnik V, Rottenberg Y, Bardi E, Bultmann U, Sharp L, Long-term work retention after treatment for cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis, J. Cancer Surviv 14 (2020) 135–150. 10.1007/s11764-020-00862-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Neugut AI, Burke WM, Lu Y-S, Lewin SN, Hershman DL, Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive and abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer., Gynecol. Oncol 127 (2012) 11–7. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].The state of American Jobs: How the shifting economic landscape is reshaping work and society and affecting the way people think about the skills and training they need to get ahead, (n.d.). http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/10/ST_2016.10.06_Future-of-Work_FINAL4.pdf (accessed June 14, 2020).

- [32].Nakamura K, Masuyama H, Ida N, Haruma T, Kusumoto T, Seki N, Hiramatsu Y, Radical Hysterectomy Plus Concurrent Chemoradiation/Radiation Therapy Is Negatively Associated With Return to Work in Patients With Cervical Cancer., Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 27 (2017) 117–122. 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jagsi R, Abrahamse PH, Lee KL, Wallner LP, Janz NK, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Morrow M, Kurian AW, Friese CR, Hawley ST, Katz SJ, Treatment decisions and employment of breast cancer patients: Results of a population-based survey, Cancer. 123 (2017) 4791–4799. 10.1002/cncr.30959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, Li Y, Janz NK, Griggs JJ, Bradley C, Graff JJ, Hamilton A, Katz SJ, Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer, Cancer. 120 (2014) 1854–1862. 10.1002/cncr.28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gao H, Xiao M, Bai H, Zhang Z, Sexual Function and Quality of Life Among Patients With Endometrial Cancer After Surgery, Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 27 (2017) 608–612. 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Poort H, Rooij BH, Uno H, Weng S, Ezendam NPM, Poll-Franse L, Wright AA, Patterns and predictors of cancer-related fatigue in ovarian and endometrial cancers: 1-year longitudinal study, Cancer. 126 (2020) 3526–3533. 10.1002/cncr.32927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Soisson S, Ganz PA, Gaffney D, Rowe K, Snyder J, Wan Y, Deshmukh V, Newman M, Fraser A, Smith K, Herget K, Hanson HA, Wu YP, Stanford J, Werner TL, Setiawan VW, Hashibe M, Long-term, adverse genitourinary outcomes among endometrial cancer survivors in a large, population-based cohort study, Gynecol. Oncol 148 (2018) 499–506. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse L, de Vries J, Schep G, Thong MSY, Variation in fatigue among 6011 (long-term) cancer survivors and a normative population: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry, Support. Care Cancer. 23 (2015) 2165–2174. 10.1007/s00520-014-2577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Li R, Richardson LC, Economic Burden of Chronic Conditions Among Survivors of Cancer in the United States, J. Clin. Oncol 35 (2017) 2053–2061. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC, McHale MT, Alvarez EA, Plaxe SC, Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients, Gynecol. Oncol 126 (2012) 176–179. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gordon LG, Lynch BM, Beesley VL, Graves N, McGrath C, O’Rourke P, Webb PM, The Working After Cancer Study (WACS): a population-based study of middle-aged workers diagnosed with colorectal cancer and their return to work experiences, BMC Public Health. 11 (2011) 604 10.1186/1471-2458-11-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Short PF, Vasey JJ, Tunceli K, Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors, Cancer. 103 (2005) 1292–1301. 10.1002/cncr.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.