Abstract

Small molecule inhibitors of proteins represent important medicines and critical chemical tools to investigate the biology of the target proteins. Advances in various -omics technologies have fueled the pace of discovery of disease-relevant proteins. Translating these discoveries into human benefits requires us to develop specific chemicals to inhibit the proteins. However, traditional small molecule inhibitors binding to orthosteric or allosteric sites face significant challenges. These challenges include drug selectivity, therapy resistance as well as drugging undruggable proteins and multi-domain proteins. To address these challenges, PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) has been proposed. PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules containing a binding ligand for a protein of interest and E3 ligase-recruiting ligand that are connected through a chemical linker. Binding of a PROTAC to its target protein will bring a E3 ligase in close proximity to initiate polyubiquitination of the target protein ensuing its proteasome-mediated degradation. Unlike small molecule inhibitors, PROTACs achieve target protein degradation in its entirety in a catalytical fashion. In this review, we analyze recent advances in PROTAC design to discuss how PROTACs can address the challenges facing small molecule inhibitors to potentially deliver next-generation medicines and chemical tools with high selectivity and efficacy. We also offer our perspectives on the future promise and potential limitations facing PROTACs. Investigations to overcome these limitations of PROTACs will further enhance the promise of PROTACs for human benefits.

Keywords: inhibitor, PROTAC, selectivity, cancer, druggability

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The advances in various -omics technologies have significantly enhanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of disease pathologies ranging from cancer, metabolic diseases to neurodegenerative disorders.1 These molecular understandings provide the scientific community a range of molecular targets to be pursued for the discovery of assorted therapeutic modalities. Among the different strategies used in drug discovery and development, small molecules and monoclonal antibodies have shown tremendous successes for the treatment of numerous diseases, which not only validate the -omics discoveries, but also greatly benefit human patients.2-3 These molecules are mainly designed to inhibit or disrupt the function of specific target proteins by binding to their orthosteric or allosteric sites. Each therapeutic modality has its own advantages and limitations.2 Monoclonal antibodies typically exhibit long half-lives and high specificity, but show limited cell permeability, low oral bioavailability and high manufacturing cost. Their uses are limited to cell surface proteins.4 On the other hand, small molecules are endowed with improved balance of drug-like properties including aqueous solubility, cellular permeability and tissue distribution although their half-lives are generally shorter than monoclonal antibodies and more frequent dosing is generally required. Therefore, small molecules targeting both cell surface proteins and intracellular proteins have been developed. They continue to play a dominant role in our modern-day medicines.2 These include drugs targeting G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), protein kinases, proteases, nuclear receptors, histone deacetylases or poly-ADP-ribose polymerases (PARP), most of which possess well-defined binding pockets for small molecules.

In addition to proteins that possess well-characterized small molecule binding pockets, target discovery efforts have also identified a large number of proteins which do not possess well-defined small molecule binding pockets. These proteins have been historically classified as undruggable proteins, which represent >70% of cellular proteins.5-6 It is important to remark that, although some of these proteins can be targeted with small molecules, problems such as toxicity, resistance, off-target effects or selectivity might limit their successful clinical applications. Almost all cellular proteins are subjected to regulation and degradation by one of the two major cellular proteolysis pathways, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the lysosomal degradation pathway.7 The UPS is the major pathway responsible for cellular protein homeostasis, suggesting that hijacking this endogenous protein quality control mechanisms to induce protein degradation may represent a promising approach to target previously considered undruggable targets.8 This strategy may provide a unique opportunity for targeting proteins with non-enzymatic activities such as transcription factors, splicing factors, structural scaffolds and protein aggregates. Most of these proteins perform their primary functions by protein-protein interactions (PPI).9 To achieve this goal, the concept of PROteolysis TArgeting Chimera (PROTAC) was emerged.8 PROTACs are heterobifunctional synthetic molecules able to bind specific proteins and recruit a E3 ubiquitin ligase to promote polyubiquitination of a protein of interest (POI) and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation.10

The proposed mechanism of action of PROTACs, as depicted in Figure 1, is conceptually simple. It entails a cascade of enzymatic reactions that render polyubiquitination of the POI.8, 11 Ubiquitination is a post-translational modification process where ubiquitin is covalently attached to lysine residues through the ε-amino group on the surface of a substrate protein.12 The ubiquitination process comprises the action of three different enzymes: E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme) and E3 (ubiquitin-ligating enzyme).13 PROTACs facilitate the formation of a ternary complex between the POI and the respective E3 ligase by bringing them into close proximity. This ternary complex favors the ubiquitination of the POI resulting in tagging the protein for proteasomal recognition and degradation.14 In contrast to small molecule inhibitors, which work in an occupancy-driven mode of action, PROTACs perform their activity in a catalytic fashion. After the POI is degraded, the PROTAC molecule is still available to initiate a new round of degradation.15

Figure 1.

The proposed mechanism of action of PROTACs. A PROTAC molecule can bring the protein of interest (POI) and a E3 ligase in close proximity resulting in (poly)ubiquitination of POI. The polyubiquitinated POI is then degraded by proteasome while the PROTAC is released and available for another round of POI degradation.

This pioneering idea of PROTAC was first introduced by the Crews and Deshaies laboratories in 2001.16 In this work, the authors described the first PROTAC, PROTAC-1 (1, Figure 2A) as a heterobifunctional molecule composed of the angiogenesis inhibitor ovacilin (OVA), able to covalently bind the methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2), and a 10-amino acid phosphopeptide DRHDSGLDSM from IκBα, a negative regulator of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). 17 This peptide sequence can be recognized by the F-box protein β-transducin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (β-TRCP), which is a subunit of the heterotetrameric Skp1-Cullin-F box (SCF) complex as a E3 ligase.18 As expected, 1 promoted degradation of MetAP2 by recruiting β-TRCP E3 ligase from crude cell extracts in vitro to induce polyubiquitination. These results established proof-of-concept that the UPS system can be hijacked to promote degradation of a target protein in a ubiquitination-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of 1 (A), first all-small-molecule-based PROTAC (2, B). An example of hydrophobic tagging to achieve protein degradation is shown in (C). (D) The number of publications on PROTAC in PubMed (accessed on 7/16/2020).

The peptidic nature of this first-generation PROTACs limited their further development and utility due to their low cell permeability and stability in biological systems. Although the addition of a polycationic polyarginine chain to such a PROTAC structure could potentially overcome the cell permeability problem,19 it was not until the development of all-small-molecule-based PROTACs that this technology got significantly improved by providing more drug-like molecules. The Crews laboratory reported the first all-small-molecule PROTAC (2, Figure 2B) able to successfully induce intracellular degradation of androgen receptor (AR) at 10 μM in human cervical carcinoma cells (HeLa) transiently expressing AR.20 This PROTAC linked a non-steroid selective androgen receptor modulator (SARM) derivative to nutlin to recruit the E3 ubiquitin ligase human homologue of mouse double minute 2 (MDM2).

Besides PROTACs, other heterobifunctional molecules have also been explored to induce protein degradation of proteins using hydrophobic tags instead of E3 ligase recruiting ligands. Using chloroalkane-reactive group (HaloTag) linked to a hydrophobic moiety, the Crews laboratory reported the degradation of a variety of HaloTag fusion proteins, including transmembrane receptors.21 Covalent binding of the hydrophobic tag to the target protein mimics unfolded hydrophobic patches in proteins, which can enlist further protein unfolding and subsequent degradation of the tagged proteins by proteasome. During the last few years, the PROTAC technology has grown dramatically (Figure 2D), which has helped expand the druggable proteome. Although still very limited, several E3 ligases (cereblon (CRBN), von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP), mouse double minute 2 (MDM2), DDB1 and CUL4 associated factors (DCAF15, DCAF16), ring finger protein (RNF114)) have been be employed to trigger ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of an increasing number of disease-relevant proteins.8 Arvinas Pharmaceuticals has reported two orally bioavailable PROTACs able to degrade AR22 and estrogen receptor (ER),23 which are currently in Phase I clinical trials. PROTACs can achieve high efficacy in a low dose due to their catalytic mode of action. A single molecule can mediate the degradation of multiple copies of a given target protein. Thus, PROTACs can be effectively employed at much lower doses than conventional inhibitors, leading to protein degradation in a sub-stoichiometric manner. This mode of action also requires less drug dosing, potentially resulting in less toxicity and side effects.24

Several review articles on PROTACs have been published recently describing the principles and potential advantages of PROTACs.10, 25-30 These reviews are focused on the general advantages and the ability of PROTACs to target a specific protein family (e.g. kinases), the varieties of different E3 ligases that can be exploited or emphasized the promising therapeutic potential for a specific disease. The readers are encouraged to consult these excellent reviews. In this review article, we analyzed specific seminal reports demonstrating how the PROTAC technology can be used as a new promising approach to overcome therapy resistance when inhibitors fail, improve drug selectivity, probe non-enzymatic functions of an enzyme or expand druggability of undruggable proteins. Based on these advances and our experience with drugging challenging targets, we further offer our perspectives on the promises and potential challenges facing PROTACs for the years to come.

2. PROTACs to overcome therapy resistance

The last two decades have seen a dramatic increase in the utility of molecularly targeted therapeutics in the clinic especially in the oncology field.31 However, development of resistance mechanisms in response to the targeted therapies are common and significantly limit their duration of response and clinical utility. While the mechanisms of resistance can be complex, a common mechanism is through mutation or upregulation the targets to be targeted by the small molecule inhibitors. In this case, the cancer cells may still depend on the target for survival and alternative strategies to drug the target may well still be efficacious. Degrading the proteins using PROTAC technology has demonstrated proof-of-principle that this strategy can overcome drug resistance. This change in the mode of action achieved by PROTACs allows resensitization of the cancer cells.

2.1. PROTACs targeting BTK

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is an important validated therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). 32 It is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase and plays a critical role in B-cell development and differentiation, where it is involved in many signaling pathways.33 BTK is an important mediator of key cell surface receptors signaling including B-cell receptor (BCR). Constitutive activation of BCR signaling via BTK is crucial for the survival of leukemic cells and therefore BTK is considered to be one of the main contributors to the progression of B-cell neoplasia such as CLL, the most common form of adult leukemia.34 Despite the dramatic clinical responses induced by irreversible BTK inhibitors, toxicity and resistance still limit their utilization and new treatment options are needed. To date, three BTK inhibitors, ibrutinib (3), acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib have been approved by the US FDA. They are all covalent inhibitors by binding to Cys481 in the kinase domain of BTK. Unfortunately, more than 80% of CLL patients receiving ibrutinib therapy experience disease relapse due to resistance to ibrutinib.35 Cysteine to serine mutation (C481S) at the BTK active site abolishes ibrutinib’s covalent targeting ability. Therefore, the inhibitor can only reversibly bind to the BTK mutant leading to insufficient inhibition and restored tumor growth.36 To overcome this challenge, PROTAC compound 4 (MT-802) (Figure 3A) comprising a reversible ibrutinib-based scaffold linked to pomalidomide through a polyethyleneglycol (PEG) linker was synthesized.37 It has been shown that 4 was able to induce potent degradation of both wild-type and C481S mutant BTK in relapsed primary patient samples. Reversible binding to C481S BTK is sufficient to induce degradation of BTK in ibrutinib-resistant CLL. Moreover, compound 4 has been shown to improve its kinase selectivity profile compared to ibrutinib, which could lead to fewer negative side effects.37

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of BTK inhibitor Ibrutinib (3) and PROTAC 4 (A), BCR-ABL1 inhibitor GNF-5 (6) and PROTAC 5 (B).

2.2. PROTACs targeting BCR-ABL1

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a white blood cell cancer that results from the fusion between the breakpoint cluster region (BCR) and Abelson tyrosine kinase (ABL1) genes to create a new chromosome called Philadelphia chromosome.38 The resulting BCR-ABL1 fusion is constitutively active as a tyrosine kinase. Inhibition of this kinase activity using ATP-competitive tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib has proven to be remarkably effective in preventing cancer progression, inducing remission and prolonging patient survival.39-40 However, issues of extensive drug resistance due to BCR-ABL1 mutation and persistence of residual leukemic stem cells after imatinib treatment are responsible for leukemia progression and relapse, a formidable clinical challenge for CML patients.41

To circumvent the issue of therapy resistance, Burslem et al. reported PROTAC molecule 5 (GMB-475) (Figure 3B) containing the allosteric small molecule ABL1 inhibitor GNF-542 (6) and a VHL-recruiting ligand.43 Compound 5 was able to selectively bind to the allosteric myristate-binding site present in ABL1/BCR-ABL1 to induce proteasome degradation of the fusion protein by recruiting VHL E3 ligase.43 Compound 5 achieved degradation of BCR-ABL1, c-ABL1 and imatinib-resistant T315I BCR-ABL1. In in vitro antiproliferative assays, 5 showed activity in cell lines with TKI-resistant mutants and primary leukemia stem cells from CML patients with sustained inhibition of downstream signaling. In this study, the authors further demonstrated that co-treatment of 5 with traditional TKIs such as imatinib and ponatininb induced promising synergistic effects in CML cells. Combination of 5 and these TKIs could be a promising strategy to address BCR-ABL1-dependent drug resistance, reduce dose, decrease side effects associated with TKIs. In achieving protein degradation, PROTACs like 5 may also allow a deeper understanding of the kinase-independent function of BCR-ABL1 in cell signaling.41

Besides PROTACs targeting BTK and BCR-ABL1, several other examples have also been reported demonstrating that converting small molecules inhibitors to the corresponding degraders can be a potentially successful strategy to overcome drug resistance. These include PROTACs targeting AR and ER in endocrine-resistant prostate and breast cancers.23, 44

3. PROTACs to improve drug selectivity

Selective small molecule inhibitors of target proteins are critical tools in dissecting the biology of target proteins. Often small molecules come with different degree of selectivity and extensive medicinal chemistry or chemical genetics efforts are needed to improve their selectivity and potency. Recently, PROTACs have been shown to be able to convert non-selective inhibitors into more selective protein degraders, which can be a potentially generalizable approach to develop selective small molecule degraders.

3.1. PROTACs to improve selectivity for small molecule kinase inhibitors

Kinases represent one of the major families of drug targets across different disease settings and numerous kinase inhibitors have been approved for various indications. Although highly potent kinase inhibitors can be developed in most cases, the selectivity of the developed kinase inhibitors varies. This is especially true for kinase inhibitors binding to the ATP-binding pocket.45 Accumulating evidence points to PROTACs as a potential approach to solve the selectivity problem in kinase inhibition. As one of the most highlighted examples, the Crews laboratory has demonstrated that converting a promiscuous kinase inhibitor foretinib into its corresponding PROTACs dramatically increased kinase selectivity and degradation specificity.46 As such, foretinib can bind to more than 130 kinases while the PROTACs can only bind to less than half of these kinases and only degrade less than 10 kinases.46 Although the exact mechanisms contributing to the improved selectivity are not fully understood yet, these results provided important initial insights into the degradation specificity achieved with PROTACs. It was found that PROTAC affinity for the target kinases does not necessarily correlate with target kinase degradation efficiency. Instead, the ability to form stable ternary complex between the kinase and the E3 ligase is more predictive of target kinase degradation.46 Productive ternary complex formation between E3 ligase and the target protein mediated by PROTACs can compensate the weak target kinase interaction with the PROTACs. On the other hand, the unfavorable protein-protein interaction between E3 ligase and target kinase can hinder target degradation despite high affinity between the PROTAC and the target kinase. In addition to stable ternary complex formation, other factors such as the availability of optimal lysine residues on the surface of the protein at a proper geometry and orientation to be efficiently ubiquitinated and proteasomal recognition are also necessary (see also below for PROTACs targeting RAS).47 Further investigations to understand the dynamic interplay of these interactions are still needed.

Particular examples of kinase isoform selectivity have been reported for serum and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase (SGK) and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) subfamilies. SGK3 plays a key role in mediating resistance to phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt inhibition in breast cancer cells.48 Different ATP competitive inhibitors against all SGK isoforms with similar affinities have been reported.49-50 However, due to the high homology and structural similarity of the catalytic domain among the different SGK isoforms, attempts to develop isoform-specific inhibitors have been unsuccessful.51 To address this challenge, Tovell et al. developed the potent and highly specific SGK3-PROTAC1 (7, Figure 4), which was derived from Sanofi’s pan-SGK inhibitor 308-R (8).52 In this case, a VHL ligand was linked to 8 through a flexible linker. PROTAC 7 was able to recruit VHL E3 ligase to the proximity of SGK3 to induce proteasome-mediated degradation of SGK3 specifically. At low concentrations, 7 substantially reduced SGK3 levels without affecting SGK1, SGK2, or other off-targets S6K1 in HEK293 cells. Proteomic analysis revealed that degradation of SGK3 was highly selective with a surprising increase in specificity over the parental inhibitor 8. Among the different PROTAC derivatives synthesized, it was found that the SGK isoform inhibition IC50 does not correlate with degradation potency or specificity.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of SGK3-selective degrader 7 pan-SGK inhibitor 8.

CDK4 and CDK6 are two of the 20 CDK family of proteins with key roles in regulation of cell cycle transition, progression and proliferation.53 Several CDK4/6 inhibitors have been approved by FDA for metastatic breast cancer treatment and are under investigation for other cancers such as lymphomas and lung cancers. Developing selective inhibitors to target only one of these kinases using traditional ATP-binding site targeting molecules remains challenging.54-55 However, distinct biological activities have been ascribed for either CDK4 or CDK6 using genetic approaches, suggesting that selectively targeting CDK4 or CDK6 will be instrumental in further understanding the therapeutic value of CDK4/6 inhibitors. The Gray laboratory employed PROTACs to selectively degrade CDK9 based on a chemical scaffold that is a non-selective CDK inhibitor.56 Building on this success, Jiang et al reported several PROTACs by conjugating dual CDK4/6 inhibitors with thalidomide as a CRBN-recruiting moiety (Figure 5).57 The CDK4/6 inhibitors employed included palbociclib (9), ribociclib (10), and abemaciclib (11), none of which could discriminate CDK4 from CDK6. By varying the composition and length of the linker between thalidomide and CDK4/6 inhibitors, either CDK4/6 mono-selective degraders or dual-selective degraders were obtained. For example, BSJ-02-162 (12) was a dual degrader. Changing the linker composition and length in 12 resulted in BSJ-03-123 (13), which is a CDK6 mono-degrader. The PROTACs derived from ribociclib BSJ-01-187 (14) and BSJ-04-132 (15) are both CDK4 mono-degrader. However, changing the aniline to ether-connected thalidomide could eliminate the degradation of zinc fingers IKZF1/3, which are the endogenous targets of molecular glue thalidomide.58 In the case of abemaciclib-derived PROTAC BSJ-01-184 (16), all three targets CD4/6/9 were degraded. This work represents a very interesting example of how variations in the inhibitor, linker length and composition could dramatically modulate the selectivity of the degraders against CDK4 and/or 6 and influence the degradation of other endogenous Ikaros proteins that are usually degraded by thalidomide. As it is the case for other selective degraders derived from non-selective inhibitors, the molecular basis for this selectivity enhancement remains to be determined.

Figure 5.

Examples of several CDK4/6 PROTACs derived from palbocinib (9), ribociclib (10) and abemaciclib (11).

3.2. PROTACs to improve selectivity for small molecule BCL protein inhibitors

Another significant example of improving selectivity using the PROTAC strategy comes from the development of degraders towards B-cell lymphoma (BCL) proteins. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as those from the BCL-2 family (BCL-2, BCL-XL and MCL-1B), is frequently found in the cancer cells of different origins, where these proteins play a key role in cell survival and proliferation.59 Among them, B-cell lymphoma extra-large (BCL-XL) protein is predominantly overexpressed in many solid and liquid tumor cells.59 Although it is an important well-known validated cancer drug target, clinical use of current BCL-XL inhibitors has been limited due to on-target and dose-limiting thrombocytopenia caused by platelet toxicity because platelet cell viability also critically depends on BCL-XL. To date, no effective anti- BCL-XL therapeutics can safely achieve this protein inhibition.60

To reduce the on-target toxicity in platelets, D. Zhou and G. Zheng reported the development of potent and highly selective BCL-XL PROTACs able to minimize the on-target toxicity problems associated with BCL-XL inhibition.61 The structures of inhibitors and PROTACs used in this work are shown in Figure 6. The authors found that VHL and CRBN expression is barely detectable in platelets.62 By taking advantage of this unique difference, it was hypothesized that PROTACs recruiting these E3 ligases would reduce the thrombocytopenia induced by BCL-XL inhibition, allowing to circumvent this on-target toxicity problem. To test this hypothesis, DT2216 (17, Figure 6A) was designed and synthesized by conjugating a dual selective BCL-2 and BCL-XL inhibitor ABT263 (18) to a VHL ligand.61 While 18 is a dual BCL-XL and BCL-2 inhibitor, PROTAC 17 was able to selectively degrade BCL-XL in various tumor cell lines. Proteomic analysis demonstrated that 17 was highly specific for BCL-XL and did not affect expression of any other proteins, including BCL-2. PROTAC 17 induced in vitro tumor cell apoptosis and inhibited growth of several human xenograft tumors, alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. As anticipated, 18 was toxic to platelets. However, 17 did not affect the viability of platelets. Although it lacks oral bioavailability, this PROTAC is metabolically stable and has favorable in vivo pharmacokinetic properties by parenteral dosing.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of BCL-XL inhibitors and selective BCL-XL PROTACs.

Zhang et al.63 further demonstrated that the same strategy can be followed by recruiting another popular E3 ligase CRBN to induce degradation of BCL-XL. In this case, the specific BCL-XL inhibitor A-1155463 (19) was used for PROTAC construction. The resulting PROTAC XZ424 (20, Figure 6B, DC50 = 50 nM) was able to induce potent and selective BCL-XL degradation in human MOLT-4 cells, a T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cell line that is primarily dependent on BCL-XL for survival. Similar to 17, significant improvement of the on-target platelet toxicity was achieved with PROTAC 20.

These results demonstrate that the PROTAC technology can be used to reduce or eliminate side effects due to off- or on-target drug interactions observed with small molecule inhibitors. While the mechanism of rescuing on-target toxicity appears to be related to the unique expression profile of individual E3 ligases to be studied, the mechanism responsible for improved off-target selectivity remains to be determined. In most cases, it is not directly correlated to the binding affinity differences. The improved selectivity achieved through either or both mechanisms can potentially improve the prospects of the PROTACs as potential therapeutics by reducing toxicity profiles.

4. PROTACs to investigate non-enzymatic function of enzymes

4.1. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK)

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a promising target in several types of cancer with multiple inhibitors undergoing clinical trials.64,65 Overexpression and overactivation of FAK can be found in primary and metastatic cancers because it has been implicated in many aspects of tumor growth, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis through both kinase-dependent and independent mechanisms.66 It has been recognized that FAK plays a unique role not only as a kinase but also as a scaffold protein by mediating a plethora of intracellular signaling events.67 Current inhibitors to target FAK only inhibit its catalytic kinase activity while its non-kinase scaffolding functions are left intact, which can be as important as or even more important than its kinase activity in controlling proliferation and dissemination of cancer. As a scaffold protein, FAK provides a platform for different signaling proteins, including oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK). These interactions can initiate or enhance cancer-promoting signals independent of FAK’s kinase activity. The proteins physically interact with the other domains in FAK to orchestrate a large signaling complex interactome.68

The ability of PROTACs to degrade a specific protein offers a strategy to eliminate the protein in its entirety to address the issues arising from inhibiting only one function of a given protein with multiple functions. The Crews laboratory recently reported a highly potent and selective degrader for FAK kinase as shown in Figure 7A.69 A simplified version of defactinib (21), the most advanced FAK inhibitor in clinical development, was selected as a FAK-binding ligand and linked to both VHL- and CRBN-recruiting moieties. All the reported PROTACs were able to inhibit FAK kinase activity at low nanomolar concentrations with IC50 ranging from 4.7 to 14.5 nM. Among them, PROTAC-3 (22) showed the best results with a highly efficient FAK degradation capability. Compared with 21, PROTAC 22 displayed better selectivity and significantly limited the ability of human triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells to migrate and invade, highlighting the importance of FAK scaffolding function in these cancer cell processes. It is important to note that 22 was about ~2-fold less potent in inhibiting FAK’s kinase activity than 21 itself. This work represents the first example of how the PROTAC technology can allow targeting the FAK kinase-independent functions, which cannot be addressed by traditional small molecule kinase inhibitors.

Figure 7.

Chemical structures of FAK (A) and EGFR (B) kinase inhibitors and their corresponding PROTACs.

4.2. Epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR)

RTKs such as epithelia growth factor receptor (EGFR, ErbB1/HER1)), HER2, and c-Met are single transmembrane-spanning proteins with well-defined roles in many human cancers.70 Overexpression and/or overactivation of these proteins is associated with cell proliferation, cell survival and poor prognosis in cancer patients.70-71 The Crews laboratory demonstrated that RTKs, despite their restricted cellular localization, are viable substrates for induced protein degradation.72 As an RTK, EGFR not only functions as a tyrosine kinase, its other domains can also function as a cognate binding partner for other RTKs even when its kinase activity is inhibited. This docking platform provides a mechanism for crossactivation of other RTKs to induce kinome rewiring, effectively contributing to resistance to EGFR-based inhibitor therapy.73-74 To address the significance of the scaffolding function of EGFR, the Crews group created a PROTAC based on EGFR inhibitor lapatinib (23) by conjugating with a VHL ligand (lapatinib-PROTAC-1, 24) (Figure 7B).72 To specifically differentiate the degradation from its inhibition effect, a diasteromeric control epi-lapatinib-PROTAC-1 (25, Figure 7B) was also prepared. In a side-by-side comparison, 24 and 25 showed similar EGFR inhibition potency. However, 24 permitted more sustained inhibition of downstream signaling activation and inhibited kinome rewiring activity in the EGFR-dependent cancer cell lines. These results lent further support for the scaffolding function of EGFR.

5. PROTACs to expand druggability

The development of small molecules able to target the undruggable proteome could be one of the greatest advantages of PROTACs. The ability of this type of molecules to highjack the endogenous protein quality control machinery suggests a promising opportunity to degrade challenging targets such as transcription factors, protein aggregates, structural proteins, and other proteins without obvious enzymatic activities. The potential of this strategy is further enhanced by the recent developments in fragment-based drug discovery and covalent fragment discovery, where fragments of lower affinity can often be identified for these challenging targets.75-78 Whereas these fragments are insufficient as inhibitors alone, elaborations of these fragments into PROTACs have the potential to degrade the protein to achieve either therapeutic or biological utilities. This would greatly expand the current druggable proteome.

5.1. PROTACs targeting transcription factors

Transcription factors are proteins to control the transcription of genes into mRNA for protein synthesis. They are central regulators of cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation and death. With the exception of nuclear receptors (e.g. AR, ER and glucocorticoid receptor (GR)) which naturally contain a binding pocket for endogenous hormones, most of the transcription factors have been historically perceived as challenging targets because of their lack of well-defined druggable active sites for small molecules.79-81 Thus, inducing protein degradation represents a potential approach to target this class of proteins. A few examples in the literature have demonstrated that induced proteasomal degradation of transcription factors by small molecules can be a strategy to successfully approach the druggability of this protein class.

5.1.1. Zinc fingers (ZF)

Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) such as thalidomide have seen a renewed interest as effective therapies for proliferative hematological malignancies.82 This renewed interest is due to the discovery that they are able to induce proteasomal degradation of zinc finger (ZF) transcription factor Ikaros (IKZF1) and Aiolos (IKZF3),58, 83 which are essential transcription factors in multiple myeloma. IKZF1 and IKZF3 are among the ~700 Cys2-His2 (C2H2) ZF proteins that comprise the largest group of transcription factors encoded by the human genome.79 Although these IMiDs are not PROTACs per se, these drugs are considered to act as simple PROTACs or molecular glues since they perform their activity through a similar mechanism of action by promoting rapid ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of neo-substrates by recruiting a C2H2 ZF domain to CRBN. Sievers et al.84 found that thalidomide analogs are able to promote proteasomal degradation of a large number of C2H2 ZF-containing proteins and demonstrated that they can achieve selective ZF degradation through structural modification of IMiDs. Thus, IMiDs derivatization might open an interesting approach for therapies based on targeting selective ZF degradation.

5.1.2. Signal transduction and activator of transcription factor (STAT)

The Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling pathway is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases such as type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and cancer.85 STAT proteins comprise a family of seven proteins which share a highly structurally homologous Src-homology (SH2) domain. Among them, STAT3 is constitutively active in several human cancers, where they regulate the transcription of genes implicated in tumor cell proliferation, survival and differentiation. STAT3 has been considered a promising therapeutic target for numerous cancers, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.86 In the canonical pathway, cytosolic STAT3 is dimerized through their SH2 domain after being phosphorylated at Tyr705 (Y705) by JAK. The thus-formed active dimer translocates into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of target genes. Design of highly selective STAT3 inhibitors have been difficult. Although several STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors have been reported,87-88 targeting STAT3 with cell-permeable small molecule inhibitors have not been very successful. On one hand, some peptidomimetics have been shown to have high affinity for STAT3. But they suffer from limited cell-permeability. On the other hand, non-peptidic STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors have also been reported, but they are usually weak-affinity binders.89 Furthermore, the discovery that non-phosphorylated STAT3 monomer can be transcriptionally active90 suggests that targeting SH2 dimerization alone might be insufficient to inhibit STAT3’s transcription activity.

The Wang laboratory91-92 has recently reported SD-36 (26, Figure 8) as the first PROTAC able to target and degrade STAT3 in a highly selective and potent manner. This compound combines SI-109 (27), a high affinity STAT3 SH2 domain binding ligand, with lenalidomide to render a bifunctional molecule able to induces potent in vitro and in vivo degradation of STAT3. It showed extremely high selectivity towards STAT3 over other STAT members. This work represents a successful example of how PROTACs can be used to promote effective and selective degradation of challenging target such as transcription factors.

Figure 8.

Chemical structures of STAT3 PROTAC 26 and STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitor 27.

5.2. PROTACs targeting protein-protein interactions

Targeting or disrupting protein-protein interactions remains a difficult challenge by traditional pharmacological approaches. The interaction interfaces are in many cases large and flat, which are refractory for small molecule recognition and binding, posing difficulty in developing small molecules with high affinity.93 Targeted protein degradation is a viable option to overcome these limitations. PROTACs do not require a functional inhibitor and low affinity binders can be converted into efficient degraders.94 Thus, this emerging technology has an enormous potential to approach these difficult targets. Several examples of PROTACs to induce degradation of proteins involved in protein-protein interactions are analyzed below, where conventional small molecule inhibitors have until now failed.

5.2.1. Tau protein aggregates

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein predominantly expressed in neurons. It has an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases known as Tauopathies.95 In these diseases, hyper-phosphorylated Tau protein collapses into aggregates called neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) leading to neuronal cell toxicity and death. The aberrant intracellular Tau protein aggregation in the brain is a hallmark of AD.96 Increased level of Tau has been found in AD patients where high level of this protein can promote its aggregation and also mediate the toxicity of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ). Recent studies have shown that reduction of Tau levels represents a promising strategy for treating AD.97 Modulation of Tau, like other disease-related proteins without enzymatic function, represents a challenging task for small molecules. Thus, traditional small molecules are not effective to modulate Tau. Instead of directly inhibiting this type of proteins, inducing degradation by PROTACs through harnessing the cellular protein quality-control system has emerged as a potential approach for regulating protein levels and targeting non-enzymatic proteins inside the cells. Therefore, this can represent a novel therapeutic strategy for the treatment of AD and a way to selectively remove these protein aggregates.

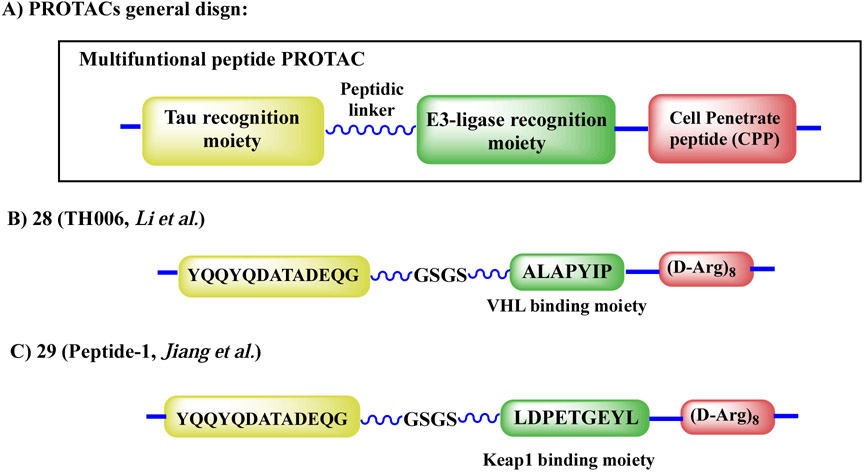

In the first demonstration, Chu et al.98 reported a series of molecules able to induce endogenous Tau degradation by peptide-based PROTACs. The designed molecules, as shown in Figure 9A, comprised four parts: a) a fragment that can selectively recognize Tau; b) a peptide-based substrate able to bind to a E3 ligase; c) a short peptidic linker (GSGS or GGSGG) to increase flexibility; and d) a cell-penetrating peptide poly-arginine (D-Arg)8 to enhance cell permeability. Two peptides derived from either α-tubulin ((430–441): KDYEEVGVDSVE) or β-tubulin (422–434): YQQYQDATADEQG) were used to recognize Tau. Both a phosphor-peptide (DRHDpSpGLDpSM) derived from IκBα to recruit β-TRCP E3 ligase and a VHL-recruiting peptide (ALAPYIP) were investigated as E3 ligase recruiting moieties. Among these peptide-based PROTACs, TH006 (28, Figure 9B) was shown to be cell-permeable and could bind Tau (Kd = 0.3944 ± 0.1589 μM). Furthermore, it increased Tau polyubiquitination and efficiently induced intracellular Tau degradation. In this work, the authors further demonstrated that 28 reduced the neurotoxicity induced by Aβ and could regulate the Tau level in the brain of an AD mouse model. More recently, Lu et al.99 designed and reported another peptide-based PROTAC Peptide-1 (29, Figure 9C) able to hijack Keap1-Cul3 ubiquitin E3 ligase for ubiquitination and proteasome degradation of intracellular Tau protein aggregates. According to flow cytometry and Western blotting assay analyses, peptide 29 could downregulate intracellular Tau level in a time- and concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 9.

General structures of peptide-based PROTACs for Tau degradation.

The peptide-based PROTACs for Tau degradation demonstrated proof-of-principle that such a strategy could regulate the levels of Tau protein and avoid the formation of toxic aggregates. However, the peptidic nature of these PROTACs limit their potential clinical applications. To address this challenge, the Gray and Haggarty laboratories100 recently reported the first all-small-molecule-based PROTAC for Tau degradation with promising results for the treatment of frontotemporal dementia (FTD). As shown in Figure 10, the authors took advantage of the clinically used Tau positron emission tomography (PET) probe 18F-T807 (30) and designed QC-01-175 (31) as a heterobifunctional degrader to trigger Tau ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation by engaging CRBN with pomalidomide. Compound 31 targeted multiple forms of Tau for degradation in FTD neuronal cell models and was able to discriminate between healthy and disease-associated Tau in affected regions of the mouse brain. Whole-cell proteomic analysis showed that 31 had an improved selectivity over the original 30. These off-targets include monoamine oxidase A and B, which were not degraded by 31, a salient feature reminiscent of other PROTACs with improved selectivity.

Figure 10.

Chemical structures of PET probe 30 and PROTAC 31 for Tau.

5.2.2. RAS Proteins

The RAS proteins are in the family of small GTPase proteins that regulate diverse biological pathways including cell growth, differentiation, proliferation and survival.101 This family comprises three RAS isoforms (H, N and K). Among them, KRAS is the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancers, including pancreatic, colorectal and lung cancer.102 However, the RAS protein has a high binding affinity for the endogenous substrate GTP. And the lack of other well-defined binding sites available makes this protein an especially challenging target.103 Despite these difficulties, progress has been made by targeting specific KRAS mutants using covalent inhibitors. For example, Wellspring, Amgen and Mirati Therapeutics announced promising clinical data in the evaluation of ARS-3248 (based on scaffold ARS-1620 (32)), AMG-510 and MRTX-849 (35), respectively, by targeting KRASG12C.

Small molecule-based PROTACs might be a potentially complementary strategy for modulating oncogenic KRAS. To test this hypothesis, the Gray laboratory104 recently reported the first attempt towards KRASG12C degradation. In their work, the authors designed a group of PROTACs by conjugating the previously reported KRASG12C-directed covalent quinazoline scaffold 32 with CRBN-recruiting thalidomide derivatives (Figure 11A). The authors reported synthesis and evaluation of a library of >100 potential degraders by diversifying the linker length and composition. From this library, compound 33 (XY-4-88) emerged as the best-performing degrader. It had good cell permeability, successfully recruited CRBN and KRASG12C together to form a ternary complex in vitro. Furthermore, compound 33 could induce degradation of a surrogate substrate GFP-KRASG12C in a reporter cell line through a UPS-dependent mechanism. However, when 33 was tested in two KRASG12C-bearing cell lines, MiaPaCa2 (pancreatic) and H358 (lung), no significant degradation of endogenous KRAS was observed. Although compound 33 was able to form ternary complex between CRBN/KRASG12C, poly-ubiquitination of the target protein was only observed on GFP-KRASG12C. These data suggest that appropriate position of lysines and/or orientation of PRTOACs towards target substrate are critical for inducing protein degradation. While PROTAC 33 was not able to induce endogenous KRAS degradation, the Crews laboratory105 has recently reported LC-2 (34, Figure 11B) as the first-in-class PROTAC capable of rapid and sustained endogenous KRASG12C degradation by recruiting E3 ligase VHL in both homozygous and heterozygous cell lines. In this work, the authors used MRTX849 (35) as a KRASG12C binding ligand and tested 34 in multiples KRASG12C cancer cell lines (NCI-H2030, MIA-PaCa2, SW-1573, NCI-H23, NCI-H358) with DC50 values between 0.25 and 0.76 μM.

Figure 11.

Chemical structures of the KRASG12C inhibitors and PROTACs.

6. Perspectives and Conclusions

As the examples illustrated above, the PROTAC technology has been blooming in the last few years demonstrating successful results in inducing degradation of numerous proteins and addressing some of the challenges associated with traditional small molecule inhibitors. These challenges include selectivity, side effect, toxicity, resistance, targeting multi-functional proteins, druggability against otherwise undruggable targets.106 It represents not only a promising approach to deliver next-generation therapeutics, but also offers new chemical tools for biological interrogation. With PROTACs, a new tool can be added to our arsenal of removing a target protein in its entirety, which has been only achieved by genetic techniques such CRISPR/CAS9 or RNAi. PROTACs can allow better control of a specific target in a time- and concentration-dependent manner.

Besides classical PROTACs, variations of this technology have enabled different controls of different target proteins. The Carreira laboratory recently reported the first photoswitchable PROTAC.107 These molecules or photoPROTACs include an ortho-F4-azobenzene group as part of the linker structure, which allows reversible control of the distance between the ligands and E3 ligase recruiter. This gives an optical control of degradation of the target protein. More recently, the Staben group reported the first example of a phosphatase recruiting chimeras (PhoRCs) to achieve dephosphorylation of two oncogenic kinases, AKT and EGFR.108 With a similar idea, these molecules are able to recruit protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) to promote dephosphorylation of the protein of interest.108 These molecules represent a new modality of molecular control of post-translational modifications.

For the design of PROTACs, it is critical that appropriate binding ligands for target proteins are available. Different approaches have emerged to develop ligands for a diverse range of proteins. We recently reported the discovery of LBL1 as the first small molecule to binding nuclear lamins using a chemical genetics approach.109-110 Mutations of lamin A (LMNA) cause a wide spectrum of diseases called laminopathies.111 We speculate that PROTACs derived from LBL1 might be potentially useful for treating laminopathies. Bead-based binding screening assays against combinatorial libraries have been shown to be effective in identifying ligands for different target proteins.112-113 Furthermore, the recent implementation of DNA-encoded libraries (DEL) represents another exciting approach to discover ligands for target proteins.114 The DEL technology is able to rapidly screen hundreds of thousands to billions of compounds through an affinity-based assay. In DEL, a unique DNA barcode is attached to each compound allowing for easy deconvolution through next-generation sequencing. As we have discussed above, PROTACs do not need functional inhibitors to promote protein degradation. Stability and efficiency of the ternary complex formation seem to be the major factors driving PROTAC activity instead of the ligand binding affinity.

It is important to keep in mind that PROTACs also face several challenges that still deserve further investigations. Different E3 ligases have shown different activity and selectivity for protein degradation. The human genome encodes more than 600 E3 ligases115 and so far only a handful has been used in the design of functional PROTACs. By taking advantage of the distinct localization and expression differences among the E3 ligases,8, 61, 116 it is possible to achieve specificity in subcellular or cellular degradation of specific proteins. While it has not been demonstrated yet, the different protein-protein interactions at different contexts may further enlist unique selectivity of protein degradation at specific context, a feature not possible with genetic ablation of proteins. For example, transcription regulators at chromatin-bound state versus non-chromatin bound state engage different protein interaction partners. It is envisioned that certain protein binding partners will reposition surface-exposed lysines on substrate proteins to be degraded. Therefore, PROTACs can potentially degrade one pool of transcription regulators using this unique difference. Composition and physical properties of the linker seems to have an important influence over the PROTAC activity. Due to their unique mechanism of action, traditional rules like Lipinski’s rule might be not suitable to make a go/no go decision in a drug discovery project. To address the issue of relatively large molecular weight of PROTACs,117 the Heightman group reported the use of in-cell click chemistry to generate functional PROTACs from smaller precursors. This process is called in-cell click-formed proteolysis targeting chimeras (CLIPTAC).118 While the authors demonstrated success in degrading bromodomains, the generality of this approach remains to be seen because it has been realized that the linker composition has a huge influence on the activity of PRTOACs and only limited functional groups are amenable for in-cell click reactions.

Although we have summarized above that efficient degradation of many endogenous targets including KRAS was achieved, some proteins have been shown to be refractory to PROTAC-mediated degradation. For example, many natural and synthetic compounds are known to bind tubulins. Efforts to design PROTACs based on these small molecules to induce tubulin degradation have not been successful.119 In this case, both synthetic and natural products-derived tubulin binders were utilized to conjugate with CRBN-recruiting ligands. However, none of the reported PRTOACs was able to induce degradation of tublin. This lack of degradation is not due to inability of tubulin degradation by the UPS system because covalent tubulin binders T007-1120 and T138067121 were shown to be able to induce degradation. As illustrated above, some PROTACs are able to bind certain targets while only a small fraction of those targets is degraded. While this increases the selectivity of PROTACs compared to small molecule inhibitors, it also raises an issue that some targets are harder to be degraded by PROTACs, a potential limitation of the PROTACs strategy. It is possible that exploration of different substrate-binding ligands in combination with different E3 ligase recruiters may induce degradation of a unique subset of substrates. Further mechanistic understanding of these issues will help our rationale in selecting appropriate pairs to achieve desired target protein degradation.

Highlights:

PROTACs are catalytic protein degraders.

Advantages and limitations of PROTACs are discussed.

PROTACs to target undruggable proteins.

Examples of PROTACs overcoming limitations of parental inhibitors are described.

Challenges and opportunities for PROTACs are discussed.

Acknowledgements.

We thank the financial supports provided by National Institutes of Health and Oregon Health & Science University. XX is supported by NIH R01GM122820, R01CA211866, R21CA220061 and R21EB028425. We thank the Xiao lab members for insightful discussions on PROTACs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Karczewski KJ; Snyder MP Integrative Omics for Health and Disease. Nature reviews. Genetics 2018, 19, 299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Imai K; Takaoka A Comparing Antibody and Small-Molecule Therapies for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 714–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Huang A; Garraway LA; Ashworth A; Weber B Synthetic Lethality as an Engine for Cancer Drug Target Discovery. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2020, 19, 23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Nelson AL; Dhimolea E; Reichert JM Development Trends for Human Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010, 9, 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Overington JP; Al-Lazikani B; Hopkins AL How Many Drug Targets Are There? Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2006, 5, 993–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Oprea TI; Bologa CG; Brunak S; Campbell A; Gan GN; Gaulton A; Gomez SM; Guha R; Hersey A; Holmes J; Jadhav A; Jensen LJ; Johnson GL; Karlson A; Leach AR; Ma'ayan A; Malovannaya A; Mani S; Mathias SL; McManus MT; Meehan TF; von Mering C; Muthas D; Nguyen DT; Overington JP; Papadatos G; Qin J; Reich C; Roth BL; Schürer SC; Simeonov A; Sklar LA; Southall N; Tomita S; Tudose I; Ursu O; Vidovic D; Waller A; Westergaard D; Yang JJ; Zahoránszky-Köhalmi G Unexplored Therapeutic Opportunities in the Human Genome. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2018, 17, 317–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ciechanover A Proteolysis: From the Lysosome to Ubiquitin and the Proteasome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2005, 6, 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Schapira M; Calabrese MF; Bullock AN; Crews CM Targeted Protein Degradation: Expanding the Toolbox. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18, 949–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Verdine GL; Walensky LD The Challenge of Drugging Undruggable Targets in Cancer: Lessons Learned from Targeting Bcl-2 Family Members. Clin. Cancer Res 2007, 13, 7264–7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Konstantinidou M; Li J; Zhang B; Wang Z; Shaabani S; Ter Brake F; Essa K; Dömling A Protacs- a Game-Changing Technology. Expert opinion on drug discovery 2019, 14, 1255–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Burslem GM; Crews CM Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras as Therapeutics and Tools for Biological Discovery. Cell 2020, 181, 102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Komander D; Rape M The Ubiquitin Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2012, 81, 203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Finley D; Chau V Ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol 1991, 7, 25–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Pettersson M; Crews CM Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (Protacs) - Past, Present and Future. Drug discovery today. Technologies 2019, 31, 15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bondeson DP; Mares A; Smith IE; Ko E; Campos S; Miah AH; Mulholland KE; Routly N; Buckley DL; Gustafson JL; Zinn N; Grandi P; Shimamura S; Bergamini G; Faelth-Savitski M; Bantscheff M; Cox C; Gordon DA; Willard RR; Flanagan JJ; Casillas LN; Votta BJ; den Besten W; Famm K; Kruidenier L; Carter PS; Harling JD; Churcher I; Crews CM Catalytic in Vivo Protein Knockdown by Small-Molecule Protacs. Nat Chem Biol 2015, 11, 611–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Sakamoto KM; Kim KB; Kumagai A; Mercurio F; Crews CM; Deshaies RJ Protacs: Chimeric Molecules That Target Proteins to the Skp1–Cullin–F Box Complex for Ubiquitination and Degradation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, 8554–8559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yaron A; Hatzubai A; Davis M; Lavon I; Amit S; Manning AM; Andersen JS; Mann M; Mercurio F; Ben-Neriah Y Identification of the Receptor Component of the Ikappabalpha-Ubiquitin Ligase. Nature 1998, 396, 590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Deshaies RJ Scf and Cullin/Ring H2-Based Ubiquitin Ligases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 1999, 15, 435–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Guidotti G; Brambilla L; Rossi D Cell-Penetrating Peptides: From Basic Research to Clinics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 2017, 38, 406–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schneekloth AR; Pucheault M; Tae HS; Crews CM Targeted Intracellular Protein Degradation Induced by a Small Molecule: En Route to Chemical Proteomics. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 5904–5908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tae HS; Sundberg TB; Neklesa TK; Noblin DJ; Gustafson JL; Roth AG; Raina K; Crews CM Identification of Hydrophobic Tags for the Degradation of Stabilized Proteins. Chembiochem 2012, 13, 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Neklesa T; Snyder LB; Willard RR; Vitale N; Pizzano J; Gordon DA; Bookbinder M; Macaluso J; Dong H; Ferraro C; Wang G; Wang J; Crews CM; Houston J; Crew AP; Taylor I Arv-110: An Oral Androgen Receptor Protac Degrader for Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol 2019, 37, 259–259. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Flanagan J; Qian Y; Gough S; Andreoli M; Bookbinder M; Cadelina G; Bradley J; Rousseau E; Willard R; Pizzano J; Crews C; Crew A; Taylor I; Houston J Abstract P5-04-18: Arv-471, an Oral Estrogen Receptor Protac Degrader for Breast Cancer. Cancer Research 2019, 79, P5-04-18-P05-04-18. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Fisher SL; Phillips AJ Targeted Protein Degradation and the Enzymology of Degraders. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 44, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhou X; Dong R; Zhang J-Y; Zheng X; Sun L-P Protac: A Promising Technology for Cancer Treatment. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2020, 203, 112539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Nalawansha DA; Crews CM Protacs: An Emerging Therapeutic Modality in Precision Medicine. Cell chemical biology 2020, 27, 998–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Khan S; He Y; Zhang X; Yuan Y; Pu S; Kong Q; Zheng G; Zhou D Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (Protacs) as Emerging Anticancer Therapeutics. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4909–4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Chamberlain PP; Hamann LG Development of Targeted Protein Degradation Therapeutics. Nature Chemical Biology 2019, 15, 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hu B; Zhou Y; Sun D; Yang Y; Liu Y; Li X; Li H; Chen L Protacs: New Method to Degrade Transcription Regulating Proteins. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2020, 207, 112698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Gao H; Sun X; Rao Y Protac Technology: Opportunities and Challenges. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2020, 11, 237–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Chae YK; Pan AP; Davis AA; Patel SP; Carneiro BA; Kurzrock R; Giles FJ Path toward Precision Oncology: Review of Targeted Therapy Studies and Tools to Aid in Defining "Actionability" of a Molecular Lesion and Patient Management Support. Mol. Cancer Ther 2017, 16, 2645–2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Woyach JA; Bojnik E; Ruppert AS; Stefanovski MR; Goettl VM; Smucker KA; Smith LL; Dubovsky JA; Towns WH; MacMurray J; Harrington BK; Davis ME; Gobessi S; Laurenti L; Chang BY; Buggy JJ; Efremov DG; Byrd JC; Johnson AJ Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase (Btk) Function Is Important to the Development and Expansion of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (Cll). Blood 2014, 123, 1207–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Mohamed AJ; Yu L; Bäckesjö C-M; Vargas L; Faryal R; Aints A; Christensson B; Berglöf A; Vihinen M; Nore BF; Edvard Smith CI Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (Btk): Function, Regulation, and Transformation with Special Emphasis on the Ph Domain. Immunol. Rev 2009, 228, 58–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wang Q; Pechersky Y; Sagawa S; Pan AC; Shaw DE Structural Mechanism for Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Activation at the Cell Membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 9390–9399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Woyach JA How I Manage Ibrutinib-Refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2017, 129, 1270–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Woyach JA; Furman RR; Liu TM; Ozer HG; Zapatka M; Ruppert AS; Xue L; Li DH; Steggerda SM; Versele M; Dave SS; Zhang J; Yilmaz AS; Jaglowski SM; Blum KA; Lozanski A; Lozanski G; James DF; Barrientos JC; Lichter P; Stilgenbauer S; Buggy JJ; Chang BY; Johnson AJ; Byrd JC Resistance Mechanisms for the Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib. N. Engl. J. Med 2014, 370, 2286–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Buhimschi AD; Armstrong HA; Toure M; Jaime-Figueroa S; Chen TL; Lehman AM; Woyach JA; Johnson AJ; Byrd JC; Crews CM Targeting the C481s Ibrutinib-Resistance Mutation in Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase Using Protac-Mediated Degradation. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3564–3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Rowley JD Letter: A New Consistent Chromosomal Abnormality in Chronic Myelogenous Leukaemia Identified by Quinacrine Fluorescence and Giemsa Staining. Nature 1973, 243, 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Druker BJ; Guilhot F; O'Brien SG; Gathmann I; Kantarjian H; Gattermann N; Deininger MWN; Silver RT; Goldman JM; Stone RM; Cervantes F; Hochhaus A; Powell BL; Gabrilove JL; Rousselot P; Reiffers J; Cornelissen JJ; Hughes T; Agis H; Fischer T; Verhoef G; Shepherd J; Saglio G; Gratwohl A; Nielsen JL; Radich JP; Simonsson B; Taylor K; Baccarani M; So C; Letvak L; Larson RA Five-Year Follow-up of Patients Receiving Imatinib for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 2006, 355, 2408–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hochhaus A; Larson RA; Guilhot F; Radich JP; Branford S; Hughes TP; Baccarani M; Deininger MW; Cervantes F; Fujihara S; Ortmann CE; Menssen HD; Kantarjian H; O'Brien SG; Druker BJ Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med 2017, 376, 917–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ichim CV Kinase-Independent Mechanisms of Resistance of Leukemia Stem Cells to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Stem Cells Transl Med 2014, 3, 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Zhang J; Adrian FJ; Jahnke W; Cowan-Jacob SW; Li AG; Iacob RE; Sim T; Powers J; Dierks C; Sun F; Guo GR; Ding Q; Okram B; Choi Y; Wojciechowski A; Deng X; Liu G; Fendrich G; Strauss A; Vajpai N; Grzesiek S; Tuntland T; Liu Y; Bursulaya B; Azam M; Manley PW; Engen JR; Daley GQ; Warmuth M; Gray NS Targeting Bcr-Abl by Combining Allosteric with Atp-Binding-Site Inhibitors. Nature 2010, 463, 501–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Burslem GM; Schultz AR; Bondeson DP; Eide CA; Savage Stevens SL; Druker BJ; Crews CM Targeting Bcr-Abl1 in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia by Protac-Mediated Targeted Protein Degradation. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4744–4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Salami J; Alabi S; Willard RR; Vitale NJ; Wang J; Dong H; Jin M; McDonnell DP; Crew AP; Neklesa TK; Crews CM Androgen Receptor Degradation by the Proteolysis-Targeting Chimera Arcc-4 Outperforms Enzalutamide in Cellular Models of Prostate Cancer Drug Resistance. Communications Biology 2018, 1, 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Ferguson FM; Gray NS Kinase Inhibitors: The Road Ahead. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2018, 17, 353–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bondeson DP; Smith BE; Burslem GM; Buhimschi AD; Hines J; Jaime-Figueroa S; Wang J; Hamman BD; Ishchenko A; Crews CM Lessons in Protac Design from Selective Degradation with a Promiscuous Warhead. Cell Chem. Biol 2018, 25, 78–87.e75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Smith BE; Wang SL; Jaime-Figueroa S; Harbin A; Wang J; Hamman BD; Crews CM Differential Protac Substrate Specificity Dictated by Orientation of Recruited E3 Ligase. Nature communications 2019, 10, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Bruhn MA; Pearson RB; Hannan RD; Sheppard KE Second Akt: The Rise of Sgk in Cancer Signalling. Growth Factors 2010, 28, 394–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Halland N; Schmidt F; Weiss T; Saas J; Li Z; Czech J; Dreyer M; Hofmeister A; Mertsch K; Dietz U; Strübing C; Nazare M Discovery of N-[4-(1h-Pyrazolo[3,4-B]Pyrazin-6-Yl)-Phenyl]-Sulfonamides as Highly Active and Selective Sgk1 Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 6, 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Sherk AB; Frigo DE; Schnackenberg CG; Bray JD; Laping NJ; Trizna W; Hammond M; Patterson JR; Thompson SK; Kazmin D; Norris JD; McDonnell DP Development of a Small-Molecule Serum- and Glucocorticoid-Regulated Kinase-1 Antagonist and Its Evaluation as a Prostate Cancer Therapeutic. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 7475–7483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gong GQ; Wang K; Dai XC; Zhou Y; Basnet R; Chen Y; Yang DH; Lee WJ; Buchanan CM; Flanagan JU; Shepherd PR; Chen Y; Wang MW Identification, Structure Modification, and Characterization of Potential Small-Molecule Sgk3 Inhibitors with Novel Scaffolds. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2018, 39, 1902–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Tovell H; Testa A; Zhou H; Shpiro N; Crafter C; Ciulli A; Alessi DR Design and Characterization of Sgk3-Protac1, an Isoform Specific Sgk3 Kinase Protac Degrader. ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14, 2024–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Chohan TA; Qayyum A; Rehman K; Tariq M; Akash MSH An Insight into the Emerging Role of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Agents for the Treatment of Advanced Cancers. Biomed. Pharmacother 2018, 107, 1326–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Laderian B; Fojo T Cdk4/6 Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy in Breast Cancer: Palbociclib, Ribociclib, and Abemaciclib. Semin. Oncol 2017, 44, 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Sherr CJ; Beach D; Shapiro GI Targeting Cdk4 and Cdk6: From Discovery to Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 353–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Olson CM; Jiang B; Erb MA; Liang Y; Doctor ZM; Zhang Z; Zhang T; Kwiatkowski N; Boukhali M; Green JL; Haas W; Nomanbhoy T; Fischer ES; Young RA; Bradner JE; Winter GE; Gray NS Pharmacological Perturbation of Cdk9 Using Selective Cdk9 Inhibition or Degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14, 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Jiang B; Wang ES; Donovan KA; Liang Y; Fischer ES; Zhang T; Gray NS Development of Dual and Selective Degraders of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 4 and 6. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2019, 58, 6321–6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Lu G; Middleton RE; Sun H; Naniong M; Ott CJ; Mitsiades CS; Wong KK; Bradner JE; Kaelin WG Jr. The Myeloma Drug Lenalidomide Promotes the Cereblon-Dependent Destruction of Ikaros Proteins. Science 2014, 343, 305–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Singh R; Letai A; Sarosiek K Regulation of Apoptosis in Health and Disease: The Balancing Act of Bcl-2 Family Proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2019, 20, 175–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kaefer A; Yang J; Noertersheuser P; Mensing S; Humerickhouse R; Awni W; Xiong H Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Meta-Analysis of Navitoclax (Abt-263) Induced Thrombocytopenia. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol 2014, 74, 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Khan S; Zhang X; Lv D; Zhang Q; He Y; Zhang P; Liu X; Thummuri D; Yuan Y; Wiegand JS; Pei J; Zhang W; Sharma A; McCurdy CR; Kuruvilla VM; Baran N; Ferrando AA; Kim YM; Rogojina A; Houghton PJ; Huang G; Hromas R; Konopleva M; Zheng G; Zhou D A Selective Bcl-X(L) Protac Degrader Achieves Safe and Potent Antitumor Activity. Nat. Med 2019, 25, 1938–1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Bray PF; McKenzie SE; Edelstein LC; Nagalla S; Delgrosso K; Ertel A; Kupper J; Jing Y; Londin E; Loher P; Chen HW; Fortina P; Rigoutsos I The Complex Transcriptional Landscape of the Anucleate Human Platelet. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Zhang X; Thummuri D; He Y; Liu X; Zhang P; Zhou D; Zheng G Utilizing Protac Technology to Address the on-Target Platelet Toxicity Associated with Inhibition of Bcl-X(L). Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2019, 55, 14765–14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Hirt UA; Waizenegger IC; Schweifer N; Haslinger C; Gerlach D; Braunger J; Weyer-Czernilofsky U; Stadtmüller H; Sapountzis I; Bader G; Zoephel A; Bister B; Baum A; Quant J; Kraut N; Garin-Chesa P; Adolf GR Efficacy of the Highly Selective Focal Adhesion Kinase Inhibitor Bi 853520 in Adenocarcinoma Xenograft Models Is Linked to a Mesenchymal Tumor Phenotype. Oncogenesis 2018, 7, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Aboubakar Nana F; Lecocq M; Ladjemi MZ; Detry B; Dupasquier S; Feron O; Massion PP; Sibille Y; Pilette C; Ocak S Therapeutic Potential of Focal Adhesion Kinase Inhibition in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther 2019, 18, 17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Zhao X; Guan JL Focal Adhesion Kinase and Its Signaling Pathways in Cell Migration and Angiogenesis. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2011, 63, 610–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Mitra SK; Hanson DA; Schlaepfer DD Focal Adhesion Kinase: In Command and Control of Cell Motility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2005, 6, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Cance WG; Kurenova E; Marlowe T; Golubovskaya V Disrupting the Scaffold to Improve Focal Adhesion Kinase-Targeted Cancer Therapeutics. Science signaling 2013, 6, pe10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Cromm PM; Samarasinghe KTG; Hines J; Crews CM Addressing Kinase-Independent Functions of Fak Via Protac-Mediated Degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17019–17026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Gschwind A; Fischer OM; Ullrich A The Discovery of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases: Targets for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Takeuchi K; Ito F Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Targeted Cancer Therapeutics. Biol. Pharm. Bull 2011, 34, 1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Burslem GM; Smith BE; Lai AC; Jaime-Figueroa S; McQuaid DC; Bondeson DP; Toure M; Dong H; Qian Y; Wang J; Crew AP; Hines J; Crews CM The Advantages of Targeted Protein Degradation over Inhibition: An Rtk Case Study. Cell Chem. Biol 2018, 25, 67–77 e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Stuhlmiller TJ; Miller SM; Zawistowski JS; Nakamura K; Beltran AS; Duncan JS; Angus SP; Collins KA; Granger DA; Reuther RA; Graves LM; Gomez SM; Kuan PF; Parker JS; Chen X; Sciaky N; Carey LA; Earp HS; Jin J; Johnson GL Inhibition of Lapatinib-Induced Kinome Reprogramming in Erbb2-Positive Breast Cancer by Targeting Bet Family Bromodomains. Cell reports 2015, 11, 390–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Jo M; Stolz DB; Esplen JE; Dorko K; Michalopoulos GK; Strom SC Cross-Talk between Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and C-Met Signal Pathways in Transformed Cells. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 8806–8811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Murray CW; Rees DC The Rise of Fragment-Based Drug Discovery. Nature chemistry 2009, 1, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Resnick E; Bradley A; Gan J; Douangamath A; Krojer T; Sethi R; Geurink PP; Aimon A; Amitai G; Bellini D; Bennett J; Fairhead M; Fedorov O; Gabizon R; Gan J; Guo J; Plotnikov A; Reznik N; Ruda GF; Díaz-Sáez L; Straub VM; Szommer T; Velupillai S; Zaidman D; Zhang Y; Coker AR; Dowson CG; Barr HM; Wang C; Huber KVM; Brennan PE; Ovaa H; von Delft F; London N Rapid Covalent-Probe Discovery by Electrophile-Fragment Screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 8951–8968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Backus KM; Correia BE; Lum KM; Forli S; Horning BD; González-Páez GE; Chatterjee S; Lanning BR; Teijaro JR; Olson AJ; Wolan DW; Cravatt BF Proteome-Wide Covalent Ligand Discovery in Native Biological Systems. Nature 2016, 534, 570–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Li BX; Xiao X Discovery of a Small-Molecule Inhibitor of the Kix-Kid Interaction. Chembiochem 2009, 10, 2721–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Vaquerizas JM; Kummerfeld SK; Teichmann SA; Luscombe NM A Census of Human Transcription Factors: Function, Expression and Evolution. Nature reviews. Genetics 2009, 10, 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Darnell JE Jr. Transcription Factors as Targets for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Xiao X; Li BX; Mitton B; Ikeda A; Sakamoto KM Targeting Creb for Cancer Therapy: Friend or Foe. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2010, 10, 384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Bartlett JB; Dredge K; Dalgleish AG The Evolution of Thalidomide and Its Imid Derivatives as Anticancer Agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Krönke J; Udeshi ND; Narla A; Grauman P; Hurst SN; McConkey M; Svinkina T; Heckl D; Comer E; Li X; Ciarlo C; Hartman E; Munshi N; Schenone M; Schreiber SL; Carr SA; Ebert BL Lenalidomide Causes Selective Degradation of Ikzf1 and Ikzf3 in Multiple Myeloma Cells. Science 2014, 343, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Sievers QL; Petzold G; Bunker RD; Renneville A; Słabicki M; Liddicoat BJ; Abdulrahman W; Mikkelsen T; Ebert BL; Thomä NH Defining the Human C2h2 Zinc Finger Degrome Targeted by Thalidomide Analogs through Crbn. Science 2018, 362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).O'Shea JJ; Schwartz DM; Villarino AV; Gadina M; McInnes IB; Laurence A The Jak-Stat Pathway: Impact on Human Disease and Therapeutic Intervention. Annu. Rev. Med 2015, 66, 311–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Johnson DE; O'Keefe RA; Grandis JR Targeting the Il-6/Jak/Stat3 Signalling Axis in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 2018, 15, 234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Debnath B; Xu S; Neamati N Small Molecule Inhibitors of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (Stat3) Protein. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2012, 55, 6645–6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Pallandre J-R; Borg C; Rognan D; Boibessot T; Luzet V; Yesylevskyy S; Ramseyer C; Pudlo M Novel Aminotetrazole Derivatives as Selective Stat3 Non-Peptide Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2015, 103, 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Beebe JD; Liu JY; Zhang JT Two Decades of Research in Discovery of Anticancer Drugs Targeting Stat3, How Close Are We? Pharmacol. Ther 2018, 191, 74–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Yang J; Liao X; Agarwal MK; Barnes L; Auron PE; Stark GR Unphosphorylated Stat3 Accumulates in Response to Il-6 and Activates Transcription by Binding to Nfkappab. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1396–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Bai L; Zhou H; Xu R; Zhao Y; Chinnaswamy K; McEachern D; Chen J; Yang CY; Liu Z; Wang M; Liu L; Jiang H; Wen B; Kumar P; Meagher JL; Sun D; Stuckey JA; Wang S A Potent and Selective Small-Molecule Degrader of Stat3 Achieves Complete Tumor Regression In vivo. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 498–511.e417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Zhou H; Bai L; Xu R; Zhao Y; Chen J; McEachern D; Chinnaswamy K; Wen B; Dai L; Kumar P; Yang CY; Liu Z; Wang M; Liu L; Meagher JL; Yi H; Sun D; Stuckey JA; Wang S Structure-Based Discovery of Sd-36 as a Potent, Selective, and Efficacious Protac Degrader of Stat3 Protein. J. Med. Chem 2019, 62, 11280–11300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Fuller JC; Burgoyne NJ; Jackson RM Predicting Druggable Binding Sites at the Protein-Protein Interface. Drug discovery today 2009, 14, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Gadd MS; Testa A; Lucas X; Chan KH; Chen W; Lamont DJ; Zengerle M; Ciulli A Structural Basis of Protac Cooperative Recognition for Selective Protein Degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 514–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Chong FP; Ng KY; Koh RY; Chye SM Tau Proteins and Tauopathies in Alzheimer's Disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 2018, 38, 965–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Jakob-Roetne R; Jacobsen H Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathology to Therapeutic Approaches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2009, 48, 3030–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Ittner LM; Ke YD; Delerue F; Bi M; Gladbach A; van Eersel J; Wölfing H; Chieng BC; Christie MJ; Napier IA; Eckert A; Staufenbiel M; Hardeman E; Götz J Dendritic Function of Tau Mediates Amyloid-Beta Toxicity in Alzheimer's Disease Mouse Models. Cell 2010, 142, 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Chu TT; Gao N; Li QQ; Chen PG; Yang XF; Chen YX; Zhao YF; Li YM Specific Knockdown of Endogenous Tau Protein by Peptide-Directed Ubiquitin-Proteasome Degradation. Cell Chem. Biol 2016, 23, 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Lu M; Liu T; Jiao Q; Ji J; Tao M; Liu Y; You Q; Jiang Z Discovery of a Keap1-Dependent Peptide Protac to Knockdown Tau by Ubiquitination-Proteasome Degradation Pathway. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 146, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Silva MC; Ferguson FM; Cai Q; Donovan KA; Nandi G; Patnaik D; Zhang T; Huang HT; Lucente DE; Dickerson BC; Mitchison TJ; Fischer ES; Gray NS; Haggarty SJ Targeted Degradation of Aberrant Tau in Frontotemporal Dementia Patient-Derived Neuronal Cell Models. eLife 2019, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Downward J Targeting Ras Signalling Pathways in Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]