Summary

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide. Previous reviews investigating the role of circumcision in preventing HIV and other STIs among MSM were inconclusive. A large number of new studies have emerged in the past decade. To inform global HIV/STI prevention strategies among MSM, we reviewed all available evidence on the associations between circumcision and HIV/STIs among MSM.

Methods

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, Web of Science, BioMed Central, Scopus, Research Gate, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and websites of international HIV/STI conferences for studies published before March 8, 2018. Interventional or observational studies containing original quantitative data describing associations between circumcision and incident or prevalent infection of HIV and other STIs among MSM were included. Studies were excluded if MSM could not be distinguished from men who have sex with women only. We calculated pooled odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using random-effect models. We assessed risk of bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Findings:

We identified 62 observational studies involving a total of 119 248 MSM. Circumcision was associated with 23% reduced odds of HIV infection among MSM overall (OR 0·77, 95% CI 0·67-0·89; number of estimates [k]=45; heterogeneity I2=77%). Circumcision was protective against HIV infection among MSM in LMICs (0·58, 0·41-0·83; k=23; I2=77%) but not among MSM in high-income countries (0·99, 0·90-1·09; k=20; I2=40%). Circumcision was associated with reduced odds of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection among MSM overall (0·84, 0·75-0·95; k=5; I2=0%) and penile human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among HIV-infected MSM (0·71, 0·51-0·99; k=3; I2=0%).

Interpretation

We found evidence that circumcision is likely to protect MSM from HIV infection, particularly in LMICs. Circumcision may also protect MSM from HSV and penile HPV infection. MSM should be included in campaigns promoting circumcision among men in LMICs. Given the substantial proportion of MSM in LMICs who also have sex with women, well-designed longitudinal studies differentiating MSM only and bisexual men are needed to clarify the effect of circumcision on male-to-male transmission of HIV and other STIs.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship, Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, National Institutes of Health, Mega Projects of National Science Research for the 13th Five-Year Plan, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV worldwide.1 Although HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), treatment of partners, and behavioural risk reduction are all effective in preventing HIV transmission among MSM, the HIV epidemic still contributes to substantial morbidity and mortality among MSM.2 MSM in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are particularly impacted.2 Limited HIV prevention resources and entrenched stigma against MSM hamper access to HIV testing and treatment in LMICs.2 Other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including syphilis, herpes simplex virus (HSV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, and human papillomavirus (HPV), also disproportionately affect MSM and may increase risk of HIV infection.3 Evidence-based prevention approaches are urgently needed to optimize combination strategies to prevent HIV and other STIs among MSM.

The efficacy of male circumcision in preventing HIV among heterosexual men is well documented. Three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in Africa demonstrated that circumcision can reduce the risk of female-to-male transmission of HIV by 50% to 60%.4–6 The biological plausibility of circumcision to prevent HIV infection is also supported by immunohistological and histopathological studies that found a higher density of HIV target cells in the inner mucosa of the foreskin.7,8

It remains unclear whether MSM similarly benefit from circumcision.9–11 Existing male circumcision programmes primarily target heterosexual men and have not actively promoted circumcision among MSM.12 Two earlier systematic review and meta-analysis papers reported on the associations between circumcision and HIV infection and other STIs among MSM in 2008 and 2011.9,10 Analyzing results from more than 20 observational studies, these meta-analyses found non-significant associations between circumcision and HIV infection and other STIs among MSM overall.9,10 Significant protective associations between circumcision and HIV infection were identified in sub-analyses of studies conducted before the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy1 and among MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal sex.10 A recent meta-analysis including 18 observational studies reported that circumcision was associated with 20% (95% confidence interval [CI] 0·69-0·92) reduced odds of HIV infection among MSM overall, however not among MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal sex.11

A large amount of new evidence has emerged, especially from LMICs, in the past decade.13–50 To inform global HIV and STI prevention strategies for MSM, we conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on the association between circumcision and HIV and other STIs among MSM, stratifying important parameters.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines.51,52 We searched PubMed, Web of Science, BioMed Central, Scopus, Research Gate, Cochrane Library, EM BASE, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and websites of five international HIV/STI conferences (World AIDS Conference, International AIDS Society Conference, Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research Conference, and International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections Conference) for studies published before March 8, 2018. We used the search terms (“circumcision”, “circumcised”, OR “uncircumcised”) AND (“male sexual minorities”, “male homosexuality”, “men who have sex with men”, “MSM”, “homosexual”, “gay” OR “bisexual”). References of retrieved full-text articles and other reviews were screened for additional eligible publications.

We included studies that recruited MSM, included circumcision status as a study variable, and reported estimates of associations between circumcision status and incident or prevalent HIV/STIs among MSM. Interventional, cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies were all eligible for inclusion. Studies were excluded if MSM could not be distinguished from men who have sex with women. We included multiple publications from one common study if each publication reported separate data sets.

Two authors (TY and HZ) independently performed the search and assessed each study for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion among the two authors.

Data analysis

Two authors (TY and HZ) independently extracted the following study-level characteristics: first author, publication year, study country, years during which participants were recruited, study design, length of follow-up, recruitment setting, specific STIs and their infection sites, method of ascertaining HIV/STI status, method of ascertaining circumcision status, sample size, mean or median age of participants, the proportion of circumcised MSM, the number of HIV/STI cases among MSM by circumcision status, and association estimates of HIV/STI risks comparing circumcised and uncircumcised MSM. Disagreements in extracted data were resolved through discussion among two authors (TY and HZ). Because other HIV prevention and treatment measures may mask the protective effect of circumcision, we also extracted the proportion of HIV-positive MSM receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), proportion of MSM self-reporting HIV testing history, and proportion of MSM self-reporting consistent condom use, where available. To investigate effects of geographic, socioeconomic, and cultural factors, study countries were grouped by WHO region, income level,53 and official position on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights as expressed in joint statements to the United Nations General Assembly or the United Nations Human Rights Council.54

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess the methodological quality of included cohort and case-control studies.55 An adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale developed by Herzog et al was used for cross-sectional studies.56 We planned to use a checklist developed by Downs et al to assess risk of bias of included interventional studies.57 Two authors (TY and HZ) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies and quality of evidence. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion among all authors.

Odds ratios (ORs) were used to report associations between circumcision and HIV infection and other STIs among MSM, with an OR lower than 1·0 representing a protective effect of circumcision. ORs and their 95% CIs were extracted directly from articles where available, with adjusted ORs extracted preferentially over unadjusted ORs. If an included study did not report ORs, crude ORs were calculated from extracted data.

Because included studies differed in study design, we assumed a high potential for heterogeneity between included studies, and thus a random effects model was used to calculate pooled effect sizes.58 Our primary outcome was the pooled OR estimate of the association between circumcision and HIV infection in MSM. Our secondary outcomes were pooled OR estimates of the association between circumcision and STIs other than HIV infection in MSM. As in a previous meta-analysis,9 we first calculated a pooled association estimate between circumcision and all STIs other than HIV as a single composite outcome using the method developed by Borenstein et al to ensure the independence of individual effect sizes.59 We then calculated individual ORs for specific STIs when two or more studies reported outcomes for HPV, HSV, syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Additionally, we performed random-effects cumulative meta-analyses to delineate temporal changes in the magnitude and direction of pooled association estimates as evidence accumulated over time.60 Studies were sorted by year of publication and sequentially added to the analysis in chronological order, with pooled estimates recalculated with each added study.

The I2 statistic was used to assess the level of heterogeneity across included studies, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.61 If substantial heterogeneity was detected, we performed univariate meta-regression analyses to explore the proportion of between-study variance explained by study quality, participant characteristics, and study characteristics. We were unable to perform a multivariate meta-regression analysis as only a small number of included studies reported information for all study-level factors. We also performed subgroup analyses by participant and study characteristics to compare pooled association estimates and heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and the Egger’s test.62 Potential outliners were detected in sensitivity analysis by removing each estimate one at a time and recalculating the pooled estimates. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by restricting ORs adjusted for potential confounders.

All data analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). Full details of the data extraction and analyses are provided in the appendix.

Role of the funding source

Study funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

We identified 67 eligible publications12–49,63–91 arising from 62 independent observational studies (n=119248 participants). Thirty-three studies12–14,17,18,20,21,23,25,27–30,36,37,41,43,44,46,63,64,66,67,69,75–78,80–86,89,90 only reported HIV infection as an outcome, 16 reported STIs other than HIV as outcomes,19,22,32,34,35,42,45–49,65,68,70,74 and 13 reported both HIV infection and other STIs as outcomes.15,16,24,26,31,33,38,40,71–73,79,86,88,91 Four studies (2 for HIV15,29 and 2 for STIs65,90) were excluded from the meta-analysis because they failed to report data necessary to calculate ORs (figure1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of publication selection

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of included studies. Details of each study are presented in the appendix. Included studies were conducted between 1989 and 2016 and published between 1993 and 2017. The number of MSM enrolled in each study ranged from 49 to 25159. Mean or median age of MSM varied from 18 to 46 years (median=29 years; 58 studies). The proportion of circumcised men ranged from 4% to 96% (median=34%; 56 studies). The proportion of HIV-infected MSM using ART at enrollment varied from 30% to 87% (median=66%; 5 studies). The proportion of MSM self-reporting previous HIV testing ranged from 37% to 93% (median= 53%; 17 studies), and consistent condom use ranged from 12% to 83% (median= 38%; 20 studies).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies*

| Characteristics | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Publication type | |

| Journal article | 58 |

| Conference abstract | 7 |

| Doctoral/Master’s thesis | 2 |

| Study design | |

| Cohort† | 15 |

| Case-control‡ | 2 |

| Cross-sectional§ | 45 |

| WHO region¶ | |

| Americas | 18 |

| Western Pacific | 19 |

| South-East Asia | 9 |

| Africa | 6 |

| Europe | 5 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 1 |

| Income of country¶ | |

| High | 26 |

| Upper-middle | 24 |

| Lower-middle | 7 |

| Low | 2 |

| Official position on LGBT rights¶ | |

| Support | 35 |

| Oppose | 4 |

| Neither | 21 |

| Recruitment setting‖ | |

| Non-clinic-based | 40 |

| Clinic-based | 16 |

WHO=world health organization. LGBT= lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

We identified 62 studies from 67 publications; one study split results into three parts and reported each part in different journals,16,87,88 and another three studies36,76,82 reported additional data in conference abstracts.30,75,81

one study84 was nest case-control in design.

Of the 45 studies that examined the association between circumcision and HIV status among MSM, 29 reported non-significant associations. Eleven found circumcision to have a significant protective association with HIV infection among all MSM.17,18,40,63,64,73,75,76,83,86,87,90 Two found a significant protective association with circumcision only among MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal sex.24,86 Two reported a significant protective association with circumcision only among men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW).30,36,41 One included studies that found circumcised MSM to be at significantly increased odds of HIV infection.44

Of the 29 studies that examined the association between circumcision and STIs other than HIV among MSM, 19 reported non-significant associations. One reported circumcision was associated with significantly less multiplicity of HPV genotypes and lower prevalence of high-risk HPV genotypes.24 One reported a significant protective effect for penile HPV infection.46 One found a significant protective association between circumcision and incident HPV infection among MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal intercourse.16 Three reported a significant protective effect for syphilis infection.31,73,88 A significant protective association between circumcision and HSV,72 HBV,48 and gonorrhea infection65 was reported by one study, respectively. Circumcised MSM were at significantly increased odds of non-chlamydial non gonococcal urethritis74 and recurrent STI70 in one included study, respectively.

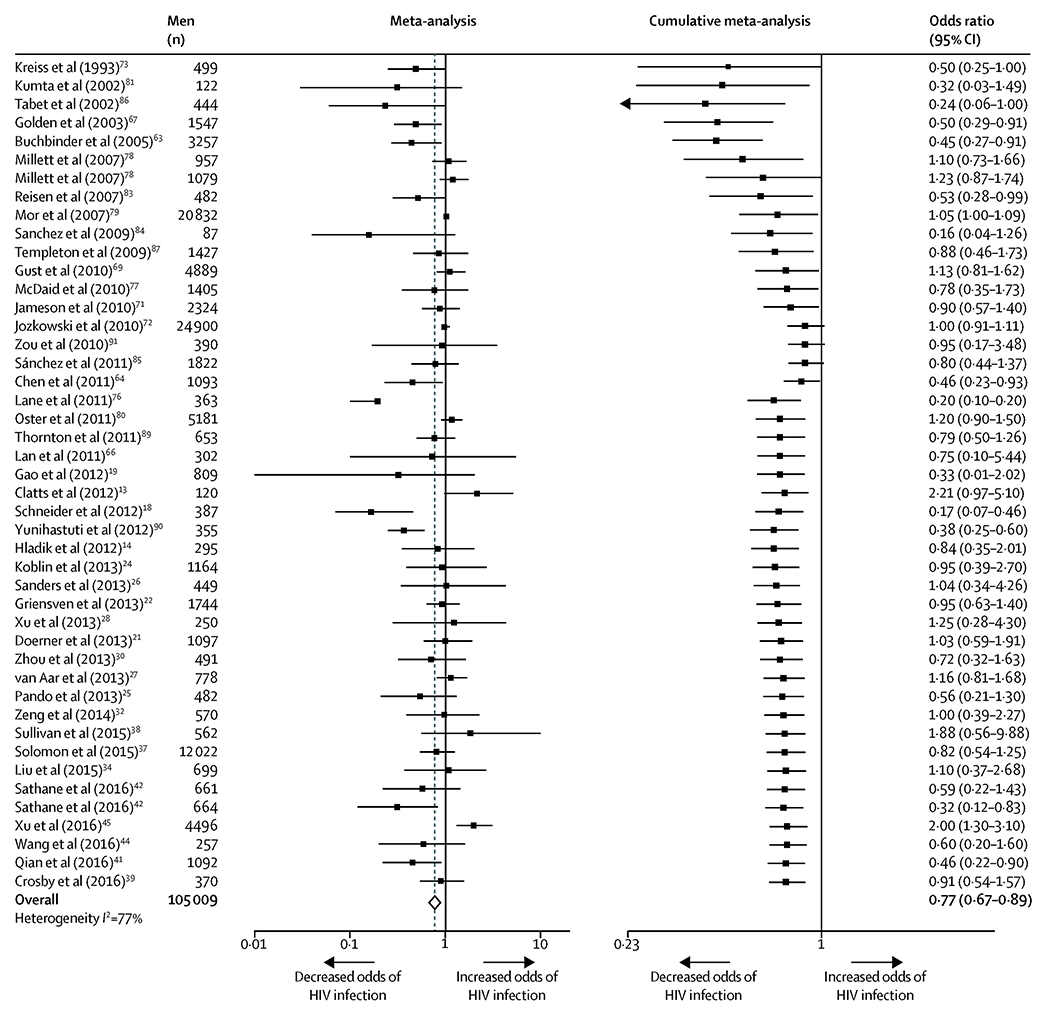

Forty-three studies (n=105 009 participants) were included in the meta-analysis of the association between circumcision and HIV infection in MSM. Circumcision was associated with 23% lower odds of HIV infection in MSM overall (OR 0·77, 95% CI 0·67-0·89; number of estimates [k]=45; I2=77%). The cumulative meta-analysis suggested that this protective association became evident since 2011 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis and cumulative meta-analysis of the association between circumcision and HIV infection among MSM

In cumulative meta-analysis, studies were sorted by year of publication and sequentially added to the analysis in chronological order, with pooled estimates recalculated with each added study.

All estimates are independent. One study could contribute more than one estimate only when data from independent populations were analyzed and reported separately.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; CI, confidence interval.

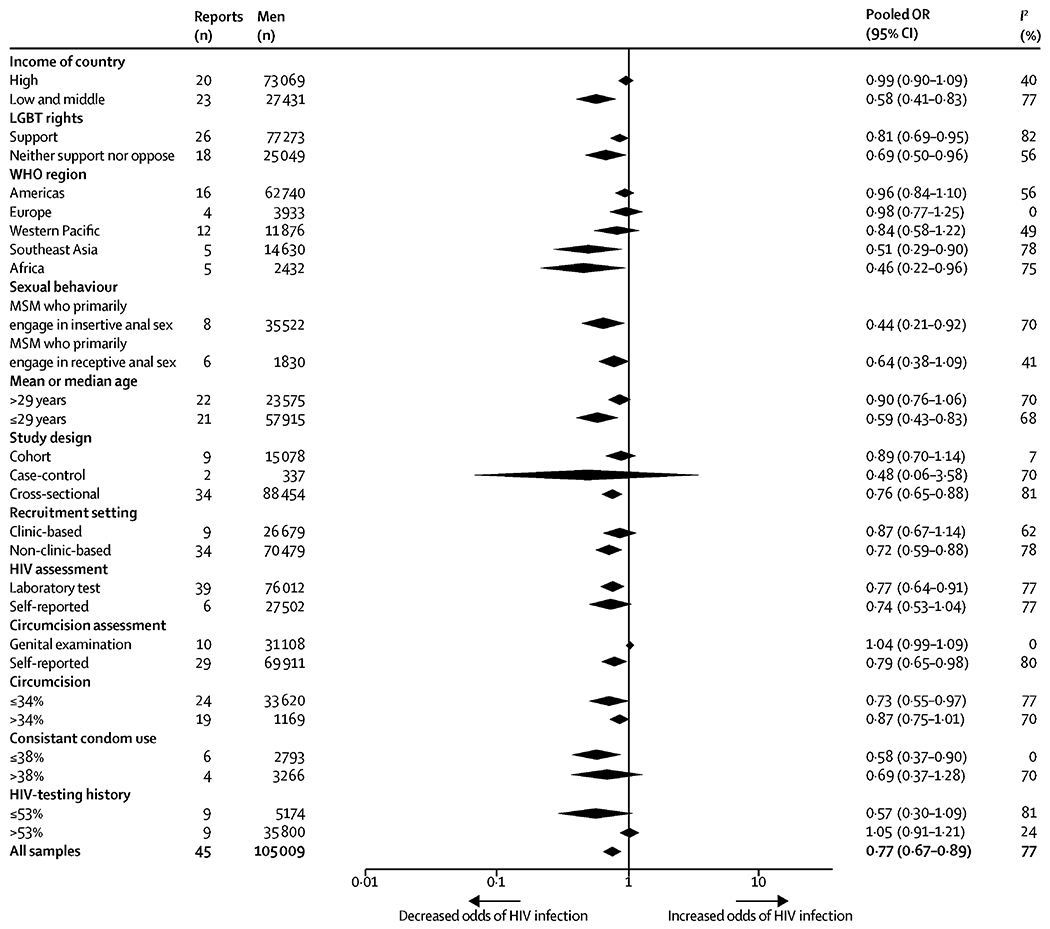

In subgroup analysis (figure 3), this protective association was significantly stronger (95% CIs did not overlap) in LMICs (0·58, 0·41-0·83; k=23; I2=77%) than in high-income countries (0·99, 0·90-1·09; k=20; I2=40%). Compared to the overall pooled estimate, this protective association remained significant and tended to be stronger among MSM from Southeast Asia or Africa, MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal sex, younger MSM, non-clinic-based studies, and studies in which the proportion of MSM self-reporting consistent condom use was lower. Details of all subgroup analyses are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Subgroup meta-analyses of the association between circumcision and HIV infection among MSM.

Cut-off points of continuous variables were medians.

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CI, confidence interval; MSM; men who have sex with men; LGBT, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

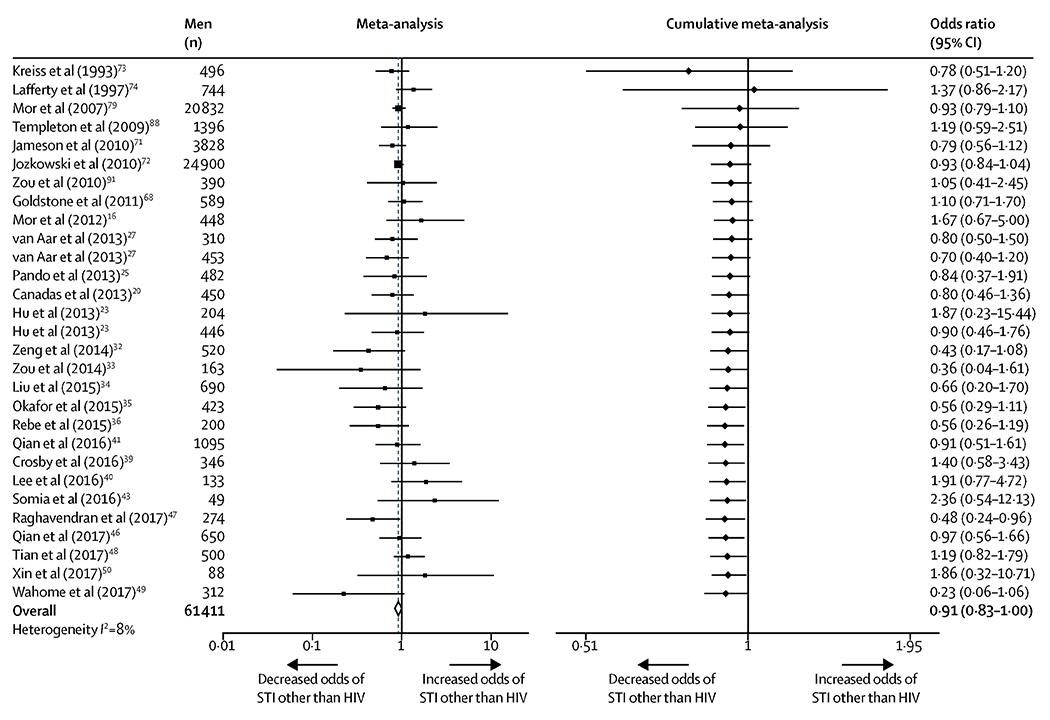

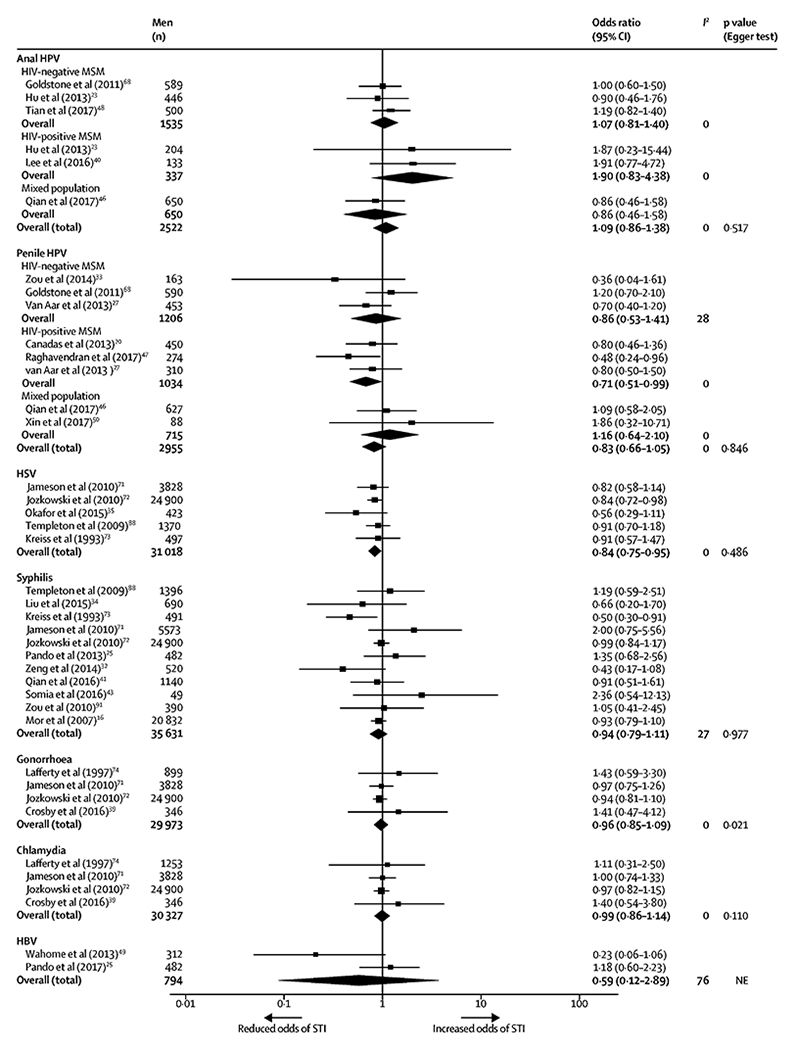

Twenty-seven studies (n=61411 participants) were included in the meta-analysis of associations between circumcision and STIs other than HIV. Circumcision was associated with reduced odds of any STI other than HIV (OR 0·91, 95% CI 0·83-1·00; k=29; I2=8%), which became evident from available publications in 2013 (figure 4). In meta-analyses calculating associations between circumcision and specific STIs (figure 5), circumcision was associated with reduced odds of HSV infection among MSM overall (0·84, 0·75-0·95; k=5; I2=0%). The significant protective association between circumcision and penile HPV infection was only observed among MSM living with HIV (0.71, 95% CI 0·51-0·99; k=3; I2=0%). The odds of infection with anal HPV, syphilis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HBV did not differ significantly between circumcised and uncircumcised MSM.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis and cumulative meta-analysis of the association between circumcision and any STI other than HIV among MSM.

In cumulative meta-analysis, studies were sorted by year of publication and sequentially added to the analysis in chronological order, with pooled estimates recalculated with each added study.

To ensure the independence of effects, each study contributed only one estimate unless data from independent populations were analyzed and reported separately.

If a study reported multiple individual association estimates between circumcision and different infection sites or STIs in the same population, a summary OR of all STIs (excluding HIV) was calculated for that study population using the formula developed by Borenstein et al.63

Abbreviations: STI, sexually transmitted infection; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MSM, men who have sex with men; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Meta-analyses of the associations between circumcision and specific STIs among MSM.

Associations between circumcision and anal HPV infection and penile HPV infection were calculated separately and stratified by HIV-status of participants.

Abbreviation: STI, sexually transmitted infection; MSM, men who have sex with men; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus, including both HSV-1 and HSV-2; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

There was substantial heterogeneity (I2=77%) across studies that reported HIV infection as an outcome. In univariate meta-regression analyses, this high heterogeneity was explained by the income level of countries (R2=19%), mean or median age of MSM (R2=18%) and the proportion of MSM self-reporting HIV-testing history (R2=34%) (all p<0·05; appendix). In subgroup analyses (figure 3), the high level of heterogeneity disappeared, or was substantially reduced, in studies conducted in Europe, cohort studies, studies where circumcision was determined by genital examination, the proportion of MSM self-reporting consistent condom use was lower, and the proportion of MSM having HIV-testing history was higher (I2 range, 0%-24%). Heterogeneity across studies that reported any STI other than HIV was low (I2 range, 0%-28%), except for two studies that reported HBV infection, which had high heterogeneity (I2=76%).

There was evidence of publication bias in studies reporting HIV infection (asymmetrical funnel plot, and p=0·003 by Egger test; appendix) and gonorrhea infection (p=0·02 by Egger test). Sensitivity analyses detected one study76 as having a large but statistically non-significant impact on the pooled association estimate between circumcision and HIV infection (appendix). Restricting the meta-analysis to the 13 studies17,29,41,44,63,64,73,76,77,78,80,83,89 that adjusted for potential confounders increased the magnitude of the protective association between circumcision and HIV infection (OR 0·64, 95% CI 0·45-0·93; k=15; I2=87%). Thirty-two (52%) of 62 studies were rated as low risk of bias, with all remaining studies rated as high risk of bias (appendix).

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies from both LMICs and high-income countries, we found circumcision was associated with a 23% reduced odds of HIV infection among MSM overall, with this protective association being stronger in LMICs. Circumcision was associated with significantly reduced odds of HSV infection among MSM overall and penile HPV infection among MSM living with HIV.

Our finding that circumcision is significantly associated with lower rates of HIV infection among MSM differs from two previous systematic reviews published in 2008 and 2011.9,10 Compared to these reviews we included 22 additional studies,16 of which were from LMICs, a setting in which the association between circumcision and lower rates of HIV was particularly pronounced. Additionally, in cumulative meta-analysis the significant protective effect of circumcision only became apparent in 2011, after the publication of the last comprehensive systematic review on the subject.10 The recent systematic review published in 2018 included all males and MSM was only a fraction of the analysis and that paper missed a significant amount of existing evidence,11 which may potentially lead to a biased conclusion with limited stratified findings.

The protective effect of circumcision against HIV infection was significantly stronger among MSM in LMICs compared to MSM in high-income countries. Several reasons could explain this difference. Mathematical modelling studies suggest this enhanced protective effect may be due to the higher stability in anal sex role segregation, lower rates of circumcision, and higher HIV prevalence among MSM in LMICs.92,93 MSMW represent a substantial proportion of MSM in LMICs and may be another explanatory factor. Behavioural studies in China, India, Peru, and sub-Saharan Africa have found that 40% to 70% of MSM have also had sex with women,36,86,94,95 and nearly 30% are married to women.36,95 Circumcision could be effective in reducing HIV acquisition among MSMW by reducing female-to-male HIV transmission.4–6 Rates of insertive anal intercourse are also higher among MSMW,94 the sex position for which circumcision offers direct benefit.10 Additionally, fewer protective measures against HIV infection are available in LMICs compared to high-income countries.2 Observational studies conducted in these contexts may be less impacted by other interventions that mask the effectiveness of circumcision to prevent infection. This interpretation is consistent with our sub-analyses which found the protective effect increased as the proportion of MSM receiving additional HIV protective measures (e.g. condom use, HIV testing) decreased.

Circumcision was found to be significantly associated with reduced odds of HSV infection among MSM overall. The protective association between circumcision and penile HPV infection was only significant among MSM living with HIV. This selective effect may be due to high HPV prevalence and increased susceptibility to HPV infection among people living with HIV.96 Similar protective effects against HSV and HPV infection have also been described among heterosexual men.97–99

It is biologically plausible that circumcision may protect against HIV and other STIs. Circumcision decreases number of target cells for pathogens to infect, eliminates a microenvironment favoring pathogen survival and replication, and reduces the potential for micro-abrasions during sexual intercourse that allow for the entry of pathogens into the body.100 The protective association between circumcision and other STIs may be less apparent than the association with HIV infection because other STIs are more effectively transmitted through sexual behaviors besides anal intercourse (e.g., syphilis transmission can occur via intimate skin to skin contact),101 thereby reducing the protective effect of circumcision.

There are several limitations to this review. First, our meta-analysis was based on observational data. More than half of included studies were cross-sectional and rated as having high risk of bias. However, the protective effect of circumcision was more apparent in non-clinic-based studies and studies that controlled for potential confounders, suggesting that the association between circumcision and lower rates of HIV infection may not be the result of confounding. Second, we found evidence of publication bias in our analysis. Disproportionate reporting of significant associations in the published literature may result in an overestimate of the protective effect of circumcision. Finally, only a small number of studies were included in several subgroup categories. Findings from these meta-analyses should be considered preliminary and warrant further investigation when more data becomes available.

Further research is needed to better characterize the effect of circumcision on HIV, HSV, and HPV transmission among MSM. Although RCTs of circumcision among MSM in LMICs could confirm this protective effect, evidence from this meta-analysis is not strong enough to support the development of an RCT. The protective effect of circumcision observed in LMICs may be explained by the prevention of female-to-male HIV transmission among MSMW rather than prevention of HIV transmission during anal sex. Because of the disparate anatomical and biological environment of vaginal and rectum, the effect of circumcision on HIV/STI transmission during vaginal intercourse and anal intercourse might be different. Additionally, recruiting eligible participants for an RCT would be difficult because of widespread stigma against MSM in LMICs. The willingness of being circumcised among MSM in LMICs is low. A study in 2009 in China found that only 17% of MSM were willing to be circumcised.102 And a study conducted in Argentina found that 70% of uncircumcised MSM opted not to undergo circumcision after being informed of potential reduced risk of HIV infection.24 Given the paucity of high-quality cohort studies identified in this review, well-designed longitudinal studies are needed to further clarify the effect of circumcision on the transmission of HIV, HPV, and HSV during anal intercourse. Such longitudinal studies should differentiate MSM and MSMW so as to disentangle the effect of circumcision on male-to-male and female-to-male transmission of HIV and other STIs. It is essential to identify factors affecting the willingness to undergo circumcision among MSM in LMICs and design effective interventions to improve such willingness.

Our finding that circumcision is more likely to protect MSM in LMICs from HIV infection is promising given the high risk of HIV infection among MSM in these settings as a result of heavy stigma and restricted access to HIV prevention measures (e.g., PrEP).2 MSM in LMICs could benefit from the advances in cheap, safe, and convenient circumcision surgical techniques (e.g., Shang Ring).103 Because circumcision as an HIV prevention measure targets all men regardless of sexual orientation, MSM in LMICs seeking circumcision would likely experience less stigma when accessing this service. Although circumcision offers the most direct protection to MSM who primarily engage in insertive anal sex, high coverage of circumcision among MSM overall may reduce HIV prevalence at a population level and therefore indirectly protect MSM who engage in receptive anal sex. Our findings also suggest that interventions to increase circumcision among MSM may protect against other STIs, including HSV and HPV. Consequently, MSM should not be excluded from campaigns promoting circumcision among men in LMICs, and mathematical modelling studies should be developed to evaluate the public health impact and cost-effectiveness of the large-scale circumcision programs for HIV prevention among MSM in individual LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Panel: Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Two previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in 2008 and 2012 found non-significant protective associations between circumcision and HIV infection and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among men who have sex with men (MSM). Since these reviews were published a large amount of new evidence has emerged. A 2018 meta-analysis found circumcision was associated with a 20% reduced risk of HIV infection among MSM. However, this analysis included only 18 studies and did not include a substantial proportion of published data. We conducted a comprehensive updated review of associations between circumcision and HIV and other STIs among MSM.

Added value of this study

Our review included 62 observational studies from both high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and found that circumcision was associated with 23% reduced odds of HIV infection among MSM overall. This association was significantly stronger among MSM in LMICs compared to MSM in high-income countries. Circumcision was significantly associated with reduced odds of HSV infection among MSM overall and penile HPV infection among MSM living with HIV.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our analysis suggests circumcision may protect MSM from HIV, HSV, and penile HPV infection. Given the low quality of evidence and a substantial proportion of MSM in LMICs who also have sex with women, well-designed longitudinal studies differentiating MSM and men who have sex with men and women are needed to clarify the effect of circumcision on male-to-male transmission of HIV and other STIs. MSM should be included in campaigns promoting circumcision among men in LMICs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Peiyang Li and Dong Xu for very helpful comments on the draft manuscript, Ganfeng Luo for providing advice on statistical analysis, and Changchang Liu for helping plot graphs. HZ is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant ID: 81703278), Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen, National Institutes of Health, and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (grant ID: APP1092621). YQC is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 MH105857 and R01 AI121259. YC is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant ID: 71673187). JX is supported by the Mega Projects of National Science Research for the 13th Five-Year Plan (grant ID: 2017ZX10201101-002-007). JZ is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant ID: 81573211). JL is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China under a young scientists’ grant (81803334). TF is supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2012; 380: 367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2012; 380: 388–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS, et al. Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: e235–e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwitambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial. Plos Medicine 2005; 2: e298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 643–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet 2007; 369: 657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson BK, Landay A, Siegel JN, et al. Susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection of human foreskin and cervical tissue grown in explant culture. American Journal of Pathology 2002; 161: 867–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mccoombe SG, Short RV. Potential HIV-1 target cells in the human penis. Aids 2006; 20: 1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH. Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008; 300: 1674–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiysonge CS, Kongnyuy EJ, Shey M, et al. Male circumcision for prevention of homosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 39: CD007496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SC, Raison N, Khan S, Shabbir M, Dasgupta P, Ahmed K. Male circumcision for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition: a meta-analysis. BJU Int 2018; 121: 515–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hines JZ, Ntsuape OC, Malaba K, et al. Scale-Up of Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Services for HIV Prevention - 12 Countries in Southern and Eastern Africa, 2013-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66: 1285–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clatts MC, Rodríguez-Díaz CE, García H, Vargas-Molina RL, Jovet-Toledo GG, L G. A preliminary profile of HIV risk in a clinic-based sample of MSM in Puerto Rico: implications for sexual health promotion interventions. P R Health Sci J 2012; 31: 154–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hladik W, Barker J, Ssenkusu JM, et al. HIV Infection among men who have sex with men in Kampala, Uganda–a respondent driven sampling survey. PloS One 2012; 7: e38143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Noonan E, et al. Sexual Risk Behaviors, Circumcision Status, and Preexisting Immunity to Adenovirus Type 5 Among Men Who Have Sex With Men Participating in a Randomized HIV-1 Vaccine Efficacy Trial: Step Study. Jaids-Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 2012; 60: 405–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mor Z, Shohat T, Goor Y, Dan M. Risk behaviors and sexually transmitted diseases in gay and heterosexual men attending an STD clinic in Tel Aviv, Israel: a cross-sectional study. Isr Med Assoc J 2012; 14: 147–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poynten IM, Jin F, Templeton DJ, et al. Prevalence, Incidence, and Risk Factors for Human Papillomavirus 16 Seropositivity in Australian Homosexual Men. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39: 726–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider JA, Michaels S, Gandham SR, et al. A protective effect of circumcision among receptive male sex partners of Indian men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2012; 16: 350–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao YJ. HIV/AIDs prospective cohort study among men who have sex with men in Beijing. Masters thesis, Hebei Medical University [master’s thesis], Heibei, China: Hebei Medical University; 20123. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadas MP, Darwich L, Videla S, et al. Circumcision and penile human papillomavirus prevalence in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: heterosexual and men who have sex with men. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19: 611–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doerner R, McKeown E, Nelson S, Anderson J, Low N, Elford J. Circumcision and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Britain: the insertive sexual role. Archives of sexual behavior 2013; 42: 1319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griensven V, Thienkrua W, Mcnicholl J, et al. Evidence of an explosive epidemic of HIV infection in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Thailand. AIDS 2013; 27: 825–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y, Qian HZ, Sun J, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection among HIV-infected and uninfected men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 64: 103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH, et al. Correlates of HIV Acquisition in a Cohort of Black Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States: HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 061. PLoS One 2013; 8: e70413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pando MA, Balan IC, Dolezal C, et al. Low frequency of male circumcision and unwillingness to be circumcised among MSM in Buenos Aires, Argentina: association with sexually transmitted infections. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16: 18500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders EJ, Okuku HS, Smith AD, et al. High HIV-1 incidence, correlates of HIV-1 acquisition, and high viral loads following seroconversion among men who have sex with men in Coastal Kenya. AIDS 2013; 27: 437–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van AF, Mooij SH, Ma VDS, et al. Anal and penile high-risk human papillomavirus prevalence in HIV-negative and HIV-infected MSM. AIDS 2013;27: 2921–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu HL, Jia MH, Min XD, et al. Factors influencing HIV infection in men who have sex with men in China. Asian J Androl 2013; 15: 545–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu JJ, An M, Han X, et al. Prospective cohort study of HIV incidence and molecular characteristics of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Yunnan Province, China. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou C, Raymond HF, Ding X, et al. Anal sex role, circumcision status, and HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chongqing, China. Arch Sex Behav 2013; 42: 1275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon S, Mehta S, Srikrishnan A, et al. Circumcision is associated with lower HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in India [abstract MOPE157]. Abstract presented at: the 20th International AIDS Conference; July 20-25, 2014; Melbourne, Australia; 2014; Abstract Archive; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng Y, Zhang L, Li T, et al. Risk factors for HIV/syphilis infection and male circumcision practices and preferences among men who have sex with men in China. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 498987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou H, Tabrizi SN, Grulich AE, et al. Early Acquisition of Anogenital Human Papillomavirus Among Teenage Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Infect Dis 2014; 209: 642–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G, Lu H, Wang J, et al. Incidence of HIV and syphilis among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Beijing: an open cohort study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0138232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okafor N, Rosenberg ES, Luisi N, et al. Disparities in herpes simplex virus type 2 infection between black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA. International Journal of Std & Aids 2015; 26: 740–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rebe K, Lewis D, Myer L, et al. A cross sectional analysis of gonococcal and chlamydial Infections among men-who-have-sex-with-men in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0138315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solomon S, Mehta S, Srikrishnan A, et al. High HIV prevalence and incidence among MSM across 12 cities in India. AIDS 2015; 29: 723–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, et al. Explaining Racial Disparities in HIV Incidence in a Prospective Cohort of Black and White Men Who Have Sex With Men in Atlanta, GA: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Ann Epidemiol 2015; 25: 445–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crosby RA, Graham CA, Mena L, et al. Circumcision Status is Not Associated with Condom Use and Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Young Black MSM. AIDS Behav 2016; 20: 2538–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee CH, Lee SH, Lee S, et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection among HIV-infected men in Korea. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0161460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian H, Ruan Y, Liu Y, et al. Lower HIV Risk Among Circumcised Men Who Have Sex With Men in China: Interaction With Anal Sex Role in a Cross-Sectional Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 71: 444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sathane I, Horth R, Young P, et al. Factors Associated with HIV Among Men Who Have Sex Only with Men and Men Who Have Sex with Both Men and Women in Three Urban Areas in Mozambique. AIDS Behav 2016; 20: 2296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Somia I, Merati K, Sukmawati D, Phanuphak N, Indira I, Prasetia M, Amijaya K, Sawitri A. The Effects of Syphilis Infection on CD4 Counts and HIV-1 RNA Viral Loads in Blood: A Cohort Study Among MSM with HIV Infection in Sanglah Hospital Bali-Indonesia. Bali Medical Journal 2016; 5: 391–4. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang N, Wu G, Lu R, et al. Investigating HIV Infection and HIV Incidence Among Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men with Recent Sexual Debut, Chongqing, China, 2011. AIDS and Behavior 2016; 20: 2976–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu JJ, Tang WM, Zou HC, et al. High HIV incidence epidemic among men who have sex with men in china: results from a multi-site cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Poverty 2016; 5: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian H, Hu Y, Carlucci J, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status Differentially Associated With Genital and Anal Human Papillomavirus Infection Among Chinese Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44: 656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raghavendran A, Hernandez AL, Lensing S, et al. Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection in Indian HIV-Seropositive Men Who Have Sex With Men. Sex Transm Dis 2017; 44: 173–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian T, Mijiti P, Bingxue H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anal human papillomavirus infection among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Urumqi city of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0187928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wahome E, Ngetsa C, Mwambi J, et al. Hepatitis B virus incidence and risk factors among human immunodeficiency virus-1 negative men who have sex with men in Kenya. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: ofw253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xin H, Li H, Li Z, et al. Genital HPV infection among heterosexual and homosexual male attendees of sexually transmitted diseases clinic in Beijing, China. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 145: 2838–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMC 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.New country classifications by income level: 2017–2018. World Bank website; https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2017-2018 (accessed February 19 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54.LGBT rights by country or territory. Wikipedia website; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LGBT_rights_by_country_or_territory (accessed March 9 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Health Research Institute Web site; http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed January 3 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herzog R, Álvarezpasquin MJ, Díaz C, Barrio JLD, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52: 377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed and random effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Meth 1998; 3: 486–504. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2009. https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/Meta-analysis%20Studies%20with%20multiple%20subgroups%20or%20outcomes.pdf (accessed March 19 2018).

- 60.Leimu R, Koricheva J. Cumulative Meta-Analysis: A New Tool for Detection of Temporal Trends and Publication Bias in Ecology. Proc Biol Sci 2004; 271: 1961–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty PJ, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 39: 82–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen YJ, Lin YT, Chen M, et al. Risk factors for HIV-1 seroconversion among Taiwanese men visiting gay saunas who have sex with men. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11: 334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Curlin ME, Pattanasin S, Luechai P, et al. Incident symptomatic gonorrhea infection among men who have sex with men, Thailand [abstract 1026]. Abstract presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 23-26, 2015; Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lan G The influence factors of HIV infection in a cohort of men who have sex with men in Nangning City [doctoral thesis]. Guangxi, China, Guangxi Medical University; 20115. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Golden MR, Brewer DD, Wood RW, Holmes K, Handsfield H. Association of Mathamphetamine use with HIV Among MSM Tested for HIV in an STD Clinic [abstract 0300] Abstract presented at: the 15th International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research; July 27-30, 2003; Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldstone S, Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection Among HIV-Seronegative Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Infect Dis 2011; 203: 66–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gust DA, Wiegand RE, Kretsinger K, et al. Circumcision status and HIV infection among MSM: reanalysis of a Phase III HIV vaccine clinical trial. AIDS 2010; 24: 1135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hiransuthikul A, Pattanachaiwit S, Teeratakulpisarn N, et al. Subsequent and recurrent STI among thai MSM and TG in test and treat cohort [abstract 863], Abstract presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 13–16, 2017; Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jameson DR, Celum CL, Manhart L, Menza TW, Golden MR. The association between lack of circumcision and HIV, HSV-2, and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37: 147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jozkowski K, Rosenberger JG, Schick V, Herbenick D, Novak DS, Reece M. Relations between circumcision status, sexually transmitted infection history, and HIV serostatus among a national sample of men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010; 24: 465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kreiss JK, Hopkins SG. The association between circumcision status and human immunodeficiency virus infection among homosexual men. J Infect Dis 1993; 168: 1404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lafferty WE, Hughes JP, Handsfield HH. Sexually transmitted disease in men who have sex with men: Acquisition of gonorrhea and nongonococcal urethritis by fellatio and implications for STD/HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis 1997; 24: 272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, et al. Lower risk of HIV infection among circumcised MSM: results from the Soweto Men’s Study [abstract MOPDC105], Abstract presented at: the 5th International AIDS Conference; July 19-22, 2009; Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto men’s study. AIDS and Behavior 2011; 15: 626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McDaid LM, Weiss HA, Hart GJ. Circumcision among men who have sex with men in Scotland: limited potential for HIV prevention. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86: 404–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Millett GA, Ding H, Lauby J, et al. Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 46: 643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mor Z, Kent CK, Kohn RP, Klausner JD. Declining rates in male circumcision amidst increasing evidence of its public health benefit. PLoS One 2007; 2: e861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oster AM, Wiegand RE, Sionean C, et al. Understanding disparities in HIV infection between black and white MSM in the United States. AIDS 2011; 25: 1103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kumta S, Setia M, Jerajani HR, Mathur MS, RaoKavi A, CP L. Men who have sex with men (MSM) and male-to-female transgender (TG) in Mumbai: a critical emerging risk group for HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STI) in India [abstract TuOrC1149]. Abstract presented at: XIV International AIDS Conference; July 7–12, 2002; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Setia MS, Lindan C, Jerajani HR, et al. Men who have sex with men and transgenders in Mumbai, India: an emerging risk group for STIs and HIV. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006; 72: 425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reisen CA, Zea MC, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT. Male circumcision and HIV status among Latino immigrant MSM in New York City. J LGBT Health Res 2007; 3: 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sanchez J, Lama JR, Peinado J, et al. High HIV and ulcerative sexually transmitted infection incidence estimates among men who have sex with men in Peru: awaiting for an effective preventive intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51 Suppl 1: S47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sánchez J, Sal y Rosas VG, Hughes JP, et al. Male Circumcision and Risk of HIV Acquisition among Men who have Sex with Men from the United States and Peru. AIDS 2011; 25: 519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tabet S, Sanchez J, Lama J, et al. HIV, syphilis and heterosexual bridging among Peruvian men who have sex with men. AIDS 2002; 16: 1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Mao L, et al. Circumcision and risk of HIV infection in Australian homosexual men. AIDS 2009; 23: 2347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Templeton DJ, Jin F, Prestage GP, et al. Circumcision and risk of sexually transmissible infections in a community-based cohort of HIV-negative homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. J Infect Dis 2009; 200: 1813–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thornton AC, Lattimore S, Delpech V, Weiss HA, Elford J. Circumcision among men who have sex with men in London, United Kingdom: an unlikely strategy for HIV prevention. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38: 928–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yunihastuti E, Phanuphak N, Somia A, et al. Safer sexual practice among known HIV-positive compared to HIV-negative/unknown status men who have sex with men in Bangkok, Bali and Jakarta [abstract THPE219]. Abstract presented at: The XIX International AIDS Conference; July 22-27, 2012; Washington, DC., USA. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zou H, Wu ZY, Yu JP, et al. Sexual Risk Behaviors and HIV Infection among Men Who Have Sex with Men Who Use the Internet in Beijing and Urumqi, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53 S81–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Whittles LK, Mitchell KM, Silhol R, Dimitrov DT, Boily MC. Global variation in the impact of male circumcision in preventing HIV among MSM. Topics in Antiviral Medicine 2016; 24: 459–60. [Google Scholar]

- 93.UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in high HIV prevalence settings: what can mathematical modelling contribute to informed decision making? PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tao J, Ruan Y, Yin L, et al. Sex with women among men who have sex with men in China: prevalence and sexual practices. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013; 27: 524–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smith AD, Tapsoba P, Peshu N, Sanders EJ, Jaffe HW. Men who have sex with men and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2009; 374: 416–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Palefsky J Human papillomavirus-related disease in people with HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009; 4: 52–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Larke N, Thomas SL, Dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA. Male circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 1375–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 1298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Auvert B, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Cutler E, et al. Effect of male circumcision on the prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus in young men: results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis 2009; 199: 14–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dinh MH, Fahrbach KM, Hope TJ. The role of the foreskin in male circumcision: an evidence-based review. Am J Reprod Immunol 2011; 65: 279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ficarra G, Carlos R. Syphilis: the renaissance of an old disease with oral implications. Head Neck Pathol 2009; 3: 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ruan Y, Qian HZ, Li D, et al. Willingness to Be Circumcised for Preventing HIV among Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009; 23: 315–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Abdulwahab-Ahmed A, Mungadi IA. Techniques of Male Circumcision. J Surg Tech Case Rep 2013; 5: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.