Abstract

Neutrophils are innate immune cells that constitute the first line of defense against invading pathogens. Due to this characteristic, they are exposed to diverse immunological environments wherein sources for nutrients are often limited. Recent advances in the field of immunometabolism revealed that neutrophils utilize diverse metabolic pathways in response to immunological challenges. In particular, neutrophils adopt specific metabolic pathways for modulating their effector functions in contrast to other immune cells, which undergo metabolic reprogramming to ensure differentiation into distinct cell subtypes. Therefore, neutrophils utilize different metabolic pathways not only to fulfill their energy requirements, but also to support specialized effector functions, such as neutrophil extracellular trap formation, ROS generation, chemotaxis, and degranulation. In this review, we discuss the basic metabolic pathways used by neutrophils and how these metabolic alterations play a critical role in their effector functions.

Keywords: Immunology, Innate immunity, Neutrophils, Metabolism, Immunometabolism

INTRODUCTION

Cells utilize diverse metabolic pathways for their growth, proliferation, survival, and even cell death. Catabolic reactions in metabolic pathways not only generate ATP, the major cellular energy source, but also fundamental metabolic intermediates. To achieve this, cells convert glucose into pyruvate through glycolysis, and pyruvate is further converted into acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA is then oxidized through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, generating GTP, NADH, and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2). Acetyl-CoA is also generated either from fatty acid oxidation (FAO) or from carbohydrate metabolism. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), a diversion pathway of glycolysis, generates NADPH and precursors for nucleotide synthesis. Thus, cells are able to utilize anabolic reactions in metabolic pathways to generate diverse intermediates for polypeptides, nucleic acids, proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids that they require for survival.

Immune cells are highly mobile cells; hence, they are exposed to various immunological environments wherein the availability of nutrients varies. Therefore, immune cells have a high functional plasticity, since they can reprogram diverse metabolic pathways according to the immunological environments they are exposed to. For example, proinflammatory M1 macrophages preferentially utilize the glycolytic pathway with broken TCA cycle to generate inflammatory mediators, whereas anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages utilize β-oxidation with intact TCA cycle to generate anti-inflammatory mediators (1). T cells also often reprogram their metabolic pathways to achieve differentiation into diverse subtypes, and each resulting subtype has a distinct metabolic signature (1,2).

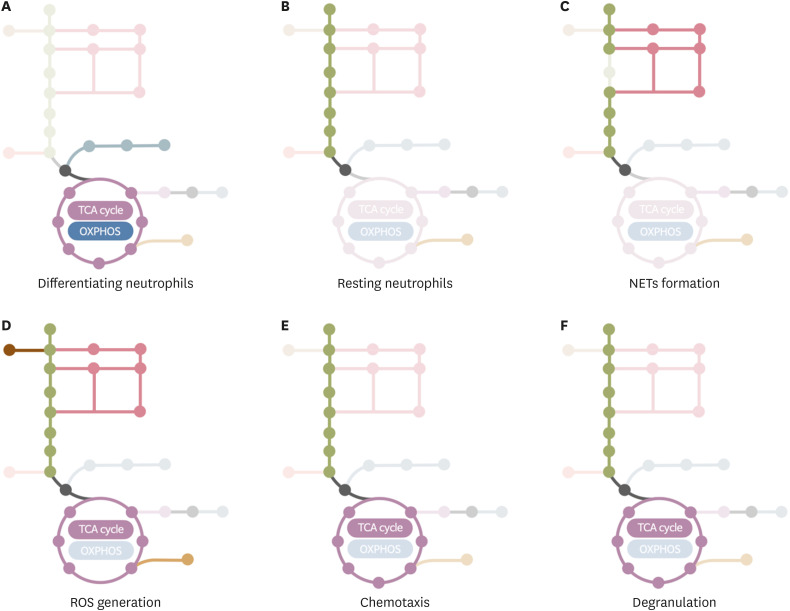

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in humans and participate in the innate immune response against invading pathogens. They are the first responders during inflammation and eliminate pathogens at infection sites. Because neutrophils are terminal differentiated cells with short life spans, earlier studies suggested that neutrophils were committed into simple metabolic pathways, such as glycolysis. However, recent advances in the immunometabolism field revealed that neutrophils use diverse metabolic pathways; reviewed in Kumar and Dikshit (Fig. 1) (3). Compared to other immune cells where metabolic reprogramming generally ensures differentiation into distinct subtypes, neutrophils modulate their metabolic pathways to execute different effector functions such as chemotaxis, generation of ROS, neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, and degranulation. In this review, we review the basic metabolic pathways used by neutrophils and further discuss the metabolic changes required for their effector functions.

Figure 1. Basic metabolic pathways in neutrophils. Glycolysis is the dominant metabolic pathway for basal energy production in the form of ATP in neutrophils. The PPP diverts intermediates of the glycolytic pathway to produce NADPH, which is oxidated during ROS generation. The FAO pathway is an important source of acetyl-CoA through breakdown of fatty acids. FAO is used by immature neutrophils such as differentiating neutrophils and c-kit+ tumor-infiltrating neutrophils. Although neutrophils are equipped with intact mitochondrial and TCA cycle, they hardly depend on mitochondrial respiration for energy production. Mitochondrial purinergic signaling is important for chemotaxis in neutrophils. Migrating neutrophils show condensed mitochondrial in the head and tail positions and the local release of ATP drives their chemotaxis. On the other hand, an intact TCA cycle ensures the generation of various inflammatory intermediates. FAS mediates de novo lipogenesis, including the production of membrane phospholipids that replenish decayed membranes during inflammation. Glutaminolysis convert glutamine into α-KG, supporting the TCA cycle. Although neutrophils utilize glutaminolysis during glucose-limiting conditions, the fate of metabolized glutamine has not been fully understood. Neutrophils also use stored glycogen for glycogenolysis under glucose-limiting condition and anaerobic glycolysis under low oxygen conditions.

α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; FBP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; 3PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; 6PGL, 6-phosphogluconolactonase; 6PG, 6-phosphogluconate; X5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; R5P, ribose-5-phosphate; OAA, oxaloacetate.

BASIC METABOLIC PATHWAYS IN NEUTROPHILS

Glycolysis

Glycolysis is a fundamental metabolic pathway for most immune cells. Most cells uptake extracellular glucose through glucose transporters (GLUTs) and the subsequent glycolytic process coverts glucose into pyruvate, generating a small amount of ATP and NADH. In normoxia, pyruvate is converted to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which is further oxidized through the TCA cycle. Alternatively, in anaerobic conditions, pyruvate is converted to lactate by LDH (4). Glycolysis also generates diverse intermediates that are processed by the PPP for nucleotide synthesis, by the serine biosynthetic pathway for amino acids, or by the TCA cycle for (1). Therefore, glycolysis is a dominant metabolism in most immune cells, including neutrophils, which also depend on glycolysis as source of ATP. Resting neutrophils express various GLUTs, such as GLUT1, GLUT3, and GLUT4. Activated neutrophils show increased surface expression of GLUTs (5,6), which is accompanied by an increase in the uptake of glucose (6,7). In fact, depletion of glucose totally shuts most effector functions of neutrophils (4,6,8,9). Moreover, neutrophils have relatively lower numbers of mitochondria than other immune cells (10) and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is considered to be dispensable for their energy production (11,12). Under glucose-deprived conditions, neutrophils rely on the breakdown of stored glycogen (glycogenolysis) as an alternative source of glucose (9) and phagocytosis depends on stored glycogen in neutrophils (7). Interestingly, in inflammatory conditions, neutrophils show a larger accumulation of glycogen than peripheral neutrophils (13). Therefore, glycolysis seems to be a dominant and essential metabolic pathway for neutrophils.

PPP

The PPP allows diversion of intermediates from the glycolytic pathway to generate NADPH for redox signaling, and nucleotides for DNA and RNA synthesis (1). PPP potentiates the generation of ROS in neutrophils by NADPH oxidase (NOX) through providing NADPH (8). On the other hand, the nonoxidative branch of the PPP supplies nucleotides for nucleic acid synthesis. Since neutrophils are short-lived cells, the requirements of additional production of nucleotides for DNA synthesis is questionable. Instead, neutrophils are equipped with high amounts of microRNAs that are needed for the fine tuning of gene expression through post-transcriptional regulation (14). Therefore, a detailed study on the role of the nonoxidative branch of PPP in neutrophils is still needed.

Mitochondria

Mitochondria are dispensable for energy production in mature neutrophils. Bioenergetic analysis showed that the basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) is relatively lower in neutrophils than in monocytes or lymphocytes and is unresponsive to mitochondrial respiratory inhibitors (11). Moreover, the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration did not affect the ATP generation in mature neutrophils (15). However, neutrophils express components of the OXPHOS complex (16) and exhibit a complex mitochondrial network (17). Moreover, mitochondrial membrane potential (∆Ψm) is detected in mature neutrophils (16,17) and metabolization studies using exogenous amino acids have shown the functional mitochondria in neutrophils (18). Overall, these studies suggest that neutrophils are equipped with intact mitochondria but do not utilize them for energy production. Interestingly, immature neutrophils depend on OXPHOS and FAO, have relatively higher numbers of mitochondria than mature neutrophils (10), and show an intact OCR activity (12). In contrast to mature neutrophils, immature neutrophils produce energy by degrading lipid droplets through lipophagy and by directing the resultant fatty acids to the TCA cycle and OXPHOS (19).

FAO

During differentiation, neutrophils are critically dependent on lipophagy-mediated FAO (19). Since mature neutrophils mainly utilize glycolysis for energy production, FAO is considered to exclusively mediate their effector functions. For example, oxidized lipopoprotein induce NETs formation (20) and tumor infiltrating c-kit+ neutrophils utilize mitochondrial FAO to support ROS generation (12). However, it is unclear whether FAO mediates the effects of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) during chemotaxis (21) and apoptosis (22) of neutrophils. Moreover, neutrophils with defective glucose and glutamine metabolism during hyperglycemia are suggested to activate compensatory FAO (23). Therefore, FAO is dispensable for energy production in mature neutrophils, but seems to mediate their effector functions.

Fatty acid synthesis (FAS)

Endogenous FAS mediates the de novo lipogenesis from precursors such as acetyl-CoA. A recent study showed that neutrophils utilize FAS to convert malonyl-CoA into fatty acids that are finally converted into membrane phospholipids (24). This study demonstrated that neutrophils utilize FAS to build membranes during differentiation or to replenish decayed membranes during inflammatory conditions. Previous studies also reported the influence of SCFAs on effector functions of neutrophils such as apoptosis (22), ROS generation (25), chemotaxis (26,27,28), and NETs formation (29,30). However, this influence depends on histone deacetylase inhibition (31), extracellular acidification (30,32), and specific receptors for SCFAs (25), rather than on the fatty acid metabolism.

METABOLISM OF ACTIVATED NEUTROPHILS

Energetics of neutrophils during differentiation

Hematopoietic stem cells preferentially use glycolysis for energy production, whereas committed progenitors utilize mitochondrial respiration (33,34). Neutrophils are generated from myeloid committed progenitors, the granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells (GMPs), through increasingly more mature differentiation stages: myeloblasts (MBs), promyelocytes (PMs), myelocytes (MCs), metamyelocytes (MMs), and band cells (BCs) (35). Abundant mitochondria are observed in immature neutrophils such as MBs and PMs, but their number is reduced in mature neutrophils (10). Immature neutrophils utilize OXPHOS for energetics (19). MBs have a relatively higher autophagic flux than other differentiating neutrophil subsets, such as MCs, MMs, and BCs, and induce lipophagy-mediated degradation of lipid droplets to generate free fatty acids. FAO further supports mitochondrial respiration during neutrophil differentiation. Indeed, defective autophagy arrests neutrophil differentiation at or after the GMP stage. Interestingly, subsets of immature c-kit+ neutrophils also rely on mitochondrial respiration for energy production (12). In particular, c-kit+ neutrophils residing in tumor environments have a higher OCR compared to peripheral c-kit− neutrophils and are sensitive to treatment with etomoxir, an inhibitor of FAO. Moreover, acute myeloblastic leukemias exhibit accumulation of granulocyte precursors, which engage into aerobic glycolysis (a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect) (36). In summary, committed neutrophil precursors shift their metabolic pathway from glycolysis to FAO-mediated mitochondrial respiration. Then, as neutrophils differentiate, mitochondrial respiration diminishes (Fig. 2A). Finally, mature neutrophils shift their metabolic pathway back to glycolysis (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Representation of the current knowledge on metabolic pathways in working neutrophils. (A) Immature neutrophils utilize FAO-mediated OXPHOS for energy production. (B) Mature neutrophils preferentially utilize glycolysis as source for energy production. (C) Neutrophils depend on glycolysis bypassing the PPP for NET formation. (D) Neutrophils utilize diverse metabolic pathways for ROS generation. Glycolysis provides ATP and the PPP pathway provides NAPDH, which are required for ROS generation. NADPH generated through mitochondrial glutaminolysis is involved in ROS production. In contrast, immature neutrophils utilize mitochondria for ROS generation. (E) Mitochondrial purinergic signaling in migrating neutrophils mediates the chemotaxis of neutrophils, whereas glycolysis provides ATP for chemotaxis. (F) Both glycolysis and mitochondrial ATP production are involved in degranulation of neutrophils.

Basal energetics of neutrophils

As previously mentioned, mature neutrophils preferentially utilize glycolysis for energetics (Fig. 2B) and the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration does not affect their effector functions (4,37). However, the inhibition of glycolysis markedly attenuates ATP production in resting neutrophils and the production of lactate increases according to available glucose concentration (4,9). Neutrophils often encounter harsh environments where glucose and oxygen are lowly available. In glucose-deprived environments, neutrophils use the glycogenolysis pathway (4), whereas under low oxygen conditions neutrophils might adopt glycolysis for energy production rather than oxygen-requiring mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 2).

NETs formation

NETs are extracellular structures composed of DNA, histones, and antimicrobial granules (38). Neutrophils release NETs in response to immunological stimulations such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites, and damage-associated molecular patterns to limit the dissemination of pathogens (39). Neutrophils mainly use glycolysis as energy source for NET formation. This is suggested by experiments showing that 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, a hexokinase inhibitor) inhibits NET formation induced by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and amyloid fibrils (AF) (6,8). Moreover, the depletion of glucose totally abolishes NET release (6,8) and, conversely, the addition of glucose is sufficient to sustain NET formation (8). PMA stimulation enhances GLUT-1 expression, leading to an increase in glucose uptake and in glycolysis (6). The stimulation of neutrophils with either PMA or ionomycin enhances the extracellular acidification rate and the LDH activity (40). Interestingly, the inhibition of PPP by 6-aminonicotinamide (6-AN, a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [G6PDH] inhibitor) also inhibits PMA- and AF-induced NETs formation (8). Additionally, the exposure of bovine neutrophils to lactate enhances NET formation (41) and the inhibition of either monocarboxylate transporter 1 or LDH affects the lactate-induced NET formation (41). Because LDH mediates the bidirectional conversion of pyruvate and lactate, this result suggests that neutrophils utilize lactate during NETs formation. Therefore, glycolysis bypassing the PPP comprises the major metabolic pathway underlying NET formation (Fig. 2C).

ROS generation

ROS generation is one of the most important mechanism for the bactericidal activity of neutrophils. The generation of superoxide by NOX is the rate-limiting step for ROS generation. NOX transports electrons from NADPH into the phagosome to generate superoxide and these superoxide radicals are further converted into various ROS. Indeed, patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a genetic defect in NOX, show a predisposition to bacterial and fungal infections. ROS generation results in an increase in the OCR, which masks the mitochondrial respiration-induced OCR (11).

Neutrophils mainly use the PPP for ROS generation. In fact, the inhibition of PPP by 6-AN attenuates high glucose-induced ROS generation in neutrophils in pregnant women (42). The oxidative phase of PPP reduces 2 molecules of NADP+ to NADPH using energy obtained from the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to ribulose 5-phosphate. Although the PPP provides the majority of NADPH, a substantial amount of NADPH is also obtained by glutaminolysis. Of note, the PMA treatment increases the OCR in human neutrophils and the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration does not affect PMA-induced OCR (11). PMA-stimulated neutrophils show an increase in the phosphorylation of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase, the limiting enzyme in glycolysis, and the inhibition of this enzyme decreases both the glycolysis rate and the NOX activity in neutrophils (43). Additionally, neutrophils isolated from patients with glycogen storage disease type Ib (GSD-Ib), a deficiency in glucose-6-phosphatase-β, showed impaired ROS generation (44).

In contrast, immature neutrophils were suggested to use mitochondrial respiration for ROS generation. As described earlier, immature neutrophils heavily rely on FAO-supported mitochondrial respiration to fulfill their energetic requirements. The inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG attenuates the early phase of the OCR, whereas the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration with rotenone and antimycin A inhibits the later phase of the OCR in tumor-infiltrating immature neutrophils stimulated with PMA (12). The combined treatment of 2-DG and etomoxir (a carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 inhibitor) completely inhibits the PMA-induced OCR in immature neutrophils (12). In contrast, in mature neutrophils, PMA-induced ROS generation is not affected by carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (11,17), suggesting a negligible role of mitochondria for ROS generation in mature neutrophils. Interestingly, exogenous α-ketoglutarate and pyruvate enhance ROS generation in neutrophils containing increased amounts of cellular intermediates such as glutamate (45,46).

Moreover, supplemental glutamine enhances ROS generation in human neutrophils (47). Glutaminolysis is an alternative pathway for provision of NADPH (48) and mitochondrial glutaminase is pivotal for glutamine metabolism (49). Because mitochondria in neutrophils are functionally intact (despite being dispensable for energy production) (17,50), neutrophils may alternatively use the mitochondrial glutaminolysis pathway for supplementing NADPH during ROS generation (Fig. 2D).

In summary, the PPP is the major metabolic pathway used by neutrophils for the generation of ROS but mitochondrial glutaminolysis seems to play an alternative role as an important NADPH supplementing pathway (Fig. 2D).

Chemotaxis

Neutrophils actively migrate into inflammatory foci to eliminate invading pathogens. Neutrophils recognize a gradient of chemoattractants, reorganize their cytoskeletons, and migrate toward chemoattractants. Various signaling molecules, such as small GTPases and PI3K, coordinate the migration of neutrophils through spatial control of the cytoskeleton (51). Mitochondria-derived purinergic signaling is important for neutrophil chemotaxis. For example, N-formyl-methyl-leucyl-phenylalanin (fMLP), a major chemoattractant for neutrophils, enhances the mitochondrial activity and ATP production at the front side of the migrating neutrophils (50,52). This release of ATP triggers the P2Y2 receptor resulting in pseudopod protrusion supported by actin polymerization. Mitochondria respiration is hardly involved in ATP generation in response to chemoattractants due to the inhibition of chemotaxis by the disruption of the mitochondrial potential but not due to the inhibition of ATP synthase (17). Moreover, the inhibition of mitochondrial complex I by metformin inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis (53) and iso-citrate dehydrogenase-deficient neutrophils show impaired chemotaxis (54).

Additionally, neutrophils use glycolysis as source of ATP for chemotaxis. Migrating neutrophils show increased uptake of glucose (7) and, in accordance, impaired chemotaxis is observed in G6PD-deficient neutrophils (44). Furthermore, the maximal dose of 2-DG completely inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, whereas the half-maximal dose of 2-DG paradoxically enhances neutrophil chemotaxis (55).

Overall, these results suggest that neutrophils mainly use purinergic signaling from the mitochondrial TCA cycle as source of chemotactic signals and glycolysis as an energy source for chemotaxis (Fig. 2E).

Degranulation

Neutrophils contain diverse antimicrobial molecules, such as peptides and proteases, in the form of stored granules. During differentiation in the bone marrow, neutrophils acquire and store these antimicrobial molecules into at least four kinds of granules: azurophil (primary) granules, specific (secondary) granules, gelatinase (tertiary) granules, and secretory vesicles (56). Because these molecules are highly toxic to microorganisms, they comprise an important non-oxidative resource with bactericidal functions. Upon sequestration of pathogens by phagocytosis, neutrophil granules fuse resulting in the formation of phagolysosomes and release antimicrobial molecules into these vesicles (57). This degranulation process comprises membrane fusion between granules and phagosomes and is mediated by membrane fusion-associated signals such as small GTPase, Ca2+, vesicle-associated membrane protein, syntaxin, and synatosomal-associated protein receptor (58).

A detailed understanding of how neutrophils produce energy to use during the degranulation process has not been attempted. However, 2-DG was shown to inhibit degranulation of azurophil (59), specific (60), and tertiary granules (55,60), in accordance with a role of glycolysis in the process. Furthermore, neutrophils isolated from CGD patients exhibit exacerbated degranulation in response to stimulation with fMLP and PMA (61), suggesting that neutrophils rarely use the PPP for degranulation. Interestingly, mitochondrial functions are also involved in degranulation of neutrophils. In particular, the inhibition of mitochondrial ATP production prevents the degranulation process (62) and the purinergic signaling can mediate degranulation, among other effector functions (63). In summary, neutrophils utilize both glycolysis and mitochondrial TCA cycle to fuel degranulation (Fig. 2F).

Metabolism of neutrophils during metabolic disorders

Metabolic adaptation of neutrophils during pathological conditions is reviewed in an excellent article (3). Therefore, we will briefly review neutrophil metabolism during metabolic disorders. Neutrophils exhibit defective functions in genetic disorders on metabolism. The deficiency of G6PDH, a key enzyme for diversion of glycolytic pathway into PPP, results in defective PPP with reduced production of NADPH. Neutrophils isolated from patients with G6PDH deficiency showed defective PPP with reduced respiratory burst (64) and NET formation (65). Neutrophils isolated from patients with GSD-1b, a deficiency in glucose-6-phosphate transporter, also showed defective production of ATP with impaired ROS generation and phagocytosis (44). In contrast, neutrophils exhibit metabolic reprogramming during diabetes. Most effector functions of neutrophils including ROS generation, NET formation, bactericidal activity, and chemotaxis, are dysregulated in patients with diabetes (66,67,68,69,70). Since neutrophils are exposed to hyperglycemia during diabetes, neutrophils isolated from diabetic rats exhibit the decreased activity of G6PDH with the defective PPP and reduced ROS generation (23). Therefore, a compensatory FAO utilization by neutrophils has been suggested. However, the detailed study regarding metabolic adaptation of neutrophils during diabetes has not been fully elucidated yet.

DISCUSSION

Despite the recent advances in the field of immunometabolism, the metabolism of neutrophils is not fully understood. Earlier studies revealed that neutrophils mainly use glucose as source for their metabolic processes; however, emerging evidence shows that neutrophils also use other nutrients such as amino-acids, carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids for energy production. Neutrophils are often exposed to various immunological environments where nutrients are limited. Therefore, they must adapt diverse metabolic pathways for diverse functions in response to the required immunological needs. Moreover, recent studies suggest that neutrophils undergo metabolic adaptation under diverse disease conditions. Further studies using dedicated techniques, such as metabolic flux assay and metabolomics, might be useful for the complete understanding of the neutrophil metabolism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Biomedical Research Institute Grant, Kyungpook National University Hospital (2018) and by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant No. HI15C0001).

Abbreviations

- 2-DG

2-deoxyglucose

- 6-AN

6-aminonicotinamide

- AF

amyloid fibrils

- BC

band cell

- CGD

chronic granulomatous disease

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- GSD-Ib

glycogen storage disease type Ib

- FADH2

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- FAS

fatty acid synthesis

- fMLP

N-formyl-methyl-leucyl-phenylalanin

- GMP

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cell

- MB

myeloblast

- MC

myelocyte

- MM

metamyelocyte

- NET

neutrophil extracellular trap

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PM

promyelocyte

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- SCFA

short chain fatty acid

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Jeon JH, Hong CW.

- Funding acquisition: Jeon JH, Hong CW.

- Investigation: Jeon JH, Hong CW, Kim EY.

- Writing - original draft: Jeon JH, Hong CW.

- Writing - review & editing: Lee JM.

References

- 1.O'Neill LA, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:553–565. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Bourgeois T, Strauss L, Aksoylar HI, Daneshmandi S, Seth P, Patsoukis N, Boussiotis VA. Targeting T cell metabolism for improvement of cancer immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:237. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Dikshit M. Metabolic insight of neutrophils in health and disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2099. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borregaard N, Herlin T. Energy metabolism of human neutrophils during phagocytosis. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:550–557. doi: 10.1172/JCI110647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maratou E, Dimitriadis G, Kollias A, Boutati E, Lambadiari V, Mitrou P, Raptis SA. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez-Espinosa O, Rojas-Espinosa O, Moreno-Altamirano MM, López-Villegas EO, Sánchez-García FJ. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology. 2015;145:213–224. doi: 10.1111/imm.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisdorf DJ, Craddock PR, Jacob HS. Granulocytes utilize different energy sources for movement and phagocytosis. Inflammation. 1982;6:245–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00916406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azevedo EP, Rochael NC, Guimarães-Costa AB, de Souza-Vieira TS, Ganilho J, Saraiva EM, Palhano FL, Foguel D. A metabolic shift toward pentose phosphate pathway is necessary for amyloid fibril- and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced neutrophil extracellular trap (net) formation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22174–22183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.640094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sbarra AJ, Karnovsky ML. The biochemical basis of phagocytosis. I. Metabolic changes during the ingestion of particles by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:1355–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bainton DF, Ullyot JL, Farquhar MG. The development of neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes in human bone marrow. J Exp Med. 1971;134:907–934. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chacko BK, Kramer PA, Ravi S, Johnson MS, Hardy RW, Ballinger SW, Darley-Usmar VM. Methods for defining distinct bioenergetic profiles in platelets, lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils, and the oxidative burst from human blood. Lab Invest. 2013;93:690–700. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice CM, Davies LC, Subleski JJ, Maio N, Gonzalez-Cotto M, Andrews C, Patel NL, Palmieri EM, Weiss JM, Lee JM, et al. Tumour-elicited neutrophils engage mitochondrial metabolism to circumvent nutrient limitations and maintain immune suppression. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5099. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07505-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson JM, Karnovsky ML, Karnovsky MJ. Glycogen accumulation in polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and other intracellular alterations that occur during inflammation. J Cell Biol. 1982;95:933–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurol T, Zhou W, Deng Q. MicroRNAs in neutrophils: potential next generation therapeutics for inflammatory ailments. Immunol Rev. 2016;273:29–47. doi: 10.1111/imr.12450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maianski NA, Geissler J, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Roos D, Kuijpers TW. Functional characterization of mitochondria in neutrophils: a role restricted to apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:143–153. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Raam BJ, Sluiter W, de Wit E, Roos D, Verhoeven AJ, Kuijpers TW. Mitochondrial membrane potential in human neutrophils is maintained by complex III activity in the absence of supercomplex organisation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:1964–1972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karinch AM, Pan M, Lin CM, Strange R, Souba WW. Glutamine metabolism in sepsis and infection. J Nutr. 2001;131:2535S–2538S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.9.2535S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riffelmacher T, Clarke A, Richter FC, Stranks A, Pandey S, Danielli S, Hublitz P, Yu Z, Johnson E, Schwerd T, et al. Autophagy-dependent generation of free fatty acids is critical for normal neutrophil differentiation. Immunity. 2017;47:466–480.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awasthi D, Nagarkoti S, Kumar A, Dubey M, Singh AK, Pathak P, Chandra T, Barthwal MK, Dikshit M. Oxidized LDL induced extracellular trap formation in human neutrophils via TLR-PKC-IRAK-MAPK and NADPH-oxidase activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;93:190–203. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez-Curto E, Milligan G. Metabolism meets immunity: the role of free fatty acid receptors in the immune system. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;114:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aoyama M, Kotani J, Usami M. Butyrate and propionate induced activated or non-activated neutrophil apoptosis via HDAC inhibitor activity but without activating GPR-41/GPR-43 pathways. Nutrition. 2010;26:653–661. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alba-Loureiro TC, Hirabara SM, Mendonça JR, Curi R, Pithon-Curi TC. Diabetes causes marked changes in function and metabolism of rat neutrophils. J Endocrinol. 2006;188:295–303. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lodhi IJ, Wei X, Yin L, Feng C, Adak S, Abou-Ezzi G, Hsu FF, Link DC, Semenkovich CF. Peroxisomal lipid synthesis regulates inflammation by sustaining neutrophil membrane phospholipid composition and viability. Cell Metab. 2015;21:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vinolo MA, Hatanaka E, Lambertucci RH, Newsholme P, Curi R. Effects of short chain fatty acids on effector mechanisms of neutrophils. Cell Biochem Funct. 2009;27:48–55. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Böcker U, Nebe T, Herweck F, Holt L, Panja A, Jobin C, Rossol S, B Sartor R, Singer MV. Butyrate modulates intestinal epithelial cell-mediated neutrophil migration. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinolo MA, Ferguson GJ, Kulkarni S, Damoulakis G, Anderson K, Bohlooly-Y M, Stephens L, Hawkins PT, Curi R. SCFAs induce mouse neutrophil chemotaxis through the GPR43 receptor. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Hatanaka E, Hebeda CB, Farsky SH, Curi R. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate the migration of neutrophils to inflammatory sites. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;117:331–338. doi: 10.1042/CS20080642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohbuchi A, Kono M, Takenokuchi M, Imoto S, Saigo K. Acetate moderately attenuates the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood Res. 2018;53:177–180. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behnen M, Möller S, Brozek A, Klinger M, Laskay T. Extracellular acidification inhibits the ROS-dependent formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol. 2017;8:184. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni YF, Wang J, Yan XL, Tian F, Zhao JB, Wang YJ, Jiang T. Histone deacetylase inhibitor, butyrate, attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Respir Res. 2010;11:33. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotstein OD, Vittorini T, Kao J, McBurney MI, Nasmith PE, Grinstein S. A soluble Bacteroides by-product impairs phagocytic killing of Escherichia coli by neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1989;57:745–753. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.3.745-753.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, Deberardinis RJ, Mahmoud AI, Olson EN, Schneider JW, Zhang CC, Sadek HA. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takubo K, Nagamatsu G, Kobayashi CI, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Kobayashi H, Ikeda E, Goda N, Rahimi Y, Johnson RS, Soga T, et al. Regulation of glycolysis by Pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:431–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Y, Nakada D. Cell intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of leukemia cell metabolism. Int J Hematol. 2016;103:607–616. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-1958-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reiss M, Roos D. Differences in oxygen metabolism of phagocytosing monocytes and neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:480–488. doi: 10.1172/JCI108959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:134–147. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Awasthi D, Nagarkoti S, Sadaf S, Chandra T, Kumar S, Dikshit M. Glycolysis dependent lactate formation in neutrophils: a metabolic link between NOX-dependent and independent NETosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:165542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.165542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alarcón P, Manosalva C, Conejeros I, Carretta MD, Muñoz-Caro T, Silva LM, Taubert A, Hermosilla C, Hidalgo MA, Burgos RA. D(-) lactic acid-induced adhesion of bovine neutrophils onto endothelial cells is dependent on neutrophils extracellular traps formation and cd11b expression. Front Immunol. 2017;8:975. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petty HR, Kindzelskii AL, Chaiworapongsa T, Petty AR, Romero R. Oxidant release is dramatically increased by elevated glucose concentrations in neutrophils from pregnant women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005;18:397–404. doi: 10.1080/14767050500361679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baillet A, Hograindleur MA, El Benna J, Grichine A, Berthier S, Morel F, Paclet MH. Unexpected function of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase in supporting hyperglycolysis in stimulated neutrophils: key role of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase. FASEB J. 2017;31:663–673. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600720R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jun HS, Weinstein DA, Lee YM, Mansfield BC, Chou JY. Molecular mechanisms of neutrophil dysfunction in glycogen storage disease type Ib. Blood. 2014;123:2843–2853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-502435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mühling J, Tussing F, Nickolaus KA, Matejec R, Henrich M, Harbach H, Wolff M, Weismüller K, Engel J, Welters ID, et al. Effects of alpha-ketoglutarate on neutrophil intracellular amino and alpha-keto acid profiles and ROS production. Amino Acids. 2010;38:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0224-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathioudakis D, Engel J, Welters ID, Dehne MG, Matejec R, Harbach H, Henrich M, Schwandner T, Fuchs M, Weismüller K, et al. Pyruvate: immunonutritional effects on neutrophil intracellular amino or alpha-keto acid profiles and reactive oxygen species production. Amino Acids. 2011;40:1077–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0731-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Furukawa S, Saito H, Inoue T, Matsuda T, Fukatsu K, Han I, Ikeda S, Hidemura A. Supplemental glutamine augments phagocytosis and reactive oxygen intermediate production by neutrophils and monocytes from postoperative patients in vitro. Nutrition. 2000;16:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, Thompson CB. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, Lee YS, Kita K, Ochi T, Zeller KI, De Marzo AM, Van Eyk JE, Mendell JT, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bao Y, Ledderose C, Graf AF, Brix B, Birsak T, Lee A, Zhang J, Junger WG. mTOR and differential activation of mitochondria orchestrate neutrophil chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:1153–1164. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201503066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gambardella L, Vermeren S. Molecular players in neutrophil chemotaxis--focus on PI3K and small GTPases. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:603–612. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tay HM, Dalan R, Li KH, Boehm BO, Hou HW. A novel microdevice for rapid neutrophil purification and phenotyping in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Small. 2018;14:1702832. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amankulor NM, Kim Y, Arora S, Kargl J, Szulzewsky F, Hanke M, Margineantu DH, Rao A, Bolouri H, Delrow J, et al. Mutant IDH1 regulates the tumor-associated immune system in gliomas. Genes Dev. 2017;31:774–786. doi: 10.1101/gad.294991.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lane TA, Lamkin GE. A reassessment of the energy requirements for neutrophil migration: adenosine triphosphate depletion enhances chemotaxis. Blood. 1984;64:986–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faurschou M, Borregaard N. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pham CT. Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:541–550. doi: 10.1038/nri1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lacy P. Mechanisms of degranulation in neutrophils. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2006;2:98–108. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-2-3-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith RJ, Iden SS, Bowman BJ. Activation of the human neutrophil secretory process with 5(S),12(R)-dihydroxy-6,14-cis-8,10-trans-eicosatetraenoic acid. Inflammation. 1984;8:365–384. doi: 10.1007/BF00918213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith RJ, Bowman BJ, Iden SS, Kolaja GJ, Wiser SK. Biochemical, metabolic and morphological characteristics of human neutrophil activation with pepstatin A. Immunology. 1983;49:367–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pak V, Budikhina A, Pashenkov M, Pinegin B. Neutrophil activity in chronic granulomatous disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:69–74. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bao Y, Ledderose C, Seier T, Graf AF, Brix B, Chong E, Junger WG. Mitochondria regulate neutrophil activation by generating ATP for autocrine purinergic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26794–26803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.572495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang X, Chen D. Purinergic regulation of neutrophil function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:399. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolach B, Ashkenazi M, Grossmann R, Gavrieli R, Friedman Z, Bashan N, Roos D. Diurnal fluctuation of leukocyte G6PD activity. A possible explanation for the normal neutrophil bactericidal activity and the low incidence of pyogenic infections in patients with severe G6PD deficiency in Israel. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:807–813. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000120680.47846.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siler U, Romao S, Tejera E, Pastukhov O, Kuzmenko E, Valencia RG, Meda Spaccamela V, Belohradsky BH, Speer O, Schmugge M, et al. Severe glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency leads to susceptibility to infection and absent netosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:212–219.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 1997;14:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199701)14:1<29::AID-DIA300>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Omori K, Ohira T, Uchida Y, Ayilavarapu S, Batista EL, Jr, Yagi M, Iwata T, Liu H, Hasturk H, Kantarci A, et al. Priming of neutrophil oxidative burst in diabetes requires preassembly of the NADPH oxidase. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:292–301. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1207832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stegenga ME, van der Crabben SN, Blümer RM, Levi M, Meijers JC, Serlie MJ, Tanck MW, Sauerwein HP, van der Poll T. Hyperglycemia enhances coagulation and reduces neutrophil degranulation, whereas hyperinsulinemia inhibits fibrinolysis during human endotoxemia. Blood. 2008;112:82–89. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-121723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong SL, Demers M, Martinod K, Gallant M, Wang Y, Goldfine AB, Kahn CR, Wagner DD. Diabetes primes neutrophils to undergo NETosis, which impairs wound healing. Nat Med. 2015;21:815–819. doi: 10.1038/nm.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mowat A, Baum J. Chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:621–627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197103252841201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]