Abstract

Estrogen receptor positive breast cancer (ER+ BC) is the most common form of breast carcinoma accounting for approximately 70% of all diagnoses. Although ER-targeted therapies have improved survival outcomes for this BC subtype, a significant proportion of patients will ultimately develop resistance to these clinical interventions, resulting in disease recurrence. Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1), an enzyme within the serine synthetic pathway (SSP), has been previously implicated in endocrine resistance. Therefore, we determined whether expression of SSP enzymes, PSAT1 or phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), affects the response of ER+ BC to 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) treatment. To investigate a clinical correlation between PSAT1, PHGDH, and endocrine resistance, we examined microarray data from ER+ patients who received tamoxifen as the sole endocrine therapy. We confirmed that higher PSAT1 and PHGDH expression correlates negatively with poorer outcomes in tamoxifen treated ER+ BC patients. Next, we found that SSP enzyme expression and serine synthesis were elevated in tamoxifen-resistant compared to tamoxifen-sensitive ER+ BC cells in vitro. To determine relevance to endocrine sensitivity, we modified the expression of either PSAT1 or PHGDH in each cell type. Overexpression of PSAT1 in tamoxifen-sensitive MCF-7 cells diminished 4-OHT inhibition on cell proliferation. Conversely, silencing of either PSAT1 or PHGDH resulted in greater sensitivity to 4-OHT treatment in LCC9 tamoxifen-resistant cells. Likewise, the combination of a PHGDH inhibitor with 4-OHT decreased LCC9 cell proliferation. Collectively, these results suggest that overexpression of serine synthetic pathway enzymes contribute to tamoxifen resistance in ER+ BC, which can be targeted as a novel combinatorial treatment option.

Keywords: estrogen receptor positive breast cancer, phosphoserine aminotransferase 1, serine synthesis, endocrine resistance, tamoxifen

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer that afflicts US women (Ferlay et al., 2010). Importantly, breast cancer is not a singular disease, but is characterized by several different histological and molecular subtypes (Perou et al., 2000, Rouzier et al., 2005). Estrogen receptor α (ERα, henceforth ER) positive breast cancer (ER+BC) is the most common breast cancer subtype and it accounts for 70% of all breast cancer cases (De Marchi et al., 2016, Hammond et al., 2010). Incidence rates of ER+BC are influenced by many factors, including ethnicity and geopgraphical location (Yip and Rhodes, 2014). ER+ breast tumors are initially driven by estrogen activation of ER, which in turn, transcriptionally promotes induction of pro-proliferative/pro-oncogenic cascades (Bai and Gust, 2009). As these tumors rely upon this estrogen-driven growth, therapies that target the estrogen signaling pathway are a successful treatment option for patients with much of the decline in breast cancer mortality being credited to their success (De Marchi et al., 2016, Hammond et al., 2010).

All endocrine therapies target estrogen signaling through different mechanisms. The first clinical endocrine therapy, tamoxifen, was originally classified as an antiestrogen because it functions as an estrogen antagonist of ER in the breast (Fisher et al., 1983, Fisher et al., 1981); however, in other tissues it has estrogen agonist activities (Bai and Gust, 2009). Thus, tamoxifen was classified as a selective ER modulator (SERM). The established mechanism of tamoxifen in the breast is by competition with endogenous estrogens for binding ERα that results in the inhibition of the estrogen-driven, pro-proliferative transcription program (Robertson, 2001, Sporn MB, 2003). In addition to binding to ER, tamoxifen has also been demonstrated to activate G-protein-coupled ER (GPER1, also called GPR30 and GPER) (Gaudet et al., 2015).

Despite numerous effective therapeutic options against ER+BC that lead to better patient outcomes, significant clinical hurdles remain in managing ER+BC (Clarke et al., 2015). These largely stem from resistance to endocrine therapies, which can be classified as either innate or acquired resistance. Innate, or de novo, resistance relates to patients whose carcinomas lack ER and who have no initial response to endocrine therapy (Clarke et al., 2015). Acquired resistance includes patients that initially respond to endocrine therapy but then experience disease recurrence or progression (Clarke et al., 2015). Clinically, endocrine resistance affects between 10% and 15% of all patients within five years of diagnosis (Dowsett et al., 2010). By 15 years following diagnosis, it is estimated that 30% of ER+BC patients will become resistant to endocrine therapies (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative, 2005).

With this propensity for endocrine resistance, there is an important need to identify factors that may promote loss of therapeutic response, including alterations in genes responsible for proliferation, cell survival, unfolded protein response, as well as epigenetic and metabolic regulators; all of which have been implicated in mechanisms for antiestrogen resistance. Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) has previously been clinically linked to resistance to endocrine therapy (Martens et al., 2005). PSAT1, along with phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) and phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH), comprise the serine synthetic pathway (SSP). PSAT1 has been implicated in different cancer types as contributing to proliferation, resistance, metastasis and has been implicated in breast cancer resistance to tamoxifen therapy (De Marchi et al., 2017, Gao et al., 2017, Liao et al., 2016, Liu et al., 2016, Sun C, 2018, Yan S, 2015, Yang et al., 2015, Martens et al., 2005). In these reports, PSAT1 transcript levels were found to correlate with poorer progression-free survival in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen (Martens et al., 2005). This was later confirmed at the protein level and this study also suggested a putative increase in PHGDH expression in tamoxifen insensitive breast cancer (De Marchi et al., 2017), although this was not experimentally verified.

In this report, we examined the relevance of PSAT1 and PHGDH in tamoxifen-resistant ER+BC. Using clinical cohorts, we confirmed a negative correlation of PSAT1 and PHGDH expression with poorer progression free survival in tamoxifen-treated breast cancer patients. In addition, using cellular models of endocrine resistance in vitro, we discovered increased expression and activity of the serine synthetic pathway while manipulation of enzyme levels or pharmacological inhibition altered tamoxifen responsiveness in either endocrine- sensitive or resistant breast cancer cells. Together, these new experimental findings verify that enhanced SSP activity contributes to tamoxifen resistance in ER+ breast cancer.

Methods and Materials

Chemicals

(Z)-4-Hydroxytamoxifen was obtained from Sigma (H7904) and was dissolved in 100% pure Ethyl Alcohol (Sigma – E7023). Concentrated stock solutions were prepared, aliquoted and stored at −20°C for a period of 30 days. Diluted working stocks were prepared fresh for each application. PKUMDL-WQ-2201 was purchased from Sigma (SML1965) and was dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Cell Culture

MCF-7 cells were purchased from ATCC. LCC9 and LY2 breast cancer cells were generously provided by Dr. Robert Clarke, Georgetown University Medical Center (Bronzert, 1985, Brunner et al., 1997). LCC9 and LY2 breast cancer cells are stable, endocrine resistant MCF-7 variants that were selected through prolonged exposure to specific antiestrogens, tamoxifen and L117018, a precursor to raloxifene, respectively. Both the LCC9 and LY2 cell lines are resistant to tamoxifen as well as other antiestrogens such as LY117018 and fulvestrant (Bronzert, 1985, Brunner et al., 1997). The LCC9 cell line expresses ERα at similar levels to the parental MCF-7 line (Brunner et al., 1997) while the LY2 cell line has slightly less ERα expression when compared to the parental MCF-7 line (Bronzert, 1985). All cells were cultured in IMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and gentamicin or 1% Pen/Strep and incubated at 37° in 5% CO2.

Plasmid Construction and Transfections

Human PSAT1 was generated from cDNA prepared from the LCC9 cell line. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Promega) and 1μg of RNA was used to produce cDNA using the reverse transcriptase kit (Thermo) with random primers. Primers homologous to the 5’ and 3’ ends of the mature RNA encoding for PSAT1 were adapted to include restriction sites for ECOR1 (5’) and BAMH1 (3’). Polymerase chain reactions were performed to amplify PSAT1 from LCC9 cDNA preparation. PCR products were separated via gel electrophoresis and bands corresponding to the correct PCR product were excised and purified. PSAT1 fragments underwent restriction digest with ECOR1 and BAMH1 and then ligated into the pcDNA3 vector that was similarly digested. Ligations were then transformed and grown on LB agar plates with ampicillin. Isolated colonies were cultured in LB broth and ampicillin for 24 hours and plasmids were isolated via the Qiagen Miniprep kits. Plasmids, encoding either PSAT1 gene or empty vector were verified by sequencing. Plasmids were then transfected into the MCF-7 cell line using the Polyplus jetPRIME reagent according to manufacturer’s protocol and clonal selection for PSAT1 expression was performed using geneticin.

siRNA and shRNA Transfections

PSAT1 shRNA and Control shRNA were purchased from Sigma. ShRNAs were transfected into LCC9 cells using the Polyplus jetPRIME reagent according to manufacturer’s protocol. Clonal selection for gene silencing was performed using puromycin. The sequences for the shRNA and siRNA species are as follows: PSAT1 shRNA: 5’-CCGGGCACTCAGTGTTGTTAGAGATCTCGAGATCTCTAACAACACTGAGTGCTTTTTG-3’, Control shRNA: 5’- CCGGCAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAACTCGAGTTGGTGCTCTTCATCTTGTTGTTTTT-3’, PHGDH RNAi: 5’-CGACAGGUUGCUGAAUGA-3’, non-targeting pool RNAis: 5’-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3’, 5’-UGGUUUACAUGUUGUGUA-3’, 5’-UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCUGA-3’, 5’-UGGUUUACAUGUUUUCCUA-3’.

Immunoblot Assays

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in IP Lysis Buffer (Pierce) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T and subsequently probed with 1:1000-fold dilution of anti-PSAT1 (Proteintech, 10501–1-AP) or anti-PHGDH (Sigma HPA021241) antibodies for 16 hours at 4°. Washed membranes were then incubated with 1:5000 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Protein detection was done by exposure to ECL Prime chemiluminescent reagent (GE Healthcare). Protein loading was assessed using anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, A2228). Densitometry was performed via ImageJ.

Stable Isotype Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM)

MCF7 or LY2 cells were cultured in glucose-free or glutamine-free IMEM supplemented with 5% dialyzed serum and 1g/L 13C6 – glucose (Sigma) or 4mM 13C5,15N2-glutamine, respectively, for 48 hours. Metabolism was quenched via exposure to cold acetonitrile and cell metabolites were extracted using an acetonitrile/chloroform/H2O mixture as previously described (Lane et al., 2017). Polar metabolites were subsequently lyophilized and metabolic data acquired through Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) was recorded at the Resource Center for Stable Isotype Resolved Metabolomics Core facility at the University of Kentucky.

Treatments and Response

For genetic suppression studies, cells were treated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) for a period of four days (Astruc et al., 1995). Treatment response was measured by FluoReporter Blue Fluorometric dsDNA Quantitation Kit (Molecular Probes F-2962). In brief, cells were plated at 5,000 (MCF-7) or 2,500 (LCC9) cells per well on day 0 in complete medium. Twenty-four hours post-seeding, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 4-OHT for 96 hours. Plates were then collected and analyzed according to manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence counts were converted to total cell number by standard curve using known plated cell numbers. Treatment responses to 4-OHT were calculated by percent decrease compared to the vehicle control.

For PHGDH inhibitor studies, LCC9 cells were seeded in quadruplicate in 96-well plates (3,000 cells/well) and treated with DMSO (vehicle control), PKUMDL-WQ-2201 (0.1–100 μM), 4-OHT (100 nM or 1 μM) alone or in combination, for 5 days with medium/treatment change every 48 h. Cell proliferation or cell viability was measured according to the manufacturer’s directions using the FluoReporter kit or MTT assay (Promega G4000), respectively.

Quantitative-Real Time Polymerase-Chain Reaction

MCF-7 or LCC9 cells were collected and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). One microgram of RNA was converted to cDNA using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (appliedbiosystems) according to the manufacture’s protocol. Samples were then analyzed for qPCR via the TaqMan Fast Advanced (appliedbiosystems) system with human probes for PSAT1 (Hs00795278_mH), PHGDH (Hs00198333_m1), and ACTB (Hs01060665_g1).

Kaplan Meier Analysis

Retrospective analysis of specific gene expression on patient survival was performed by Kaplan-Meier analysis on de-identified patient clinical data obtained from either an IRB-approved institutional biorepository (Wittliff et al., 2008) or within the online database KM Plotter (kmplot.com) (Mihaly et al., 2013). Correlation of PSAT1 expression against relapse free survival (RFS) was performed using a microarray dataset acquired from laser-capture-microdissection (LCM) procured breast carcinoma cells from TAM treated ER+ BC patients. These specimens were extensively validated for active ER and progesterone receptor (PR) as previously described (Andres and Wittliff, 2012, Wittliff, 2010, Wittliff et al., 1998). In addition, analysis of both PSAT1 and PHGDH gene expression on survival outcomes in Tamoxifen treated ER+ BC patients was performed using the publically available KM Plotter database (Gyorffy et al., 2010). The hazard ratio (HR) with 95 % confidence intervals and the logrank p value are indicated. Both PSAT1 and PHGDH expression were similarly analyzed against the KM plotter database. Differences in patient number is postulated to be due to the selective availability of PHGHD expression in certain gene sets included in the KM plotter database.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance for all studies was evaluated by ANOVA with multiple comparisons or with unpaired student t-test using Graph Pad Prism software. For each experimental condition, p values and number of replicates are provided within their respective figure legends.

Results

Clinical relevance of PSAT1 in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen

It has been reported previously that PSAT1 transcript and protein levels correlate with poorer progression-free survival in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen (De Marchi et al., 2017, Martens et al., 2005). We first validated these reports using a unique dataset of microarray analyses of pure populations of breast carcinoma cells isolated by laser-capture micro-dissection using primary carcinomas obtained from patient specimens through the Hormone Receptor Laboratory at the University of Louisville (Andres et al., 2013, Wittliff et al., 2008). This was followed up using transcriptomic data from individuals within the KM Plotter database (Mihaly et al., 2013). All patients from both cohorts presented with ER+BC and were treated with tamoxifen as the sole endocrine therapy. In agreement with previous findings, analyses of each patient population revealed that elevated expression of PSAT1 correlated with decreased disease-free survival (Figure 1A) or relapse-free survival (Figure 1B). Together, these results suggest that PSAT1 may be associated with tamoxifen resistance in ER+BC patients.

Figure 1: Clinical relevance of PSAT1 in Tamoxifen treated ER+BC.

a) Relapse-free survival (RFS) of ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen stratified by above (n=33) or below (n=32) the median PSAT1 expression. Retrospective Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed from microarray data on institutionally collected de-identified laser captured micro-dissected ER+ breast carcinomas from patients treated with tamoxifen. b) Kaplan-Meier analysis of patient outcomes was done using KM Plotter database. RFS of ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen stratified by low (n=73) or high (n=37) PSAT1 expression. Shown are the hazard ratios (HR) and logrank P values for both analyses.

Manipulation of PSAT1 expression alters sensitivity to tamoxifen therapy

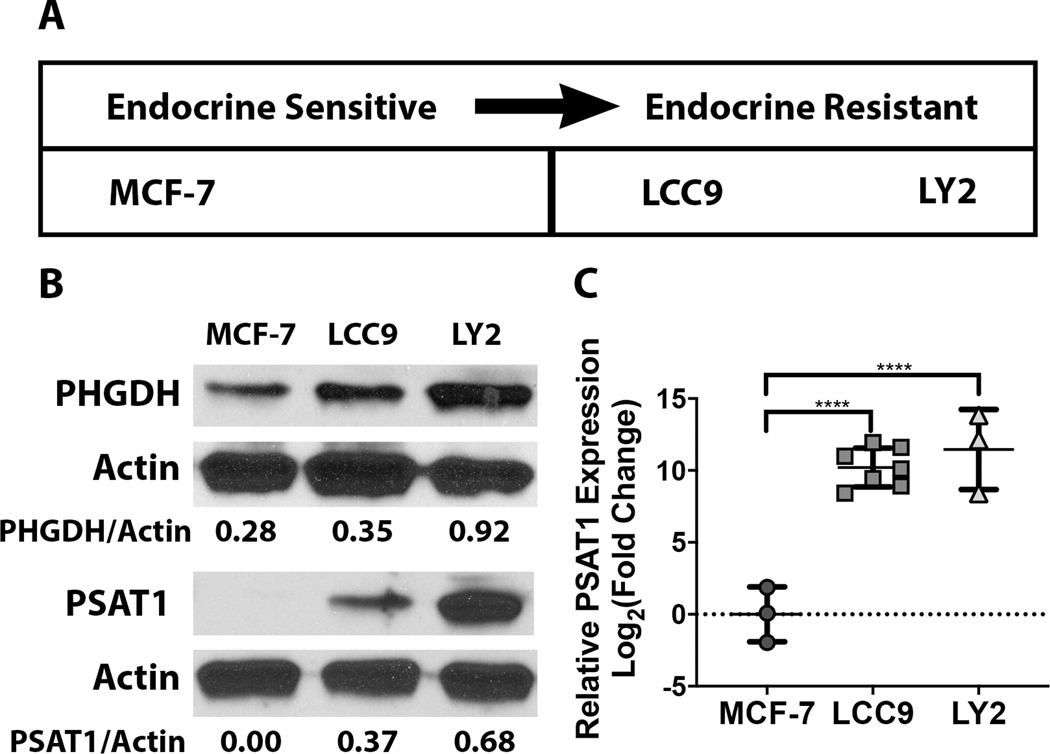

Prior studies have established in vitro models that have been used to investigate the mechanisms driving endocrine resistance in ER+ breast cancer (Brunner et al., 1997). In particular, one comparative model system utilizes the sensitive MCF-7 ER+ cell line and its tamoxifen-resistant derivatives. These resistant lines were generated through extended exposure of parental MCF-7 cells to increasing concentrations of endocrine therapies (Bronzert, 1985, Brunner et al., 1997) (Figure 2A). We initially examined whether expression of serine synthetic enzymes were altered between the tamoxifen-sensitive (MCF-7) or resistant cells (LCC9 and LY2). We found that expression of both PHGDH and PSAT1 are greatly increased in the LCC9 and LY2 compared to the MCF-7 cells (Figure 2B). Notably, while MCF-7 cells exhibited some expression of PHGDH, PSAT1 levels were undetectable. To assess whether the absence of PSAT1 protein was due to low gene expression, we performed quantitative PCR in each of the three cell types. PSAT1 transcript levels were significantly higher in the resistant cell types compared to the parental MCF-7 cells (Figure 2c). This differential enzyme expression indicated a putative change in de novo serine synthesis as ER+ BC cells progress to endocrine resistance.

Figure 2: Differential PSAT1 expression between sensitive and resistant cell lines.

a) Schematic summarizing the in vitro ER+ breast cancer model systems in terms of responsiveness to endocrine therapy. b) Representative Western blots demonstrating the differential expression of PHGDH and PSAT1 between the endocrine sensitive MCF-7 parental line and the endocrine resistant derivatives (LCC9 and LY2). Densitometry analysis from three independent experiments was performed using ImageJ. c) PSAT1 transcript levels in the endocrine sensitive and resistant cell lines. Quantitation is demonstrated as log2 fold change compared to MCF-7 cells and shown are the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. **** P < 0.0001.

To assess elevated SSP activity, we used stable isotope resolved metabolomics (SIRM) to evaluate carbon or nitrogen incorporation into de novo serine production (Figure 3A). Carbon for serine synthesis is derived from glucose through the glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate. Cell exposure to fully labeled 13C-glucose results in production of three-carbon labeled serine (m+3) and the formation of two-carbon labeled glycine (m+2) through the action of serine hydroxymethyl transferase (SHMT1/2) (Figure 3A). In addition, the amino nitrogen for serine and glycine is provided by transamination of glutamate to alpha-ketoglutarate through PSAT1. Incubation with 15N-labeled glutamine, which is rapidly converted to glutamate by glutaminase, yields both m+1 serine and glycine through the incorporation of 15N to the amino group (Figure 3B). To examine differential SSP activity, we labeled both endocrine sensitive MCF-7 cells and endocrine resistant LY2 cells with either 13C6-glucose or 13C5,15N2-glutamine and analyzed carbon/nitrogen incorporation into serine and glycine. MS analysis demonstrated significantly elevated SSP activity in the resistant LY2 cell line as evidenced by both greater levels of 13C carbon from glucose in serine (m+3) and glycine (m+2) plus elevated m+1 serine/glycine from nitrogen labeled glutamine (Figure 3C&D). The SSP activity in the MCF-7 line was below detectable limits (Figure 3C&D), which suggests higher de novo serine synthesis in endocrine resistant ER+BC cells.

Figure 3: Metabolomic differences between endocrine sensitive and endocrine resistant cell types.

a) Schematic demonstrating serine/glycine carbon labeling patterns derived from 13C6-glucose incubation. Metabolism of uniformly labeled glucose results in triply labeled (m+3) 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG). This labeled glycolytic intermediate is then utilized within the SSP to generate triply labeled serine and two-carbon labeled glycine. b) Schematic demonstrating incorporation of glutamine derived nitrogen into the amino group of intracellular metabolized serine and glycine. Incubation of 13C5,15N2-glutamine results in generation of intracellular nitrogen labeled glutamate, which is then converted to alpha-ketoglutarate by PSAT1 through transamination of amino group to form serine. c) 13C-serine (m+3) and 13C-glycine (m+2) levels were quantified by mass spectrometry analysis from polar metabolite extracts from either MCF-7 or LY2 cells after 13C6-glucose incubation. Data is represented as fractional enrichment and shown are the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. d) Polar metabolite extracts from 13C5,15N2-glutamine labeled MCF-7 or LY2 cells were analyzed by mass spectrometry for nitrogen enrichment into 15N-serine (m+1) or 15N-glycine (m+1). Quantitation is demonstrated as fractional enrichment and shown are mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

This differential expression of SSP enzymes, particularly PSAT1, between sensitive and resistant lines indicates that SSP activity may associate with tamoxifen sensitivity. To investigate this potential metabolic consequence, we altered PSAT1 levels in these cell models as endocrine sensitive MCF-7 cells do not express this SSP enzyme. First, PSAT1 was overexpressed in the MCF-7 cells by ~ 26-fold at the protein level (Figure 4A&B) to determine its effect on MCF-7 cell proliferation and response to 4-OHT treatment compared to the parental cells. While enhanced expression of PSAT1 has no impact on basal proliferation in the MCF-7 cells, it reduced sensitivity to growth inhibition at two different concentrations of 4-OHT (Figure 4B&C). Exposure to 100 or 500nM 4-OHT led to 40–45% reduction in MCF-7 cell proliferation. Yet, PSAT1 overexpressing cells had reduced sensitivity to 4-OHT (22–25% decrease respectively) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4: Overexpression of PSAT1 reduces sensitivity to 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

a) Analysis of PSAT1 transcript levels in the MCF-7 cells stably integrated with either empty vector or vector encoding PSAT1 cDNA. Data is presented as log2 fold change and shown is the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. *** p < 0.001 as determine by unpaired t test. b) Representative Western blot demonstrating PSAT1 protein levels in MCF-7 cells stably selected for PSAT1 overexpression. Densitometry was performed with Image J from three separate experiments. c) Effect of transient PSAT1 overexpression on LCC9 cell proliferation. Data represented as quantitated cell number (x104) and shown is mean ± SD from four separate experiments. d) Response to 4-OHT of MCF-7 cells with or without overexpression of PSAT1. Data is shown as mean ± SD (from four independent experiments) and represented as % decrease relative to EtOH control. *** P < 0.001 100nM 4-OHT, **** P < 0.0001 500nM 4-OHT.

Conversely, the contribution of PSAT1 to 4-OHT resistance was also examined under loss of PSAT1 in the resistant LCC9 cell line. Using stable shRNA, PSAT1 was suppressed in the LCC9 cells compared to scrambled shRNA control and resulted in a moderate decrease in LCC9 proliferation (Figure 5A&B). As expected, 4-OHT did not affect LCC9 cell proliferation. However, loss of PSAT1 significantly increased sensitivity to 4-OHT at two separate concentrations. (Figure 5C). Taken together, these results strongly indicate that PSAT1 and SSP activity may contribute significantly to development of resistance to tamoxifen of ER+BC.

Figure 5: Suppression of PSAT1 increases sensitivity to 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

a) Representative Western blot demonstrating PSAT1 expression in LCC9 cells harboring either scrambled (control) or PSAT1 specific shRNA. Densitometry analysis was performed with Image J from three independent experiments. b) Assessment of PSAT1 loss on LCC9 cell proliferation. Data is presented as total cell number (x104) and shown is the mean ± SD from five independent experiments. *** p < 0.05 as determine by unpaired t test. c) Effect of 4-OHT treatment on cell proliferation in control or PSAT1 silenced LCC9 cells. Quantitation is demonstrated as % decrease relative to EtOH control. Shown is the mean ± SD from five independent experiments. * P < 0.05 250nM 4-OHT, **** P < 0.0001 500nM 4-OHT.

Clinical relevance of PHGDH in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen

Previous reports that were focused on PSAT1 protein expression in clinical ER+BC samples suggested that PHGDH may also contribute to resistance in patients treated with tamoxifen (De Marchi et al., 2017). This was attributed to increased PHGDH protein expression in the tamoxifen treated patients that exhibited poorer clinical outcomes. Using the KM plotter database and analyzing the same patient parameters used for PSAT1 (Figure 1B), we sought to determine if PHGDH levels also associated with survival outcomes in this cohort. We found that patients with higher PHGDH expression demonstrated significantly poorer relapse-free survival compared to patients with low PHGDH expression (Figure 6). Similar to PSAT1, we suppressed PHGDH expression in LCC9 cells to determine whether manipulation of other SSP enzymes would alter sensitivity to 4-OHT treatment. While not significantly affecting LCC9 proliferation, we found that a transient siRNA-mediated decrease in PHGDH levels (~ 56 %) (Figure 7A&B) led to increased efficacy of 4-OHT to inhibit LCC9 proliferation (Figure 7C). Multiple groups have identified various pharmacological inhibitors of PHGDH that have been examined for their efficacay as anti-cancer agents (Mullarky et al., 2016, Pacold et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2017). To assess the potential clinical translation of these genetic studies, we treated LCC9 cells with a PHGDH inhibitor (PKUMDL-WQ-2201) alone or in combination with two concentrations of 4-OHT. As illustrated in Figure 7D and Table 1, PHGDH inhibition did not significantly impact LCC9 cell proliferation up to a 100μM, yet sensitized these cells to 4-OHT. Cumulatively, these data indicate that increased PHGDH as well as PSAT1 in the SSP pathway contribute to sensitivity of ER+BC cells to tamoxifen therapy.

Figure 6: Clinical relevance of PHGDH in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of patient outcomes was done using the online KM Plotter database. Relapse-free survival of ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen stratified by low (n=486) or high (n=184) PHGDH expression. Shown are the hazard ratios (HR) and logrank P values.

Figure 7: Suppression of PHGDH increases sensitivity to 4-hydroxytamoxifen.

a) Representative Western blot demonstrating PHGDH expression in LCC9 cells transiently transfected with either scrambled (control) or PHGDH-specific siRNA. Densitometry analysis was performed with Image J. b) Effect of transient PHGDH suppression on cell proliferation in LCC9 cells. Data represented as quantitated cell number (x104) and shown is mean ± SD from three separate experiments. c) Effect of 4-OHT treatment on cell proliferation in control or PSAT1 silenced LCC9 cells. Quantitation is demonstrated as % decrease relative to EtOH control from three independent experiments. Shown is the mean ± SD. ** P < 0.005. d) Effect of PHGDH inhibitor on sensitivity of LCC9 cells to 4-OHT. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of cell viability relative to DMSO-treated control of four independent experiments. *P < 0.007 versus PKUMDL-WQ-2201 as determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test.

Table 1: Tamoxifen reduces the IC50 values for the PHGDH inhibitor in LCC9 cells.

Values (in μM) for PHGDH inhibitor PKUMDL-WQ-2201 +/− 100 nM or 1 μM 4-OHT. IC50 values were calculated in GraphPad Prism and are the average of 8 separate experiments.

| LCC9 (IC50) | ||

|---|---|---|

| PKUMDL-WQ-2201 | + 100 nM 4-OHT | + 1 μM 4-OHT |

| 105 ± 10 | 55 ± 11 | 57 ± 8 |

| P = 0.0056 | P = 0.0088 | |

Significantly different from PKUMDL-WQ-2201 alone: P = 0.0056 and 0.0088 for 0.1 and 1.0 μM 4-OHT, respectively as determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test.

Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated that both PSAT1 and PHGDH correlate with poorer relapse-free survival in ER+ patients treated with tamoxifen. These studies included gene array analysis in LCM-procured breast carcinoma cells in which ER activity was quantified by radio-ligand assay as used in the original tamoxifen studies by the NSABP (Fisher et al., 1983, Fisher et al., 1981). This approach evaluating only LCM-isolated breast carcinoma cells supports previously published findings that implicated PSAT1 in tamoxifen resistance (De Marchi et al., 2017, Martens et al., 2005). Furthermore, we clearly demonstrated that manipulation of PSAT1, either via overexpression in a tamoxifen- sensitive ER+ cell model or suppression in a tamoxifen-resistant ER+ cell model, alters cellular sensitivity to 4-OHT treatment. In addition, downregulation or pharmacological inhibition of PHGDH was also shown to increase sensitivity to 4-OHT in ER+ tamoxifen-resistant cells. These data strongly indicate that these two enzymes in the serine synthetic pathway contribute to tamoxifen resistance.

Tamoxifen is a SERM and its primary mode of action is through competing with endogenous estrogens for binding to ERα, resulting in inhibition of the estrogen driven pro-proliferative transcription program without altering the levels of ERα (Ali et al., 2016). This raises an interesting question as to whether tamoxifen resistance mediated by PSAT1 and PHGDH may be dependent upon either the maintenance of ER protein levels, one or more of its coactivators, or protein products of one or more of its gene targets. While the requirement for maintenance of ER as it relates to PSAT1 and PHGDH-mediated resistance would need further investigation, there is preliminary evidence to support this notion. For example, MYC is a known target of ER signaling and its function as well as its role in endocrine resistance requires maintenance of the ER (Chen et al., 2015).

Although these results indicate that PSAT1 and PHGDH SSP enzyme expression associates with 4-OHT sensitivity, the mechanism(s) by which PSAT1 and PHGDH contribute to tamoxifen resistance is unclear. It may be through oncogenic activation of the SSP by proteins such as MYC, which has been suggested to activate transcription of PSAT1 and PHGDH (Sun et al., 2015) and both SSP and MYC have been implicated in endocrine resistance (McNeil et al., 2006, De Marchi et al., 2017, Martens et al., 2005). In addition, SSP-mediated resistance may be related to one of the metabolic consequences of de novo serine synthesis. Previous literature has suggested that glutamine is required for the pro-proliferative estrogen-driven signaling cascade in ER+BC (Chen et al., 2015). It has also been suggested that while uptake of glutamine is independent of estrogen signaling, this process may require maintenance of ER expression (Chen et al., 2015).

PSAT1 is also responsible for the second processing step of intracellular glutamine as it converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate (Mattaini et al., 2016), which connects glutamine metabolism, the SSP, and endocrine resistance to maintenance of ER expression. Alternatively, epigenetic changes have also been proposed as a mechanism for tamoxifen resistance (Stone et al., 2012). These changes include increases in hypomethylated promoter regions of oncogenic genes and hypermethylated promoter regions of tumor suppressors (Dixon, 2014). There is also evidence to suggest that ER coregulators are under epigenetic control and that dysregulation of these coregulators is correlated with resistance to tamoxifen therapy (Girault et al., 2006, van Agthoven et al., 2009). As stated, PSAT1 and PHGDH are both members of the serine synthetic pathway along with PSPH (Mattaini et al., 2016). Downstream, serine can be used in one carbon metabolism to generate s-adenosyl-methionine (SAM) which is the methyl donor for the methylation of nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids and as a result there has been evidence to support that the levels of serine dictate the levels of SAM (Newman and Maddocks, 2017).

Collectively, our new results taken in concert with those validated in the literature support our hypothesis that elevated PSAT1 and PHGDH contribute significantly to tamoxifen resistance through increasing de novo serine synthesis to both enhance glutaminolysis and downstream generation of SAM for subsequent epigenetic changes. Further investigation will be conducted to confirm the relevance of these putative mechanism(s) in contributing to endocrine resistance. While these data demonstrate the feasibility of pharmacological manipulation of PHGDH in altering tamoxifen resistance in vitro, additional studies are warranted, including evaluation of patient derived xenografts of known endocrine sensitivity in mouse models. Logically, similar findings in vivo would support the clinical potential for this combination therapy. In summary, results from our diverse approaches examining SSP gene expression patterns in human breast carcinomas concurrently with therapeutic manipulation in endocrine resistant cell lines confirms the clinical correlation of SSP and TAM sensitivity in ER+ breast cancer and for the first time provides direct experimental evidence that serine synthesis plays a role in TAM resistance. Our findings lay the foundation for the potential translation of co-targeting this pathway with endocrine therapies to maintain endocrine sensitivity in ER+ breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Penn Muluhngwi for his assistance with technical aspects of this work and Zohair Hameed for bioinformatic analysis of patient survival data. We thank Dr. Robert Clarke, Georgetown University Medical Center for the gift of the LCC9 and LY2 cell lines.

Funding

The Center for Environmental and Systems Biochemistry is supported in part by grants RCSIRM (1U24DK097215-01A1) and the Redox Metabolism Shared Resource of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center (P30CA177558). BJP was supported in part by a fellowship from NIH T32 ES011564. This work was also supported by NIH R21 CA219252 (CMK), the Dr. Donald Miller Endowed Professorship in Cancer Metabolism Research (BFC), and funds from the James Graham Brown Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali S, Rasool M, Chaoudhry HP,NP, Jha P, Hafiz A, Mahfooz M, Abdus Sami G, Azhar Kamal M, Bashir S, et al. 2016. Molecular mechanisms and mode of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Bioinformation, 12, 135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres SA, Brock GN & Wittliff JL 2013. Interrogating differences in expression of targeted gene sets to predict breast cancer outcome. BMC Cancer, 13, 326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres SA & Wittliff JL 2012. Co-expression of genes with estrogen receptor-alpha and progesterone receptor in human breast carcinoma tissue. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig, 12, 377–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astruc ME, Chabret C, Bali P, Gagne D & Pons M 1995. Prolonged treatment of breast cancer cells with antiestrogens increases the activating protein-1-mediated response: involvement of the estrogen receptor. Endocrinology, 136, 824–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z & Gust R 2009. Breast cancer, estrogen receptor and ligands. Arch Pharm (Weinheim), 342, 133–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronzert D.a. G., Geoffrey L; Lippman Marc E. 1985. Selection and characterization of a breast cancer cell line resistant to the antiestrogen LY 117018. Endocrinology, 117, 1409–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner N, Boysen B, Jirus S, Skaar TC, Holst-Hansen C, Lippman J, Frandsen T, Spang-Thomsen M, Fuqua SA & Clarke R 1997. MCF7/LCC9: an antiestrogen-resistant MCF-7 variant in which acquired resistance to the steroidal antiestrogen ICI 182,780 confers an early cross-resistance to the nonsteroidal antiestrogen tamoxifen. Cancer Res, 57, 3486–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Wang Y, Warden C & Chen S 2015. Cross-talk between ER and HER2 regulates c-MYC-mediated glutamine metabolism in aromatase inhibitor resistant breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 149, 118–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R, Tyson JJ & Dixon JM 2015. Endocrine resistance in breast cancer--An overview and update. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 418 Pt 3, 220–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi T, Foekens JA, Umar A & Martens JW 2016. Endocrine therapy resistance in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. Drug Discov Today, 21, 1181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi T, Timmermans MA, Sieuwerts AM, Smid M, Look MP, Grebenchtchikov N, Sweep F, Smits JG, Magdolen V, Van Deurzen CHM, et al. 2017. Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 is associated to poor outcome on tamoxifen therapy in recurrent breast cancer. Sci Rep, 7, 2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JM 2014. Endocrine Resistance in Breast Cancer. New Journal of Science, 2014, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, Coates A, Forbes J, Bliss J, Buyse M, Baum M, Buzdar A, Colleoni M, et al. 2010. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol, 28, 509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative, G. 2005. Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet, 365, 1687–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C & Parkin DM 2010. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer, 127, 2893–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Redmond C, Brown A, Wickerham DL, Wolmark N, Allegra J, Escher G, Lippman M, Savlov E, Wittliff J, et al. 1983. Influence of tumor estrogen and progesterone receptor levels on the response to tamoxifen and chemotherapy in primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol, 1, 227–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Redmond C, Brown A, Wolmark N, Wittliff J, Fisher ER, Plotkin D, Bowman D, Sachs S, Wolter J, et al. 1981. Treatment of primary breast cancer with chemotherapy and tamoxifen. N Engl J Med, 305, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Ge A, Xu S, You Z, Ning S, Zhao Y & Pang D 2017. PSAT1 is regulated by ATF4 and enhances cell proliferation via the GSK3beta/beta-catenin/cyclin D1 signaling pathway in ER-negative breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 36, 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet HM, Cheng SB, Christensen EM & Filardo EJ 2015. The G-protein coupled estrogen receptor, GPER: The inside and inside-out story. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 418 Pt 3, 207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault I, Bieche I & Lidereau R 2006. Role of estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional coregulators in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Maturitas, 54, 342–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q & Szallasi Z 2010. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 123, 725–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, Allred DC, Hagerty KL, Badve S, Fitzgibbons PL, Francis G, Goldstein NS, Hayes M, et al. 2010. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol, 28, 2784–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AN, Tan J, Wang Y, Yan J, Higashi RM & Fan TW 2017. Probing the metabolic phenotype of breast cancer cells by multiple tracer stable isotope resolved metabolomics. Metab Eng, 43, 125–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KM, Chao TB, Tian YF, Lin CY, Lee SW, Chuang HY, Chan TC, Chen TJ, Hsing CH, Sheu MJ, et al. 2016. Overexpression of the PSAT1 Gene in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Is an Indicator of Poor Prognosis. J Cancer, 7, 1088–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Jia Y, Cao Y, Wu S, Jiang H, Sun X, Ma J, Yin X, Mao A & Shang M 2016. Overexpression of Phosphoserine Aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) Predicts Poor Prognosis and Associates with Tumor Progression in Human Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem, 39, 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JW, Nimmrich I, Koenig T, Look MP, Harbeck N, Model F, Kluth A, Bolt-De Vries J, Sieuwerts AM, Portengen H, et al. 2005. Association of DNA methylation of phosphoserine aminotransferase with response to endocrine therapy in patients with recurrent breast cancer. Cancer Res, 65, 4101–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaini KR, Sullivan MR & Vander Heiden MG 2016. The importance of serine metabolism in cancer. J Cell Biol, 214, 249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcneil CM, Sergio CM, Anderson LR, Inman CK, Eggleton SA, Murphy NC, Millar EK, Crea P, Kench JG, Alles MC, et al. 2006. c-Myc overexpression and endocrine resistance in breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 102, 147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaly Z, Kormos M, Lanczky A, Dank M, Budczies J, Szasz MA & Gyorffy B 2013. A meta-analysis of gene expression-based biomarkers predicting outcome after tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 140, 219–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullarky E, Lucki NC, Beheshti Zavareh R, Anglin JL, Gomes AP, Nicolay BN, Wong JC, Christen S, Takahashi H, Singh PK, et al. 2016. Identification of a small molecule inhibitor of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase to target serine biosynthesis in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 113, 1778–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AC & Maddocks ODK 2017. Serine and Functional Metabolites in Cancer. Trends Cell Biol, 27, 645–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold ME, Brimacombe KR, Chan SH, Rohde JM, Lewis CA, Swier LJ, Possemato R, Chen WW, Sullivan LB, Fiske BP, et al. 2016. A PHGDH inhibitor reveals coordination of serine synthesis and one-carbon unit fate. Nat Chem Biol, 12, 452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, Van De Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. 2000. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature, 406, 747–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JF 2001. ICI 182,780 (Fulvestrant)--the first oestrogen receptor down-regulator--current clinical data. Br J Cancer, 85 Suppl 2, 11–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, Hess KR, Stec J, Ayers M, Wagner P, et al. 2005. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res, 11, 5678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn Mb LS 2003. Agents for Chemoprevention and Their Mechanism of Action In: Kufe Dw PR, Weichselbaum Rr, et al. (ed.) Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th ed. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker. [Google Scholar]

- Stone A, Valdes-Mora F, Gee JM, Farrow L, Mcclelland RA, Fiegl H, Dutkowski C, Mccloy RA, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA, et al. 2012. Tamoxifen-induced epigenetic silencing of oestrogen-regulated genes in anti-hormone resistant breast cancer. PLoS One, 7, e40466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C ZX, Chen Y, Jia Q, Yang J, Shu Y 2018. MicroRNA-365 suppresses cell growth and invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by modulating phosphoserine aminotransferase 1. Cancer Manag Res, 10, 4581–4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Song L, Wan Q, Wu G, Li X, Wang Y, Wang J, Liu Z, Zhong X, He X, et al. 2015. cMyc-mediated activation of serine biosynthesis pathway is critical for cancer progression under nutrient deprivation conditions. Cell Res, 25, 429–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Agthoven T, Sieuwerts AM, Veldscholte J, Meijer-Van Gelder ME, Smid M, Brinkman A, Den Dekker AT, Leroy IM, Van Ijcken WF, Sleijfer S, et al. 2009. CITED2 and NCOR2 in anti-oestrogen resistance and progression of breast cancer. Br J Cancer, 101, 1824–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liberti MV, Liu P, Deng X, Liu Y, Locasale JW & Lai L 2017. Rational Design of Selective Allosteric Inhibitors of PHGDH and Serine Synthesis with Anti-tumor Activity. Cell Chem Biol, 24, 55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittliff J 2010. Laser capture microdissection and its use in genomics and proteomics Reliable lab solutions: techniques in confocal microscopy. Elsevier, Boston, 463–477. [Google Scholar]

- Wittliff J, Pasic R & Bland K 1998. Steroid and peptide hormone receptors: methods, quality control and clinical use The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases. Philadelphia, PA, WB Saunders Co, 458–498. [Google Scholar]

- Wittliff JL, Kruer TL, Andres SA & Smolenkova I 2008. Molecular signatures of estrogen receptor-associated genes in breast cancer predict clinical outcome. Adv Exp Med Biol, 617, 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S JH, Fang S, Yin F, Wang Z, Jia Y, Sun X, Wu S, Jiang T, Mao A 2015. MicroRNA-340 Inhibits Esophageal Cancer Cell Growth and Invasion by Targeting Phosphoserine Aminotransferase 1. Cell Physiol Biochem, 37, 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Wu J, Cai J, He Z, Yuan J, Zhu X, Li Y, Li M & Guan H 2015. PSAT1 regulates cyclin D1 degradation and sustains proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int J Cancer, 136, E39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip CH & Rhodes A 2014. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Future Oncol, 10, 2293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]