Abstract

Early pregnancy renal anhydramios (EPRA) comprises congenital renal disease that results in fetal anhydramnios by 22 weeks of gestation. It occurs in over 1 in 2000 pregnancies and affects 1500 families in the US annually. EPRA was historically considered universally fatal due to associated pulmonary hypoplasia and neonatal respiratory failure. There are several etiologies of fetal renal failure that result in EPRA including bilateral renal agenesis, cystic kidney disease, and lower urinary tract obstruction. Appropriate sonographic evaluation is required to arrive at the appropriate urogenital diagnosis and to identify additional anomalies that allude to a specific genetic diagnosis. Genetic evaluation variably includes karyotype, microarray, targeted gene testing, panels, or whole exome sequencing depending on presentation. Patients receiving a fetal diagnosis of EPRA should be offered management options of pregnancy termination or perinatal palliative care, with the option of serial amnioinfusion therapy offered on a research basis. Preliminary data from case reports demonstrate an association between serial amnioinfusion therapy and short-term postnatal survival of EPRA, with excellent respiratory function in the neonatal period. A multicenter trial, the renal anhydramnios fetal therapy (RAFT) trial, is underway. We sought to review the initial diagnosis ultrasound findings, genetic etiologies, and current management options for EPRA.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Early pregnancy renal anhydramnios (EPRA) encompasses congenital renal disease that results in fetal anhydramnios by 22 wks of gestation. It is defined here as a unique entity within congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) because it captures a population for whom neonatal survival without fetal intervention has never been described. EPRA complicates >1 in 2000 pregnancies and is thought to be universally fatal because of pulmonary hypoplasia.1–3 The main etiologies of EPRA are bilateral renal agenesis, cystic kidney disease (CKD), and obstructive uropathies such as lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO).

Amniotic fluid may be present in EPRA up to 22 weeks’ gestational age (GA) both because amniotic fluid is produced in a significant amount by the placenta and umbilical cord up to 18 weeks’ GA and because there may be some damaged or involuted renal tissue that produces fetal urine for a short interval. The mechanism of anhydramnios induced lung hypoplasia hinges on intrauterine fluid dynamics. Absence of amniotic fluid allows lung fluid to escape the tracheobronchial tree during normal fetal glottis opening and closing.4,5 The fetal tracheobronchial tree then becomes depressurized, which prevents fetal lung growth. Evidence to support this critical role for amniotic fluid in fetal lung growth include large animal experiments of anhydramnios as well as other human diseases that cause oligo- or anhydramnios, such as preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM).6 Furthermore, occlusion of the fetal tracheobronchial tree and thus prevention of pulmonary fluid egress has been shown to promote lung growth in conditions such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia.7 This causative link between amniotic fluid levels and functional lung growth is further strengthened by an experiment of nature in which one fetus in a set of monoamniotic, monochorionic twins had bilateral renal agenesis. The twin with renal agenesis shared amniotic fluid with the normal twin and had normal respiratory function at birth.8 The association between amniotic fluid and lung development has motivated investigators to attempt serial amnioinfusions in both bilateral renal agenesis9 and other EPRA-related conditions.10 Anecdotal cases where fetuses treated in this fashion survived postnatally and went on to undergo successful dialysis and renal transplant11 provide a rationale to study amniofusion for this condition, as these successful case reports demonstrate that both short term respiratory survival and long-term renal survival is possible in EPRA.12–14

The renal anhydramnios fetal therapy (RAFT) trial is a multicenter trial that has been designed to prospectively evaluate serial amnioinfusions for EPRA.12 The trial was formulated in order to provide rigorous prospective study of a therapy that had been embraced by many fetal therapists and patients with little to no evidence. A national ethics symposium was convened to navigate the complex issues of autonomy, futility, informed consent, financial risk, and societal cost.15 That symposium provided a roadmap for developing an ethically anchored protocol. The symposium reached the same conclusions as a 2016 NIH workshop16 and the work of other ethicists that this therapy should not be offered outside the setting of an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved research study. Based on this consensus, a proposal to the North American Fetal Therapy Network (NAFTNet) was formulated to create a multicenter study to examine this therapy under a single IRB approved protocol based at Johns Hopkins Hospital. After several iterations with the NAFTNet scientific and executive board, a protocol was agreed upon and subsequently approved by the Johns Hopkins IRB. The aims of the resulting RAFT trial are to determine the safety, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy of serial amnioinfusions for EPRA. The trial has just begun at Johns Hopkins and Stanford with six other NAFTNet centers in the process of onboarding. In this review, we seek to describe the approach to the sonographic diagnosis of EPRA, genetic evaluation of EPRA as well as provide an overall description of the RAFT trial’s design.

2 |. DIAGNOSIS

Enrollment in the RAFT trial requires confirmation of an isolated EPRA diagnosis. The diagnosis is initially suspected at the time of routine evaluation of fetal renal pathology by anatomy ultrasound at 18 to 22 weeks’ GA. Anhydramnios identified at this GA can result from a number of etiologies including PPROM, renal failure, bladder outlet obstruction, or poor placental perfusion. A clinical evaluation for PPROM is recommended if the patient is symptomatic or if renal causes are not suspected. In cases with anhydramnios, evaluation of the entire genitourinary tract, including the urethra, bladder, ureters, and kidneys, is essential to identify or rule out a specific genitourinary anomaly. Less severe anomalies, such as unilateral renal agenesis, mild urinary tract dilation, pelvic kidneys, and horseshoe kidneys are relatively common and typically do not result in oligo- or anhydramnios.

In the setting of anhydramnios, a complete anatomy ultrasound is critical for the identification of any additional fetal anatomic variations. For patients with anhydramnios prior to 22 weeks of gestation in the setting of LUTO, a vesicocentesis can sometimes be helpful to confirm lack of bladder filling, indicating likely renal dysplasia and poor candidacy for a vesicoamniotic shunt or ablation of posterior urethral valves (PUV). Once the sonographic diagnosis of EPRA is suspected, the RAFT protocol calls for the performance of a diagnostic amnioinfusion17 in order to (1) confirm intact membranes, (2) allow for a more detailed sonographic fetal evaluation to confirm the presence or absence of renal tissue and/or vasculature, and (3) more accurately assess for the presence of other anomalies. The presence of other significant fetal anomalies, aside from anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract, may indicate a syndromic etiology. Furthermore, other significant anomalies in the background of EPRA impede generalizability of the data and for the initial RAFT trial are, therefore, exclusion criteria (see Table 1 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria).

TABLE 1.

Renal anhydramnios fetal therapy (RAFT) trial inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria: |

|

| Exclusion criteria: |

|

2.1 |. Ultrasound findings in EPRA

In the RAFT trial, EPRA has been divided into two groups to be studied independently in terms of response to serial amnioinfusions. The first is the congenital bilateral renal agenesis group (CoBRA) and the second is the fetal renal failure (FRF) group in which anhydramnios is seen before 22 weeks but some kidney tissue is present. Standard ultrasound evaluation of parental kidneys is also warranted and discovery of renal abnormalities on these studies suggest an inherited genetic condition.

2.1.1 |. CoBRA

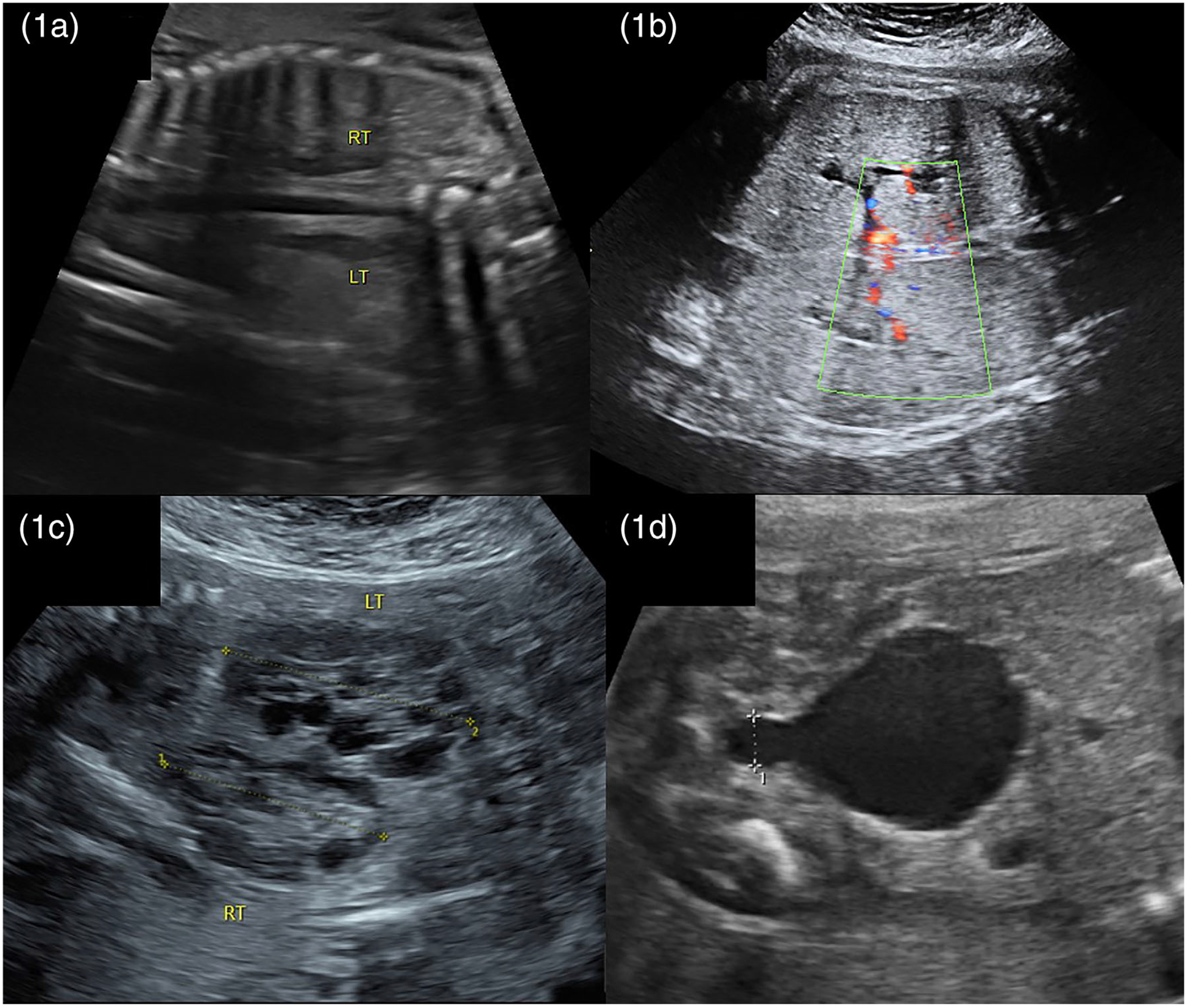

CoBRA describes the absence of kidneys, proposed to occur as a failure of the ureteric bud to fuse with the metanephric blastema. CoBRA is suspected when both kidneys are not visualized on ultrasound. The fetal adrenals can normally be identified cephalad and separate from the kidney with a hypoechoic cortex and hyperechoic medulla. In CoBRA, the adrenals flatten out from their typical “Y” shaped appearance, in what has been referred to as the “lying down adrenal sign” Figure 1a.18 The diagnosis of renal agenesis can also be confirmed by the absence of both of the renal arteries originating from the aorta on the coronal view.

FIGURE 1.

Etiologies of early pregnancy renal anhydramnios (EPRA) 1a. Bilateral renal agenesis: absence of kidneys with “lying down adrenals” 1b. Polycystic kidney disease: large hyperechoic kidneys 1c. Multicystic kidney disease: kidneys with multiple cysts of variable size 1d. Lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO): large bladder with “keyhole” appearance

2.1.2 |. Cystic kidney disease

CKD comprises a group of renal parenchymal disorders. Included in this group are autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), and multicystic dysplastic kidney disease (MCDK). ADPKD is rarely a cause of prenatal anhydramnios as it is most often detected in adulthood with cystic and enlarged kidneys and thus is not included in this review.

ARPKD is defined by the presence of multiple small cysts in the medullary collecting ducts resulting in enlarged, hyperechoic kidneys with loss of corticomedullary differentiation. Cysts can be discrete, 5 to 7mm, or be too small to visualize19 Figure 1b. The lungs may appear proportionally small due to abdominal distention and pulmonary hypoplasia. At present, amnioinfusion for ARPKD is controversial because in non-EPRA ARPKD, the large kidney size leads to severe respiratory compromise even without pulmonary hypoplasia from anhydramnios. For this reason, patients with classic ARPKD detected on ultrasound are not currently eligible for therapy in the RAFT trial.

MCDK occurs either secondary to failure of ureteric bud signaling leading to loss of nephrons and cyst formation or due to early ureteral obstruction with subsequent development of multiple noncommunicating cysts in the kidneys. Ultrasound is notable for multiple anechoic cysts of variable sizes replacing the normal renal parenchyma Figure 1c. Macrocysts, (>10 mm), differentiate MCKD from ARPKD. While either bilateral or unilateral involvement is possible, the prognosis of unilateral MCDK is far superior given the natural compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral normal kidney.20

2.1.3 |. LUTO

Urinary tract obstruction includes a spectrum from mild urinary tract dilation caused by obstruction of the ureter to complete LUTO. LUTO, also known as bladder outlet obstruction, involves a mechanical blockage at the level of the urethra that prevents flow from the bladder into the amniotic cavity. This is diagnosed by identification of an enlarged bladder with a keyhole shape at the bladder outlet secondary to PUV or much less commonly urethral atresia Figure 1d. A staging system for LUTO has been developed as a guide to therapeutic intervention.1 When anyhdramnios is present due to this disease spectrum, the consequence of lower obstruction is kidney destruction resulting in renal failure, classified as LUTO stage IV. Only patient’s with this severest stage of LUTO are candidates for RAFT. In cases of LUTO, documentation of renal failure by vesicocentesis without significant bladder filling is required. If the bladder fills significantly patients are candidates for vesicoamniotic shunting rather than RAFT.21

2.2 |. Genetic evaluation

Genetic counseling and evaluation are required for RAFT trial participants. At a minimum, patients must have normal prenatal karyotype or a prenatal chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) result absent of pathogenic microdeletions or duplications. Genitourinary anomalies that lead to anhydramnios may be associated with a variety of genetic, epigenetic, and nongenetic etiologies. Chromosomal abnormalities, copy number variants, and single gene disorders have all been reported in cases of renal agenesis, CKD, and LUTO. Genetic risk assessment for fetuses with anhydramnios should include thorough review of fetal imaging to determine the presence or absence of additional fetal anomalies, as these greatly impact the differential diagnosis. Potter sequence and clubbed feet are considered to be deformations secondary to anhydramnios rather than additional anomalies. The isolated finding of EPRA is less suggestive of a fetal cytogenetic abnormality than when EPRA is identified as part of a constellation of anomalies, with a 5.18% chromosomal abnormality detection rate in cases of isolated urinary system anomalies and a 33.3% chromosomal abnormality detection rate in cases of nonisolated urinary system anomalies.22 Yet, cytogenetic anomalies cannot be excluded without diagnostic testing. Genetic evaluation for EPRA can include fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis for rapid detection of aneuploidy for chromosomes 21, 18, 13, X, and Y in cases in which a very rapid turnaround time is important; karyotyping, especially if a common aneuploidy is suspected; or CMA.

Prenatal karyotype analysis provides structural and numerical assessment of fetal or placental chromosomes at a resolution of ~7 Mb. Cytogenetically visible chromosome abnormalities including trisomy 22,23 ring chromosome 4 mosaicism,24triple X syndrome (47,XXX),25 partial trisomy 13 and partial trisomy 16,26 partial deletion 15 and partial deletion 18,27 and mosaic trisomy3 11 have all been reported in cases of renal agenesis. An estimated 6% to 10% of fetal LUTO cases are associated with chromosomal aneuploidy, with some reports suggesting that the risk of aneuploidy with PUV is as high as 20%.28,29 Trisomy 13 and trisomy 18 are the aneuploidies most commonly associated with LUTO, although many other chromosomal abnormalities have been described. While isolated infantile PKD is not commonly associated with fetal aneuploidy, abnormal karyotypes have been previously reported, including trisomy 9. Furthermore, dual genetic diagnoses are possible, as in a case of Meckel-Gruber syndrome and mosaic trisomy 17 described by Cierna et al,30 thus prudent genetic test selection is essential for appropriate prognosis and recurrence risk counseling.

CMA can increase the diagnostic yield of prenatal testing by detecting copy number changes that cannot be detected by standard cytogenetic analysis, and as such is recommended for patients undergoing prenatal diagnosis for major structural fetal anomalies.31

CMA provides a 7.4% to 11.6% incremental yield over karyotype in the setting of a fetal genitourinary anomaly.32,33 In the cohort of 149 fetuses with renal parenchyma malformations (including renal agenesis, renal dysplasia, and CDK) described by Lin et al,34 1.3% had an identified chromosomal abnormality (≥10 Mb) whereas 4.7% had clinically significant copy number variants (<10 Mb). Copy number variants described in this cohort (n = 7) included two cases of renal cysts and diabetes (RCAD) syndrome (17q12 deletion) and one case each of Wolf-Hischhorn syndrome (4p1.63 deletion)/8p23.1-pter duplication, 20q13.33-qter duplication/Phelan-Mcdermid syndrome (22q13.33 deletion), Bardet-Biedl syndrome 3/Charcot-Marie-Tooth syndrome type 1A, mental retardation an microcephaly with pontine and cerebellar hypoplasia (Xp11.4 deletion), and 22q11.2 deletion. Copy number variants detectable by CMA in fetuses with EPRA presentations described in Hu et al’s cohort included once case each of RCAD in a fetus with MCDK, Williams-Beuren syndrome (7q11.23 deletion) in a fetus with MCDK, 1q21.1 microduplication in a fetus with kidney agenesis, 13q31.1q34 deletion in a fetus with kidney agenesis, and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in a fetus with kidney agenesis. While most fetuses with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome would not present with anhydramnios, genitourinary anomalies including MCDK and bilateral renal agenesis/bilateral renal dysplasia have been described in multiple affected fetuses.35,36 CMA should be routinely offered if possible as either a first-line test or as follow-up to a normal FISH or karyotype result in the setting of anhydramnios due to a renal anomaly.

In the long run, cytogenetic testing alone may not be sufficient in the work-up of anhydramnios, whether in isolation or concurrent with additional fetal anomalies. Several genetic syndromes have been implicated as the underlying cause of bilateral renal agenesis, CKD, and LUTO, although the prenatal clinical suspicion for these syndromes is significantly impacted by the presence of additional anomalies, as described in Table 2. Indeed, parental carrier testing and prenatal PKHD1 analysis as part of a multigene panel will likely have higher yield than a karyotype or CMA when ARPKD is suspected by ultrasound.37 While apparently isolated renal anomalies may convey a more promising prognosis prenatally, patients should be counseled that this does not rule out a syndromic etiology of anhydramnios, and that extrarenal anomalies may still be identified after birth. Targeted multigene panels are available based on fetal presentation and may serve as an efficacious use of financial resources in comparison to clinical whole exome sequencing (WES), which may be cost-prohibitive.

TABLE 2.

Early pregnancy renal anhydramnios (EPRA) syndromes with associated genes and anomalies

| Syndrome | Inheritance | Gene(s) | Reported Associated Anomalies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal agenesis | Fraser syndrome | AR | FRAS1, FREM2, GRIP1 | Cryptophthalmos, hypertelorism, laryngeal atresia/stenosis, cleft lip/palate, genital anomalies, renal agenesis, renal hypoplasia, syndactyly, meningomyelocele, encephalocele |

| Pallister-Hall syndrome | AD | GLI3 | IUGR, microtia, microphthalmia, flat nasal bridge, cleft lip/palate, congenital heart defect, fused ribs, genital anomalies, renal agenesis, renal dysplasia, hemivertebrae, shortened limbs, postaxial polydactyly, syndactyly, holoprosencephaly | |

| Renal hypodysplasia/aplasia 3 | AD with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity | GREB1L | Genital anomalies, renal agenesis, renal dysplasia, hydronephrosis, duplicated ureter | |

| CKD: MCDK | Fryns syndrome | AR | N/A | Diaphragmatic hernia, micro/retrognathia, cleft lip/palate, congenital heart defect, renal dysplasia, renal cysts, duplicate ureter, omphalocele, duodenal atresia, genital anomalies, rocker-bottom feet, Dandy-Walker malformation, agenesis of the corpus callosum, ventriculomegaly, polyhydramnios |

| Meckel-Gruber syndrome | AR | B9D1, B9D2, CC2D2A, CEP290, KIF14, MKS1, NPHP3, RPGRIP1L, TCTN2, TMEM67, TMEM107, TMEM216, TMEM231 | FGR, microcephaly, micrognathia, low-set ears, microphthalmia, cleft lip/palate, congenital heart defect, omphalocele, genital anomalies, cystic kidneys, renal agenesis, duplicated ureters, bowed long bones, postaxial polydactyly, syndactyly, clinodactyly, talipes, Arnold Chiari malformation, occipital encephalocele, hydrocephalus, Dandy-Walker malformation, cerebral/cerebellar hypoplasia, anencephaly, corpus callosum agenesis, oligohydramnios, enlarged placenta | |

| Renal-hepatic-pancreatic dysplasia 2 | AR | NEK8 | Congenital heart defect, lung hypoplasia, situs inversus, hepatomegaly, genital anomalies, renal cysts, renal dysplasia, skeletal anomalies, talipes | |

| Townes-Brock syndrome | AD | DACT1, SALL1 | Microcephaly, congenital heart defect, duodenal atresia, genital anomalies, renal hypoplasia, multicystic kidneys, renal dysplasia, bifid thumbs, preaxial polydactyly, syndactyly | |

| CKD: PKD | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) | AD | DNAJB11, GANAB, HNF1B, PKD1, PKD2 | Renal cysts with absence of corticomedullary differentiation |

| Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) | AR | PKHD1 | Renal cysts, enlarged kidneys | |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | AR, digenic recessive | ARL6, BBIP1, BBS1, BBS2, BBS4, BBS5, BBS6, BBS7, BBS8, BBS9, BBS10, BBS12, BBS13, CEP290, IFT27, LZTFL1, SDCCAG8, TRIM32, WDPCP | Renal cysts, renal dysplasia, polydactyly (usually postaxial), brachydactyly, cataracts, congenital heart defect, brachycephaly, macrocephaly | |

| Joubert syndrome | AR | AHI1, ARL13B, B9D1, B9D2, C2CD3, CC2D2A, CEP41, CEP104, CEP290, CPLANE1, CSPP1, IFT172, INPP5E, KIAA0556, KIAA0586,KIF7, MKS1, NPHP1, OFD1, PD36D, POC1B, RPGRIP1L, TCTN1, TCTN2,TCTN3, TMEM67, TMEM107, TMEM138 TMEM216, TMEM231, TMEM237, TTC21B, ZNF423 | Macrocephaly, low-set ears, renal cysts, occipital meningocele/myelomeningocele, brainstem hypoplasia, molar tooth sign (on MRI), cerebellar vermis hypoplasia/dysgenesis/ agenesis | |

| McCusick-Kaufman syndrome | AR | MKKS | Congenital heart defect, Hirschprung disease, imperforate anus, genital anomalies, renal cysts, polydactyly, syndactyly | |

| Renal cysts and diabetes syndrome (RCAD) | AD | HNF1B | Renal cysts, renal dysplasia, duplicated ureter | |

| LUTO | BNC2-related LUTO | AD with variable expressivity | BNC2 | LUTO |

| Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome | AD | ACTG2, MYH11 | Microcolon, hydronephrosis, LUTO | |

| Prune belly syndrome | AR | CHRM3, ACTA2 | Congenital heart defect, prune belly, genital anomalies, LUTO, talipes | |

| Urofacial syndrome | AR | HPSE2, LRIG2 | LUTO, hydronephrosis |

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; CKD, cystic kidney disease; LUTO, lower urinary outlet obstruction; MCKD, multicystic kidney disease; PKD, polycystic kidney disease.

Given the enhanced detection rates of WES for fetal anomalies with normal cytogenetic results and the impact that genetic diagnoses from WES may have on our understanding of favorable responses to treatment for EPRA, all patients enrolled in RAFT will be offered WES without incurring personal costs. This is possible secondary to grant funding provided by the University of California, San Francisco. The continued identification of new genes involved in isolated renal anomalies, such as GREB1L, which has been identified in families with recurrent renal agenesis, supports the notion that WES may be superior to multigene EPRA panels in the genetic work-up of such anomalies.38–40 A favorable response to prenatal EPRA treatment seems plausible in fetuses with isolated GREB1L-associated bilateral renal agenesis, but further research is indicated to evaluate the effects of this in affected fetuses.

2.3 |. Management of EPRA and informed consent

Following diagnosis of isolated EPRA, a patient evaluated within the RAFT trial is counseled by a multidisciplinary team consisting of specialists from maternal fetal medicine, pediatric surgery, genetic counseling, nephrology, neonatology, and social work to ensure proper informed consent.15 During the consenting process, maternal, fetal, neonatal, and childhood risks are fully explained and include explicit discussions of the uncertainty of serial amnioinfusion success. Medical risks associated with serial amnioinfusions occur secondary to penetration of the uterus and membranes and include PROM, preterm labor, placental abruption, chorioamnionitis, and uterine rupture.12 Furthermore, if survival is achieved, the postnatal challenges for the neonate with EPRA are discussed in detail. These challenges include the need for dialysis, likelihood of complications from dialysis access, need for supplemental nutrition likely by gastrostomy tube, risk of sepsis, recurrent hospitalizations, eventual need for kidney transplant, requirement for immunosuppression after a kidney transplant, and possible need for urinary tract reconstruction. Therapeutic intervention for EPRA is not without psychosocial risk as well, and further research is indicated to evaluate the psychological burden to parents and families enrolling in experimental fetal therapies for a previously fatal disease. Lastly, the financial and logistical challenges of insurance copay, time away from work, and the need for possible temporary relocation to a RAFT center will be discussed. The parents will receive the consent form at the first visit giving them 1 to 2 weeks to review it.

Potential participants are provided the option of pregnancy termination or perinatal palliative care, in addition to the option to participate in RAFT. Candidates who decline serial amnioinfusions are offered pregnancy termination via induction of labor vs dilation and evacuation or continuation of the pregnancy with nonaggressive obstetric management followed by nonaggressive neonatal management in a manner that maximizes neonatal comfort and quality of life in the setting of a lethal diagnosis.41 Patients with EPRA declining serial amnioinfusions are encouraged to collaborate with the multidisciplinary team (including but not limited to Maternal Fetal Medicine, Neonatology, Genetic Counseling, and Chaplaincy) to develop an individualized birth plan designed to honor the spiritual needs and values of the patient.41 Autopsy should be offered to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate for extrarenal anomalies that may aid in phenotype-driven genetic testing on products of conception.

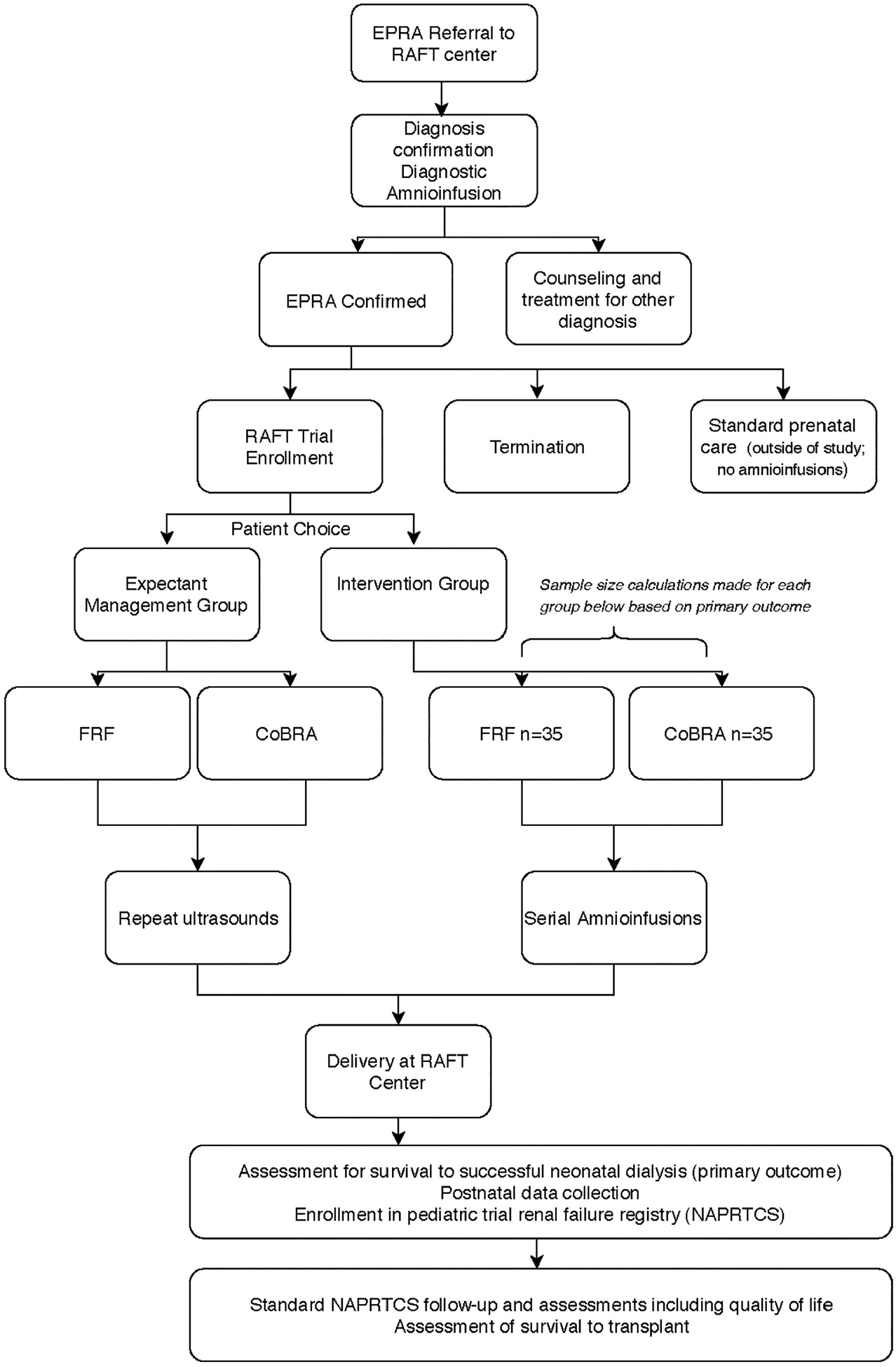

Once the diagnosis of EPRA is confirmed, counseling is complete, and a patient is deemed eligible for serial amnioinfusions, enrollment into the study will be offered. If the patient elects to enroll in the study, they will be given a further choice of intervention with serial amnioinfusions or expectant management with repeat imaging. Participants will not be randomized because there is no realistic hope that expectant management will lead to postnatal survival. Patients who do not choose to undergo amnioinfusions but who also do not elect to terminate will provide invaluable insight into the in utero natural history of EPRA if they enroll in the trial Figure 2. The sample size of this trial is based on a calculation of the number of patients required to adequately determine a postnatal survival rate of amnioinfusions for EPRA with narrow confidence intervals. Postnatal survival will be defined as survival to successful dialysis for 15 continuous days; this is the primary outcome measure. We have determined that 35 maternal/fetal participants are required in order to calculate a survival rate of anywhere from 20% to 80%. We plan to study two 35-participant cohorts of EPRA patients, those with EPRA from bilateral renal agenesis and those with EPRA from FRF. We will therefore aim for a total of 70 maternal/fetal pairs with EPRA to undergo serial amnioinfusions. Additionally we will aim to recruit 30 maternal/fetal pairs with EPRA in the expectant management group for a total of 100 participants.

FIGURE 2.

Flow sheet for evaluation, diagnosis of early pregnancy renal anhydramnios (EPRA), and candidacy for renal anhydramnios fetal therapy (RAFT)

During the prenatal portion of the trial, we plan to collect a small specimen of amniotic fluid from participants in the amnioinfusion group during each amnioinfusion. This fluid will be assayed for different protein and lipid measures of lung maturity. Additionally, in both the amnioinfusion group and the expectant management group we will study ultrasound, MRI, and echocardiogram measures of lung growth. We will correlate these biochemical and radiologic markers with survival in order to better understand who is likely to respond to amnioinfusions and why that response is occurring. We also plan to study several secondary and tertiary outcomes in our surviving EPRA patients. These outcomes include survival to discharge from a RAFT center, survival to transplant and quality of life measures for both participants and their families. All patients will deliver at a RAFT center and they will be enrolled in the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) registry for long-term evaluation.

3 |. CONCLUSION

In summary, we have defined several fetal renal etiologies of EPRA. Serial amnioinfusions are currently an accepted therapeutic option for patients who desire to enroll in the RAFT trial. Isolated cases of bilateral renal agenesis, MCKD and LUTO with renal failure are candidates for RAFT trial screening. Sonographic diagnosis and cytogenetic or molecular evaluation are required as part of the inclusion/exclusion criteria prior to enrollment. Patients can be referred to a participating RAFT center for management that includes extensive counseling regarding the intra-pregnancy therapy and neonatal management.

What is already known about this topic?

Fetal onset congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) that result in early anhydramnios are considered lethal. Etiologies of CAKUT include congenital bilateral renal agenesis, cystic kidney disease, and lower urinary tract obstruction.

Cases of survival after serial anmnioinfusions for these lethal CAKUT defects have been reported with some survivors going on to receive successful renal replacement therapy and kidney transplant.

What does this study add?

This review defines early pregnancy renal anhydramnios (EPRA) as the subset of CAKUT anomalies that are considered universally lethal due to pulmonary hypoplasia.

We outline a sonographic and genetic evaluation to establish the diagnosis of isolated EPRA.

We provide background and defined criteria for inclusion in the renal anhydramnios fetal therapy (RAFT), which will assess the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of serial amnioinfusions for EPRA in a prospective multicenter study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A.C.J. is funded by grant K23DK119949 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contents of the publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Teresa Sparks is also supported by a grant from the Fetal Health Foundation.

Funding information

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: K23DK119949; Fetal Health Foundation

Footnotes

23rd International Conference of Prenatal Diagnosis and Therapy, “Origins of Early Pregnancy Renal Anhydramnios (EPRA),” Singapore

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ruano R, Safdar A, Au J, et al. Defining and predicting ‘intrauterine fetal renal failure’ in congenital lower urinary tract obstruction. Pediatr Nephrol Berl Ger. 2016;31(4):605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hislop A, Hey E, Reid L. The lungs in congenital bilateral renal agenesis and dysplasia. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54(1):32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balasundaram M, Chock VY, Wu HY, Blumenfeld YJ, Hintz SR. Predictors of poor neonatal outcomes in prenatally diagnosed multicystic dysplastic kidney disease. J Perinatol Off J Calif Perinat Assoc. 2018;38(6):658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adzick NS, Harrison MR, Glick PL, Villa RL, Finkbeiner W. Experimental pulmonary hypoplasia and oligohydramnios: relative contributions of lung fluid and fetal breathing movements. J Pediatr Surg. 1984;19(6):658–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitterman JA. The effects of mechanical forces on fetal lung growth. Clin Perinatol. 1996;23(4):727–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts D, Vause S, Martin W, et al. Amnioinfusion in very early preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (AMIPROM): pregnancy, neonatal and maternal outcomes in a randomized controlled pilot study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(5):490–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelin E, Lee H. Tracheal occlusion for fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the US experience. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36(2):349–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Brayfield MR, Kirsch AJ, Smith EA. Monoamniotic twin discordant for bilateral renal agenesis with normal pulmonary function. Urology. 2004;64(3):589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bienstock JL, Birsner ML, Coleman F, Hueppchen NA. Successful in utero intervention for bilateral renal agenesis. Obstet. Gynecol 2014;124(2) Pt 2 Suppl 1):413–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haeri S, Simon DH, Pillutla K. Serial amnioinfusions for fetal pulmonary palliation in fetuses with renal failure. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med Off J Eur Assoc Perinat Med Fed Asia Ocean Perinat Soc Int Soc Perinat Obstet. 2017;30(2):174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheldon CR, Kim ED, Chandra P, et al. Two infants with bilateral renal agenesis who were bridged by chronic peritoneal dialysis to kidney transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23(6):e13532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Hare EM, Jelin AC, Miller JL, et al. Amnioinfusions to treat early onset anhydramnios caused by renal anomalies: background and rationale for the renal anhydramnios fetal therapy trial. Fetal Diagn. Ther 2019;45(6):365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polzin WJ, Lim FY, Habli M, et al. Use of an amnioport to maintain amniotic fluid volume in fetuses with oligohydramnios secondary to lower urinary tract obstruction or fetal renal anomalies. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2017;41(1):51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Io S, Kondoh E, Chigusa Y, Tani H, Hamanishi J, Konishi I. An experience of second-trimester anhydramnios salvaged by single amnioinfusion. J Med Ultrason 2001. 2018;45(3):525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugarman J, Anderson J, Baschat AA, et al. Ethical considerations concerning amnioinfusions for treating fetal bilateral renal agenesis. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):130–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moxey-Mims M, Raju TNK. Anhydramnios in the setting of renal malformations: the national institutes of health workshop summary. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(6):1069–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vikraman SK, Chandra V, Balakrishnan B, et al. Impact of antepartum diagnostic amnioinfusion on targeted ultrasound imaging of pregnancies presenting with severe oligo- and anhydramnios: An analysis of 61 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;212:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majmudar A, Cohen HL. ‘Lying-Down’ adrenal sign: there are exceptions to the rule among fetuses and neonates. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(12):2599–2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guay-Woodford LM. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: the prototype of the hepato-renal fibrocystic diseases. J Pediatr Genet. 2014;3(2):89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstein A, Goodman TR, Iragorri S. Simple multicystic dysplastic kidney disease: end points for subspecialty follow-up. Pediatr Nephrol Berl Ger. 2008;23(1):111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris RK, Quinlan-Jones E, Kilby MD, Khan KS. Systematic review of accuracy of fetal urine analysis to predict poor postnatal renal function in cases of congenital urinary tract obstruction. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27(10):900–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu T, Zhang Z, Wang J, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal aberrations by chromosomal microarray analysis in fetuses with ultrasound anomalies in the urinary system. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39:1096–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Buggenhout GJ, Verbruggen J, Fryns JP. Renal agenesis and trisomy 22: case report and review. Ann Genet. 1995;38(1):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fryns JP, Kleczkowska A, Jaeken J, Van den Berghe H. Ring chromosome 4 mosaicism and Potter sequence. Ann Genet. 1988;31(2): 120–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogge WA, Vick DJ, Schnatterly PA, MacMillan RH. Bilateral renal agenesis and Mullerian anomalies in a 47,XXX fetus. Am J Med Genet. 1989;33(2):242–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen CP, Chern SR, Lee CC, Town DD, Chen WL, Wang W. Bilateral renal agenesis and fetal ascites in association with partial trisomy 13 and partial trisomy 16 due to a 3:1 segregation of maternal reciprocal translocation t(13;16)(q12.3; p13.2). Prenat Diagn. August 1999;19 (8):783–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Froster UG, Horn LC, Holland H, Strenge S, Faber R. Prenatal diagnosis of del(15)(q26.1) and del(18)(q21.3) due to an unbalanced de novo translocation: ultrasound, molecular cytogenetic and autopsy findings. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20(12):992–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malin G, Tonks AM, Morris RK, Gardosi J, Kilby MD. Congenital lower urinary tract obstruction: a population-based epidemiological study. BJOG-Int J Obstet Gy. 2012;119(12):1455–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders R, Blackmon LR, Hogge WA, Spevak P, Wulfsberg EA. Posterior urethral valves Structural Fetal Abnormalities: The Total Picture. Vol 11 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cierna Z, Janega P, Grochal F, et al. The first reported case of meckelgruber syndrome associated with abnormal karyotype mosaic trisomy 17. Pediatr Dev Pathol Off J Soc Pediatr Pathol Paediatr Pathol Soc. 2017;20(5):449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee on Genetics and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Committee opinion no.682: microarrays and next-generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):262–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaffer LG, Rosenfeld JA, Dabell MP, et al. Detection rates of clinically significant genomic alterations by microarray analysis for specific anomalies detected by ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(10):986–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnelly JC, Platt LD, Rebarber A, Zachary J, Grobman WA, Wapner RJ. Association of copy number variants with specific ultrasonographically detected fetal anomalies. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin S, Shi S, Huang L, et al. Is an analysis of copy number variants necessary for various types of kidney ultrasound anomalies in fetuses? Mol Cytogenet. 2019;12:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noël A-C, Pelluard F, Delezoide AL, et al. Fetal phenotype associated with the 22q11 deletion. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(11):2724–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Batavia JP, Crowley TB, Burrows E, et al. Anomalies of the genitourinary tract in children with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179(3):381–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talati AN, Webster CM, Vora NL. Prenatal genetic considerations of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). Prenat Diagn. 2019;39(9):679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lei TY, Fu F, Li R, et al. Whole-exome sequencing for prenatal diagnosis of fetuses with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc-Eur Ren Assoc. 2017;32(10):1665–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madariaga L, Morinière V, Jeanpierre C, et al. Severe prenatal renal anomalies associated with mutations in HNF1B or PAX2 genes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2013;8(7):1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Tomasi L, David P, Humbert C, et al. Mutations in GREB1L cause bilateral kidney agenesis in humans and mice. Am J Hum Genet. 2017; 101(5):803–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perinatal palliative care: ACOG COMMITTEE OPINION, Number 786. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(3):84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]