Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To disseminate knowledge to mental health nurse educators regarding a course that is successfully preparing registered nurse (RN) students to pass the psychosocial integrity portion of the National Council Licensing Exam for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN). METHOD: Following the implementation of a new concept-based nursing program curricular design, faculty teaching in a psychiatric mental health nursing course embarked on converting lecture-based, content-saturated teaching strategies into active learning strategies. In this article, the overall conceptual framework for the course and specific examples of active learning teaching strategies related to nursing concepts in mental health are described. Information on objectives, clinical placements, testing, class organization, and curricular content are provided. Outcomes are shared revealing success in helping students pass the psychosocial integrity section of the NCLEX-RN. RESULTS: Predictive scores on the HESI RN Psychiatric Mental Health Specialty Exam have been consistently higher than the national average for the United States, and the NCLEX-RN pass rate for the cohort of 90 students was 97%. The majority of student evaluations of the course were positive. CONCLUSIONS: Results suggest that the integration of conceptual and active learning in a psychiatric mental health nursing course may increase the likelihood of student success.

Keywords: psychiatric nursing, teaching, concepts, active learning, nurse educator

Following the implementation of a new concept-based nursing program curricular design, faculty teaching in a psychiatric mental health nursing course embarked on converting lecture-style, content-saturated teaching strategies into active learning strategies. In this article, the overall conceptual framework for the course and specific examples of active learning teaching strategies related to nursing concepts in mental health are described. Information on objectives, clinical placements, testing, class organization, and curricular content are provided. Outcomes are shared revealing success in helping students pass the psychosocial integrity section of the National Council Licensing Exam for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN).

The purpose of this article is to disseminate knowledge to mental health nurse educators regarding a course that is successfully preparing registered nurse (RN) students to pass the psychosocial integrity portion of the NLCEX-RN. These ideas and teaching strategies can be replicated and built on by other nurse educators to create a similar active learning course environment to promote success.

Objective

Conceptual learning provides students with an understanding of the core components of nursing practice instead of promoting memorization of minute details of diseases. Giddens (2017) identifies conceptual learning as a priority for nursing education due to the explosion of information and knowledge in health care. Designing a curricular plan using concepts can bring focus on essential components for application, transfer, and critical thinking for providing patient-centered care. Careful attention to selection and organization of nursing concepts can ensure that specific foundational content needed by the new graduate is obtained. In spite of this, establishing a concept-based curriculum may not necessarily change the faculty teaching strategies without concerted effort.

In contrast to conceptual learning, faculty in a lecture-based, content-saturated curricular design provide extensive amounts of information to a passive group of students allowing minimal time for integration of content (Baron, 2017). Use of a concept-based curriculum can offer more time for students to actively use the acquired information and more time for faculty to engage students. Similarly, active learning, also known as integrative learning, reverses the focus of teaching toward student engagement and application of new and previous knowledge to varying contexts. Active learning has gained attention as a valuable teaching strategy in education (Matsuda, Azaiza, & Salani, 2017) despite somewhat positive but mixed results from a small amount of research (Waltz, Jenkins, & Han, 2014). Some students prefer passive absorption of knowledge from a lecturer, instead of fully participating in active learning. Barriers to active learning exist, such as time for creative development, fear of loss of control of student learning outcomes (Hendricks & Wangerin, 2017), and students’ desire for being told what is on the test in a lecture format.

Method

Faculty in an associate degree nursing program embarked on a curricular revision to move from a lecture-based, content-saturated educational approach toward a focus on concept-based learning with active teaching strategies, starting Autumn semester 2017. The concept-based design consists of three units for organizing concepts: health and illness, professional nursing, and patient profile as shown in Table 1. There are 17 major concepts organized in the units. For example, psychosocial integrity and cognitive function are major concepts in the health and illness unit. Major concepts are further divided into concepts; for example, psychosocial integrity includes the concepts of anxiety, psychosis, and spirituality among others. Each concept has selected exemplars: conditions commonly associated with the concept new graduates will often encounter. Specifically, schizophrenia is an exemplar for the concept psychosis.

Table 1.

Excerpt of Conceptual Framework Applied to Mental Health Nursing Course.

| Unit | Major concept | Concept | Exemplar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health and illness | Psychosocial integrity | Addiction | Substance abuse |

| Psychosis | Schizophrenia | ||

| Mood and effect | Bipolar disorder | ||

| Depression | |||

| Cognitive function | Chronic confusion | Dementia | |

| Acute confusion | Delirium | ||

| Professional nursing | Legal issues | Safety | Duty to warn |

| Ethics | Autonomy | Emergency admission | |

| Health promotion | Intervention | Psychopharmacology | |

| Assessment | Mental status exam | ||

| Patient profile | Development | Communication | Autism |

In the psychiatric mental health nursing course, there are two tracks: traditional and blended. The modes of instruction for the traditional track are class, seminar, and clinical. The blended track has an asynchronous online classroom and clinical. Following the selection of core concepts, exemplars, and college credit allotment for this course, faculty began with a few questions: “Is it possible and appropriate to use an active learning strategy when teaching this concept?” “What is the best strategy for teaching this concept?” Faculty desired to apply a teaching strategy best suited to the concept and location of learning rather than rely on assumptions (active is best) or customary strategies (lectures and discussion boards). While active learning promotes integration of knowledge, a lecture-style format has advantages such as control of content, efficiency with large groups, ease of transmitting foundational concepts to beginners, and ease of transfer to an online learning platform. For example, faculty continued to use short lectures for introducing some areas such as psychopharmacology and substance use followed by active learning in seminar and clinical sites with assessment tools such as the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) and Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol, Revised (CIWA-AR) (Sullivan, Sykora, Schneiderman, Naranjo, & Sellers, 1989). The AIMS and CIWA-AR are applied using case studies in seminar and later, patients in clinical.

Integrating concepts across the instructional modes promotes retention and critical thinking as students must apply the initially learned concept in new ways and, most important, with patients. For each mode, detailed outlines and guides provide objectives and learning activities for scheduled learning.

Accordingly, the clinical guide lists weekly objectives and learning activities to help students engage with patients while simultaneously learning the basics of psychiatric nursing. As an example, one clinical objective is to utilize nursing judgment to provide safe, patient-centered care to individuals with complex behavioral health problems across the life span. Clinical placements include a child and adolescent residential behavioral health ranch, a state forensic psychiatric hospital, inpatient hospital psychiatric units, and an opioid treatment facility. The first clinical unit follows the first class with a focus on the mental status exam (MSE). During this class, small student groups view and analyze two different videos depicting course faculty role-playing the nurse performing an admission MSE with a patient with mental illness. In the initial video, the nurse is exhibiting poor practice such as threatening, speaking on phone, and loudly eating gummy bears. Although humorous, students insightfully realize that these practices deter assessment findings and negatively affect the patient. The second video portrays the caring psychiatric nurse expert and highlights acceptance of patients’ presenting problems regardless of how unusual or bizarre. This teaching strategy has the advantage of easy application to the online classroom where students view and analyze the videos at their convenience. Later in the week at clinical, students use information in their clinical guide to discuss vocabulary specific to the MSE in preconference, perform an MSE with a patient, and share their experiences in postconference.

Another example of applying a concept across modes of instruction is psychopharmacology. Students struggle to comprehend the use of medications with numerous indications such as an anticonvulsant for mood stabilization. As such, faculty designed an easy-to-use chart listing the medications under psychiatric classifications with major side effects and life-threatening potential. This reduces the information to essential concepts for the new nurse. For example, one classification is side effects of antipsychotics to illustrate using an anti-Parkinson’s medication to treat side effects of an antipsychotic. The medication chart is in the clinical guide where students refer for understanding their patients’ medications. The basics of psychopharmacology are presented in a lecture in class, which is recorded for the blended track. In seminar, students view videos such as The Pines, the Dones, Two Pips and a Rip (Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharm, 2014) and Movement Disorders (Astra Zenca, 2001) to promote knowledge retention, followed by case study analysis in small groups to promote critical thinking and understanding of noncompliance with psychotropic medications. Additionally, the guide includes the AIMS and a laboratory-testing health assessment worksheet for students to use when caring for patients.

While clinical learning tends to be inherently active, it can be more difficult to create active strategies in the other modes. Thus, when using videos, faculty created Video Watching Guides to move students from passive observer to active participant in learning. For example, the video documentary Grace (Video Press Med School Maryland Productions, 2007) chronicles Glenn for 7 years caring at home for his wife, Grace, who has Alzheimer’s. Students previously responded positively to the film, but faculty noted a lack of fully grasping important nursing considerations. The video guides provide questions for students’ preparation and responses to ensure application of the concepts. An example is, How does Glenn intervene with Grace’s wandering?

Whereas numerous other active teaching strategies are used, the students’ favorite, by far, is the final Psychiatric Nursing Review Game. Faculty believed students needed help applying the individual concepts and exemplars holistically, so a quickly created parody of a TV game show was piloted. With last minute preparation, the game was written on the chalkboard, and the class was divided into two teams. Many different topics were included, such as Nursing Communication and Nursing Interventions. Based on student selection of topic, questions were asked by faculty. For example: Name five verbal or nonverbal ways a patient might communicate impending violence. Initially, faculty had planned to modernize the game but realized the parody added to the fun and focus on learning and technology did not need to be added. With more experience and student feedback, faculty adopted successful strategies to enhance the game, such as inclusion of testable material so students value playing, keep competition mild and lighthearted, offer snacks to students to promote enjoyment and learning, market the game as a course review for the final exam, and be respectful and generous with responses while elaborating on weak answers. Active learning with fun and games brought a collegial culture into class while boosting students’ confidence when they realized they knew the concepts.

Results

Faculty evaluated outcomes from various sources. First, faculty were interested in student evaluation of the effectiveness of the active learning strategies, and these results were mixed and slowly improving as faculty develop more finesse with these techniques. Occasionally, students become frustrated with requirements for active learning and stated, “Just tell me what I need to know to pass the test.” Some students declined to participate in active learning in the classroom setting, and it can be difficult to monitor all the students while also coordinating the activity. Another disadvantage noted by students who are absent is students participating in active learning are not recorded for later publication on the learning platform. This may have the inadvertent effect of encouraging attendance.

Second, faculty evaluated successful completion of clinical and course objectives. The noticeable challenge for students had been select all that apply NCLEX-RN style test questions. Test analyses revealed that only 30% of students were responding correctly to these questions. Numerous practice sample questions (assessment for learning) were created and placed in every unit of learning across all modes of instruction. Students completed the questions as a self-study activity. Faculty observed a high rate of utilization, and students spontaneously referenced the question material in clinical conferences, seminar, class, and individual communications. After implementation, faculty noted that 60% of students correctly answered select all that apply questions on course tests.

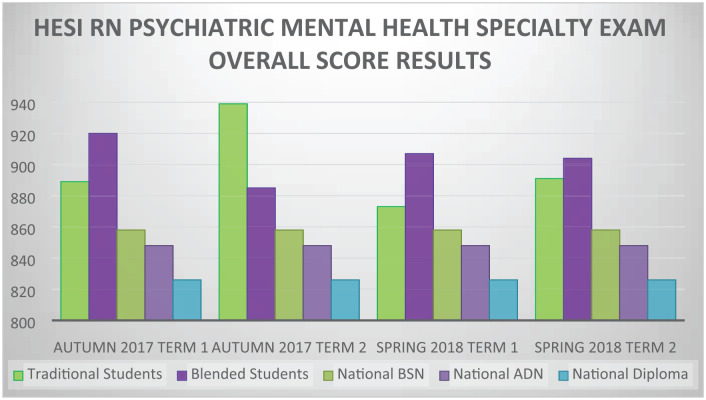

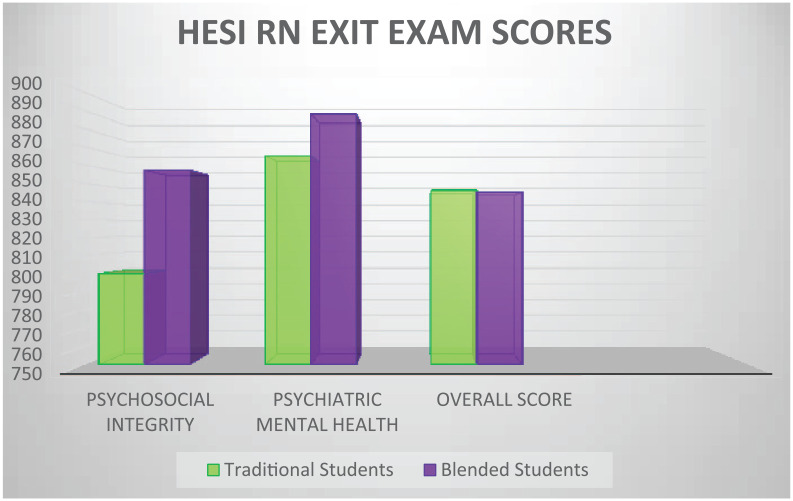

Third, faculty evaluated results and reports from the HESI RN Psychiatric Mental Health Specialty Exam (Elsevier, 2018b) and HESI RN Exit Exam (Elsevier, 2018a). Students take the specialty exam following completion of the course content prior to the final course exam. Course points are earned depending on the specialty exam score in three different ranges. The grade allocation percentage is 15% comparable to the allocation reported by Casarez, Hanks, and Stafford (2018), who found increasing allocation improved scores. Predictive scores have been consistently higher than the national average for diploma, ADN (Associate Degree in Nursing), and BSN (Bachelor of Science in Nursing) nursing students in the United States as noted in Figure 1. Furthermore, after finishing the HESI specialty exam, students value viewing their results and areas for improvement, which has served somewhat as a practice test for the course final exam. Later, in the last semester of the program, students take the HESI exit exam. Faculty were interested to know if the conceptual learning in the mental health course was retained into long-term memory and integrated into their overall knowledge base. Faculty also investigated if the scores on the psychosocial integrity and psychiatric mental health portions of the HESI Exit exam remained above or near the recommended performance as noted in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Comparison of national and course overall score for HESI RN Specialty Psychiatric Mental Health Exam results.

Figure 2.

HESI RN Exit Exam Psychosocial Integrity and Psychiatric Mental Health results for traditional and blended students.

Last, faculty evaluated NCLEX-RN pass rates as well as the reported data regarding content more specifically related to the mental health course. The first cohort of 90 students with the new course design had a 97% overall pass rate.

Conclusions

Faculty embraced the opportunity to use a new curricular plan based on nursing concepts to implement and analyze active teaching strategies that aligned best with the concepts. While this significantly increased active learning, faculty and students found some concepts are better served with lecture-style teaching strategies. Results suggest that the integration of conceptual and active learning in a psychiatric mental health nursing course may increase the likelihood of student success in the course and ultimately on the NCLEX-RN exam.

Footnotes

Author Roles: All three authors conceived, wrote, and reviewed the final manuscript before submitting for publication.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Alison Romanowski  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1717-5515

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1717-5515

References

- Astra Zeneca. (2001). Recognizing extrapyramidal symptoms clinical examples of acute dystonia, akathisia, parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia: Parts 1-4 [YouTube Video]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/zk8AOUAz5bQ

- Baron K. A. (2017). Changing to concept-based curricula: The process for nurse educators. Open Nursing Journal, 11, 277-287. doi: 10.2174/1874434601711010277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarez R. L., Hanks R. G., Stafford L. (2018). Increasing psychiatric mental health nursing HESI grade allocation percentage in a psychiatric nursing course. Journal of Nursing Education, 57, 604-607. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20180921-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsevier. (2018. a). HESI. Retrieved from https://evolve.elsevier.com/education/hesi/

- Elsevier. (2018. b). RN Specialty Exam summary report: Columbus State Community College-ADN. Retrieved from https://hesifacultyaccess.elsevier.com/Reports/ShowSummaryReport

- Giddens J. F. (2017). Concepts for nursing practice (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks S. M., Wangerin V. (2017). Concept-based curriculum: Changing attitudes & overcoming barriers. Nurse Educator, 42, 138-142. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y., Azaiza K., Salani D. (2017). Flipping the classroom without flipping out the students: Working with an instructional designer in an undergraduate evidence-based nursing practice course. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 18(1), 17-27. doi: 10.4127/2167-1168.C1.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuroscience Education Institute Psychopharm. (2014). The pines, the dones, two pips and a rip [YouTube Video]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/kuYGJOcloH8

- Sullivan J. T., Sykora K., Schneiderman J., Naranjo C. A., Sellers E. M. (1989). Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The Revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale (CIWA-AR). British Journal of Addiction, 84, 1353-1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Video Press Med School Maryland Productions. (2007). Grace. Retrieved from videopressumd.org [Google Scholar]

- Waltz C. F., Jenkins L. S., Han N. (2014). The use & effectiveness of active learning methods in nursing and health professions education: A literature review. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36, 392-400. doi: 10.5480/13-1168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]