Abstract

Children investigated for maltreatment are particularly vulnerable to experiencing multiple adversities. Few studies have examined the extent to which experiences of adversity and different types of maltreatment co-occur in this most vulnerable population of children. Understanding the complex nature of childhood adversity may inform the enhanced tailoring of practices to better meet the needs of maltreated children. Using cross-sectional data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being II (N = 5870), this study employed latent class analysis to identify subgroups of children who had experienced multiple forms of maltreatment and associated adversities among four developmental stages: birth to 23 months (infants), 2–5 (preschool age), 6–10 (school age), and 11–18 years-old (adolescents). Three latent classes were identified for infants, preschool-aged children, and adolescents, and four latent classes were identified for school-aged children. Among infants, the groups were characterized by experiences of (1) physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently, (2) physical neglect/household dysfunction, and (3) caregiver divorce. For preschool-aged children, the groups included (1) physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently, (2) physical neglect/household dysfunction, and (3) emotional abuse. Children in the school-age group clustered based on experiencing (1) physical neglect/emotional neglect and abuse/caregiver treated violently, (2) physical neglect/household dysfunction, (3) emotional abuse, and (4) emotional abuse/caregiver divorce. Finally, adolescents were grouped based on (1) physical neglect/emotional abuse/household dysfunction, (2) physical abuse/emotional abuse/household dysfunction, and (3) emotional abuse/caregiver divorce. The results indicate distinct classes of adversity experienced among children investigated for child maltreatment, with both stability across developmental periods and unique age-related vulnerabilities. Implications for practice and future research are discussed.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Child welfare, Latent class analysis, National survey of child and adolescent well-being

1. Introduction

In 2015, an estimated four million referrals were made to child protective service agencies in the United States (Children’s Bureau, 2017). Of these, 2.2 million referrals were screened in, resulting in a child protection investigation (Children’s Bureau, 2017). Although the majority of cases involved neglect (75.3%) and physical abuse (17.2%; Children’s Bureau, 2017), child maltreatment takes many forms that often co-occur. In addition to abuse and neglect, other experiences of adversity – such as exposure to caregiver mental illness, substance use, or domestic violence (and perhaps especially the number of such early adverse experiences) – place children at increased risk for maltreatment and compromise their safety and well-being (Brown, Cohen, Johnson, & Salzinger, 1998; McGuigan & Pratt, 2001; Walsh, MacMillan, & Jamieson, 2003). Further, exposures to these adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998) are well established in the literature as having significant negative consequences on children’s developmental (Kerker et al., 2015), physical (Flaherty et al., 2006), and mental (Clarkson-Freeman, 2014) health, as well as having lasting impacts on health and risk-taking behavior into adulthood (Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles, & Anda, 2003; Felitti et al., 1998).

Research on child maltreatment has generally focused on specific types of abuse or neglect and their influence on children’s health and well-being. This limited focus may result in an overestimation of the impact of individual types of abuse or neglect (Armour, Elklit, & Christoffersen, 2014) and overlook the possibility that maltreatment types may overlap and together affect children to a greater magnitude (Higgins & McCabe, 2001). With the burgeoning research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and evolving understanding that the cumulative nature of childhood adversity may exacerbate the risk of poor outcomes, it is important to further investigate the complexity of child maltreatment as a construct involving multiple forms of co-occurring maltreatment experiences that may interact with other adverse experiences, and which may differ based on children’s developmental stage. Efforts to understand the complex experiences of children by including family-level adverse factors may, in turn, better elucidate opportunities for prevention and early treatment. For example, divorce, parental mental illness, and parental substance abuse are not maltreatment incidences alone, but have been included in the ACE research over the past two decades and are linked with a host of negative outcomes, suggesting these are important factors to consider in service planning and intervention.

Some advancement in understanding child maltreatment according to the co-occurrence of types of adversity has been made (Armour et al., 2014). However, as reviewed in Higgins and McCabe (2001), most research has focused on the co-occurrence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse as well as of physical and supervisory neglect. For example, Bolger and Patterson (2001) used a variable-centered analytic approach (factor analysis), to examine the co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment according to maltreatment severity. Findings indicated a three-factor solution: a sexual abuse factor, a physical and supervisory neglect factor, and a physical and emotional abuse factor (Bolger & Patterson, 2001). Importantly, research centered on ACEs – the specific accumulation of ten childhood experiences – does not take into account severity or frequency of the specific ACE events, and yet is predictive of numerous adult and child outcomes reflecting a cumulative risk model (Lanier, Maguire-Jack, Lombardi, Frey, & Rose, 2017). Yet research also points to the importance of particular ACE combinations (Lanier et al., 2017), leaving unanswered questions about the best empirically-based method to identify children at risk.

In an attempt to better understand individual and complex experiences of child maltreatment, several researchers have moved beyond variable-centered analytic methods (i.e., examining relationships among variables), to using person-centered analytic techniques, such as latent class analysis or latent profile analysis, that allow for the classification of individuals into mutually exclusive classes based on reported experiences of maltreatment (Roesch, Villodas, & Villodas, 2010). For example, Nooner et al. (2010) queried 795 youth regarding their experiences of physical and sexual abuse and identified four classes of youth according to their abuse histories. These classes included: youth who experienced no physical or sexual abuse; high physical abuse and low sexual abuse; no physical abuse and moderate sexual abuse; and high physical abuse and high sexual abuse (Nooner et al., 2010). Similarly, Pears, Kim, and Fisher (2008) used latent profile analysis to identify subgroups of children who had experienced maltreatment, also finding four profiles: supervisory neglect and emotional maltreatment; sexual abuse, emotional maltreatment, and neglect; physical abuse, emotional maltreatment, and neglect; and sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional maltreatment, and neglect (Pears et al., 2008). Findings from these studies demonstrate that maltreatment types may co-occur; and distinct classes of maltreatment among children exist, which may, in turn, inform intervention efforts that aim to meet the unique and heterogeneous needs of children affected by early adversity. Indeed, specific ACE combinations have been found predictive of child health, leading to questions about whether children with particular co-occurring ACEs should be triaged and prioritized for services, although there are questions as to what services are appropriate based on the evidence-base and current status of ACE science (Finkelhor, 2017; Lanier et al., 2017).

These investigations of maltreatment subtypes and co-occurrence have importantly contributed to the field of child maltreatment research. Yet, less research has focused on how broad experiences of adversity typically experienced by children with child welfare involvement co-occur at different developmental stages. One known study used factor analysis to examine the co-occurrence of different types of ACEs among children and adolescents (Scott, Burke, Weems, Hellman, & Carrión, 2013). The authors reported a three-factor solution that grouped items into categories of abuse, household dysfunction, and mixed adversity (Scott et al., 2013). Although this study contributes to our understanding of how early adverse experiences are interrelated, the variable-centered methodology used does not allow for children and adolescents to be grouped into discrete classes based on shared experiences, thereby limiting our understanding of the multiple dimensions of children’s exposure to maltreatment and associated adversity. Our study aimed to expand the literature on childhood adversity by exploring the complex adverse experiences of children investigated for child maltreatment based on their developmental stages. Specifically, we used latent class analysis to identify the co-occurrence of adverse events experienced by children whose families were investigated by child protective services. Using cross-sectional data, analyses were conducted separately for children in each of four developmental groups: birth to 23 months (infants), ages 2–5 years (preschool age), ages 6–10 years (school age), and ages 11–18 years (adolescents) because these represent developmentally distinct periods where both adverse experiences and appropriate intervention and treatment approaches may differ.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and procedures

The sample for this study included 5870 children, ages birth to 18 years, investigated for child maltreatment. Data were collected in the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Wellbeing II (NSCAW II), a national, longitudinal, multi-informant study of children in contact with child welfare services, including both substantiated (maltreatment was found) and unsubstantiated (maltreatment was not indicated) cases (Dowd et al., 2014). A two-stage stratified sampling design was used to create a sample that is representative of child-welfare-involved children across the country (see Dowd et al., 2014 for more information). This study utilizes baseline data from caregivers, children/adolescents, and caseworkers collected between March 2008 and September 2009.

To examine developmental differences in the co-occurrence of ACEs, we divided the sample into four groups based on developmental science (see “Child Development Institute, ” n.d.) regarding ages that correspond to infancy, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence, with some adjustments made according to the measures available for each developmental stage in the NSCAW study. See below for descriptive demographic information for each developmental group.

Infants (birth to 23 months): of the 2608 infants in the sample, 51.6% were male and the average age was 8.95 months (SD = 5.05). Approximately 30% were identified as Hispanic, 29% each were identified as White and Black/African American, while another 11% were identified as multi-racial or other.

Preschool age (2–5 years old): Of the 1157 preschool-age children in the sample, 55.1% were male and the average age was 3.87 years (SD = 1.15). Approximately 25% were identified as Hispanic, 41% as White, 26% as Black/African American, and 9% as multi-racial or other.

School age (6–10 years old): Of the 1052 elementary school-age children in the sample, 53.3% were male and the average age was 8.38 years (SD = 1.42). Approximately 27% were identified as Hispanic, 39% as White, 24% as Black/African American, and 10% as multi-racial or other.

Adolescents (11–18 years old): Of the 1053 adolescents in the sample, 44.6% were male and the average age was 14.15 years (SD = 1.85). Approximately 26% were identified as Hispanic, 40% as White, 25% as Black/African American, and 10% as multi-racial or other.

2.2. Human subjects

The NSCAW II dataset is maintained and licensed by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN). All analyses were conducted by investigators who are licensed users of the NSCAW II dataset, have human subjects’ certification, and received approval from the host institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) to conduct secondary data analysis of the NSCAW II data.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Adverse childhood experiences

The variables used as dichotomous indicators of ACEs were created by investigators in the NSCAW study to match as closely as possible to the ten ACEs used in the original ACEs study (Stambaugh et al., 2013). Because the NSCAW was not designed to assess for ACEs, development of this construct relied on information collected from multiple reporters. When children were not old enough to complete self-report assessments, caseworker and caregiver reports were also used. Specifically, caseworker reports of each ACE are dichotomous (yes/no) based on a risk assessment at the time of the investigation. Caregiver reports are largely taken from standardized measures such as the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 and Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-form (CIDI) measure of depression, though some are based on demographic information or questions developed for the study (e.g., relationship status or incarceration status). A full list of measures is publicly available (Kerker et al., 2015), and additional detail is provided by Stambaugh et al. (2013). When there were multiple reporters for a given ACE, the participant received a score of “1” indicating that the ACE occurred if any source (child, caseworker, or caregiver) reported exposure to that ACE. In the current study, ACEs include: (1) physical neglect: failure to supervise or provide for the child (caregiver or caseworker report); (2) emotional neglect: caregiver unable to express affection or love for the child due to personal problems (caregiver report); (3) physical abuse: severe assault or physical abuse, such as shaking or hitting (caregiver or caseworker report); (4) sexual abuse: child experienced sexual abuse or forced sex (caregiver or caseworker report; child self-report for ages 11–18); (5) emotional abuse: caregiver engaged in psychological aggression toward child, such as threatening or name-calling (caregiver report); (6) caregiver treated violently: domestic violence of an adult in the home, including slapping, hitting, or kicking (caregiver or caseworker report); (7) caregiver substance abuse: active alcohol or drug abuse by a caregiver (caregiver or caseworker report); (8) caregiver mental illness: serious mental illness or elevated mental health symptoms (caregiver or caseworker report); (9) caregiver divorce/family separation: child’s parent(s) deceased, separated, or divorced; or child was abandoned or placed in out-of-home care (caregiver or caseworker report); and (10) caregiver incarceration: caregiver spent time in prison or is currently in a jail or detention center (caregiver report).

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to examine sample characteristics as well as the proportion of children with adverse childhood experiences for each developmental stage. Latent class analyses were conducted for each group using Mplus (version 6) (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 – Muthén & Muthén, 2010). All ten dichotomous ACEs were included in the model to allow classification into subgroups of children who experienced co-occurring early adversities. All models were estimated in two stages using maximum likelihood methods. In the initial stage, 100 random sets of starting values were generated and 50 optimizations were carried out. In addition, 20 iterations were specified at the initial stage. A final solution was accepted only if the solution replicated at least seven times. For BLRT p values, (Tech14) LRTSTARTS option was used, which specified that for the k-1 class model, 40 random sets of starting values were used in the initial stage and 10 optimizations were carried out in the final stage; and for the k class model 200 random sets of starting values were used in the initial stage and 100 optimizations were carried out in the final stage. To determine the best fitted model, an iterative process was employed evaluating estimates from models that included from 2 to 4 specified classes. The optimal class solution was selected based on several fit indices and decision points, including: 1) smaller Akaike information criterion values for the k class model relative to the k-1 class model (AIC; Akaike, 1987); 2) smaller sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion values for the k class model relative to the k-1 class model (Adjusted BIC; Sclove, 1987); 3) significance values for the k class model were compared to those of the k-1 class model for the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001); 4) significance values for the k class model were compared to those of the k-1 class model for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007); 5) classes contained more than 5% of the total sample; 6) classes were theoretically meaningful; and 7) results were interpretable.

3. Results

3.1. Proportion of children with adverse childhood experiences for each developmental stage

For all developmental groups, the proportion of children experiencing each ACE tended to be moderate to high. As indicated in Table 1, the average number of ACEs among infants was 2.95 (SD = 1.49). The most common ACE for infants was caregiver divorce or separation, experienced by over 60% of the sample (.63), followed by caregiver substance abuse (.57), caregiver treated violently (.47), and physical neglect (.46). For preschool-aged children, the average number of ACEs was 3.50 (SD = 1.59). The most common ACE for preschool-aged children was emotional abuse (.65), followed by caregiver divorce or separation (.54), physical neglect (.53), and caregiver treated violently (.50). The average number of ACEs among school-aged children was 3.50 (SD = 1.61). School-aged children were most likely to have experienced emotional abuse (.70), caregiver divorce or separation (.59), physical neglect (.53), and caregiver treated violently (.41). For adolescents, the average number of ACEs was 4.15 (SD = 1.73). The most common ACEs for adolescents included emotional abuse (.87), caregiver divorce or separation (.65), physical neglect (.56), and physical abuse (.51).

Table 1.

Proportion of Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences for Each Developmental Stage.

| Infants n = 2608 | Preschool Age n = 1157 | School Age n = 1052 | Adolescents n = 1053 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | ||||

| Physical Neglect | .46 | .53 | .53 | .56 |

| Emotional Neglect | .05 | .10 | .15 | .24 |

| Physical Abuse | .17 | .25 | .29 | .51 |

| Sexual Abuse | .02 | .09 | .15 | .26 |

| Emotional Abuse | .19 | .65 | .70 | .87 |

| Caregiver Treated Violently | .47 | .50 | .41 | .40 |

| Caregiver Substance Abuse | .57 | .42 | .35 | .31 |

| Caregiver Mental Illness | .40 | .40 | .34 | .41 |

| Caregiver Divorce/Separation | .63 | .54 | .59 | .65 |

| Caregiver Incarceration | .14 | .14 | .12 | .11 |

| Total ACEs | M(SD) | |||

| 2.95(1.49) | 3.50(1.59) | 3.50(1.61) | 4.15(1.73) |

3.2. Latent classes of adverse childhood experiences

For infants, preschool-aged children, and adolescents, the three-class solution was determined to be the best fitting model, and for school-aged children, the four-class solution was determined to be the best fitting model based on the various fit indices and selection criteria (see Table 2). Although the four-class solution for infants also had good fit indices, too few infants (less than 5% of the sample) were placed into the fourth class, which can result in less reliable estimates of class-specific parameters and decreases substantive meaning of the latent class. It is suggested that the BIC is the most reliable indicator for class selection, with lower values indicating better fit (Nylund et al., 2007); however, the BIC values did not differ greatly across models in any developmental group. In addition, although both the LMR and the BLRT methods are able to distinguish between class models (Nylund et al., 2007), BLRT significance values also did not differ across models in any developmental group. Therefore, the tests of significance for the LMR adjusted likelihood ratio statistics were compared to help determine the best-fitting models.

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Latent Class Models 2–4 for Each Developmental Stage.

| Infants | Preschool Age | School Age | Adolescents | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Model Fit Indices | ||||||||||||

| Log-likelihood | −12116.95 | −12014.35 | −11963.82 | −6148.84 | −6072.94 | −6044.36 | − 5667.65 | −5593.50 | −5543.89 | −5652.38 | −5612.56 | −5572.25 |

| Entropy | .55 | .44 | .52 | .64 | .60 | .61 | .79 | .63 | .65 | .68 | .69 | .68 |

| AIC | 24275.89 | 24092.70 | 23993.63 | 12339.68 | 12209.89 | 12174.73 | 11377.30 | 11250.99 | 11173.72 | 11346.76 | 11289.12 | 11230.49 |

| Adjusted BIC | 24332.36 | 24178.75 | 24109.26 | 12379.11 | 12269.96 | 12255.45 | 11414.73 | 11409.66 | 11250.36 | 11384.21 | 11346.18 | 11307.17 |

| LMR p-value | < .001 | .078 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | .275 | < .001 | < .001 | .023 | < .001 | .008 | .257 |

| BLRT p-value | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Class size | 567, 2041 | 593, 885, 1130 | 122, 599, 754, 1133 | 483, 674 | 250, 293, 614 | 332, 198, 309, 318 | 118, 934 | 315, 125, 612 | 119, 324, 333, 276 | 252, 801 | 491, 267, 295 | 398, 315, 244, 96 |

Note: AIC =Akaike information criterion; Adjusted BIC = sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR= Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test; BLRT = bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

Given that this sample included a highly vulnerable population (specifically, children investigated for maltreatment), all of the classes included children who had experienced one or more ACEs. With regard to infants, class 1 comprised 23% (n = 593) of the infant sample, while 34% (n = 885) were placed in class 2, and 43% (n = 1130) in class 3 (see Fig. 1). The first class included a high proportion of infants who were likely to experience physical neglect (.61), emotional abuse (.59), and caregivers who were treated violently (.66), thus labeled the physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently class. Class 2, characterized as the physical neglect/household dysfunction class, included infants who were likely to experience physical neglect (.57) in addition to caregivers who were treated violently (.63), caregiver substance abuse (.73), caregiver mental illness (.64), and caregiver divorce (.89). Although infants in class 3 were relatively less likely to experience multiple ACEs compared to their counterparts in classes 1 and 2, a high proportion of infants in this class were likely to experience caregiver divorce (.64), therefore labeled the caregiver divorce class.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of infants with adverse childhood experiences for the three-class solution.

Note: CG = Caregiver. Class 1 = physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently; Class 2 = physical neglect/household dysfunction; Class 3 = caregiver divorce.

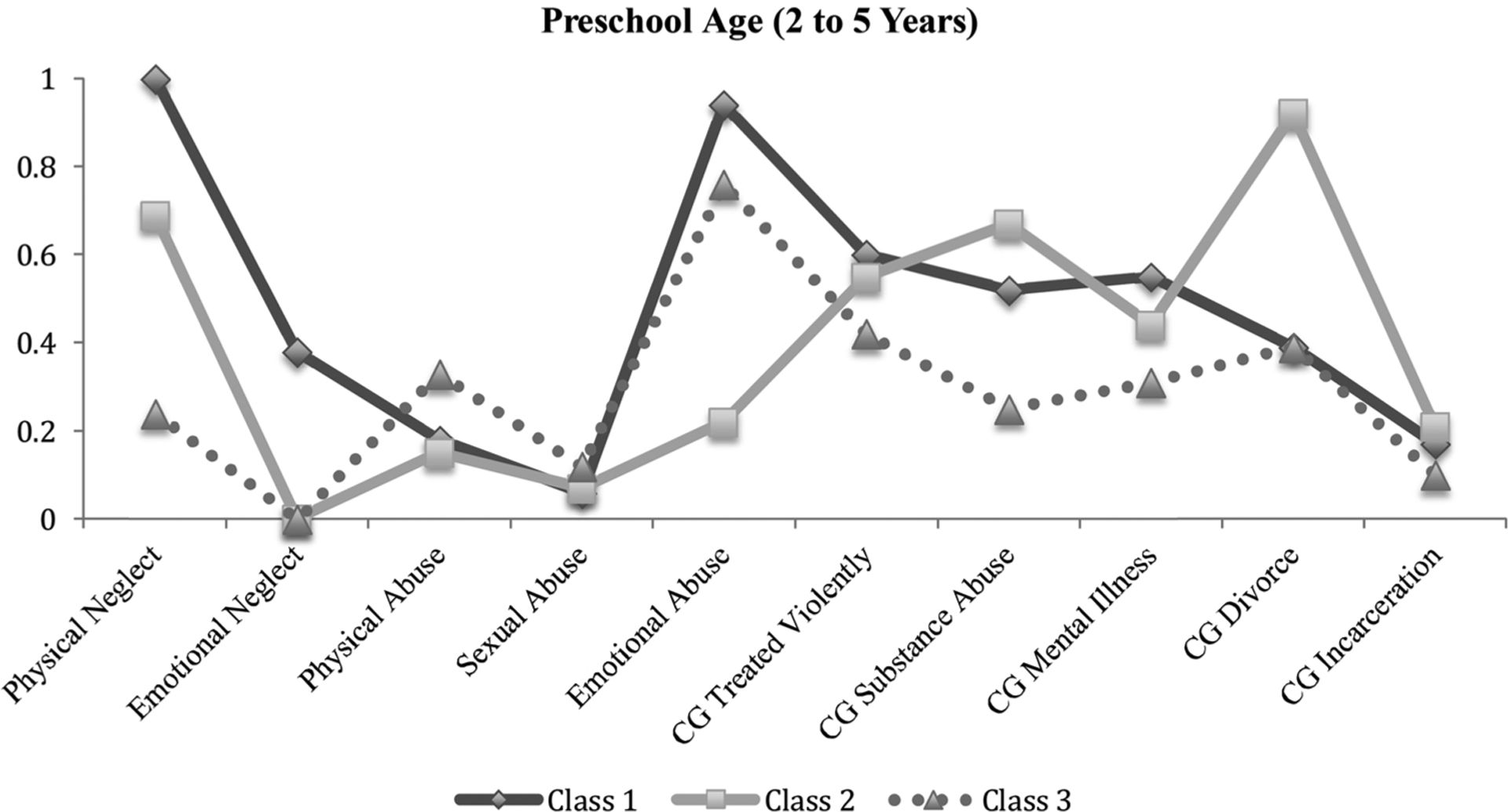

For preschool-aged children, 22% (n = 250) were classified into class 1, 25% (n = 293) were classified into class 2, and 53% (n = 614) were classified into class 3 (see Fig. 2). Preschool-aged children in class 1 were likely to experience physical neglect (1.00), emotional abuse (.94), and caregivers who were treated violently (.60). As with infant class 1, this class was identified as the physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently class. The second class included preschool-aged children who were likely to experience physical neglect (.69), caregivers who were treated violently (.55), caregiver substance abuse (.67), caregiver divorce (.92), and caregiver mental illness (.44). This is referred to as the physical neglect/household dysfunction class. The third class for this developmental group was primarily characterized by the proportion of children who were likely to experience emotional abuse (.76); thus named the emotional abuse class.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of preschool-aged children with adverse childhood experiences for the three-class solution.

Note: CG = Caregiver. Class 1 = physical neglect/emotional abuse/caregiver treated violently; Class 2 = physical neglect/household dysfunction; Class 3 = emotional abuse.

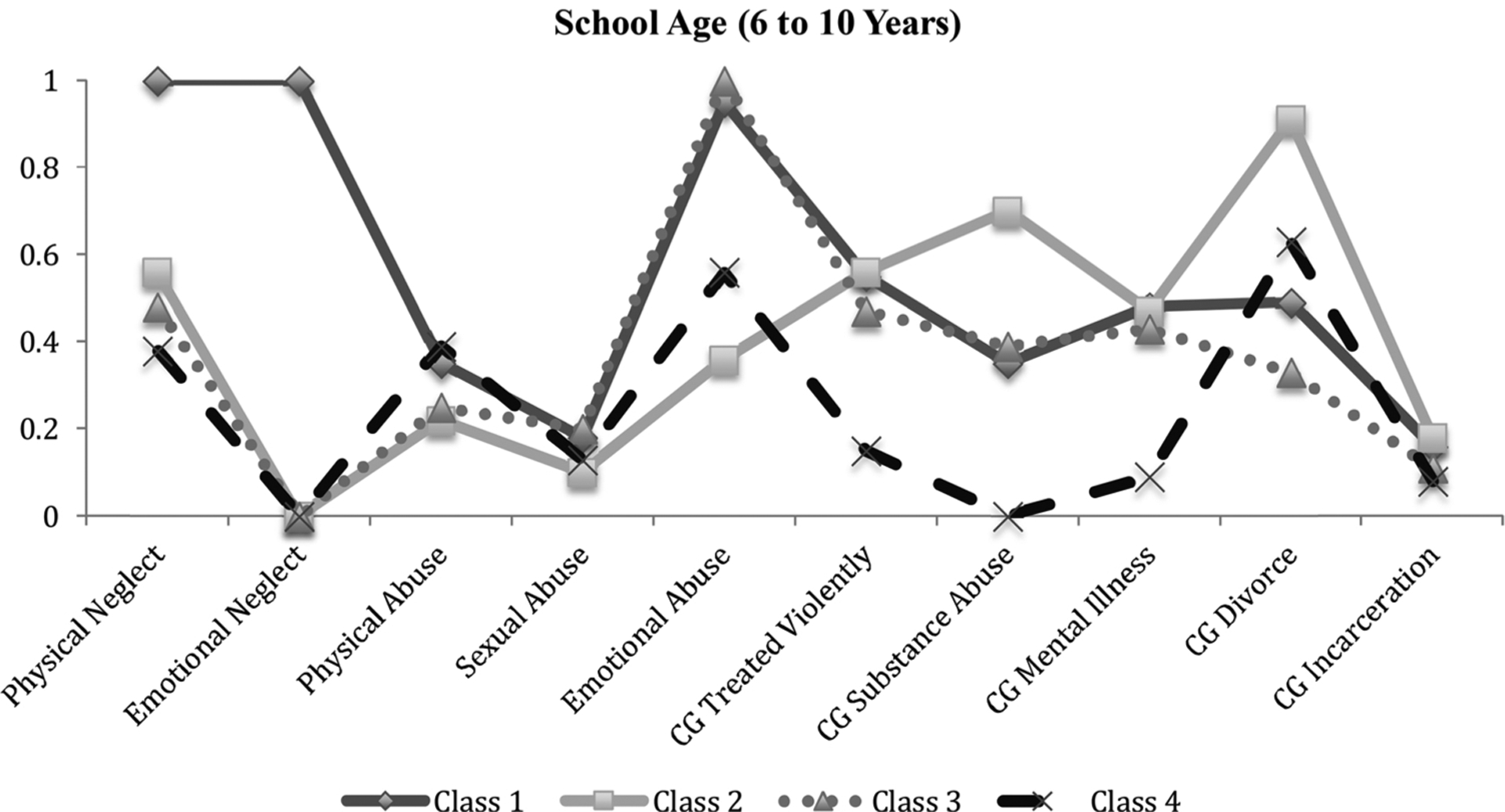

Of the school-aged children, 11% (n = 119) were classified into class 1, 26% (n = 276) were classified into class 2, 31% (n = 324) were classified into class 3, and 32% (n = 333) were classified into class 4 (see Fig. 3). The first class was characterized as the physical neglect/emotional neglect and abuse/caregiver treated violently class. Specifically, the proportion of children who were likely to experience physical and emotional neglect was 1.00, while the proportion was .95 for emotional abuse and .55 for caregivers who were treated violently. The second class included school-aged children who were likely to experience physical neglect (.56) and household dysfunction, including caregivers who were treated violently (.56), caregiver substance abuse (.70), caregiver mental illness (.47), and caregiver divorce (.91). This was identified as the physical neglect/household dysfunction class. School-aged children in the third class, the emotional abuse class, primarily included those who were likely to experience emotional abuse (1.00). The fourth class included school-aged children who were likely to experience both emotional abuse (.56) and caregiver divorce (.63), therefore labeled the emotional abuse/caregiver divorce class.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of school-aged children with adverse childhood experiences for the four-class solution.

Note: CG = Caregiver. Class 1 = physical neglect/emotional neglect and abuse/caregiver treated violently; Class 2 = physical neglect/household dysfunction; Class 3 = emotional abuse; Class 4 = emotional abuse/caregiver divorce.

The greatest number of adolescents were classified into class 1 (47%; n = 491), while 25% (n = 267) were classified into class 2, and 28% (n = 295) into class 3 (see Fig. 4). Class 1 included adolescents who were likely to experience physical neglect (1.00), emotional abuse (.92), caregivers who were treated violently (.49), caregiver substance abuse (.43), caregiver mental illness (.56), and caregiver divorce (.63). This class is called the physical neglect/emotional abuse/household dysfunction class. The second class was similar to class 1 and included relatively high proportions of adolescents who were likely to experience emotional abuse (.90), caregivers who were treated violently (.58), caregiver substance abuse (.35), caregiver mental illness (.47), and caregiver divorce (.64), but the primary difference from class 1 being the proportion of adolescents who experienced physical abuse (.62). This class was therefore characterized as the physical abuse/emotional abuse/household dysfunction class. The third class was labeled the emotional abuse/caregiver divorce class, as higher proportions of adolescents were likely to experience both emotional abuse (.77) and caregiver divorce (.69).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of adolescents with adverse childhood experiences for the three-class solution.

Note: CG = Caregiver. Class 1 = physical neglect/emotional abuse/household dysfunction; Class 2 = physical abuse/emotional abuse/household dysfunction; Class 3 = emotional abuse/caregiver divorce.

4. Discussion

Consistent with previous research (e.g., Pears et al., 2008), we found that children in this sample experienced multiple forms of maltreatment in addition to other forms of early adversity.

At each developmental stage, there was some stability of latent classes. Class 1 (physical neglect, emotional abuse, caregivers who were treated violently) included the same core ACEs for infants and preschool-aged children. For school-aged children, along with these ACEs, class 1 also included elevated exposure to emotional neglect.

Core ACEs included in class 2 (physical neglect and household dysfunction) were the same for infants, preschool-aged children, and school-aged children. Although the experience of physical neglect was most likely for children in class 1, likelihood of exposure was still quite elevated for children in class 2, with approximately 50%–60% of infants, preschool-aged children, and school-aged children exposed. Distinct from class 1, however, class 2 was also characterized by very high likelihood of exposure to caregiver substance abuse, mental illness, and divorce.

Class structure differed for adolescents, with generally higher proportions of adolescents in class 1 and class 2 experiencing multiple ACEs and higher likelihood of physical neglect (class 1) and physical abuse (class 2), whereas class 3 was similar to school-aged children and characterized by high likelihood of exposure to emotional abuse and caregiver divorce. Given that the adolescent group is older, the higher co-occurrence of ACEs for this group may be due to the increased likelihood of exposure to multiple types of adversities with age.

Across developmental groups, children tended to cluster based on exposure to three general groupings of ACEs. First, it appeared that physical neglect, emotional abuse, and caregivers who were treated violently co-occurred – a finding that is somewhat unsurprising, given past research demonstrating the link between the presence of domestic violence and increased risk of child maltreatment (e.g., O’Leary, Slep, & O’Leary, 2000) and high overlap between emotional maltreatment and other forms of maltreatment, particularly physical abuse and neglect (English, Thompson, White, & Wilson, 2015). Second, similar to others’ findings related to family violence and the cumulative risk posed by broad household dysfunction (Shipman, Rossman, & West, 1999), children and adolescents in this study tended to cluster in classes where risk of being exposed to multiple forms of family dysfunction was present. Finally, emotional abuse and caregiver divorce co-occurred in this sample, and though the underlying reasons are not known, the vast literature on the association between divorce and adult well-being (e.g., Amato, 2014) may shed some light on root causes of emotional abuse directed toward children. The relevance of divorce as a co-occurring characteristic with other adversities including parental mental illness and substance abuse in class 2 is striking because divorce is not a referral characteristic to child protective services nor a typical service focus for child welfare-involved families, yet has been shown to exert unique influences on adult functioning, particularly stress responsivity, relational attachment, and emotional expression and regulation (Boccia, 2017). Similarly, emotional abuse and neglect are relatively common and known to be associated with poorer outcomes regarding child functioning (Glaser, 2011), yet rarely receive the warranted attention in child protective and/or service provision contexts.

For adolescents aged 11–18 in particular, multiple ACEs are likely to co-occur. In contrast to previous work using person-centered approaches (e.g., Armour et al., 2014), sexual abuse did not differentiate a class in any developmental group. Notably, sexual abuse was reported at much lower frequency than were other ACEs. Even among adolescents aged 11–18 where reported sexual abuse exposure rates were approximately 30% of the sample, exposure did not differentiate classes, while physical neglect and household dysfunction did differ substantially between classes. Prior research indicates that sexual abuse co-occurs with other family-level risk factors, including domestic violence and substance use (Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003; Kellogg & Menard, 2003; McCrae, Chapman, & Christ, 2006). However, in the context of child protective services, sexual abuse is often perceived as particularly harmful to children and it is common practice to classify children based on the primary type of maltreatment experienced (McCrae et al., 2006); therefore, consistent identification of other family-level stressors may be overlooked. It is likely that sexual abuse co-occurs with other salient risk factors in our sample, but multiply-exposed children and adolescents were not uniquely classified due to a wide variability in reporting of their early adverse experiences.

4.1. Limitations

The current study has some limitations. Although certain ACEs were derived from multiple reporters (i.e., child, caregiver, caseworker), self-reporting may result in under- or over- estimating experiences, particularly in the context of early adversity. Prior research suggests that informants may differ in their reports of adverse-event experiences and the severity of these experiences (e.g., Lewis et al., 2010; Litrownik, Newton, Hunter, English, & Everson, 2003). Thus, it is possible that the classifications of children and adolescents not only reflect differences in the types of adverse experiences, but also reflect differences in who reported those experiences. Future research would benefit from examining whether reliance on multiple reporters for each ACE for classifying children and adolescents who experience co-occurring adversities influences results, perhaps by modeling the covariance between multiple reporters. Future research may also benefit from examining the severity of adversity in relation to class membership instead of using dichotomous indicators of adversity.

The current study also focused on examining how common ACEs co-occur among children investigated for maltreatment without inclusion of possible confounders and correlates of adversity. Therefore, it is possible that classes of children may differ according to diverse subpopulations within the child welfare system. Finally, as this was a population investigated for child maltreatment, the co-occurrence of early adversities may look different in this sample compared to children whose families have not been investigated for maltreatment. Future research should explore ACE class membership within samples of children who have diverse backgrounds and experiences.

4.2. Implications

Understanding common risk constellations by developmental stage provides several possible implications for practice. First, this information could be used to increase thorough screening for risks not evident in initial maltreatment reports. Relatedly, training of crisis and investigation personnel regarding these potentially co-occurring risks might help inform and support additional services, particularly when maltreatment co-occurs with violence toward caregivers as in class 1 for infants and preschool-aged children or when caregiver mental illness, substance abuse, and divorce co-occur as happens at multiple age groups. Notably, emotional abuse often co-occurs with caregiver divorce and direct attention to this risk could be incorporated into child welfare state-level requirements when caregivers of children file for divorce (e.g., as part of required parenting classes). Further, while evidence from many studies including this one supports family-level intervention, these data suggest that approaches which tackle these constellations of family-level factors in unison may have more substantial and long-lasting benefits. In addition, future research would benefit from using person-centered analyses to examine how experiences of multiple forms of childhood adversity group together within children in order to offer a better prediction of children’s and adolescents’ later outcomes. Finally, these data identify broad exposure to multiple and differing ACEs for adolescents aged 11–18. This broad exposure may have compounding cumulative effects, with adversities co-occurring at high rates and also limiting exposure to more positive experiences. These alarming rates of exposure to ACEs make a compelling argument for both targeting multiply-exposed adolescents with programming that builds core skills and capacities and addressing the structural inequities that have left their families and communities vulnerable.

At each developmental stage, one class of children emerged who were exposed to compound risks. This highlights the heterogeneity of child welfare investigated families, and that approximately one third of investigated families across development are exposed to multiple risk factors. The ACE framework is a cumulative risk index with both reported dose-response effects for poor health outcomes (increasing health risk for each additional ACE), and important thresholds, with four or more ACEs associated with dramatically increased risk of a number of chronic health conditions (Felitti et al., 1998) and six or more ACEs associated with a 20-year lifespan reduction (Brown et al., 2009). These data from a national sample of children investigated by child welfare indicates that about one-third of this population may be at similar risk of poor health outcomes. Therefore, this subsample of children warrants careful attention and likely necessitates intensive services.

Exposure to caregiver violence was also commonly reported across developmental groups. Even in infancy, children exposed to higher adult conflict show heightened neural responsiveness to angry adult voices (Graham, Fisher, & Pfeifer, 2013), and similar findings during childhood have revealed that maltreated children are faster to notice when adult faces change from neutral to negative (Pollak, Cicchetti, Hornung, & Reed, 2000). While this heightened sensitivity to adult danger cues is likely protective for children at risk for maltreatment, this type of restructuring of brain architecture may deflect resources from other important developmental activities.

Although this study focused on risk groups, effective prevention and intervention would greatly benefit from identification and promotion of protective factors within families and communities experiencing individual or multiple adversities. Indeed, the toxic stress framework proposed by Shonkoff, Bruce, and McEwen (2009) differentiates toxic from tolerable stress primarily based on the presence of buffering adult relationships that can protect children exposed to significant events from stress-related illness and related changes to neurodevelopment. Unraveling complex interconnected adversities by building from core family and community strengths, for example by identifying salient relationships, may help to prevent repeated exposures and to reduce the intergenerational transmission of ACEs.

5. Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates that using person-centered analytic methods can help to identify distinct classes of adversity experienced among children investigated for child maltreatment. Findings from the present study indicate that these classes may remain somewhat stable across developmental stages, but unique age-related vulnerabilities are also evident. This classification of children into groups based on experiences of adversity not only offers insight into the complex nature of early adverse-event exposure, but also may inform improvements in practices that address the unique needs of vulnerable children and their families.

References

- Akaike H (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52, 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Amato P (2014). The consequences of divorce for adults and children: An update. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 23(1), 5–24. 10.5559/di.23.1.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Elklit A, & Christoffersen MN (2014). A latent class analysis of childhood maltreatment: Identifying abuse typologies. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19, 23–39. 10.1080/15325024.2012.734205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia ML (2017). Parental divorce effects on adult social relationships: Neurobiological linkages. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Council on Family Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, & Patterson CJ (2001). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development, 72(2), 549–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, & Salzinger Z (1998). A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatment: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11), 1065–1078. 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, … Giles WH (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 389–396. 10.1016/j.ampepre.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Development Institute (n.d.). Child development ages & stages. Retrieved from: https://childdevelopmentinfo.com/ages-stages/#.WCtKjsn0aVF.

- Children’s Bureau (2017). Child maltreatment 2015. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Clarkson-Freeman PA (2014). Prevalence and relationship between adverse childhood experiences and child behavior among young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 544–554. 10.1002/imhj.21460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Dube SR, Giles WH, & Felitti VJ (2003). The relationship of exposure to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 625–639. 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd K, Dolan M, Smith K, Day O, Kenney J, Wheeless S, & Biemer P (2014). National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW II), combined waves 1–3, restricted release version, data file user’s manual. Ithaca, NY: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Giles WH, & Anda RF (2003). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1990. Preventive Medicine, 37, 268–277. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Thompson R, White CR, & Wilson D (2015). Why should child welfare pay more attention to emotional maltreatment? Children and Youth Services Review, 50, 53–63. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D (2017). Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Cautions and suggestions. Child Abuse & Neglect [Advanced online publication. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.016]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Theodore A, English DJ, Black MM, & Dubowitz H (2006). Effect of early childhood adversity on child health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 160, 1232–1238. 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser D (2011). How to deal with emotional abuse and neglect—Further development of a conceptual framework (FRAMEA). Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 866–875. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AM, Fisher PA, & Pfeifer JH (2013). What sleeping babies hear: An fMRI study of interparental conflict and infants’ emotion processing. Psychological Science, 24(5), 782–789. 10.1177/0956797612458803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, & McCabe MP (2001). Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6, 547–578 [10.1016.S1359-1789(00)00030-6]. [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg ND, & Menard SW (2003). Violence among family members of children and adolescents evaluated for sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 1367–1376. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerker BD, Zhang J, Nadeem E, Stein REK, Hurlburt MS, Heneghan A, & Horwitz SM (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and mental health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Academic Pediatrics, 15(5), 510–517. 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, Lombardi B, Frey J, & Rose RA (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes: Comparing cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Maternal & Child Health Journal [Advanced online publication. 10.1007/s10995-017-2365-1]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T, Kotch J, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, English DJ, Proctor LJ, … Dubowitz H (2010). Witnessed violence and youth behavior problems: A multi-informant study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 1–19. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Newton R, Hunter WM, English D, & Everson MD (2003). Exposure to family violence in young at-risk children: A longitudinal look at the effects of victimization and witnessed physical and psychological aggression. Journal of Family Violence, 18(1), 59–73. 10.1023/A:1021405515323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell N, & Rubin D (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae JS, Chapman MV, & Christ SL (2006). Profile of children investigated for sexual abuse: Association with psychopathology symptoms and services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(4), 468–481. 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuigan WM, & Pratt CC (2001). The predictive impact of domestic violence on three types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 869–883. 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2010). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nooner KB, Litrownik AJ, Thompson R, Margolis B, English DJ, Knight ED, & Roesch S (2010). Youth self-report of physical and sexual abuse: A latent class analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 146–154. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AMS, & O’Leary SG (2000). Co-occurrence of partner and parent aggression: Research and treatment implications. Behavior Therapy, 31, 631–648. 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80035-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, & Fisher PA (2008). Psychological and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(10), 958–971. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak SD, Cicchetti D, Hornung K, & Reed A (2000). Recognizing emotion in faces: Developmental effects of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychology, 36(5), 679–688. 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch SC, Villodas M, & Villodas F (2010). Latent class/profile analysis in maltreatment research: A commentary on Nooner, et al., Pears et al., and looking beyond. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 155–160. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclove L (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Scott BG, Burke NJ, Weems CF, Hellman JL, & Carrión VG (2013). The interrelation of adverse childhood experiences within an at-risk prediatric sample. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 6, 217–229. 10.1080/19361521.2013.811459. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman KL, Rossman BBR, & West JC (1999). Co-occurrence of spousal violence and child abuse: Conceptual implications. Child Maltreatment, 4, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, & McEwen BS (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Jama, 301(21), 2252–2259. 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambaugh LF, Ringeisen H, Casanueva CC, Tueller S, Smith KE, & Dolan M (2013). Adverse childhood experiences in NSCAW. OPRE report #2013–26 Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh C, MacMillan HL, & Jamieson E (2003). The relationship between parental substance abuse and child maltreatment: Findings from the Ontario Health Supplement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(12), 1409–1425. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]