Abstract

Purpose of Review.

To review recent data that suggest opposing effects of brain angiotensin type-1 (AT1R) and type-2 (AT2R) receptors on blood pressure (BP). Here, we discuss recent studies that suggest pro-hypertensive and pro-inflammatory actions of AT1R, and anti-hypertensive and anti-inflammatory actions of AT2R. Further, we propose mechanisms for the interplay between brain angiotensin receptors and neuroinflammation in hypertension.

Recent Findings.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays an important role in regulating cardiovascular physiology. This includes brain AT1R and AT2R, both of which are expressed in or adjacent to brain regions that control BP. Activation of AT1R within those brain regions mediate increases in BP and cause neuroinflammation, which augments the BP increase in hypertension. The fact that AT1R and AT2R have opposing actions on BP, suggests that AT1R and AT2R may have similar opposing actions on neuroinflammation. However, the mechanisms by which brain AT1R and AT2R mediate neuroinflammatory responses remain unclear.

Summary.

The interplay between brain angiotensin receptor subtypes and neuroinflammation exacerbates or protects against hypertension.

Keywords: Brain angiotensin receptors, AT1R, AT2R, neuroinflammation, microglia, hypertension

Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays an important regulatory role in cardiovascular physiology [1]. This involves the actions of angiotensin II (Ang II) on angiotensin II type 1 (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptors within or near the brain cardiovascular control centers [2, 3]. AT1R-mediated effects of Ang II within those centers result in sympatho-excitaion and vasopressin and corticosterone secretion, leading to increases in blood pressure (BP) [4–6, 7•]. Importantly, those mechanisms contribute to neurogenic hypertension, which is characterized by chronic sympatho-excitation [8, 9]. On the other hand, brain AT2R are thought to elicit opposing effects to AT1R [10, 11•, 12], and are suggested to be protective against hypertension [3]. AT2R-mediated effects of Ang II result in sympatho-inhibition and attenuate vasopressin secretion, leading to decreases in BP [13, 14••, 15, 11•, 16]. These actions are consistent with the anatomical localization of both AT1R and AT2R in the brain [17, 18, 19••, 20••]. AT1R are found within the cardiovascular control centers of the brain, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN), nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), area postrema (AP), and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) [17, 18, 20••]. While AT2R are expressed within or adjacent to the cardiovascular centers containing AT1R, it is evident that these angiotensin receptor subtypes are largely expressed by distinct cell populations [17, 18, 19••, 20••]. This suggests distinct brain circuitry and mechanisms by which AT1R and AT2R oppose one another in their regulation of cardiovascular physiology in hypertension.

Chronic local inflammation in cardiovascular control centers of the brain contributes to neurogenic hypertension [21, 22, 23•]. This includes the activation of microglia [22, 24], upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [25–27, 23•], and recruitment of circulating immune cells [28, 27, 29]. This local pro-inflammatory state results in sustained sympatho-excitaion, mediating prolonged increases in BP [23•, 25]. Furthermore, the pro-hypertensive actions of AT1R involve the stimulation of local pro-inflammatory mechanisms [29, 23•, 30, 31], whereas the protective effects of AT2R appear to include anti-inflammatory mechanisms [32, 14••, 33]. However, we recently found that both AT1R and AT2R at or near brain cardiovascular control centers are exclusively expressed by neurons and not by glia in both naïve and hypertensive rats and mice [20••]. This might suggest that both pro-hypertensive AT1R and anti-hypertensive AT2R induce respective pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects via local paracrine activity, possibly through the neuronal secretion of chemokines and cytokines that influence inflammatory cells and glia [34, 20••].

In the present review, we discuss evidence supporting the pro-hypertensive/pro-inflammatory effects of Ang II on neurons containing AT1R, and its anti-hypertensive/anti-inflammatory effects on neurons containing AT2R, in both normal and hypertensive conditions. Further, we propose mechanisms by which AT1R and AT2R induce pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects respectively.

The Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS)

The initial steps in the discovery of RAS began with the experiments performed by Robert Tigerstedt and Per Bergman at the Karolinska Institute, who demonstrated that the injection of rabbit kidney extract into naïve rabbits increased BP [35]. Those experiments laid out the foundations for the classical arm of the RAS. Under normal physiological conditions the secretion of renin by the kidneys acts to convert angiotensinogen into angiotensin I, which is then converted to Ang II by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) [1, 36, 37]. Circulating Ang II acting via AT1R mediates vasocontraction, adrenal steroids secretion, vasopressin release, sodium reabsorption, and decreased renal blood flow, to ultimately increase blood volume and arterial BP [38, 39, 36]. For example, pressor responses to systemically infused Ang II are absent in mice lacking AT1R [40]. Thus, the classical Ang II – AT1R axis acting to increase BP is pro-hypertensive. In fact, one of the many rodent models of hypertension involves the continuous systemic infusion of Ang II, where hypertension is established one week following Ang II infusion [41]. Whereas, the systemic infusion of the AT1R antagonist – losartan reduces BP in hypertension, which is consistant across many species, including hypertensive humans [42–44].

More recently, an alternative component of RAS was identified as the protective arm of the RAS [45, 3]. This protective arm includes the action of Ang II on AT2R which are thought to counteract many of the actions of AT1R [10]. This was first demonstrated in AT2R-knockout mice which displayed an enhanced pressor responsiveness to Ang II, indicating a BP lowering effect of AT2R [46, 47]. Indeed, experiments in isolated vessels from various vascular beds demonstrate a vasodilatory effect of AT2R [48–50]. Furthermore, the in vivo selective pharmacological stimulation of AT2R by agonists, such as Compound 21 (C21) and CGP42112, mediated a BP lowering effect under the blockade of AT1R [51, 52]. More intriguingly, the infusion of the AT2R-agonist C21 reduced BP in a rodent model of Ang II-induced hypertension [53, 54]. These studies indicate that the systemic activation of AT2R can lower BP only when AT1R are blocked, or when animals are hypertensive. Nonetheless, this suggests that the alternative/protective arm of RAS plays an anti-hypertensive role through Ang II – AT2R axis.

While the evidence discussed suggests that these angiotensin receptor subtypes induce opposing effects in regulating cardiovascular physiology under normal physiological conditions, the evidence also suggest an important counter-regulatory role for these receptors in mediating hypertension. As autonomic dysfunction leading to chronic sympatho-excitation is a hallmark of hypertension [8, 9], this raises the question of whether brain AT1R and AT2R can act on brain circuitry to exert counter-regulatory effects on the sympathetic outflow to the cardiovascular organs.

The Brain Renin-Angiotensin System

Complex neural networks spanning a number of specialized brain structures are directly involved in controlling and regulating sympathetic outflow to the cardiovascular organs [55]. This includes a number of circumventricular organs in the forebrain and the brainstem that lack a functional blood brain barrier and can directly sense factors in systemic circulation [56]. The subfronical organ (SFO) in the forebrain, can sense circulating Ang II in systemic circulation, and it projects to the pre-autonomic neurons of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN). These PVN pre-autonomic neurons project to the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) and to the sympathetic preganglionic neurons of the interomediolateral column of the spinal cord (IML) [4, 57, 55]. Similarly, the area postrema (AP) in the brainstem is another circumventricular organ that projects to the pre-autonomic neurons of the RVLM [58, 59]. Finally, the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem can directly sense cardiovascular function through afferents arising from the aortic arch and the carotid sinus which input on the NTS [60]. Those autonomic brain regions that sense, control, and regulate cardiovascular physiology are known as cardiovascular control centers, where Ang II can regulate cardiovascular physiology via acting on those regions [4, 61]. For example, circulating Ang II can impact the brain via actions at AT1R-containing neurons in the SFO that innervate preautonomic (RVLM – projecting) neurons of the PVN to increase sympathetic nerve activity and BP [4, 5]. Similarly, circulating Ang II can increase BP by acting on AT1R localized to RVLM – projecting neurons of the AP [62, 63]. Furthermore, in hypertension the blood brain barrier becomes increasingly permeable in highly vascularized brain regions that usually comprise of an intact blood brain barrier (under normal physiological conditions), allowing circulating Ang II to act on AT1R in regions that include the PVN [30]. In addition, brain-derived Ang II may exert actions at AT1R in the PVN, NTS and RVLM [45]. Thus, Ang II can regulate cardiovascular physiology by acting on brain circuitry that controls and regulates the sympathetic outflow to cardiovascular organs.

Brain AT1R in Physiological and Hypertensive Conditions

The distribution and the roles of brain AT1R are well-characterized and defined in the literature. The discovery of angiotensin receptor subtypes that revealed the location of AT1R within the brain was primarily determined via receptor autoradiography [17, 64, 65]. These studies demonstrated a wide distribution of AT1R expression in the brain, including high densities in the cardiovascular control centers. These views on the distribution of AT1R in the brain were recently confirmed with the development of AT1R-eGFP transgenic reporter mouse [66], and refined with the recent development of our AT1R-tdTom transgenic reporter mouse [20••]. High densities of AT1R are found in the SFO, PVN, AP, NTS and RVLM [66, 20••]. Interestingly, AT1R are almost exclusively localized to neurons rather than to microglia or astrocytes in those cardiovascular regions of the brain [20••, 17]. Furthermore, AT1R appears to be primarily expressed on glutamatergic neurons [7•, 20••]. This suggests that AT1R can directly influence the neurons of the cardiovascular centers to elicit sympatho-excitation and increase BP. For example, the actions of Ang II on AT1R in the SFO [4, 5], PVN [6, 7•], AP [67, 68], and IML [69] result in sympathetically mediated increases in BP, and the modulation of the baroreflex and BP via acting on the NTS [70, 71]. This therefore suggests a pro-hypertensive role that the brain Ang II – AT1R plays during hypertension. In fact, the mRNA expression levels of AT1R in the RVLM and the NTS were higher in hypertensive rats in comparison to normotensive rats [72, 73]. Furthermore, the administration of the AT1R antagonist losartan into the brain reduces BP in hypertensive rats [72, 74]. Evidence discussed here supports a role for brain AT1R in maintaining cardiovascular physiology under normal physiological conditions. In hypertension, the increased expression of AT1R in the brain augments the effects of their stimulation, contributing to the severe increases in BP that are observed.

Brain AT2R in Physiological and Hypertensive Conditions

While the distribution and the role of brain AT1R is well characterized, only recently did investigators begin to uncover the roles of brain AT2R. When the discovery of angiotensin receptor subtypes was made in the late 1980’s, the location of AT2R and AT1R within the brain was primarily determined via receptor autoradiography or membrane binding studies [75, 76]. Based on these studies it was demonstrated that the expression of AT2R was high and very widespread in neonatal tissues, including in the brain [75, 76]. In contrast, the studies indicated that in adult brain AT2R expression is more limited and localized, and largely non-overlapping with that of AT1R. For example, high densities of AT1R were shown to be present in cardiovascular centers of the brain, which included the SFO, PVN, AP, NTS, and RVLM [17, 64, 65]. The highest densities of AT2R, on the other hand, were shown to be present in areas such as the inferior olive, the septum and the medial geniculate nucleus, none of which have direct involvement in blood pressure control [75, 76]. These views on the distribution of AT2R in the brain were largely confirmed, but also somewhat revised by early traditional autoradiographic in situ hybridization (ISH) studies, which revealed the presence of AT2R mRNA within the NTS of adult rats [17].

By using the recent advent of newer technologies, namely the development of an AT2R-eGFP transgenic reporter mouse and fluorescence ISH for the detection of AT2R mRNA, we were able to better define the distribution of AT2R within the brain, as the use of those technologies have enabled more sensitive and discrete cellular localization of AT2R within the brain [19••]. Our AT2R-eGFP reporter mouse provided a number of major advances. 1) It revealed a much more detailed regional pattern of AT2R-positive cells in the adult brain, results supported by fluorescence ISH. 2) It revealed that in normotensive mice AT2R are exclusively localized to neurons within the cardiovascular control centers that were assessed, and are not present on microglia or astrocytes. While the latter observation supports the findings of an earlier ISH study [17], a number of studies indicate the presence of AT2R on astrocytes and microglia in culture [31, 77, 78]. 3) It enabled phenotyping of the neurons that contain AT2R [19••]. Results from the AT2R-eGFP reporter mice that are of particular interest are those which demonstrate the localization of AT2R-positive cells within or near to brain areas that have direct influence on sympathetic outflow and BP control. For example, use of this mouse not only confirmed the presence of AT2R containing neurons in the intermediate NTS, but also demonstrated that these neurons are primarily GABAergic [19••]. The reporter mouse also revealed a heavy concentration of AT2R-positive neurons in the AP, as well as AT2R neuronal fibers in the RVLM and PVN [19••]. Interestingly, a number of the AT2R-positive neuronal fibers and terminals in the PVN are derived from AT2R containing GABAergic neurons that surround this nucleus [11•]. This suggests that AT2R are primarily expressed by the GABAergic neurons in the cardiovascular centers, which possibly allows them to elicit sympatho-inhibition and decreases in BP.

The first evidence that stimulation of brain AT2R lowers BP, came from pharmacological studies which demonstrated that the AT1R-mediated pressor responses to intracerebroventricularly applied Ang II were amplified in the presence of the AT2R antagonist PD123319 [79]. More evidence of a sympatho-inhibitory and BP lowering effects of AT2R has since emerged using the selective AT2R agonists, CGP42112 or C21. For example, the chronic brain intracerebroventricular infusion of C21 in conscious rats resulted in sympatho-inhibition, leading to a reduction in BP [15]. Similarly, the local administration of CGP42112 or C21 into the RVLM and the IML led to sympatho-inhibition and BP lowering effects [16, 80, 69]. Collectively these findings suggested an anti-hypertensive effect of brain AT2R. Indeed, the chronic intracerebroventricular infusion of C21 in spontaneously hypertensive rats and in DOCA-salt induced hypertension reduced sympathetic nerve activity and BP [13, 14]. Anti-hypertensive effects are also observed with the increased expression of AT2R in the RVLM and the NTS of hypertensive rodents, which leads to decreased BP [80–82]. The evidence discussed supports a protective role for brain AT2R in regulating cardiovascular physiology under physiological and hypertensive conditions.

Relative Distribution & Cellular localization of Brain Angiotensin Receptor Subtypes

In a more recent study, we have further refined the location and distribution of both AT1R and AT2R within the brain [20••]. Firstly, using a novel AT1R/AT2R dual reporter mouse we demonstrated that within the PVN and the NTS, AT1R and AT2R are exclusively expressed by neurons rather than microglia or astrocytes. Further, this study provides evidence that there is no re-distribution of AT1R and AT2R from neurons to astrocytes or microglia in cardiovascular control centers during sustained hypertension induced by DOCA-salt administration [20••]. Secondly, using the AT1R/AT2R dual reporter mouse, it was possible to perform a detailed analysis of the relative locations of AT1R and AT2R within brain areas of male and female mice that are either directly or indirectly involved in cardiovascular regulation. These studies revealed that there are greater numbers of AT2R-positive cells than AT1R-positive cells in both the NTS and AP, with no differences between female and male mice (Table 1) [20••]. Furthermore, it is apparent that AT1R and AT2R are localized primarily to different populations of neurons, with the highest levels of colocalization observed in the AP and NTS [20••]. For example; AT1R are mainly expressed on glutamatergic neurons in the PVN, whereas AT2R are expressed on GABAergic neurons that surround the PVN with their fibers inputting on the PVN (Table 1). Thus, based on the mostly distinct localization of AT1R and AT2R to separate neurons in brain regions that influence the cardiovascular system, it is reasonable to speculate that contrasting functional effects of these receptors are mediated through different neuronal circuits; however, the possibility that there are intracellular interactions stimulated by these receptors on the same neurons that influence cardiovascular regulation cannot be entirely excluded at this time.

Table 1. Expression of AT1R and AT2R in the brain cardiovascular centers using transgenic reporter mice.

Expression, distribution, and phenotype of AT1R/ AT2R expressing neurons in the cardiovascular centers of the brain, using our recent and novel transgenic reporter mice. % per area represents the percentage of the region of interest occupied by positive cells (AT1R or AT2R), and the % Co-loc depicts the colocalization of AT1R to AT2R within the region of interest (percentage).

| Brain Region | Expression | % per Area | %Co-loc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT1R | AT2R | AT1R | AT2R | ||

| Forebrain | |||||

| Subfornical Organ (SFO) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Fibers [19] | ~99 [20] | ~1 [20] | ~0.2 [20] |

| Median Preoptic Nucleus (MnPO) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19]a | ~60 [20] | ~40 [20] | ~2 [20] |

| Organum Vasculum of the Lamina Terminalis (OVLT) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19] | ~75 [20] | ~25 [20] | ~2 [20] |

| Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus (PVN) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20, 7]a | Fibers [19, 11]b | ~99 [20] | ~1 [20] | ~0.2 [20] |

| Hindbrain | |||||

| Area Postrema (AP) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19] | ~40 [20] | ~60 [20] | ~5 [20] |

| Nucleus of the Solitary Tract (NTS) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19]b | ~10 [20] | ~90 [20] | ~3 [20] |

| Dorsal Motor Nucleus of the Vagus (DMNV) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19]c | ? | ? | ? |

| Nucleus Ambiguus (NA) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19]c | ? | ? | ? |

| Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla (RVLM) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Fibers [19] | ? | ? | ? |

| Caudal Ventrolateral Medulla (CVLM) | Neuronal soma & Fibers [20] | Neuronal soma & Fibers [19] | ? | ? | ? |

glutamatergic neurons,

GABAergic neurons,

choline acetyltransferase – containing neurons,

not known.

The Interplay Between Brain Angiotensin Receptors and Neuroinflammation

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of neurogenic hypertension [22, 27]. This involves the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the downregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines in the cardiovascular control centers of the brain. In Ang II – induced hypertension, the mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, are increased by at least 3-fold in the PVN, whereas the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, are reduced [22]. These inflammatory processes in the cardiovascular centers of the brain mediate sympatho-excitation and increases in BP [23•, 25]. The administration of TNF-α or IL-1β into the SFO increases renal sympathetic nerve activity and BP [83•]. Similarly, in the PVN and the AP, TNF-α and IL-1β mediate increases in renal and cardiac sympathetic nerve activity; leading to elevations in BP [23•, 25]. More intriguingly, the blockade of receptors for TNF-α or IL-1β in the SFO [84], PVN [85, 86], or AP [25] reduces BP in hypertensive rats. Thus, neuroinflammation or the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the cardiovascular centers of the brain results in sympathetically – mediated increases in BP, establishing a hypertensive phenotype.

The major source of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in the brain is the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (microglia and astrocytes) [22, 87]. In hypertension, microglia in the cardiovascular centers become activated and exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype; leading to the local upregulation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [22]. By preventing the activation of microglia, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are significantly reduced in regions such as the PVN, leading to the attenuation of high BP in hypertensive rats [22]. This local pro-inflammatory state, established by microglia, is capable of directly activating the pre-autonomic neurons [25]. Those pre-autonomic neurons not only play a role in mediating sympatho-excitation, but can contribute to the local inflammatory state by secreting pro-inflammatory chemokines [27]. For example, the application of Ang II to primary hypothalamic neurons, increases the mRNA and protein levels of the chemokine CCL2 in cell culture media [27]. CCL2 is a pro-inflammatory chemokine, upregulated in hypertensive rodents [27], and is capable of making the blood brain barrier more permeable [88, 89], to recruit and facilitate the infiltration of peripherally circulating immune cells [27, 28]. Infiltrating peripheral immune cells are another source of pro-inflammatory cytokine production [90]. Thus, cytokine production and secretion by infiltrating immune cells further activate pre-autonomic neurons and microglia; exacerbating the pro-inflammatory state and augmenting the sympathetic outflow and BP in hypertension [26, 91]. This vicious positive feedforward cycle between neurons, microglia, and infiltrating immune cells, results in a sustained pro-inflammatory state in the cardiovascular centers of the brain that leads to the severely increased BP in hypertension.

The RAS is a major contributor to the sustained pro-inflammatory state in the brain. For example, a single systemic administration of Ang II is capable of inducing a prolonged activation of PVN microglia, peripheral immune cell activation and mobilization, and activating the neurons of the cardiovascular centers of the brain, leading to an increased BP [29]. More intriguingly, the blockade of AT1R in the SFO [83•] or in the PVN [23•] prior to the administration of TNF-α or IL-1β, completely abolishes the sympathetic nerve activity and BP responses induced by both pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Brain Angiotensin Receptors and Neuroinflammation

AT1R as Pro-inflammatory

The pro-inflammatory effects of AT1R are well-documented in the literature. For example, AT1R are involved in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines both in vitro and in vivo [92]. In hypertensive conditions, the blockade of AT1R significantly reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in peripheral tissues, such as the aorta, and in the brain cardiovascular centers, such as the PVN [93, 94]. This blockade of AT1R that results in a reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines leads to the attenuation of the increased renal sympathetic nerve activity and BP [95]. In addition, the selective deletion of AT1R in the PVN reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and lowers BP [96•, 97•]. The expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines is regulated by the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB [98]. Interestingly, the blockade of AT1R in hypertensive rats reduces the expression of NF-κB [98, 99]. This therefore suggests that AT1R can regulate the expression of NF-κB, and thus can regulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, this link between AT1R, NF-κB, and pro-inflammatory cytokines is demonstrated within the PVN [95], supporting the notion that AT1R-containing neurons within the cardiovascular control centers can directly signal to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In fact, Ang II acting on AT1R in the PVN results in the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to sympatho-excitaion and BP elevation [100, 29]. These studies demonstrate a pro-inflammatory role that AT1R play, which can exacerbate the local inflammatory state in the cardiovascular centers of the brain and augment BP in hypertension.

AT2R as Anti-inflammatory

While AT2R are thought to be protective and play a counter-regulatory role to AT1R, only a handful of studies demonstrate an anti-inflammatory role of AT2R. Those studies utilize pharmacological AT2R agonists and antagonists to reveal the anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R (Table 2). In rodent models of neuroinflammation and autoimmune disease, the activation of AT2R by the intraperitoneal administration of CGP42112 or C21 reduced microglia activation, the number of infiltrating immune cells, and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, while increasing the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, within the central nervous system [101, 102]. In cardiovascular disease, the administration of C21 following middle cerebral artery occlusion (stroke), reduced microglia activation and peripheral immune cell infiltration [33, 32]. The protective anti-inflammatory effect of AT2R stimulation improved cognitive function and survival following stroke [33, 32]. Furthermore, DOCA-salt induced hypertension in female rats was augmented by intracerebroventricular administration of AT2R antagonist – PD123319 [14••]. The blockade of AT2R in those hypertensive rats further exacerbated the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the PVN, and further reduced the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines [14••]. These studies suggest that; (i) AT2R induce anti-inflammatory effects, (ii) those anti-inflammatory effects protect against cardiovascular disease, and (iii) anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R may be linked to the upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, as AT2R oppose the actions of AT1R, and AT1R is demonstrated to have pro-inflammatory effects through regulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, it is possible that AT2R exert anti-inflammatory effects via regulating the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10.

Table 2. The anti-inflammatory effect of AT2R.

Different studies utilizing pharmacological AT2R agonists (C21, CGP42112) or antagonists (PD123319) to demonstrate the anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R.

| Animal | Model | Drug | Effect | Region | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL-6 mice | Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis | C21 (AT2R agonist; 0.3 mg/kg; i.p.) | ↓ Microglia activation ↓ T-Cell Infiltration |

Spinal Cord | [101] |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Brain Cell Culture | C21 (AT2R agonist; 1 μM) | ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 |

N/A | [101] |

| C57BL-6 mice | LPS - Induced Inflammation | CGP42112 (AT2R agonist; 1 mg/kg; i.p.) | ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, CCL2 ↑ IL-10 |

Cerebral Cortex | [102] |

| Wistar rats | Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion | C21 (AT2R agonist; 0.12 mg/kg; oral) | ↓ Microglia activation ↓ Macrophage Infiltration |

Cerebral Cortex | [33] |

| Spontaneously Hypertensive rats | Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion | C21 (AT2R agonist; 0.14 mg/kg; icv) | ↓ Microglia activation ↓ Macrophage Infiltration |

Cerebral Cortex | [32] |

| Wistar rats | DOCA - Salt Induced Hypertension | PD123319 (AT2R antagonist; 3 μg; icv) | ↑ TNF-α, IL-1β ↓ IL-10 |

PVN | [14] |

DOCA; Deoxycorticosterone acetate, icv; intracerebroventricular, i.p; intraperitoneal, LPS; lipopolysaccharide, N/A; not applicable, PVN; paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

Mechanisms for the Interplay Between Brain Angiotensin Receptors and Neuroinflammation

While several studies seem to indicate that brain angiotensin receptors are expressed on glia [31, 77, 78], the use of the recent advanced technologies in our studies have enabled more sensitive and discrete cellular localization of AT1R/AT2R within the brain. These studies revealed that AT1R and AT2R are exclusively expressed by neurons rather than microglia or astrocytes in the cardiovascular centers of the brain [19••, 20••]. In those studies, demonstrating AT1R expression on microglia and astrocytes, Percoll density gradients were used to isolate microglia and astrocytes from the macro-dissected hypothalamus, followed by RT-PCR to demonstrate the presence of AT1R in the isolated cells [31, 78]. However, it is extremely difficult to isolate only glia or dissect the hypothalamus with such procedures, and the isolates used in the above studies may have contained neurons and glia from brain tissue surrounding the hypothalamus. Nonetheless, the possibility that brain angiotensin receptors are expressed by microglia to regulate the inflammatory processes, cannot be excluded at this point, although further studies are warranted to validate and confirm the expression of brain angiotensin receptors by glia in vivo.

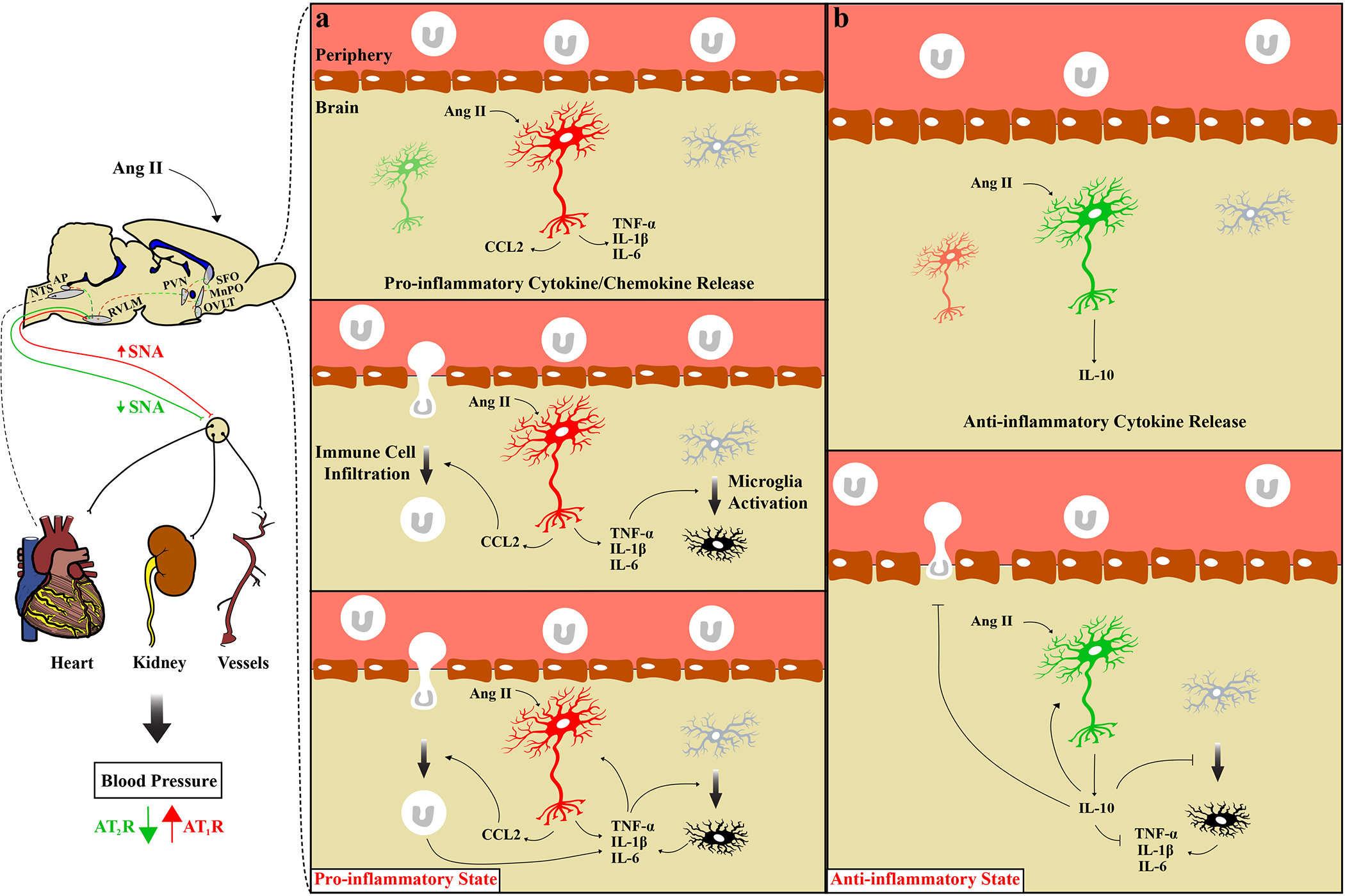

Our recent studies demonstrate that AT1R are exclusively expressed by neurons within or adjacent to the cardiovascular control centers [19••, 20••]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that AT1R regulate inflammatory processes through local paracrine activity. We propose that the actions of Ang II on AT1R mediate; (i) sympatho-excitation and increases in BP [4–6, 7•], (ii) upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines via NF-κB signaling [98, 99, 95], and (iii) secretion of pro-inflammatory chemokines such as CCL2 [27]. The upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, is capable of activating neurons to further increase sympathetic nerve activity, BP, and pro-inflammatory cytokine production [23, 83•, 25]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can activate microglia to exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype; leading to the further release of cytokines [22]. Furthermore, the upregulation of chemokines, such as CCL2, facilitates the activation and the recruitment of peripherally circulating immune cells to infiltrate cardiovascular centers of the brain [28, 26, 27]. Infiltrating peripheral immune cells are a major source of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and will result in the further upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [90]. This vicious positive feedback cycle – whereby Ang II acting on neuronal AT1R mediates pro-inflammatory cytokine production; leading to the activation of microglia and immune cell recruitment to further upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, results in the establishment of a local chronic pro-inflammatory state (Fig. 1a). The sympatho-excitatory and pro-inflammatory effects of AT1R augment sympathetic outflow and elevate BP as observed in hypertension. Therefore, we propose deleterious pro-hypertensive/pro-inflammatory effects of AT1R in the brain cardiovascular control centers.

Figure 1. The inflammatory role of brain angiotensin receptors.

A schematic diagram depicting the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects of AT1R of AT2R respectively. (a) Angiotensin II acting on AT1R expressing neuron (red) mediates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and chemokines (CCL2). Pro-inflammatory cytokines activate microglia, and chemokines facilitate immune cell infiltration (macrophages and T-lymphocytes). Activated microglia and infiltrated immune cells further upregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Pro-inflammatory cytokines can further activate neurons, microglia, and recruit immune cells. This establishes a pro-inflammatory state, which together with the sympatho-excitatory actions of AT1R, increase sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) and blood pressure. (b) Angiotensin II acting on AT2R expressing neuron (green) mediates the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10), which inhibits microglia activation, the recruitment of immune cells and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The anti-inflammatory and the sympatho-inhibitory actions of AT2R decrease SNA and blood pressure. Pointy head arrow; activation, flat head arrows; inhibition, AP; Area Postrema, MnPO; Median Preoptic Nucleus, NTS; Nucleus of the Solitary Tract, OVLT; Organum Vasculum of the Lamina Terminalis, PVN; Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus, SFO; Subfornical Organ.

Newly emerging views suggest that brain AT2R counter-regulate the actions of AT1R on BP [10–12]. This notion is supported by our recent studies demonstrating that the neuronal populations expressing AT2R are distinct from the populations that express AT1R [19••, 20••]. Thus, it is reasonable to speculate that AT1R and AT2R regulate inflammatory processes through distinct neuronal circuits. We propose that the stimulation of AT2R mediates; (i) sympatho-inhibition and BP lowering effects [16, 80, 13, 14••], and (ii) protective anti-inflammatory effects by increasing anti-inflammatory cytokine production [33, 32, 14••]. This proposition is supported by the fact that in the vast majority of studies that demonstrated BP lowering effects of AT2R, chronic infusions of AT2R agonists were required to observe such responses and the onset of the response was always delayed [15, 16, 80, 13, 14]. The delayed onset of the BP lowering effects of AT2R may be related to duration required for the induction of the anti-inflammatory cascade. The activation of AT2R is linked to the upregulation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, which induces anti-inflammatory effects [14••, 102]. Those anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 include inhibiting the activation of microglia, the recruitment of immune cells, and inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α [103, 104]. Anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 were observed in the PVN following the intracerebroventricular gene transfer of IL-10 in rats with acute myocardial infarction [105]. Furthermore, the intracerebroventricular [106] and PVN [22] administration of IL-10 reduced BP in hypertensive rats. More intriguingly, IL-10 inhibited the effects elicited by Ang II acting on AT1R in hypothalamic neurons [107]. This indeed suggests that the anti-inflammatory actions of IL-10 (the secretion of which may well be spurred by AT2R) counteract the actions of AT1R. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the stimulation of AT2R results in the upregulation of IL-10, which in turn inhibits the activation of microglia, immune cell recruitment and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, establishing a local anti-inflammatory state that decreases BP (Fig. 1b). The sympatho-inhibitory and the anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R reduce BP. Thus, we propose protective anti-hypertensive/anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R.

More recent studies indicate that Ang II may directly act on microglia through different receptors, other than angiotensin receptors, to regulate inflammatory processes [31, 108, 109]. This involves a receptor that plays a major role in the innate immune response, and is termed toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) [110]. In vitro studies demonstrate a link between Ang II and TLR4 in regulating pro-inflammatory cytokine production [109]. Furthermore, the central blockade of TLR4 seems to improve cardiac tissue inflammation in Ang II – induced hypertension [108]. Interestingly, TLR4 is expressed by microglia in the PVN, and the pro-inflammatory responses mediated by Ang II in the PVN are completely abolished in mice lacking TLR4 [31]. However, without further studies to validate the crosstalk between Ang II and TLR4, it is difficult to infer that Ang II can regulate the inflammatory processes by interacting with glial TLR4. It is possible that the pro-inflammatory cytokines released by neurons in response to Ang II – AT1R act on TLR4 to activate microglia to induce a pro-inflammatory state. Thus, binding studies are warranted and are essential to validate and confirm this crosstalk between Ang II and TLR4.

In summary, we propose distinct neuronal circuitry that regulates the inflammatory processes in the cardiovascular centers of the brain. AT1R exert pro-inflammatory actions through local paracrine activity that results in the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and subsequent increased blood pressure. In contrast, AT2R mediate anti-inflammatory effects through the upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, and these effects contribute to the AT2R mediated fall in blood pressure (Fig. 1).

Closing Remarks

Emerging views suggest that brain AT1R and AT2R mediate counter-regulatory effects on blood pressure by acting on distinct neuronal circuits and via mechanisms that include respective pro- and anti-inflammatory actions.

Previous studies demonstrated:

Sympatho-excitatory and pressor effects of AT1R.

Pro-hypertensive effects of AT1R.

Pro-inflammatory effects of AT1R.

Sympatho-inhibitory and depressor effects of AT2R.

Anti-hypertensive effects of AT2R.

Anti-inflammatory effects of AT2R.

Our studies demonstrated:

AT1R and AT2R are expressed within or adjacent to the brain cardiovascular centers.

AT1R and AT2R are exclusively expressed on neurons rather than glia.

AT1R and AT2R are predominantly expressed by distinct neuronal populations.

Therefore, studies discussed in this review suggest that AT1R and AT2R mediate their actions through distinct neuronal circuitry; (i) a deleterious sympatho-excitatory/pro-hypertensive/pro-inflammatory AT1R circuit, and (ii) a protective sympatho-inhibitory/anti-hypertensive/anti-inflammatory AT2R circuit.

Conclusion

The renin – angiotensin system plays an important regulatory role in cardiovascular physiology [1]. This involves actions of angiotensin II on its receptors within the brain [2, 3]. In the cardiovascular control centers of the brain, AT1R and AT2R are expressed on distinct neuronal populations [19••, 20••]. AT1R mediate sympatho-excitation and blood pressure elevations [4–6, 7•], and the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines [98, 99, 95, 27], which further augment sympathetic outflow and blood pressure elevation [23•, 83•, 25]. In contrast, AT2R mediate sympatho-inhibitory and blood pressure lowering effects [16, 11•, 80, 13, 14••], and the upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines [14••, 102]. Therefore, AT1R mediate deleterious sympatho-excitatory/pro-hypertensive/pro-inflammatory effects that exacerbate hypertension, whereas AT2R mediate protective sympatho-inhibitory/anti-hypertensive/anti-inflammatory effects that protect against hypertension.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest or published recently are highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Dzau VJ. Circulating versus local renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular homeostasis. Circulation. 1988;77(6 Pt 2):I4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson AV. Angiotensinergic regulation of autonomic and neuroendocrine outputs: critical roles for the subfornical organ and paraventricular nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89(4):370–6. doi: 10.1159/000211202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Kloet AD, Steckelings UM, Sumners C. Protective angiotensin type 2 receptors in the brain and hypertension. Current hypertension reports. 2017;19(6):46. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0746-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga VA, Medeiros IA, Ribeiro TP, Franca-Silva MS, Botelho-Ono MS, Guimaraes DD. Angiotensin-II-induced reactive oxygen species along the SFO-PVN-RVLM pathway: implications in neurogenic hypertension. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2011;44(9):871–6. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes FC, Braga VA. Chronic angiotensin II infusion modulates angiotensin II type I receptor expression in the subfornical organ and the rostral ventrolateral medulla in hypertensive rats. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2011;12(4):440–5. doi: 10.1177/1470320310394891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu G-Q, Patel KP, Zucker IH, Wang W. Microinjection of ANG II into paraventricular nucleus enhances cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2002;282(6):H2039–H45. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00854.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.•.de Kloet AD, Wang L, Pitra S, Hiller H, Smith JA, Tan Y et al. A unique “angiotensin-sensitive” neuronal population coordinates neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and behavioral responses to stress. J Neurosci. 2017;37(13):3478–90. doi:doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3674-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated cardiovascular-related actions mediated by AT1R located on a specific set of neurons

- 8.Oliveira-Sales EB, Toward MA, Campos RR, Paton JF. Revealing the role of the autonomic nervous system in the development and maintenance of Goldblatt hypertension in rats. Autonomic Neuroscience. 2014;183(100):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira‐Sales EB, Colombari E, Abdala AP, Campos RR, Paton JF. Sympathetic overactivity occurs before hypertension in the two‐kidney, one‐clip model. Exp Physiol. 2016;101(1):67–80. doi: 10.1113/EP085390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unger T, Steckelings UM, dos Santos RAS. The protective arm of the renin angiotensin system (RAS): functional aspects and therapeutic implications. Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.•.De Kloet AD, Pitra S, Wang L, Hiller H, Pioquinto DJ, Smith JA et al. Angiotensin type-2 receptors influence the activity of vasopressin neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in male mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(8):3167–80. doi:doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper has provided the first documentation of a cardiovascular-related actions (secretion of AVP) mediated by AT2R located on a specific set of neurons

- 12.McCarthy CA, Widdop RE, Denton KM, Jones ES. Update on the angiotensin AT 2 receptor. Current hypertension reports. 2013;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0321-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brouwers S, Smolders I, Wainford RD, Dupont AG. Hypotensive and sympathoinhibitory responses to selective central AT2 receptor stimulation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical Science. 2015;129(1):81–92. doi:doi: 10.1042/CS20140776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.••.Dai S-Y, Peng W, Zhang Y-P, Li J-D, Shen Y, Sun X-F. Brain endogenous angiotensin II receptor type 2 (AT2-R) protects against DOCA/salt-induced hypertension in female rats. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2015;12(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0261-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper is the first to demonstrate anti-inflammatory actions mediated by AT2R in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats

- 15.Gao J, Zhang H, Le KD, Chao J, Gao L. Activation of central angiotensin type 2 receptors suppresses norepinephrine excretion and blood pressure in conscious rats. American journal of hypertension. 2011;24(6):724–30. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao L, Wang W, Wang W, Li H, Sumners C, Zucker IH. Effects of angiotensin type 2 receptor overexpression in the rostral ventrolateral medulla on blood pressure and urine excretion in normal rats. Hypertension. 2008;51(2):521–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenkei Z, Palkovits M, Corvol P, Llorens-Cortes C. Expression of angiotensin type-1 (AT1) and type-2 (AT2) receptor mRNAs in the adult rat brain: a functional neuroanatomical review. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 1997;18(4):383–439. doi: 10.1006/frne.1997.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millan MA, Jacobowitz DM, Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Differential distribution of AT1 and AT2 angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the rat brain during development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1991;88(24):11440–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.••.de Kloet AD, Wang L, Ludin JA, Smith JA, Pioquinto DJ, Hiller H et al. Reporter mouse strain provides a novel look at angiotensin type-2 receptor distribution in the central nervous system. Brain Structure and Function. 2016;221(2):891–912. doi:doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reports the development of a transgenic AT2R reporter mouse, which has enabled the discrete cellular localization of AT2R within and near brain cardiovascular control centers

- 20.••.Sumners C, Alleyne A, Rodríguez V, Pioquinto DJ, Ludin JA, Kar S et al. Brain angiotensin type-1 and type-2 receptors: cellular locations under normal and hypertensive conditions. Hypertension Research. 2020;43(4):281–95. doi: 10.1038/s41440-019-0374-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper reports the development of a dual transgenic AT1R/AT2R reporter mouse, which has enabled the discrete cellular localization of AT1R and AT2R within and near brain cardiovascular control centers

- 21.Shen XZ, Li Y, Li L, Shah KH, Bernstein KE, Lyden P et al. Microglia Participate in Neurogenic Regulation of Hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66(2):309–16. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi P, Diez-Freire C, Jun JY, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Li Q et al. Brain microglial cytokines in neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;56(2):297–303. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.•.Shi Z, Gan XB, Fan ZD, Zhang F, Zhou YB, Gao XY et al. Inflammatory cytokines in paraventricular nucleus modulate sympathetic activity and cardiac sympathetic afferent reflex in rats. Acta physiologica. 2011;203(2):289–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated pro-inflammatory actions mediated by AT1R in the cardiovascular control centers of the brain

- 24.Sharma RK, Yang T, Oliveira AC, Lobaton GO, Aquino V, Kim S et al. Microglial Cells Impact Gut Microbiota and Gut Pathology in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension. Circulation research. 2019;124(5):727–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korim WS, Elsaafien K, Basser JR, Setiadi A, May CN, Yao ST. In renovascular hypertension, TNF-α type-1 receptors in the area postrema mediate increases in cardiac and renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure. Cardiovascular Research. 2018;115(6):1092–101. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elsaafien K, Korim WS, Setiadi A, May CN, Yao ST. Chemoattraction and Recruitment of Activated Immune cells, Central Autonomic Control and Blood Pressure Regulation. Frontiers in Physiology. 2019;10:984. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santisteban MM, Ahmari N, Carvajal JM, Zingler MB, Qi Y, Kim S et al. Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circulation research. 2015;117(2):178–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmari N, Santisteban MM, Miller DR, Geis NM, Larkin RM, Redler TL et al. Elevated bone marrow sympathetic drive precedes systemic inflammation in angiotensin II hypertension. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2019;317(2):H279–H89. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00510.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zubcevic J, Santisteban MM, Perez PD, Arocha R, Hiller H, Malphurs WL et al. A Single Angiotensin II Hypertensive Stimulus Is Associated with Prolonged Neuronal and Immune System Activation in Wistar-Kyoto Rats. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017;8:592. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biancardi VC, Son SJ, Ahmadi S, Filosa JA, Stern JE. Circulating angiotensin II gains access to the hypothalamus and brain stem during hypertension via breakdown of the blood–brain barrier. Hypertension. 2013;63(3):572–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biancardi VC, Stranahan AM, Krause EG, de Kloet AD, Stern JE. Cross talk between AT1 receptors and Toll-like receptor 4 in microglia contributes to angiotensin II-derived ROS production in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2016;310(3):H404–H15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00247.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy CA, Vinh A, Miller AA, Hallberg A, Alterman M, Callaway JK et al. Direct angiotensin AT2 receptor stimulation using a novel AT2 receptor agonist, compound 21, evokes neuroprotection in conscious hypertensive rats. Plos One. 2014;9(4):e95762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson L, Dong G, Althomali W, Sayed MA, Eldahshan W, Baban B et al. Delayed Administration of Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor (AT2R) Agonist Compound 21 Prevents the Development of Post-stroke Cognitive Impairment in Diabetes Through the Modulation of Microglia Polarization. Translational Stroke Research. 2019:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s12975-019-00752-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Kloet AD, Pioquinto DJ, Nguyen D, Wang L, Smith JA, Hiller H et al. Obesity induces neuroinflammation mediated by altered expression of the renin–angiotensin system in mouse forebrain nuclei. Physiology & behavior. 2014;136:31–8. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tigerstedt R, Bergman P. Niere und Kreislauf 1. Skandinavisches Archiv für Physiologie. 1898;8(1):223–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1898.tb00272.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unger T The role of the renin-angiotensin system in the development of cardiovascular disease. The American journal of cardiology. 2002;89(2):3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sparks MA, Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Mirotsou M, Coffman TM. Classical renin‐angiotensin system in kidney physiology. Comprehensive Physiology. 2011;4(3):1201–28. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung O, Stoll M, Unger T. Physiologic and pharmacologic implications of AT1 versus AT2 receptors. Blood pressure Supplement. 1996;2:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Gasparo M, Catt K, Inagami T, Wright J, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2000;52(3):415–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O et al. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1A angiotensin II receptor gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92(8):3521–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson RJ, Alpers CE, Yoshimura A, Lombardi D, Pritzl P, Floege J et al. Renal injury from angiotensin II-mediated hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;19(5):464–74. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koprdová R, Cebová M, Kristek F. Long-term effect of losartan administration on blood pressure, heart and structure of coronary artery of young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Physiological research. 2009;58(3):327–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park JB, Intengan HD, Schiffrin EL. Reduction of resistance artery stiffness by treatment with the AT1-receptor antagonist losartan in essential hypertension. Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 2000;1(1):40–5. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2000.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodrigo E, Maeso R, Muñoz-García R, Navarro-Cid J, Ruilope LM, Cachofeiro V et al. Endothelial dysfunction in spontaneously hypertensive rats: consequences of chronic treatment with losartan or captopril. Journal of hypertension. 1997;15(6):613–8. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Assersen K, Sumners C, Steckelings UM. The renin-angiotensin system in hypertension, a constantly renewing classic: Focus on the angiotensin AT2-receptor. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2020;36(5):683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ichiki T, Labosky PA, Shiota C, Okuyama S, Imagawa Y, Fogo A et al. Effects on blood pressure and exploratory behaviour of mice lacking angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Nature. 1995;377(6551):748–50. doi: 10.1038/377748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross V, Milia AF, Plehm R, Inagami T, Luft FC. Long-term blood pressure telemetry in AT2 receptor-disrupted mice. Journal of hypertension. 2000;18(7):955–61. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018070-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arima S, Endo Y, Yaoita H, Omata K, Ogawa S, Tsunoda K et al. Possible role of P-450 metabolite of arachidonic acid in vasodilator mechanism of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the isolated microperfused rabbit afferent arteriole. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100(11):2816–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI119829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Endo Y, Arima S, Yaoita H, Omata K, Tsunoda K, Takeuchi K et al. Function of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the postglomerular efferent arteriole. Kidney International Supplement. 1997(63):S205–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Endo Y, Arima S, Yaoita H, Tsunoda K, Omata K, Ito S. Vasodilation mediated by angiotensin II type 2 receptor is impaired in afferent arterioles of young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Journal of vascular research. 1998;35(6):421–7. doi:doi: 10.1159/000025613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carey RM, Howell NL, Jin X-H, Siragy HM. Angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated hypotension in angiotensin type-1 receptor-blocked rats. Hypertension. 2001;38(6):1272–7. doi:doi: 10.1161/hy1201.096576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li XC, Widdop RE. AT2 receptor‐mediated vasodilatation is unmasked by AT1 receptor blockade in conscious SHR. British journal of pharmacology. 2004;142(5):821–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kemp BA, Howell NL, Gildea JJ, Keller SR, Padia SH, Carey RM. Response to letter regarding article,“AT2 receptor activation induces natriuresis and lowers blood pressure”. Circulation research. 2014;115(9):e26–e7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kemp BA, Howell NL, Keller SR, Gildea JJ, Padia SH, Carey RM. AT2 receptor activation prevents sodium retention and reduces blood pressure in angiotensin II–dependent hypertension. Circulation research. 2016;119(4):532–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schramm LP, Strack AM, Platt KB, Loewy AD. Peripheral and central pathways regulating the kidney: a study using pseudorabies virus. Brain Res. 1993;616(1–2):251–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90216-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weindl A Neuroendocrine aspects of circumventricular organs. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. 1973;3:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shafton AD, Ryan A, Badoer E. Neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus send collaterals to the spinal cord and to the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;801(1–2):239–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blessing W, Hedger S, Joh T, Willoughby J. Neurons in the area postrema are the only catecholamine-synthesizing cells in the medulla or pons with projections to the rostral ventrolateral medulla (C 1-area) in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1987;419(1):336–40. doi:doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90604-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dampney RA, Czachurski J, Dembowsky K, Goodchild AK, Seller H. Afferent connections and spinal projections of the pressor region in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the cat. Journal of the autonomic nervous system. 1987;20(1):73–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(87)90083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pilowsky PM, Goodchild AK. Baroreceptor reflex pathways and neurotransmitters: 10 years on. Journal of hypertension. 2002;20(9):1675–88. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sá JM, Barbosa RM, Menani JV, De Luca LA Jr, Colombari E, Colombari DSA. Cardiovascular and hidroelectrolytic changes in rats fed with high-fat diet. Behavioural brain research. 2019;373:112075. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papas S, Smith P, Ferguson AV. Electrophysiological evidence that systemic angiotensin influences rat area postrema neurons. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1990;258(1):R70–R6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.1.R70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lowes VL, McLean LE, Kasting NW, Ferguson AV. Cardiovascular consequences of microinjection of vasopressin and angiotensin II in the area postrema. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1993;265(3):R625–R31. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.3.R625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carter DA, Choong Y-T, Connelly AA, Bassi JK, Hunter NO, Thongsepee N et al. Functional and neurochemical characterization of angiotensin type 1A receptor-expressing neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract of the mouse. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2017;313(4):R438–R49. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00168.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen D, Jancovski N, Bassi JK, Nguyen-Huu T-P, Choong Y-T, Palma-Rigo K et al. Angiotensin type 1A receptors in C1 neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla modulate the pressor response to aversive stress. J Neurosci. 2012;32(6):2051–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5360-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzalez AD, Wang G, Waters EM, Gonzales KL, Speth RC, Van Kempen TA et al. Distribution of angiotensin type 1a receptor-containing cells in the brains of bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Neuroscience. 2012;226:489–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hasser EM, Cunningham JT, Sullivan MJ, Curtis KS, Blaine EH, Hay M. Area postrema and sympathetic nervous system effects of vasopressin and angiotensin II. Clin Exp Pharmacol P. 2000;27(5‐6):432–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nahey DB, Collister JP. ANG II-induced hypertension and the role of the area postrema during normal and increased dietary salt. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;292(1):H694–H700. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00998.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chao J, Gao J, Parbhu K-JK, Gao L. Angiotensin type 2 receptors in the intermediolateral cell column of the spinal cord: negative regulation of sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure. International journal of cardiology. 2013;168(4):4046–55. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abegaz B, Davern PJ, Jackson KL, Nguyen-Huu T-P, Bassi JK, Connelly A et al. Cardiovascular role of angiotensin type1A receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract of mice. Cardiovascular research. 2013;100(2):181–91. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Colombari E, Colombari DS. NTS AT1a receptor on long-term arterial pressure regulation: putative mechanism. Cardiovascular Research; 2013;100(2):173–174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.de Oliveira-Sales EB, Nishi EE, Boim MA, Dolnikoff MS, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR. Upregulation of AT1R and iNOS in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) is essential for the sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension in the 2K-1C Wistar rat model. American journal of hypertension. 2010;23(7):708–15. doi:doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Song K, Kurobe Y, Kanehara H, Okunishi H, Wada T, Inada Y et al. Quantitative localization of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Blood pressure Supplement. 1994;5:21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Park CG, Leenen F. Effects of centrally administered losartan on deoxycorticosterone-salt hypertension rats. Journal of Korean medical science. 2001;16(5):553–7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.5.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsutsumi K, Saavedra JM. Characterization and development of angiotensin II receptor subtypes (AT1 and AT2) in rat brain. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1991;261(1):R209–R16. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grady EF, Sechi LA, Griffin CA, Schambelan M, Kalinyak JE. Expression of AT2 receptors in the developing rat fetus. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1991;88(3):921–33. doi:doi: 10.1172/JCI115395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu C-Y, Zha H, Xia Q-Q, Yuan Y, Liang X-Y, Li J-H et al. Expression of angiotensin II and its receptors in activated microglia in experimentally induced cerebral ischemia in the adult rats. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 2013;382(1–2):47–58. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1717-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stern JE, Son S, Biancardi VC, Zheng H, Sharma N, Patel KP. Astrocytes contribute to angiotensin II stimulation of hypothalamic neuronal activity and sympathetic outflow. Hypertension. 2016;68(6):1483–93. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li Z, Iwai M, Wu L, Shiuchi T, Jinno T, Cui T-X et al. Role of AT2 receptor in the brain in regulation of blood pressure and water intake. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;284(1):H116–H21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gao L, Wang W-Z, Wang W, Zucker IH. Imbalance of angiotensin type 1 receptor and angiotensin II type 2 receptor in the rostral ventrolateral medulla: potential mechanism for sympathetic overactivity in heart failure. Hypertension. 2008;52(4):708–14. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blanch GT, Freiria-Oliveira AH, Speretta GFF, Carrera EJ, Li H, Speth RC et al. Increased expression of angiotensin II type 2 receptors in the solitary–vagal complex blunts renovascular hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64(4):777–83. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruchaya PJ, Speretta GF, Blanch GT, Li H, Sumners C, Menani JV et al. Overexpression of AT2R in the solitary-vagal complex improves baroreflex in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Neuropeptides. 2016;60:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.•.Wei S-G, Yu Y, Zhang Z-H, Felder RB. Proinflammatory cytokines upregulate sympathoexcitatory mechanisms in the subfornical organ of the rat. Hypertension. 2015;65(5):1126–33. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated pro-inflammatory actions mediated by AT1R in the cardiovascular control centers of the brain

- 84.Yu Y, Wei S-G, Weiss RM, Felder RB. TNF-α receptor 1 knockdown in subfornical organ ameliorates sympathetic excitation and cardiac hemodynamics in heart failure rats. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2017;313(4):H744–H56. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00280.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sriramula S, Cardinale JP, Francis J. Inhibition of TNF in the brain reverses alterations in RAS components and attenuates angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Plos One. 2013;8(5):e63847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu P, Jiang S-j, Pan H, Xu A-l, Wang G-h, Ma C-l et al. Short hairpin RNA interference targeting interleukin 1 receptor type I in the paraventricular nucleus attenuates hypertension in rats. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology. 2017;470(2):439–48. doi: 10.1007/s00424-017-2081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Colombo E, Farina C. Astrocytes: key regulators of neuroinflammation. Trends in immunology. 2016;37(9):608–20. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Kunkel SL, Andjelkovic AV. Potential role of MCP-1 in endothelial cell tight junctionopening’: signaling via Rho and Rho kinase. Journal of cell science. 2003;116(22):4615–28. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Wang MM, Jankovic I, Andjelkovic AV. Caveolae‑mediated internalization of occludin and claudin‑5 during CCL2‑induced tight junction remodeling in brain endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(28):19053–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ishibashi M, Hiasa K-i, Zhao Q, Inoue S, Ohtani K, Kitamoto S et al. Critical role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 on monocytes in hypertension-induced vascular inflammation and remodeling. Circulation research. 2004;94(9):1203–10. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126924.23467.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Setiadi A, Korim WS, Elsaafien K, Yao ST. The role of the blood–brain barrier in hypertension. Exp Physiol. 2018;103(3):337–42. doi: 10.1113/EP086434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weidanz J, Jacobson LM, Muehrer RJ, Djamali A, Hullett DA, Sprague J et al. AT1R blockade reduces IFN-γ production in lymphocytes in vivo and in vitro. Kidney international. 2005;67(6):2134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xie Q-y, Sun M, Yang T-l, Sun Z-L. Losartan reduces monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in aortic tissues of 2K1C hypertensive rats. International journal of cardiology. 2006;110(1):60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ye S, Zhong H, Duong VN, Campese VM. Losartan reduces central and peripheral sympathetic nerve activity in a rat model of neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39(6):1101–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000018590.26853.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yu X-J, Suo Y-P, Qi J, Yang Q, Li H-H, Zhang D-M et al. Interaction between AT1 receptor and NF-κB in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to oxidative stress and sympathoexcitation by modulating neurotransmitters in heart failure. Cardiovascular toxicology. 2013;13(4):381–90. doi: 10.1007/s12012-013-9219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.•.de Kloet AD, Pati D, Wang L, Hiller H, Sumners C, Frazier CJ et al. Angiotensin type 1a receptors in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus protect against diet-induced obesity. J Neurosci. 2013;33(11):4825–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3806-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated pro-inflammatory actions mediated by AT1R in the cardiovascular control centers of the brain

- 97.•.Wang L, Hiller H, Smith JA, de Kloet AD, Krause EG. Angiotensin type 1a receptors in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus control cardiovascular reactivity and anxiety-like behavior in male mice. Physiological genomics. 2016;48(9):667–76. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00029.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper demonstrated pro-inflammatory actions mediated by AT1R in the cardiovascular control centers of the brain

- 98.Miguel-Carrasco JL, Zambrano S, Blanca AJ, Mate A, Vázquez CM. Captopril reduces cardiac inflammatory markers in spontaneously hypertensive rats by inactivation of NF-kB. Journal of inflammation. 2010;7(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chen S, Ge Y, Si J, Rifai A, Dworkin LD, Gong R. Candesartan suppresses chronic renal inflammation by a novel antioxidant action independent of AT1R blockade. Kidney international. 2008;74(9):1128–38. doi:doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jun JY, Zubcevic J, Qi Y, Afzal A, Carvajal JM, Thinschmidt JS et al. Brain-Mediated Dysregulation of the Bone Marrow Activity in Angiotensin II–Induced Hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60(5):1316–23. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Valero-Esquitino V, Lucht K, Namsolleck P, Monnet-Tschudi F, Stubbe T, Lucht F et al. Direct angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R) stimulation attenuates T-cell and microglia activation and prevents demyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Clinical science. 2015;128(2):95–109. doi: 10.1042/CS20130601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bhat SA, Sood A, Shukla R, Hanif K. AT2R Activation Prevents Microglia Pro-inflammatory Activation in a NOX-Dependent Manner: Inhibition of PKC Activation and p47 phox Phosphorylation by PP2A. Molecular neurobiology. 2019;56(4):3005–23. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nomoto T, Okada T, Shimazaki K, Yoshioka T, Nonaka-Sarukawa M, Ito T et al. Systemic delivery of IL-10 by an AAV vector prevents vascular remodeling and end-organ damage in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. Gene therapy. 2009;16(3):383–91. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sawada M, Suzumura A, Hosoya H, Marunouchi T, Nagatsu T. Interleukin‐10 inhibits both production of cytokines and expression of cytokine receptors in microglia. J Neurochem. 1999;72(4):1466–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yu Y, Zhang Z-H, Wei S-G, Chu Y, Weiss RM, Heistad DD et al. Central gene transfer of interleukin-10 reduces hypothalamic inflammation and evidence of heart failure in rats after myocardial infarction. Circulation research. 2007;101(3):304–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.148940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Segiet A, Smykiewicz P, Kwiatkowski P, Żera T. Tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 10 in blood pressure regulation in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Cytokine. 2019;113:185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jiang N, Shi P, Desland F, Kitchen-Pareja MC, Sumners C. Interleukin-10 inhibits angiotensin II-induced decrease in neuronal potassium current. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2013;304(8):C801–C7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00398.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hernanz R, Martínez‐Revelles S, Palacios R, Martin A, Cachofeiro V, Aguado A et al. Toll‐like receptor 4 contributes to vascular remodelling and endothelial dysfunction in angiotensin II‐induced hypertension. British journal of pharmacology. 2015;172(12):3159–76. doi: 10.1111/bph.13117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ji Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Liu N. Angiotensin II induces inflammatory response partly via toll-like receptor 4-dependent signaling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2009;23(4–6):265–76. doi: 10.1159/000218173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Beutler B TLR4 as the mammalian endotoxin sensor Toll-like receptor family members and their ligands. Springer; 2002. p. 109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]