Abstract

3D bioprinting techniques have shown great promise in various fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Yet, creating a tissue construct that faithfully represents the tightly regulated composition, microenvironment, and function of native tissues is still challenging. Among various factors, biomechanics of bioprinting processes play fundamental roles in determining the ultimate outcome of manufactured constructs. This review provides a comprehensive and detailed overview on various biomechanical factors involved in tissue bioprinting, including those involved in pre, during, and post printing procedures. In preprinting processes, factors including viscosity, osmotic pressure, and injectability are reviewed and their influence on cell behavior during the bioink preparation is discussed, providing a basic guidance for the selection and optimization of bioinks. In during bioprinting processes, we review the key characteristics that determine the success of tissue manufacturing, including the rheological properties and surface tension of the bioink, printing flow rate control, process-induced mechanical forces, and the in situ cross-linking mechanisms. Advanced bioprinting techniques, including embedded and multi-material printing, are explored. For post printing steps, general techniques and equipment that are used for characterizing the biomechanical properties of printed tissue constructs are reviewed. Furthermore, the biomechanical interactions between printed constructs and various tissue/cell types are elaborated for both in vitro and in vivo applications. The review is concluded with an outlook regarding the significance of biomechanical processes in tissue bioprinting, presenting future directions to address some of the key challenges faced by the bioprinting community.

I. 3D TISSUE BIOPRINTING

Across the world, many people suffer from tissue and organ failure as a result of various diseases or traumas.1 Presently, the main remedy for patients with dysfunctional organs is tissue or whole organ transplantation that has saved many people's lives since the second half of the 20th century.2,3 However, severe shortage of available donors and logistical constraints have deemed tissue and organ transplantation as an inefficient approach for an ever increasing number of patients on the waiting lists.4 Along with organ transplantation procedures, therefore, massive efforts have been focused on the development of novel therapies to restore the structure and function of damaged or diseased tissues. Tissue engineering has emerged and advanced rapidly as a promising alternative approach with the ultimate goal of mitigating the critical shortage of donor organs by creating functional tissue and organ replacements.5,6

Tissue engineering combines knowledge and technology from multiple fields to design and develop three dimensional (3D) constructs, i.e., scaffolds, that are utilized either to substitute damaged or diseased tissues in regenerative medicine application, or as reliable biomimetic platforms for in vitro modeling of various biological processes, diseases, and therapies.7 Traditionally, engineered techniques for tissue fabrication include solvent casting and particulate leaching,8 gas foaming,9 phase separation,10 melt molding,11 and freeze drying.12 However, these techniques have limitations, including low resolution, poor processing control, and harsh manufacturing conditions, thus facing major constrains to create tissue constructs with a biomimetic environment and function.13 Development of new tissue manufacturing strategies that address these issues is highly sought after.

3D bioprinting is an emerging promising technique for the fabrication of functional tissue substitutes and platforms.14 As an additive manufacturing method, 3D bioprinting utilizes various types of bioinks to generate complex biological structures. Bioinks are prepared by mixing biomaterials, typically in the form of hydrogel polymers, with the desired cells and/or macromolecules (e.g., growth factors).15–17 Following the basic principles of additive manufacturing, bioprinting deposits or assembles bioinks in a layer-by-layer manner to create 3D tissue constructs that closely correspond to the designed model.13 Unlike traditional methods, 3D bioprinting utilizes automated, robotic manufacturing technologies, offering a relatively mild tissue fabrication environment at higher levels of consistency and reproducibility, throughput, and spatial control.18 These unique features enable creating complex biomimetic constructs for a wide variety of tissue engineering applications.19–21

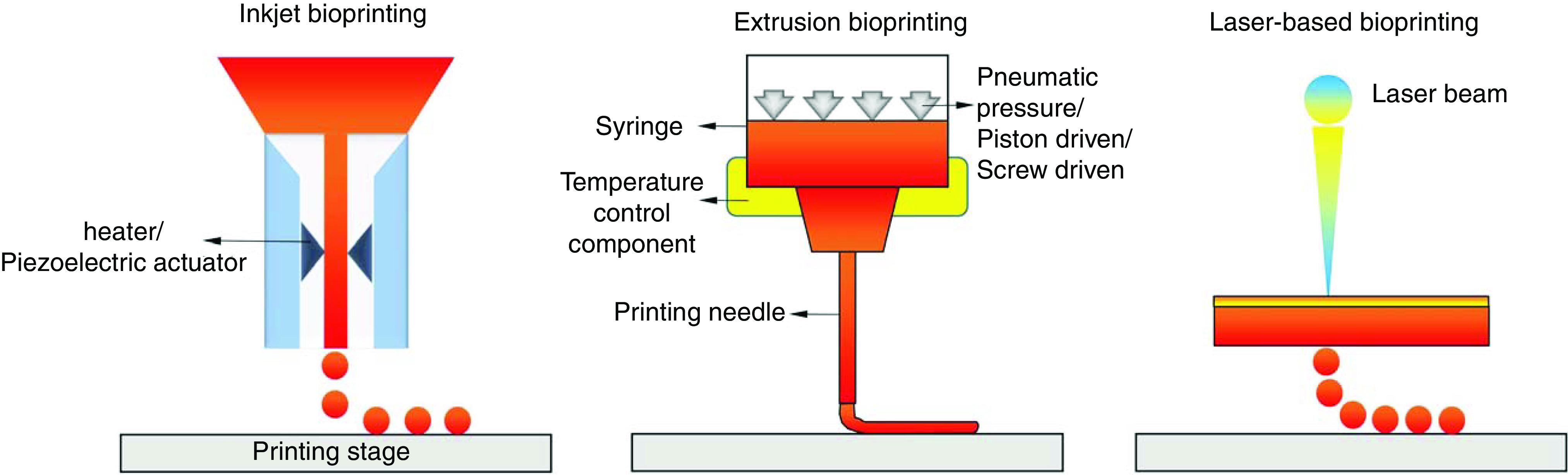

Based on the fabrication mechanism, 3D bioprinting techniques are typically classified into inkjet, laser-assisted, and extrusion-based printing (Fig. 1).13 Inkjet-based bioprinting adopts the idea from commercial 2D printers, where loaded bioink in a reservoir is formed as droplets and jetted, thermally or acoustically, onto a stage to form 3D constructs in a layer-by-layer manner.22–24 Inkjet bioprinting offers fast fabrication speed and resolution (approximately 50 μm), but it can only work with liquid inks with a low fluidic viscosity and cell density.25,26 Laser-assisted bioprinting techniques follow the principles of laser-induced forward transfer, where bioinks are propelled and patterned using a laser beam.27 During the bioprinting process, laser pulses are generated and irradiated onto the bioink, coated on an energy-absorbing substrate. This targeted irradiation generates high pressures that propel the bioinks onto a collector stage, forming 3D constructs.28 Laser-assisted bioprinting offers a relatively high printing resolution (few micrometers) and is feasible for bioinks with a range of viscosities.29 Since printing is performed without the use of a needle (as nozzle), there is no issue with clogging. However, laser-assisted bioprinting is limited by the low printing efficiency due to the compromised flow rate and the rather laborious preparation of energy-absorbing substrate.30 The most common bioprinting technique, extrusion-based bioprinting, utilizes bioinks that are extruded or dispensed continuously as filaments to form 3D structures.31 A typical extrusion bioprinter is constituted of extrusion head(s), a positioning-control component, and a temperature-control component. During the printing process, bioinks loaded in the dispensing head are extruded by either pneumatic or mechanical forces, through a print needle to form continuous filaments.32 The movement of the dispensing head is controlled in three dimensions by the position-control component (Fig. 1). By controlling the dispensing, positioning, and temperature through a computer interface, constructs will be stacked layer-by-layer following the design. Compared to inkjet and laser-assisted mechanisms, extrusion bioprinting can manipulate a wide array of bioinks that are made of diverse biomaterials and cell types, as well as printing at biologically relevant cell densities and at large scales.33

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the main 3D bioprinting strategies, including inkjet (left), extrusion (middle), and laser-based (right) bioprinting.

Although tissue constructs fabricated via extrusion bioprinting have been extensively used for in vivo tissue regeneration or as in vitro platforms for modeling and screening applications,34 creating a tissue construct that faithfully represents the complex composition and microenvironment of the native tissue is still challenging. Among different factors, biomechanical aspects of tissue bioprinting, related to the processes that occur before, during, and after bioprinting, play a fundamental role in determining the quality and fidelity of printouts. This review focuses on the biomechanical aspects of extrusion-based bioprinting, with a detailed description of the entire procedure. Prior to printing, we discuss about the significance of viscosity, osmotic pressure, and injectability, and their influence on cells during bioink preparation. During bioprinting, the key biomechanical factors including the rheological properties of the bioinks, the surface tension in bioprinting, bioprinting flow rate control, printing process-induced mechanical forces, and the in situ cross-linking mechanisms are reviewed. The cutting-edge bioprinting strategies, including the utilization of a viscoplastic support bath in bioprinting are also reviewed. Post printing, we discuss the biomechanical properties of printed tissue constructs and the interactions between printed construct biomechanics and cells, both in vitro and in vivo. Finally, an outlook on the significance of the biomechanical parameters of tissue bioprinting is given, presenting some of the key challenges in tissue bioprinting currently faced by the bioprinting community and future directions to address those challenges.

II. BIOMECHANICAL PROCESSES PRE BIOPRINTING

Bioinks are a fundamental part of 3D tissue bioprinting. Depending on the specific applications for the manufactured tissues, bioinks are designed and developed to recapitulate the native tissue environment, a process that largely relies on the selection of proper biomaterials.35 Selecting optimal biomaterials, for use as bioink, may be a challenge because they must meet several strict criteria, including biocompatibility and bioactivity with associated cells, capability to be deposited (extrusion or inkjet) and conform to designed shapes, and exhibiting mechanical properties that stabilize the printed architecture.36 Among a variety of biomaterials, hydrogels are the most commonly explored in bioprinting, due to their high water content and physiomechanical characteristics that facilitates recreation of the native tissue extracellular matrix (ECM).37 Hydrogels consist of a crosslinked polymeric network that, depending on the source of their backbone polymeric material, is divided into two categories, natural and synthetic hydrogels (Table I).38 Natural hydrogels, such as alginate, collagen, gelatin, and fibrin, are derived from both mammalian and non-mammalian creatures.39 Mammalian-derived hydrogels normally show high biocompatibility and an ECM similar to that of human, thereby supporting cellular bioactivities. This is mainly due to the presence of natural ligands in these hydrogels, capable of cell adhesion and other functions. However, the use of natural hydrogels is restricted by their instability and poor mechanical properties, relatively quick degradation rates, and inadequate tunability.40 Synthetic hydrogels, on the other hand, are biologically inert and easily tailored with specific properties to suit different applications.41 They overcome some disadvantages faced by natural hydrogels, but pose issues of poor biocompatibility and may cause toxic or immunogenic events.42 As a result, using a single hydrogel type for bioink preparation is challenging in tissue bioprinting, leading to the development of strategies where composited hydrogels are used for hybrid bioink preparation and printing (Table I).43 Several reviews have thoroughly surveyed the current status of hydrogel bioinks for 3D bioprinting and their future directions from different perspectives, including the type of the hydrogel,44 hydrogel properties,24 printing fidelity,45 and their specific applications in biomedical engineering.31 Here, we aim to present a complementary review of the key biomechanical factors that govern different steps of hydrogel-based bioprinting, including the pre, during, and post printing stages (Table II).

TABLE I.

Biomechanical properties of typical hydrogel bioinks pre, during, and post 3D bioprinting and their applications.

| Bioink materials | Solvents used for bioinks | Rheological performance | Mechanical stiffness (modulus) | 3D bioprinting applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 0.9% NaCl; calcium free culture medium | Non-Newtonian shear thinning, described by a power law model | 1.17–12.53 kPa | Schwann cells; human mesenchymal stem cells | 46–48 |

| Alginate and gelatin | Culture medium | Embedded printing; loss tangent between 0.25 and 0.45 | 54.6–64.1 kPa | Fibroblasts | 49 and 50 |

| Alginate, fibrin, and hyaluronic acid | 0.9% NaCl | Shear thinning, cross-linking bath | 1.28–2.61 kPa | Schwann cells and neurons | 43 and 51 |

| Oxidized alginate and gelatin | Water; PBS; culture medium | Loss tangent between 0.24 and 0.28 | 3–9.2 kPa | Endothelial cells; human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells | 32 and 52 |

| Chitosan-based hydrogel | Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Semi-solid under temperature control; shear thinning | 1.59–300 kPa | Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells; chondrocytes | 53–55 |

| Hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel | PBS | Shear thinning and self-healing | 15.7–20.8 kPa | Fibroblasts | 56 |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and gellan gum | PBS | Pseudoplastic shear thinning | 40–160 kPa | Murine bone marrow stromal cells; mouse osteoblastic cells | 57 |

| GelMA | PBS | G′ > G″ by cooling; embedded printing; | 5.9–36.4 kPa | Endothelial cells | 58 and 59 |

| GelMA and gelatin | Water and culture medium | G′ > G″; shear thinning | 1.67–264.74 kPa | Bone marrow stem cells | 60 |

| GelMA and Hyaluronic acid methacrylate (HAMA) | PBS | G′ > G″; shear thinning | 25–155 kPa | Osteocyte cells | 61 |

| GelMA and gellan gum | PBS | High yield stress with shearing thinning in a large temperature range | 2.7–186 kPa | Equine chondrocytes | 62 |

| GelMA and methylcellulose | Na2SO4 solution | High yield stress | ∼15 kPa | Human primary osteoblasts | 63 |

| GelMA and Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) | Cell culture medium | Strong shear thinning at 25 °C | 40–120 kPa | Mouse myoblast cells | 64 |

| Collagen and agarose | Acetic acid solution | Improved viscosity, shear thinning | ∼18.1 kPa | Corneal stromal keratocytes | 65 |

| Collagen and pluronic | Acetic acid solution | G′ > G″ by cooling | 0.03–6.98 kPa | Rat bone marrow derived stem cells | 66 |

| Fibrin and gelatin | Tris buffered saline; Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) | Shear thinning | ∼9.6 kPa | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes; human cardiomyocyte cell line; fibroblasts | 67 and 68 |

| Silk and gelatin | Culture medium | G′ > G″ by temperature optimization | 30–114 kPa | Chondrocytes | 69 |

| Decellularized ECM | Culture medium | Embedded printing | 0.5–15.74 kPa | iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes; HepG2 | 70–72 |

TABLE II.

Biomechanical factors and summary of their significances for pre, during, and post bioprinting processes.

| 3D bioprinting | Biomechanical factor | Summary of significances | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre bioprinting | Osmotic pressure | • Cells absorb water in a hypotonic solution, resulting in cell burst. | 75, 76, 80, and 81 |

| • Cells lose water in a hypertonic solution, resulting in cell shrinkage. | |||

| • Cells can be protected from osmosis by using physiological buffer as a solvent, gel coating on cells, and adding chemically inert osmotic regulators. | |||

| Viscosity | • Higher viscosity increases bioink preparation time required to achieve homogenously distributed cells/biological reagents. | 82 and 83 | |

| • Higher shear stress levels are generated when preparing more viscous bioinks, which may cause the rapture of cellular membrane and cell death. | |||

| • Viscosity affects the injectability of a bioink. | |||

| Injectability | • It ensures that prepared bioink can be injected/extruded in an even flow without clogging. | 84 | |

| • Regulating the bioink viscosity or the needle size can adjust the injectability. | |||

| During Bioprinting | Flow pattern | • Bioinks normally exhibit non-Newtonian flow, those exhibiting shear thinning are preferred for bioprinting. | 51 and 62 |

| • Bioinks with certain level of yield stress (yield-pseudoplastic) can improve the printing fidelity and preserve the stability of 3D structures. | |||

| Viscosity | • Bioinks with viscosity ranges 30 mPa/s to 6 × 107 mPa/s are compatible for 3D bioprinting. | 41 and 85–87 | |

| • Higher viscosity better supports the bioprinted structure but may restrict cellular functions; lower viscosity provides a cell friendly environment but limits printability. | |||

| • Viscosity alone cannot capture the entire behavior of a bioink; a high viscosity does not guarantee a high printing fidelity. | |||

| • Viscosity can be well controlled by regulating hydrogel concentration, cell density, additives, temperature, and pre-cross-linking. | |||

| Viscoelasticity | • Storage and loss moduli are used to report viscoelasticity. | 32 and 88–91 | |

| • Bioinks with higher storage modulus show more solid-like behavior, which supports the structural stability, but may cause impairments like clogging and discontinuous filaments. | |||

| • Bioinks with higher loss moduli can be easily manipulated, but face challenges in forming 3D structures. | |||

| • Certain ranges of loss tangent values have been reported to support printability, but these ranges are not universal and are bioink dependent. | |||

| • Viscoelasticity can be regulated following the same strategies used for viscosity. | |||

| Time dependency vs. Time independency | • Time dependency of bioinks is normally identified via time sweep, given a certain shear strain or frequency. | 92 and 93 | |

| • Rheological properties of bioinks are altered during a timescale when they exhibit time-dependent behavior. | |||

| Surface tension | • Bioink is expected to have surface tensions that can allow their detachment from the surface of the needle tip, while enabling them to resist the surface tension-driven droplet formation. | 51, 94, and 95 | |

| • Surface tension is closely related to contact angle of printed filament in the first layer; a large contact angle preserves the shape fidelity, while a smaller angle helps to anchor the layer. | |||

| • Contact angle can be adjusted by adding the second material into the bioink or changing the wettability of the bioprinting substrate by coating. | |||

| Flow rate | • Flow rate significantly influences the diameter of printed filaments. | 96 and 97 | |

| • Flow rate is determined by the flow behavior of the bioink, and the bioprinting control parameters including printing pressure, needle size, and temperature. | |||

| Process-induced mechanical forces | • Mechanical forces, including hydrostatic pressure, shear stress, and extensional stress, can induce cell damage, where shear and extensional stresses are more destructive. Lower stress levels may reduce cell damages and maintain higher cell viability. | 47 and 98 | |

| • The bioprinting process-induced mechanical forces can be controlled by the rheological properties of bioinks, the printing pressure, and the needle size. | |||

| In-situ cross-linking | • Bioinks can be solidified using temperature control, atomized cross-linking, agent medium cross-linking, and light cross-linking. | 13 and 56 | |

| • In-situ cross-linking makes it possible for low viscosity bioink printing, but due to the dynamic cross-linking process, the printing fidelity is normally compromised. | |||

| Post Bioprinting | Post-print (secondary) cross-linking | • Normally applied to increase the stability of bioprinted constructs. | 99 |

| • Mechanical properties of printed constructs can be well adjusted during post cross-linking. | |||

| Stiffness | • It is the extent to which an object resists deformation in response to an applied force. Elastic modulus is normally used to report the stiffness of printed constructs. | 48 and 100–103 | |

| • Can be regulated by hydrogel type, concentration, cross-linking, cell-hydrogel interactions, porosity, and degradation. | |||

| • Can significantly affect various cell functions, including cell differentiation, migration, angiogenesis, contractile function (e.g., cardiomyocytes), and intercellular connectivity. | |||

| • Bioprinted structures with stiffness approaching that of the native tissue are preferred. | |||

| Viscoelasticity | • Can be affected by hydrogel type and concentration, cross-linking, cell-hydrogel interactions, porosity, and degradation. | 104 and 105 | |

| • It determines the structural stability and integrity, while it affects the functions of cells such as cell spreading, proliferation, and differentiation. | |||

| Poroelasticity | • Stress relaxation can be used to identify poroelasticity of a bioink. | 106 | |

| • Characteristics, including shear modulus and diffusivity, are used to describe poroelasticity. | |||

| • Poroelasticity is a function of hydrogel type and concentration, cross-linking, porosity, and degradation. | |||

| • It determines the diffusivity of a bioprinted structure which is highly important for the metabolism of the encapsulated cells. | |||

| Degradation and ECM remodeling | • Degradation could result in enhanced intercellular connectivity, facilitated ECM secretion and remodeling, fusion/assembly of cellular structures, angiogenesis, and cell migration. | 87, 107, and 108 | |

| • Excessive degradation could result in the deterioration and collapse of printed architectures. | |||

| • Can significantly alter retention/release of therapeutics in bioprinted scaffolds. | |||

| • An ideal degradation rate should match the ability of cells to secrete ECM proteins to replace the degraded materials. | |||

| • Degradation byproducts should be nontoxic and easily cleared from the structure. |

Typically, pre bioprinting processes begin with dissolving hydrogels and suspending cells (and/or other biological factors) for bioink preparation. Unlike other non-biological inks, creating a uniform bioink mixture, while maintaining cellular viability and function during the entire printing process are substantial requirements for successful tissue bioprinting. Therefore, a bioink must provide a suitable environment, generally including a mild temperature (ranging from 4 °C to physiological temperature34,73) and a balanced pH with no cytotoxicity. From a biomechanical viewpoint, a bioink is required to also provide isotonic conditions with balanced osmotic pressure to protect cells from lysis due to either losing or absorbing water. Bioinks must also exhibit appropriate viscosity which allows the homogenous suspension of cells and reagents during mixing without causing severe mechanical stress (Table II). Osmotic pressure is defined as the hydrostatic pressure required to stop the flow of water across a membrane separating media of different compositions.74 When solutions are separated by a membrane which is permeable to the water, and not to the solute, the water tends to be driven by the osmotic pressure through the membrane to the solution with higher density of solute to equalize the water activity. Like all phospholipid bilayers, the biological membranes of cells are permeable to solvents like water, but impermeable to the solutes such as ions.75 As a result, cells will swell when they are hosted in a hypotonic solution, where the concentration of solutions is lower than it is in the cytosol. Such water absorption will lead to the stretching tension of cell membranes.76 When such tension reaches a critical magnitude, pores will appear on the cell membranes, leading to cell burst by osmotic flow and finally osmotic lysis. On the other hand, when cells are suspended in a hypertonic solution, where the concentration of solution is higher than that in the cell cytosol, water will leave cells and cause cellular shrinkage. Evidence indicates that the osmotic stress, generated under both hypotonic and hypertonic conditions, strongly hampers the interactions between cells and inhibits their proliferation.77 Therefore, in the case of cell bioprinting, it is essential to maintain the bioink solutions in an isotonic state to protect cells from osmosis (i.e., the concentration of solutes in bioinks is equal to the concentration of solutes inside the cells).

Maintaining osmotic balance during bioink preparation is often achieved using culture media, instead of water, as a solvent for hydrogels. The ionic concentration of a cell culture medium, or any physiological buffer used to dissolve hydrogels, is usually adjusted to 290–320 mM to prevent osmotic stress.78 However, in some cases using the culture medium may cause unexpected reaction with hydrogels and generate products or sediments that are harmful to the cells. Examples include formation of gel particles when alginate is dissolved in a standard culture medium containing calcium ions,79 or formation of precipitates when carbopol is reactive with divalent and trivalent cations in the medium or buffer.50 Besides using an ionic-balanced medium, a strategy of coating cells with gels has been adopted to protect cells from osmotic pressure.80 Under hypotonic conditions, the added gel coating provides extra stiffness on cells under osmotic pressure, resisting the rupture of the cell membrane and therefore preserving the intracellular functions. Another approach to protect cells from osmotic pressure is to add chemically inert osmotic regulators, such as sucrose, during bioink preparation.81 Proper regulation of the sucrose concentration in the bioink has been shown to help preserve and enhance cell viability, compared to the control groups where the hydrogel is dissolved in physiological buffer solutions.

Bioink viscosity is another key factor for determining the quality of bioprints, particularly during bioprinting, which will be discussed in detail in Sec. III. This fluid flow parameter also plays a key role in bioink preparation, in the pre bioprinting phase. Bioink viscosity can be evaluated from the ratio between shear stress and shear rate when the bioink is under shear.109,110 A high viscosity hydrogel can cause difficulties in cell suspension and distribution when manually mixing cells in the hydrogel, extending the time to achieve a homogeneous suspension of cells (or other reagents) due to the thickness of the solution. This results in the increased and prolonged exposure of cells to the shear stress. Although cells can resist a certain level of deformation due to their elastic abilities, as dynamic structures with specific functions, cell membrane may succumb once the stress exceeds a physiological threshold, leading to cell injury.46,82 This failure of cell membrane causes cellular dysfunction and damage, which subsequently leads to the reduction of cell viability. Lower viscosity bioinks, on the other hand, are more compatible with cells during the mixing and preparation procedures. In these hydrogels, the homogenous distribution of cells can be more readily achieved, while generating lower levels of shear stress compared to more viscous bioinks. However, lower viscosity bioinks may face technical challenges in maintaining shape and structural stability during bioprinting processes, which will be discussed in Secs. III and IV.111

Injectability, which refers to the force or pressure needed for activation of the materials for injection, is another factor that can be examined in the pre bioprinting stage.112 Injectability is important as it describes the capacity of a prepared bioink to be injected or extruded in an even flow without clogging. This property has been studied both qualitatively and quantitatively. To measure the injectability of a bioink, one common method used is to track the force needed to push the bioink through a needle that is connected to a syringe where the bioink is loaded.84 The force–displacement curve is normally recorded for the quantification. Other methods such as measuring the mass of bioinks expelled from the syringe,113 or determining the time required to smoothly inject a bioink under a preset force or pressure,114 have all been used. For a given testing system (e.g., syringe and needle), the injectability is dominated by the properties of the bioink, such as its viscosity. A higher viscosity normally requires a larger force to inject at a given plunger speed. Thus, the injectability can be well regulated via the viscosity adjustment of the bioinks. For a given bioink, the injectability is significantly affected by the size of the needle.115 From the injection assessments, the needle with the appropriate size and shape can be identified for the bioprinting steps.

III. BIOMECHANICAL PROCESSES DURING BIOPRINTING

During the bioprinting phase, bioinks are deposited following the path governed by the designed model to form a 3D structure. Throughout this dynamic process, several biomechanical parameters, including the rheological properties of bioinks, surface tension, printing flow rate, and bioinks cross-linking/solidification, critically define the success of 3D bioprinting (Table II). Additionally, a successful bioprinting process should maintain a high viability of cells in the bioink, which is directly related to the bioprinting process-induced mechanical forces.

A. Rheological properties of bioinks

Merely meeting the biocompatibility requirements is not sufficient for a material to be used as an optimal bioink for use in different bioprinting modalities. Selected bioactive materials must also be printable. Bioprintability is a relative concept that is investigated using both qualitative and quantitative methods.116 It refers to the ability of a bioink to be extruded (or assembled using other print strategies) to form a 3D tissue construct that shows high structural agreement with the designed model.90 This requirement highlights the substantial role of bioink mechanical properties which are often examined in terms of rheological behavior (Table II).

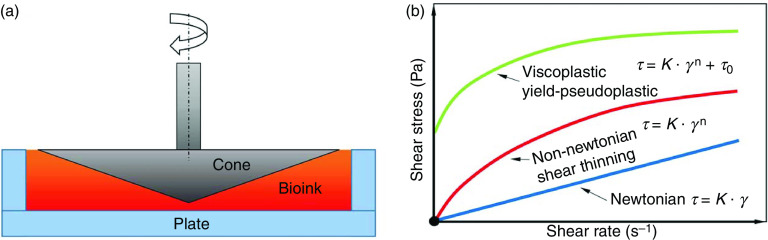

Rheology studies the deformation or the flowing response of a material to the applied force or stress. Tables I and II summarize the rheological behavior of typical hydrogel bioinks in 3D bioprinting. The rheological behavior of materials is typically evaluated using cone-and-plate or capillary rheometers [Fig. 2(a)].12,117 Basic requirements for a bioink in 3D bioprinting include a smooth flow under controllable pressure/stress and sufficient self-support to form and maintain the 3D structure.59 Therefore, examining the flow behavior of the bioink is of great significance. The flow behavior of a hydrogel, which indicates its resistance to deform, is characterized by the relationship between shear stress and shear rate. Depending on this relationship, flow behavior is generally classified as Newtonian and non-Newtonian [Fig. 2(b)].118 Most hydrogel-based bioinks exhibit non-Newtonian behavior, where the relationship between shear stress and shear rate is nonlinear.51 The non-Newtonian hydrogels that also display shear thinning are preferred for bioprinting. The flow behavior of a shear thinning bioink typically forms a concave curve [Fig. 2(b)], where increasing shear rate leads to an increase in shear stress (greater than the proportional relationship). Shear thinning causes a decrease in viscosity in response to an increase in shear rate when the bioink is printed, which allows the solution to readily flow without causing clogging.43

FIG. 2.

Rheological properties of hydrogels and their significance in tissue bioprinting. (a) Schematic of a plate-and-cone rheometer. (b) Different types of flow behavior for hydrogels.

In addition to shear thinning behavior, the fluid viscosity, is an important parameter in determining bioink printability (Table I).109,110 Different bioprinting systems (i.e., inkjet and extrusion) require varying viscosity ranges of bioinks to maintain printability. For extrusion bioprinting, bioinks with viscosities ranging from 30 mPa/s to over 6 × 107 mPa/s have been shown compatible for 3D bioprinting.31,85 Within this range, a higher viscosity normally represents a stiffer bioink, which could provide a stronger support to form stable structures.41 However, elevated viscosities will restrict cellular functions and cause considerable cellular damage. Low viscosity bioinks, on the other hand, often provide a more cell-friendly environment for incorporated cells, but will show poor printability.46 Thus, based on applications, the viscosity of the bioink should be precisely balanced to meet the printability requirement, while preserving the capability to support the desired cellular functions.

Evidence has shown that relying on viscosity alone may not capture the complex behavior of hydrogel-based bioinks,86 since a higher viscosity does not necessarily grant higher mechanical stability of bioprints.119 Hydrogel-based bioinks often exhibit viscoelastic behavior, i.e., displaying both viscous and elastic characteristics when undergoing deformation.120 The viscoelasticity of a bioink is normally measured based on dynamic mechanical analysis, where frequency or strain sweeps are normally applied using a rheometer to search for the storage and loss moduli (G′ and G″, respectively).88 These oscillating tests are conducted with fixed strain and increased frequency, for frequency sweep, or reversely for the strain sweep. G′ and G″ are the key parameters in representing the viscoelastic behavior of a bioink, with G′ describing the elastic aspect of the bioink and G″ (90° phase lag of strain with respect to stress) contributes to the viscous aspect. When G′ > G″ the bioink has a more solid-like behavior and G″ > G suggests a more liquid-like behavior. A solid-like bioink, with a large G′, shows a greater material strength, which is preferred in bioprint stacking, but may lead to impairments during bioprinting, such as clogging, discontinuous filaments, and nonuniform strands.89 Bioinks with larger G″ are readily extruded, but due to their liquidity, forming designed 3D structures without extra support can be challenging. Thus, bioinks with large G′ values are usually prepared to preserve the printing integrity. Determining appropriate G′ and G″ values to ensure a smooth bioink extrusion would be a more accurate and reliable approach than using a single parameter of viscosity.90 For instance, the respective ratio of G′ and G″, or the loss tangent δ, has been used to predict the efficacy of alginate–gelatin bioinks.49 When the loss tangent is within the identified boundaries, bioinks can easily form 3D structures with high stability and integrity.32 Notably, there is no universal loss tangent value for different bioinks, especially when they exhibit yield stress.121 For example, Pluronic F127 exhibits viscoplastic behavior, where flowing may not commence until a threshold value of stress, known as the yield stress, is exceeded.62 Although the loss tangent for pluronic is near zero, which is far from the printable values identified for alginate and gelatin, this sacrificial bioink still shows desired printability. This is due to the fact that pluronic exhibits shear thinning during the extrusion, and shows a yield stress to maintain the structural integrity after deposition.89,90

In some cases, the rheological properties of a bioink are not only determined by the shearing conditions during the testing, but also influenced by the time period during which the bioink is exposed to shear. These materials are known as time-dependent bioinks.92 For hydrogel-based bioinks that exhibit time-dependent behavior, considering only the rheological properties in a time-independent manner would not capture their entire performance. Gelatin or gelatin-based hydrogel precursors, for example, are biocompatible materials.60,93,122 They possess thermosensitive properties, liquifying at body temperature (37 °C) and gelling at lower temperatures. When the temperature changes, gelatin-based bioinks require some time to reach a steady state at a given temperature; therefore, they will show gradually altering viscoelastic properties under shearing. As such, viscoelastic analysis of gelatin-based bioinks requires temperature control to tune the values of G′ and G″. In order to achieve this, a temperature sweep, consisting of either a heating or cooling procedure, is normally conducted to examine G′ and G″ as a function of temperature.123 The intersection point of G′ and G″ curves is normally identified as the transitional temperature, where the examined bioinks start to gel or liquify. Based on the results from the temperature sweep, one would prefer a temperature lower than the intersection point for bioprinting, which produces larger G′ compared to G″. However, information obtained from the temperature sweep is not enough to precisely identify the printable temperature range since gelatin-based bioinks exhibit a time-dependent behavior. For this, a time sweep is additionally performed to track the trends of G′ and G″ values within a timescale at a given temperature.51 The time period required for the two modulus values to reach the plateau region is normally recorded and used for heating/cooling before bioprinting.59

It is essential that the rheological behavior of bioinks meets the requirements during bioprinting, therefore tailoring the rheological behavior of hydrogel inks is necessary.124 Many approaches have been used to tune rheological properties, with the most common one being modulating the concentration of the hydrogel.87 A bioink with a higher hydrogel concentration contains more particles or molecules within the unit volume of solution, introducing more interactions which create a more viscous solution.91 Adjusting the rheological behavior by adding or reducing the amount of the hydrogel is simple, but biocompatibility issues may arise when large quantities of the materials are added. To address this concern, an alternative approach utilizes uniform mixing of multiple types of hydrogels to form a hybrid bioink.125 This approach takes advantage from individual hydrogel types in the mixture that are either biocompatible or bioprintable. Through adjusting the ratio of each hydrogel component, a hybrid bioink can be eventually designed to be processable and functional for specific 3D bioprinting applications. For instance, hyaluronic acid is a biocompatible viscosity modifier that is widely used in 3D bioprinting. However, maintaining 3D structures made by pure hyaluronic acid is challenging. On the other hand, alginate exhibits rapid cross-linking to maintain structural stability of bioprinted constructs, but it lacks proper cell adhesion sites and excessive alginate content would hinder the growth of cells.48 Fibrin is another protein-based hydrogel that provides biological cues for cell attachment and growth, but has poor printability due to limited rheological properties (viscosity). By mixing these three hydrogels in an appropriate ratio (0.5% hyaluronic acid, 1% alginate, and 4% fibrin), a hybrid bioink can be successfully bioprinted into desired patterns while maintaining viable and functional Schwann cells and Dorsal root ganglion neurons.51 In-situ cross-linking has been also used to tune the flow behavior of bioinks.54 This method is usually applied to hydrogels with poor printability that can be crosslinked during the printing process via ionic or photo polymerization.126 The partial cross-linking increases the viscosity of deposited bioink and can therefore help increase printing fidelity of hydrogels. Temperature control is another approach used to regular the flow behavior, as increasing or decreasing temperature can change the kinetics or thermal energy of the molecular bonds that are responsible for the flow behavior of a bioink.109 Increasing the temperature normally increases molecular mobility and reduces binding energy, leading to a decrease in fluid viscosity. For thermosensitive hydrogels, temperature regulation is necessary.63 Finally, the effect of cells on the rheological behavior of bioinks must be explored. The density of encapsulated cells is one of the key factors that can be tuned to tailor the flow behavior of bioinks.127 Cells that are mixed within a bioink can be considered as non-soluble microparticles, transforming the hydrogel solution from a single phase to a two phase fluid. The interactions of such particles with the hydrogel can, therefore, significantly change the viscosity and viscoelasticity of the bioink.79

B. Surface tension in 3D bioprinting

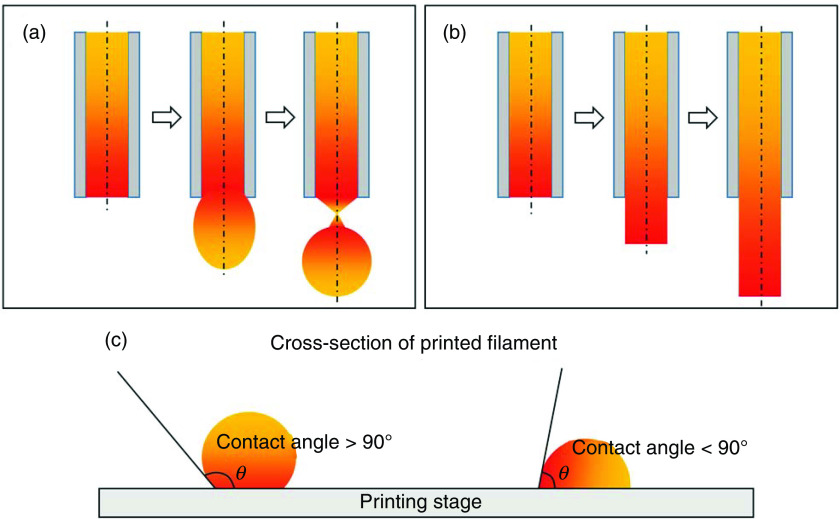

In 3D bioprinting, needles with small diameters (hundreds of micrometers) are usually used as nozzle to maintain the printing resolution. Therefore, the surface tension of a bioink, which results from the molecular interactions on the surface, with the same and adjacent materials, is highly significant during bioprinting (Table I).128 From the extrusion printability point of view, bioinks are expected to have surface tensions that can allow their detachment from the surface of the needle tip, while enabling them to resist the surface tension-driven droplet formation, to ensure the extrusion of a continuous filament [Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)].94 Since surface tension is determined by molecular interactions, temperature control and adding second materials, such as nanoparticles, have been used to adjust this property.89,129 The most common method to measure the surface tension is using a tensiometer. For 3D bioprinting purposes, however, an effective alternative method has been developed to assess the surface tension of bioinks during printing based on a relationship between surface tension and filament geometry (i.e., width, height, and cross-sectional area).130,131

FIG. 3.

Schematic of printed filaments. (a) Surface tension-driven bioink droplets at the outlet of the needle, (b) continuous filament after leaving the outlet the needle due to yield stress of the bioink, and (c) contact angle of the printed filament.

When bioprinting without extra structural support, the first layer of printed bioink is fundamental for the success of the entire biofabrication process, as it supports and guides the subsequent layers. The shape of the first deposited layer largely relies on the contact angle, which reflects the wettability of the solid substrate.121 On a given printing substrate, the contact angle is affected by gravitational forces, the surface tension between the filament and surrounding environment (air or support medium), and the surface tension between the filament and the printing substrate.132 Generally, a large contact angle (>90°) helps preserve the shape fidelity of the printed bioink in the vertical direction. On the other hand, smaller contact angles (<90°) introduce large deformations and bioink spreading but can help anchor the first layer onto the printing substrate and avoid undesired moves during bioink stacking [Fig. 3(c)]. Bioprinting substrates, such as glass or tissue culture dish, typically create large contact angles that develop a mobile first layer of printed bioink.95 To overcome this issue, one practical method is to coat the substrate with a thin layer of chemicals, such as 3-(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate or polyethyleneimine, to modify the printing surface properties, and decrease the contact angle.51

C. Volumetric flow rate in 3D tissue bioprinting

Bioinks are extruded into filaments which act as building blocks, determining the structural resolution and integrity of the printed constructs. In addition to surface tension, volumetric flow rate, i.e., the volume of printed bioink passing through the needle per unit of time, is essential for determining the shape of bioprinted filaments (Table I).43 Assuming the effects of hydrogel swelling and deformation can be ignored, the diameter of printed filament is theoretically determined using the following equation:96

| (1) |

where represents the diameter of printed filament, is the volumetric flow rate of bioink, and is the printing speed in the horizontal plate (Fig. 4). Large flow rates associated with low printing speeds increase the filament diameter, while small flow rates combined with high printing speeds reduce the size. For a given a flow rate, the printing speed is generally adjusted to extrude filaments at the diameter matching the inner diameter of the printing needle [following Eq. (1)]. This will help to avoid filament stretching or bioink accumulation.97 In 3D bioprinting, the flow rate is affected by printing process parameters, including the printing pressure, temperature, and needle type. Among these, tuning printing pressure is an effective way to regulate the flow rate. A larger pressure results in a higher flow rate. Temperature also controls the flow properties of the bioinks. A higher printing temperature normally introduces a larger flow rate at a given pressure. When the printing force and temperature are preset, the flow rate is significantly affected by the needle size.

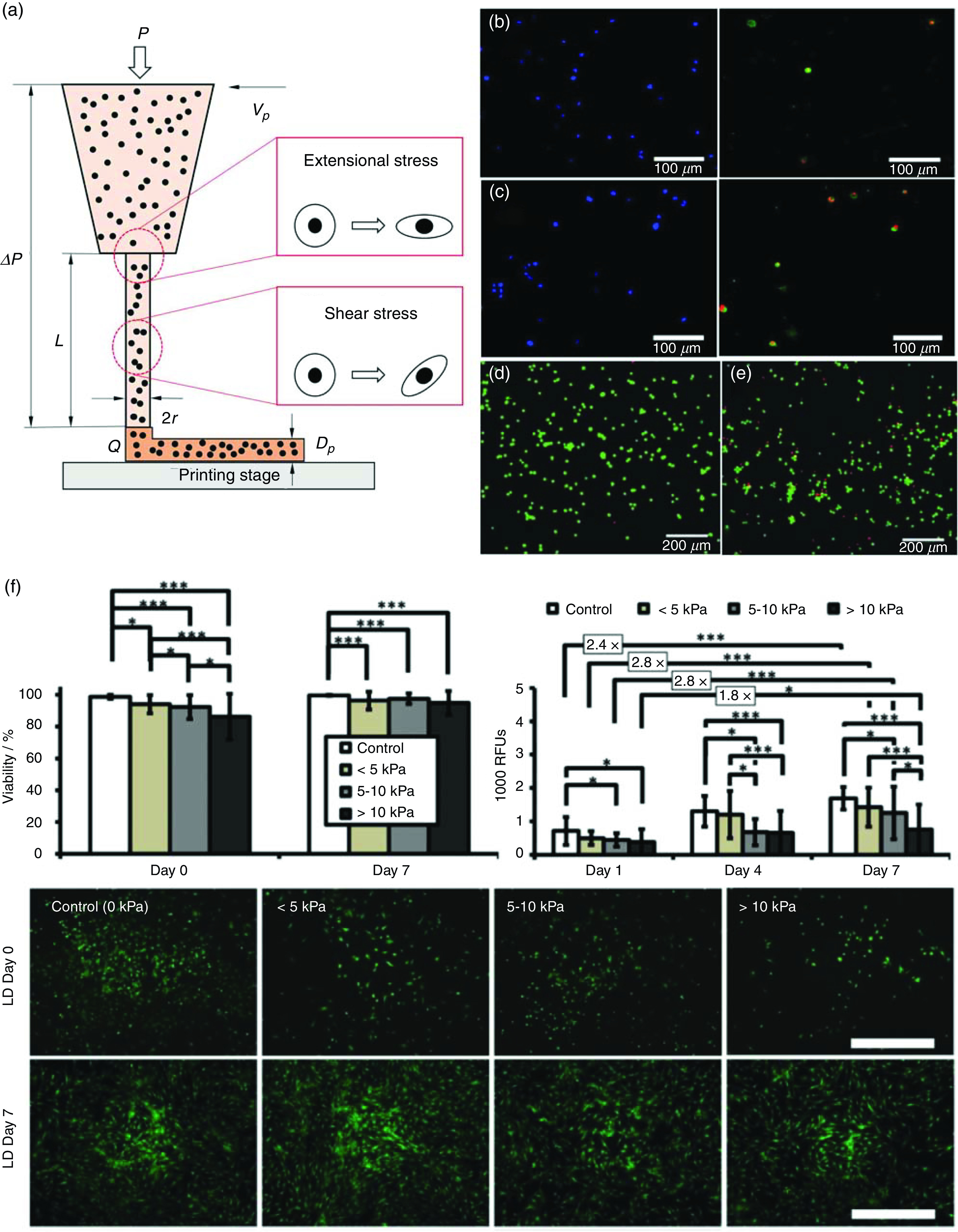

FIG. 4.

Examining cell deformation and damages under mechanical forces during 3D bioprinting. (a) Schematic illustration of the 3D bioprinting process and the mechanical stresses involved. (b) and (c) Schwann cell membrane rupture and damage in bioprinting with applied bioprinting pressures of 100 kPa (b) and 400 kPa (c). (d) and (e) Live/dead assay of fibroblasts under no shearing (d) and shearing [(e), 1700 Pa]. (f) Short-term and long-term impact of different bioprinting-induced shear stress levels on human mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) viability and proliferation. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (b) and (c) Reproduced with permission from Ning et al., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 3906 (2018). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.47 (d) and (e) Reproduced with permission from Ning et al., Tissue Eng., Part C 22, 652 (2016). Copyright 2016 Mary Ann Liebert.79 (f) Reproduced with permission from Blaeser et al., Adv. Healthcare Mater. 5, 326 (2016). Copyright 2016 John Wiley and Sons.46

Characterization of flow rate under the given conditions is of great importance. Experimentally, the volume of extruded bioink within a certain time duration is normally recorded for flow rate measurements. However, these methods are often time consuming and cannot capture the full characteristics of the bioink flow rate; hence, they may not provide an accurate assessment for the bioprinting processes.97 To address this issue, empirical models developed from experimental data have been used to study the flow rate, but they still require exhaustive experimental supports. Alternatively, several models have been established based on physical principles governing the micro-extrusion processes and have shown better efficacy and accuracy in predicting the flow rate. According to the rheological measurements obtained, the flow behavior of a bioink can be examined using a power law model, a Carreau model, an Ellis model, or a Herschel–Bulkley model, depending on the flow pattern as well as the specific applications.12 One of the extensively used models to depict the flow behavior of a bioink in bioprinting is the power law model, which states

| (2) |

where and are the shear and yield stress, respectively, is the shear rate, is the consistency index (Pa sn), and is the dimensionless flow behavior index. The state of the bioink in a cylindrical needle can be formulated according to the linear momentum balance, under the following assumptions: (1) the bioink is incompressible in the printing process; (2) the bioink inside the needle is fully developed with exhibited laminar flow; (3) there is no wall slip; and (4) the pressure drop in the syringe can be ignored

| (3) |

where is the printing pressure, is the pressure drop, and are the radius and length of a fluid element, respectively, and represents the shear stress of the element (Fig. 4). Considering the effect of surface tension, can be expressed as

| (4) |

where is the fluid surface tension (Pa/s). Based on these equations, the flow rate of a bioink can be given by118

| (5) |

where is the shear stress at the needle wall which can be obtained from

| (6) |

Equation (5) establishes the connection between the flow rate and printing pressure, needle size, and the bioink flow behavior. Thereupon, for a bioink with known flow behavior, a desired flow rate can be readily determined by regulating the printing pressure and needle diameter following the equation. Conversely, if a series of flow rates are obtained during the printing process, the flow behavior of the bioink, which can be expressed using a power-law model, can be identified based on Eq. (5).

D. Bioprinting process-induced mechanical forces

During bioprinting, a set of mechanical forces can be experienced by cells, which may elicit the deformation of cells and cause the breach of cell membranes, and possibly cell damage or death (Table I).133 The mechanical forces exerted on cells during 3D bioprinting generally include hydrostatic pressure, shear stress, and extensional stress.98,126 Hydrostatic pressure is generated due to the directly applied printing force. When a bioink is loaded in the printing syringe, the printing force generates a hydrostatic pressure on the cells suspended in the bioink, with a value approximating the applied printing pressure. Shear stress is generated within both the syringe and the needle, and is considered as one of the main causes for cell damage during bioprinting.134 Due to the much larger diameter of a syringe compared to that of a needle, the state of the bioink inside the syringe is normally considered as immobile with neglected shearing, while shear stress is dominantly distributed within the needle tip. Equation (6) shows the distribution of shear stress, which is dependent on the pressure drop and the position within the needle. It illustrates a linear distribution that changes along the radial direction of the needle, reaching a maximum at the needle wall, from zero at the centerline of the needle. Extensional stress is another important mechanical force to which cells are subjected, and is generated at the region of abrupt contraction of the needle, where the bioink velocity changes drastically.135 Compared to other types of forces, characterizing the extensional stress has proven challenging because of the difficulty in generating a flow that induces a pure extensional stress field. It would also require the development of methods for extensional stress expression and examining the effect of stress on cell damages.47

Depending on cell types, the viability of cells can drop to below 60% after bioprinting due to the process-induced stresses.136–138 The effects of hydrostatic pressure have been experimentally examined on Schwann cells, fibroblasts, and chondrocytes. Results suggest that the disruptive effects of hydrostatic pressure on cells are minor, unless the pressure reaches high levels (over 5 MPa) and is maintained for a long period (over 2 h).98 Since the hydrogel-based bioinks normally need much lower printing pressures and shorter times, the influence of hydrostatic pressure on cells is often insignificant. Under shear stress, cells will be first oriented and then pulled into a new balanced state (Fig. 4).139 To identify the effect of shear stress on cells, various cell suspensions have been sheared using cone-and-plate rheometers, which provide a pure shearing field with controllable shear stress magnitudes and shearing time.79 Results indicate that a larger shear stress, or a longer shearing period, introduces more damage to the cells. Thus, when higher levels of bioprinting pressure are used, greater shear stress values will be generated within the needle, leading to an increased percentage of cell damages.140 Compared to the shear stress, cells seem to be more vulnerable under extensional stress since it directly stretches cells along the loading axis that causes no rotation (Fig. 4).135 Since creating a pure extensional stress field is difficult, an indirect method has been developed to characterize cell damages under extensional stress. In this approach, cell damage caused by extensional stress is inferred from the difference between the total cell damage and the level of the damage attributed to the shear stress.47 Results from this method confirm the significant role of both shear stress and extensional stress on bioprinting associated cell damages.

Cell damage is dependent on the process-induced mechanical forces, and these forces are closely related to the printing parameters, including printing pressure, needle length, and diameter, as well as the bioink properties [Figs. 4(b)–4(f)].141 Generally, for a desired printing flow rate, a higher pressure is needed when a smaller needle is used. Such combination introduces greater levels of cell damages. Bioinks with higher viscosity require higher printing pressures in order to maintain a constant flow rate, thus leading to enhanced cell damages when printing these bioinks. Different mathematical models have also correlated cell damages to the bioprinting process parameters. For instance, the detrimental effects of printing pressure and needles on cells have been directly described using a phenomenological model which well corresponded with those quantified experimentally.142 This model shows its ability to predict the level of cell damage for a given cell type, however, it fails to describe the relationship between mechanical forces and cells. Another model indicates cell damage as a function of shear stress and shearing time.79,98 This method first finds a relationship between cell damage and shear stress/shearing time using a rheometer, and then models the bioprinting-associated shear stress experienced by cells when they pass through the needle. Finally, it calculates the damage in cells flowing through each streamline by integration. Meanwhile, the effect of extensional stress on cells has not been analyzed. To address this, a modified model assumes that cell damage in 3D bioprinting is due to the aggregated effects of both shear and extensional stresses.47 Since cell damage caused by shear stress can be calculated based on the established models, and also the total cell damage can be experimentally examined once cells are extruded out, the fraction of cellular damages attributed to the extensional stress can be therefore identified. Based on numerical fluidic analysis, the profile of extensional stress at the contractive region of the needle is calculated, therefore the relationship between external stress and cell damage can be established.

Preserving a high cell viability is one of the fundamental requirements for the subsequent applications of bioprinted tissue constructs. As cell damages are majorly attributed to the process-induced mechanical forces, methods that reduce these forces have been used for improving the survival of cells. A lower printing pressure is preferred to maintain cell viability as it reduces the stress, but it may to be impractical when printing high viscosity bioinks.143 At a given flow rate, lower cell damage is detected when using needles with larger diameters due to the lower printing pressure used. On the other hand, a larger needle reduces the accuracy of printing volume control and printing resolution, thus precluding some high precision applications.47 When a long-length needle is adopted, the time period of cells passage through the needle is increased, resulting in expanded shearing and therefore increased cell damage.98,139 Thus, a proper selection of printing pressure and needle type must be used to maintain high cell viability while meeting the requirements of printing accuracy for various applications. Compared to straight needle types, tapered needles avoid the abrupt shape change, thus greatly reducing the influence of extensional stress on cells. Additionally, the printing pressure used for bioprinting with a tapered needle is markedly lower to achieve a constant flow rate, compared to a straight needle at an identical diameter. As a result, using a tapered needle could significantly reduce cell damages.144 Meanwhile, the utilization of tapered needles may cause issues when low printing flow rates are required, especially for printing bioinks with low viscosity. Due to the low resistance of tapered needles, the bioink gravity, which is a force that drives the bioink down, increases the flow rate, and such combined effects make the flow rate difficult to control. Therefore, tapered needles are a preferred method for printing viscous bioinks because it ensures printing accuracy while maintaining adequate cell viability.

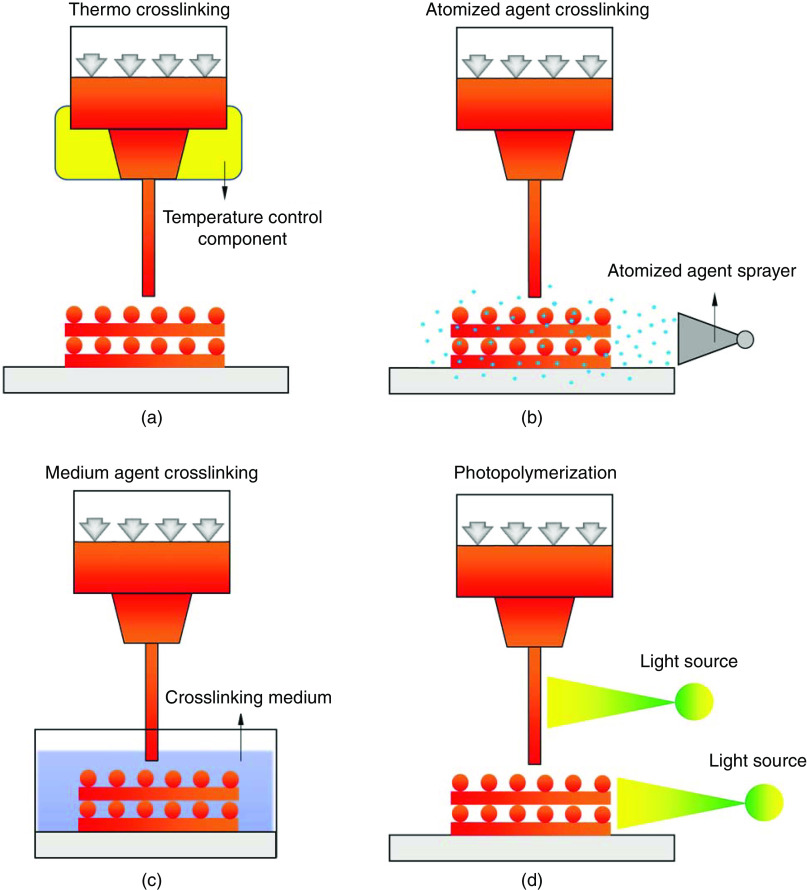

E. In situ hydrogel cross-linking

Hydrogel cross-linking refers to the process of material bonding between hydrophilic polymer chains to prevent dissolution of bioinks into the aqueous phase.145 It is a requisite step for bioink solidification, providing sufficient mechanical support to preserve the stability of constructs during and/or after 3D bioprinting.4 As the cross-linking approach will appear both during and after bioprinting, we discussed hydrogel cross-linking in two parts, and with the focus of this subsection on in situ cross-linking.

Right after deposition, bioinks are expected to provide sufficient mechanical support to maintain the 3D structural integrity. Considering the inherently poor mechanical properties of most tissue bioinks, methods of in situ cross-linking, which are the strategies of “printing while cross-linking,” are used to stabilize the extruded bioinks.43 There are various physical or chemical cross-linking approaches that have been applied for in situ hydrogel solidification, based on the hydrogel types. For thermosensitive hydrogels, like gelatin, the cross-linking process can be readily triggered via the control of temperature-regulated components [Fig. 5(a)].49 This method relies on the rheological behavior of the hydrogel itself in the printing process, and normally requires extra cross-linking methods later due to the reversibility under temperature changes. For bioinks that can be crosslinked through ionic bonding, one approach developed is based on the atomized cross-linking agent spraying [Fig. 5(b)].146 Atomized agent reaches the hydrogel surface to initiate the solidification, but due to the difficulty in spraying control, the distribution of the atomized agent on the printed structures is usually nonuniform. Additionally, the cross-linking efficacy is low due to the limited reacting agent in spraying, which raises the issues of low printing fidelity and stability, especially when bioinks with a low viscosity, large loss modulus, or small contact angle are used. Alternatively, an agent medium bath has been used to provide a fast and homogeneous cross-linking environment [Fig. 5(c)].147 The deposited bioink within the cross-linking bath is rapidly polymerized once it contacts with the cross-linking agent. Such immediate reaction significantly reduces the spreading of the bioink due to gravity and surface tension and improves the printing fidelity compared to printing with atomizing cross-linking. Meanwhile, a rigorous adjustment on the cross-linking bath is required to avoid printing failures which may be introduced by the buoyance of the cross-linking solution when the cross-linking rate is not appropriate.95 Excessive cross-linking rates introduced by high cross-linking agent concentrations can result in rapid stiffening of printed filaments, which would lose the connections between adjacent layers during bioink stacking, hence, reducing the structural stability. On the contrary, deficient cross-linking rates caused by a low concentration of cross-linking agent may result in compromised printing fidelity since the limited cross-linking rate cannot retain the shape of the printed hydrogel during the liquid–solid phase change.

FIG. 5.

In situ cross-linking in 3D bioprinting. (a) Thermal cross-linking; (b) cross-linking based on atomized agent spraying; (c) the use of a cross-linking medium; and (d) photopolymerization either after bioink deposition or via a light-permeable needle before extruding out.

In situ cross-linking approaches have also been used for photo-crosslinkable bioinks, where extruded filaments are either polymerized right after the deposition, or are crosslinked within a light-permeable needle right before extruding out [Fig. 5(d)].148,149 The former approach is more frequently used in 3D bioprinting, where a light source is installed in the printing system with controlled intensity and exposure time. However, due to limited cross-linking rates, maintaining the fidelity of printed filaments for this approach is not ideal; even when high light intensity and long exposure time are used, this cross-linking approach is still challenging for low-viscosity bioinks.56 It may also induce exceeded exposure to the first deposited layers, leading to extra stiffness and increased cell damage. On the other hand, the in situ photo-cross-linking prior to the extrusion, partially stabilizes the dynamic flow of bioinks within the needle, therefore creating filaments with improved stability and uniformity before deposition. As a result, it enables printing of low-viscosity hydrogel inks via the adjustment of light intensity and exposure time. This cross-linking approach is only valid with the utilization of light permeable needles, which are normally customized from glass or silicon. Also, an elaborate adjustment of the light source is crucial to maintain the uniform flow of bioink while producing sufficient mechanical strength.

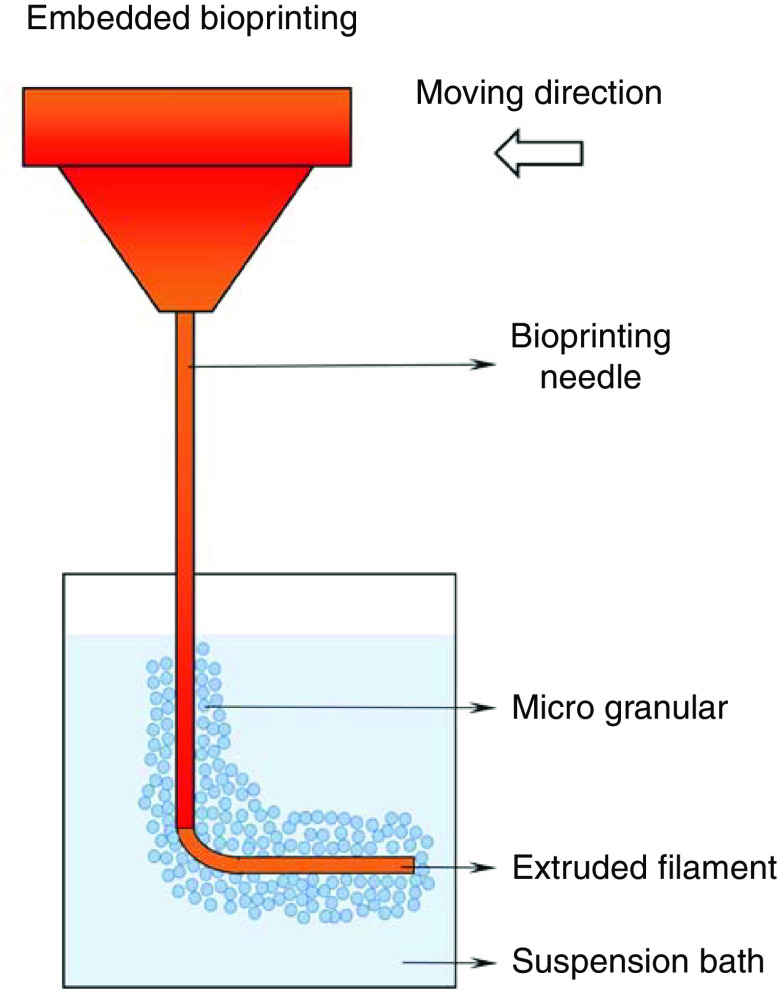

F. Suspension bath used to support bioink deposition

In situ cross-linking techniques alleviate the rigorous requirements on rheological properties of bioinks, allowing printing of low viscosity hydrogels that are difficult to manipulate independently. However, such bioprinting techniques are limited by the type of bioinks, to only those that exhibit rapid solidification. Even when printing bioinks with adequate cross-linking rates, maintaining high fidelity of printed filaments could be still challenging due to the time-dependent solidification procedure, especially when larger scale structures (more than several millimeters in size) with complex architecture are fabricated.150 Over the past few years, a new technique in 3D bioprinting, known as embedded bioprinting, has been developed and shown its great potential for soft hydrogel-based bioinks bioprinting.151 The difference between this technique compared to conventional bioprinting is the addition of a viscoplastic suspension bath, where bioinks are extruded into the bath, instead of being deposited on a flat substrate in the air (Fig. 6).152 Such a medium lifts and holds the shape of mechanically weak bioinks after deposition, while providing a cell-friendly environment to maintain the functions of cells. The preparation of a suspension bath that has the capacity for 3D embedded bioprinting must meet several principles. First, the medium must provide sufficient yield stress.153 The suspension bath possessing a proper yield stress exhibits solid-like behavior in the absence of or very low mechanical forces, such as gravity, making it possible to firmly hold printed constructs in shape with no structural collapse.154 The second principle is that the suspension should behave liquid-like shear-thinning once a shear stress that exceeds the yield stress is applied. During bioprinting, shear stress is introduced by the needle moving within the suspension, which initiates the transition of the medium from solid-like to a liquid-like phase. The shear-thinning behavior ensures the smooth movement of the needle and deposition of bioinks. The third principle is that the microstructure of the suspension medium can rapidly recover after the disturbance introduced by the passing needle and the displacement of bioink. The self-recovery permits the transition of the medium from the liquid-like state back to the solid-like state, thus properly maintaining the deposited material and ensuring the fidelity. This behavior is also known as thixotropy, and media with limited thixotropic time is suitable for the utilization in embedded bioprinting (Table I).153 The fourth principle is that the suspension medium should provide a cell-friendly environment for cells after deposition.

FIG. 6.

Embedded bioprinting technique using a suspension bath.

An ideal suspension bath will greatly improve continuous extrusion while preventing the collapse of structures in 3D bioprinting. By providing a hydrophilic, biocompatible environment, the suspension bath prevents dehydration of extruded hydrogels and cells. Therefore, these support media preserve the long-term stability of the large-scale cellular constructs, while maintaining high resolution and cell survival in an aqueous environment.155 Materials including carbopol, alginate microparticles, gelatin slurry, pluronic, and nanoclay have been used to prepare suspension baths for 3D bioprinting.71,89,153,154,156,157 Carbopol suspension is a polyacrylic acid based medium with particle size at the average of 7 μm.153 It exhibits tunable viscoplastic behavior, with higher carbopol concentration producing a larger yield stress. With elaborate adjustment, the carbopol medium allows the precise printing of decellularized ECM (dECM), collagen, and fibrin, which have been proved challenging using the conventional extrusion bioprinting, into structures that resemble natural forms. The feasibility of a suspension bath is further confirmed by creating complex structures such as vascular networks and trileaflet heart valves cellularized with cardiac based bioinks.71,158 Although these structures are a proof of concept, the high printing resolution achieved permits the basic functions of printed tissue such as vascular perfusion and cardiac contractility.159,160 An extraction step to remove a printed structure from the embedment is normally necessary after bioprinting. Depending on the characteristics of suspension media, current methods to extract constructs include elevating the temperature to melt the medium (e.g., gelatin slurry), enzymatic cleavage (e.g., alginate microparticles), and simple washing or dilution (e.g., carbopol and nanoclay). This process may cause physical or chemical state changes to the suspension medium, which may subsequently lead to the deformation of printed bioinks and thus deteriorate the structural integrity. The other limitation of using suspension baths is that the temperature of the printed bioink is dictated by the temperature of the suspension medium. Therefore, it restricts the utilization of some hydrogels with properties (e.g., cross-linking) that rely on temperature.

IV. BIOMECHANICAL PROCESSES POST BIOPRINTING

Biomechanical properties of printed tissue constructs are one of the major parameters involved in post bioprinting steps which determine the structural integrity and stability of tissue constructs. Characterization and precise tuning of these properties are critical for the successful application of bioprints in the ultimate in vitro applications, as modeling and screening platforms, as well as their in vivo applications as implants. The biomechanical properties of printed constructs significantly regulate and stimulate the function of the cells that interact with these scaffolds.88 Thus, investigating the interactions between cells/tissues and printed tissue biomechanics is of great significance (Table I).

A. Post print hydrogel cross-linking

In situ cross-linking during bioprinting can improve the mechanical properties of bioinks, making it possible to successfully create 3D stacked constructs with significantly improved structural integrity and fidelity. However, relying on in situ cross-linking may not provide sufficient mechanical support to maintain the stability of constructs for the following manipulations, such as transferring and shipment, tissue measurements, 3D culture, and implantation. As such, cross-linking post bioprinting is a necessary step to ensure the mechanical stability of hydrogel constructs. Depending on the mechanism, cross-linking after bioprinting can be achieved via a diverse range of physical or chemical modifications.99 Typically, physical cross-linking is based on mechanisms like ionic interaction or thermal polymerization. In ionic cross-linking, the binding in the polymer network is mediated by cationic interactions via charged compounds.161 For instance, Ca2+ ions and other divalent cations have been used to bind to guluronate blocks from natural hydrogels such as alginate.162 The guluronate blocks of one polymer chain form junctions with the adjacent chains, resulting in the solidification of alginate. Temperature mediated cross-linking is a reversible process in which the thermosensitive hydrogels, such as gelatin and collagen, form gels through polymer chain entanglement, hydrogen bridges, or hydrophobic interactions within critical temperature range. These materials can turn into fluid again when the temperature is modified. Unlike physical cross-linking, chemical polymerization normally connects hydrogel chains via covalent bonds, which are strong and relatively permanent compared to those linked via physical bonds. Several cross-linking approaches using chemical linkages have been reported, such as photo-polymerization, enzymatic induced cross-linking, and Schiff based formation.99 Among these, photo-polymerization methods have been attracting increasing attention due to their sufficient cross-linking rate at ambient temperature under mild conditions, and accurate polymerization through the selection of cross-link sites.163 Photo-polymerization is based on the existing unsaturated groups such as the (meth)acrylates in the polymer chain. In the presence of photo-sensitive chemicals, like Irgacure, the bonds between neighboring polymer chains are created under light irradiation.164 Depending on the presented photo-initiator, hydrogel gelation occurs under light at specific wavelengths ranging from 250 to 810 nm.165

Crosslinking significantly improves the mechanical strength of hydrogel bioinks, making it possible to build 3D structures via bioprinting. In addition to the type of hydrogel ink, mechanical properties of printed constructs can be also tailored by altering the cross-linking method. Hydrogels with similar composition can exhibit different mechanical performances based on different cross-linking strategies.166 For instance, collagen is one of the most extensively used hydrogels in 3D bioprinting. It can be solidified via either physical cross-linking, such as pH adjustment, or chemical cross-linking, such as genipin treatment after bioprinting.167 Compared to physical cross-linking, adding chemical reagents will significantly increase the bonds of collagen fibers, thus enhancing the stiffness of the collagen hydrogel.168 Reagents selected for chemical cross-linking must be cytocompatible, otherwise they will lead to considerable cell death and eventually, the failure of the bioprinted tissue constructs. For a given cross-linking strategy, the mechanical properties are also tunable by modifying the cross-linking time and/or the concentration of cross-linking agents.169 During ionic cross-linking, for instance, the mechanical properties of alginate-based constructs heavily rely on the concentration of Ca2+ ions as well as the reacting time between alginate and Ca2+.162 More Ca2+ ions or longer cross-linking times introduce a stiffer alginate substrate, which is expected for maintaining structural stability. But extra Ca2+ ions or long cross-linking times may be toxic to the cells involved, thus adjusting the cross-linking procedure for alginate-based bioinks must consider both printability and biocompatibility.170 A similar trend is also found in chemical cross-linking. For example, gelatin methacryloyl (gelMA) is a UV light-crosslinkable, gelatin-modified hydrogel.93 During photo-polymerization, the intensity and duration of UV light play key roles in tailoring the cross-linking level of gelMA hydrogels—higher UV light intensity and/or longer exposure time results in a stiffer gelMA construct, which is preferred from the printing stability point of view. Meanwhile, exceeded UV exposure (usually more than 10 mW cm−2, or longer than 5 min) may not be tolerable by most of cell types and may introduce severe cell DNA damages.99 As a result, the cross-linking procedure should be precisely tuned considering the trade-off between structural stability and the biocompatibility of the crosslinked hydrogels.

B. Biomechanical properties of printed tissues

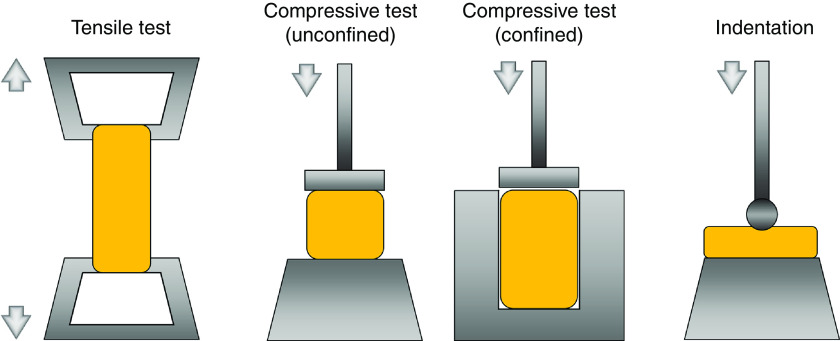

Defining the mechanical properties of bioprinted constructs can be performed following either time-independent or time-dependent assessments.101 This is due to the characteristics of the hydrogel material which can act either in the solid phase, where the mechanical behavior correlates with the time-independent elasticity due to the ability of polymeric structures to recover after load removal, or show viscoelasticity under the exposure of long-term mechanical stimuli.171 Techniques and apparatus that are generally employed for other engineering materials such as plastics are normally adapted for the mechanical characterization of hydrogel-based constructs. The most common tools for characterizing the hydrogels behavior are tensile and compressive tests.100 Experiments conducted based on these approaches normally collect the force-displacement-time data and convert them to stress–strain–time to extract the mechanical properties (Fig. 7).87 Tensile tests have been widely used for evaluations of hydrogel samples in various shapes but those with regular geometries such as cylinders, strips, or rings are preferred.172 A key to the successful execution of tensile tests is sample gripping, which is challenging for most bioprinted constructs due to their poor mechanical strength and complex geometries.173 Like tensile tests, compressive tests record the force and displacement of samples under controlled compression rates, but instead of gripping, compressive tests employ two stiff flatten plates to compress the sample in either a confined or unconfined manner.174 Unlike the tensile test, compression eliminates the need for clamps for hydrogel sample gripping, which significantly simplifies the sample preparation pretesting and improves the testing efficiency. Also, the compressive test is versatile for samples with varying geometries, thus more feasible for evaluations of 3D bioprinted constructs. The reliability of compression results relies on the even distribution of pressures on the sample. The results accuracy can be significantly affected for samples with bulging or sunk surfaces.171

FIG. 7.

Approaches and devices used for biomechanical assessment of printed hydrogel constructs.

Indentation is another technique that has been used to characterize the mechanical properties of hydrogels, where samples are intended to a certain depth by a probe with a known geometry (Fig. 7).100 It is a local/micro scale of the compression test which collects the indentation force-depth-time data for mechanical analysis. Indentation has become a popular mechanical analysis tool due to its advantages for small (micro or nano)-scale assessments, the noninvasive nature of the test (compared to destructive tensile and compression tests), and the diversity of probes with a tunable size and shape for various applications.175 It enables local evaluation of hydrogels for quantification of the inhomogeneity (e.g., due to uneven cross-linking), according to the mapping approach across the entire tested region.176 However, as most of the indentation techniques are developed for traditional engineering materials, they are limited in evaluating samples with strict sterile requirements such as live cellular scaffolds. An alternative approach is atomic force microscopy (AFM), where the testing tip is actuated indirectly via a calibrated cantilever. AFM has been used for hydrogel indentation testing.177 The cantilever systems can estimate different materials by switching the cantilever stiffness; however, this method is highly sensitive to cantilever calibration, making it a non-ideal approach for the analysis of hydrogel-based structures.

Rheometers have been also frequently used for characterizing the viscoelastic properties of hydrogel constructs after bioprinting, as hydrogels exhibit both solid and liquid behavior in a timescale under mechanical loading. Like the bioink evaluation pre bioprinting, a sinusoid shear single with given frequencies can be applied on bioprinted structures to measure the storage and loss moduli, which are used to quantify the viscoelastic behavior of these structures.

The characteristic that is normally used to describe the mechanical state of bioprinted constructs is stiffness, which is defined as the resistance of materials/structures undergoing the deformation when exposed to mechanical loads.102 Stiffness is identified as the slope of the linear region of the load–distance curve, which can be denoted using Young's or elastic modulus, or compressive modulus, depending on whether the tensile or compressive test is employed. A larger elastic/compressive modulus indicates a more rigid material at higher stiffness. During indentation, the most commonly reported parameter to interpret the mechanical properties of a hydrogel is the reduced modulus, which has been used to evaluate material stiffness.178 Since hydrogels exhibit viscoelastic behavior, which significantly replaces the elastic constants over time under loading, approaches that describe such dynamic properties of hydrogels have attracted increasing attention. Besides oscillatory shearing using a rheometer, stress relaxation experiments have been conducted for this purpose, by stretching or compressing the sample at a predetermined strain within a certain period.101 Results from both methods can determine the mechanical properties of hydrogels, such as shear modulus, Poisson's ratio, and their poroelastic behavior.179 Tensile, compressive, or indentation test can be employed for the evaluation of stress relaxation. Tensile and compression methods generate results that reflect the entire structural property of the bioprinted sample, while indentation techniques shed light on the local, micro/nano-scale mechanical properties of the constructs.