Abstract

Esophageal cancers, largely adenocarcinoma in Western countries and squamous cell cancer in Asia, present a significant burden of disease and remain one of the most lethal of cancers. Key to improving survival is the development and adoption of new imaging modalities to identify early neoplastic lesions, which may be small, multifocal, subsurface, and difficult to detect by standard endoscopy. Such advanced imaging is particularly relevant with the emergence of ablative techniques that often require multiple endoscopic sessions and may be complicated by bleeding, pain, strictures, and recurrences. Assessing the specific location, depth of involvement, and features correlated with neoplastic progression or incomplete treatment may optimize treatments. While not comprehensive of all endoscopic imaging modalities, we review here some of the recent advances in endoscopic luminal imaging, particularly with surface contrast enhancement using virtual chromoendoscopy, highly magnified subsurface imaging with confocal endomicroscopy, optical coherence tomography, elastic scattering spectroscopy, angle-resolved low coherence interferometry, and light scattering spectroscopy. While there is no single ideal imaging modality, various multimodal instruments are also being investigated. The future of combining computer-aided assessments, molecular markers, and improved imaging technologies to help localize and ablate early neoplastic lesions shed hope for improved disease outcome.

Keywords: narrowband imaging, confocal laser endomicroscopy, optical coherence tomography, computer-aided diagnosis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal cancer

Clinical role of advanced esophageal endoscopic imaging for cancers

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer in the world, with an estimated incidence of 456,000 cases and 400,000 deaths in 2012,1 and includes esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). In the West, the incidence of EAC is one of the fastest rising of any cancers with an approximately 6-fold increase in the last 40 years and has been attributed to the rise in risk factors for developing Barrett’s esophagus (BE), particularly of gastroesophageal reflux disorder, central obesity, and increasing age. BE is the histological presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells in the distal esophagus. It is widely believed that BE is a premalignant condition in that it is a risk factor for the development of EAC. This is believed to occur along a sequential continuum from low-grade dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia to intramucosal carcinoma. EAC continues to have a poor prognosis with mortality rates nearly equal to incidence rates, and nearly half of patients diagnosed are limited in treatment options other than palliative care. Endoscopically, dysplasia is often indistinguishable from nondysplastic BE mucosa, occurring in a multifocal, random spatial distribution. Thus, BE surveillance entails random 4-quadrant and additional targeted biopsies for suspicious lesions, per the Seattle protocol.2

ESCC is still the most prevalent form of esophageal cancer in the rest of the world. Its incidence varies depending on geographic localization with the highest rates found in Northern Iran, Central Asia, and North-Central China, also known as the “esophageal cancer belt,” where 90% of cases are ESCC with approximately 100 cases per 100.00 person-years.3 Although major risk factors for ESCC in high-risk areas are not well understood, alcohol consumption, cigarettes, poor nutritional status, diet high in nitrogenous components and low in fruits and vegetables, and drinking beverages at high temperatures are thought to play a role.4

These esophageal cancers have a poor prognosis because they rarely cause symptoms at early stages and, therefore, are diagnosed late in their course. For example, superficial ESCC, where the tumor is limited to the mucosa (T1a), is usually asymptomatic and treatment at this stage is associated with a higher 5-year survival rate of up to 80%. Conversely, patients with advanced ESCC (i.e., tumor spread into the submucosal layer, T1b–T4) are usually symptomatic on presentation and carry a poor 5-year survival rate of 55%.5 While these argue for early detection, the multifocal nature and subtle mucosal signs related to early neoplastic changes in the esophagus make this challenging.

The current gold standard for diagnosis of early esophageal cancers is based on standard endoscopy to procure samples for histopathology. However, this approach can be laborious, time-intensive, costly, and fraught with sampling errors. For example, random biopsies endoscopically obtained by the current Seattle protocol for BE surveillance represent less than 1/40 of the involved surface, a large proportion of biopsies are not adequately deep, and often pathologists examine only a small section from each specimen. This is of particular concern since early dysplastic lesions can be focal, multiple, and scattered, and have relatively preserved surface tissue architecture for which deeper sampling would be required. Notwithstanding, there is poor adherence (<35%) to such biopsy protocols by community endoscopists6 and poorer dysplasia detection rates compared with expert endoscopists7, although in part explainable by referral bias for the latter.8 There is also poor concordance in distinguishing BE dysplasias among pathologists.9 Several endoscopic surface imaging tools may aid to localize areas of early neoplasia, such as chromoendoscopy (CE), virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE) through optical and digital enhancements, endoscopic microscopy, and autofluorescence endoscopy.10 Use of agents to enhance surface contrast (commonly Lugol exclusion for squamous cell cancers and acetic acid or methylene blue for BE) adds time to procedure, varies greatly in accuracy owing to different techniques and dyes, and has poor specificity particularly with poor spraying and gastric-type or denuded areas of the epithelium.11 While Lugol exclusion has sensitivity and specificity that range from 96−100% and 5−64% in detecting early ESCC, respectively, this approach is not without its complications, which include iodine hypersensitivity, laryngitis, pneumonitis, chest discomfort, and nausea.5 Recently, super-magnifying endoscopes (e.g., from 380×, 450×, and 600×) have allowed in vivo endocytoscopy (ECS, Olympus) in Japan.12, 13 While providing remarkable cellular and nuclear detail, it is restricted by its small field of view and narrow-focusing depth of approximately 50 micrometers. Moreover, endocytoscopy has low sensitivity, requires endoscopy to confirm a diagnosis and obtain biopsies, and is not cost-effective compared with standard endoscopy.5,6 There are also new methods for procuring samples from the broad lumenal surface of the esophagus, such as by cytology brush during endoscopy for the wide-area transepithelial sample with three-dimensional computer-assisted analysis (WATS, CDx Diagnostics) as an adjunct to standard forceps biopsies to improve detection of BE and dysplasia14,15. Besides such computer-aided diagnostic assays, new tissue acquisition methods are also being paired with new biomarkers. For example, the Cytosponge™ (Medtronic) involves a tethered encapsulated sponge to collect cells nonendoscopically, and has been evaluated in several clinical trials with the biomarker trefoil factor 3 (TFF3; aka intestinal trefoil factor (ITF))16, 17 or for microRNAs.18 The inflatable balloon EsoCheck™ (Lucid Diagnostics) is a comparable office-based device but not requiring capsule dissolution and with possibly easier retrieval for the patient. Collected cells have been analyzed for two high-frequency cytosine DNA methylation, which is demonstrated to yield over 90% sensitivity and specificity for detecting BE.19 Such obtained tissues may also be analyzed by other methylation markers20 and other biomarkers, such as the multiplexed TissueCypher™ (Cernostics)21 and automated infrared spectroscopy,22 not only for detecting Barrett’s but also for detecting neoplasias or identifying patients at an increased risk of progression to dysplasia.23

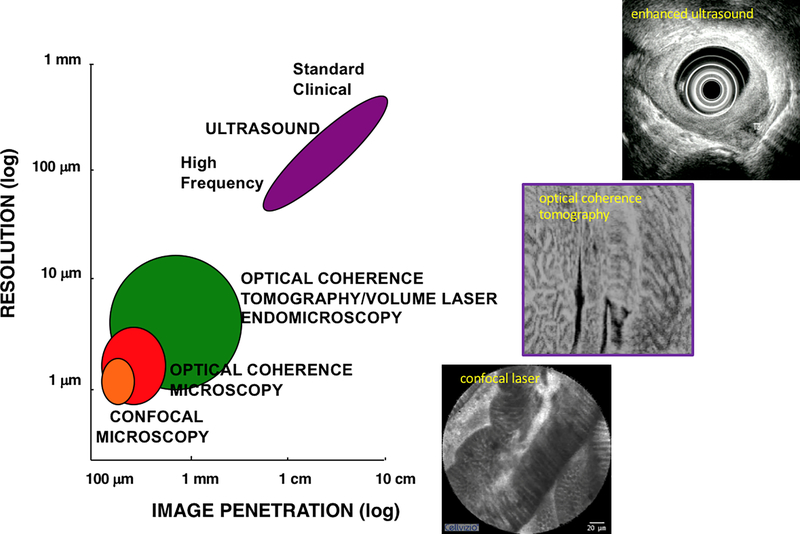

Subsurface structures, such as buried BE glands and neoplasia under the neosquamous epithelium that forms after ablation, may be readily missed by surface imaging and by the commonly inadequate depth of biopsies.24 Thus, complementary subsurface imaging modalities (Fig. 2) may greatly enhance detection and target treatment of early neoplasias. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has the depth and broad field to allow staging of tumors and has been the choice imaging modality, particularly concerning its sensitivity of N and T staging, despite advances in computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).25 However, EUS has limited use in assessing the depth of dysplasia and early cancers and lacks the lateral resolution to define their precise borders during endoscopic resection, particularly when poorly visible under white light endoscopy (WLE).26 Overall, EUS is inadequate to determine which T1/T2 tumors are candidates for endoscopic therapy27 and is fraught with both falsely over- and understaging.28 As such, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) has become increasingly a safe first-line treatment for BE with dysplasia and intramucosal EAC, particularly at BE referral centers,29 and possibly usurps the role of EUS.30 Future advances in BE and neoplasia detection may also apply biomarkers to standard imaging techniques, such as CT, MRI, and PET.31,32

Figure 2.

Endoscopic subsurface imaging tools comparing ultrasonography, OCT/OCM, and confocal microscopy in terms of resolution at the cost of image depth penetration.

VCE

Virtual or electronic chromoendoscopy involves optical and digital enhancements now available on many endoscopes to accentuate surface mucosal patterns and vascular features without the use of stains or dyes.33 Narrowband imaging (NBI) is a high-resolution endoscopic imaging technique that uses narrowband filters to enhance not only the mucosal layer but also its vasculature, which may be disorganized in dysplastic and neoplastic lesions.34−36 NBI is based upon the fact that the depth of light penetration into the mucosa depends upon its wavelength: the longer the wavelength, the deeper the penetration. Standard WLE consists of three light waves: blue, green, and red. NBI, currently available on the Olympus endoscopes, utilizes a filter to increase the contribution of blue light with its shorter wavelength that penetrates only superficially resulting in a characteristic image that accentuates and enhances the mucosal surface and superficial vasculature. Superficial blood vessels with high hemoglobin (Hb) concentration absorb blue light and appear brown and contrast with the brighter surrounding mucosa, whereas deeper vessels absorb green light and appear cyan (pale blue color). The quality of the superficial pit pattern morphology is also clearly enhanced by this technology. A regular mucosal pattern would be typical in nondysplastic BE in contrast to an irregular and distorted mucosal pattern in high-grade dysplasia and early esophageal cancer (Fig. 1). NBI can also be combined with optical and digital magnification endoscopy to further enhance the imaging.36

Figure 1.

Examples of NBI in the esophagus. The upper panel shows nondysplastic BE under WLE on the left and corresponding NBI image on the right. The lower panel shows dysplasia in BE under WLE on left and enhanced irregular mucosal pattern under NBI on the right.

NBI has several advantages over CE. No staining agents are required for NBI and it is easy to use with a 1-s on-off switch on the endoscope handle between WLE and NBI. Additionally, NBI allows for uniform inspection of the entire endoscopic field while in CE, the dye is often not distributed evenly. Furthermore, NBI reveals the superficial vasculature in high contrast whereas the vascular pattern is often less visible on CE.

The effectiveness of NBI for the detection of dysplasia in BE is not well established. In a prospective tandem study of NBI compared with standard WLE, NBI detected significantly more patients with higher grades of dysplasia (57% versus 43%) with 50% fewer biopsy samples.37 A meta-analysis that included 446 patients from eight studies showed that NBI with magnification endoscopy has high diagnostic precision in detecting HGD with sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 94% respectively.38 NBI has also been shown comparable with indigo carmine39 and other chromoendoscopies40 as adjuncts to high-resolution endoscopy for detecting neoplasias. Although promising, these studies were performed by experts in single centers. Moreover, other studies have shown poor interobserver agreement for enhanced imaging methods for detecting early neoplasia in BE.41−44 The Barrett’s International NBI Group (BING), composed of NBI experts from the United States, Europe, and Japan, developed a simple, internally validated system to identify dysplasia and early esophageal cancer in patients with BE based on NBI results. The BING criteria identified patients with dysplasia with 85% overall accuracy, 80% sensitivity, 88% specificity, 81% positive predictive value, and 88% negative predictive value. When dysplasia was identified with a high level of confidence, these values were 92%, 91%, 93%, 89%, and 95%, respectively. The overall strength of the inter-observer agreement was substantial (k = 0.681).45 Nogales et al., used BING classification and nonmagnifying NBI in their study to diagnose dysplasia in BE for targeted biopsies and concluded that the result had significant accuracy with high specificity (>90%) and negative predictive value (>85%).46

NBI can also be used to identify early squamous cell cancer with its characteristic intrapapillary capillary loop (IPCL) patterns. High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and carcinoma have irregular IPCL patterns (i.e., dilatation, tortuosity, caliber change, and variation in shape). Thick bluish/ green vessels on NBI are indicative of submucosal invasion.47

Other VCE systems include I-scan (Pentax) and flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (FICE, Fujinon), which utilize postprocessing imaging techniques that use images obtained in standard WLE to accentuate specific areas by wavelength.48 Blue laser imaging (BLI, Fujinon) has been developed to overcome some of the limitations in NBI and FICE by combining narrowband laser light with high-definition WLE resulting in bright, high-resolution images of microvasculature and microstructures of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.49

VCE remains problematic as not all endoscopists will have proficient skills in diagnosis using these techniques. The development of artificial intelligence (AI) may offer a solution. In recent years, image recognition using innovative technologies such as machine learning and deep learning can become a powerful supportive tool that can interpret medical images based on an accumulated set of unique algorithms. In regards to endoscopic diagnosis, the development of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems using AI is progressing. Horie et al. developed deep learning through a convolutional neural network (CNN) for the detection of esophageal cancer by constructing an AI-based diagnostic system that was trained using a large number of EGD images using both WLE and NBI. The CNN took 27 s to analyze 1118 test images and correctly detected esophageal cancer cases with a sensitivity of 98% and a negative predictive value of 95%. Moreover, the CNN could distinguish superficial esophageal cancer from advanced cancer with an accuracy of 98%.50 An AI diagnostic system of CNNs using deep learning techniques was able to detect 95.5% of ESCCs and correctly estimated the invasion depth with a sensitivity of 84.1% and an accuracy of 80.9%.51 The benefits of AI-assisted image analysis have also been demonstrated in the stomach and colon. A CNN system pretrained with magnified NBI images can differentiate between early gastric cancer and gastritis with high sensitivity (95.4%) and negative predictive value (91.7%).52 In predicting endoscopic curative resection of large colonic polyps (≥2 cm), an AI image classifier trained by 8,000 images had an overall accuracy of 85.5%. Images from NBI had significantly higher accuracy than images from WLE.53

In conclusion, VCE is a promising imaging modality for the detection and detailed evaluation of early mucosal neoplasia in the upper GI tract. NBI is user friendly, requires no special dyes, and allows for inspection of the superficial vascular bed that may not be possible with CE. Although readily available, the classification of mucosal and vascular patterns with NBI is not well standardized or validated and requires expertise. AI image recognition is developing rapidly and is expected to help endoscopists improve the detection and characterization of early mucosal neoplasia.

Confocal laser endomicroscopy

Unlike CE and VCE that are restricted to the analysis of the mucosal surface, confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE) provides both surface and subsurface images, albeit limited in depth (Fig. 2). Confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), first described in vivo in 2004 in the context of diagnosing intraepithelial and colorectal cancer,54 has evolved into a powerful diagnostic tool for metaplastic and dysplastic changes of the esophagus. While the details of confocal microscopy are beyond the scope of this review, at its most basic, CLE represents an optical imaging technique that uses low-power laser light to focus on a single point within the tissue. Light reflected from this point is focused through a pinhole to a detector, and reflection from other tissue points are blocked, effectively eliminating scatter. The tissue is imaged in a stepwise fashion from the surface to deeper structures without physical disruption.55 There are currently two systems available for with the endoscope, both of which deliver a low-energy excitation wavelength of 488 nm, with a collection bandwidth of 505–585 nanometers.56 The endoscopic integrated system (eCLE; Pentax EC-3870CIFK®, Tokyo, Japan) uses a miniaturized laser-scanner integrated into the distal tip of a conventional endoscope. A single optical fiber serves as a pinhole and the imaging plane depth can be adjusted from the surface to 250 micrometers. Serial optical sections with a resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels are obtained parallel to the tissue surface within 475 × 475 μm field of view (FOV). The advantages of this system include generating simultaneous endoscopic and confocal images, capturing images at different depths from 0 to 250 μm, and leaving the working channel available for use. Despite the improved depth, magnification, and clarity of a CLE dedicated Pentax CLE system, this is no longer available. However, CLE continues to be available as a flexible mini-probe pCLE® (CellVizio™ MaunaKea Technologies, Paris, France), which can be introduced through the accessory channel of standard endoscopes and offers impressive near-microscopic images. In pCLE, the imaging plane is fixed and the lateral resolution is defined by the number of fibers (30,000 pixels). However, image acquisition is fast enough to provide a microscopic video of the mucosa. Probes are available at a different field of views and diameters ranging from 0.3 to 4.2 millimeters. pCLE focusing depth is approximately 150 μm, which is deeper than that of endocytomicroscopy. Regardless of the system employed, CLE, as with endocytomicroscopy, covers only a small mucosal area and panendoscopy is not feasible. Areas of interest must first be identified by WLE or CE, followed by CLE to target those areas.

The first use of CLE in BE was reported by Kiesslich in 2006.57 On the basis of 63 patients, vessels and cellular architecture by eCLE were correlated to the pathology of coregistered targeted biopsies. These images were used to establish the Mainz confocal criteria for Barrett’s classification. Compared with the squamous esophagus, nondysplastic BE reveals tubular and villiform structures with regular epithelial width and goblet cells, reminiscent of the small intestine. Neoplastic BE reveals loss of normal architecture with varying epithelial width, dark cells, and leakage of fluorescein from microvessels. At least in the hands of expert operators, but offline, the Mainz criteria demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 94%, respectively, for distinguishing BE from the squamous or gastric epithelium and 93%, and 98% for identifying neoplasia within BE with a high interobserver agreement, κ = 0.843. Subsequently, criteria emerged for pCLE based on five architectural features identified for neoplastic BE: irregular epithelium, variable epithelial width, gland fusion, dark areas, and irregular vessels (for example, see Fig. 3). These features formulated the Miami consensus classification for distinguishing normal squamous, BE with and without dysplasia, and intramucosal carcinoma.58 Several studies report high accuracy using CLE for the detection of Barrett’s neoplasia (BN). One study examined probe-based CLE in a multicenter prospective double-blind tandem endoscopy trial involving 101 subjects referred for surveillance or therapy of BE. The esophageal mucosa was first examined by WLE and NBI, then supplemented with CLE with the primary endpoint of detecting high-grade dysplasia and/or early cancer. The use of probe-based CLE beyond WLE or NBI inspection was 100% sensitive resulting in the detection of all patients with HGD/IMC in this referral cohort with an enriched 30% prevalence. Adding CLE to combined modality WLE/NBI imaging yielded a negative predictive value of 100% and thus would have spared biopsies in 39% of patients who did not harbor HGD/IMC at all. However, the addition of CLE helped find only two additional patients with dysplasia over WLE and 1 patient beyond NBI.59 Similarly, a tertiary referral single-center study suggested that CLE did not add much diagnostic value over high-definition and NBI endoscopy, but made an argument for targeted biopsies without need for random biopsies, at least in detecting HGD and IMC.60 By contrast, another single-center study demonstrated increased incident dysplasia detection with 100% sensitivity, 83% specificity when compared with high-definition WLE endoscopy alone.61 An international multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial examined the use of endoscope-based CLE on 192 patients. The study compared the use of while light endoscopy with random Seattle protocol biopsy compared with CLE-targeted biopsies for the real-time detection of BN in a referral cohort. The use of CLE-targeted biopsies decreased the number of biopsies 4.8-fold over random biopsy. Also, the per-biopsy diagnostic yield increased from 7% to 34%, and the per-patient yield from 6% to 22%. The use of CLE increased the sensitivity for BN from 40% to 95% and biopsies could have been obviated in 65% of subjects altogether without missing any BN. The treatment plan was changed using CLE in 36% of cases. 62 A meta-analysis pooling five studies compared with NBI revealed that pooled sensitivity for detecting HGD/EAC in patients with BE was similar, but CLE significantly increased the per-lesion detection rate of HGD/EAC.63 A retrospective study to further refine the pCLE criteria for identifying neoplastic lesions in BE was performed by Gaddam et al. and continued to show good overall accuracy of 81.5%, with a high interobserver agreement of κ = 0.61. 64 Thus, in trained hands, CLE improves the diagnostic yield of dysplasia surveillance in BE and influences therapeutic decision making in real-time in a substantial number of cases. A systematic review and meta-analysis by the ASGE Technology Committee concluded that in expert hands, endoscope-based CLE, along with acetic acid and NBI targeted biopsies, met the performance thresholds of The Imaging in Barrett’s Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) statement and therefore enabling the elimination of random biopsies as an adoptable standard of care. 65

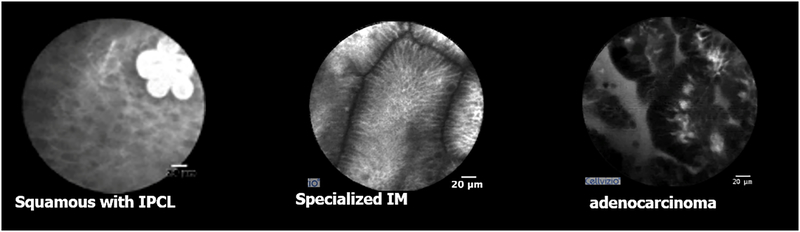

Figure 3.

Examples of CLE images in the human esophagus using intravenous fluorescein contrast. (A) The normal squamous epithelium with intrapapillary capillary loops (IPCL). (B) Specialized intestinal metaplasia (BE). (C) Esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Compared with standard endoscopy, CLE can increase the detection of dysplasia.59, 66 At least in expert centers, CLE used together with high-definition WLE was demonstrated to have sufficient sensitivity and specificity for detecting dysplasia62 to obviate the need for excisional pathology confirmation in accord with the Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) thresholds recommended by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.65 However, rates of detection may differ with various users and institutions, even when used in conjunction with NBI, and may reflect issues of concordance of readings and degree of referral bias that affects pretest probability.67

To visualize structures using CLE, three contrast agents are available. Fluorescein sodium is administered intravenously and binds serum albumin. Unbound contrast diffuses across capillaries, enters the tissue, and stains the extracellular matrix of the surface epithelium and lamina propria for up to 30 minutes. Cell nuclei and mucin are not stained and therefore appear dark. Acriflavine hydrochloride (0.05%) or cresyl violet (0.2%) is topically applied and labels the acidic constituents, staining the nuclei of superficial layers of mucosa. However, these intravenous contrast agents may extravasate and quickly obscure areas of endoscopic biopsies and resections. However, pCLE has a distinct advantage of detecting available enhancing fluorescent markers and is conducive to molecular imaging to localize areas of early neoplasia in the near future, particularly by targeting moieties like enzyme-activatable probes, lectins and small molecules for endoluminal imaging.68−70

With regards to ESCC, Pech et al.71 evaluated whether CLE could accurately diagnose patients with early ESCC referred for endoscopy. Lugol’s CE was utilized and unstained areas were targeted by CLE and recorded as neoplastic or normal. Subsequent biopsy specimens were reviewed and compared with the CLE images. Confocal images were acquired from 43 lesions in 21 patients. CLE characteristics of presumed ESCC included irregular cell shape and borders, irregular elongated capillaries, and capillary leak. Twenty-seven of the 43 lesions (63%) were proven to be squamous cell cancer on histology. All ESCC were diagnosed correctly by CLE and two lesions were falsely diagnosed as neoplastic. The overall accuracy during ongoing endoscopy was 95%, with an 89% accuracy of the blinded assessment. Sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 87%, respectively.

Concomitant to this study, Liu et al. 72 conducted a prospective study, the aim of which was to compare the endomicroscopic characteristics of esophageal mucosal cells and capillaries in patients with and without ESCC.72 Patients with early endoscopic-confirmed SCC and asymptomatic controls were consecutively recruited to create and test a CLE classification system. On the basis of correlation with histology, irregularly arranged cells and altered IPCL patterns were identified (for example, see Fig. 3) and four criteria were used to discriminate cancerous versus normal tissue, including (1) the presence or absence of irregularly arranged squamous epithelial cells, (2) the vessel diameter of the largest IPCL in every selected image, (3) the number of IPCLs per image, and (4) the presence or absence of irregularly shaped IPCLs (i.e., tortuous, branching, and spiral). The classification system was tested by two blinded reviewers evaluating the CLE images of 64 samples, from 57 subjects (27 ESCCs and 30 controls), and comparing them with corresponding hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained samples from the same sites. CLE images demonstrated a significantly higher proportion of squamous epithelial cells with the irregular arrangement (79.4% versus 10.0%, P < 0.001), increased diameter of IPCLs (26.0m versus 19.2m, P < 0.001), and irregular shaped IPCLs (82.4% versus 36.7%, P = 0.0002) in the ESCC group compared with controls. Additionally, large IPCLs with tortuous vessels (44.1% versus 0%, P < 0.0001), and long branching IPCLs (23.5% versus 3.3%, P = 0.0204) were more prevalent in the ESCC group. Autofluorescence imaging could also be used in conjunction with pCLE for targeting biopsies to improve the detection of dysplasias and intramucosal carcinomas with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 53.6% in the setting of BE, similar to NBI with magnification.73

Taken together, these studies suggested that normal and neoplastic squamous epithelium of the esophagus could be reliably differentiated using CLE, underscoring its potential in early detection of ESCC that, in turn, would enable timely therapy. However, success with CLE requires training on the technical aspects of targeting the probe to the region of interest, acquiring a thorough knowledge of mucosal histopathology, and collaboration with pathologists.

Optical coherence tomography

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a back-scatter imaging technology similar to ultrasonography but uses light instead of sound to achieve a magnitude higher resolution. Unlike confocal endomicroscopy, this does not require intravenous contrast agents. OCT allows approximately 3-mm depth, broad-field, near-microscopic (3−5 μm axial resolution), real-time images (Fig. 2). Two commercial systems are the Nvision VLE™ (NinePoint Medical, Bedford, MA) and LuminScan™ (Micro-Tech, Nanjing, CN), both of which use balloon-based catheters with proximal actuation of the fiberoptic cable and distal scanning mirror. These OCT systems presently lack the degree of lateral resolution to reveal cellular detail of CLE images but can reveal tissue architecture with subsurface details including mucosal glands and ducts that cannot be appreciated on CLE.74 Both OCT systems allow laser marking for guiding biopsies or treatments at imaged focal areas of interest. Several studies have defined image features and algorithms to optimize detection of dysplasia,75, 76 which are easy to adopt with a reasonable learning curve,77 a good interobserver agreement,78 and an incremental yield of dysplasia detection compared with random biopsies.79 A multicenter registry of 1000 patients using VLE showed a 7-fold increase in neoplasia detection and improvement in the BE management process.80 That said, such studies taken together presently do not show sufficient diagnostic accuracy to meet recommended PIVI thresholds.81 However, a multicenter study is currently correlating VLE images with more accurately obtained tissue histology, aided by an integrated laser-marking system, and will help define OCT features and scoring for possible CAD in the near future.

Besides the detection of neoplasia, OCT may also have unique roles before, during, and after ablative therapies. The ability of OCT to assess and map the thickness of BE may help define which ablative method to use or vary the amount of ablation over particular regions since BE depth varies greatly even within the same patient.82 As such, OCT was able to demonstrate that cryoablation may reach a deeper depth of tissue destruction compared with radiofrequency ablation83. The ability to monitor ablation in real time during RFA energy delivery may also help finetune dosimetry relative to BE depth and gland parameters.84

OCT also has a role in postablative imaging and can reveal residual BE glands85 that are predictive of postablative outcomes for achieving complete eradication of all intestinal metaplasias (CE-IM).86 While the neoplastic implications of glands buried under subsequent neosquamous epithelium remain unclear,87 such structures are prevalent near the gastroesophageal junction and gastric cardia after ablation,85 and may help identify neoplasias. 88 While conventional balloon-based OCT catheters may not adequately image the cardia, forward-viewing probes that can be retroflexed during endoscopy hold promise.89 Another advance that has become available through faster acquisition and processing is the ability to enhance images by analyzing doppler-like frame-to-frame changes created by coursing red blood cells to define microangiopathic changes,90 which with further improvements91 appear to correlate with early dysplastic changes.92 This has been applied to assess in real time the margins of mucosal resections, for example.93

OCT may also be uniquely suited for screening and surveillance of early ESCC given the large area, including the entire esophagus that can be imaged within seconds. Using a high-resolution OCT, one Hatta et al. demonstrated that in a small number of 123 consecutive patients, preoperative staging was more useful than a 20-MHz endoscopic ultrasound.94 In a retrospective multicenter study, the commercially available VLE system was used to assess whether OCT can determine whether a superficial ESCC is limited to the lamina propria and can undergo endoscopic therapy.95 This awaits prospective study confirmation with much anticipation.

The integration of computer-aided assessment, augmented reality, and diagnosis will be important for advanced imaging. Computer algorithms can be used on ultra-high-resolution OCT to map not only BE depth for optimal ablation but also to identify subsurface gland-like structures 19,96 The commercial VLE system has adapted an image enhancement system with a color-graded scale (intelligent real-time image segmentation (IRIS)) to highlight layering, lack of surface hyperreflectivity, and epithelial glands (Fig. 4). Laser-marked biopsies with histological correlates confirmed earlier feature algorithms and demonstrated that neoplastic lesions show surface hyperreflectivity (96%), epithelial glands (67%), and lack of layering (96%).97

Figure 4.

Volumetric laser endomicroscopy (VLE) with three views. (A) Looking down from the proximal esophagus. (B) Looking closer to the suspected area of dysplasia. (C) The en face view of the distal esophagus. The luminal en face view shows an area of overlap (yellow arrow) between the three features of dysplasia: orange is a lack of layering, blue is glandular structures, and pink is a hyperreflective surface. Figure and caption were adapted from Trindade et al. 135 and represent the current VLE NinePoint imaging software called Intelligent Real-time Image Segmentation (IRIS)™ artificial intelligence platform.

Several noteworthy advances in OCT technology have yet to be fully incorporated into the OCT commercial systems. The addition of a lens for further magnification can create optical coherence microscopy (OCM), which enhances lateral resolution enabling cellular resolution on par with endocytomicroscopy, but generally at the cost of limited depth, field of view, and focal plane.98 Presentation of images not as mere cross-sections, but with en face views and Doppler-like images to enhance microvasculature may also improve the detection of abnormalities.92,99 Newer microscanning modes have also greatly improved the quality of images and could be applied to other imaging modalities such as CLE in the future.100 Moreover, a dual-axis OCT has been described for deep tissue imaging in ex vivo specimen and await application in the human esophagus.101

Esophageal capsule endoscopy has been introduced as a noninvasive and possibly cost-effective way to detect BE, but it would have limited utility in detecting nearly neoplasias.102 Tethered capsule endomicroscope that uses OCT to provide cross-sectional architectural images of the esophageal mucosa was recently shown to allow identification of BE and dysplasia103 and would allow rapid, cost-effective, nonendoscopic office-based evaluation for screening, surveillance, and postablation follow-up evaluation of the entire esophagus for both BE and ESCC.104,105 This may allow simple and better screening and surveillance by primary care providers even in rural or remote regions since the inherent digital images are conducive to telemedicine or immediate CAD in the future. While its accuracy remains unproven, similar OCT capsules are anticipated to be commercialized soon.

Elastic scattering spectroscopy and AI/machine learning automated classification

Elastic scattering spectroscopy (ESS) is a point-spectroscopic measurement taken over a broad wavelength range (320−900 nm). ESS is not an imaging modality per se, but one that samples a tissue volume of ≤0.05 millimeters. ESS probes are passed via the accessory channel of an endoscope and placed in optical contact with the tissue under examination using separate illuminating and collecting fibers. When performed with specific fiberoptic geometries, ESS is sensitive to the absorption spectra of major chromophores (e.g. oxy-/deoxyhemoglobin) and, more importantly, reports micromorphological features of dysplasia from superficial tissues. ESS spectra derive from the wavelength-dependent optical scattering efficiency (and the effects of changes in the scattering phase function) caused by optical index gradients created by cellular and subcellular structures. Unlike Raman and fluorescence spectroscopies, ESS provides largely structural, not biochemical information. Thus, ESS is sensitive to features such as nuclear size, crowding, chromaticity, chromatin granularity, and mitochondrial and organellar size, and density. 106−108 Because abnormal tissues are often associated with changes in subcellular, nuclear, and organellar features, scattering signatures represent the spectroscopic equivalent of a histopathological interpretation. However, the ESS method senses those morphologic changes in a semiquantitative manner, without actually imaging the microscopic structure.109,110 Typically, ESS clinical studies have leveraged machine learning and artificial intelligence to interpret ESS measurements as meaningful pathologies,111−118 with studies showing the viability of ESS for classification of pathologies related to BE.119−121

In an IRB-approved study at the VA Boston, a cohort of patients undergoing BE surveillance endoscopy was supplemented with ESS. Patients received standard treatment, i.e., routine endoscopy with random multiple physical biopsies using a predetermined geometric pattern as indicated for their care. Before the standard physical biopsy, an optical measurement was taken with the ESS fiberoptic probe that was integrated between the jaws of optical biopsy forceps, permitting near-perfect coregistration between spectroscopic measurements and tissue sampling, while being minimally disruptive to the clinical flow. Spectral measurements were correlated to the consensus classification of the physical biopsies by H&E staining as determined by three GI pathologists. A total of 379 ESS spectra from 46 patients were analyzed: 209 spectra from Barrett’s metaplasia (BM), 32 from Barrett’s neoplasia (BN), which includes low- and high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, 46 from the normal squamous epithelium (NS), and 92 from the gastric columnar epithelium (GE) (Fig. 5). Classification was performed by a diagnostic model based on linear support vector machines, with retrospective leave-one-out cross-validation used to obtain performance estimates. The model yielded an accuracy of 91% for distinguishing GE from NS, 84% for distinguishing BM from NS, and of 85% when distinguishing BM from GE. In the case of differentiating BM from BM, the system achieved a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 75% (Fig. 5). These results hold promise for further performance improvements with additional data and further training of the machine learning algorithms employed.122

Figure 5.

Elastic scattering spectroscopy for detection of the esophageal neoplasm. (A) The receiver−operator curve for sensitivity and specificity in a single-center prospective study. (B) A spectral display of various tissue types in the human esophagus. 122

Multimodal imaging with OCT

OCT and other imaging modalities are being combined to potentially increase their clinical utility. Higher magnification technologies inherently limit the depth of imaging owing to scattered light in tissues and decrease the field of view. Nonetheless, OCT has been combined with fluorescence imaging and ultrasonography for intravascular assessment of early-stage atherosclerotic plaques.123 Because PAT is based on differences in optical absorption of laser-induced acoustic waves, high-resolution ultrasonic images can be obtained from deeper tissues. PAT may also be exploited to measure subtle changes in hemodynamic functions including oxygen saturation and Hb concentration124 that, in turn, may present new ways of exploring neoplastic lesions. While OCT is unable to detect fluorescent probes for molecular imaging, other reporter tags such as nanoparticles and microbubbles are being explored. Meanwhile, a combination of OCT with fluorescence laminar optical tomography (FLOT) has been explored for correlating OCT images with fluorescent molecular markers125 and are promising methods to study tumor angiogenesis, vasculature, and anatomic structural changes to apply for esophageal cancers in the future.126

Other endoscopic imaging modalities on the horizon

There are a number of other promising imaging modalities that go beyond WLE by leveraging potential distinctive characteristics of BE and neoplastic tissues. These are presently unavailable commercially and remain largely investigational tools at few academic centers, and are reviewed elsewhere. 127−129 We mention here a few other modalities that are based on light back-scattering analyses. Angle-resolved low coherence interferometry (aLCI) is another probe-based, depth-resolved, label-free, point-scanning imaging modality that can be introduced through the accessory channel of a standard endoscope to assess for aberrant cell nuclear size and density (nuclear crowding) as a feature of neoplasia.130 It combines the ability of depth resolution of low-coherence modalities like OCT with the ability to assess the light-scattering properties of aberrant nuclei like ESS. This has been applied to ex vivo BE specimen, 131 and optimized algorithm scanning at depths of 200−300 μm below the surface (i.e., beyond the reach of pCLE) attained a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 84% in a pilot study involving 46 patients.132 Similarly, light-scattering spectroscopy 133 and its next-generation polarizing scanning spectroscopy (PSS)134 also have been applied for the detection of neoplasias in the esophagus. The polarization subtraction of the latter negates the contribution of deeper tissues, and assesses the superficial epithelial layer. As with OCT, PSS also has been engineered to rapidly scan broadly over the esophageal surface allowing for potentially better mapping of neoplastic lesions in the future compared with earlier point-scanning probes covering approximately 1 mm2 of tissue at a time.

Conclusion

Besides new medical treatments, future advances in the management and prognosis from early esophageal cancers will depend on early detection by improved screening programs and better imaging modalities to help detect and stratify patients for optimal treatment. As optical biopsies are validated through histological comparison, these imaging modalities may eventually allow immediate diagnosis and therapy of neoplastic changes during ongoing endoscopy without the need for biopsies and delayed pathological confirmation. Clearly, no single imaging modality can address all issues for improved detection, staging, ablation, and follow-up of patients with early neoplastic lesions in the esophagus. But new advances of these novel imaging tools, including the introduction of more cost-effective, rapid, nonendoscopic swallowable capsules, and the potential for multimodal imaging, hold great promise in the detection and treatment of early esophageal cancers.

Presently, success with these advanced tools requires training on the technical aspects of their use and recognition of their imaged features correlating to mucosal histopathology. The future is on the horizon to supplement or replace these requirements with computer-aided recognition, diagnostic, and ablative tools. Besides the augmented reality of the conventional endoscopic images in real time for accentuating neoplastic lesions, depth-resolved ultrastructural data may be used to direct focal ablation or allow computer-aided and automatized precise and optimized ablations to minimize bleeding, discomfort, formation of strictures, and recurrence. Overall, the key to improving the prognosis and management of early esophageal cancers is to develop and adopt such emerging imaging modalities for earlier detection of neoplastic lesions and guide treatment. This is particularly of relevance with the emergence of endoscopic esophagus-sparing endoscopic ablative techniques. Assessing the specific location, depth of involvement, and status of nodal metastasis, and identifying features correlated with neoplastic progression or incomplete treatment may help optimize treatment and decrease recurrence rates. Major driving forces will depend not only on their efficacy, but of practicality in time, cost, and impact on clinical management of esophageal neoplasias.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the VA Innovator’s Network, CSR&D CX001146 and BLR&D BX004455 Merit Review Awards, from the Department of Veterans Affairs, NIH RO1CA075289-12 and NIH R01CA252216-01.

Footnotes

Competing interests:

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, et al. 2015. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut. 64: 381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. 2016. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 111: 30–50; quiz 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domper Arnal MJ, Ferrandez Arenas A & Lanas Arbeloa A. 2015. Esophageal cancer: Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World J Gastroenterol. 21: 7933–7943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. 2011. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 61: 69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandiah K, Chedgy FJ, Subramaniam S, et al. 2017. Early squamous neoplasia of the esophagus: The endoscopic approach to diagnosis and management. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 23: 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams JA, Kapel RC, Lindberg GM, et al. 2009. Adherence to biopsy guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance in the community setting in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7: 736–742; quiz 710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholvinck DW, van der Meulen K, Bergman J, et al. 2017. Detection of lesions in dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus by community and expert endoscopists. Endoscopy. 49: 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pohl H, Aschenbeck J, Drossel R, et al. 2008. Endoscopy in Barrett’s oesophagus: adherence to standards and neoplasia detection in the community practice versus hospital setting. J Intern Med. 264: 370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mashimo H, Wagh MS & Goyal RK. 2005. Surveillance and screening for Barrett esophagus and adenocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 39: S33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiyama J, Komanduri S, Konda VJ, et al. 2014. Endoscopy for diagnosis and treatment in esophageal cancers: high-technology assessment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1325: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lao-Sirieix P & Fitzgerald RC. 2012. Screening for oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 9: 278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chao YK, Kawada K, Kumagai Y, et al. 2014. On endocytoscopy and posttherapy pathologic staging in esophageal cancers, and on evidence-based methodology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1325: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumagai Y, Kawada K, Higashi M, et al. 2015. Endocytoscopic observation of various esophageal lesions at x600: can nuclear abnormality be recognized? Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 28: 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross SA, Smith MS, Kaul V, et al. 2018. Increased detection of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal dysplasia with adjunctive use of wide-area transepithelial sample with three-dimensional computer-assisted analysis (WATS). United European Gastroenterol J. 6: 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith MS, Ikonomi E, Bhuta R, et al. 2019. Wide-area transepithelial sampling with computer-assisted 3-dimensional analysis (WATS) markedly improves detection of esophageal dysplasia and Barrett’s esophagus: analysis from a prospective multicenter community-based study. Dis Esophagus. 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, O’Donovan M, et al. 2020. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 396: 333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Offman J, Muldrew B, O’Donovan M, et al. 2018. Barrett’s oESophagus trial 3 (BEST3): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial comparing the Cytosponge-TFF3 test with usual care to facilitate the diagnosis of oesophageal pre-cancer in primary care patients with chronic acid reflux. BMC Cancer. 18: 784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Kleeman S, Coburn SB, et al. 2018. Selection and Application of Tissue microRNAs for Nonendoscopic Diagnosis of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 155: 771–783 e773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moinova HR, LaFramboise T, Lutterbaugh JD, et al. 2018. Identifying DNA methylation biomarkers for non-endoscopic detection of Barrett’s esophagus. Sci Transl Med. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu M, Maden SK, Stachler M, et al. 2019. Subtypes of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma based on genome-wide methylation analysis. Gut. 68: 389–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Critchley-Thorne RJ, Davison JM, Prichard JW, et al. 2017. A Tissue Systems Pathology Test Detects Abnormalities Associated with Prevalent High-Grade Dysplasia and Esophageal Cancer in Barrett’s Esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 26: 240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Old O, Lloyd G, Isabelle M, et al. 2018. Automated cytological detection of Barrett’s neoplasia with infrared spectroscopy. J Gastroenterol. 53: 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critchley-Thorne RJ, Duits LC, Prichard JW, et al. 2016. A Tissue Systems Pathology Assay for High-Risk Barrett’s Esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 25: 958–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mashimo H 2013. Subsquamous intestinal metaplasia after ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: frequency and importance. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 29: 454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giganti F, Ambrosi A, Petrone MC, et al. 2016. Prospective comparison of MR with diffusion-weighted imaging, endoscopic ultrasound, MDCT and positron emission tomography-CT in the pre-operative staging of oesophageal cancer: results from a pilot study. Br J Radiol. 89: 20160087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thota PN, Sada A, Sanaka MR, et al. 2017. Correlation between endoscopic forceps biopsies and endoscopic mucosal resection with endoscopic ultrasound in patients with Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia and early cancer. Surg Endosc. 31: 1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergeron EJ, Lin J, Chang AC, et al. 2014. Endoscopic ultrasound is inadequate to determine which T1/T2 esophageal tumors are candidates for endoluminal therapies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 147: 765–771: Discussion 771–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qumseya BJ, Bartel MJ, Gendy S, et al. 2018. High rate of over-staging of Barrett’s neoplasia with endoscopic ultrasound: Systemic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 50: 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cameron GR, Jayasekera CS, Williams R, et al. 2014. Detection and staging of esophageal cancers within Barrett’s esophagus is improved by assessment in specialized Barrett’s units. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 80: 971–983 e971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita DT, Li C, Bethune D, et al. 2017. Endoscopic mucosal resection for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma: a Canadian experience. Can J Surg. 60: 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayano K, Ohira G, Hirata A, et al. 2019. Imaging biomarkers for the treatment of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 25: 3021–3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabelloni M, Faggioni L & Neri E. 2019. Imaging biomarkers in upper gastrointestinal cancers. British J Radiology Open 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Committee AT, Manfredi MA, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. 2015. Electronic chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 81: 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuznetsov K, Lambert R & Rey JF. 2006. Narrow-band imaging: potential and limitations. Endoscopy. 38: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma P, Hawes RH, Bansal A, et al. 2013. Standard endoscopy with random biopsies versus narrow band imaging targeted biopsies in Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, international, randomised controlled trial. Gut. 62: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asge Technology C, Song LM, Adler DG, et al. 2008. Narrow band imaging and multiband imaging. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 67: 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfsen HC, Crook JE, Krishna M, et al. 2008. Prospective, controlled tandem endoscopy study of narrow band imaging for dysplasia detection in Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology. 135: 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mannath J, Subramanian V, Hawkey CJ, et al. 2010. Narrow band imaging for characterization of high grade dysplasia and specialized intestinal metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 42: 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kara MA, Peters FP, Rosmolen WD, et al. 2005. High-resolution endoscopy plus chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging in Barrett’s esophagus: a prospective randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 37: 929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qumseya BJ, Wang H, Badie N, et al. 2013. Advanced imaging technologies increase detection of dysplasia and neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11: 1562–1570 e1561–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curvers W, Baak L, Kiesslich R, et al. 2008. Chromoendoscopy and narrow-band imaging compared with high-resolution magnification endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 134: 670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez Herrero L, Curvers WL, Bansal A, et al. 2009. Zooming in on Barrett oesophagus using narrow-band imaging: an international observer agreement study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21: 1068–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curvers WL, Bohmer CJ, Mallant-Hent RC, et al. 2008. Mucosal morphology in Barrett’s esophagus: interobserver agreement and role of narrow band imaging. Endoscopy. 40: 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva FB, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Vieth M, et al. 2011. Endoscopic assessment and grading of Barrett’s esophagus using magnification endoscopy and narrow-band imaging: accuracy and interobserver agreement of different classification systems (with videos). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 73: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma P, Bergman JJ, Goda K, et al. 2016. Development and Validation of a Classification System to Identify High-Grade Dysplasia and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s Esophagus Using Narrow-Band Imaging. Gastroenterology. 150: 591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nogales O, Caballero-Marcos A, Clemente-Sanchez A, et al. 2017. Usefulness of Non-magnifying Imaging in EVIS EXERA III Video Systems and High-Definition Endoscopes to Diagnose Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus Using the Barrett International NBI Group (BING) Classification. Dig Dis Sci. 62: 2840–2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh R, Lee SY, Vijay N, et al. 2014. Update on narrow band imaging in disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Dig Endosc. 26: 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Committee AT, Manfredi MA, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. 2015. Electronic chromoendoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 81: 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Osawa H & Yamamoto H. 2014. Present and future status of flexible spectral imaging color enhancement and blue laser imaging technology. Dig Endosc. 26 Suppl 1: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horie Y, Yoshio T, Aoyama K, et al. 2019. Diagnostic outcomes of esophageal cancer by artificial intelligence using convolutional neural networks. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 89: 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tokai Y, Yoshio T, Aoyama K, et al. 2020. Application of artificial intelligence using convolutional neural networks in determining the invasion depth of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horiuchi Y, Aoyama K, Tokai Y, et al. 2020. Convolutional Neural Network for Differentiating Gastric Cancer from Gastritis Using Magnified Endoscopy with Narrow Band Imaging. Dig Dis Sci. 65: 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lui TKL, Wong KKY, Mak LLY, et al. 2019. Endoscopic prediction of deeply submucosal invasive carcinoma with use of artificial intelligence. Endosc Int Open. 7: E514–E520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiesslich R, Burg J, Vieth M, et al. 2004. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 127: 706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.library Z.r. 2. http://zeiss-campus.magnet.fsu.edu/referencelibrary/laserconfocal.

- 56.Goetz M 2012. Confocal laser endomicroscopy: current indications and future perspectives in gastrointestinal disease. Endoscopia. 24: 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiesslich R, Gossner L, Goetz M, et al. 2006. In vivo histology of Barrett’s esophagus and associated neoplasia by confocal laser endomicroscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4: 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wallace M, Lauwers GY, Chen Y, et al. 2011. Miami classification for probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy. Endoscopy. 43: 882–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma P, Meining AR, Coron E, et al. 2011. Real-time increased detection of neoplastic tissue in Barrett’s esophagus with probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy: final results of an international multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 74: 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jayasekera C, Taylor AC, Desmond PV, et al. 2012. Added value of narrow band imaging and confocal laser endomicroscopy in detecting Barrett’s esophagus neoplasia. Endoscopy. 44: 1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bertani H, Frazzoni M, Dabizzi E, et al. 2013. Improved detection of incident dysplasia by probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy in a Barrett’s esophagus surveillance program. Dig Dis Sci. 58: 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canto MI, Anandasabapathy S, Brugge W, et al. 2014. In vivo endomicroscopy improves detection of Barrett’s esophagus-related neoplasia: a multicenter international randomized controlled trial (with video). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 79: 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiong YQ, Ma SJ, Hu HY, et al. 2018. Comparison of narrow-band imaging and confocal laser endomicroscopy for the detection of neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: A meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 42: 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gaddam S, Mathur SC, Singh M, et al. 2011. Novel probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy criteria and interobserver agreement for the detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 106: 1961–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Committee AT, Thosani N, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. 2016. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations thresholds for adopting real-time imaging-assisted endoscopic targeted biopsy during endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 83: 684–698 e687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Committee AT, Song LM, Adler DG, et al. 2008. Narrow band imaging and multiband imaging. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 67: 581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu J, Pan YM, Wang TT, et al. 2014. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for detection of neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 27: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bennett M & Mashimo H. 2014. Molecular markers and imaging tools to identify malignant potential in Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 5: 438–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sturm MB & Wang TD. 2015. Emerging optical methods for surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 64: 1816–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JH & Wang TD. 2016. Molecular endoscopy for targeted imaging in the digestive tract. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1: 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pech O, Rabenstein T, Manner H, et al. 2008. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for in vivo diagnosis of early squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu H, Li YQ, Yu T, et al. 2009. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Endoscopy. 41: 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.di Pietro M, Bird-Lieberman EL, Liu X, et al. 2015. Autofluorescence-Directed Confocal Endomicroscopy in Combination With a Three-Biomarker Panel Can Inform Management Decisions in Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 110: 1549–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samel NS & Mashimo H. 2019. Applications of OCT in the gastrointestinal tract. Appl. Sci. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leggett CL, Gorospe EC, Chan DK, et al. 2016. Comparative diagnostic performance of volumetric laser endomicroscopy and confocal laser endomicroscopy in the detection of dysplasia associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 83: 880–888 e882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans JA, Poneros JM, Bouma BE, et al. 2006. Optical coherence tomography to identify intramucosal carcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4: 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Trindade AJ, Inamdar S, Smith MS, et al. 2017. Learning curve and competence for volumetric laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus using cumulative sum analysis. Endoscopy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trindade AJ, Inamdar S, Smith MS, et al. 2017. Volumetric laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus: interobserver agreement for interpretation of Barrett’s esophagus and associated neoplasia among high-frequency users. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 86: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alshelleh M, Inamdar S, McKinley M, et al. 2018. Incremental yield of dysplasia detection in Barrett’s esophagus using volumetric laser endomicroscopy with and without laser marking compared with a standardized random biopsy protocol. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith MS, Cash B, Konda V, et al. 2019. Volumetric laser endomicroscopy and its application to Barrett’s esophagus: results from a 1,000 patient registry. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kohli DR, Schubert ML, Zfass AM, et al. 2017. Performance characteristics of optical coherence tomography in assessment of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer: systematic review. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 30: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tsai TH, Zhou C, Tao YK, et al. 2012. Structural markers observed with endoscopic 3-dimensional optical coherence tomography correlating with Barrett’s esophagus radiofrequency ablation treatment response (with videos). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 76: 1104–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsai TH, Zhou C, Lee HC, et al. 2012. Comparison of Tissue Architectural Changes between Radiofrequency Ablation and Cryospray Ablation in Barrett’s Esophagus Using Endoscopic Three-Dimensional Optical Coherence Tomography. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012: 684832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee HC, Ahsen OO, Liu JJ, et al. 2017. Assessment of the radiofrequency ablation dynamics of esophageal tissue with optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt. 22: 76001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adler DC, Zhou C, Tsai TH, et al. 2009. Three-dimensional optical coherence tomography of Barrett’s esophagus and buried glands beneath neosquamous epithelium following radiofrequency ablation. Endoscopy. 41: 773–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou C, Tsai TH, Lee HC, et al. 2012. Characterization of buried glands before and after radiofrequency ablation by using 3-dimensional optical coherence tomography (with videos). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 76: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Basavappa M, Weinberg A, Huang Q, et al. 2014. Markers suggest reduced malignant potential of subsquamous intestinal metaplasia compared with Barrett’s esophagus. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 27: 262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Trindade AJ, Raphael KL, Inamdar S, et al. 2019. Volumetric laser endomicroscopy features of dysplasia at the gastric cardia in Barrett’s oesophagus: results from an observational cohort study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 6: e000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liang K, Ahsen OO, Wang Z, et al. 2017. Endoscopic forward-viewing optical coherence tomography and angiography with MHz swept source. Opt Lett. 42: 3193–3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsai TH, Ahsen OO, Lee HC, et al. 2014. Endoscopic optical coherence angiography enables 3-dimensional visualization of subsurface microvasculature. Gastroenterology. 147: 1219–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahsen OO, Lee HC, Giacomelli MG, et al. 2014. Correction of rotational distortion for catheter-based en face OCT and OCT angiography. Opt Lett. 39: 5973–5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee HC, Ahsen OO, Liang K, et al. 2017. Endoscopic optical coherence tomography angiography microvascular features associated with dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus (with video). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 86: 476–484 e473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ahsen OO, Lee HC, Liang K, et al. 2017. Ultrahigh-speed endoscopic optical coherence tomography and angiography enables delineation of lateral margins of endoscopic mucosal resection: a case report. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 10: 931–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hatta W, Uno K, Koike T, et al. 2012. A prospective comparative study of optical coherence tomography and EUS for tumor staging of superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 76: 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Trindade AJ, Rishi A, Stein PH, et al. 2016. Use of volumetric laser endomicroscopy in staging multifocal superficial squamous carcinoma of the esophagus. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 84: 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsai TH, Fujimoto JG & Mashimo H. 2014. Endoscopic Optical Coherence Tomography for Clinical Gastroenterology. Diagnostics (Basel). 4: 57–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kamboj AK, Hoversten P, Kahn AK, et al. 2019. Interpretation of volumetric laser endomicroscopy in Barrett’s esophagus using image enhancement software. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aguirre AD, Chen Y, Bryan B, et al. 2010. Cellular resolution ex vivo imaging of gastrointestinal tissues with optical coherence microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 15: 016025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahsen OO, Liang K, Lee HC, et al. 2019. Assessment of Barrett’s esophagus and dysplasia with ultrahigh-speed volumetric en face and cross-sectional optical coherence tomography. Endoscopy. 51: 355–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liang K, Wang Z, Ahsen OO, et al. 2018. Cycloid scanning for wide field optical coherence tomography endomicroscopy and angiography in vivo. Optica. 5: 36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhao Y, Eldridge WJ, Maher JR, et al. 2017. Dual-axis optical coherence tomography for deep tissue imaging. Opt Lett. 42: 2302–2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM, Brill JV, et al. 2007. Cost utility of screening for Barrett’s esophagus with esophageal capsule endoscopy versus conventional upper endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5: 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gora MJ, Queneherve L, Carruth RW, et al. 2018. Tethered capsule endomicroscopy for microscopic imaging of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum without sedation in humans (with video). Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 88: 830–840 e833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liang K, Ahsen OO, Lee HC, et al. 2016. Volumetric Mapping of Barrett’s Esophagus and Dysplasia With en face Optical Coherence Tomography Tethered Capsule. Am J Gastroenterol. 111: 1664–1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ughi GJ, Gora MJ, Swager AF, et al. 2016. Automated segmentation and characterization of esophageal wall in vivo by tethered capsule optical coherence tomography endomicroscopy. Biomed Opt Express. 7: 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mourant JR, Bigio IJ, Boyer J, et al. 1995. Spectroscopic diagnosis of bladder cancer with elastic light scattering. Lasers Surg Med. 17: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mourant JR, Bigio IJ, Boyer JD, et al. 1996. Elastic scattering spectroscopy as a diagnostic tool for differentiating pathologies in the gastrointestinal tract: preliminary testing. J Biomed Opt. 1: 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mourant JR, Boyer J, Hielscher AH, et al. 1996. Influence of the scattering phase function on light transport measurements in turbid media performed with small source-detector separations. Opt Lett. 21: 546–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fang H, Qiu L, Vitkin E, et al. 2007. Confocal light absorption and scattering spectroscopic microscopy. Appl Opt. 46: 1760–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baak JP, ten Kate FJ, Offerhaus GJ, et al. 2002. Routine morphometrical analysis can improve reproducibility of dysplasia grade in Barrett’s oesophagus surveillance biopsies. J Clin Pathol. 55: 910–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Johnson KS, Chicken DW, Pickard DC, et al. 2004. Elastic scattering spectroscopy for intraoperative determination of sentinel lymph node status in the breast. J Biomed Opt. 9: 1122–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dhar A, Johnson KS, Novelli MR, et al. 2006. Elastic scattering spectroscopy for the diagnosis of colonic lesions: initial results of a novel optical biopsy technique. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 63: 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rodriguez-Diaz E, Castanon DA, Singh SK, et al. 2011. Spectral classifier design with ensemble classifiers and misclassification-rejection: application to elastic-scattering spectroscopy for detection of colonic neoplasia. J Biomed Opt. 16: 067009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rosen JE, Suh H, Giordano NJ, et al. 2014. Preoperative discrimination of benign from malignant disease in thyroid nodules with indeterminate cytology using elastic light-scattering spectroscopy. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 61: 2336–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rodriguez-Diaz E, Atkinson C, Jepeal LI, et al. 2014. Elastic scattering spectroscopy as an optical marker of inflammatory bowel disease activity and subtypes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 20: 1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rodriguez-Diaz E, Huang Q, Cerda SR, et al. 2015. Endoscopic histological assessment of colonic polyps by using elastic scattering spectroscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 81: 539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rodriguez-Diaz E, Manolakos D, Christman H, et al. 2019. Optical Spectroscopy as a Method for Skin Cancer Risk Assessment. Photochem Photobiol. 95: 1441–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Grillone GA, Wang Z, Krisciunas GP, et al. 2017. The color of cancer: Margin guidance for oral cancer resection using elastic scattering spectroscopy. The Laryngoscope. 127 Suppl 4: S1–S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lovat LB, Johnson K, Mackenzie GD, et al. 2006. Elastic scattering spectroscopy accurately detects high grade dysplasia and cancer in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 55: 1078–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lovat L & Bown S. 2004. Elastic scattering spectroscopy for detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 14: 507–517, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhu Y, Fearn T, Mackenzie G, et al. 2009. Elastic scattering spectroscopy for detection of cancer risk in Barrett’s esophagus: experimental and clinical validation of error removal by orthogonal subtraction for increasing accuracy. J Biomed Opt. 14: 044022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Rodriguez-Diaz E, Jepeal LI, Sharma A, et al. 2013. Optical Sensing of Dysplasia and Field Effect of Carcinogenesis in Barrett’s Esophagus Using Elastic-Scattering Spectroscopy. Gastroenterology. 144: S117. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liang S, Ma T, Jing J, et al. 2014. Trimodality imaging system and intravascular endoscopic probe: combined optical coherence tomography, fluorescence imaging and ultrasound imaging. Opt Lett. 39: 6652–6655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shang S, Chen Z, Zhao Y, et al. 2017. Simultaneous imaging of atherosclerotic plaque composition and structure with dual-mode photoacoustic and optical coherence tomography. Opt Express. 25: 530–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tang Q, Wang J, Frank A, et al. 2016. Depth-resolved imaging of colon tumor using optical coherence tomography and fluorescence laminar optical tomography. Biomed Opt Express. 7: 5218–5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen Z, Yang S & Xing D. 2016. Optically integrated trimodality imaging system: combined all-optical photoacoustic microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescence imaging. Opt Lett. 41: 1636–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhu Y, Terry NG & Wax A. 2012. Angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry: an optical biopsy technique for clinical detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6: 37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Roy HK & Backman V. 2012. Spectroscopic applications in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 10: 1335–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Qiu L, Zhang L, Turzhitsky V, et al. 2019. Multispectral Endoscopy with Light Gating for Early Cancer Detection. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Song G, Steelman ZA, Kendall W, et al. 2020. Spatial scanning of a sample with two-dimensional angle-resolved low-coherence interferometry for analysis of anisotropic scatterers. Biomed Opt Express. 11: 4419–4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang H, Steelman ZA, Ho DS, et al. 2019. Angular range, sampling and noise considerations for inverse light scattering analysis of nuclear morphology. J Biophotonics. 12: e201800258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Terry NG, Zhu Y, Rinehart MT, et al. 2011. Detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus with in vivo depth-resolved nuclear morphology measurements. Gastroenterology. 140: 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Backman V, Wallace MB, Perelman LT, et al. 2000. Detection of preinvasive cancer cells. Nature. 406: 35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Qiu L, Pleskow DK, Chuttani R, et al. 2010. Multispectral scanning during endoscopy guides biopsy of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Nat Med. 16: 603–606, 601p following 606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Trindade AJ, McKinley MJ, Fan C, et al. 2019. Endoscopic Surveillance of Barrett’s Esophagus Using Volumetric Laser Endomicroscopy With Artificial Intelligence Image Enhancement. Gastroenterology. 157: 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]