Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite a high incidence of brain metastases in patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), limited data exist on the use of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), specifically Gamma Knife™ radiosurgery (Elekta AB), for SCLC brain metastases.

OBJECTIVE

To provide a detailed analysis of SCLC patients treated with SRS, focusing on local failure, distant brain failure, and overall survival (OS).

METHODS

A multi-institutional retrospective review was performed on 293 patients undergoing SRS for SCLC brain metastases at 10 medical centers from 1991 to 2017. Data collection was performed according to individual institutional review boards, and analyses were performed using binary logistic regression, Cox-proportional hazard models, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, and competing risks analysis.

RESULTS

Two hundred thirty-two (79%) patients received SRS as salvage following prior whole-brain irradiation (WBRT) or prophylactic cranial irradiation, with a median marginal dose of 18 Gy. At median follow-up after SRS of 6.4 and 18.0 mo for surviving patients, the 1-yr local failure, distant brain failure, and OS were 31%, 49%, and 28%. The interval between WBRT and SRS was predictive of improved OS for patients receiving SRS more than 1 yr after initial treatment (21%, <1 yr vs 36%, >1 yr, P = .01). On multivariate analysis, older age was the only significant predictor for OS (hazard ratio 1.63, 95% CI 1.16-2.29, P = .005).

CONCLUSION

SRS plays an important role in the management of brain metastases from SCLC, especially in salvage therapy following WBRT. Ongoing prospective trials will better assess the value of radiosurgery in the primary management of SCLC brain metastases and potentially challenge the standard application of WBRT in SCLC patients.

Keywords: Gamma Knife, Small-cell lung cancer, Stereotactic radiosurgery, Whole-brain radiation

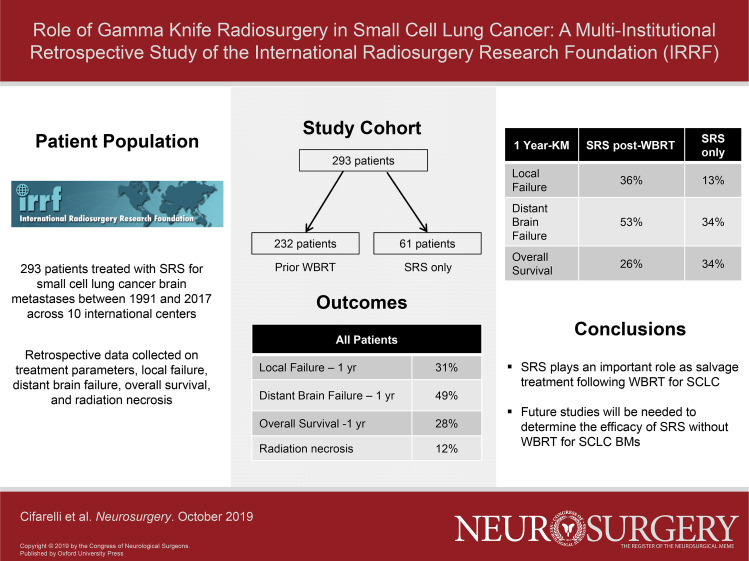

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CI

confidence interval

- CIC

cumulative incidence curve

- CIF

cumulative incidence function

- GKRS

Gamma Knife radiosurgery

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

Interquartile rank

- IRRF

International Radiosurgery Research Foundation

- KM

Kaplan-Meier

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OS

overall survival

- PCI

prophylactic cranial irradiation

- RN

radiation necrosis

- SCLC

small-cell lung cancer

- SRS

stereotactic radiosurgery

- WBRT

whole-brain irradiation

Brain metastases are a nearly uniform part of the disease course in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), with autopsy series documenting that upwards of 80% of patients with extensive stage SCLC will suffer brain metastases.1 Whole-brain irradiation (WBRT) has historically remained a standard of care based on the prior noted survival improvements with prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) in extensive stage SCLC from EORTC 08993/22993 and concerns of a perceived high distant brain failure rates without WBRT. However, recent randomized data in the era of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) surveillance have questioned the routine application of PCI, noting a detrimental impact of PCI on overall survival when compared to observation with serial MRI.2 These findings, combined with increasingly recognized risks of the neurocognitive effects of WBRT, have led to a reappraisal of the potential role of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) in the management of small-cell brain metastases.3 Previous data for the role of SCLC brain metastases have been predominantly limited to small single-institution retrospective series with heterogeneous inclusion criteria and significant selection biases.4-6 Thus, we aimed to combine multi-institutional data from the International Radiosurgery Research Foundation (IRRF) to provide a descriptive review of patient outcomes following SRS treatment and identify predictors that may better guide the potential application of SRS in SCLC brain metastases.

METHODS

Data Collection and Follow-up

Following approval of the proposal by the IRRF protocol review committee, a multi-institutional retrospective dataset was formed across the IRRF. Under review and approval from each institution's respective Institutional Review Board, a total of 10 centers submitted data for analysis. All data were submitted to a central third party using a standardized data collection template prior to submission in de-identified format to the corresponding author for data analysis. All data collection was retrospective and found to be exempt from necessitating individual patient consents. Inclusion criteria included brain metastases from SCLC histology treated with Gamma Knife™ (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) radiosurgery (GKRS). There were no exclusion criteria based on prior WBRT or PCI; however, 10 patients who had SRS followed by planned WBRT as primary management of their brain metastases were excluded. Similarly, SRS following WBRT was performed as a salvage procedure, not as a planned boost to previously treated disease. Data collection included the following variables: gender, age, presence of brain metastases at time of SCLC diagnosis, PCI, WBRT, specifics of SRS, toxicity, MRI brain follow-up results, cause of death, and overall survival time.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). Comparisons between WBRT with salvage SRS and SRS-only cohorts in terms of baseline characteristics were completed using binary logistic regression. Local failure was defined as tumor growth at any site treated with SRS and was measured from the date of SRS to the date of last imaging follow-up using both the Kaplan-Meier (KM) estimator and cumulative incidence curve (CIC) plotting.7 Distant brain failure was defined as failure at any site within the brain not treated with SRS and was similarly measured from the date of SRS to the date of last imaging follow-up using the Kaplan-Meier method and the CIC method. Radiation necrosis was distinguished from tumor growth primarily based on gadolinium-enhanced MRI with and without perfusion imaging. Overall survival was calculated from the date of SRS to the date of death or last follow-up using the Kaplan-Meier method. Patients recorded as presumed dead by the respective center without a recorded date of death were conservatively calculated as deceased on the date of last contact, as defined by the National Cancer Institute for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data collection. Cause of death was categorized as either systemic disease, neurological, or unknown, with neurological death defined as occurring in patients in whom systemic disease was stable with progressive neurological decline or in patients with both progressive systemic disease and concurrent neurological decline as per Patchell et al.8 Comparisons between groups treated with either SRS alone or SRS salvage following WBRT were made using log rank tests. To account for potential biases due to retrospective design, multivariable analyses were performed using Cox regression using forced entry selection methods correcting for age, gender, time to appearance of intracranial disease relative to diagnosis (synchronous vs metachronous), SRS mean marginal dose, total volume of metastases treated with SRS, and total number of metastases treated with SRS. Additionally, reirradiation interval from prior WBRT was analyzed for the subgroup receiving salvage SRS. Data were analyzed including all patients and then separated by the 2 clinical scenarios in which SRS was used: SRS alone with no prior WBRT and SRS as salvage following prior WBRT. A P < .05 was considered significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Population

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics for the included 293 patients managed with SRS for brain metastases secondary to SCLC at the 10 contributing Gamma Knife™ Centers. Briefly, the median age was 63 yr (Interquartile rank (IQR): 56-68), the majority were treated with salvage SRS and WBRT 79% (n = 232) at a median time from WBRT to SRS of 258 d (IQR: 166-431). Of the 232 patients treated with SRS as salvage following prior WBRT, 59% were recorded as being PCI. The median prior dose for WBRT was 30 Gy (IQR: 25-30 Gy). The median number of metastases treated with SRS was 2 (IQR: 1-5), with a median total metastases tumor volume treated of 3.3 cc (IQR: 0.50-6.03). The median SRS mean marginal dose was 18.0 Gy (IQR: 16.0-19.84) in 1 fraction. The median follow-up after SRS was 6.4 mo (IQR: 3.0-12.5) for all included patients and 18.0 mo (IQR: 8.0-52.0) for patients surviving at the time of data collection. Cause of death was recorded for 139 patients of which 64% died of systemic disease, 29% neurological death, 5% both uncontrolled systemic disease and neurological death, and 3% unrelated causes. Salvage intracranial therapy after SRS was as follows: WBRT (n = 21), repeat SRS (n = 68), craniotomy (n = 17), and laser interstitial thermal therapy (n = 2).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | All patients (N = 293) n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 63 (IQR: 56-68) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 144 (49%) |

| Female | 141 (58%) |

| Unrecorded | 8 (3%) |

| Time of appearance of brain metastases | |

| Metachronous | 161 (60%) |

| Synchronous | 106 (40%) |

| Prior whole-brain irradiation | |

| No | 61 (21%) |

| Yes | 232 (79%) |

| Number of metastases >2 cm treated with GKRS | |

| 0 | 167 (57) |

| 1 | 95 (32) |

| 2 | 13 (4) |

| 3 | 4 (1) |

| Unrecorded | 14 (5) |

| Time from WBRT to SRS, days | 258 (IQR: 166-431) |

| Total number of lesions treated with SRS | 2 (IQR: 1-5) |

| Total SRS treatment volume, cc | 3.3 (IQR: 0.91-7.60) |

| Largest brain metastases SRS volume | 1.86 (0.50-6.03) |

| Mean SRS marginal dose, Gy | 18.0 (16.0-19.84) |

Local Failure, Distant Failure, and Overall Survival

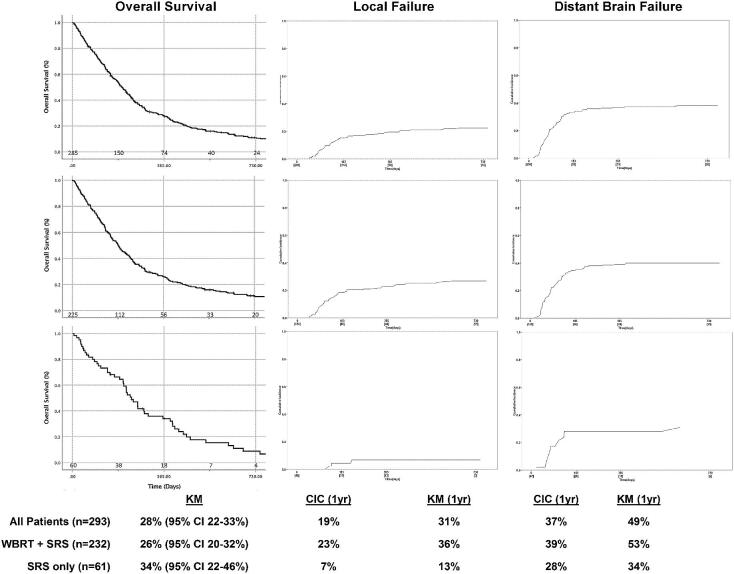

For all patients, the K-M estimated 1-yr local failure, distant brain failure, and overall survival were 31% (95% CI 22%-40%), 49% (95% CI 40%-58%), and 28% (95% CI 22%-33%), respectively. The cumulative incidence function (CIF) on competing risks analysis for 1-yr local failure and distant brain failure were 19% and 37%, respectively (Figure 1). On univariate analysis, factors significantly affecting local failure after SRS included gender (1-yr local failure 23% female vs 41% male, P = .04) and SRS alone without WBRT (1-yr local failure 13% for patients treated with SRS alone vs 36% for salvage SRS and WBRT, P = .017). On multivariate analysis, SRS alone remained a significant predictor of local control (hazard ratio [HR] = 11.21, 95% CI 1.43-88.11, P = .02). On univariate analysis, the only factor significantly associated with distant brain control was number of lesions treated with SRS (1-yr distant brain control 65% for SRS to ≤2 lesions vs 36% for GKRS to >2 lesions, P = .001). However, on multivariate analysis, this effect was not confirmed. On univariate analysis, the only factors significantly affecting overall survival after SRS were age (1-yr overall survival 33% age ≤63 vs 22% for age >63, P = .002) and the number of metastases treated with SRS (1-yr overall survival 33% for SRS to ≤2 lesions vs 23% for SRS to >2 lesions, P = .02). On multivariate analysis, younger age remained the only significant predictor for overall survival (HR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.16–2.29, P = .005).

FIGURE 1.

Tumor control and survival following SRS for small-cell brain metastases: (top row) all patients, (middle row) SRS salvage following prior WBRT, and (bottom row) SRS alone (without prior WBRT). N below X-axis = number at risk; CIC = cumulative incidence curve; KM = Kaplan-Meier estimation.

Within the subgroup of patients receiving SRS following prior WBRT, 59% (n = 136) were recorded as PCI compared to 41% (n = 94) recorded as being therapeutic WBRT for documented brain metastases, and for 2 patients, this variable was unrecorded. The median time from PCI to SRS was 10.1 mo (IQR: 5.8-16.3) vs 7.1 mo (IQR: 5.2-12.4) in patients receiving salvage SRS after therapeutic WBRT. No significant differences were noted in local failure (1-yr local failure 33% for SRS following PCI vs 42% for SRS following WBRT, P = .18), distant brain failure (1-yr distant brain failure 53% for SRS following PCI vs 49% for SRS following WBRT, P = .79), and overall survival (1-yr overall survival 28% for SRS following PCI vs 24% for salvage SRS following WBRT, P = .84).

Radiation Necrosis

Of the 293 patients analyzed, 34 (12%) had documented radiation necrosis (RN) in follow-up. Of these patients, 31 (91%) had the diagnosis of RN made on MRI and 3 (9%) had biopsy-proven diagnoses. Of the 34 patients, 16 (47%) were symptomatic because of adverse radiation effects and 14 (88%) of the symptomatic patients were treated with steroids for the symptom management. Two patients with RN underwent surgical resection to alleviate symptoms. Further analysis of the RN patients compared to the non-RN patients revealed that the minimum, mean, and maximal margin doses of 18.2 vs 17.3 Gy (P = .15), 19.7 vs 17.7 Gy (P = .002), and 26.5 vs 22.2 Gy (P = .012), with the mean and maximal margin doses being significantly higher in the RN patients. Finally, 31 of the 34 patients with RN had received either PCI or WBRT at the time of diagnosis. Multivariate analysis failed to identify any significant predictors of RN in the patient population.

SRS Alone vs SRS Salvage Following WBRT

Table 2 compares baseline characteristics for patients receiving SRS alone vs salvage SRS plus WBRT. For the 61 patients managed by SRS alone without WBRT, the median follow-up was 7.5 mo (IQR: 3.3-13.3) and 9.3 (IQR: 5.1-14.8) for surviving patients. The 1-yr local failure, distant brain failure, and overall survival were 13% (95% CI 0%-28%), 34% (95% CI 19%-49%), and 34% (95% CI 22%-46%), respectively, based on KM estimation. Accounting for the competing risk of death, 1-yr local failure in the SRS-only cohort was 7% and 1-yr distant brain failure was 28% according to the CIC (Figure 1). No significant predictors of local control were noted. The total number of lesions treated with SRS was a significant predictor of distant brain failure (1-yr distant brain failure 23% for SRS to ≤2 lesions vs 61% for SRS to >2 lesions, P = .01) and overall survival (1-yr overall survival for SRS to ≤2 lesions 45% vs 15% for SRS to >2 lesions, P = .001). However, on multivariate analysis, this effect was not confirmed, though there was a strong trend for inferior overall survival for SRS to a total >2 lesions (HR = 2.53, 95% CI 0.99-5.58, P = .05).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics by Primary (No Prior WBRT) vs Salvage SRS (Prior WBRT)

| SRS alone (n = 61) | SRS + prior WBRT (n = 232) | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| ≤63 yr | 21 (34%) | 133 (57%) | 1 | Reference | |

| >63 yr | 40 (66%) | 99 (43%) | 0.39 | 0.22-0.70 | .002 |

| Gender (n = 285) | |||||

| Female | 24 (41%) | 120 (53%) | 1 | Reference | |

| Male | 34 (59%) | 107 (47%) | 0.63 | 0.35-1.13 | .12 |

| Time to brain metastases | |||||

| Metachronous | 26 (43%) | 153 (66%) | 1 | Reference | |

| Synchronous | 35 (57%) | 79 (34%) | 0.38 | 0.21-0.68 | .001 |

| SRS mean marginal dose (n = 244) | |||||

| ≤18.0 Gy | 35 (61%) | 129 (69%) | 1 | Reference | |

| >18.0 Gy | 22 (39%) | 58 (31%) | 1.40 | 0.76-2.59 | .29 |

| Volume of metastases (n = 251) | |||||

| ≤3.3 cc | 26 (50%) | 103 (52%) | 1 | Reference | |

| >3.3 cc | 26 (50%) | 96 (48%) | 0.93 | 0.51-1.72 | .82 |

| Number of metastases | |||||

| ≤2 | 39 (64%) | 115 (50%) | 1 | Reference | |

| >2 | 22 (36%) | 117 (50%) | 1.80 | 1.01-3.23 | .05 |

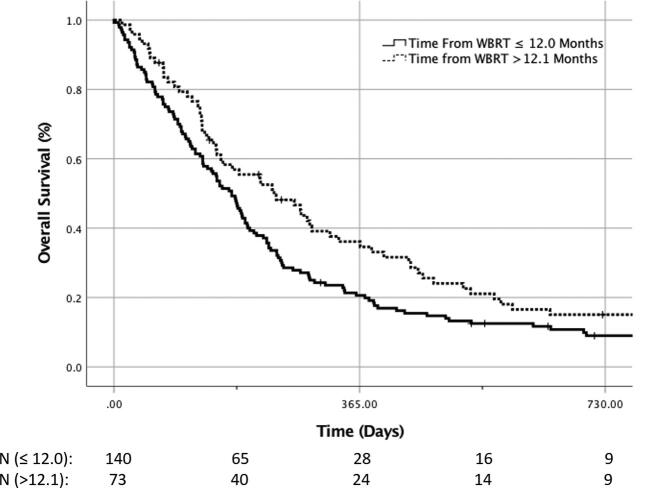

For the 232 patients with salvage SRS after WBRT, the median follow-up was 6.1 mo (IQR: 3.0-12.1) for all patients and 23.8 mo (IQR: 9.3-84.1) for patients surviving at the time of data collection. The 1-yr local failure, distant brain failure, and overall survival were 36% (95% CI 26%-46%), 53% (95% CI 43%-62%), and 26% (95% CI 20%-32%), respectively, based on KM estimation. Accounting for the competing risk of death, 1-yr local failure in the WBRT plus SRS cohort was 23%, and the distant brain failure was 39% according to the CIC (Figure 1). On univariate analysis, factors significantly affecting local control after salvage SRS included gender (1-yr local failure 27% female vs 65% male, P = .02); however, this was not confirmed on multivariate analysis. On univariate analysis, factors significantly affecting distant brain failure after salvage SRS included gender (1-yr local failure 38% female vs 68% male, P = .02) and number of lesions treated with SRS (1-yr distant brain failure 40% for SRS to ≤2 lesions vs 64% for SRS to >2 lesions, P = .03); however, this was not confirmed on multivariate analysis. On univariate analysis, patient age at the time of SRS was a significant predictor of outcome (1-yr overall survival 33% age ≤63 vs 17% for age >63, P = .002). Similarly, the interval of time from WBRT commencement to SRS being greater than 1 yr was a significant predictor of overall survival on univariate analysis (1-yr overall 21% survival ≤1 yr from WBRT to SRS vs 36% >1 yr, P = .01) (Figure 2). On multivariate analysis, only age (HR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.41-0.88, P = .008) and SRS dose (HR = 1.48, 95% CI 1.01-2.17, P = .04) remained significant. The time interval from WBRT to SRS >1 yr only trended toward significance (HR = 1.40, 95% CI 0.96-2.04, P = .08).

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival for patients treated with salvage SRS following by time interval from prior WBRT. N = N at risk. Patients were analyzed for overall survival based on the salvage SRS being performed at greater than or less than 1 yr post WBRT.

DISCUSSION

Despite the trend toward acceptance of SRS as a primary treatment method for most brain metastases, WBRT, given prophylactically or in response to MRI detectable brain metastases, has remained the mainstay of treatment in SCLC. Reports of the use of SRS in the setting of SCLC have been made over the past 15 yr, in which the primary indication was salvage therapy following WBRT,4,6,9,10 with a recent emergence of data describing the use of SRS as a primary treatment modality alternative to WBRT.5 Combined with the recognized risks of neurocognitive toxicity associated with WBRT, there has been a reappraisal of the potential role of SRS in SCLC brain metastases, including the proposed ENCEPHALON trial, comparing WBRT to SRS using the CyberKnife™ (Accuray Inc, Sunnyvale, California).11,12

In the current international multi-institutional retrospective study, inclusive of patients treated with salvage SRS following WBRT and a subset of patients receiving SRS only, the majority (64%) of patients succumb to systemic disease as opposed to neurologically associated death (34%), indicating some element of CNS disease control in both treatment paradigms. These findings are in accordance with single-institution reports from other groups primarily using SRS as salvage therapy in which neurological death from SCLC ranged from 18% to 53%,13,14 whereas the prior SRS-only study reported 1- and 2-yr neurological death rates to be 5% and 13%, respectively.5 From a historic prospective, the phase II study from the EORTC examining the role of WBRT in patients with brain-only metastases from SCLC highlighted the modest benefits of WBRT in SCLC with a median survival of 4.7 mo, response rate of only 50%, and poor intracranial control with intracranial progression the first site of progression in 79% of patients.15 Results from series utilizing repeat WBRT irradiation in patients with intracranial failure after prior PCI were even more dismal with a median overall survival of 2 to 3 mo.16,17 These data are in comparison to our results with a 1-yr overall survival of 28% (corresponding to a median survival of 6.6 mo) for a population of which 79% were treated for recurrent brain metastases after prior WBRT (the majority [59%] of which was PCI), and only a minority (34%) died of neurological death from uncontrolled intracranial disease. With that said, any challenges to the standard use of WBRT in SCLC would need to be supported by prospective clinical trial data, well beyond the scope of this retrospective analysis.

As most of our patient population received SRS as a salvage treatment following WBRT, we sought to identify factors predictive of improved overall survival with the addition of SRS. Our results for improved overall survival following salvage SRS in patients of younger age highlight the importance of previously identified factors impacting survival in brain metastases when considering patient selection for SRS.18 Others have previously noted factors specific to SCLC brain metastases treated with WBRT including performance status, time to appearance of intracranial disease (synchronous vs metachronous), response to chemotherapy, and Recursive partitioning analysis class.19 Although we did not validate the potential impact of synchronous vs metachronous brain metastases in this series, we did highlight an additional factor to potentially help select patients for salvage SRS vs repeat WBRT, that being the time from prior WBRT to SRS >1 yr (see Figure 2). Reirradiation interval has consistently been identified as an important factor in selecting patients for such treatment in other disease sites in which reirradiation is routine applied. This may also be an important factor in recurrent small-cell brain metastases.20

The incidence of RN among patients receiving SRS-based treatment for brain metastases has been the subject of extensive study.21,22 Perhaps the most widely accepted conclusion regarding RN in the setting of SRS is that the rates of RN are higher among patients who have previously received cranial radiation, either as SRS or WBRT.23,24 In our study, the rate of RN was 12%, which confirms rates defined by other studies including the landmark RTOG 90-05, in which the 2-yr rate of RN was 11%.25 The difference in the mean and maximal margin doses of SRS between the RN and non-RN patients is statistically significant, but the study was not powered to identify predictors of RN, and the retrospective nature of the study makes the calculation of V12 or V10 values difficult. A prospective study would be better equipped to directly address the issue of RN in this patient population.

Perhaps one of the most striking findings of our study was the improved local control in the SRS-only cohort compared to the SRS following WBRT patients, 87% (K-M estimation) and 93% (cumulative incidence) vs 64% (K-M estimation) and 77% (cumulative incidence), respectively (P = .017). Although the worse local control in lesions that likely received more total radiation between WBRT and SRS may seem counterintuitive, this may represent the phenomenon of clonal expansion of relatively radio-resistant cells that did not undergo complete response to the initial WBRT. Alternatively, these failures may result from the development of resistance from the mutagenic activity of chemoradiation. Several groups have proposed mechanisms for resistance development, but no distinct strategy currently exists to specifically identify and overcome it, although liquid biopsy for the identification of circulating tumor DNA may hold promise.26,27

As radiosurgical approaches, Gamma Knife™ (Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden), CyberKnife® (Accuray Inc, Sunnyvale, California), and Linac-based platforms intrinsically depend on focused targeting of radiographically identifiable lesions. The presumed presence of radiographically occult lesions and high rate of distant brain failure in patients not receiving prophylactic radiation have served as the basis for the long-standing argument against the use of radiosurgery in the primary treatment of patients with SCLC.28,29 However, patterns of intracranial failure in the MRI era would not support this hypothesis, with the majority of patients with small-cell brain metastases presenting with <5 brain metastases and 29% with a single-brain metastasis.30 In our study, the rate of distant brain failure at 1 yr was 49% (95% CI 40%-58%) for the entire population and 34% (95% CI 19%-49%) vs 53% (95% CI 43%-62%) for the SRS-only vs SRS-following-WBRT groups, respectively. Accounting for the competing risk of death, the 1-yr distant brain failure rate in the SRS-only group was 28% vs 39% in the salvage SRS following WBRT cohort. In comparison to landmark studies comparing radiosurgery alone to radiosurgery plus WBRT that excluded SCLC histology, distant brain failure rates were 36% to 55%.31-34 Thus, given the comparable rates of distant brain failure, the potential impact of PCI or WBRT on cognitive function,2 and the impact on overall survival (median 6.6 mo), we believe that the data from our cohort support a role from SRS in the management of brain metastases from SCLC. Ongoing studies, such as the ENCEPHALON trial, will help shed light on the potential neurocognitive and quality of life benefits of radiosurgery vs WBRT specifically in SCLC brain metastases and promises to potentially challenge the standard of care.11

Limitations

The primary limitation of the present study is the inherent disadvantage of its retrospective design, although the incorporation of data from 10 international centers over nearly 30 yr helps to offset this impediment. With that said, the lack of availability of vital statistical databases for these patients likely resulted in an overestimation of the time to death following SRS, with the date of last contact serving as a surrogate for the date of death in 48 patients. Given the heterogeneity in source data, important factors such as performance status and extracranial disease control were not available, thus potentially biasing survival analyses by subgroups.19 Moreover, the identification of local failure may have been complicated by variability of definition and imaging technique across multiple institutions over the 30 yr of patient treatments. Although defined as tumor growth within the SRS target site, the potential presence of pseudoprogression prior to the ubiquitous use of MR perfusion techniques may have contributed to local failure, especially in the SRS salvage group following WBRT. Additionally, the rates of tumor control and survival are potentially limited by short follow-up due to competing risks of uncontrolled systemic disease, which accounts for the majority of deaths in this series. Incorporation of the competing risks analysis in determination of local failure and distant brain failure was an attempt to offset the most profound competing risk in the study of metastatic SCLC, that being death. Finally, the majority of patients in this study presented for SRS with 5 or fewer lesions (75%), potentially reducing applicability to those patients with greater than 5 SCLC brain metastases. Nevertheless, this study provides a large international analysis of SCLC patients treated with SRS, validating prior retrospective single-institutional series, and further suggesting that SRS may play an important role in selected patients with SCLC brain metastases, either in the upfront or salvage treatment setting.

CONCLUSION

SRS plays an important role in the management of brain metastases from SCLC, with the majority of that impact being within the scope of salvage therapy following WBRT. Ongoing trials and further analysis will better assess the value of radiosurgery in the primary management of SCLC brain metastases and, depending on the outcome of those trials, could potentially challenge the current standard application of WBRT as the standard of care in all patients with SCLC.

Disclosures

Dr Grills receives research funding from Elekta, which is unrelated to this study, and is a stockholder/serves on the Board of Directors of Greater Michigan Gamma Knife. Dr Liscak is a consultant for Elekta. Dr Kano has received a research grant from Elekta unrelated to this work. Dr Lunsford is a consultant and stockholder in Elekta. The other authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article. Dr Vargo has received a speaking honorarium from BrainLab. Dr Lunsford serves on the DSMB of Insightec Ltd.

Contributor Information

Christopher P Cifarelli, Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia; Department of Radiation Oncology, School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

John A Vargo, Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia; Department of Radiation Oncology, School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Wei Fang, West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute, School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Roman Liscak, Department of Stereotactic and Radiation Neurosurgery, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic.

Khumar Guseynova, Department of Stereotactic and Radiation Neurosurgery, Na Homolce Hospital, Prague, Czech Republic.

Ronald E Warnick, Mayfield Clinic, Jewish Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Cheng-chia Lee, Department of Neurosurgery, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Huai-che Yang, Department of Neurosurgery, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

Hamid Borghei-Razavi, Department of Neurosurgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Tonmoy Maiti, Department of Neurosurgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Zaid A Siddiqui, Department of Radiation Oncology, Beaumont Health System, Royal Oak, Michigan.

Justin C Yuan, Department of Radiation Oncology, Beaumont Health System, Royal Oak, Michigan.

Inga S Grills, Department of Radiation Oncology, Beaumont Health System, Royal Oak, Michigan.

David Mathieu, Division of Neurosurgery, Faculté de Médecine et des Sciences de la Santé, Université de Sherbrooke, Centre de Recherche du CHUS, Sherbrooke, Canada.

Charles J Touchette, Division of Neurosurgery, Faculté de Médecine et des Sciences de la Santé, Université de Sherbrooke, Centre de Recherche du CHUS, Sherbrooke, Canada.

Diogo Cordeiro, Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Veronica Chiang, Department of Neurosurgery, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; Department of Radiation Oncology, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Judith Hess, Department of Neurosurgery, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; Department of Radiation Oncology, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Christopher J Tien, Department of Neurosurgery, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut; Department of Radiation Oncology, Yale School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

Andrew Faramand, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Hideyuki Kano, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Gene H Barnett, Department of Neurosurgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio.

Jason P Sheehan, Department of Neurosurgery, School of Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

L Dade Lunsford, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Neurosurgery Speaks! Audio abstracts available for this article at www.neurosurgery-online.com.

COMMENT

The authors present an intriguing multi-institutional series on the usage of SRS for brain metastases from small cell lung cancer. Approximately 20% of the patients in this series were treated in the upfront setting without WBRT. Their outcomes appear acceptable. It may be time for the wider community in general to consider upfront SRS for this population, but several issues remain. First off, identifying the proper population for upfront SRS will be critical (single brain metastasis, <5 brain metastases, symptomatic brain metastases in the setting of urgent need for systemic therapy, etc)? It has been demonstrated in prior studies that patients with small cell lung cancer brain metastases have a higher brain metastasis velocity than other histologies. The question will be whether the omission of WBRT in these higher brain metastasis velocity patients affects outcomes such as overall survival, quality of life, neurologic death, and cost of care. As such, these questions may best be answered under the guidance of prospective clinical trials. However, the authors should be congratulated for posing the question to the larger community as to what should be the role of SRS in patients with small cell lung cancer brain metastases.

Michael D. Chan

Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Neurosurgery Speaks (Audio Abstracts)

Listen to audio translations of this paper's abstract into select languages by choosing from one of the selections below.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nugent JL, Bunn PA, Jr Matthews MJ et al. CNS metastases in small cell bronchogenic carcinoma: increasing frequency and changing pattern with lengthening survival. Cancer. 1979;44(5):1885-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takahashi T, Yamanaka T, Seto T et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation versus observation in patients with extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(5):663-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robin TP, Jones BL, Amini A et al. Radiosurgery alone is associated with favorable outcomes for brain metastases from small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2018;120:88-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wegner RE, Olson AC, Kondziolka D, Niranjan A, Lundsford LD, Flickinger JC. Stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases from small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):e21-e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yomo S, Hayashi M.. Is stereotactic radiosurgery a rational treatment option for brain metastases from small cell lung cancer? A retrospective analysis of 70 consecutive patients. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):95-015-1103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cordeiro D, Xu Z, Shepard M, Sheehan D, Li C, Sheehan J. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for brain metastases from small-cell lung cancer: Institutional experience over more than a decade and review of the literature. J Radiosurg SBRT. 2019;6(1):35-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL.. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Hoboken, N.J.: J. Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain. JAMA. 1998;280(17):1485-1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheehan J, Kondziolka D, Flickinger J, Lunsford LD. Radiosurgery for patients with recurrent small cell lung carcinoma metastatic to the brain: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(suppl):247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Serizawa T, Ono J, Iichi T et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for metastatic brain tumors from lung cancer: a comparison between small cell and non-small cell carcinoma. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(5 suppl):484-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernhardt D, Hommertgen A, Schmitt D et al. Whole brain radiation therapy alone versus radiosurgery for patients with 110 brain metastases from small cell lung cancer (ENCEPHALON Trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):388-018-2745-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wefel JS, Parsons MW, Gondi V, Brown PD. Neurocognitive aspects of brain metastasis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;149:155-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris S, Chan MD, Lovato JF et al. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery as salvage therapy after failure of whole-brain radiotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(1):e53-e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakazaki K, Higuchi Y, Nagano O, Serizawa T. Efficacy and limitations of salvage gamma knife radiosurgery for brain metastases of small-cell lung cancer after whole-brain radiotherapy. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155(1):107-114; discussion 113-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Postmus PE, Haaxma-Reiche H, Gregor A et al. Brain-only metastases of small cell lung cancer; efficacy of whole brain radiotherapy. An EORTC phase II study. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46(1):29-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carmichael J, Crane JM, Bunn PA, Glatstein E, Ihde DC. Results of therapeutic cranial irradiation in small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;14(3):455-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bernhardt D, Bozorgmehr F, Adeberg S et al. Outcome in patients with small cell lung cancer re-irradiated for brain metastases after prior prophylactic cranial irradiation. Lung Cancer. 2016;101:76-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sperduto PW, Chao ST, Sneed PK et al. Diagnosis-specific prognostic factors, indexes, and treatment outcomes for patients with newly diagnosed brain metastases: a multi-institutional analysis of 4,259 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(3):655-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernhardt D, Adeberg S, Bozorgmehr F et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in patients with brain metastases from small-cell lung cancer treated with whole brain radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2017;134(1):205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ward MC, Riaz N, Caudell JJ et al. Refining patient selection for reirradiation of head and neck squamous carcinoma in the IMRT Era: a multi-institution cohort study by the MIRI collaborative. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;100(3):586-594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Minniti G, Clarke E, Lanzetta G et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: analysis of outcome and risk of brain radionecrosis. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rae A, Gorovets D, Rava P et al. Management approach for recurrent brain metastases following upfront radiosurgery may affect risk of subsequent radiation necrosis. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2016;1(4):294-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sneed PK, Mendez J, Vemer-van den Hoek JG et al. Adverse radiation effect after stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: incidence, time course, and risk factors. J Neurosurg. 2015;123(2):373-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharma M, Jia X, Ahluwalia M et al. First follow-up radiographic response is one of the predictors of local tumor progression and radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases. Cancer Med. 2017;6(9):2076-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L et al. Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol 90-05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(2):291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nong J, Gong Y, Guan Y et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis depicts subclonal architecture and genomic evolution of small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang M, Topaloglu U, Petty WJ et al. Circulating mutational portrait of cancer: manifestation of aggressive clonal events in both early and late stages. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arriagada R, Le Chevalier T, Borie F et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(3):183-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giuliani M, Sun A, Bezjak A et al. Utilization of prophylactic cranial irradiation in patients with limited stage small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5694-5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guo WL, He ZY, Chen Y et al. Clinical features of brain metastases in small cell lung cancer: an implication for hippocampal sparing whole brain radiation therapy. Transl Oncol. 2017;10(1):54-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoyama H, Shirato H, Tago M et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery plus whole-brain radiation therapy vs stereotactic radiosurgery alone for treatment of brain metastases: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2483-2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chang EL, Wefel JS, Hess KR et al. Neurocognition in patients with brain metastases treated with radiosurgery or radiosurgery plus whole-brain irradiation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1037-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kocher M, Soffietti R, Abacioglu U et al. Adjuvant whole-brain radiotherapy versus observation after radiosurgery or surgical resection of one to three cerebral metastases: results of the EORTC 22952–26001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(2):134-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown PD, Jaeckle K, Ballman KV et al. Effect of radiosurgery alone vs radiosurgery with whole brain radiation therapy on cognitive function in patients with 1 to 3 brain metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(4):401-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]