Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to assess the clinical pattern and predictors of stroke treatment outcomes among hospitalised patients in Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialised hospital (FHCSH) in northwest Ethiopia.

Design

A retrospective cross-sectional study.

Setting

The study was conducted medical ward of FHCSH.

Participants

The medical records of 597 adult patients who had a stroke were included in the study. All adult (≥18 years) patients who had a stroke had been admitted to the medical ward of FHSCH during 2015–2019 were included in the study. However, patients with incomplete medical records (ie, incomplete treatment regimen and the status of the patients after treatment) were excluded in the study.

Results

In the present study, 317 (53.1%) were males, and the mean age of the study participants was 61.08±13.76 years. About two-thirds of patients (392, 65.7%) were diagnosed with ischaemic stroke. Regarding clinical pattern, about 203 (34.0%) of patients complained of right-side body weakness and the major comorbid condition identified was hypertension (216, 64.9%). Overall, 276 (46.2%) of them had poor treatment outcomes, and 101 (16.9%) of them died. Patients who cannot read and write (AOR=42.89, 95% CI 13.23 to 111.28, p<0.001), attend primary school (AOR=22.11, 95% CI 6.98 to 55.99, p<0.001) and secondary school (AOR=4.20, 95% CI 1.42 to 12.51, p<0.001), diagnosed with haemorrhagic stroke (AOR=2.68, 95% CI 1.62 to 4.43, p<0.001) and delayed hospital arrival more than 24 hours (AOR=2.92, 95% CI 1.83 to 4.66, p=0.001) were the independent predictors of poor treatment outcome.

Conclusions

Approximately half of the patients who had a stroke had poor treatment outcomes. Ischaemic stroke was the most predominantly diagnosed stroke type. Education status, types of stroke and the median time from onset of symptoms to hospitalisation were the predictors of treatment outcome. Health education should be given to patients regarding clinical symptoms of stroke. In addition, local healthcare providers need to consider the above risk factors while managing stroke.

Keywords: NEUROLOGY, Stroke, Stroke medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study has provided a real insight into the current treatment outcome and clinical pattern among hospitalised stroke patients in northwest Ethiopia.

The study was conducted with a larger sample size, which can enhance the generalisability of the findings.

Due to the retrospective nature, the data obtained might be affected by the documentation culture of the hospital and the healthcare providers.

The study was done in a single setting, which may affect the generalisability of the data to the entire population.

A prospective study in a multicentre setting would be better to accurately describe the clinical pattern and treatment outcome of stroke in Ethiopia.

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in low/middle-income and developed countries in the 21st century. Despite geographical variation in the lifetime risk of stroke, one in four persons whose age is 25 years and above develops stroke during their lifetime.1 Currently, central nervous system infarction is defined as the brain, spinal cord or retinal cell death attributable to ischaemia in a specified vascular territory, based on neuropathological, neuroimaging and clinical evidence of ischaemic injury with symptoms persisting lasting 24 hours or longer after exclusion of other aetiologies.2 3 It is associated with severe medical conditions with high complications caused by reduced blood flow to the brain.4 5 According to the 2016 report of the WHO and The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study, there were 33 million people with stroke with an incidence of 15 million and 5 million stroke deaths and 116.4 million disability-adjusted life-years.6 7 The stroke burden will be doubled if the trend continues by the year 2030.8 According to the American Heart Association report, stroke can be classified into either ischaemic due to blood clot in the artery that supplies the brain or haemorrhagic due to intracranial bleeding.9 10 Various studies showed that ischaemic stroke (52.5%–87%) is the most frequently diagnosed type of stroke compared with haemorrhagic stroke.11 12 Ischaemic stroke is significantly less fatal than a haemorrhagic type of stroke, with 30-day case-fatality rates of 46.5% for haemorrhagic stroke compared with 9%–23% in ischaemic stroke.10 Worldwide, it is the second-leading cause of mortality, accounting for 10% of all deaths and killing 5.5 million people each year.4 13 14

In western countries, stroke is the third most common cause of morbidity and mortality next to cancer and coronary artery disease, with mortality rates of 17%–34% in the first month of poststroke days and 25%–40% in the first 12 months.15 16 Despite a 35% reduction in stroke mortality between 2001 and 2011, a stroke occurred in the USA at a rate of almost 800 000 per year and resulted in 128 932 deaths in 2011.17 In low/middle-income countries, the incidence of stroke is rapidly increasing due to the high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, smoking and other non-communicable diseases,9 18 19 and 86% of all stroke associated deaths globally were occurred in low-income and middle-income countries.20 In Africa, the incidence of stroke-related morbidity and mortality is increasing due to the high prevalence of various risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, older age and alcohol.4 16 21–24

A recent community survey undertaken in African countries showed stroke prevalence was between 200 and 300 per 100 000 populations,25 and its prevalence is increasing compared with the previous African stroke report (58–68 per 100 000).26 In sub-Sahara African countries, the estimated lifetime risk of developing stroke was 11.8%.27 Further, despite comprehensive data regarding stroke burden in Ethiopia are scarce, observational studies showed that it is one of the most common reasons for hospital admission,11 28 and its incidence is increasing annually.29

As per the WHO stroke mortality report, stroke mortality was estimated to be 122–153.8 per 100 000 people in Ethiopia.30 Patients usually present late, and the standard of care is poor compared with developed countries; hence, rate of mortality is expected to be higher. However, data are scarce on clinical pattern and treatment outcome among patients who had a stroke in northwest Ethiopia. Therefore, it is imperative that a lot has to be done to address the burden of stroke, risk factors and mortality in Ethiopia.5 24 Hence, the present study was aimed to assess the clinical pattern and predictors of stroke treatment outcomes among hospitalised patients who had a stroke at the medical ward of FHSCH.

Methods

Study design and period

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at FHSCH, Bahir Dar town, located 665 km from the northwest of Addis Ababa. The hospital provides different clinical services for 12 million population in the catchment area. It serves as a referral centre for surrounding primary and general hospitals as well as a teaching hospital for Bahir Dar University. The data were collected from January to February 2020.

Eligibility criteria

All adult (≥18 years) patients who had a stroke diagnosed to had stroke by MRI or clinically and admitted to the medical ward of FHSCH during 2015–2019 were included in the study. However, patients with incomplete medical records (ie, incomplete treatment regimen and treatment outcome) were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling techniques

All medical records of adult patients who had a stroke who had been treated at FHSCH during 2015–2019 were eligible to the study. Based on the above eligibility criteria, 597 medial records with a confirmed stroke diagnosis (with an MRI or clinically) were included in the study. Since all eligible medical records of stroke patients were involved in the study, a consecutive sampling technique was employed.

Data collection instrument and procedure

Data abstraction format was adapted from various relevant literature and further modified based on the pretest result, undertaken in 5% of hospitalised stroke patients’ medical cards. The format contained sociodemographic patient characteristics, clinically related information, previous, current and discharge medications used, comorbidities, complications, time from onset of symptoms to hospitalisation, length of hospital stay, type of stroke and treatment outcome status. These data were collected from the patients’ medical records. Six trained clinical pharmacists participated for the data collection.

Study variables

The treatment outcome was the outcome variable of the study, which could be influenced by the following independent variables. These are: age, sex, occupational status, types of stroke, length of hospital stay, the median time from onset of symptom to hospitalisation and comorbidity status were the main independent variables of the study.

Data analysis

The collected data were entered and analysed using SPSS V.25.0 statistical software. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency, percentage and mean with SD, were used to describe the independent variables. Multiple stepwise backward logistic regression analysis was done for a p<0.25 to identify the independent predictors of treatment outcome. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design and conduction of this study. In addition, they were not invited to comment on the study design and consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Further, they were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Operational definition

Undetermined type of stroke

A type of stroke neither ischaemic nor haemorrhagic, not clearly identified.

Improved or good treatment outcome

If the patient is discharged without complication or if patient discharge with improvement.

Poor treatment outcome

If the patient is discharged with complication, or referred to higher health facility, or left against medical advice or death.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients

In the present study, a total of 597 stroke patients’ medical record were reviewed. Males were accounted for 317 (53.1%). The mean age of the study participants was 61.08±13.76, with the age range of 25–98 years. Approximately, 252 (42.2%) patients were in the age range of 56–70 years. In addition, 191 (33.0%) and 152 (25.5%) patients attended primary and higher education, respectively. Regarding occupation, the majority (225, 37.7%) of them were farmers (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients who had a stroke hospitalised at Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialised hospital, northwest Ethiopia

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (%) | |||

| Ischaemic stroke | Haemorrhagic stroke | Undetermined | Total | ||

| Sex | Male | 217 (55.4) | 89 (47.3) | 11 (64.7) | 317 (53.1) |

| Female | 175 (44.6) | 99 (52.7) | 6 (35.3) | 280 (46.9) | |

| Age | <40 | 20 (5.1) | 27 (14.4) | 2 (11.8) | 49 (8.2) |

| 41–55 | 100 (25.5) | 44 (23.4) | 2 (11.8) | 146 (24.5) | |

| 56–70 | 168 (42.9) | 81 (43.1) | 3 (17.6) | 252 (42.2) | |

| >70 | 104 (26.5) | 36 (19.1) | 10 (58.8) | 150 (25.1) | |

| Occupation | Farmer | 150 (38.3) | 67 (35.6) | 8 (47.1) | 225 (37.7) |

| Employed | 76 (19.4) | 35 (18.6) | 2 (11.8) | 113 (18.9) | |

| Unemployed | 34 (8.7) | 20 (10.6) | 1 (5.9) | 55 (9.2) | |

| Housewife | 85 (21.7) | 58 (30.9) | 4 (23.5) | 147 (24.6) | |

| Retired | 47 (12) | 8 (4.3) | 2 (11.8) | 57 (9.5) | |

| Educational status | Cannot read and write | 93 (23.7) | 53 (28.2) | 6 (35.3) | 152 (25.5) |

| Primary | 70 (17.9) | 44 (23.4) | 3 (17.6) | 117 (19.6) | |

| Secondary | 92 (23.5) | 42 (22.3) | 3 (17.6) | 137 (22.9) | |

| Higher education | 137 (34.9) | 49 (26.1) | 5 (29.4) | 191 (32.0) | |

| Residence | Urban | 206 (52.6) | 65 (34.6) | 7 (41.2) | 278 (46.6) |

| Rural | 186 (7.4) | 123 (5.4) | 10 (58.8) | 319 (53.4) | |

Clinical characteristics of patients who had a stroke

About two-thirds of the patients (392, 65.7%) were diagnosed with ischaemic stroke, while 188 (31.5%) had a haemorrhagic stroke. The mean time from the onset of symptoms until arrival at the hospital was 23.67 hours. In addition, the median length of hospital stay was 5.55±3.29 days, and more than half of the patients (345, 57.8%) remained in the hospital for five or fewer days.

Approximately, one-third of patients who had a stroke complained right-sided body weakness (203, 34.0%), followed by left side body weakness (194, 32.5%). Moreover, more than half of them (333, 55.8%) had at least one comorbid condition, of which the most common comorbid conditions was hypertension (219, 64.9%), atrial fibrillation (114, 34.2%) and diabetes mellitus (83, 24.9%).

Hypertension was primarily prevalent in haemorrhagic stroke (158, 84 %) compared with patients with ischaemic stroke (175, 44.6%). The most common complications of stroke were aspiration pneumonia (125, 64.4%) and elevated intracranial pressure (57, 29.4%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients who had a stroke hospitalised at Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialised hospital, northwest Ethiopia, 2020

| Variables | Category | Frequency (%) |

| Clinical presentation | Right side body weakness | 203 (34.0) |

| Left side body weakness | 194 (32.5) | |

| Loss of consciousness | 103 (17.3) | |

| Aphasia | 97 (16.2) | |

| Types of stroke | Ischaemic stroke | 392 (65.7) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 188 (31.5) | |

| Undetermined | 17 (2.8) | |

| Comorbid status | Absent | 264 (44.2) |

| Present | 333 (55.8) | |

| Specific comorbid conditions | Hypertension | 216 (64.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 114 (34.2) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 83 (24.9) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 37 (11.1) | |

| Epilepsy | 33 (9.9) | |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 22 (6.6) | |

| Others* | 31 (9.3) | |

| Complication status | Absent | 403 (67.5) |

| Present | 194 (32.5) | |

| Specific complications | Aspiration pneumonia | 125 (64.4) |

| Increased ICP | 57 (29.4) | |

| Septic shock | 29 (14.9) | |

| Bed sore | 23 (11.9) | |

| Others* | 17 (8.8) | |

| Time from onset to hospitalisation | <12 hours | 117 (19.6) |

| 12–24 hours | 204 (34.2) | |

| 25–48 hours | 130 (21.8) | |

| >48 hours | 146 (24.5) | |

| Length of hospital stay | ≤5 days | 345 (57.8) |

| >5 days | 252 (42.2) | |

| Mean day | 5.55±3.29 days |

(Urinary tract infection, HIV/AIDs, lipoma, asthma, glaucoma, breast cancer).

*(Seizure, acute renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, hypokalaemia, eclampsia).

ICP, intracranial pressure.

Management pattern of patients who had a stroke

About half of patients with stroke (333, 55.8%) had a history of medication. During admission, 12.2% and 9.0% of patients were used enalapril and nifedipine, respectively. In addition, 352 (59%) stroke patients used combinations of acetylsalicylic acid and atorvastatin, while 103 (17.3%) patients received support/physiotherapy during hospitalisation. Cimetidine (154, 25.8%) and a combination of metronidazole, ceftriaxone and cimetidine 110 (18.4%) were the major concomitantly administered medications. Besides, acetylsalicylic acid 321 (53.8%), and acetylsalicylic acid and atorvastatin combination (97, 16.2%) were the frequent discharge medications, while nifedipine (147, 24.6%) was the most commonly concomitantly prescribed drug on discharge. Further, 227 (38.0%) patients who had a stroke were prescribed non-fractionated heparin for the prevention of deep venous thrombosis during hospitalisation (table 3).

Table 3.

Management pattern among patients who had a stroke hospitalised at Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialised hospital, northwest Ethiopia

| Management practice | Categories | Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) |

| Medication history | Enalapril | 73 | 12.2 |

| Oral hypoglycaemic | 45 | 7.5 | |

| Nifedipine | 54 | 9.0 | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 38 | 6.4 | |

| Nifedipine+hydrochlorothiazide | 32 | 5.4 | |

| Atorvastatin | 27 | 4.5 | |

| Phenytoin | 24 | 4.0 | |

| Insulin | 15 | 2.5 | |

| Others* | 25 | 4.2 | |

| None | 264 | 44.2 | |

| Medications used to treat stroke during hospitalisation | ASA+atorvastatin | 352 | 59.0 |

| Supportive therapy/physiotherapy | 103 | 17.3 | |

| ASA | 54 | 9.0 | |

| Atorvastatin | 52 | 8.7 | |

| ASA+atorvastatin+physiotherapy | 36 | 6.0 | |

| Concomitantly administered drugs for hospitalised patients who had a stroke | Cimetidine | 154 | 25.8 |

| Ceftriaxone+metronidazole+cimetidine | 110 | 18.4 | |

| Heparin | 71 | 11.9 | |

| Ceftriaxone+metronidazole | 52 | 8.7 | |

| Mannitol | 52 | 8.7 | |

| Bisacodyl | 43 | 7.2 | |

| Metoprolol | 34 | 5.7 | |

| Warfarin | 30 | 5.0 | |

| Mannitol+ranitidine | 32 | 5.4 | |

| Ceftriaxone+cimetidine | 19 | 3.2 | |

| Medications give at discharge for treatment of stroke | ASA | 321 | 53.8 |

| ASA+atorvastatin | 97 | 16.2 | |

| Atorvastatin | 78 | 13.1 | |

| Concurrently prescribed drug prescribed during discharge | Nifedipine | 147 | 24.6 |

| Metoprolol | 91 | 15.2 | |

| Ranitidine | 89 | 14.9 | |

| Enalapril | 82 | 13.7 | |

| Omeprazole | 41 | 6.9 | |

| Phenytoin | 28 | 4.7 | |

| Digoxin | 18 | 3.0 |

*HAART, salbutamol, antibiotics and anticancer.

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin); HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Treatment outcome and associated factors

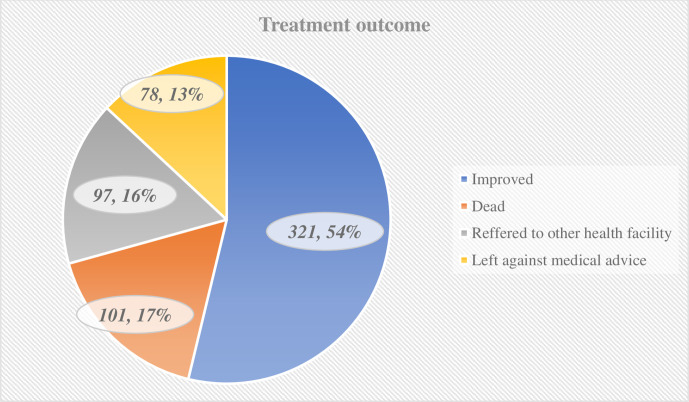

As shown in figure 1, more than half of the patients who had a stroke (321, 53.8%) were discharged with good treatment outcome. Contrastingly, poor treatment outcome was observed in 276 (46.2%) patients. Of patients with poor treatment outcome, 16.9% were died.

Figure 1.

Distribution of patients with stroke by their outcomes.

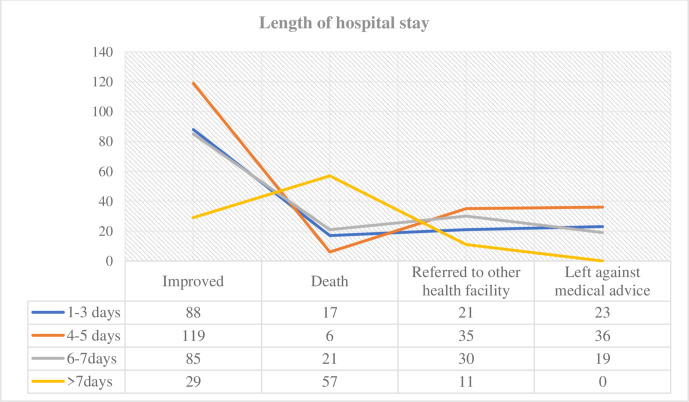

More than half (57, 56.4%) of patients who died stayed more than 7 days in the hospital. One hundred and nineteen (30.1%), 36 (46.2%) and 36 (36.1%) good treatment outcome were left with medical advice and referred to other health facility and stayed 4–5 days in the hospital, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of patient outcomes by duration of hospital stay.

The present study showed that the majority of patients (63, 62.4%) with a haemorrhagic stroke had fatal outcomes. On the other hand, more patients with ischaemic stroke have been improved, referred to other healthcare facilities, and left to medical advice than patients with haemorrhagic stroke (table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of ‘patients’ outcomes by stroke types

| Patient outcomes | Types of stroke | Total, % |

||

| Ischaemic stroke, % | Haemorrhagic stroke, % | Undetermined, % | ||

| Improved | 238 (74.1) | 74 (23.1) | 9 (3.8) | 321 (53.8) |

| Referred to other health facility | 65 (67) | 31 (32) | 1 (1) | 97 (16.2) |

| Left against medical advice on self and family requests | 57 (73.1) | 20 (25.6) | 1 (1.3) | 78 (13.1) |

| Death | 32 (31.7) | 63 (62.4) | 6 (5.9) | 101 (16.9) |

| Total | 392 (65.7) | 188 (31.5) | 17 (2.8) | 597 (100) |

The multivariate logistic regression model showed that educational status, types of stroke, and time from onset of symptoms to hospitalisation were significant predictors of stroke treatment outcome.

Accordingly, patients who cannot read and write, attend primary and secondary school were about 43 (AOR=42.89, 95% CI 13.23 to 111.28, p<0.001), 22 (AOR=22.11, 95% CI 6.98 to 55.99, p<0.001) and 4 (AOR=4.20, 95% CI 1.42 to 12.51, p<0.001) times more likely to have a risk of poor treatment outcome, respectively. Besides, patients diagnosed with a haemorrhagic type of stroke were three (AOR=2.68, 95% CI 1.62 to 4.43, p<0.001) times more likely to have poor treatment outcomes than ischaemic stroke patients. Further, patients with time from symptom onset to hospitalisation greater than 24 hours were three (AOR=2.92, 95% CI 1.83 to 4.66, p=0.001) times more likely to have poor treatment outcomes as compared with their counterparts (table 5).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analysis of predictors of treatment outcome

| Variables | Categories | Treatment outcome | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Good | Poor | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Sex | Male | 162 | 155 | 1 | 1 | |

| Female | 159 | 121 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.01)* | 0.86 (0.42 to 1.75) | 0.679 | |

| Age | <40 | 12 | 37 | 1.73 (0.84 to 3.60)* | 2.23 (0.79 to 6.31) | 0.130 |

| 41–55 | 98 | 48 | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.45)* | 0.53 (0.16 to 0.69) | 0.071 | |

| 57–70 | 157 | 95 | 0.34 (0.22 to 0.52)* | 0.31 (0.16 to 0.61) | 0.068 | |

| >70 | 54 | 96 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational status | Cannot read and write | 30 | 122 | 36.81 (19.81 to 68.42)* | 42.89 (13.23 to 111.28) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 33 | 84 | 23.04 (12.37 to 42.91)* | 22.11 (6.98 to 55.99) | <0.001 | |

| Secondary | 86 | 55 | 5.37 (2.99 to 9.66)* | 4.20 (1.42 to 12.51) | <0.001 | |

| Higher education | 172 | 19 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Occupation | Farmer | 82 | 143 | 4.88 (2.55 to 9.35)* | 0.52 (0.14 to 1.94) | 0.330 |

| Employed | 102 | 11 | 0.30 (0.13 to 0.71)* | 0.85 (0.27 to 2.72) | 0.789 | |

| Unemployed | 30 | 25 | 2.33 (1.06 to 5.16)* | 0.56 (0.14 to 2.28) | 0.417 | |

| House wife | 65 | 82 | 3.53 (1.80 to 6.93)* | 0.55 (0.14 to 2.06) | 0.362 | |

| Retired | 42 | 15 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Types of stroke | Ischaemic stroke | 238 | 154 | 1 | 1 | |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 74 | 114 | 2.38 (1.67 to 3.40)* | 2.68 (1.62 to 4.43) | <0.001 | |

| Undetermined | 9 | 8 | 1.37 (0.52 to 3.64) | 0.35 (0.09 to 1.43) | 0.143 | |

| Length of hospital stay | ≤5 days | 207 | 138 | 1 | 1 | |

| >5 days | 114 | 138 | 1.82 (1.31 to 2.52)* | 1.70 (1.04 to 2.79) | 0.056 | |

| Median time from onset of symptom to hospitalisation | <24 hours | 207 | 114 | 1 | 1 | |

| >24 hours | 114 | 162 | 2.58 (1.85 to 3.59)* | 2.92 (1.83 to 4.66) | 0.001 | |

| Comorbidity status | Absence | 166 | 178 | 1 | 1 | |

| Present | 155 | 175 | 1.95 (1.40 to 2.71)* | 1.38 (0.85 to 2.22) | 0.192 | |

*Shows statistically significant at p<0.25 during univariate analysis.

AOR, adjusted OR; COR, crudes OR.

Discussion

A 5-year retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted to describe the clinical patterns and treatment outcome of patients with stroke admitted to the medical ward of FHSCH. The mean age of patients in this study was 63.2±12.6 years, which is consistent with other previous hospital-based studies in Ethiopia where the mean age of patients who had a stroke ranged from 56 to 66 years.11 12 22 The existence of multiple comorbidities such as hypertension, heart disease and diabetes may be due to the high prevalence of stroke in the elderly. This is, however, lower than studies carried out in Iran16 and USA31 and higher than other studies conducted in Ethiopia,28 30 32 Sri Lanka32 and India.33 This disparity may be due to differences in sociodemographic factors, sample size and the method used in the studies. The prevalence of stroke in males was significantly higher than in females that are consistent with other cross-sectional studies in Ethiopia,12 22 34 Nigeria,35 36 Kenya,19 Zambia,37 India,33 38 Iran16 and Sri Lanka.32 The high prevalence of stroke in males may be attributed to the increased habit of drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes. Other studies performed by Shenkutie Greffie et al and Connor et al25 39 showed that stroke is mainly diagnosed in females. This might be explained by the presence of different risk factors such as pregnancy-related disorders and the frequent use of contraceptives in females in those studies.

The finding of this study also revealed that ischaemic stroke was predominant (65.7%). Previously related research found more prevalence of ischaemic stroke as opposed to haemorrhagic stroke.9 11 22 32 39 40 Contrastingly, haemorrhagic stroke was predominant in studies conducted at St. Paul’s Teaching Hospital (61.3%),41 Jimma (64.3%)42 and Rwanda (65%).43 This disparity could probably due to the difference in pattern of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, especially cardiovascular risk factors in St. Paul’s Teaching Hospital, Jimma and Rwanda. Moreover, 55.8% of the study participants had one or more comorbid conditions, of which, hypertension was the most prevalent comorbid disease. This is consistent with other studies in Ethiopia,24 41 44 Tanzania and Sri Lanka,32 45 which reported that hypertension was the most common comorbid condition in patients with stroke. Furthermore, research performed by Fekadu et al,12 Gebremariam and Yang22 and Rymer46 showed that high blood pressure and ageing blood vessels constituted a major risk factor for stroke development. The likely explanation for the high prevalence of hypertension could be poor lifestyle and public awareness and inaccessible health facilities in low/middle-income countries. This study showed that almost one-third of the patients who had a stroke complained right-sided body weakness. Previous studies in Ethiopia and Gambia have also shown that left side body weakness is the most frequently reported clinical presentation.12 18 On the other hand, studies conducted by Shenkutie Greffie et al,39 Gedefa et al,41 Masood et al47 and Patne and Chintale38 reported that patients with stroke had motor-related symptom and focal neurological deficit. This disparity probably could be due to different site of infarction.

In FHSCH, enalapril, nifedipine and hydrochlorothiazide were the most frequently used past medication before patients admitted to the hospital. This finding is in line with various studies conducted on the management of hypertension with stroke.12

ACE inhibitor and diuretics are widely used for the treatment of high blood pressure, which is the major modifiable risk factor for stroke. Reducing blood pressure, therefore, improves outcomes for patients with stroke. Various epidemiological studies done by Lawes et al,48 Elliott,49 Beckett et al50 revealed that screening and lowering of both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure was the most effective goal for reducing cardiovascular disease and for preventing recurrence and stroke mortality. In our setting, the mean length of hospitalisation was found to be 5.6 days, which is comparable with other studies conducted by Temesgen et al (6.7 days)11 and Desita and Zewdu (6 days).34 Conversely, the mean length of hospital stay at FHSCH was shorter than the studies performed by Gedefa et al,41 Gebreyohannes et al,51 de Carvalho et al52 and Walker et al,45 which were 11.14, 11.55, 15.4 and 19 days, respectively.

In this study setting, a significant proportion of stroke patients were died, referred to other health facilities and discharged left against medical advice on self and family requests rapidly. These disparities could be explained in various ways, such as availability of rehabilitation centres and other referral sites, treatment set up, costs for medication and beds, and quality of healthcare. In terms of management pattern, the combinations of acetylsalicylic acid and atorvastatin (65%) were used primarily in the cc stroke care in the study setting during hospitalisation. This finding is in agreement with previous studies, which indicated that antiplatelet and dyslipidaemias medications were frequently prescribed.11 16 53 The frequent usage might be due to the superior pharmacological effects of statins in reducing cardiovascular risks relative to other lipid-lowering agents, and antiplatelet is the most well-studied medications for the treatment of ischaemic stroke.11 54 However, this result contrasts with numerous studies performed by Bernheisel et al55 and Adams et al,56 which stated that tissue plasminogen activator intravenous injection was primarily used in ischaemic stroke treatment. This will possibly be attributed to the financial constraints and inaccessibility of tissue plasminogen activator in the study setting.

Although the effectiveness of mannitol in haemorrhagic stroke needs further investigations, 44.7% of haemorrhagic stroke patients used mannitol to reduce cerebral oedema. In 44.7% of haemorrhagic stroke patients, mannitol was used to reduce cerebral oedema. This is inline with different clinical trials done by Wang et al57 and Aminmansour et al58 which reported that the initial use of mannitol at early stage seemed safe but might not reduce haemorrhage size. Cimetidine alone and the combinations of ceftriaxone, metronidazole and cimetidine were the most widely used medications in the treatment of hospital-acquired infections and the prevention of stress-induced ulcer during hospitalisation.

Regarding the treatment outcome of stroke patients, the mortality rate was 16.9%. The rate is relatively higher than studies by Gebremariam et al,22 Kassaw,44 Shenkutie Greffie et al,39 Temesgen et al,11 Gebremariam and Yang22 and de Carvalho et al.52 However, it is lower compared with studies conducted at St. Paul’sTeaching Hospital (30.1%)41 and Jimma University Hospital (37.87%).42 This disparity could be due to the different rate of haemorrhagic stroke condition, treatment pattern and comorbid conditions. In general, in our study, 53.8% of stroke patients had good outcomes while 46.2% had poor outcome (left with complication and died). The finding is in line with previous studies, where 54.8% and 59.2% of stroke patients had good outcome.11 41

Although respiratory failure secondary to aspiration pneumonia has not been significantly associated with treatment outcomes, it was a frequent contributor to death in our study setting. It is consistent with other hospital-based studies conducted at Gondar University Teaching Hospital22 and China.53 Contrastingly, a study conducted in Rwanda found that initial presentation with severe stroke was the leading cause of death among patients with stroke.43

The binary logistic regression model analysis found that the treatment outcome was significantly associated with educational status, the time from the onset of symptoms to hospitalisation, and types of stroke. This contrasts with the study in the Shashemene Referral Hospital, which showed that none of the independent variables was significantly associated with the outcome.11 This variation may be attributed to the small sample size (73 patients with stroke) in that study. The current research found that stroke patients with a high educational level have a better treatment outcome than patients with a low educational level. This result is similar to other previous research carried out at Nekemte Referral Hospital, which found that study participants with higher educational levels have better treatment outcomes.12 Educated participants may likely have improved access to information about their health status, better economic situation, better awareness about detecting and managing risk factors of stroke, and higher capacity to evaluate stressful events. Stroke patients with a low level of education are often believed to disregard self-management behaviour and adherence to their medications. Consequently, the low educational status can contribute to the poor outcome of patients who had a stroke.

The study showed that the meantime, from the onset of symptoms to hospitalisation, was found to be 23.67 hours. This is in line with other studies conducted by Temesgen et al (23.5 hours)11 and Fekadu et al (24 hours).12 Contrary to this finding, it was shorter than the studies conducted by Sagui et al (48 hours)59 and Gebreyohannes et al (69.42 hours).51 In contrast, it was delayed compared with other studies conducted by He et al (8 hours)53 and de Carvalho et al (12.9 hours).52 The difference might be due to the availability of transportation and nearby health facilities and knowledge of the patient for the clinical presentations of stroke. Patients who were delayed to come to the hospital had a poor treatment outcome compared with their counterparts. This finding is inconsistent with previous studies in Africa.22 36 60 It is advisable that hospital arrival within 3 hours of symptom onset to receive thrombolytic medications such as tissue plasminogen activator, to prevent disabilities and mortality from stroke.31 Delayed hospital admission creates difficulties in managing stroke and preventing complications in low/middle-income countries, including Ethiopia since early hours are crucial to delaying poor prognosis. Due to this reason, the majority of patients who had a stroke in this study were not candidates for tissue plasminogen activators. Moreover, patients diagnosed with haemorrhagic stroke (AOR=2,68, 95% CI 1.62 to 4.43, p<0001) were found to have poor treatment outcome relative to ischaemic stroke. This is in line with study done in Ethiopia and other African countries, which revealed haemorrhagic stroke was significantly more lethal than ischaemic stroke.19 35 39 61 62

Even though the presence of comorbid conditions and the development of complications were found to be significantly associated with poor treatment outcome in another study,12 our study did not show this finding. The difference could be attributed to the difference pattern of comorbid conditions.

Conclusion and recommendations

Approximately half of the patients who had a stroke had poor treatment outcome. The most common stroke type was ischaemic stroke. In addition, more than half of the patients had comorbid hypertension condition. During hospitalisation, acetylsalicylic acid and atorvastatin combination agents were commonly used in stroke treatment. Further, education status, types of stroke and the time from the onset of symptoms to admission were predictors of treatment outcome. Early identification of stroke type, risk factors and increasing patient awareness about stroke symptoms are vital to overcome stroke complications and mortality. Therefore, comprehensive health education on stroke should be given to the general public and specifically to stroke patients, while local healthcare providers should consider the above risk factors while managing patients who had a stroke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge FHSCH medical ward staffs and data abstractors for their valuable contribution towards this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: BK contributed in developing the idea, design of the study, statistical analysis and interpretation of the data and write up the proposal and manuscript. AE and MM were involved in proposal development, design of the study and manuscript writing. AD and GTT contributed to the design of the study and edition of the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript critically.

Funding: This work was supported by Debre Tabor University (grant no. DTU/RE/1/170/2012).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethical review board of Debre Tabor University, College of Health Sciences (Ref. No: DTU/RE/1/170/12). In addition, patient consent was waived by the Ethics Committee since the data was collected from medical records retrospectively. Patients' personnel information and clinical information were recorded by ensuring patient confidentiality. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.The GBD 2016 Lifetime Risk of Stroke Collaborators Global, regional, and country-specific lifetime risks of stroke, 1990 and 2016. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2018;379:2429–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feigin VL, Norrving B, Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res 2017;120:439–48. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke 2013;44:2064–89. 10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin VL, Krishnamurthi R, Bhattacharjee R, et al. New strategy to reduce the global burden of stroke. Stroke 2015;46:1740–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fekadu G, Chelkeba L, Kebede A. Burden, clinical outcomes and predictors of time to in hospital mortality among adult patients admitted to stroke unit of Jimma University medical center: a prospective cohort study. BMC Neurol 2019;19:213. 10.1186/s12883-019-1439-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katan M, Luft A. Global burden of stroke. seminars in neurology. Thieme Medical Publishers, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, et al. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:913–24. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet 2012;380:2197–223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulat B, Mohammed J, Yeseni M. Magnitude of stroke and associated factors among patients who attended the medical ward of Felege Hiwot referral Hospital, Bahir Dar town, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 2016;30:129–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godoy DA, Piñero GR, Koller P, et al. Steps to consider in the approach and management of critically ill patient with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. World J Crit Care Med 2015;4:213. 10.5492/wjccm.v4.i3.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temesgen TG, Teshome B, Njogu P. Treatment outcomes and associated factors among hospitalized stroke patients at Shashemene referral Hospital, Ethiopia. 2018 Stroke research and treatment, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fekadu G, Adola B, Mosisa G, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes among stroke patients hospitalized to Nekemte referral Hospital, Western Ethiopia. J Clin Neurosci 2020;71:170–6. 10.1016/j.jocn.2019.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkowitz AL. Stroke and the noncommunicable diseases: a global burden in need of global advocacy. Neurology 2015;84:2183–4. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Zhou L, Zhang Y, et al. Risk factors of stroke in Western and Asian countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2014;14:776. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feigin VL, Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, et al. Stroke epidemiology: a review of population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, and case-fatality in the late 20th century. Lancet Neurol 2003;2:43–53. 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00266-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbasi V, Amani F, Aslanian R. Epidemiological study of stroke in Ardabil, Iran: a hospital Based-Study. J Neurol Disord Stroke 2017;5:1128. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation 2016;133:e38. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbusinski JM, van der Sande MAB, Bartholome EJ, et al. Stroke presentation and outcome in developing countries: a prospective study in the Gambia. Stroke 2005;36:1388–93. 10.1161/01.STR.0000170717.91591.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jowi JO, Mativo PM. Pathological sub-types, risk factors and outcome of stroke at the Nairobi Hospital, Kenya. East Afr Med J 2008;85:572-81. 10.4314/eamj.v85i12.43535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owolabi MO, Akarolo-Anthony S, Akinyemi R, et al. The burden of stroke in Africa: a glance at the present and a glimpse into the future. Cardiovasc J Afr 2015;26:S27–38. 10.5830/CVJA-2015-038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al Khathaami AM, Al Bdah B, Alnosair A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of younger adults with embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS): a retrospective study. Stroke Res Treat 2019;2019:1–6. 10.1155/2019/4360787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebremariam SA, Yang HS. Types, risk profiles, and outcomes of stroke patients in a tertiary teaching hospital in northern Ethiopia. eNeurologicalSci 2016;3:41–7. 10.1016/j.ensci.2016.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karthik L, Kumar G, Keswani T, et al. Protease inhibitors from marine actinobacteria as a potential source for antimalarial compound. PLoS One 2014;9:e90972. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fekadu G, Chelkeba L, Kebede A. Risk factors, clinical presentations and predictors of stroke among adult patients admitted to stroke unit of Jimma University medical center, South West Ethiopia: prospective observational study. BMC neurology 2019;19:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connor MD, Thorogood M, Casserly B, et al. Prevalence of stroke survivors in rural South Africa: results from the southern Africa stroke prevention initiative (SASPI) Agincourt field site. Stroke 2004;35:627–32. 10.1161/01.STR.0000117096.61838.C7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bazaldua OV, Davidson DA, Kripalani S. eChapter 1. Health Literacy and Medication Use : DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al., Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 9th ed New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27., Feigin VL, Nguyen G, et al. , GBD 2016 Lifetime Risk of Stroke Collaborators . Global, regional, and country-specific lifetime risks of stroke, 1990 and 2016. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2429–37. 10.1056/NEJMoa1804492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zenebe G, Alemayehu M, Asmera J. Characteristics and outcomes of stroke at Tikur Anbessa teaching Hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J 2005;43:251–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girum T, Mesfin D, Bedewi J, et al. The burden of noncommunicable diseases in Ethiopia, 2000-2016: analysis of evidence from global burden of disease study 2016 and global health estimates 2016. Int J Chronic Dis 2020;2020:1–10. 10.1155/2020/3679528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alemayehu B, Oli K. Stroke admission to Tikur Anbassa teaching hospital: with emphasis on stroke in the young. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 2002;16:309–15. 10.4314/ejhd.v16i3.9799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. 2015 American heart Association/American stroke association focused update of the 2013 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke regarding endovascular treatment: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke 2015;46:3020–35. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang T, Gajasinghe S, Arambepola C. Prevalence of stroke and its risk factors in urban Sri Lanka: population-based study. Stroke 2015;46:2965–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chhabra M, Sharma A, Ajay KR, et al. Assessment of risk factors, cost of treatment, and therapy outcome in stroke patients: evidence from cross-sectional study. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2019;19:575–80. 10.1080/14737167.2019.1580574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desita Z, Zewdu W. Ct scan patterns of stroke at the University of Gondar Hospital, North West Ethiopia. Br J Med Med Res 2015;6:882–8. 10.9734/BJMMR/2015/14849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alkali NH, Bwala SA, Akano AO, et al. Stroke risk factors, subtypes, and 30-day case fatality in Abuja, Nigeria. Niger Med J 2013;54:129. 10.4103/0300-1652.110051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komolafe MA, Komolafe EO, Fatoye F. Profile of stroke in Nigerians: a prospective clinical study 2007.

- 37.Atadzhanov M, Mukomena P N, Lakhi S. Stroke characteristics and outcomes of adult patients admitted to the University teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. The Open General and Internal Medicine Journal 2012;5:3–8. 10.2174/1874076601205010003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patne S, Chintale K. Study of clinical profile of stroke patients in rural tertiary health care centre. Int J Adv Med 2016;3:666–70. 10.18203/2349-3933.ijam20162514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shenkutie Greffie E, Greffie ES, Mitiku T. Risk factors, clinical pattern and outcome of stroke in a referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin Med Res 2015;4:182–8. 10.11648/j.cmr.20150406.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang F-L, Guo Z-N, Wu Y-H, et al. Prevalence of stroke and associated risk factors: a population based cross sectional study from Northeast China. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015758. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gedefa B, Menna T, Berhe T, et al. Assessment of risk factors and treatment outcome of stroke admissions at St. Paul’s teaching hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Neurol Neurophysiol 2017;08:1–6. 10.4172/2155-9562.1000431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyene H. A two year retrospective cross-sectional study on prevalence, associated factors and treatment outcome among patients admitted to medical ward (stroke unit) at. 2018 Jimma, South West, Ethiopia: Jimma University Medical Center, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nkusi AE, Muneza S, Nshuti S, et al. Stroke burden in Rwanda: a multicenter study of stroke management and outcome. World Neurosurg 2017;106:462–9. 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.06.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kassaw A. Prevalence, nursing managements and patients‟ outcomes among stroke patients admitted to Tikur Anbessa specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2018. Addis Ababa Universty, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker RW, Rolfe M, Kelly PJ, et al. Mortality and recovery after stroke in the Gambia. Stroke 2003;34:1604–9. 10.1161/01.STR.0000077943.63718.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rymer MM. Hemorrhagic stroke: intracerebral hemorrhage. Mo Med 2011;108:50–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masood CT, Hussain M, Abbasi S. Clinical presentation, risk factors and outcome of stroke at a district level teaching hospital. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad 2013;25:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, et al. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke 2004;35:776–85. 10.1161/01.STR.0000116869.64771.5A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elliott WJ. Systemic hypertension. Curr Probl Cardiol 2007;32:201–59. 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. New England Journal of Medicine 2008;358:1887–98. 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Abebe TB, et al. In-Hospital mortality among ischemic stroke patients in Gondar university hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Stroke Res Treat 2019;2019:1–7. 10.1155/2019/7275063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Carvalho JJF, Alves MB, Viana Georgiana Álvares Andrade, et al. Stroke epidemiology, patterns of management, and outcomes in Fortaleza, Brazil: a hospital-based multicenter prospective study. Stroke 2011;42:3341–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Q, Wu C, Luo H, et al. Trends in in-hospital mortality among patients with stroke in China. PLoS One 2014;9:e92763. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tirschwell DL, Ton TGN, Ly KA, et al. A prospective cohort study of stroke characteristics, care, and mortality in a hospital stroke Registry in Vietnam. BMC Neurol 2012;12:150. 10.1186/1471-2377-12-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernheisel CR, Schlaudecker JD, Leopold K. Subacute management of ischemic stroke. Am Fam Physician 2011;84:1383-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adams H, Adams R, Del Zoppo G, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with ischemic stroke: 2005 guidelines update a scientific statement from the stroke Council of the American heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke 2005;36:916–23. 10.1161/01.STR.0000163257.66207.2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Arima H, Yang J, et al. Mannitol and outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage: propensity score and multivariable intensive blood pressure reduction in acute cerebral hemorrhage trial 2 results. Stroke 2015;46:2762–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aminmansour B, Tabesh H, Rezvani M, et al. Effects of Mannitol 20% on Outcomes in Nontraumatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Adv Biomed Res 2017;6:75. 10.4103/2277-9175.192628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sagui E, M'Baye PS, Dubecq C, et al. Ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes in Dakar, Senegal: a hospital-based study. Stroke 2005;36:1844–7. 10.1161/01.STR.0000177864.08516.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alemayehu CM, Birhanesilasie SK. Assessment of Stoke patients: occurrence of unusually high number of haemorrhagic stroke casesin Tikur Anbessa specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Clin Med Res 2013;2:94–100. 10.11648/j.cmr.20130205.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Connor MD, Walker R, Modi G, et al. Burden of stroke in black populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:269–78. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Asefa G, Meseret S. Ct and clinical correlation of stroke diagnosis, pattern and clinical outcome among stroke patients visting Tikur Anbessa Hospital. Ethiop Med J 2010;48:117–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.