Abstract

Introduction

Interprofessional (IP) clinical care is ideally taught in authentic environments; however, training programs often lack authentic opportunities for health professions students to practice IP patient care. Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) can offer such opportunities, particularly for geriatric patient care, but are underutilized as training sites. We present an IP nursing facility rotation (IP-SNF) in which medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy students provided collaborative geriatric patient care.

Methods

Our 10-day immersion rotation focused on four geriatric competencies common to all three professions: appropriate/hazardous medications, patient self-care capacity, evaluating and treating falls, and IP collaboration. Activities included conducting medication reviews, quarterly care planning, evaluating functional status/fall risk, and presenting team recommendations at SNF meetings. Facility faculty/staff provided preceptorship and assessed team presentations. Course evaluations included students' pre/post objective-based self-assessment, as well as facility faculty/staff evaluations of interactions with students.

Results

Thirty-two students (15 medical, 12 pharmacy, five physical therapy) participated in the first 2 years. Evaluations (n = 31) suggested IP-SNF filled gaps in students' geriatrics and IP education. Pre/post self-assessment showed significant improvement (p < .001) in self-confidence related to course objectives. Faculty/staff indicated students added value to SNF patient care. Challenges included maximizing patient care experiences while allowing adequate team work time.

Discussion

IP-SNF showcases the feasibility of, and potential for, engaging learners in real-world IP geriatric patient care in a SNF. Activities and materials must be carefully designed and implemented to engage all levels/types of IP learners and ensure valuable learning experiences.

Keywords: Interprofessional Education, Geriatrics, Skilled Nursing Facility, Curriculum Development

Educational Objectives

By the end of these activities, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Identify medications to be avoided and used with caution in geriatric patients.

-

2.

Demonstrate the drug regimen review process for a geriatric patient.

-

3.

Describe the importance of medication reconciliation in older adults.

-

4.

Construct a patient care plan that outlines medical, psychosocial, and function-based problems for a patient residing in a nursing facility.

-

5.

Present a patient's care plan at team interprofessional care planning meetings.

-

6.

Identify potential causes for falls in older adult patients who have fallen or are at risk for falls.

-

7.

Develop a fall prevention strategy for an older adult patient who has fallen or is at risk of falling.

-

8.

Demonstrate cooperation as an interprofessional team that places the interests of patients first.

-

9.

Express knowledge and opinions responsively and respectfully and listen actively on an interprofessional team.

Introduction

Interprofessional (IP) collaboration is an essential aspect of patient care given the increasingly complex systems in which patients receive care.1,2 IP education (IPE) for health professions students focuses on professional competencies, which include developing a clear understanding of provider roles and responsibilities, team communication, IP teamwork, and the ethics of IP collaboration.3 The actual practice of IP collaboration, though, requires training in real IP clinical settings. Others have shown that work-based clinical training environments provide students opportunities to learn more effectively in collaboration with other students,4,5 as well as offering a level of authenticity and responsibility that encourages learning.6 Real-world patients provide a different experience than simulation, and there is an increasing push to integrate more real-world patient care in IPE7–9; however, finding environments in which IP learners can care for patients and learn from each other can be challenging.

Geriatric medicine incorporates IP teams to optimize care of complex older adults' medical, functional, and psychosocial needs. For example, educators have used fall assessment as a means to engage IP teams of providers and students in learning and patient care.10,11 For health professions students, MedEdPORTAL provides examples of IP geriatric teaching activities, but the majority use simulated patients in constructed settings.12–16 In Rennke and colleagues' GeriWard and Larson and colleagues' GeriWard Falls curricula, IP student teams work with actual hospitalized older adults, but these short-lived (2 hours) experiences occur in an acute care rather than outpatient or longitudinal environment, which limits patient and team continuity for students.17,18 Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), unlike the inpatient wards, care for complex geriatric populations and offer real-world clinical environments focused on longer-term patient care with intrinsic and authentic IP team practice.

While many health professions programs now integrate SNF site-based teaching for transitions of care and residential care curricula,19,20 the SNF is an underutilized IP immersive clinical teaching setting for health professions students.21 Some have constructed onetime team-focused activities to model IP practice. Ford and colleagues created an IP student team experience involving interviewing an older adult patient at a local nursing home.22 Kent and colleagues had senior-level IP student teams complete onetime patient consultations in a residential care facility in Australia.23 Students had high satisfaction, and Kent's team found the facilities to be useful IP teaching environments. Annear and colleagues added 5-day-long immersion experiences where IP teams completed a single comprehensive patient care assessment and case presentation at Australian aged-care facilities.24,25 While these deep-dive single-patient care experiences can improve IP collaboration between students, immersion in multifaceted day-to-day SNF-based patient care could provide more comprehensive geriatric IPE opportunities.

At the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), IPE primarily occurred through didactics, small groups, and simulated patient experiences.26 Opportunities for UCSF students to interact with other health professions students in IP clinical settings were limited. No activities or rotations offered senior-level health professions students at the end of training chances to practice real-world clinical skills as teams prior to transitioning to residency or professional practice.

To fill an institutional IP training gap, the UCSF Division of Geriatrics, in partnership with UCSF's Schools of Pharmacy and Physical Therapy, developed an IP SNF-based rotation (IP-SNF) providing senior-level medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy students with the opportunity to work as an IP student team in a clinical care setting. The rotation's goal was to engage all three health professions in geriatric care while fostering IP team collaboration.

Methods

Competencies and Objectives

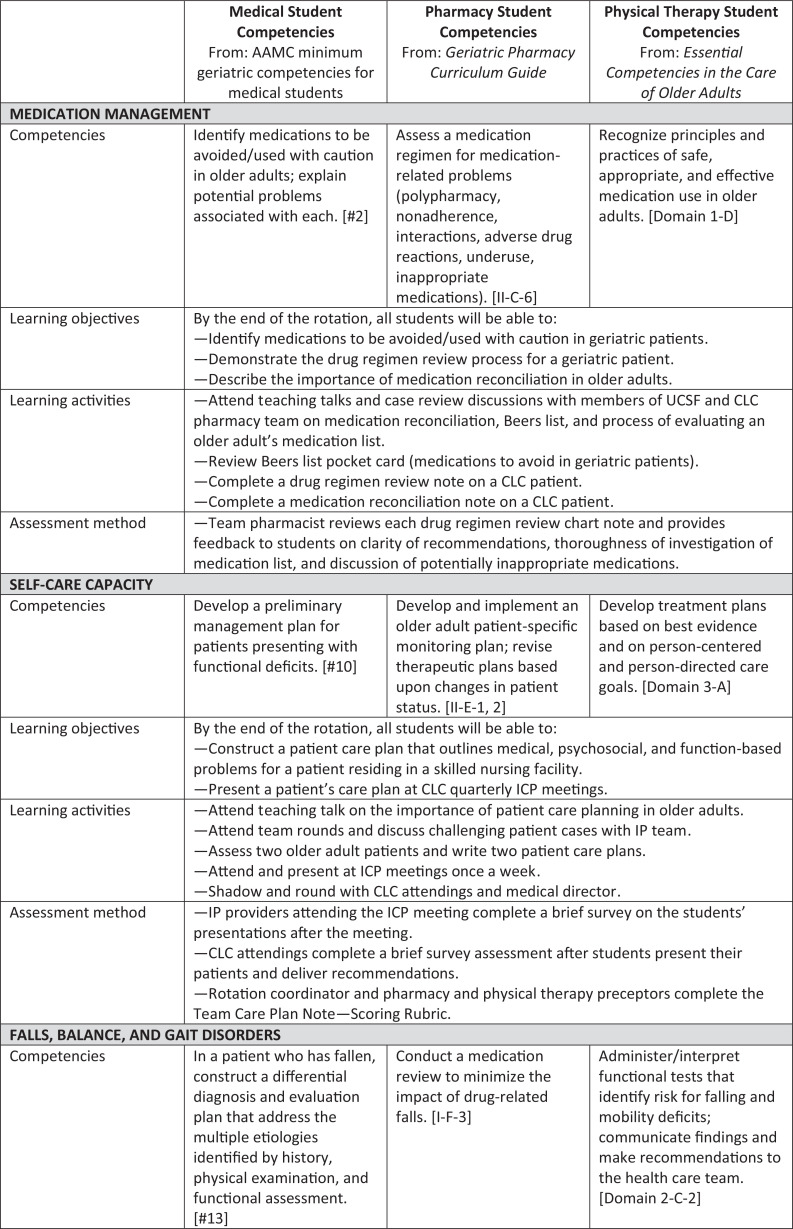

We developed objectives and activities from four geriatric IP competencies common to medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy students27–30: (1) identifying and addressing appropriate/hazardous medications, (2) assessing patient self-care capacity, (3) evaluating and treating falls/gait disorders, and (4) demonstrating effective IP communication and collaboration (Figure).

Figure. Summarized IP-SNF curriculum competencies, objectives, activities, and assessment methods. Competencies listed are based on profession guidelines as applicable. Objectives, activities, and assessments are divided by major rotation components. Abbreviations: CLC, Community Living Center; ICP, interprofessional care planning; IP, interprofessional; IPE, interprofessional education; UCSF, University of California, San Francisco.

Setting and Participants

We constructed a 10-day rotation of activities at the San Francisco VA Medical Center's Community Living Center (CLC). A SNF with more than 100 beds, the CLC cared for veterans with complex coexisting mental health and medical diagnoses. Ten different health professions worked as part of the CLC's care team: medicine, nursing, social work, pharmacy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, recreation therapy, geropsychology, nutrition, and spiritual care.

Senior (i.e., in the last year of a training program) medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy students from UCSF and visiting senior students from the University of the Pacific and A.T. Still University participated in IP-SNF as an elective (medical and UCSF pharmacy) or as an integrated part of their longitudinal VA rotations (non-UCSF pharmacy and physical therapy). These professions (medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy) were the only ones with existing rotations and faculty preceptors within our CLC and were the only professions represented in IP-SNF. Students were required to have completed at least one clinical clerkship prior to participating in IP-SNF.

Course faculty constructed IP-SNF teams based on when students of different professions had overlapping CLC rotations. We formed an IP-SNF team when students representing two or more professions concurrently rotated at the CLC. Some teams contained only a medical and a pharmacy student if there was no physical therapy student rotating at the same time.

Equipment and Environment

Students had a CLC team workroom with desk space, two computers, two whiteboards, and office supplies. They had the resources of the CLC at their disposal and access to, and training on, the VA's electronic medical record.

Personnel

The rotation was cofacilitated by the medical director of the CLC and another geriatrician. The cofacilitators coordinated the student teams and managed schedules, materials, computer access, CLC orientation, and patients. They taught rotation didactics and precepted patient care, documentation, and preparation for presentations for all students. The medical director solely coordinated the rotation after the initial start-up year. Members of CLC pharmacy and physical therapy teams provided teaching, precepting, and assessments of the student team throughout the course. Individual CLC providers assessed student team care and fall prevention plans on their own patients. CLC staff assessed student teams and provided feedback on presentations at team meetings.

Design

The UCSF and San Francisco VA Institutional Review Boards approved this study as exempt.

IP-SNF was 2 weeks (10 working days) in duration. Schedules met the needs of the students, preceptors, and CLC meetings but always included the same foundational content (Figure). We utilized CLC IP team patient care meetings, which exist, in some form, in many SNF and long-term care environments, for hands-on and patient-centered immersive student learning experiences. These experiences included the following:

-

•

Screening committee/meetings, where students observed how CLC faculty and staff determined appropriateness of admission and discussed challenges of discharge planning.

-

•

Wound care rounds, where wound care nurses provided hands-on training on complex patient wound care and discussed with students the challenges of wound care in older adults.

-

•

Interprofessional care planning (ICP) or Medicare rounds, where students actively participated with the IP team in patient case discussions and comprehensive care planning (also a part of key rotation activities; see Figure).

-

•

Fall Focus meetings, where students actively participated in IP team patient case discussions and fall prevention plans (also a part of key rotation activities; see Figure).

-

•

Patient behavior rounds, where students actively participated in patient case discussion and brainstorming to create challenging behavior care plans and also took part in system-level discussions about CLC behavioral care policies.

During each block of IP-SNF, student teams completed the following rotation activities (summarized in the Figure):

-

•Medication management:

-

○Objectives: Targeting Educational Objectives 1–3.

-

○Instruction: Pharmacy preceptors discussed principles of medication management, including (1) medication reconciliation's importance, (2) what medications should be generally avoided in older adults (e.g., Beers criteria), and (3) the process of reviewing an older adult's medication regimen by actively showing them the process with a CLC patient's medication list, with students. Students were given a Beers criteria pocket card for reference.31

-

○Activities: Students had 2–3 hours the afternoon after receiving instruction from pharmacy faculty for drug regimen and medication reconciliation activities. Student teams completed two drug regimen reviews and medication reconciliation notes. For the drug regimen review, students received instructions from the CLC's pharmacist (Appendix A) about reviewing a medication list and determining appropriate dosing given renal and hepatic function. For medication reconciliation, students reviewed a newly admitted patient's medication list from before CLC admission and compared it to the current list. Students looked for discrepancies and dosing appropriateness. For both activities, students interviewed patients as a team to discuss patients' understanding of their medications and to answer medication questions.

-

○Student assessment: CLC pharmacists reviewed drug regimen review and medication reconciliation notes and provided constructive feedback (no formal rubric) on students' thoroughness of medication review and clarity and appropriateness of recommendations.

-

○

-

•Patient self-care capacity:

-

○Objectives: Targeting Educational Objectives 4 and 5.

-

○Instruction: The cofacilitators taught students about care team members within a SNF environment, the importance of comprehensive care planning for geriatric patients, and the format of IP team care planning meetings (Appendix B). Formal instruction occurred in the morning during week 1 of the rotation, and students completed patient assessments and plan construction in the afternoon. Teams observed ICP meetings to learn about patient care planning at SNFs. Students and faculty used cases discussed in screening, behavior, and fall focus rounds, in real time, to frame geriatric principles of care.

-

○Activities: Students had 3–5 hours to complete each of two patient care plans for patients scheduled for ICP team meetings. Cofacilitators gave them instructions on how to prepare for ICP meetings (Appendix C), including (1) reviewing the patient's chart together, (2) evaluating the patient as a group, and (3) creating a care plan together focusing on active medical, psychosocial, functional, and medication-related problems. Teams received guidance on and assistance with all aspects of care plan construction from course cofacilitators and CLC preceptors. The CLC's geropsychologist and mental health clinical nurse specialist also assisted students with patient care concerns related to mental health. Teams presented their plan to the patient's primary CLC attending and then presented the patient's updates at the CLC ICP meetings.

-

○Multimodal assessment of the student team's presentation and care plan: (1) CLC staff members (e.g., nursing, social work) attending the ICP meetings completed a four-question 5-point Likert scale: the ICP Team Assessment (Appendix D). (2) The patient's primary CLC attending completed a seven-question 5-point Likert scale: the Attending Assessment of Team's Care Plan (Appendix E). (3) The rotation coordinator, pharmacy preceptor, and physical therapy preceptor scored, as a group, the student team's care plan using the Team Care Plan Note—Scoring Rubric, focusing on incorporation of functional assessment, medication review, and psychosocial assessment (Appendix F). The scoring rubric helped identify areas for feedback to teams.

-

○

-

•Falls, balance, and gait disorders:

-

○Objectives: Targeting Educational Objectives 6 and 7.

-

○Instruction: Course cofacilitators taught about falls (epidemiology, risk factors, history and exam, risk prevention; Appendix G) based on the GeriWard Falls curriculum but modified its content to focus on older adults residing in SNFs rather than inpatient wards.17 Formal teaching occurred in the morning during week 1 of the rotation so students could complete their fall assessments and plan construction in the afternoon.

-

○Activities: Students had 2–3 hours for fall evaluation and prevention plan completion. We identified a patient who had fallen in the past week and instructed students to (1) review the patient's fall history together, (2) evaluate the patient as a team, and (3) create a fall prevention plan. Teams completed two separate fall evaluations and fall prevention strategy notes using a note template (Appendix H). Teams presented their fall prevention plan to the patient's primary CLC attending and delivered a 5-minute presentation on their patient at the Fall Focus meeting (IP group focused on fall prevention). At SNFs where there was no Fall Focus–type meeting, student teams could present their fall prevention note to the patient's primary attending, medical director, nursing, or rehab team.

-

○Multimodal assessment of the student team's presentation and meeting participation: The assessments were based on materials from the GeriWard Falls curriculum.17 (1) Fall Focus team members completed a four-question 5-point Likert scale: the Fall Focus Team Assessment (Appendix I). (2) The patient's primary attending completed a six-question 5-point Likert scale: the Attending Assessment of Team Fall Recommendations (Appendix J). (3) The course cofacilitators scored the teams' fall prevention strategy note based on the Fall Evaluation and Prevention Strategy Note—Scoring Rubric (Appendix K). The scoring rubric helped identify areas for feedback to teams.

-

○

-

•IP collaborative practice skills:

-

○Objectives: Targeting Educational Objectives 8 and 9.

-

○Instruction: Preceptors taught patient self-care capacity activities (Appendix G), including discussion of the roles and responsibilities of each CLC-represented profession in the context of care planning for patients. Students observed informal IP teaching through CLC team role modeling.

-

○Activities: Students worked together daily as an IP team. They had unstructured morning huddles where they followed up on questions that had arisen the prior day and peer-taught about patient care issues. Teams engaged as part of the CLC team meetings. A hallmark component of IP-SNF was the students' daily patient care engagement as an IP team.

-

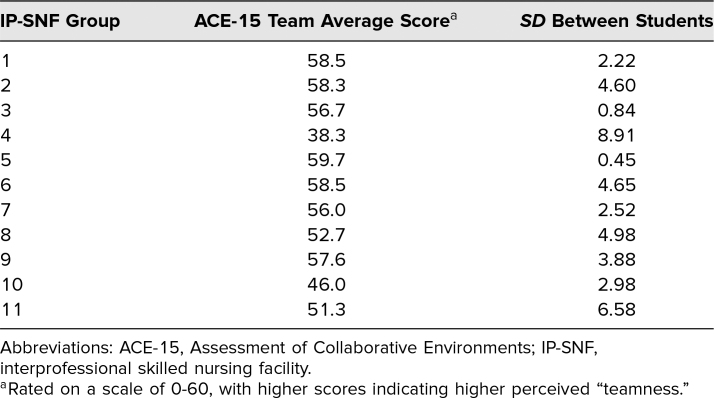

○Student assessment: We embedded items related to the students' IP collaboration in the Fall Focus and ICP Team Assessments (Appendices D and I). Additionally, students were asked to complete the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (ACE-15) at the end of the rotation.32

-

○

Evaluation Strategy

Student grades and summative assessment

All 2-week UCSF senior level electives used a pass/fail grade system; students who completed all rotation activities received a passing grade. The course director provided UCSF competency-based quantitative and qualitative feedback on students using existing institution-wide evaluation metrics. Students' summative assessment included formative feedback from the care planning and fall prevention activity rubrics (Appendices D and K).

Evaluation of IP-SNF learning objectives

Students completed a pre/post 15-item self-assessment survey using a 5-point scale (1 = Definitely Cannot, 5 = Definitely Can) on the first and last days of the rotation. The surveys measured self-reported confidence related to rotation objectives (Appendices L and M). We included an N/A option if students felt an item was not relevant to their profession, but we believed all survey items were appropriate given their basis in mutual competencies. The course cofacilitators designed the self-assessment survey based on rotation objectives.

Evaluation of course and activities

Students completed a rotation evaluation including 10 questions regarding IP-SNF's structure and their rotation experience rated on 5-point Likert scales (Appendix M). The course cofacilitators created the rotation evaluation based on prior IP teaching activity evaluations at UCSF.14 It also included four short-answer questions regarding overall experience. Students completed two activity evaluations based on those from GeriWard Falls and consisting of five to six Likert-scale survey questions and two to three short-answer questions addressing the care planning and fall prevention activities (Appendices N and O).17

Evaluation of IP environment

IP-SNF teams completed the ACE-15 on their final rotation day. The ACE-15 quickly (<5 minutes) measured IP “teamness,” or how collaborative an IP team perceived its environment as being, using a 15-item self-report survey.32 Individual scores were averaged to create a team score and standard deviation. Higher score and lower standard deviation suggested that a team perceived the environment as more collaborative and that members were more unified in that perception.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis

Paired t tests assessed for change in self-reported pre/post confidence. Additionally, we calculated descriptive statistics on activity evaluation data collected from students (fall prevention and care planning exercise) and CLC attendings and staff (regarding student team performance). We analyzed ACE-15 data based on group average score and standard deviation.

Qualitative analysis

The course coordinator reviewed all written student feedback from the rotation evaluations and activity evaluations, as well as comments from attendings and staff. She conducted open coding to identify themes using Dedoose Version 8.0.31 (SocioCultural Research Consultants). The medical director also completed select open coding of written feedback to confirm codes and themes.

Results

Student Characteristics

Thirty-two students (15 medical, 12 pharmacy, and five physical therapy) participated as 15 unique student teams in the first 2 years of IP-SNF; 72% of all students were female, and the average age was 27.2 years. Most (26) students were from UCSF; three pharmacy students and three physical therapy students were from other institutions. Only 22% of students had prior exposure to a SNF setting in any capacity. Physical therapy students rotated at the CLC for 10–16 weeks; thus, most physical therapy students participated in IP-SNF more than once, but pre/post self-assessment data were collected only during their first IP-SNF experience.

Evaluation of Learning Objectives

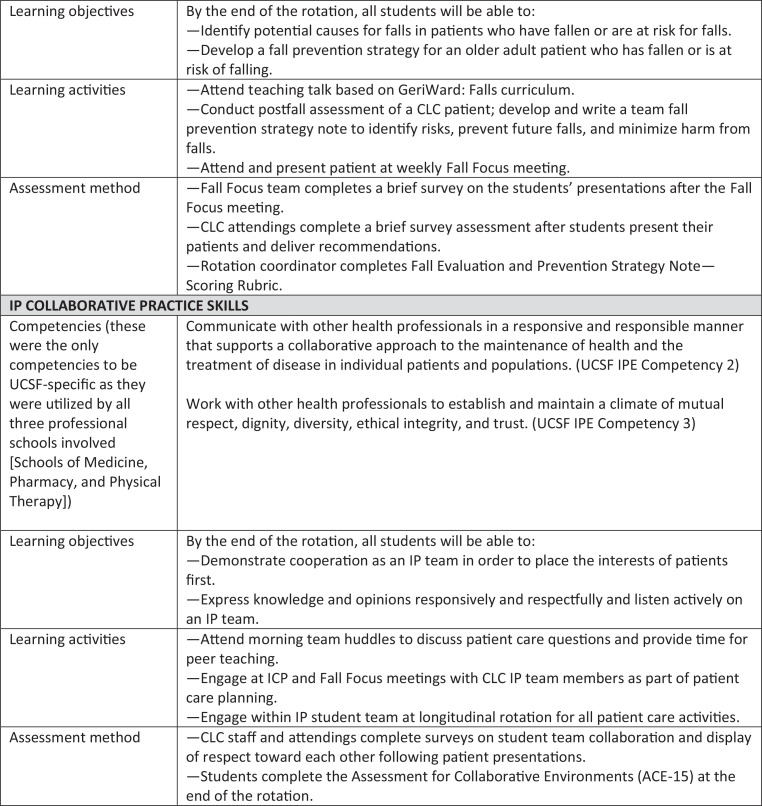

One student did not complete a postassessment, so our results reflect 31 student responses over 2 years of IP-SNF. The pre/post 15-item self-assessment survey (Appendices L and M) showed that students endorsed improvement in perceived confidence related to all IP-SNF geriatric patient care-based objectives (p < .001; Table 1) after completing IP-SNF activities.

Table 1. Student Pre-Post Self-Assessment of Confidence in Geriatric Skill (n = 31).

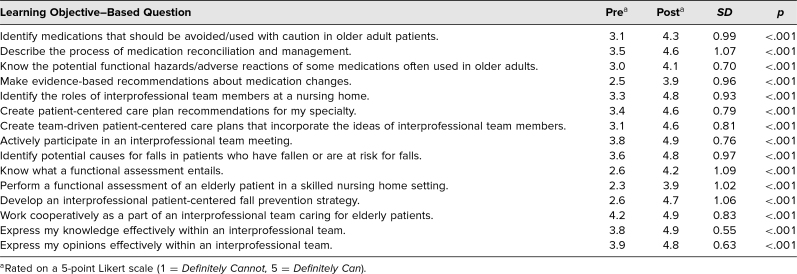

Evaluation of IP-SNF Course and Activities

Course evaluation

Student feedback from the rotation evaluation was favorable, with 31 out of 32 total students responding. Students felt the course increased their skill set in geriatric care and provided a better understanding of how SNFs function (M = 4.7 out of 5, SD = 0.46, and M = 4.8, SD = 0.37, respectively). Students found facility staff (M = 4.8, SD = 0.48) and attendings (M = 4.7, SD = 0.51) to be receptive to student inclusion. Table 2 highlights additional results.

Table 2. Student Evaluation of Rotation and Activities (n = 31).

Coding of student narratives demonstrated themes related to IP-SNF's strengths and areas for improvement. Students identified the rotation as a positive opportunity to develop a broader view of geriatrics and SNF care:

-

•

“Spending more time in the CLC allowed me to get to know patients… and see how lively and dynamic a place it can be.”

-

•

“I truly enjoyed being able to see patients and follow-up with how they are doing. Was also great to see the activities that go on in a nursing home.”

-

•

“I really enjoyed being able to see multiple facets/components of care in elderly patients.”

Students highlighted the opportunity to engage in peer teaching and learning as well as foster peer relationships:

-

•

“I loved working with other students from other fields because we got to ask each other questions without feeling restricted or judged.”

-

•

“I could see how other specialties provided care and how they thought about patients.”

-

•

“I've never worked so intimately with another health professions student. It was eye opening and really beneficial.”

-

•

“Gave us time to get to know one another as individuals—relationships not defined just as different professions.”

Students recognized the unique opportunity to care for patients in an authentic IP environment:

-

•

“Much more real-time and in the real-world. So much more useful compared to previous interprofessional experiences.”

-

•

“This is my first clinical, real world experience working interprofessionally with other learners. It made the experience more tangible, weighty, and exciting than the mock sessions we've done before.”

Students also provided constructive feedback on areas to improve. This included budgeting time more effectively:

-

•

“I felt there was not enough time to complete notes and felt rushed at times which I felt affected the quality of my work.”

-

•

“There is so much I want to learn about geriatrics—it's hard to fit it all in!”

Students suggested increasing the number of patient encounters:

-

•

“I would love to see more patients because they seem very interesting.”

-

•

“To the extent possible, encourage continuity of patient care.”

Students indicated a desire to spend more time with other professionals:

-

•

“I would love to have more shadowing opportunities of the different healthcare professionals involved with the geriatric care.”

-

•

“I'd like to have more time to work with recreation therapy.”

Rotation activity evaluations

Students rated IP-SNF's fall prevention and care planning activities overall positively (M = 4.6 out of 5, SD = 0.73, and M = 4.8, SD = 0.65, respectively). (See Table 2 for additional ratings.) Students commented that the activities were enjoyable because of the opportunity to work as an IP team during the patient assessment and plan creation. Students also appreciated their different IP roles and perspectives; some pharmacy, and physical therapy students, in particular, noted that hearing the medical student's perspective was valuable.

Staff and attending assessment of student team performance

CLC staff and attending assessments of student presentations were overwhelmingly positive. Staff (n = 67) found teams to be collaborative (M = 4.9 out of 5, SD = 0.31), patient centered (M = 4.9, SD = 0.34), and able to identify appropriate history and plans in their presentations (M = 4.9, SD = 0.33). Staff comments demonstrated appreciation of having students at team meetings, noting their plans were “both appropriate and creative”; one nurse commented, “I appreciate this presence in ICP—it's like spring!” Faculty completed 15 assessments of the IP teams' care plans and suggested student teams were clear (M = 4.7, SD = 0.46), and helpful (M = 4.7, SD = 0.46) in their recommendations. Faculty did not report a notable negative impact to workflow (M = 1.4, SD = 0.63, lower numbers indicating less intrusion on workflow). One attending even noted, “I was very skeptical when asked to do this but was very pleasantly surprised and pleased with the outcome. The team's recs were very thorough and concise and helped me to consider things I wouldn't have otherwise.”

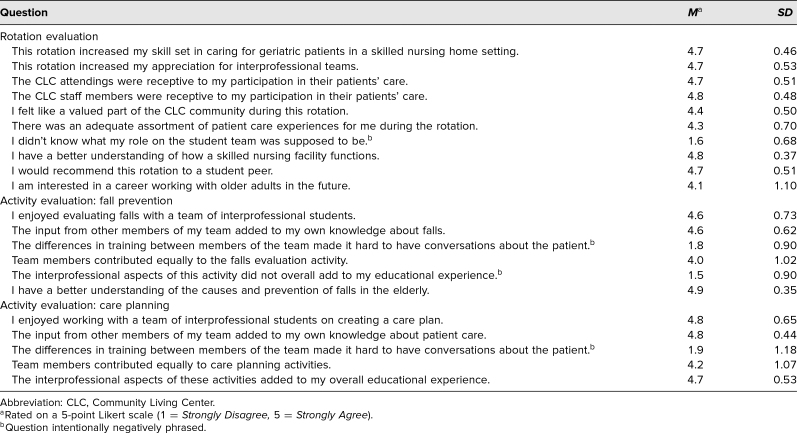

ACE-15 (IP environment)

We excluded from analysis rotations during which one or more students did not complete the ACE-15 or for which a student was switched midway through the rotation; thus, the analysis included 11 (out of 15) student teams incorporating 28 data points. Team overall averages (higher scores indicating the environment promoted teamness) suggested that the SNF environment was conducive for IP teamwork (Table 3). Groups with low overall averages also tended to have higher standard deviations, suggesting more within-team variation regarding the group's perception of IP collaboration within the CLC learning environment.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of ACE-15 From IP-SNF Teams (n = 28).

Discussion

IP-SNF demonstrated a model of activities and environment in which health professions students could engage in authentic IP clinical collaboration. It suggested that teaching a variety of practical, IP, geriatric-focused, patient care experiences in the previously untapped setting of the VA's SNF (CLC) was feasible. IP-SNF also filled a gap in UCSF's existing IP curriculum, as it was the only opportunity for student teams to provide clinical care together; we expect that these gaps exist at other institutions and would be fillable with IP-SNF's model. By including senior-level students who had prior clinical experience, IP-SNF allowed students to apply existing clinical knowledge to patient care while furthering IP collaboration skills. We feel the inclusion of earlier learners, or learners at significantly different levels of training (e.g., preclerkship students and advanced clerkship students), would impede collaboration or create a hierarchical learning environment.

Adding to the authenticity of IP clinical care was the opportunity to witness IP role modeling through the daily engagement of CLC team members at the meetings and care planning sessions students attended. While most of the CLC staff were not trained formally in IPE, they regularly demonstrated patient-centered care and IP teamwork. ACE-15 results indicate that the CLC provided a solid IP team environment for learning, suggesting other SNFs could be strong possibilities for IP training opportunities.

Student and CLC staff/attending feedback allayed our concerns that placing IP student teams in a busy SNF setting would hinder workflow. Feedback suggested that teaching within the SNF was both feasible and enjoyable for all parties and did not negatively impact workflow. In addition, we were pleased to see that incorporating students into CLC team meetings, such as ICP and Fall Focus meetings, provided staff and attendings with opportunities to consider alternative, creative avenues for patient care. Even with increasing time constraints on providers of all professions, we feel that IP-SNF implementation at other intuitions is still feasible given the lack of impact on provider workflow—and student team involvement might even improve patient care given student teams' IP focus.

The initial implementation of IP-SNF taught us content, structure, and logistics lessons. One of the biggest lessons learned was how much time it took the rotation coordinator to create and schedule meaningful experiences aligning with the goals of all three professions (medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy). Initially, the rotation coordinator spent up to 16 hours a week engaged with students or managing schedule logistics; however, with simplification of scheduling (e.g., constructing a basic standard schedule) and decompression of direct student observation and precepting, that time was reduced to less than 6 hours a week. Direct teaching time was reduced by encouraging peer and CLC team teaching rather than relying on the coordinator to answer all clinical care questions. Engaging students in patient care activities with other CLC team members (e.g., dietician, geropsychologist) reduced the coordinator's direct patient care supervision and filled student-requested niches related to additional activities.

Student feedback on the first few blocks of IP-SNF noted that less formal but more frequent patient assessments, particularly with other IP team members, provided a nice contrast to the more in-depth fall and care planning patient activities, where sometimes one profession dominated the plan. Adding shadowing of other CLC team members and rounding with attendings also helped to address gaps. Based on student feedback and interest in peer teaching, we added student-led teaching presentations at the end of the block where each student reviewed the literature, prepared a short talk on a topic they felt was relevant to geriatrics in their profession, and demonstrated critical appraisal of a topic (e.g., review of a new therapeutic for dementia-related behaviors).

Logistically, we found that IP-SNF worked best when students had dedicated team space and resources for the entire block. A team workroom with computers to share, whiteboards, a printer, and lockable storage cabinets helped students develop a sense of belonging within the CLC community rather than interloping on the facility. Finding adequate space required negotiation with facility administrators but was a valuable addition to the course.

There are limitations in our course evaluation plan. Based on student feedback and pre-/postrotation self-perceived confidence scores related to geriatric patient care, IP-SNF increased students' confidence in caring for older adults. However, a limitation of our evaluation plan is that we do not have long-term follow-up data related to sustained confidence. Students were in the last year of their training programs and thus not trackable at large intervals after IP-SNF participation as they had often moved on to different institutions. Future programs that replicate IP-SNF's model would benefit by follow-up surveys or interviews with participants to capture long-term confidence and skill trends further from IP-SNF. Another limitation in our evaluation plan is that we have no formal knowledge assessment for students and rely on students' self-perceived confidence, which has limitations related to perceived overconfidence.33,34 However, since the self-perceived knowledge survey was based on rotation objectives and rotation activities completed throughout IP-SNF and students were assessed in other ways (e.g., CLC team evaluations of student teams, note rubrics), we feel that the students' increased self-perceived confidence correlates with those other assessment metrics.

We recognize that there are potential limitations to implementing IP-SNF at other institutions. While the core components of IP-SNF are replicable at many SNF settings, not all SNFs include the extensive team-focused patient care activities available at the CLC. Most SNFs address medication reconciliation, provide rehabilitation services and wound care, have quarterly care planning meetings, and track and review patient falls. SNFs are not required, though, to hold the additional team-focused experiences our students attended, such as patient behavior rounds and screening meetings. Additionally, physicians, pharmacists, and physical therapists are not on-site at all SNFs every day. We feel, that given the number of teaching institutions affiliated with VA medical centers that include a CLC, there might still be broad applicability of IP-SNF to VA-based educators. Institutions not affiliated with a VA CLC could adapt and implement IP-SNF activities as possible at their SNFs.

IP-SNF requires a cohort of team members amenable to voluntary teaching. Most teaching activities require only a few hours from each profession, and teaching timing can be tailored to the availability of the on-site providers. Additionally, most teaching is relevant to direct patient care and could be integrated into daily routines. Aside from the medical director of the CLC, who had IP-SNF education-related duties, no other provider at the CLC had protected time for teaching, yet all were willing to precept and teach students. A limitation of the IP-SNF model is that it does require having preceptors in each profession available to supervise students, and there were blocks where students were interested in participating in IP-SNF but a preceptor was away. During those blocks, we did not run IP-SNF. Lack of preceptorship limited students to blocks when preceptors were on-site.

IP-SNF's structure and goals could be replicated at other institutions and would ideally incorporate professions best represented at an institution. For example, sites could include nursing students instead of, or in addition to, medical students and could complete similar patient care activities and participate as an IP team. Our inclusion of medical, pharmacy, and physical therapy students in IP-SNF was related to the availability of those students at the CLC, and we feel inclusion of other professional students would enrich the curriculum's activities. IP-SNF's goal to maximize the SNF environment for IP geriatric patient care experiences provides possibilities for educators to immerse IP student teams in everyday patient care activities that best align with their own SNF settings and resources. The positive student and provider feedback from IP-SNF suggests that students desire and appreciate authentic, hands-on IP patient care experiences and that health professions student clinical curricula should regularly offer this type of rotation.

Appendices

- Drug Regimen Review Instructions.docx

- Patient Care Planning Slides.pptx

- ICP Meeting Preparation.docx

- ICP Team Assessment of Student Presentations.docx

- Attending Assessment of Care Plans.docx

- Team Care Plan Note Rubric.docx

- Falls in the Skilled Nursing Facility Setting.pptx

- Falls Prevention Strategy Template.docx

- Fall Focus Team Assessment.docx

- Attending Assessment of Fall Prevention Plan.docx

- Fall Prevention & Postfall Evaluation Rubric.docx

- Prerotation Survey.docx

- Postrotation Survey.docx

- Student Evaluation of Care Planning Activity.docx

- Student Evaluation of Fall Planning Activity.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and staff of the San Francisco VA Community Living Center (CLC) for their active participation and enthusiasm in engaging with the health professions students taking part in this rotation. We particularly thank Drs. Rachel Campbell and Jessica Larson from the CLC's pharmacy and physical therapy teams for their contributions teaching and mentoring the student teams.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Ethical Approval

The University of California, San Francisco and San Francisco VA Institutional Review Boards approved this study.

References

- 1.Paradis E, Whitehead CR. Beyond the lamppost: a proposal for a fourth wave of education for collaboration. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1457–1463. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert JHV, Yan J, Hoffman SJ. A WHO report: Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. J Allied Health. 2010;39(suppl 1):196–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siebert S, Mills V, Tuff C. Pedagogy of work‐based learning: the role of the learning group. J Workplace Learn. 2009;21(6):443–454. 10.1108/13665620910976720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris C, Blaney D. Work-based learning. In: Swanwick T, ed. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleakley A, Bligh J, Browne J. Medical Education for the Future: Identity, Power and Location. Springer; 2011:43–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giuliante MM, Greenberg SA, McDonald MV, Squires A, Moore R, Cortes TA. Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training 2.0: a collaborative team-based approach to delivering care. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(5):629–633. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1457630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould PR, Lee Y, Berkowitz S, Bronstein L. Impact of a collaborative interprofessional learning experience upon medical and social work students in geriatric health care. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):372–373. 10.3109/13561820.2014.962128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown DK, Fosnight S, Whitford M, et al. Interprofessional education model for geriatric falls risk assessment and prevention. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(4):e000417 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor D, McCaffrey R, Reinoso H, et al. An interprofessional education approach to fall prevention: preparing members of the interprofessional healthcare team to implement STEADI into practice. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;40(1):105–120. 10.1080/02701960.2018.1530226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd M, Cohen D, Harris J, Herman C, Popp J, VanLeit B. Interprofessional geriatric assessment elective for health professional students: a standardized patient case study and patient script. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9316 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulligan R, Gilmer-Scott M, Kouchel D, et al. Unintentional weight loss in older adults: a geriatric interprofessional simulation case series for health care providers. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10631 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivera J, Yukawa M, Hyde S, et al. Interprofessional standardized patient exercise (ISPE): the case of “Elsie Smith.” MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9507 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shortridge A, Steinheider B, Ciro C, Randall K, Costner-Lark A, Loving G. Simulating interprofessional geriatric patient care using telehealth: a team-based learning activity. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10415 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karpa K, Graveno M, Brightbill M, et al. Geriatric assessment in a primary care environment: a standardized patient case activity for interprofessional students. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10844 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson C, O'Brien B, Rennke S. GeriWard Falls: an interprofessional team-based curriculum on falls in the hospitalized older adult. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10410 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rennke S, Mackin L, Wallhagen M, et al. GeriWard: an interprofessional curriculum for health professions student teams on systems-based care of the hospitalized older adult. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9533 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskildsen M, Flacker J. Care transitions workshop for first-year medical students. MedEdPORTAL. 2010;6:7802 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.7802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders R, Miller K, Dugmore H, Etherton-Beer C. Demystifying aged care for medical students. Clin Teach. 2017;14(2):100–103. 10.1111/tct.12484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanter SL. The nursing home as a core site for educating residents and medical students. Acad Med. 2012;87(5):547–548. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182557445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford CR, Foley KT, Ritchie CS, et al. Creation of an interprofessional clinical experience for healthcare professions trainees in a nursing home setting. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):544–548. 10.3109/0142159X.2013.787138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kent F, Lai F, Beovich B, Dodic M. Interprofessional student teams augmenting service provision in residential aged care. Australas J Ageing. 2016;35(3):204–209. 10.1111/ajag.12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Annear MJ, Goldberg LR, Lo A, Robinson A. Interprofessional curriculum development achieves results: initial evidence from a dementia-care protocol. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(3):391–393. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1117061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annear M, Walker K, Lucas P, Lo A, Robinson A. Interprofessional education in aged-care facilities: tensions and opportunities among undergraduate health student cohorts. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(5):627–635. 10.1080/13561820.2016.1192995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Core principles of interprofessional practice. University of California, San Francisco, Program for Interprofessional Practice and Education. Accessed June 28, 2018. https://interprofessional.ucsf.edu/core-principles-interprofessional-practice [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leipzig RM, Granville L, Simpson D, Anderson MB, Sauvigné K, Soriano RP. Keeping granny safe on July 1: a consensus on minimum geriatrics competencies for graduating medical students. Acad Med. 2009;84(5):604–610. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fab70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Society of Consultant Pharmacists. Geriatric Pharmacy Curriculum Guide. 3rd ed American Society of Consultant Pharmacists; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Academy of Geriatric Physical Therapy. Essential Competencies in the Care of Older Adults at the Completion of the Entry-Level Physical Therapist Professional Program of Study. Academy of Geriatric Physical Therapy; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Framework & competencies. University of California, San Francisco, Program for Interprofessional Practice and Education. Accessed November 13, 2020. https://interprofessional.ucsf.edu/framework-competencies [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Geriatrics Society. A Pocket Guide to the AGS 2015 Beers Criteria. American Geriatrics Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tilden VP, Eckstrom E, Dieckmann NF. Development of the Assessment for Collaborative Environments (ACE-15): a tool to measure perceptions of interprofessional “teamness.” J Interprof Care. 2016;30(3):288–294. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1137891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–1134. 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Versteeg M, Steendijk P. Putting post-decision wagering to the test: a measure of self-perceived knowledge in basic sciences? Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(1):9–16. 10.1007/s40037-019-0495-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Drug Regimen Review Instructions.docx

- Patient Care Planning Slides.pptx

- ICP Meeting Preparation.docx

- ICP Team Assessment of Student Presentations.docx

- Attending Assessment of Care Plans.docx

- Team Care Plan Note Rubric.docx

- Falls in the Skilled Nursing Facility Setting.pptx

- Falls Prevention Strategy Template.docx

- Fall Focus Team Assessment.docx

- Attending Assessment of Fall Prevention Plan.docx

- Fall Prevention & Postfall Evaluation Rubric.docx

- Prerotation Survey.docx

- Postrotation Survey.docx

- Student Evaluation of Care Planning Activity.docx

- Student Evaluation of Fall Planning Activity.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.