Abstract

Introduction:

Pain management after open inguinal hernia repair has become an issue that physicians deal with on a daily basis.

Aim:

The purpose of this study was to investigate the analgesic effect of three different regimens of analgesics administered to patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair.

Methods:

A total of 259 patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair were enrolled. Patients were randomly allocated to one of three groups on admission, which would determine the prescribed post-operative analgesic regimen. Patients allocated to group A receiving a combination of 1gr/8hours intravenous (IV) acetaminophen and 50mg/6hours intramuscular (IM) pethidine, patients in group B receiving a combination of 1gr/8hours IV acetaminophen and 40mg/12hours IV parecoxib, while patients of group C received 1gr/8hours IV acetaminophen monotherapy. All patients remained overnight at the hospital and discharged the day after. Analgesic therapy was administered at regular intervals. Pain was evaluated utilizing the numeric rating scale (NRS) at 5 time points: the first assessment was done at 45 minutes, the second at 2 hours, the third at 6 hours, the fourth at 12 hours and the fifth at 24 hours post-administration. The postoperative pain intensities measured by NRS within groups and between groups at each time were analyzed using one-way repeat measured ANOVA and Post Hoc Test-Bonferroni Correlation.

Results:

The analgesic regimens of groups A and B (combination regimens consisting of IV acetaminophen and intramuscular pethidine and IV acetaminophen and IV parecoxib, respectively) were found to be of equivalent efficacy (P-value=1.000). In contrast, patients in group C (acetaminophen monotherapy) had higher NRS scores, compared to both patients in groups A (P-value<0.0001) and B (P-value<0.0001).

Conclusion:

The combinations of IV acetaminophen with either intramuscular pethidine or IV parecoxib are superior to IV acetaminophen monotherapy in achieving pain control in patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair.

Keywords: inguinal hernia repair, postoperative pain, pain score, postoperative analgesia, numerical rating score

1. INTRODUCTION

An abdominal wall hernia consists of a protrusion of intra-abdominal tissue through a fascial defect in the abdominal wall. Inguinal hernias are the most common abdominal type of hernias accounting for approximately 75% of all hernias (1). Almost one third of males are diagnosed with an inguinal hernia during their lifetime. The highest incidence in adults is after 50 years of age (2). Only 3% of women will develop an inguinal hernia. In the United States, the annual incidence of an inguinal hernia is 315 per 100,000 and surgical repair of inguinal hernias accounted for more than 48 billion dollars in 2005 health care expenditures (3). Worldwide 20 million inguinal hernia repair surgeries are performed annually (4). These numbers make the socioeconomic consequences of the most appropriate treatment strategy important to health policy makers (3). Inguinal anatomy is complicated and of essential knowledge for the general surgeon and numerous times hernia surgery represents a major challenge even for the most experienced surgeons (5). History and clinical examination usually determine the diagnosis, and no supplemental imaging is needed unless there are specific circumstances. CT imaging or ultrasound may be useful in the face of possible bowel obstruction; however, they are not required per se for surgical intervention (6, 7). There are two options for inguinal hernias repair, open and laparoscopic (8). Although open repair is still widely performed, laparoscopic repair is now known to be a safe and effective alternative, with postoperative complication rates comparable with open repair. Laparoscopy may result in a shorter hospital stay, decreased postoperative pain, and better cosmesis (9).

One of the major patient concerns undergoing inguinal hernia repair is postoperative pain and the need to return to work and daily activity as soon as possible. The goal of postoperative pain management is to reduce or eliminate pain and discomfort with the least side effects and minimal cost (10, 11). Various drugs are used for postoperative pain management. Parecoxib and acetaminophen are non-opioid analgesics with a well-documented efficacy after different surgical procedures. The use of non-opioid analgesics can reduce opioid-induced side-effects (12, 13). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit the enzymes cyclooxygenase (COX) -1 and -2. Only the inhibition of COX-2 is involved in analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic effects of NSAIDs (14).

2. AIM

This clinical study was designed to contrast the analgesic efficacy of three analgesic regimens in the setting of open inguinal hernia repair: acetaminophen monotherapy versus acetaminophen combinations with either pethidine or parecoxib. Studies investigating the analgesic effects of combined pethidine and acetaminophen have not been published so far.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

This prospective, randomized trial was conducted at the University Hospital of Patras in Greece. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. Between February 2017 and May 2019, 259 patients undergoing elective open inguinal hernia repair were enrolled in the study. All patients provided written informed consent. Inclusion criteria were age between 35 and 65 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA PS) classification I or II, and diagnosis of inguinal hernia that was scheduled to be treated by elective open inguinal hernia repair. The perception of pain in others is an important component of pain assessment and treatment. Clinical and experimental research indicates that pain is perceived, assessed, and treated differently depending on a person’s age (15). That’s why we decided to have only patients with maximum age 65 years old in our trial. In addition, ASA PS is associated with higher postoperative pain and a possible explanation is that patients with higher ASA PS are more likely to be chronically ill and have co-existent chronic pain (16). In order to have more homogenous sampling only patients with ASA PS classification I or II were enrolled in our study. Preoperative evaluation for general anesthesia was performed. Exclusion criteria were heart failure, liver failure, renal dysfunction, diabetes, severe bronchial asthma, neurological or psychiatric disease, history of chronic pain or opioid intake, difficulty in communication due to language barriers or intellectual disability, and history of adverse events after NSAIDs (acetaminophen, parecoxib) or pethidine administration. The day before surgery, the patients gave informed written consent to the study. The day prior to surgery patients were introduced to the numerical rating scale (NRS) for pain documentation.

Study setting

All participants were randomly assigned to each group before surgery, using a computer – generated random number generator and sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes. Patients in group A were randomized to receive IV acetaminophen 1000 mg every 8 hours and intramuscular pethidine 50 mg every 12 hours. Patients in group B were randomized to receive a combination of IV acetaminophen 1000 mg every 8 hours and IV parecoxib 40mg every 12 hours. Finally, patients in group C were randomized to receive IV acetaminophen 1000 mg every 8 hours only.

All operations were conducted by same group of surgeons and anesthesiologists. General anesthesia consisted of IV Remifentanil (induction 25-75 mcg and maintenance infusion 5-15 mcg/kg/min), IV Recuronium (induction 0,8 mg/kg and maintenance bolus 0,15 mg/kg and IV Propofol (induction 2 mg/kg, then initiate continuous IV infusion at 5 mg/kg/hour). All patients received IV acetaminophen 1000 mg, IV Parecoxib 40mg and intramuscular pethidine 50mg during the procedure.

Surgical technique

The open inguinal hernia repair was made by same group of surgeons. A 5 cm to 6 cm linear incision is made parallel to the inguinal ligament overlying the proposed region of the external ring. Afterwards dissection is done until the fibers of the external oblique are identified. The external oblique fascia is opened parallel to the fibers and carried through the external ring revealing the spermatic cord and possible site of a hernia. Mobilization of the spermatic cord is made by surgeon from the pubic tubercle and the hernia sac can then be identified as indirect or direct. The Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty is the preferred method of repair in our department. A mesh is used to cover the fascial defect and recreate and strengthen the inguinal floor to prevent from further hernias following repair. The external oblique fascia may be reapproximated, as per surgeon preference, as well as the re-creation of the external ring (17).

Postoperative pain assessment

In general, the procedure followed after the surgery and placement of the skin sutures, is the extubation of patients in the surgical room. Surgery information is recorded, such as surgery time, intraoperative complications, and analgesics used.

Following surgery, patients were transferred to the surgical ward. Patients were evaluated at the bedside at 45 minutes, 2 hours, 6 hours, 12 hours and 24 hours after receiving the first analgesic dose from their allocated regimen. Patients’ NRS pain ratings were recorded on postoperative monitoring charts. The scale ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 means no pain and 10 corresponds to the maximum possible pain. The reason we chose this scale is because, compared to other pain intensity scales, it is more easily applicable and understandable by the patients. Another advantage of the NRS scale, compared to other pain scales such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), is the fact that it uses more ratings (0-10), so it is a more sensitive scale in calculating the pain intensity changes that occur (18, 19).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The analysis of pain scores was expressed as mean and 95% confidence interval. The postoperative pain intensities measured by NRS within groups and between groups at each time interval were analyzed using one-way repeat measured ANOVA and Post Hoc Test-Bonferroni Correlation. P-values less than 0,05 were considered significant. All statistical data were analyzed using the Stata 13 statistical software.

4. RESULTS

Patient characteristics

In total, 259 patients fulfilled the study criteria and were enrolled. Interestingly enough, all patients happened to be men similar in age and operative time. The patients’ demographic data are shown in Table 1. No intra-operative complications were recorded.

Table 1. Patients’ demographic and perioperative data.

| Group A Paracetamol and Pethidine |

Group B Paracetamol and Parecoxib |

Group C Paracetamol (Monotherapy) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 103 | 94 | 62 |

| Males/Females (n) | 103/0 | 94/0 | 62/0 |

| Mean age (years) | 55 (36-65) | 52 (35-61) | 49 (38-57) |

| Hospitalization (days)± sd | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Intraoperative complications (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean operative time (minutes) ± sd | 55.2±8.8 | 59.7±12.6 | 58.5±9.3 |

| Dosage | Paracetamol 1gr./8h Pethidine 50mg/6h |

Paracetamol 1gr./8h Parecoxib 40mg/12h |

Paracetamol1gr./8h |

| Data presented as number of cases (n) or as mean ± sd | |||

Postoperative pain assessment

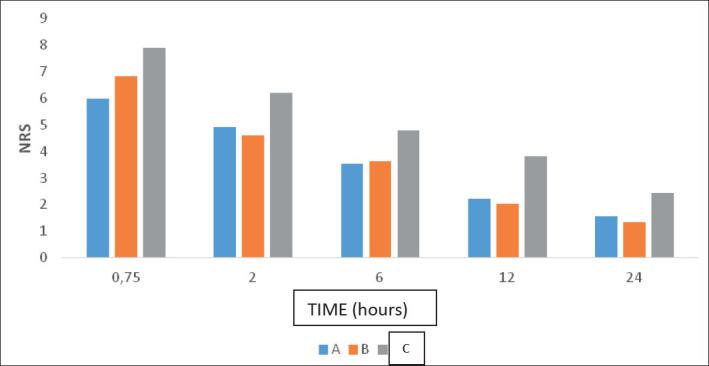

The mean NRS for patients that were treated with IV paracetamol and IM pethidine (Group A) were 5.99 at 45 minutes (0.75 hours), 4.93 at 2 hours, 3.54 at 6 hours, 2.24 at 12 hours and 1.53 at 24 hours. The mean NRS for patients that were treated with IV paracetamol and IV parecoxib (Group B) were 6.87 at 45 minutes (0.75 hours), 4.66 at 2 hours, 3.61 at 6 hours, 2.02 at 12 hours and 1.39 at 24 hours, while the mean NRS for patients that were treated with only IV paracetamol (Group C) were 7.91 at 45 minutes (0.75 hours), 6.23 at 2 hours, 4.84 at 6 hours, 3.89 at 12 hours and 2.40 at 24 hours (Figure 1). The NRS scores of group C (paracetamol monotherapy) were significantly higher than those of groups A (pethidine + paracetamol, p < 0,0001) and B (paracetamol + parecoxib, p< 0,0001), while there was no significant difference between patients of group A and group B (p = 1.00).

Figure 1. MeanNRSbetween patients of group A, B or C based on time. The data were processed usingstata 13. The data were processed usingstata 13. Group A: paracetamolandpethidine, Group B: paracetamolandparecoxib, GroupC: paracetamol (monotherapy).

5. DISCUSSION

The reduction of opioid requirements using postoperative non-opioid analgesics in patients after surgery is very important in reducing sedation, impaired pulmonary function and constipation (20).

In our study, we investigated the influence of paracetamol and its combination with parecoxib and pethidine on postoperative pain control in a randomized, controlled trial. Patients included in this analysis underwent an open inguinal hernia repair under general anesthesia using standardized surgical and anesthetic technique. The results of this randomized, prospective study suggest that the combination of postoperative analgesic treatment with acetaminophen and parecoxib is equivalent to the combination of acetaminophen and pethidine. Both combinations were found to be superior to acetaminophen monotherapy in achieving pain control in patients with open inguinal hernia repair and should therefore be preferred in this setting. Furthermore, since these two regimens of analgesics appear to have similar efficacy, the combination of acetaminophen and parecoxib should be preferred over acetaminophen and pethidine, in order to reduce opioid consumption and associated adverse events (21, 22).

There is a trial in which it is compared the analgesic effects of lornoxicam (NSAID) and tramadol (opioid) in patients after open inguinal hernia repair. According to that randomized and prospective study in which VAS score was used, loronoxicam 8mg i.v. and b.i.d., tramadol 1mg/kg at the end of surgery and every 6 hours up to 24 hours after inguinal hernia repair provided rapid and effective analgesia and was well tolerated (23). However, studies investigating the analgesic effect of combined pethidine/acetaminophen and parecoxib/acetaminophen have not been published so far.

One limitation of this study that should be considered is that we did not record data during mobilization, as pain scores were recorded only at rest. The pain rating at rest alone is not very helpful as it is the functional outcome that is of clinical interest. Evaluation of pain during movement is suggested for further study (24).

6. CONCLUSION

The combination of postoperative analgesic treatment of IV paracetamol and IV parecoxib IV is equivalent to the combination of IV paracetamol and intramuscular pethidine in patients undergoing open inguinal hernia repair. Both combinations of postoperative analgesics outweigh the paracetamol monotherapy and should therefore be preferred in open inguinal hernia repair. Furthermore, our study confirms the notion of a significant opioid-sparing effect of parecoxib in postoperative pain management after open inguinal hernia repair.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the family involved in this study for their collaboration and Prof Dr Orhan Uzun in the editing and critical approval of this manuscript.

Patients Consent Form:

Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s parents for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Author contributions:

Each author gave substantial contribution to the conception, in design of in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the article. Each author had role in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Conflict of interest:

None declared.

Financial support and sponsorship:

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Read RC. Herniology: past, present, and future. Hernia. 2009 Dec;13(6):577–80. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berndsen MR, Gudbjartsson T, Berndsen FH. Laeknabladid. 2019;105(9):385–391. doi: 10.17992/lbl.2019.09.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroeder AD, Tubre DJ, Fitzgibbons RJ., Jr Watchful Waiting for Inguinal Hernia. Adv Surg. 2019;53:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgibbons RJ, Ramanan B, Arya S, et al. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann Surg. 2013;258:508–515. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a19725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachul P, Tomaszewski KA, Kmiotek EK, Kratochwil M, Solecki R, Walocha JA. Anatomic variability of groin innervation. Folia Morphol. (Warsz) 2013 Aug;72(3):267–270. doi: 10.5603/fm.2013.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinclair P, Kadhum M, Bat-Ulzii Davidson T. A rare case of incarcerated femoral hernia containing small bowel and appendix. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Aug 09;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, Tang J. [China Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Groin Hernia (2018 edition)] Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018 Jul 25;21(7):721–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Payiziwula J, Zhao PJ, Aierken A, Yao G, Apaer S, Li T, Tuxun T. Laparoscopy Versus Open Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia Repair in Octogenarians: Single-Center Experience With World Review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019 Apr;29(2):138–140. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdulhai S, Glenn IC, Ponsky TA. Inguinal Hernia. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(4):865–877. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr DB, Goudas LC. Acute pain. Lancet. 1999;353:2051–2058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:62–72. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng A, Parker J, Toogood L, Cotton BR, Smith G. Does the opioid-sparing effect of rectal diclofenac following total abdominal hysterectomy benefit the patient? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 88(5):714–716. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.5.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iohom G, Walsh M, Higgins G, Shorten G. Effect of perioperative administration of dexketoprofen on opioid requirements and inflammatory response following elective hip arthroplasty. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 88(4):520–526. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munsterhjelm E, Niemi TT, Ylikorkala O, Neuvonen PJ, Rosenberg PH. Influence on platelet aggregation of i.v. parecoxib and acetaminophen in healthy volunteers. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 97(2):226–231. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wandner LD, Scipio CD, Hirsh AT, Torres CA, Robinson ME. The perception of pain in others: how gender, race, and age influence pain expectations. J Pain. 2012;13(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinjo S, Sands LP, Lim E, Paul S, Leung JM. Prediction of postoperative pain using path analysis in older patients. J Anesth. 2012;26(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassler KR, Baltazar-Ford KS. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Jan, Open Inguinal Hernia Repair. [Updated 2020 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459309/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firdous Shagufta, Mehta Zankhana, Fernandez Carlos, Behm Bertarnd, Davis Mellar. A comparison of Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) in patients with chronic cancer-associated pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(31_suppl):217–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.31_suppl.217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagliese L, Weizblit N, Ellis W, Chan VW. The measurement of postoperative pain: a comparison of intensity scales in younger and older surgical patients. Pain. 2005 Oct;117(3):412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.004.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehling M, Arndt C, Eberhart LHJ, Koch T, Kruger T, Wulf H. Postoperative analgesia with parecoxib, acetaminophen, and the combination of both: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients undergoing thyroid surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 104(6):761–767. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nong L, Sun Y, Tian Y, Li H. Effects of parecoxib on morphine analgesia after gynecology tumor operation: a randomized trial of parecoxib used in postsurgical pain management. Surg Res. 2013 Aug;183(2):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.02.059. Published online 2013 Mar 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu Weihua, Yao Jiwei, Li Qianwei, Wang Yongquan, Wu Xiaojun, Zhou Zhansong, Li Wei-Bing, Yan Jun-An. Cell Efficacy and safety of parecoxib/phloroglucinol combination therapy versus parecoxib monotherapy for acute renal colic: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. BiochemBiophys. 2014 May;69(1):157–161. doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9782-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mentes O, Bagci M. Postoperative pain management after inguinal hernia repair: lornoxicam versus tramadol. Hernia. 2009;13:427. doi: 10.1007/s10029-009-0486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen SJ, Peng PY, Chen HP, Lin JR, Lee MS, Yu HP. Analgesic Effects of Intra-Articular Bupivacaine/Intravenous Parecoxib Combination Therapy versus Intravenous Parecoxib Monotherapy in Patients Receiving Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2015:450805. doi: 10.1155/2015/450805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]