Abstract

Bioink printability persists as a limiting factor toward many bioprinting applications. Printing parameter selection is largely user-dependent, and the effect of cell density on printability has not been thoroughly investigated. Recently, methods have been developed to give greater insight into printing outcomes. This study aims to further advance those methods and apply them to study the effect of printing parameters (feedrate and flowrate) and cell density on printability. Two printed structures, a crosshatch and five-layer tube, were established as printing standards and utilized to determine the printing outcomes. Acellular bioinks were printed using a testing matrix of feedrates of 37.5, 75, 150, 300, and 600 mm/min and flowrates of 21, 42, 84, 168, and 336 mm3/min. Structures were also printed with cell densities of 5, 10, 20, and 40 × 106 cell/mL at 150 mm/min and 84 mm3/min. Only speed ratios (defined as flowrate divided by feedrate) from 0.07 to 2.24 mm2 were suitable for analysis. Increasing speed ratio dramatically increased the height, width, and wall thickness of tubular structures, but did not influence radial accuracy. For crosshatch structures, the area of pores and the frequency of broken filaments were decreased without impacting pore shape (Pr). Within speed ratios, feedrate and flowrate had negligible, inconsistent effects. Cell density did not affect any printing outcomes despite slight rheological changes. Printing outcomes were dominated by the speed ratio, with feedrate, flowrate, and cell density having little impact on printing outcomes when controlling for speed ratio within the ranges tested. The relevance of these results to other bioinks and printing conditions requires continued investigation by the bioprinting community, as well as highlight speed ratio as a key variable to report and suggest that rheology is a more sensitive measure than printing outcomes.

Impact statement

Cell-based 3D bioprinting strategies have a great promise to bioengineer clinically relevant tissue constructs. A better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that affect the printability of cell-laden hydrogel bioinks is mandatory. This study investigated the effects of printing parameters and cell density on the printing outcomes, which could provide a significant impact on further bioink development and bioprinting applications.

Keywords: bioprinting, bioink, hydrogel, cell density, federate, flowrate, printability

Introduction

Bioprinting is an advantageous manufacturing technique for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications due to its ability to create complex structures, its capacity for incorporating multiple materials, and its potential to create patient-specific geometries, among other factors.1–6 The aim of bioprinting is the precise deposition of bioinks to manufacture constructs with the desired geometries.2,7–9 Imprecise deposition can result in a number of errors, including closed pores and broken filaments. Small errors early in a print can propagate over many layers, failing the entire print, a highly undesirable result given the expense of biomaterials, cells, and bioactive molecules typically used in bioprinting. In addition, the size and shape of a construct can influence its biological activity by affecting properties such as the number of cells delivered and the release kinetics of bioactive molecules. However, much remains unknown about the various constraints which exist on bioprinting systems, with researchers currently relying on trial and error or personal experience for many aspects.10,11

Currently, researchers often assess printing outcomes qualitatively,12,13 or with basic quantitative measures such as a filament width.10,14,15 These measures are insufficient for demonstrating outcomes in the more complex structures typically used, omitting features such as sharp and curved turns, pores, and multilayer stacking. Thus, several methods have been developed to analyze printing outcomes for bioprinting applications.16,17 The field would benefit from further validation and development of these novel techniques. In addition, they may prove to be highly beneficial for examining the various relationships between different printing system parameters and the subsequent printing outcomes.

Printing conditions are an important parameter, which researchers must make decisions on with limited information. It is well known that the feedrate (also referred to as the print speed) and the flowrate are the primary parameters that significantly affect material deposition. Higher feedrates and lower flowrates result in the lower material deposition, thinner filaments, and a higher potential for broken filaments. Meanwhile, lower feedrates and higher flowrates result in higher material deposition and thicker filaments, which can be problematic if designed pores are filled closed or material deposition exceeds the layer height.18–25 Ultimately, higher feedrates are desired to decrease the total print time. It is common practice to compensate for higher feedrates by proportionally increasing the material flowrates, but lower feedrates are also generally desired to minimize damage to the cells. The ratio of flowrate (mm3/s) to feedrate (mm/s) can be referred to as the speed ratio (mm2) and hypothetically represents the cross-sectional area of the printed filaments. Previous investigations into feedrate and flowrates on printing outcomes have only looked at filament height and width18–25 and have not examined more complex structures. In addition, they neither examined the speed ratio nor to what extent the compensatory relationship between feedrate and flowrate is able to maintain desirable printing outcomes.

Cell density is another important design criterion when developing a bioink. High cell densities have been shown to be beneficial for some tissue applications such as cartilage; however, the influence of cells on bioink printability is not fully understood, and only a few studies have been conducted. Some results suggest that an increasing cell density increases a bioink's viscosity,26,27 while others have seen a decrease in viscosity as well as storage modulus (G′), yield stress, and gelation kinetics.14,28 However, the relationship between rheological properties and printing outcomes is not fully understood, adding to the difficulty of interpreting what these results signify for bioink printability. Further studies are ultimately needed to determine how cell density may influence printing outcomes.

In this study, gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) and gellan gum (GG) are selected. GelMA is the most commonly used hydrogel in bioprinting, which has been shown to have good biological properties. Furthermore, the methacrylate double bonds allow for UV-crosslinking, which can increase its structural integrity during the printing process and subsequent culture. However, when printed alone, very high concentrations of GelMA must be used to achieve appropriate printability29–33 GG is a thermos-responsive, naturally derived polysaccharide that has also shown significant promise in bioprinting applications. GG can complement GelMA when used in combination, acting as a viscosity enhancer to improve printability and reducing construct shrinkage during crosslinking and culture. GG also shows stiffness and degradation properties that are favorable for tissue engineering and can be tuned for specific applications.34–39 We utilize novel printability assessment techniques to study the effect of feedrate, flowrate, speed ratio, and cell density on various printing outcomes using this GelMA/GG composite bioink (Fig. 1).

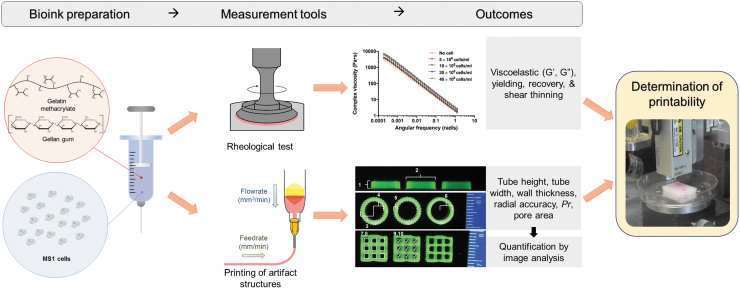

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of speed ratio and cell density experiments. GelMA/GG composite bioinks were prepared for use in both experiments and tested both rheologically and by printing five-layer tube and crosshatch structures. The effect of printing conditions was examined by using a testing matrix of different feedrates and flowrates. For cell density experiments, MS1 cells were also included in the bioink at various cell densities. GelMA, gelatin methacrylate; GG, gellan gum.

Materials and Methods

Bioink preparation

All chemicals were purchased from Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. For this experiment, a composite bioink of GelMA and GG was utilized. In brief, GelMA was synthesized by adding methacrylate anhydride to a gelatin solution as described previously.30 Next, 1.2% w/v GG (G1910) and 10% v/v glycerol (G6279) were dissolved in an 80°C oil bath under magnetic stirring for 15 min. The bath was then changed to 60°C, and 4% w/v GelMA was added and stirred for 20 min or until fully dissolved. Although an aseptic technique was not observed for this study, the formulation was filtered to mimic conditions for cell applications. Whatman syringe filters (0.45 μm; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA), which were prewarmed to prevent rapid gelation within the filter, were used. Finally, fluorescein dye (46955) was aliquoted and then added to the bioinks for a final concentration of 0.01 mg of dye per milliliter of bioink. After transferring to the printing syringe, the formulation was placed in ice water for 5 min and then equilibrated for 10 min at 19°C.

Printability measurements

Printability tests were conducted on the custom-built Integrated Tissue-Organ Printer (ITOP) system.1 In brief, the ITOP system utilizes an XYZ stage/controller, dispensing module, and a closed chamber. A three-axis stage system and motion controller were used to control printing paths for the dispensing nozzle (Aerotech, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). A precision pneumatic pressure controller, temperature-controlled sleeve, syringe, and 330-μm cylindrical nozzle (Musashi Engineering, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) comprised the dispensing module. Finally, an acrylic enclosure was used to create a closed-chamber system and equipped with an environmental temperature controller (EIC Solutions, Inc., Warminster, PA). Printing parameters such as nozzle path, feedrate, and pressure were specified in a custom text-based motion program. This program was then transferred to the operating computer for the printing process. Flowrate was determined by extruding the bioink for ∼30 s, weighing the extrudate, dividing weight by extrusion time, and finally converting to volume by assuming a density of 1 mg/mm3. The pressure was then adjusted until the desired flowrate was achieved. The layer heights were based on the speed ratio for each condition with layer heights of 0.15, 0.21, 0.32, 0.42, 0.53, and 0.75 mm corresponding to speed ratios of 0.07, 0.14, 0.28, 0.56, 1.12, and 2.24 mm2, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Testing Printing Conditions; Feedrates, Flowrates, and Speed Ratios

| Speed ratio, mm2 | Flowrate, mm3/min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 42 | 84 | 168 | 336 | ||

| Feedrate, mm/min | 37.5 | 0.56 | 1.12 | 2.24 | 4.48 | 8.96 |

| 75 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 1.12 | 2.24 | 4.48 | |

| 150 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 1.12 | 2.24 | |

| 300 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 1.12 | |

| 600 | 0.035 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.56 | |

For printability assessment, a five-layer tube structure was modified from a previous study.17 The five-layer tube was printed with a radius of 4 mm to assess multilayer stacking and arced printing paths. This structure was photographed from the side, and both the height and width of the structure were measured. Height was taken as an average across the middle 75% of the structure to exclude variation at the tube walls. The width was taken as a maximum at the base of the structure. The five-layer tube was also photographed from above. The area inside the internal and external edges of the tube was measured. External and internal radii were then calculated from the area by assuming the object to have a circular shape. Wall thickness was then taken as the difference between internal and external radii. Finally, radial accuracy was calculated as the average between internal and external radii, taken as a percentage of the designed radius.

A second structure, first developed by Ouyang et al.,16 was also adapted and printed for this study. A zigzag pattern with a line pitch of 2.67 mm was rotated 90° between the first and second layers, creating a crosshatch structure with 9 square pores. This structure was photographed from above and both pore area and Pr value were measured from each pore. Pores with an area of 0 were considered to be “filled,” while pores which could not be measured due to broken filaments on one or more of its edges were considered “broken.” For all complete, unfilled pores, Pr was calculated as:

where L is the perimeter length of the pore and A is the area of the pore. This equation gives values less than 1 for pores, which are more circular in nature (minimum value of π/4), values equal to 1 for square pores, and values greater than 1 for square pores with a nonuniform perimeter. Both structures were printed in triplicate for each condition. All measures were taken using a custom image analysis program written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Effect of printing conditions on printing outcomes

A testing matrix of different feedrates, flowrates, and nozzle heights was tested using the GelMA/GG composite bioink. Feedrates were tested at 37.5, 75, 150, 300, and 600 mm/min, and flowrates were tested at 21, 42, 84, 168, and 336 mm3/min. These combinations resulted in speed ratios ranging from 0.035 to 8.96 mm2 (Table 1). However, meaningful measurements could not be made from structures printed with a speed ratio of 0.035 mm2 due to under-deposition. Similarly, measurements could not be made from structures printed at speed ratios of 4.48 or 8.96 mm2 due to over-deposition. In this experiment, measured feedrate/flowrate combinations included speed ratios of 0.07 (2 combinations), 0.14 (3 combinations), 0.28 (4 combinations), 0.56 (5 combinations), 1.12 (4 combinations), and 2.24 (3 combinations).

Effect of cell density on printing outcomes

The GelMA/GG composite bioink was used to investigate the effect of cell density on printing outcomes. Endothelial murine cells (MS1, CRL-2279; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were expanded in 2D culture in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10% v/v), and a solution of penicillin/streptomycin (1% v/v). MS1 cells were then trypsinized and mixed into the bioink at a ratio of 0, 5, 10, 20, or 40 × 106 cells/mL. For each cell density, the bioink was then used to print the two structures using a feedrate of 150 mm/s and the pressure required to achieve a flowrate of 1.4 mm3/s (210–240 kPa).

In addition, simultaneous rheological measures were conducted in triplicate on all cell densities of the bioink using a Discovery Hybrid Rheometer-2 (TA Instruments, Wilmington, DE). For each test, a cone-plate geometry with a 40-mm diameter, a gap of 100 μm, and a slope of 1° were used. Frequency sweeps were conducted from 0.01 to 100 Hz using a logarithmic sweep with 10 points per decade at a strain of 0.2%. Shear rate and complex viscosity were then fitted to the power-law equation:

where is the shear rate, is the viscosity as measured by the rheometer, and K and n are estimated constants known as the consistency index and flow index, respectively. Strain sweeps were conducted from 0.1% to 1000% using a logarithmic sweep with 10 points per decade at a frequency of 1 Hz. Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were averaged at low strains within the bioink's linear viscoelastic region. As strain increased, yield stress was defined as the stress at the crossover point between G′ and G″.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with JMP 13 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) using an α level of 0.05. Unless otherwise noted, all comparisons were made via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If statistical differences were detected, a post hoc analysis was conducted via Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference between means for all data combinations.

Results

Effect of speed ratio on printing outcomes

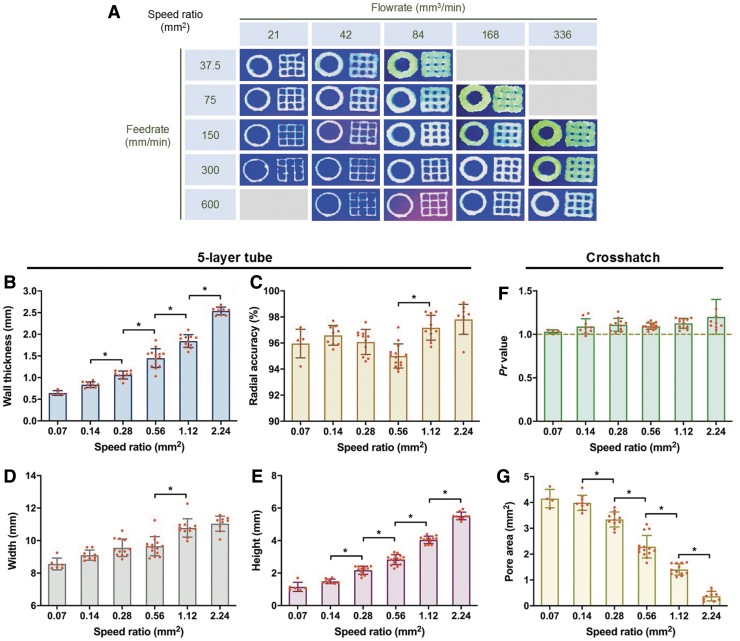

For each measure, data were grouped by speed ratio, regardless of feedrate/flowrate. As a result, the speed ratio was seen to have a major effect on all measures except Pr value and radial accuracy. However, excluding broken pores, no differences were seen between the lowest speed ratios of 0.07 and 0.14 mm2 (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

(A) Representative images from different printing conditions. (B–G) Quantitative measures taken from five-layer tube and crosshatch structure, grouped by speed ratio, including (B) wall thickness, (C) radial accuracy, (D) tube width, (E) tube height, (F) Pr value, and (G) pore area. * Denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05). All data are represented as mean ± SD. SD, standard deviation.

From the five-layer tube, external radius increased by 1.02 mm and internal radius decreased by 0.87 mm as speed ratio increased from 0.07 to 2.24 mm2. As a result, wall thickness subsequently increased by a value of almost 2 mm (Fig. 2B). All three measures showed significant differences between all speed ratios except 0.07 and 0.14 mm2. Despite these changes, very few differences were measured in radial accuracy. The radius of the wall's centerline decreased slightly from 0.07 to 0.54 mm2 and then increased from 0.54 to 2.24 mm2 (Fig. 2C).

The height of the structure increased dramatically from 1.14 to 5.52 mm as speed ratio increased from 0.07 to 2.24 mm2. Changes in width were more moderate, ranging from 8.54 to 11.04 mm (Fig. 2D, E). Differences in height were detected between all speed ratios except 0.07 and 0.14 mm2, while most measures of width showed similarity between adjacent speed ratios.

From the crosshatch structure, filled pores were seen only at a speed ratio of 2.24 mm2. Broken pores occurred at speed ratios as high as 0.56 mm2, but not at a significant frequency until 0.14 mm2. The occurrence of broken pores increased dramatically from a speed ratio of 0.14 to 0.07 mm2. Pr showed no trends across speed ratios (p = 0.11), ranging from 1.03 to 1.14 (Fig. 2F). Conversely, pore area decreased from a value of 4.15 to 0.37 mm2 as speed ratio increased from 0.07 to 2.24 mm2. Statistically significant differences between all speed ratios were detected except between 0.07 and 0.14 mm2 (Fig. 2G). Supplementary Table 1 lists all values from the printability measures made from bioinks with speed ratios.

Effect of feedrate/flowrate on printing outcomes

Because of the predominant effect speed ratio has on printing outcomes, feedrate and flowrate were examined within each speed ratio. This analysis was used to determine if these variables had any effect on printing outcomes independent of the speed ratio. Among these variables (speed ratio, feedrate, and flowrate), conditions are fully defined using only two of the three. As a result, only speed ratio and feedrate were used for the analysis, although an equivalent analysis could have been conducted using the corresponding flowrates instead of feedrates.

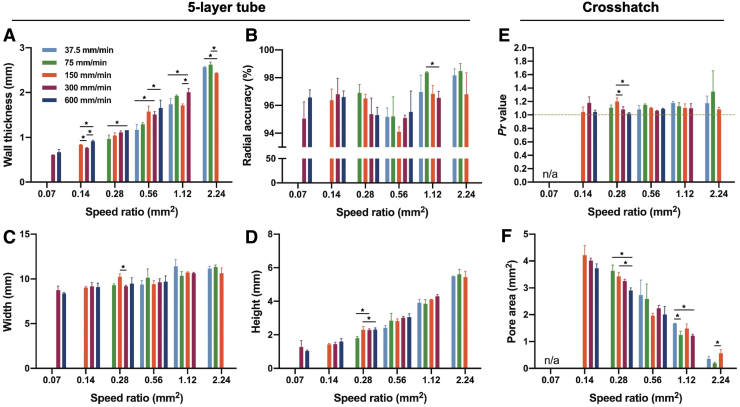

Some minor trends were observed from the five-layer tube structures, as viewed from above. External radius was increased at 0.56 mm2 for 600 mm/min relative to 27.5 mm/min, at 1.12 mm2 for 75 mm/min relative to 150 mm/min, and at 2.24 mm2 for 37.5 and 75 mm/min relative to 150 mm/min. Internal radius was decreased at 0.28 mm2 for 600 and 300 mm/min relative to 75 mm/min, at 0.56 mm2 for 150, 300, and 600 mm/min relative to 37.5 mm/min, and at 1.12 mm2 for 300 mm/min relative to 37.5, 75, and 150 mm/min. These differences amounted to a maximum of ∼0.2 mm. Tube thickness showed similar trends to internal and external radius (Fig. 3A) with outcome ranges between feedrates as high as 0.5 mm. Meanwhile, radial accuracy showed no differences between feedrates except an elevated accuracy at 1.12 mm2 for 75 mm/min relative to 300 mm/min (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Quantitative measures taken from five-layer tube and crosshatch structures at different feedrates and speed ratios, including (A) wall thickness, (B) radial accuracy, (C) tube width, (D) tube height, (E) Pr value, and (F) pore area. *Denotes statistical significance (p < 0.05). All data are represented as mean ± SD.

As viewed from the side, even fewer differences were seen between feedrates for the five-layer tube. Height was reduced at 0.28 mm2 for 75 mm/min relative to 150 and 300 mm/min, but no other differences were detected. No differences were observed between feedrates for width measurements for any speed ratio (Fig. 3C, D).

Finally, filled pores, broken pores, Pr, and pore area were examined for crosshatch structures. Filled pores, which only occurred at a speed ratio of 2.24 mm2, did not show any differences between feedrates of 37.5, 75, and 150 mm/min (p = 0.158). Frequency of broken pores did not show any differences between feedrates at speed ratios of 0.07 (p = 0.660), 0.14 (p = 0.065), 0.28 (p = 0.219), or 0.56 (p = 0.171) mm2. At 0.14 mm2, which was trending toward significance, broken filaments occurred on 33.3% (standard deviation 19.2%) of all pores printed at 600 mm/min, while only on 7.4% (standard deviation 6.4%) for both 300 and 150 mm/min structures.

Pr and pore area comparisons were not able to be made at 0.07 mm2 due to a lack of unbroken pores. Pr values, which did not show any trends across speed ratios, also showed very little variation across feedrates within speed ratios. An elevated Pr was detected at 0.28 mm2 for 150 mm/min relative to 300 and 600 mm/min, but no other significant differences were found (Fig. 3E). Pore area was increased at 0.28 mm2 for 75 and 150 mm/min relative to 600 mm/min, at 1.12 mm2 for 37.5 mm/min relative to 75 and 300 mm/min, and at 2.24 mm2 for 150 mm/min relative to 75 mm/min. These differences in pore area ranged as high as 0.6 mm2 (Fig. 3F).

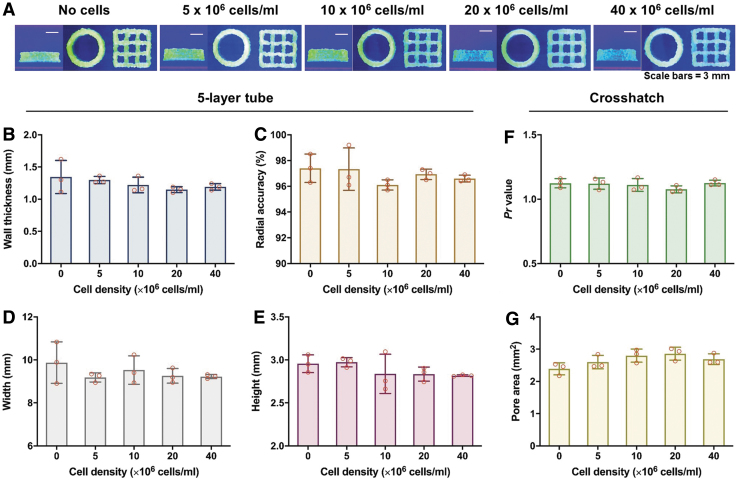

Effect of cell density on printing outcomes

Both structures were successfully printed at each cell density (Fig. 4A). External radii, internal radii, wall thickness, and radial accuracy ranged between cell densities by 0.12 mm, 0.08 mm, 0.19 mm, and 1.32%, respectively. Similarly, tube height had a range of 0.16 mm and tube width had a range of 0.69 mm. No broken filaments or filled pores occurred at any cell density. Finally, Pr ranged by a value of 0.05 and pore area by a value of 0.47 mm2. No statistical differences were detected between the bioinks for any measure, up to a density of 40 × 106 cells/mL (Fig. 4B–G).

FIG. 4.

(A) Photographs grouped by bioink of the crosshatch structure (left), five-layer tube—top view (center), and five-layer tube—side view (right). Labels indicate the cell density of each bioink and scale bars represent 3 mm. Quantitative measures taken from five-layer tube and crosshatch structures at different cell densities, including (B) wall thickness, (C) radial accuracy, (D) tube width, (E) tube height, (F) Pr value, and (G) pore area. All data are represented as mean ± SD.

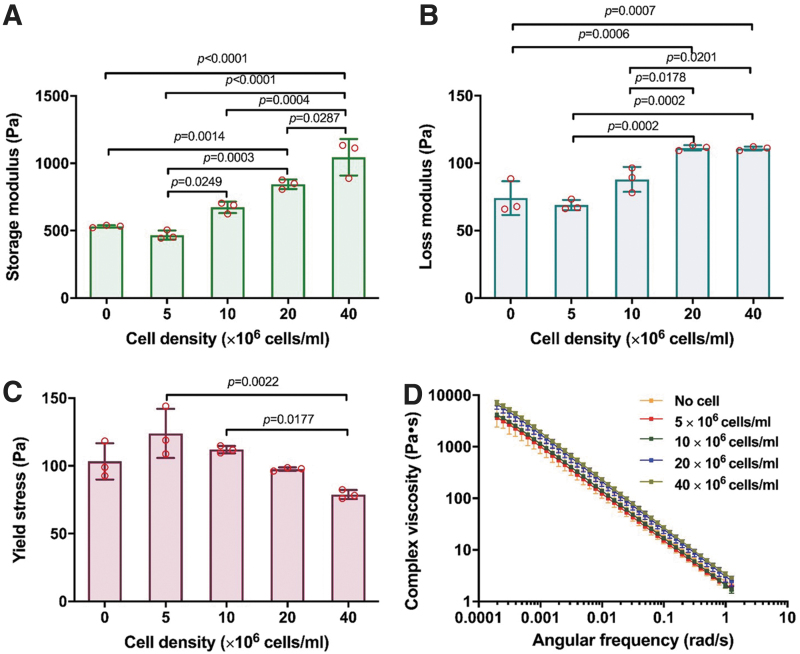

However, rheological measures did show some variation between the bioinks with different cell densities. Both storage modulus (Fig. 5A) and loss modulus (Fig. 5B) increased moderately as cell density increased, with 20 × 106/mL and 40 × 106/mL resulting in statistically significant differences from the acellular bioink. Yield stress showed slight changes, initially increasing as cells were introduced at 5 × 106/mL and then decreasing from there as cell density increased (Fig. 5C). Finally, all bioinks showed similar shear-thinning abilities with analogous K and n constants (Fig. 5D). Supplementary Table 2 lists all values from the printability measures made from bioinks with cell densities.

FIG. 5.

Rheological results from strain sweep and frequency sweep tests of bioinks with varying cell densities, including (A) storage modulus, (B) loss modulus, (C) yield stress, and (D) shear-thinning behavior. All data are represented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated the effects of printing parameters (feedrate, flowrate, and speed ratio) and cell density on printability, while simultaneously validating previously published printability measures and introducing several new measures. Speed ratio relationships were largely predictable based on common knowledge and experience of the printing process. These results indicate both that the measurement methodology was at least moderately accurate and that the various measurements presented are useful for detecting differences in printing outcomes. In addition, while the effect of speed ratio on printing outcomes is intuitive, it has not previously been reported. There is value in the occasional testing of well-accepted assumptions. More importantly, these effects have been quantified for the first time, which could serve as the basis for future decision-making with respect to printing parameter selection. These results may also prove valuable as a starting point for future model development, allowing for a more accurate prediction of printing outcomes.

Furthermore, the influence of speed ratio on some measures such as Pr and radial accuracy was not previously known. However, no change in Pr value was seen regardless, of which printing condition was examined. Similarly, very small differences were observed between speed ratios for radial accuracy which, if anything, increased as speed ratio increased. The finding that no speed ratio resulted in exact radial accuracy also provides some insight that could potentially be useful in the design of printing paths. In this study, measured radii were 0.1–0.2 mm lower than the designed path. While not imperative for most applications, if such high accuracy is desired, it may be beneficial to intentionally design arced paths to be slightly wider in anticipation of this outcome.

Along similar lines, it is important to note that the goal of this study was not to identify an ideal speed ratio. The best speed ratio for a given application is the one that achieves the desired final printing outcomes. No designed dimensions for measures such as wall thickness, pore area, tube height, etc. were specified in this study. The notable exceptions to this include Pr (a value of 1), radial accuracy (100%), closed pores (none), and broken pores (none). Pr and radial accuracy were not largely influenced by speed ratio, but the number of filled and broken pores was. For this crosshatch design, a speed ratio of 2.24 mm2 would clearly not be usable in applications, where patent pores were desired because many pores would be closed or nearly closed. That is not to say that this speed ratio is always unacceptable. Pores would have remained acceptably open had a wider line pitch been used, as it might in other applications. Broken pores, however, are undesirable irrespective of the application, ruling out speed ratios of 0.14 mm2 and lower for future work with this bioink.

Previous studies have shown that both increasing pressure and decreasing feedrate increase the height and width of printed filaments, consistent with the results of this study.18–23,25 However, previous studies did not look at more complex measures of printing outcomes, nor did they investigate the speed ratio. Looking within these speed ratios was a novel line of investigation for this study, but the results were less straightforward. Small differences between different feedrates/flowrates were detected within speed ratios. If printing outcomes depend not just on the speed ratio, but the feedrate and flowrate as well, one might expect to see these differences primarily at the extremes such as with high feedrate (600 mm/min), high flowrate (336 mm3/min) combination used in this study. Another possibility would be for feedrate and flowrate to effect printing outcomes across all ranges. In this case, it might be expected for these effects to have similar trends across speed ratios. However, the relationships seen in this study neither occurred exclusively at the extremes nor were consistent across different speed ratios.

Several factors could have played a role to cause small variations between different feedrates, including differences in image segmentation, small errors in pixel to mm conversion, or an inconsistent flowrate of the gelatin-based bioink. Regardless of the cause, the effects of feedrate and flowrate independent of speed ratio are very minor relative to those of speed ratio itself for the range used in this study (37.5–600 mm/min). Rather than printing dimensions, it seems likely that the upper limitation on feedrate and flowrate should be determined in most cases by the maximum shear stresses and extrusion forces which can be tolerated by cells.26,40–42 Furthermore, most researchers have published the feedrate and pressure used in their studies, but rarely included speed ratio or flowrate.20 Given the importance of speed ratio relative to feedrate and flowrate in determining the final printing outcomes, it should be reported in most, if not all studies. This would facilitate a more detailed interpretation of a study's results and allow for easier replication of the conditions used in that study.

Further conclusions and implications can be drawn with respect to cell density experiments. Up to 40 × 106 cells/mL, the inclusion of cells did not appreciably influence any of the printing outcomes reported in this study, although interestingly, slight rheological differences were detected between bioinks. This suggests that rheology is a more sensitive measure to changes in bioink properties relative to the various printability measures used.

Most previous studies looking at the influence of cell density on hydrogel behavior have only examined density as high as 10 × 106 cells/mL and did not look at printability directly, examining rheological properties instead.26–28 A recent study by Diamantides et al.14 provides one exception to this, testing a density up to 100 × 106 cells/mL and looking at filament width as a printing outcome. In that study, the inclusion of cells in their collagen-based bioink reduced line width at cell densities as low as 5 × 106 cells/mL. One possible explanation for the contradiction in this study is the difference between bioinks. In their study, collagen was printed in the solution phase onto a 37°C plate, which then induced gelation. The addition of cells likely increased the viscosity of collagen before gelation, reducing the amount of spread upon deposition. Meanwhile, our bioink underwent thermogelation before extrusion, limiting the effect of the cells on the bioink's behavior.

Finally, caution should be used when applying any of these findings to other bioinks and printing conditions. Other bioinks may perform better or worse than the GelMA/GG formulation used in this study. They may fracture more or less easily at low-speed ratios, sag and fill pores more easily, or have their properties more influenced by the inclusion of cells. The relationships of other printing conditions such as layer height and nozzle height to bioink printing outcomes likely also play a role.25 The relationship between nozzle size and speed ratio in particular is not known. It seems logical that larger nozzle sizes will be better suited to handle higher speed ratios and vice versa, but this effect is yet to be determined. The methodology demonstrated in this study can serve as a starting point for creating a holistic guideline for printing other materials.

Conclusion

The effects of feedrate, flowrate, speed ratio, and cell density on printing outcomes have been investigated in the GelMA/GG composite bioink. Increasing speed ratio was found to dramatically increase the height, width, and wall thickness of a five-layer tube structure without influencing radial accuracy. Similarly, the area of pores in a crosshatch structure was decreased to a high degree without changing the Pr value. Speed ratio accounted for most, if not all, changes in printing outcomes brought on by feedrates as low as 37.5 and as high as 600 mm/min and flowrates as low as 0.35 and as high as 5.6 mm3/min. By the same measures, no effect was seen for cell densities up to 40 × 106 cells/mL. These results lay the groundwork to assist bioprinting researchers in the selection and optimization of printing parameters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jihoon Park for bioink preparation and Mr. Eric Renteria for imaging analysis.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1P41EB023833).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Kang H.W., Lee S.J., Ko I.K., Kengla C., Yoo J.J., and Atala A.. A 3D bioprinting system to produce human-scale tissue constructs with structural integrity. Nat Biotechnol 34, 312, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Malda J., Visser J., Melchels F.P., et al. 25th anniversary article: engineering hydrogels for biofabrication. Adv Mater 25, 5011, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gopinathan J., and Noh I.. Recent trends in bioinks for 3D printing. Biomater Res 22, 11, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ozbolat I.T., and Hospodiuk M.. Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting. Biomaterials 76, 321, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Panwar A., and Tan L.. Current status of bioinks for micro-extrusion-based 3D bioprinting. Molecules 21, 685, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ashammakhi N., Ahadian S., Xu C., et al. Bioinks and bioprinting technologies to make heterogeneous and biomimetic tissue constructs. Materials Today Bio 1, 10008, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murphy S.V., and Atala A.. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat Biotechnol 32, 773, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moroni L., Boland T., Burdick J.A., et al. Biofabrication: a guide to technology and terminology. Trends Biotechnol 36, 384, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moroni L., Burdick J.A., Highley C., et al. Biofabrication strategies for 3D in vitro models and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Mater 3, 21, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gillispie G., Prim P., Copus J., et al. Assessment methodologies for extrusion-based bioink printability. Biofabrication 12, 022003, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J.M., Ng W.L., and Yeong W.Y.. Resolution and shape in bioprinting: strategizing towards complex tissue and organ printing. Appl Phys Rev 6, 011307, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang H., Cong Y., Osi A.R., et al. Direct 3D printed biomimetic scaffolds based on hydrogel microparticles for cell spheroid growth. Adv Funct Mater 30, 1910573, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwab A., Helary C., Richards G., Alini M., Eglin D., and D'Este M.. Tissue mimetic hyaluronan bioink containing collagen fibers with controlled orientation modulating cell migration and alignment. Mater Today Bio 7, 100058, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diamantides N., Dugopolski C., Blahut E., Kennedy S., and Bonassar L.J.. High density cell seeding affects the rheology and printability of collagen bioinks. Biofabrication 11, 045016, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Diamantides N., Wang L., Pruiksma T., et al. Correlating rheological properties and printability of collagen bioinks: the effects of riboflavin photocrosslinking and pH. Biofabrication 9, 034102, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ouyang L., Yao R., Zhao Y., and Sun W.. Effect of bioink properties on printability and cell viability for 3D bioplotting of embryonic stem cells. Biofabrication 8, 035020, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gao T., Gillispie G.J., Copus J.S., et al. Optimization of gelatin-alginate composite bioink printability using rheological parameters: a systematic approach. Biofabrication 10, 034106, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suntornnond R., Tan E., An J., and Chua C.. A mathematical model on the resolution of extrusion bioprinting for the development of new bioinks. Materials 9, 756, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Webb B., and Doyle B.J.. Parameter optimization for 3D bioprinting of hydrogels. Bioprinting 8, 8, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Habib A., Sathish V., Mallik S., and Khoda B.. 3D printability of alginate-carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel. Materials (Basel) 11, 454, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Habib M.A., and Khoda B.. Development of clay based novel bio-ink for 3D bio-printing process. Procedia Manuf 26, 846, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahn G., Min K.H., Kim C., et al. Precise stacking of decellularized extracellular matrix based 3D cell-laden constructs by a 3D cell printing system equipped with heating modules. Sci Rep 7, 8624, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. He Y., Yang F., Zhao H., Gao Q., Xia B., and Fu J.. Research on the printability of hydrogels in 3D bioprinting. Sci Rep 6, 29977, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gohl J., Markstedt K., Mark A., Hakansson K., Gatenholm P., and Edelvik F.. Simulations of 3D bioprinting: predicting bioprintability of nanofibrillar inks. Biofabrication 10, 034105, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naghieh S., Sarker M.D., Sharma N.K., Barhoumi Z., and Chen X.. Printability of 3D printed hydrogel scaffolds: influence of hydrogel composition and printing parameters. Appl Sci 10, 292, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheng J., Lin F., Liu H., et al. Rheological properties of cell-hydrogel composites extruding through small-diameter tips. J Manuf Sci Eng 130, 021014, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maisonneuve B.G.C., Roux D.C.D., Thorn P., and Cooper-White J.J.. Effects of cell density and biomacromolecule addition on the flow behavior of concentrated mesenchymal cell suspensions. Biomacromolecules 14, 4388, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Billiet T., Gevaert E., De Schryver T., Cornelissen M., and Dubruel P.. The 3D printing of gelatin methacrylamide cell-laden tissue-engineered constructs with high cell viability. Biomaterials 35, 49, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gao G., Schilling A.F., Hubbell K., et al. Improved properties of bone and cartilage tissue from 3D inkjet-bioprinted human mesenchymal stem cells by simultaneous deposition and photocrosslinking in PEG-GelMA. Biotechnol Lett 37, 2349, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park J.H., Gillispie G.J., Copus J.S., et al. The effect of BMP-mimetic peptide tethering bioinks on the differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in 3D bioprinted dental constructs. Biofabrication 12, 035029, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bertassoni L.E., Cardoso J.C., Manoharan V., et al. Direct-write bioprinting of cell-laden methacrylated gelatin hydrogels. Biofabrication 6, 024105, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yin J., Yan M., Wang Y., Fu J., and Suo H.. 3D bioprinting of low-concentration cell-laden gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) bioinks with a two-step cross-linking strategy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10, 6849, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McBeth C., Lauer J., Ottersbach M., Campbell J., Sharon A., and Sauer-Budge A.F.. 3D bioprinting of GelMA scaffolds triggers mineral deposition by primary human osteoblasts. Biofabrication 9, 015009, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y., Xiong X., Liu X., et al. 3D Bioprinting of shear-thinning hybrid bioinks with excellent bioactivity derived from gellan/alginate and thixotropic magnesium phosphate-based gels. J Mater Chem B 8, 5500, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhuang P., Ng W.L., An J., Chua C.K., and Tan L.P.. Layer-by-layer ultraviolet assisted extrusion-based (UAE) bioprinting of hydrogel constructs with high aspect ratio for soft tissue engineering applications. PLoS One 14, e0216776, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stevens L.R., Gilmore K.J., Wallace G.G., and In Het Panhuis M.. Tissue engineering with gellan gum. Biomater Sci 4, 1276, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bacelar A.H., Silva-Correia J., Oliveira J.M., and Reis R.L.. Recent progress in gellan gum hydrogels provided by functionalization strategies. J Mater Chem B 4, 6164, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Melchels F.P.W., Dhert W.J.A., Hutmacher D.W., and Malda J.. Development and characterisation of a new bioink for additive tissue manufacturing. J Mater Chem B 2, 2282, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mouser V.H., Melchels F.P., Visser J., Dhert W.J., Gawlitta D., and Malda J.. Yield stress determines bioprintability of hydrogels based on gelatin-methacryloyl and gellan gum for cartilage bioprinting. Biofabrication 8, 035003, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li M., Tian X., Zhu N., Schreyer D.J., and Chen X.. Modeling process-induced cell damage in the biodispensing process. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16, 533, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yan K.C., Nair K., and Sun W.. Three dimensional multi-scale modelling and analysis of cell damage in cell-encapsulated alginate constructs. J Biomech 43, 1031, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aguado B.A., Mulyasasmita W., Su J., Lampe K.J., and Heilshorn S.C.. Improving viability of stem cells during syringe needle flow through the design of hydrogel cell carriers. Tissue Eng Part A 18, 806, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.