Abstract

Background

A myriad of disorders combine myoclonus and ataxia. Most causes are genetic and an increasing number of genes are being associated with myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes (MAS), due to recent advances in genetic techniques. A proper etiologic diagnosis of MAS is clinically relevant, given the consequences for genetic counseling, treatment, and prognosis.

Objectives

To review the causes of MAS and to propose a diagnostic algorithm.

Methods

A comprehensive and structured literature search following PRISMA criteria was conducted to identify those disorders that may combine myoclonus with ataxia.

Results

A total of 135 causes of combined myoclonus and ataxia were identified, of which 30 were charted as the main causes of MAS. These include four acquired entities: opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome, celiac disease, multiple system atrophy, and sporadic prion diseases. The distinction between progressive myoclonus epilepsy and progressive myoclonus ataxia poses one of the main diagnostic dilemmas.

Conclusions

Diagnostic algorithms for pediatric and adult patients, based on clinical manifestations including epilepsy, are proposed to guide the differential diagnosis and corresponding work‐up of the most important and frequent causes of MAS. A list of genes associated with MAS to guide genetic testing strategies is provided. Priority should be given to diagnose or exclude acquired or treatable disorders.

Keywords: genetics, myoclonus, ataxia, movement disorders, diagnosis

Syndromes that combine dystonia and parkinsonism, dystonia and myoclonus, and dystonia and ataxia have been extensively reviewed. 1 , 2 The association of myoclonus and ataxia has received less attention in the literature. The combination of myoclonus and ataxia can be the manifestation of a plethora of diseases. 3 , 4 In clinical practice, recognition of these entities and orchestrating the appropriate work‐up are often challenging.

Within the genetically determined myoclonus syndromes, ataxia is the most common associated movement disorder and a highly frequent accompanying clinical feature, only surpassed by epilepsy and cognitive decline. 3 Traditionally, the combination of these two movement disorders is linked to the syndrome of progressive myoclonus ataxia (PMA), previously referred to as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. The PMA share overlapping clinical features with the progressive myoclonus epilepsies (PME). 5 According to the new refined definition, 5 PMA is mainly separated from PME by the considerably lower frequency of seizures, less frequent mental deterioration, and often slower progression. PMA will often be of genetic origin, but still in many cases the etiology remains unclear despite the wide use of next generation sequencing (NGS) diagnostics.

In this systematic review, we will list the disorders that may combine myoclonus and ataxia, capture the causes of progressive myoclonus ataxia (PMA) and propose diagnostic algorithms and clinical clues for the most important and frequent causes of myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes (MAS). In addition, we will provide a list of genes associated with MAS for guidance in diagnostic NGS strategies.

Methods

A comprehensive and structured search in PubMed following PRISMA was performed by two independent reviewers (MR, SV) to identify those diseases that may combine myoclonus with ataxia. Disorders that presented with either myoclonus or myoclonic seizures were included, for it is historically unclear whether, despite a clear clinical difference, a neurobiological distinction exists between cortical myoclonus and myoclonic epilepsy with both cortically driven jerks. The following search strategy was conducted: (“myoclonus”[tiab] OR “myoclonus”[Mesh] OR myoclonic disorder*[tiab]) AND (“ataxia”[tiab] OR “ataxia”[Mesh] OR ataxic disorder*[tiab]) AND (gene*[tiab] OR acquired cause*[tiab] OR metabolic disease*[tiab] OR “inborn errors of metabolism”[tiab] OR etiolog*[tiab] OR “causality”[tiab] OR “drug‐induced”[tiab] OR “toxin”[tiab] OR autoimmune*[tiab] OR paraneoplastic*[tiab]) AND English[LA]. Publications written in English and published up to December 31, 2018 (without a start date as limitation) were reviewed. To ensure that no genetic diseases would be missed, the key words “myoclonus” and “ataxia” were also applied in OMIM and GeneReviews.

Results

A total of 30 disorders shown in Table 1 were identified as the main MAS because of the high frequency of combined myoclonus and ataxia, of which four were acquired and 26 genetic. Hundred‐and‐five other disorders were either only occasionally associated with a combined myoclonus and ataxia presentation, or had an unconfirmed genetic cause; these are listed in Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes

| Myoclonus | Epilepsy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entity or Designation | Age of Onset | Main Additional Clinical Features | Myoclonus subtype; Distribution; Activation Mode; Additional Information | Electrophysiological Characteristics of Myoclonus (Polymyography) | Seizure Types; Frequency; Therapy Response | Electrophysiological Characteristics of Epilepsy (EEG) |

| 1) Non‐genetic or acquired | ||||||

| Opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 | Infancy, childhood, adulthood | Opsoclonus, behavioral changes, insomnia, neoplasms, infections | BM a Extremities, axial muscles; Spontaneous, action | Burst duration <100 ms; No EMG–EEG correlates | Not described | Normal |

| Celiac disease 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 | Adulthood | Peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal symptoms | CM a Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive | Cortical reflex myoclonus | Seizures; Frequency unknown | Multifocal epileptiform discharges |

| Multiple system atrophy 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 | Adulthood | Parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction, orofacial dystonia, disproportionate antecollis, inspiratory sighs, severe dysphonia, dysarthria | CM Stimulus‐sensitive, action‐ or posture induced myoclonus. Small‐amplitude, distal areas Polyminimyoclonus | Positive JLBA, Giant SSEP | Not described | Not described |

| Acquired or sporadic prion diseases (iatrogenic, variant and sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease) 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 | Adulthood | Dementia, aphasia, behavioral disorders, parkinsonism, ophthalmoparesis | CM, SCM a Multifocal Both positive and negative jerks Spontaneous | Either short burst of 54.1 ± 15.8 ms or long burst of >200 ms. In most cases a positive jerk‐locked back‐averaging was present. Giant SSEP | Rarely occurring epileptic seizures (GTC) | Diffuse slow activity. Typical periodic sharp wave discharges and paroxysmal discharges |

| 2) Autosomal recessive diseases | ||||||

| Myoclonic epilepsy of Unverricht and Lundborg (MYC/ATX‐CSTB) 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 #MIM 254800 | Childhood, adolescence | CM Multifocal; Action and stimulus sensitive (stress, touch, PS) | Cortico‐muscular coherence present | GTC, C; Infrequent 1‐3/year; Responsive to therapy | Normal to slightly slow background; Brief and rare epileptiform discharges | |

| Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (MYC/ATX‐EPM2A 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 – #MIM 254780 and MYC/ATX‐NHLRC1 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 #MIM 254780) | Childhood, adolescence | Cognitive decline, hallucinations | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive (stress, sound, touch, PS) Positive and negative jerks | Brief and small bursts; Cortico‐muscular coherence present | GTC, Ab, M and V; Frequent; Intractable | Slow and poor topographic organization of background; Diffuse epileptiform discharges |

| North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 #MIM 614018 | Infancy | Scoliosis, areflexia, pes cavus, syndactyly, dysarthria, cognitive decline (rare) | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive (stress, PS) | Burst duration <100 ms; Time‐locked association between cortex and bursts; Giant SSEP | Tonic, GTC, clonic, drop attacks; Infrequent | Slow background; Generalized epileptiform discharges Photoparoxysmal responses |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 #MIM 204300 | Adolescence adulthood | Dystonia, bradykinesia, dementia, mental retardation, behavioral disorders | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive Positive and negative jerks | Time‐locked association between cortex and bursts; Giant SSEP | GTC; Rare and infrequent | Background can be preserved; Interictal epileptiform discharges; Photoparoxysmal responses |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3 or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 #MIM 611726 | Infancy | Neurologic regression following seizure onset, mental retardation, pyramidal signs, microcephaly, scoliosis | Myoclonus of unknown origin Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive (stress) Positive and negative jerks | No association with epileptic discharges on EEG and myoclonic bursts on EMG; No giant SSEP | M, GTC, Ab, A; Frequency variable Treatment responsive; Status epilepticus not uncommon | Slow background; Prominent epileptic activity; Photoparoxysmal response |

| Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to potassium channel mutation (KCNC1) 72 , 73 , 74 #MIM 616187 | Infancy, childhood, adolescence | Cognitive decline | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive (stress, sound, startle, menses) Positive and negative jerks | Cortico‐muscular coherence present. Giant SSEP Enhanced C reflexes | GTC; Infrequent; Responsive to therapy | Preservation of background; Generalized epileptiform discharges |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 with or without renal failure (MYC‐SCARB2) 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 #MIM 254900 | Adolescence, early adulthood | Tremor, renal failure, peripheral neuropathy | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action, stimulus‐induced (auditory, visual, touch, stress, fever, menses) Positive and negative jerks | Burst duration <50 ms; Positive cortical spike back‐averaging | GTC; Frequency variable | Slow background; Fast epileptiform discharges Photoparoxysmal response |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia, including variant ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 #MIM 208900 | Neonatal, infancy | Telangiectasias and other skin alterations, oculomotor apraxia, dystonia, chorea, tremor, peripheral neuropathy, distal muscular atrophy, short stature, immunodeficiency, predisposition to neoplasia | SCM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action, not stimulus‐sensitive | Burst duration 20‐385 ms; No cortical correlation No giant SSEP | Not described | Not described. |

| Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 #MIM 615768 | Variable | Nystagmus, external ophthalmoplegia, pyramidal signs, tremor, dystonia, cognitive impairment, peripheral neuropathy, hypogonadism | CM a Multifocal; Spontaneous, action | Not described | Not described | Not described |

| Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 #MIM 256550 | Variable | Cognitive decline, cherry‐red spots, dysmorphic features, hearing loss, cataracts, hepatosplenomegaly, cardiomyopathy, skeletal malformations, short stature | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action, stimulus sensitive (sound, touch, PS) Positive and negative jerks | Highly frequent and rhythmic bursts; Positive cortical spike back‐averaging; Cortico‐muscular coherence present; Giant SSEP | M, GTC; Frequent; Usually treatment‐responsive | Normal EEG in majority present; In some cases epileptiform discharges |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (MYC/ATX‐TPP1) 107 , 108 #MIM 204500 | Infancy | Developmental regression, speech and language difficulties, progressive vision loss with retinopathy, dystonia | Not described | Not described | M, GTC, Ab; Frequent; Intractable | Slow background; Focal or generalized epileptiform discharges |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders: MIRAS, SANDO, and Alpers‐Huttenlocher syndrome (POLG) 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 #MIM 607459, #MIM 203700, #MIM 613662 | Infancy, childhood, adulthood | Cognitive decline, developmental delay, peripheral neuropathy, muscle weakness and atrophy, behavioral disorders, parkinsonism, dystonia, tremor, dysarthria, nystagmus, ophthalmoparesis, cataracts, optic atrophy, hypogonadism, stroke‐like episodes, gastroparesis, cardiomyopathy, hepatic dysfunction | Myoclonus of unknown origin Multifocal; Stimulus sensitive Positive and negative jerks | Not described | M, motor, visual, G; Frequent; Refractory | Slow background; Epileptiform discharges |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 #MIM 612016 | Childhood, (early adulthood onset is rare) | Muscle weakness, exercise intolerance, episodes of vomiting, hypotonia, pes cavus, developmental delay, cognitive impairment, dystonia | SCM a Not described; Not action‐induced or stimulus sensitive | Low amplitude jerks; Burst duration 80‐135 ms; No cortical correlation | M, GTC; Infrequent | Normal background; Interictal epileptiform discharges |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) 73 , 121 , 122 #MIM 614487 | Infancy or early childhood | Spastic paraparesis, oculomotor apraxia, ptosis, dystonia, distal muscle atrophy and weakness, peripheral neuropathy | Myoclonus of unknown origin Multifocal; Spontaneous, action, stimulus sensitive; Interictal myoclonus | Not described | GTC; Infrequent | Normal or epileptiform discharges on EEG |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) 123 , 124 #MIM 603147 | Infancy or early childhood | Developmental delay, hypotonia, behavioral disorders, strabismus, retinopathy, cataracts, peripheral neuropathy, proximal muscle weakness | ‐ | Not described | M or infantile spasms; Frequent; Refractory | Slowed background; Generalized epileptiform discharges |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 7 (MFSD8) 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 #MIM 610951 | Infancy or early childhood | Developmental regression, cognitive decline, speech impairment, optic atrophy, retinopathy | ‐ | Not described | M, GTC; Frequent; Poorly responsive to therapy | Slow background; Focal or generalized epileptiform discharges |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) 35 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 #MIM 612437 | Infancy or early childhood | Developmental delay, reduced upward gaze, action tremor, pyramidal signs, peripheral neuropathy | Myoclonus of unknown origin Multifocal; Not described | Delayed cortical response during SSEP | GTC; Infrequent; Usually treatment‐responsive | Generalized epileptiform discharges |

| 3) Autosomal dominant diseases | ||||||

| Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) 33 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 MIM #125370 | Adulthood | Chorea, cognitive decline, behavioral disorders, pyramidal signs | Myoclonus of unknown origin Multifocal; Stimulus sensitive | No giant SSEP | GTC, M, A; Intractable | Diffuse epileptiform discharges; Photoparoxysmal response |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 MIM #183090 | Adulthood | Altered saccadic eye movements, ophthalmoparesis, parkinsonism, behavioral disorders, muscle atrophy, autonomic dysfunction | SCM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action, stimulus‐sensitive (touch) | High‐amplitude bursts; Burst duration 40‐60 ms | Not described | Not described |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 (ATX‐PRKCG) 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 #MIM: 605361 | Adulthood | Nystagmus, saccadic intrusions, cognitive decline, behavioral disorders, dystonia, pyramidal signs | SCM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action‐induced | Normal SEP, no cortical correlates | Not described | Not described |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 4B (MYC‐DNAJC5) 164 , 165 MIM #162350 | Adulthood | Cognitive impairment, parkinsonism, behavioral disorders, dysarthria | Myoclonus of unknown origin | Not described | M, GTC; Frequent; Intractable | Generalized epileptic discharges |

| Prion disease: Familial Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease, Gerstmann–Straussler–Scheinker disease and familial fatal insomnia (PRNP) 29 , 33 , 166 , 167 , 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 MIM #123400, MIM #137440, MIM #600072 | Adulthood | Cognitive decline, behavioral disorders, parkinsonism, pyramidal signs, ophthalmoparesis, refractory insomnia, apraxia, mutism | CM a or SCM a Multifocal; Spontaneous, action and stimulus sensitive (touch) Positive and negative jerks Polymorphic presentation of myoclonic jerks (rhythmic, dystonic and periodic) | Either burst duration of 54.1 ± 15.8 ms or > 200 ms; Positive cortical spike back‐averaging; Giant SSEP | GTC | Slow background; Epileptic discharges |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 MIM #612621 | Infancy | Developmental delay or regression, mental retardation, hypotonia, behavioral disorders, autism spectrum disorder, facial dysmorphism, orthopedic abnormalities, sleeping problems, microcephaly | ‐ | Not described | M, A, Ab, GTC, febril, reflex (eating, sound, touch); Frequent | Slow background; Focal or multifocal epileptic discharges; Photoparoxysmal response |

| SCN1A‐related disorder (SCN1A) 182 , 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 #MIM 607208 | Infancy | Psychomotor retardation, pyramidal signs | CM Multifocal; Spontaneous, action; Interictal myoclonus | EMG bursts in beta frequency during active movements, brief ranging from 24–48 ms. Giant SEPs. Presence of cortico‐muscular coherence and jerk‐locked backaveraging. | M, GTC, A, Ab; Frequent; Refractory | Interictal generalized, focal, and multifocal epileptic discharges; Photoparoxysmal response is rare |

| SLC6A1‐related disorder (SLC6A1) 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 #MIM 616421 | Infancy | Developmental delay, mental retardation, autistic features, tremor | ‐ | Not described | M, A, Ab; Treatment‐responsive | Generalized epileptic discharges; Photoparoxysmal response |

| 4) Mitochondrial diseases | ||||||

| MERRF and MELAS syndromes (mt‐MTTK) 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 MIM #590060 | Adulthood (Infancy and childhood is rare) | Cognitive impairment or mental regression, hearing loss, muscle weakness, behavioral disorders, dysarthria, dysphagia, short stature, stroke‐like episodes, cardiac abnormalities, migraine, respiratory dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms | CM a Not described; Action and stimulus sensitive | Giant SSEP | GTC | Slow background; Epileptic discharges |

Genes or conditions fulfilling criteria for progressive myoclonus ataxia (PMA) are shown in bold.

Abbreviations: CM, cortical myoclonus; SCM, subcortical myoclonus; BM, brainstem myoclonus; EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyography, M, myoclonic seizures, GTC, generalized tonic–clonic seizures; A, atonic seizures, Ab, absence seizures, V, visual seizures; ms, milliseconds, SEPs, somatosensory evoked potentials, MIRAS, Mitochondrial recessive ataxia syndrome; SANDO, sensory ataxic neuropathy, dysarthria, and ophthalmoparesis; MERRF, Myoclonic epilepsy associated with ragged‐red fibers; MELAS, Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke‐like episodes; PS, photosensitive.

Official myoclonus subtype is unknown.

An extensive review of series and cases confirmed that most MAS present as PMA or PME. 3 In general, PMA are conditions presenting first with ataxia, with the subsequent development of myoclonus, and eventually drug‐responsive epilepsy with infrequent seizures. In contrast, PME disorders were characterized by frequent and refractory epilepsy with severe cognitive decline. 5 Applying the new refined definition of PMA, 5 a total of 12 entities could be classified as such (shown in bold in Table 1), of which celiac disease, prion diseases, North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2), sialidosis type I (MYC/ATX‐NEU1), and spinocerebellar ataxias types 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) and 14 (ATX‐PRKCG) were the most relevant. One should keep in mind that these genetic disorders show variability in the clinical presentation; severe and frequent seizures can be present in some patients, in whom the clinical syndrome would be classified as PME. However, in the aforementioned 12 entities, this is true in the minority of cases. In addition, conditions like myoclonic epilepsy of Unverricht‐Lundborg (MYC/ATX‐CSTB) 199 and Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) 200 are considered as PME; however, they can sometimes present as PMA.

Some PMA disorders showed ataxia as the predominant clinical sign, as was the case of ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM), 201 the spinocerebellar ataxias type 2 (ATX‐ATXN2), 202 , 203 type 3 (ATX‐ATXN3), 203 type 14 (ATX‐PRKCG), 204 , 205 the dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) 206 or ATX‐STUB1, 207 whereas in other conditions, such as, North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2), 208 and myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to KCNC1 gene mutations, 209 myoclonus was often the main clinical feature.

In some cases, it is difficult to separate the effects of action myoclonus from ataxia on motor examination. 210 In children with PME, negative myoclonic jerks causing a loss of isotonic muscle activity and atonic seizures can interrupt smooth movement, affect balance and produce “pseudoataxia”. 211 These presumed ataxic features may improve or cease when myoclonus is controlled by appropriate treatment. 212 , 213 The use of electrophysiological techniques, especially a combined electroencephalography and polymyography, can be of additional value in identifying myoclonic jerks and determine the origin of these jerks. 214

Different types of myoclonus were described in the MAS (Table 1). In relation to the anatomical origin of myoclonus, cortical myoclonus was the most frequent type of myoclonus and presented typically as action‐induced and stimulus‐sensitive myoclonus, predominantly in distal limbs and face. 215 , 216 Cortical myoclonus was present in several conditions, such as myoclonic epilepsy of Unverricht‐Lundborg, myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora or North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2). Subcortical myoclonus was present in ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM), 201 the spinocerebellar ataxias types 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) and 14 (ATX‐PRKCG) 204 , 217 and in primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3). 218 A brainstem origin of subcortical myoclonic jerks was presumed in prion diseases (although a cortical component or origin could not be completely excluded) 219 and in opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome. 220 Of importance, the electrophysiological interpretation of jerky movements was sometimes problematic because the myoclonic discharges were superimposed in body parts also affected by dystonia, tremor or chorea. 11 , 24 , 201 , 204 , 217

Specific clinical forms of myoclonus can be present. First, polyminimyoclonus, characterized by small amplitude, jerky abnormal movements in the hands and fingers, which is suggestive of multiple system atrophy 216 or opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome. 221 Second, excessive fragmentary myoclonus, a sleep disorder characterized by subtle and fine movements at the fingertips, feet, or lips that persist throughout all stages of sleep, which can be particularly frequent in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (ATX‐ATXN3). 222

Diagnostic Approach

The large number of causes of MAS as well as the phenotypic overlap of these disorders obviously poses a challenge in clinical practice to establish a proper (genetic) diagnosis. Still, certain clinical manifestations are highly suggestive of specific diseases, such as the presence of hallucinations in myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora, opsoclonus in opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome, oculomotor apraxia or telangiectasias in ataxia‐telangiectasia, cherry‐red spots in the retina in sialidosis type 1, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in ATX‐STUB1 or hypergonadotropic hypogonadism in POLG‐ataxia and dysmorphic features in sialidosis type 2. These and other clinical clues than can help reducing the number of entities to consider when facing a patient with a MAS are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Clinical clues associated with main myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes

| Clinical Features | Disease (Gene Name) |

|---|---|

| Developmental delay or regression | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3, or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (MYC/ATX‐TPP1) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 7 (MFSD8) | |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) | |

| SCN1A‐related disorder (SCN1A) | |

| SLC6A1‐related disorder (SLC6A1) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

|

Cognitive decline or mental retardation (usually mild and/or infrequent) |

Myoclonic epilepsy of Unverricht and Lundborg (MYC/ATX‐CSTB) |

| North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) | |

| Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) | |

| Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to potassium channel mutation (KCNC1) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) | |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) | |

| Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) | |

|

Cognitive impairment or mental retardation (usually moderate or severe) |

Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (MYC/ATX‐EPM2A) |

| Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (MYC/ATX‐NHLRC1) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3, or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (MYC/ATX‐TPP1) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 7 (MFSD8) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 4B (MYC‐DNAJC5) | |

| SLC6A1‐related disorder (SLC6A1) | |

| SCN1A‐related disorder (SCN1A) | |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) | |

| Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) | |

| Prion diseases (PRNP) | |

| MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) | |

| Behavioral disorders | Opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) | |

| Prion diseases (PRNP) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 4B (MYC‐DNAJC5) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) | |

| Autistic features | SLC6A1‐related disorder (SLC6A1) |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Insomnia | Opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome |

| Prion diseases: familial fatal insomnia (PRNP) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Hallucinations | Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (MYC/ATX‐EPM2A) |

| Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (MYC/ATX‐NHLRC1) | |

| Opsoclonus | Opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome |

| Oculomotor apraxia | Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) | |

| Ophthalmoparesis | Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) |

| POLG‐related ataxias (sensory ataxic neuropathy, dysarthria, and ophthalmoparesis ‐ SANDO) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) | |

| Prion diseases (PRNP) | |

| Nystagmus | Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Retinopathy (cherry‐red spots) | Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) |

| Retinopathy | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (MYC/ATX‐TPP1) |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 7 (MFSD8) | |

| Optic atrophy | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 7 (MFSD8) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Cataracts | POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) | |

| Hearing loss | Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) |

| MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) | |

|

Peripheral neuropathy |

Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 with or without renal failure (MYC‐SCARB2) |

| North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) | |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) | |

| Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) | |

| Celiac disease | |

| Muscle atrophy and weakness | MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) | |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ic (ATX‐ALG6) | |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) | |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) | |

| Parkinsonism | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (ATX‐ATXN2) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Prion diseases (PRNP) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 4B (MYC‐DNAJC5) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) | |

| Tremor | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 with or without renal failure (MYC‐SCARB2) |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) | |

| Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) | |

| SLC6A1‐related disorder (SLC6A1) | |

| Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to potassium channel mutation (KCNC1) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Dystonia | Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 6 or Kufs disease (MYC‐CLN6) |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) | |

| Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) | |

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (MYC/ATX‐TPP1) | |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders | |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) | |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) | |

| Chorea | Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) |

| Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) | |

| Pyramidal signs | Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3, or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) | |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1B (PRICKLE1) | |

| SCN1A‐related disorder (SCN1A) | |

| Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy (ATX‐ATN1) | |

| Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia type 5 (ATX/HSP‐AFG3L2) | |

| Prion diseases (PRNP) | |

| Hypogonadism | Autosomal recessive spinocerebellar ataxia type 16 (ATX‐STUB1) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Telangiectasias | Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) |

| Pes cavus | North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) |

| Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3) | |

| Scoliosis or other skeletal deformations | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3, or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) |

| North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) | |

| Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Dysmorphic features | Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) |

| North Sea progressive myoclonus epilepsy (MYC/ATX‐GOSR2) | |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Microcephaly | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 3, or neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 14 (MYC/ATX‐KCTD7) |

| Autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 (SYNGAP1) | |

| Stroke‐like episodes | MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| Short stature | MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) |

| Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) | |

| Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) | |

| Neoplasia | Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) |

| Opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome | |

| Immunodeficiency | Ataxia‐telangiectasia (ATX‐ATM) |

| Renal failure | Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 with or without renal failure (MYC‐SCARB2) |

| Cardiac abnormalities | Neuraminidase deficiency or sialidosis type I and II (MYC/ATX‐NEU1) |

| POLG‐ataxia and allelic disorders (POLG) | |

| MERRF and MELAS syndrome (mt‐MTTK) |

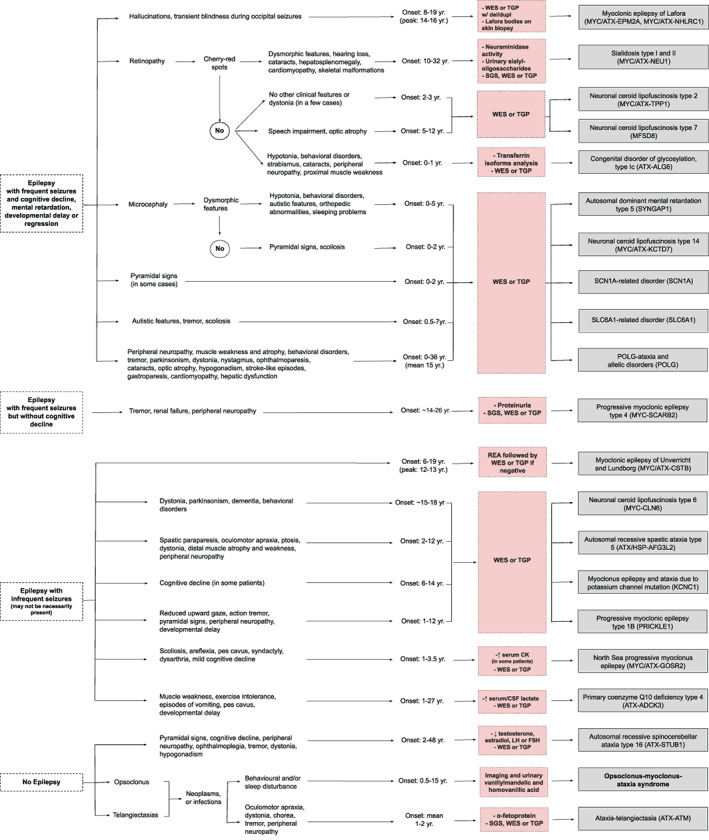

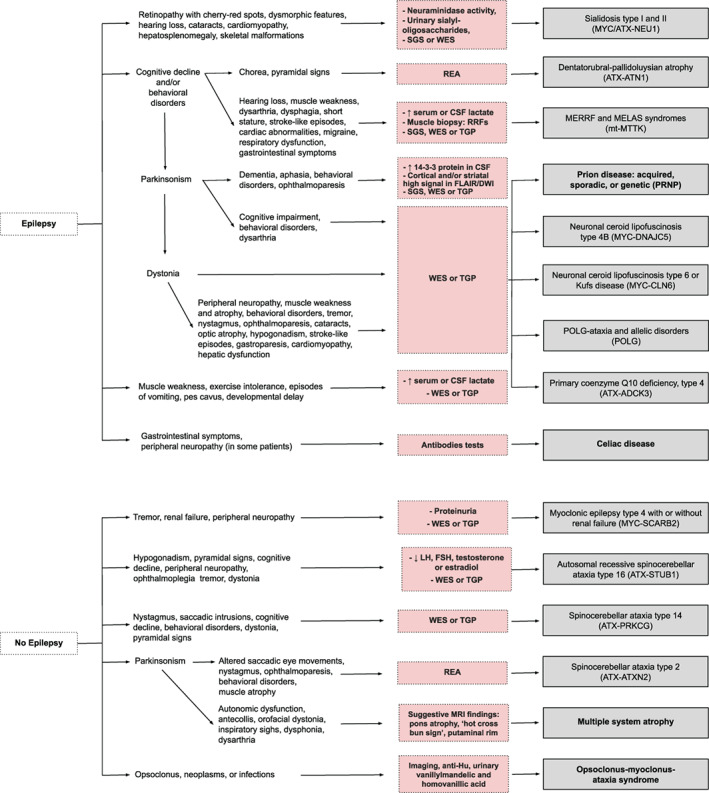

Diagnostic algorithms for childhood‐ and adult‐onset MAS are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Acquired disorders should be initially ruled out both in adults and children as these are more common than the genetically determined MAS. These include celiac disease, multiple system atrophy type C and prion diseases in adulthood (Table 1), and the clinical syndrome of opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia, often associated with a neoplasm or autoimmune disease in children, and which can also be seen in adults.

FIG 1.

Clinical diagnostic algorithm for myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes with onset in infancy or childhood. For didactic purposes, this figure includes the main myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes (entities where myoclonus and ataxia are prominent and frequent features) and which therefore should be suspected first, before considering disorders where the combination of myoclonus and ataxia is found only occasionally. In addition, next‐generation sequencing techniques can be the first step in the diagnostic process in many cases and the genetic finding can be matched or validated with the clinical features displayed in both figures. Conditions with (possible) faster disease progression are shown in bold. CMA: chromosomal microarray analysis; Del/dupl: deletions and duplications; REA: repeat expansion analysis; SGS: single gene sequencing; TGP: targeted gene panels; WES: whole exome sequencing; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicle stimulating hormone; CK: creatine kinase. Conditions with (possible) faster disease progression are shown in bold.

FIG 2.

Clinical diagnostic algorithm for myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes with onset in adulthood. For didactic purposes, this figure includes the main myoclonus‐ataxia syndromes (entities where myoclonus and ataxia are prominent and frequent features) and which therefore should be suspected first, before considering disorders where the combination of myoclonus and ataxia is found only occasionally. In addition, next‐generation sequencing techniques can be the first step in the diagnostic process in many cases and the genetic finding can be matched or validated with the clinical features displayed in both figures. Conditions with (possible) faster disease progression are shown in bold. CMA: chromosomal microarray analysis; Del/dupl: deletions and duplications; REA: repeat expansion analysis; RRFs: ragged red fibers; SGS: single gene sequencing; TGP: targeted gene panels; WES: whole exome sequencing; FLAIR: fluid attenuated inversion recovery; DWI: diffusion‐weight imaging; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicle stimulating hormone. Conditions with (possible) faster disease progression are shown in bold.

Biochemical markers could be screened before genetic testing when there is a high clinical suspicion of specific disorders, such as celiac disease antibodies, alpha‐fetoprotein for ataxia‐telangiectasia, and neuraminidase activity or urinary sialyl‐oligosaccharides for sialidosis type I. Conversely, these could be used as confirmatory markers in case genetic testing was done first.

As many of the MAS are of genetic origin, NGS techniques, i.e. targeted gene panels (TGP) or whole exome sequencing (WES), will often be needed to establish a diagnosis given the genetic heterogeneity and clinical overlap. In children with MAS, WES or TGP (preferentially including copy number variation analysis, to avoid missing some cases of myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora) could be considered first‐tier genetic tests. If negative, this could be followed by repeat expansions analysis (REA) to detect myoclonic epilepsy of Unverricht‐Lundborg (Fig. 1). In the pediatric population, the diagnostic and clinical utility of WES has been shown to be greater than CMA. 223 In adults with MAS, REA could be considered first‐tier genetic tests if a spinocerebellar ataxia, such as ATX‐ATXN2 or ATX‐ATN1 is suspected. If mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke‐like episodes (MELAS) syndrome and/or myoclonic epilepsy associated with ragged‐red fibers (MERRF) syndrome or the MERRF/MELAS overlap syndrome is suspected, TGP or WES of blood leukocyte DNA is suggested, taking into account the occurrence of heteroplasmy in mitochondrial disorders, which may require testing DNA isolated from other tissues, such as skeletal muscle, buccal mucosa, or cultured skin fibroblasts.

In Table S2, a total of 123 genes involved in disorders that combine myoclonus and ataxia are listed, which could be used for the development of specific TGP or for dedicated exome strategies that prioritize those genes that are associated with overlap phenotypes of myoclonus and ataxia.

The fact that numerous disorders present with the combination of myoclonus and ataxia, points to the possible pathophysiological link between the origin of myoclonus and cerebellar alterations, such as disruption of the cerebello‐thalamico‐cortical pathway due to loss of Purkinje cells or dentate nuclei neurons, as well as a reduction in the concentration of γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA)‐ergic synapses in the sensori‐motor cortex leading to cortical disinhibition. 224 In addition, most MAS have impaired posttranslational modification of proteins to which certain neuronal groups might be particularly vulnerable compared with others. 224

It is important to early recognize the treatable acquired or metabolic disorders, such as opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome, celiac disease, and primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency, type 4 (ATX‐ADCK3). Patients will obviously benefit from an early diagnosis and timely treatment.

Conclusions

The MAS are a clinically and etiologically heterogeneous group of disorders. We have provided diagnostic algorithms for children and adults based on clinical manifestations that will guide diagnostic procedures. However, NGS techniques can be the first diagnostic step in many cases and the genetic finding can be matched or validated with the clinical features displayed in the diagnostic algorithms. Targeted gene panels or exome filters to genetically characterize MAS could be developed based on the list of genes associated with MAS that is provided.

Author Roles

1. Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; 2. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique.

M.R.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A.

S.vd.V.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A.

M.M.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2B.

M.T.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2B.

B.vd.W.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2B.

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines. The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

This work was generated within the European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases ‐ Project ID No 739510. The authors have no conflicts to report.

Financial Disclosures for the Previous 12 months

BvdW receives research grants from Radboud university medical centre, ZonMW, Hersenstichting, uniQure, and Gossweiler Foundation.

Supporting information

Table S1. Diseases with only occasional combined myoclonus and ataxia presentation, or for which the presence of myoclonus or ataxia or the genetic finding itself are unconfirmed.

Table S2. The 123 genes involved in conditions that combine myoclonus and ataxia.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Balint B, Bhatia KP. Isolated and combined dystonia syndromes ‐ an update on new genes and their phenotypes. Eur J Neurol 2015;22:610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossi M, Balint B, Millar Vernetti P, Bhatia KP, Merello M. Genetic dystonia‐ataxia syndromes: Clinical Spectrum, diagnostic approach, and treatment options. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;5:373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van der Veen S, Zutt R, Klein C, et al. Nomenclature of genetically determined myoclonus syndromes: recommendations of the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society task force. Mov Disord 2019;34:1602–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossi M, Anheim M, Durr A, et al. The genetic nomenclature of recessive cerebellar ataxias. Mov Disord 2018;33:1056–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Veen S, Zutt R, Elting JWJ, Becker CE, de Koning TJ, Tijssen MAJ. Progressive myoclonus ataxia: Time for a new definition? Mov Disord 2018;33:1281–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hersh B, Dalmau J, Dangond F, Gultekin S, Geller E, Wen PY. Paraneoplastic opsoclonus‐myoclonus associated with anti‐Hu antibody. Neurology 1994;44:1754–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nasri A, Kacem I, Jerdak F, et al. Paraneoplastic opsoclonus‐myoclonus‐ataxia syndrome revealing dual malignancy. Neurol Sci 2016;37:1723–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oh SY, Kim JS, Dieterich M. Update on opsoclonus‐myoclonus syndrome in adults. J Neurol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pranzatelli MR, Tate ED, McGee NR. Demographic, Clinical, and Immunologic Features of 389 Children with Opsoclonus‐Myoclonus Syndrome: A Cross‐sectional Study. Front Neurol 2017;8:468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Diest D, De Raeve H, Claes J, Parizel PM, De Ridder D, Cras P. Paraneoplastic Opsoclonus‐Myoclonus‐Ataxia (OMA) syndrome in an adult patient with esthesioneuroblastoma. J Neurol 2008;255:594–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Toorn R, Rabie H, Warwick JM. Opsoclonus‐myoclonus in an HIV‐infected child on antiretroviral therapy‐‐possible immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2005;9:423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gwinn KA, Caviness JN. Electrophysiological observations in idiopathic opsoclonus‐myoclonus syndrome. Mov Disord 1997;12:438–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gordon N. Cerebellar ataxia and gluten sensitivity: a rare but possible cause of ataxia, even in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bhatia KP, Brown P, Gregory R, et al. Progressive myoclonic ataxia associated with coeliac disease. The myoclonus is of cortical origin, but the pathology is in the cerebellum. Brain 1995;118(Pt 5):1087–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fung VS, Duggins A, Morris JG, Lorentz IT. Progressive myoclonic ataxia associated with celiac disease presenting as unilateral cortical tremor and dystonia. Mov Disord 2000;15:732–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khwaja GA, Bohra V, Duggal A, Ghuge VV, Chaudhary N. Gluten Sensitivity ‐ A Potentially Reversible Cause of Progressive Cerebellar Ataxia and Myoclonus ‐ A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res 2015;9:OD07–OD08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sarrigiannis PG, Hoggard N, Aeschlimann D, et al. Myoclonus ataxia and refractory coeliac disease. Cerebellum Ataxias 2014;1:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borg M. Symptomatic myoclonus. Neurophysiol Clin 2006;36:309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu CS, Thompson PD, Quinn NP, Parkes JD, Marsden CD. Ramsay Hunt syndrome and coeliac disease: a new association? Mov Disord 1986;1:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Javed S, Safdar A, Forster A, et al. Refractory coeliac disease associated with late onset epilepsy, ataxia, tremor and progressive myoclonus with giant cortical evoked potentials‐‐a case report and review of literature. Seizure 2012;21:482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tison F, Arne P, Henry P. Myoclonus and adult coeliac disease. J Neurol 1989;236:307–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chinnery PF, Reading PJ, Milne D, Gardner‐Medwin D, Turnbull DM. CSF antigliadin antibodies and the Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Neurology 1997;49:1131–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wenning GK, Ben Shlomo Y, Magalhaes M, Daniel SE, Quinn NP. Clinical features and natural history of multiple system atrophy. An analysis of 100 cases. Brain 1994;117(Pt 4):835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tzoulis C, Engelsen BA, Telstad W, et al. The spectrum of clinical disease caused by the A467T and W748S POLG mutations: a study of 26 cases. Brain 2006;129:1685–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okuma Y, Fujishima K, Miwa H, Mori H, Mizuno Y. Myoclonic tremulous movements in multiple system atrophy are a form of cortical myoclonus. Mov Disord 2005;20:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodriguez ME, Artieda J, Zubieta JL, Obeso JA. Reflex myoclonus in olivopontocerebellar atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1994;57:316–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Batla A, De Pablo‐Fernandez E, Erro R, et al. Young‐onset multiple system atrophy: Clinical and pathological features. Mov Disord 2018;33:1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baiardi S, Magherini A, Capellari S, et al. Towards an early clinical diagnosis of sporadic CJD VV2 (ataxic type). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Binelli S, Agazzi P, Canafoglia L, et al. Myoclonus in Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: polygraphic and video‐electroencephalography assessment of 109 patients. Mov Disord 2010;25:2818–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooper SA, Murray KL, Heath CA, Will RG, Knight RS. Sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease with cerebellar ataxia at onset in the UK. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:1273–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rudge P, Jaunmuktane Z, Adlard P, et al. Iatrogenic CJD due to pituitary‐derived growth hormone with genetically determined incubation times of up to 40 years. Brain 2015;138:3386–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shi Q, Zhou W, Chen C, et al. The Features of Genetic Prion Diseases Based on Chinese Surveillance Program. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spacey SD, Pastore M, McGillivray B, Fleming J, Gambetti P, Feldman H. Fatal familial insomnia: the first account in a family of Chinese descent. Arch Neurol 2004;61:122–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andrade DM, Ackerley CA, Minett TS, et al. Skin biopsy in Lafora disease: genotype‐phenotype correlations and diagnostic pitfalls. Neurology 2003;61:1611–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Berkovic SF, Mazarib A, Walid S, et al. A new clinical and molecular form of Unverricht‐Lundborg disease localized by homozygosity mapping. Brain 2005;128:652–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Genton P. Unverricht‐Lundborg disease (EPM1). Epilepsia 2010;51(Suppl 1):37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kalviainen R, Khyuppenen J, Koskenkorva P, Eriksson K, Vanninen R, Mervaala E. Clinical picture of EPM1‐Unverricht‐Lundborg disease. Epilepsia 2008;49:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kasai K, Onuma T, Kato M, et al. Differences in evoked potential characteristics between DRPLA patients and patients with progressive myoclonic epilepsy: preliminary findings indicating usefulness for differential diagnosis. Epilepsy Res 1999;37:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lalioti MD, Scott HS, Buresi C, et al. Dodecamer repeat expansion in cystatin B gene in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nature 1997;386:847–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mazarib A, Xiong L, Neufeld MY, et al. Unverricht‐Lundborg disease in a five‐generation Arab family: instability of dodecamer repeats. Neurology 2001;57:1050–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Magaudda A, Ferlazzo E, Nguyen VH, Genton P. Unverricht‐Lundborg disease, a condition with self‐limited progression: long‐term follow‐up of 20 patients. Epilepsia 2006;47:860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Franceschetti S, Canafoglia L, Rotondi F, Visani E, Granvillano A, Panzica F. The network sustaining action myoclonus: a MEG‐EMG study in patients with EPM1. BMC Neurol 2016;16:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Avanzini G, Shibasaki H, Rubboli G, et al. Neurophysiology of myoclonus and progressive myoclonus epilepsies. Epileptic Disord 2016;18:11–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Panzica F, Canafoglia L, Franceschetti S, et al. Movement‐activated myoclonus in genetically defined progressive myoclonic epilepsies: EEG‐EMG relationship estimated using autoregressive models. Clin Neurophysiol 2003;114:1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ganesh S, Delgado‐Escueta AV, Suzuki T, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlations for EPM2A mutations in Lafora's progressive myoclonus epilepsy: exon 1 mutations associate with an early‐onset cognitive deficit subphenotype. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:1263–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harirchian MH, Shandiz EE, Turnbull J, Minassian BA, Shahsiah R. Lafora disease: a case report, pathologic and genetic study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2011;54:374–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jara‐Prado A, Ochoa A, Alonso ME, et al. Late onset Lafora disease and novel EPM2A mutations: breaking paradigms. Epilepsy Res 2014;108:1501–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schorlemmer K, Bauer S, Belke M, et al. Sustained seizure remission on perampanel in progressive myoclonic epilepsy (Lafora disease). Epilepsy Behav Case Rep 2013;1:118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Singh S, Sethi I, Francheschetti S, et al. Novel NHLRC1 mutations and genotype‐phenotype correlations in patients with Lafora's progressive myoclonic epilepsy. J Med Genet 2006;43:e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Casciato S, Gambardella S, Mascia A, et al. Severe and rapidly‐progressive Lafora disease associated with NHLRC1 mutation: a case report. Int J Neurosci 2017;127:1150–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gomez‐Abad C, Gomez‐Garre P, Gutierrez‐Delicado E, et al. Lafora disease due to EPM2B mutations: a clinical and genetic study. Neurology 2005;64:982–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Satishchandra P, Sinha S. Progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Neurol India 2010;58:514–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Striano P, Ackerley CA, Cervasio M, et al. 22‐year‐old girl with status epilepticus and progressive neurological symptoms. Brain Pathol 2009;19:727–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boisse Lomax L, Bayly MA, Hjalgrim H, et al. 'North Sea' progressive myoclonus epilepsy: phenotype of subjects with GOSR2 mutation. Brain 2013;136:1146–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Praschberger R, Balint B, Mencacci NE, et al. Expanding the Phenotype and Genetic Defects Associated with the GOSR2 Gene. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2015;2:271–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van der Veen S, Zutt R, Elting JWJ, Becker CE, de Koning TJ, Tijssen MAJ. Progressive myoclonus ataxia: Time for a new definition? Mov Disord 2018;33:1281–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Egmond ME, Verschuuren‐Bemelmans CC, Nibbeling EA, et al. Ramsay Hunt syndrome: clinical characterization of progressive myoclonus ataxia caused by GOSR2 mutation. Mov Disord 2014;29:139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Egmond ME, Weijenberg A, van Rijn ME, et al. The efficacy of the modified Atkins diet in North Sea Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy: an observational prospective open‐label study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Andrade DM, Paton T, Turnbull J, Marshall CR, Scherer SW, Minassian BA. Mutation of the CLN6 gene in teenage‐onset progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol 2012;47:205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Arsov T, Smith KR, Damiano J, et al. Kufs disease, the major adult form of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, caused by mutations in CLN6. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:566–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Berkovic SF, Oliver KL, Canafoglia L, et al. Kufs disease due to mutation of CLN6: clinical, pathological and molecular genetic features. Brain 2019;142:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bouhouche A, Regragui W, El Fahime E, et al. CLN6 p.I154del mutation causing late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in a large consanguineous Moroccan family. Indian J Pediatr 2013;80:694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Canafoglia L, Gilioli I, Invernizzi F, et al. Electroclinical spectrum of the neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses associated with CLN6 mutations. Neurology 2015;85:316–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lv Y, Zhang N, Liu C, Shi M, Sun L. Occipital epilepsy versus progressive myoclonic epilepsy in a patient with continuous occipital spikes and photosensitivity in electroencephalogram: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ozkara C, Gunduz A, Coskun T, et al. Long‐term follow‐up of two siblings with adult‐onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis, Kufs type A. Epileptic Disord 2017;19:147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sato R, Inui T, Endo W, et al. First Japanese variant of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis caused by novel CLN6 mutations. Brain Dev 2016;38:852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Blumkin L, Kivity S, Lev D, et al. A compound heterozygous missense mutation and a large deletion in the KCTD7 gene presenting as an opsoclonus‐myoclonus ataxia‐like syndrome. J Neurol 2012;259:2590–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Farhan SM, Murphy LM, Robinson JF, et al. Linkage analysis and exome sequencing identify a novel mutation in KCTD7 in patients with progressive myoclonus epilepsy with ataxia. Epilepsia 2014;55:e106–e111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kousi M, Anttila V, Schulz A, et al. Novel mutations consolidate KCTD7 as a progressive myoclonus epilepsy gene. J Med Genet 2012;49:391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moen MN, Fjaer R, Hamdani EH, et al. Pathogenic variants in KCTD7 perturb neuronal K+ fluxes and glutamine transport. Brain 2016;139:3109–3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Van Bogaert P, Azizieh R, Desir J, et al. Mutation of a potassium channel‐related gene in progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Ann Neurol 2007;61:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kim H, Lee S, Choi M, et al. Familial cases of progressive myoclonic epilepsy caused by maternal somatic mosaicism of a recurrent KCNC1 p.Arg320His mutation. Brain Dev 2018;40:429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Muona M, Berkovic SF, Dibbens LM, et al. A recurrent de novo mutation in KCNC1 causes progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat Genet 2015;47:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Oliver KL, Franceschetti S, Milligan CJ, et al. Myoclonus epilepsy and ataxia due to KCNC1 mutation: Analysis of 20 cases and K(+) channel properties. Ann Neurol 2017;81:677–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Balreira A, Gaspar P, Caiola D, et al. A nonsense mutation in the LIMP‐2 gene associated with progressive myoclonic epilepsy and nephrotic syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:2238–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dardis A, Filocamo M, Grossi S, et al. Biochemical and molecular findings in a patient with myoclonic epilepsy due to a mistarget of the beta‐glucosidase enzyme. Mol Genet Metab 2009;97:309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dibbens LM, Karakis I, Bayly MA, Costello DJ, Cole AJ, Berkovic SF. Mutation of SCARB2 in a patient with progressive myoclonus epilepsy and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Arch Neurol 2011;68:812–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dibbens LM, Michelucci R, Gambardella A, et al. SCARB2 mutations in progressive myoclonus epilepsy (PME) without renal failure. Ann Neurol 2009;66:532–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fu YJ, Aida I, Tada M, et al. Progressive myoclonus epilepsy: extraneuronal brown pigment deposition and system neurodegeneration in the brains of Japanese patients with novel SCARB2 mutations. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014;40:551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Guerrero‐Lopez R, Garcia‐Ruiz PJ, Giraldez BG, et al. A new SCARB2 mutation in a patient with progressive myoclonus ataxia without renal failure. Mov Disord 2012;27:1826–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. He J, Lin H, Li JJ, et al. Identification of a Novel Homozygous Splice‐Site Mutation in SCARB2 that Causes Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy with or without Renal Failure. Chin Med J (Engl) 2018;131:1575–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. He M, Tang BS, Li N, et al. Using a combination of whole‐exome sequencing and homozygosity mapping to identify a novel mutation of SCARB2. Clin Genet 2014;86:598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Perandones C, Pellene LA, Micheli F. A new SCARB2 mutation in a patient with progressive myoclonus ataxia without renal failure. Mov Disord 2014;29:158–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rubboli G, Franceschetti S, Berkovic SF, et al. Clinical and neurophysiologic features of progressive myoclonus epilepsy without renal failure caused by SCARB2 mutations. Epilepsia 2011;52:2356–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tian WT, Liu XL, Xu YQ, et al. Progressive myoclonus epilepsy without renal failure in a Chinese family with a novel mutation in SCARB2 gene and literature review. Seizure 2018;57:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zeigler M, Meiner V, Newman JP, et al. A novel SCARB2 mutation in progressive myoclonus epilepsy indicated by reduced beta‐glucocerebrosidase activity. J Neurol Sci 2014;339:210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cummins G, Jawad T, Taylor M, Lynch T. Myoclonic head jerks and extensor axial dystonia in the variant form of ataxia telangiectasia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:1173–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Levy A, Lang AE. Ataxia‐telangiectasia: A review of movement disorders, clinical features and genotype correlations ‐ Addendum. Mov Disord 2018;33:1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Liu XL, Wang T, Huang XJ, et al. Novel ATM mutations with ataxia‐telangiectasia. Neurosci Lett 2016;611:112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Meneret A, Ahmar‐Beaugendre Y, Rieunier G, et al. The pleiotropic movement disorders phenotype of adult ataxia‐telangiectasia. Neurology 2014;83:1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Nakayama T, Sato Y, Uematsu M, et al. Myoclonic axial jerks for diagnosing atypical evolution of ataxia telangiectasia. Brain Dev 2015;37:362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Teive HAG, Camargo CHF, Munhoz RP. More than ataxia ‐ Movement disorders in ataxia‐telangiectasia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;46:3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Termsarasab P, Yang AC, Frucht SJ. Myoclonus in ataxia‐telangiectasia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2015;5:298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. van Egmond ME, Elting JW, Kuiper A, et al. Myoclonus in childhood‐onset neurogenetic disorders: The importance of early identification and treatment. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2015;19:726–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bettencourt C, de Yebenes JG, Lopez‐Sendon JL, et al. Clinical and Neuropathological Features of Spastic Ataxia in a Spanish Family with Novel Compound Heterozygous Mutations in STUB1. Cerebellum 2015;14:378–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cordoba M, Rodriguez‐Quiroga S, Gatto EM, Alurralde A, Kauffman MA. Ataxia plus myoclonus in a 23‐year‐old patient due to STUB1 mutations. Neurology 2014;83:287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kawarai T, Miyamoto R, Shimatani Y, Orlacchio A, Kaji R. Choreoathetosis, Dystonia, and Myoclonus in 3 Siblings With Autosomal Recessive Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 16. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:888–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Synofzik M, Schule R, Schulze M, et al. Phenotype and frequency of STUB1 mutations: next‐generation screenings in Caucasian ataxia and spastic paraplegia cohorts. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ahn JH, Kim AR, Lee C, et al. Type 1 Sialidosis Patient With a Novel Deletion Mutation in the NEU1 Gene: Case Report and Literature Review. Cerebellum 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Canafoglia L, Robbiano A, Pareyson D, et al. Expanding sialidosis spectrum by genome‐wide screening: NEU1 mutations in adult‐onset myoclonus. Neurology 2014;82:2003–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gowda VK, Srinivasan VM, Benakappa N, Benakappa A. Sialidosis Type 1 with a Novel Mutation in the Neuraminidase‐1 (NEU1) Gene. Indian J Pediatr 2017;84:403–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Hu SC, Hung KL, Chen HJ, Lee WT. Seizure remission and improvement of neurological function in sialidosis with perampanel therapy. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep 2018;10:32–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Lai SC, Chen RS, Wu Chou YH, et al. A longitudinal study of Taiwanese sialidosis type 1: an insight into the concept of cherry‐red spot myoclonus syndrome. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Mohammad AN, Bruno KA, Hines S, Atwal PS. Type 1 sialidosis presenting with ataxia, seizures and myoclonus with no visual involvement. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2018;15:11–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Sekijima Y, Nakamura K, Kishida D, et al. Clinical and serial MRI findings of a sialidosis type I patient with a novel missense mutation in the NEU1 gene. Intern Med 2013;52:119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Franceschetti S, Canafoglia L. Sialidoses. Epileptic Disord 2016;18:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Chang X, Huang Y, Meng H, et al. Clinical study in Chinese patients with late‐infantile form neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Brain Dev 2012;34:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Di Giacopo R, Cianetti L, Caputo V, et al. Protracted late infantile ceroid lipofuscinosis due to TPP1 mutations: Clinical, molecular and biochemical characterization in three sibs. J Neurol Sci 2015;356:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hunter MF, Peters H, Salemi R, Thorburn D, Mackay MT. Alpers syndrome with mutations in POLG: clinical and investigative features. Pediatr Neurol 2011;45:311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Janssen W, Quaegebeur A, Van Goethem G, et al. The spectrum of epilepsy caused by POLG mutations. Acta Neurol Belg 2016;116:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Papandreou A, Rahman S, Fratter C, et al. Spectrum of movement disorders and neurotransmitter abnormalities in paediatric POLG disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 2018;41:1275–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Rajakulendran S, Pitceathly RD, Taanman JW, et al. A Clinical, Neuropathological and Genetic Study of Homozygous A467T POLG‐Related Mitochondrial Disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0145500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Spiegler J, Stefanova I, Hellenbroich Y, Sperner J. Bowel obstruction in patients with Alpers‐Huttenlocher syndrome. Neuropediatrics 2011;42:194–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Synofzik M, Srulijes K, Godau J, Berg D, Schols L. Characterizing POLG ataxia: clinics, electrophysiology and imaging. Cerebellum 2012;11:1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Aure K, Benoist JF, Ogier de Baulny H, Romero NB, Rigal O, Lombes A. Progression despite replacement of a myopathic form of coenzyme Q10 defect. Neurology 2004;63:727–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Horvath R, Czermin B, Gulati S, et al. Adult‐onset cerebellar ataxia due to mutations in CABC1/ADCK3. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Liu YT, Hersheson J, Plagnol V, et al. Autosomal‐recessive cerebellar ataxia caused by a novel ADCK3 mutation that elongates the protein: clinical, genetic and biochemical characterisation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014;85:493–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Sun M, Johnson AK, Nelakuditi V, et al. Targeted exome analysis identifies the genetic basis of disease in over 50% of patients with a wide range of ataxia‐related phenotypes. Genet Med 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Gerards M, van den Bosch B, Calis C, et al. Nonsense mutations in CABC1/ADCK3 cause progressive cerebellar ataxia and atrophy. Mitochondrion 2010;10:510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Mignot C, Apartis E, Durr A, et al. Phenotypic variability in ARCA2 and identification of a core ataxic phenotype with slow progression. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Mancini C, Orsi L, Guo Y, et al. An atypical form of AOA2 with myoclonus associated with mutations in SETX and AFG3L2. BMC Med Genet 2015;16:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Pierson TM, Adams D, Bonn F, et al. Whole‐exome sequencing identifies homozygous AFG3L2 mutations in a spastic ataxia‐neuropathy syndrome linked to mitochondrial m‐AAA proteases. PLoS Genet 2011;7:e1002325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Miller BS, Freeze HH, Hoffmann GF, Sarafoglou K. Pubertal development in ALG6 deficiency (congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ic). Mol Genet Metab 2011;103:101–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Morava E, Tiemes V, Thiel C, et al. ALG6‐CDG: a recognizable phenotype with epilepsy, proximal muscle weakness, ataxia and behavioral and limb anomalies. J Inherit Metab Dis 2016;39:713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Kousi M, Siintola E, Dvorakova L, et al. Mutations in CLN7/MFSD8 are a common cause of variant late‐infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Brain 2009;132:810–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Siintola E, Topcu M, Aula N, et al. The novel neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis gene MFSD8 encodes a putative lysosomal transporter. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Patino LC, Battu R, Ortega‐Recalde O, et al. Exome sequencing is an efficient tool for variant late‐infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis molecular diagnosis. PLoS One 2014;9:e109576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Mandel H, Cohen Katsanelson K, Khayat M, et al. Clinico‐pathological manifestations of variant late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (vLINCL) caused by a novel mutation in MFSD8 gene. Eur J Med Genet 2014;57:607–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Mastrangelo M, Tolve M, Martinelli M, Di Noia SP, Parrini E, Leuzzi V. PRICKLE1‐related early onset epileptic encephalopathy. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:2841–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Straussberg R, Basel‐Vanagaite L, Kivity S, et al. An autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia syndrome with upward gaze palsy, neuropathy, and seizures. Neurology 2005;64:142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Tao H, Manak JR, Sowers L, et al. Mutations in prickle orthologs cause seizures in flies, mice, and humans. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:138–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Algahtani H, Al‐Hakami F, Al‐Shehri M, et al. A very rare form of autosomal dominant progressive myoclonus epilepsy caused by a novel variant in the PRICKLE1 gene. Seizure 2019;69:133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Becher MW, Rubinsztein DC, Leggo J, et al. Dentatorubral and pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Clinical and neuropathological findings in genetically confirmed North American and European pedigrees. Mov Disord 1997;12:519–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Licht DJ, Lynch DR. Juvenile dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy: new clinical features. Pediatr Neurol 2002;26:51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Maruyama S, Saito Y, Nakagawa E, et al. Importance of CAG repeat length in childhood‐onset dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy. J Neurol 2012;259:2329–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Ono S, Kaneda K, Suzuki M, Tagawa A, Shimizu N. Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy with chronic renal failure in a Japanese family. Eur Neurol 2002;47:222–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Sunami Y, Koide R, Arai N, Yamada M, Mizutani T, Oyanagi K. Radiologic and neuropathologic findings in patients in a family with dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Tomiyasu H, Yoshii F, Ohnuki Y, Ikeda JE, Shinohara Y. The brainstem and thalamic lesions in dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy: an MRI study. Neurology 1998;50:1887–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Vale J, Bugalho P, Silveira I, Sequeiros J, Guimaraes J, Coutinho P. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia: frequency analysis and clinical characterization of 45 families from Portugal. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Yam WK, Wu NS, Lo IF, Ko CH, Yeung WL, Lam ST. Dentatorubral‐pallidoluysian atrophy in two Chinese families in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 2004;10:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Abdel‐Aleem A, Zaki MS. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) in an Egyptian family presenting with polyphagia and marked CAG expansion in infancy. J Neurol 2008;255:413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Armstrong J, Bonaventura I, Rojo A, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) with white matter involvement. Neurosci Lett 2005;381:247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Boesch SM, Donnemiller E, Muller J, et al. Abnormalities of dopaminergic neurotransmission in SCA2: a combined 123I‐betaCIT and 123I‐IBZM SPECT study. Mov Disord 2004;19:1320–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Crum BA, Josephs KA. Varied electrophysiologic patterns in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. De Rosa A, Striano P, Barbieri F, et al. Suppression of myoclonus in SCA2 by piracetam. Mov Disord 2006;21:116–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Durr A, Smadja D, Cancel G, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I in Martinique (French West Indies). Clinical and neuropathological analysis of 53 patients from three unrelated SCA2 families. Brain 1995;118(Pt 6):1573–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Furtado S, Payami H, Lockhart PJ, et al. Profile of families with parkinsonism‐predominant spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2). Mov Disord 2004;19:622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Kim JM, Shin S, Kim JY, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 in seven Korean families: CAG trinucleotide expansion and clinical characteristics. J Korean Med Sci 1999;14:659–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Matsuura T, Sasaki H, Yabe I, et al. Mosaicism of unstable CAG repeats in the brain of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. J Neurol 1999;246:835–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Momeni P, Lu CS, Chou YH, et al. Taiwanese cases of SCA2 are derived from a single founder. Mov Disord 2005;20:1633–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Moro A, Munhoz RP, Moscovich M, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Teive HA. Movement disorders in spinocerebellar ataxias in a cohort of Brazilian patients. Eur Neurol 2014;72:360–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Schols L, Gispert S, Vorgerd M, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. Genotype and phenotype in German kindreds. Arch Neurol 1997;54:1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Chelban V, Wiethoff S, Fabian‐Jessing BK, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlations, dystonia and disease progression in spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Mov Disord 2018;33:1119–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Foncke EM, Beukers RJ, Tijssen CC, Koelman JH, Tijssen MA. Myoclonus‐dystonia and spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 presenting with similar phenotypes: trunk tremor, myoclonus, and dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2010;16:288–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Ganos C, Zittel S, Minnerop M, et al. Clinical and neurophysiological profile of four German families with spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Cerebellum 2014;13:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Rossi M, Perez‐Lloret S, Cerquetti D, Merello M. Movement Disorders in Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxias: A Systematic Review. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2014;1:154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Stevanin G, Hahn V, Lohmann E, et al. Mutation in the catalytic domain of protein kinase C gamma and extension of the phenotype associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 14. Arch Neurol 2004;61:1242–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. van Gaalen J, Giunti P, van de Warrenburg BP. Movement disorders in spinocerebellar ataxias. Mov Disord 2011;26:792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Verbeek DS, Warrenburg BP, Hennekam FA, et al. Gly118Asp is a SCA14 founder mutation in the Dutch ataxia population. Hum Genet 2005;117:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Visser JE, Bloem BR, van de Warrenburg BP. PRKCG mutation (SCA‐14) causing a Ramsay Hunt phenotype. Mov Disord 2007;22:1024–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Vlak MH, Sinke RJ, Rabelink GM, Kremer BP, van de Warrenburg BP. Novel PRKCG/SCA14 mutation in a Dutch spinocerebellar ataxia family: expanding the phenotype. Mov Disord 2006;21:1025–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Yabe I, Sasaki H, Chen DH, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 caused by a mutation in protein kinase C gamma. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1749–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Yamashita I, Sasaki H, Yabe I, et al. A novel locus for dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA14) maps to a 10.2‐cM interval flanked by D19S206 and D19S605 on chromosome 19q13.4‐qter. Ann Neurol 2000;48:156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Cadieux‐Dion M, Andermann E, Lachance‐Touchette P, et al. Recurrent mutations in DNAJC5 cause autosomal dominant Kufs disease. Clin Genet 2013;83:571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Noskova L, Stranecky V, Hartmannova H, et al. Mutations in DNAJC5, encoding cysteine‐string protein alpha, cause autosomal‐dominant adult‐onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Am J Hum Genet 2011;89:241–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Butefisch CM, Gambetti P, Cervenakova L, Park KY, Hallett M, Goldfarb LG. Inherited prion encephalopathy associated with the novel PRNP H187R mutation: a clinical study. Neurology 2000;55:517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Kovacs GG, Ertsey C, Majtenyi C, et al. Inherited prion disease with A117V mutation of the prion protein gene: a novel Hungarian family. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;70:802–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Kovacs GG, Seguin J, Quadrio I, et al. Genetic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease associated with the E200K mutation: characterization of a complex proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2011;121:39–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Larue S, Verreault S, Gould P, Coulthart MB, Bergeron C, Dupre N. A case of familial Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease presenting with dry cough. Can J Neurol Sci 2006;33:243–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Rusina R, Fiala J, Holada K, et al. Gerstmann‐Straussler‐Scheinker syndrome with the P102L pathogenic mutation presenting as familial Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease: a case report and review of the literature. Neurocase 2013;19:41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Samman I, Schulz‐Schaeffer WJ, Wohrle JC, Sommer A, Kretzschmar HA, Hennerici M. Clinical range and MRI in Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease with heterozygosity at codon 129 and prion protein type 2. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;67:678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Sasaki K, Doh‐ura K, Wakisaka Y, Tomoda H, Iwaki T. Fatal familial insomnia with an unusual prion protein deposition pattern: an autopsy report with an experimental transmission study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2005;31:80–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Shi Q, Chen C, Wang XJ, et al. Rare V203I mutation in the PRNP gene of a Chinese patient with Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease. Prion 2013;7:259–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]