To the Editor:

Up to 70% of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors experience long-term cognitive impairment, psychological difficulties, and physical disability (1–5). Referred to as “post–intensive care syndrome” (PICS), this collection of symptoms presents challenges to survivors and caregivers that limit functional independence, employment, and quality of life (6–10). Despite their prevalence, symptoms are frequently underrecognized and undertreated (5, 11). With an estimated 5.7 million ICU admissions annually in the United States (12), expected to increase alongside the evolving coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (13), the focus on recovery after critical illness is a major public health concern that demands adaptive strategies to facilitate recovery for this vulnerable population.

In-person (14, 15) and virtual (16–21) peer support groups help overcome barriers to PICS recovery, such as limited patient education on PICS and access to post–acute care psychosocial interventions. Therapeutic support groups unite people facing similar issues, emphasize emotional support, and incorporate educational components. Virtual support systems for chronic disease management have great potential during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite a paucity of data for psychosocial interventions for ICU survivors, we must disseminate best practices to address the anticipated needs of COVID-19 survivors.

The ICU Survivor Peer Support Group at the Critical Illness, Brain Dysfunction, and Survivorship Center has met weekly for 10 years, providing structured and informal support for a growing number of ICU survivors across the United States. With new restrictions and concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic, we transitioned our hybrid (in-person and virtual) support group to an entirely virtual format (22). We aim to describe the value of our group for post-ICU recovery and discuss the feasibility and acceptability of a fully virtual support group.

Methods

After local institutional-review-board approval, we conducted an anonymous online survey of our ICU Survivor Peer Support Group participants and facilitators 6 weeks after transitioning to the virtual group. Eligible members (N = 84) were obtained from a support group listserv and were given 2 weeks for completion of the survey. Survey components were designed by study investigators. Demographic data, including sex, age range, and distance from the host institution, were obtained by voluntary response. Value, feasibility, and barriers to the support group were collected by using a Likert scale, multiple-choice questions, and free text. Data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture, which is hosted at Vanderbilt University (23).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed with Stata version 16 (StataCorp LLC) (24).

Results

The survey response rate was 31.0% (26 of 84 participants) and included responses from 22 group participants and 4 facilitator respondents. Although we sent the survey to 78 participants and 6 facilitators, the 26 respondents represented mostly regular group attendees. Demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey-respondent demographics

| Characteristic | Patients [n (%)] (N = 20) | Caregivers [n (%)] (N = 2) | Facilitators [n (%)] (N = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–29 yr | — | — | 2 (50) |

| 30–39 yr | 3 (15) | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| 50–59 yr | 6 (30) | — | — |

| 60–69 yr | 8 (40) | — | — |

| 70–79 yr | 3 (15) | 1 (50) | — |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 6 (30) | 1 (50) | 4 (100) |

| Male | 14 (70) | — | — |

| Unavailable | — | 1 (50) | — |

| Education | |||

| 12th-grade level or lower | — | — | — |

| High school diploma/GED | 1 (5) | — | — |

| Some college | 2 (10) | — | — |

| Associate’s degree | 6 (30) | — | — |

| Bachelor’s degree | 6 (30) | 2 (100) | — |

| Master’s degree | 2 (10) | — | 1 (25) |

| Doctoral degree | 3 (15) | — | 3 (100) |

| Distance from Vanderbilt | |||

| 0–20 miles | 7 (35) | 1 (50) | 4 (100) |

| 21–50 miles | 6 (30) | 1 (50) | — |

| 51–100 miles | — | — | — |

| >100 miles | 7 (35) | — | — |

| Time since most recent ICU hospitalization | — | — | |

| <6 mo | 3 (15) | ||

| 6 mo to 1 yr | 2 (10) | ||

| 1–2 yr | 7 (35) | ||

| 3–4 yr | 1 (5) | ||

| 5–10 yr | 6 (30) | ||

| >10 yr | 1 (5) | ||

| Groups attended in last year | |||

| <5 | 3 (15) | — | — |

| ≥5 | 17 (85) | 2 (100) | 4 (100) |

| Frequency of attendance | |||

| <1 time/mo | — | 1 (50) | — |

| 1–2 groups/mo | 2 (13.3) | 1 (50) | — |

| 3–4 groups/mo | 13 (86.7) | — | 4 (100) |

Definition of abbreviations: GED = general education diploma; ICU = intensive care unit.

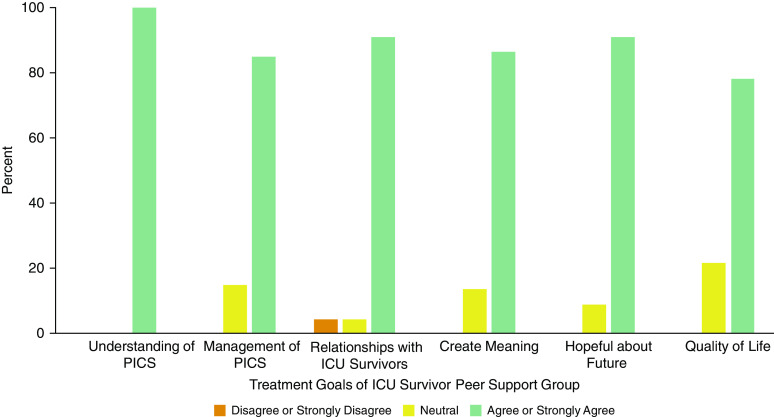

Value of the peer support group

The majority of participant respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the peer support group helped them to gain a greater understanding of PICS, better manage symptoms of PICS, and create relationships with others who had experienced ICU hospitalizations (Figure 1). Participants believed that the support group helped them to create meaning from their ICU experiences and feel more hopeful about the future and that it improved their quality of life.

Figure 1.

Participant responses (n = 22) to value-assessment statements were obtained using the Likert scale (options included “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree”). Participants include intensive care unit (ICU) survivors and their caregivers. Statements were constructed by authors to assess for the value of the ICU peer support group and included the following six statements, respectively: “The support group has helped me gain a greater understanding of PICS,” “The support group has helped me learn how to better manage my symptoms of PICS,” “The support group has helped me create relationships with others who had similar experiences during and after ICU hospitalization,” “The support group has helped me create meaning from my experiences related to ICU hospitalization,” “I feel more hopeful about my future by attending the support group,” and “My quality of life has improved as a result of the support group.” PICS = post–intensive care syndrome.

Feasibility of the virtual peer support group

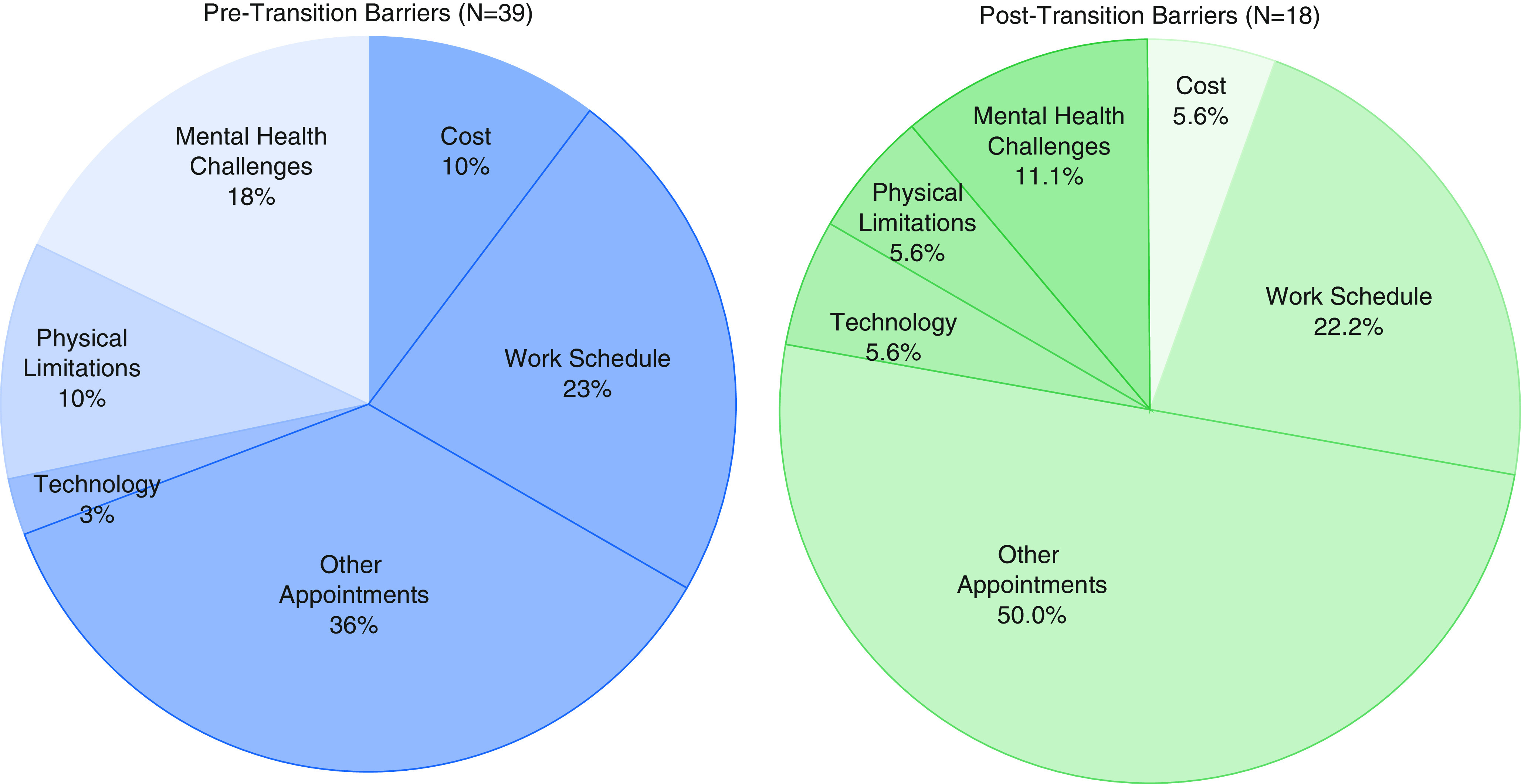

Before adopting the entirely virtual format, 69.0% (18 of 26) of respondents participated in person. To attend the virtual peer support group, participants used a mobile phone (with or without video), tablet, or computer. The majority of participants (92.0%; 24 of 26) felt comfortable or very comfortable using their device to attend the group. Participants endorsed fewer barriers to attendance after transition to the virtual group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Twenty-two (84.6%) survey respondents endorsed at least one barrier to group attendance. Participants were asked to endorse perceived barriers to attendance of at least two support group sessions before and after the transition to a full virtual support group for intensive care unit survivors. Participants endorsed a total of 34 and 18 barriers to attendance of the hybrid and virtual support groups, respectively. Categories are not mutually exclusive. Endorsement of barriers to attendance of both the hybrid group and virtual group was completed retrospectively via survey 6–8 weeks after the transition to the fully virtual group format.

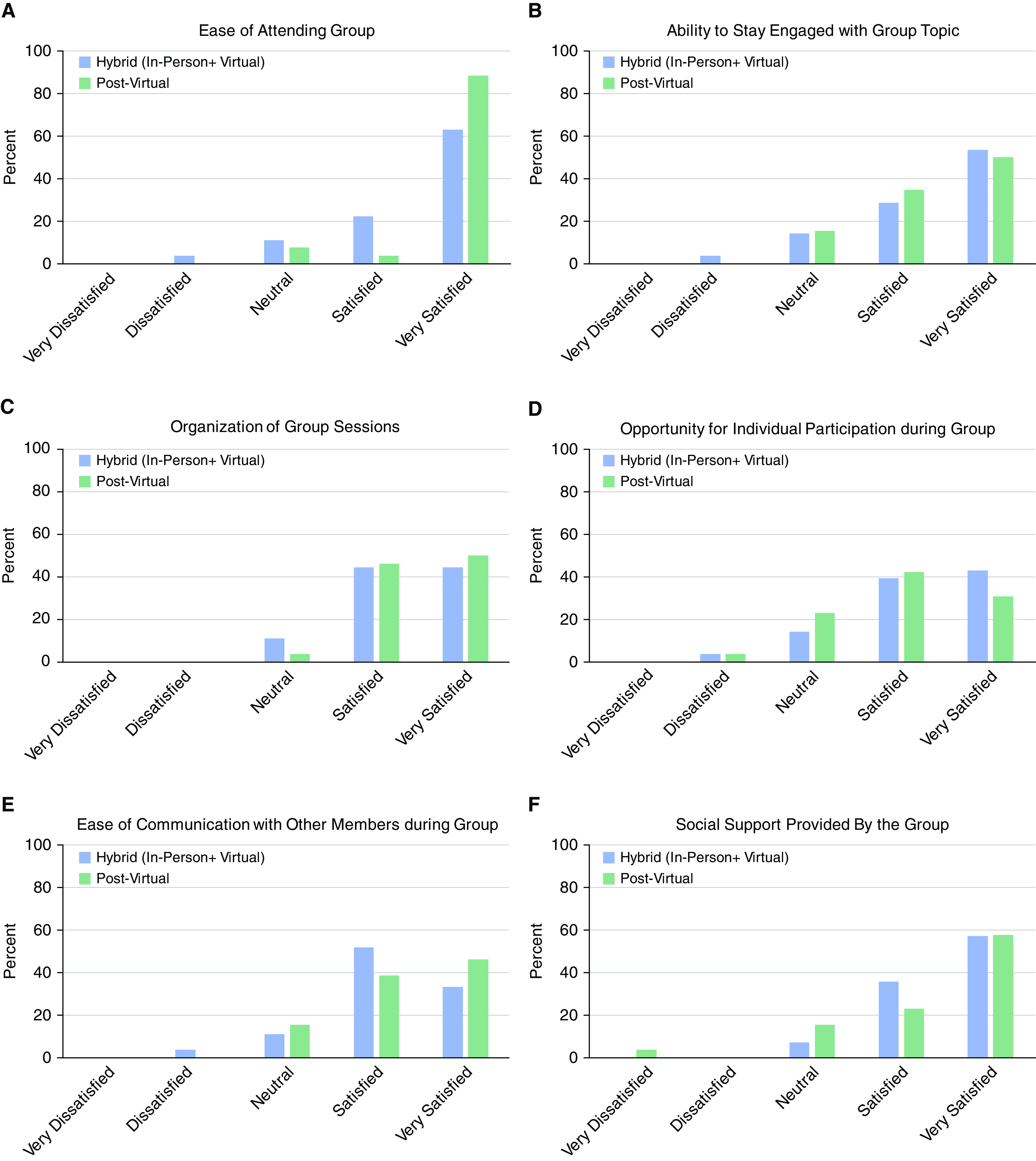

Satisfaction with virtual peer support group

Participant-satisfaction ratings for the virtual support group are shown in Figure 3. After transition to the virtual format, 90.0% (20 of 22) of participants stated they were likely or very likely to continue to attend the virtual group.

Figure 3.

Participant-satisfaction responses were obtained from participants (intensive care unit survivors and caretakers; n = 22) to determine the impact of transition from a hybrid (in-person + virtual) to a virtual peer support group format. Questions were obtained on a Likert scale (options included “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree”). Responses assessed core support group components, including (A) ease of attendance, (B) ability to stay engaged, (C) session organization, (D) opportunity for participation, (E) ease of communication, and (F) social support. Participant-satisfaction ratings of the hybrid (in-person + virtual) group are based on retrospective ratings completed 6–8 weeks after transition to the fully virtual format.

Discussion

This brief assessment of our ICU Survivors Peer Support Group suggests that virtual peer support groups for ICU survivors are valuable, feasible, and acceptable, with patient-reported benefits including social connection and support, greater understanding of physical and emotional health, increased knowledge of illness management, and improved quality of life. There were high rates of satisfaction on comfort with technology and all measures of acceptability. Participant-satisfaction ratings for the ease of attending the group improved after the transition to the virtual format. Overall, participants reported satisfaction with the virtual support group, suggesting that this format is an acceptable alternative, potentially mitigating barriers to mental health support for ICU survivors. Although our group did not include survivors of COVID-19 who were admitted to the ICU, group benefits may be critical to these patients, who face isolation, decreased social support, economic hardship, and health-related anxiety as part of this rapidly evolving global pandemic.

Improved access to psychosocial support during an era with increasing mental health risk factors will be a necessary component of post-ICU recovery. Despite concerns that virtual groups may foster feelings of disconnection (16, 25), our group participants reported a greater degree of satisfaction with the social support provided in the all-virtual group than they reported with the hybrid group.

This study has several limitations, including its small sample size, study design and response bias, and limited generalizability. Our group uniquely incorporated virtual attendees before COVID-19. Although many in-person participants established social relationships with one another before using a virtual platform, which may have facilitated the successful transition, almost one-third of respondents never participated in person but nevertheless found the group valuable. Group members may not necessarily represent the emerging population of ICU survivors whose ICU admission was related to COVID-19, who could benefit from virtual support groups because of unifying issues of survivorship across primary diagnoses (26, 27). Our experience suggests that virtual support groups are valuable and feasible for an expanding population of ICU survivors.

Future considerations for sustaining virtual peer support groups include confidentiality, optimizing virtual therapeutic relationships, pregroup screening, and significant efforts to address health inequities and disparities that would otherwise leave vulnerable populations without access to virtual mental health services.

Conclusions

We share this study with urgency to increase awareness and encourage use of virtual support groups for ICU survivors. As the COVID-19 pandemic evolves, we have the responsibility to provide safe and accessible health care for ICU survivors. Undoubtedly, social isolation presents a risk to the mental health and quality of life of survivors. Virtual platforms for peer support groups are one way we can increase access to social support, maintain human connection, and lessen the mounting psychological distress experienced by survivors of critical illness.

Footnotes

Supported by the T32 Research training grant 5T32GM108554 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (FAER), and the Society of Academic Associations of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine (SAAAPM) (C.S.B.). C.L.L.-G. receives support from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship of the National U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars program. M.N. receives support from the NIH National Institute on Aging Postdoctoral Individual National Research Service Award 1F32AG062045.

Author Contributions: C.L.L.-G. contributed to conception of the study, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafting and revision. M.N. contributed to conception of the study, data collection, analysis, and manuscript drafting and revision. A.K. contributed to conception of the study, data analysis, and manuscript revision. A.J. contributed to conception of the study, data interpretation, and manuscript revision. J.C.J. contributed to conception of the study, data interpretation, and manuscript revision. C.S.B. contributed to conception of the study, interpretation of data analysis, and manuscript drafting, revision, and submission.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, Hughes CG, et al. Bringing to Light the Risk Factors and Incidence of Neuropsychological Dysfunction in ICU Survivors (BRAIN-ICU) Study Investigators. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:369–379. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JCH, Hart RP, Gordon SM, Shintani A, Truman B, May L, et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:371–379. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatch R, Young D, Barber V, Griffiths J, Harrison DA, Watkinson P. Anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder after critical illness: a UK-wide prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22:310. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome–family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikkelsen ME, Christie JD, Lanken PN, Biester RC, Thompson BT, Bellamy SL, et al. The adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome Cognitive Outcomes Study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1307–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2025OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:90–92. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers EA, Smith DA, Allen SR, Kaplan LJ. Post-ICU syndrome: rescuing the undiagnosed. JAAPA. 2016;29:34–37. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000481401.21841.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpern NA, Pastores SM. Critical care medicine in the United States 2000-2005: an analysis of bed numbers, occupancy rates, payer mix, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:65–71. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b090d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook DJ, Marshall JC, Fowler RA. Critical illness in patients with COVID-19: mounting an effective clinical and research response. JAMA. 2020;323:1559–1560. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels LM, Johnson AB, Cornelius PJ, Bowron C, Lehnertz A, Moore M, et al. Improving quality of life in patients at risk for post-intensive care syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018;2:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlake JH, van Genderen ME, Schut A, Verkade M, Wils EJ, Gommers D, et al. Patients suffering from psychological impairments following critical illness are in need of information. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:6. doi: 10.1186/s40560-019-0422-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flickinger TE, DeBolt C, Waldman AL, Reynolds G, Cohn WF, Beach MC, et al. Social support in a virtual community: analysis of a clinic-affiliated online support group for persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:3087–3099. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1587-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong MJ, Alliance S. Virtual support groups for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia: a scoping Review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2019;33:362–369. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart MJ, Hart G, Mann K, Jackson S, Langille L, Reidy M. Telephone support group intervention for persons with hemophilia and HIV/AIDS and family caregivers. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:209–225. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale J, Caramlau IO, Lindenmeyer A, Williams SM. Peer support telephone calls for improving health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008:CD006903. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006903.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith TL, Toseland RW. The effectiveness of a telephone support program for caregivers of frail older adults. Gerontologist. 2006;46:620–629. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banbury A, Nancarrow S, Dart J, Gray L, Parkinson L. Telehealth interventions delivering home-based support group videoconferencing: systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e25. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoom Video Communications, Inc. San Jose, CA: Zoom Video Communications; 2020. Security guide. [accessed 2020 Jun 24]. Available from: https://zoom.us/docs/doc/Zoom-Security-White-Paper.pd. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozlowski KA, Holmes CM. Experiences in online process groups: a qualitative study. J Spec Group Work. 2014;39:276–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosey MM, Needham DM. Survivorship after COVID-19 ICU stay. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:60. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korupolu R, Francisco GE, Levin H, Needham DM. Rehabilitation of critically ill COVID-19 survivors. J Int Soc Phys Rehabil Med. 2020;3:45–52. [Google Scholar]