Abstract

Financial behaviors play an important role in promoting or reducing financial stability and may have an impact on health outcomes, in general. Hope theory is a framework applicable to promoting behavior change, including financial behavior change. This article describes the hope promoting components of a novel financial education and coaching program and the significant improvement in hopefulness demonstrated by women who participate in the program, as measured in the Finances First randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: financial education, hopefulness, social determinants of health, economic stability, financial stress

Health and personal finances are interconnected. In the United States, it is estimated that 47% of health outcomes are determined by socioeconomic factors.1 Economic stability is one such social determinant of health. Economic stability gives people the ability to access resources essential to a secure life: financial resources; affordable, quality housing; a job that provides a consistent, living wage; and access to healthy, affordable foods.2 Various strategies to promote health by improving economic stability have been developed, including approaches to build individual capacity such as financial education or financial coaching. A key indicator of effective financial education and coaching is facilitating changes in financial behavior. Financial behaviors can be either constructive or detrimental. Examples of constructive financial behaviors include saving money regularly, differentiating between wants and needs to prioritize spending accordingly or contributing to retirement. Detrimental financial behaviors include using payday lenders, overdrawing bank accounts, or paying bills late. Promoting positive changes in financial behavior is more complex than simply educating and providing advice. Evidence-based approaches for encouraging behavior change must be incorporated into financial education programming and coaching philosophies to effectively support individuals in achieving positive sustainable outcomes.

Hope theory is a framework applicable to promoting behavior change, including financial behavior change.3 The theory posits that hope is not just an emotion but a cognitive process and therefore hope can be generated through activities that affect patterns of thought. Hope theory suggests there are 2 ways of thinking about a goal:

Pathway thinking: Do I have the resources/direction/plan I need to achieve the goal?

Agency thinking: Am I capable and motivated to achieve this goal?

The theory hypothesizes that individuals who have a plan to reach their goal and confidence in their ability to execute their plan are more hopeful and therefore more likely to achieve their goal.

The Finances First study is a randomized controlled trial evaluating the health effects of a novel Financial Education and Coaching program: The Financial Success Program (FSP) in low-income single mother households. The study randomized participants to receive either the FSP intervention or usual care. Participant hopefulness was measured at baseline and again after twelve months using Snyder’s Adult Hope Scale (AHS).3 The scale uses 12 items (4 related to pathway thinking, 4 related to agency thinking, and 4 filler statements) with a Likert-type scale to evaluate hopefulness. Higher scores indicate a greater level of hope. A per protocol analysis in 226 English-speaking women found that participants who completed the FSP intervention experienced a significant increase in hopefulness over the 12-month study (P < .001) and the change in hopefulness was significantly greater than that experienced by women in the control group (P = .03) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trait Hope Scale Scores.

| Mean pre score | Mean post score | Mean change | P value pre vs post | Versus control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 136) | 46.8 ± 9.0 | 49.2 ± 8.5 | +2.4 ± 8.5 | .001 | |

| Intervention per protocol (n = 91) | 47.2 ± 8.6 | 52.0 ± 8.3 | +4.8 ± 7.9 | <.001 | .03 |

Although the objective of the FSP is to assist financially struggling single mothers learn how to manage their money, an increase in hopefulness is an intentional by-product of the philosophical approach of the program, the curricular activities and the experience in general.

Hope Building Components of the FSP

The FSP includes 9 weeks of group financial education classes and year-long one-on-one financial coaching with a trained facilitator.4 The financial education focuses on providing participants with new tools and skills to facilitate informed and effective financial decision making. Content and delivery are tailored specifically to meet the needs of low-income single mothers. Financial coaching connects the participants with a trained facilitator who provides guidance, support, encouragement, accountability, and tools to continue financial behavior changes and help the participant reach their financial goals.

Addressing those enrolled in the FSP as participants rather than clients immediately shifts the single mothers’ perception of themselves from passive to active. During class, women learn to create a spending plan, track expenses, and identify resources (like level payment plans for utility bills) to organize their finances. An easy to use money management system is introduced to help women address the immediate financial needs of their families. These activities support pathway thinking by teaching skills, tools, and resources to reach their goals.

Time is spent in class exploring the psychology of spending patterns and creating a vision for the future when each woman has her finances in order. Small, relatively easy action steps are assigned as homework to create a sense of momentum. By completing the homework, the women experience small successes, which subsequently builds confidence and helps them feel more in control of their finances. Building financial confidence emboldens participants to take risks and try new strategies/behaviors. As short-term financial circumstances stabilize, long-term financial goals can be pursued with a higher level of self-efficacy. This approach builds agency by increasing confidence and harnessing internal motivation.

Last, S.M.A.R.T. (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timely) financial goals are used throughout the class and coaching relationship. S.M.A.R.T. goals require participants to brainstorm the concrete actions needed to reach their goal (pathway thinking) and must be deemed achievable by the woman pursuing the goal (agency thinking). Together these activities, methods and philosophies augment hope and facilitate sustainable financial behavior change.

Implications and Future Research

Research by Snyder et al3 found that people with higher levels of hope appear to set more difficult goals, are more confident they will reach their goals and demonstrate superior performance in attaining their goals. This has important implications for the behavior change capacity of hopeful people and the potential utility of the FSP as an intervention for both economic instability and health in general. While the focus of the FSP is on personal finances and financial behavior change, economic stability also relates to healthy lifestyle behaviors. In the absence of economic stability, individuals experience increasing financial stress. Persons under financial stress are more likely to engage in smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet, and reduced exercise.5 These lifestyle behaviors further exacerbate health risk.

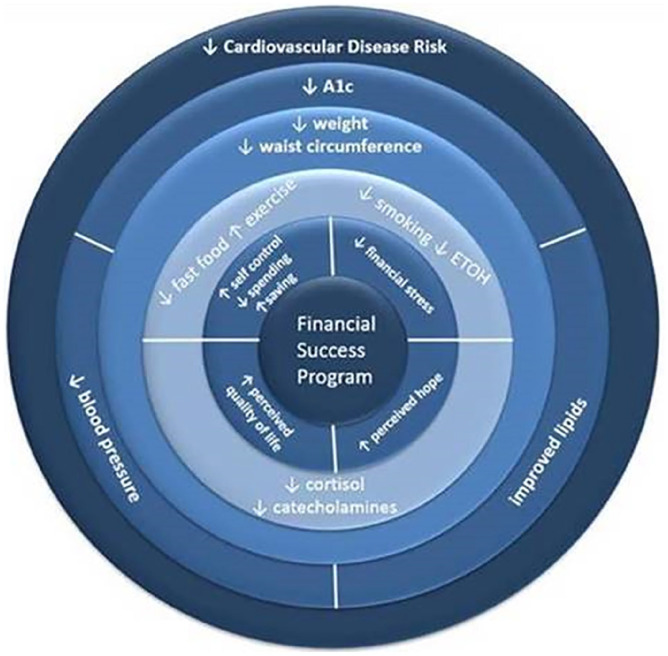

The FSP has demonstrated a reduction in participant perceived financial stress and improvements in participant hopefulness.6 Both outcomes are associated with improvements in behavior change capacity and the synergistic effects may alter health outcomes including cardiovascular disease risk (Figure 1). Nonrandomized pilot data indicates that women who participate in the FSP are successful in making positive financial and health behavior changes.7,8 While the Finances First study analysis is ongoing, both financial behaviors and healthy lifestyle behaviors are under investigation. A 20-year longitudinal study comparing the cardiovascular health outcomes of women who complete the FSP compared with matched controls is also underway.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Relationship Between the Financial Success Program and Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Finances First study is funded through a Pioneering Ideas grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and co-funded by Creighton University and Omaha area foundations.

Ethical Approval: The Finances First study received approval from the Creighton University IRB. All procedures performed in the Finances First study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: All human subjects in the Finances First study provided informed consent to participate.

Trial Registration: The Finances First study is registered on clinicaltrials.gov at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03035240.

References

- 1. Hood CM, Gennuso KP, Swain GR, Catlin BB. County Health Rankings: relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. Am J Prev Med. 2016:50:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed August 26, 2020 https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- 3. Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:570-585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. White ND, Packard K, Kalkowski J, Ryan-Haddad A, et al. A novel financial education program in single women of low-income and their children. Int Public Health J. 2015;7:49-55. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vohs KD. Psychology. The poor’s poor mental power. Science. 2013;341:969-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. White ND, Packard K, Kalkowski J. Financial education and coaching: a lifestyle medicine approach to addressing financial stress. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13:540-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Packard KA, Kalkowski J, White N, et al. Impact of a financial education program in single, low-income women and their children. Int Public Health J. 2015;7:37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 8. White ND, Packard KA, Kalkowski JC, et al. Two year durability of the effect of a financial educational program on the health of single, low-income women. J Financial Couns Plan. 2018;29:68-74. [Google Scholar]