Abstract

Objectives

As hospitals are increasingly consolidating into larger health systems, they are becoming better positioned to have far reaching and material impacts on safety and quality of care. When the Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) was formed in 2013, it sought to ensure the delivery of safe, high-quality care to every patient. In 2014, the MSHS addressed hand hygiene as the first major system-wide process improvement project focused on quality and safety. The goals of this study were to evaluate a system-wide hand hygiene program and to create a foundation for future process improvement projects.

Methods

The MSHS implemented the Joint Commission’s Targeted Solutions Tool as a way to improve hand hygiene compliance and reduce harm from hospital-acquired infections, specifically Clostridium difficile infections. A multifaceted approach was used to improve hand hygiene and promote a culture of patient safety.

Results

The MSHS improved hand hygiene compliance by approximately 20% from a baseline compliance of 63.3% to an intervention compliance of 82.8% (P < 0.001). Additional correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between increasing hand hygiene compliance and reduction in C. difficile infections.

Conclusions

Through a focus on leadership engagement, data transparency, data and observer management, and system-wide communication of best practices, the MSHS was able to improve hand hygiene compliance, reduce infection rates, and build an effective foundation for future process improvement programs.

Key Words: health system, quality improvement, hand hygiene

With dramatic changes in healthcare for the past decade, including rising costs, data transparency, and new technologies, integrating healthcare organizations has been touted as a mechanism to control costs and reduce variations in quality.1,2 Hospitals have sought to better manage patient care and confront the challenges of modern day healthcare delivery through hospital mergers that create larger health systems.3 Between 2007 and 2012, there were more than 400 announced hospital mergers and acquisitions and this number has continued to rise through 2017.2,4 As of 2013, 60% of hospitals in the United States were part of a health system.2

It was in this climate that the Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS) was created from the combination of the Mount Sinai Medical Center and Continuum Health Partners in 2013. Encompassing the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, seven hospital sites in the New York metropolitan area, and a vast array of ambulatory facilities, the MSHS serves a culturally and ethnically diverse community. The MSHS is home to more than 38,000 employees including more than 6500 physicians and has a total of 3468 beds system wide. The MSHS has a large, regional ambulatory footprint and is internationally acclaimed for its excellence in research, patient care, and education across a range of specialties. Since its inception, the MSHS has sought to set a uniformly high standard of care; capitalize on internal expertise, skills, and knowledge; align practices across varying organizational cultures; and emphasize patient safety in all aspects of hospital operations.

Previous research shows that safety can be used as a driving force behind organizational change.5 For example, the former CEO of Alcoa, Paul O’Neil, prioritized safety throughout his tenure, shifting the culture of the entire organization and, in the process, creating one of the safest manufacturing companies in America.6,7 The journey to becoming a high reliability organization has since been explored extensively within healthcare as a means for systematic change and improvement.5,8 Many health systems have leveraged their ability to provide integrated, coordinated care by focusing on structural improvements to deliver safer, higher-quality healthcare in multiple domains.3,9,10 Research on these systems suggests that creating new governance and accountability structures can improve quality and the patient experience,3,11 as can focusing on evidence-based medicine and eliminating preventable patient harm.7 Transforming an organization to truly prioritize safety takes proactive collaboration and culture change that emphasizes transparency, respect, and a willingness to learn and improve.12,13 Thus, by leveraging principles of high reliability organizations, the MSHS sought to improve patient experience and outcomes.

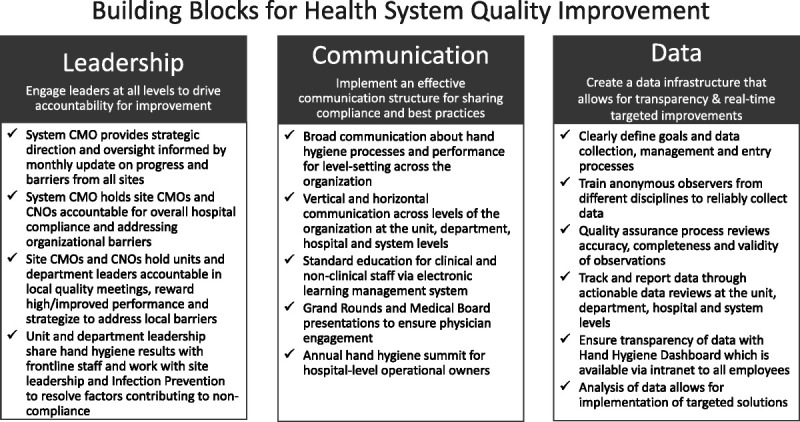

In 2014, the MSHS addressed hand hygiene as the first major system-wide process improvement project. Hand hygiene is beneficial for staff and patient safety and has proven important in reducing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs).14–17 However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that healthcare providers comply with hand hygiene standards less than 50% of the time.18 Furthermore, common compliance measurement tools, such as self-reporting and overt hand hygiene observers, result in dramatically inaccurate measurements, decreasing the likelihood of implementing effective methods to improve hand hygiene practices.19,20 Although direct observation of hand hygiene is considered the best way to both attain compliance measurements and record barriers to compliance, the Hawthorne effect may considerably limit the accuracy of this method. One study found that compliance recorded using covert observations were more than 40% lower than those using overt observations, suggesting that covert observation of hand hygiene may result in more useful and accurate compliance data.20 To combat low compliance rates, multifaceted approaches that emphasize reducing barriers to hand washing should be used to improve hand hygiene and promote a culture of patient safety in hospitals.21,22 Findings from Shabot et al23 describe how implementing such initiatives in a health system may be particularly useful. In addition, improving hand hygiene system-wide requires involvement and engagement from a large and diverse workforce. The MSHS initiative worked to align patient safety goals across a broad, interdisciplinary cross section of clinical and nonclinical employees and establish a foundation for process and quality improvement. The MSHS implemented an existing hand hygiene program that was evidence-based and also allowed for customization to leverage the health system’s strengths and resources. The implementation of this program helped create a foundation for the key skills and competencies that are essential for effective problem-solving. Strong leadership commitment to implementing an efficient and sustainable process; organized, consistent, and multidisciplinary communication within and across the health system; and data driven solutions served as the backbone for this program, as well as imbued the essentiality of safety system wide (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Quality improvement framework.

METHODS

Background on the Joint Commission’s Targeted Solutions Tool for Hand Hygiene

The MSHS elected to implement the Joint Commission Targeted Solutions Tool (JCTST) for hand hygiene to improve hand hygiene behavior in inpatient units across the Health System. The JCTST is a web-based application designed to apply Robust Process Improvement techniques to improving hand hygiene compliance.24 The JCTST approach is composed of three phases of implementation, including a baseline data collection phase, an intervention phase, and a sustainability phase. Additional specifics on the use of the JCTST framework have been previously published.21,23,25

Adoption of the JCTST at MSHS

The MSHS began implementing the JCTST in August 2014, with a total of six hospitals participating in the program. The MSHS received mentorship from the Memorial Hermann Health System who had successfully implemented the JCTST and significantly improved hand hygiene compliance.7 This mentorship allowed MSHS to use validated best practices throughout implementation, enhancing the success of the program. The JCTST was rolled out in unit cohorts, depending on the size and structure of the hospital and its units. As of October 2017, the smallest hospital in the health system had implemented the JCTST in five units and the largest hospital in the system had implemented the JCTST in 37 units. Because of the variability in hospital size and culture, a key aspect of implementation was ensuring that each hospital in the system maintained a cohesive goal and structure, while also allowing a level of customization that would ensure sustained improvements at each of these unique sites.

The success of the program was fostered by the involvement of the MSHS Chief Medical Officer (CMO), who championed the initiative, provided strategic direction for implementation, and held hospital leadership accountable. The CMO also assigned a dedicated MSHS hand hygiene team to provide strong centralized project management oversight. Responsibilities of this team included working with hospital and frontline leadership to role out the initiative across the system, providing training and analytical support, creating sustainability plans with the sites, and serving as liaisons between hospitals to share best practices. The MSHS HAI Council, an established council of health system and hospital executive leadership, served as an additional means to discuss program management, compliance, and other issues pertinent to program implementation. In addition, each individual hospital had an interdisciplinary hand hygiene oversight committee led by senior leadership. This structure ensured that hand hygiene was an institutional priority with broad engagement from across hospital departments. In addition, proactive communication with the labor unions regarding the anonymous observation component helped address any participation concerns from frontline staff, most of whom are union members.

Observer Training and Data Management

A key component of the JCTST is the use of anonymous observers to track hand hygiene compliance on each unit. The MSHS aimed to involve a broad base of staff in the hand hygiene observer training as a means of reinforcing interdisciplinary engagement across the system and the message that hand hygiene is everyone’s responsibility.7,26–29 Individual hospitals trained not just nurses, but also physicians, dietary and environmental services staff, and a variety of other staff members. This strategy reinforced accountability among different types of staff for appropriate hand hygiene and allowed for unit, hospital, and system-level discussions on hand hygiene and patient safety behaviors. Overall, more than 1000 hospital staff served as anonymous observers after being trained through in-person trainings or via an online education portal. A posttraining quiz and auditing of observations helped ensure consistency of data collection. This quality assurance process, managed by the hand hygiene team, addressed the completeness, accuracy, and validity of observations.

The MSHS hand hygiene team worked with each hospital to define data collection and management processes. Engaging hospital and unit leaders in structured data management allowed for timely data entry, as well as the preservation of the anonymity of observers. Through this process, unit leadership and the hand hygiene team were also able to determine whether observers were no longer anonymous and train new observers when necessary. Furthermore, transparency of performance was particularly salient to the program and would likewise serve as an example of excellence for future process improvement projects. To create transparency and drive performance accountability, the system hand hygiene team provided assistance to each hospital in analyzing and reviewing data and developed a widely available online dashboard via the health system intranet to support weekly tracking of hand hygiene data for every unit. This tool provided additional reporting functionality, which is not available in the JCTST including compliance trends over time, by role, and across units and departments. The data collected via the anonymous observers was used to design targeted interventions specific to each unit to improve compliance.

Hospital-Acquired Infections

As part of its commitment to improving patient safety and reducing patient harm, the MSHS championed improved hand hygiene as a way to address HAIs. A specific focus was on the reduction of the incidence of Clostridium difficile infections system-wide. Clostridium difficile was selected as an outcome of interest because hand hygiene is a necessary and critical component in mitigating the spread of this infection.14,30–32

Data Analysis

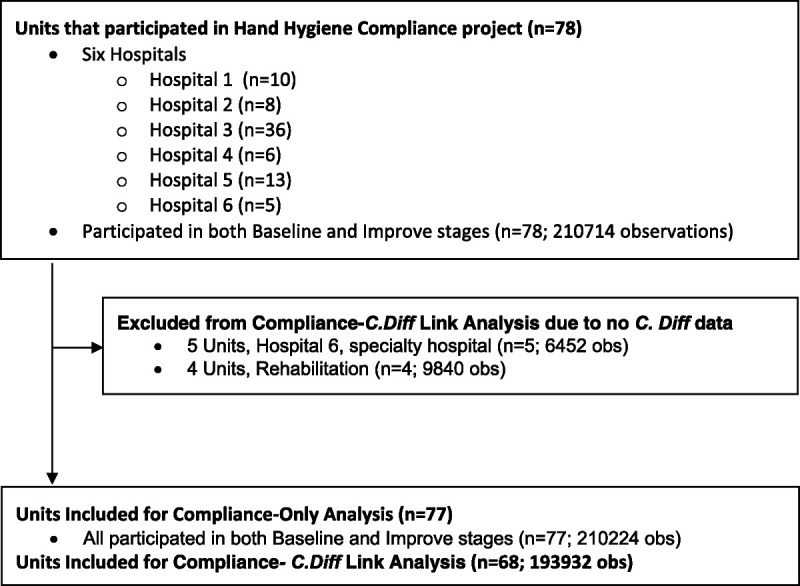

Compliance was compared between the baseline and intervention stages. Compliance was also compared by hospital, time of day (day vs night), and hospital role using the χ2 test with α set to 0.05 in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). One unit was excluded from the compliance-only analysis because of insufficient compliance data for the 3-year period of observations. To compare the rate of C. difficile and compliance, join point regression analysis was conducted in Joinpoint Regression Program 4.5.0.1 (Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute) to uncover underlying trends in compliance and to test for natural turning points in these trend lines. Only units that collected C. difficile data were included in the C. difficile analysis. Thus, hospital 6, a specialty hospital, was completely excluded from this part of the analysis, as were all MSHS rehabilitation units (Fig. 2). Two MSHS surge units were included in the C. difficile data but not the compliance data, because they were only in use a small percentage of the time.

FIGURE 2.

Consort diagram for compliance-C. difficile link analysis.

RESULTS

Between August 2014 and October 2017, a total of 210,224 hand hygiene observations were collected by anonymous observers at six system hospitals. Individuals were marked as compliant if they washed their hands with soap and water or an alcohol-based solution upon entry or exit of the patient care area. The proportion of compliant observations (%) was compared by hospital, time of day, and role within the hospitals (Table 1). In total, 77 units across the health system recorded 53,728 hand hygiene observations during the baseline stage and 156,496 hand hygiene observations during the intervention stage. The number of observations collected varied by hospital because of significant differences in size and number of units participating at each hospital. Most observations were collected on clinical staff (77.1%), which included nurses, physicians, and nursing assistants. In addition, approximately 77% of observations were collected during day shift hours (7:00 a.m.–6:59 p.m.) and 23% of observations were collected during night shift hours (7:00 p.m.–6:59 a.m.).

TABLE 1.

Summary of Hand Hygiene Compliance Results

| Baseline | Intervention | χ2P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Hand Hygiene Observations | No. Compliant (%) | No. Hand Hygiene Observations | No. Compliant (%) | ||

| Hospital | |||||

| Hospital 1 | 9331 | 6394 (68.5) | 24,246 | 19,735 (81.4) | <0.001 |

| Hospital 2 | 2235 | 954 (42.7) | 23,246 | 18,802 (80.9) | <0.001 |

| Hospital 3 | 31,858 | 19,580 (61.5) | 50,120 | 41,236 (82.3) | <0.001 |

| Hospital 4 | 3285 | 1713 (52.1) | 33,563 | 27,940 (83.2) | <0.001 |

| Hospital 5 | 5890 | 4524 (76.8) | 19,998 | 17,236 (86.2) | <0.001 |

| Hospital 6 | 1129 | 869 (77.0) | 5323 | 4609 (86.6) | <0.001 |

| Time of day | |||||

| Day (7:00 a.m.–6:59 p.m.) | 41,108 | 26,524 (64.5) | 121,103 | 99,661 (82.3) | <0.001 |

| Night (7:00 p.m.–6:59 a.m.) | 12,620 | 7510 (59.5) | 35,393 | 29,897 (84.5) | <0.001 |

| Hospital role | |||||

| Case manager/social worker | 668 | 433 (64.8) | 2562 | 2150 (83.9) | <0.001 |

| Dietary services | 2073 | 944 (45.5) | 5786 | 4290 (74.1) | <0.001 |

| Housekeeping | 2135 | 953 (44.6) | 6847 | 4949 (72.3) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | 356 | 178 (50.0) | 2761 | 2376 (86.1) | <0.001 |

| Physician | 10,759 | 6574 (61.1) | 29,052 | 22,803 (78.5) | <0.001 |

| Nursing assistant | 9773 | 5977 (61.2) | 31,425 | 26,361 (83.9) | <0.001 |

| Other | 2980 | 1562 (52.4) | 6954 | 5048 (72.6) | <0.001 |

| Physical/respiratory therapy | 2987 | 2017 (67.5) | 10,388 | 8921 (85.9) | <0.001 |

| Radiology | 474 | 236 (49.8) | 1272 | 911 (71.6) | <0.001 |

| Nurse | 21,523 | 15,160 (70.4) | 59,449 | 51,749 (87.0) | <0.001 |

| Overall | 53,728 | 34,034 (63.3) | 156,496 | 129,558 (82.8) | <0.001 |

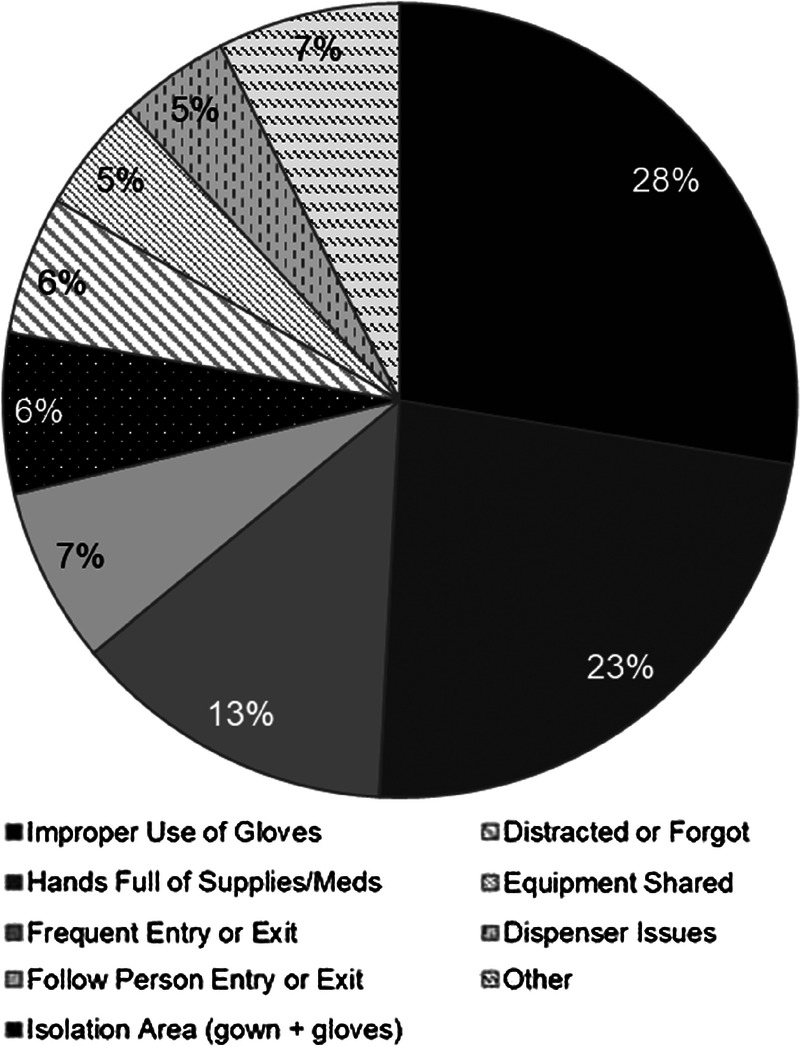

All hospitals improved significantly from the baseline stage to the intervention stage (Table 1). Individual hospital compliance ranged from 42.7% to 77.0% in the baseline stage. In the intervention stage, compliance increased at all hospitals and variability was reduced system-wide, with intervention compliance ranging from 80.9% to 86.6%. All hospital roles also improved significantly from baseline to intervention. Notably, dietary and housekeeping staff improved compliance by nearly 30%. Overall system compliance improved by approximately 20% from 63.3% to 82.8% (P < 0.001). Barriers to compliance were also assessed for individual hospital roles at each site (Fig. 3). Barriers were found to be similar at all sites, with the major barriers system-wide including improper use of gloves, frequent entry and exit of a patient room, and hands full of supplies or medications.

FIGURE 3.

Hand hygiene barriers, MSHS.

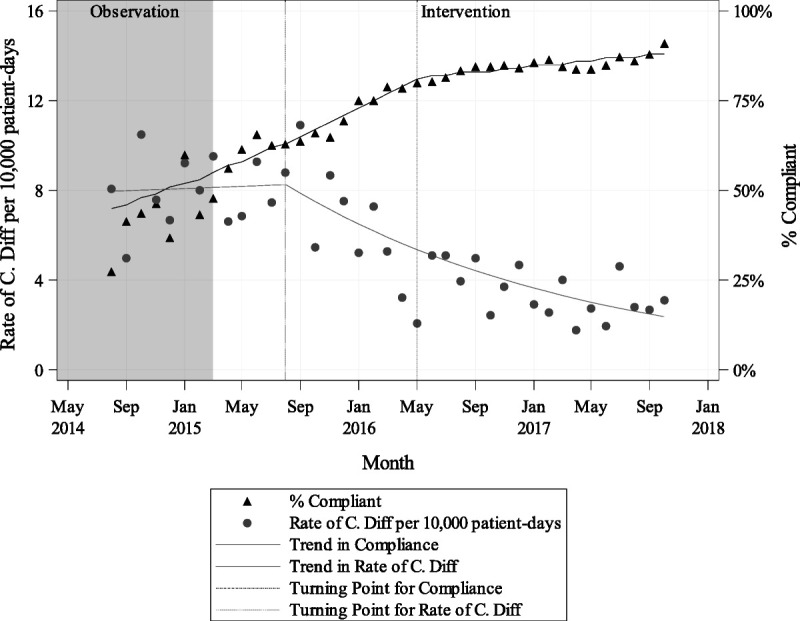

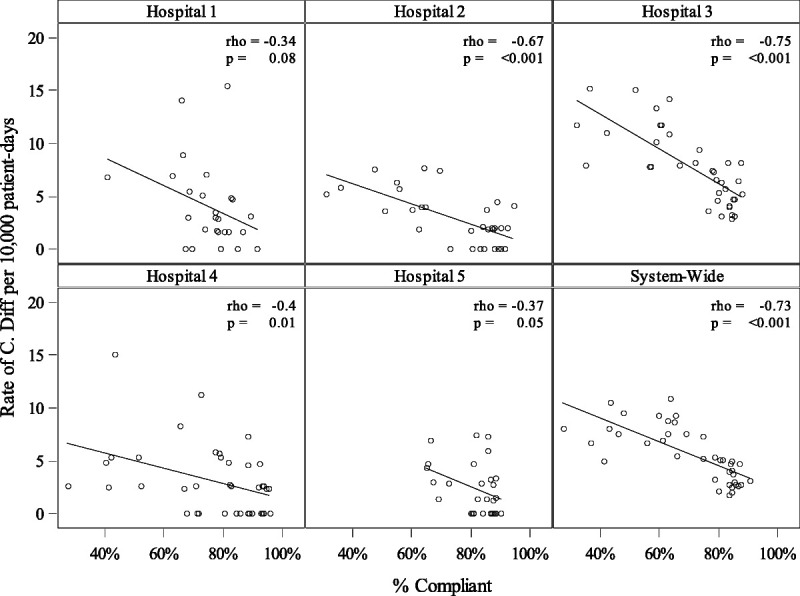

Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess for underlying trends in hand hygiene compliance and in C. difficile infection rates and to test for natural turning points in these trend lines (Fig. 4; turning points indicated with dotted lines). The analysis revealed a significant decrease in C. difficile for MSHS overall from August 2015 to October 2017 (annual percent change, −4.67% [95% confidence interval {CI} = −6.1 to −3.2]). There were also two significant periods of increases in compliance from February 2015 to May 2016 (annual percent change, 2.84% [95% CI = 2.3 to 3.4]) and from May 2016 to October 2017 (annual percent change, 0.48% [95% CI = 0.3 to 0.7]). It is notable that there are significant declines in the rate of C. difficile in most of the MSHS hospitals and that they occur alongside significant increases in hand hygiene compliance (Fig. 5). The correlation analysis indicated that there is a significant negative correlation between compliance and rate of C. difficile per 10,000 patient-days at MSHS overall and all hospitals, excluding hospital 1 and 5 (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4.

Trends in compliance and rate of C. difficile per 10,000 patient-days system-wide by month.

FIGURE 5.

Compliance versus rate of C. difficile per 10,000 patient-days by hospital.

DISCUSSION

Despite the plethora of research on improving hand hygiene in hospitals, few studies have explored hand hygiene programs or other best practices in quality improvement among newly formed health systems. The growth of health systems in the past decade indicates a significant need for additional insight on effectively implementing a process improvement infrastructure in such systems. The MSHS sought to implement an evidence-based hand hygiene program across six system hospitals to improve quality and safety. These findings highlight the benefits of using a hand hygiene improvement program to create a foundation for patient safety and process improvement, rooted in leadership engagement, data transparency, and interdisciplinary communication.

Baseline compliance recorded by each unit and hospital was consistently low, averaging only 63% across the MSHS. The MSHS was able to significantly improve hand hygiene compliance across all staff types, hospitals, and day and night shifts. Leveraging data from the JCTST allowed for the development of specific interventions tailored to the barriers of compliance at the unit and department level.21 For example, improper glove use was a common barrier to compliance but had different root causes across the system. To effectively target improper glove use, different solutions were implemented including addressing workflows and enhancing the physical space to support appropriate glove use. The data demonstrate a strong and significant correlation between hand hygiene improvement and a reduction in C. difficile system-wide. This adds to the body of literature that suggests that improving hand hygiene can have a significant impact on HAI rates in hospitals.14,23,33

The success of the program was predicated on deliberate and consistent action by leadership. This was essential for engaging employees and creating an organizational culture in which all levels and types of staff feel the same responsibility for and commitment to quality and safety. The health system CMO along with site CMOs and Chief Nursing Officers offered strong and vocal support for the hand hygiene program by holding all levels of leadership accountable, including unit nurse managers and physicians. In addition to involving nurses and physicians, the system hand hygiene team regularly reached out to housekeeping and dietary services leadership to address any challenges related to workflow or provide additional resources to the teams. Focusing on staff types that are infrequently involved in hand hygiene work or other quality initiatives proved essential for increasing hand hygiene compliance. It also created a motivated group of staff that remain driven to improve patient care, establishing a foundation of long-term local ownership.

The program likewise depended on complete transparency with consistent and widespread review of hand hygiene compliance and barriers to compliance data. Reviewing and sharing compliance data regularly enabled the implementation of unit and department-specific interventions and empowered both clinicians and nonclinicians to have an important role in patient safety. To this end, the MSHS continues to collect approximately 7000 observations a month, fortify processes related to hand hygiene data collection, and improve and sustain compliance. Hand hygiene compliance will continuously be monitored and the JCTST will support ongoing implementation of targeted solutions.

Broad communication about hand hygiene allowed for it to be a cornerstone of the organization’s culture because it relates to patient safety. Ultimately, the message at the MSHS was and continues to be that hand hygiene is everyone’s responsibility. The ongoing communication about compliance, improvement, and best practices is critical to maintaining hand hygiene as a top priority for the health system.

Addressing hand hygiene as a system-wide improvement initiative while allowing each individual hospital to adapt local practices allowed us to leverage internal expertise and spread best practices as part of our journey to high reliability. Individual sites were able to share creative ideas including ways to reward and recognize improvements with monthly compliance trophies, initiatives for engaging staff, and solutions to workflow related challenges that were often similar across sites. In addition, because all six system hospitals are unique, individual hospitals and units were able to develop customizations that allowed the program to function optimally based on the hospital’s patient population and staff structure. Such customization has previously been shown to improve hand hygiene compliance and, at the MSHS, led to a level of sustainability that likely would not have been possible if all hospitals and units were forced to actualize this program in the same way.21

Limitations

In any hospital setting, determining causation can be prohibitive. It is not possible to prove that the health system’s C. difficile rates went down exclusively because of improved hand washing. Additional factors, such as environmental efforts to reduce infections, antibiotic stewardship, and testing stewardship, may have also played a role in system C. difficile rates. Despite this, this work lends additional support to the notion that hand washing may be valuable to reducing C. difficile infections. Additional limitations of the JCTST are discussed in previous literature and are likewise applicable to our findings.21,23

Future Research

These findings highlight the benefits of working within a health system to build a successful hand hygiene initiative and process improvement foundation. Health systems should publish additional work on standardizing processes to improve the body of literature around best practices in health system quality and safety. Future research should also continue to explore the impact of hand washing on HAIs. Likewise, the JCTST was implemented at the MSHS as intended, as an inpatient hand hygiene program; however, valuable lessons can be learned from exploring the use of the JCTST or other hand hygiene initiatives in additional hospital areas, such as operating rooms, emergency departments, and outpatient areas.

CONCLUSIONS

Hand hygiene compliance can be improved and sustained within a health system by building a foundation that includes leadership engagement, data transparency, and system-wide communication of best practices. Focusing on these components while also allowing for modifications based on the varying cultures, structures, and patient populations of each system hospital allowed for the successful roll-out of a large scale health system quality improvement program. In addition, hand hygiene compliance was found to be significantly and negatively correlated with C. difficile infection rates. Other health systems can create a similar infrastructure to address hand hygiene compliance and C. difficile rates that can lay the foundation for additional initiatives to improve upon other quality metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Jeremy Boal for his support of the Hand Hygiene Program and review of the article.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Alexandra Rosenberg, Email: alexandra.rosenberg@mountsinai.org.

Swati Garg, Email: swati.garg@mountsinai.org.

Jennifer Nahass, Email: jennifer.nahass@mountsinai.org.

Andrew Nenos, Email: andrew.nenos@mountsinai.org.

Natalia Egorova, Email: natalia.egorova@mountsinai.org.

John Rowland, Email: john.rowland@mountsinai.org.

Joseph Mari, Email: joseph.mari@mountsinai.org.

Vicki LoPachin, Email: vicki.lopachin@mountsinai.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chukmaitov A Harless DW Bazzoli GJ, et al. . Delivery system characteristics and their association with quality and costs of care: implications for accountable care organizations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2015;40:92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutler DM, Scott Morton F. Hospitals, market share, and consolidation. JAMA. 2013;310:1964–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pronovost PJ Armstrong CM Demski R, et al. . Creating a high-reliability health care system: improving performance on core processes of care at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90:165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin Associates Products. In: The 2017 Health Care Services Acquisition Report. 23rd ed Available at: https://products.levinassociates.com/downloads/har-2017/. Accessed August 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chassin MR, Loeb JM. High-reliability health care: getting there from here. Milbank Q. 2013;91:459–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Neill P, Pillow M. An interview with Paul O’Neill. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40:428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shabot MM Monroe D Inurria J, et al. . Memorial Hermann: high reliability from board to bedside. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pronovost P Needham D Berenholtz S, et al. . An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1064–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pronovost PJ Demski R Callender T, et al. . Demonstrating high reliability on accountability measures at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39:531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leape L Berwick D Clancy C, et al. . Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. BMJ Qual Saf. 2009;18:424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent C, Benn J, Hanna GB. High reliability in health care. BMJ. 2010;340:c84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittet D Hugonnet S Harbarth S, et al. . Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection Control Programme. Lancet. 2000;356:1307–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schweon SJ Edmonds SL Kirk J, et al. . Effectiveness of a comprehensive hand hygiene program for reduction of infection rates in a long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sroka S, Gastmeier P, Meyer E. Impact of alcohol hand-rub use on meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an analysis of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2010;74:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings: Show Me the Science. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/science/index.html. Published April 28, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2018.

- 19.Haas JP, Larson EL. Measurement of compliance with hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66:6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Saed A Noushad S Tannous E, et al. . Quantifying the Hawthorne effect using overt and covert observation of hand hygiene at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:930–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chassin MR, Mayer C, Nether K. Improving hand hygiene at eight hospitals in the United States by targeting specific causes of noncompliance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015;41:4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel B Engelbrecht H McDonald H, et al. . A multifaceted hospital-wide intervention increases hand hygiene compliance. S Afr Med J. 2016;106:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shabot MM Chassin MR France AC, et al. . Using the targeted solutions tool® to improve hand hygiene compliance is associated with decreased health care-associated infections. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42:6–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Targeted Solutions Tool for Hand Hygiene | The Center for Transforming Healthcare [Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare web site]. 2018. Available at: https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/tst_hhy.aspx. Accessed December 17, 2018.

- 25.Chassin MR Nether K Mayer C, et al. . Beyond the collaborative: spreading effective improvement in hand hygiene compliance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2015;41:13–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams CL Scruth EA Andrade C, et al. . Implementing clinical practice guidelines for screening and detection of delirium in a 21-hospital system in northern California: real challenges in performance improvement. Clin Nurse Spec. 2015;29:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell M Carrico C Moore CK, et al. . Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 1: Assessment). In: Henriksen K Battles JB Keyes MA, et al., eds. Christiana Care Health System: Safety Mentor Program. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Advances in Patient Safety; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Compton J Copeland K Flanders S, et al. . Implementing SBAR across a large multihospital health system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukas CV Holmes SK Cohen AB, et al. . Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32:309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyce JM, Pittet D. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(S12):S3–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerding DN, Muto CA, Owens RC., Jr Measures to control and prevent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Supplement_1):S43–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gould D. Prevention and control of Clostridium difficile infection. Nurs Older People (through 2013); London. 2010;22:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luangasanatip N Hongsuwan M Limmathurotsakul D, et al. . Comparative efficacy of interventions to promote hand hygiene in hospital: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]