Abstract

Background

Recent data suggest that complications and death from coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) may be related to high viral loads.

Methods

In this ongoing, double-blind, phase 1–3 trial involving nonhospitalized patients with Covid-19, we investigated two fully human, neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein, used in a combined cocktail (REGN-COV2) to reduce the risk of the emergence of treatment-resistant mutant virus. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive placebo, 2.4 g of REGN-COV2, or 8.0 g of REGN-COV2 and were prospectively characterized at baseline for endogenous immune response against SARS-CoV-2 (serum antibody–positive or serum antibody–negative). Key end points included the time-weighted average change in viral load from baseline (day 1) through day 7 and the percentage of patients with at least one Covid-19–related medically attended visit through day 29. Safety was assessed in all patients.

Results

Data from 275 patients are reported. The least-squares mean difference (combined REGN-COV2 dose groups vs. placebo group) in the time-weighted average change in viral load from day 1 through day 7 was −0.56 log10 copies per milliliter (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.02 to −0.11) among patients who were serum antibody–negative at baseline and −0.41 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −0.71 to −0.10) in the overall trial population. In the overall trial population, 6% of the patients in the placebo group and 3% of the patients in the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups reported at least one medically attended visit; among patients who were serum antibody–negative at baseline, the corresponding percentages were 15% and 6% (difference, −9 percentage points; 95% CI, −29 to 11). The percentages of patients with hypersensitivity reactions, infusion-related reactions, and other adverse events were similar in the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups and the placebo group.

Conclusions

In this interim analysis, the REGN-COV2 antibody cocktail reduced viral load, with a greater effect in patients whose immune response had not yet been initiated or who had a high viral load at baseline. Safety outcomes were similar in the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups and the placebo group. (Funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and the Biomedical and Advanced Research and Development Authority of the Department of Health and Human Services; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04425629.)

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel coronavirus first identified in December 2019,1 is the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). After becoming infected, most persons have few or no symptoms despite having high viral loads,2-5 and their condition can be managed on an outpatient basis. In a smaller number of persons, hypoxemia develops, leading to hospitalization and receipt of supplemental oxygen.6-8 An early hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of Covid-19 hypoxemia pointed to an immune system hyperresponse to viral infection9; this led to studies of various immunomodulating agents, with mixed results.10-13 More recent data have shown high viral titers in hospitalized patients,14 suggesting that the virus is in part responsible for ongoing hypoxemia.

In an ongoing trial, we are investigating REGN-COV2, an antibody cocktail containing two SARS-CoV-2–neutralizing antibodies, in nonhospitalized patients with Covid-19. Our central hypothesis is that complications and death from Covid-19 emanate from the SARS-CoV-2 viral burden and that reducing this burden should lead to clinical benefit. REGN-COV2 is a cocktail made up of two noncompeting, neutralizing human IgG1 antibodies that target the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, thereby preventing viral entry into human cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.15,16 We prospectively pursued a “cocktail” approach because of previous experience with the emergence of treatment-resistant mutant virus when a single antibody, suptavumab, was used to target respiratory syncytial virus.17 Preclinical studies confirmed that the REGN-COV2 cocktail protects against the rapid emergence of such mutants seen with either single antibody.15 In vivo studies in nonhuman primates have shown profound antiviral activity of REGN-COV2 in reducing viral load when given in a prophylactic context and in improving viral clearance when given in a therapeutic context.18

We further hypothesized that in an outpatient context, patients would present at various stages of development of their own native humoral immune response and that exogenously provided antibodies would have the most benefit in patients whose immune response had not yet been initiated. Consequently, all patients were screened for the presence of preexisting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and were classified as either serum antibody–positive or serum antibody–negative at trial entry.

Here, we describe results of an initial analysis involving 275 symptomatic patients from our ongoing phase 1–3 trial involving outpatients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

Trial Design

We are conducting an ongoing operationally seamless (continual enrollment), multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1–3 clinical trial involving symptomatic, nonhospitalized patients with Covid-19. The interim analysis we describe here involved the first 275 patients enrolled during the phase 1–2 portion of the trial and was conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of REGN-COV2, to gain an understanding of the natural history of Covid-19 in outpatients, and to refine the end points for subsequent analyses. The trial continues to recruit beyond the first 275 patients for whom data are described in this report; the results for the key primary and secondary prespecified end points are planned to be reported at trial completion. The data cutoff for this interim analysis was September 4, 2020.

In the phase 1–2 portion of the trial reported here, all patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive placebo, REGN-COV2 at a dose of 2.4 g (low dose), or REGN-COV2 at a dose of 8.0 g (high dose) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org). Each of the two antibodies that make up REGN-COV2 — casirivimab (REGN10933) and imdevimab (REGN10987) — is given in equal doses in the cocktail.

Details of the randomization stratification are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. The phase 1 portion of the trial included additional pharmacokinetic analyses but was otherwise identical to the phase 2 portion. The population of patients in the current analysis was pooled from both phases.

Patients

To be eligible for participation, patients had to be 18 years of age or older and nonhospitalized. All patients had to have a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a SARS-CoV-2–positive test result received no more than 72 hours before randomization and symptom onset no more than 7 days before randomization. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. The protocol is available at NEJM.org.

An assay for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was performed in all patients. Because these results were not available at randomization, patients underwent randomization regardless of their baseline serologic status, and the analyses were prespecified to first evaluate efficacy in the subgroup of patients who were serum antibody–negative — that is, those patients who tested negative for all three of the following antibodies: IgA anti-S1 domain of spike protein, IgG anti-S1 domain of spike protein, and IgG anti-nucleocapsid protein. Patients who were positive for any one of these antibodies were designated as serum antibody–positive. A small number of patients could not be evaluated or had borderline results (unknown serum antibody status); analyses involving these patients were conducted but are not reported here.

Intervention and Assessments

At baseline (day 1), REGN-COV2 (at the high dose or low dose) or saline placebo was administered intravenously in a 250-ml normal saline solution over a period of 1 hour. The schedule of assessments is described in the protocol, along with a summary of protocol amendments. Quantitative virologic analysis, SARS-CoV-2 serum antibody testing, and measurement of the two components of REGN-COV2 in serum are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

End Points

Multiple prespecified end points were designated for the phase 1–2 portion of the trial (see the Supplementary Appendix and the statistical analysis plan, which is available with the protocol). However, because of the lack of a priori information that would allow us to correctly select end points, and because certain employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (who had no role in the conduct of the trial) had access to unblinded early data from the trial as described in the protocol, no formal hypothesis testing was performed.

The prespecified key virologic end point in the statistical analysis plan was defined as the time-weighted average change in the viral load (in log10 copies per milliliter) from baseline (day 1) through day 7, as measured by quantitative reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) testing of nasopharyngeal swab samples obtained from serum antibody–negative patients. The change in viral load from baseline to various days during the trial was an additional prespecified virologic end point, and the change in absolute viral load (measured in copies per milliliter) was a post hoc virologic end point.

The prespecified key clinical end point was the percentage of patients with at least one Covid-19–related medically attended visit through day 29 in both the serum antibody–negative subgroup and the overall trial population. Medically attended visits could include telemedicine visits, in-person physician visits, urgent care or emergency department visits, and hospitalization.

For assessments of safety, we collected data on adverse events that occurred or worsened during the observation period (grade 3 and 4; phase 1 only), serious adverse events that occurred or worsened during the observation period (phases 1 and 2), and the following adverse events of special interest (phases 1 and 2): grade 2 or higher hypersensitivity or infusion-related reactions. Pharmacokinetic variables included the concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum over time.

Trial Oversight

Regeneron designed the trial; gathered the data, together with the trial investigators; and analyzed the data. Regeneron and the authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data, and Regeneron vouches for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. The authors provided critical feedback and final approval of the manuscript for submission. No one who is not an author contributed to writing the manuscript. All the investigators had confidentiality agreements with Regeneron.

The investigators, site personnel, and Regeneron employees who were involved in collecting and analyzing data were unaware of the treatment-group assignments. An independent data and safety monitoring committee periodically monitored unblinded data to make recommendations about trial modification and termination. The independent committee and, separately, Regeneron physicians who were aware of the treatment-group assignments and were not involved in the conduct of the trial performed interim data reviews for adapting the trial design.

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The local institutional review board or ethics committee at each study center oversaw trial conduct and documentation. One center was found to have violations of Good Clinical Practice guidelines (not related to the collection of data on efficacy or safety end points) and was withdrawn from the trial after analyses had been completed. All the patients provided written informed consent before participating in the trial.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis plan for the presented analysis was finalized before database lock and unblinding. The full analysis set included the first 275 patients with Covid-19 symptoms who underwent randomization in the combined phase 1–2 portions of the trial. A sample of 275 patients (72 in phase 1 and 203 in phase 2) was considered sufficient for the assessment of virologic efficacy, clinical trends, and safety for the purpose of informing subsequent analyses. Because patients could enroll if they had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 no more than 72 hours before randomization, patients who tested negative by qualitative RT-PCR at baseline (lower limit of detection, 714 copies per milliliter [2.85 log10 copies per milliliter]) were excluded from analyses of virologic end points in a modified full analysis set. Because of the a priori hypothesis that patients whose immune system was already clearing the virus were unlikely to benefit from additional antibody therapy, analyses were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan to focus on the serum antibody–negative subgroup. All patients who received REGN-COV2 or placebo were included in the safety population.

The time-weighted average change from baseline (day 1) through day 7 was calculated for each patient as the area under the concentration–time curve, with the use of the linear trapezoidal rule for change from baseline divided by the time interval of the observation period. This end point was analyzed with an analysis-of-covariance model with treatment group, risk factor, and baseline serum antibody status as fixed effects and baseline viral load and treatment group–by–baseline viral load as covariates. Confidence intervals in this report were not adjusted for multiplicity. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 or higher (SAS Institute). Additional statistical and pharmacokinetic analysis methods are described in the Supplementary Appendix.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

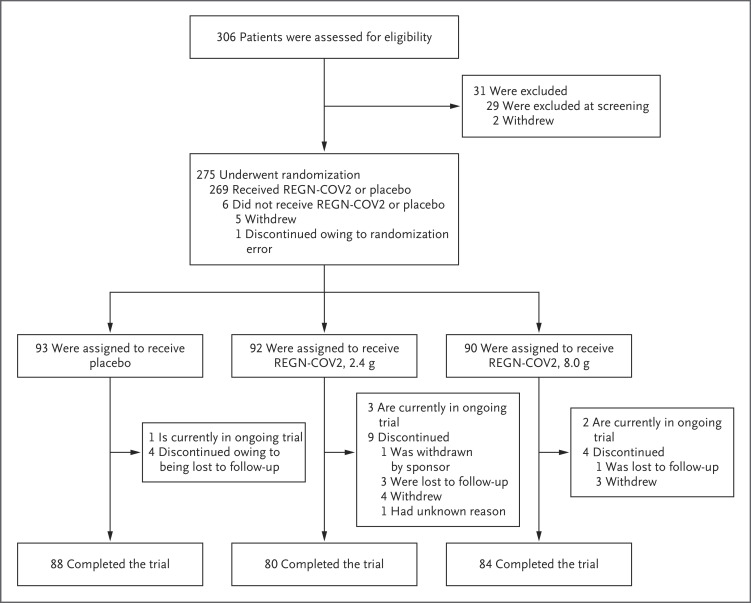

Of the 275 patients who underwent randomization between June 16, 2020, and August 13, 2020, a total of 269 received REGN-COV2 or placebo. Among the 275 patients, 90 were assigned to receive high-dose REGN-COV2, 92 to receive low-dose REGN-COV2, and 93 to receive placebo (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Treatment.

One patient underwent randomization in error, and Regeneron requested that the patient withdraw from the trial. Four patients in the low-dose REGN-COV2 group withdrew consent: one patient could not participate in the follow-up period, one patient could not have blood drawn and an intravenous line placed, and two patients withdrew consent with no additional information available. Three patients in the high-dose REGN-COV2 group withdrew consent: one patient could not participate in the follow-up period, one patient could not have blood drawn and an intravenous line placed, and one withdrew consent with no additional information available.

The median age of the patients in the trial was 44.0 years, 49% were male, 13% identified as Black or African American, and 56% identified as Hispanic or Latino (Table 1). The median number of days of reported Covid-19–related symptoms before randomization was 3.0.

Table 1. Demographic and Baseline Medical Characteristics.*.

| Characteristic | REGN-COV2 | Placebo (N=93) |

Total (N=275) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 g (N=92) |

8.0 g (N=90) |

Combined (N=182) |

|||

| Median age (IQR) — yr† | 43.0 (33.5–51.0) | 44.0 (36.0–53.0) | 43.0 (35.0–52.0) | 45.0 (34.0–54.0) | 44.0 (35.0–52.0) |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 46 (50) | 38 (42) | 84 (46) | 50 (54) | 134 (49) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnic group — no. (%)‡ | 52 (57) | 55 (61) | 107 (59) | 46 (49) | 153 (56) |

| Race — no. (%)‡ | |||||

| White | 74 (80) | 78 (87) | 152 (84) | 72 (77) | 224 (81) |

| Black or African American | 15 (16) | 6 (7) | 21 (12) | 14 (15) | 35 (13) |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Not reported | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Median weight (IQR) — kg† | 85.65 (72.20–97.10) | 86.25 (72.60–98.30) | 86.10 (72.60–97.30) | 83.90 (72.90–97.70) | 86.00 (72.60–97.50) |

| Body-mass index§ | 30.39±6.578 | 30.63±7.216 | 30.51±6.874 | 29.73±7.149 | 30.25±6.961 |

| Obesity — no. (%)¶ | 39 (42) | 42 (47) | 81 (45) | 34 (37) | 115 (42) |

| Baseline viral load in nasopharyngeal swab | |||||

| Raw values | |||||

| No. of patients | 84 | 83 | 167 | 91 | 258 |

| Mean viral load — copies/ml | 16,080,000±27,810,000 | 19,170,000±29,120,000 | 17,620,000±28,420,000 | 12,950,000±25,620,000 | 15,970,000±27,510,000 |

| Median viral load (range) — copies/ml | 260,000 (1–71,000,000) | 195,000 (1–71,000,000) | 200,000 (1–71,000,000) | 50,500 (1–71,000,000) | 156,000 (1–71,000,000) |

| Log10 scale | |||||

| No. of patients | 84 | 83 | 167 | 91 | 258 |

| Mean viral load — log10 copies/ml | 5.04±2.495 | 5.00±2.527 | 5.02±2.503 | 4.67±2.366 | 4.90±2.457 |

| Median viral load (range) — log10 copies/ml | 5.41 (0.0–7.9) | 5.29 (0.0–7.9) | 5.30 (0.0–7.9) | 4.70 (0.0–7.9) | 5.19 (0.0–7.9) |

| Positive baseline qualitative RT-PCR — no. (%)‖ | 73 (79) | 74 (82) | 147 (81) | 81 (87) | 228 (83) |

| Baseline serum C-reactive protein level | |||||

| No. of patients | 87 | 86 | 173 | 92 | 265 |

| Mean level — mg/liter | 11.1±28.1 | 12.2±20.0 | 11.7±24.4 | 21.5±43.5 | 15.1±32.6 |

| Median level (range) — mg/liter | 3.0 (0.2–239.7) | 4.8 (0.1–138.7) | 3.7 (0.1–239.7) | 4.8 (0.1–232.0) | 4.1 (0.1–239.7) |

| Baseline serum antibody status — no. (%) | |||||

| Negative | 41 (45) | 39 (43) | 80 (44) | 33 (35) | 113 (41) |

| Positive | 37 (40) | 39 (43) | 76 (42) | 47 (51) | 123 (45) |

| Unknown** | 14 (15) | 12 (13) | 26 (14) | 13 (14) | 39 (14) |

| Median time from symptom onset to randomization (range) — days | 3.5 (0–7) | 3.0 (0–8) | 3.0 (0–8) | 3.0 (0–8) | 3.0 (0–8) |

| At least one risk factor for hospitalization — no. (%)†† | 57 (62) | 61 (68) | 118 (65) | 58 (62) | 176 (64) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. RT-PCR denotes reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

The interquartile range (IQR) is defined as quartile 1 to quartile 3.

Race and ethnic group were reported by the patients.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Obesity is defined as a body-mass index of greater than 30.

A positive result was defined as a viral load greater than or equal to the lower limit of detection (714 copies per milliliter [2.85 log10 copies per milliliter]).

An unknown serum antibody status indicates that the status could not be evaluated or that the results were borderline.

Risk factors for hospitalization include an age of more than 50 years, obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease (including receipt of dialysis), chronic liver disease, and immunocompromise (immunosuppression or receipt of immunosuppressants).

At randomization, 30 of 275 patients (11%) tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 by qualitative RT-PCR and 17 of 275 (6%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 but did not have baseline viral load data; therefore, 228 of the 275 patients (83%) who underwent randomization made up the modified full analysis set (i.e., those patients who were confirmed SARS-CoV-2–positive by RT-PCR at baseline). At baseline, 123 patients (45%) were serum antibody–positive, 113 (41%) were serum antibody–negative, and 39 (14%) had unknown antibody status. Baseline characteristics according to serum antibody status are shown in Table S1.

Natural History

Any treatment effect of REGN-COV2 can be properly interpreted only in the context of an understanding of the endogenous immune response and its effect on viral load and disease course. Therefore, in addition to the prespecified trial end points, a major focus of the trial is to examine the natural history of Covid-19.

The median and mean baseline viral loads were 7.18 log10 copies per milliliter and 6.60 log10 copies per milliliter, respectively, among serum antibody–negative patients and were 3.49 log10 copies per milliliter and 3.30 log10 copies per milliliter, respectively, among serum antibody–positive patients (Fig. S2). The raw median baseline viral load among serum antibody–negative patients was also higher than that among serum antibody–positive patients (1.5×107 copies per milliliter vs. 3.1×103 copies per milliliter). In a retrospective analysis, the presence and titer of neutralizing antibodies were also associated with viral load: serum antibody–positive patients who lacked neutralizing activity had a viral load range similar to that among serum antibody–negative patients (see the Supplementary Study Results section in the Supplementary Appendix). Of the 6 patients in the placebo group who had a medically attended visit for worsening Covid-19 symptoms, only 1 was from the serum antibody–positive subgroup (1 of 47 [2%]), as compared with 5 from the serum antibody–negative subgroup (5 of 33 [15%]) (Table 2). By these measures, patients in the serum antibody–positive subgroup had substantially lower viral loads and a lower likelihood of having a medically attended visit than patients in the serum antibody–negative subgroup.

Table 2. Key Virologic and Clinical End Points.*.

| End Point | REGN-COV2 | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 g | 8.0 g | Combined | ||

| Time-weighted average change in viral load from day 1 through day 7 † | ||||

| Modified full analysis set‡ | ||||

| No. of patients | 70 | 73 | 143 | 78 |

| Least-squares mean change — log10 copies/ml | −1.60±0.14 | −1.90 ±0.14 | −1.74±0.11 | −1.34±0.13 |

| 95% CI | −1.87 to −1.32 | −2.18 to −1.62 | −1.95 to −1.53 | −1.60 to −1.08 |

| Difference vs. placebo at day 7 — log10 copies/ml | ||||

| Least-squares mean | −0.25±0.18 | −0.56±0.18 | −0.41±0.15 | |

| 95% CI | −0.60 to 0.10 | −0.91 to −0.21 | −0.71 to −0.10 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: negative | ||||

| No. of patients | 34 | 35 | 69 | 28 |

| Least-squares mean change — log10 copies/ml | −1.89±0.18 | −1.96±0.18 | −1.94±0.13 | −1.37±0.20 |

| 95% CI | −2.24 to −1.53 | −2.33 to −1.60 | −2.20 to −1.67 | −1.76 to −0.98 |

| Difference vs. placebo at day 7 — log10 copies/ml | ||||

| Least-squares mean | −0.52±0.26 | −0.60±0.26 | −0.56±0.23 | |

| 95% CI | −1.04 to 0.00 | −1.12 to −0.08 | −1.02 to −0.11 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: positive | ||||

| No. of patients | 27 | 29 | 56 | 37 |

| Least-squares mean change — log10 copies/ml | −1.24±0.19 | −1.63±0.20 | −1.45±0.13 | −1.24±0.16 |

| 95% CI | −1.61 to −0.86 | −2.03 to −1.24 | −1.71 to −1.18 | −1.55 to −0.93 |

| Difference vs. placebo at day 7, log10 copies/ml | ||||

| Least-squares mean | 0.00±0.24 | −0.39±0.25 | −0.21±0.20 | |

| 95% CI | −0.48 to 0.49 | −0.89 to 0.11 | −0.62 to 0.20 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: unknown§ | ||||

| No. of patients | 9 | 9 | 18 | 13 |

| Least-squares mean change — log10 copies/ml | −0.95±0.56 | −1.98±0.60 | −1.43±0.44 | −1.49±0.63 |

| 95% CI | −2.12 to 0.22 | −3.22 to −0.73 | −2.34 to −0.51 | −2.79 to − 0.19 |

| Difference vs. placebo at day 7 — log10 copies/ml | ||||

| Least-squares mean | 0.54±0.84 | −0.49±0.86 | 0.06±0.76 | |

| 95% CI | −1.20 to 2.28 | −2.27 to 1.30 | −1.51 to 1.63 | |

| At least one Covid-19–related, medically attended visit within 29 days ¶ | ||||

| Full analysis set | ||||

| No. of patients | 92 | 90 | 182 | 93 |

| Patients with ≥1 visit within 29 days — no. (%) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 6 (3) | 6 (6) |

| Difference vs. placebo — percentage points | −3 | −3 | −3 | |

| 95% CI | −18 to 11 | −18 to 11 | −16 to 9 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: negative | ||||

| No. of patients | 41 | 39 | 80 | 33 |

| Patients with ≥1 visit within 29 days — no. (%) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | 5 (6) | 5 (15) |

| Difference vs. placebo — percentage points | −10 | −8 | −9 | |

| 95% CI | −32 to 13 | −30 to 16 | −29 to 11 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: positive | ||||

| No. of patients | 37 | 39 | 76 | 47 |

| Patients with ≥1 visit within 29 days — no. (%) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) |

| Difference vs. placebo — percentage points | 1 | −2 | −1 | |

| 95% CI | −21 to 22 | −23 to 19 | −19 to 17 | |

| Baseline serum antibody status: unknown§ | ||||

| No. of patients | 14 | 12 | 26 | 13 |

| Patients with ≥1 visit within 29 days — no. (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Plus–minus values are least-squares means ±SE. Covid-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019.

The time-weighted average change in viral load was based on an analysis-of-covariance model with treatment group, risk factor, and baseline serum antibody status as fixed effects and baseline viral load and treatment group–by–baseline viral load as covariates. Confidence intervals were not adjusted for multiplicity.

The modified full analysis set excluded patients who tested negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by qualitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction at baseline.

An unknown serum antibody status indicates that the status could not be evaluated or that the results were borderline.

Confidence intervals for the difference (REGN-COV2 minus placebo) were based on the exact method and were not adjusted for multiplicity.

Virologic Efficacy

The prespecified key virologic end point was the time-weighted average change from baseline in viral load through day 7 (log10 scale) in patients in the modified full analysis set who were serum antibody–negative at baseline. In this group, the least-squares mean difference from placebo was −0.52 log10 copies per milliliter (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.04 to 0.00) in the low-dose REGN-COV2 group, −0.60 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −1.12 to −0.08) in the high-dose REGN-COV2 group, and −0.56 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −1.02 to −0.11) in the combined REGN-COV2 group (Table 2). In the overall trial population, the least-squares mean differences from placebo were −0.25 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −0.60 to 0.10), −0.56 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −0.91 to −0.21), and −0.41 log10 copies per milliliter (95% CI, −0.71 to −0.10), respectively.

Additional, post hoc virologic end points included viral load over time and virologic outcomes according to baseline viral load (>104, >105, >106, or >107 copies per milliliter) and according to baseline serum antibody status (Figure 2, Figs. S3 through S5, and Table S2). Similar treatment benefits were observed in the covariate-adjusted (prespecified) and unadjusted (post hoc) analyses (Fig. S4). Patients with the highest viral loads had the largest treatment benefit. In an analysis on a log10 scale involving patients whose baseline viral load was higher than 107 copies per milliliter, the mean reduction in viral load at day 7 was approximately 2-log greater among patients who received REGN-COV2 than among patients who received placebo (Figure 2). Most of the reduction in viral load was evident by trial day 3 (2 days after infusion).

Figure 2. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load over Time.

Shown is the change in mean viral load (in log10 copies per milliliter) from baseline at each visit through day 7 in the overall population (modified full analysis set, which excluded patients who tested negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2] by qualitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction at baseline) and in groups defined according to baseline antibody status and baseline viral load. 𝙸 bars in Panel C indicate the standard error. The least-squares mean difference between the groups in the time-weighted average change in viral load (TWA LS mean) from baseline through day 7, expressed as log10 copies per milliliter, was based on analysis-of-covariance models with treatment group, risk factor, and baseline antibody status as fixed effects and baseline viral load and treatment group–by–baseline viral load as covariates. The lower limit of detection (dashed line) is 714 copies per milliliter (2.85 log10 copies per milliliter).

Clinical Efficacy

The key prespecified clinical end point was the percentage of patients with one or more medically attended visits. In the full analysis set, 6 of 93 patients (6%) in the placebo group and 6 of 182 patients (3%) in the combined REGN-COV2 group had a medically attended visit, a relative difference of approximately 49% (absolute difference vs. placebo, −3 percentage points; 95% CI, −16 to 9). In the serum antibody–negative subgroup, 5 of 33 patients (15%) in the placebo group and 5 of 80 patients (6%) in the combined REGN-COV2 group had a medically attended visit, a relative difference of approximately 59% (absolute difference vs. placebo, −9 percentage points; 95% CI, −29 to 11) (Table 2). Results from a subsequent descriptive analysis involving a larger data set19 indicated that time to alleviation of symptoms was not strongly associated with treatment (or with baseline viral load or baseline serum antibody status) (unpublished data).

Safety

In this interim analysis, both REGN-COV2 doses (2.4 g and 8.0 g) were associated with few and mainly low-grade toxic effects (Table 3 and Table S3). Among the 269 patients in the safety population, the incidence of serious adverse events and adverse events of special interest that occurred or worsened during the observation period, which included grade 2 or higher infusion-related reactions and hypersensitivity reactions, were balanced between the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups and the placebo group. An adverse event of special interest was reported in 2 of 93 patients (2%) in the placebo group and in 2 of 176 patients (1%) in the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups.

Table 3. Serious Adverse Events and Adverse Events of Special Interest in the Safety Population.

| Event | REGN-COV2 | Placebo (N=93) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 g (N=88) |

8.0 g (N=88) |

Combined (N=176) |

||

| number of patients (percent) | ||||

| Any serious adverse event | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Any adverse event of special interest* | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Any serious adverse event of special interest* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grade ≥2 infusion-related reaction within 4 days | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Grade ≥2 hypersensitivity reaction within 29 days | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Adverse events that occurred or worsened during the observation period† | ||||

| Grade 3 or 4 event | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Event that led to death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Event that led to withdrawal from the trial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Event that led to infusion interruption* | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

Events were grade 2 or higher hypersensitivity reactions or infusion-related reactions.

Events listed here were not present at baseline or were an exacerbation of a preexisting condition that occurred during the observation period, which is defined as the time from administration of REGN-COV2 or placebo to the last study visit.

Pharmacokinetics

The mean and individual concentration–time profiles for the components of REGN-COV2 — casirivimab and imdevimab — increased in a dose-proportional manner and were consistent with linear pharmacokinetics for single intravenous doses (Figs. S6 and S7). The mean (±SD) day 29 concentrations of casirivimab and imdevimab in serum were 68.0±45.2 mg per liter and 64.9±53.9 mg per liter, respectively, for the low (1.2 g) doses and 219±69.0 and 181±64.9 mg per liter, respectively, for the high (4.0 g) doses (Table S4); the mean estimated half-life ranged from 25 to 37 days for both antibodies (Table S5).

Discussion

To test the hypothesis that exogenously provided antibodies would have the most benefit in patients whose own immune response had not yet been initiated, our trial first characterized the natural history of Covid-19 and showed that, in the outpatient context, preexisting antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were associated with lower viral loads at baseline and a potential lower likelihood of future medically attended visits. One possible reason for this observation is that patients whose endogenous immune responses were active (serum antibody–positive) were already efficiently clearing the virus, as compared with patients whose immune response had not yet been initiated (serum antibody–negative). These findings are consistent with those in other studies that have shown an association between native antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and viral loads.14,20 Overall, our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that most infected persons successfully recover because of their endogenous immune response.21 This understanding of the natural history of Covid-19 supported our prospective hypothesis that an exogenously provided antibody cocktail would have the most benefit in patients whose own immune response had not yet been initiated, since such patients would have higher baseline viral loads and a higher likelihood of seeking additional medical treatment.

Our data indicate that REGN-COV2 enhanced clearance of virus, particularly in patients in whom an endogenous immune response had not yet been initiated (i.e., serum antibody–negative) or who had a high viral load at baseline. A possible difference in the percentage of patients with medically attended visits was observed between the combined REGN-COV2 dose groups and the placebo group (difference, −3 percentage points; 95% CI, −16 to 9), and this effect was also driven almost entirely by patients who were serum antibody–negative at baseline (difference, −9 percentage points; 95% CI, −29 to 11).

As hypothesized, in patients whose immune response was active at trial entry, the potential to improve this response with an exogenous antibody cocktail was minimal. Administration of such a cocktail did not increase the viral load and therefore did not appear to impede ongoing antiviral activity. In this regard, it may be useful to evaluate the potential for REGN-COV2 to affect long-term immunity to SARS-CoV-2, regardless of patients’ serum antibody status.

Higher viral loads have been correlated with an increased risk of death among hospitalized patients.22 High-titer convalescent-phase plasma may lower the SARS-CoV-2 viral load and thereby reduce the risk of death from Covid-19.23,24 Likewise, in our trial, clearance of the virus was correlated with better clinical outcomes. The neutralizing titers achieved with REGN-COV2 were more than 1000 times the titers achievable with convalescent-phase plasma, and REGN-COV2 had a profound and rapid effect on viral load, with most reduction occurring within 48 hours. This was striking even in the patients with the highest quantifiable viral loads, greater than 107 copies per milliliter; these patients were presumably at the highest risk for additional complications and death. Our results also suggest a testable hypothesis that a shorter time to elimination of viral load would reduce the time of potential infectivity. This hypothesis is being studied in a separate REGN-COV2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT04452318).

The time from the first Covid-19 symptom to randomization was similar in serum antibody–positive patients and serum antibody–negative patients. This observation suggests that symptom onset is not a good predictor of when an immune response is initiated in an individual patient. Similarly, other measures of symptomatology were not strongly correlated with endogenous or exogenously provided antibodies (unpublished data).

The safety of REGN-COV2 was as expected for a fully human antibody against an exogenous target. A low incidence of serious adverse events that occurred or worsened during the observation period and of infusion-related or hypersensitivity reactions was observed.

The pharmacokinetics of each antibody were linear and dose-proportional. Although antidrug-antibody results are not available, no patient had a concentration–time profile in serum that was consistent with altered elimination due to the development of antidrug antibodies. For more than 95% of patients, concentrations of the drug in serum at day 29 were well above the predicted neutralization target concentration based on in vitro and preclinical data. This long half-life of REGN-COV2 suggests that treatment could result in long-term passive immunity for several months. The pharmacokinetic data were similar at each dose of REGN-COV2.

An important limitation of this interim portion of our trial is that, although the analyses according to antibody status were prespecified, no formal hypothesis testing was performed to control type I error; in addition, the analyses according to baseline viral load were post hoc. These results should therefore be rigorously tested in the next analysis in this ongoing trial.

Similar findings showing a reduction in viral load and potential improvement in clinical outcomes were independently reported with a single neutralizing antibody against SARS-CoV-2.25 It was recently shown that an antibody cocktail approach provided a profound survival benefit for patients infected with Ebola virus.26 Our analysis suggests that an antibody cocktail against SARS-CoV-2 can also be an effective antiviral therapy, enhancing viral clearance and thus leading to improved outcomes, particularly in patients whose own immune response to the virus is slow to initiate. Further studies, including the continuing phase 3 portion of this trial, are needed to confirm these effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients; their families; the investigational site members involved in this trial (principal and subprincipal investigators, listed in the Supplementary Appendix); the Regeneron trial team (members listed in the Supplementary Appendix); the members of the independent data and safety monitoring committee; S. Balachandra Dass, Ph.D., Caryn Trbovic, Ph.D., and Brian Head, Ph.D., from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals for assistance with development of an earlier version of the manuscript; and Prime for formatting and copy editing suggestions for an earlier version of the manuscript.

Protocol

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

Data Sharing Statement

This article was published on December 17, 2020, and updated on December 18, 2020, at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and the Biomedical and Advanced Research and Development Authority of the Department of Health and Human Services (contract number HHSO100201700020C).

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, et al. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2302-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavezzo E, Franchin E, Ciavarella C, et al. Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature 2020;584:425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1447-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:362-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2372-2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020;323:2052-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell 2020;181(5):1036-1045.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regeneron and Sanofi provide update on Kevzara® (sarilumab) phase 3 U.S. trial in COVID-19 patients. Regeneron, July 2, 2020. (https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regeneron-and-sanofi-provide-update-kevzarar-sarilumab-phase-3). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roche provides an update on the phase III COVACTA Trial of Actemra/RoActemra in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. Roche, July 29, 2020. (https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2020-07-29.htm). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosas I, Bräu N, Waters M, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. August 27, 2020. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.27.20183442v2). preprint.

- 13.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020;581:465-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum A, Fulton BO, Wloga E, et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science 2020;369:1014-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science 2020;369:1010-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simões EAF, Forleo-Neto E, Geba GP, et al. Suptavumab for the prevention of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infection in preterm infants. Clin Infect Dis 2020. September 8 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baum A, Ajithdoss D, Copin R, et al. REGN-COV2 antibodies prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science 2020;370:1110-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regeneron’s COVID-19 outpatient trial prospectively demonstrates that REGN-COV2 antibody cocktail significantly reduced virus levels and need for further medical attention. Regeneron, October 28, 2020. (https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regenerons-covid-19-outpatient-trial-prospectively-demonstrates). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellinghausen N, Plonné D, Voss M, Ivanova R, Frodl R, Deininger S. SARS-CoV-2-IgG response is different in COVID-19 outpatients and asymptomatic contact persons. J Clin Virol 2020;130:104542-104542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network — United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:993-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magleby R, Westblade LF, Trzebucki A, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral load on risk of intubation and mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2020. June 30 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyner MJ, Senefeld JW, Klassen SA, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma on mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: initial three-month experience. August 12, 2020. preprint.32817978 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li L, Zhang W, Hu Y, et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;324:460-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, Nirula A, Heller B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulangu S, Dodd LE, Davey RT Jr, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of Ebola virus disease therapeutics. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2293-2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.