Abstract

The social distancing mandate, implemented in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic, has guided many schools to deliver instruction via distance learning. Among the many challenges generated by this delivery system is the need for school mental health services, including school suicide prevention and intervention, to be conducted remotely. After briefly discussing the magnitude of the problem of youth suicide and how the COVID-19 pandemic has likely increased risk for youth suicidal ideation and behaviors, this article provides guidance on how school systems can prepare for and conduct suicide risk assessments in distance learning environments.

Keywords: COVID-19, Distance learning, Pandemic, Suicide, Suicide prevention, Suicide intervention, Suicide risk assessment, Telehealth

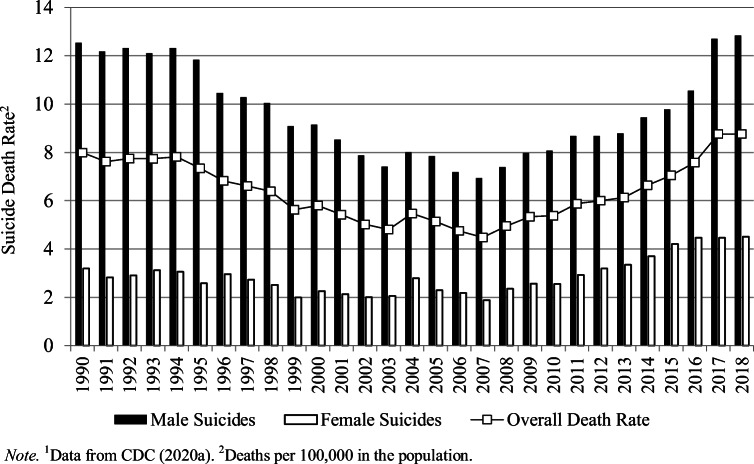

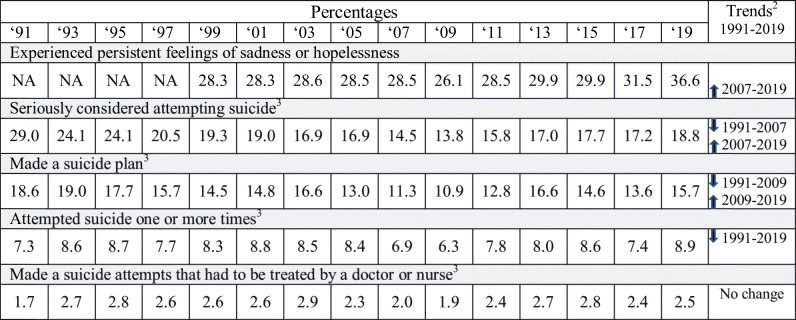

According to the most recent published statistics (from 2018) provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC 2020a, 2020b), suicide among school age youth is a leading cause of death (Table 1). Further, since 2007, the rate of youth suicide deaths has increased (Fig. 1). More recent 2019 statistics, from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), indicate disturbing trends in mental illness and suicide-related behaviors (Table 2). Specifically, US high school students have reported significant increases in suicidal ideation and making a suicide plan (CDC 2020c, August; Ivey-Stephenson et al. 2020; Underwood et al. 2020). Given our observation that YRBS results for suicidal thoughts correlate with both current and subsequent year’s 13- to 18-year-old suicide death rates at the r = 0.6 (p = 0.02) and r = 0.5 (p = 0.06) levels, respectively, we fear that the final 2019 and 2020 suicide death rates will continue to increase.

Table 1.

2018 Youth Suicide Statistics (2017 Statistics1)2

| Age in years | N deaths | Cause of death rank | Suicide rate3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 to 7 | 0 (0) | -- | -- |

| 8 | 2 (1) | 16 (16) | 0.04 (0.02) |

| 9 | 7 (4) | 7 (11) | 0.17 (0.10) |

| 10 | 21 (12) | 5 (7) | 0.50 (0.29) |

| 11 | 54 (42) | 3 (4) | 1.28 (1.01) |

| 12 | 101 (77) | 2 (3) | 2.42 (1.86) |

| 13 | 164 (149) | 1 (2) | 3.95 (3.59) |

| 14 | 256 (237) | 1 (1) | 6.14 (5.75) |

| 15 | 360 (349) | 1 (1) | 8.69 (8.49) |

| 16 | 402 (438) | 2 (2) | 9.73 (10.38) |

| 17 | 467 (469) | 2 (2) | 11.01 (10.93) |

| 18 | 554 (559) | 2 (2) | 12.82 (13.20) |

| Total | 2388 (2337) | 2 (2) | 4.12 (4.03) |

Fig. 1.

Youth ages 13 to 18 years suicide death rates—1991 to 20181. 1Data from CDC (2020a). 2Deaths per 100,000 in the population

Table 2.

Youth risk behavior survey trends in mental health and suicide-related behavior prevalence: 1991–20191

Clearly, these observations, in and of themselves, increase the need for coordinated and comprehensive school suicide prevention efforts. However, we suggest that challenges associated with COVID-19 further increase the need for these services. Specifically, school closures and requirements for social distancing have the potential to generate feelings of isolation and loneliness, which are primary suicide risk factors (Calati et al. 2019; Gagnon et al. 2009; Hazler and Denham 2002; Holland et al. 2017), and reduce access to critical mental wellness resources (NASP 2015). Obviously, this will exacerbate the impact of pre-existing depression and anxiety. In addition, coping with the ongoing uncertainty of the pandemic’s course, the effects of economic stress generated by job losses on the family (Ström 2003), and the traumatic stress associated with the threat of getting sick (Triantafyllou and Matziou 2019), having significant others ill, or deceased may also challenge mental wellness and increase suicide risk. Perhaps most powerfully, Czeisler et al. (2020) report that 25.5% of young US adults (ages 18 to 24 years) reported having seriously considered suicide at some point during late May and June 2020. Among adults currently being treated for PTSD, 44.8% reported suicidal ideation.

Combining these observations, now more than ever, powerfully advocate for school suicide prevention. However, to the extent schools continue to offer distance learning options, existing suicide risk assessment and intervention protocols need to be modified, and it is with this in mind that volunteer leaders within the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP; the authors of this paper) developed several documents designed to provide guidance on the delivery of comprehensive suicide prevention in the distance learning environment (Lieberman et al. 2020; NASP 2020a, 2020b). To our knowledge, no other professional associations have offered such guidance (however, the American School Counselor Association n.d. does offer a virtual school counseling crisis response toolkit). Thus, we offer the remainder of this paper as a source of some guidance on how to prepare for, and how to conduct, suicide risk assessment when students are in virtual classrooms.

Before proceeding further, it is important to acknowledge that the empirical literature offers little guidance on conducting suicide risk assessments via telehealth. For example, while a PsycINFO database search using the terms “suicide risk assessment” and “virtual or online or distance or web-based or remote,” returned a listing of 55 articles (all published since 2006), none of them addressed school suicide risk assessment or using telehealth to assess the suicidality of children or adolescents. Further, many of these articles discussed web-based suicide risk assessment training or data collection for research purposes. However, we did identify several that addressed use of web-based tools for working with suicidal adult clients that suggested this approach to be promising (Godleski et al. 2008; Haas et al. 2008; Harned et al. 2017). Given this void in the empirical literature, we would like to take this opportunity to strongly encourage that research be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of these procedures and that pending such evaluation school districts should proceed cautiously.

Preparing for School Suicide Risk Assessment in a Time of Distance Learning

As delineated by Lieberman et al. (2020), providing school suicide prevention remotely conveys a number of opportunities and challenges, which schools need to attend to as they prepare to deliver these services. More specifically, particular preparedness steps recommended by NASP (2020b) are summarized in Table 3. Preparing for suicide risk assessment in the distance learning environment begins by examining existing school suicide prevention policies, procedures, and protocols and then modifying them to include the use of telehealth. For example, they need to consider how school-employed mental health professionals (i.e., school counselors, psychologists, social workers, and nurses) connect with students virtually and remotely secure student safety and supervision. This should include identifying those local resources (e.g., local law enforcement, mobile crisis response teams, children, and family services) that are available to immediately respond to a student’s location. While most states have laws that require or permit mental health professionals to disclose information about individuals who may be a danger to themselves or others (National Conference of State Legislatures 2018), before initiating any form of telehealth, familiarity with state telehealth laws is important, and consultation with school district legal counsel is advised (Lieberman et al. 2020).

Table 3.

Preparing for school suicide risk assessment in a distance learning environment

| 1. Review and modify existing policies, protocols, and procedures for use in the distance learning environment. | |

| 2. Identify community suicide intervention response resources. | |

| 3. Train staff to identify suicide risk factors and warning signs within the virtual classroom. | |

| 4. Provide staff with guidelines for responding to imminent suicide behavior situations. | |

| 5. Review with staff suicide risk assessment referral procedures and emphasize how they have been modified for the distance learning environment. | |

| 6. Develop telehealth skills. | |

| 7. Develop telehealth delivery options and platforms. | |

| 8. Ensure staff who conduct suicide risk assessment via telehealth have access to all current and updated student contact information. | |

| 9. Ensure staff who conduct suicide risk assessment have access to community suicide intervention response resources. | |

| 10. Develop caregiver telehealth consent procedures. | |

| 11. Develop suicide intervention procedures for situations wherein caregiver consent cannot be obtained. |

Adapted from NASP (2020b)

Next, just as is the case during traditional instructional delivery, NASP (2020b) recommends that school employed mental health professionals work to ensure all school staff members are aware of suicide risk factors and warning signs. This training may make use of a distance learning option, and such webinars should clearly articulate how COVID-19 likely increases suicide risk and how suicide-related behavior might be observed during online instructional delivery. When approaching these trainings and given the demands experienced by school staff, as they work to embrace new instructional strategies and develop proficiency with new technology, trainers should consider a training strategy that occurs in steps. The process of primary training meetings paired with follow-up sessions and resources (webinars, print reference material, electronically delivered summary sheets) should be considered. This allows teachers who are typically in the position of gatekeeper to develop a functional understanding of this critical topic.

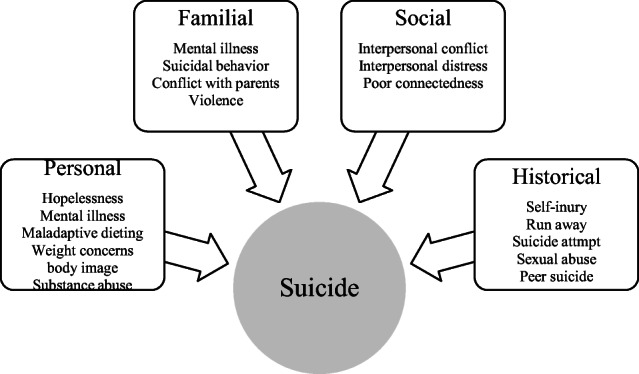

We define risk factors, which are illustrated in Fig. 2, as those variables that increase the odds of a student becoming suicidal. In particular, hopelessness and depression should be identified as factors that distinguish youth with suicidal ideation from those without such thoughts and a history of suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury identified as the most important variables distinguishing those who make a suicide attempt from those with only thoughts of suicide (Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp 2014). When risk factors are observed, school staff should be trained to look for the warning signs of suicidal thinking, which are the concrete indications of suicidality (Joe and Bryant 2007). Staff should be trained to look for communications and behaviors that signal the possible presence of suicidal thinking (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Risk factors for youth suicide. Adapted from Brock and Lourvar Reeves (2018). Sources include Bilsen (2018), Burón et al. (2016), Cwik et al. (2015), du Roscoät et al. (2016), Taliaferro and Muehlenkamp (2014), Thullen et al. (2016), and Yildiz et al. (2018)

Table 4.

Suicidal thinking warning sign examples

| Expressive | Behavioral | |

|---|---|---|

| Direct |

Writing suicide notes Writing a will Saying “I want to die” Saying “My death is the only way out” Saying “I have no reason to live” |

Giving away prized possessions Sudden, unexpected happiness Significant risk taking Researching suicide methods Calling/visiting to say “goodbye” |

| Indirect |

Writings that include death themes Saying “I wish I would never wake up” Saying “You will be better off without me” Saying “Things will never get better” Saying “The pain is unbearable” Art with themes of death |

Increased substance use Academic decline Aggression Isolating self from family/friends Refusing help Sudden decline in appearance |

Adapted from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2020)

Staff suicide prevention trainings should also include the identification and contact information for the school employed mental health professional who conduct suicide risk assessments (and how making such contact has been modified for the distance learning environment). However, given that school employed mental health professionals are not physically available to teachers in the distance learning environment, and that a timely risk assessment capable of ensuring student safety may not be possible, it is important for teachers to be given guidance on how to respond to an imminent risk situation. Teachers should be helped to understand the difference between suicidal thoughts and circumstances signaling a suicidal behavior is imminent (e.g., student is alone, a threat has been made, and suicide means are readily available). In these situations, they should be directed to provide as much direct supervision as soon as possible, call 911, and ask for a wellness.

Telehealth skill development is an essential preparedness task and important not only for the immediate risk assessment but also for the suicide intervention and longer-term mental health care that suicidal thinking typically requires (Holland et al. 2020). Lieberman et al. (2020) provide comprehensive guidance on telehealth considerations, as well as guidance on virtual service delivery and virtual service resources.

A basic, yet essential preparedness task is to ensure that the school employed mental health professionals responsible for risk assessment has ready access to important contact information. Specifically, they must have access to regularly updated and current student demographic data (i.e., name, address, phone numbers, email, and complete contact information for primary caregivers). In addition, it is critical that they have ready access to the school and community crisis response resources that provide immediate consultation and crisis intervention response.

A final prerequisite to providing school suicide risk assessment in the distance learning environment involves the development of telehealth informed consent procedures. As discussed by Fielding (2020), these procedures should (a) describe telehealth service delivery and specify technical considerations, (b) explain how service providers operate and the limits of telehealth, (c) delineate student expectations and responsibilities of all parties involved, (d) identify emergency contacts and specify multiple communication options, (e) obtain consent for specific service providers to offer telehealth, and, finally, (f) telehealth consent procedures should be reviewed by district legal counsel to ensure compliance with state and federal regulations. Supplementing these consent procedures, schools should have a plan and response options for those situations wherein consent is not, or cannot be, obtained. Regarding this issue, we recognize that NASP’s (2020c) Principles for Professional Ethics offers:

It is ethically permissible to provide psychological assistance without parental notice or consent in emergency situations or if there is reason to believe a student may pose a danger to others; is at risk for self-harm; or is in danger of injury, exploitation, or maltreatment. (p. 42)

Conducting School Suicide Risk Assessment in a Time of Distance Learning

Building upon the foundation offered by completion of the just discussed preparedness tasks, specific school suicide risk assessment steps need to be specified, and the steps recommended by NASP (2020a) are summarized in Table 5. Conducting suicide risk assessment in the distance learning environment begins with retrieval of the at-risk student’s primary caregiver’s contact information and determining where they are physically located. This should include documentation of multiple and redundant communication channels (e.g., all available landlines, cell phone numbers, email addresses). Once caregiver contact is established, permission to conduct a suicide risk assessment is sought, reason for referral clarified, immediate recommendations for student care and supervision offered (e.g., if the caregiver is not physically with the at-risk student recommend that they re-establish physical contact), and agree on what to do if the caregiver unexpectedly becomes unavailable. This element of the distance learning risk assessment protocol also needs to include the district protocol for what to do if consent to conduct the risk assessment is not given (e.g., calling protective services or law enforcement and asking for a wellness check), as well as how to facilitate emergency response intervention (i.e., calling 911) when indicated. Given the challenging nature of suicide risk assessment, schools should also develop a protocol to ensure that as soon as a request for support is made by any staff member, a team of at least two appropriately credentialed school employed mental health professionals are made available for the risk assessment.

Table 5.

Conducting school suicide risk assessment in a distance learning environment

| 1. Retrieve primary caregiver’s contact information and determine their location. | |

| 2. Contact primary caregiver and obtain informed consent. | |

| a. Follow district protocol if consent cannot or is not given. | |

| 3. Document suicide risk factors and warning signs. | |

| 4. Retrieve student’s contact information and determine their exact physical location. | |

| 5. Contact student and obtain assent to conduct the risk assessment. | |

| a. Follow district protocol if assent is not given. | |

| b. Call 911 if there is a direct and imminent suicide threat. | |

| c. Call 911 if the student terminates the assessment without reason or warning. | |

| 6. Conduct a suicide risk assessment interview. | |

| 7. Communicate risk assessment results to primary caregivers and collect additional risk assessment data. | |

| 8. Determine risk level, select interventions, and develop a safety plan. | |

| 9. Develop an action plan for the primary caregivers. | |

| 10. Share action plan with school and community crisis intervention resources. | |

| 11. Begin to develop a plan for the student’s return to the learning/classroom environment. |

Adapted from NASP (2020a)

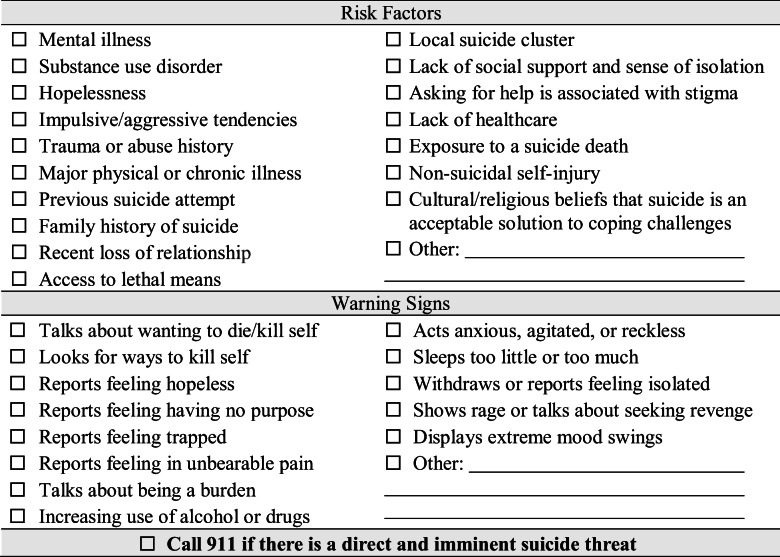

Next, the suicide risk assessment should document the risk factors and suicide warning signs that generated the referral. As indicated, contact with community emergency response personnel (i.e., calling 911) is made if there is evidence of a direct and immediate risk of suicidal behavior, and the student lacks supervision. The risk factor and warning signs checklist offered by NASP ( 2002; which was originally adapted from Suicide Awareness Voices of Education [SAVE], 2020) is offered in Table 6.

Table 6.

Suicide risk factors and warning signs checklist

From NASP (2020a)

With the reason for referral documented, the next step is retrieval of the at-risk student’s contact information and determining where they are physically located. This should include documentation of multiple and redundant communication channels (e.g., all available landlines, cell phone numbers, email addresses). Once contact with the student at-risk is established, assent to conduct a suicide risk assessment is sought and reason for referral clarified. This element of the distance learning risk assessment also needs to include the district’s protocol for what to do if consent to conduct the risk assessment is not given or the student terminates the risk assessment suddenly and without warning (e.g., calling local law enforcement and asking for a wellness check). Regarding such situations, it is important to acknowledge that NASP (2020c) offers that “…it is ethically permissible to bypass student assent to services if the service is considered to be of direct benefit to the student and/or is required by law” (p. 43).

Next, the suicide risk assessment itself begins, and here we judge it important to acknowledge that NASP (2020c) asserts that:

… if a child or adolescent is in immediate need of assistance, it is permissible to delay the discussion of confidentiality until the immediate crisis is resolved. School psychologists recognize that it may be necessary to discuss confidentiality at multiple points in a professional relationship to ensure the client’s understanding and agreement regarding how sensitive disclosures will be handled. (pp. 43-44)

As soon as suicidal thinking is verified, it is important to ask if the student has already done anything to kill themselves. If they have already engaged in a suicidal behavior immediately call 911 (SWHelper 2018). When conducting risk assessments via telehealth, it is important to acknowledge that the need to make such 911 calls is increased. When these assessments are conducted in the brick and mortar school building, school staff members have a much greater ability to control a situation than they do in the distance learning environment. Thus, if there is a direct and imminent threat and/or the student terminates the assessment without warning, a 911 call is indicated. NASP (2020a) recommends that the risk assessment includes the questions specified in Table 7 and includes inquiry about the severity of suicidal thinking, degree of suicide planning, history of prior suicide thoughts and behavior, as well as completion of established district approved suicide risk assessment measures (such as the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale; Columbia Lighthouse Project 2016).

Table 7.

Suicide risk assessment questions

| Suicide thoughts | |

|

Are you thinking about suicide? How often do you think about suicide? Have you been researching suicide online? Have you shared your thoughts about suicide with anyone? Who can you talk to that can help you cope with suicidal thinking? | |

| Suicide plan | |

|

Do you have a suicide plan? How would you kill yourself? Do you have the means to carry out your plan? When will you carry out your plan? | |

| Prior suicide thoughts and behaviors | |

|

Have you had thoughts of suicide in the past? Have you ever tried to kill or hurt yourself in the past? If yes, when? Was there anyone that helped you cope with your prior suicidal thinking? |

From NASP (2020a)

After having interviewed the student, we recommend that the primary caregiver be interviewed (NASP 2020a). Specific questions to be asked include:

Has your child displayed abrupt behavior changes?

What is your child’s current support system?

Is there a history of mental illness?

Is there a history of recent losses, trauma, or bullying?

Has your child ever tried to harm themselves before?

Have they ever attempted to kill themselves before?

With risk assessment and primary caregiver data at hand, the next step is to determine the risk level and from these data sources to consider interventions and develop safety plans. We suggest risk levels to be:

Low risk (i.e., current thoughts of suicide, but no suicide plan, acknowledges helping resources)

Moderate risk (i.e., prior attempt, thoughts of and plan for behavior or no resources, but no time frame for behavior)

High risk (i.e., thoughts of suicide, plan for behavior, time frame for behavior specified, and no helping resources)

Suggested intervention plan options include (a) providing 24/7 resource numbers, (b) connecting with school/community resources, (c) calling 911 and asking for a wellness check, (d) mobilizing prosocial support systems, (e) identifying specific caring adults, (f) promoting communication and coping, and (g) providing treatment referrals.

In addition to identifying interventions and developing a safety plan for the student, NASP (2020a) recommends that a primary caregiver action plan also be developed. Suggested elements for these plans include (a) increasing supervision, (b) providing constant supervision (including when they are in a bathroom), (c) restricting access to possible suicide means, (d) providing 24/7 resource numbers, (e) making immediate treatment referrals, (f) mobilizing prosocial support systems, (g) connecting with school/community resources, (h) arranging for transportation, and (i) making a child protective services referral.

Having identified interventions and a safety plan for the student at risk, and having developed an action plan for the student’s primary caregivers, NASP (2020a) recommends school employed mental health professionals consult with school and community crisis intervention resources and (with the appropriate caregiver permission) share risk assessment data and intervention elements. It is important to acknowledge that following these consultations, modifications to the proposed interventions and plans may need to be made, especially, given that school employed mental health professionals typically do not find suicide risk assessments to be a regular part of their professional duties.

Finally, as a last step in this process, NASP (2020a) recommends obtaining consent to obtain and exchange confidential information with treatment providers. Here, we recognize that consent for disclosure of such information is both a legal and ethical requirement. However, we note that NASP (2020c) offers that such may not be required “in those situations in which failure to release information could result in danger to the student or others, or where otherwise required by law” (p. 44). With such permissions in hand, contacts with community-based therapists (who are helping to address the challenges that led to suicidal thoughts) are made. These communications should identify how the school can support the student’s treatment and begin to address re-entry to the learning environment. Such re-entry should include working with the student’s teachers, reminding them of suicide warning signs, and developing a plan to monitor the student for suicidal thoughts. The need for such planning is emphasized by the observation that prior attempts are common among youth suicide deaths (Keeshin et al. 2018).

Concluding Comments

The past decade has seen disturbing trends in youth mental illness, suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and deaths; and we suggest that challenges associated with COVID-19 further increase the need for schools to be vigilant for suicide risk factors and warning signs. School closures and requirements for social distancing may generate feelings of isolation and loneliness, which are primary suicide risk factors. In addition, coping with the ongoing uncertainty of the pandemic’s course, the stress generated by economic uncertainty and job losses, and the traumatic stress associated with the threat of getting sick, having significant others ill, or deceased may further increase suicide risk. With this reality in mind, we hope that this paper helps schools overcome some of the challenges associated with conducting suicide risk assessments in the distance learning environment. We appreciate that such guidance will not make this a simple or straightforward task and, consequently, recommend that school districts mobilize a suicide prevention task force to tailor these protocols to unique local needs and resources. We also want to emphasize the importance of school employed mental health professionals always seeking consultation support when conducting these assessments. In addition, we acknowledge that in the distance learning environment, the use of community resources and making requests for wellness checks will be more likely (and necessary) occurrences. What was, in the brick and mortar school building, a response wherein we supervised a student at school until the student could be physically delivered to primary caregivers is now much more likely to be a 911 phone call.

Biographies

Stephen E. Brock

, Ph.D., NCSP, is a Professor and Coordinator of the School Psychology Program at California State University, Sacramento.

Richard Lieberman

, NCSP, is a Lecturer at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA.

Melinda A. Cruz

, Ph.D., NCSP, is an Assistant Professor at Radford University, Radford, VA.

Robert Coad

, LEP is a school psychologist with the Walnut Valley Unified School District, Walnut, CA.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

This document does not contain legal advice and should not be relied upon to give guidance regarding local or state laws, rules, or policies. Consultation with school district counsel is recommended before implementing the practices described in this paper.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. (2020). Risk factors and warning signs.https://afsp.org/risk-factors-and-warning-signs#warning-sign%2D%2Dtalk. Accessed Sept 2020

- American School Counselor Association. (n.d.) ASCA Toolkit: crisis planning and response during a pandemic/virtual school counseling.https://www.schoolcounselor.org/school-counselors/professional-development/learn-more/crisis-planning-and-response. Accessed Sept 2020

- Bilsen, J. (2018). Suicide and youth: risk factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brock SE, Lourvar Reeves MA. School suicide risk assessment. Contemporary School Psychology. 2018;22(2):174–185. doi: 10.1007/s40688-017-0157-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burón P, Jimenez-Trevino L, Saiz PA, García-Portilla MP, Corcoran P, Carli V, Fekete S, Hadlaczky G, Hegerl U, Michel K, Sarchiapone M, Temnik S, Värnick A, Verbanck P, Wasserman D, Schmidtke A, Bobes J. Reasons for attempted suicide in Europe: prevalence, associated factors, and risk of repetition. Archives of Suicide Research. 2016;20(1):45–58. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R, Ferrari C, Brittner M, Oasi O, Olié E, Carvalho AF, Courtet P. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: a narrative review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;245:653–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020a). Fatal injury reports, national, regional, and state, 1981-2018.https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. Accessed Sept 2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020b). Leading cause of death reports, 1981-2018. https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcause.html. Accessed Sept 2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020c). Trends in the prevalence of suicide-related behaviors national YRBS: 1991-2019.https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/factsheets/2019_suicide_trend_yrbs.htm. Accessed Sept 2020

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Youth risk behavior survey data summary and trends report: 2007 – 2017.https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf. Accessed Sept 2020

- Columbia Lighthouse Project. (2016). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).https://cssrs.columbia.edu. Accessed Sept 2020

- Cwik M, Barlow A, Tingey L, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, Craig M, Walkup JT. Exploring risk and protective factors with a community sample of American Indian adolescents who attempted suicide. Archives of Suicide Research. 2015;19(2):172–189. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., Shantha, M. W., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic – United States, June 24-30, 2020. MMWR, 69(32), 1049–1057 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/pdfs/mm6932a1-H.pdf. Accessed Sept 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- du Roscoät E, Legleye S, Guignard R, Husky M, Beck F. Risk factors for suicide attempts and hospitalizations in a sample of 39,542 French adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;190:517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, R. (2020). Telehealth service provision handbook. Andover Public Schools. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1amSVnM4yL7WECncmVKQ8CFRGEgjcbk4Y/view.

- Gagnon A, Davidson SI, Cheifetz PN, Martineau M, Beauchamp G. Youth suicide: a psychological autopsy study of completers and controls. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2009;4(1):13–22. doi: 10.1080/17450120802270400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godleski L, Nieves JE, Darkins A, Lehmann L. VA telemental health: suicide assessment. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2008;26(3):271–286. doi: 10.1002/bsl.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas A, Koestner B, Rosenberg J, Moore D, Garlow SJ, Sedway J, Nicholas L, Hendin H, Mann JJ, Nemeroff CB. An interactive web-based method of outreach to college students at risk for suicide. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57(1):15–22. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.1.15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harned MS, Lungu A, Wilks CR, Linehan MM. Evaluating a multimedia tool for suicide risk assessment and management: the Linehan Suicide Safety Net. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;73(3):308–318. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazler RJ, Denham SA. Social isolation of youth at risk: conceptualizations and practical implications. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2002;80(4):403–409. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00206.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holland KM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Logan JE, Leemis RW. Antecedents of suicide among youth aged 11–15: a multistate mixed methods analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46(7):1598–1610. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0610-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, M., Hawks, J., Morelli, L., & Khan, Z. (2020). Risk assessment and crisis intervention for youth in a time of telehealth. Unpublished manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ivey-Stephenson, A. Z., Demissie, Z., Crosby, A. E., Stone, D. M., Gaylor, E., Wilkins, N., Lowry, R., & Brown, M. (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students – Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR, 69(Supp. 1), 1–55 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/su/pdfs/su6901a6-H.pdf. Accessed Sept 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Joe S, Bryant H. Evidence-based suicide prevention screening in schools. Children & Schools. 2007;29(4):219–227. doi: 10.1093/cs/29.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeshin BR, Gray D, Zhang C, Presson AP, Coon H. Youth suicide deaths: investigation of clinical predictors in a statewide sample. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2018;48(5):601–612. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, R., Cruz, M. A., Coad, R., & Brock, S. E. (2020). Comprehensive school suicide prevention in a time of distance learning (Handout). National Association of School Psychologists. https://www.nasponline.org/Documents/Resources%20and%20Publications/Resources/Crisis/Comprehensive%20School%20Suicide%20Prevention_COVID-19_FINAL.pdf. Accessed Sept 2020

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2015). The importance of mental and behavioral health services for children and adolescents (Position statement). https://www.nasponline.org/research-and-policy/policy-priorities/position-statements. Accessed Sept 2020

- National Association of School Psychologists (2020a). Conducting school suicide intervention in a time of distance learning: an intervention checklist.https://www.nasponline.org/x55254.xml. Accessed Sept 2020

- National Association of School Psychologists (2020b). Preparing for school suicide intervention in a time of distance learning: a prevention checklist.https://www.nasponline.org/x55253.xml. Accessed Sept 2020

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2020c). The professional standards of the National Association of School Psychologists.https://www.nasponline.org/standards-and-certification/professional-ethics. Accessed Sept 2020

- National Conference of State Legislatures. (2018). Mental health professionals’ duty to warn.https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx. Accessed Sept 2020

- Ström S. Unemployment and families: a review of research. Social Service Review. 2003;77(3):399–430. doi: 10.1086/375791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (SAVE) (2002). About suicide.https://save.org/about-suicide/. Accessed Sept 2020

- SWHelpler. (2018). Virtual crisis intervention: wave of the future?https://swhelper.org/2018/09/13/virtual-crisis-intervention-wave-of-the-future/. Accessed Sept 2020

- Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Risk and protective factors that distinguish adolescents who attempt suicide from those who only consider suicide in the past year. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(1):6–22. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thullen MJ, Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents engaged in risk behaviors: a latent class analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2016;26(3):587–594. doi: 10.1111/jora.12199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllou C, Matziou V. Aggravating factors and assessment tools for posttraumatic stress disorder in children after hospitalization. Psychiatriki. 2019;30(3):256–266. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2019.303.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, J. M., Brener, N., Thornton, J., Harris, W. A., Bryan, L. N., Shanklin, S. L., Deputy, N., Roberts, A. M., Queen, B., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Lim, C., Yamakawa, Y., Leon-Nguyen, M., Kilmer, G., Smith-Grant, J., Demissie, Z., Sherry Everett Jones, S., Clayton, H., & Dittus, P. (2020). Overview and methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System – United States, 20019. MMWR, 69(Supp. 1), 1–83 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/su/pdfs/su6901-H.pdf. Accessed Sept 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yildiz M, Orak U, Walker MH, Solakoglu O. Suicide contagion, gender, and suicide attempts among adolescents. Death Studies. 2018;43(6):365–371. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1478914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

= significant decrease and

= significant decrease and  = significant increase

= significant increase