Abstract

Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-expressing T cells are effective treatment for B-cell lymphoma but often cause neurologic toxicity. We treated 20 patients with B-cell lymphoma on a phase I, first-in-humans clinical trial of T cells expressing the novel anti-CD19 CAR Hu19-CD828Z (NCT02659943). The primary objective was to assess safety and feasibility of Hu19-CD828Z T-cell therapy. Secondary objectives included assessments of CAR T-cell blood levels, anti-lymphoma activity, second infusions, and immunogenicity. All objectives were met. Fifty-five percent of patients who received Hu19-CD828Z T cells obtained complete remissions. Hu19-CD828Z T cells had similar clinical anti-lymphoma activity as T cells expressing FMC63–28Z, an anti-CD19 CAR tested previously by our group that contains murine binding domains and is used in axicabtagene ciloleucel. However, severe neurologic toxicity occurred in only 5% of patients who received Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus 50% of patients who received FMC63–28Z T cells (P=0.0017). T cells expressing Hu19-CD828Z released lower levels of cytokines than T cells expressing FMC63–28Z. Lower levels of cytokines were detected in blood of patients receiving Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells, which could explain the lower level of neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z. Levels of cytokines released by CAR-expressing T cells particularly depended on the hinge and transmembrane domains included in the CAR design.

Development of anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells has been a major advance in lymphoma treatment1–15. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cells induce durable complete remissions (CR) in approximately 40% of patients with relapsed, chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)5–8,16 and effectively treat other lymphoma types5,8.

Toxicities, including cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) and especially neurologic toxicities, are important problems with anti-CD19 CAR T cells1,3,5,17–20. CRS has prominent manifestations of fever, tachycardia, and hypotension17–19. CRS is associated with elevated blood levels of many cytokines that are released by CAR T cells and other recipient cells1,17,19,21,22.

Neurologic toxicity after CAR T-cell infusions has a variety of manifestations including encephalopathy, tremor, and dysphasia4,5,17–19,23–25. The mechanisms causing neurologic toxicity are not completely understood; however, important factors likely include release of neurotoxic substances including cytokines by CAR T cells and other immune cells, endothelial activation, blood-brain-barrier breakdown, and possibly presence of CAR T cells in the central nervous system1,5,23,24,26,27.

In a previous clinical trial of anti-CD19 CAR-expressing T cells conducted by our group, 55% of patients obtained CR; however, 50% of patients experienced severe (Grade 3 or 4) neurologic toxicity, which was the most important class of toxicity on this previous clinical trial5.

We demonstrated in prior work that CARs with CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains caused weaker T-cell activation and lower levels of cytokine release compared with CARs incorporating CD28 hinge and transmembrane domains28. We designed an anti-CD19 CAR designated Hu19-CD828Z that contained a single-chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from a fully-human anti-CD19 antibody plus hinge and transmembrane domains from CD8α28. We initiated a clinical trial of Hu19-CD828Z based on 2 hypotheses. First, a scFv derived from a human antibody might be less immunogenic than a scFv derived from a murine antibody. Second, T cells expressing a CAR with CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains plus a CD28 costimulatory domain might release low levels cytokines and cause low levels of clinical toxicity.

Here, we report results from the first-in-humans trial of Hu19-CD828Z T cells. We also compared results with Hu19-CD828Z-expressing T cells and results from a previous clinical trial that tested T cells expressing an anti-CD19 CAR designated FMC63–28Z5. T cells expressing FMC63–28Z have been commercially developed as axicabtagene ciloleucel. Compared with the earlier FMC63–28Z CAR, there was a strikingly lower level of neurologic toxicity with the new Hu19-CD828Z CAR.

Results

Hu19-CD828Z design

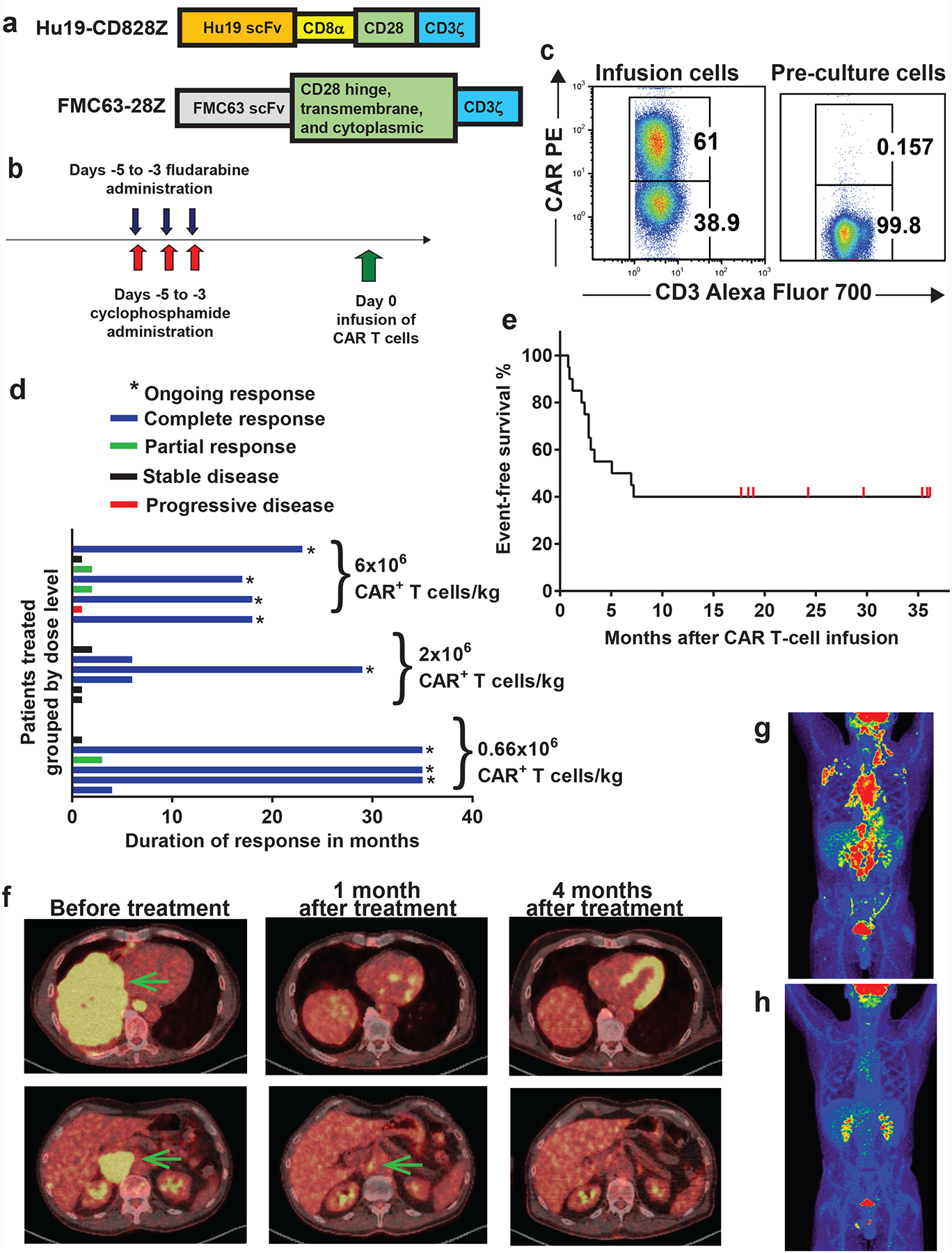

Hu19-CD828Z had a scFv from a fully-human anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody, CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains, a CD28 costimulatory domain, and a CD3ζ activation domain (Figure 1a). Hu19-CD828Z was encoded by a lentiviral vector (LSIN, lentivirus self-inactivating)28. FMC63–28Z had a murine scFv, hinge, transmembrane and costimulatory domains from CD28, and a CD3ζ activation domain5,29. FMC63–28Z was encoded by a gamma-retroviral vector called mouse stem cell virus-based splice-gag vector (MSGV)30.

Figure 1. Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells have substantial anti-lymphoma activity.

(a) Hu19-CD828Z contained the Hu19 human scFv, CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains, the CD28 cytoplasmic domain, and a CD3ζ domain. FMC63–28Z was used in prior clinical trials. FMC63–28Z had a scFv from a murine antibody, hinge, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains from CD28, and a CD3ζ domain. (b) The clinical protocol included a CAR T-cell infusion preceded by conditioning chemotherapy of cyclophosphamide 300mg/m2/day and fludarabine 30mg/m2/day both daily for 3 days. (c) Hu19-CD828Z expression on infusion CAR T cells of Patient 12 was assessed by staining with the anti-CAR antibody and anti-CD3. Staining of pre-culture PBMC from Patient 12 is shown as a control. Similar results were obtained with all 20 patients that received Hu19-CD828Z T cells. (d) Durations of response are shown. Duration of response was from the day of 1st response until one of the following: progressive lymphoma, the patient started a different lymphoma therapy, or latest documented ongoing response; (*) indicates ongoing response at last follow-up. (e) Event-free survival of all 20 patients is shown. (f) Patient 6 obtained an ongoing CR of DLBCL. Yellow areas indicated by the arrows on the PET-CT scan are lymphoma. Lymphoma resolved after Hu19-CD828Z CAR T-cell infusion. The yellow areas in the heart and kidneys are from accumulation of radiotracer, not lymphoma. (g) PET-CT scan of Patient 13 shows areas of follicular lymphoma as red and yellow before CAR T-cell treatment and (h) disappearance of lymphoma after CAR T-cell treatment. Brain, kidneys, and bladder are normally red or yellow because of high metabolism and accumulation of radiotracer.

Clinical trial design and infused cells

The Hu19-CD828Z clinical protocol included conditioning chemotherapy to enhance function and proliferation of CAR T cells31–34. The conditioning chemotherapy was 3 daily doses of 300 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide plus 30 mg/m2 of fludarabine (Figure 1b). The trial assessed 3 CAR T-cells doses, 0.66×106, 2×106, and 6×106 CAR+ T cells/kg of patient bodyweight (Table 1).

Table 1 :

Patient characteristics, responses and adverse events

| Patient number | Lymphoma type | Number of prior lines of therapy | Lymphoma status* | CAR+ T-cell dose (per kg body weight) | Best response (duration in months)# | CRS Grade** | Maximum neurologic adverse event Grade& |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–1st treatment | DLBCL transformed from follicular lymphoma | 6 | Chemorefractory | 0.66×106 | SD (1) | 1 | <2 |

| 1–2nd treatment | 2×106 | PR (1) | No CRS | <2 | |||

| 2 | Follicular lymphoma | 4 | Neither | 0.66×106 | CR (35+) | No CRS | <2 |

| 3 | Follicular lymphoma | 9 | Neither | 0.66×106 | PR (3) | 2 | 4 |

| 4–1st treatment | DLBCL | 2 | Chemorefractory | 2×106 | SD (2) | 2 | <2 |

| 4–2nd treatment | 2×106 | SD (1) | 1 | <2 | |||

| 4–3rd treatment | 6×106 | SD (2^) | 1 | <2 | |||

| 5 | DLBCL, double-hit | 3 | Relapse 5 months after ASCT | 0.66×106 | CR (35+) | 2 | <2 |

| 6 | DLBCL | 4 | Relapse 9 months after ASCT | 0.66×106 | CR (35+) | 2 | <2 |

| 7–1st treatment | DLBCL, double-hit | 2 | Neither | 0.66×106 | CR (4) | 2 | <2 |

| 7–2nd treatment | 2×106 | PD | 2 | <2 | |||

| 8 | Mantle cell lymphoma | 1 | Neither | 2×106 | CR (6) | 4 | 2 |

| 9 | Burkitt lymphoma | 2 | Chemorefractory | 2×106 | CR (29+) | 2 | <2 |

| 10–1st treatment | DLBCL transformed from follicular lymphoma | 3 | Relapse 3 months after ASCT | 2×106 | CR (6) | No CRS | <2 |

| 10–2nd treatment | 6×106 | PR (1) | 1 | <2 | |||

| 11 | DLBCL, triple hit | 4 | Chemorefractory | 2×106 | SD (1) | 1 | <2 |

| 12 | DLBCL | 6 | Neither | 2×106 | SD (1) | No CRS | <2 |

| 13 | Follicular lymphoma | 6 | Neither | 6×106 | CR (23+) | 3 | <2 |

| 14 | DLBCL | 2 | Chemorefractory | 6×106 | SD (1) | 1 | 2 |

| 15 | DLBCL transformed from CLL | 4 | Chemorefractory | 6×106 | PR (2) | 1 | <2 |

| 16 | DLBCL, double hit | 3 | Chemorefractory | 6×106 | CR (17+) | 1 | <2 |

| 17 | DLBCL | 5 | Neither | 6×106 | PR (2) | 2 | <2 |

| 18 | Mantle cell lymphoma | 4 | Neither | 6×106 | CR (18+) | 2 | <2 |

| 19 | DLBCL, triple hit | 4 | Chemorefractory | 6×106 | PD | 2 | <2 |

| 20 | DLBCL | 2 | Neither | 6×106 | CR (18+) | 2 | 2 |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CR, complete remission; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Chemotherapy refractory (chemorefractory) was defined as failure to obtain PR or CR after the most recent cytotoxic chemotherapy. Relapse after ASCT is listed if the lymphoma had relapsed after ASCT when ASCT was the last line of therapy before protocol enrollment, and in addition, the lymphoma was not proven to be chemotherapy-refractory at the time of protocol enrollment. Neither is listed if the patient’s lymphoma was neither chemorefractory nor relapsed after ASCT. Double hit lymphoma refers to bcl-2 and c-myc translocation by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH); triple hit lymphoma had bcl-2, c-myc, and bcl-6 translocation by FISH.

Lymphoma responses were assessed according to Cheson et al. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2007; 25(5): 579–586 (Reference 38). Response duration is the time from first documentation of response, which was one month after cell infusion in all patients, until progression, initiation of off-study treatment, or last documentation of ongoing response. (+) Indicates an ongoing response. All second and third treatments included both chemotherapy and CAR T cells.

Cytokine-release syndrome (CRS) toxicity grading is per Lee et al. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2019; 25: 625–638 (Reference 39). The maximum grade of CRS experienced is listed.

All neurologic adverse events except syncope but including headaches and all other adverse events listed in the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Averse Events Version 3.0. were included in this summary. The maximum grade of neurologic toxicity experienced by each patient is listed. Syncope was not counted as neurologic toxicity because it was related to CRS-related hypotension. <Grade 2 means either Grade 1 or Grade 0 neurologic adverse events. Our trial did not record Grade 1 adverse events. ^Patient 4 had continuous SD from the time of his first CAR T-cell infusion until going off-study to pursue other therapy.

Hu19-CD828Z was detected on the T-cell surface with a CAR-specific monoclonal antibody (Figure 1c)35. For the 20 treated patients, the median %CAR+ cells among the infusion CD3+ cells was 56.3% (range 21.7–72.4%). The CD4:CD8 ratio of the infusion CAR+ T cells was 1.2 (range 0.3–3.6). We assessed markers of memory and senescence on infusion Hu19-CD828Z CAR+ T cells by flow cytometry, and we assessed the same markers on CAR+ T cells from the blood of patients at the time of peak blood CAR+ cell levels 7 to 15 days after CAR T-cell infusion (Supplementary Figures 1–2). CAR+ T cells obtained a more differentiated phenotype after infusion in agreement with prior results36,37.

Patient characteristics and outcomes

All 20 patients treated on this trial had B-cell lymphoma with a median of 4 (range 1–9) prior lines of lymphoma therapy before protocol enrollment (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1, Extended Data 1). Eight of 20 patients had chemotherapy-refractory lymphoma at the time of protocol enrollment. In an additional 3 patients, the last line of therapy prior to protocol enrollment was autologous stem-cell transplantation with lymphoma relapse 9 months or less after transplantation (Table 1). Five of 20 patients had poor-prognosis double or triple hit lymphoma.

For initial treatments, the overall remission rate of complete remissions (CR) plus partial remissions (PR) was 70% as assessed by standard criteria38. The CR rate was 55%. Eight of 20 patients (40%) were in ongoing CRs at the time of last follow-up. Ongoing CRs have durations of response ranging from 17 to 35 months (Figure 1d). Median event-free survival for all patients was 6 months (Figure 1e). Sizable lymphoma burdens were eliminated as shown by positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scans (Figure 1f–h). Four patients received more than 1 conditioning chemotherapy plus CAR T-cell treatment; cell doses and outcomes are in Table 1.

Toxicity of Hu19-CD828Z T cells

We graded CRS with a standard scale39. Grade 3 and 4 adverse events are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Neurologic toxicity after Hu19-CD828Z T-cell infusions was rare and, except for 1 case, mild. Patient 3 had Grade 4 neurologic toxicity that resolved less than 24 hours after starting treatment with dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 hours. No patient had Grade 3 as the maximum grade of neurologic toxicity. Three patients had a maximum grade of Grade 2 neurologic toxicity. At the peak of neurologic toxicity, Patient 3 had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings similar those previously reported on other trials5,23,24. Patient 3’s CSF protein was elevated at 116 mg/dL. Patient 3’s CSF white blood count was elevated at 165/μL; 78% of WBC were lymphocytes. Seventy-two percent of the CSF mononuclear cells were CAR+ by quantitative PCR analysis. Two patients received immunosuppressive drugs for CRS. Patient 4 received tocilizumab. Patient 8 received both tocilizumab and corticosteroids. CRS and neurologic toxicity completely resolved in all patients. No patients died of protocol-related toxicity. Because of prior therapies, only 5 patients had blood B-cell levels of 5/μL or higher immediately before study treatment; all 5 patients had depletion of B cells to 0/μL after CAR T-cell infusion. Of 8 patients with long-term remissions of lymphoma ranging from 17 to 35 months, 2 had blood B-cell count recovery to normal levels; both patients remain in remission.

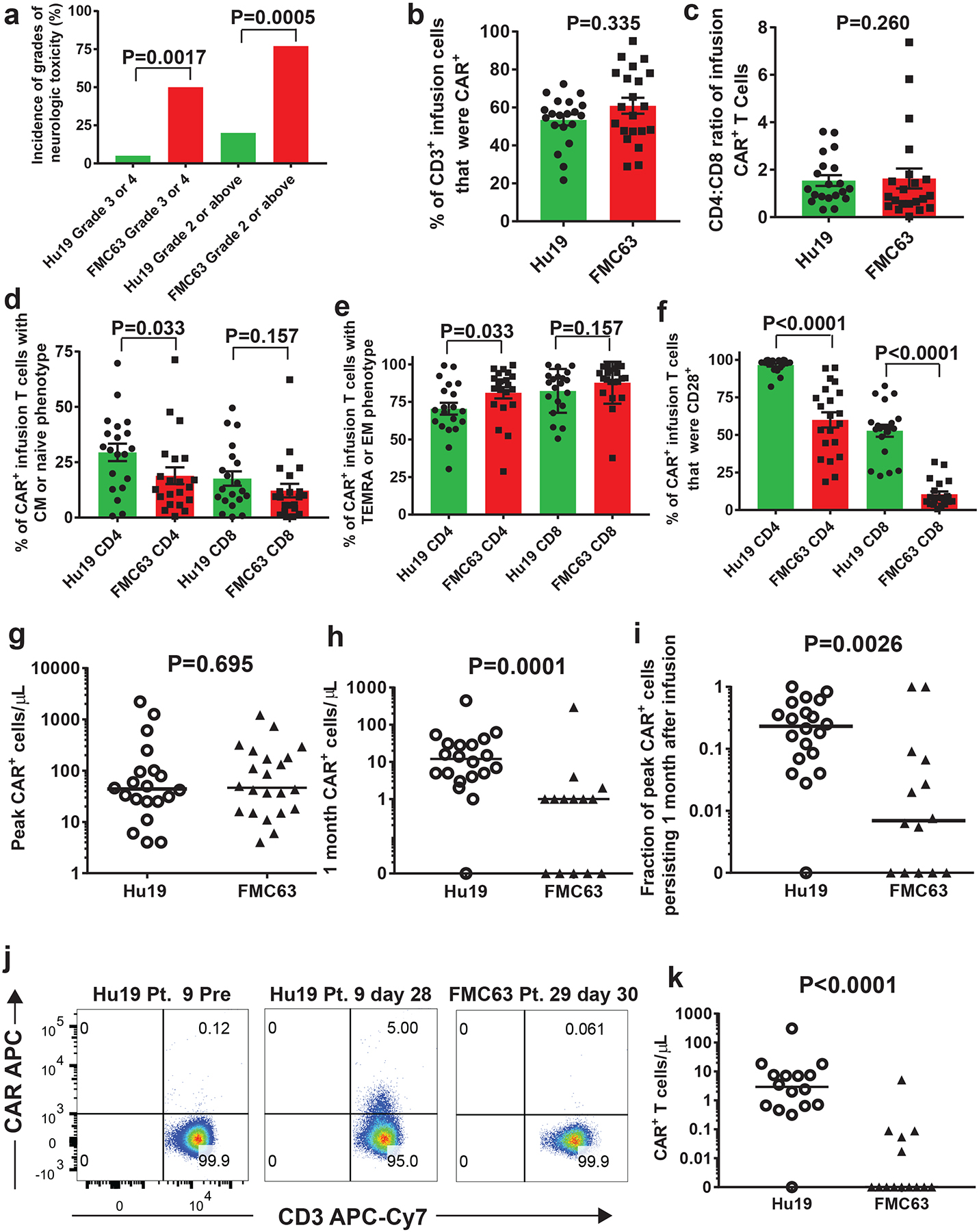

Hu19-CD828Z T cells were associated with less neurologic toxicity than FMC63–28Z T cells

The incidence of neurologic toxicity after infusion of Hu19-CD828Z T cells was significantly less than the incidence of neurologic toxicity on a previous clinical trial that tested FMC63–28Z CAR T cells at our center. Neurologic toxicity was graded by a standard system (Figure 2a)40. The rate of Grade 3 or 4 (severe) neurologic toxicity was only 5% (1/20) with Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus 50% (11/22) with FMC63–28Z T cells (P=0.0017, Fisher’s exact test, Figure 2a). The rate of Grade 2 or above neurologic toxicity was 20% (4/20) with Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus 77% (17/22) with FMC63–28Z T cells (P=0.0005, Fisher’s exact test). All Grade 2–4 neurologic events for the Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z clinical trials are listed in Extended Data 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 2. CAR T-cell characteristics and persistence.

(a) Percentages of patients receiving either Hu19-CD828Z (Hu19) T cells or FMC63–28Z (FMC63) T cells experiencing different grades of neurologic toxicity; P values by 2-sided Fisher’s exact test. All 20 patients that received Hu19 T cells and all 22 patients that received FMC63 T cells are included. (b-f) Flow cytometry with anti-CAR antibody, anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8 and other markers was performed on infusion cells from patients receiving Hu19 or FMC63 T cells. Results for c-f are from CD3+CAR+ cells. (b) %CAR+CD3+. (c) CD4:CD8 ratio. (d) %Central memory (CM, CCR7+CD45RA-negative) plus %naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+). (e) %Effector memory (EM, CCR7-negative, CD45RA-negative) plus %T-effector memory RA (TEMRA, CCR7-negative, CD45RA+). (f) %CD28+; b-f, colored bars represent means; error bars show +/−SEM; comparisons by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. For b-f n=20 unique patients for Hu19 and n=21 unique patients for FMC63. (g) CAR+ PBMC were quantified by qPCR at multiple time-points post-infusion. Peak CAR+ cell levels are shown for all 20 Hu19 patients and all 22 FMC63 patients. (h) CAR+ cells were quantified by qPCR 1-month (26–35 days for all of Figure 2) after CAR T-cell infusion. (i) For each patient, CAR+ cell number determined by qPCR 1-month post-infusion divided by the peak CAR+ cell number was the fraction of peak CAR+ cells persisting 1-month post-infusion. For h and i, all 20 Hu19 patients were included, and all 14 FMC63 patients with available 1-month post-infusion PBMC were included. (j) Blood CAR+ T cells were assessed by anti-CAR antibody flow cytometry. Plots are gated on live CD3+ lymphocytes. (k) Flow cytometry as in j was performed for patients with available samples 1-month post-infusion. For j and k (Hu19 n=16 and FMC63 n=14 unique patients) In g-i and k, horizontal bars represent medians, and comparisons were by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

The designs of the clinical trials testing Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z were very similar. Patients on both trials received 3 doses of cyclophosphamide as part of the chemotherapy conditioning regimen. On the Hu19-CD828Z trial, all patients received 300 mg/m2 doses of cyclophosphamide, On the FMC63–28Z trial, 18 of 22 patients received 300 mg/m2 doses of cyclophosphamide, and 4 patients received 500 mg/m2 doses of cyclophosphamide. Patients on both trials received 3 doses of 30 mg/m2 of fludarabine as part of their conditioning regimens.

The cell culture methods used to produce CAR T cells for both the Hu19-CD828Z trial and the FMC63–28Z trial were similar. Whole PBMC were stimulated with an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody and cultured for 6–10 days on both trials. The mean CAR+ T-cell dose on the Hu19-CD828Z trial was 3.2×106/kg; the mean CAR+ T-cell dose was 1.9×106/kg on the FMC63–28Z trial.

DLBCL, follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma were treated on both trials. One patient with Burkitt lymphoma was treated on the Hu19-CD828Z trial. The percentages of chemotherapy-refractory lymphoma were 40% for the Hu19-CD828Z trial and 50% for the FMC63–28Z trial. Two patients received tocilizumab on each of the Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z trials. Two Hu19-CD828Z patients and 1 FMC63–28Z patient received corticosteroids. Characteristics of both trials are summarized in Supplementary Table 3.

Cell-surface phenotype of Hu19-CD828Z versus FMC63–28Z infusion T cells

We conducted investigations to determine possible mechanisms for the lower incidence of neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z versus FMC63–28Z. For flow cytometry, we used an anti-CAR monoclonal antibody that binds equivalently to the scFv linkers of Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z (Supplementary Figure 3). We compared CAR expression and CD4 to CD8 ratio of CAR+ clinical infusion T cells and found no significant difference between Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells and FMC63–28Z CAR T cells (Figure 2b–c). T cells can be divided into 4 different phenotypes by expression of C-C-chemokine receptor type 7 (CCR7) and CD45RA41. Naïve and central memory (CM) T cells have more proliferative capacity and are less differentiated than effector memory (EM) and T-effector memory RA (TEMRA) T cells41. We found a slightly higher percentage CD4+ CAR+ T cells with a naïve or CM phenotype among Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells, and we found a correspondingly lower percentage of CD4+ CAR+ T cells with an EM or TEMRA phenotype among Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 2d–e). Of the markers assessed, CD28 differed the most between Hu19-CD828Z infusion T cells and FMC63–28Z infusion T cells (Figure 2f). The percentages of infusion T cells with killer-cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G member-1+, or CD45RO-negative-CD27+, or programmed death molecule-1+ phenotypes are shown in Supplementary Figure 4.

Peak CAR T-cell levels and CAR T-cell persistence

There was not a statistically-significant difference in peak CAR+ cell levels after infusion for Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells versus FMC63–28Z CAR T cells when CAR+ cells were measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Figure 2g). In contrast, there was a statistically-higher level of persisting CAR+ cells 1 month after infusion in patients who received Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells versus patients who received FMC63–28Z T cells when measured by qPCR (Figure 2h). We calculated the fraction of the peak CAR+ cell number that persisted 1 month after infusion in each patient. Statistically higher fractions of peak CAR+ cell levels persisted 1 month after infusion for Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 2i). We confirmed the qPCR results by performing flow cytometry on blood cells from 1 month after CAR T-cell infusion with anti-CD3 and the anti-CAR antibody that recognized Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z equivalently35. Representative flow cytometry results are shown from pretreatment and day 28 post-infusion time points of Patient 9 who received Hu19-CD828Z T cells (Figure 2j). Results are also shown from Patient 29 who received FMC63–28Z T cells. The low median fluorescence intensity of the CAR+ cell staining (Figure 2j, middle panel) was representative of most patients with persisting CAR+ T cells. Higher levels of Hu19-CD828Z T cells than FMC63–28Z T cells were detected in the blood of patients 1 month after infusion by flow cytometry (Figure 2k).

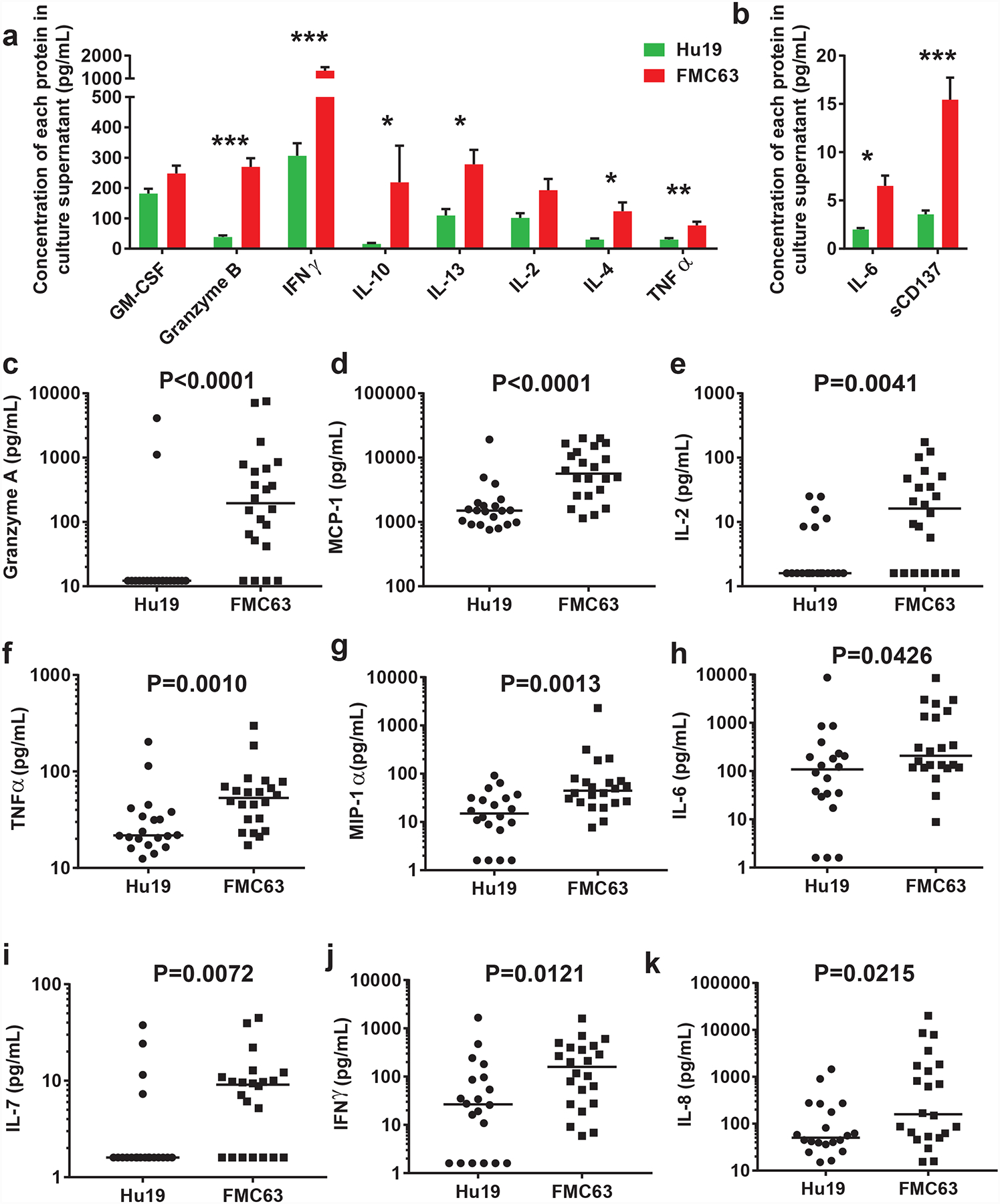

Function of infusion CAR T cells

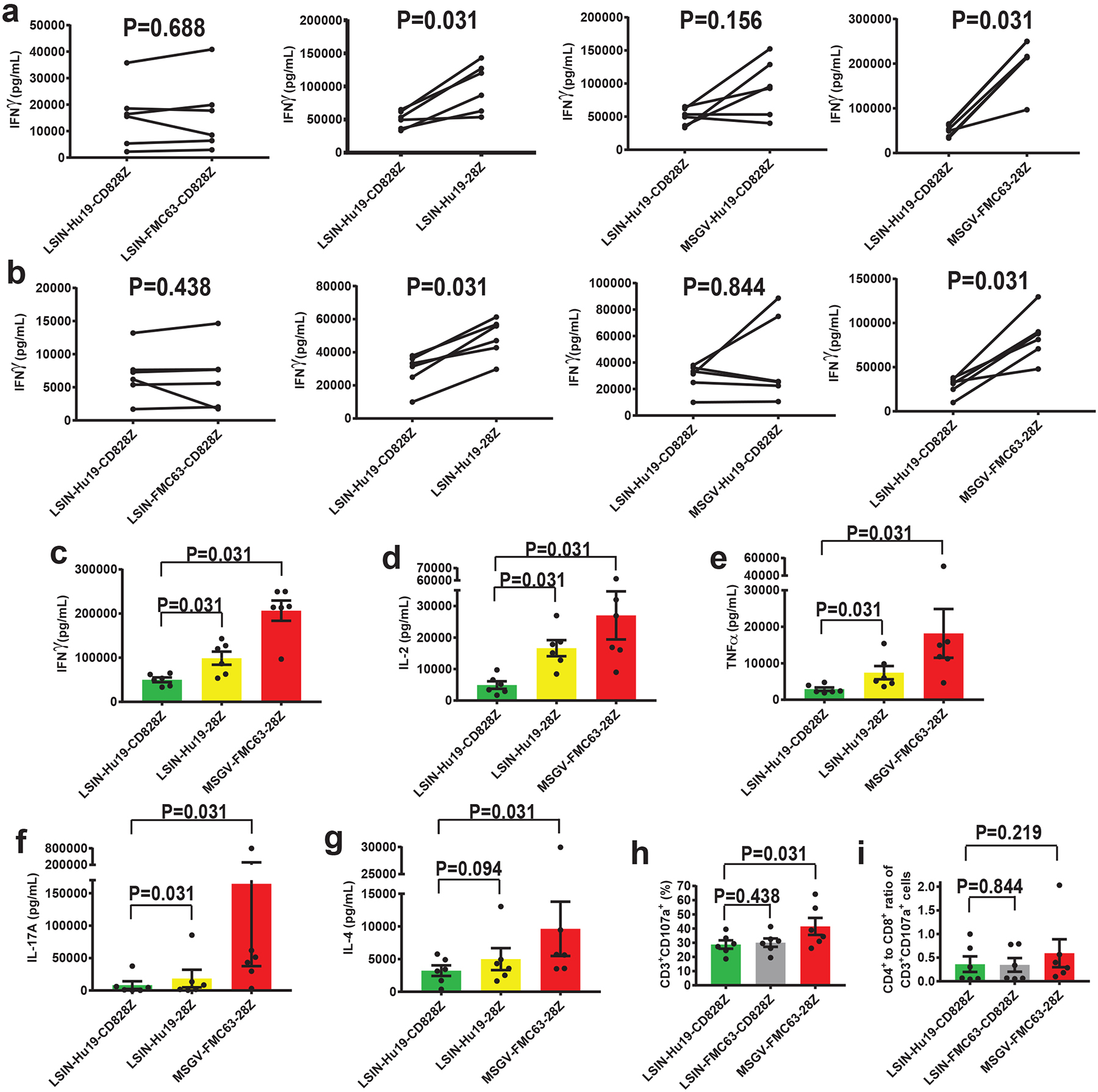

Lower levels of several immunological proteins were released in vitro by Hu19-CD828Z clinical infusion T cells compared with FMC63–28Z infusion T cells (Figure 3a–b). Values in Figure 3a–b are normalized for CAR expression; non-normalized values are in Supplementary Figure 5.

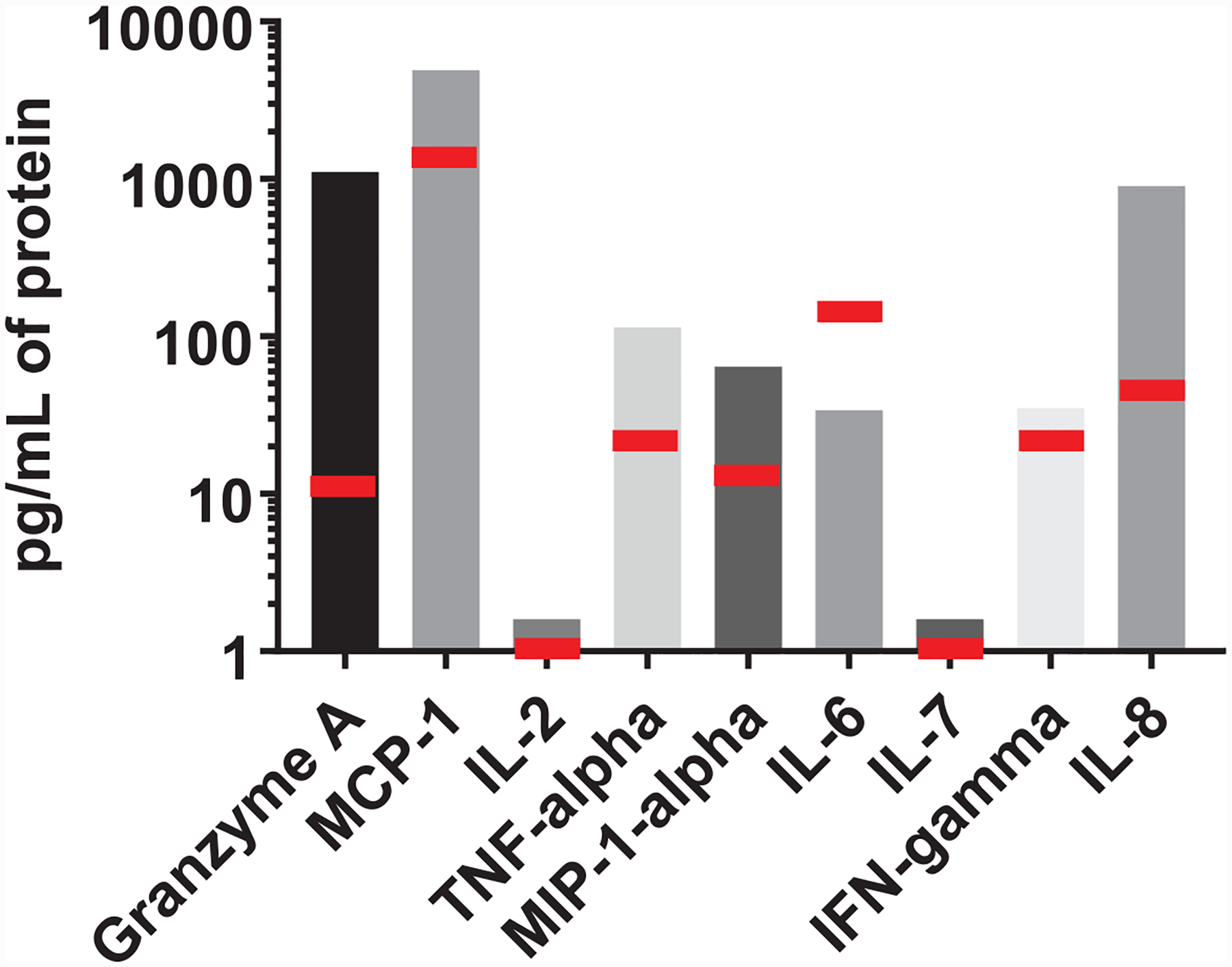

Figure 3. Cytokine production by infusion CAR T cells and blood cytokine levels.

(a and b) T cells expressing Hu19-CD828Z released lower levels of immunological proteins compared with T cells expressing FMC63–28Z. Samples of the infusion CAR T cells from patients treated with either Hu19-CD828Z (Hu19) T cells or FMC63–28Z (FMC63) T cells were cultured overnight with CD19-K562 cells. Supernatant was collected and tested in Luminex® assays. Background release of each protein after overnight culture of CAR T cells with CD19-negative NGFR-K562 cells was subtracted from the protein release when CAR T cells were cultured with CD19-K562 cells. Cytokine values are normalized for CAR expression level by dividing the cytokine value by the %CAR+ T cells for each patient. Bars show mean+SEM. P<0.0001 is indicated by ***; P<0.001 is indicated by **; P≤0.01 is indicated by *; comparisons with no asterisk above the bars had P>0.05. N=18 unique patients for Hu19 and n=21 unique patients for FMC63. (c-k) Serum was collected at multiple time-points between day 2 and day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion and analyzed for immunologically-important proteins by Luminex® assay; all 20 Hu19 patients and all 22 FMC63 patients were compared. The peak protein levels for each patient are shown with horizontal bars representing the median. (c) Granzyme A, (d) MCP-1, (e) IL-2, (f) TNFα, (g) MIP-1α, (h) IL-6, (i) IL-7, (j) IFNγ, (k) IL-8. For all of Figure 3, statistical comparisons were by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney tests.

Serum levels of immunological proteins were lower in patients receiving Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells

We evaluated the levels of immunological proteins in the blood of patients at multiple time-points from day 2 to day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. The peak serum levels of several immunological proteins, including granzyme A, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin (IL)-2, tumor necrosis factorα (TNFα), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, and interferonγ (IFNγ) were lower in the blood of patients receiving Hu19-CD828Z T cells compared with patients receiving FMC63–28Z T cells. The most prominently different peak protein levels are shown in Figure 3c–k; the median peak levels of all tested proteins are in Extended Data 4. Patient 3, the only patient on the Hu19-CD828Z trial with severe neurologic toxicity, had high peak levels of some of the immunologic proteins included in Figure 3 (Extended Data 5). We also assessed cytokine areas under the curves from day 2 to day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion and found that levels of many immunological proteins, including Granzyme A, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and IL-2, were lower in patients receiving Hu19-CD828Z versus FMC63–28Z T cells (Extended Data 6).

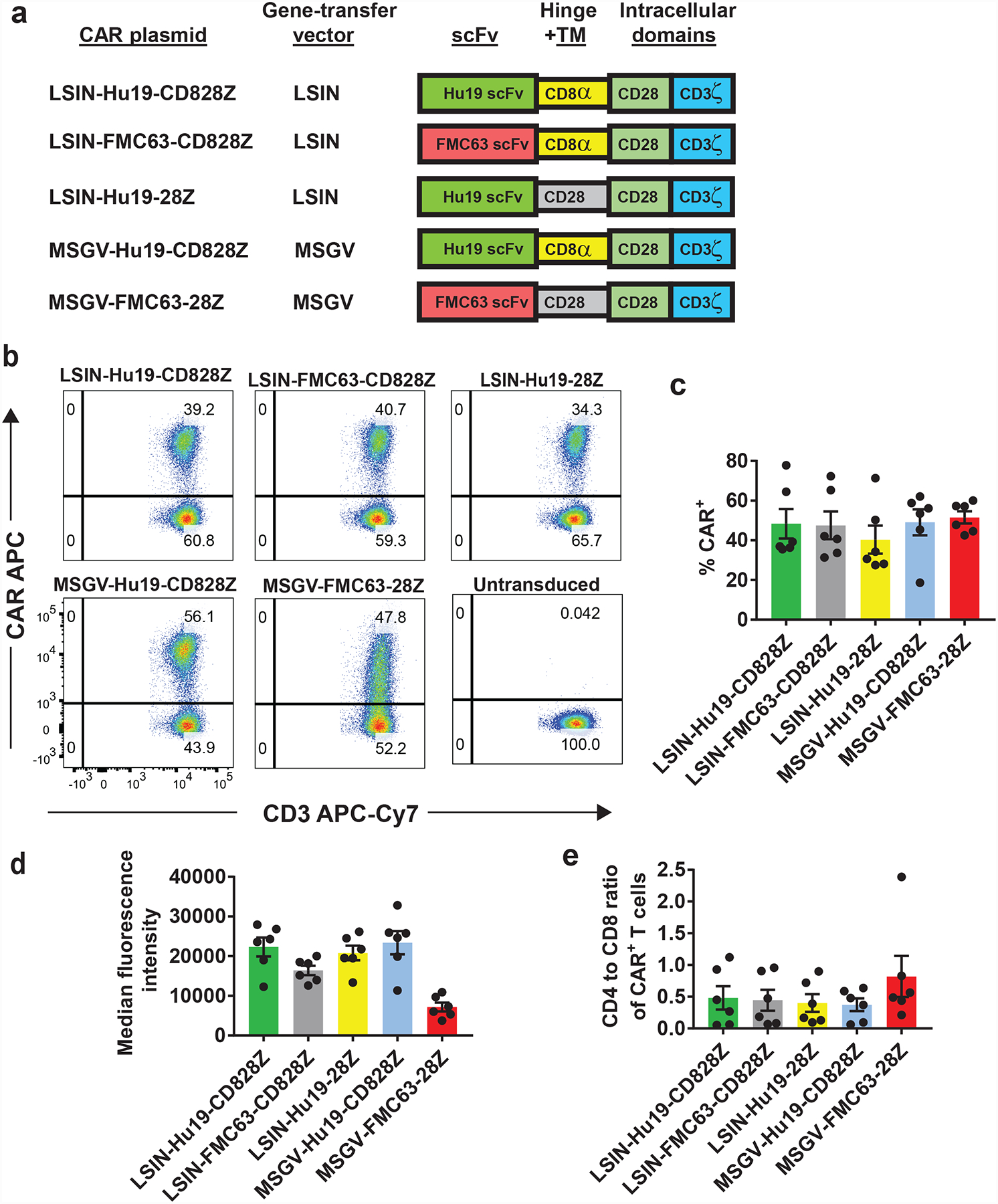

Comparison of different CAR design components and gene-transfer vectors

LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z differed from MSGV-FMC63–28Z in the scFv, hinge plus transmembrane domains, and gene-transfer vector. To investigate why cytokine release by LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z T cells was lower than cytokine release by MSGV-FMC63–28Z T cells, we constructed a series of CAR-encoding plasmids that each differed from LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z by one of the 3 components that were different between LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z and MSGV-FMC63–28Z (Figure 4a). LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z was identical to LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z except for replacement of the Hu19 scFv in LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z by the FMC63 scFv in LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z. LSIN-Hu19–28Z differed from LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z only in the hinge plus transmembrane domains. LSIN-Hu19–28Z had hinge plus transmembrane domains from CD28; LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z had hinge plus transmembrane domains from CD8α. MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z was identical to LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z except for the different gene-transfer vectors.

Figure 4. Comparison of CAR designs.

(a) Five CAR plasmids are listed. LSIN, lentiviral vector; MSGV, gamma-retroviral vector. All 5 CARs contained a CD28 costimulatory domain and a CD3ζ domain. LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z had the Hu19 human scFv plus CD8α hinge and transmembrane (TM) domains. LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z had the FMC63 scFv plus CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains. LSIN-Hu19–28Z had the Hu19 scFv plus CD28 hinge and transmembrane domains. MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z had the Hu19 scFv plus CD8α hinge and transmembrane domains; MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z was identical to LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z except for the gene-therapy vectors. MSGV-FMC63–28Z had the murine FMC63 scFv plus CD28 hinge and transmembrane domains. (b) T cells from the same patient were transduced with each of 5 CARs or left untransduced as indicated. Plots are gated on live, CD3+ lymphocytes. These results are representative of results from 6 unique donors. (c) The %CAR+ T cells for each of the 5 CARs is shown. Flow cytometry gating was as in b. LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z was compared to the other 4 CARs. The only consistent difference was between LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z and LSIN-Hu19–28Z (P=0.031). LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z was compared to the other 3 CARs; P values for the comparisons were: LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, 0.6875; MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z, >0.999; MSGV-FMC63–28Z, 0.5625. (d) The median fluorescence intensities of only the CAR+ T cells are shown. When LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z was compared to the other 4 CARs, the only consistent difference was between LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z and MSGV-FMC63–28Z (P=0.031). LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z was compared to the other 3 CARs; P values for the comparisons were: LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, 0.063; LSIN-Hu19–28Z, 0.4375; MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z, >0.999. (e) A CD4+ versus CD8+ plot gated on CD3+CAR+ events was used to determine the CD4 to CD8 ratio of CAR+ T cells. LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z was compared to the other 4 CARs; P values for the comparisons were: LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, 0.438; LSIN-Hu19–28Z, 0.438; MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z, 0.563; MSGV-FMC63–28Z, 0.094. For c-e, comparisons were by 2-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Graphs c-e show mean +/−SEM. For c-e, n=6 independent experiments with cells from unique donors.

When T cells were transduced with each of the 5 CARs used in these comparisons, the percentages of CAR-expressing T cells were not different except for a modestly lower level of expression for LSIN-Hu19–28Z compared with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z (Figure 4b–c). Median fluorescence intensity of CAR+ T cells was lower for MSGV-FMC63–28Z than for LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z (Figure 4d). There was not a consistent difference in CD4 to CD8 ratio of CAR+ T cells when any of the other CARs were compared with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z (Figure 4e).

Next, we conducted in vitro IFNγ release assays with the CARs that each differed by 1 component from LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z. T cells transduced with the different CARs were cultured overnight with target cells, and IFNγ was measured in the culture supernatant (Figure 5a–b). T cells were tested for recognition of 2 different CD19+ target cell lines to control for target cell-specific factors. There was no consistent difference in IFNγ release when T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z and T cells transduced with LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z were compared (P=0.688). IFNγ release was consistently lower by T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19–28Z (P=0.031). There was not a consistent difference in IFNγ release for T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus T cells transduced with MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z (P=0.156). As expected, IFNγ release was consistently lower for T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus T cells transduced with MSGV-FMC63–28Z (P=0.031). In summary, IFNγ release experiments comparing CARs that differred from LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z by only one component showed that using hinge and transmembrane domains from CD8α versus CD28 was associated with lower levels of IFNγ release. The other 2 components by which LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z differed from MSGV-FMC63–28Z were not associated with a consistent change in IFNγ production.

Figure 5. Functional comparison of CARs.

(a) T cells were transduced with either LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z, LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, LSIN-Hu19–28Z, MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z, or MSGV-FMC63–28Z and cultured overnight with CD19+ CD19-K562 cells or CD19-negative NGFR-K562 cells. IFNγ was measured in the culture supernatant. (b) The same T cells from a were tested for IFNγ release when cultured with CD19+ NALM6 cells. For a and b, lines connect paired results with T cells from the same donor, and P values for each comparison are shown. (c-g) T cells from the same donors as in a were transduced with either LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z, Hu19–28Z, or MSGV-FMC63–28Z and cultured overnight with CD19-K562 or NGFR-K562. Cytokines were measured in culture supernatants (c) IFNγ, (d) IL-2, (e) TNFα, (f) IL-17A, (g) IL-4. For a-g, CD19-specific cytokine release is cytokine release by CAR T cells cultured with CD19-K562 or NALM6 minus cytokine release by CAR T cells cultured with NGFR-K562. (h) Degranulation was assessed by flow cytometry for CD107a. CD19-specific degranulation was %CD3+CD107+ cells with NALM6 stimulation minus %CD3+CD107+ cells with NGFR-K562 stimulation. For c-i, P values are shown above the brackets connecting results from different CARs. (i) There was no consistent difference in CD4+ to CD8+ ratios of CD3+CD107+ cells in h. For all of Figure 5, the percentage of T cells expressing different CARs was equalized prior to experiments by adding untransduced T cells as needed. For all of Figure 5, comparisons were made by 2-tailed Wilcoxon matched-paired signed-rank tests. Bar graphs show mean +/−SEM; n=6 different donors in all comparisons.

Compared with T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z, T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19–28Z released more IFNγ, which demonstrated that IFNγ release was higher with CD28 versus CD8α hinge plus transmembrane domains. However, the magnitude of the difference in IFNγ release between T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus MSGV-FMC63–28Z was higher than the magnitude of the difference in IFNγ release between T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus LSIN-Hu19–28Z (Figure 5c); therefore, the lower level of cytokine release by LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z T cells compared with MSGV-FMC63–28Z T cells was not completely explained by the difference in hinge plus transmembrane domains between these two CARs. Compared with T cells expressing LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z, release of multiple cytokines was higher by T cells expressing LSIN-Hu19–28Z; in addition, cytokine release was higher by T cells expressing MSGV-FMC63–28Z versus T cells expressing LSIN-Hu19–28Z (Figure 5c–g).

We found no difference in degranulation by T cells transduced with either LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z or LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, CARs differing only in scFv. (Figure 5h–i). We found statistically lower levels of CD19-specific degranulation by T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z versus MSGV-FMC63–28Z (Figure 5h–i).

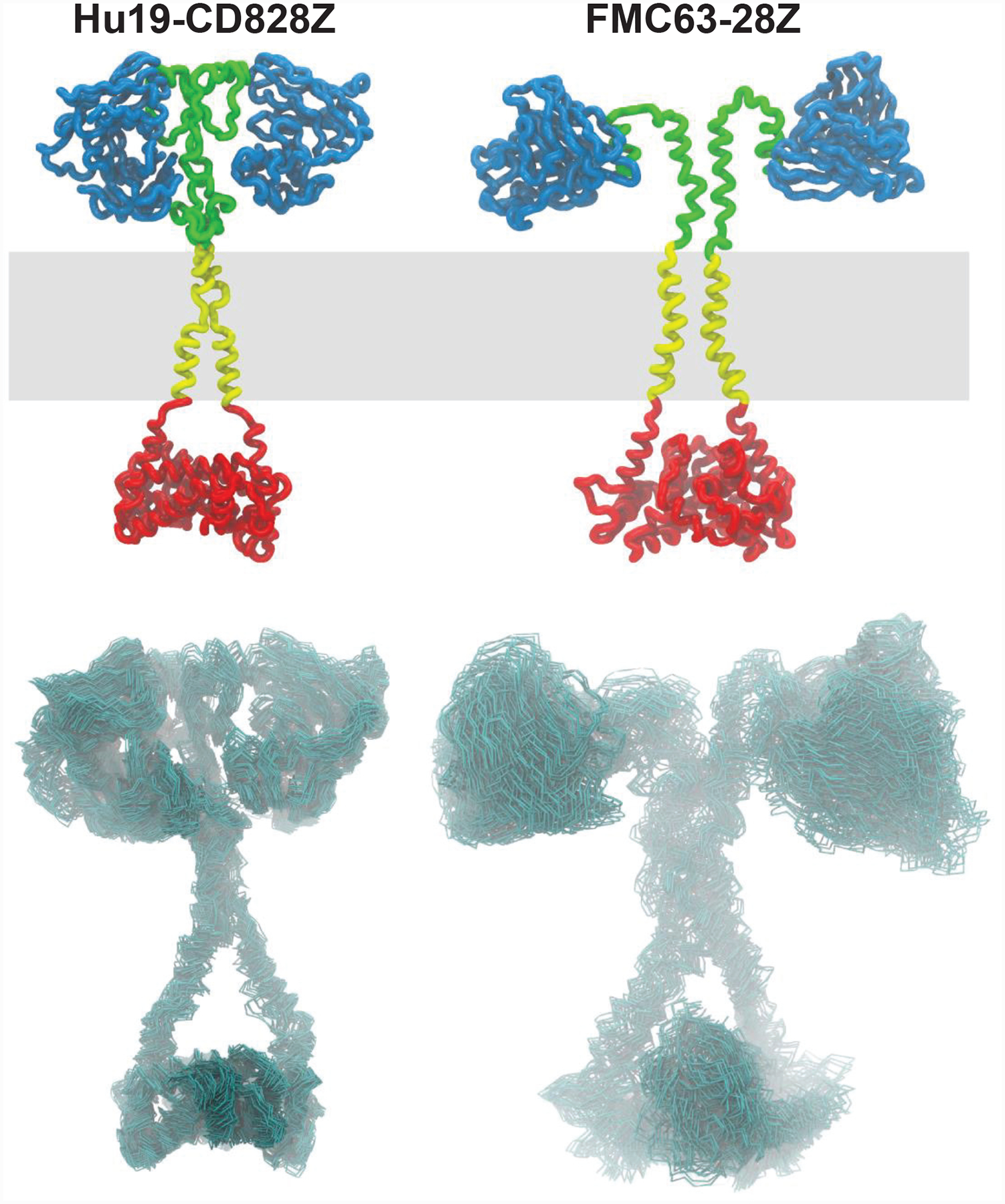

We conducted structural modeling to generate hypotheses about why Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z were functionally different. The dominant structural difference predicted by the modeling was that the conformational flexibility of the extracellular portion of Hu19-CD828Z was lower than that of FMC63–28Z (Extended Data 7).

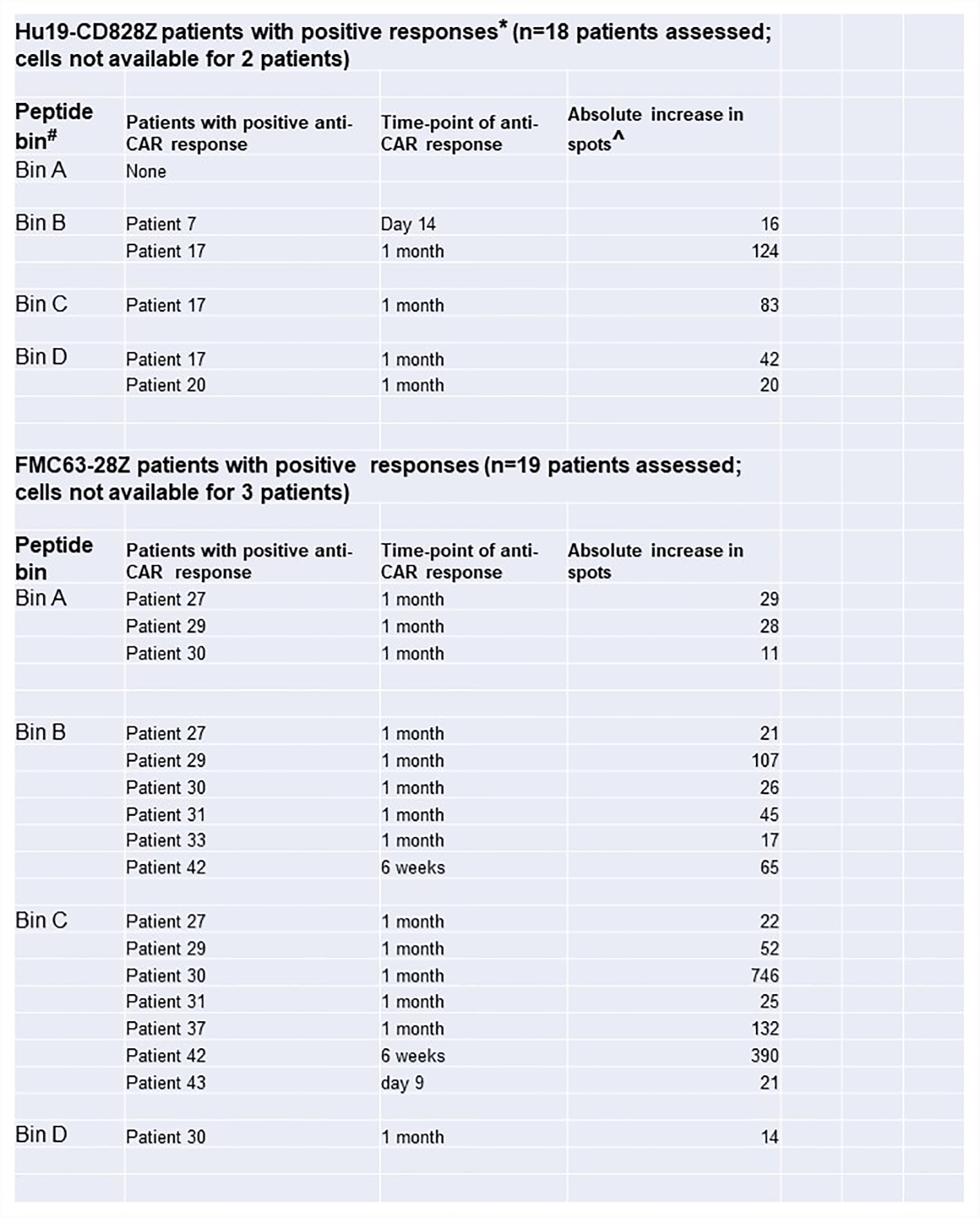

Assessment for recipient anti-CAR immune responses

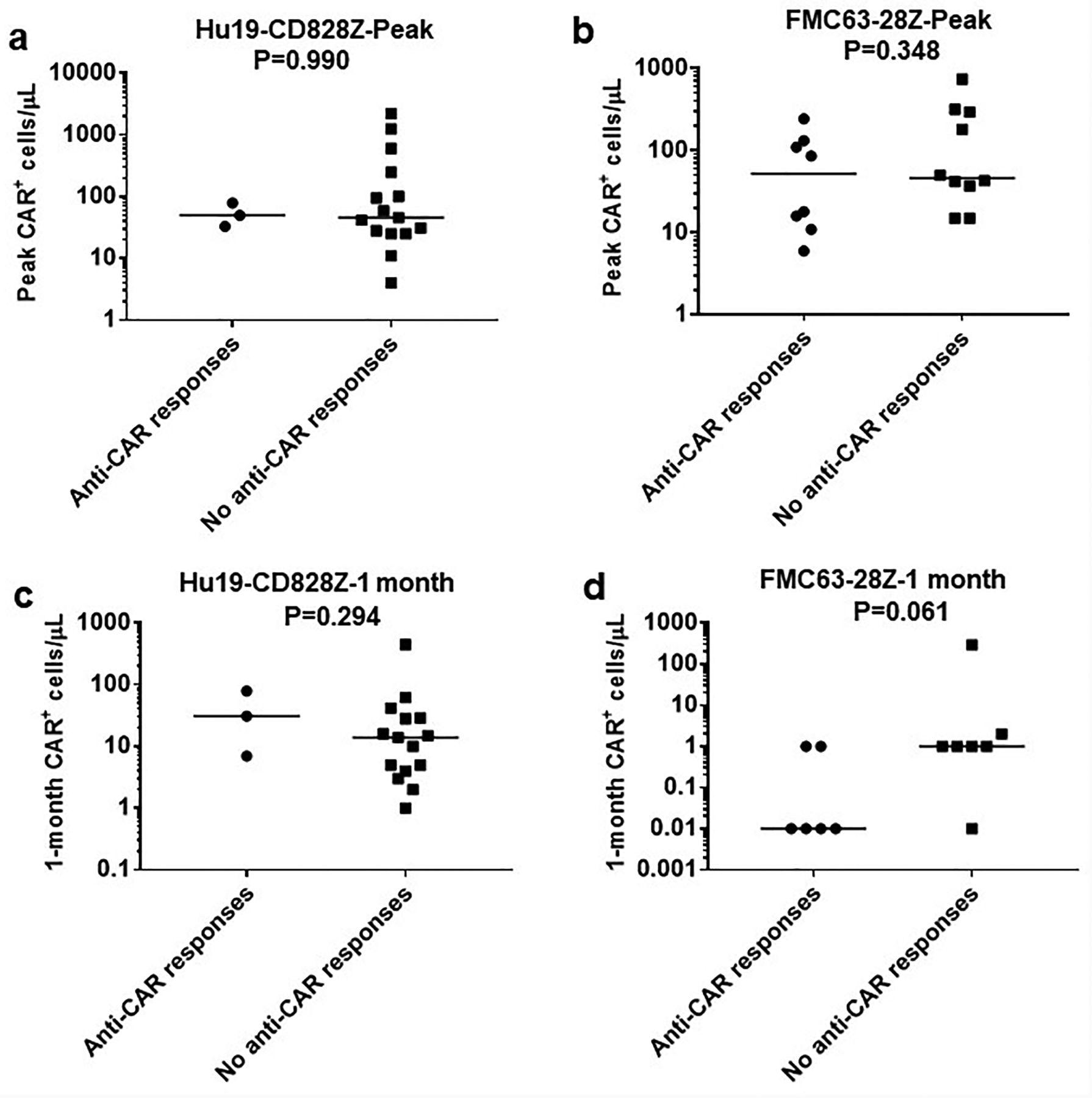

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays42 were conducted on patient PBMC before and after CAR T-cell treatments to assess for recipient T-cell responses against infused CAR T cells. Anti-CAR T-cell responses were detected after CAR T-cell infusion in 3 patients on the Hu19-CD828Z trial and 8 patients on the FMC63–28Z trial (Extended Data 8, Supplementary Table 7). We also assessed blood CAR+ T-cell levels in patients on the Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z clinical trials. We did not find a difference in either peak blood CAR+ cell levels or 1-month CAR+ cell levels in patients with or without anti-CAR T-cell responses (Extended Data 9). For patients on the FMC63–28Z clinical trial, there was a not statistically-significant trend toward higher blood CAR+ cell levels one month after CAR T-cell infusion for patients without anti-CAR T-cell responses versus patients with anti-CAR T-cell responses (P=0.061).

Discussion

In our previous clinical trial with FMC63–28Z CAR T cells, neurologic toxicity was a more substantial clinical problem than CRS5. In the previous NCI clinical trial of FMC63–28Z T cells, 4 of 22 patients had Grade 3 or 4 CRS (Supplementary Table 4) while 11 of 22 patients had Grade 3 or 4 neurologic toxicity. In the Hu19-CD828Z trial, 2 patients had Grade 3 or 4 CRS (Table 1); both had high lymphoma burdens (Figure 1g and Supplementary Figure 6).

Compared with FMC63–28Z-expressing T cells, Hu19-CD828Z-expressing T cells released lower levels of cytokines, and patients who received Hu19-CD828Z T cells had lower serum levels of many immunological proteins compared with patients who received FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 3c–k). We conclude that a likely reason for the lower incidence of neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells is release of lower levels cytokines and other potentially neurotoxic substances by Hu19-CD828Z T cells. Although a causative mechanistic explanation is not provided by this report, most authors consider elevated serum cytokines an important factor in CAR T-cell neurologic toxicity23,24.

Because only 1 patient in the current Hu19-CD828Z trial had Grade 3 or 4 neurologic toxicity, we were not able to assess for associations between serum immunological protein levels and severe neurotoxicity. In our previous trial of FMC63–28Z T cells, the serum proteins most closely associated with Grade 3 or 4 neurologic toxicity were Granzyme A and B, IL-10, IL-15, interferon-inducible protein-10, and IFNγ5. Many of these proteins associated with neurotoxicity in our previous trial5 were lower in the serum of patients receiving Hu19-CD828Z T cells compared with patients receiving FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 3c–k, Extended Data 4 and 6).

We found equivalent peak blood CAR+ cell levels with Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z (Figure 2g). One-month after the day of infusion, blood levels of Hu19-CD828Z T cells were higher than blood levels of FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 2h–k). These findings demonstrate that the lower level of neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells was not due to lower levels of blood Hu19-CD828Z T cells compared with FMC63–28Z T cells.

Some phenotypic markers, including CCR7, CD45RA, and CD28 indicated that the infusion Hu19-CD828Z T cells were slightly less differentiated than infusion FMC63–28Z T cells (Figure 2d–f), but other markers indicated a more differentiated or activated phenotype for Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus FMC63–28Z T cells (Supplementary Figure 4).

Our results did not demonstrate that recipient T-cell responses against CARs were a critical factor in CAR+ cell blood levels (Extended Data 9); however, the number of patients assessed was small, so firm conclusions on the importance of CAR immunogenicity cannot be reached.

Despite the lower level of neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z, clinical anti-lymphoma activity was equivalent with Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z. Incidence of Grade 3–4 neurologic toxicity was 28% in a large multicenter clinical trial of FMC63–28Z-expressing T cells (axicabtagene ciloleucel)7. Although the number of patients treated with Hu19-CD828Z was small, the incidence of neurologic toxicity with this CAR compares favorably with the rates of neurologic toxicity on other anti-CD19 CAR trials1,6–8,23,43. The anti-CD19 CAR Juno(J)CAR015 was associated with substantial neurologic toxicity including 5 deaths from cerebral edema13,19,43. Interestingly, the 19–28z CAR in JCAR015 contained CD28 hinge and transmembrane domains44. Our results with Hu19-CD828Z show that CARs targeting CD19 are not intrinsically linked to high levels of neurologic toxicity and that inclusion of CD28 domains in CARs is not intrinsically linked to high levels of toxicity, especially neurologic toxicity.

This work demonstrates that CAR design affects CAR T-cell function in a clinically-significant manner. The difference in function between Hu19-CD828Z T cells and FMC63–28Z T cells was in part due to the difference in hinge plus transmembrane domains as shown by our prior work28 and the lower levels of CD19-specific cytokine-release by Hu19-CD828Z T cells versus Hu19–28Z T cells (Figure 5a–g). The difference in cytokine release between Hu19-CD828Z T cells and FMC63–28Z T cells was not completely explained by the difference in hinge and transmembrane domains between these CARs because the difference in cytokine release between T cells expressing Hu19-CD828Z and T cells expressing FMC63–28Z was larger than the difference in cytokine release between T cells expressing Hu19-CD828Z and T cells expressing Hu19–28Z (Figure 5c–g) despite inclusion of CD28 hinge plus transmembrane domains in both Hu19–28Z and FMC63–28Z. There was no consistent difference in IFNγ release by T cells expressing Hu19-CD828Z versus FMC63-CD828Z, a CAR that differed from Hu19-CD828Z only in the scFv (Figure 5a–b), so the choice of scFv in isolation, was not the explanation for the difference in cytokine release by Hu19-CD828Z versus FMC63–28Z T cells. We hypothesize that structural characteristics of Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z including the hinge plus transmembrane domains and possibly interactions of the hinge plus transmembrane domains with scFvs or the cytoplasmic CD28 domain caused the large magnitude of difference in cytokine release between Hu19-CD828Z T cells and FMC63–28Z T cells. Further work to more definitively determine the structural differences between Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z is underway.

These findings demonstrate that CARs can be designed to minimize toxicity while retaining anti-malignancy activity. Our results agree with recent work by Ying et al. relating CAR design to toxicity45. Our work differs from this prior work in several critical aspects. First, our work provides a comparison of clinical and immunologic results of two CARs tested at the same institution, so many confounding factors that arise in comparing different trials were minimized. Second, our work focuses on a comparison of CARs with hinge plus transmembrane domains from CD8α versus CD28; in contrast, the focus of Ying et al. was on the length of hinge and transmembrane domains. Third, our work focused on neurologic toxicity and demonstrated that a novel CAR, Hu19-CD828Z, was associated with less neurologic toxicity than FMC63–28Z, the CAR used in the U.S. Food and Drug administration-approved product axicabtagene ciloleucel. Fourth, our work showed that clinically-effective CARs containing CD28 costimulatory domains are not always associated with high levels of toxicity; in contrast, Ying et al. focused exclusively on CARs containing 4–1BB costimulatory domains.

Our group and others have reported that inactivating CD3ζ immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) caused improvement of CAR T-cell survival and anti-tumor efficacy in mice; these ITAM studies showed another approach for a potentially beneficial reduction in CAR T-cell activation strength32,46. Reducing scFv affinity is another potential way to reduce CAR T-cell toxicity47.

Future CAR T-cell therapies can be improved by designing CARs with an aim to increase the efficacy to toxicity ratio. CARs associated with low to moderate levels of in vitro cytokine production could be prioritized for development over CARs associated with high levels of cytokine production. Clinical development of the Hu19-CD828Z CAR is continuing with Hu19-CD828Z as one CAR in a biscistronic construct encoding Hu19-CD828Z and an anti-CD20 CAR.

Methods

Clinical trial information for Hu19-CD828Z

This trial was registered with Clinical Trials.gov (NCT02659943). All patients enrolled on the trial gave informed consent for participation. All 20 patients who were treated with Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells are the focus of the report. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute. An Investigational New Drug Application for LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z T cells was evaluated and permitted by the United States Food and Drug Administration. The full clinical trial protocol is included as “Hu19-CD828Z protocol 16-c-0054”. The primary objectives of the trial were assessment of safety and feasibility. There were several secondary objectives: 1) Evaluate the in vivo persistence and peak blood levels of anti-CD19 CAR T cells, including comparison of persistence results of Hu19-CD828Z T cells with persistence of T cells expressing FMC63–28Z, an anti-CD19 CAR containing an antigen-recognition moiety derived from a murine antibody. 2) Assess for evidence of anti-malignancy activity by anti-CD19 CAR T cells. 3) Assess the impact of repeated CAR T-cell infusions on residual malignancy after an initial CAR T-cell infusion. 4) Assess the immunogenicity of the CAR used in this protocol.

Patient enrollment on Hu19-CD828Z trial

The clinical trial included 2 cohorts, patients who had never received an allogeneic stem cell transplant and patients who had received an allogeneic stem cell transplant. Only 1 patient who had received an allogeneic stem cell transplant was enrolled, and this patient never received protocol treatment. Twenty-five patients were enrolled on the main cohort for patients who had never received allogeneic stem cell transplantation; twenty of these patients received protocol therapy and are all reported in this manuscript. Five patients were enrolled but never received CAR T cells because either clinical parameters changed so that patients no longer met protocol eligibility requirements and/or the CAR T-cell product did not meet certificate of analysis requirements (CoA). One patient had treatment cancelled because of rapid lymphoma progression causing decreased performance status. A second patient had treatment cancelled because of neutropenia. One patient had treatment cancelled for both thrombocytopenia and failure of the CAR T-cell product to meet CoA requirements due to a low percent CAR+ T cells in the clinical T-cell product. The fourth patient enrolled but not treated had treatment cancelled for both neutropenia and failure of the CAR T-cell product to meet CoA requirements due to a low percent CAR+ T cells among the clinical T-cell product. The fifth patient enrolled but not treated voluntarily withdrew from the protocol. Patients were enrolled between 1-21-2016 and 1-5-2018. Enrollment to the trial has permanently ceased. All patients received Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells between 2-17-2016 and 12-14-2017. Data was finalized (locked), on 5-7-2019. Patients were not formally recruited. Eligible patients were enrolled on a first-come, first-serve basis. A summary of enrollment of treated patients is provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Clinical trial information for FMC63–28Z

This trial was registered with Clinical Trials.gov (NCT00924326). All patients enrolled on the trial gave informed consent for participation. All patients treated between 9-27-2013 and 9-30-2015 are included in this report because all patients enrolled during this time-period received the same type of conditioning chemotherapy regimen and had CAR T cells prepared with similar culture approaches; this cohort of patients has been previously reported5. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute. An Investigational New Drug Application for the FMC63–28Z T cells was evaluated and permitted by the United States Food and Drug Administration. The full clinical trial protocol is included as “FMC63–28Z protocol 09-c-0082”.

Lymphoma staging and toxicity grading

Lymphomas were assessed with positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) scans and a bone marrow biopsy before treatment. The PET and CT scans were initially repeated 4–6 weeks after treatment, and imaging was repeated as called for by the clinical protocols. Patients with a pre-treatment bone marrow biopsy showing lymphoma were also assessed with bone marrow biopsies after treatment. The same lymphoma response categories were used by both the Hu19-CD828Z protocol and the FMC63–28Z protocol38. The response categories were as follows: complete remission (CR), absence of evidence of lymphoma; partial remission (PR), at least a 50% decrease in lymphoma size; progressive disease (PD), at least 50% increase in lymphoma size or appearance of new lymphoma lesions; stable disease (SD), a response not meeting criteria for CR, PR, or PD38. Duration of response was calculated as the time from first documentation of a PR or CR until documentation of progressive lymphoma or last response assessment of ongoing responses.

For the Hu19-CD828Z trial, all adverse events were graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version (v) 4.0 (https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf); these adverse events are reported in Supplementary Table 2. For comparing neurologic adverse events in this work, we graded both the Hu19-CD828Z trial and the FMC63–28Z trial by the CTCAEv3.0 (https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf). CTCAEv3.0 was used because the FMC63–28Z trial, which had a high incidence of neurologic toxicity, was originally graded by CTCAEv3.0. All adverse events on the Hu19-CD828Z trial were originally graded with CTCAEv4.0, but for a comparison of the two trials with the same adverse event reporting system, we converted the few neurologic adverse events on the Hu19-CD828Z trial to CTCAEv3.0. We graded CRS by using the system published in 2019 by Lee et al39. by a contemporaneous chart review of both the Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z trials. For this review, we defined hypotension as a systolic blood pressure <90 mm of mercury.

LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z lentiviral vector production

The design and construction of the LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z plasmid that was used to produce the clinical vector has been previously reported28. The LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z vector was produced by transient transfection by the Indiana University Vector Production Facility.

Hu19-CD828Z CAR T-cell production

Autologous Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) were collected by apheresis. Fresh PBMC underwent automated density gradient separation on a COBE 2991 cell processor (TerumoBCT) and were either cultured fresh or cryopreserved and later thawed for culture. Flow cytometry was performed to determine the percentage of PBMC made up of CD3+ cells; the number of PBMC used to initiate cultures was based on this CD3+ cell percentage. Unselected PBMC were used to initiate cultures. On day 0, fresh or thawed PBMC were placed in complete medium containing AIM-V CTS™ medium (Thermo/Life Technologies), 5% heat-inactivated pooled human AB serum (Valley Biomedical, Winchester VA), 300 IU/mL interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Proleukin; Prometheus Laboratories), and 50 ng/mL anti-CD3 (MACS® GMP CD3 pure, clone OKT3, Miltenyi Biotech). Cells were incubated in cell culture bags (Origen Biomedical) for 22–24 hours in a 37⁰C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator. On day 1, LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z vector was thawed and added, along with protamine sulfate, to the cell culture bags containing activated T cells. Cells were incubated 44–48 hours in a 37⁰C, 5% CO2 humidified incubator. After the incubation, on day 3 of culture, cells were removed from cell culture bags and resuspended in fresh medium at 0.5–1×106 cells/mL. On day 5, cells were counted and diluted to 0.5–1×106 cells/mL. Cultures were continued until day 7 to day 9 when cells were harvested, concentrated, washed either manually or on a COBE 2991 cell processor, and cryopreserved. The method of washing and concentration was determined by the number of cells in the cultures. CAR T cells were dosed as a specific number of CAR+CD3+ cells/kg of patient bodyweight.

CAR detection on transduced T cells by protein L staining:

To determine the percentage of infusion cells that expressed Hu19-CD828Z at the end of the 7 to 9-day cell production process, cell-surface CAR expression was detected by staining with biotin-labeled protein L (GenScript) followed by flow cytometry. The cells were also stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled streptavidin (BD), anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8. The percentage of CAR-expressing (CAR+) T cells was calculated as the percentage of T cells in CAR-transduced cultures that stained with protein L minus the percentage of identically-cultured untransduced T cells from the same donor that stained with protein L48.

Product-release criteria needed for cell infusion were as follows:

Appearance is milky white cell suspension

Trypan Blue Viability: ≥70%

% CD3+ of CD45+ viable cells: ≥90%

%CD19+ of viable cells: ≤3%

Transduction Efficiency (%CAR+ of viable CD3+): ≥15%

Endotoxin: < 5EU/mL

Sterility: No growth

Mycoplasma PCR-Negative

RCL-PCR: Negative; culture-based RCL testing performed later

MSGV-FMC63–28Z gamma-retroviral vector production

The design and preclinical testing of the MSGV-FMC63–28Z CAR has been previously reported29. The MSGV-FMC63–28Z gamma-retroviral vector, was produced by the same method as previously reported for other vectors49.

Production of FMC63–28Z T cells

Patients 22 to 28 on the FMC63–28Z trial all received 1×106 fresh (not cryopreserved) CAR-expressing T cells/kg of bodyweight. The fresh CAR-expressing T cells were produced by a method essentially identical to the method used in our prior work4. Patients 29 to 43 on the FMC63–28Z trial received cryopreserved cells; patients receiving cryopreserved cells received 2×106 CAR-expressing T cells/kg with the exception of patient 32 who received 6×106 CAR-expressing T cells/kg. The percentage of the total T cells in culture expressing FMC63–28Z was determined by flow cytometry as described below.

To prepare fresh FMC63–28Z T cells for clinical administration, unselected peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were cultured in flasks with media containing the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody OKT3 (50ng/mL) and human interleukin-2 (IL-2, 300 IU/mL) starting on day 0 of culture. On day 1 of culture, 6-well plates were coated with Retronectin™ (recombinant human fibronectin fragment CH296, Takara BioDivision) at 10 μg/mL diluted in PBS, and the plates were stored at 4°C overnight. The next day, the PBS was removed, and plates were blocked with 2.5% human serum albumin in PBS for 30 minutes. Plates were then washed and loaded with FMC63–28Z CAR gamma-retroviral vector by centrifuging the plates at 2000xg for 2 hours at 32°C. OKT3-stimulated cells were added into the vector-coated plates and centrifuged for 15 minutes. The plates containing the cells were then placed back into the incubator. The following day, transduced cells were collected and transferred to new flasks for further culture. On day 10, cells were harvested and washed. Cells were suspended in 0.9% sodium chloride containing 2.5% human serum albumin (HSA) for fresh infusion.

The cryopreserved FMC63–28Z T cells received by patients 29 to 43 on the FMC63–28Z trial were produced by a method similar but not identical to the process described above for fresh FMC63–28Z T cells. On day 0, PBMC were cultured in PermaLife bags (OriGen Biomedical) at 1×106 cells/mL in serum-free media Optimizer CTS with T-cell Serum Replacement (LifeTechnologies). T cells were activated with OKT3 at 50 ng/ml and IL-2 (300 IU/ml) for 2 days. On day 1 new PermaLife bags were coated with retronectin (10 μg/mL) and stored at 4°C overnight. On day 2, liquid was removed from the bag, and the bag was washed once with a 2.5% HEPES in Hank’s balanced salt solution (Lonza). Retroviral vector supernatant was then added to retronectin-coated bags and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. For untransduced control cells, bags were loaded with medium only. The activated PBMC were washed using the Sepax II, an automated closed system for processing blood-derived cell products. Cells were then transferred to the retrovirus loaded bags at a concentration of 0.5 ×106 cells/mL and incubated at 37°C. On day 3, cells were transferred into new bags for further proliferation. The entire culture period from initiation until cryopreservation was 6 to 9 days. On the day of cryopreservation, the cells were washed with 0.9% saline with the Sepax II. The FMC63–28Z T-cell product was formulated in CS250 cryostorage bags (OriGen Biomedical) at the target dose. T cells were suspended in a solution containing 0.9% saline plus 5% HSA and a 1:1 volume of Cryostor 10 (BioLife Solutions) was added. The cells were frozen in a controlled-rate freezer (Planer) and stored in vapor phase liquid nitrogen. On the day of infusion, the frozen cells were thawed at 37°C and infused into patients within 2 hours.

CAR detection on FMC63–28Z infusion T cells by anti-Fab antibody staining to determine clinical T-cell dose

This method was used to determine the percentage of CAR+ T cells among infusion FMC63–28Z T cells. For each patient, a sample of FMC63–28Z-transduced cells was stained with biotin-labeled polyclonal goat anti-mouse-F(ab)2 antibodies (anti-Fab, Jackson Immunoresearch) to detect the CAR. A sample of untransduced identically-cultured cells from the same donor was stained with the anti-Fab antibodies as a control. Next, the cells were all stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled streptavidin (BD), anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8. The percentage of FMC63–28Z-transduced T cells that expressed the CAR (CAR+ T cells) was calculated by subtracting the percentage of untransduced CD3+ cells that were stained with the anti-Fab antibodies from the percentage of FMC63–28Z-transduced CD3+ cells that were stained with the anti-Fab antibodies. Product-release criteria for FMC63–28Z T cells are in (Supplementary Table 6).

Ex vivo and infusion cell flow cytometry

For the T-cell phenotype of Hu19-CD828Z infusion T cells (Figure 1c, Figure 2b–f, and Supplementary Figures 1,2 and 4), freshly thawed PBMC were stained, and all plots are gated on live lymphocytes. Flow cytometry was performed with a Beckman Coulter Gallios flow cytometer and data were analyzed with FlowJo. The following antibodies were used in these experiments.

| PANEL 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Part number | Antigen and fluorochrome |

| BD | 555346 | CD4 FITC |

| Kite Pharma | Anti-CAR antibody | CAR PE |

| Beckman Coulter | IM2711U | CD45RA ECD |

| Sigma | A9400 | 7-AAD |

| Biolegend | 329918 | PD1 PE-Cy7 |

| R&D Systems | FAB197A-100 | CCR7 APC |

| BD | 557943 | CD3 Alexa Fluor 700 |

| BD | 561137 | CD45RO APC-H7 |

| Ebioscience/Invitrogen/ThermoFisher | 48-0279-42 | CD27 e450 |

| BD | 563256 | CD8 bv510 |

| PANEL 2 | ||

| Manufacturer | Part number | Antigen and fluorochrome |

| Biolegend | 322306 | CD57 FITC |

| Kite Pharma | Anti-CAR antibody | CAR PE |

| Biolegend | 302942 | CD28 PE-DAZZLE |

| Sigma | A9400 | 7-AAD |

| Biolegend | 329918 | PD1 PE-Cy7 |

| Biolegend | 368605 | KLRG1 APC |

| BD | 557943 | CD3 Alexa Fluor 700 |

| Biolegend | 300517 | CD4 APC-Cy7 |

| Biolegend | 345007 | Tim-3 bv421 |

| BD | 563256 | CD8 bv510 |

Real-time qPCR for measuring blood CAR+ cell levels

For each patient on both the Hu19-CD828Z trial and the FMC63–28Z trial, DNA was extracted from PBMC collected before treatment and at multiple time-points after treatment. DNA was extracted by using a Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit. DNA from each time-point was amplified in duplicate with a primer and probe set (Applied Biosystems) that was specific for either Hu19-CD828Z or FMC63–28Z. Real-time PCR was carried out with a Roche Light Cycler 480 real-time PCR system. Similar to an approach used previously by other investigators, we made serial 1:5 dilutions of DNA from the infusion T cells of each patient into pretreatment DNA from the same patient, and we made standard curves by performing qPCR on this DNA50,51. We determined the percentage of the infusion T cells that were CAR+ by flow cytometry. We assumed that only infusion T cells with surface CAR expression detected by flow cytometry contained the CAR gene. This assumption probably underestimates the actual number of cells containing the CAR gene because all cells containing the CAR gene might not express the CAR protein on the cell surface. To determine the percentage of PBMC that contained the CAR gene at each time-point after CAR T-cell infusion, we compared the qPCR results obtained with DNA of PBMC from each time-point to the qPCR results obtained from each patient’s infusion cell standard curve. All samples were normalized to β-actin with an Applied Biosystems β−actin control reagents kit. After the percentage of CAR+ PBMC was determined by PCR, the absolute number of CAR+ PBMC was calculated by multiplying the percentage of CAR+ PBMC by the sum of the absolute number of blood lymphocytes and monocytes.

The qPCR reactions with different primers and probes had to be used for Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z because the DNA encoding the different CARs had little sequence in common. The PCR reactions were comparable. The lower limits of detection of both PCR reactions were not different. The mean lower limit of detection for the Hu19-CD828Z PCR was 0.04% (range 0.003–0.111%), and the mean lower limit of detection for the FMC63–28Z PCR was 0.07% (range 0.004–0.294%). The R2 for all qPCR assays was 0.99.

Anti-CAR antibody staining

These methods apply to the data shown in Figure 2j–k. Cryopreserved patient peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected one month after CAR T-cell infusion were thawed and then washed once with FACS buffer containing 0.4% BSA and 0.1% weight/volume sodium azide in PBS. Samples were Fc blocked with normal mouse IgG (Invitrogen) and stained with CD3-APC Cy7 (UCHT1, eBioscience), CD4 FITC (RPA-T4, BD), CD8 PECy7 (RPA-T8, BD), 7-amino actinomycin D (7AAD, BD), and anti-CAR-APC antibody (the anti-CAR antibody was generated by Kite Pharma, Inc.). The anti-CAR antibody bound equivalently to the linker in the scFv of both Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z (Supplementary Figure 3)35. Samples were acquired using a BD LSR II with Diva software and data was analyzed using FlowJo version 10. The gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure 7.

Co-culture of anti-CD19 CAR infusion cell samples with target cells

This section describes methods for Figures 3a–b and Supplementary Figure 5. Cryopreserved anti-CD19 CAR T-cells were quickly thawed in a 37°C water bath and washed in RPMI media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (VWR Scientific), 1X penicillin, streptomycin and glutamine (VWR Scientific) and 1X HEPES (Lonza). Cellular viability and concentration were determined using a Vi-cell (Beckman Coulter). Cell densities were adjusted to 1×106 viable cells per mL. Cells were incubated overnight in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell counts and viability determinations were repeated the following day. In parallel, cultures of target cell lines CD19-K562 (CD19+) and NGFR-K562 (CD19-negative) were assessed for viability and cell concentration using a Vi-cell. CD19-K562 and NGFR-K562 cells were generated in our lab by obtaining K562 cells from ATCC and transducing them with gamma-retroviral vectors encoding either the gene for CD19 or the gene for low-affinity nerve growth factor (NGFR). Expression of either CD19 or NGFR was confirmed by flow cytometry on CD19-K562, and NGFR-K562, and all cells were mycoplasma negative. Final cell concentrations were adjusted to 2.5×105 cells/mL for both target cell lines and T cells. Viable target cells (2.5×104) and viable CAR T cells (2.5×104) were combined into individual wells of a 96-well U-bottom plate in duplicate. In addition, as controls, CAR T-cell-only and target-only (CD19-K562 and NGFR-K562) cultures were run at the same time as co-culture replicates. All cultures were incubated overnight (~18 hours) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The following day, supernatants were harvested by centrifugation and transferred into a fresh 96-well U-bottom plate. Supernatants were stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis.

Measurement of serum immunological proteins

Patient serum samples were harvested and processed according to institutional guidelines and held at −80°C for subsequent analysis. Serum analytes were measured by Luminex® (EMD Millipore). Prior to processing, serum samples were thawed on ice and aliquoted into 96 well u-bottom plates (BD Biosciences). The following kits and dilutions were utilized to assay all proteins listed in Extended Data Table 3: HCYP2MAG-62K-04, HCVD2MAG-67K-03, HCYTOMAG-60K-26, HAGP1MAG-12K-03, HCVD3MAG-67K-01, and HCD8MAG-15K-04. All assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s specifications for serum analyte testing. Quality and assay standard controls were included for independent runs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Experimental replicates were assayed in duplicate. Samples were read on a Luminex 200 system (Bio-Rad). Analyte values were reported as pg/mL.

T-cell culture and transduction for in vitro experiments

This section describes how T cells were cultured and transduced for experiments reported in Figures 4 and 5. Patient PBMCs were suspended at 1×106 cells/mL and stimulated with 50 ng/mL of OKT3 antibody (Miltenyi) and cultured in T-cell culture media. T-cell culture media consisted of AIM V media with 5% heat inactivated human AB serum (Valley Biomedical), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 ug/mL streptomycin, and 300 IU/mL IL-2. After 24 hours in culture, cells to undergo lentiviral transduction were washed and resuspended in the original culture media at 1×106 cells/mL. Lentiviral supernatant and 4×106 T cells in T-cell culture media were added to a tissue-culture-treated plate along with 40 μg protamine sulfate and incubated at 37○C and 5% CO2. After 44–48 hours, T cells were removed from transduction plates and cultured at 0.5 ×106 cells/mL in fresh T-cell culture media.

PBMCs to undergo gamma-retroviral transductions were stimulated with OKT3 in T-cell culture media in the same manner as described above for lentiviral transductions. For gamma-retroviral transductions, T cells were cultured in vitro for 48 hours prior to transductions. Gamma-retroviral supernatant was added to RetroNectin (Takara) coated plates and incubated for 2 hours at 37○C. T cells were then added at 1×106 cells/mL in 2 mL of media to the gamma-retroviral supernatant in a 1:1 volume ratio of vector supernatant to cell solution and supplemented with IL-2 at a final concentration of 300 IU/mL. After 18 hours, T cells were removed from transduction plates and cultured at 0.5×106 cells/mL in the same conditions as lentiviral transduced T cells.

Co-cultures for in vitro CAR comparisons

This section describes how T cells were co-cultured with target cells for experiments in Figure 5. On day 9 of culture, effector T cells transduced with LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z, LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z, LSIN-Hu19–28Z, MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z, or MSGV-FMC63–28Z were stained with anti-CAR-APC to determine the percent anti-CD19 CAR+ T cells by flow cytometry as described above under “Anti-CAR antibody staining.” Each effector T cell culture was then normalized with untransduced T cells so that all cultures had an equal percentage of CD3+CAR+ cells. This was accomplished by resuspending all CAR-transduced T cells and untransduced T cells to 1×106 cells/mL and adding the appropriate number of untransduced T cells to each CAR T-cell culture so that each T-cell culture had the same %CD3+CAR+ cells as the CAR T-cell culture that originally had the lowest %CD3+CAR+ cells. CD19-K562 and NGFR-K562 target cells are described above under “Co-culture of anti-CD19 CAR infusion cell samples with target cells.” NALM6 cells were from DSMZ and were confirmed to be CD19+ and mycoplasma negative. CD19+ CD19-K562, CD19+ NALM6, and CD19-negative NGFR-K562 cells were washed twice and resuspended to 1×106 cells/mL in T-cell culture media. Co-cultures with 1:1 ratios of cells from CAR T-cell cultures to target cells were added to designated wells of a 24-well plate and incubated at 37○C and 5% CO2. After 18 hours, the co-culture plate was centrifuged at 2,000 RPM for 10 minutes and the supernatants were harvested and stored at −80○C.

Measurement of immunological proteins in co-culture supernatants by Luminex® or Meso Scale Discovery assays

This section describes experiments reported in Figure 3a–b and Figure 5a–g, and Supplementary Figure 5. Supernatants from co-cultures of CAR T cells and target cells were thawed on ice and analyzed by Luminex® (EMD Millipore) by the manufacturer’s protocol. The following analytes were measured: GM-CSF, sCD137, Granzyme B, IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-6, and TNFα. IL-17A was measured by Meso Scale Discovery. Quality and assay standard controls were included for independent runs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Experimental replicates were assayed undiluted or at a 1:20 dilution for Luminex™ across all culture conditions. For MSD assay, experimental replicates were assayed undiluted or at 1:100 dilution. CD19-specific protein release was calculated for Figure 3a–b, Figure 5a–g, and Supplementary Figure 5 according to the following formula:

[(CD19-K562 + Anti-CD19 CAR T cells) – (CD19-K562)] - [(NGFR-K562 + Anti-CD19 CAR T cells) – (NGFR-K562)] = reported value (pg/mL). This means: 1. protein concentrations in wells with CD19-K562 cells alone were subtracted from protein concentrations in wells with CD19-K562 cells plus anti-CD19 CAR T cells. 2. Protein concentrations in wells with NGFR-K562 cells alone were subtracted from protein concentrations in wells with NGFR-K562 cells plus anti-CD19 CAR T cells. 3. The value from 2 was subtracted from the value from 1. Protein release values in Figure 3a–b were normalized for CAR expression by dividing the protein values by the %CAR+ cells from each patient’s CAR infusion cells. In Figure 5, all CAR T-cell cultures were adjusted to have an equal %CAR T cells in the cultures as described under “Co-cultures for Luminex and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays”, above. Also in Figure 5, use of the word “consistent” means that in 6 of 6 independent experiments the same CAR of 2 CAR being compared gave higher cytokine release.

ELISA and CD107a assays

This section describes IFNγ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) done in experiments reported in Figure 5a–b. One hundred thousand effector T cells were combined with 100,000 target cells in each well of 96 well plates. Target cells used were CD19-K562, NALM6, and NGFR-K562. Wells were set up in duplicate. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18–20 hours. Following the incubation, ELISAs were performed using standard methods (Thermo).

CD107a assays were performed for experiments reported in Figure 5h–i. For each T- cell culture tested, two tubes were prepared. One tube contained NALM6 cells, and the other tube contained NGFR-K562 cells. Both tubes contained CAR-transduced T cells, 1 ml of T-cell culture medium, a titrated concentration of an anti-CD107a antibody (Thermo Catalog #A15798, clone H4A3), and 1 μL of Golgi Stop (monesin, BD). All tubes were incubated at 37°C for 4 hours and then stained for CD3, CD4, and CD8.

Statistics

Two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank tests were used for paired data analyses as indicated in figure legends. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare all unpaired data as indicated in figure legends. P values were not corrected for multiple comparisons. The area under the curve data in Extended Data 6 was approximated with the trapezoidal rule. Categorical data were compared with a Fisher’s exact test. Event-free survival is presented in Figure 1 as a Kaplan-Meier plot prepared with GraphPad Prism. SAS version 9.4 or GraphPad Prism 7 were used for all statistical analyses. Cytokine assays on patient serum were performed in duplicate wells, but entire experiments were generally not repeated due to limited clinical materials. In vitro culture experiments and flow cytometry experiments in Figures 4 and 5 were repeated 6 times with cells from 6 different donors. No randomization was carried out. No blinding was conducted. The number of samples in each experiment is indicated in the figure legends.

Protein structure modeling

Homology modeling was used to generate structures of each CAR segment separately (scFv, hinge, transmembrane, intracellular domain). The initial partial models were obtained using structure prediction methods including: SwissModel (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/); Phyre2 (www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/); I-Tasser (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) and Robetta (robetta.bakerlab.org) The structures of the hinges were further refined using Feedback Restrained Molecular Dynamics (FRMD)52,53 as implemented in X-plor-NIH (https://nmr.cit.nih.gov/xplor-nih/). FRMD affords a simple protocol to bias a molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory towards a consensus arrangement, allowing the combination of multiple structures. The best models for each section were selected based on compactness, energy, and the exposure of the N and C termini to facilitate their connection to other segments. The partial models were homo docked to form C2 (two-fold rotation axis) symmetric dimers using the program ZDOCK (http://zdock.umassmed.edu). The dimerized partial models were combined by first inserting the trans-membrane region in a model membrane and subsequently attaching the other segments followed by constrained relaxation. In this work, we used the Lipid14 extension using a very soft restraint in the lipid heavy atoms (0.1kcal/mol.A2), and we followed the recommendations in Marrink et al.54. The very soft restraint is sufficient to stabilize the membrane while allowing enough flexibility for the transmembrane domain. Initial models were annealed in an explicit solvent box using MD simulations. All MD calculations were performed using Gromacs 5.1.4 (http://www.gromacs.org) with the AMBER Force field and default parameters in the NPT ensemble. Coarse grain MD simulations were performed to accelerate the exploration of conformations and to compute the diffusion coefficients55. Finally, full atom MD production trajectories (25 to 50 ns) were collected after stabilization. Extended Data Figure 2 presents a representative conformation of the CAR (top) and a set of conformations most representative of the flexibility observed during the MD trajectories (bottom). The set of conformations was selected using a principal component analysis procedure based on root-mean-square deviation values.

ELISPOT

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays were performed by Cellular Technology Limited (Cleveland, OH) as previously described with minor modifications42. To test the immunogenicity of the constructs, we generated 4 peptide pools for the Hu19-CD828Z CAR (hBinA, hBinB, hBinC and hBinD) and 4 peptide pools for the FMC63–28Z CAR (mBinA, mBinB, mBinC and mBinD). The peptide bins used to assess construct immunogenicity were composed of 15mer peptides >95% purified with 5mer-overlaps in C terminals and N terminals (Supplementary Table 7). Ninety-six well-ELISPOT plates (BioWhittaker) were coated overnight at 4 °C with 50 μL capture antibody in PBS (anti-IFN-γ M700A-E, 2 μg/ml; Endogen) then blocked with bovine serum albumin fraction V (10 g/L in PBS) for 60 minutes and washed three times with PBS. Live frozen PBMCs were thawed and incubated at 4.0 × 105 cells per M700A-E-coated well for 24 h at 37 °C, 7% CO2, in complete RPMI medium (94% RPMI, 1% l-glutamine, 5% heat-inactivated human AB serum). Medium alone served as negative control and phytohemagglutinin (PHA) at 5 pg/ml served as positive control. Four positive control samples were identified in a library of 40 normal donors (CTL e-PBMC® library) with low background (BG) in medium (spot forming cells per well ‘SFC’ below 10), SFC 302 ± 31 with peptide stimulation, and TNTC (“too numerous to count” > 1,000 spots) after PHA activation; two of the 4 donors were used as positive controls during patient sample screening. After cell incubation with mitogen or peptide pools, ELISPOT plates were washed three times with PBS, three times with PBS-TWEEN (0.5%), and captured IFN-γ was detected by anti-IFNγ 133.5 biotin (2 μg/ml; Endogen). After overnight incubation at 4 °C, plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween and incubated 120 min with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (50 μl/well) at 1:1000. Development solution (BCIP/NBT Phosphatase Substrate, KPL) was added, and the reaction was stopped after spots became visible. Image analysis on a Series 3 ImmunoSpot Image Analyzer (Cellular Technology) was performed after overnight air-drying.

Data availability

All requests for raw and analyzed data and materials are promptly reviewed by the National Cancer Institute Technology Transfer Center to verify if the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Patient-related data not included in the paper were generated as part of clinical trials and may be subject to patient confidentiality. Any data and materials that can be shared will be released via a Material Transfer Agreement. All other data that support the findings of this study will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request when possible. Raw data for all Figures (Figures 1–5) and Extended Data Figure 3 is in the submitted Source Data Excel file.

CAR sequences were all submitted to GenBank.

GenBank accession number for LSIN-Hu19-CD828Z: MN698642

GenBank accession number for LSIN-FMC63-CD828Z: MN702884

GenBank accession number for LSIN-Hu19–28Z: MN702882

GenBank accession number for MSGV-Hu19-CD828Z: MN702883

GenBank accession number for MSGV-FMC63–28Z: HM852952.1

Extended Data

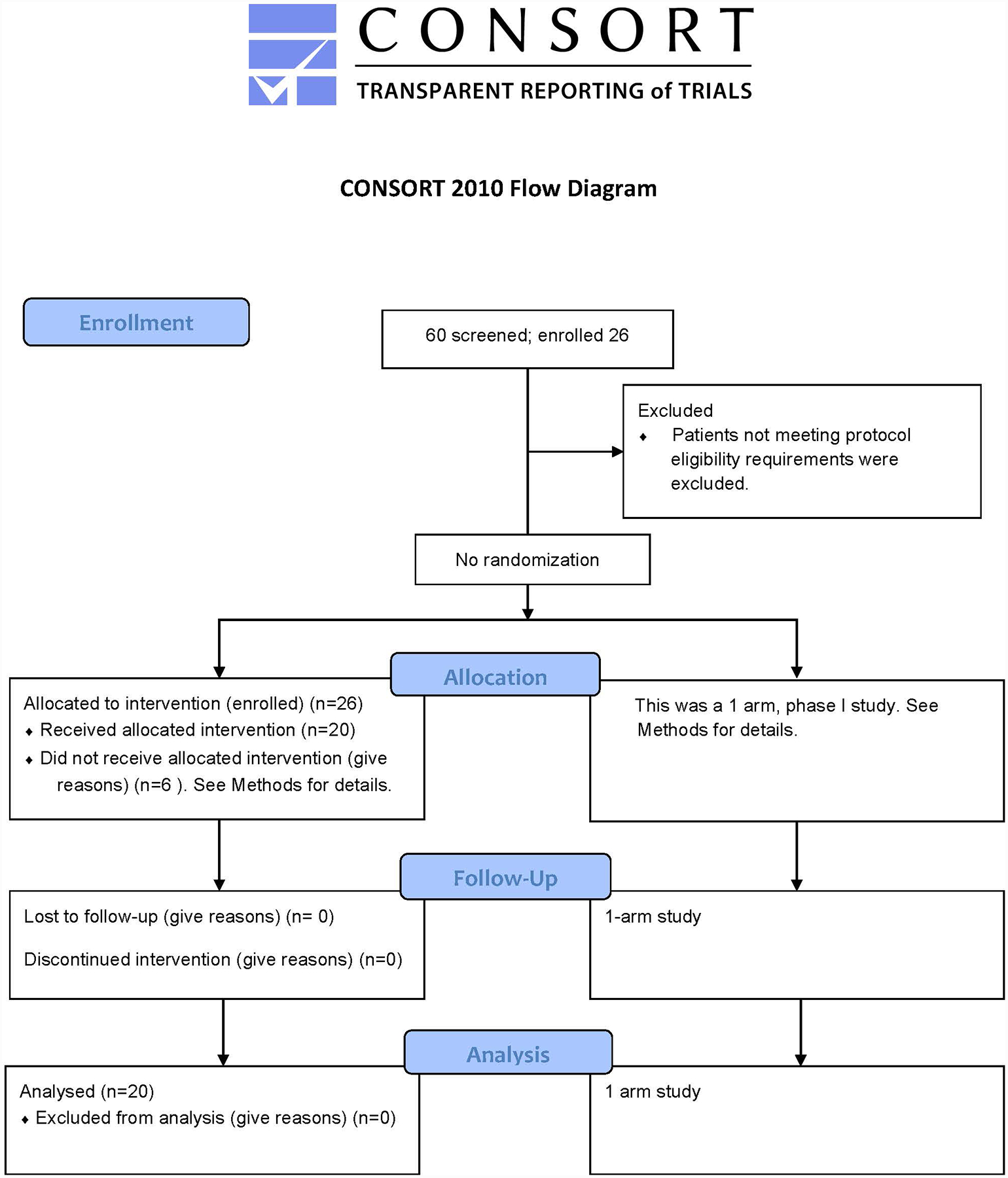

Extended Data Fig. 1. CONSORT.

Consort diagram of the Hu19-CD828Z clinical trial.

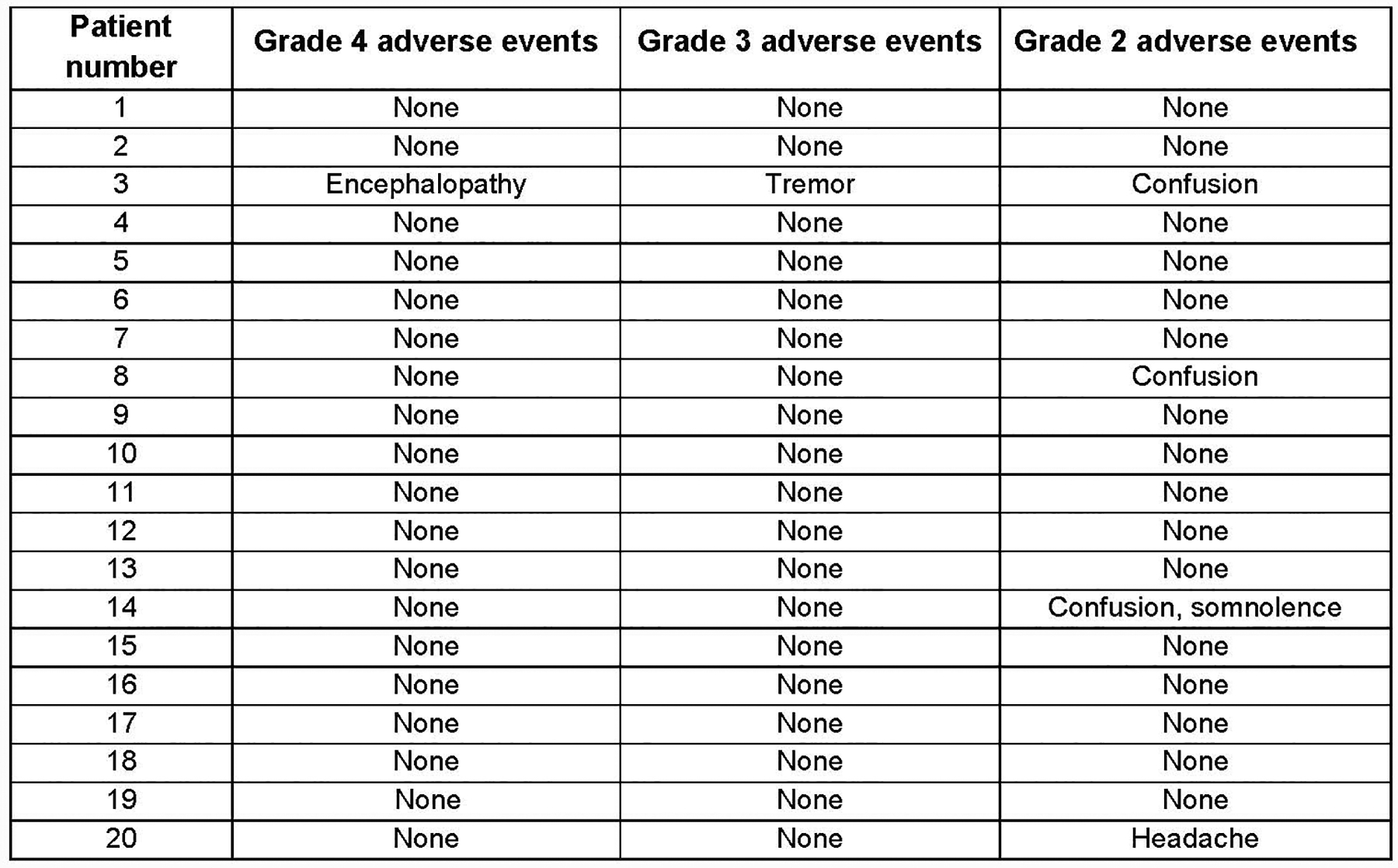

Extended Data Fig. 2. Hu19-CD828Z neurologic toxicities.

Neurologic toxicity with Hu19-CD828Z. All grade 4, 3, and 2 neurologic adverse events within the first month after CAR T-cell infusion are listed. Grading by National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3; all adverse events listed under “Neurologic” are included except syncope. Syncope was not included because it was associated with cytokine-release syndrome and hypotension. The highest grade of each adverse event experienced by each patient is listed. For example, if a patient had both Grade 2 and Grade 3 tremor at different times, tremor is only listed under Grade 3.

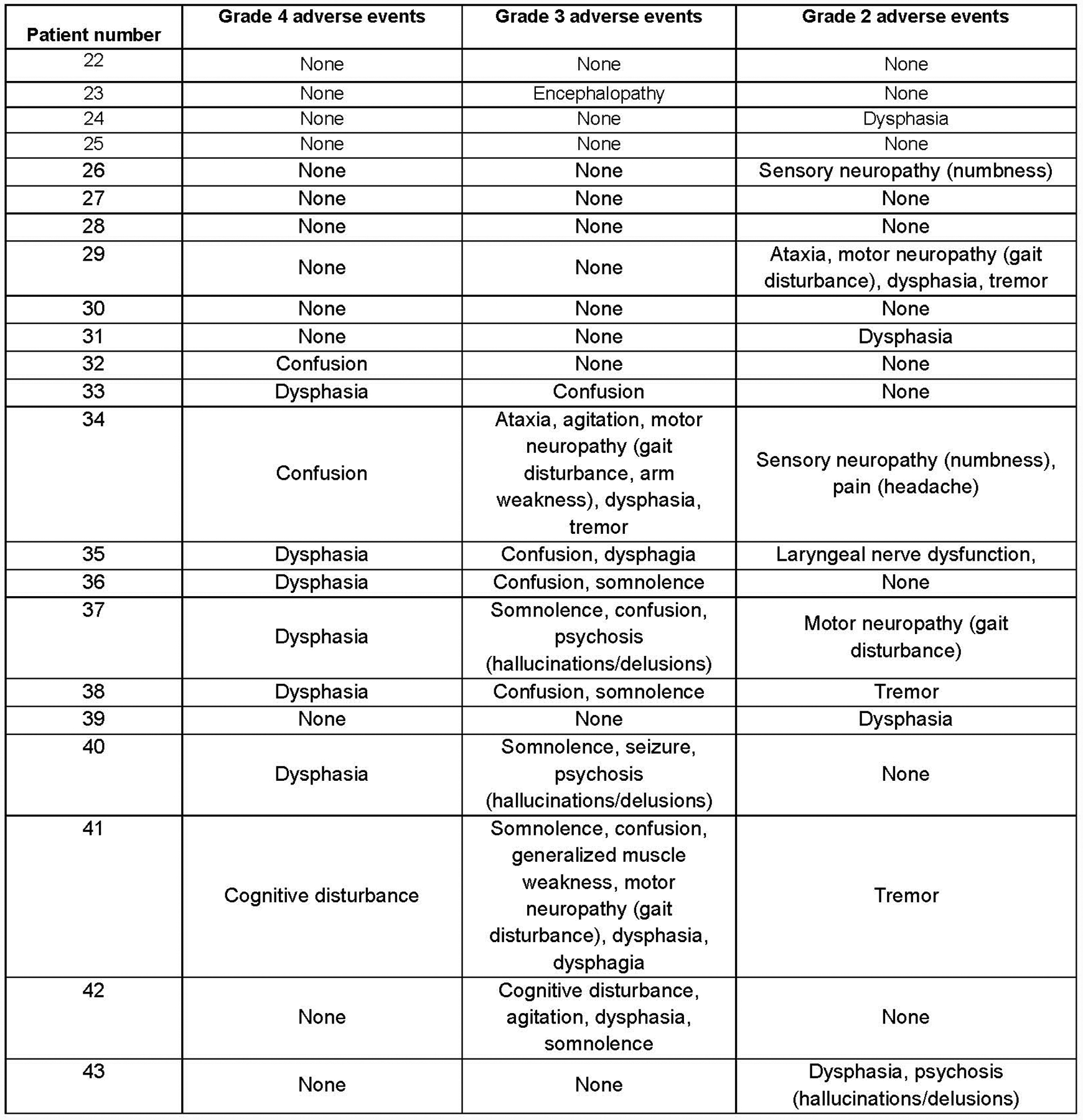

Extended Data Fig. 3. FMC63–28Z neurologic toxicities.

Neurologic toxicity with FMC63–28Z. All grade 4, 3, and 2 neurologic adverse events within the first month after CAR T-cell infusion are listed. Grading by National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 3; all adverse events listed under “Neurologic” are included except syncope. Syncope was not included because it was associated with hypotension from cytokine-release syndrome. The highest grade of each adverse event experienced by each patient is listed. For example, if a patient had both Grade 2 and Grade 3 confusion at different times, confusion is only listed under Grade 3.

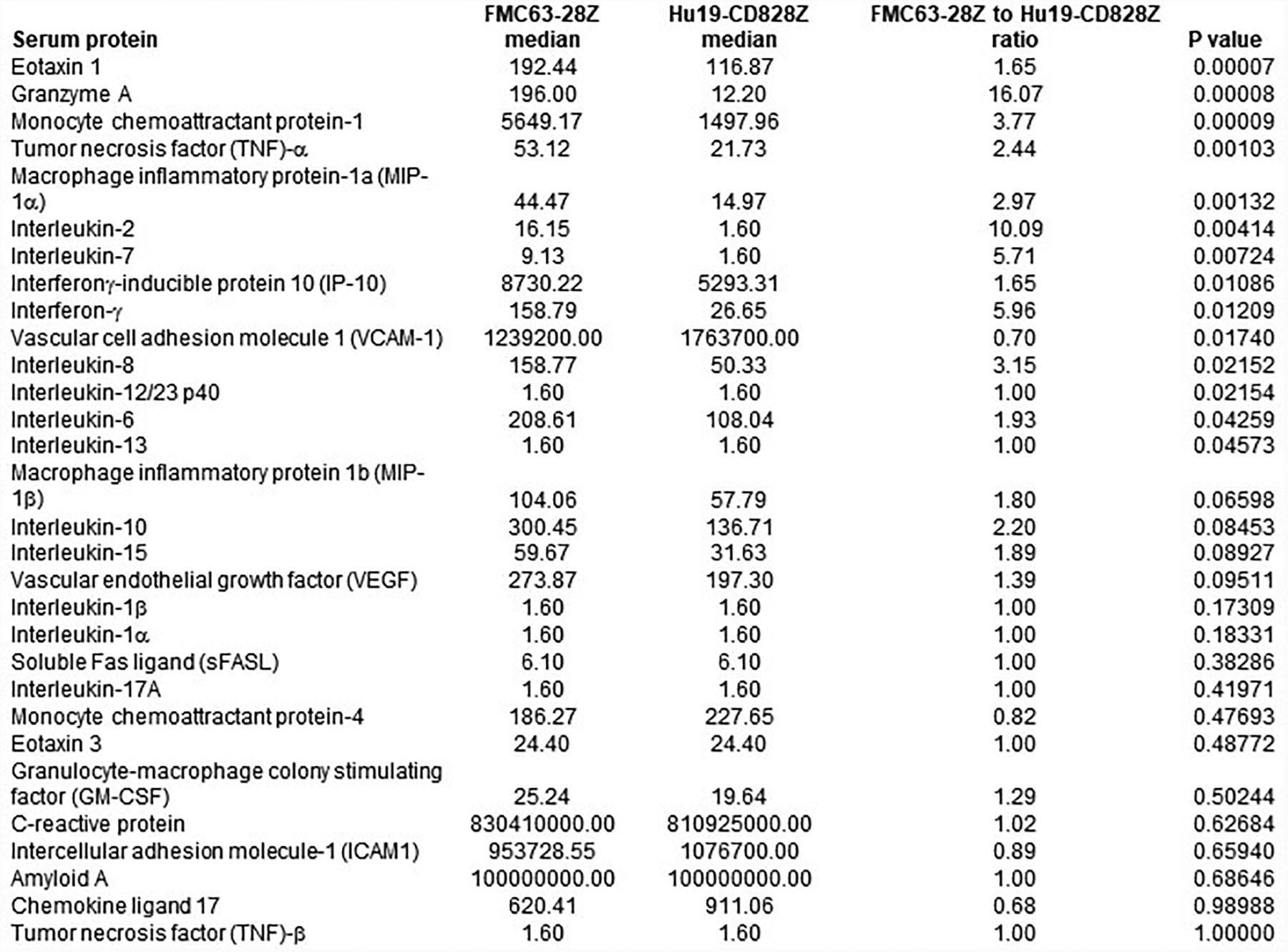

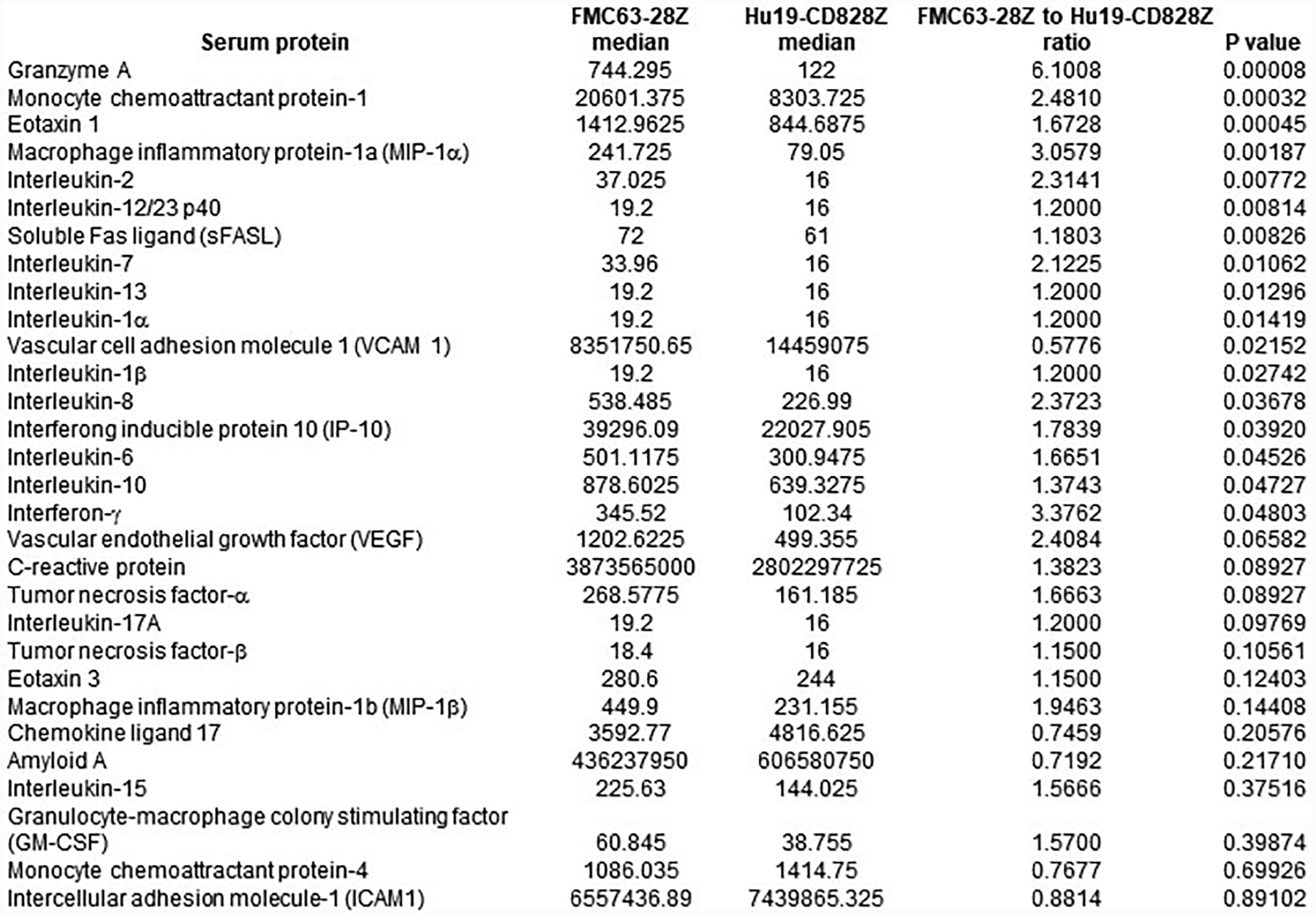

Extended Data Fig. 4. Peak serum protein levels.

Peak immunologic protein levels. For all proteins, all 22 patients on the trial of FMC63–28Z T cells and all 20 patients on the trial of Hu19-CD828Z T cells were compared. Proteins were measured in serum samples by Luminex® assay between day 2 and 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. Statistics were by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Patient 3 immunologic protein levels.

Patient 3 serum immunologic protein levels. Patient 3 was the only patient with Grade 3 or 4 neurologic toxicity on the Hu19-CD828Z trial. Peak serum levels of 9 immunological proteins are shown for Patient 3. Peak levels were determined between day 2 and day 14 after CAR T-cell infusion. These 9 proteins are shown because they were found to be prominently different between the Hu19-CD828Z and FMC63–28Z clinical trials (Figure 3). Proteins were measured by Luminex® assay. MCP-1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1; IL, interleukin; TNF-alpha, tumor necrosis factor-alpha; MIP-1-alpha, macrophage inflammatory protein-1-alpha; IFN-gamma, interferon-gamma. The red bars indicate the median protein levels for all 20 patients that received Hu19-CD828Z CAR T cells.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Serum proteins areas under the curves.