Abstract

This study examined health literacy of postpartum education materials assessing readability, understandability and cultural sensitivity using common health literacy measures. Materials examined rated poorly on measures of health literacy and cultural sensitivity using evidence-based measures including the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT), Fry-based Readability and National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS). Findings suggested a need for health literate and culturally sensitive postpartum education. Materials and an App were developed for new moms to help them identify postpartum warning-signs and appropriate action moms should take to address symptoms or seek emergent care.

Keywords: Health Literacy, Maternal Mortality, Postpartum Education, Postpartum, Health Disparities

Background

As Congress embarks on an investigation into dangerous safety lapses in hospital practices surrounding maternal deaths in the United States, referred to by USA Today as “Deadly Deliveries,” questions should arise regarding postpartum women’s education and understanding of deadly warning signs at home and whether health literacy could play a role in maternal mortality (Young, 2019). Maternal Mortality is a global public health issue with local urgency. Globally, approximately 830 women die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth (World Health Organization, 2018). The maternal death rate ranges from 12-239 per 100,000 live births globally between developed and developing countries respectively (WHO, 2018). In 2015, the U.S. maternal death rate was 26.4 per 100,000 live births (GBD, 2015). This rate is more than triple the 1987 U.S. rate of 7.2 deaths per 100,000 births. A study published in 2018 stated the Texas rate at 14.6 per 100,000 live births, a still unacceptable rate (Baeva, Saxton, Ruggiero, Kormandy, Hollier, Hellerstedt et al., 2018). Most maternal deaths in Texas occur after delivery and up to 365 days post-delivery (TXDSHS, 2016). Despite differences in rate measurement procedures, moms should not be dying at these high rates as both exceed the rates of other developed countries (GBD, 2015).

Disparities

Although the death rates are alarming, even more disturbing is the fact that black women bare the greatest risk of dying during or shortly after childbirth, when compared with white women (TXDSHS, 2016). African American mothers are three to four times more likely than all other races to die or suffer devastating childbirth-related injuries (TXDSHS, 2016). Roman et al. (2017) found two global themes causing disparate care for African American women 1) difficulties understanding and communicating with their providers; and 2) socioeconomic and racial bias in care (Roman, Raffo, Dertz, Agee, Evans, Penniga, et al., 2017). Additional disparities exist for women at extremes of maternal age, women from low-income households, and women from rural areas (TXDSHS, 2016). Women from these higher risk groups are more likely to die during pregnancy, particularly when they live with more than one risk factor.

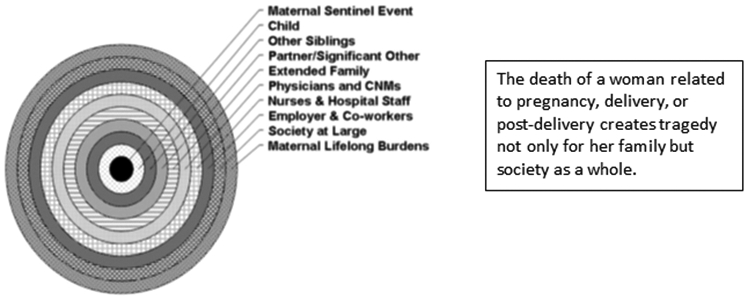

The reasons for these disparities although poorly understood, undoubtedly reflect complex social determinants of health including health literacy and biases in care delivery (King, 2012). Therefore, maternal deaths not only reflect complex social determinants, but they also continue the cycle of risk (Figure 1) (King, 2012). In other words, maternal mortality results in demographic, economic, health, psychological and social implications for children, families, households, communities and society that perpetuate social determinants that ultimately contributed to the maternal death.

Figure 1:

Graphical representation of the ever-widening “ripple effect” of an adverse event—either maternal death or near-miss—on societal groups with relation to an obstetric patient5

(King J. (2012). Maternal Mortality in the United States - Why Is It Important and What Are We Doing About It? Seminars in Perinatology, 36(1), 14-18. – with permission.)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0146000511001509?via%3Dihub

Significance

The World Health Organization considers most maternal deaths to be preventable (WHO, 2018). In 2016, the Joint Biennial Report for the Legislature by the Texas Department of State Health Services Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force defined maternal mortality as not only including during pregnancy but also up to 365 days following pregnancy termination; this definition varies by state (TXDSHS, 2016). The report also indicated five diagnoses usually associated with maternal death: 1) cardiac event, 2) drug overdose, 3) hypertension/eclampsia, 4) hemorrhage, and 5) sepsis (TXDSHS, 2016). Although these harmful diagnoses could be prevented, women continue to die each year as a result of pregnancy or delivery complications. The Center for Disease Control defines “pregnancy related death” as the death of a women while pregnant or within 1 year of the end of pregnancy regardless of outcome, duration or site of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes (CDC, 2016). During 2011-2012, the majority of maternal deaths in Texas occurred after delivery and a 1:50 ratio existed for mortality to morbidity (TXDSHS, 2016). Therefore, it is imperative to address potential issues in postpartum education regarding maternal care at home. Compounding social determinant disparities, health literacy (the ability of people to understand and use health information) disparities impact women’s ability to receive appropriate care, make informed decisions and adhere to clinical recommendations.

Women may not understand if symptoms after birth are normal or abnormal requiring medical attention (Suplee, Bingham & Kleppel, 2017). In addition to the vast information taught at discharge, a woman’s ability to understand is influenced by other factors, such as culture, degree of sleep deprivation, physical and emotional changes, possible side effects of medications, and low health literacy (Chugh, Williams, Grigsby, & Coleman, 2009; Roman, 2017). Suplee, et al. (2017) suggests that improving postpartum education could improve women’s ability to recognize and respond to warning signs. In addition, multiple health care access barriers that exclude women from receiving appropriate care in the prenatal period that do not necessarily abate in the postnatal period. Heaman, Sword, Elliott, Moffatt, Helewa & Morris et al., (2015), found these barriers include but are not limited to 1) lack of child care and/or transportation, 2) substance addictions, 3) lack of support system, 4) poor understanding of the need for care, 5) systemic failures and emotional distress (inability to understand health care navigation, unanswered phone calls, feelings of shame), 6) shortages of providers limiting appointment availability, and 7) program/service characteristics (distance, long waits, short visits). This presents a public health issue ultimately influencing a woman’s health outcomes for both her and her children. The death of a mother has a significant impact associated with a two to fifty times increase risk of death among the children under five years old that she leaves behind (Atrash, 2011). In addition, the result of a woman’s death not only represents the loss of her contribution to her family but also to her community: maintaining the household, providing nutrition, protecting the health and facilitating education of children, earning income to provide basic needs and contributions to the workforce. These findings of Atrash (2011), support the reported “ripple effect” described by King (2012) regarding the impact of maternal mortality as a public health issue not only for the mothers themselves but the health and well-being of generations to come.

The healthcare system places undue demands on patients, even while assuming that they understand their own health conditions and have the ability to take the appropriate action. Health education materials are complex, and access to health information is fraught by complexities such as medical jargon and disorganization that can overwhelm even the most literate patients. Research indicates that when postpartum women cannot follow instructions on medications, labels, and health messages, health outcomes can be poor potentially exacerbating and leading to the top 5 causes of postpartum death listed earlier (Suplee et al., 2017, TXDSHS, 2016). This suggests that improving postnatal education through more health literate communication can improve health outcomes for postpartum women. Healthy People 2020 objectives aim to improve health care communication overall and can be applied to help improve postnatal education: (HC/HIT-1.1) “Increase the proportion of persons who report their health care provider always gave them easy-to-understand instructions about what to do to take care of their illness or health condition” and (HC/HIT-1.2) “Increase the proportion of persons who report their health care provider always asked them to describe how they will follow the instructions (Healthy People, 2020).” The second tenet would indicate that they use the “teach-back” method. The teach-back method, or “show-me” method, confirms communication used by healthcare providers assuring a patient understands what is being explained as they are able to “teach-back” the information accurately (Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, 2015).

Given the gap in research available on the readability, understandability and cultural sensitivity of postnatal instruction, a pilot study led by SaferCare Texas’s Senior Fellow for Health Literacy aimed to identify needed improvement in postnatal education. The study passed the University of North Texas Health Science Center Regional and Texas Christian University (TCU) Institutional Review Boards. We hypothesized that improved health literacy and cultural sensitivity of postnatal instruction materials can improve communication, reduce care bias and optimize postnatal care potentially reducing maternal morbidity and mortality. SaferCare Texas collaborated with TCU Public Health Clinical nursing to analyze materials across hospital systems in rural and urban areas and available on the internet.

Methods

The materials were provided voluntarily by the hospitals and rural clinic or located online by the TCU nursing students. They were then assessed for current readability, understandability, actionability and cultural sensitivity of information regarding postnatal care using evidence-based tools. Tools used included the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) (AHRQ, 2018), Fry-based Readability (Readable, 2018) and National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) (USDHHS, 2018). The PEMAT is a systematic method to evaluate the understandability and actionability of patient education materials designed as a guide to help determine whether patients will be able to understand and act on information (AHRQ, 2018). The Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (2018), defines understandability and actionability.

“Understandability: Patient education materials are understandable when consumers of diverse backgrounds and varying levels of health literacy can process and explain key messages.”

“Actionability: Patient education materials are actionable when consumers of diverse backgrounds and varying levels of health literacy can identify what they can do based on the information presented.”

The Fry-based Readability Formula (2018) and its associated graph are often used in the healthcare industry to help provide a consensus of readability ensuring a wider portion of the population can understand and access health-related materials. The grade reading level (or reading difficulty level) is determined using the average number of sentences (y-axis) and syllables (x-axis) per hundred words (Readable, 2018). The National CLAS Standards are actions intended to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities through culturally and linguistically appropriate services inclusive of all populations (USDHHS, 2018). We developed a rubric (Appendix A) to assess CLAS standards since no assessment tool exists for applying these standards.

Using the aforementioned evidence-based tools, researchers assessed readability, understandability, actionability and cultural sensitivity of postnatal discharge materials and easily searchable materials on the Internet since the Internet is the primary source of information for postpartum low-income women (Guerra-Reyes, Christie, Prabhakar, Harris, & Siek, 2016).

Results

Analysis conducted on postnatal education materials from a variety of hospital systems across the North Texas region (n=5) and health organization websites (n=6) revealed 18% met PEMAT standards for understandability and actionability. We considered a score greater than 80% to be meeting of standards. None 0% met Fry-based standards for 5th grade Readability knowing that a large percentage of the at-risk population read at or below the 5th grade level. CLAS Standards were present 0%, developing 36% and not present 63% for cultural sensitivity (Table 1). Documents were scored for CLAS utilizing a developed rubric categorizing the various attributes of CLAS to determine if the material had CLAS Standards present, developing, or not present. The rural institution EMR generated material (n=1) met 0% for PEMAT, Readability and CLAS Standards.

Table 1:

Materials Review Scores for Common Health Literacy Measures Assessments calculated by authors using the defined parameters and resources below.

| Materials Reviewed | Readability Score |

PEMAT Score |

CLAS Score | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JPS Hospital PowerPoint-Postpartum | 6.7 | 38%-40% | Developing | John Peter Smith Hospital |

| Baylor Scott and White Hospital Postpartum Education | 8.8 | 38%-20% | Not Present | Baylor Scott and White Hospital computer-generated postpartum education |

| Baylor Scott and White Hospital Health Custom Communications | 7.2 | 81%-100% | Developing | A New Beginning Book: Dianne Moran, RN, LCCE, ICD and G. Byron Kallam, MD, FACOG |

| The Woman’s Hospital of Texas-Postpartum Discharge Guide | 10.4 | 46%-60% | Not Present | Postpartum Discharge Guide https://womanshospital.com/dotAsset/4ce953d1-ec8f-4f3f-bcf8-2f88cfa3978d.pdf |

| Save Your Life: Get Care for these POST-BIRTH Warning Signs – Online | 9.6 | 69% -50% | Developing | AWOHNN Postpartum Education Materials https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.awhonn.org/resource/resmgr/files/Post-Birth_Warning_signs_160.pdf |

| Preeclampsia Foundation – Online | 11.0 | 71%-40% | Developing | Postpartum Preeclampsia https://www.preeclampsia.org/stillatrisk |

| World Health Organization Maternal Sepsis – Online | 7.2 | 67%-20% | Not Present | Global Maternal and Neonatal Sepsis Initiative http://srhr.org/sepsis/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/WHO_Infographic-Maternal-sepsis-overview-EN-A4-WEB.pdf |

| Postpartum Hemorrhage widiHow by Carrie Noriega, MD Obstetrician & Gynecologist – Online | 8.1 | 80%-80% | Not Present | How to Know if It’s Postpartum Bleeding or a Period https://www.wikihow.com/Know-if-It%27s-Postpartum-Bleeding-or-a-Period |

| NIH Mental Health Postpartum Depression – Online | 9.8 | 64%-60% | Not Present | NIH Mental Health - Postpartum Depression Facts https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/postpartum-depression-facts/index.shtml |

| American Heart Association Peripartum Cardiomyopathy – Online | 9.1 | 67%-20% | Not Present | AHA Peripartum Cardiomyopathy https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/cardiomyopathy/what-is-cardiomyopathy-in-adults/peripartum-cardiomyopathy-ppcm |

| TCC AVS Instructions – Rural Clinic | 6.7 | 14% - 43% | Not Present | Tyler Circle of Care computer-generated postpartum education. |

14Readability Score: Documents were scored at https://readable.io/text/ and http://www.readabilityformulas.com/ by pasting full documents or portions of the more extensive education material. Satisfactory reading level was considered 5th grade or below.

13PEMAT Score: Documents were scored at https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/self-mgmt/pemat/pemat2.html. Good understandability and actionability was considered greater than 80%.

8CLAS Score: Documents were scored utilizing a developed rubric to state if the material had CLAS Standards present, developing, or not present.

In response to these findings, health literate postnatal materials (Appendix B) and an App titled, “What About Mom?)” <https://whataboutmom.herokuapp.com/index.html> were developed assimilating and simplifying information from the analysis of materials to increase health literacy and cultural sensitivity of postnatal education.

Input gathered from Community Health Workers, Obstetric Nurses, Master of Public Health students, Master of Health Administration students and new moms helped ensure the tools will assist new mothers in identifying postpartum warning signs, take appropriate action and help reduce maternal morbidity and death.

Discussion

The average American reads at about an 8th grade level. However, many sectors of the population read at the 5th grade level or below including 50% of minorities (Doak, Doak & Root, 1996). Most healthcare materials are written at 10th grade level or higher (Doak et al., 1996). As seen in this study, postnatal education materials still exceed reading levels today. The materials not only tested above standards to meet a large percentage of the population for readability, but also below standards for understandability, actionability and cultural competency making them unusable for new moms needing to learn about postpartum warning signs requiring emergent medical treatment. This study and subsequent tools will not solve the issue of high rates of maternal mortality in Texas and the U.S. However, the findings do indicate sustainable health systems patient safety strategies in communication are needed to improve usability of postpartum education especially in underserved communities and at-risk populations with potential low health literacy.

In addition, individualized care plans for postpartum moms with options based on their particular realities become paramount in their ability to identify potential warning signs and seeking medical help before it’s too late. Consideration of the possible social barriers that may impede new moms’ ability to apply information at home should be explored with them to collaborate in developing materials that provide guidance appropriate to their circumstance. This study provides tools that are health literate and available online for providers and moms. Future studies could explore these issues in more depth through one-on-one interviews and focus groups with postpartum moms to obtain their input and reality regarding these new tools. Providing understandable and actionable education at appropriate reading levels that is culturally sensitive can promote new moms’ adherence to clinical recommendations. and therefore, reduce morbidity and mortality.

Limitations to this study include a convenience sample of materials from within our provider networks and that are available online. However, this would mirror the way in which new moms would obtain information. Additionally, the development of a rubric for CLAS measurement was imperative to apply the standards. Each of the attributes of CLAS was vetted and categorized based on their needed presence to score a document having CLAS standards being present, developing or not present. Future studies could test the reliability and validity of the rubric possibly refining it further while facilitating operationalizing of these standards that have been adopted by Texas as well as 19 other states.

Conclusion

Education materials that women can read, understand, use and apply in their social context postnatally at home play an important role in patient safety reducing maternal morbidity and mortality. Facilities and practices that provide maternal services should identify areas to incorporate health literacy and cultural sensitivity into postnatal education to improve women’s understanding of abnormal postnatal symptoms and seeking of emergent care especially in high risk populations. To ensure that postpartum women who are at risk of a postnatal event receive immediate or emergent care, healthcare professionals and systems should consider the PEMAT guidelines for understandability and actionability of education, Fry-based Readability and National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services. Additionally, consistent teach-back should be the standard of care for women as defined in (HC/HIT-1.2) of Healthy People 2020, “Increase the proportion of persons who report their health care provider always asked them to describe how they will follow the instructions” to confirm understanding and actionability of postpartum instruction. This may be achieved by either revising their own education materials or by using the tools developed in this study to help empower women with the knowledge and self-efficacy to save their own lives.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54MD006882. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

TeresaWagner, DrPH, MS, CPH, RDN/LD, CHWI (teresa.wagner@unthsc.edu) is an Assistant Professor in the UNT Health Science Center, School of Health Professions and Clinical Executive for Health Literacy at Safer Care Texas, 3500 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth, Texas 76107. Dr. Wagner’s expertise is in health literacy. In her current role at SaferCare Texas, she has established a multi-stakeholder health literacy collaborative with DFW Hospital Council Foundation. Additionally, she has testified on health literacy legislation helping place health literacy in the Texas State Health Plan. In 2018, she received the Health Literacy Hero Award at the Texas Health Literacy Conference. Nationally, she speaks and facilitates trainings on health literacy. She serves on the Standing Committee on Finance & Legal for the International Health Literacy Association and co-chairs their Policy & Advocacy Special Interest Group.

Marie Stark, MSN, RNC-OB (marie.stark@tcu.edu) is an Assistant Professor of Professional Practice at Texas Christian University, Harris College of Nursing, 2800 S University Drive, Fort Worth, TX 76129. Marie’s areas of expertise are inpatient obstetric nursing, social and emotional literacy, and promoting partnerships in education. She currently teaches public health nursing clinical, and health assessment lab. In 2017, she was named one of Dallas/Fort Worth’s Great 100 Nurses. Her years of experience in labor and delivery, maternal/child health, and educating nursing students have allowed her to promote student application beyond the classroom. She has implemented multiple projects in underserved communities and developed partnerships with organizations aiming to decrease maternal and infant mortality in Texas.

Amy Raines Milenkov, DrPH (amy.raines-milenkov@unthsc.edu) is an Assistant Professor at UNT Health Science Center serving as both the Healthy Start Director and Building Bridges Director, 3500 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth, Texas 76107. For more than 15 years, Dr. Raines-Milenkov has dedicated her research and practice interests to maternal health, preconception health, birth outcomes and system and social contributors to adverse outcomes. She is a member of UNTHSC’s ForHer Health Institute, focused on improving women’s health through excellence in clinical care, research and education. She serves on the Texas Department of State Health Services Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force force charged with studying and reviewing pregnancy-related deaths and trends in severe maternal morbidity. She also serves as chair of the Tarrant County Infant Health Network, a member of the Texas Refugee and Immigrant Women’s Association, and as an Expert Panel Member of the Texas Department of State Health Services’ Healthy Texas Babies Initiative.

Appendix

Appendix A

CLAS Standard Rubric

Respect the whole individual and Respond to the individual’s health needs and preferences.

By tailoring services to an individual's culture and language preferences, health professionals can help bring about positive health outcomes for diverse populations.

The provision of health services that are respectful of and responsive to the health beliefs, practices, and needs of diverse patients can help close the gap in health outcomes.

| Present | Developing | Not Present |

|---|---|---|

| Provide understandable self-care Information responsive to: | ||

Health Literacy:

|

Health Literacy:

Culture: Sociological characteristics

Preferred language:

|

Health Literacy:

Culture: Sociological characteristics

Preferred language:

|

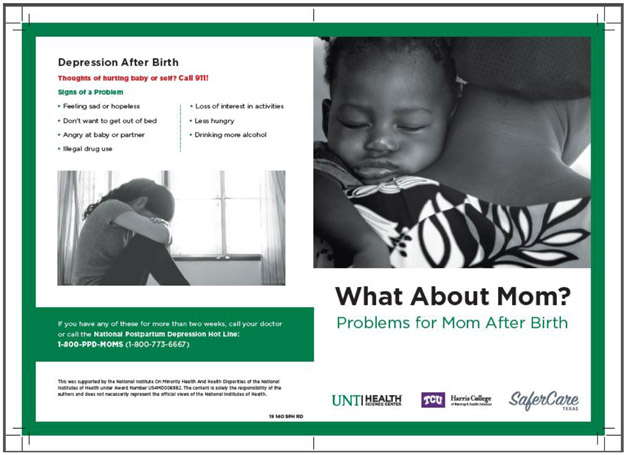

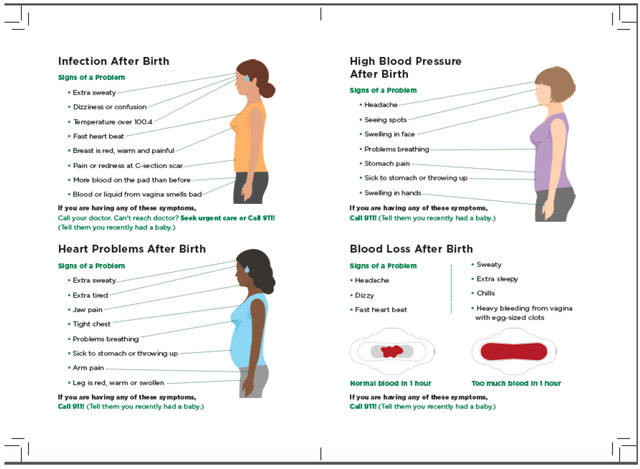

Appendix B

Cover of Brochure

Inside of Brochure

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ). (2015). Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthlittoolkit2-tool5.html [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ). (2018). Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT). https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/self-mgmt/pemat/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Atrash HK (2011). Parents’ Death and its Implications for Child Survival. Revista brasileira de crescimento e desenvolvimento humano, 21(3), 759–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeva S, Saxton D, Ruggiero K, Kormondy M, Hollier L, Hellerstedt J, Hall M, & Archer N (2018). Identifying Maternal Deaths in Texas Using an Enhanced Method, 2012. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), 762–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html [Google Scholar]

- Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, & Coleman EA (2009). Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Frontiers in Health Services Management, 25, 11–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doak CC, Doak LG, & Root JH (1996). The literacy problem In Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co. [Google Scholar]

- GBD Maternal Mortality Collaborators. (2015). Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Retrieved from http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(16)31470-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Reyes L, Christie VM, Prabhakar A, Harris AL, & Siek KA (2016). Postpartum Health Information Seeking Using Mobile Phones: Experiences of Low-Income Mothers. Maternal and child health journal, 20(Suppl 1), 13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2185-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People 2020. Health Communication and Health Information Technology. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/health-communication-and-health-information-technology/objectives [Google Scholar]

- Heaman MI, Sword W, Elliott L, Moffatt M, Helewa ME, & Morris H et al. (2015). Barriers and facilitators related to use of prenatal care by inner-city women: perceptions of health care providers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J (2012). Maternal Mortality in the United States - Why Is It Important and What Are We Doing About It? Seminars in Perinatology, 36(1), 14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman LA, et al. (2017). Understanding Perspectives of African American Medicaid-Insured Women on the Process of Perinatal Care: An Opportunity for Systems Improvement. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21, 81–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Readability Score. (2018). Retrieved from https://readable.io/text/ [Google Scholar]

- Suplee PD, Bingham D, & Kleppel L (2017). Nurses’ knowledge and teaching of possible postpartum complications. The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Texas Department of State Health Services (TXDSHS). (2016). Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force and Department of State Health Services Joint Biennial Report. file:///Users/teresawagner/Downloads/2016BiennialReport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (USDHHS). (2018). National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS). https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/standards [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Maternal Mortality. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality [Google Scholar]

- Young A (2019). Deadly Deliveries. U.S.A. Today Investigative Report. Retrieved from https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/investigations/deadly-deliveries/2018/07/26/maternal-mortality-rates-preeclampsia-postpartum-hemorrhage-safety/546889002/#iwasreallyscared [Google Scholar]