Abstract

Abstract

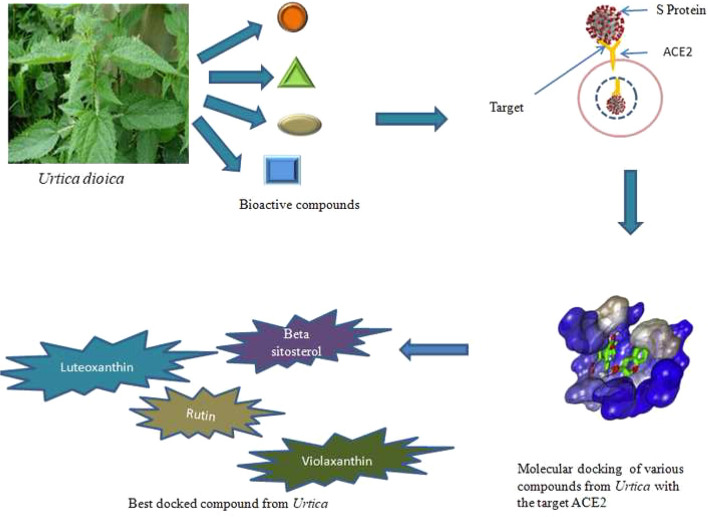

The pandemic outbreak of coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is rapidly spreading across the globe, so the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents is urgently needed. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), a human receptor that facilitates entry of SARS-CoV-2, serves as a prominent target for drug discovery. In the present study, we have applied the bioinformatics approach for screening of a series of bioactive chemical compounds from Himalayan stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) as potent inhibitors of ACE-2 receptor (PDB ID: 1R4L). The molecular docking was applied to dock a set of representative compounds within the active site region of target receptor protein using 0.8 version of the PyRx virtual screen tool and analyzed by using discovery studio visualizer. Based on the highest binding affinity, 23 compounds were shortlisted as a lead molecule using molecular docking analysis. Among them, β-sitosterol was found with the highest binding affinity − 12.2 kcal/mol and stable interactions with the amino acid residues present on the active site of the ACE-2 receptor. Similarly, luteoxanthin and violaxanthin followed by rutin also displayed stronger binding efficiency. We propose these compounds as potential lead candidates for the development of target-specific therapeutic drugs against COVID-19.

Graphic abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11030-020-10159-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Urtica dioica, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), Molecular docking

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the group of RNA viruses. Coronavirus is classified as alpha and beta (origin: bats and rodents), gamma, and delta (origin: avian species) [1]. In around 2002, a beta-coronavirus crossed the species barrier and moved from bats to a mammalian host and then to humans causing a SARS outbreak [2]. Another beta coronavirus involved in causing the solemn malady like Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) began in 2012 [3]. The coronavirus we have been dealing with lately, liable for the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, also belongs to the group of beta-coronavirus [4]. Full-length sequencing of the genome of this virus suggests its closeness to the strains found in bats, thus proposing its origin from the bats [2]. Its resemblance to the SARS-CoV (SARS-coronavirus) has given it the name, SARS-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV 2) [5]. The S protein (Spike protein) of SARS-CoV binds to the cell surface receptors. SARS-CoV-2 a (+) single-stranded RNA virus fasten similar receptor as SARS-CoV, i.e., angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) to infect the host [4], which was not the case of MERS-CoV S protein which targets DPP4 [6, 7], not ACE-2. ACE-2, a molecule present mostly on the surface of blood vessels, and epithelium of the intestine and lungs are imperative in controlling immune reaction and flow of blood [8]. As per the record of November 10, the total numbers of confirmed cases are 51,385,928, while the casualties caused are about 1,271,000 in 215 nations. Presently, the USA, India, Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Peru, and Mexico are the most affected countries.

The counts of infection and casualty caused make it clear that this is a dreadful virus that is in a great need to be contemplated and subsequently cured. It will take more than a year to develop an effective vaccine [9]. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop effective drugs against this disease. The progress of compelling medicines is not easy and will take longer than assumed, in turn impeding the management of this pandemic issue. Therefore, to get over this, a rapid technique that can open paths for the development of some effective drugs, i.e., molecular docking, has been used in our study. So far several natural compounds have been evaluated for their anti-SARS and anti-MERS activity; moreover, lately many investigators have been working on the repurposing of these natural products to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection [10–12], but none of these compounds have been tested for phase III clinical trials. In this study, we have focused on various compounds like beta-sitosterol, rutin, luteoxanthin, violaxanthin, lutein epoxide, etc., of Urtica dioica as they have already been reported to have potential anticancer and antiviral activities [13, 14]. Further, beta-sitosterol, luteolin, quercetin, kaempferol also demonstrated activity against various types of coronaviruses specifically SARS-CoV [14]. Moreover, Urtica dioica grows abundantly in Uttarakhand Himalaya as a fodder and medicinal plant, so to start with, virtual scanning of various phytochemicals present in Urtica spp. was done which would control SARS-CoV-2 in the host cell. Our study involved the ACE-2 receptor as the target for these phytochemicals. ACE-2 is the receptor for S protein of coronavirus which is reported to be generally present in the lungs, thus making lungs the most affected organ in SARS-CoV-2 infection [15, 16]. So the main objective of this study is to identify natural anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents from Urtica dioica targeting the ACE-2 receptor.

Materials and methods

Building the phytochemical library

Various servers were searched (PubMed, Carrot2, and DLAD4U) to commence studies in different research papers, and about 41 compounds from the plant Urtica dioica were collected. Urtica was undertaken in this study due to its various therapeutic role against viral infections [13, 14, 17, 18].

Protein selection and preparation

ACE-2 the protein which has formed the major target for this virus in humans was retrieved from the database PDB (URL: https://www.rcsb.org) with PDB ID: 1R4L. Also, the selection of target protein for docking study is based on their X-ray diffraction. The selected protein should not have protein break in entire 3D conformation, and to meet requirements of docking analysis, protein should be in the form of PDB formats. X-ray crystallographic structure of 1R4L angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) was prepared for molecular docking in such a way that all heteroatoms (water, ions, etc.) were removed. By using the chimera tool, protein binding sites of the chain are selected and others are removed.

Ligand preparation

Pubchem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was used to retrieve 2D structures of the phytochemicals in SDF format, and further using Open Babel (software), these compounds were converted to PDB format. The reference molecule used in the entire docking analysis was chloroquine phosphate (brand name Resochin) with Pubchem CID-64927 which were retrieved from Pubchem. Chloroquine phosphate (a commercial drug) is used as a control drug in this study which is a known inhibitor of ACE-2.

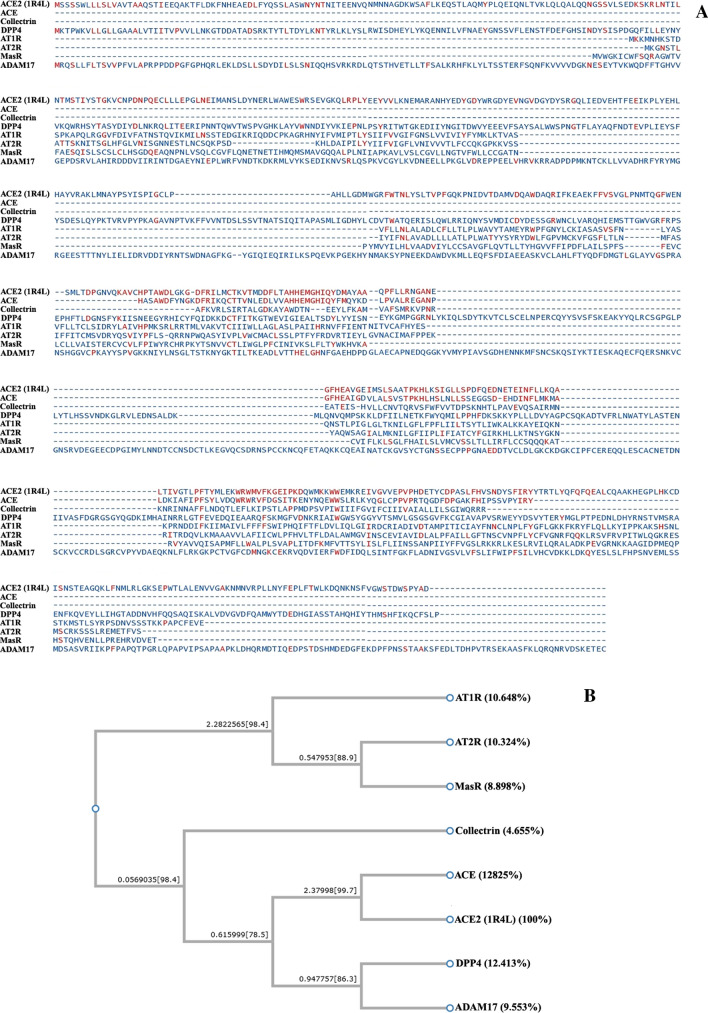

Phylogeny and homology modeling

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was done to check the similarities between the molecules present in the branch of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) occurring in the lungs. The amino acid sequence of the target ACE-2 (PDB ID:1R4L) along with the active site of ACE-2 (AAH36375.1), the mature chain of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4; sp|P27487.2), ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM17; sp|P78536.1) and Mas receptor (MasR; sp|P35410.1), and also amino acid sequence of the protein angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R; NP_114038.4), angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2R; NP_000677.2) and collectrin (AAG09466) were retrieved from the database NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) in FASTA format, and later, these sequences were scanned for their similarities using Clustal W. Furthermore, a phylogenetic tree was developed using the aligned sequences.

Molecular docking

An in silico approach for ligand and receptor docking analysis was employed to examine structural complexes of the 1R4L (target protein) with Urtica dioica compounds (ligand molecule) to emphasize structural conformation of this protein target specificity. In the present investigation, we use PyRx virtual screening tool which uses both Vina and Auto Dock 4.2 with the Lamarckian genetic algorithm as scoring function and contributes higher docking accuracy [19, 20].

The target protein was defined as the total number of atoms of 5218; the number of residues is 655 with unique five chains. The chemical structure of macromolecule was determined by X-ray crystallography with a resolution of 3.00 Å. We continue the preparation of the target by eliminating the bound ligands and water molecules through the UCSF Chimera tool. Also, we remove all chains except Chain A as it shows only a ligand-binding site chain. Then, we introduced it into the PyRx tool by remarked as macromolecule in PyRx workflow. In this method, the protein and ligand molecules were converted to their proper readable file format (pdbqt) using auto dock tools. All docking studies were performed as blind docking which was set in the grid box and encompassing all possible ligand–receptor complex, and dimensions were X = 39.021, Y = 4.078, and Z = 22.898 to dock all the ligands where 8 maximum exhaustiveness was calculated for each ligand. All other parameters of software were kept as default, and all bonds contained in ligand were allowed to rotate freely, considering receptor as rigid. The final visualization of the docked structure was performed using Discovery Studio Visualizer 3.0. Before testing the potentiality of the Urtica dioica compounds against 1R4L, a commercial ACE-2 inhibitor chloroquine phosphate was docked against 1R4L for comparative study [21].

Results

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic relationship of ACE-2 (1R4L) and various enzymes involved in the renin–angiotensin system (ACE, ADAM17, Mas-R, AT1R, and AT2R) along with a few other important homologs of ACE-2 (collectrin and DPP4) was evaluated (Fig. 1). The phylogeny indicated that ACE-2 is only 12.825% similar to ACE-2, 9.553% to ADAM17, 10.648% to AT1R, 10.324% to AT2R, 8.898% to MASR, 4.655% to collectrin, and 12.413% to DPP4. Such a low level of similarity confirms that ACE-2 is distantly related to these enzymes, further strengthening our hypothesis to evaluate the ACE-2 receptor as a potential drug target.

Fig. 1.

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic relationship among ACE-2 (PDB ID:1R4L) and other important enzymes involved in RAS system. a The protein sequences were aligned by the ClustalW 2.1 algorithm using the Network Protein Sequence Analysis (NPS@) online tool, and aligned sequences were graphically viewed by the Easy Sequencing in PostScript (ESPript) program. b Phylogenetic analysis was conducted on ClustalW 2.1-aligned sequences using the Poisson model method of MEGA v5.2 by the NJ method and bootstrap analysis (1000 repeats). The sequence of 1R4L is distantly related to other enzymes involved in the RAS system

Molecular docking

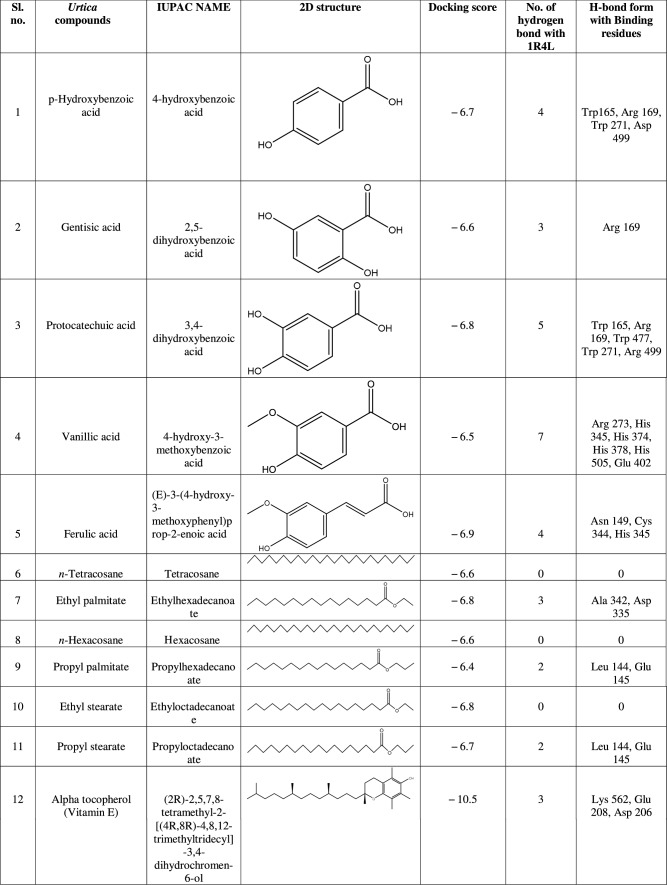

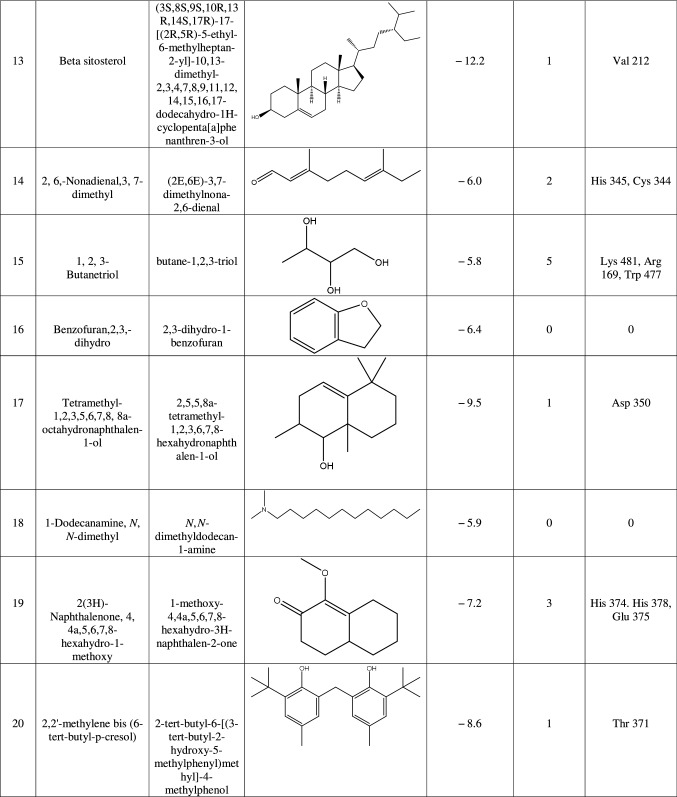

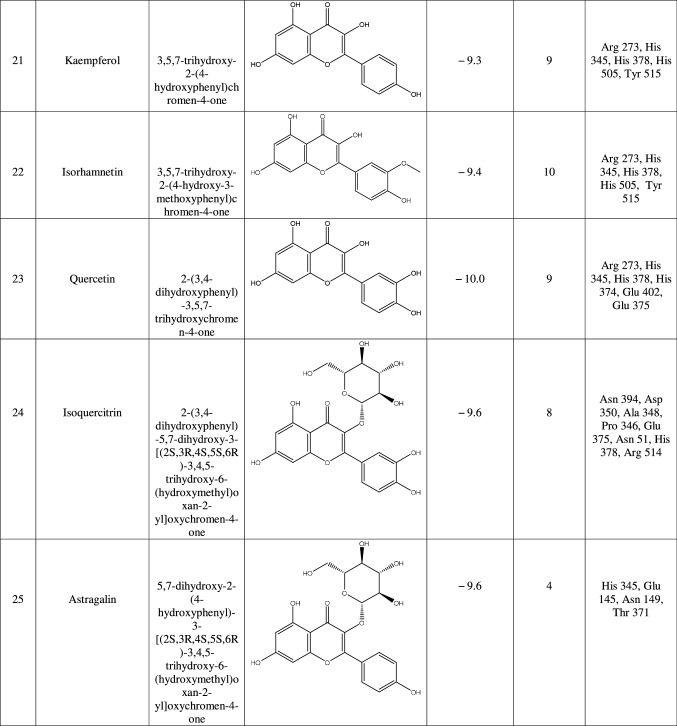

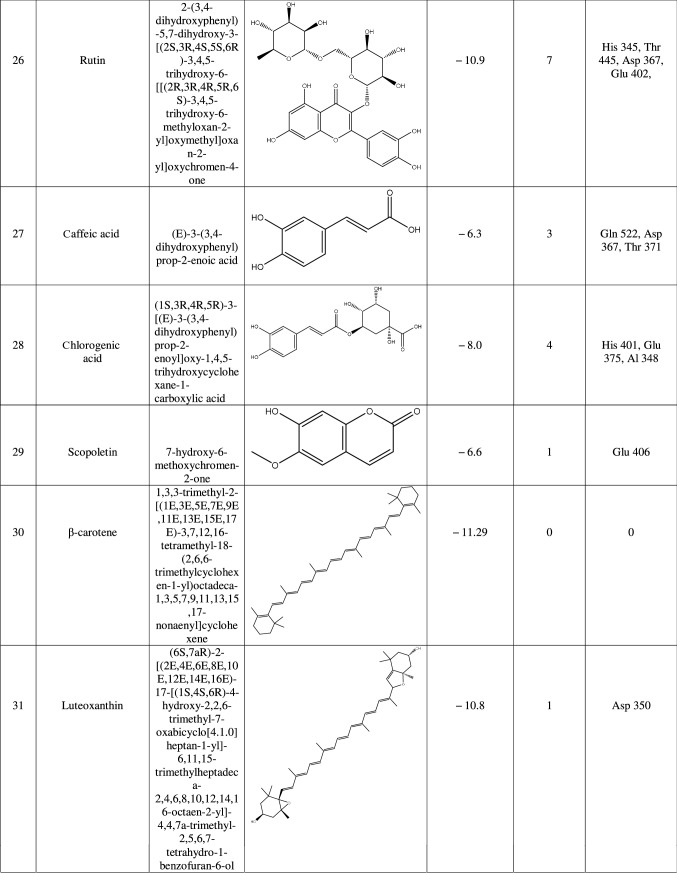

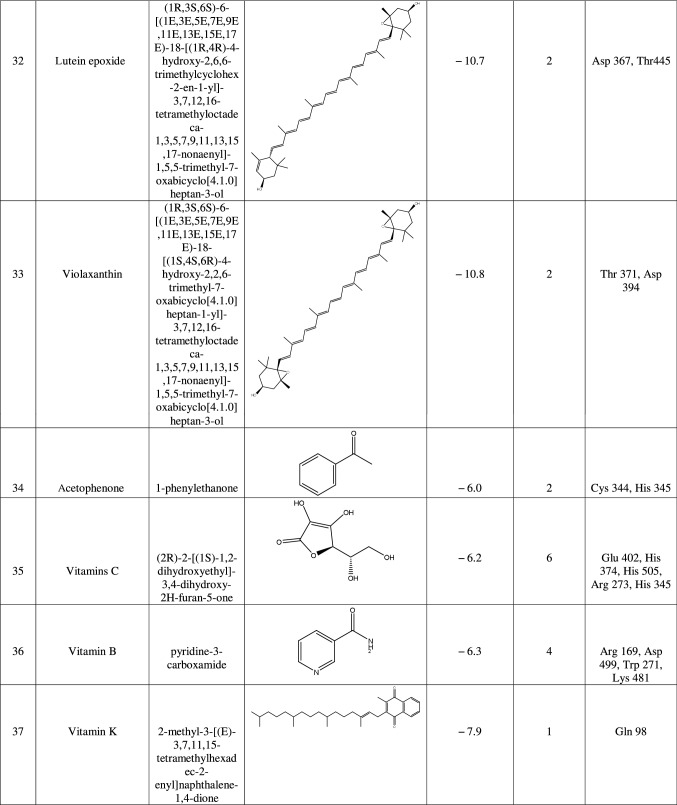

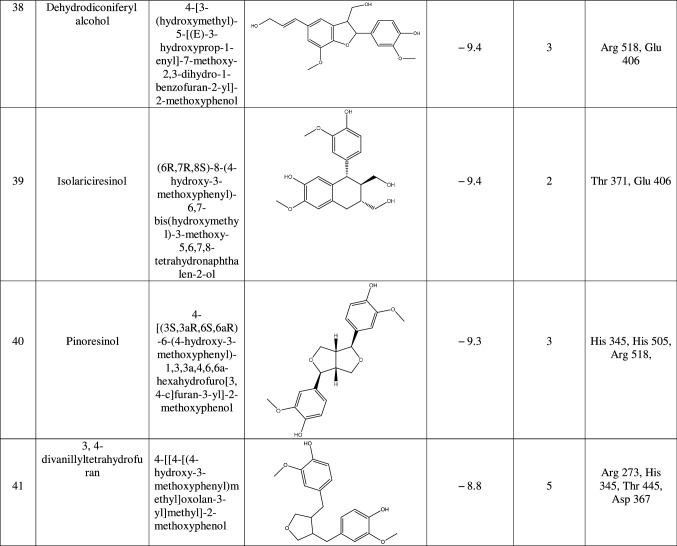

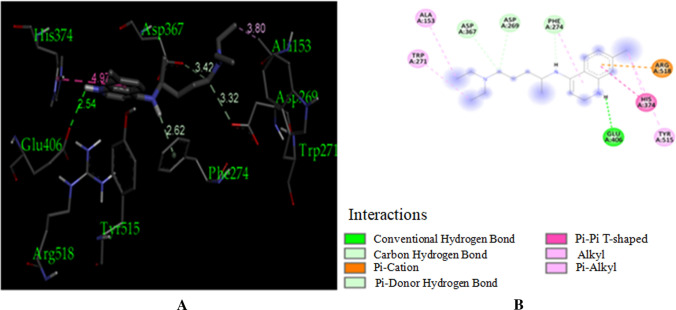

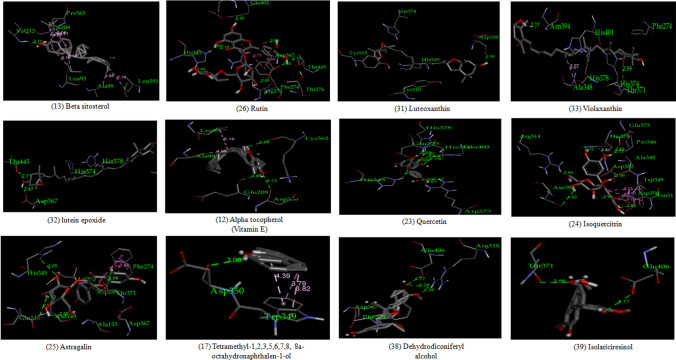

ACE-2 is the best target for inhibiting the 2019-n CoV, due to the higher affinity of spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-Cov-2. Spike (S) glycoprotein plays the most important role in viral attachment, fusion, and entry into the host cell. CoV entry into the host immune system is mediated by transmembrane spike glycoprotein which forms homotrimers protruding from the viral surface and gives CoVs a crown-like appearance by forming spikes on their surface. S protein binds to a membrane receptor on the host cells, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2; EC 3.4.17.23) mediating the viral and cellular membrane fusion, which represents the critical initial stage of the infection [22, 23]. Molecular docking studies were carried out between receptor proteins (ACE-2) and its inhibitors (Urtica dioica compounds). Table 1 consists of all the compounds with their IUPAC names, structures of ligands, docking scores, and necessary H-bond formation with possible active residues by ligands with targets required for the inhibition of receptor of COVID-19. After successfully docking these compounds into target ACE-2, the result displays various modes of ligand–receptor interactions are generated with a particular docking score. The binding mode with the least binding energy is regarded as the best mode of binding as it is most stable for the ligand. Most of the compounds show their inhibitory action by representing lower binding energy score (higher docking scores) compared with the binding energy of chloroquine phosphate (− 6.8 kcal/mol), the standard and commercial ACE-2 inhibitor. The co-ordination center and size of the presence of the active site in targeted protein (Chain A of 1R4l) are generated from the PyRx virtual screening tool. Before conducting the virtual screening, molecular docking protocol was validated by docking the reference ligand chloroquine phosphate into binding pocket obtained from the target protein ACE-2. The docked ligand was superimposed to compare with experimental ligands. Generally, the RMSD value is used to validate the docking studies. The RMSD value between the experimental ligand and docked ligand (chloroquine phosphate) was 0.0 angstrom, which was perfectly acceptable. The result displays that the docked reference molecule chloroquine phosphate exhibited well-established hydrogen bonds with an amino acid residue in receptor active pocket shown in Fig. 2. The figure also indicates the formation of one conventional hydrogen bond with Glu 406 (2.54 Å), one Pi–Pi bond with His 374 (4.97 Å), three carbon–hydrogen bonds formed with Asp 367 (3.41 Å), Asp 269 (3.32 Å), Phe274 (2.62 Å), three Pi-Alkyl bond with Ala 153 (3.80 Å), Trp271 (5.05 Å), Tyr 515 and one Pi-cation bond with Arg 518 (4.31 Å) has been observed. The virtual screening of all Urtica dioica compounds (n = 41) was performed by the docking approach in the active sites of a target protein using the PyRx tool. From molecular docking analysis, a total of 23 compounds were screened which showed binding energy ranging from − 12.2 to − 6.8 kcal Mol−1 against Covid-19 receptor ACE-2, and out of these 23 compounds, 12 best-docked compounds (ranging from − 12.2 to − 9.4) with their ligand–receptor 3D interaction images are shown in Fig. 3 and compounds showing binding energy less than − 9.4 kcal Mol−1 are illustrated in supplementary Fig. S1 to S3. The binding energy of the reference molecule chloroquine phosphate was − 6.8 kcal Mol−1. All these screened leads showed lower and significant binding energy and novel hydrogen bonding interactions with active residues of target receptors in comparison with the reference molecule. Thus, the docking studies suggest that screened compounds may have the same mechanism of action as the reference molecule. The 3D interaction images of 12 compounds with target ACE-2 in supplementary Fig. S2 reveal that binding in the pocket of chain A with the affinity ranges from − 6.7 to − 5.8 kcal Mol−1. In comparison with the reference molecule, it shows lower docking scores (higher binding energy), but these ligands have shown stronger interactions also with the target protein and may be considered as good inhibiter of ACE-2. Furthermore, in supplementary Fig. S3, the docking of ACE-2 target with Urtica dioica compounds using docking procedure revealed that compound 6, 8, 16, and 30 were bounded by hydrophobic pockets containing amino acid residues, whereas compounds 10 and 18 were involved with hydrophobic and electrostatic pockets containing residues, though these compounds exhibited lower binding affinity to the target protein. These compounds do not exhibit any stronger interactions like H-bond with the target. Therefore, these were surprisingly low as compared to the reference molecule, indicating docking programs often failed to find out the correct binding mode.

Table 1.

1R4L active residues involved in docking interactions with the inhibitors and their dock scores

Fig. 2.

Visuals of docking interactions of chloroquine phosphate ligand molecule. a 3D interaction poses of the ligand with 1R4L. b 2D interactions of the ligand with 1R4L

Fig. 3.

Docking interactions showing novel binding interactions with the highest docking score (binding energy from − 12.2 to − 9.4 kcal/mol)

Discussion

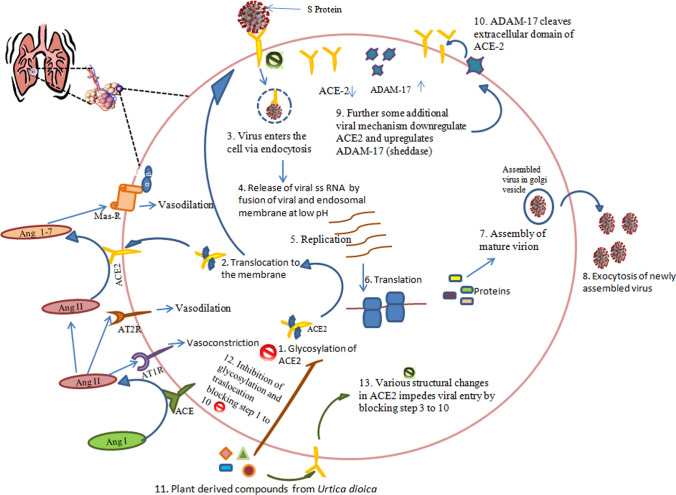

The intricacy of SARS-CoV-2 has doomed the world right now owing to the lack of availability of any effective drug or vaccine; however, some synthetic antiviral drugs such as lopinavir/ritonavir [24, 25] and remdesivir [25] as well as other antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine [25] currently used to treat SARS-CoV-2 patients have various side effects, and therefore, natural compounds are in a great need to be explored. Natural compounds can boost immunity [26, 27] and cure a range of viral diseases. One of the most widely distributed plants with various medicinal properties is Urtica dioica. This particular plant has been noteworthy because of its antiviral, antioxidant, antiulcer, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, immune-modulatory, anti-colitis, anti-diabetic, and anti-cancerous properties [13, 14, 18], and additionally compounds from Urtica have also been reported to impede nidovirales infection [14, 18]. In this study, we have explored Urtica, which exhibits a range of bioactive compounds that can target ACE-2, an important enzyme of the RAS system, and a decisive protein for the internalization of SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, we have evaluated the similarity index of ACE2 with ACE, ADAM17, Mas-R, AT1R, AT2R, collectrin and, DPP4. We have selected these proteins for MSA because ACE, ADAM17, Mas-R, AT1R, and AT2R play an important role in the RAS system. In addition, collectrin, a carboxypeptidase present in the kidney, is an important homolog of the ACE2 protein (a carboxypeptidase itself) [28]. Furthermore DPP4, is an important receptor for MERS-CoV [6, 7]. Interestingly, we have observed that ACE-2 is quite distantly related to these proteins, and this finding further strengthens our hypothesis to evaluate ACE 2 as a potential drug target. Most crucial molecules of the RAS system including ACE-2 are present in the lungs; therefore, damage to the lungs is one of the major consequences of this viral infection [29]. ACE-2, in the lung tissue, converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II, which can either bind to AT1R or AT2R where it induces vasoconstriction (increase in the blood pressure) or vasodilation (decrease in the blood pressure), respectively [29]. ACE-2 another enzyme present in the lung tissue acts on angiotensin II and converts it into Ang1-7 which in turn binds to the Mas-R leading to vasodilation, consequently affecting the blood pressure [29]. ACE-2 comes to the surface only when glycosylated; during SARS-CoV-2 infection S (spike) protein of the virus binds to the ACE-2 receptors which result in the internalization of the virus; further, the viral genome is released into the cytosol where its replication and translation takes place to assemble newly formed virion which is later exocytosed (Fig. 4). As the RAS system consists of various enzymes, therefore, to get a clear vision that ACE-2 will make a good target for the natural compounds, we have executed its homology with the enzymes/proteins from the RAS system and some other homologs of ACE-2 and found that it is distantly related to all the other 7 enzymes. In this study, compounds such as beta-sitosterol (compound 13) exhibited the best-docked score (− 12.2 kcal Mol−1) with ACE-2, followed by rutin (− 10.9), luteoxanthin (− 10.8), violaxanthin (− 10.8), lutein epoxide (− 10.7), and alpha-tocopherol (− 10.5) which are tentative to work by two possible pathways; it can either inhibit the glycosylation of the ACE-2 receptors, thus restricting its translocation to the surface, to which the S protein of the coronavirus would otherwise bind and would be internalized, and binding of these compounds may also cause some structural changes in the receptor ACE-2, thus disabling its ability to bind with the S protein and restricting the viral entry. Hence, these compounds can be helpful in the inhibition of viral entry, consequently preventing the pathogenesis. Further these compounds can not only inhibit the entry of virus but could also affect the activity of other enzyme involved in the glycosylation of the receptor such as the oligosaccharyltransferase that are quite essential particularly for the translocation of ACE2 receptor to the surface [16]. So it may be hypothesized that oligosaccharyltransferase could also be a putative target for these natural compounds from Urtica.

Fig. 4.

ACE-2 Role in SARS-CoV-2 Infection: angiotensin I is converted to angiotensin II by the action of ACE. Angiotensin II can either bind to AT1R or AT2R where it induces vasoconstriction (increase in the blood pressure) or vasodilation (decrease in the blood pressure), respectively. ACE-2 acts on angiotensin II and converts it into Ang1-7 which in turn binds to the Mas-R leading to vasodilation. ACE-2 comes to the surface only when glycosylated, during SARS-CoV-2 infection S (spike) protein of the virus binds to the ACE-2 receptors which result in the internalization of the virus further the viral genome is released into the cytosol where its replication and translation takes place to assemble newly formed virion which is later exocytosed. The phytochemicals here are thought to act in two ways by inhibiting the glycosylation of ACE-2 (step 1–10 are blocked) or by making structural changes in ACE-2 (step 3–10 blocked)

Results generated from molecular docking of various compounds of Urtica with the target ACE-2 gave us some compounds with an overwhelming response. These compounds are thought to inhibit ACE-2 by causing various structural changes or by affecting glycosylation (without glycosylation ACE-2 will not come to the surface), thus impeding the path for the virus to enter the host cell [30, 31]. In silico approaches have been established as an important part of various drug discovery programs, from leading finds to its optimization; methodologies such as a ligand or targeted based computational screening procedures are broadly employed in many drug discovery studies [32–34]. Docking predicts the mode of interaction between target receptor protein and small ligand for established binding sites. Binding energy suggests the affinity of a specific ligand and strength by which a compound interacts with and binds to the pocket of a target protein. A compound with lower binding energy is preferred as a possible drug candidate. Currently, SARS-CoV-2 has become a prominent challenge for every researcher across the globe. The outbreak of this virus is spreading worldwide and causing several deaths. As we all know that no chemical vaccines are available for the treatment of the disease, we can use natural compounds that can help to stop the dissemination of coronavirus. SARS-CoV uses ACE-2 as a surface receptor that mediates the process of infection and transmission. In our study, we have applied a computational approach of drug repurposing in order to identify a specific therapeutic agent against the COVID-19 receptor. Targeting ACE-2 protein can be efficient and leads to such changing of structural conformation which will not permit entering this virus inside the host cells. Therefore, about 41 compounds from Urtica were virtually scanned using PyRx virtual tool to build a phytochemical library. Later, these compounds were docked with the enzyme ACE-2. Out of 41 screened leads, only 23 compounds were selected based on their binding affinity and stronger interaction with the ACE 2 target. By in silico approach, we have observed that beta-sitosterol (compound 13) exhibited the best-docked score (-12.2 kcal/mol) with ACE-2 protein. The native ligand attached in ACE-2 protein is showing its inhibitory action by forming one hydrogen bond with Val 212 (2.10 Å), and leu95, Val 209, Pro 565, Leu391, Ala 99 residues appear in a mostly hydrophobic binding pocket. In this study, we have the first time reported various compounds from Urtica dioica for their anti-SARS activity, specifically targeting the ACE-2 receptor. We have observed that many compounds from the plant Urtica have shown better results than the reference drug molecule chloroquine phosphate. Thus, compounds from this particular plant can surely be evaluated for in vitro study and clinical trial.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Zoology, Kumaun University SSJ Campus, Almora (Uttarakhand), India, and Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology, Raipur (Chhattisgarh), India, for providing the facility for this work. This work is supported by DST-FIST Grant SR/FST/LS-I/2018/131 to the Department of Zoology.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shobha Upreti and Jyoti Sankar Prusty have contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Awanish Kumar, Email: drawanishkr@gmail.com.

Mukesh Samant, Email: mukeshsamant@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai ACK, Zhou J, Liu W, Bi Y, Gao GF. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(6):490–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omar S, Bouziane I, Bouslama Z, Djemel A (2020) In-silico identification of potent inhibitors of COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) from Natural Products: Quercetin, Hispidulin, and Cirsimaritin Exhibited Better Potential Inhibition than Hydroxy-Chloroquine Against COVID-19 Main Protease Active Site and ACE2

- 3.McIntosh K, Perlman S (2015) Coronaviruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS). Mandell Douglas Bennett’s Princ Pract Infect Dis 1928

- 4.Liu Z, Xiao X, Wei X, Li J, Yang J, Tan H, Zhu J, Zhang Q, Wu J, Liu L. Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):595–601. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson B (2020) Computers and viral diseases. Preliminary bioinformatics studies on the design of a synthetic vaccine and a preventative peptidomimetic antagonist against the SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV, COVID-19) coronavirus. In: Computers in biology and medicine, pp 103670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Raj VS, Smits SL, Provacia LB, van den Brand JMA, Wiersma L, Ouwendijk WJD, Bestebroer TM, Spronken MI, van Amerongen G, Rottier PJM. Adenosine deaminase acts as a natural antagonist for dipeptidyl peptidase 4-mediated entry of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2014;88(3):1834–1838. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02935-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia S, Liu Q, Wang Q, Sun Z, Su S, Du L, Ying T, Lu L, Jiang S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) entry inhibitors targeting spike protein. Virus Res. 2014;194:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Diego ML, Nieto-Torres JL, Jimenez-Guardeño JM, Regla-Nava JA, Castaño-Rodriguez C, Fernandez-Delgado R, Usera F, Enjuanes L. Coronavirus virulence genes with main focus on SARS-CoV envelope gene. Virus Res. 2014;194:124–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandey SC, Pande V, Sati D, Upreti S, Samant M. Vaccination strategies to combat novel corona virus SARS-CoV-2. Life Sci. 2020;256:117956. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khare P, Sahu U, Pandey SC, Samant M. Current approaches for target-specific drug discovery using natural compounds against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Life Sci. 2020;290:117956. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koulgi S, Jani V, Uppuladinne M, Sonavane U, Nath AK, Darbari H, Joshi R (2020) Drug repurposing studies targeting SARS-CoV-2: an ensemble docking approach on drug target 3C-like protease (3CLpro). J Biomol Struct Dyn 1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Patel CN, Kumar SP, Pandya HA, Rawal RM (2020) Identification of potential inhibitors of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy calculation. Mol Divers 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Joshi BC, Mukhija M, Kalia AN. Pharmacognostical review of Urtica dioica L. Int J Green Pharm. 2014;8(4):201–209. doi: 10.4103/0973-8258.142669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orhan IE, Senol Deniz FS. Natural products as potential leads against coronaviruses: could they be encouraging structural models against SARS-CoV-2? Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2020;10(4):171–186. doi: 10.1007/s13659-020-00250-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020;94(7):1–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner FJ, Smith AI, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2: a molecular and cellular perspective. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(21):2704–2713. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asgarpanah J, Mohajerani R. Phytochemistry and pharmacologic properties of Urtica dioica L. J Med Plants Res. 2012;6(46):5714–5719. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumaki Y, Wandersee MK, Smith AJ, Zhou Y, Simmons G, Nelson NM, Bailey KW, Vest ZG, Li JKK, Chan PK-S. Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in a lethal SARS-CoV BALB/c mouse model by stinging nettle lectin, Urtica dioica agglutinin. Antivir Res. 2011;90(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Tannak NF, Novotny L, Alhunayan A. Remdesivir-bringing hope for COVID-19 treatment. Sci Pharm. 2020;88(2):29. doi: 10.3390/scipharm88020029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M, Wang T, Zhou Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Li J. Potential Role of ACE2 in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Prevention and Management. J Transl Int Med. 2020;8(1):9–19. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2020-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tortorici MA, Veesler D. Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv Virus Res. 2019;105:93–116. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arabi YM, Alothman A, Balkhy HH, Al-Dawood A, AlJohani S, Al Harbi S, Kojan S, Al Jeraisy M, Deeb AM, Assiri AM, Al-Hameed F, AlSaedi A, Mandourah Y, Almekhlafi GA, Sherbeeni NM, Elzein FE, Memon J, Taha Y, Almotairi A, Maghrabi KA, Qushmaq I, Al Bshabshe A, Kharaba A, Shalhoub S, Jose J, Fowler RA, Hayden FG, Hussein MA. Treatment of middle east respiratory syndrome with a combination of lopinavir-ritonavir and interferon-beta1b (MIRACLE trial): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):81. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bimonte S, Crispo A, Amore A, Celentano E, Cuomo A, Cascella M. Potential antiviral drugs for SARS-Cov-2 treatment: preclinical findings and ongoing clinical research. Vivo. 2020;34(3 suppl):1597–1602. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyo E, Uda N, Kasuga S, Itakura Y. Immunomodulatory effects of aged garlic extract. J Nutr. 2001;131(3s):1075S–1079S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.1075S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sultan MT, Butt MS, Qayyum MM, Suleria HA. Immunity: plants as effective mediators. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2014;54(10):1298–1308. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.633249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Wada J, Hida K, Tsuchiyama Y, Hiragushi K, Shikata K, Wang H, Lin S, Kanwar YS, Makino H. Collectrin, a collecting duct-specific transmembrane glycoprotein, is a novel homolog of ACE2 and is developmentally regulated in embryonic kidneys. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(20):17132–17139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Ardes D, Boccatonda A, Rossi I, Guagnano MT, Santilli F, Cipollone F, Bucci M. COVID-19 and RAS: unravelling an unclear relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):3003. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GroßS D, Jahn C, Cushman S, Bär C, Thum T. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2-dependent implications on the cardiovascular system: from basic science to clinical implications. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;144:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J-J, Shen X, Yan Y-M, Yan W, Cheng Y-X (2020) Discovery of anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents from commercially available flavor via docking screening. 10.31219/osf.io/vjch2

- 32.Bajorath J. Integration of virtual and high-throughput screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(11):882–894. doi: 10.1038/nrd941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gohlke H, Klebe G. Approaches to the description and prediction of the binding affinity of small-molecule ligands to macromolecular receptors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(15):2644–2676. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020802)41:15<2644::AID-ANIE2644>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langer T, Hoffmann RD. Virtual screening: an effective tool for lead structure discovery? Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7(7):509–527. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.