ABSTRACT

DCAF13 is firstly identified as a substrate receptor of CUL4-DDB1 E3 ligase complex. This study disclosed that DCAF13 acted as a novel RNA binding protein (RBP) that contributed to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) metastasis. Clinical data obtained from TCGA and our collection showed that DCAF13 was closely correlated with poor clinicopathological characteristics and overall survival, which indicated DCAF13 may serve as a diagnostic marker for TNBC metastasis. Functionally, DCAF13 overexpression or suppression was sufficient to enhance or decrease breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Mechanistically, DCAF13 functioned as an RBP by binding with the AU-rich element (ARE) of DTX3 mRNA 3ʹUTR to accelerate its degradation. Moreover, we identified that DTX3 promoted the ubiquitination and degradation of NOTCH4. Finally, increased DCAF13 expression led to post-transcriptional decay of DTX3 mRNA and consequently activated of NOTCH4 signaling pathway in TNBC. In conclusion, these results identified that DCAF13 as a diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for TNBC treatment.

Abbreviation: DCAF13: DDB1 and CUL4-associated factor 13; DDB1: DNA-binding protein 1; CUL4: Cullin 4; CRL4, Cullin-ring finger ligase 4; RBP: RNA binding protein; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; ARE: AU-rich element; DTX3: Deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 3; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ER: estrogen receptor; PR: progesterone receptor; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

KEYWORDS: DCAF13, breast cancer, DTX3, NOTCH4, metastasis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the leading malignant carcinoma in females, which gives rise to approximately 2.1 million new cases and 630 thousand deaths annually worldwide [1]. Early-stage patients are curable, whereas patients with distant metastases have no available therapeutic options currently [2]. Worse still, almost 10–15% of patients with breast cancer deteriorate to higher tumor stage and develop distant metastases within 3 years after the initial detection of the primary tumor [3]. Breast cancer has been molecularly classified into four subtypes: luminal A (ER+/Her2−), luminal B (ER+/Her2+), HER2+ and basal-like [4]. Because a majority of basal-like breast cancers are also triple-negative breast cancers, basal-like subtype has also been claimed as triple-negative breast cancers [5]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which comprises of approximately 12–17% of women with breast tumors, is characterized as breast tumors with lack expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and Her2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) [6]. Owing to inherently aggressive nature and the lack of recognized molecular targets for therapy, patients with TNBC typically have a higher risk of recurrence and relatively worse prognosis compared with those with other breast cancer subtypes [7–9]. Hence, new prognostic markers are urgently needed to distinguish TNBC tumors with high metastatic potential, which may enable pharmacist to design and screen effective treatment molecules.

RNA binding proteins (RBPs) are proteins that bind to RNA, which orchestrate the production, maturation, localization, translation, and degradation of cellular RNAs [10]. Recent studies have revealed that dysregulation in RBP-RNA networks activity have been causally correlated with cancer development [11,12]. Recently studies have linked a number of RBPs with drug resistance and disease progression in breast cancer. For example, NONO has been identified as oncogenic RBP whose abnormal upregulation results in tumor progression and epirubicin resistance by increasing STAT3 protein stability and its transcriptional activity in TNBC [13]. Likewise, MSI2a overexpression leads to enhanced interaction with the 3′-untranslated region of TP53INP1 mRNA, thereby contributing to elevated TP53INP1 mRNA stability and cell invasion in TNBC [14].

DCAF13 (DDB1 and CUL4 associated factor 13) belongs to the family of DDB1 and CUL4 associated factors, which were identified as substrate receptors of CUL4-DDB1 E3 ligase [15]. As a substrate receptor of CRL4, DCAF13 bridged CRL4 E3 ligase to histone methyltransferase SUV39H1 for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, which facilitated H3K9me3 removal and zygotic gene expression [16]. In osteosarcoma cells, CRL4B-DCAF13 E3 ligase complex specifically recognized the tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) for degradation [17,18]. Recent study has also identified DCAF13 as a nucleolar protein that participated in the 18S rRNA processing in growing oocytes [19].

In this study, we disclosed that DCAF13, acted as a novel RNA RBP, was significant upregulated in TNBC, which promoted us to further explore its role in TNBC.

Results

DCAF13 is significantly unregulated in TNBC tissues and indicates a poor prognosis

We first investigated the clinicopathological characteristics of DCAF13 in the Cancer Genome Atlas dataset (TCGA) (Table SII). TCGA revealed that mRNA level of the DCAF13 was significantly increased in TNBC specimens when compared to the level in normal breast tissue and other subtypes (Figure 1(a)). TNBC patients with high DCAF13 expression had a predominantly shorter overall survival (OS) than those with low DCAF13 expression (Figure 1(b) and Figure S1). We next quantified DCAF13 expression in 97 pairs of TNBC specimens and adjacent normal tissues using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) (Table SI). TNBC specimens displayed saliently upregulation of DCAF13 mRNA expression compared to adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1(c)). Analysis of the correlation between DCAF13 mRNA expression and clinicopathological characteristics revealed that higher DCAF13 mRNA expression was observed in metastatic tissues, patients with advanced tumor grade and recurrence (Figure 1(c)). In addition, IHC and western blot analysis showed DCAF13 protein expression was increased in TNBC compared with adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1(d,e)). Taken together, these data indicated that DCAF13 is a potential prognostic marker for TNBC metastasis.

Figure 1.

DCAF13 is significantly unregulated in TNBC tissues and indicates a poor prognosis. (a) Representative data obtained from TCGA showing relative DCAF13 mRNA expression in normal breast tissues and different subtypes. (b) Kaplan-Meier analysis of data obtained from TCGA revealed TNBC patients with higher DCAF13 expression indicated poor OS; the Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed using R package (survminer) and the cutoff point was displayed in Fig. S1. (c) Correlation between DCAF13 mRNA expression and clinicopathological characteristics in 97 pairs of TNBC specimens and adjacent normal tissues. (d) IHC staining of DCAF13 in TNBC specimens and adjacent normal tissues; scale bar represents 50 μm. (e) Western blot analysis of DCAF13 in TNBC specimens (t) and adjacent normal tissues (n). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001

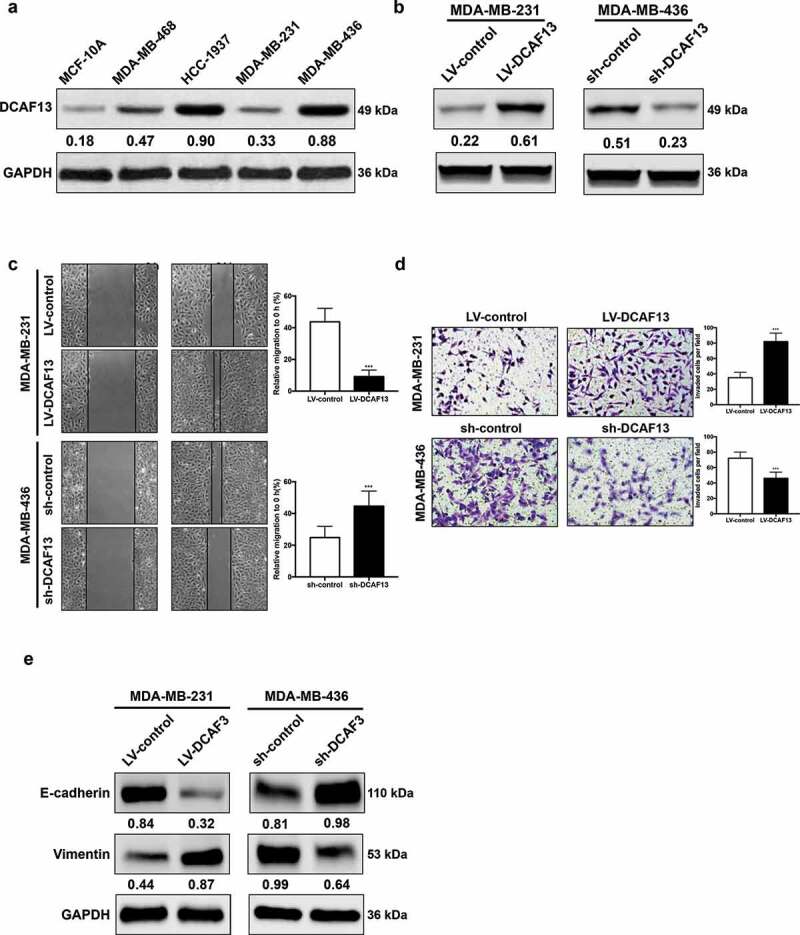

DCAF13 promotes TNBC invasion

To evaluate the role of DCAF13 in TNBC, protein expression of DCAF13 was examined in a panel of TNBC cell lines and human normal mammary epithelial cells (Figure 2(a)). For loss- and over-expression analysis, we overexpressed and knocked down DCAF13 in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 cells according to Figure 2(a) results, respectively (Figure 2(b)). DCAF13 forced expression markedly promoted MDA-MB-231 cell migration and invasion, whereas DCAF13 repression notably reduced cell migration and invasion capabilities in MDA-MB-436 cells (Figure 2(c,d)). Consistently, DCAF13 forced expression decreased the epithelial marker E-cadherin, while increased the mesenchymal marker Vimentin (Figure 2(e)). However, DCAF13 repression had the opposite effect. Overall, these findings suggested that DCAF13 dramatically promotes TNBC metastasis.

Figure 2.

DCAF13 promotes TNBC invasion. (a) Western blot analysis of DCAF13 in TNBC cell lines and human normal mammary epithelial cells. (b) Western blot analysis of DCAF13 in overexpression and knockdown cell lines. (c-d) Wound healing assay and Transwell assay of DCAF13-overexpressed and knockdown cell lines. (e) Western blot analysis of EMT markers. ***P < 0.001

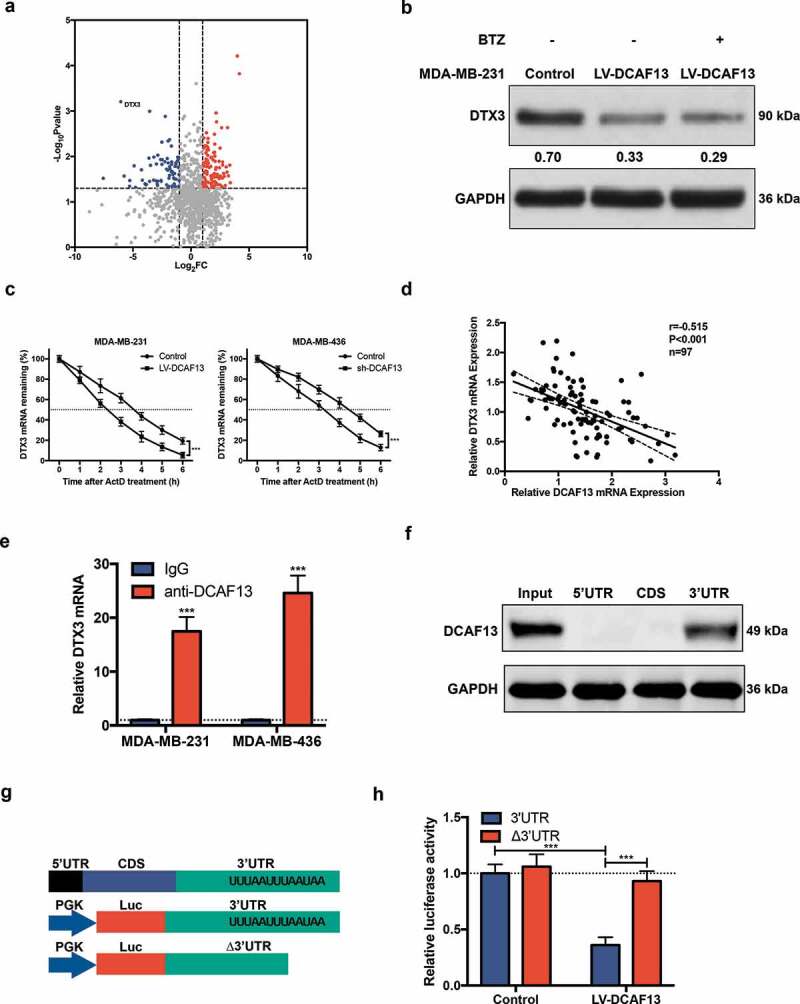

DCAF13 binds to DTX3 mRNA 3ʹUTR and promotes its degradation

To explore the downstream targets of DCAF13, RNA-immunoprecipitation and sequencing (RIP-seq) was performed to identify the binding targets of DCAF13. RIP-seq analysis revealed a total of 174 differentially expressed genes with Log2FC≥1 and P ≤ 0.05 (Table SIII). Among these genes, DTX3 (Deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 3) was the most noticeable gene (Figure 3(a)). As DCAF13 always wields its influence as a substrate receptor of E3 ligase, proteasomal inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ) was used to confirm whether DTX3 downregulation was due to proteasomal degradation. Western blot analysis didn’t show a significant restoration of DTX3 protein upon BTZ treatment in DCAF13 overexpressed MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 3(b)). We next treated TNBC cells with actinomycin D (ActD) to inhibit RNA transcription. mRNA decay assay demonstrated that DCAF13 overexpression decreased the half-life time of DTX3 mRNA, whereas DCAF13 repression elevated it (Figure 3(c)). We also found a negative correlation between DCAF13 mRNA and DTX3 mRNA expression in TNBC patients (Figure 3(d)). Hence, DCAF13 might function as a RBP that regulates DTX3 in mRNA level. RIP-qPCR results indicated a markedly enrichment of DTX3 mRNA in anti-DCAF13 immunoprecipitates (Figure 3(e)). RNA pull-down assay showed DCAF13 protein specially bound to DTX3 in mRNA 3ʹUTR (Figure 3(f)). After searching the AU-Rich Element Database (ARED-Plus) [20], we found that the 3ʹUTR of DTX3 mRNA contains a cluster (UUUAAUUUAAUAA) of the ARE motif (Figure 3(g) up) which serve as potential binding targets for DCAF13. To further verify that DCAF13 mediates DTX3 mRNA degradation via ARE motifs in its 3ʹUTR, dual-luciferase assays were performed using pmirGLO reporter vector that the entire 3ʹUTR sequence of DTX3 fused to Luc gene (Figure 3(g) down). Forced expression of DCAF13 notably reduced luciferase activity, while deletion of ARE motif significant restored the luciferase activity (Figure 3(h)). Collectively, these results indicated that DCAF13 regulates DTX3 mRNA decay through its ARE-containing 3ʹUTR.

Figure 3.

DCAF13 binds to the 3ʹUTR of DTX3 mRNA and promotes its degradation. (a) RIP-seq analysis of differently expressed genes in DCAF13 overexpressed MDA-MB-231 cells compared to control group. (b) Western blot analysis of MDA-MB-231 cells that were treated with 1 μM BTZ for 2 hours. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of DTX3 mRNA after cells were treated with 5 μg/ml actinomycin D at indicated time. (d) Spearman correlation analysis of DCAF13 mRNA and DTX3 mRNA expression in TNBC patients. (e) RIP-qPCR analysis of DTX3 mRNA enrichment in anti-DCAF13 immunoprecipitate. (f) RNA pull-down analysis of the binding region of DCAF13 protein to DTX3 mRNA. (g) Schematic representation of DTX3 mRNA and dual-luciferase reporter vector. (h) Dual-luciferase assay of DCAF13 protein bound to the ARE-containing 3ʹUTR of DTX3 mRNA. ***P < 0.001

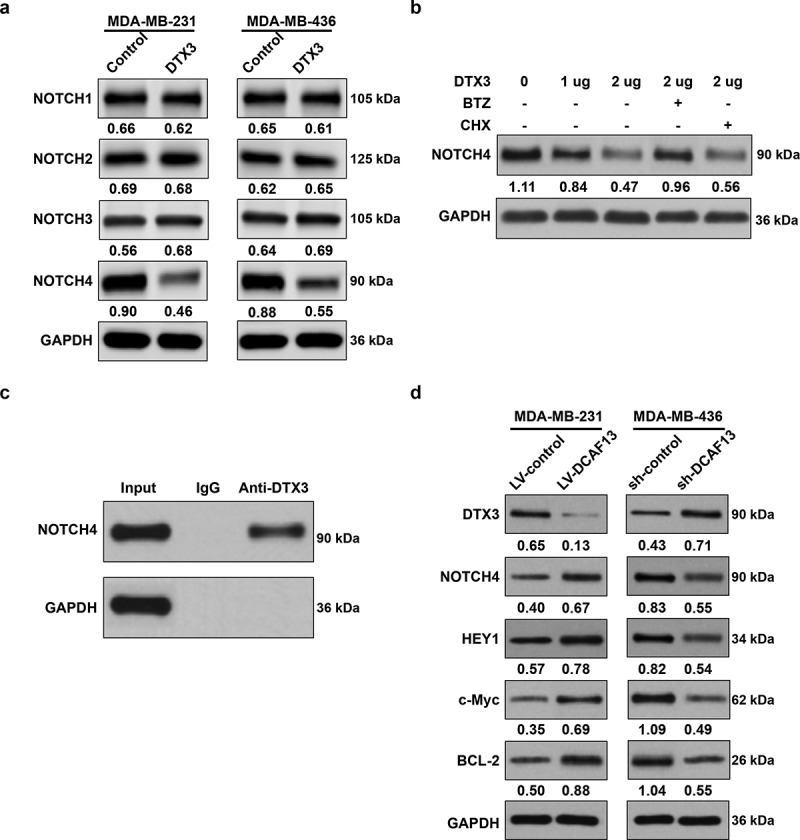

DCAF13 activates NOTCH4 signaling pathway via DTX3

Noted that DTX3 is a member of the DTX family which acts as NOTCH signaling modifiers [21], NOTCH signaling pathway has been further studied. We firstly transfected TNBC cell lines with pcDNA3.1-DTX3. Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant downregulation of NOTCH4 when DTX3 was forced expressed (Figure 4(a)). DTX3 modulated NOTCH4 protein degradation in a dose dependent manner, which was markedly inhibited when treated with proteasomal inhibitor BTZ (Figure 4(b)). Co-Immunoprecipitation displayed a direct binding of DTX3 with NOTCH4 (Figure 4(c)). NOTCH4 signaling activation markers, HEY1, c-Myc and BCL-2, were upregulated in DCAF13 overexpressed MDA-MB-231 cells, whereas were reduced in DCAF13 repressed MDA-MB-436 cells (Figure 4(d)). Altogether, DCAF13 activates NOTCH4 signaling pathway via DTX3 in TNBC.

Figure 4.

DCAF13 activates NOTCH4 signaling pathway via DTX3. (a) DTX3 forced expression reduced NOTCH4 protein expression. (b) DTX3 targeted NOTCH4 degradation was proteasomal dependent; MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with pcDNA3.1-DTX3, 1 μM BTZ and 100 μg/ml protein translation inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) to determine the downregulation of NOTCH4 was due to proteasomal degradation or translation inhibition. (c) Co-immunoprecipitation showed a direct binding of DTX3 with NOTCH4. (d) DCAF13 regulated NOTCH4 signaling pathway

Discussion

This study revealed that DCAF13, a substrate receptor of CUL4-DDB1 E3 ligase, functions as an RBP in TNBC metastasis. Clinical data obtained from TCGA and our collection showed that DCAF13 was closely correlated with poor clinicopathological characteristics and overall survival, which indicated DCAF13 may serve as a diagnostic marker for TNBC metastasis. In vitro studies demonstrated that DCAF13 overexpression promoted TNBC cell invasion and metastasis, while knockdown of DCAF13 suppressed TNBC cell invasion and metastasis. Mechanistical exploration uncovered that DCAF13 functioned as an RBP by binding with the ARE of DTX3 mRNA 3ʹUTR to accelerate its degradation. Moreover, we identified that DTX3 promoted the ubiquitination and degradation of NOTCH4. These results suggest that the DCAF13/DTX3/NOTCH4 axis plays a metastasis-promoting role in TNBC.

DTX3 belongs to the Deltex (DTX) family that functions as an E3 enzyme and acts as NOTCH signaling modifiers to control cell fate determination [22]. The Deltex family, constituted of five members (DTX1, DTX2, DTX3, DTX4, and DTX3L), is characterized by a conserved C-terminal region of about 150 residues and a divergent N-terminal [23]. A recent study reported that DTX3 inhibited the proliferation and migration of human esophageal carcinoma by targeted ubiquitination of NOTCH2 [24]. Here, we identified DCAF13 activated NOTCH4 signaling pathway via DTX3. DCAF13 overexpression reduced DTX3 mRNA stability and activated NOTCH4 signaling pathway, whereas DCAF13 knockdown increased DTX3 level and led to ubiquitination of NOTCH4 (Figure 4(d)). In addition, DCAF13 overexpression induced DTX3 protein reduction wasn’t abrogated by BTZ, yet actinomycin D significantly decreased the half-life time of DTX3 mRNA, suggesting that DCAF13 promoted DTX3 degradation in mRNA level, not in protein level as a DCAF13/CUL4/DDB1 E3 ligase complex (Figure 3(b,c)). Deletion of ARE sequence of DTX3 mRNA notably abolished the binding of DCAF13 (Figure 3(h)).

NOTCH signaling has a major role in the maintenance and progression of tumors, including promoting EMT, angiogenesis and conferring resistance to radiation and chemotherapeutic agents [25]. It is generally accepted that NOTCH signaling is aberrantly activated in human breast cancer, which involved in the regulation of breast cancer stem cell activity, EMT, angiogenesis, and proinflammatory cytokines [26–29]. Recent research published by Zhou et al. has intensively revealed that the NOTCH4 contributed to the maintenance of quiescent mesenchymal-like breast cancer stem cells via transcriptionally activating SLUG and GAS1 in TNBC [30]. We found that NOTCH4 was a novel ubiquitin substrate of DTX3 and its expression was indirectly regulated by DCAF13 in TNBC (Figure 4(d)). Emerging of stem cell phenotype is associated with early disseminating of cancer cells and indicated a poor prognosis [31]. The positive correlation of DCAF13 and NOTCH4 may be partly in according with their convergent role in regulating stemness.

n conclusion, our work highlighted the importance of DCAF13/DTX3/NOTCH4 axis during the metastasis of TNBC and provided diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for TNBC treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimen

97 pairs of TNBC specimens and adjacent normal tissues were collected at Minhang Hospital affiliated to Fudan University between 2015 and 2019 with patients’ consent. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Minhang Hospital and was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Detailed clinicopathological characteristics of patients were listed in Table SI.

Cell line culture, stable cell line construction and cell transfection

All human breast cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 cells were cultured in L-15 medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Australia source), 100 μg/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, China) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. DCAF13 overexpressed MDA-MB-231 cell line was constructed by infecting with lentivirus containing DCAF13 coding sequence (CDS) using pLVX-Puro plasmid. DCAF13 knocked down MDA-MB-436 cell line was constructed by infecting with lentivirus containing shRNA (CCGGAATCTTTCCTGTAGACAAATTCAAGAGATTTGTCTACAGGAAAGATTTTTTTT) using pLVX-shRNA1 plasmid. Stable cell lines were selected the by puromycin. Cell transfection was performed using PEIpro (Polyplus) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Single-strand cDNA synthesis and PCR amplification was performed using Superscript II first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). qPCR was run using SYBR Premix ExTaq (TaKaRa) on ABI StepOne system. GAPDH was used as an internal control. DCAF13, F: GGAACTCCTAGCGGACACCT, R: CAACTTGGTTTCGCGGACATA. DTX3, F: CTCATAGATGGCGAGACTTCTGA, R: GGCTAGGTAGAGCCCATTTGG. GAPDH, F: CTCACCGGATGCACCAATGTT, R: CGCGTTGCTCACAATGTTCAT.

Immunohistochemistry staining

Paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 4 μm sections. The sections were deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated in gradient alcohol, treated with 3% H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase, incubated with anti-DCAF13 antibody (Abcam, ab195121) at 4°C overnight. and then the sections were incubated with the anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody (CST, 7074) at room temperature for 30 min followed by visualizing with diaminobenzidine and counterstaining with hematoxylin.

Western blot and co-immunoprecipitation

Protein was extracted by lysing cell pellets with RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and protein concentration was quantified with BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Equal amount of total protein of each sample was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore), blocked with skim milk, incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, and then probed with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 hours. Signal was detected with BIO-RAD Gel Doc XR. The primary antibodies were listed as follows: DCAF13 (Abcam, ab195121), DTX3 (Novus Biologicals, NBP1-46,127), NOTCH1 (Abcam, ab52627), NOTCH2 (Abcam, ab8926), NOTCH3 (Abcam, ab23426), NOTCH4 (CST, 2423), E-cadherin (Abcam, ab1416), Vimentin (Abcam, ab92547), HEY1 (Abcam, ab22614), c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-40), BCL-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7382), GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-32,233). For co-immunoprecipitation assay performed in Figure 4(c), MDA-MB-231 cell lysates were incubated with anti-DTX3 antibody at 4°C overnight and then incubated with protein A Sepharose CL-4B beads (GE) for 2 hours. The beads were then washed with RIPA buffer and the precipitates were used for western blot. Protein bands were quantified by ImageJ software and normalized to internal control GAPDH. The ratio of protein/GAPDH was showed under the protein band.

Wound healing assay

Cells were seeded into 24-well plates. When the cells reached 80% confluence, a scratch was made with a 200 μl sterile pipette tip. The wounded closures were imaged at 0 hour and 24 hours after the scratch were made using an inverted microscope (400 ×).

Transwell assay

Transwell assay was performed with 24-well BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (BD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The upper wells were seeded with 20,000 cells and cultured with complete medium but devoid of FBS. The lower wells were filled with complete medium. After 24 hours, cells invaded through the Matrigel were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde Fix Solution (Beyotime) for 30 minutes and then stained with crystal violet (Beyotime) for 30 minutes at 37°C. After washed with PBS, 5 randomly selected fields were imaged (400 ×) and counted.

RNA Immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-seq) and qPCR (RIP-qPCR)

Cell lysates were incubated with anti-DCAF13 antibody (Abcam, ab195121) overnight at 4°C, and then the DCAF1-RNA complex was collected using EZ-Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, 17–701) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The immunoprecipitates were treated with proteinase K digestion (Roche) and fragmentation. The remaining RNA was collected for RNA library construction. RNA library was constructed by using VAHTSTM Stranded mRNA-seq Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA libraries were sequenced by Illumina Hiseq 4000 system. For RIP-qPCR performed in Figure 3(e), the immunoprecipitates were treated with proteinase K digestion (Roche) and then used for qRT-PCR.

mRNA decay assay

Cells were treated with 5 μg/mL actinomycin D to inhibit RNA transcription. Total DTX3 mRNA was isolated at the indicated time points and the expression of DTX3 mRNA was analyzed using qRT-PCR and normalized to the internal control GAPDH.

RNA pull-down assay

The full-length 5ʹUTR, CDS and 3ʹUTR of DTX3 were synthesized and cloned into pcDNA3.1 plasmid (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai). DNA sequence was added with a 5′T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence using KOD OneTM PCR Master Mix (TOYOBO). The RNA sequence was produced by using T7 RNA Polymerase (Roche). The potential RBPs of DTX3 mRNA were harvest by using PierceTM Magnetic RNA-Protein Pull-Down Kit (Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then used for western blot.

Luciferase reporter assay

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, DCAF13 overexpressed MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with pmirGLO-DTX3-3ʹUTR or pmirGLO-DTX3-∆3ʹUTR (deletion of UUUAAUUUAAUAA) plasmid together with pRL-Renilla vector as an internal control plasmid. Cells were lysed 24 hours after transfection to measure the levels of luciferase activities.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± SD unless otherwise specified. Date analyses were performed using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA test with GraphPad Prism 7. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed and plotted using R package (survminer). *p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Youth Project of Shanghai Minhang District Central Hospital (grants number: 2020MHJC03).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors’ contributions

G. Pan and J. Qie conceived and designed the experiments; J. Liu and H. Li performed most of the experiments; A. Mao and J. Lu conducted the IHC experiment; W. Liu performed the RIP-sequencing experiment; G. Pan and J. Liu analyzed the data; J. Liu and G. Pan wrote and revised the manuscript.

Ethics approval statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Minhang Hospital affiliated to Fudan University (Shanghai, China) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van ‘T Veer LJ.. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Caparica R, Lambertini M, de Azambuja E. How I treat metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. ESMO Open. 2019;4:e000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:674–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bergin ART, Loi S. Triple-negative breast cancer: recent treatment advances. F1000Res. 2019;8:1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dominguez D, Freese P, Alexis MS, et al. Sequence, structure, and context preferences of human RNA binding proteins. Mol Cell. 2018;70:854–67 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pereira B, Billaud M, Almeida R. RNA-binding proteins in cancer: old players and new actors. Trends Cancer. 2017;3:506–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wurth L, Gebauer F. RNA-binding proteins, multifaceted translational regulators in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1849:881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kim SJ, Ju JS, Kang MH, et al. RNA-binding protein NONO contributes to cancer cell growth and confers drug resistance as a theranostic target in TNBC. Theranostics. 2020;10:7974–7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li M, Li A-Q, Zhou S-L-LVH, et al. RNA-binding protein MSI2 isoforms expression and regulation in progression of triple-negative breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39. DOI: 10.1186/s13046-020-01587-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee J, Zhou P. DCAFs, the missing link of the CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell. 2007;26:775–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu Y, Zhao LW, Shen JL, et al. Maternal DCAF13 regulates chromatin tightness to contribute to embryonic development. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen Z, Zhang W, Jiang K, et al. MicroRNA-300 regulates the ubiquitination of PTEN through the CRL4B(DCAF13) E3 ligase in osteosarcoma cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;10:254–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen B, Feng Y, Zhang M, et al. Small molecule TSC01682 inhibits osteosarcoma cell growth by specifically disrupting the CUL4B-DDB1 interaction and decreasing the ubiquitination of CRL4B E3 ligase substrates. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:1857–1870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang J, Zhang YL, Zhao LW, et al. Mammalian nucleolar protein DCAF13 is essential for ovarian follicle maintenance and oocyte growth by mediating rRNA processing. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1251–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bakheet T, Hitti E, Khabar KSA. ARED-Plus: an updated and expanded database of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs and pre-mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D218–D20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Takeyama K, Aguiar RC, Gu L, et al. The BAL-binding protein BBAP and related Deltex family members exhibit ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21930–21937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Miyamoto K, Fujiwara Y, Saito K. Zinc finger domain of the human DTX protein adopts a unique RING fold. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Obiero J, Walker JR, Dhe-Paganon S. Fold of the conserved DTC domain in Deltex proteins. Proteins. 2012;80:1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ding XY, Hu HY, Huang KN, et al. Ubiquitination of NOTCH2 by DTX3 suppresses the proliferation and migration of human esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:489–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Harrison H, Farnie G, Howell SJ, et al. Regulation of breast cancer stem cell activity by signaling through the Notch4 receptor. Cancer Res. 2010;70:709–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Krishna BM, Jana S, Singhal J, et al. Notch signaling in breast cancer: from pathway analysis to therapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;461:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shen Q, Cohen B, Zheng W, et al. Notch shapes the innate immunophenotype in breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1320–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stylianou S, Clarke RB, Brennan K. Aberrant activation of notch signaling in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1517–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhou L, Wang D, Sheng D, et al. NOTCH4 maintains quiescent mesenchymal-like breast cancer stem cells via transcriptionally activating SLUG and GAS1 in triple-negative breast cancer. Theranostics. 2020;10:2405–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Balic M, Lin H, Young L, et al. Most early disseminated cancer cells detected in bone marrow of breast cancer patients have a putative breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:5615–5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.