Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous uterine rupture before onset of labour is extremely rare. This is even more so in the second trimester of pregnancy, in nulliparous women and in the absence of myometrial surgery. The initial presentation of this potentially catastrophic event may be non-specific, with upper or lower abdominal discomfort, vague gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms preceding rapid deterioration.

Discussion

This case report demonstrates that a high index of suspicion, rapid diagnosis aided by imaging modalities and immediate surgical intervention are crucial steps in successful management. A postulated etiology in our patient is that of an upper scar from a previous uterine curettage with abnormal placentation predisposing to spontaneous rupture.

Presentation of case

A case of spontaneous uterine rupture at 16 week's gestation in a multiparous, 32 year old patient with no history of myometrial surgery. She had presented with lower abdominal discomfort, progressing to severe pain with hypotension and tachycardia. An urgent ultrasound pelvis showed a live fetus, free intra-peritoneal fluid with blood clots. An emergency laparotomy performed revealed 2 L of hemoperitoneum, with the fetus intact in the amniotic sac. The uterine fundal rupture was successfully repaired.

Conclusion

Despite the gestation, in women presenting with symptoms and signs suggestive of acute abdomen and hemodynamic instability, prompt resuscitation must be instituted, and a high index of suspicion for rupture must be suspected.

Keywords: Spontaneous uterine rupture, Second trimester, Fetus, Hemoglobin, Diagnosis, MDT management, Hemostasis

Highlights

-

•

Unusual case of a second uterine rupture early in the second trimester distant from the CS scars.

-

•

Spontaneous uterine rupture in the second trimester has high maternal morbidity &mortality.

-

•

The most common site of spontaneous uterine rupture in the second trimester is the fundus.

1. Introduction

Our paper has been reported according to SCARE criteria [1].

Uterine rupture is a serious obstetric complication. It occurs mainly in the third trimester of pregnancy or during labor, especially in previously scarred uterus. Advanced maternal age, grand multiparous, placenta increta, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia and medical termination of pregnancy are some of the contributing factors to uterine rupture [2].

Uterine rupture in the first or second trimester of pregnancy are extremely rare. Presenting symptoms may be masked by physiological and anatomical changes during pregnancy, which makes the clinical diagnosis sometimes challenging [3]. The lack of high index of clinical suspicion and poor awareness among obstetricians usually results in delayed diagnosis, which can result in grave complications and poor outcome. Unlike rupture in the lower uterine segment in the third trimester or during delivery, the common site of rupture in the first trimester is the fundal region [4,5].

2. Case report

At 28 years old multiparous woman, 16 weeks pregnant, presented to the emergency department on night shift with history of sudden onset of epigastric pain radiating to the back and fainting in her home. On presentation patient was stable vitally, admitted to the Gynecology ward under observation.

Her first pregnancy was a Cesarean delivery for a term breech presentation followed by two successful vaginal deliveries. She had one first-trimester miscarriage, managed surgically. No previous medical disorders. No relevant family history. No previous surgeries.

On presentation, patient was found to be vitally stable however, she was admitted to Gynecology under observation and for pain management. On admission, Blood requested for full blood count, Urea and Electrolytes, Blood group. Paracetamol 1 g IV prescribed as pain relief. Scan booked routine.

After 4 hours of admission, patient experienced a dramatic deterioration in vital signs. She became tachycardic 120 bpm and blood pressure of 90/50. She also reported shoulder tip pain and shortness of breath.

On examination patient looked pale, abdomen was distended showing signs of peritonism, tenderness, rebound tenderness, and guarding. FBC was done showing Hemoglobin of 8 gm% dropped to 4 gm% on hemacue. A bedside ultrasound conducted showed single viable intrauterine pregnancy and large amount of free fluid in the abdomen suggestive of hemoperitoneum. Patient consented for midline exploratory laparotomy, risk of miscarriage explained.

Oncall team attended the patient and differential diagnosis of ruptured ovarian cyst, heterotrophic pregnancy, and perforated viscus considered. Surgical senior registrar informed to assist in the procedure. Decision was to proceed for a midline infra-umbilical laparotomy under general anesthesia. Consultant informed, decision to start the surgery in view of unstable patient decided.

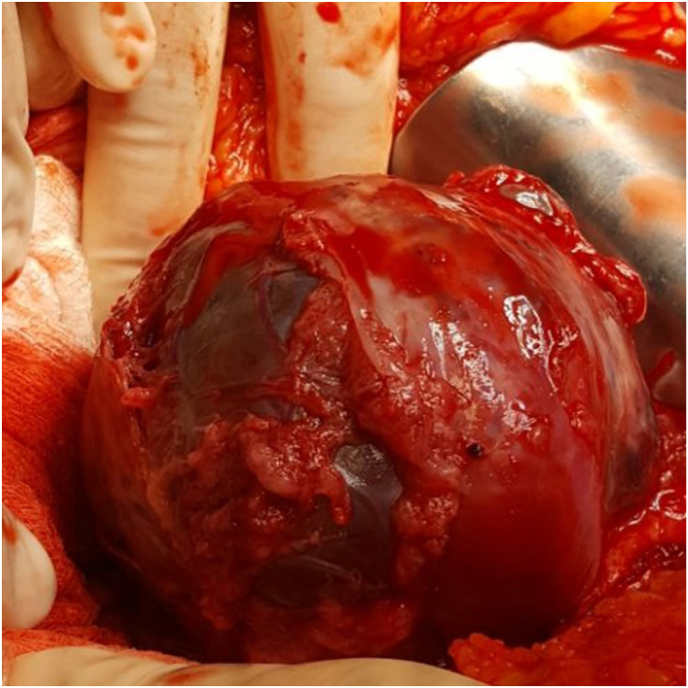

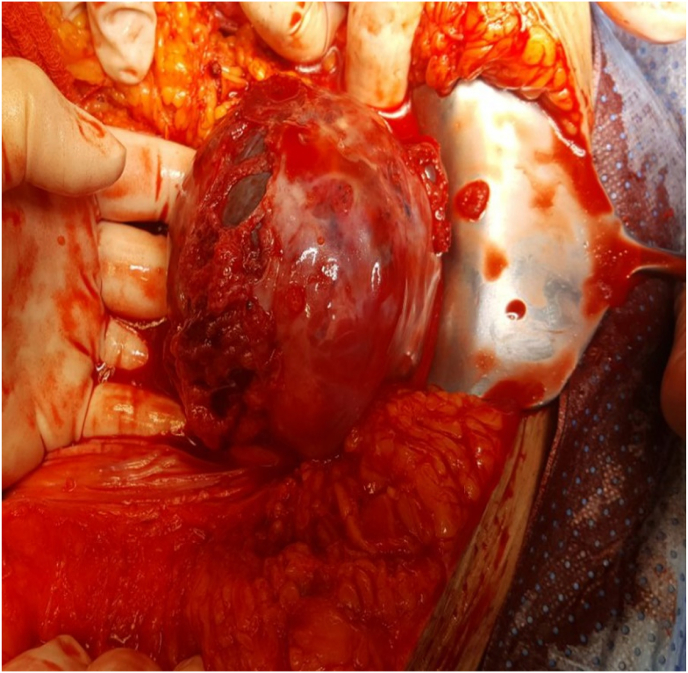

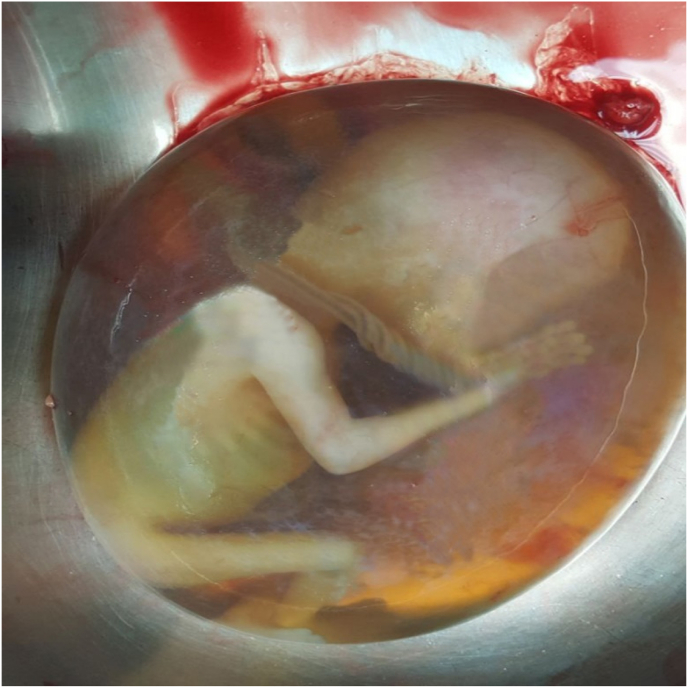

Procedure started by the senior surgical registrar and the senior gynecology registrar revealed more than 2 L of blood and blood clots in pelvis and abdomen. After evacuation of blood a uterine, Exploration of viscera done. A full thickness uterine fundal defect measuring 6 × 4 cm observed together with intact amniotic membrane with alive fetus 300 g and placenta (Fig. 2). In addition, multiple defects with an average diameter of 1 cm seen in the anterior wall of the uterus (Fig. 3). The Cesarean section scar was intact.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous rupture of the uterus at the fundus around 4X6 cm, with multiple bruised uterus.

Fig. 3.

Multiple defects in the fundus and anterior wall of 16 weeks pregnant uterus

Evacuation of pregnancy through uterine defect was done together with repair of uterine defects (Fig. 1), which was fashioned in three continuous layers using vicryl 1/0. Consultant came during the procedure. A decision not to do Hysterectomy taken since the patient was not consented for it. Hemostasis secured and massive blood transfusion protocol initiated. Four units of packed RBC, two fresh frozen plasma given in theatre.

Fig. 1.

16 weeks alive fetus with intact sac delivered through the uterine fundal defect

Postoperatively the patient admitted to HDU. Stayed in hospital for four days recovered well on pain relief. Patient debriefed and counselled about risk of recurrence in future pregnancies and offered contraception. Outpatient appointment 6 weeks after surgery arranged. Patient briefed for the surgical intervention and permanent method of contraception discussed. Patient agreed to be scheduled for tubal sterilization three month after discharge.

2.1. Discussion

Clinical signs of uterine rupture in early pregnancy are non-specific and must be distinguished from acute abdominal emergencies. Abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding and vomiting are classic findings the differential diagnoses are hemorrhagic corpus luteum and heterotrophic pregnancy and other surgical causes of acute abdomen as rupture appendix. Ultrasound has limited value and urgent surgical intervention might be necessary to prevent catastrophic sequelae [6].

Reviewing the literature, eighteen cases of uterine rupture during the second trimester reported, the fundus represents the most common site. Among the nine fundal ruptures, there are two cases were invasive placentation, two cases of adenomyosis, one ruptured cornual pregnancy, one septated uterus and one previous laparoscopic examination. The second most common site is the posterior wall. In two out of three cases, the site corresponded to an old myomectomy scar; in one of these three cases, a curettage was noted in the history. Other sites corresponded to the uterine horns, the anterior wall and the lower segment [7].

The peculiarity of our case is the occurrence of a second trimester uterine rupture at a location other than the previous caesarean section scar. The only identified risk factor was the surgical management of miscarriage that represents a potential iatrogenic risk of occult uterine perforation.

Due to lack of definitive diagnosis before surgical intervention, patient was not consented for hysterectomy so repair was done instead. Suboptimal management done for the fact of excluding rupture uterus as a differential diagnosis in a case of viable intrauterine pregnancy. In the presented case the diagnosis was not clear emergency laparotomy instead of laparoscopy was performed due to the acute presentation and vital instability of the patient [8,9].

3. Conclusion

Uterine rupture should be considered and ruled out in the differential diagnosis in pregnant women presenting with the acute abdomen. Consent for hysterectomy for hemoperitoneum even in early pregnancy. Clinicians set criteria for red flags that would increase the index of suspicion of rupture uterus including previously scarred uterus, cesarean section, surgical management of miscarriage, Uterine instrumentation, Fainting episode, Pallor, Tenderness or rebound tenderness, history of trauma.

Ethics and consent to participate

We have the patient's approval; no more approvals are required.

The work has not been published previously.

Consent to publish

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer reviewed.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Sources of funding

Not applicable.

Author contribution

Diagnosed and treated the patient Manuscript preparation, Literature review: Shereen Ibrahim.

Critical revision of manuscript: Mohamed Okba, Stefanie Drymiotou.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Trial registration number

1. Name of the registry: N/A.

2. Unique Identifying number or registration ID: N/A.

3. Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): N/A.

Guarantor

Shereen Ibrahim, London, N14 6QW.

07502335191.

Consent

Consent had been obtained. All data are anonymous without any identifying details of the patient.

Declaration of competing interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thanks surgical colleagues who helped us in the management of this patient.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P. For the SCARE Group, the SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical Case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J.F., Wax J.R. 2013. Rupture of the Unscarred Uterus.www.uptodate.com UpToDate. [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbab F., Boulieu D., Bied V., Payan F., Lornage J., Guerin J.F. Uterine rupture in first or second trimester of pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum. Reprod. 1996;11(5):1120–1122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park Y.J., Ryu K.Y., Lee J.I., Park M. Spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester: a case report. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 2005;20(6):1079–1081. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.6.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schrinsky D.C., Benson R.C. Rupture of the pregnant uterus: a review. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 1978;33(4):217–232. doi: 10.1097/00006254-197804000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fahrni Anne-Claude, Salomon David, Zitiello Antonio, Feki Anis, Ben Ali Nordine. Recurrence of a second-trimester uterine rupture in the fundus distant from old scars: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Womens Health. 2020 Oct;28 doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2020.e00249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdulwahab Dalia F., Ismail Hamizah, Nusee Zalina. Second-trimester uterine rupture: Lessons Learnt. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2014 Jul;21(4):61–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ijaz S., Mahendru A., Sanderson D. Spontaneous uterine rupture during the 1st trimester: a rare but life-threatening emergency. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2011;31(8):772. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.606932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kilpatrick C.C., Orejuela F.J. 2013. Approach to Abdominal Pain and the Acute Abdomen in Pregnant and Postpartum Women.www.uptodate.com United States (US): Wolters Kluwer Health. [Internet] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available.