Abstract

Salmonella is an important food pathogen that can cause severe gastroenteritis with more than 600,000 deaths globally every year. Colistin (COL), a last-resort antibiotic, is ineffective in bacteria that carry a functional mcr-1 gene, which is often spread by conjugative plasmids. Our work aimed to understand the prevalence of the mcr-1 gene in clinical isolates of Salmonella, as the frequency of occurrence of the mcr-1 gene is increasing globally. Therefore, we analyzed 689 clinical strains, that were isolated between 2009 and late 2018. The mcr-1 gene was found in six strains, which we analyzed in detail by whole genome sequencing and antibiotic susceptibility testing, while we also provide the clinical information on the patients suffering from an infection. The genomic analysis revealed that five strains had plasmid-encoded mcr-1 gene located in four IncHI2 plasmids and one IncI2 plasmid, while one strain had the chromosomal mcr-1 gene originated from plasmid. Surprisingly, in two strains the mcr-1 genes were inactive due to disruption by insertion sequences (ISs): ISApl1 and ISVsa5. A detailed analysis of the plasmids revealed a multitude of ISs, most commonly IS26. The IS contained genes that meditate broad resistance toward most antibiotics underlining their importance of the mobile elements, also with respect to the spread of the mcr-1 gene. Our study revealed potential reservoirs for the transmission of COL resistance and offers insights into the evolution of the mcr-1 gene in Salmonella.

Keywords: Salmonella, mcr-1, IS, inactivation, ISApl1, ISVsa5

Introduction

Colistin (COL) is a polypeptide antibiotic that was first isolated from the supernatant of a Bacillus polymyxa var. colistinus culture (Tambadou et al., 2015). It has been used in both human and veterinary medicine for more than 50 years, although the parenteral use in humans is limited due to issues with nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity (Landman et al., 2008; Biswas et al., 2012). Due to the increase of antimicrobial resistance and the lack of antibiotic compounds that are effective, COL can be deployed in the clinic in combination with other drugs that protect renal function. At present, COL is considered as the last resort option for the treatment of infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria that are multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or pandrug-resistant (PDR) (Nation and Li, 2009).

In 2015, Liu et al. first discovered plasmid-encoded COL resistance, mediated by the gene mcr-1, in Escherichia coli isolated from animals, and demonstrated that the gene, encoded on conjugative plasmids, can be used by different strains to mediate low levels of COL resistance (Liu et al., 2016). While the acquisition of the mcr-1 gene does not result in a new bacterial strain, the recipient strain develops resistance to COL (Schwarz and Johnson, 2016). As the mcr-1 gene is highly transmissible, it has been observed in more than 30 countries on six continents (Wang et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2020), and can be found in different genera (such as E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella sonnei, and Salmonella) isolated from animals, food, or humans worldwide (Hu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Pham Thanh et al., 2016; Schwarz and Johnson, 2016; Al-Tawfiq et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). Strains of Salmonella are important pathogens of concern in food safety, as they are frequently transmitted between agricultural animals, food, and humans (Foley and Lynne, 2008); the pathogens often cause gastroenteritis, in some cases severe, and are responsible for >600,000 deaths annually (Lokken et al., 2016). Increasing antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella species is considered an important public health concern of the 21st century (Lozano-Leon et al., 2019). Salmonella strains that acquire multidrug resistance genes would be difficult to treat and would result in an even higher number of cases with severe morbidity and high frequency of mortality. After Salmonella species carrying mcr-1 were detected in the United Kingdom in 2016, the level of occurrence of mcr-1 in Salmonella among livestock and humans, but also the environment, is increasing worldwide (Cui et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2017b). In addition, although another five mcr variants (mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, mcr-5, and mcr-9) have been identified in Salmonella species (Carattoli et al., 2018; Garcia-Graells et al., 2018; Borowiak et al., 2019; Carroll et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020), mcr-1 is still the most common mcr gene found in COL-resistant Salmonella spp. (Borowiak et al., 2020).

Many studies have focused on the mcr-1 gene-carrying E. coli and K. pneumonia strains, while the prevalence and molecular characteristics of the mcr-1 gene in Salmonella spp. have been investigated in much less detail. The goal of our study is to understand the prevalence of the human-derived mcr-1 gene in community-acquired Salmonella infections in clinical isolates. We conducted a retrospective study to determine the prevalence of mcr-1 positive Salmonella in 689 clinical strains that were isolated between 2009 and 2018. To analyze the level of drug-resistance, we also tested the sensitivity of the isolates to different antibiotic classes, other than COL, and performed a detailed genomic analysis of all mcr-1 positive strains.

Materials and Methods

Strains Source

Salmonella clinical strains were collected from patients in the First People’s Hospital of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China between 2009 and 2018. Most specimens were collected from the departments of Pediatrics, Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Department and Infectious Medicine while other departments were only a secondary source for the isolates. The specimen types of clinical isolates collected included blood, feces, and pus. The cultured bacteria were stored in glycerol broth at −80°C. The DNA from isolates were extracted and screened for the mcr-1 gene by PCR. The mcr-1-positive isolates were verified by Sanger sequencing. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou First People’s Hospital (2020103-1) with a waiver of informed consent because of the retrospective nature of the study. All strains were identified using the automated Vitek 2 system (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker, Bremen, Germany). Salmonella serotyping was conducted by slide agglutination with specific antisera (Tianrun Bio-Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) according to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme (9th edition).

PCR Amplifications and Sequencing

All collected isolates were screened for the presence of mcr-1 positive strains using PCR with the primers mcr-1-forward (5′-GCTCGGTCAGTCCGTTTG-3′) and mcr-1-reverse (5′-GAA TGCGGTGCGGTCTTT-3′). The amplicons were subsequently sequenced by Sanger sequencing (Quan et al., 2017).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

Broth micro-dilution and E-test method were used to determine the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of COL and 13 other antibiotics: ampicillin (AMP), ceftriaxone (CRO), cefepime (FEP), tetracycline (TET), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC), cefotaxime (CTX), chloramphenicol (C), meropenem (MEM), imipenem (IPM), azithromycin (AZM), cefoxitin (FOX), amikacin (AK) and ciprofloxacin (CIP), according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100-S29 (CLSI, 2019). Most results were interpreted in accordance with CLSI, except COL and tigecycline, for which we used the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints v8.1. The quality control strain used in the antimicrobial sensitivity test was E. coli ATCC 25922.

Genomic DNA Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from six mcr-1-positive strains and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq and Nanopore MinION platforms. Long-read library preparation for Nanopore sequencing was performed with a 1D sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109; Nanopore) without fragmentation. The libraries were then sequenced on a MinION device with a 1D flow cell (FlO-MIN106; Nanopore) and base called with Guppy v2.3.5 (Nanopore). The long read and short read sequence data were used in a hybrid de novo assembly using Unicycler v0.4.8 (Wick et al., 2017), then polished with Pilon v1.23 (Walker et al., 2014). Antibiotic resistance genes were identified using the ResFinder database (Zankari et al., 2012) with Abricate 0.81 or BacAnt (Hua et al., 2020). Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was performed using mlst2. Sequence comparisons were performed using BLAST and visualized with Easyfig 2.2.2 (Sullivan et al., 2011).

Plasmid Conjugation Experiments

Conjugation experiments were performed by broth and filter mating using the sodium azide-resistant E. coli J53 as the recipient strains. The mixture (ratio of 1:1) of donors and the recipient strain J53 were subjected to incubation on MH agar plates for 18 h at 37°C. The successful transconjugants were selected on MH agar plates supplemented with 250 μg/mL sodium azide and 2 μg/mL CTX (or 1 μg/mL COL). The carriage of such a plasmid in the parental strain and the corresponding transconjugants were confirmed by PCR and MALDI-TOF MS. The MIC profiles of the transconjugants were also determined with antibiotics (AK, CTX, COL, TET, and AMP) by the broth microdilution method (CLSI, 2019).

Results

Screening for mcr-1 Positive Strains

A total of 689 clinical Salmonella isolates were screened in this study, all of which were derived from patient specimen isolates from May 2009 to December 2018 in Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, Zhejiang Province, China. The isolates analyzed included more than ten species of Salmonella, that cause a wide range of pathologies including typhoid fever, swine cholera, and enteritis and belong to various Salmonella spp. such as S. Typhimurium, S. Enteritidis, S. Choleraesuis, S. Thompson, S. Manhattan, S. Derby, S. London, S. Senftenberg, and S. Aberdeen (Table 1). When screening for the mcr-1 gene by PCR, we detected six isolates (0.87%) of the 689 Salmonella strains, that were mcr-1 positive. Interestingly, the isolate S520 showed a longer mcr-1 PCR product than other strains (Supplementary Figure 1), indicating an insertion in the mcr-1 gene, or possibly a duplication. To confirm that these six strains harbored the mcr-1 gene, we performed whole genome sequencing. While five strains had a plasmid-encoded mcr-1 gene, one strain contained the gene as part of the bacterial chromosome. The results are described below in more detail.

TABLE 1.

Serotype distribution of 679 Salmonella isolates.

| Serogroup | Serotype | O antigens | H antigens | No. of isolates (%) |

| A group (2) | S. Paratyphi A | 1, 2, 12 | a: [1, 5] | 2 (0.3) |

| B group (289) | S. Typhimurium | 1, 4, [5], 12 | i: 1, 2 | 227 (33.0) |

| S. Derby | 1, 4, [5], 12 | f, g: [1, 2] | 20 (2.9) | |

| S. Saintpaul | 1, 4, [5], 12 | e, h: 1, 2 | 9 (1.3) | |

| S. Agona | 1, 4, [5], 12 | f, g, s: [1, 2] | 12 (1.7) | |

| S. Stanleyville | 1, 4, [5], 12, [27] | d: 1, 2 | 7 (1.0) | |

| S. Indiana | 1, 4, 12 | z: 1, 7 | 4 (0.6) | |

| others | 1, 4, 12 | – | 10 (1.5) | |

| C1 group (118) | S. Choleraesuis | 6, 7 | c: 1, 5 | 12 (1.7) |

| S. Infantis | 6, 7, 14 | r: 1, 5 | 18 (2.6) | |

| S. Irumu | 6, 7 | l, v: 1, 5 | 5 (0.7) | |

| S. Virchow | 6, 7, 14 | r: 1, 2 | 5 (0.7) | |

| S. Thompson | 6, 7, 14 | k: 1, 5 | 27 (3.9) | |

| S. Potsdam | 6, 7, 14 | l, v: e, n, z15 | 10 (1.5) | |

| S. Braenderup | 6, 7, 14 | e, h: e, n, z15 | 7 (1.0) | |

| S. Mbandaka | 6, 7, 14 | z10: e, n, z15 | 4 (0.6) | |

| S. Rissen | 6, 7, 14 | f, g: – | 5 (0.7) | |

| S. Montevideo | 6, 7, 14 | g, m, [p], s: [1, 2, 7] | 2 (0.3) | |

| others | 6, 7, 14 | – | 23 (3.3) | |

| C2 group (35) | S. Manhattan | 6, 8 | d: 1, 5 | 3 (0.4) |

| S. Newport | 6, 8, 20 | e, h: 1, 2 | 7 (1.0) | |

| S. Bovismorbificans | 6, 8, 20 | r, [i]: 1, 5 | 10 (1.5) | |

| S. Litchfield | 6, 8 | l, v: 1, 2 | 9 (1.3) | |

| others | 6, 8 | – | 6 (0.9) | |

| D group (157) | S. Enteritidis | 1, 9, 12 | g, m: [1,7] | 154 (22.4) |

| S. Gallinarum-pullorum | 1, 9, 12 | – | 2 (0.3) | |

| others | 1, 9, 12 | :H5 | 1 (0.1) | |

| E1 group (51) | S. London | 3, {10} {15} | l, v: 1, 6 | 37 (5.4) |

| S. Weltevreden | 3, {10} {15} | r: z6 | 5 (0.7) | |

| S. Ruzizi | 3, 10 | l, v: e, n, z15 | 1 (0.1) | |

| S. Vejle | 3, {10} {15} | e, h: 1, 2 | 1 (0.1) | |

| S. Anatum | 3, {10} {15} {15,34} | e, h: 1, 6 | 1 (0.1) | |

| others | 10 | – | 6 (0.9) | |

| E4 group (25) | S. Senftenberg | 1, 3, 19 | g, [s], t: – | 21 (3.0) |

| others | 19 | – | 4 (0.6) | |

| F group (5) | S. Aberdeen | 11 | i: 1, 2 | 5 (0.7) |

| Other groups (5) | S. enterica subsp. diarizonae | 2 (0.3) | ||

| others | 3 (0.4) |

Clinical Information on Patients Suffering From a Salmonella mcr-1 Positive Infection

The detailed clinical information about mcr-1 positive patients is shown in Table 2. The oldest mcr-1 positive strain was isolated in May 2015, from a 1-year-old male infant. The second oldest strain was isolated in 2016. Three strains have been obtained in 2017, and one strain in 2018. Four patients suffering from infections with a mcr-1 positive strain were young children under 3 years, while the remaining two were isolated from elderly people (65 and 84 years old). All patients had symptoms of gastroenteritis, gastrointestinal dysfunction, or diarrhea. Among the six strains, five isolates (S304, S438, S441, S520, S585) belonged to S. Typhimurium/ST34 (O4:Hi), the remaining one (S530) to S. Indiana/ST17 (O4:Hz:H7).

TABLE 2.

Basic situation of mcr-1 positive strains.

| Strain | Inspection time | Specimen type | Patient age | Patient sex | Diagnosis of infection | Visiting department | Serovar | Serotype | AMR phenotype |

| S304 | 2015.5 | Stool | 1 | Male | Acute enteritis | Pediatrics | S. Typhimurium | O4:Hi: | COL, AMP, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, FOX, C, |

| S438 | 2016.12 | Stool | 3 | Male | Enteritis | Pediatrics | S. Typhimurium | O4:Hi: | COL, AMP, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, C |

| S441 | 2017.3 | Stool | 3 | Female | Infectious diarrhea | Pediatrics | S. Typhimurium | O4:Hi: | COL, AMP, CRO, AZM, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, FOX, C |

| S520 | 2017.9 | Stool | 1 | Female | Diarrhea | Pediatrics | S. Typhimurium | O4:Hi: | AMP, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, CIP, AK, C |

| S530 | 2017.1 | Stool | 84 | Female | Fracture, diarrhea | Recovery unit | S. Indiana | O4:Hz:H7 | AMP, CRO, AZM, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, CIP, AK, C |

| S585 | 2018.12 | Stool | 65 | Female | Gastrointestinal disorders | Recovery unit | S. Typhimurium | O4:Hi: | COL, AMP, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, C |

AMR, antimicrobial resistance; COL, colistin; AMP, ampicillin; CRO, ceftriaxone; AZM, aztreonam; FEP, cefepime; TET, tetracycline; AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanate; CTX, cefotaxime; FOX, cefoxitin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; AK, amikacin; IPM, imipenem; C, chloramphenicol; MEM, meropenem.

Drug Susceptibility of the mcr-1 Positive Strains

Clinical strains that show COL resistance are often resistant to several antibiotics. We therefore tested the susceptibility of the isolates that were mcr-1 positive toward several antibiotics applying the MIC standard values of the 2019 CLSI standard. The drug susceptibility results are shown in Table 2 and Supplementary Data Sheet 1. Surprisingly, only four of the six mcr-1 positive strains were resistant to COL in various degrees (three up to 32 μg/mL, one 4 μg/mL), while the two isolates S520 and S530 were not resistant to COL, indicating that their mcr-1 genes (or their regulation) might not be functional. All six strains displayed resistance to AMP, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, and chloramphenicol, but were not resistant to MEM nor IPM. With the exception of strains S441 and S530, four strains were sensitive to AZM. Two isolates, S304 and S441, were resistant to FOX, while the others were sensitive to the compound. Four strains were sensitive to AK, while two (S520 and S530) were resistant to the antibiotic. Strains S304 and S438 were sensitive, two intermediate (S441 and S585) and two (S520 and S530) were resistant to CIP. The results of our antibiotic susceptibility testing show that most strains that carry a COL resistant gene are also resistant to many other antibiotics, and can thus be considered multidrug resistant, making treatment challenging.

Genomic Location of mcr-1 in the Six Isolates

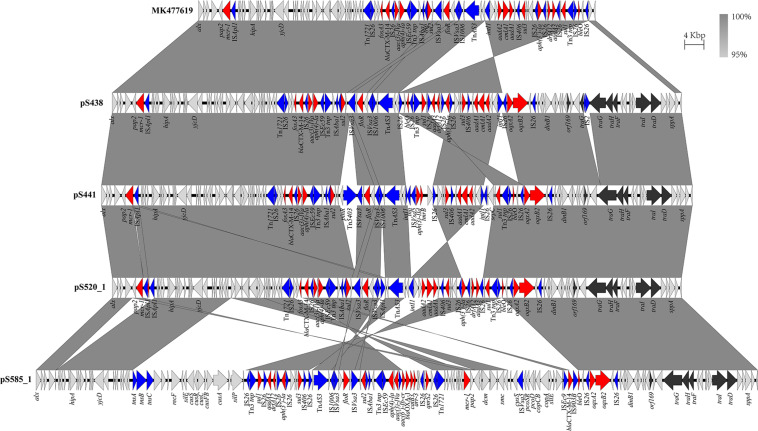

The genomic characteristics of the six isolates with regard to antimicrobial resistance are shown in Table 3. In four isolates (four S. Typhimurium), the mcr-1 gene was located on derivatives of an IncHI2 plasmid (∼253–284 kb). All four IncHI2 plasmids belonged to sequence type 3 and were similar to a number of IncHI2 plasmids of S. Typhimurium from different origins including animals, food, and humans (Supplementary Figure 2). The genetic context of the mcr-1 gene was relatively similar within these plasmids in three strains (S438, S441, S520), with the exception of strain S585. The mcr-1 gene in S585 was located in variable region of IncHI2 plasmid without being embedded in an IS. In addition to the mcr-1 gene, all four IncHI2 plasmids encoded other antibiotic resistance genes, including beta-lactam (blaCTX–M–14), aminoglycoside [aac(3)-IVa, aadA2, and aph(4)-Ia], sulphonamide (sul1, sul2, and sul3), phenicol (floR), quinolone (oqxAB), and fosfomycin (fosA3). A comparison of the plasmid sequences indicated many ISs and transposon insertion events, including ISApl1, IS186B, IS103, IS2, Tn5403. Furthermore, our analysis revealed that IS26 was responsible for a majority of inversion events (Figure 1). Plasmid pS438 contains 21 ISs, of which nine were IS26 copies, two ISVsa3 copies, two IS2 copies, and one copy each of ISKpn8, ISEc59, ISApl1, ISAba1, ISAba1, IS103, IS150, and IS1006, respectively. An inversion of ca 23 kb fragment of nine antibiotic resistance genes including aadA1, cmlA1, aadA1, and sul3 was observed in pS438 when compared to the pSH16G4918 (GenBank accession no. MK477619). In pS438, two copies of IS26 adjacent to the 23 kb fragment are in opposite orientation and are flanked by an identical 8-bp repeat inverted relative to each other. This inversion was caused by the intramolecular transposition in trans of IS26 into a target site.

TABLE 3.

The summary of the features associated with the genome and plasmid identified in Salmonella genomes.

| Sequence name | Size (bp) | ST type | Replicon Type (s) | Antibiotic resistance genes |

| S304 | 4,937,766 | ST34 | blaTEM–1B, blaTEM–1B, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, sul2, aac(6′)-Iaa, mdf(A) | |

| pS304-1 | 254,873 | IncHI2 IncHI2A | aadA2, cmlA1, ant(3″)-Ia, sul3, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, aph(3′)-Ia, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, blaTEM–1B, tet(A), qnrS1, ARR-3, cmlA1, blaOXA–10, ant(3″)-Ia, dfrA14, tet(A), floR, blaCTX–M–65 | |

| pS304_2 | 60.870 | IncI2 | mcr-1.1 | |

| pS304_3 | 7395 | ColRNAI | ||

| S441 | 4,944,769 | ST34 | tet(B), sul2, aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM–1B, qnrS1, blaCTX–M–55, aac(6′)-Iaa, mdf(A) | |

| pS441 | 260,707 | IncHI2 IncHI2A | mcr-1.1, fosA3, blaCTX–M–14, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, sul2, floR, aac(3)-IId, sul3, ant(3″)-Ia, cmlA1, aadA2, sul1, oqxA, oqxB | |

| S438 | 4,971,941 | ST34 | blaTEM–1B, aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, sul2, tet(B), aac(6′)-Iaa, floR, sul2, aph(4)-Ia, aac(3)-IVa, blaCTX–M–14, fosA3, mdf(A) | |

| pS438 | 253,817 | IncHI2 IncHI2A | mcr-1.1, fosA3, blaCTX–M–14, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, sul2, floR, sul1, aadA2, dfrA12, aph(3′)-Ia, sul3, ant(3″)-Ia, cmlA1, aadA2, oqxA, oqxB | |

| S520 | 5,038,289 | ST34 | aac(6′)-Iaa, mdf(A), tet(B), sul2, aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM–1B | |

| pS520 | 253,797 | IncHI2 IncHI2A | mcr-1.1, fosA3, blaCTX–M–14, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, sul2, floR, aadA2, cmlA1, ant(3″)-Ia, sul3, aph(3′)-Ia, dfrA12, aadA2, sul1, oqxA, oqxB | |

| S530 | 5,059,260 | ST17 | IncN IncQ1 | dfrA17, aadA5, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA–1, catB3, ARR-3, sul1, fosA3, blaCTX–M–14, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, sul2, floR, mcr-1.1, mph(A), sul3, tet(A), blaTEM–1B, sul2, aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, oqxA, oqxB, mph(E), msr(E), armA, sul1, ARR-3, catB3, blaOXA–1, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, aac(6′)-Iaa, mdf(A) |

| S585 | 5,024,322 | ST34 | mdf(A), aac(6′)-Iaa, tet(B), aph(6)-Id, aph(3″)-Ib, sul2 | |

| pS585_1 | 284,303 | IncHI2 IncHI2A | sul1, aadA2, dfrA12, aph(3′)-Ia, sul3, floR, sul2, aph(4)-Ia, aac(3)-IVa, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA–1, catB3, ARR-3, qnrS2, mcr-1.1, blaCTX–M–14, oqxA, oqxB | |

| pS585_2 | 6,079 | ColRNAI |

FIGURE 1.

Scaled, linear diagrams comparing the sequences of plasmid pSH16G4918 (GenBank no. MK477619), pS438, pS441, pS520, and pS585_1. Antibiotic resistance genes are indicated in red arrows. The individual conjugation-related genes are indicated with black arrows. Blue arrows denote transposon- and integron-associated genes. Other genes are shown as gray arrows.

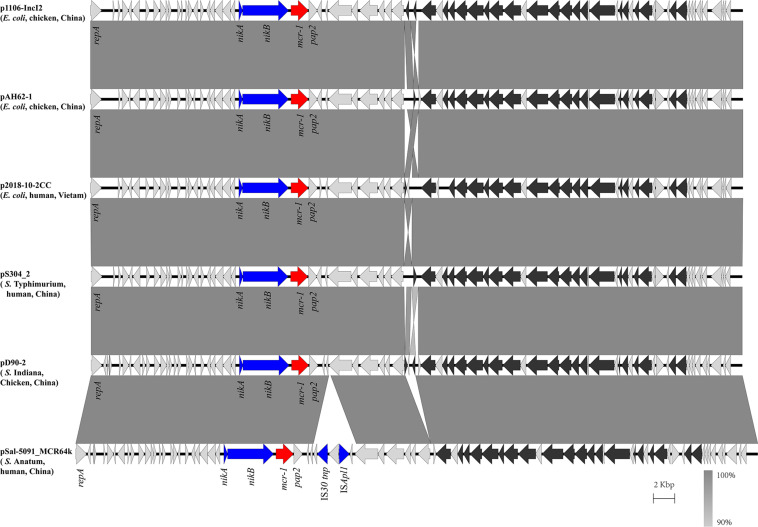

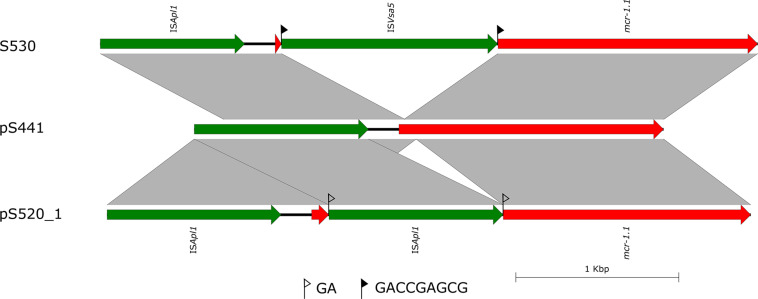

In the isolate S304 (a S. Typhimurium strain), the mcr-1 gene was located on IncI2 (60 kb), which was similar to a number of plasmids from different hosts, origins, and regions (Figure 2). The pS304_2 had the simplest mcr-1 transposon structure (mcr-1-pap2) without the assistance of the ISApl1 gene, as reported previously (Wang J. et al., 2017). These findings confirmed that IncI2-type plasmids have contributed to the successful spread of mcr-1 gene among species of different diverse genetic environments. Interestingly, in one isolate (S. Indiana), the mcr-1 gene was located in the chromosome. The COL-sensitive isolates S520 and S530 contained mcr-1 genes that were both disrupted by insertion elements. ISApl1 disrupted the mcr-1 gene in S520, while ISVsa5 inserted into the mcr-1 gene in S530, resulting in non-functional gene products. The identified tandem site duplications (TSDs) with the sequences GA and GACCGAGCG indicate the occurrence of an IS insertion (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Scaled, linear diagrams comparing the sequences between plasmid pS304_2, p1106-IncI2 (GenBank no. MG825374.1), pAH62-1 (GenBank no. CP055260.1), p2018-10-2CC (GenBank no. LC511622.1), pD90_2 (GenBank no. CP022452.1), and pSal-5091_MCR64k (GenBank no. CP045521.1). Antibiotic resistance genes are indicated in red arrows. The individual conjugation-related genes are indicated with black arrows. Blue arrows denote transposon- and integron-associated genes. Other genes are shown as gray arrows.

FIGURE 3.

Scaled, linear diagrams comparing the sequences of S530, plasmid pS441, and pS520_1. Insertion elements are shown as green arrows. Genes, including antibiotic resistance genes, are shown as labeled red arrows. Flags indicate the 8 bp target site duplications (TSDs).

Genetic Environment of the Chromosomal mcr-1

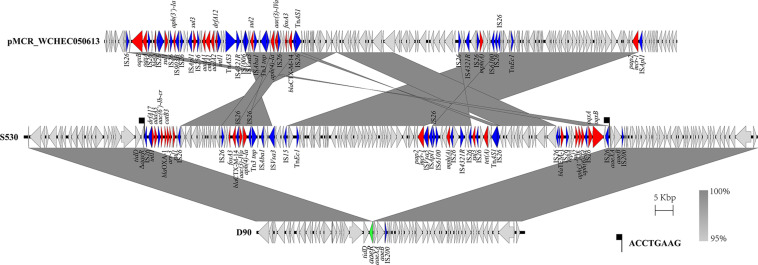

The genetic arrangement of chromosome-borne mcr-1 in S530 was investigated. The chromosomal mcr-1 was adjacent to ISApl1 and the pap2 gene, and they consisted of a “ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2” structure, which is commonly presented in chromosome-borne mcr-1 harbored strains (Peng et al., 2019). However, to our surprise, the IncN/IncQ1 replicon and repA gene were identified as a sequence surrounding the mcr-1 gene, indicating a plasmid origin. Bioinformatic analysis showed that a 129.85 kb mcr-1-carrying region inserted into the HTH-type transcriptional regulator protein encoding gene aaeR, compared with the genome of another S. Indiana/ST17 strain D90 (GenBank accession no. CP022450) (Figure 4). This region has a similar genetic environment compared with an IncN/IncHI2 plasmid pMCR_WCHEC050613 (GenBank accession no. CP019214), with 99.99% nucleotide identity at 86% coverage. In addition to the disrupted mcr-1 gene, this putative plasmid region also harbored multiple resistance genes including dfrA17, aadA5, aac(6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA–1, catB3, ARR-3, sul1, fosA3, blaCTX–M–14, aac(3)-IVa, aph(4)-Ia, sul2, floR, mph(A), sul3, tet(A), blaTEM–1B, sul2, aph(3″)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, oqxA, and oqxB (Table 3). Further sequence analysis showed that two copies of IS26 adjacent to the putative plasmid region in same orientation, were flanked by identical 8-bp TSDs (ACCTGAAG), indicating that IS26 is involved in the insertion of a mcr-1-carrying MDR plasmid into the S530 chromosome.

FIGURE 4.

Scaled, linear diagrams comparing the sequences between S530, D90 (GenBank no. CP022450), and pMCR_WCHEC050613 (GenBank no. CP019214). Antibiotic resistance genes are indicated in red arrows. The inserted gene aaeR is marked as the green arrow. Blue arrows denote transposon- and integron-associated genes. Other genes are shown as gray arrows.

Transfer Ability of the mcr-1-Harboring Plasmids

To evaluate the transferability of the mcr-1-harboring plasmids obtained in this study, conjugation experiments were performed. Transconjugants were obtained from each of the mixed cultures of the recipient E. coli J53 with one of the five mcr-1-positive strains. Four mcr-1-positive plasmids were successfully transferred from their hosts via conjugation. The result of antimicrobial susceptibility tests showed that all the positive transconjugants displayed elevated MICs to COL, CTX, and AMP, compared with that of E. coli J53 (Supplementary Table 1). It is important to state that since the IncI2 plasmid pS304_2 carried the only antimicrobial resistance mcr-1, the co-transferred resistance genes via the IncHI2 plasmid pS304_1 was able to confer the respective antibiotic resistance to the recipients. However, the mcr-1-harboring IncHI2 plasmid pS438 failed to transfer to the recipient E. coli J53, despite repeating the experiment several times. Further sequence analysis showed that pS438 possessed all the essential genes for mobility, but the transfer-related gene traG was disrupted by the insertion element IS2 (Figure 1), suggesting that the non-transferability of pS438 may be caused by the IS2 insertion into the traG gene.

Discussion

In 2016, the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture decreed to completely stop the use of COL in animal husbandry for promoting livestock growth and preventing disease (Walsh and Wu, 2016). However, the widespread use of COL in animal farming worldwide over the past decades has resulted in an increase of COL resistance and the spread of mcr-1. From 2013 to 2014, the detection rate of pathogenic E. coli mcr-1 in Japanese pigs was as high as 50% (Kusumoto et al., 2016) and up 21% in French cow dung samples from 2004 to 2014 (Haenni et al., 2016). These findings indicate that the misuse of antibiotics in the livestock industry will greatly increase the selection pressure of bacteria and provide evolutionary advantages for mcr-1 positive bacteria. As the clinical use of COL has been restricted in the past, the current rate of mcr-1 positive strains in clinical isolates and in healthy humans is much lower than that in samples that are obtained from farmed animals.

In our study, a total of 689 clinical Salmonella strains were screened which were isolated over the past 10 years. Only six of all strains (0.87%) were positive for the mcr-1 gene. The rate of occurrence of human-derived Enterobacteriaceae mcr-1 genes has been reported to be less than 2% (Yi et al., 2017a). Lu et al. (2019) collected 12,053 Salmonella isolates from a surveillance on diarrhoeal outpatients in Shanghai, China, 2006–2016, and 37 mcr-1-harboring strains were detected among them, in which 35 were serovar Typhimurium. In China, the most common ST of S. Typhimurium, especially MDR S. Typhimurium, is ST34, which is also prevalent in Europe (Antunes et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2013). In this study, all the five plasmid-mediated mcr-1-positive Salmonella strains belong to S. Typhimurium/ST34, suggesting that mcr-1-bearing plasmids might have a strong association with specific serotypes of Salmonella. Most of the S. Typhimurium/ST34 strains carrying mcr-1 gene were isolated from animals (Yi et al., 2017b), which suggests that the ST34 clone poses a great threat as it is able to disseminate COL resistance from food-producing animals to humans. While the antibiotic is still being used in agriculture (legally or illegally), the last-resort clinical deployment of COL for the treatment of MDR Gram-negative bacteria will lead to an increase in frequency of the mcr-1 gene, which can be easily transmitted by conjugation. This will aggravate the global antibiotic resistance crisis even further.

Wang Y. et al. (2017) conducted a retrospective analysis of risk factors such as infection, frequency of occurrence and fatality rates of infections by mcr-1 positive E. coli and K. pneumoniae in hospitals in Zhejiang and Guangdong, China. The results showed that the status of the immune system as well as the history of antibiotic use (especially carbapenem and fluoroquinolone) are risk factors for infection with mcr-1 positive strains. In our study, we found that four patients that were infected with mcr-1 positive strains were young children under 3 years, while the remaining two were 65 and 84 years old, being admitted to the hospital with symptoms of gastroenteritis, gastrointestinal disorders, or diarrhea. This indicated that age and low immune function may have certain effects on mcr-1 infection. However, due to the small number of patients and mcr-1 positive strains no statistically significant conclusion can be drawn.

The antimicrobial susceptibility test of the six mcr-1 positive strains showed that all strains are multidrug resistant, with resistance to many antibiotics, including AK, CRO, FEP, TET, AMC, CTX, and chloramphenicol. Interestingly, only four of the six mcr-1 positive strains displayed COL resistance. For the two COL-sensitive strains we identified inactive forms of mcr-1 due to insertion. It has previously been reported that the mcr-1 gene was inactivated by insertions of either IS10R or IS12984b (Terveer et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018). An inactivation of mcr-1 by an intragenic 22-bp duplication was described in an isolate of Shigella sonnei from Vietnam (Pham Thanh et al., 2016). In our study, we observed two inactive forms of the mcr-1 gene in Salmonella. The mcr-1 gene was disrupted by ISApl1 and ISVsa5, respectively. The strain S520 which harbored the mcr-1 gene with the insertion of ISApl1 was plasmid-encoded in the IncHI2 plasmid pS520_1. As the plasmid also encoded genes mediating resistance to several other antibiotics, the inactive mcr-1 gene might have been “carried along” on epidemic resistance plasmids. Interestingly, we found one chromosome-encoded mcr-1 in strain S530, which was, however, disrupted by ISVsa5. So far, a chromosome-embedded mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae has been rarely reported (Falgenhauer et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2019). Our bioinformatic analysis showed that the mcr-1 gene on the chromosome in strain S530 was flanked by ISApl1. Our finding corroborates the hypothesis that the insertion of the mcr-1 gene into the bacterial chromosome is mediated by ISApl1 (Peng et al., 2019). However, in our case, the chromosomal mcr-1 gene was found to be of plasmid origin. The putative mcr-1-carrying IncN/IncQ1plasmid was flanked by two copies of IS26 that mediated the integration into the aaeR gene of the S530. To the best of our knowledge, this study includes the first description of the mobilization of the mcr-1 gene into a chromosome mediated by a plasmid.

Our study showed that the mcr-1 gene was encoded by a variety of plasmids, among them IncI2, IncX4 and IncHI2 being the most predominant ones (Sun et al., 2018). Previously, the IncHI2/IncN replicon was reported to carry the mcr-1 gene, which indicates that the mcr-1 gene and its surrounding sequence might be derived from the IncHI2/IncN plasmid (Lu et al., 2020). In IncI2 plasmids, mcr-1-pap2 was the most common, whereas mcr-1 genes were usually flanked by ISApl1 (ISApl1-mcr-1-pap2 or Tn6330) in IncHI2 plasmids (Cao et al., 2020). This finding is also consistent with the results of our study, with the exception of pS585 that is not embedded in an IS. Although the total positive rate of mcr-1-harboring Salmonella strains in this study was revealed to be rather low, our conjugation experiments demonstrated that all the mcr-1-harboring plasmids are capable of transferring to E. coli, except the one plasmid in which traG was disrupted by IS2. This clearly illustrates the ability of Salmonella to spread these plasmids to diverse genera of the Enterobacteriaceae. The same, or highly similar, plasmids were also found in various host strains from different sources (animal, food, and humans) isolated in different regions, demonstrating the general applicability of our findings regarding the transfer abilities of the studied mcr-1-harboring plasmids among a pool of various microbes, including those that are animal and human pathogens.

Mobile genetic elements, particularly insertion sequence elements (ISs) are able to reorganize the sequence in plasmids. In this study, we observed several IS and transposon insertion events, including those mediated by ISApl1, IS186B, IS103, IS2, and Tn5403. Among all the ISs, IS26 seems to play a major role in the rapid dissemination of antibiotic resistance gene in Gram-negative bacteria (Harmer et al., 2014; He et al., 2015). Partridge et al. (2018) had previously shown that additional IS26 are easily acquired if the plasmid already possessed a copy of IS26. In our study, the insertion of one or more IS26 mediated several inversion events which involved a plethora of antibiotic resistance genes. IS26 copies lead to DNA sequence inversion via intramolecular replicative transposition in trans (He et al., 2015). This work, as well as our study, demonstrates the importance of replicative transposition in the reorganization of multiple antibiotic resistance plasmids.

In conclusion, we collected 689 clinical Salmonella strains and six of them (0.87%) were mcr-1-positive. Five strains harbored plasmid-encoded mcr-1 gene and the other one carried chromosomal mcr-1 gene originated from plasmid. Five plasmid-mediated mcr-1-positive Salmonella strains belong to S. Typhimurium/ST34 and carried mcr-1 via two types of plasmids (four IncHI2 plasmids and one IncI2 plasmid). The same or highly similar plasmids were also found in different sources (animal, food, and humans), suggesting that S. Typhimurium/ST34 is the potential reservoir for transmission of COL resistance and presents a potential public health threat. Active surveillance of mcr-1-harboring Salmonella, especially S. Typhimurium/ST34, should be further conducted due to the potential high risk of COL resistance development.

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequence of six mcr-1-positive Salmonella has been deposited in GenBank under accession number CP061115-CP061130.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hangzhou First People’s Hospital (2020103-1). Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

JF, YY, and XH designed the study. JF, LZ, JH, and MZ performed the experiments. XH, JH, SL, BL, and LZ analyzed the bioinformatics data. JF, JH, MZ, and XH wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Qingye Xu (Zhejiang University) for her kind assistance in experiments conducted in this study.

Funding. This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970128, 81861138054, 31770142, and 31670135), and the Zhejiang Province Medical Platform (2020RC075).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.604710/full#supplementary-material

References

- Al-Tawfiq J. A., Laxminarayan R., Mendelson M. (2017). How should we respond to the emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance in humans and animals? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 54 77–84. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes P., Mourao J., Pestana N., Peixe L. (2011). Leakage of emerging clinically relevant multidrug-resistant Salmonella clones from pig farms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 2028–2032. 10.1093/jac/dkr228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S., Brunel J. M., Dubus J. C., Reynaud-Gaubert M., Rolain J. M. (2012). Colistin: an update on the antibiotic of the 21st century. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 10 917–934. 10.1586/eri.12.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak M., Baumann B., Fischer J., Thomas K., Deneke C., Hammerl J. A., et al. (2020). Development of a Novel mcr-6 to mcr-9 Multiplex PCR and assessment of mcr-1 to mcr-9 occurrence in colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates from environment, feed, animals and food (2011-2018) in Germany. Front. Microbiol. 11:80. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak M., Hammerl J. A., Deneke C., Fischer J., Szabo I., Malorny B. (2019). Characterization of mcr-5-Harboring Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica Serovar typhimurium isolates from animal and food origin in Germany. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63:e0063-19. 10.1128/AAC.00063-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. P., Lin Q. Q., He W. Y., Wang J., Yi M. Y., Lv L. C., et al. (2020). Co-selection may explain the unexpectedly high prevalence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in a Chinese broiler farm. Zool. Res. 41 569–575. 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A., Carretto E., Brovarone F., Sarti M., Villa L. (2018). Comparative analysis of an mcr-4 Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica monophasic variant of human and animal origin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73 3332–3335. 10.1093/jac/dky340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll L. M., Gaballa A., Guldimann C., Sullivan G., Henderson L. O., Wiedmann M. (2019). Identification of novel mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-9 in a multidrug-resistant, colistin-susceptible Salmonella enterica Serotype typhimurium isolate. mBio 10:e00853-19. 10.1128/mBio.00853-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (2019). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, CLSI Supplement M100, 29th Edn, Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Zhang J., Zhang C., Li R., Wai-Chi Chan E., Wu C., et al. (2017). Distinct mechanisms of acquisition of mcr-1-bearing plasmid by Salmonella strains recovered from animals and food samples. Sci. Rep. 7:13199. 10.1038/s41598-017-01810-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falgenhauer L., Waezsada S. E., Gwozdzinski K., Ghosh H., Doijad S., Bunk B., et al. (2016). Chromosomal locations of mcr-1 and bla CTX-M-15 in fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli ST410. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22 1689–1691. 10.3201/eid2209.160692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S. L., Lynne A. M. (2008). Food animal-associated Salmonella challenges: pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance. J. Anim. Sci. 86(14 Suppl.), E173–E187. 10.2527/jas.2007-0447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Graells C., De Keersmaecker S. C. J., Vanneste K., Pochet B., Vermeersch K., Roosens N., et al. (2018). Detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance, mcr-1 and mcr-2 genes, in Salmonella spp. isolated from food at retail in Belgium from 2012 to 2015. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 15 114–117. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenni M., Poirel L., Kieffer N., Châtre P., Saras E., Métayer V., et al. (2016). Co-occurrence of extended spectrum β lactamase and MCR-1 encoding genes on plasmids. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 281–282. 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)00007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer C. J., Moran R. A., Hall R. M. (2014). Movement of IS26-associated antibiotic resistance genes occurs via a translocatable unit that includes a single IS26 and preferentially inserts adjacent to another IS26. mBio 5:e001801-14. 10.1128/mBio.01801-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S., Hickman A. B., Varani A. M., Siguier P., Chandler M., Dekker J. P., et al. (2015). Insertion sequence IS26 reorganizes plasmids in clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria by Replicative transposition. mBio 6:e00762. 10.1128/mBio.00762-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Liu F., Lin I. Y., Gao G. F., Zhu B. (2016). Dissemination of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 146–147. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00533-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X., Liang Q., He J., Wang M., Hong W., Wu J., et al. (2020). BacAnt: the combination annotation server of antibiotic resistance gene, insertion sequences, integron, transposable elements for bacterial DNA sequences. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.09.05.284273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumoto M., Ogura Y., Gotoh Y., Iwata T., Hayashi T., Akiba M. (2016). Colistin-resistant mcr-1-positive pathogenic Escherichia coli in Swine, Japan, 2007–2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 22 1315–1317. 10.3201/eid2207.160234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landman D., Georgescu C., Martin D. A., Quale J. (2008). Polymyxins revisited. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 449–465. 10.1128/CMR.00006-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-Y., Wang Y., Walsh T. R., Yi L.-X., Zhang R., Spencer J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 161–168. 10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00424-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokken K. L., Walker G. T., Tsolis R. M. (2016). Disseminated infections with antibiotic-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strains: contributions of host and pathogen factors. Pathog. Dis. 74:ftw103. 10.1093/femspd/ftw103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Leon A., Garcia-Omil C., Dalama J., Rodriguez-Souto R., Martinez-Urtaza J., Gonzalez-Escalona N. (2019). Detection of colistin resistance mcr-1 gene in Salmonella enterica serovar Rissen isolated from mussels, Spain, 2012- to 2016. Euro Surveill. 24:1900200. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.16.1900200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Dong N., Liu C., Zeng Y., Sun Q., Zhou H., et al. (2020). Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae in healthy adults from China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75 2485–2494. 10.1093/jac/dkaa210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Zeng M., Xu J., Zhou H., Gu B., Li Z., et al. (2019). Epidemiologic and genomic insights on mcr-1-harbouring Salmonella from diarrhoeal outpatients in Shanghai, China, 2006–2016. eBio Med. 42 133–144. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation R. L., Li J. (2009). Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22 535–543. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328332e672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge S. R., Kwong S. M., Firth N., Jensen S. O. (2018). Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31:e0088-17. 10.1128/cmr.00088-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Hu Z., Li Z., Li X., Jia C., Zhang X., et al. (2019). Characteristics of a colistin-resistant Escherichia coli ST695 harboring the chromosomally-encoded mcr-1 GENE. Microorganisms 7:558. 10.3390/microorganisms7110558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham Thanh D., Thanh Tuyen H., Nguyen Thi Nguyen T., Chung The H., Wick R. R., Thwaites G. E., et al. (2016). Inducible colistin resistance via a disrupted plasmid-borne mcr-1 gene in a 2008 vietnamese Shigella sonnei isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 2314–2317. 10.1093/jac/dkw173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan J., Li X., Chen Y., Jiang Y., Zhou Z., Zhang H., et al. (2017). Prevalence of mcr-1 in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae recovered from bloodstream infections in China: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17 400–410. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30528-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Johnson A. P. (2016). Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 2066–2070. 10.1093/jac/dkw274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Zhang R., Schwarz S., Wu C., Shen J., Walsh T. R., et al. (2020). Farm animals and aquaculture: significant reservoirs of mobile colistin resistance genes. Environ. Microbiol. 22 2469–2484. 10.1111/1462-2920.14961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. J., Petty N. K., Beatson S. A. (2011). Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27 1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Zhang H., Liu Y. H., Feng Y. (2018). Towards understanding MCR-like colistin resistance. Trends Microbiol. 26 794–808. 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R. Y., Ke B. X., Fang L. X., Guo W. Y., Li X. P., Yu Y., et al. (2020). Global clonal spread of mcr-3-carrying MDR ST34 Salmonella enterica Serotype typhimurium and monophasic 1,4,[5],12:i:- variants from clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75 1756–1765. 10.1093/jac/dkaa115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambadou F., Caradec T., Gagez A. L., Bonnet A., Sopena V., Bridiau N., et al. (2015). Characterization of the colistin (polymyxin E1 and E2) biosynthetic gene cluster. Arch. Microbiol. 197 521–532. 10.1007/s00203-015-1084-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terveer E. M., Nijhuis R. H. T., Crobach M. J. T., Knetsch C. W., Veldkamp K. E., Gooskens J., et al. (2017). Prevalence of colistin resistance gene (mcr-1) containing Enterobacteriaceae in feces of patients attending a tertiary care hospital and detection of a mcr-1 containing, colistin susceptible E. coli. PLoS One 12:e0178598. 10.1371/journal.pone.0178598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T. R., Wu Y. (2016). China bans colistin as a feed additive for animals. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16 1102–1103. 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)30329-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li X., Li J., Hurley D., Bai X., Yu Z., et al. (2017). Complete genetic analysis of a Salmonella enterica serovar Indiana isolate accompanying four plasmids carrying mcr-1, ESBL and other resistance genes in China. Vet. Microbiol. 210 142–146. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Tian G.-B., Zhang R., Shen Y., Tyrrell J. M., Huang X., et al. (2017). Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17 390–399. 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)30527-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Fu Y., Schwarz S., Yin W., Walsh T. R., Zhou Y., et al. (2019). Genetic environment of colistin resistance genes mcr-1 and mcr-3 in Escherichia coli from one pig farm in China. Vet. Microbiol. 230 56–61. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick R. R., Judd L. M., Gorrie C. L., Holt K. E. (2017). Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005595. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. H., Yan M., Chan E. W., Liu L. Z., Kan B., Chen S. (2013). Expansion of Salmonella enterica Serovar typhimurium ST34 clone carrying multiple resistance determinants in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 4599–4601. 10.1128/AAC.01174-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L., Liu Y., Wu R., Liang Z., Liu J. H. (2017a). Research progress on the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1. Hereditas 39 110–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L., Wang J., Gao Y., Liu Y., Doi Y., Wu R., et al. (2017b). mcr-1-Harboring Salmonella enterica Serovar typhimurium sequence Type 34 in Pigs, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23 291–295. 10.3201/eid2302.161543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E., Hasman H., Cosentino S., Vestergaard M., Rasmussen S., Lund O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Zhang B., Guo Y., Wang J., Zhao P., Liu J., et al. (2019). Colistin resistance prevalence in Escherichia coli from domestic animals in intensive breeding farms of Jiangsu Province. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 291 87–90. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K., Luo Q., Wang Q., Huang C., Lu H., Rossen J. W. A., et al. (2018). Silent transmission of an IS1294b-deactivated mcr-1 gene with inducible colistin resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51 822–828. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The complete genome sequence of six mcr-1-positive Salmonella has been deposited in GenBank under accession number CP061115-CP061130.