Abstract

Rice-based cropping systems are the most energy-intensive production systems in South Asia. Sustainability of the rice-based cropping systems is nowadays questioned with declining natural resource base, soil degradation, environmental pollution, and declining factor productivity. As a consequence, the search for energy and resource conservation agro-techniques is increasing for sustainable and cleaner production. Conservation agriculture (CA) practices have been recommended for resource conservation, soil health restoration and sustaining crop productivity. The present study aimed to assess the different CA modules in rice-based cropping systems for energy conservation, energy productivity, and to define energy-economic relations. A field experiment consisted of four different tillage-based crop establishment practices (puddled-transplanted rice followed by (fb) conventional-till maize/wheat (CTTPR-CT), non-puddled transplanted rice fb zero-till maize/wheat (NPTPR-ZT), zero-till transplanted rice fb zero-till maize/wheat (ZTTPR-ZT), zero-till direct-seeded rice fb zero-till maize/wheat (ZTDSR-ZT)), with two residue management treatments (residue removal, residue retention) in rice–wheat and rice–maize rotations were evaluated for energy budgeting and energy-economic relations. Conservation-tillage treatments (NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT) reduced the energy requirements over conventional tillage treatments, with the greater reduction in ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT treatments. Savings of energy in conservation-tillage treatments were attributed to reduced energy use in land preparation (69–100%) and irrigation (23–27%), which consumed a large amount of fuel energy. Conservation-tillage treatments increased grain and straw/stover yields of crops, eventually increased the output energy (6–16%), net energy (14–26%), energy ratio (25–33%), and energy productivity (23–34%) as compared with CTTPR-CT. For these energy parameters, the treatment order was ZTDSR-ZT ≥ ZTTPR-ZT > NPTPR-ZT > CTTPR-CT (p < 0.05). Crop residue retention reduced net energy, energy ratio, and energy productivity when compared with residue removal. Our results of energy-economic relations favored the “conservative hypothesis,” which envisages that energy and monetary investments are not essentially the determinants of crop productivity. Thus, zero tillage-based crop establishments (ZTTPR-ZT, ZTDSR-ZT) in rice-based production systems could be the sustainable alternative to conventional tillage-based agriculture (CTTPR-CT) as they conserved non-renewable energy sources, reduced water requirement, and increased crop productivity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11356-020-10395-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Conservation agriculture, Crop residue retention, Crop establishment, Direct seeded rice, Energy budgeting, Rice/maize/wheat system

Introduction

The agriculture sector of developing countries has witnessed spectacular progress in farm mechanization that markedly increased the energy inflows in agriculture (Saad et al. 2016; Choudhary et al. 2017). The scale of energy investment and accessible resource base primarily determine the crop productivity and production economics (Shahbaz et al. 2017). Nevertheless, energy and input-intensive production systems have several sustainability concerns (Kumar et al. 2020). Conservation of non-renewable energy sources and efficient resource management in agriculture is increasingly being realized for cleaner and sustainable production (Kumar et al. 2019). So, there is an increased need for developing alternative agro-technique(s) that can substantially reduce the energy requirements in crop production (Saad et al. 2016). The dominated energy concept, i.e., increased energy investments cause higher crop productivity and economic growth (Ouedraogo 2013; Aslan et al. 2014), is contrasted by the “conservative hypothesis” (Narayan 2016; Kasman and Duman 2015). The energy use in crop production, economics, and the environment in a given agro-ecosystem are strongly interrelated, and thus a holistic approach must be adopted to address the evident challenges of energy-intensive production systems (Pimentel et al. 1994).

The increasing scarcity of human labor has increased the pressure for the adoption of the machine-driven operations like tillage, sowing/transplanting, harvesting, and threshing (Jat et al. 2013). The adverse impact of mechanization and input-intensive agricultural practices on soil quality and environmental pollution are becoming the major current concerns (Parihar et al. 2018), demonstrating the need for developing alternative crop management strategies that could minimize the energy use, protect the environment, and maintain comparable or even higher crop productivity over current practices. For such strategic change in production techniques targeting to elevate energy productivity, a detailed input–output energy budgeting is the prerequisite (Tuti et al. 2012).

Rice-based cropping systems are predominant in South Asia (Hazra et al. 2018). The rice–wheat cropping system is extensively being practiced in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP) region (~ 11.7 m ha) and contributes a major share of the national food-grain production (Chauhan et al. 2012; Nandan et al. 2018a). However, conventional rice-based cropping systems are mostly input and energy intensive (Hazra et al. 2019). Land preparation/tillage, wet-tillage (puddling), high rate of fertilizers, and frequent irrigation to maintain standing water during the rice crop season consume a large amount of the energy sources (Nandan et al. 2018b; Lal et al. 2019). Meanwhile, the sustainability of the rice-based cropping systems are primarily threatened by depletion of groundwater level, deterioration of soil health and soil native fertility, declining factor productivity, and environmental pollution due to intensive tillage operations and inappropriate agronomic practices (Nath et al. 2019).

Conservation agriculture (CA), which is nowadays gaining a larger interest in South Asia, offers strategic options to upscale the resource and energy productivity (Kumar et al. 2019a). The benefits of CA over conventional agriculture on soil health (Gathala et al. 2015; Devkota et al. 2019), resource conservation (Nandan et al. 2018b), and ecosystem services (Alam et al. 2019) have already been reported from the tropical IGP regions. However, very limited reports are available on the impact of recently developed CA modules in the rice–wheat or rice–maize cropping systems on energy inflow–outflow balance. The recent developments of conservation tillage cum crop establishment practices in the lowland rice ecologies like non-puddled transplanting of rice (NPTPR), zero-tillage transplanting (ZTTPR), and zero-tillage direct seeding of rice (ZTDSR) fits in the rice-based cropping systems in CA mode. In the present study, the energy budgeting and energy-economic relationship was evaluated in two rice-based cropping systems (rice–wheat and rice–maize) of the IGP region that consisted of different tillage-based crop establishment methods and residue management treatments. The objectives of the study were (1) to assess the scale of energy conservation of different CA modules over conventional practices in rice-based cropping systems, (2) to estimate operation-wise and source-wise energy inflow and energy productivity under different CA modules in rice-based systems, and (3) to derive the association between different energy parameters and production economics variables to define the energy-economic relations.

Materials and methods

Site and soil characteristics

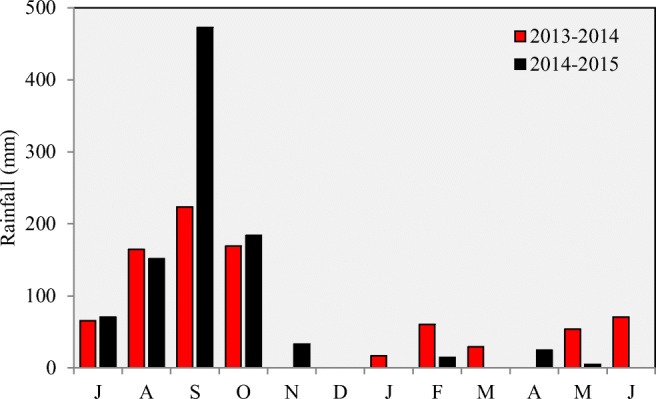

The field experiment was initiated in the year 2009 at the research farm of Indian council of Agricultural Research- Research Complex for Eastern Region (ICAR–RCER), Patna, Bihar (25°37′ N, 85°13′ E and 36 m above sea level). The climate of the region is subtropical–humid. The soil is clay-loam in texture and comes under the taxonomical class Fluvisol (World Reference Base soil classification). The site receives 1130 mm of annual rainfall, and 85–90% of the rainfall occurs during June to September. The month-wise rainfall during the study period (2013–2015) is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Monthly rainfall (mm) received during the experimental year 2013–2014 and 2014–2015

Treatment details and experimental design

Treatments comprised two crop rotations (rice (Oryza sativa L)–wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and rice–maize (Zea mays L.)), two residue management treatments (residue removal and residue retention (~33%)), and four crop establishment/tillage treatments (puddled transplanting of rice followed by conventional tillage in wheat/maize (CTTPR-CT), non-puddled transplanting of rice followed by zero tillage (ZT) in wheat/maize (NPTPR-ZT), zero tillage transplanting of rice followed by zero tillage in wheat/maize (ZTTPR-ZT), and zero tillage direct seeded rice followed by zero tillage in wheat/maize (ZTDSR-ZT)). In CTTPR-CT treatment, the field was prepared with two plowing, two harrowing, one wet-tillage (puddling), and planking, and 21-day-old rice seedlings (2 seedlings hill−1) were manually transplanted (20 cm × 15 cm); for winter crops (wheat/maize), the field was conventionally tilled (two plowing, two harrowing, planking) and wheat crop was established by broadcasting, where maize was manually dibbled. In NPTPR-ZT treatment, the field was prepared by two plowing, two harrowing, and planking (no wet-tillage); rice transplanting was done in the same way as CTTPR-CT; wheat and maize crops were sown in zero-tillage condition using zero-till happy-seeder machine. In ZTTPR-ZT plots, no tillage operation was performed, and a day before rice transplanting, the plots were flooded to make the soil soft and rice was transplanted in the same way as CTTPR-CT; wheat and maize crops were sown in zero-tillage condition using zero-till happy-seeder machine. In ZTDSR-ZT treatment, direct seeding of rice was done using zero-till seed cum fertilizer drill in zero-till flat plots at 20-cm row spacing; wheat and maize crops were sown in zero-tillage condition using zero-till happy-seeder machine. In residue retention treatment, the rice and wheat crops were harvested at a height of ~ 30 cm by the combine harvester and maize was harvested at a height of ~ 70 cm to retain approximately 33% of crop residue in the field, whereas in residue removal plots, all the crops were harvested from the ground. The treatments were laid out in split-split-plot design, accommodating crop rotation, residue management, and crop establishment treatments in the main plot, subplot and sub-subplot, respectively, and the treatments were replicated thrice. The dimension of each sub-subplot was 10.5 × 7.5 m.

Crop management

In ZTDSR-ZT treatment, rice (hybrid ‘Arize Tez’) was directly sown in the main field in zero-till condition using zero-till multi-crop planter. On the same day, rice nursery (bed size 12 × 6 m) was raised. The nursery area was plowed and puddled before sowing. Rice seeds were soaked in water and placed in a gunny bag overnight. The pre-germinated seeds were then uniformly broadcasted and watered at regular intervals. The nursery bed was submerged with a shallow layer of water after a week of sowing. In CTTPR-CT, NPTPR-ZT, and ZTTPR-ZT treatments, 21-day old seedlings were transplanted manually by human labor. A plant spacing of 20 × 15 cm was maintained in all the transplanted rice treatments. For rice crop, the fertilizer N/P2O5/K2O was applied at 120:40:20 kg ha−1. Half dose of nitrogen (N) and the full dose of phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) along with 25 kg ha−1 zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) and 20 kg ha−1 sulfur were applied as a basal dose. The remaining half dose of N was applied in two equal splits at active tillering and panicle initiation stages. In ZTDSR-ZT treatment, 18% of N and the full dose of P and K along with 25 kg ha−1 zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) and 20 kg ha−1 sulfur were applied basal and the remaining N (82%) was top-dressed in three equal splits at 15 days after sowing (DAS), active tillering, and panicle initiation stage. Irrigation was applied to rice crop based on the crop requirements for different tillage regimes and rainfall received during the crop season (Fig. 1). For weed control in rice crop, pretilachlor (50% EC) 0.4 kg a.i. ha−1 was applied in CTTPR-CT and NPTPR-ZT treatments within 24 h of transplanting without applying any post-emergence herbicides. Pretilachlor was applied at saturated soil condition after draining the water after transplanting. Within 24 h of herbicide application, plots were filled with water to achieve better efficacy of herbicide, whereas in ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT treatments, pre-emergence application of pendimethalin (30% EC) 0.75 kg a.i. ha−1 within 2 days of sowing/transplanting followed by post-emergence application of bispyribac sodium (10% SC) at 20 g a.i. ha−1 at 25 days of sowing/transplanting were undertaken. For insect pest management in rice, two sprays of imidacloprid was performed.

Wheat (cv. HD 2967) and maize (cv. ‘Decalb 9120’) were sown during the second fortnight of November. The wheat crop was sown by manually broadcasting in CTTPR-CT treatment, and in the zero-tillage treatments (NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT), the crop was sown by zero-till happy-seeder machine maintaining an inter-row spacing of 22.5 cm. Likewise, in CTTPR-CT treatment, maize was sown by manual dibbling method, and in zero-tillage treatments, the crop was sown by zero-till happy-seeder machine with a plant spacing of 60 × 15 cm. Both wheat and maize seeds were treated with systemic insecticide imidacloprid at 7 g kg−1 seeds. The fertilizers dose of N/P2O5/K2O at 120:60:40 kg ha−1 were applied to the wheat crop. Half of the total amount of N and full doses of P and K were applied at the time of sowing. The remaining dose of N was applied in the form of urea in two equal splits after first (21 DAS) and second (50 DAS) irrigation. Likewise, 150:75:50 kg ha−1 of N/P2O5/K2O was supplied to maize crop; half quantity of N and full doses of P and K were applied at the time of sowing. The remaining dose of N was applied in two equal split doses after 60 DAS and taselling time. In addition to the N, P, and K fertilizers, 25 kg ha−1 zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) and 20 kg ha−1 sulfur were applied as basal dose to both wheat and maize crops. Before the sowing of wheat and maize crop, pre-plant application of glyphosate (41% SL) 1.5 kg a.i. ha−1 was applied in NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT treatments. After that, post-emergence application of ready mix herbicide sulfosulfuron (75% WG) + metsulfuron (5% WG) at 32 g a.i. ha−1 was applied to wheat crop irrespective of tillage treatments at 25 DAS. In maize crop, post-emergence application of atrazine (50% WP) 1.25 kg ha−1 at 25 DAS was applied irrespective of treatments. Herbicides were applied with knapsack sprayer fitted with flat-fat nozzle with 400 l ha−1 water. A total of six irrigations were applied to wheat crop (crown root initiation, active tillering, booting, flowering, dough stages), where, in maize crop, a total of five irrigations were applied at different crop growth stages (20–25 days interval). The total depth of irrigation applied to the rice, wheat, and maize crop in different treatment is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Seed rate, tillage type and frequency, fertilizer N splits, total irrigation depth, and weed control measures for the component crops under different tillage cum crop establishment treatments

| Treatment | Seed rate (kg ha−1) | Tillage (n) |

N split (n) |

Irrigation depth (cm)$ | Hand weeding (n) | Pre-emergence/sowing herbicide | Post-emergence herbicide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT | H | P | WT | ||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | Rice | 15 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 390 | – | Pretilachlor | – |

| Wheat | 120 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | 3 | 90 | – | – | Sulfosulfuron + metsulfuron | |

| Maize | 20 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | 3 | 75 | – | – | Atrazine | |

| NPTPR-ZT | Rice | 15 | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | 3 | 260 | – | Pretilachlor | – |

| Wheat | 100 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 90 | – | Glyphosate | Sulfosulfuron + metsulfuron# | |

| Maize | 20 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 75 | – | Glyphosate | Atrazine | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | Rice | 15 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 260 | – | Pendimethalin | Bispyribac Na |

| Wheat | 100 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 90 | – | Glyphosate | Sulfosulfuron + metsulfuron | |

| Maize | 20 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 75 | – | Glyphosate | Atrazine | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | Rice | 25 | – | – | – | – | 4 | 280 | 1–2* | Pendimethalin | Bispyribac Na |

| Wheat | 100 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 90 | – | Glyphosate | Sulfosulfuron + metsulfuron | |

| Maize | 20 | – | – | – | – | 3 | 75 | – | Glyphosate | Atrazine | |

PT preparatory tillage, H harrowing, P plowing, WT wet-tillage (puddling)

$Average value of 2 years (2013–2014 and 2014–2015)

*Hand weeding was done in ZTDSR-ZT due to higher weed growth

#Ready-mix herbicide 75% sulfosulfuron + 5% WG metsulfuron

Grain and straw yield estimation

To estimate the grain and straw/stover yields of component crops, a net plot area of 3 × 3 m was manually harvested, threshed, and weighed. Then, a subsample of the harvested grain was used for estimation of moisture content. The grain yield of all the component crops was adjusted at 14% moisture content (w/w).

Energy calculation and budgeting

The study aimed to compare the conventional and CA-based practices on energy parameters in the fourth and fifth year of crop rotations, i.e., year 2013–2014 and 2014–2015. The energy input–output relationship in different crop production systems was derived and energy inflow–outflow budgeting was done. The different sources of energy in crop production were computed based on the input requirement and their corresponding energy coefficient given in Table 2. According to Devasenapathy et al., the energy sources are primarily classified into two categories, namely, direct and indirect energy sources (Devasenapathy et al. 2009). In the present study, direct energy sources including diesel, tractors, and stationary motors animate power (human and animal). Besides this, rain, wind, solar radiation, and so on are also listed under direct energy sources, but in the present study, these energy sources are not taken into account. On the other hand, indirect energy sources are those which do not release energy directly but dissipate energy during various conversion processes (Saad et al. 2016). The energy required in manufacturing, storage, and transportation activities contributes to the indirect energy calculation. For the present study, seeds, crop residues, fertilizers, chemicals, and machinery are categorized under the sources of indirect energy. Following the guidelines of earlier studies, the nutrient removal by crop(s) and energy involved in the changes in soil organic carbon was not considered in the present study.

Table 2.

Energy coefficient of different energy sources used in the study

| Particular | Unit | Energy coefficient (MJ unit−1) | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Prime movers | (tractor, 5-hp motor) | kg | 64.8 | Devasenapathy et al. (2009) |

| Farm machinery | (disc harrow, cultivator, seed drill, dehusker-cum-sheller, sprayer) | kg | 62.7 | Devasenapathy et al. (2009) | |

| Combine harvester | kg | 83.5 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008) | ||

| Diesel including lubricant | l | 56.31 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Chaudhary et al. (2009) | ||

| Irrigation water | m3 | 1.02 | Azarpour (2012) | ||

| Human power | Adult man | Man-hour | 1.96 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Chaudhary et al. (2009) | |

| Adult woman | Woman-hour | 1.57 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009) | ||

| Chemical fertilizer | N fertilizer | kg | 60.6 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Tuti et al. (2012) | |

| P2O5 fertilizer | kg | 11.1 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Tuti et al. (2012) | ||

| K2O fertilizer | kg | 6.7 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Tuti et al. (2012) | ||

| Superior chemical | Granular | kg | 120 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008, 2009); Chaudhary et al. (2009) | |

| Liquid | ml | 0.102 | Chaudhary et al. (2009); Devasenapathy et al. (2009) | ||

| Output | Main product | Rice grain | kg | 15.1 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008) |

| Maize grain | kg | 15.7 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008) | ||

| Wheat grain | kg | 15.1 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008) | ||

| By-product | Straw/stover | kg | 12.5 | Devasenapathy et al. (2008) | |

All the energy sources were converted to energy unit of megajoule (MJ). The primary data on various inputs and agronomic operations during the cropping years 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 were used for estimation of energy calculation. Energy coefficients are used as the standard conversion factors for calculation of energy content in a compound or potential to perform a work by different sources. For calculation of energy investment in the form of man-day or woman-day hour, their values were multiplied by the energy coefficient 1.96 and 1.57 MJ per hour, respectively. As a standard assessment, 1 man-day is equivalent to 0.8 woman-day. Energy coefficient in grains or crop biomass is the total calorific value of carbohydrate, protein, and fat content per unit mass. The energy coefficients (Table 2) from various available literature of each item were adopted (Devasenapathy et al. 2009; Tuti et al. 2012; Saad et al. 2016; Choudhary et al. 2017) to estimate input and output energy (expressed as MJ ha−1).

Energy equivalents of all inputs were summed to get an estimate for the total input energy. Energy utilization in farm operations was calculated based on energy consumed in land preparation, sowing or transplanting, fertilizer management, irrigation, intercultural operation, plant protection, harvesting, and threshing. The source-wise renewable and non-renewable energy under direct and indirect energies of inputs were also calculated, namely, human labor, water, seed, crop residue, diesel, agrochemicals (pesticides and herbicides), fertilizers, and machinery. The grain and straw/stover yields of rice, maize, and wheat crops and their equivalent yields were converted in terms of energy (MJ ha−1) using corresponding energy coefficients given in Table 2.

Calculation of energy indices

Output energy, defined as the sum grain and straw/stover energy equivalents, was calculated by the following formula

| 1 |

An accounting approach is used to analyze some basic measures of input–output energy relation like net energy return, energy ratio, and energy productivity (Devasenapathy et al. 2009; Tuti et al. 2012; Choudhary et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2019b). Net energy return, defined as the difference between the total output energy produced and total input energy required, was calculated using the following formula:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

Economic analysis

The economic analysis of each treatment was calculated based on the prevailing market price of all the inputs and outputs. For the present study, the variable cost of cultivation includes tillage operations, seed rate, machinery, transplanting/sowing operations, human labor, plant protection chemicals, irrigation, harvesting, and threshing. All the costs (both fixed and variable cost) were then summed up to estimate the cost of cultivation, and this is expressed in Indian national rupee per hectare basis (INR ha−1). The grain yields of the component crops were converted to monetary value using the minimum support price (MSP), Government of India for the year. Likewise, the economic return from the straw/stover outputs was calculated based on the regional market price and quantity of straw/stover outputs under different treatments. Then, the total monetary return from grain and straw was summed up to estimate the gross return. The net returns were calculated as the difference between gross returns and total variable cost. The benefit–cost ratio (BCR) was estimated by dividing net returns with total variable cost.

Statistical analysis

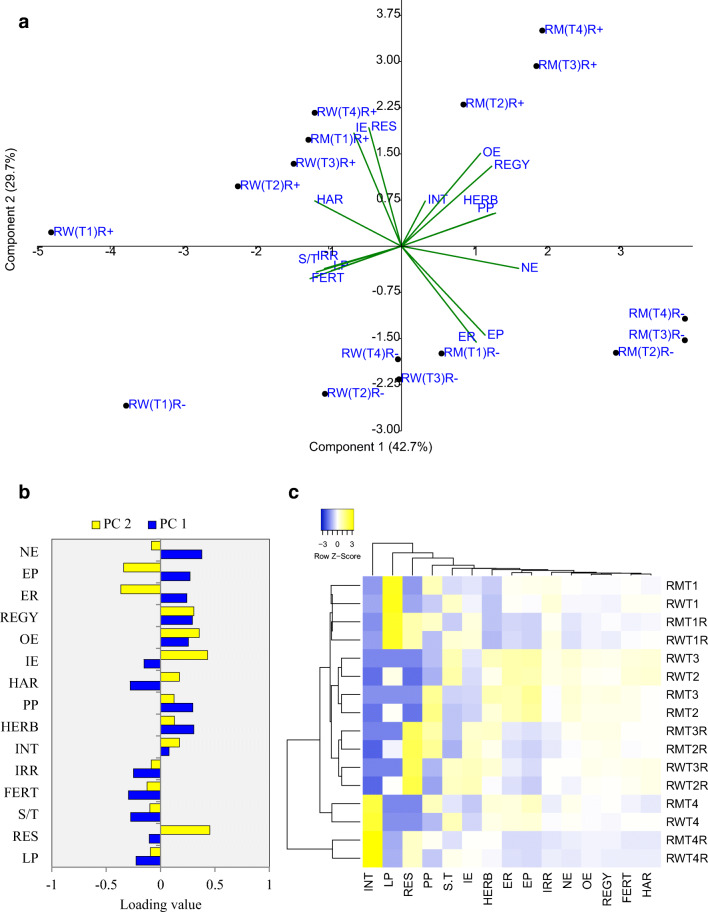

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) of split-split-plot design using online statistical program OPSTAT (Sheoran et al. 1998). Statistical analysis was performed for the parameters namely output energy, net energy, and energy ratio and energy productivity only. However, for input energy components, no statistical analysis was done as these parameters did not vary within replications. The least significant difference (LSD) was calculated at α = 0.05 and used for comparison of treatments means. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done in Window-based software PAST 3.14. Heat map presentation with cluster analysis was done using Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping tool (Babicki et al. 2016).

Results

Energy inputs

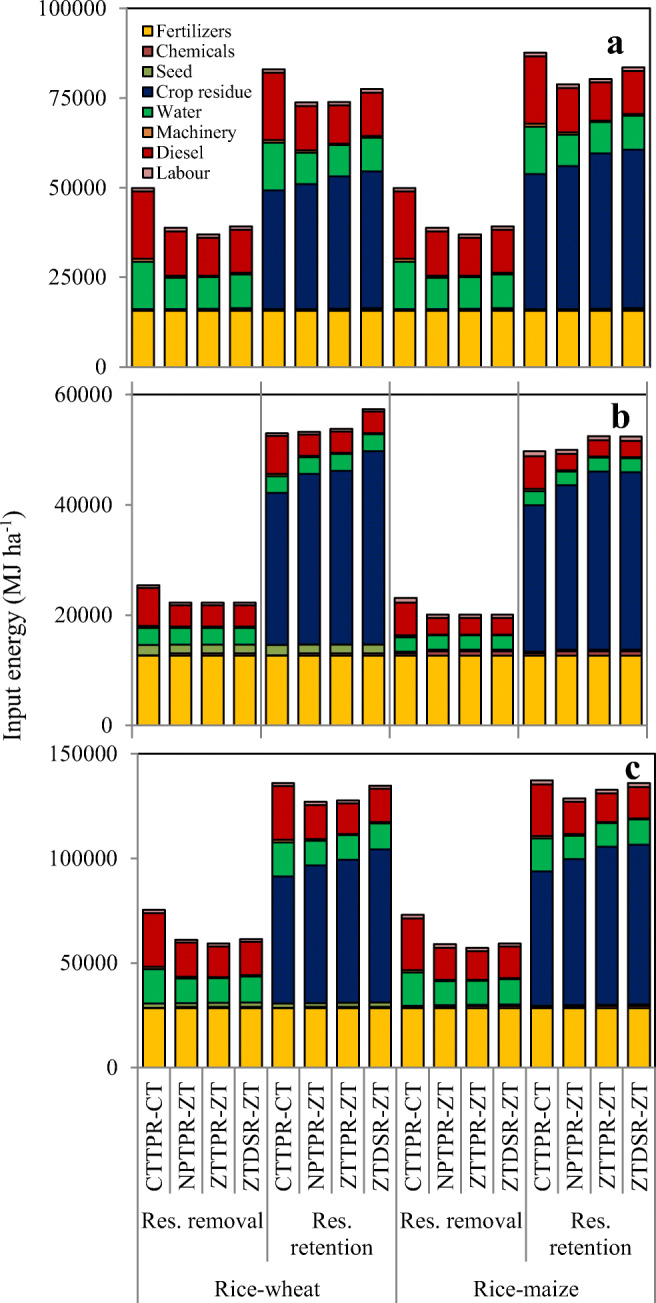

The total energy investment in rice cultivation was markedly higher than wheat and maize cultivation (Fig. 2). The total energy use in rice crop was 38 and 36% higher over wheat and maize crops. Among the different sources of energy, diesel, fertilizers, irrigation, and crop residue (in residue retention treatments) together accounted for 96% of total energy input in rice cultivation. Crop residue was the primary bio-energy input component in residue retention treatments. On average, the residue retention increased the energy use (75% higher) over residue removal treatment (Table 3). Conservation tillage treatments (NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT) reduced the energy input for irrigation (29–34%), diesel (34–43%), and machinery (31–52%) compared with conventional tillage practice (CTTPR-CT) (Fig. 2). Subsequently, the saving of total input energy in NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT treatments was 16, 18, and 13%, respectively, as compared with CTTPR-CT treatment (Table 3). Likewise, the operation-wise energy use pattern revealed that in rice crop, higher energy requiring operations were crop residue management followed by irrigation (Table 3). Conservation tillage treatments reduced energy use in land preparation (1264–3272 MJ ha−1), irrigation (8314–9843 MJ ha−1), and increased the energy input through crop residue (1029–2896 MJ ha−1) as compared with conventional tillage-based agriculture (CTTPR-CT).

Fig. 2.

Source-wise input energy (MJ ha−1) components in rainy season rice crop (a), winter season wheat/maize crop (b), and rice–maize/wheat system (c) under different treatments. The values are the mean of 2 years (2013–2014 and 2014–2015)

Table 3.

Operation-wise energy use (MJ ha−1) in rice crop as influenced by cropping system, residue management, and TCE practices (2-year mean)

| Treatment | Land preparation | Residue management | Sowing/transplanting | Fertilizer management | Irrigation | Inter-culture | Chemical weed management | Plant protection | Harvest/threshing | Total input energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MJ ha−1) | ||||||||||

| Cropping system | ||||||||||

| Rice–wheat | 1320 | 17,878 | 653 | 15,764 | 22,723 | 53 | 243 | 68 | 450 | 59,152 |

| Rice–maize | 1320 | 20,638 | 653 | 15,764 | 22,723 | 53 | 243 | 68 | 450 | 61,913 |

| Residue management | ||||||||||

| Residue removal | 1320 | – | 653 | 15,764 | 22,723 | 35 | 243 | 68 | 450 | 41,257 |

| Residue retention | 1320 | 38,516 | 653 | 15,764 | 22,723 | 71 | 243 | 68 | 450 | 79,808 |

| TCE practice | ||||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 3272 | 17,690 | 518 | 15,764 | 29,723 | – | 155 | 68 | 450 | 67,641 |

| NPTPR-ZT | 2008 | 18,719 | 518 | 15,764 | 19,880 | – | 155 | 68 | 450 | 57,563 |

| ZTTPR-ZT | – | 20,037 | 518 | 15,764 | 19,880 | – | 331 | 68 | 450 | 57,049 |

| ZTDSR-ZT | – | 20,586 | 1056 | 15,764 | 21,409 | 212 | 331 | 68 | 450 | 59,876 |

In wheat, fertilizers, irrigation, diesel, and crop residue (in residue retention treatments) were the primary components of total energy input. Conservation tillage treatments (NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT) reduced the energy requirement in machinery (227 MJ ha−1), diesel (2957 MJ ha−1), and labor (45 MJ ha−1). Subsequently, conservation tillage-based treatments reduced the total energy requirement by 3186 MJ ha−1 in residue removal treatments. However, conservation tillage treatments increased the energy input in the residue retention treatments (Table 4) due to higher crop residue inputs. In maize, conservation tillage practices reduced the total energy requirement by 3051 MJ ha−1, which was primarily because of curtailing the use of diesel energy (2957 MJ ha−1). Energy input in land preparation (3272 MJ ha−1) was completely saved in conservation tillage-based crop establishment practices. The energy input through crop residue constitutes about 39 and 45% in wheat and maize cropping (Table 4).

Table 4.

Operation-wise energy use (MJ ha−1) in wheat and maize crop as influenced by cropping system, residue management, and TCE practices (2-year mean)

| Crop | Treatment | Land preparation | Residue management | Sowing/transplanting | Fertilizer management | Irrigation | Inter-culture | Chemical weed management | Plant protection | Harvest/threshing | Total input energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MJ ha−1) | |||||||||||

| Wheat | Residue management | ||||||||||

| Residue removal | 818 | – | 1727 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 322 | 13 | 450 | 23,050 | |

| Residue retention | 818 | 31,284 | 1727 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 322 | 13 | 450 | 54,334 | |

| TCE practice | |||||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 3272 | 13,772 | 1951 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 34 | 13 | 450 | 39,211 | |

| NPTPR-ZT | – | 15,487 | 1652 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 418 | 13 | 450 | 37,741 | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | – | 15,762 | 1652 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 418 | 13 | 450 | 38,016 | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | – | 17,547 | 1652 | 12,764 | 6955 | – | 418 | 13 | 450 | 39,800 | |

| Maize | Residue management | ||||||||||

| Residue removal | 818 | – | 437 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 466 | 281 | 344 | 20,859 | |

| Residue retention | 818 | 30,176 | 437 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 466 | 281 | 438 | 51,129 | |

| TCE practice | |||||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 3272 | 13,252 | 560 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 178 | 281 | 391 | 36,446 | |

| NPTPR-ZT | – | 14,885 | 396 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 562 | 281 | 391 | 35,028 | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | – | 16,140 | 396 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 562 | 281 | 391 | 36,283 | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | – | 16,074 | 396 | 12,743 | 5769 | – | 562 | 281 | 391 | 36,217 | |

Energy utilization pattern in cropping system

Energy utilization pattern of rice–wheat and rice–maize cropping systems was comparable. Conservation tillage-based crop establishment treatments reduced the energy consumption through fuel, water, and machinery (Fig. 2). Irrespective of the cropping systems, energy input through crop residue was the primary source of input energy in both the cropping systems. The energy input through crop residue was in the order of ZTDSR-ZT > ZTTPR-ZT > NPTPR-ZT > CTTPR-CT (Fig. 2). Table 5 shows that operation-wise, energy requirement was highest for crop residue management (~ 50% of total energy), followed by irrigation and fertilizer management. The conservation tillage-based crop establishment practices reduced the energy consumption in land preparation and irrigation by 4536–6544 MJ ha−1 and 8314–9843 MJ ha−1in rice–wheat and rice–maize rotations. Conservation tillage treatments increased the energy consumption through crop residue by 9–21% and 9–19% compared with CTTPR-CT treatment in rice–wheat and rice–maize system, respectively.

Table 5.

Operation-wise energy use (MJ ha−1) in rice–wheat and rice–maize cropping systems as influenced by residue management and TCE practices (2-year mean)

| Treatment | Land preparation | Sowing/transplanting | Residue management | Fertilizer management | Irrigation | Inter-culture | Chemical weed management | Plant protection | Harvest/threshing | Total input energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MJ ha−1) | |||||||||||

| Rice–wheat | Residue management | ||||||||||

| Residue removal | 2138 | 2379 | – | 28,529 | 29,678 | 35 | 565 | 82 | 900 | 64,307 | |

| Residue retention | 2138 | 2379 | 67,040 | 28,529 | 29,678 | 71 | 565 | 82 | 900 | 131,382 | |

| TCE practice | |||||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 6544 | 2469 | 30,321 | 28,529 | 36,678 | – | 189 | 82 | 900 | 105,711 | |

| NPTPR-ZT | 2008 | 2170 | 32,959 | 28,529 | 26,835 | – | 573 | 82 | 900 | 94,057 | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | – | 2170 | 34,197 | 28,529 | 26,835 | – | 749 | 82 | 900 | 93,462 | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | – | 2708 | 36,602 | 28,529 | 28,364 | 212 | 749 | 82 | 900 | 98,146 | |

| Rice–maize | Residue management | ||||||||||

| Residue removal | 2138 | 1090 | – | 28,508 | 28,492 | 35 | 709 | 349 | 794 | 62,115 | |

| Residue retention | 2138 | 1090 | 71,452 | 28,508 | 28,492 | 71 | 709 | 349 | 889 | 133,697 | |

| TCE practice | |||||||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 6544 | 1078 | 32,084 | 28,508 | 35,492 | – | 333 | 349 | 842 | 105,229 | |

| NPTPR-ZT | 2008 | 914 | 34,851 | 28,508 | 25,649 | – | 717 | 349 | 842 | 93,838 | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | – | 914 | 37,780 | 28,508 | 25,649 | – | 893 | 349 | 842 | 94,934 | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | – | 1452 | 38,190 | 28,508 | 27,178 | 212 | 893 | 349 | 842 | 97,624 | |

Output energy and energy productivity

During the fourth and fifth years of crop rotation, the impact of residue retention and tillage cum crop establishment practices was prominent on grain and straw yields of all the component crops (Supplementary Table 1). Crop residue retention increase in grain and straw yields that resulted in an increase in total output energy by 12,174, 15,596, and 23,972 MJ ha−1 in rice, wheat, and maize crop, respectively. Conservation tillage treatments (NPTPR-ZT, ZTTPR-ZT, and ZTDSR-ZT) increased the grain yield of rice, wheat, and maize by 1–15%, 14–23%, and 5–12% compared with CTTPR-CT, respectively (data not presented). Subsequently, the mean total output energy in conservation tillage treatments was highest in ZTDSR-ZT for all the component crops. The net energy output was higher from the maize and wheat crop, which were notably higher over the rice crop. In parallel, the energy ratio and energy productivity values were highest in maize and least in rice (Table 6).

Table 6.

Crop productivity, input–output energy, and energy indices of rice, wheat, and maize crops as influenced by different cropping system, residue management, and TCE practices (2-year mean)

| Crop | Treatment | Input energy (MJ ha−1) |

Output energy (MJ ha−1) |

Net energy return (MJ ha−1) |

Energy ratio | Energy productivity (kg MJ−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Cropping system | |||||

| Rice–wheat | 59,152 | 164,784a | 105,632a | 3.06a | 0.088a | |

| Rice–maize | 61,913 | 163,272b | 101,359a | 2.98b | 0.085b | |

| Residue management | ||||||

| Residue removal | 41,257 | 157,941b | 116,684a | 3.90a | 0.111a | |

| Residue retention | 79,808 | 170,115a | 90,307b | 2.14b | 0.062b | |

| TCE practice | ||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 67,641 | 150,973d | 83,331c | 2.38c | 0.069b | |

| NPTPR-ZT | 57,563 | 159,411c | 101,848b | 3.06b | 0.086b | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | 57,049 | 168,876b | 111,827a | 3.33a | 0.095a | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | 59,876 | 176,852a | 116,976a | 3.31a | 0.095a | |

| Wheat | Residue management | |||||

| Residue removal | 23,050 | 178,671b | 155,621a | 7.80a | 0.221a | |

| Residue retention | 54,334 | 194,267a | 139,932b | 3.57b | 0.101b | |

| TCE practice | ||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 39,211 | 168,499c | 129,288b | 4.83b | 0.133c | |

| NPTPR-ZT | 37,741 | 186,494b | 148,753a | 5.86ab | 0.166b | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | 38,016 | 193,240ab | 155,224a | 6.04a | 0.172a | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | 39,800 | 197,642a | 157,842a | 6.01a | 0.174a | |

| Maize | Residue management | |||||

| Residue removal | 20,859 | 218,385b | 197,526a | 10.53a | 0.332a | |

| Residue retention | 51,129 | 242,357a | 191,229a | 4.74b | 0.146b | |

| TCE practice | ||||||

| CTTPR-CT | 36,446 | 214,675c | 178,228c | 6.69c | 0.210c | |

| NPTPR-ZT | 35,028 | 225,895b | 190,868b | 7.72b | 0.241b | |

| ZTTPR-ZT | 36,283 | 238,004a | 201,721a | 7.97a | 0.252a | |

| ZTDSR-ZT | 36,217 | 242,910a | 206,693a | 8.15a | 0.253a | |

a–d different letters in continuous column are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05

Rice–maize rotation had a higher net energy return over rice–wheat (Table 7). Crop residue retention reduced the net energy return. The maximum increase in net energy return, energy ratio, and energy productivity was observed in ZTDSR-ZT treatment, which was 26, 32, and 32% higher for rice, wheat, and maize crops, respectively, when compared with CTTPR-CT (conventional practice).

Table 7.

System productivity, output energy, and input–output energy relationship influenced by cropping system, residue management, and TCE practices (2-year mean)

| Treatment | Input energy (MJ ha−1) |

Output energy (MJ ha−1) |

Net energy return (MJ ha−1) |

Energy ratio | Energy productivity (kg MJ−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropping system | |||||

| Rice–wheat | 97,844 | 351,253b | 253,409b | 4.04b | 0.115b |

| Rice–maize | 97,906 | 393,643a | 295,737a | 4.61a | 0.139a |

| Residue management | |||||

| Residue removal | 63,211 | 356,469b | 293,258a | 5.72a | 0.168a |

| Residue retention | 132,539 | 388,427a | 255,888b | 2.93b | 0.086b |

| TCE practice | |||||

| CTTPR-CT | 105,470 | 342,559d | 237,089c | 3.53c | 0.104c |

| NPTPR-ZT | 93,947 | 365,606c | 271,658b | 4.41b | 0.128b |

| ZTTPR-ZT | 94,198 | 384,498b | 290,300a | 4.70a | 0.139a |

| ZTDSR-ZT | 97,885 | 397,129a | 299,243a | 4.67a | 0.137a |

a–d different letters in continuous column are significantly different at p ≤ 0.05

Energy-economics relations and multivariate analysis

Table 8 shows that energy indices and economic parameters had significant correlations. Total cost of cultivation (TCC) had significant negative association with output energy, net energy, energy ratio, and energy productivity parameters (p < 0.05). In contrast, input energy had non-significant correlation with total cost of cultivation, gross return, net return, and benefit–cost ratio. Net energy return and net economic return had a strong positive correlation (p < 0.001).

Table 8.

Correlation coefficient (r) matrix of different energy and economic parameters (n = 48)

| Parameter | IE | OE | NE | ER | EP | GR | TCC | NR | BCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE | |||||||||

| OE | 0.40** | ||||||||

| NE | − 0.53*** | 0.56*** | |||||||

| ER | − 0.95*** | − 0.11 | 0.75*** | ||||||

| EP | − 0.92*** | − 0.06 | 0.77*** | 0.99*** | |||||

| GR | − 0.10 | 0.56*** | 0.61*** | 0.26* | 0.23 | ||||

| TCC | 0.18 | − 0.48*** | − 0.60*** | − 0.35* | − 0.34* | − 0.74*** | |||

| NR | − 0.13 | 0.57*** | 0.64*** | 0.31* | 0.29* | 0.97*** | − 0.89*** | ||

| BCR | − 0.14 | 0.55*** | 0.63*** | 0.32* | 0.30* | 0.95*** | − 0.91*** | 1.00*** |

IE input energy, OE output energy, NE net energy, ER energy ratio, EP energy productivity, GR gross return, TCC total cost of cultivation, NR net return, BCR B/C ratio

*Significant at p < 0.05

**Significant at p < 0.01

***Significant at p < 0.001

Scatter plot of treatments on PCA coordinates showed that residue retention and residue removal treatments are distinctly located on PCA coordinates (Fig. 3). Conservation tillage treatments ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT in rice–maize cropping system are positioned in right-hand-side coordinates with higher weightage of component 1 (42.7%). A close association between energy parameters like output energy, net energy, energy ratio, and energy productivity is also apparent from PCA graph (Fig. 3). Heatmap and cluster analysis also established the same, where treatments ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT were demarcated as the best treatments (clusters with close association) based on the energy parameters. The predicted regression models revealed that the association between total energy input and system productivity (systems rice equivalent grain yield) were either non significant (residue retention) or negative (residue removal) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot of treatments on PCA coordinates and their association with energy parameters (a). Loading value (correlation) of different variables for PC1 and PC2 (b). Heat map and cluster presentation of treatments based on the energy parameters (c). LP energy input for land preparation, RES crop residue energy input, S/T energy input for sowing/transplanting, FERT energy input for fertilizers application, IRR energy input for irrigation management, INT energy input for intercultural operation, HERB energy input for herbicide and its application, PP energy input for plant protection, HAR energy input for harvesting, IE input energy, OE output energy, RGEY system rice equivalent yield, ER energy ratio, EP energy productivity, NE net energy, RW rice–wheat, RM rice–maize, T1 CTTPR-CT, T2 NPTPR-ZT, T3 ZTTPR-ZT, T4 ZTDSR-ZT, R− residue removal, R+ residue retention (for heat map, R stands for residue retention)

Discussion

Conservation of non-renewable energy sources is a primary concern worldwide. Fossil fuels (e.g., diesel) are the directly non-renewable source of energy, where fertilizers are considered as indirect non-renewable energy source (Saad et al. 2016). After the USA, China, and Japan, India is the fourth largest consumer of oil and petroleum products (Kaplan 2009). The groundwater for irrigation (freshwater) is a directly renewable natural resource. These natural resources are limited and depleting fast. Hence, the efficient use of these resources through strategic changes in the agro-technique(s) is warranted to remain sustainable in the long run (Kumar et al. 2018; Venkatesh et al. 2019). The groundwater for irrigation is declining rapidly. Tube well is the primary source of irrigation in the IGP region and a remarkable fall in the groundwater table in rice–wheat growing regions has been observed in the last two to three decades (Gupta et al. 2002; Yadav et al. 2018), which warrants serious attention. As a result, the energy requirement for pumping of groundwater has increased by many folds, particularly in northwestern India—a rice–wheat dominating agro-region. Given the context, the relevance of CA practices in rice-based cropping systems for conservation of energy and natural resources would be a win–win situation.

Tillage-based crop establishment practices and energy relation

Complete elimination of tillage in rice–wheat and rice–maize cropping systems (i.e., ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT) or only dry-tillage during rice season (NPTPR-ZT) could curtail the requirement of non-renewable energy source, i.e., diesel. Thus, the reduced use of fossil fuel in conservation tillage treatments is likely to reduce the load of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and thus adds to ecosystem services (Busari et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2016a). On the other hand, complete elimination of tillage or reduced tillage limits the oxidation of soil organic matter and thus has an advantage of lower emission of carbon dioxide (Dossou-Yovo et al. 2016; Ladha et al. 2016). Our results on soil parameters (data not presented) also support the fact that conservation tillage enhances C-sequestration and reduces soil carbon loss, being higher in ZTDSR-ZT and ZTTPR-ZT treatments (Nandan et al. 2019). Our results further demonstrate that the increased potential of energy conservation through conservation tillage practices in rice crop compared with that of wheat or maize crop is primarily because of higher energy use in tillage, transplanting, and irrigation in rice crop.

The advantage of conservation tillage on energy conservation is also attributed to the reduced requirement of irrigation as compared with conventional CTTPR-CT (Table 1). Constructive changes in soil attributes and a different rice growing ecology under conservation tillage practices substantially reduced the irrigation requirement in rice crop (Nandan et al. 2019; Gathala et al. 2019). For instance, in conventional puddled condition, standing water is maintained throughout the rice growing season, where in conservation tillage cum crop establishment practices flooded condition was avoided, thereby reducing energy investment in irrigation to rice. Conservation tillage treatments improved the soil environment (particularly soil aggregation and SOC) that might have helped to curtail (28–33%) the water requirements as compared with CTTPR-CT (Nandan et al. 2018a; Nandan et al. 2019). The higher use of herbicides in conservation tillage treatments had marginal influence on total energy input value as these herbicides were applied in small quantities.

The yield advantage with conservation tillage practices (particularly ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT) over CTTPR-CT treatment directly reflected in the higher energy output, which is primarily because of improvement in soil quality parameters and favorable crop growing environment under conservation tillage treatments. The mid-term or long-term impact of conservation tillage practices on soil quality and crop productivity has been observed in most of the earlier studies (Jat et al. 2013; Ladha et al. 2016). As the positive impact of conservation tillage on soil properties and crop productivity is likely to increase over time, an increase in energy output is therefore expected with long-run adoption of conservation tillage in rice-based rotations.

Fertilizer energy input accounted for a major share in the total input energy. Changes in soil moisture and tillage regimes in conservation tillage practices may influence the crop response to fertilizer application—a key yield determining factor. Particular to tropical rice soils, conventional submerged soil conditions have an advantage for nutrient mobilization (particularly N, P, and Zn); on the contrary, it also allows losses of some nutrients from soil profile, and thus crops with conservation tillage practices may have a differential fertilizer requirement that must be looked into.

Crop residue retention and energy relations

Crop residue retention is an integral component of CA and it strongly influences the energy inflow. Indeed, in some of the previous studies, crop residue has not been taken as a component for estimation of energy budgeting as the retained or incorporated crop residues is an integral part of the soil system (Saad et al. 2016; Ronga et al. 2019). Indeed, in a country like India and in other south Asian countries, crop residues are widely used for cattle feeding, thatching of houses, and domestic fuel (Devi et al. 2017), whereas in the large parts of the IGP, crop residues of rice and wheat crop are burnt as an easy disposal of the left-out residues after combine harvesting (Lohan et al. 2018; Ravindra et al. 2019). However, this practice has a notable adverse impact on the environment (Kumar et al. 2015; Gupta et al. 2016b; Singh et al. 2019). Burning of residues in the IGP has drawn the attention of researchers and planners as this practice has several adverse impacts on productivity of soil and environment. The benefits of residue retention in tropical agro-regions are significant and improve crop productivity and soil health (Mandal et al. 2007; Venkatesh et al. 2013). Our study suggested that the yield benefits from residue retention could not compensate the energy input through residue retention. Nevertheless, cereal–cereal rotations like rice–wheat and rice–maize produce a large amount of biomass, and recycling of one third of total straw biomass—as a renewable source of bio-energy—is therefore a sustainable approach and also a socially adaptable approach in a country like India. The total available crop residue in the IGP region is ~ 42 million tons that have a fertilizer replacement value of about 3.6 billion Indian national rupees year−1. Hence, the bio-energy inflow in CA practices must be looked in a different perspective.

Cropping system and energy relations

Cropping system and associated management practices directly influence the energy use and energy productivity (Tuti et al. 2012). Our results demonstrate that both rice–maize and rice–wheat are comparable for their energy requirement; however, the higher productivity potential of rice–maize rotation resulted in higher energy productivity and is thus recommended. Conservation tillage treatments improve the productivity of all the crops being higher in wheat (14–23%) followed by rice (9–15%). Nevertheless, the impact of conservation agriculture on energy productivity and energy ratio was more prominent on rice–wheat rotation over rice–maize rotation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, under conservation agriculture, rice–wheat would be the strategic choice over rice–maize system, particularly in the IGP region.

Energy-economics relationship

Our results support the “conservative hypothesis” of energy-economic relations. In the present study, input energy did not influence the gross return and net return. In fact, both crop productivity and economic return were higher in conservation tillage or CA practices, where energy requirement was substantially reduced. Hence, the CA practices could be a potential alternative for elevating the energy productivity in rice-based cropping systems of the IGP, where the economic status of the farmers is also not much favorable.

Conclusions

The study therefore advocates CA practices in rice–wheat/maize cropping systems to curtail the energy inputs, conserving natural resources, and sustaining the crop productivity. Our results recommended that CA could be a potential alternative to tillage and input-intensive conventional rice-based production system (CTTPR-CT), which are practiced in large scale in South Asia. Apart from the benefits of soil health restoration and production sustainability, adoption of CA in rice-based production systems adequately minimized the energy investment through non-renewable fossil fuels (land preparation, irrigation), and therefore adds to the ecosystem services and cleaner production. In the context of degrading natural resources (particularly groundwater and soil quality) in the IGP region, conservation agriculture in rice-based cropping systems could be the strategic option. Conservation tillage treatments particularly ZTTPR-ZT and ZTDSR-ZT could upscale the energy productivity and conserve the non-renewable energy resources. In tropical regions, retention of a part of crop residue in high biomass production systems is a sustainable approach as it has the notable positive impact on soil health associated with yield benefits. The study also proposed that higher energy inputs are not essentially the primary driver of profitable production system. Thus, minimal use of energy sources through CA practices is likely to have a large impact on production economies and environments.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 70 kb)

Acknowledgments

We sincerely acknowledge the supports provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through a project entitled “Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA)”. The authors are also thankful to ICAR–RCER for providing experimental fields and other technical and administrative support in conducting this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rajiv Nandan and Kali Krishna Hazra contributed equally to this work.

References

- Alam MK, Bell RW, Biswas WK. Increases in soil sequestered carbon under conservation agriculture cropping decrease the estimated greenhouse gas emissions of wetland rice using life cycle assessment. J Clean Prod. 2019;224:72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A, Apergis N, Yildirim S. Causality between energy consumption and GDP in the US: evidence from wavelet analysis. Front Energy. 2014;8(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Azarpour E. Determination of energy balance and energy indices in wheat production under watered farming in north of Iran. J Agric Biol Sci. 2012;7(4):250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Babicki S, Arndt D, Marcu A, Liang Y, Grant JR, Maciejewski A, Wishart DS. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):147–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busari MA, Kukal SS, Kaur A, Bhatt R, Dulazi AA. Conservation tillage impacts on soil, crop and the environment. Inter Soil Water Conserv Res. 2015;3(2):119–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary VP, Gangwar B, Pandey DK, Gangwar KS. Energy auditing of diversified rice–wheat cropping systems in Indo-Gangetic Plains. Energy. 2009;34(9):1091–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan BS, Mahajan G, Sardana V, Timsina J, Jat ML. Productivity and sustainability of the rice–wheat cropping system in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of the Indian subcontinent: problems, opportunities, and strategies. Adv Agron. 2012;117:315–369. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary M, Rana KS, Bana RS, Ghasal PC, Choudhary GL, Jakhar P, Verma RK. Energy budgeting and carbon footprint of pearl millet–mustard cropping system under conventional and conservation agriculture in rainfed semi-arid agro-ecosystem. Energy. 2017;141:1052–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Devasenapathy P, Ramesh T, Gangwar B. Efficiency indices for agriculture management research. New Delhi: New India Publishing Agency; 2008. p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Devasenapathy P, Senthilkumar G, Shanmugam PM. Energy management in crop production. Indian J Agron. 2009;54(1):80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Devi S, Gupta C, Jat SL, Parmar MS. Crop residue recycling for economic and environmental sustainability: the case of India. Open Agric. 2017;2(1):486–494. [Google Scholar]

- Devkota KP, Yadav S, Khanda CM, Beebout SJ, Mohapatra BK, Singleton GR, Puskur R. Assessing alternative crop establishment methods with a sustainability lens in rice production systems of eastern India. J Clean Prod. 2019;244:118835. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossou-Yovo ER, Brüggemann N, Jesse N, Huat J, Ago EE, Agbossou EK. Reducing soil CO2 emission and improving upland rice yield with no-tillage, straw mulch and nitrogen fertilization in northern Benin. Soil Tillage Res. 2016;156:44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gathala MK, Laing AM, Tiwari TP, Timsina J, Islam S, Bhattacharya PM, Dhar T, Ghosh A, Sinha AK, Chowdhury AK, Hossain S. Energy-efficient, sustainable crop production practices benefit smallholder farmers and the environment across three countries in the eastern Gangetic Plains. South Asia J Cleaner Prod. 2019;246:118982. [Google Scholar]

- Gathala MK, Timsina J, Islam MS, Rahman MM, Hossain MI, Harun-Ar-Rashid M, Ghosh AK, Krupnik TJ, Tiwari TP, McDonald A. Conservation agriculture based tillage and crop establishment options can maintain farmers’ yields and increase profits in South Asia’s rice–maize systems: evidence from Bangladesh. Field Crop Res. 2015;172:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta DK, Bhatia A, Kumar A, Das TK, Jain N, Tomer R, Malyan SK, Fagodiya RK, Dubey R, Pathak H. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emission from rice–wheat system of the Indo-Gangetic Plains: through tillage, irrigation and fertilizer management. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2016;230:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Naresh RK, Hobbs PR, Ladha JK (2002) Adopting conservation agriculture in the rice–wheat system of the Indo-Gangetic Plains: new opportunities for saving water. In: Water wise rice production. Proceedings of the international workshop on water wise rice production, April 8–11, 2002, Los Baños, Philippines pp 207–22

- Gupta S, Agarwal R, Mittal SK. Respiratory health concerns in children at some strategic locations from high PM levels during crop residue burning episodes. Atmos Environ. 2016;137:127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra KK, Ghosh PK, Venkatesh MS, Nath CP, Kumar N, Singh M, Singh J, Nadarajan N. Improving soil organic carbon pools through inclusion of summer mungbean in cereal–cereal cropping systems in Indo-Gangetic Plain. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2018;64(12):1690–1704. [Google Scholar]

- Hazra KK, Nath CP, Ghosh PK, Swain DK (2019) Inclusion of legumes in rice–wheat cropping system for enhancing carbon sequestration. In: Ghosh PK et al. (eds.) Carbon management in tropical and sub-tropical terrestrial systems. Pp. 23-36. 10.1007/978-981-13-9628-1_2

- Jat ML, Gathala MK, Saharawat YS, Tetarwal JP, Gupta R. Double no-till and permanent raised beds in maize–wheat rotation of north-western Indo-Gangetic Plains of India: effects on crop yields, water productivity, profitability and soil physical properties. Field Crop Res. 2013;149:291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RD (2009) Center stage for the twenty-first century: power plays in the Indian Ocean. Foreign Affairs 88(2):16–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20699491

- Kasman A, Duman YS. CO2 emissions, economic growth, energy consumption, trade and urbanization in new EU member and candidate countries: a panel data analysis. Econ Model. 2015;44:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Hazra KK, Nath CP, Praharaj CS, Singh U. Legumes for soil health and sustainable management. Singapore: Springer; 2018. Grain legumes for resource conservation and agricultural sustainability in South Asia; pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Nath CP, Hazra KK, Das K, Venkatesh MS, Singh MK, Singh SS, Praharaj CS, Singh NP. Impact of zero-till residue management and crop diversification with legumes on soil aggregation and carbon sequestration. Soil Tillage Res. 2019;189:158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Kumar S, Joshi L (2015) Socioeconomic and environmental implications of agricultural residue burning: a case study of Punjab, India. Springer Open ISBN 978-81-322-2146-3

- Kumar R, Mishra JS, Rao KK, Bhatt BP, Hazra KK, Hans H, Mondal S. Sustainable intensification of rice fallows of eastern India with suitable winter crop and appropriate crop establishment technique. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:29409–29423. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Mishra JS, Rao KK, Mondal S, Hazra KK, Choudhary JS, Hans H, Bhatt BP. Crop rotation and tillage management options for sustainable intensification of rice-fallow agro-ecosystem in eastern India. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67973-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladha JK, Rao AN, Raman AK, Padre AT, Dobermann A, Gathala M, Kumar V, Saharawat Y, Sharma S, Piepho HP, Alam MM. Agronomic improvements can make future cereal systems in South Asia far more productive and result in a lower environmental footprint. Glob Chang Biol. 2016;22(3):1054–1074. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal B, Gautam P, Nayak AK, Panda BB, Bihari P, Tripathi R, Shahid M, Guru PK, Chatterjee D, Kumar U, Meena BP. Energy and carbon budgeting of tillage for environmentally clean and resilient soil health of rice–maize cropping system. J Clean Prod. 2019;226:815–830. [Google Scholar]

- Lohan SK, Jat HS, Yadav AK, Sidhu HS, Jat ML, Choudhary M, Peter JK, Sharma PC. Burning issues of paddy residue management in north-west states of India. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2018;81:693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal B, Majumder B, Bandyopadhyay PK, Hazra GC, Gangopadhyay A, Samantaray RN, Mishra AK, Chaudhury J, Saha MN, Kundu S. The potential of cropping systems and soil amendments for carbon sequestration in soils under long-term experiments in subtropical India. Glob Chang Biol. 2007;13(2):357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Nandan R, Singh SS, Kumar V, Singh V, Hazra KK, Nath CP, Malik RK, Poonia SP, Solanki CH. Crop establishment with conservation tillage and crop residue retention in rice-based cropping systems of eastern India: yield advantage and economic benefit. Paddy Water Environ. 2018;16(3):477–492. [Google Scholar]

- Nandan R, Singh V, Singh SS, Kumar V, Hazra KK, Nath CP, Poonia S, Malik RK, Singh SK, Singh PK. Comparative assessment of different tillage-cum-crop establishment practices and crop-residue management on crop and water productivity and profitability of rice (Oryza sativa)–wheat (Triticum aestivum) cropping system. Ind J Agron. 2018;63(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nandan R, Singh V, Singh SS, Kumar V, Hazra KK, Nath CP, Poonia SP, Malik RK, Bhattacharyya R, McDonald A. Impact of conservation tillage in rice–based cropping systems on soil aggregation, carbon pools and nutrients. Geoderma. 2019;340:104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan S. Predictability within the energy consumption–economic growth nexus: some evidence from income and regional groups. Econ Model. 2016;54:515–521. [Google Scholar]

- Nath CP, Hazra KK, Kumar N, Praharaj CS, Singh SS, Singh U, Singh NP. Including grain legume in rice–wheat cropping system improves soil organic carbon pools over time. Ecol Eng. 2019;129:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo NS. Energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Energy Econ. 2013;36:637–647. [Google Scholar]

- Parihar CM, Parihar MD, Sapkota TB, Nanwal RK, Singh AK, Jat SL, Nayak HS, Mahala DM, Singh LK, Kakraliya SK, Stirling CM. Long-term impact of conservation agriculture and diversified maize rotations on carbon pools and stocks, mineral nitrogen fractions and nitrous oxide fluxes in inceptisol of India. Sci Total Environ. 2018;640:1382–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel D, Rodrigues G, Wang T, Abrams R, Goldberg K, Staecker H, Ma E, Brueckner L, Trovato L, Chow C, Govindarajulu U. Renewable energy: economic and environmental issues. BioScience. 1994;44(8):536–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindra K, Singh T, Mor S. Emissions of air pollutants from primary crop residue burning in India and their mitigation strategies for cleaner emissions. J Clean Prod. 2019;208:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ronga D, Gallingani T, Zaccardelli M, Perrone D, Francia E, Milc J, Pecchioni N. Carbon footprint and energetic analysis of tomato production in the organic vs the conventional cropping systems in southern Italy. J Clean Prod. 2019;220:836–845. [Google Scholar]

- Saad AA, Das TK, Rana DS, Sharma AR, Bhattacharyya R, Lal K. Energy auditing of a maize–wheat–greengram cropping system under conventional and conservation agriculture in irrigated north-western Indo-Gangetic Plains. Energy. 2016;116:293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Van Hoang TH, Mahalik MK, Roubaud D. Energy consumption, financial development and economic growth in India: new evidence from a nonlinear and asymmetric analysis. Energy Econ. 2017;63:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran OP, Tonk DS, Kaushik LS, Hasija RC, Pannu RS (1998) Statistical software package for agricultural research workers. Recent advances in information theory, statistics and computer applications by Hooda, DS and Hasija, RC, Department of Mathematics Statistics, CCS HAU, Hisar. pp.139–143

- Singh R, Yadav DB, Ravisankar N, Yadav A, Singh H (2019) Crop residue management in rice–wheat cropping system for resource conservation and environmental protection in North-Western India. Environ Dev Sustain 22(5):3871–3896

- Tuti MD, Prakash V, Pandey BM, Bhattacharyya R, Mahanta D, Bisht JK, Kumar M, Mina BL, Kumar N, Bhatt JC, Srivastva AK. Energy budgeting of colocasia-based cropping systems in the Indian sub-Himalayas. Energy. 2012;45(1):986–993. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh MS, Hazra KK, Ghosh PK, Mishra JP. Integrated phosphorus management in maize–chickpea rotation in moderately-alkaline Inceptisol in Kanpur, India: an agronomic and economic evaluation. Field Crop Res. 2019;233:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh MS, Hazra KK, Ghosh PK, Praharaj CS, Kumar N. Long-term effect of pulses and nutrient management on soil carbon sequestration in Indo-Gangetic Plains of India. Can J Soil Sci. 2013;93(1):127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav GS, Das A, Lal R, Babu S, Meena RS, Saha P, Singh R, Datta M. Energy budget and carbon footprint in a no-till and mulch based rice–mustard cropping system. J Clean Prod. 2018;191:144–157. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 70 kb)