Abstract

This cohort study evaluated the joint association of dietary and lifestyle factors with risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms among women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects nearly 30% of the US population.1 Clinicians recommend dietary and lifestyle modifications to prevent GERD symptoms, but no prospective data are available to inform these recommendations. We evaluated the joint association of dietary and lifestyle factors with the risk of GERD symptoms.

Methods

The Nurses’ Health Study II is an ongoing nationwide prospective cohort study established in 1989 with 116 671 female participants returning biennial health questionnaires, including information on smoking, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters), physical activity, medication use, and history of diabetes and a validated, semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire every 4 years. Follow-up exceeds 90%.2 We queried about acid reflux or heartburn in 2005, 2009, 2013, and 2017.3 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Return of the questionnaire was considered to imply consent. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

For this analysis, we excluded women at baseline if they reported GERD symptoms weekly or more, had cancer, regularly used proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) and/or histamine receptor antagonists (H2RA), had missing dietary data, or were lost to follow-up. We calculated an antireflux lifestyle score (range, 0-5) consisting of 5 dichotomized variables: normal weight (body mass index ≥18.5 and <25.0); never smoking; moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for at least 30 minutes daily; no more than 2 cups of coffee, tea, or soda daily; and a prudent diet4 (top 40% of dietary pattern score). Women were considered to have GERD symptoms if they reported acid reflux or heartburn at least weekly, as in previous studies.3

Person-years of follow-up accrued from the date of return of the 2007 questionnaire (starting June 1, 2007) to the first report of GERD, death, or end of follow-up (June 1, 2017), whichever came first. We computed multivariable hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs using Cox proportional hazards models stratified by age and time and adjusted with time-varying covariates for total caloric intake; alcohol intake; use of menopausal hormones, PPIs, or H2RA; use of medications that may decrease lower esophageal sphincter pressure (ie, calcium channel blockers, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants); and history of diabetes.

We calculated the population-attributable risk for GERD symptoms attributable to all 5 antireflux lifestyle factors by estimating the relative risk from multivariable logistic regression models while controlling for other covariates. We used a significance threshold of P < .05 using 2-sided tests. SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc) was used for statistical analyses. Data were analyzed from September 1, 2019, to June 22, 2020.

Results

Our cohort included 42 955 women aged 42 to 62 years (mean [SD] age, 52.0 [4.7] years). During 392 215 person-years of follow-up, we identified 9291 incident cases of GERD symptoms.

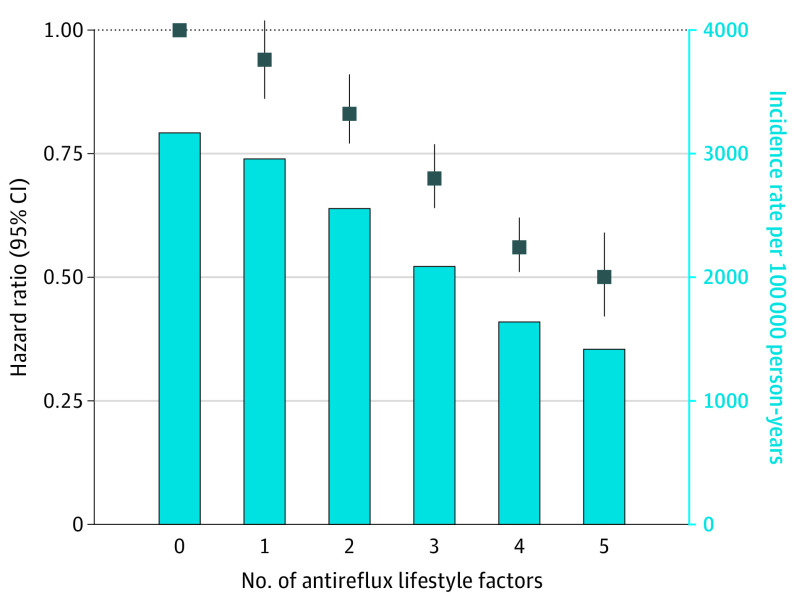

Compared with women without adherence to antireflux lifestyle factors, the multivariable HR for GERD symptoms was 0.50 (95% CI, 0.42-0.59) for those with 5 antireflux lifestyle factors (Figure). The proportion of cases of GERD symptoms that may be prevented by all 5 factors included in the antireflux lifestyle score was 37% (95% CI, 28%-46%).

Figure. Risk of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) Symptoms According to an Antireflux Lifestyle Score.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs. The antireflux lifestyle score (range, 0-5) consisted of 5 factors: normal body weight (body mass index [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters], ≥18.5 and <25.0); never smoking; moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for at least 30 minutes per day; no more than 2 cups of coffee, tea, or soda per day; and a prudent diet (prudent dietary scores in the highest 40% of the cohort). Models were adjusted for age, calendar period, total caloric intake, use of medications that may decrease the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (ie, calcium channel blockers, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants), use of menopausal hormones, proton-pump inhibitors, or histamine receptor antagonists , history of diabetes, and intake of alcohol (in g/d). Those with an antireflux lifestyle score of 0 included 665 incident cases (5% of person-years); score of 1, 2285 (20% of person-years); score of 2, 3005 (30% of person-years); score of 3, 2215 (27% of person-years); score of 4, 941 (15% of person-years); and score of 5, 180 (3% of person-years) (n = 9291).

Each of the 5 lifestyle factors were independently associated with GERD symptoms. The individual mutually adjusted multivariable HRs for nonadherence to each factor ranged from 0.94 (95% CI, 0.90-0.99; population-attributable risk, 3%) for smoking to 0.69 (95% CI, 0.66-0.72; population-attributable risk, 19%) for body mass index (Table).

Table. Association of Individual Dietary and Lifestyle Factors With Risk for Incident Gastrointestinal Reflux Disease Symptomsa.

| Dietary or lifestyle factor | Low-risk definition | Person-years at low risk (%) | HR (95% CI) | PAR (95% CI), %b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | Multivariableb | ||||

| Smoking | Never smoker | 268 466 (68) | 0.90 (0.86-0.94) | 0.94 (0.90-0.99) | 3 (0-6) |

| Coffee, soda, and tea intake | ≤2 Cups/d | 126 456 (32) | 0.90 (0.86-0.94) | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | 4 (1-7) |

| Food intake | Top 40% of prudent dietary pattern scores | 160 039 (41) | 0.81 (0.78-0.85) | 0.87 (0.84-0.91) | 7 (6-8) |

| Physical activity | ≥30 min Moderate-to-vigorous activity (eg, brisk walking) | 190 813 (49) | 0.78 (0.75-0.81) | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | 8 (6-11) |

| BMI | 18.5-24.9 | 184 170 (47) | 0.62 (0.60-0.65) | 0.69 (0.66-0.72) | 19 (15-23) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters); HR, hazard ratio; PAR, population-attributable risk.

Includes 9291 cases.

Adjusted for age, calendar period, total caloric intake, use of medications that may decrease the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (ie, calcium channel blockers, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants), use of menopausal hormones, proton-pump inhibitors, or histamine receptor antagonists, history of diabetes, and intake of alcohol (in g/d) and mutually adjusted for the other lifestyle factors. Estimates for gastrointestinal reflux disease symptoms are based on nonadherence to each factor.

We considered the possibility that initiation of PPI and/or H2RA treatment during follow-up may have influenced our results. We conducted analyses in which we considered use of these agents to indicate the presence of GERD symptoms and observed consistent results. Those with 5 factors had a multivariable-adjusted HR of 0.47 (95% CI, 0.41-0.54) for GERD symptoms or initiation of PPI and/or H2RA treatment compared with those with no antireflux lifestyle factors. In an analysis of 3625 women who reported regular use of PPIs and/or H2RAs and were free of GERD symptoms at baseline, those with 5 factors had a multivariable-adjusted HR of 0.32 (95% CI, 0.18-0.57) for GERD symptoms compared with PPI and/or H2RA users with no antireflux lifestyle factors.

Discussion

Adherence to an antireflux lifestyle, even among regular users of PPIs and/or H2RAs, was associated with a decreased risk of GERD symptoms and may prevent nearly 40% of GERD symptoms that occur at least weekly. Possible explanations include decreases in lower esophageal sphincter tone, increases in gastroesophageal pressure gradients, and mechanical factors, including hiatal hernia.5

Study limitations include self-reported GERD symptoms. However, in clinical practice, GERD is primarily self-reported without confirmatory testing. Second, the population-attributable risk estimate is population specific and assumes a causal relationship. Third, our study was limited primarily to White women. However, GERD is more common in White women aged 30 to 60 years.6 These data support the importance of lifestyle modification in management of GERD symptoms.

References

- 1.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292(8):927-934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta RS, Song M, Staller K, Chan AT. Association between beverage intake and incidence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(10):2226-2233.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fung T, Hu FB, Fuchs C, et al. Major dietary patterns and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):309-314. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.3.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emerenziani S, Rescio MP, Guarino MPL, Cicala M. Gastro-esophageal reflux disease and obesity, where is the link? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(39):6536-6539. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delshad SD, Almario CV, Chey WD, Spiegel BMR. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and proton pump inhibitor-refractory symptoms. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1250-1261.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]