Abstract

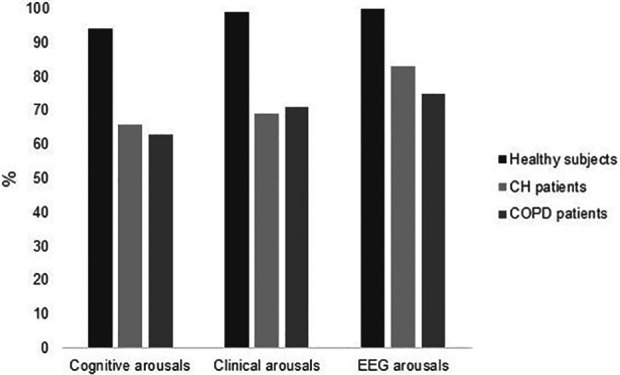

The objective of this study was to test the capacity of vibrotactile stimulation transmitted to the wrist bones by a vibrating wristband to awaken healthy individuals and patients requiring home mechanical ventilation during sleep. Healthy subjects (n = 20) and patients with central hypoventilation (CH) (Congenital Central Hypoventilation syndrome n = 7; non-genetic form of CH n = 1) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n = 9), underwent a full-night polysomnography while wearing the wristband. Vibrotactile alarms were triggered five times during the night at random intervals. Electroencephalographic (EEG), clinical (trunk lift) and cognitive (record the time on a sheet of paper) arousals were recorded. Cognitive arousals were observed for 94% of the alarms in the healthy group and for 66% and 63% of subjects in the CH and COPD groups, respectively (p < 0.01). The percentage of participants experiencing cognitive arousals for all alarms, was 72% for healthy subjects, 37.5% for CH patients and 33% for COPD patients (ns) (94%, 50% and 44% for clinical arousals (p < 0.01) and 100%, 63% and 44% for EEG arousals (p < 0.01)). Device acceptance was good in the majority of cases, with the exception of one CH patient and eight healthy participants. In summary this study shows that a vibrotactile stimulus is effective to induce awakenings in healthy subjects, but is less effective in patients, supporting the notion that a vibrotactile stimulus could be an effective backup to a home mechanical ventilator audio alarm for healthy family caregivers.

Keywords: Chronic respiratory failure, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, monitoring, sleep, family, caregivers, vibrotactile stimulation

Introduction

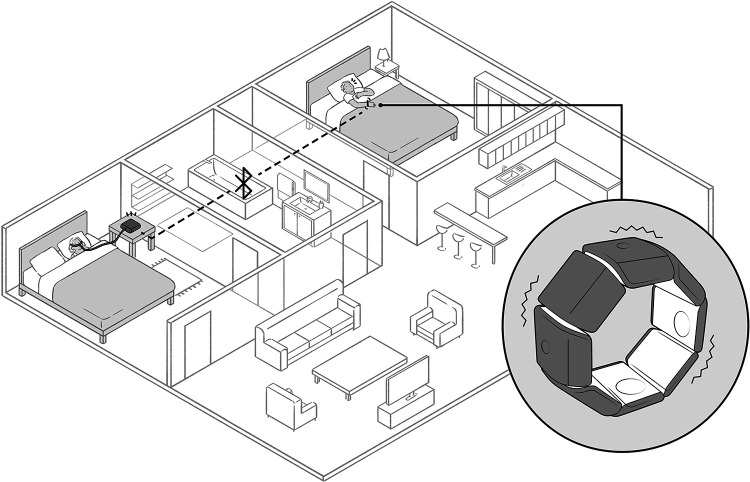

Patients with severe chronic respiratory failure who require home mechanical ventilation often depend on the help of a caregiver. This is systematically the case when the underlying disease affects not only breathing but also motor abilities, especially when the patient is unable to directly manage the ventilator (e.g. myopathies, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, quadriplegia, etc.). In such conditions, the life-supporting nature of mechanical ventilation imposes a considerable burden of care and responsibility on caregivers, which can have a considerable impact on the quality of life of family caregivers.1 Among other things, the caregivers of ventilator-dependent patients must remain permanently within earshot of the ventilator alarm, in order to rapidly intervene in the event of a life-threatening dysfunction. To help resolve this problem, we have developed and patented a listening device that can learn to identify home mechanical ventilator alarms2 in order to activate external relay systems, such as a secondary audio alarm, a video link, or contact with a telemedicine platform. One of the possibilities provided by this device is to transform the ventilator alarm into a vibrotactile stimulation (see Figure 1). ‘Vital alarms’ such as complete obstruction or disconnection are the target of the monitoring. One important point is to avoid triggering the vibrotactile device too early to limit the number of false alerts. Clinical practice suggests that an alarm that lasts more than 10–15 seconds is probably significant. The reliability of the system to identify the alarm of the ventilator in noisy environment (e.g. with a radio or TV on in the same room, or with an open window and traffic noises in the street) has been the object of satisfactory preliminary testing.

Figure 1.

Patented listening device to identify home mechanical ventilator alarms and activate external relay systems.

Vibrotactile stimulation can induce pleasant, non-stressful awakenings3. In the present study, we tested the capacity of vibrotactile stimulation transmitted to the wrist bones by a vibrating wristband to awaken healthy individuals. We also tested the capacity of this vibrotactile stimulation to directly awaken patients on home mechanical ventilation. We studied patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) receiving home mechanical ventilation (non-invasive ventilation, NIV) for various reasons. We also studied adult patients with central congenital hypoventilation syndrome due to PHOX2B mutations, following reports by some parents that their children have difficulty hearing the ventilator alarms while asleep.

Methods

Participants

Twenty healthy adults (median age: 27 years, interquartile range [23; 30]; 11 women) (healthy subjects group), eight adult patients with central hypoventilation (CH) (19 years [19–24], 4 women) (CH group), and nine patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) requiring nocturnal non-invasive ventilation (NIV) (66 years [65; 74]; 5 women) (COPD group) were included in this study. The protocol was approved by an ethics committee (Comité de Protection des personnes Ile de France 6 on 19 October 2016) and was registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov registry under number NCT03053011 before inclusion of the first participant. All participants were informed about the study and provided their written consent.

Healthy subjects were recruited by word-of-mouth. All of these subjects had a normal respiratory and neurological examination on inclusion. Patients with CH were recruited consecutively during their usual follow-up visit in the adult section of the French national reference centre. Seven patients had a neonatal form of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) with confirmed PHOX2B mutations, while one 19-year-old male patient was diagnosed with a non-genetic form of CH (Ondine-like syndrome). All patients were stable on inclusion in the study. COPD patients were recruited from the Pitié-Salpêtrière (Paris) respiratory rehabilitation centre. All were in patients with severe airway obstruction (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1): 0.74 l [0.70–0.84]; 32% predicted [27; 34]). They had been treated by nocturnal NIV for a median of 6 [3–26] months. At the time of the study, they had had a stable respiratory condition for 24 [18–52] days. For all participants, intake of alcohol or any substance that may interfere with sleep patterns was prohibited for 24 hours before the study. The participants’ baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

| Healthy subjects | CH patients | COPD patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 20 | 8 | 9 | |

| Age, y | 27 [23–30] | 19 [19–24] | 66 [65–74] | <0.0001 a, b, c |

| Gender, n F/M | 11/9 | 4/4 | 5/4 | 1.000 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25 [22–26] | 22 [20–24] | 24 [18–29] | 0.493 |

| ESS, 0–24 | 5 [3–7] | 4 [1–6] | 6 [2–6] | 0.440 |

| PSQI, 0–57 | 5 [4–7] | 4 [2–5] | 10 [6–12] | 0.001 b, c |

| Quality of sleep | ||||

| the night before polysomnography (very good/good/middling/bad/very bad) |

1/4/12/1/2 | 0/6/2/0/0 | 0/3/2/2/2 | 0.056 |

| compared to usual (significantly better/better/similar/worse/significantly worse) |

1/0/4/11/4 | 0/0/4/3/1 | 0/1/4/3/1 | 0.303 |

| Vibratory sensitivity evaluated by tuning fork | normal | normal | normal | NA |

| Ventilatory support | NA | All patients | All patients | NA |

| Nocturnal | NA | NIV n = 6 Tracheostomy n = 2 |

NIV n = 9 | NA |

| Diurnal | NA | Ventilation n = 1 Diaphragm pacing n = 1 | None | NA |

| Caregivers | NA | Parents n = 6 Partner n = 2 | Children n = 2 Partner n = 1 |

NA |

CH: Central Hypoventilation; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; BMI: body mass index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; NIV: non-invasive ventilation; NA: not applicable. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range (or number). p values in the rightmost column: Kruskal-Wallis test for all comparisons except for gender (Fisher’s exact test). Two-by-two comparison when the Kruskal-Wallis test was significant, as follows: ap < 0.05 for healthy subjects versus CH patients, bp < 0.05 for healthy subjects versus NIV, cp < 0.05 for CH patients versus NIV.

Vibrating wristband

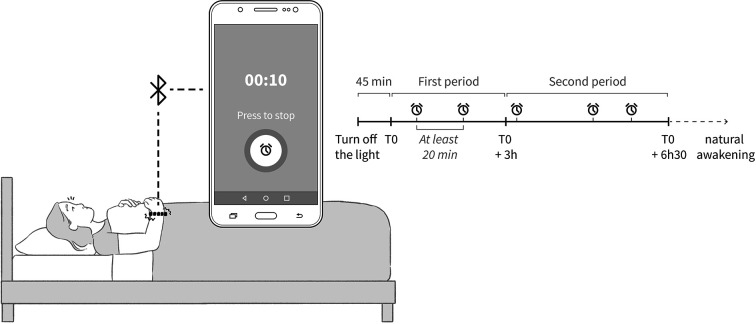

The device used in the study comprised: (i) a vibrating wristband (‘Feeltact’®, Novitact Lacroix Saint-Ouen, France), and (ii) a phone application (H2 AD, Saint-Jean-Bonnefonds, France) (see Figure 2). The phone application comprised a specific algorithm to trigger vibrating alarms at different stages of sleep during polysomnography. The vibrating alarm consisted of successive 6-second sequences separated by a 1-second pause. Each sequence consisted of a series of vibrations and pauses lasting half a second. The maximum alarm duration was 10 minutes. Five vibrating alarms were programmed during polysomnography, as shown in Figure 2. A minimum interval of 20 minutes was programmed between each alarm to give the participants time to go back to sleep. Moreover, to ensure that a sufficient number of alarms were triggered during slow-wave sleep, the first two alarms were programmed during the first 3 hours of sleep.

Figure 2.

Device used in the study including: (i) a vibrating wristband (‘Feeltact’®, Novitact Lacroix Saint-Ouen, France), and (ii) a phone application (H2 AD, Saint-Jean-Bonnefonds, France) comprising a specific algorithm to trigger vibrating alarms.

Polysomnography

Before undergoing polysomnography, the participants completed the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),4 the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)5 and a questionnaire about the quality of sleep during the previous night, comprising two questions (i) ‘how was the quality of your sleep last night?’ to which the patient had to answer by ‘very good, good, middling, bad, or very bad’, (ii) ‘how was the quality of your sleep compared to usual?’, to which the patient had to answer by: significantly better, better, similar, worse, significantly worse. The participants then underwent standard attended full-night video-polysomnography (Compumedics France SAS) with the vibrating wristband. Polysomnography was recorded in CH and COPD patients with their ventilatory support. Polysomnography included three EEG channels (Fp1/A2, C3/A2, C3/01), left and right electro-oculograms, surface electromyogram of mentalis, electrocardiogram, transcutaneous oxygen saturation, thoracic and abdominal efforts detected by belts, and measurement of airflow pressure using a nasal pressure transducer in healthy subjects and a mask pressure transducer in CH and COPD patients. Participants were informed that the wristband would be triggered five times during the PSG recording, but neither the investigator nor the participants would know at which time the alarms would be triggered. Participants were instructed to wear the wristband and switch it on by using a wireless connected mobile phone, just before turning off the lights and going to sleep Figure 2). Participants were instructed to stop each alarm by pressing the screen of the wireless connected mobile phone and to record the time on a sheet of paper. PSG recordings were scored manually according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines.6

Device acceptance

Wristband acceptance was assessed in the morning after polysomnography by means of: 1) one question ‘would you tolerate wearing this wristband every night if necessary?’, to which the patient had to answer: (i) Yes, I wouldn’t mind; (ii) Yes, if I had to; (iii) Yes, but it would be unpleasant; (iv) No, I would not tolerate wearing the wristband; and 2) two non-graduated 100-mm visual analogue scales (VAS). One VAS assessed anxiety relates to wearing the wristband and was anchored between ‘no anxiety at all’ and ‘extreme anxiety’. The second VAS assessed any unpleasant feelings related to wearing the wristband and was anchored between ‘no unpleasant feeling’ and ‘extremely unpleasant’. The results were expressed as a percentage of the full scale.

Endpoints

The sleep stage and the onset of EEG arousal were recorded for each alarm. The onset of clinical arousal, defined by at least one trunk lift visible on the video examination, and the onset of cognitive arousal, defined by a correct written record of the time, were also recorded. The primary endpoint was the proportion of alarms causing a cognitive arousal regardless of the stage of sleep. Secondary endpoints were the proportion of alarms causing: a cognitive arousal by stage of sleep, a clinical arousal regardless of the stage of sleep and by stage of sleep, an EEG arousal regardless of the stage of sleep and by stage of sleep. Other endpoints were the latencies of clinical and cognitive arousals, and the device acceptance scales.

Statistical analysis

As some variables did not have a normal distribution, all results are expressed as median and interquartile ranges [Q1; Q3]. For continuous variables, three-group comparisons were performed with a Kruskal-Wallis test followed, when significant, by a Mann-Whitney test for two-by-two group comparisons. For non-continuous variables, differences between the three groups were tested using Fisher’s exact test (3X2 followed by 2X2 contingency tables for two-by-two group comparisons). The level of significance was defined by a p-value <0.05

Results

Baseline characteristics and polysomnography

The three groups were comparable in terms of BMI and gender, but with a significantly younger median age in the CH group compared to the COPD group (Table 1). COPD patients reported significantly poorer sleep quality on the PSQI questionnaire, but no significant difference in terms of somnolence on the ESS and the quality of sleep during the night before polysomnography was observed between the two groups (Table 1). Polysomnographic recordings were obtained for all participants. Quality of sleep was normal in the healthy and CH groups and subnormal in the COPD group. The healthy group had a significantly higher sleep onset latency than the CH and COPD groups (first-night effect), with no significant difference between the two groups of patients (Table 2). COPD patients had a higher arousal index and a higher percentage of time with SpO2 <90% compared to healthy subjects. No significant difference was observed between the three groups for any of the other polysomnographic parameters, apart from a trend towards poorer sleep efficiency in the COPD group (Table 2). Of note, we ensured that all CH patients were adequately ventilated during sleep.

Table 2.

Polysomnographic data.

| Healthy subjects | CH patients | COPD patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sleep time (min) | 433 [403; 455] | 429 [401; 447] | 407 [391; 489] | 0,947 |

| Sleep Efficiency, (%) | 87 [80; 94] | 90 [86; 94] | 77 [68; 88] | 0.092 |

| Latency (min) | ||||

| Sleep onset | 28 [14; 36] | 10 [3; 17] | 12 [9; 27] | 0,010 a, b |

| N3 | 11 [11; 24] | 13 [10; 16] | 12 [8; 41] | 0,692 |

| REM Sleep | 99 [73; 142] | 83 [58; 118] | 135 [94; 174] | 0,316 |

| Sleep stages, (%) | ||||

| N1 | 2 [2; 3] | 2 [1; 4] | 2 [2; 2] | 0.724 |

| N2 | 54 [49; 60] | 58 [53; 60] | 53 [45; 60] | 0.643 |

| N3 | 20 [17; 22] | 22 [19; 24] | 25 [21; 27] | 0.238 |

| REM Sleep | 22 [20; 24] | 20 [15; 23] | 23 [17; 25] | 0.685 |

| Arousals (number/hour) | 6 [5; 9] | 11 [9; 13] | 10 [8; 19] | 0.045 b |

| AHI (number/hour) | 0.0 [0.0; 0.4] | 0.0 [0.0; 0.0] | 0 [0; 1] | 0.365 |

| 3% desaturation index (number/hour) | 0.0 [0.0; 0.3] | 0.0 [0.0; 0.1] | 0 [0; 1] | 0.897 |

| Time with SpO2 <90% (%) | 0.0 [0.0; 0.2] | 0.6 [0.0; 3.0] | 8 [1; 19] | 0.017 b |

CH: Central Hypoventilation; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; REM: rapid eye movements; AHI: apnoea-hypopnoea index. p values in the rightmost column: Kruskal-Wallis test for all three-group comparisons; two-by-two comparisons when the Kruskal-Wallis test was significant, as follows: ap < 0.05 for healthy subjects versus CH patients, bp < 0.05 for healthy subjects versus NIV. No significant difference was observed between CH and NIV groups.

Alarms

Five vibrating alarms were triggered during the PSG night for the majority of participants (n = 32). Due to technical problems (the subject omitted to activate the device or inappropriate device inactivation during the night), the number of alarms was less than 5 for 3 healthy subjects (no alarm in two cases, only three alarms in one case) and 2 COPD patients (one alarm and two alarms, respectively). Alarms occurred more frequently during a waking period after sleep onset in the COPD group, which presented poorer sleep efficiency. The number of alarms during PSG and by stage of sleep is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Arousal analysis.

| Healthy subjects n = 18* |

CH patients n = 8 |

COPD patients n = 9 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of alarms | ||||

| Polysomnography (including awakenings after sleep onset) | 88 | 40 | 38 | ns |

| Sleep (all stages) | 73 | 35 | 24 | 0.015 b, c |

| Stage N2 | 37 | 21 | 12 | 0.006 a, c |

| Stage N3 | 30 | 7 | 9 | |

| REM Sleep | 6 | 7 | 3 | |

| EEG arousals | ||||

| Proportion of EEG arousals (%) | ||||

| All stages of sleep | 100 | 83 | 75 | <0.01 a, b |

| Stage N2 | 100 | 86 | 92 | ns |

| Stage N3 | 100 | 71 | 44 | <0.01 a, b |

| REM Sleep | 100 | 86 | 100 | ns |

| Participants with EEG arousal for all alarms (n (%)) | 18 (100) | 5 (63) | 4 (44) | <0.01 a, b |

| Clinical arousals | ||||

| Proportion of clinical arousals (%) | ||||

| All stages of sleep | 99 | 69 | 71 | <0.01 a, b |

| Stage N2 | 100 | 76 | 83 | <0.01 a |

| Stage N3 | 97 | 43 | 44 | <0.01 a, b |

| REM Sleep | 100 | 71 | 100 | ns |

| Participants with clinical arousal for all alarms (n (%)) | 17 (94) | 4 (50) | 4 (44) | <0.01 a, b |

| Cognitive arousals | ||||

| Proportion of cognitive arousals (%) | ||||

| All stages of sleep | 94 | 66 | 63 | <0.01 a, b |

| Stage N2 | 92 | 71 | 75 | ns |

| Stage N3 | 97 | 43 | 33 | <0.01 a, b |

| REM Sleep | 83 | 71 | 100 | ns |

| Latency of arousal (seconds) | 52 [37; 80] | 83 [49; 122] | 118 [83; 169] | <0.001 a, b |

| Participants with cognitive arousal for all alarms | ||||

| Number (%) | 13 (72) | 3 (37.5) | 3 (33) | ns |

| Latency of arousal (seconds) | 50 [36; 69] | 51 [48; 88] | 136 [96; 177] | 0.03 b |

* Analysis of arousals was performed in 18 healthy subjects, as no alarm was triggered during polysomnography in the remaining 2 subjects.

CH: Central Hypoventilation; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; REM: rapid eye movements; ns: not significant. Data are expressed as median and interquartile range (or number). p values in the rightmost column: Kruskal-Wallis test or Fisher’s exact test. Two-by-two comparisons when Kruskal-Wallis or Fisher’s exact test was significant, as follows: ap < 0.05 for Healthy subjects versus CH patients, bp < 0.05 for Healthy subjects versus COPD patients, cp < 0.05 for CH patients versus COPD patients.

Arousal analysis

Due to the absence of alarm during PSG in 2 healthy subjects, analysis of results was based on 18 of the 20 subjects of this group. EEG, clinical arousal and cognitive arousal results are presented in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Proportion of cognitive, clinical and EEG arousals by groups. CH: central hypoventilation, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Failure of cognitive arousals in the CH group

Five patients failed to meet the criteria of cognitive arousal at least once. One patient with concurrent epilepsy did not experience any clinical arousal regardless of the stage of sleep, although he experienced three EEG arousals (two in N2, one in REM sleep, no EEG arousal in the remaining two alarms one in N2 and one in N3). A 34-year-old male patient experienced three cognitive arousals (one in N3 and 2 in N2), but no EEG arousal for another alarm in N2 (the fifth alarm occurred during a waking period). An 18-year-old male patient experienced four cognitive arousals, all in stage N2. For the fifth alarm, also in stage N2, he straightened his trunk, held the pen, but finally did not record the time on the sheet of paper (this event was considered to be a failure of cognitive arousal). A 19-year-old female patient experienced two cognitive arousals in REM sleep, but no clinical arousal in N2, N3 and REM sleep for the other three alarms (EEG arousal occurred for the N3 alarm). An 18-year-old female patient experienced one cognitive arousal in REM sleep, but no EEG arousal in N2 (one alarm) and N3 (one alarm); the remaining two alarms occurred during a waking period. Note that the wristband was too large for the two women.

Device acceptance

All participants declared that they would support wearing the device every night. However, one CH patient (12.5%) and 8 healthy subjects (40%) considered that it would be very unpleasant or that they would only wear the device if absolutely necessary. One (12.5%) patient with CH (VAS score of 10%) and 9 (45%) healthy subjects (median VAS score of 20% [15; 23]) considered that wearing wristband during the night was unpleasant. One (12.5%) patient with CH (VAS score of 30%) and 4 (20%) healthy subjects (median VAS score of 15% [10; 19]) reported anxiety. None of the COPD patients reported anxiety or unpleasantness related to wearing the wristband.

Discussion

This study shows that a vibrotactile stimulus can induce awakening in most healthy individuals. However, the device used in this study was significantly less effective to awaken CH and COPD patients compared to healthy subjects.

In our group of healthy subjects, the vibrating alarm was followed by a cognitive arousal in 94% of cases, and 13 of the 18 healthy subjects exhibited cognitive arousal in response to 100% of the alarms (optimal awakening profile). A clinical arousal was observed in 99% of cases, with 17 of the 18 healthy subjects exhibiting clinical arousal in response to 100% of the alarms regardless of the stage of sleep. A cortical (EEG) arousal was present in 100% of cases, suggesting that cortical arousal is the normal brain response to this type of stimulation. Failure to achieve cognitive arousal was therefore not due to the inability of brain to initiate the arousal, but rather to insufficient restoration of cognitive performance, characteristic of sleep inertia, a transitional period between sleep and full wakefulness that can last 15 to 30 minutes, comprising reduced alertness, cognitive impairment,7 and impaired flexible decision-making.8 Sleep inertia corresponds to progressive restoration of corticocortical connectivity9 and depends on individual factors7,10 Sleep inertia can be somewhat mitigated by ‘cognitive anticipation’ before bedtime. Healthy subjects also reported feeling less sleepy upon awakening after having been told that they would be awoken to perform a high-stress task than after having been told that they would be awoken to perform a low-stress task.11 In the same study, participants displayed better cognitive performance upon awakening in an ‘on call’ condition (expecting to be awoken during the night) than upon awakening in a control condition.11 We acknowledge that studying volunteers rather than actual caregivers is among the limitations of the study, and that, therefore, additional data need to be obtained in caregivers. It seems however reasonable to speculate that sleep inertia would be less marked in caregivers actually responsible for life-saving interventions in response to a ventilator alarm, especially when the expected interventions are clearly defined in a protocol and when the caregivers have been trained in these interventions. Of note, two of our healthy subjects were older than 60; one subject woke up with cognitive arousal in response to the five alarms and the other subject failed to wake up with cognitive arousal only once. We acknowledge that this is not sufficient to rule out the risk that an age-related decrease in sleep quality could negatively influence the awakening performances of the vibrotactile device. Complementary data will need to be obtained in a population of actual caregivers of older age.

An optimal awakening profile (cognitive arousal in response to 100% of alarms) was observed in only 37.5% of patients of the CH group. The awakening latency in these three patients was similar to that observed in healthy subjects. In three other patients, failure to achieve cognitive arousal could have been due to technical reasons (ill-fitting device in two cases) or pharmacological interference with awakening mechanisms (antiepileptic drug use in one case). In the remaining two patients, no cause for failure to achieve cognitive arousal was identified. CCHS itself could be associated with an altered awakening process, as supported by the absence of EEG arousal in the majority of cases when CCHS patients failed to wake up in response to vibrotactile stimulation. CCHS patients exhibit shorter slow-wave sleep (N3) latency than controls,12 suggesting that their cortical neurons are able to synchronize more rapidly during sleep, which could be due to an increased need for cortical restoration related to the abnormal respiratory-related motor cortical activity observed in these patients during wakefulness,13 and could be associated with awakening failures. The neuronal system responsible for awakening could be impaired in CCHS patients, as a result of either mutation-related effects altering the circadian rhythm14 or repeated hypoxic episodes.15,16 The brainstem dysfunction described in CCHS patients17 could also contribute to reduce the ability of the brain to manage the awakening process. More simply, chronically sleeping on mechanical ventilation could induce habituation to sensory stimuli (noise, leaks, alarms, tidal pressure variations) with concomitant elevation of the awakening threshold. Accordingly, 67% of the cognitive arousal failures and 85% of the clinical arousal failures recorded in COPD patients were also associated with failure of cortical arousal. Lastly, patients with CH have a lifetime experience of their parents managing ventilator alarms, which could also result in elevated awakening thresholds.

A previous study tested the ability of multimodal stimulation (including a vibrating pillow) to awaken healthy subjects,18 .with some positive results. However, this study did not use polysomnography to characterize sleep, but was based on actimetry, making it difficult to determine whether the subjects were actually asleep at the time of triggering of the devices, thereby complicating interpretation of the data. In addition, awakening was defined as a push-button response within the 10 minutes following initiation of the stimulus, which does not appear to be clinically relevant. Another study compared the pleasantness of various vibrotactile stimuli,3 but did not focus on awakening performances. In this study, continuous stimulation was more pleasant than discontinuous stimulation. Our device produces discontinuous stimulation, but was well tolerated by all participants, and only one patient described the device as being unpleasant. Our study appears to be the first study to characterize the awakening performances of a vibrotactile stimulus using both polysomnographic and behavioural criteria in both healthy subjects and patients requiring nocturnal mechanical ventilation. However, we acknowledge that no comparison of vibrotactile and auditory stimuli was performed in our study, which constitutes a significant limitation, as such a comparison of efficacy and tolerability would have been particularly useful. Although published data are available on the awakening efficacy of smoke alarms,19 we did not find any published data concerning the ability of ventilator audio alarms to awaken healthy individuals or patients.

Conclusions and perspectives

Our results do not support the use of vibrotactile stimulation alone to awaken ventilator-dependent patients, including CCHS patients. It would be useful to test the efficacy of vibrotactile stimulation combined with an audio alarm.3,20 Such multimodal stimulation could be easily triggered from recognition of the ventilator alarm.2 It could also be coupled with activation of a telemedicine platform to trigger an emergency call or external intervention in the absence of response to the alarm.

In contrast, our results support the notion that a vibrotactile stimulus could constitute an effective backup to a home mechanical ventilator audio alarm for healthy family caregivers, with corresponding benefits in terms of the burden of caregivers. Unresolved questions include the optimal vibrotactile stimulation protocol, the existence of habituation over time, comparison of the efficacy of vibrotactile stimulation with that of an audio alarm or multimodal stimulation, and whether or not age influences the response to vibrotactile stimulation during sleep. More generally, the impact of this type of device, whether used during wakefulness or during sleep, on the quality of life of family caregivers also needs to be studied.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mr Anthony SAUL, professional medical translator, for his help with English style and grammar, and Mrs Loan NGUYEN THANH LAN for Figures artwork.

Authors’ note: The Brassard study group comprises Saba Al-Youssef, Isabelle Arnulf, Valerie Attali, Benjamin Dudoignon, Nathalie Franckhauser, Didier Foret, Jesus Gonzalez-Bermejo, Antoine Guerder, Julien Hurbault, Sophie Lavault, Jean Malot, Sylvie Rouault, Thomas Similowski, Christian Straus, Jessica Taytard. The listed inventors of the patented BRASSARD device are underlined. VA and SL are both first authors. Address of the institution to which the work should be attributed: Sorbonne Université, INSERM, UMRS1158 Neurophysiologie Respiratoire Expérimentale et Clinique; AP-HP, Groupe Hospitalier Universitaire APHP-Sorbonne Université, site Pitié-Salpêtrière, Services des Pathologies du Sommeil et de Pneumologie, Médecine Intensive et Réanimation (Département R3S), 47-83 bd de l’hôpital 75013 Paris, France.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Sophie LAVAULT received a fee from ANTADIR as study coordinator; Thomas SIMILOWSKI and Christian STRAUS are listed as inventors of patent US9761112B2 ‘Assistance terminal for remotely monitoring a person connected to a medical assistance and monitoring device’ (not licensed). Others authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Association Nationale pour les Traitements À Domicile, les Innovations et la Recherche (ANTADIR) contributed to the funding of device development, funded the study and served as the study legal sponsor. The ‘Fondation Novartis de Proximologie’ (extinct) and H2AD (a telemedicine company, also extinct) also contributed to device development.

ORCID iD: Valerie Attali  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5444-9223

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5444-9223

References

- 1. Vanderlaan M, Holbrook CR, Wang M, et al. Epidemiologic survey of 196 patients with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol 2004; 37: 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Similowski T, Gonzalez-Bermejo J, Straus C, et al. Assistance terminal for remotely monitoring a person connected to a medical assistance and monitoring device. Patent version number US9761112B2. Paris, France: Université Pierre et Marie Curie; https://patents.google.com/patent/US9761112B2/en?oq=US9761112B2 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Korres G, Birgitte Falk Jensen C, Park W, et al. A vibrotactile alarm system for pleasant awakening. IEEE Trans Haptics 2018; 11(3): 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991; 14: 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1988; 28: 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, et al. AASM scoring manual updates for 2017 (version 2.4). J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13: 665–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trotti LM. Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day: sleep inertia and sleep drunkenness. Sleep Med Rev 2017; 35: 76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horne J, Moseley R. Sudden early-morning awakening impairs immediate tactical planning in a changing ‘emergency’ scenario. J Sleep Res 2011; 20: 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balkin TJ, Braun AR, Wesensten NJ, et al. The process of awakening: a PET study of regional brain activity patterns mediating the re-establishment of alertness and consciousness. Brain 2002; 125: 2308–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ohayon MM, Mahowald MW, Leger D. Are confusional arousals pathological? Neurology 2014; 83(9): 834–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kovac K, Vincent GE, Jay SM, et al. The impact of anticipating a stressful task on sleep inertia when on-call. Appl Ergon 2020; 82: 102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Attali V, Straus C, Pottier M, et al. Normal sleep on mechanical ventilation in adult patients with congenital central alveolar hypoventilation (Ondine’s curse syndrome). Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017; 12: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tremoureux L, Raux M, Hudson AL, et al. Does the supplementary motor area keep patients with Ondine’s curse syndrome breathing while awake? PLoS One 2014; 9: e84534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saiyed R, Rand CM, Carroll MS, et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS): circadian temperature variation. Pediatr Pulmonol 2016; 51: 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhu Y, Fenik P, Zhan G, et al. Selective loss of catecholaminergic wake active neurons in a murine sleep apnea model. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 10060–10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhan G, Serrano F, Fenik P, et al. NADPH oxidase mediates hypersomnolence and brain oxidative injury in a murine model of sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172: 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trang H, Masri Zada T, Heraut F. Abnormal auditory pathways in PHOX2B mutation positive congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. BMC Neurol 2015; 15: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Biffi E, Piazza C, Cavalleri M, et al. An assistive device for congenital central hypoventilation syndrome outpatients during sleep. Ann Biomed Eng 2014; 42: 2106–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bruck D, Ball M, Thomas I, et al. How does the pitch and pattern of a signal affect auditory arousal thresholds? J Sleep Res 2009; 18: 196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith GA, Splaingard M, Hayes JR, et al. Comparison of a personalized parent voice smoke alarm with a conventional residential tone smoke alarm for awakening children. Pediatr 2006; 118: 1623–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]