Abstract

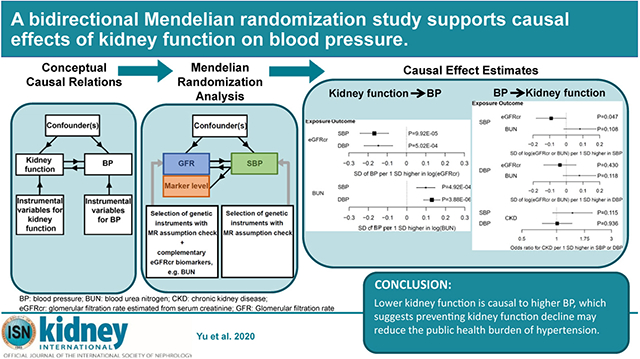

Blood pressure and kidney function have a bidirectional relation. Hypertension has long been considered as a risk factor for kidney function decline. However, whether intensive blood pressure control could promote kidney health has been uncertain. The kidney is known to have a major role in affecting blood pressure through sodium extraction and regulating electrolyte balance. This bidirectional relation makes causal inference between these two traits difficult. Therefore, to examine the causal relations between these two traits, we performed two-sample Mendelian randomization analyses using summary statistics of large-scale genome-wide association studies. We selected genetic instruments more likely to be specific for kidney function using meta-analyses of complementary kidney function biomarkers (glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine [eGFRcr], and blood urea nitrogen from the CKDGen Consortium). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure summary statistics were from the International Consortium for Blood Pressure and UK Biobank. Significant evidence supported the causal effects of higher kidney function on lower blood pressure. Based on the mode-based Mendelian randomization method, the effect estimates for one standard deviation (SD) higher in log-transformed eGFRcr was −0.17 SD unit (95 % confidence interval: −0.09 to −0.24) in systolic blood pressure and −0.15 SD unit (95% confidence interval: −0.07 to −0.22) in diastolic blood pressure. In contrast, the causal effects of blood pressure on kidney function were not statistically significant. Thus, our results support causal effects of higher kidney function on lower blood pressure and suggest preventing kidney function decline can reduce the public health burden of hypertension.

Keywords: biomarkers, blood pressure, chronic kidney disease, genome-wide association study, kidney function, Mendelian randomization

Graphical Abstract

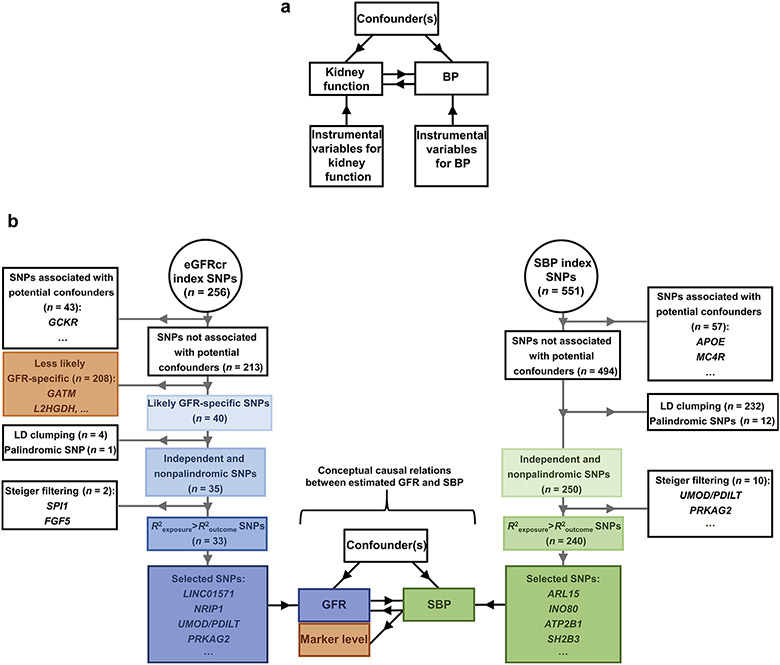

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are 2 interconnected global public health burdens. The estimated prevalence of hypertension is 31%, and CKD affects ~10% of adults.1-3 Both CKD and hypertension are major risk factors for cardiovascular disease and mortality.4-6 Blood pressure (BP) and kidney function have a bidirectional relation. Hypertension has long been considered as a risk factor for kidney function decline on the basis of observational studies.7-10 However, it is uncertain whether intensive BP control could promote kidney health on the basis of the results from randomized controlled trials.11,12 On the relation between kidney function decline and higher BP, 2 observational studies reported a significant association between lower kidney function and incident hypertension. However, the kidney function biomarkers with the significant association were cystatin C and β2 microglobulin whereas serum creatinine, the most commonly used kidney function biomarker, was not significant.13,14 These inconsistent results make inferring the causal relation between BP and kidney function difficult. Evaluating the causal relations between kidney function and BP (Figure 1a) can inform disease prevention and treatment strategies.15

Figure 1 ∣. (a) The hypothesized bidirectional relations between kidney function and blood pressure (BP) depicted in a directed acyclic graph (DAG) in which the black arrows represent causal relations.

In our study, the primary kidney function measures were glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimated from serum creatinine and not measured directly. Adapted from Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:R89–R98.15 © The Author 2014. Published by Oxford University Press. (b) Selection of genetic instruments for GFR estimated from serum creatinine (eGFRcr) and systolic blood pressure (SBP), our primary traits. The centered graph represents the conceptual causal relations (black arrows) between estimated GFR and SBP, similar to the DAG in (a), except that estimated GFR levels were calculated from serum creatinine and therefore has 2 parts: a GFR and a biomarker-level component. The diagrams on the 2 sides with gray arrows represent the process of genetic instrument selection. LD, linkage disequilibrium; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Mendelian randomization (MR) is an approach using genetic variants as instrumental variables of the exposure to estimate causal effects of the exposure on an outcome overcoming the confounding inherent in observational studies.15 Two-sample MR analysis is an extension of the MR method that allows the use of summary statistics of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) for MR studies without directly analyzing individual-level data. Using two-sample MR analysis, Liu et al. found causal effects of systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) on CKD.16 Morris et al. reported a significant causal effect of lower kidney function on higher DBP and not on SBP.17 Taking advantage of the recent large-scale meta-analysis of the GWAS of kidney function that included complementary glomerular filtration rate (GFR) biomarkers, we performed two-sample MR analyses to evaluate the potential bidirectional causal relation between kidney function and BP. The primary kidney function trait was estimated GFR from serum creatinine (eGFRcr),18 with blood urea nitrogen (BUN) as a secondary trait. The primary BP trait was SBP, with DBP as a secondary trait.

To obtain robust conclusions from our analyses, we paid particular attention to 2 critical aspects in this MR study. One aspect is the use of serum creatinine for GFR estimation, which might link eGFRcr to genetic variants related to creatinine metabolism and not GFR, making it difficult to interpret any causal relations between eGFRcr and BP. To address this issue, we used data from a large-scale meta-analysis of the GWAS of BUN, a complementary GFR biomarker, to select genetic instruments that are more likely to be specific to kidney function. The second aspect is the assumption of the lack of horizontal pleiotropy of the genetic instruments; that is, the genetic instruments must be associated with the outcome through the exposure only. This assumption is difficult to assess and verify.19 To address this issue, we used multiple MR methods and prioritized the method that are known to be robust to the presence of horizontal pleiotropy and the influence of outlying genetic instruments.20

RESULTS

Summary of population characteristics

The meta-analysis of the GWAS of kidney function included largely adult population–based cohorts (among cohorts in the Chronic Kidney Disease Genetic [CKDGen] Consortium; median age, 50.1 years; median of male percentage, 48.2; median eGFRcr, 91.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2; n = 567,460 for eGFRcr and n = 243,031 for BUN) (Table 1).21,22 The meta-analysis of the GWAS of BP also included largely population-based cohorts (mean age, 54.9 years for the International Consortium for Blood Pressure [ICBP] and 56.8 years for the UK Biobank [UKB]; male percentage, 44.9 for ICBP and 45.8 for UKB; mean SBP, 134.3 mm Hg for ICBP and 141.1 mm Hg for UKB; n = 299,024 for ICBP and n = 458,577 for UKB; Table 1).

Table 1 ∣.

Basic characteristics of the studies that contributed summary statistics of kidney function (CKDGen) and blood pressure (ICBP-UK Biobank)

| Characteristica | CKDGen | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 567,460 | |

| Age (yr), median | 50.1 | |

| Male percentage | 48.2 | |

| eGFRcr (ml/min per 1.73 m2), median | 91.4 | |

| CKD percentage | 8.6 | |

| Characteristicb | ICBP | UK Biobank |

| Sample size | 299,024 | 458,577 |

| Age (yr), mean | 54.9 | 56.8 |

| Male percentage | 44.9 | 45.8 |

| SBP (mm Hg), mean | 134.3 | 141.1 |

| DBP (mm Hg), mean | 80.6 | 84.3 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; CKDGen, Chronic Kidney Disease Genetics; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ICBP, International Consortium for Blood Pressure; eGFRcr, estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated from serum creatinine; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The basic characteristics of the studies participated in the CKDGen Consortium were calculated as the weighted average of the characteristics of each study reported in Wuttke M, Li Y, Li M, et al. A catalog of genetic loci associated with kidney function from analyses of a million individuals. Nat Genet. 2019;51:957–972,21 with the study-specific sample size as the weight.

The basic characteristics of the studies participated in the ICBP were calculated as the weighted average of the characteristics of each study, with the study-specific sample size as the weight. These study-specific characteristics and the UK Biobank characteristics were reported in Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–1425.22

Selection of genetic instruments for kidney function

The genetic instruments for kidney function were selected from the summary statistics of the meta-analysis of the GWAS of European-ancestry participants from the CKDGen Consortium.22 Of the 256 reported index single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of eGFRcr, after the removal of SNPs associated with potential confounders (see Methods; Supplementary Table S1), 213 index SNPs remained (Figure 1b; Supplementary Table S2). Using BUN as the complementary kidney function marker, we retained 40 index SNPs on the basis of their association with BUN having direction consistency in kidney function and satisfying the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (see Methods; Supplementary Table S3). For example, the index SNP at GATM, which encodes an enzyme in creatine metabolism,23 was removed because of an insignificant association with BUN (rs1145077; eGFRcr, P = 6.9 × 10−142; BUN, P = 0.92). After pairwise linkage disequilibrium clumping and matching of the coding allele between the summary statistics of the exposure and those of the outcome, 35 index SNPs remained. Finally, Steiger filtering removed the index SNPs at FGF5 and SPI1 (Supplementary Table S4), resulting in 33 genetic instruments for eGFRcr, which explained 1.33% of the variance of log(eGFRcr). None of these 33 genetic instruments were associated with the urinary sodium-to-creatinine ratio or urinary potassium-to-creatinine ratio at the genome-wide significance level (P < 5 × 10−8) in a large-scale GWAS of UKB participants (n = 327,613) (Supplementary Table S5).24 Using similar selection procedures, the number of genetic instruments retained for BUN was 24, which explained 1.18% of the variance of log(BUN). For example, using eGFRcr as the complementary kidney function biomarker, the BUN index SNP at SLC14A2, a urea transporter,25,26 was removed because of an insignificant association with eGFRcr (rs41301139; P = 0.14) (Supplementary Table S6). The numbers of SNPs retained after each selection step are reported in Supplementary Table S7.

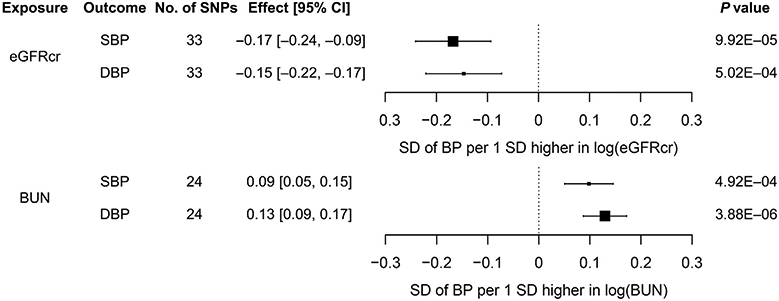

Significant causal effect of kidney function on BP

We identified significant evidence of causal effects of higher kidney function on lower BP. Using weighted mode, our primary method, we observed that the estimates of causal effect for each SD higher log(eGFRcr) were −0.17SD in SBP (95% confidence interval, −0.24 to −0.09; P = 9.92 × 10−5) and −0.15SD in DBP (95% confidence interval, −0.22 to −0.07; P = 5.02 × 10−4) (Figure 2). These causal effects were equivalent to 10% higher eGFRcr, leading to 2.35 mm Hg lower SBP and 1.14 mm Hg lower DBP. If the relation between eGFRcr and BP is linear,27,28 a 50% lower eGFRcr would lead to 17.5 mm Hg higher SBP and 8.4 mm Hg higher DBP. We also observed significant causal effects of BUN, the secondary kidney function trait, on SBP and DBP (weighted mode method: SBP, P = 4.92 × 10−4; DBP, P = 3.88 × 10−6). Using other MR methods—inverse variance–weighted fixed-effects (IVW-FE) method, MR-Egger, weighted median, and MR analysis using mixture models29-32—all estimates of causal effect were in the same direction as of those from weighted mode and statistically significant, providing support for causal effects of lower eGFRcr on higher SBP and DBP (Supplementary Table S8). Analysis using the Mendelian randomization pleiotropy residual sum and outlier (MR-PRESSO) method with the explicit removal of outlying instruments showed similar results (Supplementary Table S9). The scatter plots with the regression line from all MR methods are shown in Supplementary Figures S1A to S4A. The forest plots of single SNP effects from each of the kidney function traits to each of the BP traits are shown in Supplementary Figures S1B to S4B. Multiple sensitivity analyses resulted in similar estimates of causal effect of kidney function on BP (Supplementary Tables S10 and S11 and Supplementary Results).

Figure 2 ∣. Estimates of causal effect of log(glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine [eGFRcr]) and log(blood urea nitrogen [BUN]) on systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) calculated using the weighted mode method.

CI, confidence interval.

Selection of genetic instruments for SBP and DBP

The genetic instruments for SBP and DBP were selected from the summary statistics of the meta-analysis of GWAS from the UKB-ICBP collaboration.22 Of the 551 reported index SNPs of SBP, after the removal of SNPs associated with potential confounders, linkage disequilibrium clumping, and matching of the coding allele, 250 index SNPs remained (Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S7; Figure 1b). When eGFRcr was used as the outcome, Steiger filtering removed 10 SBP index SNPs including those at UMOD/PDILT and PRKAG2 (Supplementary Table S4), resulting in 240 genetic instruments for SBP, explaining 2.46% of the variance of SBP. Of the 537 reported DBP index SNPs, after the removal of SNPs associated with potential confounders, linkage disequilibrium clumping, and matching of the coding allele, 250 remained (Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S7). When eGFRcr was used as the outcome, Steiger filtering removed 8 DBP index SNPs including those at UMOD/PDILT and PRKAG2 (Supplementary Table S4), resulting in 234 genetic instruments for DBP, explaining 2.85% of the variance of DBP. With the same SNP selection algorithms, 248 genetic instruments for SBP and 237 genetic instruments for DBP were selected when CKD was the outcome and 243 genetic instruments for SBP and 233 genetic instruments for DBP were selected when BUN was the outcome (Supplementary Tables S4 and S7).

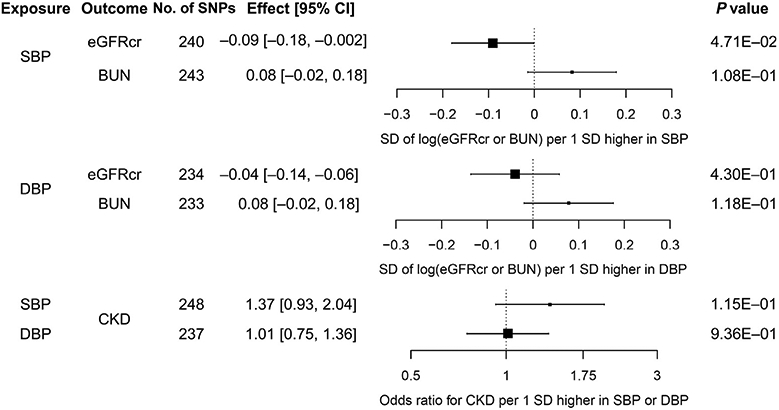

Estimates of causal effect of BP on kidney function

Using weighted mode, our primary method, we observed that the estimates of causal effect of BP on kidney function were generally not significant, accounting for multiple testing (P < 0.025; see Methods). The estimate of causal effect for each SD higher SBP was −0.09SD log(eGFRcr) (95% confidence interval, −0.18 to −0.002; P = 4.71 × 10−2) (Figure 3; Supplementary Table S8). This estimate is equivalent to 10 mm Hg higher SBP, leading to 0.6% lower eGFRcr. The estimates of causal effect of SBP on eGFRcr from other MR methods were also modest (10 mm Hg higher SBP for <1% difference in eGFRcr). Similar nonsignificant and modest estimates of causal effect were observed for DBP on the 3 kidney function outcomes—eGFRcr, CKD, and BUN—using weighted mode as well as MR analysis using mixture models, one of the methods most robust to horizontal pleiotropy (Supplementary Table S8).33 In contrast, using IVW-FE, the estimates of causal effect were significant across both SBP and DBP on kidney function outcomes. The results of MR-PRESSO, an extension of IVW-FE with outlier removal, were consistent with the IVW-FE results (Supplementary Table S9). The scatter plots with the regression line from all MR analyses are shown in Supplementary Figures S5A to S10A. The forest plots of single SNP effects from BP traits to kidney function traits are shown in Supplementary Figures S5B to S10B. Sensitivity analysis using BP summary statistics from UKB only as the exposure resulted in similar estimates of causal effect for SBP and DBP on eGFRcr, BUN, and CKD (Supplementary Table S10).

Figure 3 ∣. Estimates of causal effect of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) on log(glomerular filtration rate estimated from serum creatinine [eGFRcr]), log(blood urea nitrogen [BUN]), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) calculated using the weighted mode method.

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Extensive MR analyses, based on the GWAS summary statistics with the largest sample sizes available to date for kidney function and BP, showed evidence of a causal effect of kidney function on BP. Specifically, we observed that 50% lower eGFRcr results in 17.5 mm Hg higher SBP and 8.4 mm Hg higher DBP. In contrast, the causal effect of BP on kidney function was not supported across MR methods. The significant causal effect of lower kidney function on higher BP suggests that preventing kidney function decline can reduce the public health burden of hypertension.

Kidney function is difficult to measure and is generally estimated using biomarkers.34 The systematic measurement errors in GFR estimation due to the biomarker pose challenges for the study of kidney function, particularly for early kidney function decline using eGFRcr because the systematic measurement errors increase as GFR approaches or is within the normal range.18 In 2 population-based association studies that reported a significant association between lower kidney function and incident hypertension, the kidney function biomarkers with the significant association were cystatin C and β2 microglobulin whereas serum creatinine, the most commonly used GFR biomarker, was not significant.13,14 In this MR study, we used a novel approach of combining GFR biomarkers in selecting the genetic instruments for kidney function to overcome the systematic measurement errors in eGFRcr and found significant causal effects of lower kidney function on higher BP at the population level. This finding is consistent with the important physiological role of the kidney in affecting BP through the regulation of sodium excretion and electrolyte balance35 as well as with the genetics of hypertension-attributed kidney disease in African Americans, in whom the APOL1 high-risk genotype confers twice the risk of CKD progression and appears to directly affect kidney function rather than BP.36-38

Our study extends previous MR studies of the causal effect of kidney function on BP. A significant bidirectional causal relation between higher albuminuria, an indicator of kidney damage, and higher SBP and DBP has been reported using the large-scale UKB data.39 In contrast, the causal effects of eGFRcr on SBP and DBP had inconsistent results. Morris et al. reported a significant causal effect of eGFRcr on DBP but not on SBP.17 Our study used a complementary GFR biomarker approach to identify genetic instruments that were more likely to be specific for GFR and found robust causal effects of eGFRcr on both SBP and DBP.

On the causal effect of BP on kidney function, significant causal effects of higher SBP and DBP on CKD have been reported using the IVW-FE method, which requires a strong assumption on the sum of horizontal pleiotropy to be zero to provide consistent estimates.40 In our study, the IVW-FE method also provided significant estimates of causal effect of SBP and DBP on CKD, with effect sizes similar to those reported previously.16 If the assumption on horizontal pleiotropy of the IVW-FE method is valid, the IVW-FE method would be more powerful. Given the substantial heterogeneity of the effect of the genetic instruments for BP on kidney function, the horizontal pleiotropy assumption of the IVW-FE method may not hold. Across all methods, the effect estimates of BP on kidney function were small (< 1% difference in eGFRcr per 10 mm Hg difference in SBP). Our inconclusive MR results of the causal effect of BP on kidney function might be due to measurement inaccuracies in kidney function contributed by GFR biomarkers, leading to a dilution of the estimates of causal effect. Another potential source of these inconclusive results might be the ability of the kidney to adapt to small differences in BP.41,42 Some have hypothesized that only severe hypertension would lead to kidney function decline.43 It should also be noted that our results mirror, to some extent, the results of BP control from randomized controlled trials, which have failed to show consistent protective effects of kidney function, particularly within the trial period.44-46

Our use of Steiger filtering, which compared the effect size of a genetic instrument for the exposure and outcome, suggested that some kidney function loci may affect kidney function through BP, such as FGF5, and some BP loci may affect BP through kidney function, such as UMOD, which expresses exclusively in the kidney.47 These results provide insight into the potential pleiotropy underlying GWAS findings of these traits.

Our study has several strengths. First, we used a novel approach of combining GFR biomarkers to select genetic instruments that are more likely to be specific to kidney function to overcome measurement inaccuracies in kidney function contributed by GFR biomarkers. Second, we used summary statistics of large-scale GWASs. Lastly, to reduce the possibility of violating the assumptions of MR, we used a range of techniques: the evaluation of the association of index SNPs with potential confounders, the use of Steiger filtering to reduce potential reverse causation driven by genetic instruments, and a selection of a primary method that is robust to the presence of pleiotropy accompanied by sensitivity analysis using alternative methods.

Some limitations warrant mentioning. The MR approach uses genetic instruments to represent lifelong differences in exposure levels for estimating causal effects on an outcome. Developmental adaptation could alter the effect of the genetic instruments on the outcome.48 The two-sample MR methods rely on GWAS summary statistics and assume a linear relationship between the exposure and the outcome. We did not evaluate a potential nonlinear relationship between kidney function and BP or investigate potential mechanisms linking kidney function and BP, such as sodium and potassium handling. In our primary analysis, cohorts in the CKDGen Consortium and UKB-ICBP collaboration had some overlap, which might lead to bias in the estimates of causal effect.49 However, our results using nonoverlapping populations in exposure and outcome (CKDGen Consortium and UKB only) were similar to those of our primary analysis. The CKDGen Consortium populations included studies of CKD patients and children, who were a small proportion of the overall study population. Overall, the populations in the summary statistics for exposures and outcomes were similar.50

In summary, using a novel approach that combines GFR biomarkers for selecting genetic instruments for kidney function, we found that lower kidney function is causal to higher BP. This result suggests that preventing kidney function decline may reduce the public health burden of hypertension.

METHODS

Study design overview

We performed two-sample MR analyses to estimate the causal effects of kidney function on BP, and vice versa. The primary kidney function trait was eGFRcr, with BUN as a secondary trait. CKD, defined as eGFRcr < 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, was a secondary outcome.21 The primary BP trait was SBP, with DBP as a secondary trait.51 Published GWAS summary statistics were obtained from the meta-analysis of the GWAS of European-ancestry participants from the CKDGen Consortium21 for kidney function and from the UKB-ICBP collaboration22 for BP. Genotypes in the GWASs were imputed using the Haplotype Reference Consortium52 or the 1000 Genomes Project53 reference panels. All GWAS summary statistics assumed an additive genetic model.

Summary statistics of kidney function from the CKDGen Consortium

The meta-analysis of the GWASs of eGFRcr included 54 cohorts of European ancestry (n = 567,460), largely adult population–based (Table 1). A small proportion of participants were from cohorts of CKD patients, diabetes patients, or children (2.5%). The meta-analysis of the GWASs of BUN included 48 cohorts of European ancestry (n = 243,031), and the analysis of CKD included 444,971 participants. eGFRcr was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation18 for adults and the Schwartz formula54 for participants who were 18 years or younger. BUN, the secondary kidney function trait, was derived as blood urea × 2.8 mg/dl.21 The phenotypes used in the GWAS of eGFRcr and BUN were the natural log–transformed age- and sex-adjusted residuals of the traits. The basic characteristics of the CKDGen Consortium studies were summarized as weighted averages across studies with the sample size as the weight by using summary data reported in Wuttke et al.21

Summary statistics of BP from the UKB-ICBP collaboration

Summary statistics of BP traits were obtained from the meta-analysis results from the UKB-ICBP collaboration.32 UKB is a population-based cohort.55 SBP and DBP were calculated as the mean of 2 automated or manual BP measurements, except for participants with 1 BP measurement (n = 413). The GWASs of SBP and DBP from UKB included 458,577 participants of European ancestry. The meta-analysis of the GWASs of SBP and DBP from ICBP included 77 cohorts of European ancestry (n = 299,024).51 In both UKB and ICBP, the values of SBP and DBP were adjusted for the use of BPlowering medications by adding 15 and 10 mm Hg, respectively.22,56 The characteristics of the ICBP studies were summarized as weighted averages across studies with the sample size as the weight by using summary data reported in Evangelou et al.22

MR assumptions

Genetic instruments in MR studies rely on 3 assumptions: (i) the SNP must be associated with the exposure; (ii) the SNP is independent of confounders, that is, other factors that can affect the exposure-outcome relation; and (iii) the SNP must be associated with the outcome through the exposure only, that is, no direct association due to horizontal pleiotropy.48

Selection of genetic instruments more likely to be related to kidney function

To ensure that the genetic instruments satisfied the first assumption with respect to kidney function, we selected index SNPs associated with multiple GFR biomarkers, so that they are more likely to be related to kidney function, the exposure of interest, rather than GFR biomarkers. For the primary analysis using eGFRcr, we started with the index SNPs of the genome-wide significant loci of the meta-analysis of the GWAS of eGFRcr of European-ancestry participants from the CKDGen Consortium.21 We first evaluated the association of index SNPs with potential confounders using the GWAS summary statistics from UKB for the following traits: prevalent diabetes, body mass index, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, smoking, and prevalent coronary heart disease (Supplementary Table S1).1,57,58 We removed index SNPs, with genome-wide significant associations (5 × 10−8) with the potential confounders listed above.1,57,59

Next, we used genetic association information of BUN,21 an alternative biomarker of kidney function, to select genetic instruments that were more likely to reflect kidney function as opposed to creatinine metabolism. This approach was similar to the approach in Wuttke et al. for prioritizing genetic loci most likely to be relevant for kidney function.21 We required eGFRcr index SNPs to be associated with BUN at a Bonferroni-corrected significance (P < 0.05 divided by the number of eGFRcr index SNPs) and in the opposite direction because higher GFR would lead to lower BUN. To ensure independence among genetic instruments, we applied linkage disequilibrium clumping60 with a clumping window of 10 MB and an r2 cutoff of 0.001 (default of the ld_clump function).60 The matching of the effect allele of each SNP between the summary statistics of the exposure and those of the outcome was examined using the harmonise_data function, which removed SNPs that were palindromic or had possible strand mismatch. Finally, to reduce the possibility that a genetic instrument might affect the outcome independently of the exposure, we applied Steiger filtering to ensure that the association between a genetic instrument and the exposure was stronger than its association with the outcome.61

To select genetic instruments for BUN, the secondary kidney function trait, we started with index SNPs from the GWAS of BUN and followed a similar procedure of selection described above. We used their association with eGFRcr for screening out those index SNPs that might be related only to metabolism of BUN but not to kidney function.

Selection of genetic instruments for BP

For BP traits, we started with index SNPs from genome-wide significant loci of SBP or DBP reported by the UKB-ICBP collaboration22 and applied the same steps as described above for eGFRcr, without the alternative biomarker step. Briefly, we removed index SNPs that were associated with potential confounders listed above, removed correlated SNPs using the ld_clump function,60 used the harmonise_data function to remove SNPs that were palindromic or had possible strand mismatch between the summary statistics of the exposure and those of the outcome, and, finally, applied Steiger filtering.61

Use of the robust method to account for horizontal pleiotropy

Some methods for MR analysis can be heavily biased in the presence of a direct association of SNP with the outcome that is not mediated by the exposure.62 When the direct effects of genetic instruments on the outcomes and exposures are correlated across different instruments because of the presence of unobserved confounders that may have heritable components, the bias can be severe.33 To reduce the possibility that the genetic instruments might affect the outcome independently of the exposure, in addition to the use of Steiger filtering,61 we chose the weighted mode method, one of the most robust in the presence of horizontal pleiotropy,33,40 as our primary MR method. In addition, we performed sensitivity analysis using alternative methods that may be more powerful under various model assumptions (see Supplementary Methods). Given our primary analyses estimate the causal effects of eGFRcr on SBP, and vice versa, the significance level for MR analysis was set at P < 0.025 (=0.05/2).

Units of estimates of causal effect, variance explained by genetic instruments, and sensitivity analyses

For continuous exposures and outcomes, we estimated the causal effects of 1SD difference in exposure levels on the outcome. The SD of each trait was estimated on the basis of data from population-based cohorts. The details are given in Supplementary Methods.

Details of the calculation of exposure variance explained by genetic instruments, power analysis, and sensitivity analysis are given in Supplementary Methods. All analyses were conducted using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 3.5.3), and the “TwoSampleMR” package was used for all MR analyses, except MR analysis using mixture models.

Data sharing

All the summary-level data used are available for download at the public repositories.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Source and sample size of GWAS summary statistics of potential confounders.

Table S2. Index SNPs significantly associated with potential confounders.

Table S3. Association of 213 eGFRcr index SNPs with BUN in the meta-analysis of CKDGen European ancestry cohorts (eGFRcr n = 567,460, BUN n = 243,031).

Table S4. SNPs excluded as genetic instruments due to having potential reverse causal direction (exposure r-squared ≤ outcome r-squared) based on Steiger filtering.

Table S5. Association of the 33 genetic instruments of eGFRcr with urine sodium-to-creatinine ratio and urine potassium-to-creatinine ratio in large scale GWAS of UKB participants (N=327,613, Zanetti et al.24).

Table S6. Association of 58 BUN index SNPs with eGFRcr in the meta-analysis of CKDGen European ancestry cohorts (BUN n = 243,031, eGFRcr n = 567,460).

Table S7. Numbers of index SNPs retained after in each step of selecting genetic instruments.

Table S8. Results of MR analysis of kidney function and BP by primary and secondary methods using CKDGen and UKB-ICBP summary statistics.

Table S9. Causal effect estimates from MR-PRESSO for primary analysis: eGFRcr on SBP and SBP on eGFRcr.

Table S10. Sensitivity analysis results using non-overlapping samples from CKDGen and UKB.

Table S11. Sensitivity analysis results using eGFRcys as the alternative biomarker for kidney function for selecting GFR genetic instruments.

Figure S1. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from eGFRcr on SBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from eGFRcr on SBP.

Figure S2. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from eGFRcr on DBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from eGFRcr on DBP.

Figure S3. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from BUN on SBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from BUN on SBP.

Figure S4. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from BUN on DBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from BUN on DBP.

Figure S5. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on eGFRcr. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on eGFRcr.

Figure S6. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on CKD. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on CKD.

Figure S7. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on BUN. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on BUN.

Figure S8. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on eGFRcr. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on eGFRcr.

Figure S9. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on CKD. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on CKD.

Figure S10. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on BUN. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on BUN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Chronic Kidney Disease Genetic Consortium (https://ckdgen.imbi.uni-freiburg.de), the UK Biobank (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/), and the International Consortium for Blood Pressure-Genome Wide Association Studies for publicly sharing the genetic data we used in our causal analysis.

AK was supported by a Heisenberg professorship (KO 3598/3-1, 3598/5-1) as well as CRC 1140 project number 246781735 and CRC 992 of the German Research Foundation. NC was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute grant R01 HG010480-01. AT was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin grant R01 AR073178-01A1. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study was funded by HHSN268201100009C. The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

All the authors declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;382:158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister SE, Boger CA, Kramer BK, et al. Effect of chronic kidney disease and comorbid conditions on health care costs: a 10-year observational study in a general population. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:222–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2034–2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2073–2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017;317:165–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelton PK, Klag MJ. Hypertension as a risk factor for renal disease: review of clinical and epidemiological evidence. Hypertension. 1989;13(5 suppl):I19–I27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson AH, Yang W, Townsend RR, et al. Time-updated systolic blood pressure and the progression of chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:258–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Z, Rebholz CM, Wong E, et al. Association between hypertension and kidney function decline: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74:310–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judson GL, Rubinsky AD, Shlipak MG, et al. Longitudinal blood pressure changes and kidney function decline in persons without chronic kidney disease: findings from the MESA Study. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:600–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beddhu S, Rocco MV, Toto R, et al. Effects of intensive systolic blood pressure control on kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in persons without kidney disease: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X, Atkins E, Lv J, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering on cardiovascular and renal outcomes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;387:435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang M, Matsushita K, Sang Y, et al. Association of kidney function and albuminuria with prevalent and incident hypertension: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:58–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kestenbaum B, Rudser KD, de Boer IH, et al. Differences in kidney function and incident hypertension: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23: R89–R98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu HM, Hu Q, Zhang Q, et al. Causal effects of genetically predicted cardiovascular risk factors on chronic kidney disease: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Genet. 2019;10:415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris AP, Le TH, Wu H, et al. Trans-ethnic kidney function association study reveals putative causal genes and effects on kidney-specific disease aetiologies. Nat Commun. 2019;10:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemani G, Bowden J, Davey Smith G. Evaluating the potential role of pleiotropy in Mendelian randomization studies. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27: R195–R208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qi G, Chatterjee N. Mendelian randomization analysis using mixture models for robust and efficient estimation of causal effects. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuttke M, Li Y, Li M, et al. A catalog of genetic loci associated with kidney function from analyses of a million individuals. Nat Genet. 2019;51:957–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evangelou E, Warren HR, Mosen-Ansorena D, et al. Genetic analysis of over 1 million people identifies 535 new loci associated with blood pressure traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1412–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Item CB, Stockler-Ipsiroglu S, Stromberger C, et al. Arginine:glycine amidinotransferase deficiency: the third inborn error of creatine metabolism in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1127–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanetti D, Rao A, Gustafsson S, et al. Identification of 22 novel loci associated with urinary biomarkers of albumin, sodium, and potassium excretion. Kidney Int. 2019;95:1197–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olives B, Martial S, Mattei MG, et al. Molecular characterization of a new urea transporter in the human kidney. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CP, Fenton RA. Genomic organization of the mammalian SLC14a2 urea transporter genes. J Membr Biol. 2006;212:109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaes B, Beke E, Truyers C, et al. The correlation between blood pressure and kidney function decline in older people: a registry-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindeman RD, Tobin JD, Shock NW. Association between blood pressure and the rate of decline in renal function with age. Kidney Int. 1984;26: 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt AF, Dudbridge F. Mendelian randomization with Egger pleiotropy correction and weakly informative Bayesian priors. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47:1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, et al. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi G, Chatterjee N. Mendelian randomization analysis using mixture models (MRMix) for genetic effect-size-distribution leads to robust estimation of causal effects. Nat Coomun. 2019;10. article ID 1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi G, Chatterjee N. A comprehensive evaluation of methods for Mendelian randomization using realistic simulations and an analysis of 38 biomarkers for risk of type-2 diabetes [e-pub ahead of print]. bioRxiv. 10.1101/702787. Accessed July 16, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Levey AS, Inker LA. GFR as the “gold standard”: estimated, measured, and true. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wadei HM, Textor SC. The role of the kidney in regulating arterial blood pressure. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heymann J, Winkler CA, Hoek M, et al. Therapeutics for APOL1 nephropathies: putting out the fire in the podocyte. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:i65–i70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopp JB. Rethinking hypertensive kidney disease: arterionephrosclerosis as a genetic, metabolic, and inflammatory disorder. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22:266–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas ME, Aragam KG, Emdin CA, et al. Genetic association of albuminuria with cardiometabolic disease and blood pressure. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:461–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1985–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlstrom M, Wilcox CS, Arendshorst WJ. Renal autoregulation in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:405–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey AS, Gansevoort RT, Coresh J, et al. Change in albuminuria and GFR as end points for clinical trials in early stages of CKD: a scientific workshop sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation in collaboration with the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:84–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stengel B. Hypertension and glomerular function decline: the chicken or the egg? Kidney Int. 2016;90:254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang TI, Sarnak MJ. Intensive blood pressure targets and kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:1575–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai WC, Wu HY, Peng YS, et al. Association of intensive blood pressure control and kidney disease progression in nondiabetic patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:792–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grassi G, Mancia G, Nilsson PM. Specific blood pressure targets for patients with diabetic nephropathy? Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 2): S228–S233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, et al. Proteomics: tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng J, Baird D, Borges MC, et al. Recent developments in Mendelian randomization studies. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4:330–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burgess S, Davies NM, Thompson SG. Bias due to participant overlap in two-sample Mendelian randomization. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hartwig FP, Davies NM, Hemani G, et al. Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;45:1717–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ehret GB, Ferreira T, Chasman DI, et al. The genetics of blood pressure regulation and its target organs from association studies in 342,415 individuals. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1171–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1279–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.1000 Genomes Project Consortium, Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwartz GJ, Schneider MF, Maier PS, et al. Improved equations estimating GFR in children with chronic kidney disease using an immunonephelometric determination of cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2012;82:445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tobin MD, Sheehan NA, Scurrah KJ, et al. Adjusting for treatment effects in studies of quantitative traits: antihypertensive therapy and systolic blood pressure. Stat Med. 2005;24:2911–2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hallan SI, Orth SR. Smoking is a risk factor in the progression to kidney failure. Kidney Int. 2011;80:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.UK Biobank. GWAS results: GWAS round 2. Available at: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- 59.Orth SR, Hallan SI. Smoking: a risk factor for progression of chronic kidney disease and for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in renal patients—absence of evidence or evidence of absence? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hemani G, Tilling K, Davey Smith G. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1007081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, et al. Sensitivity analyses for robust causal inference from Mendelian randomization analyses with multiple genetic variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Source and sample size of GWAS summary statistics of potential confounders.

Table S2. Index SNPs significantly associated with potential confounders.

Table S3. Association of 213 eGFRcr index SNPs with BUN in the meta-analysis of CKDGen European ancestry cohorts (eGFRcr n = 567,460, BUN n = 243,031).

Table S4. SNPs excluded as genetic instruments due to having potential reverse causal direction (exposure r-squared ≤ outcome r-squared) based on Steiger filtering.

Table S5. Association of the 33 genetic instruments of eGFRcr with urine sodium-to-creatinine ratio and urine potassium-to-creatinine ratio in large scale GWAS of UKB participants (N=327,613, Zanetti et al.24).

Table S6. Association of 58 BUN index SNPs with eGFRcr in the meta-analysis of CKDGen European ancestry cohorts (BUN n = 243,031, eGFRcr n = 567,460).

Table S7. Numbers of index SNPs retained after in each step of selecting genetic instruments.

Table S8. Results of MR analysis of kidney function and BP by primary and secondary methods using CKDGen and UKB-ICBP summary statistics.

Table S9. Causal effect estimates from MR-PRESSO for primary analysis: eGFRcr on SBP and SBP on eGFRcr.

Table S10. Sensitivity analysis results using non-overlapping samples from CKDGen and UKB.

Table S11. Sensitivity analysis results using eGFRcys as the alternative biomarker for kidney function for selecting GFR genetic instruments.

Figure S1. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from eGFRcr on SBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from eGFRcr on SBP.

Figure S2. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from eGFRcr on DBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from eGFRcr on DBP.

Figure S3. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from BUN on SBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from BUN on SBP.

Figure S4. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from BUN on DBP. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from BUN on DBP.

Figure S5. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on eGFRcr. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on eGFRcr.

Figure S6. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on CKD. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on CKD.

Figure S7. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from SBP on BUN. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from SBP on BUN.

Figure S8. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on eGFRcr. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on eGFRcr.

Figure S9. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on CKD. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on CKD.

Figure S10. (A) Regression lines of MR tests from DBP on BUN. (B) Forest plot of single SNP from DBP on BUN.