Abstract

Radiation-induced cutaneous injury is the main side effect of radiotherapy. The injury is difficult to cure and the pathogenesis is complex. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) serve as a promising candidate for cell-based therapy for the treatment of cutaneous wounds. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether antler stem cells (AnSCs) have better therapeutic effects on radiation-induced cutaneous injury than currently available ones. In this study, a rat model of cutaneous wound injury from Sr-90 radiation was used. AnSCs (1 × 106/500 μl) were injected through the tail vein on the first day of irradiation. Our results showed that compared to the control group, AnSC-treated rats exhibited a delayed onset (14 days versus 7 days), shorter recovery time (51 days versus 84 days), faster healing rate (100% versus 70% on day 71), and higher healing quality with more cutaneous appendages regenerated (21:10:7/per given area compared to those of rat and human MSCs, respectively). More importantly, AnSCs promoted much higher quality of healing compared to other types of stem cells, with negligible scar formation. AnSC lineage tracing results showed that the injected-dye-stained AnSCs were substantially engrafted in the wound healing tissue, indicating that the therapeutic effects of AnSCs on wound healing at least partially through direct participation in the wound healing. Expression profiling of the wound-healing-related genes in the healing tissue of AnSC group more resembled a fetal wound healing. Revealing the mechanism underlying this higher quality of wound healing by using AnSC treatment would help to devise more effective cell-based therapeutics for radiation-induced wound healing in clinics.

Keywords: antler stem cells, radiation, cutaneous injury, wound healing

Introduction

Cutaneous wound healing is a body’s stopgap measure that quickly restores the skin barrier in order to reduce the risk of infection and further injury1. As a trade-off for speed, even under optimal conditions, wound healing normally leads to fibrosis or a scar formation2. A number of approaches have thus far been attempted to try to achieve an optimal outcome of healing, regeneration of the normal architecture, and function of the skin1,3. Among these approaches, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with their unique properties are emerging as a promising candidate for cell-based therapy for the treatment of cutaneous wounds4,5.

It has been accepted that the therapeutic effects of MSCs rely on their ability of self-renewal, multi-differentiation potency, and secretion of paracrine factors that can enhance tissue regeneration; modulate the local environment; and stimulate the proliferation, migration, differentiation, survival, and functional recovery of the residential cells6,7.

Radiation-induced cutaneous injury occurs while treating many different types of cancer, although radiation contributes to 40% of curative cancer treatments8,9. It is reported that radiotherapy significantly injures the skin and profoundly impairs skin function10, hence limits the duration and dosage of radiation. Pathophysiological changes in radiation-induced cutaneous injury occur within hours or weeks, as well as dermal atrophy and telangiectasia, which occur over the long term11. MSC treatment has been found to be a promising therapeutic approach to improve radiation-induced normal tissue damage, hence can take radiotherapy further12,13.

Although bone marrow and adipose tissue have proven to be the primary sources for majority of MSC types, search for alternative and more effective sources of MSCs has never ceased14. These new sources include placenta, umbilical cord blood, peripheral blood, and medical waste materials15. The need for better source of MSCs is because none of them is perfect, and each has slightly different effects on different phases of wound healing. For example, Wharton’s jelly-derived MSCs have more capacity for sweat gland cell differentiation16; bone marrow–derived MSCs could promote skin regeneration through accelerating tissue expansion17.

Stem cells (AnSCs) from growing antler are an innovative and good candidate for the treatment of cutaneous wounds. These include antlerogenic periosteal cells that are responsible for a deer pedicle and the first antler development, pedicle periosteal cells that are responsible for annual antler renewal, and reserve mesenchymal cells that are responsible for antler’s rapid growth (up to 2 cm/day). Studies show that AnSCs are unique in that they can not only promote perfect cutaneous wound healing (healing tissue consists of hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and blood vessels) very fast (healing of a wound with the diameter exceeds 10 cm within a week) but also initiates full regeneration of antlers (a bony organ) immediately following completion of wound healing18. Characterization work confirms that in addition to expressing classical MSC markers (such as CD44, CD73, CD90, and CD105)19, AnSCs also express some key embryonic stem cell markers (such as Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, telomerase, and nucleostemin20,21). The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the AnSCs have a better regeneration capacity than currently available ones using a radiation-induced cutaneous injury model. Our study clearly demonstrated that AnSCs had better therapeutic effects than rat bone marrow–derived MSCs and umbilical cord MSCs on healing of radiation-induced wounds in rats. These results are extremely promising for the translation of the full regenerative healing property of the AnSCs to clinics and ultimately benefit for cancer patients.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Expansion of Stem Cells

Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hU-MSCs) were isolated from umbilical cord tissue of normal caesarean birth according to previously described methods22. Briefly, collagenase and hyaluronidase were used to digest the umbilical cord after the outside skin was removed. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (rB-MSCs) were obtained from femur bone marrow of 4-week-old male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats and characterized as previously described23. In brief, the femurs and tibias of rats were excised. The operation was carried out with careful removal of all connective tissue attached to bones. Both ends of these bones were cut, and bone marrow cells were obtained by carefully flushing the bone cavity with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) using a 23G syringe. Collagenase I and II were used to digest the flush-out. AnSCs were obtained from a 2-year-old male sika deer as described previously24. Detailed procedures for AnSC isolation and culture were described in our previous study25. Briefly, the distal 3 cm of the growing antler tip was collected, and the reserve mesenchyme (RM) layer tissue was surgically dissected and cut into 1 mm3 pieces for primary cell culture. Collagenase I and II were used to digest the RM tissues. Each solution of hU-MSCs, rB-MSCs, and AnSCs was centrifuged at 224×g for 5 min to remove digestive enzyme and plated onto 75 cm2 culture flasks and cultured in an amplification medium, a low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, San Francisco, CA, USA) at 37°C with saturated humidity and 5% CO2. After 48 h, the nonadherent cells were removed through medium washing; thereafter, the culture medium was changed twice a week. The isolated hU-MSCs and rB-MSCs were confirmed using the methods reported in our previous publication26. The cells were passaged using trypsin (Sigma) and stored in the freezing medium (DMEM:FBS:DMSO = 6:3:1) in liquid nitrogen. When required, each cell type was thawed and cultured in T75 flasks. The fourth passage for each type of stem cells was used in this study. AnSCs, hU-MSCs, and rB-MSCs were fully characterized in our previous studies19,21,26,27 and summarized here in Supplemental Table S1.

Proliferation Assay for Each Stem Cell Type

Each of the three types of stem cells was seeded into the six-well plates at a density of 10/well in triplicates, respectively. The cells were harvested every 4 days with trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Thermal Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and counted using a hemocytometer for up to eight passages. The mean value of the cell number was calculated out from three wells for each stem cell type. The mean population doubling time was determined according to the following formula: population doubling time = T × lg2/ (lgNt − lgN0), where T is the culture time, N0 is the cell number at initial seeding, and Nt is the cell number at harvested.

Animals and Treatments

Eight-week-old female SD rats were purchased from Jilin Experimental Animal Co., Ltd. (Jilin, China). All the protocols and procedures were approved by the Animal Experiment Ethic Committee of Jilin University (Approval No. XYSK2017-0043). The animal model was established according to the previously published methods28 with some modifications. In brief, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral hydrate (500 μl/100 g), and hairs on the hind quarters of the rats were shaved using a razor. Rats were irradiated using a β-ray beam (Sr90) on the shaved area at irradiation dose of 50 Gy in an area of 2 cm × 2 cm for 30 min. This dose was selected because it can significantly induce cutaneous injury with almost 100% success rate with only one dose based on our previous experience. A 3-cm-thick piece of lead was used to shield the area outside the defined area (2 cm × 2 cm). The irradiated animals were randomly divided into five groups (six rats/group): Control, AnSCs, rB-MSCs, hU-MSCs, and AnSCs-tracing. Rats in each stem-cell-treatment group was given the fourth passage cells (1 × 106/500 μl) via injection through the tail vein on the first day after irradiation. This cell quantity was selected for injection based on our previous publication29. The control group was injected with equivalent amount of physiological saline at the same time, and the Intact group (three rats) was put aside without any treatment for an extra control. The rats in the experiment were euthanized on day 71 after the irradiation. In the AnSCs-tracing group, the dye-labeled cells (1 × 106/500 μl; see below) were injected via rat tail veins at the time when skin ulcers started to appear on the irradiated area in the AnSCs group rats. In the AnSCs-tracing group, the rats were euthanized on day 7 (three rats) and day 14 (three rats) after cell injection, respectively.

Only one cell type, AnSCs, was selected for cell lineage tracing in this study. AnSCs were labeled with a protein dye CFSE (carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester) for living cell staining following the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Briefly, AnSCs (1 × 106) were added into a 15 ml centrifuge tube containing 1 ml CFSE and incubated for 10 min at 37°C before 10 ml culture medium (containing 10% FBS) was added into the tube. After properly mixing through inversion, the tube was centrifuged to remove supernatant (300 g). The precipitated cells were washed once in 10 ml culture medium before suspended in 10 ml culture medium and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. After one more wash with medium, the CFSE-labeled AnSCs were counterstained with a nucleic acid dye DAPI [2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride] following the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime Biotechnology). Briefly, the cells were transferred into another 15 ml centrifuge tube containing 1 ml DAPI, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, centrifuged (300 g) to remove supernatant, and the precipitated cells were washed three times in 10 ml physiological saline each time. Finally, the CFSE-DAPI-labeled AnSCs were suspended in 500 µl physiological saline for rat tail vein injection. The reason for selecting these two time points (7 and 14) for tissue sampling in the cell-tracing group is mainly based on the information provided by the dye manufacturer that in vivo injected CFSE-labeled cells can be unambiguously traced within a month provided these cells are nondividing. The wound healing tissues were sampled immediately after euthanization, embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek O.C.T. Compound 4583), cut at 5 μm, and observed/photographed under a fluorescent microscope (Olympus M50, Tokyo, Japan).

Skin Injury Assessment

Skin damage was photographically recorded three times a week and measured in a double blinded manner. Skin injuries were assessed at regular intervals using a semi-quantitative skin injury score as previously described (Table 1)30 from 1 (no damage) to 5 (severe damage).

Table 1.

Semi-quantitative Skin Damage Scores.

| Score | Skin changes |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | No damage |

| 1.5 | Minimal erythema, mild dry skin |

| 2.0 | Moderate erythema, dry skin |

| 2.5 | Marked erythema, dry desquamation |

| 3.0 | Dry desquamation, minimal dry crusting |

| 3.5 | Dry desquamation, dry crusting, superficial minimal scabbing |

| 4.0 | Patchy moist desquamation, moderate scabbing |

| 4.5 | Confluent moist desquamation, ulcers, large deep scabs |

| 5.0 | Open wound, full thickness skin loss |

Cited from Kohl et al30.

Wound Contraction Assessment

Photographs were taken three times a week and wound area was measured and calculated each time. The wounds were traced on clear autoclaved plastic, and the images were scanned and used to calculate wound area (Scion image analysis software, National Institute of Health, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, US). Wound closure rate was expressed as percentage relative to the original wound size, calculated as follows: wound closure rate (%) = [(wound area on 1st day − wound area on Nth day)/wound area on 1st day] × 100.

Histological Analysis of Healed Skin

Rats of the four groups were sacrificed on day 71 after irradiation. The stem-cell-treatment groups were found to be healed completely within 10 weeks, whereas the control group healed within 12 weeks. Healed tissue samples from the irradiated region were surgically taken, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma). Epidermal and dermal (from dermal–epidermal junction to the top of the subcutaneous fatty layer) thickness was measured under a microscope. The skin thickness was calculated using the 10 consecutive optical fields (three sites/fields) in each skin sample. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Number of the cutaneous appendages was counted manually in the 10 randomly selected optical fields. Cutaneous appendage separated by connective tissue on one microscope sphere was counted as one unit.

Immunohistochemistry

The healed skin tissue samples (taken from day 71 after irradiation) were cut into sections at 4 µm thickness for immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining. IHC was carried out using the Kit (Maixin KIT-9710, Fuzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in a 99°C water bath for 15 min, then 3% H2O2 was added to each of these sections for 15 min, and 10% normal goat serum added to block nonspecific bindings for 1 h at 37°C. Next, the tissue sections were incubated with primary antibody of either anti-α-SMA or anti-Ki-67 (1:500 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C and replaced with biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody for 2 h. After washing, diaminobenzidine solution was used as the chromogenic agent for 15 min at 37°C and sequentially incubated with avidin peroxidase reagent. Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Specific staining in the tissue sections was examined/photographed under a microscope (Olympus M50, Tokyo, Japan). Ten fields per section and 10 sections per tissue were randomly selected (n = 6 rats) for quantification of Ki-67 positive area. The Ki-67-stained area was calculated using Image-Pro Plus.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis

Total RNA from each healing tissue sample (collected on day 71 after irradiation) was extracted with TRIzol (Thermal Scientific). Four pieces of tissues were taken along the diagonal lines from the healed skin in each irradiated area. One of four pieces was used for RNA extraction. The mRNAs were reverse transcribed into cDNA using an oligo (dT)12 primer and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermal Scientific). SYBR green dye (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was used for amplification of cDNA. The levels of the following molecules were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) in triplicates: Col1A2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor2 (FGF2), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein (IL-1rap), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1), and the internal standard B2 M mRNA. The primer sequences designed for measuring these molecules are listed in Table 2. The expression levels of mature mRNA were quantified by qRT-PCR according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Gene Pharma, Shanghai, China). Briefly, 2 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), after which they were amplified and detected using qPCR with specific primer probes. Thermo cycler conditions included an initial step at 95°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Expression levels were recorded as cycle threshold (Ct). Data were acquired using the 7500 Software (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). All reactions were performed in triplicates and the data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Table 2.

Primers Used for qRT-PCR.

| Gene name | Primers | Sequences | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B2M | Forward | gctccttttgtggctgga | 151 |

| Reverse | aagacgccaggtttgctg | ||

| Col1A2 | Forward | ggtgcccctggagagaat | 158 |

| Reverse | ggaccagcagacccaatg | ||

| VEGF | Forward | tgcttcctagtgggctctgt | 250 |

| Reverse | gatgcgaatcctttccaaaa | ||

| FGF2 | Forward | agcggctctactgcaagaac | 183 |

| Reverse | gccgtccatcttccttcata | ||

| HGF | Forward | cgagctatcgcggtaaagac | 165 |

| Reverse | tgtagctttcaccgttgcag | ||

| IL-1rap | Forward | gtcacccctgaggatctgaa | 199 |

| Reverse | ggaccatctccagccagtaa | ||

| TGFβ1 | Forward | atacgcctgagtggctgtct | 153 |

| Reverse | tgggactgatcccattgatt | ||

| MMP1 | Forward | gctttggcttccctagcagtg | 201 |

| Reverse | tcgcctttttggaaaacatc | ||

| TIMP1 | Forward | catggagagcctctgtggat | 210 |

| Reverse | atggctgaacagggaaacac |

FGF2: fibroblast growth factor 2; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; IL-1rap: interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein; MMP1: matrix metalloproteinase 1; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TIMP1: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc.). Multiple comparisons were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Student’s t-test. All quantitative data expressed as mean ± standard deviation. P-values < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

AnSCs Proliferated Faster than hU-MSCs and rB-MSCs In Vitro

The three stem cell populations (AnSCs, hU-MSCs, and rB-MSCs) were cultured to passage 8. The cell doubling times of the hU-MSCs, rB-MSCs, and AnSCs were found to be 42, 38, and 32 h, respectively. The doubling times at different passages of AnSCs are relatively constant, but significantly shorter when compared to the correspondent passages of either hU-MSCs or rB-MSCs (Fig. 1A; Table 3; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). When cultured to passage 8, the AnSCs displayed the highest cumulated cell numbers among the three (Fig. 1B; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Therefore, the AnSCs had the fastest proliferation rate in vitro compared to the other two stem cell types.

Figure 1.

Comparison of proliferation rate among the three stem cell types. Number of the stem cells was counted following each subculture from one to eight passages. (A) The population doubling time was calculated based on cell counts (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (B) The data were shown as cumulative cell numbers at each passage. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 when compared to AnSC group, n = 3; mean ± SD. Each column represents the mean of the three stem cell populations with SD. AnSC: antler stem cell; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3.

Summary of the MSCs on Healing Course of the Wounds Caused by Radiation Injury.

| Doubling time (h) | Skin injury scorea | Wound duration (day) | Wound area (cm2) on day 71 | Wound closure rate (%)b | Cutaneous appendage (per area) | Level of gene expression | Vessel number | Ki-67 positive area (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnSCs | 32 | 1.25 | 51 | 0 | 100 | 21 |

FGF2, HGF, VEGF, MMP1 TGF-β1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1 FGF2, HGF, VEGF, MMP1 TGF-β1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1 |

23.4 | 1.16 |

| rB-MSCs | 38 | 2.25 | 61 | 0.09 | 97.8 | 10 |

FGF2, VEGF, MMP1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1 FGF2, VEGF, MMP1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1 |

17.5 | 2.52 |

| hU-MSCs | 42 | 2.83 | 73 | 0.29 | 92.7 | 7 |

FGF2, VEGF, MMP1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1

FGF2, VEGF, MMP1 Col1A2, Col3A1, IL1rap, TIMP1 |

12.3 | 3.62 |

| Control | NA | 3.50 | 84 | 1.20 | 70.0 | 2 | — | 3.2 | 6.14 |

AnSCs: antler stem cells; FGF2: fibroblast growth factor 2; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; hU-MSCs: human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells; IL-1rap: interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein; MMP1: matrix metalloproteinase 1; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; qRT-PCR: quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; rB-MSCs: rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TIMP1: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

a Skin injury score on day 51 was used when the most obvious difference was observed.

b Wound area and closure rate calculated on day 71 after radiation.

Effects of the AnSCs on Rat Cutaneous Wound Healing Compared to the hU-MSCs and rB-MSCs

Each Phase of Wound Healing Course

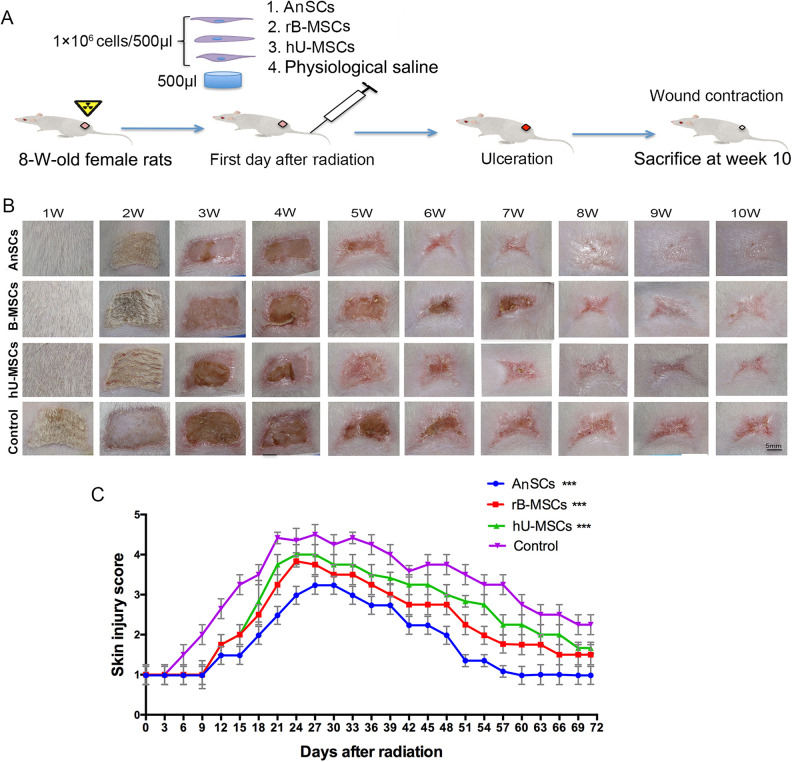

A Sr-90 irradiation on the hind quarters of SD rats was conducted, and followed by different stem cell injection through the tail vein on the day of irradiation (Fig. 2A). We observed that cutaneous damage occurred on days 6–12 after irradiation and reached maximum on day 24 (Fig. 2B, C). The epilation and depigmentation occurred the earliest in the control group on day 7 (±2 days) after irradiation, followed by the hU-MSC and rB-MSC groups, respectively; the latest one was in the AnSC group that occurred on day 14 (±2 days). Furthermore, damage to the skin and ulceration were visible in the control group on day 18 (±3 days). Dry desquamation, crusting, and superficial minimal scabbing appeared in the hU-MSC and rB-MSC groups on day 24 (±2 days), and reached the maximum skin injury score at this point, after which the scores declined. However, these skin changes occurred latest in the AnSC group (Fig. 2B, C) on day 28 (±3 days). We compared all the time points in the healing course among these animal groups (Fig. 2C) and found that from day 6, all three stem-cell-treatment groups had significant lower scores than the control group (P < 0.001, Fig. 2C and Table 1). This indicates that MSCs have the ability to delay occurrence of skin damage and promote fast wound healing, but AnSCs were the most potent MSCs for treating irradiated-wound healing.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of the wound healing course. (A) Experimental procedures. (B) Gross morphological changes during wound occurring and healing. (C) Skin injuries were assessed using a semi-quantitative skin damage scores, with scores of 1.0 (no damage)–5.0 (severe damage). From day 15, all three stem-cell-treatment groups showed the lower scores than the control (***P < 0.001); n = 6; mean ± SD. SD: standard deviation.

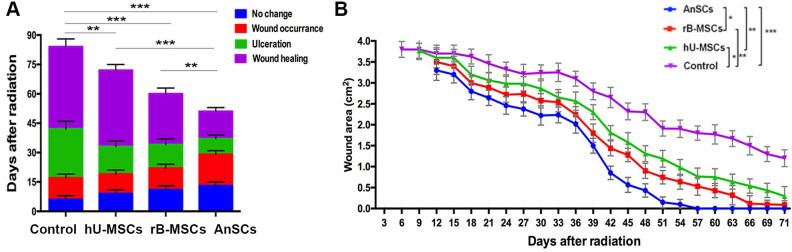

Morphologically, wounds in the control group were completely healed on day 84 (±3 days), whereas the rB-MSC and hU-MSC groups healed on day 61 (±3 days, P < 0.001) and day 73 (±3 days, P < 0.01), respectively. The AnSC group had shortest period of healing time, on day 51 (±3 days, P < 0.001; Fig. 3A, B), and significantly shorter than those of the hU-MSC (P < 0.001) and rB-MSC (P < 0.01) groups (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the AnSCs are the best stem cells used in the present study for ameliorating radiation-induced cutaneous injury in rats.

Figure 3.

Effects of stem cells on wound healing process and wound closure. (A) The accumulative column represents the time course of each cutaneous injury phase. (B) Changes in wound area during the course of wound closure. Multiple comparisons were made by one-way ANOVA. Data are reported as mean ± SD, n = 6. Dramatic wound area difference was found on day 39 as shown in top right corner (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). However, from days 27 to 54, the wound area was much smaller in the AnSC group than those of all other three groups (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001). From days 18 to 57, all the stem cell groups showed the significant lower wound areas than the control (P < 0.05 to P < 0.001); n = 6; mean ± SD. ANOVA: analysis of variance; AnSC: antler stem cell; SD: standard deviation.

Wound Closure Rate

The results from the wound size measurements to all four groups showed that the rapid wound closure period fell within 33–51 days (Fig. 3B). More than 90% of wound closure was achieved in the rB-MSC and hU-MSC groups, but only 70% in the control group within 71 days (±3 days). Wound closure was completed in the AnSC group within 57 days (±3 days; Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that wound healing rate of the AnSC group is the highest among all groups (*P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

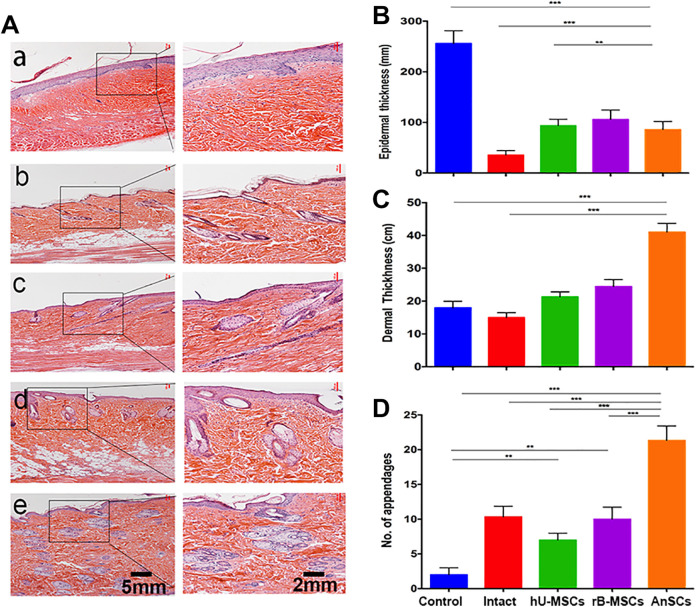

Wound Healing Quality

Histological results showed that skin of the Intact rat group had thinnest epidermis and dermis, and moderate number of cutaneous appendages (Fig. 4Ab). Healed skin in the control group had thickened epidermis, thin dermis, barely observable cutaneous appendages, and irregular cell arrangements (Fig. 4Aa). However, healed skin from the stem-cell-treatment groups showed features were more resemble to those of the Intact group. In the rB-MSC and hU-MSC groups, the healed skin had thin epidermis, more numbers of hair follicles, sweat and sebaceous glands (P < 0.01), and regular cell arrangements than the control group (Fig. 4Ac-d, B–D). However, healed skin in the AnSC group was the closest to the normal skin: thin epidermis, regularly distributed cutaneous appendages including sebaceous and sweat glands, and regular alignment of fibers in the dermis (Fig. 4Ae, B-4D). Based on these histological observations, healed skin tissue in the AnSC group was the most resemblance to the normal skin, with more cutaneous appendages regenerated than rB-MSC (P < 0.001) and hU-MSC (P < 0.001) groups. All these data further demonstrate that the AnSCs could enhance healing quality of irradiation-induced cutaneous injury.

Figure 4.

Effects of the stem cells on histological structures of the healed skin tissue. (A) a–e: Control, Intact, hU-MSCs, rB-MSCs, and AnSCs, respectively. (B–D) Evaluation of epidermal and dermal thickness, and number of cutaneous appendages in the healed wound skin. Intact was taken from the same area as the other groups but without radiation. n = 6; mean ± SD (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). AnSCs: antler stem cells; hU-MSCs: human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells; rB-MSCs: rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; SD: standard deviation.

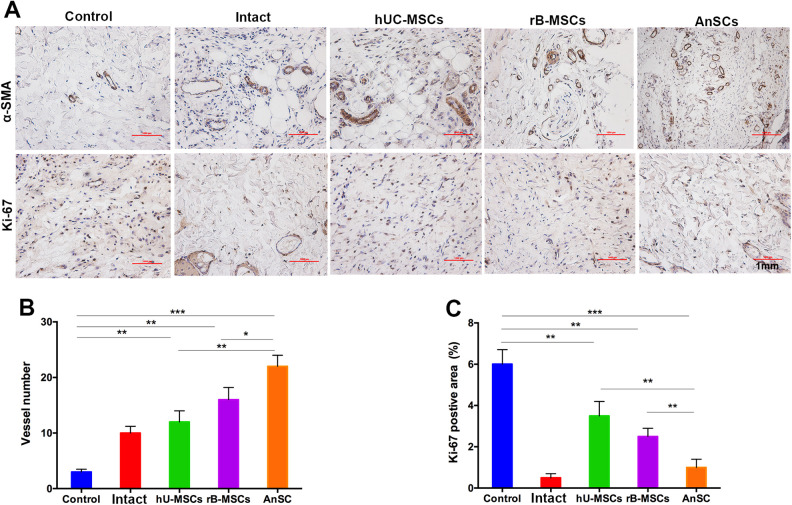

The IHC results showed that on day 71, AnSCs group had the highest blood vessel numbers (22.45 ± 3.21) compared to the rest of four groups (control, 3.12 ± 0.56; Intact, 9.43 ± 1.24; hU-MSCs, 12.25 ± 1.94; rB-MSCs, 16.42 ± 2.13; P < 0.005, Fig. 5A, B). In addition, AnSCs treatment had the least percentage of the Ki-67 positive area (1.12 ± 0.45) compared to the rest of four groups (control, 5.94 ± 0.74; Intact, 0.52 ± 0.23; hU-MSCs, 3.48 ± 0.69; rB-MSCs, 2.53 ± 0.46; P < 0.01, Fig. 5A, C). These results suggest that the AnSC enhanced healing of irradiation-induced wounds in rats may be partially through stimulating angiogenesis. With regard to the reduction of proliferation of dermal fibroblasts may be either due to advanced completion of wound healing in the AnSC group compared to the rest of groups, inhibition effects on fibroblast mitosis through which could reduce scar tissue formation, or both.

Figure 5.

IHC evaluation of the wound healing quality. (A) Number of vessels/field (×100) in the healing tissue. (B) Positive staining area for Ki-67 analyzed using Image-Pro Plus. Note that AnSCs group had the highest number of vessels, but the least Ki-67 positive cells (on day 71 when wound healing reaching completion) compared to the rest of four groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, bar = 1 mm; n = 6; mean ± SD. α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; AnSCs: antler stem cells; IHC: immunohistochemistry; SD: standard deviation.

On Gene Expression in the Healed Tissues

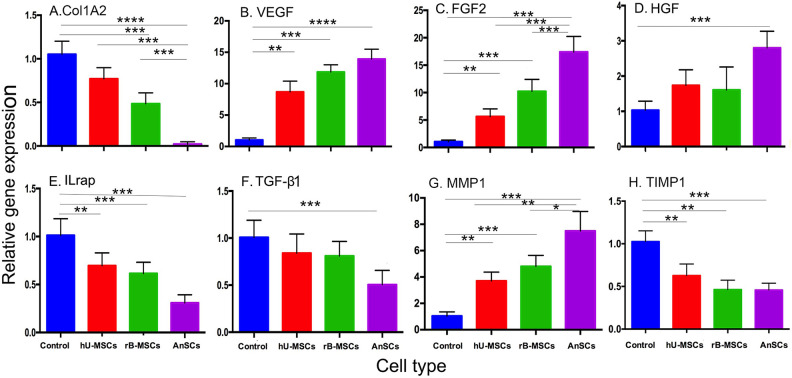

Expression analyses to some wound-healing-related genes were carried out on the healed skin tissues in this study. The results showed that the expression levels of Col1A2 (Fig. 6A), IL-1rap (Fig. 6E), TGF-β1 (Fig. 6F), and TIMP1 (Fig. 6H) in the three stem cell treatment groups were significantly decreased when compared to those of the control group (P < 0.001 or P < 0.0001), while the expression levels in the AnSC group were the lowest (Fig. 6). In contrast, the expression levels of VEGF (Fig. 6B), FGF2 (Fig. 6C), HGF (Fig. 6D), and MMP1 (Fig. 6G) were significantly increased when compared to the control group (P < 0.001 or P < 0.0001), while the expression levels in the AnSC group were the highest (Fig. 6). All these gene profiling results support the conclusion that MSC treatments significantly enhanced the wound healing quality and healing rate when compared to the control group, and the AnSCs were the best among these used MSCs.

Figure 6.

Gene expression profiling of the healing skin tissue. Note that expression levels of the genes pro-wound healing in the MSC-treatment groups were all increased compared to the control group, whereas those of anti-wound healing in the MSC-treatment groups were all decreased compared to the control group. n = 6; mean ± SD (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001). FGF2: fibroblast growth factor 2; HGF: hepatocyte growth factor; IL-1rap: interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein; MMP1: matrix metalloproteinase 1; MSC: mesenchymal stem cell; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor-β1; TIMP1: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

AnSCs Lineage Tracing

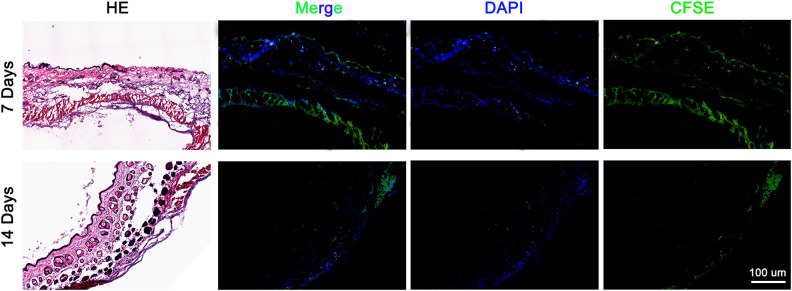

To find out whether the injected-dye-labeled AnSCs directly participated in the wound healing tissue through homing, we carried out cell lineage tracing through living dye labeling. Numerous AnSCs were detected in the healing tissue on both day 7 and day 14 after cell injection, but almost of all AnSCs were found in the dermal layer. On the day 14, number of the AnSCs was substantially reduced (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

AnSCs lineage tracing in the healing tissue on day 7 and day 14 after cell injection. Note that numerous dye-labeled AnSCs were detected in the dermal layer of healing tissue on day 7, although significantly reduced on day 14. AnSCs: antler stem cells.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reported to treat radiation-induced cutaneous wounds in rats using AnSCs through transplantation. We found that compared to the other types of currently available MSCs (such as rB-MSCs and hU-MSCs), AnSC treatment had significantly delayed wound occurrence, shorter recovery time, faster healing rate, and better healing quality (Table 3). We also found that AnSC treatment to radiation-induced cutaneous wounds had smaller scars (almost negligible), and regenerated cutaneous appendages including hair follicles and sebaceous glands, indicating function of the healed skin tissue has essentially restored. We believe that these findings may have opened a new avenue of using stem cells to treat radiation-induced wounds with a better choice of cell source.

Therapeutic management of severe radiation burns for cancer therapy remains a challenging issue. Conventional surgical treatment (excision and skin autograft or rotation flap) often fails to prevent unpredictable and uncontrollable extension of the radiation necrotic process31. The novel therapy using MSCs is considered to be a better choice to deal with radiotherapy complications32. The fact that MSCs have immunomodulation properties and inhibitory function of immune cells has been extensively studied33. Recent studies demonstrate that MSCs can suppress mixed lymphocyte reactions involving autologous or allogeneic T cells or dendritic cells34. It is known that the capability to modulate immune responses relies on both paracrine effects through the release of soluble factors and cell-contact-dependent mechanisms35. The notion of paracrine pathway is supported by our previous work, as conditioned medium of AnSCs exerted a similar effect on wound healing29.

We wondered whether a cell-contact part, in addition to paracrine, also plays a role in immunomodulation through homing of the transplanted AnSCs in the present study. Our results demonstrated that large number of AnSCs were lodged in the dermis of healing skin. Given that only a very small portion of systematically injected MSCs that can normally lodge in the target tissue36, our preliminary finding, i.e., considerable number of injected AnSCs lodged in the healing tissue, may be novel and provide another explanation why AnSCs had marginal advantage over the other types of MSCs used in wound healing of this study. Although the number of lodged AnSCs was significantly reduced from day 7 to day 14 after cell transplantation and majority of the homing AnSCs did not persist in the target tissue, likely via apoptotic pathway37. Substances released by the dying cells may also play an important role in stimulating wound healing.

Our present study demonstrated that MSCs enhanced both wound healing rate and quality. Walter et al. used B-MSCs on an in vitro skin wound model and observed that an accelerated healing of the wound by promoting migration of dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes38. Liu et al. reported that transplantation of hU-MSCs could effectively improve wound healing quality and rate in a burn-induced injury rat model39. Nauta et al. used adipose-derived MSCs on mouse excisional wound healing model and showed that it accelerated wound healing through promoting angiogenesis40. In the present study, we used AnSCs to treat radiation-induced cutaneous injury showed a much better outcome than both hU-MSCs and rB-MSCs including regeneration of more cutaneous appendages. It may be conceivable that AnSCs are more potent in inducing cutaneous wound healing, as these cells can in situ stimulate a 10-cm-diameter wound on top of a deer pedicle stump to heal within 10 days41,42. Raveling the mechanism underlying the marginal advantages of the AnSCs over the currently popular types of MSCs may help devise a better strategy for treating cutaneous wounds in clinics.

It is well accepted that MSC treatment can effectively increase wound closure rates, promote angiogenesis, decrease wound inflammation, regulate extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling events, and enhance regeneration of proper skin appendages43. All these functions of MSCs must be underpinned by molecular mechanisms. Resolution of inflammation is essential to quality wound healing, and chronic inflammation can lead to poor healing outcomes44. Sr-90 radiation-induced rat wounds treated with AnSCs demonstrated a significantly lower level of IL-1rap. IL-1rap is a cytokine, which is produced by lymphocytes, monocytes, or other non-mononuclear cells. It has an important regulatory role in cell–cell interactions, immune regulation, hematopoiesis, and inflammatory processes45. Decrease in IL-1rap level in the AnSC group suggests a mild inflammation reaction during the course of wound healing.

Previous studies demonstrated that application of VEGF, FGF1, or HGF can accelerate wound healing by promoting dermal cell dedifferentiation, proliferation, angiogenesis, and migration of epidermal cells. Importantly, dedifferentiation was closely related to regeneration46,47. In this study, levels of VEGF, FGF1, and HGF were significantly increased in the healing tissue of AnSC group, which could have played major roles in the induction of regenerative wound healing in the AnSC group. TGF-β1 has been widely reported to play an essential role in wound healing and scar formation through mediating fibroblast proliferation, collagen production, and myofibroblast differentiation in wound healing process48. Moreover, high collagen content in wound is an important indicator of scar formation49. In our study, we found that Col1A2 and TGF-β1 were significantly decreased in the healing tissue of AnSC-treated rats, thus indicating the less scar formation.

Active ECM remodeling is an important indicator of scarless wound healing in fetal tissue. ECM remodeling requires the coordinated regulation of MMPs and their inhibitors, the TIMPs50. Scarred wound healing has been found to be correlated with low MMP activity and high TIMP activity. In the present study, we found that the level of MMP1 was significantly increased, whereas TIMP1 decreased in the healing tissue of the AnSCs group. Therefore, remodeling of the ECM structure in the healing tissue must have been promoted in the AnSCs group, thus constituting a microenvironment that is permissive for regenerative wound healing to take place.

In summary, our results clearly demonstrated that treatment of radiation-induced wounds in rats with AnSCs delayed the onset of the injury, reduced the recovery time, and increased the healing rate and quality. Results of AnSC lineage tracing showed that substantial numbers of AnSCs lodged in the dermal layer of healing skin, suggesting that the effects of AnSCs on radiation-induced wound healing were at least partially achieved through direct participation to the healing tissue. Expression profiling of wound healing-related genes further demonstrated that wound healing in the AnSC group was more like a fetal one, i.e., scarless. Overall, our study indicates that AnSCs may serve as a novel candidate for cancer patients suffering from cutaneous injury after radiotherapy.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Table_S1 for Transplanted Antler Stem Cells Stimulated Regenerative Healing of Radiation-induced Cutaneous Wounds in Rats by Xiaoli Rong, Guokun Zhang, Yanyan Yang, Chenmao Gao, Wenhui Chu, Hongmei Sun, Yimin Wang and Chunyi Li in Cell Transplantation

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all staffs in the Institute of Antler Science and Product Technology, Changchun Sci-Tech University for their help technically and moral support while we carried out this study.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Administration Committee of Experimental Animals Jilin University (Approval No. XYSK2017-0043).

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All the experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care guidelines of Jilin University, China and approved by the Administration Committee of Experimental Animal Jilin University.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests or any potential conflict of interest in any of the techniques or instruments mentioned in this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA16010105), Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province of China (No. 20170101003JC), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 315007921006697).

ORCID iD: Chunyi Li  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7275-4440

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7275-4440

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(10):738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gourmelon P, Benderitter M, Bertho JM, Huet C, Gorin NC, De Revel P. European consensus on the medical management of acute radiation syndrome and analysis of the radiation accidents in Belgium and Senegal. Health Phys. 2010;98(6):825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashcroft GS, Greenwell-Wild T, Horan MA, Wahl SM, Ferguson MW. Topical estrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing in aged humans associated with an altered inflammatory response. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(4):1137–1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cha J, Falanga V. Stem cells in cutaneous wound healing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(1):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hocking AM. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for cutaneous wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2012;1(4):166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Togel F, Weiss K, Yang Y, Hu Z, Zhang P, Westenfelder C. Vasculotropic, paracrine actions of infused mesenchymal stem cells are important to the recovery from acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(5):F1626–F1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Francois S, Eder V, Belmokhtar K, Machet MC, Douay L, Gorin NC, Benderitter M, Chapel A. Synergistic effect of human bone morphogenic protein-2 and mesenchymal stromal cells on chronic wounds through hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha induction. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baskar R, Lee KA, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(3):193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Begg AC, Stewart FA, Vens C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(4):239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moding EJ, Kastan MB, Kirsch DG. Strategies for optimizing the response of cancer and normal tissues to radiation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(7):526–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chi KD, Ehrenpreis ED, Jani AB. Accuracy and reliability of the endoscopic classification of chronic radiation-induced proctopathy using a novel grading method. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(1):42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Francois S, Bensidhoum M, Mouiseddine M, Mazurier C, Allenet B, Semont A, Frick J, Sache A, Bouchet S, Thierry D, Gourmelon P, et al. Local irradiation not only induces homing of human mesenchymal stem cells at exposed sites but promotes their widespread engraftment to multiple organs: a study of their quantitative distribution after irradiation damage. Stem Cells. 2006;24(4):1020–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benderitter M, Caviggioli F, Chapel A, Coppes RP, Guha C, Klinger M, Malard O, Stewart F, Tamarat R, Luijk PV, Limoli CL. Stem cell therapies for the treatment of radiation-induced normal tissue side effects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(2):338–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodriguez-Menocal L, Shareef S, Salgado M, Shabbir A, Van Badiavas E. Role of whole bone marrow, whole bone marrow cultured cells, and mesenchymal stem cells in chronic wound healing. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang MJ, Sun JJ, Qian L, Liu Z, Zhang Z, Cao W, Li W, Xu Y. Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells enhance the expression of neurotrophic factors and protect ataxic mice. Brain Res. 2011;1402:122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu Y, Huang S, Ma K, Fu X, Han W, Sheng Z. Promising new potential for mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly: sweat gland cell-like differentiative capacity. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012;6(8):645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang M, Li Q, Sheng L, Li H, Weng R, Zan T. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells transplantation accelerates tissue expansion by promoting skin regeneration during expansion. Ann Surg. 2011;253(1):202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li C, Suttie J. Morphogenetic aspects of deer antler development. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:1836–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang D, Berg D, Ba H, Sun H, Wang Z, Li C. Deer antler stem cells are a novel type of cells that sustain full regeneration of a mammalian organ-deer antler. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(6):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rolf HJ, Niebert S, Niebert M, Gaus L, Schliephake H, Wiese KG. Intercellular transport of Oct4 in mammalian cells: a basic principle to expand a stem cell niche?. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li C, Yang F, Sheppard A. Adult stem cells and mammalian epimorphic regeneration-insights from studying annual renewal of deer antlers. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2009;4(3):237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li X, Yang Q, Bai J, Xuan Y, Wang Y. Evaluation of eight reference genes for quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis in human T lymphocytes cocultured with mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12(5):7721–7727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li X, Zhang Y, Qi G. Evaluation of isolation methods and culture conditions for rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotechnology. 2013;65(3):323–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li C, Harper A, Puddick J, Wang W, McMahon C. Proteomes and signalling pathways of antler stem cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li C, Suttie JM. Tissue collection methods for antler research. Eur J Morphol. 2003;41(1):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X, Xu Z, Bai J, Yang S, Zhao S, Zhang Y, Chen X, Wang Y. Umbilical cord tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce t lymphocyte apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by expression of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:7495135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li C. Deer antler regeneration: a stem cell-based epimorphic process. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2012;96(1):51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moroz BB, Onizhshenko NA, Lebedev VG, Deshevoi Iu B, Sidorovich GI, Lyrshchikova AV, Rasulov MF, Krasheninnikov ME, Sevast’ianov VI. The influence of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells of bone marrow on process of local radiation injury in rats after local beta-irradiation [in Russian]. Radiats Biol Radioecol. 2009;49(6):688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rong X, Chu W, Zhang H, Wang Y, Qi X, Zhang G, Wang Y, Li C. Antler stem cell-conditioned medium stimulates regenerative wound healing in rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kohl RR, Kolozsvary A, Brown SL, Zhu G, Kim JH. Differential radiation effect in tumor and normal tissue after treatment with ramipril, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Radiat Res. 2007;168(4):440–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lataillade JJ, Doucet C, Bey E, Carsin H, Huet C, Clairand I, Bottollier-Depois JF, Chapel A, Ernou I, Gourven M, Boutin L, et al. New approach to radiation burn treatment by dosimetry-guided surgery combined with autologous mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Regen Med. 2007;2(5):785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Francois S, Mouiseddine M, Mathieu N, Semont A, Monti P, Dudoignon N, Sache A, Boutarfa A, Thierry D, Gourmelon P, Chapel A. Human mesenchymal stem cells favour healing of the cutaneous radiation syndrome in a xenogenic transplant model. Ann Hematol. 2007;86(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, Grisanti S, Gianni AM. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99(10):3838–3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tse WT, Pendleton JD, Beyer WM, Egalka MC, Guinan EC. Suppression of allogeneic T-cell proliferation by human marrow stromal cells: implications in transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(3):389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Doorn J, Moll G, Le Blanc K, van Blitterswijk C, de Boer J. Therapeutic applications of mesenchymal stromal cells: paracrine effects and potential improvements. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18(2):101–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Becker A, Riet IV. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: how to improve the efficacy of cell therapy?. World J Stem Cells. 2016;8(3):73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kollek M, Voigt G, Molnar C, Murad F, Bertele D, Krombholz CF, Bohler S, Labi V, Schiller S, Kunze M, Geley S, et al. Transient apoptosis inhibition in donor stem cells improves hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Exp Med. 2017;214(10):2967–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walter MNM, Wright KT, Fuller HR, MacNeil S, Johnson WEB. Mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium accelerates skin wound healing: an in vitro study of fibroblast and keratinocyte scratch assays. Experimental Cell Research. 2010;316(7):1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu L, Yu Y, Hou Y, Chai J, Duan H, Chu W, Zhang H, Hu Q, Du J. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells transplantation promotes cutaneous wound healing of severe burned rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nauta A, Seidel C, Deveza L, Montoro D, Grova M, Ko SH, Hyun J, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT, Yang F. Adipose-derived stromal cells overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor accelerate mouse excisional wound healing. Mol Ther. 2013;21(2):445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li C, Suttie JM, Clark DE. Morphological observation of antler regeneration in red deer (Cervus elaphus). J Morphol. 2004;262(3):731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li C, Suttie JM, Clark DE. Histological examination of antler regeneration in red deer (Cervus elaphus). Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2005;282(2):163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee DE, Ayoub N, Agrawal Dk. Mesenchymal stem cells and cutaneous wound healing: novel methods to increase cell delivery and therapeutic efficacy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;9(7):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu J, Wu W, Zhang L, Dorset-Martin W, Morris MW, Mitchell ME, Liechty KW. The role of microRNA-146a in the pathogenesis of the diabetic wound-healing impairment: correction with mesenchymal stem cell treatment. Diabetes. 2012;61(11):2906–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bassoy EY, Towne JE, Gabay C. Regulation and function of interleukin-36 cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2018;281(1):169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li JF, Duan HF, Wu CT, Zhang DJ, Deng Y, Yin HL, Han B, Gong HC, Wang HW, Wang YL. HGF accelerates wound healing by promoting the dedifferentiation of epidermal cells through beta1-integrin/ILK pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:470418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pikula M, Langa P, Kosikowska P, Trzonkowski P. Stem cells and growth factors in wound healing. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online). 2015;69:874–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang R, Ghahary A, Shen Q, Scott PG, Roy K, Tredget EE. Hypertrophic scar tissues and fibroblasts produce more transforming growth factor-beta1 mRNA and protein than normal skin and cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(2):128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Timar-Banu O, Beauregard H, Tousignant J, Lassonde M, Harris P, Viau G, Vachon L, Levy E, Abribat T. Development of noninvasive and quantitative methodologies for the assessment of chronic ulcers and scars in humans. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(2):123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kähäri VM, Saarialho-Kere U. Matrix metalloproteinases in skin. Exp Dermatol. 1997;6(5):199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, Table_S1 for Transplanted Antler Stem Cells Stimulated Regenerative Healing of Radiation-induced Cutaneous Wounds in Rats by Xiaoli Rong, Guokun Zhang, Yanyan Yang, Chenmao Gao, Wenhui Chu, Hongmei Sun, Yimin Wang and Chunyi Li in Cell Transplantation