Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) therapy is a potential therapy for treating acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which was widely studied in the last decade. The purpose of our meta-analysis was to investigate the efficacy of MSCs for simulated infection-induced ALI/ARDS in animal trials. PubMed and EMBASE were searched to screen relevant preclinical trials with a prespecified search strategy. 57 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in our study. Our meta-analysis showed that MSCs can reduce the lung injury score of ALI caused by lipopolysaccharide or bacteria (standardized mean difference (SMD) = −2.97, 95% CI [−3.64 to −2.30], P < 0.00001) and improve the animals’ survival (odds ratio = 3.64, 95% CI [2.55 to 5.19], P < 0.00001). Our study discovered that MSCs can reduce the wet weight to dry weight ratio of the lung (SMD = −2.58, 95% CI [−3.24 to −1.91], P < 0.00001). The proportion of the alveolar sac in the MSC group was higher than that in the control group (SMD = 1.68, 95% CI [1.22 to 2.13], P < 0.00001). Moreover, our study detected that MSCs can downregulate the levels of proinflammatory factors such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α in the lung and it can upregulate the level of anti-inflammatory factor IL-10. MSCs were also found to reduce the level of neutrophils and total protein in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, decrease myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the lung, and improve lung compliance. MSC therapy may be a promising treatment for ALI/ARDS since it may mitigate the severity of lung injury, modulate the immune balance, and ameliorate the permeability of lung vessels in ALI/ARDS, thus facilitating lung regeneration and repair.

Keywords: stem cell, mesenchymal stromal cell, acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cell therapy

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a heterogeneous disease caused by a variety of intrapulmonary/extrapulmonary factors1. The main pathophysiological characteristics of ARDS are diffused inflammatory lung injury, increased permeability of the pulmonary blood and gas barrier, lung edema, leukocytes infiltration, and gas exchange and oxygenation impairments in the acute phase, which all together cause refractory hypoxia. ARDS has high morbidity and mortality with regard to critically ill patients. Though the understanding of ARDS and its diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have advanced significantly, the mortality rate of severe ARDS patients is still around 40%2. Acute lung injury (ALI)/ARDS induced by infection can be well simulated in other common mammals such as rats, mice, or pigs by cecal ligation and perforation or tracheal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) instillation. Thus, the systematic review of preclinical studies may help us to comprehend better the features and treatment of ALI/ARDS in humans.

To date, there is yet no effective medical remedy for ARDS. Medications such as surfactants, low-dose glucocorticoids, n-acetylcysteine, statins, and β-adrenergic agonists are not supported by evidence-based studies for treating ARDS, because they do not decrease mortality, shorten mechanical ventilation time, or improve the life quality of ARDS patients3. MSCs are of stromal origin and have the capability of self-renewal and differentiation into cells of mesodermal origin, including chondrocytes, osteocytes, and adipocytes4,5. In experimental ALI/ARDS, MSC is lung protective and exerts its therapeutic benefit mainly through a paracrine activity. These data suggest MSC as a promising therapy to reduce the severity of ALI/ARDS. To date, MSCs are available from several tissues, such as umbilical cord blood, placenta, adipose tissue, lung, and bone marrow6,7.

With antibacterial, immunomodulatory, and tissue and organ repair and regeneration characteristics, MSCs are expected to be new hope for the treatment of ARDS8. Since the efficacy investigation of MSC for ARDS in humans is still in the preliminary phase, a summary of evidence from animal experiments is very necessary. We hope to sum up the animal MSC therapeutic studies for treating ALI/ARDS through meta-analysis. By systematical and quantitative analysis, we may be able to confirm the efficacy of MSCs for ALI/ARDS on large sample size, sort out the characteristics of the current research, and provide some reference for future research.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

PubMed and EMBASE (up to October 18, 2019) were searched to screen relevant preclinical trials with a prespecified search strategy, which was revised appropriately through databases. Search terms included “acute respiratory distress syndrome,” “acute lung injury,” “mesenchymal stem cell,” and “mesenchymal stromal cell.” The search strategy is as follows: (((((Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome[Title/Abstract]) OR ARDS[Title/Abstract]) OR acute lung injury[Title/Abstract]) OR ALI[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((((mesenchymal stem cell[Title/Abstract]) OR mesenchymal stem cells[Title/Abstract]) OR mesenchymal stromal cell[Title/Abstract]) OR mesenchymal stromal cells[Title/Abstract]) OR msc[Title/Abstract]) OR MSC’s[Title/Abstract]))).

Study Selection

Two authors (WFY and ZLX) searched and assessed the relevant literature independently and checked the title and abstract of every retrieved article to decide which required further evaluation. Full articles were retrieved if the information given in the titles and abstracts indicated the inclusion of a prospective design for the purpose of investigating the therapeutic effects of MSCs for ALI/ARDS in animal models. When there were disagreements, the two authors discussed them thoroughly with the third author (FB) to reach a consensus.

The inclusion criteria: (1) any controlled preclinical studies investigated MSCs for ALI/ARDS, which should include data for at least one of the predefined outcomes that can be extracted for meta-analysis; (2) any animal models of LPS/bacteria-induced ALI/ARDS, of any species, age, or gender; (3) MSCs administered with any approach or any dosage—of note, wild-type MSCs were preferred to be included in our meta-analysis. MSCs were defined using the minimal criteria set out in the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) consensus statement9,10.

The exclusion criteria: (1) noninterventional studies were excluded; (2) studies that only investigated extracellular vesicles or exosomes derived from MSCs, without an MSC control group, were excluded; (3) studies that only investigated an MSCs-conditioned medium, without an MSC control group, were excluded.

Qualitative Assessment and Risk of Bias

Two review authors (WFY and ZLX) independently extracted data according to a prespecified data extraction form specifically designed for this review. Study characteristics were extracted if they were related to the construct and external validity. Risk of bias was evaluated by two reviewers (WFY and ZLX), for each included study, using SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias tool (an adaptation of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool) for animal studies11. For construct validity, we included the following: age, sex, strain, and animal species; type of ALI/ARDS model; timing, dose, and mode of MSC administration; and the use of any cointerventions.

As most of the data in the literature were presented as figures and not in numerical form, we used a validated graphical digitizer (WebPlot-Digitizer, version 4.2), an open-source program, to extract data from figures. The manual of WebPlot-Digitizer can be found on its website (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/).

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods

Data analyses of this review were performed by Review Manager 5.3. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the I 2 with 95% CIs, and data were visualized using forest plots. A funnel plot was applied to check for publication bias, and I 2 was applied to estimate the total variation attributed to heterogeneity among studies. Values of I 2 less than 25% were considered as having low heterogeneity, and a fixed-effect model for meta-analysis was used. Values of I2 bigger than 25% represented moderate or high levels of heterogeneity existing between studies, and a random-effects model was applied. For dichotomous variables, odds ratio (OR) was used for statistical calculation, whereas for continuous variables, mean and standardized mean difference (SMD) were used. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Our primary outcomes are lung injury score and survival. The ultimate goal of investigating a potential therapeutic for ARDS is to reduce mortality, and hence the mortality rate is one of the primary outcomes. Because the importance of mortality in preclinical studies was not comparable to that of human trials, and therefore the lung injury score, a pathological scoring scale that directly reflects the severity of lung injury is an appropriate equivalent. Secondary outcomes are inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α; anti-inflammatory factor IL-10; lung wet weight to dry weight ratio (W/D ratio); lung alveolar sac percentage; total protein in BALF; neutrophils in BALF; MPO activity in the lung; partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2); and lung compliance. These variables are important pathophysiological parameters in ARDS and participate in the pathogenesis of ARDS, all of which are essential and meaningful to be included in our study.

Results

Study Selection Process

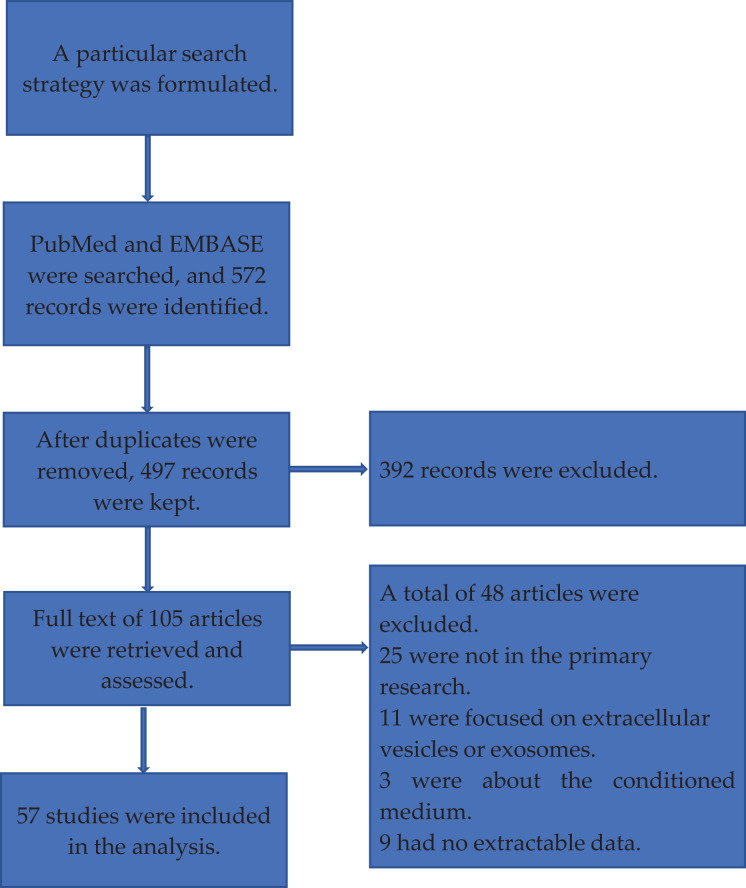

The flow diagram in Fig. 1 shows the whole screening and selection process. A total of 572 articles were found by means of electronic database searches. After deleting the duplicates, 497 articles were retained to read the title and abstract. The full text of 105 articles was then retrieved for further review after scanning. Finally, 57 of the 105 articles met the inclusion criteria12–68.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for selecting relevant preclinical trials.

The Characteristics of the Included Literatures

The detailed characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| References | Animal, gender | Injury model | MSCs source | MSCs dose, method of administration | Time of assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monsel et al.12 | Male C57BL/6 mice | Escherichia coli (2 or 3 × 106 CFUs), IT | Human BM MSCs | 8 × 105 cells, IV | 18, 24, or 72 h after modeling |

| Cai et al.13 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (100 μg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 3, 7, or 14 days after modeling |

| Chailakhyan et al.14 | Male Wistar rats | LPS (25 mg/kg), IP | Rat BM MSCs | 2 × 106 cells, IV | 6 h after modeling |

| Chen CH et al.15 | Adult male SD rats | LPS (1.5 mg/kg), IP | Rat AD MSCs | 1.2 × 106 cells, IV | 48 and 72 h after ARDS induction |

| Chen J et al.16 | C57BL/6 male mice | LPS (10 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 6, 24, 72, or 168 h after MSC injection |

| Chen X et al.17 | Male ICR mice | Vibrio vulnificus, IP | Mouse BM MSCs | 4 × 105 cells, IV | 6, 12, 24, or 48 h after modeling |

| Chen X et al.18 | Wistar rats | LPS (24 mg) nebulization | Rat BM MSCs | 0.5 × 106 cells, IV | 1, 3, and 7 days after modeling |

| Masterson et al.19 | Adult male SD rats | E. coli (2 × 109 CFUs), IT | Human BM MSCs | 1 × 107 cells/kg | 48 h after MCS injection |

| Kim et al.20 | Male ICR mice | E. coli at 107 CFUs, IT | Human UC MSCs | 1 × 105 cells, IT | 1, 3, and 7 days postinjury |

| Jerkic et al.21 | Adult male SD rats | E. coli (2 to 3 × 109 CFUs), IT | Human UC MSCs | 1 × 107 cells/kg, IV | 48 h after injection |

| Fang et al.22 | C57BL/6 male mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IT | Human MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 48 or 72 h after modeling |

| Gao et al.23 | Adult SD rats | LPS (6 mg/kg), IP | Human AD MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 24, 48, and 72 h after MSC injection |

| Curley et al.24 | Male SD rats | E. coli (1.5 to 2 × 109 CFU/kg), IT | Human UC MSCs | 1 × 107 cells, IV | 24 or 48 h after modeling |

| Han et al.25 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS, IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 24 or 72 after MSC injection |

| Hao et al.26 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (4 mg/kg), IT | Human BM MSCs | 7.5 × 105 cells, IT | 48 h after modeling |

| He et al.27 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (100 μg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 24 or 72 h after MSC treatment |

| Huang R et al.28 | C57BL/6 mice | LPS (4 mg/kg), IT | Human AD MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 24 h or 48 h after modeling |

| Huang ZW et al.29 | Male SD rats | LPS (10 mg/kg), IP | Human UC MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 6, 24, 48 h, or 15 days after modeling |

| Hu et al.30 | C57BL/6 mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IP | Human AD MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 6, 24, 48 h after modeling |

| Devaney et al.31 | Adult male SD rats | E. coli (2 × 109 cfu), IT | human MSCs | 1 × 107 cells/kg, IV | 48 h after MSC treatment |

| Silva et al.32 | C57BL/6 mice | LPS (2 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 1 × 105 cells, IV | 24 h after modeling |

| Ionescu et al.33 | C57BL/6 mice | LPS (4 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 2.5 × 105 cells, IT | 48 h after modeling |

| Pedrazza et al.34 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (200 μg), IT | Mice AD MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, retro-orbital injection | 12 h after modeling |

| Liang et al.35 | Wistar rats | LPS (8 mg/kg), IV | Rat BM MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 6, 24 h, 1, or 3 weeks postinjection |

| Li D et al.36 | Female SD rats | LPS (10 mg/kg), IP | Human UC MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 1, 7, and 14 days postinjection of LPS |

| Li JW et al.37 | Male SD rats | LPS (10 mg/kg), IV | Rat BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 2, 24, and 72 h after MSC treatment |

| Li J et al.38 | Male SD rats | LPS (10 mg/kg), IP | Human UC MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 48 h after MSC treatment |

| Lang et al.39 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (100 μg), IT | Mouse BM MSCs | 5 × 104 cells, IT. | 3, 7, and 14 days after modeling |

| Liu et al.40 | Male BALB/c mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IT | Human UC MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 30 min, 1, 3, and 7 days postinjection |

| Liu et al.41 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (up to 5 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 1, 3 and 7 days post-injection |

| Soliman et al.42 | Male albino rats | LPS (40 μg), intranasal | Rat BM MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IP | 48 h after modeling |

| Khatri et al.43 | Duroc crossbred pigs | LPS (1 mg/kg), IT | Porcine BM MSCs | 2 × 106 cells/kg, IT | 48 h after MSC administration |

| Maron-Gutierrez et al.44 | C57BL/6 mice | LPS (2 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 1 × 105 cells, IV | 1, 2, and 7 days after modeling |

| Dezfouli et al.45 | Male rabbits | LPS (400 μg/kg), IT | Rabbits BM MSCs | 1 × 1010 cells, IT | 12, 24, 72, and 168 h post-transplant |

| Gupta et al.46 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 7.5 × 105 cells, IT | 24 and 72 h after modeling |

| Gupta et al.47 | Male C57BL/6 mice | E. coli (1 × 106 CFUs), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 12 to 48 h after MSC injection |

| Gupta et al.48 | Male C57BL/6 mice | E. coli (1 × 106 CFUs), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 24, 72 h, and 1 week after modeling |

| Qin et al.49 | Male SD rats | LPS (7 mg/kg), IT | Rat BM MSCs | 2 × 106 cells, intrapleural | 1, 3, and 7 days after modeling |

| Ren et al.50 | Male ICR mice | LPS (2 mg/kg), IT | Human UC/BM MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 72 h post-MSC transplantation |

| Shalaby et al.51 | Male BALB/c mice | E. coli (107 CFUs), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 48 h after modeling |

| Mei et al.52 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (800 μg), IT | Mice MSCs | 2.5 to 3 × 105 cells, IV | 3 days after MSC treatment |

| Song et al.53 | Adult BALB/c mice | LPS (10 μg/g), intranasal | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IV | 0, 3, 7, and 14 post-transplantation |

| Sun et al.54 | Male BALB/c mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IT | Human UC MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IT | 1, 3, and 7 days after modeling |

| Asmussen et al.55 | Adult sheep | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, IT | Human BM MSCs | 5 to 10 × 106 cells/kg, IV | 24 h after modeling |

| Danchuk et al.56 | Female BALB/C mice | LPS (1 mg/kg), IT | Human BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 24 or 48 h after LPS instillation |

| Tai et al.57 | Kunming mice | LPS, intranasal | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 106 cells, IV | 24 h after MSC administration |

| Tang et al.58 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (4 mg/kg), IT | Human BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 48 h after MSC injection |

| Wang et al.59 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (5 μg/g), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after modeling |

| Xu J et al.60 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (12 mg/day) nebulized for 7 days | Mice BM MSCs | 1 × 105 cells, IV | 3, 7, and 14 days after modeling. |

| Xu M et al.61 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (2.5 mg/kg), IT | Human P MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 24 h after MSC administration |

| Xu XP et al.62 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS, IT | Human BM MSCs | 1 × 105 cells, IV | 24 and 72 h after MSC injection |

| Yang JX et al.63 | SD rats | LPS (10 mg/kg), IP | Rat BM MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 72 h after modeling |

| Yang Y et al.64 | Male wild-type SD rats | LPS (2 mg/kg), IT | Rat BM MSCs | 5 × 106 cells, IV | 1, 6, and 24 h after MSC infusion. |

| Zhang S et al.65 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (100 μg), IT | Human A MSCs | 1 × 106 cells, IV | 3, 7, or 14 days post-treatment |

| Zhang X et al.66 | Male C57BL/6 mice | LPS (5 mg/kg), IT | Mice BM MSCs | 5 × 105 cells, IT | 7 or 14 days after MSC injection |

| Zhang Z et al.67 | Female C57BL/6 mice | LPS (10 mg/kg), IT | Human UC MSCs | 2 × 105 cells, IV | After 48 h or 7 days |

| Zhu et al.68 | Female BALB/C mice | LPS (5 mg/kg) , IT | Human UC MSCs | 0.5 × 106 cells, IV | 120 h after LPS exposure |

ALI: acute lung injury; AD: adipose-derived; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; BM: bone marrow; CFU: colony-forming unit; ICR: Institute of Cancer Research; IT: intratracheal; IV: intravenous; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; SD: Sprague–Dawley; UC: umbilical cord.

Risk of Bias and Study Validity

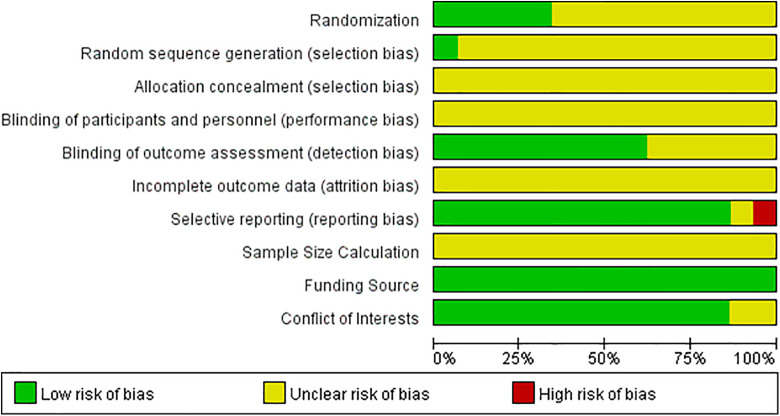

Risk of bias was evaluated for the primary outcome: lung injury score in 29 included studies using 10 domains. The SYRCLE’S Risk of Bias contains 10 entries related to selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias was adapted to include sample size calculation, source of funding, and conflict of interests. The results were presented in Fig. 2. Overall, none of the included studies met the criteria for low risk of bias across all 10 domains. The detailed summary of biases of each study can be found in the Supplementary files. The funnel plots and subgroup meta-analyses of primary outcomes and secondary outcomes can also be found in the Supplementary files.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Primary Outcomes: Lung Injury Score and Survival

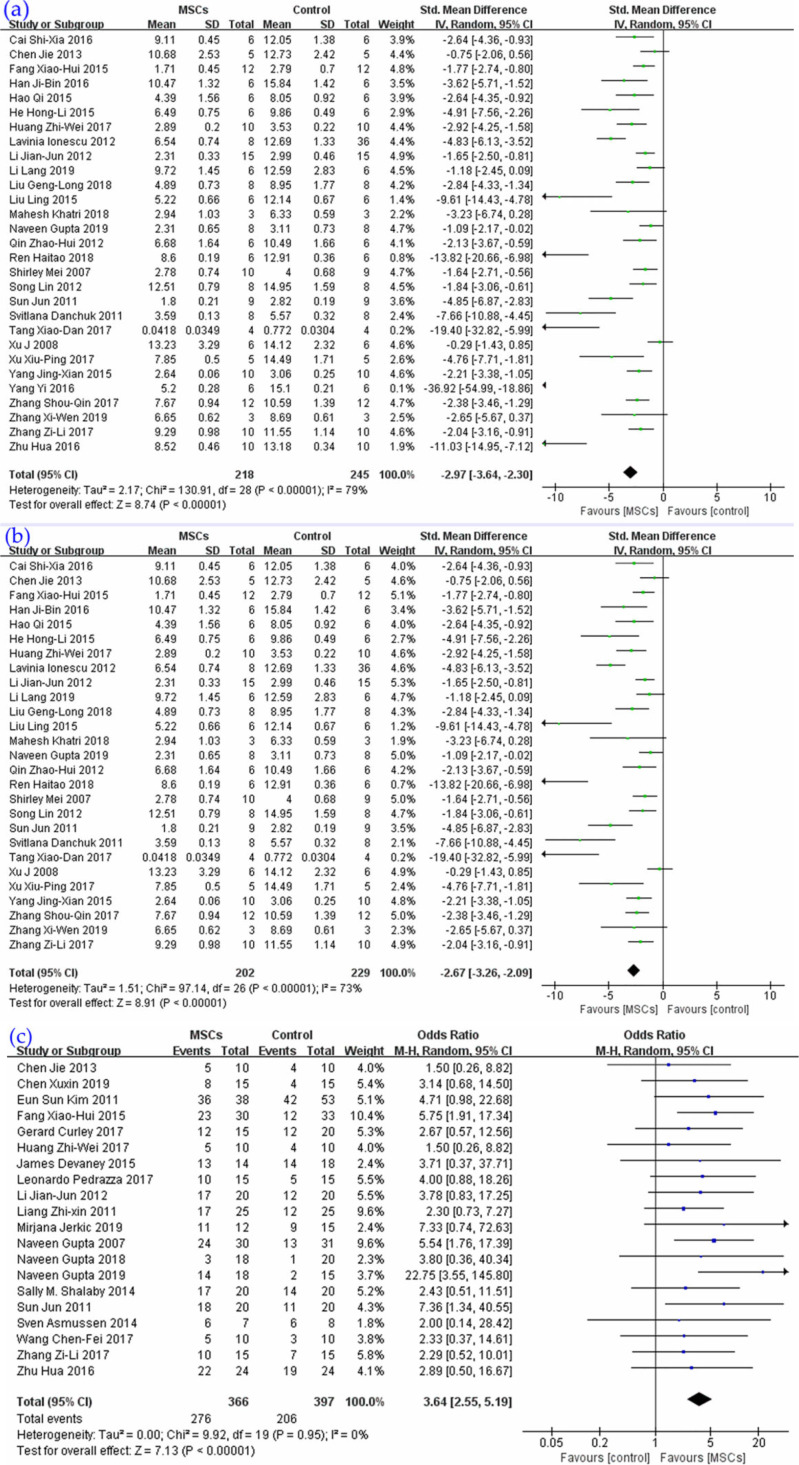

Lung injury score

Twenty-nine of the included studies reported a lung injury score (Fig. 3a). Based on these, the pooled results indicated that MSCs could reduce the lung injury score, SMD = −2.97, 95% CI (−3.64 to −2.30), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 79%. The result of lung injury score subgroup meta-analysis reported a similar result (Fig. 3b), SMD = 2.67, 95% CI (−3.26 to −2.09), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 73%.

Figure 3.

Main outcomes meta-analyses of MSCs comparing with ALI control group: (a) lung injury score; (b) lung injury score subgroup; and (c) survival. The size of each square represents the proportion of information given by each trial. Crossing with the vertical line suggests no difference between the two groups. ALI: acute lung injury; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

Survival

Twenty studies reported a survival rate (Fig. 3c), the synthesis of results for which indicated that MSCs could improve the short-term survival of lung injury animals, odds ratio (OR) = 3.64, 95% CI (2.55 to 5.19), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0%.

Secondary Outcomes

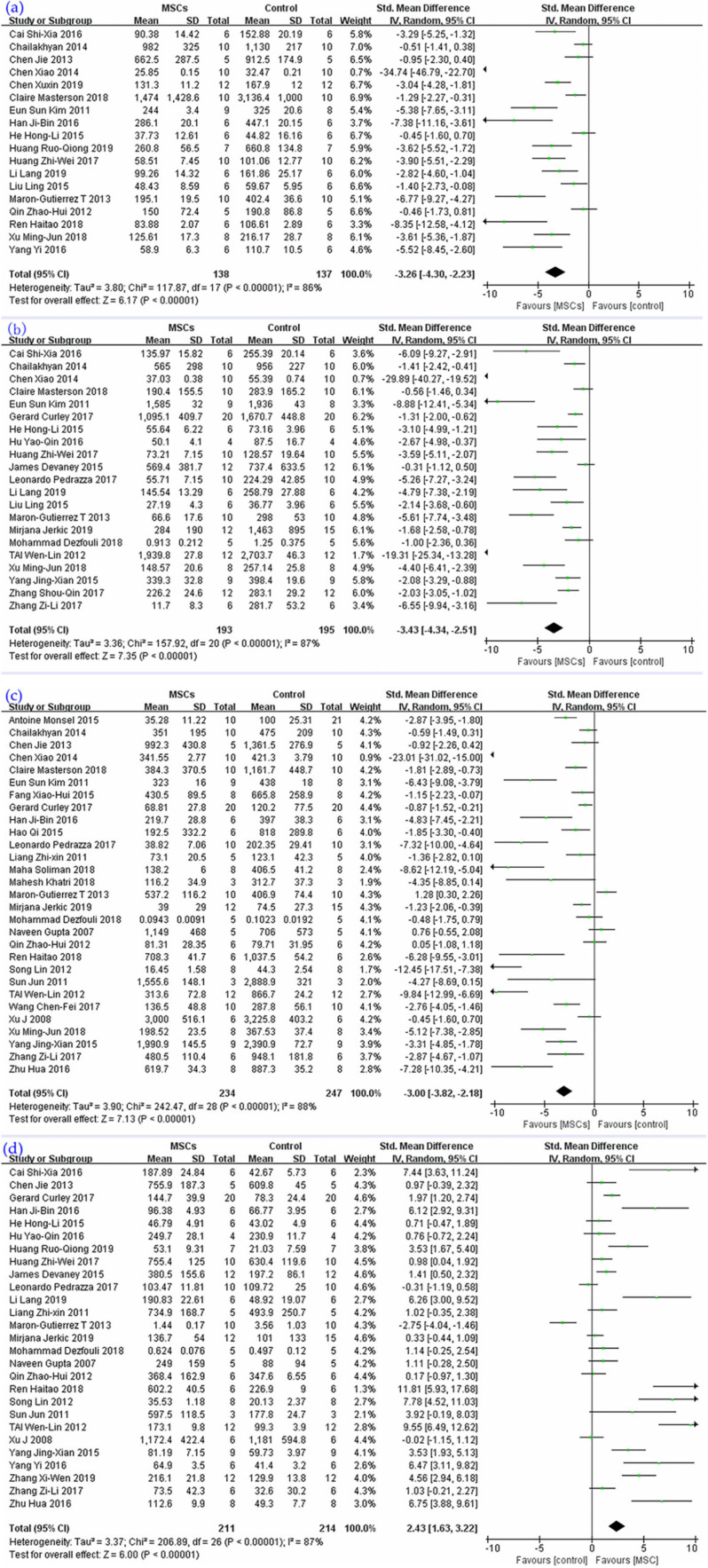

Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors

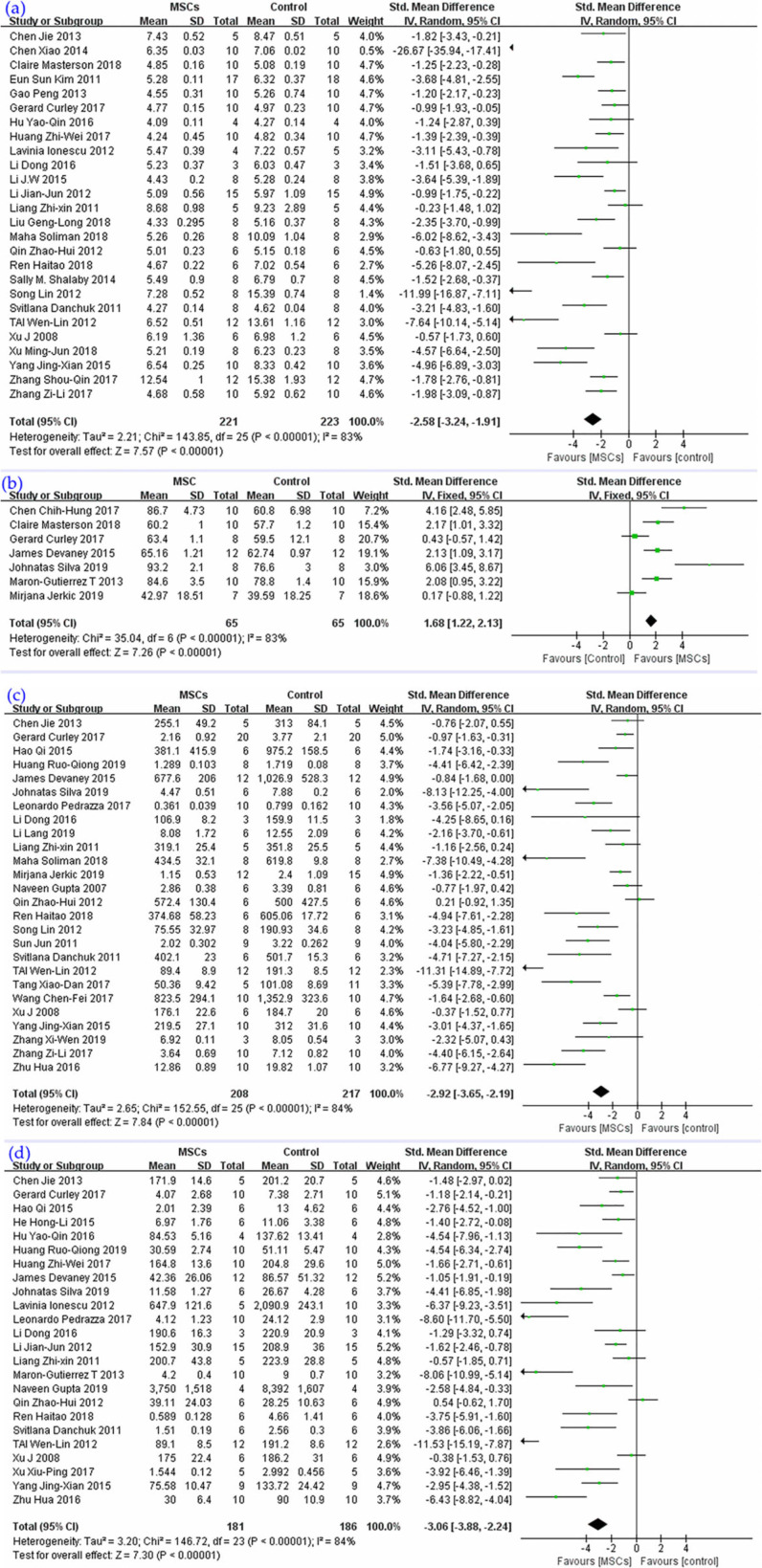

A large number of studies investigated the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-10 in lung tissue or BALF of lung injury animal models. The results of the meta-analysis are as follows: the synthesis of 18 studies (Fig. 4a) suggested that the level of IL-1 β could be reduced by MSC therapy, SMD = −3.26, 95% CI (−4.30 to −2.23), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 86%. For 21 studies (Fig. 4b), the synthesis of results revealed that the level of IL-6 could be reduced by MSC therapy, SMD = −3.43, 95% CI (−4.34 to −2.51), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 87%. Twenty-nine studies’ (Fig. 4c) pooled result pointed out that MSCs could reduce the level of TNF-α, SMD = −3.00, 95% CI (−3.82 to −2.18), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 88%. Data concerning IL-10 was extracted from 27 studies (Fig. 4d), the pooled results of which indicated that the level of IL-10 could be increased by MSC therapy, SMD = 2.43, 95% CI (1.63, 3.22), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 87%.

Figure 4.

The meta-analyses of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors compare MSCs with ALI control group: (a) IL-1β, (b) IL-6, (c) TNF-α, and (d) IL-10. The size of each square represents the proportion of information given by each trial. Crossing with the vertical line suggests no difference between the two groups. ALI: acute lung injury; IL: interleukin; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

Wet to dry weight ratio of lung

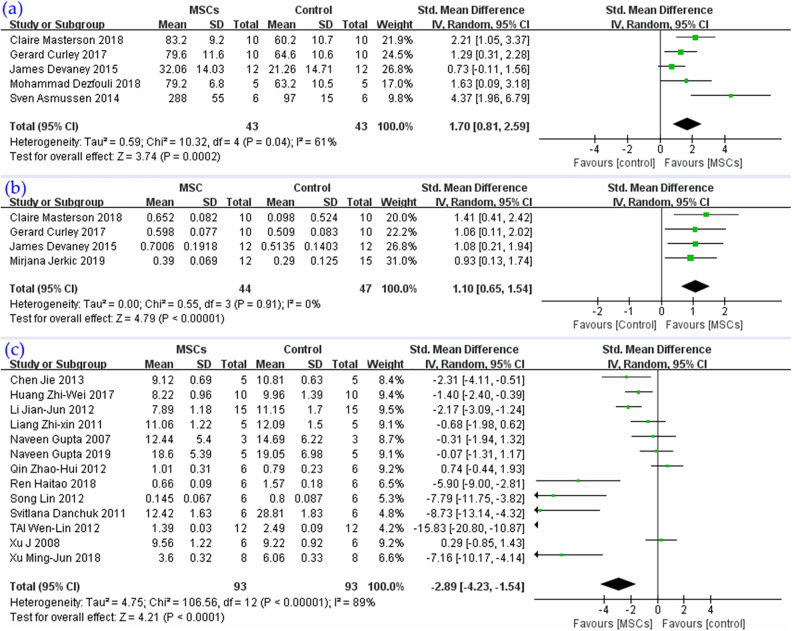

Twenty-six studies were enrolled (Fig. 5a) in the synthesis; their result indicated that MSC treatment could reduce the W/D ratio of the lung, SMD = −2.58, 95% CI (−3.24 to −1.91), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 83%.

Figure 5.

The meta-analyses of (a) W/D ratio, (b) alveolar sac percentage, (c) total protein, and (d) neutrophils in BALF compare MSCs with the ALI control group. The size of each square represents the proportion of information given by each trial. Crossing with the vertical line suggests no difference between the two groups. ALI: acute lung injury; BALF: bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; W/D: wet to dry ratio.

Alveolar sac percentage

The percentage of the alveolar sac was investigated in seven studies (Fig. 5b). The synthesis of their results revealed that MSCs could improve the proportion of air alveoli, SMD = 1.68, 95% CI (1.22 to 2.13), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 83%.

Total protein level in BALF

Total protein level in BALF was the subject of 26 studies (Fig. 5c), and their pooled result demonstrated that MSCs could reduce the protein level in BALF, SMD = −2.92, 95% CI (−3.65 to −2.19), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 84%.

Neutrophil level in BALF

The pooled results of 24 studies (Fig. 5d) highlighted that MSC therapy could reduce the infiltration of neutrophils in alveoli, SMD = −3.06, 95% CI (−3.88 to −2.24), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 84%.

Physiological Parameters and Lung Compliance

PaO2

Five studies (Fig. 6a) were included in the synthesis and yielded a result that MSCs could improve oxygenation of the lung injury model, SMD = 1.70, 95% CI (0.81 to 2.59), P = 0.0002, I 2 = 61%.

Figure 6.

The meta-analyses of (a) PaO2, (b) lung compliance, and (c) MPO activity in lung compare MSCs with the ALI control group. The size of each square represents the proportion of information given by each trial. Crossing with the vertical line suggests no difference between the two groups. ALI: acute lung injury; MPO: myeloperoxidase; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen.

Lung compliance

Four studies presented data about lung compliance (Fig. 6b), and their synthesized results revealed that MSCs can improve lung compliance in ALI models, SMD = 1.10, 95% CI (0.65 to 1.54), P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0%.

MPO activity in lung

Thirteen studies reported MPO activity (Fig. 6c); results of the synthesis showed that MSC therapy could reduce MPO activity in lung, SMD = −2.89, 95% CI (−4.23 to −1.54), P < 0.0001, I 2 = 89%.

Discussion

This study presents an updated meta-analysis of Lauralyn McIntyre et al.’s work69 but with an entirely new design and conception. In Lauralyn McIntyre et al.’s study, they only did meta-analysis for mortality rate, far more solid evidence that can manifest MSC’s efficacy on lung injury, such as lung injury score, lung wet to dry weight ratio (W/D ratio), and protein in BALF, were not pooled for meta-analysis. In our study, not only did we include three times plus more studies (57 vs. 17), but we also did far more meta-analyses for different data, such as the lung injury score, W/D ratio, total protein in BALF, and PaO2, all of which are crucial, from different angles, for demonstrating the efficacy of MSC’s for ALI/ARDS. Thus, these data are not derivative but are unique and important. In brief, this is a more comprehensive meta-analysis of preclinical studies to sum up the treatment of ALI/ARDS caused by simulated infectious factors with MSCs. If the evidence of MSCs’ efficacy for treating ARDS in animals is robust and concrete, it will give clinicians more confidence to investigate it in the clinical field.

Our meta-analysis showed that MSCs can reduce the severity of ALI caused by LPS or bacteria and improve the animal models’ survival. Our study discovered that in animal experiments, MSCs can reduce the ratio of wet to dry weight of the lung, and the amount of extravascular lung water intuitively; also, from the perspective of pathophysiology, they can improve oxygenation and lung compliance. Morphologically, after the treatment of MSCs, the proportion of air alveolar sac in the MSC group was higher than that in the control group, and this may be another important factor for improving oxygenation and survival.

Moreover, our study detected that MSCs can reduce the levels of proinflammatory factors, such as IL-1 β, IL-6, and TNF-α, in the lung and can promote the level of the anti-inflammatory factor IL-10, which may alter the balance of inflammation, play a role in immunomodulation, and avoid the aggravation of lung function or the functioning of other important organs. MSCs were also found to reduce the level of neutrophils in BALF, which was important to reducing the pulmonary inflammatory response. In addition, MSCs reduced the activity of MPO, perhaps signifying that MSCs can attenuate oxidative stress and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Additionally, our meta-analysis also revealed that MSCs can reduce the protein content in BALF. With regard to lung compliance, we extracted data from four studies, the meta-analysis of which yielded that MSCs can improve lung compliance of ALI/ARDS animal models, but the included studies are too few to draw a creditable conclusion.

In order to reduce the amount of heterogeneity among the studies, the wild-type MSC group was preferred for comparison with the ALI control group for meta-analysis. However, some studies indicated that the effect of gene-modified or preconditioned MSCs is better than that of the wild type. Diana Islam et al. noted that the impact of MSCs can be either favorable or harmful, depending on the microenvironment at the time of intervention; so, identification of potentially beneficial lung local-microenvironment may be critical to guide MSC therapy in ARDS70. With genetic modification or preconditions, we may guide MSCs and adjust the microenvironment in the lung for better efficacy. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) can function in epithelial cells and restrain the generation of the fibroblast phenotype, which is beneficial in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis71.

One particular study demonstrated that HGF gene modification not only can improve the survival of MSCs but also can ameliorate lung injury induced by IRI72. In another animal trial, KGF gene therapy, which was proved to promote type II lung epithelial cell proliferation and enhance surfactant synthesis, may be a promising strategy for ALI treatment16. Qiao W et al. demonstrated that pretreatment of human MSCs with N-acetylcysteine in mice can improve cell transplantation and the treatment of lung injury73. Jerkic et al. proved that IL-10 overexpression in UC-MSCs can enhance their effects in E. coli-induced pneumosepsis and improve macrophage function21 and may also have potential in treating infection-induced ARDS. Human angiopoietin-1 maintains the normal quiescent phenotype of vascular ECs, protecting vessels against inflammation74. Mei et al. established that angiopoietin-1 transfected MSCs can reduce LPS-induced acute pulmonary inflammation further and improve alveolar inflammation and permeability in mice52. MSCs and prostaglandin E2 combination gene therapy can markedly facilitate MSC homing to areas of inflammation, representing a novel strategy for MSC-based gene therapy in inflammatory diseases25. From the intriguing results of the above animal studies, either the growth and differentiation promotion factor or antioxidative agent or anti-inflammatory gene therapy in combination with MSCs may enhance the therapeutic effects of both for ALI/ARDS. MSCs can be engrafted onto the injured lung after gene modification; in this way, it may promote the concentration of the above agents in the lung as well as lengthen the effective time for lung repair, where MSC treatment may have a better therapeutic effect.

To date, there are three published studies that are focused on the safety of MSCs for treating ARDS75–77. The clinical study of Zheng et al. showed that MSC with a dose of 1 × 106 cells/kg of body weight is safe for the treatment of moderate and severe ARDS75. Nevertheless, because of its small sample size (only 12 patients were included), the power of Zheng’s study was rather limited75. Another phase 1 clinical trial indicated that 1 × 106 to 1 × 107cells/kg MSC therapy was well tolerated in nine patients with moderate to severe ARDS76. Recently, a phase 2a safety randomized controlled trial, which admitted 60 patients revealed that no patient in the MSC group experienced any of the predefined MSC-related hemodynamic or respiratory adverse events, and the 28-day mortality did not differ between the groups77. However, the researchers discovered that concentrations of angiopoietin-2 in plasma were significantly reduced at 6 h in MSC recipients, suggesting a biological effect of the MSC treatment, as angiopoietin-2 is a widely recognized mediator and biomarker of pulmonary and systemic vascular injury77.

The meta-analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes revealed that the heterogeneity among the studies was highly substantial, and the heterogeneity may have originated from multiple aspects. First, some suspicious publication bias was detected in some meta-analysis by running a funnel chart. After excluding the related studies, the subgroup analysis showed that heterogeneity decreased to within the acceptable range. Though the overall effectiveness of MSC decreased slightly, the difference in related comparison still had statistical significance. Second, MSCs were derived from different species, and both human and animal MSCs were included. Additionally, tissue origins, bone marrow, umbilical cord, and adipocyte-derived MSCs were used, respectively, in different studies. Different species or different tissue sources of MSCs may have different therapeutic effects. Thus, the standardization of the species and tissue origin of MSCs in preclinical trials is a matter of great importance. Third, LPS in different studies were manufactured by different factories, which may have created differentiation in virulence; plus, the dose of LPS was also different. The end result is that the severity of lung injury may differ significantly among studies. Finally, criteria for the lung injury score may not be completely consistent among studies; additionally, different brands of ELISA reagents may also be sources of heterogeneity. Indeed, subgroup analyses may help us decipher which tissue-origin, dose, route, and such are more efficacious, for the sake of facilitating future studies. But after the reduction of I 2 less than 75% by subgroup analyses, most of the P values were still less than 0.001, giving us a good reason to believe that the results of these further subgroup analyses won’t make a difference.

Though our study proved that MSCs can reduce the severity of lung injury and animal mortality and potentially regulate the balance of inflammation, our main purpose was not to verify the effectiveness of MSCs in animal models but to analyze the possible deficiencies of MSCs in ALI/ARDS basic research through comprehensive analysis and to optimize future basic research methodology to serve the interests of future clinical research. In general, MSC therapy is a potentially effective therapy for ALI/ARDS. However, in the future, more attention should be paid to large animals in basic research; the oxygenation index should be used to standardize the effect of MSCs on oxygenation; the parameters of mechanical ventilation or evaluation of MSCs impact on lung compliance and other such variables should be recorded and reported; and the duration of research should be lengthened to make it possible to evaluate the impact of MSCs on long-term survival.

The main limitation of our meta-analysis is that although 57 animal studies were included, the total number of animal cases included in the meta-analysis was limited due to the small sample size of animal experiments. Second, models that use endotoxin to cause injury are included in this analysis; however, these are sterile models of sepsis and do not fully replicate the complexity of live bacterial infection. Third, 54 of the studies involved research conducted on rodents; only three of them which met the inclusion criteria were conducted on relatively larger animals. In addition, although the research topic is the possible therapeutic effect of MSCs for ALI/ARDS, only a few studies used mechanical ventilation, and only a few studies have reported physiological parameters such as lung compliance/oxygenation index, which were highly different from the clinical settings. The length of the study, the dose, and the origins of MSCs also greatly diverged; curiously, this contradicts the clinical need for a consistent treatment standard. A considerable portion of the included studies was carried out before the publication of the Berlin definition of ARDS. Unlike with clinical research, after the publication of the Berlin definition, a lot of basic research still did not refer to it in the trials. Without a uniform diagnostic standard, it is difficult to judge the severity of lung injury, which generated significant heterogeneity among studies and made it impossible to convincingly quantify MSCs’ efficacy. Finally, none of the included studies evaluated the safety of MSCs in animals, and no relevant meta-analysis was conducted, which may be another limitation of our study.

Conclusion

According to the results from our meta-analyses, MSCs may improve survival and mitigate the severity of lung injury via modulating the immune balance and ameliorating the oxidative stress and permeability of the lungs in ALI/ARDS. Looking toward the future, the optimization and standardization of future MSC research are paramount.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, supplementary_files for Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Attenuate Infection-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Animal Experiments: A Meta-Analysis by Wang Fengyun, Zhou LiXin, Qiang Xinhua and Fang Bin in Cell Transplantation

Acknowledgments

We thank Helen Cadogan, the English teacher of the first author, who helped us for the proof-reading.

Footnotes

Authors Contribution: WFY and ZLX contributed equally to this work, they conceived the idea and analyzed the medical files together. The manuscript was written in English by WFY. QXH made supportive contributions to this work. FB was involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from the First People’s Hospital of Foshan of Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the First People’s Hospital of Foshan of Ethics Committee’s or the Institutional Review Boards’ approved protocols.

Statement of Informed Consent: There are no human subjects in this article and informed consent is not applicable.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Wang Fengyun  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9447-2599

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9447-2599

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, Gattinoni L, Van Haren F, Larsson A, McAuley DF, Ranieri M, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Thomas CM, Smith AF. Pharmacological agents for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7(7):CD004477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hayes M, Curley G, Ansari B, Laffey JG. Clinical review: stem cell therapies for acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome - hope or hype? Crit Care. 2012;16(2):205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Latsinik NV, Panasyuk AF, Keiliss-Borok IV. Stromal cells responsible for transferring the microenvironment of the hemopoietic tissues. Cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation. 1974;17(4):331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bianco P, Cao X, Frenette PS, Mao JJ, Robey PG, Simmons PJ, Wang CY. The meaning, the sense and the significance: translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):35–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guillamat-Prats R, Camprubi-Rimblas M, Bringue J, Tantinyà N, Artigas A. Cell therapy for the treatment of sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(22):446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wuchter P, Bieback K, Schrezenmeier H, Bornhäuser M, Müller LP, Bönig H, Wagner W, Meisel R, Pavel P, Tonn T, Lang P, et al. Standardization of good manufacturing practice-compliant production of bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stromal cells for immunotherapeutic applications. Cytotherapy. 2015;17(2):128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galipeau J, Krampera M, Barrett J, Dazzi F, Deans RJ, DeBruijn J, Dominici M, Fibbe WE, Gee AP, Gimble JM, Hematti P, et al. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy. 2016;18(2):151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Krause DS, Deans RJ, Keating A, Prockop DJ, Horwitz EM. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. the international society for cellular therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(4):315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hooijmans CR, Rovers MM, de Vries RB, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Langendam MW. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monsel A, Zhu YG, Gennai S, Hao Q, Hu S, Rouby JJ, Rosenzwajg M, Matthay MA, Lee JW. Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cell-derived microvesicles in severe pneumonia in Mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(3):324–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cai SX, Liu AR, Chen S, He HL, Chen QH, Xu JY, Pan C, Yang Y, Guo FM, Huang YZ, Liu L, et al. The orphan receptor tyrosine kinase ROR2 facilitates MSCs to repair lung injury in ARDS animal model. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(8):1561–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chailakhyan RK, Aver’yanov AV, Zabozlaev FG, Sobolev PA, Sorokina AV, Akul’shin DA, Gerasimov YV. Comparison of the efficiency of transplantation of bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions and their conditioned media on the model of acute lung injury. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2014;157(1):138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen CH, Chen YL, Sung PH, Sun CK, Chen KH, Chen YL, Huang TH, Lu HI, Lee FY, Sheu JJ, Chung SY, et al. Effective protection against acute respiratory distress syndrome/sepsis injury by combined adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and preactivated disaggregated platelets. Oncotarget. 2017;8(47):82415–82429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen J, Li C, Gao X, Li C, Liang Z, Yu L, Li Y, Xiao X, Chen L. Keratinocyte growth factor gene delivery via mesenchymal stem cells protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen X, Liang H, Lian J, Lu Y, Li X, Zhi S, Zhao G, Hong G, Qiu Q, Lu Z. The protective effect of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell on lung injury induced by vibrio vulnificus sepsis [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2014;26(11):821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen X, Wu S, Tang L, Ma L, Wang F, Feng H, Meng J, Han Z. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing heme oxygenase-1 ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rats. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(5):7301–7319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Masterson C, Devaney J, Horie S, O’Flynn L, Deedigan L, Elliman S, Barry F, O’Brien T, O’Toole D, Laffey JG. Syndecan-2-positive, bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stromal cells attenuate bacterial-induced acute lung injury and enhance resolution of ventilator-induced lung injury in rats. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(3):502–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim ES, Chang YS, Choi SJ, Kim JK, Yoo HS, Ahn SY, Sung DK, Kim SY, Park YR, Park WS. Intratracheal transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuates Escherichia coli-induced acute lung injury in mice. Respir Res. 2011;12(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jerkic M, Masterson C, Ormesher L, Gagnon S, Goyal S, Rabani R, Otulakowski G, Zhang H, Kavanagh BP, Laffey JG. Overexpression of IL-10 enhances the efficacy of human umbilical-cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in E. coli Pneumosepsis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(6):847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fang X, Abbott J, Cheng L, Colby JK, Lee JW, Levy BD, Matthay MA. Human mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells promote the resolution of acute lung injury in part through lipoxin A4. J Immunol. 2015;195(3):875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao P, Yang X, Mungur L, Kampo S, Wen Q. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells attenuate acute lung injury through eNOS and eNOS-derived NO. Int J Mol Med. 2013;31(6):1313–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curley GF, Jerkic M, Dixon S, Hogan G, Masterson C, O’Toole D, Devaney J, Laffey JG. Cryopreserved, xeno-free human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells reduce lung injury severity and bacterial burden in rodent escherichia coli-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):e202–e212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Han J, Lu X, Zou L, Xu X, Qiu H. E-Prostanoid 2 receptor overexpression promotes mesenchymal stem cell attenuated lung injury. Hum Gene Ther. 2016;27(8):621–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hao Q, Zhu YG, Monsel A, Gennai S, Lee T, Xu F, Lee JW. Study of bone marrow and embryonic stem cell-derived human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4(7):832–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. He H, Liu L, Chen Q, Liu A, Cai S, Yang Y, Lu X, Qiu H. Mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 rescue lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(9):1699–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang R, Qin C, Wang J, Hu Y, Zheng G, Qiu G, Ge M, Tao H, Shu Q, Xu J. Differential effects of extracellular vesicles from aging and young mesenchymal stem cells in acute lung injury. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(18):7996–8014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang ZW, Liu N, Li D, Zhang HY, Wang Y, Liu Y, Zhang LL, Ju XL. Angiopoietin-1 modified human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy for endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in rats. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58(1):206–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hu Y, Qin C, Zheng G, Lai D, Tao H, Zhang Y, Qiu G, Ge M, Huang L, Chen L, Cheng B. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages ameliorate LPS-induced systemic response. Mediators of Inflamm. 2016;2016:3735452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Devaney J, Horie S, Masterson C, Elliman S, Barry F, O’Brien T, Curley GF, O’Toole D, Laffey JG. Human mesenchymal stromal cells decrease the severity of acute lung injury induced by E. coli in the rat. Thorax. 2015;70(7):625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Silva JD, de Castro LL, Braga CL, Oliveira GP, Trivelin SA, Barbosa-Junior CM, Morales MM, Dos Santos CC, Weiss DJ, Lopes-Pacheco M, Cruz FF, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells are more effective than their extracellular vesicles at reducing lung injury regardless of acute respiratory distress syndrome etiology. Stem Cells Int. 2019;2019:8262849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ionescu L, Byrne RN, van Haaften T, Vadivel A, Alphonse RS, Rey-Parra GJ, Weissmann G, Hall A, Eaton F, Thébaud B. Stem cell conditioned medium improves acute lung injury in mice: in vivo evidence for stem cell paracrine action. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303(11):L967–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pedrazza L, Cunha AA, Luft C, Nunes NK, Schimitz F, Gassen RB, Breda RV, Donadio MV, de Souza Wyse AT, Pitrez PM, Rosa JL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells improves survival in LPS-induced acute lung injury acting through inhibition of NETs formation. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232(12):3552–3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liang ZX, Sun JP, Wang P, Qing TI, Zhen YA, Chen LA. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect rats from endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Chin Med J. 2011;124(17):2715–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li D, Liu Q, Qi L, Dai X, Liu H, Wang Y. Low levels of TGF-beta1 enhance human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell fibronectin production and extend survival time in a rat model of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(2):1681–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li JW, Wu X. Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate LPS-induced acute lung injury through KGF promoting alveolar fluid clearance of alveolar type II cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(13):2368–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li J, Li D, Liu X, Tang S, Wei F. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce systemic inflammation and attenuate LPS-induced acute lung injury in rats. J Inflamm (Lond). 2012;9(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lang L, Liang D, Fei G, Hui J, Chen Y, Yan J. Effects of Hippo signaling pathway on lung injury repair by mesenchymal stem cells in acute respiratory distress syndrome [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2019;31(3):281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu G, Lv H, An Y, Wei X, Yi X, Yi H. Tracking of transplanted human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells labeled with fluorescent probe in a mouse model of acute lung injury. Int J Mol Med. 2018;41(5):2527–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu L, He H, Liu A, Xu J, Han J, Chen Q, Hu S, Xu X, Huang Y, Guo F, Yang Y. Therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in models of pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute lung injury. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(12):2629–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Soliman MG, Mansour HA, Hassan WA, El-Sayed RA, Hassaan NA. Mesenchymal stem cells therapeutic potential alleviate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in rat model. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2018;32(11):e22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khatri M, Richardson LA. Therapeutic potential of porcine bronchoalveolar fluid-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in a pig model of LPS-induced ALI. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(7):5447–5457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maron-Gutierrez T, Silva JD, Asensi KD, Bakker-Abreu I, Shan Y, Diaz BL, Goldenberg RC, Mei SH, Stewart DJ, Morales MM, Rocco PR, et al. Effects of mesenchymal stem cell therapy on the time course of pulmonary remodeling depend on the etiology of lung injury in mice. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(11):e319–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dezfouli MR, Fakhr MJ, Chaleshtori SS, Dehghan MM, Vajhi A, Mokhtari R. Intrapulmonary autologous transplant of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells improves lipopolysaccharide-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome in rabbit. Critical Care. 2018;22(1):353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gupta N, Su X, Popov B, Lee JW, Serikov V, Matthay MA. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1855–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gupta N, Sinha R, Krasnodembskaya A, Xu X, Nizet V, Matthay MA, Griffin JH. The TLR4-PAR1 axis regulates bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell survival and therapeutic capacity in experimental bacterial pneumonia. Stem Cells. 2018;36(5):796–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gupta N, Nizet V. Stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha augments the therapeutic capacity of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in experimental pneumonia. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Qin ZH, Xu JF, Qu JM, Zhang J, Sai Y, Chen CM, Wu L, Yu L. Intrapleural delivery of MSCs attenuates acute lung injury by paracrine/endocrine mechanism. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(11):2745–2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ren H, Zhang Q, Wang J, Pan R. Comparative Effects of umbilical cord- and menstrual blood-derived mscs in repairing acute lung injury. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:7873625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shalaby SM, El-Shal AS, Abd-Allah SH, Selim AO, Selim SA, Gouda ZA, Abd El Motteleb DM, Zanfaly HE, EL-Assar HM, Abdelazim S. Mesenchymal stromal cell injection protects against oxidative stress in Escherichia coli-induced acute lung injury in mice. Cytotherapy. 2014;16(6):764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mei SH, McCarter SD, Deng Y, Parker CH, Liles WC, Stewart DJ. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4(9):e269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Song L, Xu J, Qu J, Sai Y, Chen C, Yu L, Li D, Guo X. A therapeutic role for mesenchymal stem cells in acute lung injury independent of hypoxia-induced mitogenic factor. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(2):376–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sun J, Han ZB, Liao W, Yang SG, Yang Z, Yu J, Meng L, Wu R, Han ZC. Intrapulmonary delivery of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells attenuates acute lung injury by expanding CD4+CD25+ Forkhead Boxp3 (FOXP3)+ regulatory T cells and balancing anti- and pro-inflammatory factors. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;27(5):587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Asmussen S, Ito H, Traber DL, Lee JW, Cox RA, Hawkins HK, McAuley DF, McKenna DH, Traber LD, Zhuo H, Wilson J, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells reduce the severity of acute lung injury in a sheep model of bacterial pneumonia. Thorax. 2014;69(9):819–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Danchuk S, Ylostalo JH, Hossain F, Sorge R, Ramsey A, Bonvillain RW, Lasky JA, Bunnell BA, Welsh DA, Prockop DJ, Sullivan DE. Human multipotent stromal cells attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice via secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 6. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2011;2(3):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tai WL, Dong ZX, Zhang DD, Wang DH. Therapeutic effect of intravenous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation on early-stage LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2012;32(3):283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tang XD, Shi L, Monsel A, Li XY, Zhu HL, Zhu YG, Qu JM. Mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles attenuate acute lung injury in mice partly mediated by Ang-1 mRNA. Stem Cells. 2017;35(7):1849–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang C, Lv D, Zhang X, Ni ZA, Sun X, Zhu C. Interleukin-10-overexpressing mesenchymal stromal cells induce a series of regulatory effects in the inflammatory system and promote the survival of endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice model. DNA Cell Biol. 2018;37(1):53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xu J, Qu J, Cao L, Sai Y, Chen C, He L, Yu L. Mesenchymal stem cell-based angiopoietin-1 gene therapy for acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Pathol. 2008;214(4):472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu M, Liu G, Jia Y, Yan X, Ma X, Wei J, Liu X. Transplantation of human placenta mesenchymal stem cells reduces the level of inflammatory factors in lung tissues of mice with acute lung injury [in Chinese]. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;34(2):105–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu XP, Huang LL, Hu SL, Han JB, He HL, Xu JY, Xie JF, Liu AR, Liu SQ, Liu L, Huang YZ, et al. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiotensin ii type 2 receptor increases cell migration to injured lung in LPS-induced acute lung injury mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7(10):721–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang JX, Zhang N, Wang HW, Gao P, Yang QP, Wen QP. CXCR4 receptor overexpression in mesenchymal stem cells facilitates treatment of acute lung injury in rats. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(4):1994–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yang Y, Hu S, Xu X, Li J, Liu A, Han J, Liu S, Liu L, Qiu H. The Vascular endothelial growth factors-expressing character of mesenchymal stem cells plays a positive role in treatment of acute lung injury in vivo. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:2347938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang S, Jiang W, Ma L, Liu Y, Zhang X, Wang S. Nrf2 transfection enhances the efficacy of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells to repair lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(2):1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang X, Chen J, Xue M, Tang Y, Xu J, Liu L, Huang Y, Yang Y, Qiu H, Guo F. Overexpressing p130/E2F4 in mesenchymal stem cells facilitates the repair of injured alveolar epithelial cells in LPS-induced ARDS mice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 67. Zhang Z, Li W, Heng Z, Zheng J, Li P, Yuan X, Niu W, Bai C, Liu H. Combination therapy of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells and FTY720 attenuates acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in a murine model. Oncotarget. 2017;8(44):77407–77414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhu H, Xiong Y, Xia Y, Zhang R, Tian D, Wang T, Dai J, Wang L, Yao H, Jiang H, Yang K, et al. Therapeutic effects of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in acute lung injury mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):39889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McIntyre LA, Moher D, Fergusson DA, Sullivan KJ, Mei SH, Lalu M, Marshall J, Mcleod M, Griffin G, Grimshaw J, Turgeon A, et al. Efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for acute lung injury in preclinical animal models: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Islam D, Huang Y, Fanelli V, Delsedime L, Wu S, Khang J, Han B, Grassi A, Li M, Xu Y, Luo A, et al. Identification and modulation of microenvironment is crucial for effective mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(10):1214–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shukla MN, Rose JL, Ray R, Lathrop KL, Ray A, Ray P. Hepatocyte growth factor inhibits epithelial to myofibroblast transition in lung cells via Smad7. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(6):643–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chen S, Chen X, Wu X, Wei S, Han W, Lin J, Kang M, Chen L. Hepatocyte growth factor-modified mesenchymal stem cells improve ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury in rats. Gene Ther. 2017;24(1):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang Q, Zhu H, Zhou WG, Zhou WG, Guo XC, Wu MJ, Xu ZY, Jiang JF, Liu HQ. N-acetylcysteine-pretreated human embryonic mesenchymal stem cell administration protects against bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Med Sci. 2013;346(2):113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gamble JR, Drew J, Trezise L, Underwood A, Parsons M, Kasminkas L, Rudge J, Yancopoulos G, Vadas MA. Angiopoietin-1 is an antipermeability and anti-inflammatory agent in vitro and targets cell junctions. Circ Res. 2000;87(7):603–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zheng G, Huang L, Tong H, Shu Q, Hu Y, Ge M, Deng K, Zhang L, Zou B, Cheng B, Xu J. Treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome with allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilson JG, Liu KD, Zhuo H, Caballero L, McMillan M, Fang X, Cosgrove K, Vojnik R, Calfee CS, Lee JW, Rogers AJ. Mesenchymal stem (stromal) cells for treatment of ARDS: a phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(1):24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Matthay MA, Calfee CS, Zhuo H, Thompson BT, Wilson JG, Levitt JE, Rogers AJ, Gotts JE, Wiener-Kronish JP, Bajwa EK, Donahoe MP, et al. Treatment with allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for moderate to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (START study): a randomised phase 2a safety trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(2):154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, supplementary_files for Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Attenuate Infection-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Animal Experiments: A Meta-Analysis by Wang Fengyun, Zhou LiXin, Qiang Xinhua and Fang Bin in Cell Transplantation