Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are of concern because of their very high persistence and impacts on human and environmental health. Currently, many different PFAS (on the order of several thousands) are used in a wide range of applications and there is no comprehensive source of information on the many individual substances and their functions in different applications. Here we provide a broad overview of many use categories where PFAS have been employed and for which function; we also specify which PFAS have been used and discuss the magnitude of the uses. Our compilation is not exhaustive, but it was still possible to demonstrate that PFAS are used in almost all industry branches and many consumer products. In total, more than 200 use categories and subcategories were identified for more than 1400 individual PFAS. The identified use categories include many categories not previously described in the scientific literature but also a lot of well-known categories such as textile impregnation, fire-fighting foam, and electroplating. Besides a detailed description of use categories, the present study also contains a list of the identified PFAS per use category. On this basis, a database of exact masses of 1400 PFAS is provided that is intended to facilitate the analytical detection of many more individual PFAS in the future.

3. Introduction

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of thousands of substances1,2 that have been produced since the 1940s and used in a broad range of consumer products and industrial applications.3 Based on concerns regarding the high persistence of PFAS4 and the lack of knowledge on properties, uses, and toxicological profiles of many PFAS currently in use, it has been argued that the production and use of PFAS should be limited.5 However, there are specific uses that make an immediate ban of all PFAS impractical. Some specific uses of PFAS may currently be essential to health, safety or the functioning of today’s society for which alternatives so far do not exist. On the other hand, if some uses of PFAS are found to be non-essential, they could be eliminated without having to first find alternatives that provide an adequate function and performance. To determine which uses of PFAS are essential and which are not, the concept of “essential use,” as defined under the Montreal Protocol, has recently been further developed for PFAS, including illustrative case studies for several major use categories of PFAS.6

PFAS are costly to produce (e.g. fluorosurfactants are 100–1000 times more expensive than conventional hydrocarbon surfactants per unit volume7) and therefore are often used where other substances cannot deliver the required performance,1 or where PFAS can be used in a much smaller amount and with the same performance as a higher amount of a non-fluorinated chemical. Examples are uses that operate over wide temperature ranges or uses that require extremely stable and non-reactive substances. The C-F bonds in PFAS lead to very stable substances, a feature that also makes them very persistent in the environment. Furthermore, the perfluorocarbon moieties in PFAS are both hydrophobic and oleophobic, making many PFAS effective surfactants or surface protectors.8 PFAS-based fluorosurfactants can lower the surface tension of water to less than 16 mN/m, which is half of what is attainable using hydrocarbon surfactants.8,9 Likewise, the surfaces of fluorinated polymers have about half the surface tension compared to hydrocarbon surfaces. For instance, a close-packed, uniformly organized array of trifluoromethyl (-CF3) groups creates a surface with a solid surface tension as low as 6 mN/m.10

Due to these and other desirable properties, PFAS are used in many different applications. A good overview of the range of uses of PFAS as surfactants and repellents is provided in the monograph by Kissa (2001).3 It lists 39 use categories, mostly derived from patents, and describes the function of PFAS in these use categories. However, the work by Kissa (2001) was published nearly 20 years ago, focused on fluorosurfactants and repellents, and it is not clear which of these uses are still relevant today. In addition to Kissa (2001),3 there are a few other monographs and a large number of peer-reviewed scientific articles and reports that contain information on uses of PFAS.8,11,20,12–19 While these articles and reports provide useful information, each of them focuses on the uses of a specific PFAS group (in specific use categories). This is also the case for the information from the Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC) that is mainly related to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), their precursors, and the PFAS that can be or have been substituted for these PFAS.21–27 The FluoroCouncil28 has provided further information on uses of PFAS. However, the information is rather generic and contains few details about specific uses and substances. Hence, a comprehensive overview that summarizes major current uses is missing.

The present paper, together with the Appendix and the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI), attempts to provide a broad (but not exhaustive) overview of the uses of PFAS. It addresses the following points: i) In which use categories have PFAS been employed and for which functions? ii) Which PFAS have been and are used for a certain category? and iii) What is the magnitude of the uses, and can uses be ranked by quantity? Within the European Union (EU), there are discussions underway for a proposal to restrict PFAS uses to those that are essential and copious information on the uses will be needed to prepare such a restriction proposal.29 The present work is intended to support this process by showing in which applications PFAS are used and which functionality they were selected for.

4. Methods

4.1. Which PFAS are addressed?

A first clear definition of PFAS was provided by Buck et al. (2011).1 They defined PFAS as aliphatic substances with the moiety -CnF2n+1 where n is at least 1. The OECD/UNEP Global PFC Group noted that many substances, containing other perfluorocarbon moieties (e.g. -CnF2n-), were not commonly recognized as PFAS according to Buck et al. (2011), e.g. perfluorodicarboxylic acids.2 Considering their structural similarities to commonly recognized PFAS with the -CnF2n+1 moiety, the OECD/UNEP Global PFC Group proposed to also include substances that contain the moiety -CnF2n- (n ≥ 1) as PFAS.2 The present study is in line with this proposal. In contrast to the definition by Buck et al. (2011), the present study also includes i) substances where a perfluorocarbon chain is connected with functional groups on both ends, ii) aromatic substances that have perfluoroalkyl moieties on the side chains, and iii) fluorinated cycloaliphatic substances.

More specifically, the present study focuses on polymeric PFAS with the -CF2- moiety and non-polymeric PFAS with the -CF2-CF2- moiety. It does not include non-polymeric substances that only contain a -CF3 or -CF2- moiety, with the exception of perfluoroalkylethers and per- and polyfluoroalkylether-based substances. For per- and polyfluoroalkylethers and per- and polyfluoroalkylether-based substances, those with a -CF2CF2-, -CF2OCF2- or -CF2OCFHCF2- moiety are included.

4.2. Literature sources

The present inventory was started with the risk profiles and risk management evaluations for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS and their related compounds to obtain an overview of uses of these chemicals.21–27 Reports and books that address fluorosurfactants and fluoropolymers in general were also included.3,8,34–40,11,13,17,18,30–33 Literature specific to certain use categories was retrieved for more information either on the substances used, or to understand why PFAS are, or were, necessary for a given use. All specific references are cited in the Electronic Supplementary Information 1 (ESI-1).

In addition, databases, patents, information from PFAS manufacturers and scientific studies that measured PFAS in products were examined. These additional sources are described in more detail in the following subsections. The searches were not exhaustive in any of the sources described, and there are still many more reports, scientific studies, patents, safety data sheets and databases with information on the uses of PFAS than the ones cited here or in the ESI-1.

The information in the tables in the ESI-1 from these sources was marked according to its original source. Information from patents (cited in a book, article or report) was marked with “P”, information on PFAS analytically detected in products with “D”, and information on uses or information without additional reference with “U” for “use” (for more details, see below).

4.2.1. Chemical Data Reporting under the US Toxic Substances Control Act

Manufacturers and importers that produced chemicals in amounts exceeding 25’000 pounds (11.34 metric tons, t) at a site in the US between 2012 and 2015 were obliged to report to the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) in 2016 (data for 2016 to 2019 will be reported in 2020). The data reported in 2016 (available in CSV files) included for each reported substance the name, Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry number and product categories for consumer and commercial uses and sectors, as well as function categories for industrial processing and use. The masses (tonnages) used and exported also had to be reported; however, they are in most cases confidential business information (CBI). The reported data were filtered according to chemical names containing the word “fluoro”. Non-polymeric substances that did not contain the -CF2CF2- moiety and polymeric substances that did not contain the -CF2- moiety subsequently were removed. This left 39 entries where a specific PFAS was applied in a consumer or commercial use, and around 120 entries where a specific PFAS was applied in an industrial processing or use. The entries are labelled with “U” for “use” in the tables in the ESI-1 and ESI-3.

4.2.2. Data from the SPIN database of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden

The Substances in Preparations in Nordic Countries (SPIN) database contains information on substances from the product registers of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.41 There are several cases in which substances do not need to be registered. For example, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden exempt products that come under legislation on foodstuffs and medicinal products from mandatory declaration. Furthermore, the duty to declare products to the product registers does not apply to cosmetic products. In addition, there is in principle no requirement to declare solid processed articles to any of the registers. There is also a general exemption from the duty to declare chemicals in Sweden, Finland and Norway, if the quantity produced or imported is less than 0.1 t per year (in Finland no exact amount is given). Of the Nordic countries, only Denmark and Norway require information on all constituents for most products for which declaration is mandatory. In Sweden, substances that are not classified as dangerous and that make up less than 5 per cent of a product may be omitted from the declaration. In Finland, information on the composition of products is registered from the safety data sheets. Complete information on the exact composition is consequently not necessarily given.

The data that we used in the present study were extracted for us from the SPIN database by an employee of the Swedish Chemicals Agency (KEMI) and the data included only non-confidential information. However, there is also a substantial amount of confidential information in the SPIN database. This is visible when the substances are accessed via the web interface of the SPIN database.41 It was also pointed out to us that not all substances have available use data due to confidentiality.

The database includes four large data sets with information on uses. Two of the data sets (“UC62” and “National use categories”) contain information on specific use categories, while the other two (“Industrial NACE” and “Industry National”) contain information on sectors of uses. In addition to the use categories and sectors of uses, the data sets also contain information on the quantities of a chemical used in a certain use category or sectors of uses if the reported mass exceeds 0.1 t. The available data cover the time period 2000 to 2017. The four data sets were merged and then (as with the TSCA Inventory data) filtered for chemicals containing the word “fluoro”. Those non-polymeric substances that did not contain the -CF2CF2- moiety and polymeric substances that did not contain the -CF2- moiety subsequently were removed. This left 950 entries. Entries with available data for 2017 were labelled as “current use” (U*) in the tables in the ESI-1 and ESI-3, all other entries with “U” for “use”.

4.2.3. Patents

Another important source of information is the patent literature. Patents were searched for via SciFindern 42 (which is the newest version of SciFinder) and Google Patents.43 The patent search in SciFindern was mostly conducted via keywords and the constraint that the patent must contain a substance with the -CF2-CF2- moiety. This can be done in SciFindern by using the “draw” function. Google Patents was mainly used to search for a full patent text (via the patent number) when SciFindern only provided the abstract of the patent. The advantage of SciFindern (which belongs to CAS) is that experts manually curate the substances described in the patents and provide CAS numbers. All substances identified in the patent are visible in SciFindern together with the patent. Through the patents it was possible to determine in which applications PFAS may be used. While it is not possible to determine whether licenses for a patent have been obtained, the status of the patent (e.g. active, withdrawn, expired, not yet granted) can be determined. Active patents become expensive for their owners over the years. Representatives from CAS informed us that it is very likely that a patent is still in use if it is still paid for after 10 to 15 years.44 After 20 years, a patent expires, which means that the invention can be used by others free of cost. Note that many patents cover not just a specific substance, but rather a basic structure to which different functional groups can be attached. The SciFindern experts give CAS numbers to those substances whose existence has been proven by the registrants. Such a proof can be a physical method or the description in a patent document example or claim. Still, it is not always clear which substances are actually used in practice. Patents were found for many uses, and the patented substances are included in the tables in the ESI-1, labelled with “P” for “patent”.

4.2.4. Information from companies that manufacture or sell PFAS

3M, Chemours, DuPont, F2 Chemicals, Solvay, and other PFAS manufacturers describe on their webpages which products they make and what these can be used for. Separate factsheets are also available for some of the products, for example, for fluorocarbons from F2 Chemicals,45 3M™Novec™ Engineered Fluids46–49 or Vertrel™ fluids from Chemours.50 The difficulty with this information is that it is often not specified which substances are contained in the products. Sometimes the safety data sheets provide information about the composition of the products, but in most cases they do not. Dozens of factsheets and safety data sheets were screened for the present study and the information on the PFAS they contained was extracted. However, it was not feasible, in a reasonable amount of time, to examine all factsheets and safety data sheets of the major PFAS manufacturers. The data included in the tables in the ESI-1 are labelled with “U” for “use”.

4.2.5. Studies that measured PFAS in products

There are also numerous individual studies that analysed PFAS in products, for example in fire-fighting foams,51–55 building materials,56 hydraulic fluids and engine oils,57 impregnation sprays,58,59 or various other consumer products.35,60–65 These studies are important because they show in which products PFAS exist. However, in most studies only a handful of substances were analysed and even for these substances it is not clear whether they were used intentionally, impurities in the actual substances or degradation products. The data included in the tables in the ESI-1 are labelled with “D” for “detected analytically”.

4.2.6. Market reports

A variety of non-verified commercial market reports exist for PFAS. Examples are the Fluorotelomer Market Report, Fluorochemicals Market Report or the Perfluoropolyether Market Report from Global Market Insights.66–68 The information from these reports is not included in this study as these reports do not state their information sources and thus cannot be verified.

4.3. Nomenclature

In the present study, a distinction is made between use categories and subcategories. A use category can, but does not necessarily, have subcategories. An example of a use category for PFAS is sport articles; a subcategory under sport articles is tennis rackets.

A distinction is also made between use, function and property. The “use” is the area in which the substances are employed. This can either be the use category or the subcategory. The “function” is the task that the substances fulfil in the use, and the “properties” indicate why PFAS are able to fulfil this function. An example for a use would be chrome plating. In chrome plating, PFAS have the function to prevent the evaporation of hexavalent chromium (VI) vapour, because of the PFAS properties that lower the surface tension of the electrolyte solution and since the PFAS used are stable under strongly acidic and oxidizing conditions.3

In the present study, the term “individual PFAS” always refers to substances with a CAS number, irrespective of whether they are mixtures, polymers or single substances.

4.4. Classification of use categories

The use categories in the present study were developed and refined throughout the course of the project to have as few well-defined use categories as possible that were not too broad. Initially, the use categories as defined by Kissa (2001)3 were employed, but they are very specific and thus broader categories were needed to cover the identified uses. Examples of use categories from Kissa (2001) which were assigned to broader categories are “molding and mold release” (in the present study a subcategory under “production of plastic and rubber”), “oil wells” (in the present study a subcategory with a slightly different name under “oil & gas”), and “cement additives” (in the present study a subcategory under “building and construction”). In the course of the project, more use categories were defined as additional uses were added. The use categories in the present study were finally divided into “industrial branches” and “other use categories” to make a distinction between use categories that define broad industrial branches such as the “semiconductor industry” or the ”energy sector”, and use categories that are more specific such as “personal care products” or “sealants and adhesives”. Note that some of the “other use categories” may be applied to several of the “industry branches”. For example, “wire and cable insulations” may be applied in “aerospace”, “biotechnology”, “building and construction”, “chemical industry” and others.

Overall, the use categories defined in the present study are very similar to the categories of the SPIN database, although some categories of the SPIN database are more specific (and correspond to subcategories in the present study). Examples of very similar categories are “anti-foaming agents, foam-reducing agents” (SPIN database) and “antifoaming agent” (present study), “construction” (SPIN database) and “building and construction” (present study) or “cleaning/washing agents” (SPIN database) and “cleaning compositions” (present study). Some of the categories in the SPIN database could not be assigned to any of the use categories in the present study because they were too general. Examples are “impregnation”, “surface treatment”, “anti-corrosion materials” or “manufacture of other transport equipment”. Although the substances from these categories are not included in the present study, their quantities appear in Figure 3 and Figure 4 under “various”.

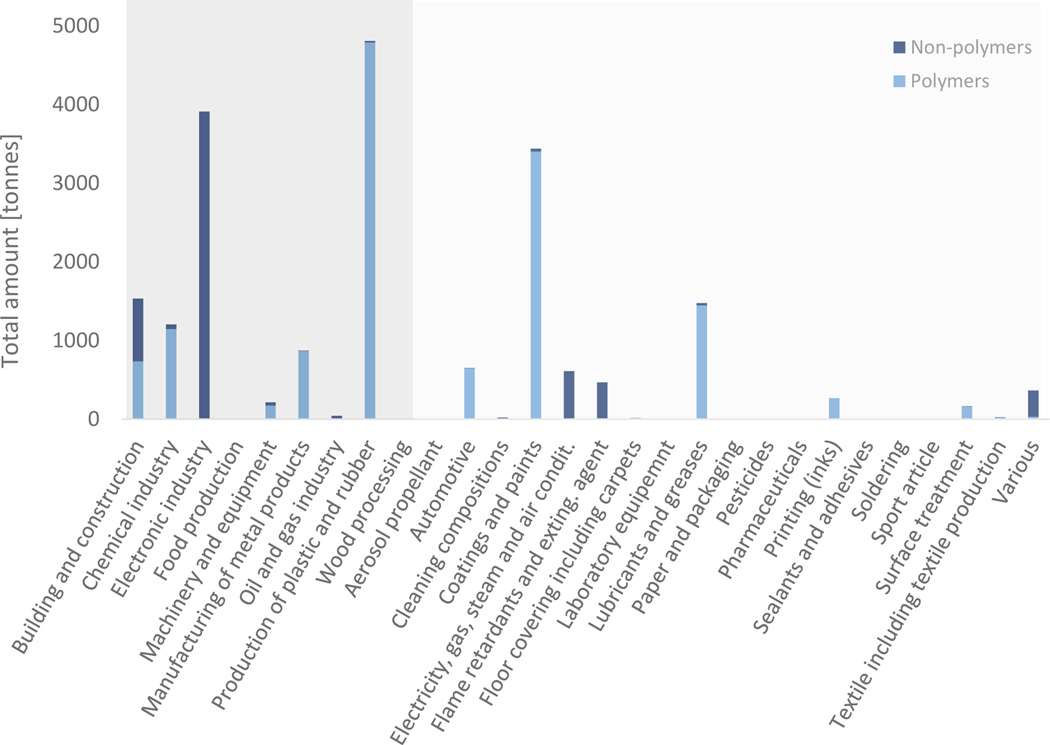

Figure 3:

Amount of PFAS employed in the different use categories in Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark from 2000 to 2017, as reported in the SPIN database.41 Polymers include fluoropolymers and perfluoropolyethers. Side-chain fluorinated polymers have not been used above 0.2 t in any of the uses. Use categories with dark background are industrial branches, use categories with light grey background are other use categories.

4.5. What kind of information can be found where in this article?

The present study comes with an Appendix that lists the main functions of the PFAS in the use categories and subcategories that we identified. In addition, we indicate which properties of the PFAS are important for the identified function. The Appendix thus contains the main results of the present study in a condensed form and is therefore part of the main paper and not part of the ESI.

The ESI of the present study is divided into three parts. ESI-1 is a comprehensive document with 250 pages. It is available as a pdf, but can also be provided upon request as an MS Word document. ESI-1 is intended to be used as a reference document and contains a detailed description of all uses that were collected here as well as the PFAS employed in these categories with names, structural formulas and CAS numbers.

In addition, there is an MS Excel workbook (ESI-2) that contains all PFAS that appear in ESI-1. This workbook has a worksheet for each of the most common PFAS groups such as perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAA), perfluoroalkane sulfonyl fluoride (PASF)-based substances, or fluorotelomer-based substances and, thus, offers a good overview of the described PFAS. A list of what is included in the different worksheets is provided in the first worksheet. ESI-2 is primarily intended as a reference for readers who do not have access to SciFindern or other chemical databases or who just want to look up the name or structural formula for a specific CAS number. In addition to name, CAS number, and structural formula, ESI-2 also contains the identified uses of each PFAS. In contrast to ESI-1, ESI-2 assigns the uses to the PFAS (and not the PFAS to the uses).

The third part of the ESI (ESI-3) is also an Excel workbook that provides a separate worksheet for each use category. These worksheets list the PFAS from the ESI-1 with the names, CAS numbers, elemental compositions, and exact monoisotopic masses of the substances. Our intention is that the lists can be added to accurate mass spectrometry libraries and thus help to identify unknown PFAS more easily in the future. For this purpose, it would be helpful to connect the CAS numbers in the ESI-3 with e.g. the Norman SusDat ID of the NORMAN Substance Database69 and perhaps to commercial mass spectrometry libraries in the future.

5. Results

In the present study, more than 200 uses in 64 use categories were identified for more than 1400 individual PFAS. This means that the present study encompasses five times as many uses (counted as use categories plus subcategories) than included by Kissa (2001)3. This shows that the present study goes much further than simply updating this previous work. The following subsections describe the identified use categories and substances and show and discuss the most important use categories in terms of quantities used, based on the data of the SPIN database and the Chemical Data Reporting database under the TSCA.

5.1.1. In which use categories have PFAS been employed and for which function?

The Appendix to the present study sets forth the use categories identified and answers the question of why PFAS were employed for a specific use. The use categories identified in this study are divided into “industry branches” and “other use categories”, as listed in Table 1. In total, 86 uses within the 20 industry branches and 124 uses within the 44 other use categories were identified. Among the use categories, medical utensils and the semiconductor and automotive industries have the largest numbers of subcategories. About one-seventh of the subcategories have been identified by patents, and one-twentieth by studies that have measured PFAS in products (see ESI-3). The remaining categories have been mentioned previously in other publications.

Table 1:

Industry branches and other use categories where PFAS were or are employed. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of subcategories. No parentheses indicate no subcategories.

| Industry branches | |

| Aerospace (7) | Mining (3) |

| Biotechnology (2) | Nuclear industry |

| Building and construction (5) | Oil & gas industry (7) |

| Chemical industry (8) | Pharmaceutical industry |

| Electroplating (2) | Photographic industry (2) |

| Electronic industry (6) | Production of plastic and rubber (5) |

| Energy sector (10) | Semiconductor industry (11) |

| Food production industry | Textile production (2) |

| Machinery and equipment | Watchmaking industry |

| Manufacture of metal products (7) | Wood industry (3) |

| Other use categories | |

| Aerosol propellants | Metallic and ceramic surfaces |

| Air conditioning | Music instruments (3) |

| Antifoaming agent | Optical devices (3) |

| Ammunition | Paper and packaging (2) |

| Apparel | Particle physics |

| Automotive (12) | Personal care products |

| Cleaning compositions (6) | Pesticides (2) |

| Coatings, paints and varnishes (3) | Pharmaceuticals (2) |

| Conservation of books and manuscripts | Pipes, pumps, fittings and liners |

| Cookware | Plastic and rubber (3) |

| Dispersions | Printing (4) |

| Electronic devices (7) | Refrigerant systems |

| Fingerprint development | Resins (3) |

| Fire-fighting foam (5) | Sealants and adhesives (2) |

| Flame retardants | Soldering (2) |

| Floor covering including carpets and floor polish (4) | Soil remediation |

| Glass (3) | Sport article (6) |

| Household applications | Stone, concrete and tile |

| Laboratory supplies, equipment and | Textile and upholstery (2) |

| instrumentation (4) | Tracing and tagging (5) |

| Leather (4) | Water and effluent treatment |

| Lubricants and greases (2) | Wire and cable insulation, gaskets and hoses |

| Medical utensils (14) | |

The identified uses included many uses not previously described in the scientific literature on PFAS. Some examples of those uses are PFAS in ammunition, climbing ropes, guitar strings, artificial turf, and soil remediation. Also, additional subcategories of PFAS in already described use categories such as in the semiconductor industry were identified. For example, in addition to the subcategories etching agents, anti-reflective coatings, or photoresists, PFAS are also employed for wafer thinning (patent US20130201635 from 2013)42 and as bonding ply in multilayer printed circuit boards (patent WO2003026371 from 2003) in the semiconductor industry.42 In the energy sector, PFAS are known to be employed in solar collectors and photovoltaic cells, and in lithium-ion, vanadium redox, and zinc batteries. In addition, fluoropolymers are also used to coat the blades of wind mills20 and PFAS can be employed in the continuous separation of carbon dioxide in flue gases (patent CN106914122 from 2017)42 and as heat transfer fluids in organic Rankine engines.45 These examples all show that the uses of PFAS are much more extensive than so far reported in the scientific literature.

Altogether, we were able to identify almost 300 functions of PFAS (listed in the Appendix). Examples of those functions are foaming of drilling fluids, heat transfer in refrigerants, and film forming in AFFFs. The properties that led to the use of the PFAS are also identified. These include among others: ability to lower the aqueous surface tension, high hydrophobicity, high oleophobicity, non-flammability, high capacity to dissolve gases, high stability, extremely low reactivity, high dielectric breakdown strength, good heat conductivity, low refractive index, low dielectric constant, ability to generate strong acids, operation at a wide temperature range, low volatility in vacuum, and impenetrability to radiation. In the Appendix, these properties are assigned to the specific uses (and functions).

5.1.2. Which PFAS have been and are used for a certain category?

The ESI-1 to the present study describes or lists those PFAS that have been or are currently employed (or have been patented) for each individual use. In total we have found uses for more than 1400 individual PFAS. About one third of these PFAS are also listed in the OECD list.2 This shows that many of the PFAS listed in the present study are on the market, and that many more PFAS that are not on the OECD list may be used or are already being used.

Due to the great variety of uses and the large number of PFAS, it is difficult to make generic statements here. Overall, it was found that the number of different PFAS identified for a certain use mostly depends on the properties required for that use. PFAS have diverse properties. Some properties, or combinations of properties, are only found in specific groups of PFAS. For example, perfluorocarbons seem to be particularly well suited as vehicles for respiratory gas transport due to the high solubility of oxygen therein. Similarly, anionic PFAS (largely those with a sulfonic acid group) are used as additives in brake and hydraulic fluids due to their ability to alter the electrical potential of the metal surface and thus, protect the metal surface from corrosion through electrochemical oxidation. In contrast, there are also properties that are shared by many different groups of PFAS. Many PFAS are very stable and many can reduce the surface tension of aqueous solutions considerably, improving wetting and rinse-off. Therefore, a typical use in which many different types of PFAS have been or are used is in cleaning compositions. The patented, analytically detected and employed PFAS for this use include PFAAs, PASF-based substances, and fluorotelomer-based substances (see ESI-1 Section 2.6.1). A similar variety of PFAS (90 substances in total) were identified in patents for photographic materials to control surface tension, electrostatic charge, friction, adhesion, and dirt repellency.

This array of different PFAS may be surprising, but it shows that some properties of PFAS are shared across many PFAS groups. The large number of patented PFAS for the same use raises the question of whether some of these substances offer better performance than others, or whether it does not really matter which PFAS are employed. The latter would indicate that manufacturers can invent new PFAS quite easily to avoid license fees for patents of other manufacturers.

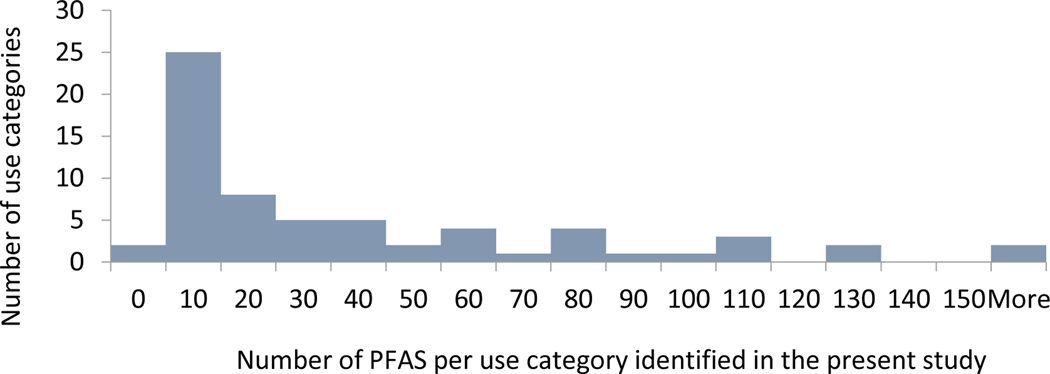

For the majority of uses, however, far fewer PFAS were identified. Figure 1 highlights the use categories grouped according to the number of PFAS identified. It should be noted that the number of PFAS reflects the number that we have identified in the present study, and not the number of substances on the market or available for a certain use. For half of the use categories, we have identified more than 20 PFAS, and for seven use categories more than 100 PFAS. The use categories with more than 100 identified PFAS are “photographic industry”, “semiconductor industry”, “coatings, paints and varnishes”, “fire-fighting foams”, “medical utensils”, “personal care products”, and “printing”. There are also two categories where no specific substances were identified. These are “ammunition” and “nuclear industry”.

Figure 1:

Use categories grouped according to the number of PFAS identified. The use categories are those mentioned in Table 1 without distinction of subcategories. Identified PFAS included PFAS detected analytically in products, patented and employed PFAS.

The most frequently identified PFAS in our literature search are non-polymeric fluorotelomer-based substances, followed by non-polymeric PASF-based substances and PFAAs. Other identified non-polymeric substances are perfluoroalkyl phosphinic acids (PFPIA)-based substances, perfluoroalkyl carbonyl fluoride (PACF)-based substances, cyclic PFAS, aromatic substances with fluorinated side-chains, per- and polyfluoroalkyl ethers, hydrofluoroethers, and other non-polymers. Polymeric substances include fluoropolymers, side-chain fluorinated polymers, and perfluoropolyethers (see also ESI-2). There is also a variety of substances in the groups themselves, especially among the non-polymeric fluorotelomer-based and PASF-based substances. For many of the substances, only one use (or patent for a use) was identified. For example, one use (or patent) was assigned to 372 fluorotelomer-based substances, two uses (or patents) to 39 fluorotelomer-based substances and three or more uses to 33 fluorotelomer-based substances. The reason why so many PFAS have only one identified use may be that not all the uses were identified for all PFAS. But it also seems that many patents contain “new” PFAS because they work just as well as the established ones.

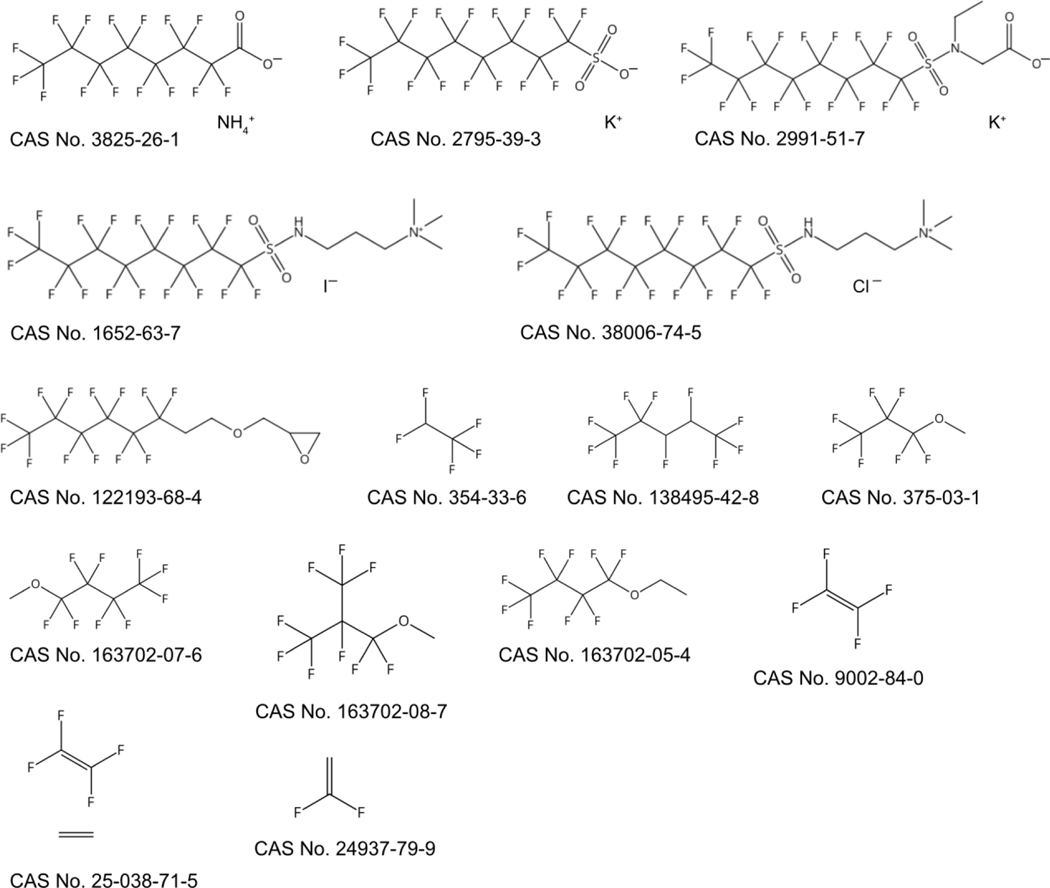

In contrast to the many PFAS with only one assigned use, some PFAS have many uses. ESI-2 illustrates this point: of the 2400 links between individual PFAS and assigned uses, 15 PFAS have been assigned to 10 or more uses (see Table 2 and Figure 2). The exact use counts are not important per se, because there may be more uses for these PFAS that have not been included in the present study, but they demonstrate that some PFAS are employed more frequently than others. It has to be noted that the three fluoropolymers in Table 2 are quite different from the other PFAS in the list, as they represent possibly dozens or hundreds of technical products with different grades and molecular sizes.

Table 2:

PFAS with more than 10 assigned uses. Numbers based on counts of uses and patents, not on detections in products. The structures of these substances are shown in Figure 2.

| Substance | CAS number | Assigned uses |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium perfluorooctanoate | 3825-26-1 | 14 |

| Potassium perfluorooctane sulfonate | 2795-39-3 | 16 |

| Potassium N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamidoacetate | 2991-51-7 | 21 |

| 1-Propanaminium, 3-[[(1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-heptadecafluorooctyl)sulfonyl]amino]-N,N,N-trimethyl-, iodide (1:1) | 1652-63-7 | 17 |

| 1-Propanaminium, 3-[[(1,1,2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,9,9,9-heptadecafluoro octyl)sulfonyl]amino]-N,N,N-trimethyl-, chloride | 38006-74-5 | 21 |

| Oxirane, 2-[[(3,3,4,4,5,5,6,6,7,7,8,8,8-tridecafluorooctyl)oxy]methyl]- | 122193-68-4 | 11 |

| 1H-Pentafluoroethane | 354-33-6 | 10 |

| Pentane, 1,1,1,2,2,3,4,5,5,5-decafluoro- | 138495-42-8 | 12 |

| Methyl perfluoropropyl ether | 375-03-1 | 13 |

| Methyl perfluorobutyl ether | 163702-07-6 | 16 |

| Methyl perfluoroisobutyl ether | 163702-08-7 | 16 |

| Ethyl perfluorobutyl ether | 163702-05-4 | 12 |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | 9002-84-0 | 37 |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) | 24937-79-9 | 17 |

| Ethylene tetrafluoroethylene copolymer (ETFE) | 25038-71-5 | 10 |

Figure 2:

Structures and CAS numbers of the PFAS with more than 10 assigned uses.

Of the 2400 links between individual PFAS and assigned uses, around 42% of the links were obtained from patents, 27% from studies that detected PFAS in products and 31% from publications that reported actual uses.

5.1.3. What is the magnitude of the uses and can uses be ranked by quantity?

To prioritize PFAS uses in the search for alternatives, it is key to know for which uses PFAS were employed the most. Wang et al.12,14,70 published global emission inventories for C4-C14 PFCAs and C6-C10 PFSAs. For PFSAs and their precursors, the highest amounts were identified for the use in “apparel/carpet/textile”, followed by “paper and packaging”, “performance” and “after-market/consumers”. There is also information on the quantities of individual fluoropolymers used.30,71 However, a coherent data set with data covering a wide range of uses and at the same time a wide range of PFAS has not been available so far. The following two subsections will show the magnitude of the uses based on the data from the SPIN database and the Chemical Data Reporting database under the TSCA. Data from REACH that would have covered more countries than the data from the SPIN database are not shown, because the tonnage bands in REACH refer to the substances and not to use categories. Accordingly, only in those cases where a substance has only one use would it have been possible to obtain useful information for this study, which would have created a lot of uncertainty in the data.

Data fom the SPIN database

Figure 3 highlights the total, non-confidential amounts of PFAS employed in the different use categories in Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark between 2000 and 2017.41 It should be noted that the data from these Nordic countries may not be representative of other parts of the world. One reason is that only non-confidential data are included, that substances in foodstuffs, medicinal products, and cosmetics do not have to be declared (see Section 2.2.2) and that there is no fluoropolymer or PFAS production in these countries. Nevertheless, the data from the SPIN database provide a first indication of which uses of PFAS have been important in the last 20 years in this region.

The data illustrate that a large amount of PFAS was used in the production of plastic and rubber, the electronics industry, and coatings and paints (Figure 3). The production of plastic and rubber does not include the production of fluoropolymers. Between 2000 and 2017, more than 3000 t of PFAS were used in the three categories previously mentioned. Around 1500 t of PFAS were used in building and construction and in lubricants and greases and around 1200 t of PFAS in the chemical industry, respectively. All other uses were below 1000 t.

Non-polymers were mainly used in the electronic industry, in buildings and construction, electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply, and flame retardants and extinguishing agents. Of the 6,300 t of non-polymers used in the Nordic countries between 2000 and 2017, 5,650 t (90%) were the hydrofluorocarbon (and greenhouse gas) 1H-pentafluoroethane (CAS No. 354–33-6). More than 70% (470 t) of the remaining non-polymeric PFAS were used in flame retardants and extinguishing agents. The SPIN database has a combined category for these two use categories, so it was not possible to distinguish them.

Polymers were mostly used in the production of plastic and rubber, coatings and paints, lubricants and greases, and in the chemical industry. At least 13,700 t of polymers were used in the Nordic countries between 2000 and 2017, and 10,000 t (73%) of this was PTFE. This percentage is a bit higher than the numbers published recently by AGC, which stated that 53% of the 320’000 t of fluoroplastics consumed worldwide in 2018 was PTFE.71

Data from the Chemical Data Reporting under the TSCA

Under the TSCA, the Chemical Data Reporting lists under “volume” the amount of a substance in a certain sector and function category or product category. However, more than 80% of the volume entries in the Chemical Data Reporting database are CBI. The certainty of the available information is therefore low, but a general statement is still possible. Table 3 highlights the non-confidential data on used and exported amounts of PFAS for the different uses based on the data reported in 2016.

Table 3:

Amounts (used + exported) that were not labelled as CBI for the different uses of PFAS from the Chemical Data Reporting under the TSCA from 2016. The rows with grey background are the uses with high amounts indicated by non-confidential data.

| Sector and function | Amount [t] |

|---|---|

| Paint and coating manufacturing - Adhesive and sealant chemicals | 0.001 |

| Industrial gas manufacturing - Air conditioner/refrigeration | 138 |

| Computer and electronic product manufacturing - Solvent for cleaning and degreasing | 1.03 |

| Electrical equipment, appliance, and component manufacturing - Functional fluid | 2180 |

| Fabricated metal product manufacturing - Solvent for cleaning and degreasing | 0.11 |

| All other chemical product and preparation manufacturing - Fire-fighting foam agents | 190 |

| Machinery manufacturing - Functional fluid | 2180 |

| Miscellaneous manufacturing - Solvent for cleaning and degreasing | 0.10 |

| Oil and gas drilling - Surface active agent | 0.022 |

| Paint and coating manufacturing - Adhesives and sealant chemicals | 0.31 |

| Paint and coating manufacturing - Finishing agent | 0.005 |

| Paper manufacturing - Finishing agent | 0.005 |

| Pesticide, fertilizer, and other agricultural chemical manufacturing - Surface active agents | 0.07 |

| Miscellaneous manufacturing - Plating agent and surface treating | 1.96 |

| Printing ink manufacturing - Processing aids, not otherwise listed | 0.001 |

| All other basic inorganic chemical manufacturing - Refrigerant (heat transfer fluid) | 450 |

| Rubber product manufacturing - Rubber compounding | 0.13 |

| Soap, cleaning compound, and toilet preparation manufacturing - Surface active agents | 0.12 |

| Textile, apparel and leather manufacturing - Finishing agents | 0.16 |

The amount of used and exported PFAS was largest for functional fluids in “electrical equipment, appliance, and component manufacturing” and functional fluids in “machinery manufacturing”. The exact same amounts in the two use categories are no coincidence but come from the declaration that 50% of the total amount was used for “electrical equipment, appliance, and component manufacturing” and 50% for “machinery manufacturing”. 1H-pentafluoroethane (CAS No. 354–33-6) accounted for 100% of the total amount in both cases. The high amount of 1H-pentafluoroethane employed as functional fluids in “electrical equipment, appliance, and component manufacturing” confirms the data from the SPIN database that the electronic industry is an important purchaser of this PFAS. The high amount of “functional fluids” in “machinery manufacturing” could be related to refrigerants, air conditioners or other uses, but due to the broadness of the use category, nothing definite can be concluded. Also, as it was found for Europe, no data were available for amounts of non-polymeric PFAS used as processing aids under fluoropolymer production in the US, which may be expected to be a considerable contributor. The same amounts of “finishing agent” in “paint and coating manufacturing” and “paper manufacturing” are again from the declaration 50% and 50%.

6. Discussion

6.1. Scope of the present study and uncertainties

6.1.1. Scope of the present study and uncertainties related to use categories

The present study covers many past and current uses of PFAS. The inventory is not exhaustive and it also contains uncertainties. One area of uncertainty comes from harmonizing entries to the use categories from different sources. This is especially relevant when comparing use amounts, because the reported amounts from the different databases are related to more or less specific use categories that may be defined differently in different databases. Although not quite as critical, this was also a relevant point for the ESI-1. Here, information on specific uses of PFAS was assigned to subcategories and information on broader uses to the main use categories. Still, there were some use categories (especially from the Chemical Data Reporting database under the TSCA) that were so broad that we were not able to assign them to any category in our list. Examples are “surface active agents in all other basic inorganic chemical manufacturing”, or “functional fluids in wholesale and retail trade”. The PFAS listed under such categories and their quantities were not, therefore, considered in the present study.

Another area of uncertainty originates from unidentified uses. We found, for example, that PFAS are used in climbing ropes.72 It therefore cannot be excluded that they are also used in climbing harnesses, but no information was found on this. We did not have the capacity to conduct interviews with industry representatives who might have revealed additional information. We were similarly limited when it came to evaluating the copious amount of information about PFAS uses, for example in reports, scientific papers and patents. Therefore, not all PFAS uses might have been identified in the present study.

In the case of patents in particular, a great amount of information is available, but it should be noted that only some of the PFAS included in patents currently are likely used on the market. In addition to these uncertainties, some of the use category-specific information in the SPIN database is CBI, meaning that we may have not seen all categories. It would be desirable if such information was no longer confidential in the future, in order to inform consumers, users, and regulators.

Nevertheless, the SPIN database is a very valuable source of information and it would be much easier to compile such inventories of uses if other countries had product registries like the Nordic Countries. Without such product registries, the compilation of uses and the substances used remains difficult and lengthy. It would also be advantageous if the uses under REACH were more precisely named. Current categories like “processing aids at industrial sites” or “manufacture of chemicals” are very broad and thus difficult to include.

An important question is whether the majority of the use categories is covered in the present study or whether important use categories are still missing. It is difficult to answer such a question quantitatively, but a qualitative indication is possible when the use categories of the SPIN database are compared to the categories that were already identified. Both categories match very well; only three categories had to be added to accommodate data from the SPIN database in the ESI-1 appropriately. These three categories were “machinery and equipment”, “manufacture of basic metals” and “manufacture of fabricated metal products”. In the latter two categories, it is not clear what PFAS are used for and why. “Manufacture of basic metals” could be linked to mining, and “manufacture of fabricated metal products” could include the coating of metal surfaces e.g. for knives in food production. But both categories are so broad that it is unclear what is really meant. The category “machinery and equipment” could include wire and cable insulations and lubricants. It is known that PFAS are used in both of these categories. However, “machinery and equipment” could also contain other uses of which we are not aware. The Chemical Data Reporting under TCSA mentions the use of PFAS in or as functional fluids in the sector “machinery manufacturing”. This is still relatively vague and could include heat transfer agents, lubricants or any other fluid used in machines. However, with the exception of these three categories, all specific information from the SPIN database could be classified very well into the existing categories of the present study. Overall, we assume that there are no major gaps in the general use categories. However, it is quite possible that subcategories are missing. Among the uses of which we are aware, there may also be some uses where PFAS are no longer employed.

To improve the list of uses in the future, there are several possibilities. Firstly, one could try to get access to product registries of as many countries as possible. Unfortunately, not all product registers are as easily accessible as those of the Nordic countries and many developing countries do not have such a register. The list could also be extended with information from REACH registration dossiers. These dossiers include information of uses and tonnage bands expected to be used at the time of registration. Interviews with manufacturers of products could also generate more information. However, we know from experiences with past projects that manufacturers often want the interviewers to sign a non-disclosure agreement before the interview which prevents using the information obtained in publications. The information from such interviews could still provide some indication as to what kind of information to look for in the public domain. The same is true for the market reports. They can give a clue for what to look for in the public domain (given that they often contain no references). A discouraging factor for researchers who may want to use market reports as data sources is that the companies who generate them often sell them for extortionate sums (i.e. several thousand US dollars) and that most of them are not based on thorough research.73 Another approach could be to use artificial intelligence to systematically search product sales/industry magazines for words or phrases, such as ‘fluor’.

6.1.2. Uncertainties related to substances

Uncertainties also exist regarding the substances identified for a particular use. Some of these uncertainties are already discussed in the Methods section: not all registered patents are used on the market, not all substances included in a patent are used in practice, and substances that have been detected analytically in products might be impurities in or degradation products of the actual substances. In addition, we only looked for examples of PFAS and the lists are by no means complete. Also, the substances included in the present study from the SPIN database are not substances in articles, but substances in preparations. The substances listed in ESI-1 under U or U* are also those that were intentionally used in the products. However, impurities, reaction products upon mixing the ingredients, and degradation products of the intentionally added PFAS might also be present in products. Industrial blends are rarely pure, but can be only 80% of the registered substance, so 20% can be impurities, reaction by-products, degradation products etc.

In addition, industry tends to evolve around consumer needs, costs savings, and external factors such as regulatory oversight, and substances used today may no longer be relevant tomorrow. A better overview of the substances being used could be obtained if manufacturers had to list which substances are contained in a product in the safety data sheets. However, except for a few instances (e.g. when uses are authorized for food contact materials in Germany), this is not the case and patents are therefore often the only way to find out what a product (might) contain. A better overview of the substances used would also be possible - at least for the US - if substances with tonnages below the reporting threshold of 11.34 t were also included in the TSCA Chemical Data Reporting database. In the EU, it would be helpful if the registration dossiers under REACH as well as other legislations not covered by REACH were updated regularly with a more detailed breakdown of which quantities of the substances are used, and in which applications.

6.1.3. Uncertainties related to quantities

The third part of the present study - identifying the key use categories in terms of quantities - also contains various uncertainties. The data from the SPIN database only represent the Nordic countries, while many industry branches have a greater presence in other countries or regions of the world than in the Nordic countries. Additionally, many of the volumes in the SPIN database are CBI. The SPIN database does also not include all uses. An example is that foodstuff, and hence food packaging is not reported to the SPIN database, which possibly could explain why ‘packaging’ which was significant in the OECD study, did not stand out in the SPIN survey. Similar, non-polymeric PFAS such as ADONA and GenX are used as processing aids during fluoropolymer production. The quantities of these processing aids are not captured in the statistics of the SPIN database since this activity is not ongoing in Scandinavia. However, the considerable amounts of fluoropolymers produced in Europe of about 52,000 t per year, and about 230,000 t globally lets us believe that a considerable amount of PFAS is used in this use category in addition to what is shown in Figure 3 under “Chemical industry”.

The data from the US are only partly helpful, because a large part of the reported amounts is CBI and only substances above 11.34 t at a single site have been reported. Although in some use categories large quantities of PFAS are employed, it is difficult to compare the amounts, because the unreported amounts due to CBI could be much larger than the non-confidential reported amounts. The extent of the uncertainties in the SPIN database due to the CBI cannot be estimated with the available data, but could be large. It would be helpful if regulatory agencies, such as the US EPA, could create a ranking of the PFAS uses (without stating any numbers) based on the entire datasets they have collected.

6.2. Findings of the present study with regard to uses

The present study is a renewed and expanded effort to systematically compile a wide range of known as well as many overlooked uses of PFAS. Besides describing the uses of PFAS, we also endeavoured to explain which functions the PFAS fulfil in these uses. The descriptions of the functions and properties of the PFAS employed are especially important for determining “non-essential” use categories and identifying alternatives for those uses currently considered “essential”.

However, as can be seen from the question marks in the Appendix it was not always possible to determine why PFAS were used or needed in a particular case. In 4% of the cases we could not clarify which function the PFAS fulfil in the use category or subcategory, and in 21% of the cases we could not clarify which property is needed to fulfil the mentioned function. For example, we do not know exactly why PFAS are employed in the ventilation of respiratory airways, in brake-pad additives, and in resilient linoleum. It would be important to engage with product manufacturers to understand what function the PFAS have, in order to identify appropriate replacements. Some of the uses might also be judged as “non-essential” and thus could be eliminated or discontinued.

Our study also shows that in several areas where large quantities of PFAS are employed, discussions concerning alternatives are still not underway in the public domain. In general, in recent years the focus in the search for alternatives for PFAS has been on fire-fighting foams,74,75 paper and packaging,76,77 and textiles.78–81 This focus was certainly appropriate, because these are uses where PFAS are in direct contact with the environment (fire-fighting foam) or with humans (food packaging, textiles). However, our study shows that PFAS are also used widely in the production of electronics and in machinery manufacturing, and at least in the Nordic countries in the production of plastic and rubber and in paints and coatings. Measuring and/or reporting emissions along the life cycles of these uses, and the search for alternatives in these use categories should therefore also be prioritized. These uses could for instance be included in the activities for which data have to be reported under the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Registry.

It would also be important to look for alternatives in industry branches that use smaller amounts of PFAS or that are not included in the SPIN database or Chemical Data Reporting database, but produce large amounts of wastewater, exhaust or solid waste containing PFAS. More information is needed to prioritize the various use categories, but potentially worrisome categories where environmental contamination has been documented are fluoropolymer production,82–84 the semiconductor industry,85,86 and metal plating.87

Other uses where humans are in direct contact with PFAS and that have not yet gained much attention regarding alternatives include: personal care products and cosmetics, pesticides, pharmaceuticals (including eye drops), printing inks, and sealants and adhesives. A search for alternatives would also be important here.

6.3. Findings of the present study with regard to substances

We can ascertain from the SPIN database that two PFAS, 1H-pentafluoroethane and PTFE, account for 75% of the quantities used in the Nordic countries. One explanation is that PTFE and 1H-pentafluoroethanes are not used as additives, but as the main products. For example, entire roof structures or coatings are made of out of PTFE.28 For 1H-pentafluoroethane (also known as HFC-125), one of the main uses is as a heat transfer fluid and cooling agent,41,88 which could explain the large quantities of that substance used.

Other PFAS used as surfactants are utilized in much smaller quantities probably due to their high market price. They may therefore not appear (or at least not in high amounts) in databases such as the SPIN database or the Chemical Data Reporting database, which only report substances (or masses) above a certain threshold. PFAS used in articles, which are manufactured mainly in Asia or other countries outside the EU or the US, may also not appear in large amounts in the SPIN or Chemical Data Reporting database, simply because the databases do not contain information on PFAS in articles. The PFAS that we have listed as examples in ESI-1 are mainly those used in Europe or North America. A recent publication89 lists e.g. seventy PFAS from the Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances Produced or Imported in China (IECSC) that are not in the North American and European chemical inventories. These PFAS are also not in our inventory, because no information on their intended use was provided.

Concerning the currently used PFAS, it was thought - due to the voluntary phase out of all PFAS products derived from perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride by 3M90 and the voluntary PFOA Stewardship Program in which eight companies agreed to phase out 95% of uses by 201591 - that at least ammonium perfluorooctanoate and potassium perfluorooctane sulfonate are no longer in use in the US. However, other companies have not been prevented from taking over the market, and there has been very limited enforcement of the actual phase-out through regulation. A recent article revealed that PFAS that can break down into PFOA and PFOS are still in use in the US.92 Those uses include coatings for medical devices, apparel, and other industries, and equipment in pharmaceutical companies. PFAS that can break down into PFOA and PFOS are also still used in semiconductor and electronics companies.92

6.4. Use and implications of the present study

The large number of uses that exist for PFAS, together with the large number of individual substances, makes their regulation and eventual phase-out very challenging. The approach of allowing PFAS only in “essential uses”, as suggested for example in the EU strategy paper “Elements for an EU-strategy for PFAS”,5 will not be easy to implement if regulators try to assess all uses individually. An alternative approach could be to deem all PFAS uses as “non-essential” unless producers or users make a convincing case for essentiality, and that authorities set a sunset clause on “essential uses”.

The number of use categories for both non-essential and essential cases is critical to estimate the amount of work that would need to be done, for example, to prepare a restriction proposal under REACH (as planned by five European countries29). The descriptions in the present study of where and why PFAS are used can be used to provide an overview of the uses and may also facilitate an understanding of what alternatives need to be developed and with which priority.

The information in this study may also help regulators and scientists determine which PFAS to measure in contaminated areas, in humans in surrounding communities and in products. To facilitate the identification of PFAS in various matrices, we provide the ESI-3 file, which contains for each use category the name, CAS number, and exact monoisotopic mass of the substance. The ESI-3 file also includes information on whether PFAS were identified in a patent, detected analytically in products or reported as employed substances. Laboratories could use modern analytical methods such as suspect-screening analysis utilising accurate mass spectrometry to identify novel and emerging PFAS listed in ESI-3.51,93 Patented substances may be less likely to be on the market and could be excluded or given a lower priority or weighting in suspect screening workflows. Similar lists (such as the ESI-3) are provided by the OECD/UNEP Global PFC Group,2 Zhang et al. (2020),89 the US EPA, the NORMAN Substance Database69 and others. An overview is provided under https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard/chemical_lists. However, only a few of these lists also contain information on uses.

The ESI-3 may also be valuable for identifying sources of PFAS in the environment. Some uses may impart characteristic PFAS “fingerprints” (i.e. PFAS contamination patterns) to environmental samples that could be used to identify a source, e.g. through statistical methods.94 On the other hand, many environments will be impacted by multiple sources and such fingerprinting methods could be challenging in practice.

7. Conclusions

The present study is the first of its kind to systematically compile a wide range of known as well as poorly documented uses of PFAS. The compilation is not exhaustive, but it is still possible to demonstrate that PFAS are used in almost all industry branches and in many consumer products. Some consumer products even have multiple applications of PFAS within the same product. A cell phone for example contains fluoropolymer wiring, PFAS in the circuit boards/semiconductors, and a screen coated with a fingerprint-resistant fluoropolymer. The search for alternatives is therefore a very challenging and extensive task. The data in the present study can help prioritize the search for alternatives and a matching database of viable alternatives to PFAS would be a logical progression of the present study. It would also be helpful if environmental protection agencies, for example the US EPA, could create a ranking of PFAS uses (without providing tonnages) based on the data they have collected. A ranking without exact figures would still be better than the current situation, in which very little is known about the quantitatively most important use categories due to CBI. The TSCA reform in the US was unfortunately unsuccessful in reducing industry’s excessive use of CBI. Even though CBI may protect a specific industry’s business, it results in overall less protection for consumers, users, and workers from the chemicals. Even regulators are left in the dark about volumes, use categories, and PFAS used, which limits their ability to assess and prevent harm to humans and the environment.

Supplementary Material

2. Environmental Significance Statement.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a large group of more than 4000 substances that are used in a wide range of technical applications and consumer products. Releases of PFAS to the environment have caused large-scale contamination in many countries. For an effective management of PFAS, an overview of the use areas of PFAS, the functions of PFAS in these uses, and the chemical identity of the PFAS actually used is needed. Here we present a systematic description of more than 200 uses of PFAS and the individual substances associated with each of them (over 1400 PFAS in total). This large list of PFAS and their uses is intended to support the identification of essential and non-essential uses of PFAS.

8. Acknowledgement

We thank Stellan Fischer for his help with the data in the SPIN database. J. Glüge acknowledges the financial support of the Swiss Federal Office for the Environmental (FOEN). The authors also thank the Global PFAS Science Panel (GPSP) and the Tides Foundation for supporting this cooperation (grant 1806-52683). In addition, R. Lohmann acknowledges funding from the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant P42ES027706); DeWitt from the US Environmental Protection Agency (83948101), the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1P43ES031009-01) and the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory; C. Ng from the National Science Foundation (grant 1845336) and D. Herzke thanks the Norwegian Strategic Institute Program, granted by the Norwegian Research Council “Arctic, the herald of Chemical Substances of Environmental Concern, CleanArctic”, 117031). We acknowledge contributions from L. Vierke (German Environment Agency), S. Patton (Health and Environment Program, Commonweal) and M. Miller (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, US). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the European Environment Agency or the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

10. Appendix

Table 4:

Overview of the uses of PFAS, the function of the PFAS in the uses and the properties of the employed PFAS that make them valuable for this application.

| Use category/subcategory | Function of PFAS | Properties of the PFAS employed |

|---|---|---|

| Industry branch | ||

| Aerospace | ||

| - Phosphate ester-based brake and hydraulic fluids | corrosion protection | altering the electrical potential at the metal surface |

| - Gyroscopes | flotation fluids in gyroscopes | ? |

| - Wire and cable | high-temperature endurance, fire resistance, and high-stress crack resistance | non-flammable polymers, stable |

| - Turbine-engine | use as lubricant | corrosion resistant, stable, non-reactive, operate at a wide temperature range |

| - Turbine-engine | use as elastomeric seals | operate at a wide temperature range |

| - Thermal control and radiator surfaces | reject waste heat | survival over a wide operating temperature range, low solar absorbance, high thermal emittance, and freedom from contamination by outgassing |

| - Coating | protect underlying polymers from atomic oxygen attack | non-reactive, very stable |

| - Propellant system | elastomers compatible to aggressive fuels and oxidizers | non-reactive, very stable |

| - Jet engine/satellite instrumentation | use as lubricant | long-term retention of viscosity, low volatility in vacuum and their fluidity at extremely low temperatures |

| Biotechnology | ||

| - Cell cultivation | supply of oxygen and other gases to microbial cells | great capacity to dissolve gases |

| - Ultrafiltration and microporous membranes | prevent bacterial growth | ? |

| Building and Construction | ||

| - Architectural membranes e.g. in roofs | resistance to weathering, dirt repellent, light | oleophobic and hydrophobic, low surface tension, beneficial weight-to-surface ratio |

| - Greenhouse | transparent to both UV and visible light, resistant to weathering, dirt repellent | oleophobic and hydrophobic, low surface tension |

| - Cement additive | reduce the shrinkage of cement | ? |

| - Cable and wire insulation, gaskets & hoses | high-temperature endurance, fire resistance, and high-stress crack resistance | non-flammable polymers, stable |

| Chemical industry | ||

| - Fluoropolymer processing aid | emulsify the monomers, increase the rate of polymerization, stabilize fluoropolymers | fluorinated part is able to dissolve monomers, non-fluorinated part is able to dissolve in water |

| - Production of chlorine and caustic soda (with asbestos diaphragms cells) | binder for the asbestos-fibre-based diaphragms | ? |

| - Production of chlorine and caustic soda (with fluorinated membranes) | stable membrane in strong oxidizing conditions and at high temperatures | stable, non-reactive |

| - Processing aids in the extrusion of high- and liner low-density polyethylene film | eliminate melt fracture and other flow-induced imperfections | low surface tension |

| - Tantalum, molybdenum, and niobium processing | cutting or drawing oil | non-reactive, stable |

| - Chemical reactions | inert reaction media (especially for gaseous reactants) | non-reactive, stable |

| - Polymer curing | medium for crosslinking of resins, elastomers and adhesives | ? |

| - Ionic liquids | raw materials for ionic liquids | ? |

| - Solvents | dissolve other substances | bipolar character of some of the PFAS |

| Electroplating (metal plating) | ||

| - Chrome plating | prevent the evaporation of chromium (VI) vapour | lower the surface tension of the electrolyte solution, very stable in strongly acidic and oxidizing conditions |

| - Nickel plating | non-foaming surfactant | low surface tension |

| - Nickel plating | increase the strength of the nickel electroplate by eliminating pinholes, cracks, and peeling | low surface tension |

| - Copper plating | prevent haze by regulating foam and improving stability | low surface tension |

| - Tin plating | help to produce a plate of uniform thickness | low surface tension |

| - Alkaline zinc and zinc alloy plating | ||

| - Deposition of fluoropolymer particles onto steel | supported by fluorinated surfactants | cationic and amphoteric fluorinated surfactants impart a positive charge to fluoropolymer particles which facilitates the electroplating of the fluoropolymer |

| Electronic industry | ||

| - Dielectric fluids | separation of high voltage components | high dielectric breakdown strength, non-flammable |

| - Testing of electronic devices and equipment | inert fluids for electronics testing | non-reactive |

| - Heat transfer fluids | cooling of electrical equipment | good heat conductivity |

| - Solvent systems and cleaning | form the basis of cleaning solutions | non-flammable, low surface tension |

| - Carrier fluid/lubricant deposition | dissolve and deposit lubricants on a range of substrates during the manufacturing of hard disk drives | ? |

| - Etching of piezoelectric ceramic filters | etching solution | acidic |

| Energy sector | ||

| - Solar collectors and photovoltaic cells | high vapour barrier, high transparency, great weatherability and dirt repellency | oleophobic and hydrophobic, low surface tension |

| - Photovoltaic cells | adhesives with PFAS hold mesh cathode in place | lower the surface tension of the adhesive |

| - Wind mill blades | coating | high weatherability |

| - Coal-based power plants | polymeric PFAS filter remove fly ash from the hot smoky discharge | stable, non-reactive |

| - Coal-based power plants | separation of carbon dioxide in flue gases | lower the surface tension of the aqueous solution |

| - Lithium batteries | binder for electrodes | almost no reactivity with the electrodes and electrolyte |

| - Lithium batteries | prevent thermal runaway reaction | good heat absorption of first layer and good heat conductivity of second layer |

| - Lithium batteries | improve the oxygen transport of lithium-air batteries | great capacity to dissolve gases |

| - Lithium batteries | electrolyte solvents for lithium-sulfur batteries | bipolar character of some of the PFAS |

| - Ion exchange membrane in vanadium redox batteries | polymeric PFAS are used as membranes | resistance to acidic environments and highly oxidizing species |

| - Zinc batteries | prevent formation of dendrites, hydrogen evolution and electrode corrosion due to adsorption onto the electrode surface | low surface tension, non-reactive |

| - Alkaline manganese batteries | MnO2 cathodes containing carbon black are treated with a fluorinated surfactant | ? |

| - Polymer electrolyte fuel cells | polymeric PFAS are used as membranes | ion conductance |

| - Power transformers | cooling liquid | good heat conductivity |

| - Conversion of heat to mechanical energy | heat transfer fluids | good heat conductivity |

| Food production | ||

| - Wineries and dairies | final filtration before bottling with polymeric PFAS | resist degradation |

| Machinery and equipment | ? | ? |

| Manufacture of metal products | ||

| - Manufacture of basic metals | ? | ? |

| - Manufacture of fabricated metal products | ? | ? |

| - Treatment of coating of metal surfaces | promote the flow of metal coatings, prevent cracks in the coating during drying | lower the surface tension of the coating |

| - Treatment of coating of metal surfaces | corrosion inhibitor on steel | non-reactive |

| - Etching of aluminium in alkali baths | improving the efficient life of the alkali baths | ? |

| - Phosphating process for aluminium | fluoride-containing phosphating solutions help to dissolve the oxide layer of the aluminium | ? |

| - Cleaning of metal surfaces | disperse scum, speed runoff of acid when metal is removed from the bath, increase the bath life | ? |

| - Water removal from processed parts | solvent displacement | low surface tension |

| - Electroless plating of copper | disperses the pitch fluoride in the plating solution | low surface tension |

| Mining | ||

| - Ore leaching in copper and gold mines | increase wetting of the sulfuric acid or cyanide that leaches the ore | low surface tension |

| - Ore leaching in copper and gold mines | acid mist suppressing agents | low surface tension |

| - Ore floating | create stable aqueous foams to separate the metal salts from soil | low surface tension |

| - Separation of uranium contained in sodium carbonate and/or sodium bicarbonate solutions by nitrogen floatation | improve the separation | ? |

| - Concentration of vanadium compounds | destruction of the mineral structure, increases the specific surface area and pore channel thus facilitating vanadium leaching | acidity |

| Nuclear industry | ||

| - Lubricants for valves and ultracentrifuge bearings in UF6 enrichment plants | PFAS are used as the lubricants | stable to aggressive gases |

| Oil & Gas industry | ||

| - Drilling fluid | foaming agent | low surface tension |

| - Drilling - insulating material for cable and wire | polymeric PFAS are used as insulating material | withstand high temperatures |

| - Chemical driven oil production | increase the effective permeability of the formation | low surface tension |

| - Chemical driven oil production | foaming agent for fracturing subterranean formations | low surface tension |

| - Chemical driven gas production | change low-permeability sandstone gas reservoir from strong hydrophilic to weak hydrophilic | hydrophobic and oleophobic properties |

| - Chemical driven gas production | eliminate reservoir capillary forces, dissolve partial solid, dis-assemble clogging, increase efficiency of displacing water with gas | lower surface tension of the material |

| - Oil and gas transport | lining of the pipes is made out of polymeric PFAS | non-reactive (corrosion resistant) |

| - Oil and gas transport | reduce the viscosity of crude oil for pumping from the borehole through crude oil-in-water emulsions | hydrophobic and oleophobic properties |

| - Oil and gas storage | aqueous layer with PFAS prevents evaporation loss | lower the surface tension of the aqueous solution |

| - Oil and gas storage | floating layer of cereal treated with PFAs prevents evaporation loss | low surface tension |

| - Oil containment (injection a chemical barrier into water) | prevents spreading of oils or gasoline on water | ? |

| - Oil and fuel filtration | polymeric PFAS are used as membranes | non-reactive (corrosion resistant) |

| Pharmaceutical industry | ||

| - Reaction vessels, stirrers, and other components | use of polymeric PFAS instead of stainless steel | ? |

| - Ultrapure water systems | polymeric PFAS are used as filter | low surface tension |

| - Packaging | polymeric PFAS form moisture barrier film | hydrophobic |

| - Manufacture of “microporous” particles | processing aid | ? |

| Photographic industry | ||

| - Processing solutions | antifoaming agent | lower the surface tension of the solution |

| - Processing solutions | prevent formation of air bubbles in the solution | lower the surface tension of the solution |

| - Photographic materials, such as films and papers | wetting agents, emulsion additives, stabilizers and antistatic agent | low surface tension, low dielectric constant |

| - Photographic materials, such as films and papers | prevent spot formation and control edge uniformity in multilayer coatings | low surface tension |

| - Paper and plates | anti-reflective agents | low refractive index |

| Production of plastic and rubber | ||

| - Separation of mould and moulded material | mould release agent | hydrophobic and oleophobic properties |

| - Separation of mould and moulded material | reduce imperfections in the moulded surface | low surface tension |

| - Foam blowing | foam blowing agent | low surface tension |

| - Polymer processing aid | increase processing efficiency and quality of polymeric compounds | lower the surface tension of the polymeric products |

| - Etching of plastic | wetting agent | low surface tension |

| - Production of rubber | antiblocking agent | low surface tension |

| - Fluoroelastomer formulation | additive in curatives | ? |

| Semiconductor industry | ||

| - Photoresist | make the photoresist soluble in water and give surface activity | hydrophobic and oleophobic properties |

| - Photoresist | increase the photosensitivity of the photoresist (photosensitizer) | ? |

| - Photoresist | photo-acid generator | able to generate strong acids |

| - Antireflective coating | provide low reflectivity | low refractive index |

| - Developer | facilitate the control of the development process | ? |

| - Etching | wetting agent | low surface tension |

| - Etching | reduce the reflection of the etching solution | low refractive index |

| - Etching | etching agent in dry etching | strong acids |