Abstract

Since December 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused serious mental health challenges and consequently the Turkish population has been adversely affected by the virus. The present study examined how meaning in life related to loneliness and the degree to which religious coping strategies mediated these relations. Participants were a sample of 872 adults (242 males and 360 females) drawn from general public in Turkey. Data were collected using Meaning in Life Questionnaire, UCLA Loneliness Scale, and the Religious Coping Measure. Meaning in life was associated with more positive religious coping and less negative religious coping and loneliness. Positive religious coping was associated with less loneliness, while negative religious coping was associated with more loneliness. Religious coping strategies mediated the impact of meaning in life on loneliness. These findings suggest that greater meaning in life may link with lesser loneliness due to, in part, an increased level of positive religious coping strategies and a decreased level of negative coping strategies.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Meaning in life, Positive religious coping, Negative religious coping, Loneliness

Introduction

The current pandemic of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) is exponentially spreading and affecting various aspects of daily routine. Disruptive impacts of COVID-19 have been observed in nearly 200 countries and territories, and almost every country is combating to prevent the spread of this unprecedented disease (Rubin and Wessely 2020; Yıldırım et al. 2020). This global public health crisis is of concern in terms of challenging psychological capacity of the general public to cope with the ongoing crisis (Wang et al. 2020). Since the emergence of COVID-19, the situation is worsening. As of 17 December 2020, the number of infected people was estimated to be nearly 72.9 million with more 1.6 million deaths worldwide (World Health Organization 2020). Turkey reported a total of 1955.680 COVID-19 cases and 17,364 deaths since the first announcement of a COVID-19 death on 17 March 2020 (Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health 2020). To control the spread of the virus, the Turkish government implemented a variety of COVID-19-related measures that required citizens to stay at home other than for necessities and urgencies. For example, Turkish government declared partial lockdown as a preventive measure against the virus as well as travel restrictions in-and-out of large cities (Yıldırım and Arslan 2020). This deadly disease is not only causing deaths of millions of people across the globe, but also leading to adverse psychological outcomes for infected people and healthy individuals. Although certain levels of anxiety and stress are natural responses to stressful situations (Roy et al. 2020), higher risk of infection, fear, and anxiety corresponding to the disease can cause negative mental health outcomes both at an individual and societal levels (Ahorsu et al. 2020; Arslan et al. 2020a, b, c, d; Burke and Arslan 2020; Yıldırım and Güler 2020).

Loneliness

Loneliness is an important public health issue (Groarke et al. 2020). Loneliness refers to an unpleasant feeling that occurs when one losses the quality and quantity of social or intimate relationships (Peplau and Perlman 1982). Experience of loneliness during the current health crisis can be prevalent due to imposed COVID-19 social and physical restrictions. According to one study, the prevalence of loneliness in UK public was 27% during lockdown, with one in four (24%) reported they had feelings of loneliness in the “previous two weeks” (Groarke et al. 2020). A higher level of loneliness was also reported among Norwegian adult population during the pandemic when compared with before the pandemic (Hoffart et al. 2020). Greater level of loneliness has potential to stimulate the prevalence of mood disorders, suicide and self-harm, and increase pre-existing mental health illnesses (Holmes et al. 2020). Loneliness is related to poor mental and physical health (Beutel et al. 2017) and religious coping, life satisfaction, and social media usage (Turan 2018). Furthermore, loneliness is found to be associated with worse subjective vitality and more rumination and coronavirus anxiety (Arslan et al. 2020a).

Researchers have highlighted the importance of identifying the predictors of loneliness in the face of adversity (Groarke et al. 2020). Various risk and protective factors were identified which increase loneliness (Kızılgeçit 2015). For example, in the study of Hoffart et al.’s (2020), rumination, health anxiety, and worry as well as being single and having a pre-existing psychiatric condition were significantly associated with more loneliness and loneliness was found to significantly positively predicted depression and anxiety over and above the all potential cofounders (e.g. age, gender, education level) and pre-existing psychiatric conditions. However, in that study, adaptive coping styles (e.g. doing new things at home and experience nature) were found to be negatively associated with loneliness. Another study (Groarke et al. 2020) found that younger age groups, being divorced or separated, greater emotion regulation difficulties, poor quality sleep because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and those who are meeting clinical criteria for depression, are at greater risk of loneliness and social isolation, while higher levels of perceived social support, being married, and living with a greater number of adults serve as protective factors for loneliness in times of health crisis.

Meaning in Life

Meaning in life is regarded as one of the fundamental ingredients of well-being and mental health, as its presence promotes individuals’ growth and recovery (Lopez and Snyder 2011; Steger et al. 2006). Meaning in life is conceptualized differently in the relevant literature. According to Wong (1989), meaning in life constitutes three interrelated components: cognitive, affective, and motivational. Cognitive component refers to one’s thoughts and beliefs regarding everyday life situations and experiences; affective component represents one’s feelings and emotions about the worthiness and ultimate goals of life; and motivational component reflects to the pursuit of personal goals. Meaningful living is also viewed as a balanced understanding and appreciation of the good life, encompassing the dynamic interaction between positives and negatives, meaning-cantered, and cultural values (Wong 2012, 2016). Furthermore, Steger et al. (2006) defined meaning in life as including two dimensions: presence of meaning and search for meaning. While the presence of meaning in life is positively related to satisfaction with life and positive emotions, search for meaning in life is positively associated with depression, neuroticism, and negative emotions (Steger et al. 2006).

Previous research has documented that the experience of feeling that one has significance and purpose in life, is significantly associated with variety of mental health outcomes for individuals coping with a range of different health crises and illnesses (Fleer et al. 2006; Park et al. 2008; Simmons et al. 2000). A sense of meaning in life is positively related to higher levels of positive emotions (King et al. 2006), adaptive religious coping strategies (Park et al. 2008), and promotion of positive mental health outcomes (Arslan et al. 2020b). Lack of meaning in life was positively associated with health anxiety (Yek et al. 2017), and loneliness (Cole et al. 2015). COVID-19 pandemic-specific evidence suggests that meaning in life is a critical psychological factor in promotion of complete mental health. Arslan et al. (2020a) reported that meaning in life is significantly positively associated with satisfaction with life, positive affect, emotional well-being, social well-being, and psychological well-being and significantly negatively related to negative affect, somatization, depression, and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. This suggests that meaning in life plays an important role in increasing positive mental health outcomes and reducing negative mental health outcomes.

Religious Coping Strategies as Mediators

In times of health crisis, people use various effective and suitable strategies to cope with negative outcomes, to protect their psychological health and distance from adversity derived from emergency situations (Cao et al. 2020). Religious coping is one of the coping styles when dealing with adversity (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005). Religious coping refers to the ways of understanding and coping with adverse life events that are associated the sacred (Pargament and Abu Raiya 2007). Religious coping is typically classified into two: positive religious coping and negative religious coping (Pargament and Abu Raiya 2007; Pargament et al. 2000). Positive religious coping represents a positive and adaptive involvement in religiosity, in which religion is viewed to assist and equip the people to understand the world, and allow the people to respond effectively in the appraisal and dealing with stressful situations in the long run (Lewis et al. 2005). Negative religious coping refers to “underlying spiritual tensions and struggles with oneself, with others, and with the divine” (Pargament et al. 2011).

The findings of meta-analysis underscore the vital role of religious coping in psychological adjustment to stress (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005). Previous studies have demonstrated that positive religious coping is positively related to psychological well-being (Lewis et al. 2005), psychological, physical, and spiritual adjustments (Pargament et al. 2004), and externalizing behaviours (French et al. 2020). Negative religious coping was found to be related to poor quality of life such as worse physical functioning, role physical, vitality, social functioning, and mental health over and above the sociodemographic, clinical, and anxiety and depression factors (Taheri-Kharameh et al. 2016). In the context of current pandemic, higher levels of positive religious coping, intrinsic religiosity, and trust in God significantly associated with lower levels of stress and more positive impact of COVID-19, whereas higher levels of negative religious coping and mistrust in God were related to greater stress and negative impacts (Pirutinsky et al. 2020). Furthermore, higher use of religious and spiritual beliefs during the COVID-19 pandemic was related to better mental health outcomes including hope and spiritual growth (Lucchetti et al. 2020). There is also a close link between religious coping strategies and loneliness, for example, in a recent study, positive religious coping was found to be negatively associated with loneliness both concurrently and longitudinally (French et al. 2020). Another study reported significant effects of religious coping on loneliness and depression (Warner et al. 2019).

Present Study

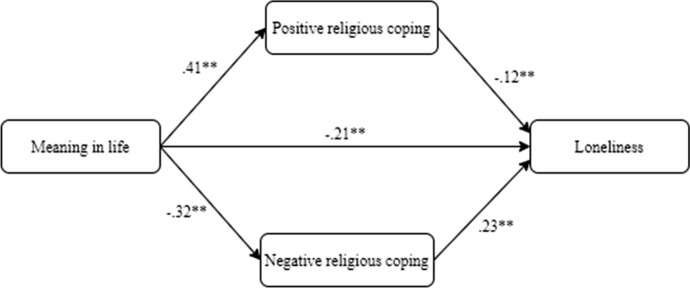

There is paucity of literature on the influence of meaning in life on loneliness when considering the role of religious coping strategies in the face of adversity. This is an important to be addressed to better understand the links between them. Building on existing research, the main purpose of this study was to examine the degree to which positive religious coping and negative religious coping serve to mediate the relations of meaning in life with loneliness. We hypothesised that (1) meaning in life would positively predict positive religious coping and negatively predict negative religious coping and loneliness, (2) positive religious coping and negative religious coping would, respectively, negatively and positively predict loneliness, and (3) positive and negative religious copings would mediate the relationship between meaning in life and loneliness. The proposed structural model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed structural model depicting the standardized associations between variables (**p < 0.001)

Methods

Participants

Participants of this study were 872 Turkish adults recruited from various socioeconomic background using social networking sites. Of the participants, 242 (27.8%) were males and 360 (72.2%) were females. Most importantly, of the total sample, 111 (12.73%) were under 20 years old who have been ordered to stay-at-home unless it is for essential purposes following announcement of COVID-19 restrictions in Turkey. Participants were mostly single (60.6%), university/college graduate (59.3%), earning income over 5.000 Turkish lira (34.4%), and with no history of chronic disease (85.7%). Nearly 42% of the participants reported that people aged 60 years and older are high-risk groups for COVID-19. Detailed description of participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 872)

| Variable | Level | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 242 | 27.75 |

| Female | 630 | 72.25 | |

| Age | 18–20 years | 111 | 12.73 |

| 20–29 years | 439 | 50.34 | |

| 30–39 years | 113 | 12.96 | |

| 40–49 years | 111 | 12.73 | |

| 50–59 years | 66 | 7.57 | |

| 59 + years | 32 | 3.67 | |

| Marital status | Single | 528 | 60.55 |

| Married | 319 | 36.58 | |

| Widowed | 11 | 1.26 | |

| Divorced | 14 | 1.61 | |

| Education level | Primary or secondary graduate | 53 | 6.08 |

| High school graduate | 130 | 14.91 | |

| College or university graduate | 517 | 59.29 | |

| Post-graduate | 172 | 19.72 | |

| Monthly income | 0–1000 TRY | 83 | 9.52 |

| 1000–2000 TRY | 101 | 11.58 | |

| 2000–3000 TRY | 169 | 19.38 | |

| 3000–5000 TRY | 219 | 25.11 | |

| 5000 TRY and above | 300 | 34.40 | |

| History of chronic diseases | No | 747 | 85.67 |

| Yes | 125 | 14.33 | |

| People aged 65 years and older | 367 | 41.5 | |

| High-risk groups for COVID-19 | People aged between 21 and 64 years | 212 | 24.0 |

| People aged between 13 and 20 years | 156 | 17.6 | |

| Children aged between 0 and 12 years | 149 | 16.9 |

Measures

Meaning in Life (Steger et al. 2006)

Meaning in life was measured with the Presence of Meaning Scale that comprises five items that are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true to 7 = very true). A sample item is “I understand my life’s meaning.” The scale produces a minimum score of 5 and a maximum score of 35, and higher scores refer to greater sense of meaning in life. Turkish version of the scale was validated by Boyraz et al. (2013). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.84.

Religious Coping (Ayten 2012)

Religious coping was assessed using the Religious Coping Scale. This scale, developed by Ayten (2012), was mainly created by using the RECOPE developed by Pargament et al. (2000). It is 33 items including nine components, of which 6 components (e.g. Seeking Religious Direction, Religious Supplication, Religious Affiliation, Religious Conversion, Reappraisal Favourably) refer to positive coping strategies and 3 components (e.g. Spiritual Discontent, Interpersonal Religious Discontent) refer to negative religious coping. Sample items include “I try to be close to God” for positive religious coping and “I think God has abandoned me” for negative religious coping. A total score can be obtained by summing items on the respective components, with higher scores indicating higher levels of religious coping on the respective components. Psychometric properties of the scale in Turkish were evaluated by Ayten (2012) who provided satisfactory evidence of reliability and validity. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 for positive religious coping and 0.63 for negative religious coping.

Loneliness (Russell et al. 1980)

Loneliness was assessed using the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA). The R-UCLA includes 20 items, and each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = never, 4 = often). Sample item includes “There are people I feel close to” (positive item) and “I feel isolated from others” (negative item). After reversing negatively worded items, the scale produces a minimum of 20 and a maximum of 80, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. The R-UCLA was translated into Turkish by Demir (1989) who provided good evidence of reliability and validity for the scale. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was estimated as 0.75.

Procedure

Approval for the study was received from the second author’s institutional review board of the university where the study was carried out prior to data collection. The study conducted online, and participants were recruited from various social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. All participants were provided an informed consent form that included the aim of the study, confidentiality and anonymity of personal information, and the right to withdraw from the research at any time. No momentary compensation was paid to participants. The data were collected between 24 April and 3 May 2020.

Data Analysis

Distribution of variables was examined through skewness and kurtosis statistics where ± 1 = “very good”, ± 2 = “acceptable, skewness > 2 and kurtosis > 7 = “concern” (Curran et al. 1996). Descriptive statistics, frequency statistics, and internal consistency reliability estimate were reported prior to the main analysis. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to explore the associations between the variables of this study. The mediation model was tested using PROCESS for SPSS v3.5 (Hayes 2013) via Model 4. Bootstrapping method with 10.000 resampling was used to investigate the significance of the indirect effects. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 for Windows.

Results

Prior to assessing the mediation model, several preliminary analyses were performed. First, we explored distribution of the main variables using skewness and kurtosis statistics. The results showed that none of the variables were above 2, suggesting that all variables appeared approximately normally distributed at “very good” or “acceptable” levels. Second, we explored intercorrelations among the variables. As reported in Table 2, meaning in life was significantly positively correlated with positive religious coping (r = 0.41, p < 0.01) and significantly negatively correlated with negative religious coping (r = − 0.32, p < 0.01) and loneliness (r = − 0.33, p < 0.01). Positive religious coping was significantly negatively correlated with loneliness (r = − 0.26, p < 0.01), while negative religious coping was significantly positively correlated with loneliness (r = 0.33, p < 0.01). There was a significant negative correlation between positive religious coping and negative religious coping (r = − 0.22, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability, and correlation analysis for the study variables

| Variable | Descriptive statistics | Reliability | Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. Meaning in life | 5 | 35 | 10.96 | 5.66 | 1.16 | 1.29 | .83 | – | .41** | − 0.32** | − 0.33** |

| 2. Positive religious coping | 25 | 89 | 41.28 | 11.96 | 1.27 | 1.65 | .90 | – | − 0.22** | − 0.26** | |

| 3. Negative religious coping | 8 | 40 | 31.65 | 4.62 | − 0.78 | 1.06 | .63 | – | .33** | ||

| 4. Loneliness | 32 | 74 | 57.94 | 8.26 | − 0.43 | − 0.40 | .75 | – | |||

**p < 0.001

In addition to preliminary analyses, mediation analysis was carried out to examine how positive religious coping and negative religious coping explained the association between meaning in life and loneliness. Findings demonstrated that meaning in life had significant direct effects on positive religious coping (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and negative religious coping (β = − 0.32, p < 0.001), explaining 17% of the variance in positive religious coping and 11% of the variance in negative religious coping. Further, meaning in life had a significant direct effect on loneliness (β = − 0.21, p < 0.001). Positive religious coping (β = − 0.12, p < 0.001) and negative religious coping (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) had significant direct effects on loneliness. Collectively, these variables accounted for 18% of the variance in loneliness. Moreover, the indirect effect of meaning in life on loneliness through positive religious coping and negative religious coping was significant. The results are presented in Tables 3, 4, and Fig. 1. These results suggest that religious coping strategies are useful mechanism that may explain the association of meaning in life with loneliness in general public.

Table 3.

Unstandardized coefficients for the mediation model

| Antecedent | Consequent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Positive religious coping) | |||||

| Coeff | SE | t | p | ||

| X (meaning in life) | a1 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 13.17 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | iM1 | 31.85 | 0.81 | 39.47 | < 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.17 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F = 173.20; p < 0.001 | |||||

| M2 (Negative religious coping) | |||||

| X (Meaning in life) | a2 | − 0.27 | 0.03 | –10.10 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | iM2 | 34.55 | 0.32 | 106.91 | < 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.11 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F = 102.0; p < 0.001 | |||||

| Y (Loneliness) | |||||

| X (Meaning in life) | c′ | − 0.31 | 0.05 | −6.04 | < 0.001 |

| M1 (Positive religious coping) | b1 | − 0.08 | 0.02 | − 3.54 | < 0.001 |

| M2 (Negative religious coping) | b2 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 7.02 | < 0.001 |

| Constant | iy | 51.73 | 2.30 | 22.53 | < 0.001 |

| R2 = 0.18 | |||||

| F = 61.93; p < 0.001 | |||||

SE standard error, Coeff unstandardized coefficient, X independent variable, M mediator variable, Y dependent variable

Table 4.

Completely standardized indirect effect of meaning in life on loneliness

| Path | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effect | − 0.12 | 0.02 | − 0.17 | − 0.08 |

| Meaning in life → positive religious coping → loneliness | − 0.05 | 0.02 | − 0.08 | − 0.02 |

| Meaning in life → negative religious coping → loneliness | − 0.07 | 0.01 | − 0.10 | − 0.05 |

Number of bootstrap samples for percentile bootstrap confidence intervals: 10,000

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected the mental health of people across the globe. With the emergence of pandemic, various research has been conducted to investigate the positive and negative mental health outcomes. The current study focused on the process that helps to elucidate the relations of meaning in life with loneliness. To the best of our knowledge, during the current pandemic, this is the first study which has explained the process through which religious coping is considered. The results of this study advance our understanding of the links between meaning in life and loneliness, particularly highlighting the role of religious coping strategies as mediators.

The results of this study showed a significant direct effect of meaning in life on religious coping and loneliness. This research has provided more evidence in support of the links between meaning in life, religious coping, and loneliness. These results are consistent with previous evidence indicating the association between meaning in life—religious coping (Dunn and O'Brien 2009) and meaning in life—loneliness (Aliakbari Dehkordi et al. 2015). Meaning in life has an inverse association with negative religious coping (Yek et al. 2017) and loneliness and a positive association with positive religious coping (Park et al. 2008). This suggests that meaning in life allows people to regulate the loneliness. As such, it supports coping and reduces loneliness, particularly in the face of adverse life situations which have potential to cause serious mental health consequences. Coping strategies have a wide range of short- and long-term effects on people’s development and well-being. Furthermore, people with maladaptive coping strategies may have higher levels of negative mental health outcomes such as internalizing and externalizing problems, while adaptive coping strategies may mitigate the negative effects of psychological factors on mental health and protect people’s mental health (Arslan 2017).

The study findings indicated that the effect of meaning in life on loneliness is mediated by positive and negative religious coping. Religious coping predicts loneliness (Warner et al. 2019). These findings confirm the negative indirect effect of meaning in life on loneliness. This suggests that loneliness further mitigates when meaning in life leads to increased positive religious coping and decreased negative religious coping. Indeed, recent research has reported high levels of loneliness within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Arslan 2020, c; Arslan et al. 2020a). In times of health crisis, the experience of loneliness that individuals may feel either alone or in the presence of others may be exacerbated. Dealing with the symptoms of loneliness is a matter of high concern and cannot be disregarded. Neglecting such an important issue and failure to develop and implement timely measures to address loneliness might result in various irreversible mental health consequences, not only during COVID-19 pandemic, but also in post pandemic times. Currently, there is evidence to support this argument. A study conducted on US young adults during COVID-19 pandemic documented evidence supporting direct impacts of loneliness and social connectedness on anxiety, depression, alcohol use, and drug use alongside indirect impacts of loneliness and social connectedness on alcohol and drug use via anxiety and depression (Horigian et al. 2020). In the presence of meaning in life and positive religious coping, loneliness resulting from the negative religious coping can be reduced and even further negative mental health consequences might be preventable. In adverse life situations, meaning in life functions as a contributing factor in promotion of complete mental health that represents the presence of positive human functioning (e.g. subjective and psychological well-being) and the absence of psychopathological symptoms (e.g. depression and anxiety) (Arslan et al. 2020b). People with high senses of meaning in life (Arslan et al. 2020a, b, c, d) and religious coping (Ano and Vasconcelles 2005) can effectively cope with stressors in difficult times. Therefore, it is possible that people have more positive outcomes and less negative outcomes in the face of adversity.

Contributions and Limitations

The findings of this contribute to the understanding of the associations between meaning in life, religious coping, and loneliness during traumatic and difficult conditions. Adaptive religious coping in conjunction with meaning in life acts as a factor that mitigates the effect of loneliness, while maladaptive religious coping serves as a factor that exacerbates the effect of loneliness. A stress and coping model (Folkman 2010; Lazarus and Folkman 1984) underscores the effects of stressors on mental health consequences and elucidates the interlinks between the resources, adaptation strategies, and any mediating roles on loneliness and depressive symptoms (Warner et al. 2019). The study findings are useful in terms of focusing on building strengths (e.g. meaning in life and coping) and promoting positive mental health. The findings revealed that adaptive religious coping strategies could serve as a buffer for people experiencing the symptoms of loneliness during COVID-19 pandemic. Put differently, adaptive religious coping can preclude the development of negative mental health outcomes like loneliness in the context of adverse life conditions. Meaning is particularly important for the promotion of adaptive religious coping strategies and prevention of maladaptive religious coping strategies which play key roles in explaining loneliness. As such, efforts aimed at reducing loneliness could stress the roles of meaning in life and religious coping strategies. Moreover, in the context of current pandemic, it is vital to consider the roles of meaning in life and religious coping strategies in developing preventive behaviours in response to stressors and accomplishment of positive mental health at national and global levels.

The findings of this study should be considered in light of several limitations, each of which present directions for subsequent research. First, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, a causal conclusion among the variables cannot be drawn. As such, future research should investigate how the employed variables relate together over time. Second, the sample predominantly comprised of females, single, and university/college graduate. Future work should replicate our findings with more diverse samples to increase the generalizability of emerging findings. Similarly, there is a need to replicate the current findings across various cultures to investigate similarities and differences among the research outcomes.

Conclusion

The current study has contributed to the knowledge on the association between meaning in life and loneliness by investigating the roles of religious coping strategies as mediators in that relationships during COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings underscored the need to improve positive religious coping stategies and mitigate negative coping strategies in order to understand why meaning in life reduces loneliness. Further, positive psycho-religious interventions are needed for reducing loneliness if progress is to be made in fostering meaning in life among Turkish adults.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Atatürk University, Scientific Research Projects, through a grant to the second author. Project No. SBA-2020-8594. We would like to thank all participants who contributed to this study.

Author’s Contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data analysis was conducted by MY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MY. Material preparation and data collection were performed by MK, İS, FK, YA, AD, MEV, NNB, and MÇ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethic approval has been obtained before conducting the research.

Informed Consent

Consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: The error in affiliation link for the co-author has been corrected.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

1/30/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s10943-021-01184-y

References

- Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliakbari Dehkordi M, Peymanfar E, Mohtashami T, Borjali A. The comparison of different levels of religious attitude on sense of meaning, loneliness and happiness in life of elderly persons under cover of social welfare organisation of Urmia City. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2015;9(4):297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ano GG, Vasconcelles EB. Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(4):461–480. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, coping strategies, and mental health problems: A brief and effective measure of psychological maltreatment in adolescents. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2017;68:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G. (2020). Loneliness, college belongingness, subjective vitality, and psychological adjustment during coronavirus pandemic: Development of the College Belongingness Questionnaire. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 1–15. https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/JPPW/article/view/240

- Arslan G, Yıldırım M, Aytaç M. Subjective vitality and loneliness explain how coronavirus anxiety increases rumination among college students. Death Studies. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1824204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G, Yıldırım M, Karataş Z, Kabasakal Z, Kılınç M. Meaningful living to promote complete mental health among university students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00416-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G, Yıldırım M, Wong PTP. Meaningful living, resilience, affective balance, and psychological health problems during COVID-19. Current Psychology. 2020;72:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G, Yıldırım M, Tanhan A, Buluş M, Allen KA. Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: Psychometric properties of the Coronavirus Stress Measure. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayten A. Tanrı’ya Sığınmak. İstanbul: İz Yayıncılık; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, Reiner I, Jünger C, Michal M, Tibubos AN. Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyraz G, Lightsey OR, Jr, Can A. The Turkish version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the measurement invariance across Turkish and American adult samples. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2013;95(4):423–431. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.765882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, Arslan G. Positive education and school psychology during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Positive School Psychology. 2020;4(2):137–139. doi: 10.47602/jpsp.v4i2.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Levine ME, Arevalo JM, Ma J, Weir DR, Crimmins EM. Loneliness, eudaimonia, and the human conserved transcriptional response to adversity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1996;1(1):16–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir A. UCLA yalnızlık ölçeğinin geçerlik ve güvenirliği. Psikoloji Dergisi. 1989;7(23):14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MG, O'Brien KM. Psychological health and meaning in life: Stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009;31(2):204–227. doi: 10.1177/0739986309334799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleer J, Hoekstra HJ, Sleijfer DT, Tuinman MA, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. The role of meaning in the prediction of psychosocial well-being of testicular cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research. 2006;15:705–717. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-3569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC, Purwono U, Shen M. Religiosity and positive religious coping as predictors of Indonesian Muslim adolescents’ externalizing behavior and loneliness. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2020 doi: 10.1037/rel0000300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. The Oxford handbook of stress and coping. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Groarke JM, Berry E, Graham-Wisener L, McKenna-Plumley PE, McGlinchey E, Armour C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0239698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process: A regression-based approach. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart A, Johnson SU, Ebrahimi OV. Loneliness and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk factors and associations with psychopathology. PsyArxiv. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/j9e4q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ford T. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horigian VE, Schmidt RD, Feaster DJ. Loneliness, mental health, and substance use among US young adults during COVID-19. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2020 doi: 10.1080/02791072.2020.1836435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Hicks JA, Krull J, Del Gaiso AK. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:179–196. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kızılgeçit M. Yalnızlık Umutsuzluk Ve Dindarlık Üzerine Psiko Sosyal Bir Çalışma. Ankara: Gece Kitaplığı Yayınları; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CA, Maltby J, Day L. Religious orientation, religious coping and happiness among UK adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38(5):1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SJ, Snyder CR. The Oxford handbook of positive psychology. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetti G, Góes LG, Amaral SG, Ganadjian GT, Andrade I, de Araújo Almeida PO, Manso MEG. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020970996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Abu Raiya HA. A decade of research on the psychology of religion and coping: Things we assumed and lessons we learned. Psyke and Logos. 2007;28:742–766. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(6):713–730. doi: 10.1177/1359105304045366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56(4):519–543. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K, Feuille M, Burdzy D. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions. 2011;2:51–76. doi: 10.3390/rel2010051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Malone MR, Suresh DP, Bliss D, Rosen RI. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplau LA, Perlman D. Perspectives on loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. London: Wiley; 1982. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pirutinsky S, Cherniak AD, Rosmarin DH. COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health. 2020;59(5):2288–2301. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. (2020). Republic of Turkey Ministry of HealthDaily coronavirus table of Turkey. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/?lang=en-US.

- Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, Sharma N, Verma SK, Kaushal V. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;51:102083. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;39(3):472–480. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons Z, Bremer BA, Robbins RA, Walsh SM, Fischer S. Quality of life in ALS depends on factors other than strength and physical function. American Academy of Neurology. 2000;55:388–392. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri-Kharameh Z, Zamanian H, Montazeri A, Asgarian A, Esbiri R. Negative religious coping, positive religious coping, and quality of life among hemodialysis patients. Nephro-urology Monthly. 2016;8(6):e38009. doi: 10.5812/numonthly.38009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan Y. Yalnızlıkla başa çıkma: Yalnızlık, dini başa çıkma, dindarlık, hayat memnuniyeti ve sosyal medya kullanımı. Cumhuriyet İlahiyat Dergisi. 2018;22(1):395–434. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, Ho RC. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner CB, Roberts AR, Jeanblanc AB, Adams KB. Coping resources, loneliness, and depressive symptoms of older women with chronic illness. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2019;38(3):295–322. doi: 10.1177/0733464816687218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PTP. Personal meaning and successful aging. Canadian Psychology. 1989;30(3):516–525. doi: 10.1037/h0079829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong PTP. The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wong PTP. Meaning centered positive group intervention. In: Russo-Netzer P, Schulenberg S, Batthyány A, editors. Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy. New York, NY: Springer; 2016. pp. 423–445. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

- Yek MH, Olendzki N, Kekecs Z, Patterson V, Elkins G. Presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life and relationship to health anxiety. Psychological Reports. 2017;120(3):383–390. doi: 10.1177/0033294117697084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M, Arslan G. Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Current Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M, Güler A. Positivity explains how COVID-19 perceived risk increases death distress and reduces happiness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;168:110347. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım M, Geçer E, Akgül Ö. The impacts of vulnerability, perceived risk, and fear on preventive behaviours against COVID-19. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.177689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]