Abstract

Objective: The aim of this meta-synthesis was to synthesize and interpret the available qualitative studies to increase our understanding and extend knowledge about how women with endometriosis experience health care encounters.

Methods: The literature review was carried out using CINAHL, Psychinfo, Academic Search Premier, PubMed, and Scopus, from 2000 to 2018, and was limited to articles in English. Articles were only included if they reported original relevant research on endometriosis and women experiences.

Results: The meta-synthesis was based on 14 relevant studies. They included 370 women with diagnosed endometriosis, 16–78 years of age. Three fusions were identified and interpreted in this meta-synthesis. The first was: Insufficiency knowledge, where the physicians could judge the symptoms to be normal menstruation without examining whether there were other underlying causes. The second fusion was Trivializing—just a women's issue, where the physicians thought that the symptoms were part of being a woman, and women's' discomfort was trivialized or completely disregarded. The third fusion was Competency promotes health, where the insufficiency of knowledge became a minor concern if women had a supportive relationship with their physician and the physician showed interest in their problems.

Conclusions: Women with endometriosis experience that they are treated with ignorance regarding endometriosis in nonspecialized care. They experience delays in both their diagnosis and treatment and feel that health care professionals do not take their problems seriously. In addition, it appears that increased expertise and improved attitudes among health care professionals could improve the life situation of women with endometriosis.

Keywords: endometriosis, health care encounter, hermeneutics, meta-synthesis, qualitative research, women's experiences

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory, and estrogen-dependent gynecological disease associated with pain and infertility that affects women of reproductive age.1 Endometriosis has been here throughout the ages and strikes women worldwide.2 It is estimated that 176 million women worldwide may be living with endometriosis. Approximately 10% of women of reproductive age are affected.3 Endometriosis occurs when endometrial cells, which normally line the uterus, grow outside the uterus. This tissue implants in, and forms lesions on, other organs, including the ovaries, bowel, bladder, and the Pouch of Douglas.4

Gynecological symptoms of endometriosis include, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, bleeding, fatigue, and, in some cases, urological or gastrointestinal symptoms (such as dysuria, dyschezia). Compromised fertility or infertility are other symptoms associated with endometriosis.5,6

Laparoscopy is the most common procedure used to diagnose endometriosis, ideally confirmed by histology.7,8 Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis may have several causes such as false diagnosis and normalization of symptoms,9 but delay often occur because the gold standard for disease confirmation is using laparoscopy and histology. Such delays can adversely affect reproductive potential and functional outcomes.8 Endometriosis affects a woman's life considerably. A recent systematic review,10 found only 18 qualitative articles on endometriosis. This review showed that endometriosis affected all areas of a woman's life; sex life, social life, and work life, and medical experiences, symptom, and infertility are in some way intertwined and added distress to life.10 This review also pointed out that there were few studies on women's experiences of endometriosis-associated infertility and of the impact of reduced social participation on perceived support and emotional wellbeing. There are also few systematic reviews or meta-analysis that address psychological care for women with endometriosis.11,12 These reviews focus on treatment or interventions that may be promising in reducing endometriosis pain, anxiety, depression, stress, and fatigue. Another area where there is little, or no research is how women with endometriosis experience health care encounters. Such knowledge is important for providing high-quality care. Therefore, the objective of this meta-synthesis was to synthesize and interpret the available qualitative studies to increase our understanding and extend knowledge about how women with endometriosis experience health care encounters.

Materials and Methods

This article is an update of a qualitative meta-synthesis conducted by the Swedish Council for Health Technology Assessment as part of a report on the diagnosis and treatment of Endometriosis.13 This is a qualitative meta-synthesis, that is, an interpretive integration of qualitative findings that offers more than the sum of the individual data sets because it provides an innovative interpretation of the separate findings.14–16 The new findings and conclusions are derived from examining all the articles in a sample as a collective group, presenting interpretations that are representative since it is based on several articles.14 Qualitative meta-synthesis allows for a broader approach to evidence-based research and practice by expanding how knowledge can be generated and used in the researched area.17,18 A meta-synthesis is the outcome of a metadata method. It is a distinct approach to new inquiry based on critical interpretation of existing qualitative studies.16 “It creates a mechanism by which the nature of interpretation is exposed and the meanings that extend well below those presented in the available body of knowledge can be generated. As such, it offers a critical, historical and theoretical analytic approach to making sense of qualitative knowledge.”16, p2 The review/meta-synthesis was not registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), since the data were already extracted, and the analysis was conducted.

Sample

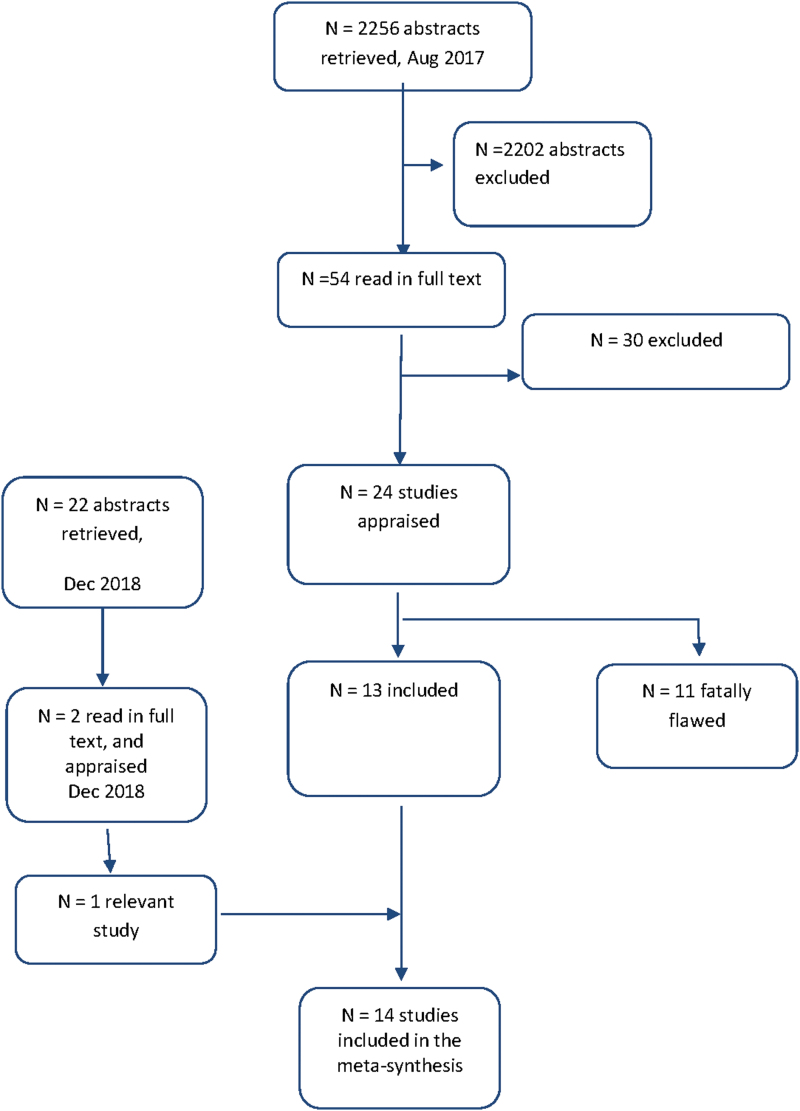

Relevant qualitative research studies were retrieved on two occasions. A comprehensive search in the bibliographic databases CINAHL, Psych info, Academic Search Premier, PubMed, and Scopus was conducted on August 30, 2017. The articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) have a focus on women with endometriosis; (2) make explicit references to the use of qualitative research/studies or mixed methods, where the qualitative findings were reported separately; (3) have a focus on women's perspectives and experiences of living with endometriosis and how they experienced the encounters with health care; (4) published from 2000 to August 2017 and written in English. Exclusion criteria were quantitative research and literature reviews. An additional, selective, search in PubMed was conducted in December 2018, using the search terms endometriosis, women's experiences, and health care encounters. As shown in the flowchart in Figure 1, 24 studies were retrieved for consideration. A complementary search identical with 2018 was performed in December 2019. No more studies were retrieved.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of the literature search process.

Meta-method

The meta-method requires an analysis of the rigor and soundness of the research methods used in each of the studies reviewed to determine the appropriateness of the methods.15 The meta-method procedure had two steps. First, the studies were evaluated, with an emphasis on research design and data collection methods, to ensure that the article met the study's inclusion criteria.16 Of the 54 articles, 30 were excluded. One of these evaluated a training program and used a survey with open-ended questions. This article was retained for validation of our results. Second, the studies were appraised; incorporating the reading guide for both an individual appraisal of each possible study considered for inclusion, together with comparative appraisal across studies. Key features of the studies were summarized, and a cross-study display was developed presenting the 14 articles selected for the study (Table 1). There is a large amount of data in each study, so the recommendation is that 10–12 studies is an ideal number for a meta-synthesis.17 The studies represented the following disciplines: sociology, medicine, nursing, and physiotherapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Showing primary research features in articles included in analysis

| Aim Underpinning theory | Setting Participants | Sampling | Data collection | Analysis | Measures to support trustworthyness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballard et al.23 United Kingdom |

Aim of study To investigate the reasons women experience delays in diagnosis of endometriosis and the impact of this Underpinning theory Not described |

Setting Hospital pelvic pain clinic Participants 32 women Age: 16-47 years; (median 32) Years with pelvic pain: median 15 years |

Sampling Not described Inclusion criteria confirmed or suspected endometriosis |

Data collection Semi structured, face-to-face interviews, most often conducted in the home of the interviewee; 60-120 minutes Interviewer The author, social scientist |

Analysis Thematic analysis where experiences and beliefs that women expressed were interpreted for key themes. Only women with confirmed endometriosis were included in the analysis Analysts Initial analysis by the author (a social scientist), refined after discussions with a pelvic pain specialist (gyneacologist) and a social scientist |

Development of the coding frame and the initial analysis was carried out by a social scientist. The findings were then discussed with a consultant gynecologist and specialist in pelvic pain, and a social scientist. Based on these discussions, the analysis was further refined |

| Denny & Mann24 United Kingdom |

Aims of study Explore experiences from primary care. Reanalysis of data from Denny 2004 Underpinning theory ? |

Setting A clinic for endometriosis at a specialist women's hospital Participants 30 women Age: 19 - 44 years, (mean 31) Diagnostic delay: mean 5,65 years (0-18 years) |

Sampling Purposeful. Inclusion criteria Laparoscopically verified endometriosis |

Data collection Semi structured interview based on a story-telling approach, in their home or at the clinic; 30-50 minutes Probing for primary care if not mentioned spontaneously Interviewer The author, a social scientist |

Analysis Thematic analysis (Bryman) Analysts The two authors, one social scientist and one gynecologist |

Respondent validation of the themes Although there was no methodological triangulation, rigour was achieved in analysis as both authors and the women who participated in the study agreed the analytical themes as relevant and arising from the data. |

| Denny25 United Kingdom |

Aim of study Explore women's experience of living with endometriosis. One-year follow- up Underpinning theory Feminist approach |

Setting A clinic for endometriosis at a specialist women's hospital Participants Interviews: 27 women; Age: 19 - 44 years, (mean 31) Diary: 19 of these women |

Sampling Purposeful (interviews) Not reported (diaries) |

Data collection Semi structured interview based on a story-telling approach, in their home or at the clinic; 30-50 minutes Diary on endometriosis for one menstrual cycle; completed by 7 women Interviewer The author, a social scientist |

Analysis Narrative analysis Analysts Only one author, social scientist |

Respondent validation of the themes the women who participated in the study agreed the analytical themes as relevant and arising from the data. |

| Facchin et al.27 Italy |

Aim of study Provide a broader understanding on how endometriosis affects psychological health Underpinning theory Grounded theory |

Setting Tertiary level referral center for treatment of endometriosis Participants 74 women Age: 24 -50 years |

Sampling Theoretical sampling Consecutively recruited Inclusion criteria Self-referred for treatment, surgically verified diagnosis, different forms of endometriosis |

Data collection Face- to face interviews with a story-telling approach, conducted at the hospital Time: average 45 minutes Interviewer Trained psychologists including the first author |

Analysis Constant comparative (Corbin & Strauss) Analysts Three, working independently |

All emergent themes were continuously discussed in the research team Findings were presented to expert gynecologists and female members of a non-for-profit endometriosis association Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached |

| Gilmour et al.28 New Zealand |

Aim of study Explore the perceptions of living with endometriosis Underpinning theory Feminist research principles |

Setting Local endometriosis support group Participants 18 women Age: 16 to 45 years Diagnostic delay: 5-10 years |

Sampling Interested women from the support group contacted the researchers after information about the project |

Data collection Unstructured, interactive interview Interviewer Not described, but familiar with endometriosis and knowledgeable how to handle emotional reactions during the interview |

Analysis Thematic analysis Analysts The authors, with a nursing background and working as researchers at a department for health and social services |

Continuous collaboration with the support group Emerging themes were presented at two meetings and verified by the participants |

| Grundström et al.31 Sweden |

Aim of study Identify and describe the experiences of health care encounters for women with endometriosis Underpinning theory phenomenology |

Setting A university and a central hospital clinic Participants 9 women consecutively invited by three gynecologists in charge of their endometriosis treatment Age: 23-55 years (median 37 ) |

Sampling Purposive sampling Inclusion criteria Age >18 years Laparoscopy-verified endometriosis |

Data collection Semi-structured interviews in the home or a separate room at the hospital library Length: 33-113 min (median 64 min) Interviewer Midwife and Doctoral student |

Analysis Moustaka's modification of the Stevick-Colaizzi-Keen method (adding interpretation) Analysts Three researchers (two with midwife background, one a PhD student and the other a researcher, the third with a nursing background and researcher) conducted the analysis independently followed by discussion and consensus about the essence. |

The methods used to establish trustworthiness in this study were reporting the audit trail (i.e., describing every step of the data collection and analysis), and using quotations to illustrate the themes and to show that the findings were grounded in the women's stories. To avoid overinterpretation, the research team analysed the data separately, discussed the analysis and found agreement in the interpretation. |

| Hållstam et al.32 Sweden |

Aim of study To examine women's experience of painful endometriosis including long-term aspects, social consequences, impact of treatment and development of own coping strategies Underpinning theory Grounded theory |

Setting At the specialized pain clinic of a tertiary center Participants 13 women Age: 24–48 years (mean 36) |

Sampling Purposive sampling Inclusion criteria follow-up study after treatment for chronic pain at the clinic twenty-nine women were identified as having endometriosis |

Data collection Semi-structured interviews most in a secluded place at the hospital, three in patients' homes, one at a workplace and one in a public library Length; 43- 82 min (mean 59 min). Interviewer Female nurse Female physiotherapist |

Analysis Grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss) Analysts Two researchers (one nurse and one physiotherapist with experience of pain treatment and endometriosis and rehabilitation) |

To ensure credibility research triangulation was performed. A peer review was done involving a gynecologist, a midwife, an anesthesiologist, a pain specialist and a physiotherapist all with experience of patients with endometriosis |

| Huntington & Gilmour29 New Zealand |

Aim of study To explore women's perceptions of living with endometriosis, its effects on their lives and the strategies used to manage their disease. Underpinning theory Feminist research principles |

Setting Local endometriosis support group Participants 18 women Age: 16 to 45 years Diagnostic delay: 5-10 years |

Sampling Information sheets about the project and consent forms were distributed via newsletter Inclusion criteria |

Data collection Individual, semi-structured, audio taped, interactive interviews Interviewer Not described, but familiar with endometriosis and knowledgeable how to handle emotional reactions during the interview |

Analysis Thematic analysis Analysts The authors, with a nursing background and working as researchers at a department for health and social services |

All texts were read, compared and tentative themes identified. Validity or ‘trustworthiness’ of the data in qualitative research relates to how well the data represents the experiences of the participants To determine the validity of the data from this research the findings were presented orally at two meetings of the endometriosis support group |

| Markovic et al.19 Australia |

Aim of study to enrich our understanding of the relationship between the patient's socio-demographic background and health-related phenomena, by identifying distinctive differences among women's narratives. Underpinning theory Grounded theory—but influenced by endurance |

Setting Women residing in the state of Victoria (Australia), with various gynecological conditions Participants 30 women Age 20 to 78 years (mean 43.9) |

Sampling Information about the study was disseminated through community newspapers and notice boards; snowball sampling also occurred. Inclusion criteria Women self-selected |

Data collection In-depth interviews, lasting for about 60 minutes Interviewer |

Analysis Grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss) Analysts |

This was an iterative process in which all authors read the transcripts and developed the coding book. They first identified the themes within individual transcripts and then checked them across narratives. The themes were identified inductively, by careful reading of the interview data, but also by searching for themes identified in prior research in the area of women's reproductive health, as presented in the introduction. Themes were included in the grounded theory only if a significant number of women (about half) spoke about them |

| Moradi et al.20 Australia |

Aim of study to explore women's experiences of endometriosis and its impact, involving three different age groups recruited either from both a hospital clinic and the community. Underpinning theory |

Setting 23 women from a dedicated Endometriosis Centre at one public teaching hospital in Canberra and 12 women from the community (who had not attended the Centre) Participants 35 women Age 17 to 53 years (mean 31.1) |

Method women was purposefully recruited Inclusion criteria confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis (via laparoscopy) for at least a year, who were able to understand and speak English, and had no other chronic disease. |

Data collection Focus groups interviews lasting for about 2.5 h Interviewer Two experienced health professionals with practical knowledge about endometriosis and interviewing skills. |

Analysis Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke) Analysts The whole research team was involved? |

Rigour refers to the quality of qualitative enquiry and is used as a way of evaluating qualitative research. Seven participants from different focus groups were asked to check a transcription of their responses and confirmed its accuracy. |

| Jones et al.26 United Kingdom |

Aim of study Explore and describe the impact of endometriosis on quality of life Underpinning theory Grounded theory to generate categories and concepts |

Setting Gynecology outpatient clinic Participants 24 women (until theoretical saturation) Age:21,5-44 years (mean 32,5) |

Method Theoretical sampling to cover different disease stages and symptom profiles Inclusion criteria Laparoscopically verified endometriosis |

Data collection Semi-structured, in depth interviews at the hospital Mean time: 55 min Interviewer the researcher had no personal experience of endometriosis and only very basic knowledge of its symptoms before the interviews started |

Analysis Constant comparative method Analysts Not described |

Independent coding for some transcripts by a research nurse To reduce interviewer bias and to check whether the codes adequately reflected the emerging areas of HRQoL, a research nurse also went through some of the transcripts. The same themes were identified and the interviewees' dialogues were interpreted in the same way. |

| Roomaney & Kagee30 South Africa |

Aim of study To explore, understand and describe HRQOL among South African women diagnosed with endometriosis. Underpinning theory Quality of life |

Setting In both the private and public health systems at the Western Cape Province of South Africa (gynaecological departments/practices) Participants 25 women laparoscopically diagnosed with endometriosis Age: 25- 42 years (average age 33) |

Method Convenience sampling Inclusion be surgically diagnosed with endometriosis, be 18 years or older and have experienced symptoms during the 3 months prior to being interviewed |

Data collection Semi-structured interviews at participants' homes, places of work, the researcher's office or coffee shops Length: 31- 84 minutes Interviewer Not described |

Analysis Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke) Analysts The two authors |

Both authors checked and re-checked the codes to ensure consistency in the data analysis. In addition, an independent coder was employed to verify the data analysis. Five interviews were coded independently and then compared. Any differences between codes were discussed until a consensus was reached regarding the labelling of codes. A code-book was developed during this process, and the first author used the code-book to code. the remaining interviews. We reviewed samples of coding of the data in order to enhance trustworthiness of analysis. |

| Seear21 Australia |

Aim of study Examine the potentially broader application of these findings for the study of menstrual pain and chronic pelvic pain conditions more generally Underpinning theory a ‘discrediting attribute’ (Goffman, 1963) the ‘menstrual etiquette’ (Laws, 1990) |

Setting From a qualitative study conducted in Australia Participants 20 women Age:24 - 55 years (mean 34). |

Method snowball sampling and advertisement was also placed in the newsletter of an Australian support group |

Methods semi-structured interviews Length of interviews: 45min to 2 h Interviewer Not described |

Analysis Secundary analysis- (Miles and Huberman) Analysts Not described |

A system of diagrams or ‘charts’ were used to display the data and the relationships between emergent themes. Following this process, the researcher returned to the original transcripts of interviews several times to check that the themes and concepts that I had been developed were supported by the data. Any negative cases were noted. |

| Young et al.22 Australia |

Aim of study Explore experiences of health care related to endometriosis and fertility Underpinning theory Not described |

Setting Non-clinical Participants 26 women, the majority in their 30s |

Method invitation by advertisements. After 20 interviews purposeful sampling was applied to ensure diversity Inclusion criteria At least 18 years Surgically verified endometriosis |

Methods In depth, semi-structured interviews, face-to face or over the phone Mean time: 63 minutes Interviewer First author |

Analysis Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke) Analysts Initial analysis by the first author and then all authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of data, |

Analysis, the hierarchy of themes, and final categories of data were discussed among all authors and results were decided by agreement. |

HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

The size of the research sample reported in each article ranged from 9 to 74, with a total sample size of 370 (mean sample size 26). The women in these studies were 16–78 years of age and represented different countries: Australia,18–21 Great Britain,22–25 Italy,26 New Zealand,27,28 South Africa,29 and Sweden.30,31 The data from the 370 women were based on individual interviews, in one case combined with focus group interviews, and one study was based on focus group interviews. All articles had been published from 2004 to 2018. In the second step, the appraisal process contributed to an understanding of how the methodology used in the original research had been applied to study a phenomenon and how that methodology had shaped the researcher's knowledge. The research designs of the primary research articles were compared and contrasted to identify the underlying assumptions of research methodologies, as well as the findings reported.13.15 The authors of the articles meeting the criteria for inclusion in this study described the methods used as qualitative, that is, the studies used phenomenology, narrativism, thematic analysis, grounded theory, and constant comparative analysis. Some researchers used thematic analysis and narrativism for secondary analysis. Analysis revealed that there was a variation in the rigor with which the tenets of the identified method were applied, as well as a range in the quality and quantity of direct quotes available to the analysts of this meta-synthesis.

Preparing the findings for meta-synthesis

The quality of the way in which findings were presented in the articles varied; most articles presented raw data as thematic surveys and/or direct quotations from participant interviews. The metadata analysis used the technique of hermeneutic appraisal33 to extract statements from the articles' findings to evaluate the horizon of the text. The analysts then interpreted these statements within the context of a guiding question: Is this about being perceived or about the health care encounter. Working inductively from these interpretations, the researchers were able to identify possible fusions.15,16

Results

The meta-synthesis resulted in three fusions: Insufficient knowledge, Trivializing—just a women's issue, and Competence promotes health.

Insufficient knowledge

The women often stated that they had repeated problems that the cause of the symptoms seemed to be unknown and they had not been diagnosed. The women felt that the physicians lacked knowledge of the disease, which led to the diagnosis being delayed and that they did not receive adequate treatment. The insufficient knowledge could be demonstrated in several ways. The physicians could judge the symptoms as normal menstruation without examining whether there were other underlying causes. The physicians were annoyed when the women pointed out that their symptoms were similar to those of other women with diagnosed endometriosis. In other cases, incorrect diagnoses were made. The handling of the women's case, both before and after diagnosis, was often based on medical myths.19–32 In this fusion of insufficient knowledge, three themes were identified: normalization of pain as menstrual pain, incorrect diagnosis, and treatment was decided based on medical myths.

The women felt that the physicians dismissed their pain as a menstrual pain and as such something that was normal and that was part of being a woman, something all women live with. The women might receive the comment that they were unlucky that they belonged to the group of women who have severe menstrual pain. It also happened that the physicians believed that the women did not know what pain was (not experienced real pain) and therefore did not tolerate ordinary menstrual pain, even though the women had problems going to the toilet, having intercourse, etc.19,20,23–25,27,29,31,32

The normalization meant that physicians usually did not search for some other underlying cause of the pain. Instead, they often focused on the relief of symptoms. Sometimes lifestyle changes were recommended for example, physical exercise, and the physicians prescribed contraceptive pills to reduce bleeding and pain, even to very young teenage girls. Sometimes the physicians prescribed pain killers and sometimes the women themselves had to suggest the type of pain relief that suited them. Some women refused to take birth control pills because they wanted to know what caused their pain. By extension, the normalization led to the diagnosis being delayed.18,20,22–26,28,30,31

If the women's problem remained after treatment with painkillers and contraceptive pills, the physicians looked for simple causes. The physicians, however, were not inclined to accept that women's symptoms could be caused by any gynecological disorder or illness. Instead, the physicians gave other, incorrect diagnoses. The pain and the problem were located in the abdomen. Women who reported that they had simultaneous problems with the abdomen or intestines could receive diagnoses such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome, appendicitis, or muscle stretching. The problems could also be seen as mental. Some physicians thought the problem was in the head and not in the body. The women were diagnosed with depression or the physician blamed the symptoms on possible early abuse of alcohol or other drugs, on infection, or on previous miscarriage. Young women, students, were treated as being persons who did not take care of themselves.19,23,26,29–32

The women were referred to specialists such as psychiatrists or gastroenterologists before finally getting to meet a gynecologist. Some physicians put faith in so-called medical myths, which women knew were wrong, for example, that young women or teenage girls were too young to have endometriosis. Other myths concerned treatment when the women had been diagnosed. The women could receive the recommendation to remove the uterus, even though they were only in their twenties. Another myth that the physicians referred to was that the women's pains would be cured if they gave birth to children. Some arguments were that the hormones would restore the balance in the body or that the endometriosis would shrink and would not grow further.20,22,24,26,27,29,31,32

The recommendation for childbirth could be perceived as particularly offensive. Some women recalled that doctors recommended pregnancy as a treatment, even if they were infertile. Some other women were in such a situation that it was not suitable to have children at that time.

Trivializing—just a women's issue

The women in these studies felt that no one took their problems seriously. Their discomfort was trivialized or completely disregarded. The physicians meant/felt that the symptoms were part of being a woman. The women's problems did not generate much interest and did not lead to continued investigation. The attitude was to take some painkillers and live as usual.

The approach of the physicians was described as offensive and sometimes blameful. There was little understanding of the fact that the problems could affect women's social life and quality of life.21,23–27,29,31

In this fusion of incorrect diagnoses three themes were identified: Not being taken seriously, no interest in women's problems, and insensitivity to women's situation.

The women felt that their symptoms were more difficult than painful menstruation and referred to their menstrual history and compared themselves with family and friends. The most common cause of dissatisfaction or anger by women was the feeling that physicians did not take their symptoms seriously. As their problems were not taken seriously, the physicians did not refer them for further investigation and treatment. The women felt denied since the physicians' attitude was that women exaggerated or imagined their symptoms, like having a form of “fantasy pain,” or had low pain thresholds. The women were requested to learn to handle their pain. Other women felt that the physicians wanted the women to feel that they had failed morally because they could not cope with their pains like other women. There was always a struggle to be taken seriously.24–27,31,32

The women who, after years of rejection and normalization of the pain, were referred for examination and received a diagnosis felt that they had finally received “evidence” that they had a disease and thus were able to discuss treatment options. The diagnosis was a relief. It was a confirmation that they had a disease and it was not just something in their head. However, even when the disease was verified with, for example, image evidence, physicians could question whether the pains really were proportional to the size of the lesions.23–27,31,32

The women felt that their symptoms were not very interesting or exciting for the physicians, or as it was expressed in a study—“endometriosis is not a sexy disease.” They felt invisible when the physicians were not interested in understanding them and their pain problems. Others felt that they were wasting their physicians' “time” because the physician believed that the trouble “was in the head”. The physicians showed lack of interest and distance when the women talked about their problems. They sighed, drummed their fingers on the table, avoided eye contact, and responded monotonously or with specialist terms. When simple explanations or jargon did not work, the physicians switched to normalizing or trivializing the problems.

The most difficult thing was when the physician moved the burden over to the women by asking how they wanted to be helped.23–25,27,29–32

There were also physicians who in a more brutal way showed their lack of interest. The physicians could argue that there was no diagnosis called menstrual pain, and that it was only stupid women who expressed themselves like this.24–26,28,31,32

The physicians could show insensitivity to the women's situation, which could be experienced as verbally, psychologically, and physical violations. For example, the physician could convey the information about the woman's endometriosis and infertility in an insensitive manner. It could be positive to get all this important information about endometriosis, but if the physician in the same breath mentioned infertility, it became too heavy. When the women raised the issue of children, they were abruptly informed that they would probably need to adopt. The physicians had not endeavored to find out about the women's life situation. There were women who had always longed to create a family but who were given the message about their infertility in an insensitive way, and this affected them for a long time to come. Some women even considered suicide because they had always wanted to have a family, and this dream had been totally crushed.22–25,30–32

The women described that they were in a difficult and vulnerable situation, filled with anxiety and frustration, which was mentally devastating. It was then difficult to be called stupid, crazy, and mentally ill.22,24,25,27,28,31,32

The women also felt physically vulnerable. Painful gynecological examinations could feel like abuse even though they were routine. The women did not want to undergo such examinations, but they had to.

Competence promotes health

The third fusion describes positive experiences of meetings with physicians, and four studies contributed.22,23,27,31,32 Although the women mostly experienced ignorance and lack of interest in primary care, there were physicians who were interested in their problems. The insufficiency of knowledge became a minor concern if the women had a supportive relationship with their physician. Such physicians could help by listening and not delaying the referral to a specialist. One woman also said that the physician was not aware of endometriosis during the first visit but had done his homework before the next meeting.

Transferring from general to specialized care could offer a positive change. The women were reassured by knowing that they would be treated by physicians with special skills and competency. After several years of suffering they received a diagnosis and an explanation of why they had these problems. They acknowledged that the gynecologists showed that they cared, actively listened, and took them seriously. Such dedicated gynecologists took the time to explain and provide relaxation tips that could make the examination procedure easier. Women with fertility problems reported that their disease burden was alleviated by the physician communicating well about fertility. It also meant a lot that the gynecologist shifted focus from only the disease to how it affected the woman's life and situation. This strengthened and promoted women's health, helping them to continue their lives.

Validation of the findings using a survey study

The analysts used a large qualitative survey study, including open questions to validate or “member check” the findings and interpretations from the metadata analysis/synthesis.34 This survey study included 135 women with endometriosis who evaluated a training program about social support, treatment, as well as professional and health care system performance. Because our study is a meta-analysis/synthesis of text, we did not have the opportunity to “member check” the findings with participants of the study. Since this survey study was performed with other participants and in another country (Germany),35 the findings from this survey study can be used for validation and triangulation of this meta-synthesis. The findings of this survey study pointed out some important factors.

Knowledge and competence were found to be among the most important factors when making the women with endometriosis feel confident and cared for. The second factor of importance was that the physicians/gynecologist believed in the women's descriptions about the symptoms and problems, that is, the women were taken seriously. The care encounters should be imbued with understanding and empathy. The third factor that was experienced as supportive was open and clear communication, based on interest and sensitivity. Obstacles and hindrances for women with endometriosis concerning managing their situation were ignorance, insufficient empathy, and nonsensitivity. These findings are in great agreement with those in the meta-synthesis, which strengthens its trustworthiness.

Discussion

In this meta-synthesis, data from 14 research studies on women with endometriosis were reinterpreted to gain a deeper understanding of how they were perceived or about the health care encounter. We used the women's quotations presented as raw data and the text in the findings to draw an interpretation and gain an understanding of the phenomenon under study. It is interesting to note that even though the studies are from 2004 until 2018, the experiences of the women seem to remain. There are still the same issues and approaches perceived, but medical progresses are made.

The credibility (validity) of the data interpretations in this study is supported because they are the result of a systematic approach13 and can always be arbitrated for or against a variety of other interpretations. The data analyzed and interpreted in this study comprised primary research conducted on women from different cultures and contexts, but all having an endometriosis diagnosis. There are several other reviews that have synthesized qualitative research on how endometriosis affects women's lives and how they handle the problems.10,36–39 One of them focused on experiences of care and patient centering,37 whereas the others had a broader perspective. However, the selection of studies differs in part between our meta-synthesis and the other overviews. In addition, new studies have been added that are only included in our overview. The article by Dancet et al.38 also combined quantitative and qualitative articles, but in our meta-synthesis we only used qualitative articles. The fusions identified in our overview have not been highlighted as much in the other overviews. Some of our findings regarding experiences, how being approached from health care, are unique to women with endometriosis.

Insufficiency knowledge and its underlying themes could be found in the overview.10 This overview, however, emphasized mainly that the women sought knowledge and that the doctors compensated for their lack of knowledge by being more responsive. Insufficient knowledge was made visible in incorrect diagnoses and delayed diagnoses in three of the reviews,9,36,37 whereas the fourth found that it was about the lack of information.

The findings in this meta-synthesis may seem discouraging; the treatment of the women revealed perceived with ignorance about endometriosis and they experienced that their problems were trivialized; it was just a “women's issue.” This fusion was a strong theme based on the women's statements in the various studies that we included. In the overview articles, this “woman issue” was described as normalization of the problems and damaged wellbeing10,38 and also a cause of delayed diagnostics due to normalization and trivialization of women's problems.37 Dancet et al.38 mentions what lies in the subthemes of this fusion, namely to respect women's problems and to let the women be trusted. Others seem to be shared with persons with other types of chronic pain, mainly musculoskeletal and where most studies capture experiences from primary care. One common experience is the sense of not being believed since the pain is not visible or measurable was, for example, captured in qualitative evidence syntheses about chronic pain conditions40 and focusing on pelvic pain.41 The hard work to get a medical diagnosis was also central. Focusing on these issues there are some suggestions for developing endometriosis and pain centers, by using patient navigators, and working multidisciplinary.42

Our third fusion that competence promotes health, which is included in this theme, is the only fusion that brings forth some positive aspects acknowledged in the analyzed studies. That competency promotes health is often mentioned in one or two sentences here and there in the overviews.10,36 The fact that our three fusions are not clearly found in the overview articles that we compare in this study may be because these (three out of four) are merely descriptive and reflect what we already know. The fourth review article used “interpretation,” but on a combined material; quantitative and qualitative articles. This causes a methodological difficulty to extract material narratively/interpretatively from quantitative results.

We performed a meta-synthesis to, through interpretation, lift research results/findings to the next level and not only repeat what we already knew with some certainty.14 The meta-synthesis used in this study was grounded in hermeneutic theories.16,34 In this way, we clarified the women's experience of the encounter in endometrial care. We have interpreted and synthesized fusions and therefore it seemed relevant to discuss the results against other reviews—bringing forth synthesized data. Trying to broaden the one perspective view.

When we validated our fusions with the survey study,35 there was a finding showing that there are possibilities to make a positive difference regarding these women, by showing empathy and adopting a professional and competent approach. In a quite recently published article43 it was shown that medical education needs to equip physicians with the skills to acknowledge and incorporate women's knowledge of their bodies within the medical encounters. It was also highlighted that the women should be acknowledged and treated as partners in their health.

Conclusion

The present meta-synthesis demonstrates that the “journey of endometriosis care” takes its starting point in primary care and there is a struggle to convince health care professionals that the symptoms are not ordinary menstrual pain and bleeding. There was also a struggle in that discomfort was trivialized and seen as women's issue. Transferring from general to specialized care could offer positive changes. The women were reassured by knowing that they would be treated by physicians with special skills and competency.

Clinical Implication

Living with endometriosis and how one is perceived in the health care encounters have a great impact on these women's lives. The results of the present study highlight the importance of providing support for women who have endometriosis, so they are able to manage their everyday lives. Health care professionals need to be aware of endometriosis as a disease and be more sensitive for individual pain pattern among women, which could facilitate manageability. ESHRE44 presents clinical practice guidelines regarding medical progression, but health care professionals need to make their own clinical decisions based on their competency, considering the circumstances, and collaborate with the women.

Abbreviation Used

- HRQoL

health-related quality of life

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this study.

Cite this article as: Pettersson A, Berterö CM (2020) How women with endometriosis experience health care encounters, Women's Health Report 1:1, 529–542, DOI: 10.1089/whr.2020.0099.

References

- 1. Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2017;32:15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benagiano G, Brosens I. The history of endometriosis: Identifying the disease. Hum Reprod 1991;6:963–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Endometriosis World. World Statistics of Endometriosis, 2017. Available at: https://endometriosisworld.weebly.com/world-statistics.html Accessed June25, 2020

- 4. Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2012;98:511–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, et al. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: A multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod 2007;22266–22271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mao AJ, Anastasi JK. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: The role of the advanced practice nurse in primary care. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2010;22:109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wykes CB, Clark TJ, Khan KS. Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: A systematic quantitative review. BJOG 2004;111:1204–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Albee RB Jr, Sinervo K, Fisher DT. Laparoscopic excision of lesions suggestive of endometriosis or otherwise atypical in appearance: Relationship between visual findings and final histologic diagnosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2008;15:32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosisd Germany: Causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3412–3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Women's experiences of endometriosis: A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Sexual Rep Health 2015;41:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao J, Liu HQ, Wang Y, Shang YL, Hu F. Effects of psychological care in patients with endometriosis: A systematic review protocol. Medicine 98. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Evans S, Fernandez S, Olive L, Payne LA, Mikocka-Walus A. Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: A systematic review. J Psychosomat Res 2019;124:109756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. SBU. Endometrios; Diagnostik, behandling och bemötande (Endometriosis, diagnosis, treatment and being perceived). Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Creating metasummaries of qualitative findings. Nurs Res 2003;52:226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Res Nurs Health 2003;26:153–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paterson ML, Thorne SE, Canam C, Jillings C. Meta-study of qualitative health research. Practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kent B, Fineout-Overhold E. Using meta-synthesis to facilitate evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs 2008;5:160–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bondas T, Hall EO. Challenges in approaching metasynthesis research. Qual Health Res 2007;17:113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Markovic M, Manderson L, Warren N. Endurance and contest: Women's narratives of endometriosis. Health: An Interdisciplinary. J Soc Study Health Illness Med 2008;12:349–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moradi M, Parker M, Sneddon A, Lopez V, Ellwood D. Impact of endometriosis on women's ‘lives; a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:123–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: Stigmatization, menstrual concealment, and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1220–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Endometriosis and fertility: Women's accounts of healthcare. Hum Reprod 2016;31:554–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2006;86:1296–1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Denny E, Mann CH. Endometriosis and primary care consultation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;139:111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Denny E. I never know from one day to another how I will feel: Pain and uncertainty in women with endometriosis. Qual Health Res 2009;19:985–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones G, Jenkinson C, Kennedy S. The impact of endometriosis upon quality of life: A qualitative analysis. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2004;25:123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Facchin F, Saita E, Barbara G, Dridi D, Vercellini P. “Free butterflies will come out of these deep wounds”: A grounded theory of how endometriosis affects women's psychological health. J Health Psych 2018;23:538–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gilmour JA, Huntington A, Wilson HV. The impact of endometriosis on work and social participation. Int J Nurs Pract 2008;14:443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huntington A, Gilmour JA. A life shaped by pain: Women and endometriosis. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:1124–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roomaney R, Kagee A. Salient aspects of quality of life among women diagnosed with endometriosis: A qualitative study. J Health Psychol 2018;23:905–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grundström H, Alehagen S, Kjølhede P, Berterö C. The double-edged experience of healthcare encounters among women with endometriosis: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hållstam A, Stålnacke BM, Svensén C, Löfgren M. Living with painful endometriosis—A struggle for coherence. A qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthcare 2018;17:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gadamer HG. Truth and method. London: Sheds and Wards, 1975/2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Risser J. Reading the text. In: Silverman JH, ed. Gadamer and hermeneutics. London: Routledge, 1991:93Y105. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kundu S, Wildgrube J, Schippert C, Hillemanns P, Brandes I. Supporting and Inhibiting factors when coping with endometriosis from the patients' perspective. Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2015;75:462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: A critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update 2013;19:625–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaatz J, Solari-Twadell PA, Cameron J, Schultz R. Coping with endometriosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010;39:220–225; quiz 225-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dancet EA, Apers S, Kremer JA, Nelen WL, Sermeus W, D’ Hooghe TM. The patient-centeredness of endometriosis care and targets for improvement: A systematic review. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2014;78:69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Erwin EJ, Brotherson MJ, Summers JA. Understanding qualitative metasynthesis. Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. J Early Interv 2011;33:186–200 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Crowe M, Whitehead L, Seaton P, et al. Qualitative meta-synthesis: The experience of chronic pain across conditions. J Adv Nurs, 2017;73:1004–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Toye F, Seers K, Hannink E, Barker K. A mega-ethnography of eleven qualitative evidence syntheses exploring the experience of living with chronic non-malignant pain. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Opoku-Anane J, Orlando MS, Lager J, et al. The development of a comprehensive multidisciplinary endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain center. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord 2020;12:3–9 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Young K, Fisher J, Kirkman M. Partners instead of patients: Women negotiating power and knowledge within medical encounters for endometriosis. Fem Psychol 2020;30: 22–41 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guidline: Management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2014;29:400–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]