Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an equitable partnership approach that links academic researchers, community organizations, and public health practitioners to work together to understand and address health inequities. Although numerous educational materials on CBPR exist, few training programs develop the skills and knowledge needed to establish effective, equitable partnerships. Furthermore, there are few professional development opportunities for academic researchers, practitioners, and community members to obtain these competencies in an experiential co-learning process. In response, the Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center developed the CBPR Partnership Academy, an innovative, yearlong capacity-building program facilitated by experienced community and academic partners, involving an intensive short course, partnership development, grant proposal preparation and funding, mentoring, online learning forums, and networking. Three diverse cohorts (36 teams) from 18 states and 2 tribal nations have participated. We describe the rationale and components of the training program and present results from the first two cohorts. Evaluation results suggest enhanced competence and efficacy in conducting CBPR. Outcomes include partnerships established, grant proposals submitted and funded, workshops and research conducted, and findings disseminated. A community–academic partner-based, integrated, applied program can be effective for professional development and establishing innovative linkages between academics and practitioners aimed at achieving health equity.

Keywords: health equity, community-based participatory research, professional development, academic researchers and practitioners linkages

INTRODUCTION

I come from a clinical psychology training, and to have an opportunity to leave my discipline and intermingle with other health professionals and community professionals is a new experience for me. I think this is really going to transform the work that I do and the way that I do it.

—CBPR Partnership Academy Participant

Community-engaged approaches to research, interventions, and policy change are needed to address the social and environmental determinants of population health and reduce racial and ethnic health inequities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013a; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel, & Minkler, 2018). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is such an approach, involving academic researchers, public health practitioners, and community-based entities (Ahmed et al., 2016; Braun et al., 2015; Israel et al., 2013a; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Schulz et al., 2015; Wallerstein et al., 2018). A 2003 Institute of Medicine report identified CBPR as one of eight core training areas for all public health professionals (Gebbie, Rosenstock, & Hernandez, 2003).

As CBPR funding opportunities increase, so does the need to enhance capacity of researchers and public health practitioners to use this approach (Allen, Culhane-Pera, Pergament, & Call, 2011; Coffey et al., 2017; Israel et al., 2013a; Zittleman et al., 2014). While some institutions provide graduate-level courses in CBPR, this training may not have been available to those already in the field. Despite recent development of educational materials and training programs (Allen et al., 2011; Coffey et al., 2017; Gebbie, 2008; van Olphen et al., 2015; Zittleman et al., 2014), few professional development opportunities link academic researchers and public health practitioners with community-based partners to obtain these skills through a co-learning process facilitated by experienced academic–community instructor teams (Andrews et al., 2013; Masuda, Creighton, Nixon, & Frankish, 2011).

To address this gap, the Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center (Detroit URC), a CBPR partnership established in 1995 (Israel et al., 2001), designed and implemented the CBPR Partnership Academy, an integrated, yearlong program to enhance capacity of academic–community pairs new to CBPR. The term community as referred to here, includes community organizations and public health practitioners. The CBPR Partnership Academy is facilitated by highly experienced community and academic partners and involves an intensive short course, hands-on partnership development, grant proposal preparation and implementation, mentoring, online learning forums, and networking. The Detroit URC conducted a mixed method, participatory, and formative evaluation of the program. This study examines the extent to which the CBPR Partnership Academy enhanced participants’ capacity to engage in CBPR. We describe program development, implementation, and evaluation, and analyze results from the first two cohorts. We discuss recommendations and implications for practice with particular attention to professional preparation of researchers, public health practitioners, and community entities to use a CBPR approach to conduct and evaluate research, interventions, and policy initiatives to promote health equity.

BACKGROUND

Overview of Community-Based Participatory Research

Many labels describe community-engaged research (Gebbie et al., 2003), building off a long, multidisciplinary history of participatory approaches to research. In public health, community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been used to represent such collaborative approaches (Israel et al., 2001; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2008; Viswanathan et al., 2004). CBPR is a partnership approach to research that equitably involves community members, organizational representatives, public health practitioners, and researchers in all aspects of the research. All partners contribute expertise and share decision making and ownership to increase knowledge and understanding of a phenomenon, and integrate that knowledge with interventions, policy advocacy, and social change to improve quality of life for communities and reduce health inequities (Israel et al., 2018; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Its applicability to interventions, policy change, evaluation, and sustainability make CBPR especially relevant for public health educators (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013b; Wallerstein et al., 2018).

Overview of the Detroit Urban Research Center

The Detroit URC promotes community–academic partnerships to enhance understanding of how social and physical environments affect health and to translate that knowledge into interventions, programs, and policies that build on community resources and strengths to promote health equity. The center is directed by a Board composed of representatives from partner organizations: nine community-based organizations, the local health department, an integrated health care system, and a university (see Authors’ Note) (Israel et al., 2001). The Detroit URC has facilitated over 15 affiliated CBPR partnerships to conduct more than 40 etiologic, intervention, and evaluation studies on critical health issues. Center members conduct workshops nationally and internationally and have mentored and trained dozens of researchers, practitioners, and community members in using a CBPR approach. Building on this experience, the Detroit URC received funding in 2014 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to design, implement, and evaluate the CBPR Partnership Academy.

Conceptual Model Guiding the CBPR Partnership Academy

The Partnership Academy is guided by an experiential action learning model (Browner & Preziosi, 1995; Cunningham, 1998; Johnson & Johnson, 2017; Kolb, 2015). Core principles and assumptions for capacity-building and health education programs are that learning is (1) more meaningful when participants are actively involved in real experiences requiring solutions, (2) more effective when participants are engaged in experiences to gain and then apply knowledge, (3) enhanced when participants develop strategies to address a problem and reflect on decisions, (4) improved when participants learn with and from each other, and (5) more likely to change knowledge, behavior, and attitudes when participants are actively involved in the process (Cunningham, 1998; Johnson & Johnson, 2017; Kolb, 2015). Accordingly, the Partnership Academy creates new understandings and research skills for conducting CBPR by combining didactic methods, interactive activities, group discussions, problem-solving tasks, reflection, and feedback. The model recognizes learning as a continuous cycle of knowledge acquisition, experience, observation, and reflection; development of concepts and generalizations; and integration and application to real-life situations (Kolb, 2015).

METHOD: PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION AND EVALUATION

Program Design

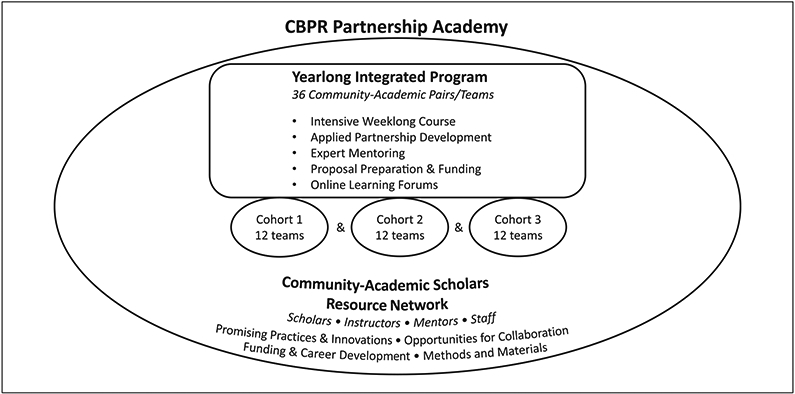

The CBPR Partnership Academy applies this experiential action learning model in an integrated, yearlong learning program consisting of five components: a weeklong intensive course, development and implementation of a partnership development planning grant, mentoring by an expert community–academic pair, structured online learning activities and peer exchange, and an ongoing network (see Figure 1). Throughout the year, each team develops a CBPR partnership focused on improving their community’s health and well-being. The experiential action learning model is applied throughout. For example, in the course, participants gain knowledge and skills with case study activities applied to their interests. Participant teams apply the learning acquired during the course to a project in their own community. Community–academic mentoring provides feedback as teams develop and reflect on their partnership strategies. Diverse participants learn from each other through the ongoing forums and network. Periodic evaluation and reflection activities foster co-learning and change. Equity is highlighted throughout.

FIGURE 1. CBPR Partnership Academy.

NOTE: CBPR = community-based participatory research. Three yearlong cohorts of 12 community and academic pairs/teams (36 pairs, 72 individuals) participated in the program. All participants are eligible for membership in the ongoing Scholars Resource Network.

Participant Eligibility, Recruitment, and Selection

Applicants are self-identified pairs of one academic and one community/public health practitioner partner who are in a new or early-stage partnership, interested in using CBPR to eliminate health inequities. Teams submit a joint application that includes their experience, goals, and objectives for the CBPR Partnership Academy. Twelve teams are selected each year by a committee of Detroit URC community and academic Board members, with attention to multiple dimensions of diversity (e.g., geographic, rural/urban, racial/ethnic, disciplines) (Corbie-Smith et al., 2015). This article reports on the first 2 cohorts of 12 two-person teams that completed the program.

Program Components

Weeklong Course.

All participants attend an intensive CBPR course at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, taught by expert academic–community teams from the Detroit URC. The curriculum builds knowledge and skills in research, equity and cultural humility, mixed methods, innovative research designs, responsible conduct of research, benefits and challenges, and partnership evaluation. Using experiential learning, classes include presentations, discussions, case studies, group exercises, and team co-learning and relationship-building opportunities. Community instructors lead a Detroit trip highlighting long-standing CBPR partnerships.

Partnership Development Grant Proposal and Implementation.

Following the course, each team writes a noncompetitive grant proposal to develop and implement a CBPR partnership/project addressing an important issue in their community. The $1,500 grant supports activities such as creating partnership structure, convening collaborators, and conducting pilot studies.

Mentoring.

Teams are matched with expert community–academic mentor pairs (Moreno-John et al., 2007). Mentors provide written and verbal feedback on the grant proposal and guidance on partnership implementation during conference calls held every other month.

Ongoing Learning Forums and Peer Exchange.

Online forums on alternate months deepen learning through interactive presentations by instructors/mentors on participant-identified topics (e.g., partnership development, grant writing). Participants share progress and challenges, provide peer feedback, and build relationships.

Community–Academic Scholars Resource Network.

Current and former participants, instructors, and staff continue to exchange information and resources (e.g., funding, career development, collaboration opportunities) through an online network.

Program Evaluation Methods

The participatory and formative evaluation involves program instructors/mentors, staff, and the Detroit URC Board to prioritize research questions, decide on measurement tools and methods, and interpret and apply findings (Coombe, 2012; Cousins, 2012). Results are shared regularly with participants, instructors/mentors, and staff using participatory evaluation and CBPR processes of feedback-interpretation-application (Wiggins et al., 2018) to assess progress and make improvements. Process evaluation examines implementation to understand how and why aspects of the program were more or less effective. Outcome evaluation assesses the program’s effect on participants’ CBPR capacity.

This study examines whether the CBPR Partnership Academy increased the CBPR capacity of community–academic partners, and the extent to which and how participants applied the skills and knowledge in their work. The mixed methods design (Creswell, 2014; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017) uses measurement tools developed by the program team, including a pre– and post–Partnership Academy survey, two postcourse evaluation questionnaires, questionnaires administered immediately following each online forum, periodic focused group discussions, webbased network use analytics, and program documentation. Questionnaires include closed- and open-ended questions and are administered using Qualtrics Survey Software, Version 2018 (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

Measures of course effectiveness include quality and usefulness of instruction and materials, CBPR knowledge (Israel et al., 2013b), self-efficacy, most and least valuable experiences, and recommended changes. Overall program effectiveness is assessed in online forum and post–Partnership Academy questionnaires by how beneficial each component was, satisfaction, and whether expectations were met. To measure CBPR capacity outcomes, at pre- and postprogram, participants rate their competence (skills, expertise, knowledge) (Gebbie, 2008; Israel et al., 2013) and self- and team-efficacy (Bandura, 1997) on 10 CBPR phases. At postprogram, participants also rate whether the Partnership Academy enhanced competence and efficacy in four key dimensions of CBPR, intention to engage in future CBPR-related activities, and team accomplishments for 12 success measures (e.g., funding, dissemination). Survey items are rated on a 5-point scale (e.g., from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Data Analysis

We generated descriptive statistics using Qualtrics and SAS software, Version 9.4 TS Level1M1 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We report frequency and percent agreement (agree or strongly agree) for survey items. Forty-five of 48 participants completed the closed-ended postcourse questionnaire. Thirty-five of 48 participants (73%) completed both pre– and post–Partnership Academy questionnaires. Participants who did not complete both waves of data (pre- and post-) did not differ systematically from those who did (e.g., community/academic, gender). Examining frequency distributions provided statistical evidence to treat items as continuous variables. We calculated comparisons for cohorts separately and pooled. Given cohort demographic comparability and the analytic method of pairwise comparison, we report pooled results. Pairwise comparisons of pre- and post-Academy scores were analyzed using generalized estimating equations. We computed means and standard errors of the differences of participant ratings before and after the program and tested statistical significance using z scores. Qualitative data from questionnaires were analyzed by a grounded theory method of open thematic coding using verbatim language and grouping content conceptually using constant comparison (Charmaz, 2014). One lead coder assigned codes, a second coder reviewed them, and any discrepancies were reconciled through discussion.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Two cohorts totaled 24 teams (48 individuals) from 13 states and 1 tribal nation, representing urban, rural, and island communities. Sixty-seven percent are persons of color and 73% are women. Academics represent disciplines including sociology, psychology, epidemiology, public health, medicine, and nursing. Community partners include nonprofit, advocacy, and health care organizations. Teams represent diverse interests and communities of identity, including multiple racial/ethnic identities, low-income, homeless, adolescent, and immigrant communities.

Program Implementation and Effectiveness

Weeklong Course Assessment.

Table 1 presents results from the postcourse evaluation questionnaire administered immediately following the course (45 of 48 responded).

TABLE 1.

CBPR Partnership Academy Participant Postcourse Assessment of Course Effectiveness and Perceived Knowledge and Confidence (Cohorts 1 and 2)

|

Cohort 1 (n = 22) |

Cohort 2 (n = 23) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Agree/Strongly | Agree/Strongly | |

| Questionnaire Measurement Items | Agree, n (%) | Agree, n (%) |

| Course implementation and effectiveness: Please indicate your level of agreement about the overall course material and instruction. | ||

| Overall course content and structure was well organized. | 15 (73) | 23 (100) |

| Course instructors demonstrated expertise in the subject matter. | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Learning resources (binder, course pack, resource list) will be useful to me in the future. | 20 (91) | 22 (96) |

| Teaching and class learning materials were effective. | 13 (59) | 22 (96) |

| Interactive exercises and questions were used effectively. | 10 (46) | 21 (91) |

| Interactive exercises and questions were at an appropriate level. | 12 (54) | 19 (83) |

| Knowledge (for each course learning objective): At the end of the course I am able to | ||

| Define CBPR and explain the rationale for its use in addressing major public health problems | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Identify and explain the phases and core principles of CBPR and application of the principles to develop, maintain, sustain, and evaluate CBPR | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Describe and analyze the use of quantitative and qualitative research methods in the context of CBPR approach to research and interventions | 20 (91) | 22 (96) |

| Discuss the relevance and application of mixed methods in the context of CBPR | 21 (96) | 22 (96) |

| Discuss the role of the partners in the feedback, interpretation, dissemination, and application of research | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Identify and discuss the benefits and challenges of CBPR and the facilitating factors for overcoming these challenges | 21 (96) | 23 (100) |

| Explain ethical considerations in the responsible conduct of research | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Describe conceptual framework and methods of evaluating a CBPR partnership process | 18 (82) | 22 (96) |

| Present and analyze innovative research designs that complement randomized controlled trial designs such as randomized staggered intervention designs | 12 (55) | 21 (91) |

| Discuss different statistical issues involved in using innovative research designs | 10 (45) | 18 (78) |

| Describe and demonstrate the use of electronic systems to promote ongoing, interactive communication and feedback within and across CBPR | 21 (96) | 17 (74) |

| Partnership Academy members | ||

| Confidence/self-efficacy: Now that I have completed the course I am confident that I can | ||

| Form a CBPR partnership | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Assess community strengths and dynamics | 20 (91) | 22 (96) |

| Identify public health and research priorities | 21 (96) | 22 (96) |

| Design and conduct research | 20 (91) | 23 (100) |

| Apply ethical principles to conduct responsible research | 22 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Perform data analysis | 14 (64) | 20 (87) |

| Interpret research findings | 21 (96) | 20 (87) |

| Apply research findings to interventions and policies | 18 (82) | 23 (100) |

| Disseminate research findings | 20 (91) | 23 (100) |

| Evaluate a CBPR partnership | 18 (82) | 23 (100) |

| Sustain the work of a CBPR partnership | 18 (82) | 22 (96) |

NOTE: CBPR = community-based participatory research. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following items on the scale: 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree.

The first section shows participant ratings (percentage agreed/strongly agreed) on six items to assess course implementation and effectiveness. Assessment of instructors and learning resources were high for both cohorts. Ratings related to teaching materials and activities trended higher the second year.

The second section of Table 1 presents participant knowledge of 11 CBPR competencies mapped onto course learning objectives. For 7 of 11 learning objectives, more than 90% of participants in each cohort agreed/strongly agreed that they were able to perform the action, with an eighth item (conceptual frameworks and evaluation) receiving over 80% agreement in both cohorts.

The third section of Table 1 displays participants’ confidence/self-efficacy for 11 key steps of conducting CBPR. Participants rated high levels of confidence (over 82%) on all items except perform data analysis, which was rated lower in the first year only.

Table 2 presents findings from open-ended course evaluation questions asking what was most valuable/beneficial. Major themes included strengthened partnerships by participating in community–academic pairs, CBPR learning through experiential learning, knowledgeable CBPR trainers, relationships/networks built among diverse colleagues, and ongoing opportunities to integrate learning beyond the course.

TABLE 2.

Most Beneficial Aspects of the CBPR Intensive Course from Postcourse Evaluation Open-Ended Questions by Summary Themes (Cohorts 1 and 2)a

A. Participating together with community and academic partner strengthened relationship and provided time to develop the partnership

|

B. Gained in-depth understanding of all aspects of CBPR through experiential action learning process, in-person

|

C. Knowledgeable, experienced community and academic co-trainers and long-standing partnerships exemplified CBPR, strengthened learning

|

D. Participating with diverse colleagues for a week together built supportive relationships/networks across the country with others engaged in CBPR for health equity

|

E. Ongoing guidance from instructors/mentors, materials, tools, peers will integrate and reinforce course learning beyond the course

|

Combined data from open-ended items on both Qualtrics administered and paper administered questionnaires for Cohorts 1 and 2.

Integrated Yearlong Learning Activities

Partnership Development Grant Proposal and Mentoring Activities.

Participant teams submitted and revised a small grant proposal, incorporating feedback from their mentors. In written comments on their revised grant proposals, ongoing learning forum discussions, and on the post–Partnership Academy evaluation questionnaire, participants consistently reported that they valued mentor feedback, incorporated mentors’ advice on implementation throughout the year, and adapted projects accordingly.

Our mentors’ feedback was incredibly helpful and allowed us to submit a stronger proposal. We really enjoyed the process of first receiving written feedback, and then having an opportunity for a lengthy discussion. (Partnership Academy Participant)

Participants cited the important role mentors played in assisting groups to be realistic and not overly ambitious and to focus sufficient time on developing trust, relationships, and group processes to form a strong foundation for their CBPR partnership.

Ongoing Learning/Peer Exchange Forums.

Attendance at bimonthly forums averaged 67% and 80% for Cohorts 1 and 2, respectively. Among those completing postforum questionnaires, at least 95% of participants in any given forum indicated they were satisfied/very satisfied and that facilitators fostered a co-learning environment. Participants cited as most valuable having supportive connections with others, getting feedback on their project, and sharing ideas on how others address similar situations.

Community–Academic Scholars Resource Network.

In the postprogram survey, only 11% of Cohort 1 participants rated the online network as moderately, very, or extremely beneficial. For Cohort 2, that rating increased to 70% following a change in networking platforms recommended by participants.

Overall Program Assessment

Among those who completed the post–Partnership Academy survey, 88% indicated that they were very/extremely satisfied with the program. Seventy-four percent reported that the program exceeded/greatly exceeded expectations; 24% said the program met expectations. Percentage who rated very/extremely beneficial for the following components are: course (91%), Detroit trip (89%), partnership development grant (86%), receiving proposal feedback from mentors (83%), implementing the proposal (83%), and mentoring (72%). In course evaluations (Table 2) and forum discussions, participants reported diversity of participants and instructors as one of the most beneficial aspects of the program.

Capacity Outcomes

Change in Perceived Competence and Confidence to Conduct CBPR.

To examine whether the program enhances CBPR capacity, we compared participants’ self-assessment before and after the program. Table 3 compares means of each participant’s change in perceived competence and confidence on 10 core CBPR activities measured at pre- and postprogram, pooling data for Cohorts 1 and 2. Perceived competence increased significantly for all 10 items (p < .001). Confidence in the individual’s ability to achieve the activities (self-efficacy) and the team’s ability (collective-efficacy) increased significantly for all items (p < .05).

TABLE 3.

Pairwise Comparison of Pre- to Postprogram Scores for Competence, Confidence (Self-Efficacy), and Team Confidence (Collective-Efficacy) for Cohorts 1 and 2 Pooled (n = 35)

| Outcome Measured | Pre M (SE) | Post M (SE) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-rated competence (i.e., expertise, skill) in using a CBPR approach to do the following: | |||

| Form a CBPR partnership | 2.91 (0.13) | 3.86 (0.16) | <.001 |

| Assess community strengths and dynamics | 3.06 (0.12) | 3.91 (0.13) | <.001 |

| Identify public health and research priorities | 3.19 (0.12) | 3.87 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Design and conduct research | 3.21 (0.13) | 3.81 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Perform data analysis | 3.07 (0.15) | 3.46 (0.16) | <.001 |

| Interpret research findings | 3.27 (0.14) | 3.85 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Apply research findings to interventions and policies | 3.11 (0.13) | 3.81 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Disseminate research findings | 3.03 (0.19) | 3.87 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Evaluate a CBPR partnership | 2.26 (0.14) | 3.46 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Sustain the work of a CBPR partnership | 2.49 (0.15) | 3.55 (0.15) | <.001 |

| Confidence that you are able to | |||

| Form a CBPR partnership | 3.38 (0.16) | 4.22 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Assess community strengths and dynamics | 3.50 (0.13) | 4.01 (0.11) | <.001 |

| Identify public health and research priorities | 3.41 (0.14) | 3.97 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Design and conduct research | 3.39 (0.13) | 3.77 (0.14) | <.01 |

| Perform data analysis | 3.12 (0.16) | 3.48 (0.17) | <.05 |

| Interpret research findings | 3.36 (0.15) | 3.91 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Apply research findings to interventions and policies | 3.26 (0.16) | 3.85 (0.12) | <.01 |

| Disseminate research findings | 3.02 (0.22) | 3.91 (0.12) | <.001 |

| Evaluate a CBPR partnership | 2.65 (0.18) | 3.76 (0.13) | <.001 |

| Sustain the work of a CBPR partnership | 2.94 (0.17) | 3.73 (0.16) | <.001 |

| Confidence that your partnership, working together, is able to | |||

| Form a CBPR partnership | 3.80 (0.11) | 4.28 (0.13) | <.001 |

| Assess community strengths and dynamics | 3.68 (0.12) | 4.25 (0.13) | <.001 |

| Identify public health and research priorities | 3.74 (0.11) | 4.20 (0.14) | <.01 |

| Design and conduct research | 3.69 (0.14) | 4.14 (0.16) | <.01 |

| Perform data analysis | 3.50 (0.15) | 3.94 (0.18) | <.05 |

| Interpret research findings | 3.64 (0.14) | 4.13 (0.16) | <.01 |

| Apply research findings to interventions and policies | 3.45 (0.13) | 4.25 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Disseminate research findings | 3.35 (0.19) | 4.22 (0.14) | <.001 |

| Evaluate a CBPR partnership | 3.20 (0.14) | 3.91 (0.16) | <.001 |

| Sustain the work of a CBPR partnership | 3.43 (0.14) | 4.02 (0.14) | <.001 |

NOTE: CBPR = community-based participatory research; SE = standard error. Response categories for competence are as follows: 1 = None, 2 = Low, 3 = Moderate, 4 = High, 5 = Extremely high. Response categories for confidence (self- and team-efficacy) are as follows: 1 = Not at all confident, 2 = Slightly, 3 = Moderately, 4 = Very, 5 = Extremely confident.

Enhanced Competence and Confidence in Four Dimensions.

At postprogram only, participants assessed the extent to which their competence and confidence had been enhanced in four key dimensions (not presented in tables). Percentage responding very/extremely enhanced on competence and confidence, respectively, was partnership development (82% competence, 86% confidence); conduct CBPR research (59%, 78%); apply findings to interventions and policies (68%, 69%); and disseminate findings (65%, 75%).

Participant and Overall Program Accomplishments.

Teams reported accomplishments at three months postprogram. Two thirds of teams submitted external grant proposals to advance their partnership and 77% secured funding (15 of 25 proposals submitted). Grants ranged from $5,000 to $1 million, and funders included Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, local government, private foundations, and academic institutional support (e.g., pilot funds, faculty development grants). Partnerships disseminated findings in diverse formats and venues including peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and posters, community gatherings, workshops/trainings, websites, and media interviews.

DISCUSSION, LESSONS LEARNED, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The CBPR Partnership Academy seeks to enhance capacity of academic, public health practitioner, and community partners to use a CBPR approach to achieve health equity. The Partnership Academy shares elements of other successful CBPR capacity-building programs (Allen et al., 2011; Masuda et al., 2011; van Olphen et al., 2015) and is unique in creating a co-learning process in pairs that integrates five components for experiential action learning.

Findings from the first two cohorts demonstrated program effectiveness on multiple dimensions. Participants reported that the in-person course provided a strong foundation by strengthening partner relationships and enhancing CBPR knowledge and confidence.

All learning components were considered beneficial in enhancing CBPR learning except for the first cohort’s use of the online network (ratings improved after changing platforms for the second cohort). Participants were not asked to rank components. Rather, we assessed, for example, whether and how teams integrated feedback from mentors and peers into their local partnership strategies.

Participants gained competence and efficacy (a predictor of success) in all CBPR dimensions. Analysis of pairwise comparisons using pooled data enabled us to demonstrate significant gains across both cohorts, despite small numbers. Partnership development accomplishments (e.g., funding, dissemination) further indicate program success.

In addition to documenting program effectiveness, this evaluation demonstrates the utility of a formative evaluation approach in which results are discussed by the training team, toward refining and improving the program. For example, after discussing relatively low ratings of effectiveness of some teaching materials and interactive exercises in the first year of the course, instructors added a focus on relationship building earlier in the week, enhanced the interactive activities, modified the timing of the Detroit trip, and revised sessions on research designs and statistical analyses to assure relevance to a wider range of participant backgrounds. Following these revisions, ratings and related outcomes improved substantially in the second year.

Our findings show that an integrated, multicomponent program that applies experiential action learning, CBPR, and equity processes is effective at building CBPR partnerships for health and equity. We present lessons learned and practice implications for professional development strategies that equitably link academic researchers, public health practitioners, and community entities to promote health equity.

Create a Team-Based Co-learning Environment

Participating in diverse academic and practitioner/community teams fosters relationships, providing a strong foundation for partnership development. Applying course content to their own partnerships and sharing with others enables co-learning and networking. Academic and community co-instructors with extensive knowledge and adhering to experiential learning principles contribute to a supportive learning environment while modeling equitable relationships.

Begin With an Intensive In-Person Learning Experience

The in-person course formed the foundation for yearlong success. Face-to-face, interactive learning in a diverse group fosters knowledge acquisition and relationships during and outside classroom activities. Opportunities for dialogue and intensive sharing of experiences foster a reflection–action cycle of learning and application consistent with experiential learning principles.

Engage Participants in Integrated Activities to Apply Learning Locally

Providing multiple opportunities over the year to apply new knowledge and skills within a supportive, co-learning environment enhances knowledge and competence. Online technology can reinforce and expand content and enable continued exchange. Strong mentoring provides support and feedback to apply knowledge and skills.

Enroll Diverse Participants to Ensure Richness of Knowledge and Perspectives

A highly diverse group along multiple dimensions brings a richness of knowledge and perspectives and contributes to enhanced problem solving and learning (Gurin, Nagda, & Lopez, 2004). Building a supportive network generates potential for future collaboration toward health equity (Plastrik, Taylor, & Cleveland, 2014).

Limitations

Implementation.

Convening participants across multiple time zones and schedules was logistically challenging, and not all participants attended every activity over the year. Competing time demands made it difficult for some to meet regularly with their partners. Although online technologies enabled distance learning, technical difficulties with the online platforms inhibited full interactive participation.

Assessment.

Frequent evaluation activities were time consuming and labor intensive. The small number of participants limited statistical power for analysis. However, a mixed methods approach that assesses quantitative trends in conjunction with qualitative findings can be effective for evaluating interventions with small numbers. Pooling data may affect the magnitude of change in capacity from pre- to postprogram because of differences in program implementation between the two cohorts.

CONCLUSION

Findings presented here suggest that a community–academic partner-based, integrated, and applied capacity-building program can be effective for developing CBPR partnerships to achieve health equity. Key components of such programs include the opportunity for community and academic teams to work together, with mentoring from experienced trainers as well as peer support. Such opportunities are critical to building a cadre of community, practitioner, and academic researchers with the skills and relationships necessary to conduct effective research and practice, toward the elimination of health inequities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the vital contributions to the work described in this article by all the partner organizations involved in the Detroit Community–Academic Urban Research Center: Community Health and Social Services Center, Inc., Communities in Schools, Detroit Health Department, Detroit Hispanic Development Corporation, Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, Eastside Community Network, Friends of Parkside, Henry Ford Health System, Institute for Population Health, Latino Family Services, Neighborhood Service Organization, and the University of Michigan Schools of Public Health, Social Work and Nursing. All authors have been involved in the Detroit Urban Research Center and/or its affiliated partnerships. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of all CBPR Partnership Academy instructors and mentors (http://www.detroiturc.org/cbpr-partnership-academy-instructors-mentors.html). We also thank Graciela Mentz for statistical analysis and Eliza Wilson-Powers, Katherine Pearson, Lindsay Terhaar, Rachel Varisco, and Julia Weinert for their invaluable assistance. This program is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. 1R25GM111837. Related materials do not necessarily represent views of National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed SM, Maurana C, Nelson D, Meister T, Young SN, & Lucey P (2016). Opening the black box: Conceptualizing community engagement from 109 community-academic partnership programs. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 10, 51–61. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ML, Culhane-Pera KA, Pergament S, & Call KT (2011). A capacity building program to promote CBPR partnerships between academic researchers and community members. Clinical and Translational Science, 4, 428–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00362.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JO, Cox MJ, Newman SD, Gillenwater G, Warner G, Winkler JA, … Slaughter S (2013). Training partnership dyads for community-based participatory research: Strategies and lessons learned from the Community Engaged Scholars program. Health Promotion Practice, 14, 524–533. doi: 10.1177/1524839912461273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Braun KL, Stewart S, Baquet C, Berry-Bobovski L, Blumenthal D, Brandt HM, … Dignan M (2015). The National Cancer Institute’s Community Networks Program Initiative to reduce cancer health disparities: Outcomes and lessons learned. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 2015(9 Suppl), 21–32. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browner E, & Preziosi R (1995). Using experiential learning to improve quality In Van Tiem D, Moseley JL, & Dessinger JC (Eds.), Fundamentals of performance improvement: Optimizing results through people, process, and organizations (pp. 168–174). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Principles of community engagement. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey J, Huff-Davis A, Lindsey C, Norman O, Curtis H, Criner C, & Stewart MK (2017). The development of a community engagement workshop: A community-led approach for building researcher capacity. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 11, 321–329. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2017.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombe C (2012). Participatory approaches to evaluating community organizing and coalition building In Minkler M (Ed.), Community building and community organizing for health and welfare (3rd ed., pp. 346–365). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Bryant AR, Walker DJ, Blumenthal C, Council B, Courtney D, & Adimora A (2015). Building capacity in community-based participatory research partnerships through a focus on process and multiculturalism. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 9, 261–273. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins JB (2012). Participatory evaluation up close: An integration of research-based knowledge. Charlotte, NC: Information Age. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham B (1998). Improving training through action learning (Vol. 1, pp. 219–236). San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbie KM (2008). Competency-to-curriculum toolkit: Developing curriculum for public health workers. Washington, DC: Columbia School of Nursing Center for Health Policy and Association for Prevention Teaching and Research; Retrieved from http://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Competency_to_Curriculum_Toolkit08.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, & Hernandez L (Eds.). (2003). Who will keep the public healthy? Educating public health professionals for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurin P, Nagda B, & Lopez G (2004). The benefits of diversity in education for democratic citizenship. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker E (2013a). Introduction to methods for CBPR for health In Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker E (Eds.), Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed., pp. 3–38). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz A, & Parker E (Eds.). (2013b). Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, McGranaghan R, Allen A, Guzman JR, … Maciak B (2001). The Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center: Development, implementation, and evaluation. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 7(5), 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A, Allen A, Guzman R, & Lichtenstein R (2018). Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 31–46). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D, & Johnson F (2017). Joining together: Group theory and group skills (12th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb D (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda JR, Creighton G, Nixon S, & Frankish J (2011). Building capacity for community-based participatory research for health disparities in Canada: The case of “Partnerships in Community Health Research.” Health Promotion Practice, 12, 280–292. doi: 10.1177/1524839909355520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, & Wallerstein N (Eds.). (2008). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-John G, Fleming C, Ford M, Lichtenberg P, Mangione C, & Pérez-Stable E (2007). Mentoring in community-based participatory research: The RCMAR experience. Ethnicity & Disease, 17(Suppl. 1), S33–S43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plastrik P, Taylor M, & Cleveland J (2014). Connecting to change the world: Harnessing the power of networks for social impact. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Mentz GB, Bernal C, Caver D, DeMajo R, … Woods S (2015). Effectiveness of a walking group intervention to promote physical activity and cardiovascular health in predominantly non-Hispanic black and Hispanic urban neighborhoods: Findings from the Walk Your Heart to Health intervention. Health Education & Behavior, 42, 380–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Wallerstein N, Evans J, McClinton Brown R, Tokunaga J, & Worthen M (2015). A San Francisco Bay Area CBPR training institute: Experiences, curriculum, and lessons learned. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 1, 203–212. doi: 10.1177/2373379915596350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, … Whitener L (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary), 2004(99), 1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.). (2018). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins N, Parajon LC, Coombe CM, Duldulao AA, Garcia LR, & Wang P (2018). Participatory evaluation as a process of empowerment: Experiences with community health workers in the United States and Latin America In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 251–264). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Zittleman L, Wright L, Barrientos Ortiz C, Fleming C, Loudhawk-Hedgepeth C, Marshall J, … Westfall JM (2014). Colorado Immersion Training in Community Engagement Because you can’t study what you don’t know. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 8, 117–124. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]