Abstract

Urinary tract infections are second most important diseases worldwide due to the increased amount of antibiotic resistant microbes. Among the Gram negative bacteria, P. mirabilis is the dominant biofilm producer in urinary tract infections next to E. coli. Biofilm is a process that produced self-matrix of more virulence pathogens on colloidal surfaces. Based on the above fact, this study was concentrated to inhibit the P. mirabilis biofilm formation by various in-vitro experiments. In the current study, the anti-biofilm effect of essential oils was recovered from the medicinal plant of Solanum nigrum, and confirmed the available essential oils by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy analysis. The excellent anti-microbial activity and minimum biofilm inhibition concentration of the essential oils against P. mirabilis was indicated at 200 µg/mL. The absence of viability and altered exopolysaccharide structure of treated cells were showed by biofilm metabolic assay and phenol–sulphuric acid method. The fluorescence differentiation of P. mirabilis treated cells was showed with more damages by confocal laser scanning electron microscope. Further, more morphological changes of essential oils treated cells were differentiated from normal cells by scanning electron microscope. Altogether, the results were reported that the S. nigrum essential oils have anti-biofilm ability.

Keywords: Solanum nigrum, Essential oils, Biofilm, Viability of cells, Intracellular changes, Exopolysaccharide

1. Introduction

Recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most frequent infectious diseases to human beings, which caused by overuse of frequent antibiotics consumption (Michael et al., 2015). Worldwide, every person has suffered by UTIs at least one time in their life, and 10% of the women got recurrent UTIs (Nabakishore et al., 2014). Most of the UTIs are caused by enterobacteriaceae with multi drug resistance (MDRs) ability. Among the enterobacteriaceae, the topmost pathogen is E. coli and second most bacteria is P. mirabilis, both are covered almost 90% of complicated UTIs (Jarratt and Miller, 2013). In particular, the P. mirabilis caused UTIs are very important, because it connected with all the UTIs parts and make abnormalities and long term catheterized infections (Mohammad Reza et al., 2019). The unnecessary dosage of drug and antibiotic consumption lead to persistent the development of resistance in P. mirabilis (Mehri et al., 2015). Those extracellular leakages are affecting the beta lactam ring due to the beta lactamases enzyme production (Dhanasekaran et al., 2019, Rajivgandhi et al., 2014). Importantly, P. mirabilis has more virulence factors including MR/P fimbriae, cell signaling factors of QS, enzymes of ESBLs and carbapenemases, which are responsible for frequent development of recurrent and continuous catheterization due to the antibiotic denature (Jarratt and Miller, 2013). Among the different virulence factors, the biofilm formation is a major virulence factors in P. mirabilis causing UTIs. The biofilm formed P. mirabilis has critical roles in UTIs and make MDRs and recurrent infections to current antibiotics.

The punches of clumped microbes covered into the self-produced extracellular polymeric materials are considered as a biofilm (Fallah et al., 2017). It adhered on inherent or non-inherent surfaces with the coating model of different protein, polysaccharides, nucleic acid and various lipids (Sahar et al., 2019). The formation of biofilm is depending on the presence of environments, when the favorable environment comes, the bacteria produced signaling molecules and connect each other, finally form biofilm. It is one of the chains like process, which always successful finisher against external antibiotics (Didem et al., 2020, Jombo et al., 2012). The surface antigen is altered frequently and produced gene expression of continuous resistant development in immune system (Sabir et al., 2017, Daniel et al., 2016). The Centre for Disease Control (CDC) society was reported that the 60% of death rate is documented from biofilm producing MDRs (Rajivgandhi et al., 2018a). Approximately, 20, 0000 deaths are reported from biofilm affected patients and it is a major economic impact on health services. In this condition, the bacteria in inside of the biofilm is acted as a phagocytes role and leads to suppress the host immune system and antimicrobial chemotherapy (Vasantha Packiavathy et al., 2014). Sometimes, the biofilm formation was mediated by important virulence factor of QS, which is used to formation of microorganisms each other through cell signaling molecules. Therefore, the new variety of antibiotic production is needed urgently to eradicate biofilm forming pathogens with alternative strategies (Ramadevi et al., 2020). Based on the above facts, recent years plant essential oils (Eos) was concentrated to biofilm inhibition studies by various researchers (Hossain et al., 2014, Garcia and Spitzer, 2017).

The S. nigrum is a medicinal plant which available in entire world including temporal and tropical regions, and several countries including Saudi Arabia (Migahid, 1996). It is used in various biomedical fields due to the extraordinary medicinal properties. In particular, morethan 100 years it is frequently used in cancer treatment and reported by many researchers (Razali et al., 2016, Murungi et al., 2013). It is frequently strengthening the traditional value and believes that this S. nigrum has excess biomedicine properties like antimicrobial, antiviral, larvicidal, anti-oxidant and anti-cancer (Jeong et al., 2010). It directly involved in the DNA damages in bacteria, fungus and viruses. Also, the most favorable MCF-7 inhibitor compound of 12-O-Tetradecene-noylphorbol-13-acetate is reported from plant of S. nigrum (Razali et al., (2016). Consecutively, the essential oils of S. nigrum also have several biomedical activities including anti-oxidant, anti-biofilm, anti-microbial and anti-cancer activities (Mallika and Chennam Srinivasulu, 2006, Razali et al., 2016, Murungi et al., 2013, Ibanez and Blazquez, 2020). It has more polysachharide derivatives and simply called as black nightshade. Also, it is a short live plant, which given more biomedical properties in their short period. The seeds of S. nigrum have excellent antimicrobial, anti-biofilm and anti-cancer activity. It is extensively use in traditional medicine in India and also other countries (Wu-Ching et al., 2018). It is a well-known plant that frequently used in Indian homes for inflammation, pain, fever, jaundice, eye infections and some other common infections. Therefore, we have chosen S. nigrum for this study to inhibit biofilm producing P. mirabilis.

2. Materials method

2.1. Extraction and purification of EO

For the Eos extraction, we have followed the standard hydro distillation method using Clevenger apparatus as a container (Xinjun et al., 2020). The plant seeds were collected from inside of the Bharathidasan University garden, Tamil Nadu, India. For the undisturbed seeds, initially washed with dist·H2O and followed by double Dist·H2O and put on shade condition at room atmosphere with 15 days. After incubation, used seeds were grinded clearly and put it in hydro distillation using solvent n-hexane. In 1L water, 50 g of topped sample was dissolved and maintained at 3–4 h distillation. Next, the EOs were collected and used in sodium sulfate for dry. Finally, the solution was filtered the EOs except n-hexane under reduced pressure.

2.2. LC-MS analysis of EOs

The complete available components in the extracted EOs were identified by LC-MS with the modification of previous report of Digambar et al. (2019). Shortly, 1:1% of sample and dichloromethane were used for injection, 70Ev of EI mode with 1: 20 split ratio (Himedia, India) combined with split injector at 240 ℃. For chemical components separation, the 5%+95% of phenyl and dimethylpolysiloxane was used in the 40 m × 0.45 mm × 0.25 μm of HP-5MS were performed. In addition, the helium gas of 1 mL/min with initial and final temperature of 40 ℃ and 250 ℃ were used respectively. The oven temperature should be set as 4 ℃. Lastly, the injected volume of EO was mixed in the solvent of chloroform at the ratio of 1:10 in μl concentration. Then, the available phytochemical, secondary metabolites, growth hormones are scanned and done the process. The obtained result was compared with NIST library of Bharathidasan University, Tamil Nadu, India.

2.3. Antimicrobial activity of EOs

Increased antimicrobial activity of extracted SNEOs against biofilm forming P. mirabilis was initially confirmed by agar well diffusion method (Augustine et al., 2020). The one day old culture of biofilm forming P. mirabilis was swabbed on muller hinton agar plate without any mistakes. Then, 6 mm of the wells were cut into the agar plates, and followed by added SNEOs till inhibition level of concentration. In addition, for the MDRs effect confirmation, the disc antibiotic model of ceftazidime was put on the agar surface. Also, D·H2O added well performed for negative control. The plate was put it in room with normal temperature for 1 day. Then, the zones of inhibition around the tested wells were noted next day and detect the SNEOs range of effect against biofilm producing P. mirabilis.

2.4. Minimum biofilm inhibition concentration

Aliquot the one day old biofilm forming P. mirabilis broth into the 24-well polystyrene plate of before added sterile nutrient broth and followed by different inhibition concentration level of SNEOs, specifically used at 10–100 μg/mL concentration (Rajivgandhi et al., 2018b). After added the respective concentration of SNEOs, the wells were mixed thoroughly and the plate was maintained one day at room temperature. After one day, the plate was taken and find the turbidity of biofilm growth and compared with untreated well of the non-turbidity wells for biofilm layer. Next, the confirmed samples were allowed to take O.D values by UV-spectrometer in 600 nm and noted. Then all the values were converted to percentages after calculation with control value. The percentages of calculated triplicated value was based on the universal formula,

| (1) |

2.5. Detection of metabolic activity

Based on the viability of SNEOs with 10–100 μg/mL concentration treated biofilm forming P. mirabilis in the 24-well plate was identified with the help of 2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)–2H-tetrazolium-5- carboxanilide (XTT) solution. This experiment was followed by previous evidenced report of Maruthupandy et al. (2020), and adherent biofilm cells were treated with 1 mL of XTT was added into the treated and untreated 24-well plate. After 30 min time interval, menadione acetone solution (suggested by CLSI) was added into the wells with the presence of 100 μL phosphate buffer saline. Shaken well gently and allowed to maintain in normal room temperature for one hour. As same as without menadione acetone solution well is control. Finally, the changed and unchanged formation of the wells was measured using microtitre plate reader at 600 nm. The triplicated result was converted to inhibition percentage using bellowed equation,

| (2) |

2.6. Identification of exopolysaccharide modification

The universal solvent of phenol–sulfuric acid was used to detect the biofilm forming P. mirabilis EPS damages after addition of SNEOs with the help of earlier evidenced slightly modified procedure (Rajivgandhi et al., 2020). The biofilm forming P. mirabilis was initially treated by BIC of SNEOs and followed by centrifugation with 3000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in saline for enzyme degradation and treated with pronase E (25 μL), followed vortex at 50 °C with 5 min. Ice precipitated protein treated trichloroacetic acid was inoculated into the reaction mixture, volume is 100 μL. Then, again centrifuged with celling temperature at 4000 rpm for 5 min and diluted by cold absolute alcohol, volume 10 mL in drop wise to precipitate the polysaccharide. The reaction mixture was put in −20 ℃ for 12 h and then centrifuged properly for polysaccharides collection. Then using double distilled water to resuspension of the sample and digested with 98% of sulphuric acid (5 mL) and vortexed. After, the reaction mixture sample was kept in water bath 15 min and cooled on ice pack. Finally, the sample was measure using spectrophotometer at 600 nm with the standard glucose and blank distilled water. The triplicated vales were converted to percentages using universal formula,

| (3) |

Further, the CRA method is an excellent method to detect the presence and absence of exopolysaccharide visibly. The final mixture solution was aliquot on the CRA medium by quadrant streaking method with 1 day. After one day, based on the presence and absence of black color, reduced black color of the tested biofilm forming P. mirabilis was interpreted for result (Xinjun et al., 2020).

2.7. Live/dead damage of SNEOs effect by CLSM

The fluorescence dyes of AO/EB combination were used to detect the mortality of SNEOs treated cells compared with untreated cells by CLSM with the previous reported article of Maruthupandy et al. (2020). The BIC treated biofilm forming P. mirabilis was grown on 6-well plated containing cover glass for one day. The well grown cells of the cover slip were taken and washed using 45 of crystal violet degradation dye. After attachment of crystal violet, the cover slip was washed properly with phosphate buffer saline and double distilled water twice for excess dye removal. Then, the cover slip was put in dark room 10 min and maintained black cover rolling for purity. Finally, the cover slip containing sample was viewed by CLSM through inverted position and mortality of cells were clearly viewed and compared with control.

2.8. Morphological modification of SNEOs

The size and shape of the biofilm forming P. mirabilis was morphologically viewed after treatment with SNEOs by SEM (da Silva et al., 2019). The pellet of BIC treated biofilm forming P. mirabilis was recovered at 2,500 rpm for 5 min. After discard the supernatant, the pellet was washed twice with phosphate buffer saline and distilled water. After drying, the 10 µL of the sample was aliquot on cover galss and fixed by 4% formaldehyde solution for 3 h. Then, washed with phosphate buffer saline and water for unfixed cells. Next, performed the ethanol gradient serious degradation using 10–100% of ethanol series. Next, the t-butanol was added after drying the cover slip to maintain the live condition of bacteria. Finally, the t-butanol treated sample was maintained in deep freezer one day. After, the cover glass was coated with copper grid and viewed by SEM for damage and undamage differentiation.

3. Result

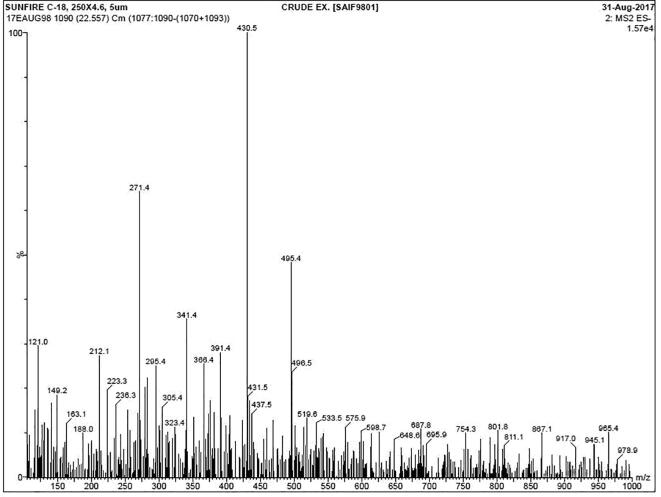

3.1. Complete chemical composition of SNEOs by LC-MS analysis

After successful completion of LC-MS, the result was shown with more essential oils, proteins, amino acids, growth hormones and phytochemical derivatives. Among these, we have separated the EOs for this study. After screening, the 18 different essential oil compounds were identified based on the RT, % of area and occupation, % of occupation. In result, the terpenes was contain very high rate and supported by monoterpenes and hydrocarbons with sesquiterpenes derivatives (Fig. 1). Based on the highest RT, the EOs of β-Pinene, α-pinene, α-terpineol, β-pinene, Thymol, borneol, 2-Thujene, Myrcene, Octanone and Sabinene was highly correlated. Also, respective occupation area and occupation percentages were noted including 30.23, 28.16, 10.15, 20.40, 18.10, 30.10, 12.10, 10.02, 8.20, 9.10. Finally, the result was exhibited that the more EOs was present in the SNEOs. The present result was good agreement with earlier reports Razali et al., 2016, Ibanez and Blazquez, 2020, and the presence of EOs was changed by region to region due to the various environmental factors. Sometimes, the genetic factors are influenced to produce native EOS in plant and it also has more biological properties (Jeong et al., 2010). Recently, the researcher was reported that the medicinal plant mediated EOs has the ability to modify the virulence factor inhibition due to the stimulation of growth hormones (da Silva et al., 2019). The similar result was reported by Mallika and Chennam Srinivasulu (2006), and medicinal plant of EOs has improved antimicrobial activity against MDRs bacteria. The unfavorable environmental condition, temperature, pH, carbon, nitrogen sources, NaCl content, humidity and various other stresses also influenced the native effect of EOs against various infections. Based on the above facts were suggested that the LC-MS was excellent analytical tool for identify the available EOs compounds in purified sample and it proved that the SNEOs has more antimicrobial derivatives of phytochemical compounds.

Fig. 1.

LC-MS analysis of plant Solanum nigrum for detection of available chemical composition of essential oils.

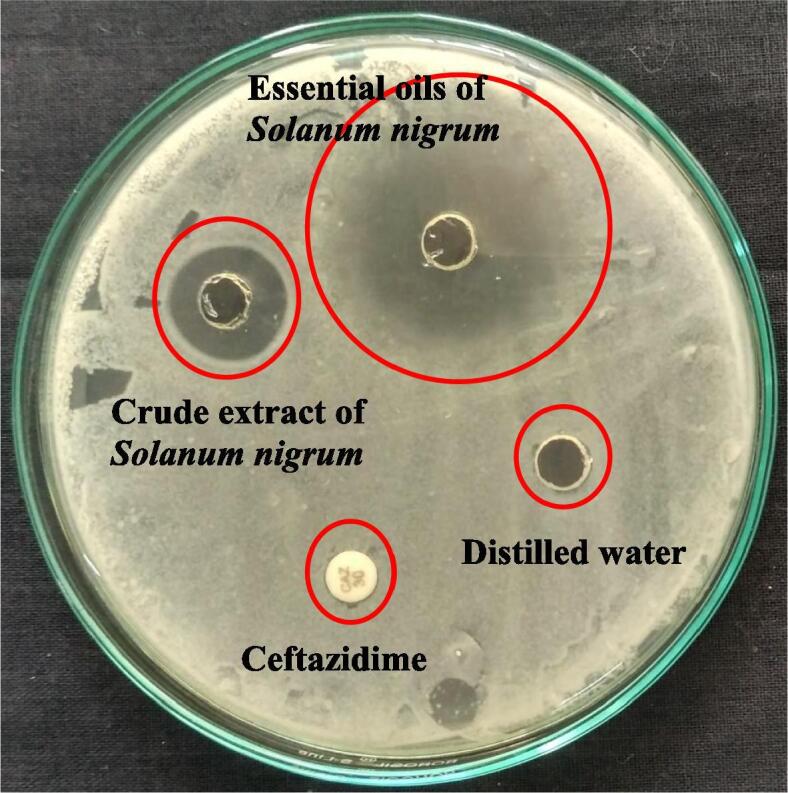

3.2. Anti-microbial activity of SNEOs

The improved effect of SNEOs treated biofilm forming P. mirabilis was shown 32 mm zone of inhibition at 100 µg/mL concentration was observed after one day incubation. In addition, the same plate containing normal crude extract of SN was showed with 16 mm zone of inhibition against P. mirabilis was observed. Whereas, the positive control and distilled water containing wells were showed with no zone of inhibition against P. mirabilis. This result was suggested that the SNEOs were very effective against biofilm forming P. mirabilis at very least concentration of 200 µg/mL (Fig. 2). At the same concentration, the crude extract of the SN was showed very low zone of inhibition compare with SNEOs. In addition, the no zone of inhibition result of ceftazidime antibiotic was revealed that the pathogen was MDRs effect, and the no zone of inhibition around the distilled water added well was proved that the dilution was not influenced in SNEOs. The zone was arisen from original SNEOs effective. The good agreement result was documented by Balakumar et al. (2011), and the medicinal plant mediated EOs has excellent anti-microbial activity against MDRs strains. Recently, Ramachandran et al. (2020) reported that the EOs rich plant compound very effective inhibition in inside of the bacteria (Rana et al., 1997). The damaged essential oil treated plant Cyperus articulatus shown excellent zone of inhibition against food pathogens at increasing concentration (Kavaz et al., 2019). Therefore, our result was proved that the SNEOs were effective anti-biofilm agent against P. mirabilis.

Fig. 2.

Anti-microbial activity differentiation of Solanum nigrum extract and essential oils against biofilm producing P. mirabilis by agar well diffusion method.

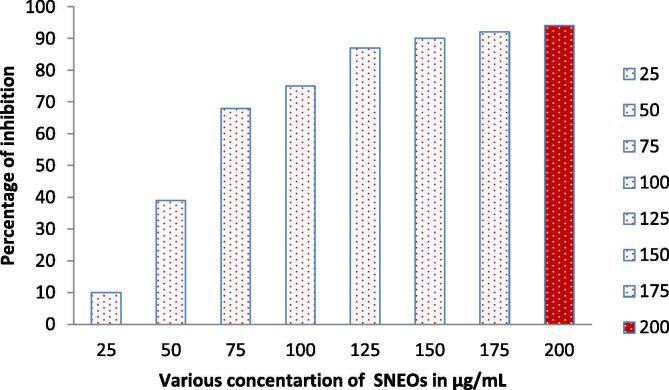

3.3. Minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) of SNEOs

In 200 µg/mL concentration, the MIC was showed with more turbidity in SNEOs treated well compared with other wells. It confirmed that the SNEOs are very effective against P. mirabilis at 200 µg/mL (Fig. 3). The O.D values of treated and untreated results were converted to percentage of inhibition with triplicate value as 94%. Initially, the inhibition was started at only 25 µg/mL only. When we added increased concentration, the turbidity also increased and it declared, the SNEOs are concentration dependent inhibitor. But, compared with previous reports, the concentration was very low (Xinjun et al., 2020). The half inhibition percentage was identified in 60 µg/mL concentration. Previously, the SNEOs against tested various bacteria was reported at higher concentration (da Silva et al., 2019, Lin et al., 2019). Based on the MIC, the result was confirmed that the SNEOs have anti-biofilm effect at minimum concentration and this 200 µg/mL was finalized as a biofilm inhibition concentration (BIC). This BIC was used for all invitro inhibition studies.

Fig. 3.

Minimum inhibition concentration of Solanum nigrum essential oils against biofilm producing P. mirabilis by microbroth dilution method.

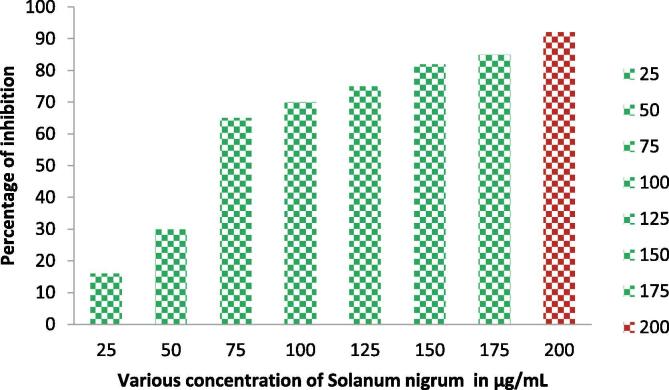

3.4. Detection of metabolic activity

The decreased bacterial cell survival of SNEOs treated P. mirabilis culture evidently indicated to in the 24-well plate culture. In biofilm inhibition research, the bacterial survival rate is essential step to detect the bacterial activity. Mechanically it was evident research, because all the virulence factors including enzyme production, ROS formation, QS production and specific gene activation were stopped their native role and inability to produce next molecules. So, the bacteria automatically lost their virulence in inside of the body (Maruthupandy et al., 2020, Ying et al., 2018). In our study, deactivated survival rate of SNEOs treated P. mirabilis was indicated at 200 µg/mL with 92%. Before, the initial deactivated survival rate was indicated in 10% and extended up to with 92% of inhibition (Fig. 4). This result was evidently proved that the SNEOs was deactivated the bacterial survival in liquid nutrient media culture and it confirmed after OD. Result of spectrophotometer reading. The XTT result was clearly indicated that the SNEOs have the deactivated survival ability of P. mirabilis in liquid media. This result was most accordance with previous invitro result and the inhibition concentration as equal to BIC result. In good agreement result of Milica et al. (2020) reported that the reduced survival rate of biofilm forming gram negative bacteria was identified after lost their pathogenicity. In addition, recent report of Kamila et al. (2016), the viability based XTT assay is a perfect method to identified the tested materials nature. When the SNEOs don’t have inhibition ability, the survival rate of biofilm forming pathogen remains in same or increased. Therefore, our result was agreed the above said statement and clearly interpreted as the SNEOs as effective anti-biofilm agent against tested biofilm forming P. mirabilis.

Fig. 4.

Metabolic biofilm activity of Solanum nigrum essential oils against biofilm producing P. mirabilis by XTT method.

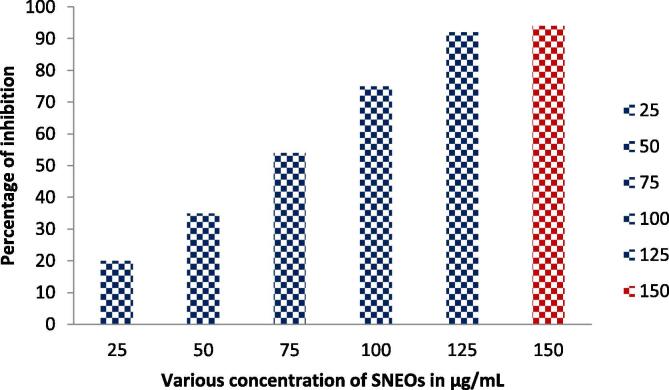

3.5. Measurement of EPS modification

The inhibition of physical barrier in bacteria as EPS was final confirmation result for biofilm inhibition. If the bacteria have the ability to form biofilm, initially it developed the fence against foreign drugs and antibiotics. Also, it extended their role into the nucleic acid and damaged the cells frequently. It leads to bacterial suppression, membrane damages, and intracellular granules leakages (Banu et al., 2018). EPS has rich polysachharides and helped to form a ring around the bacterial DNA, nucleic acid, and other cell wall degraded materials within the bacteria and produce the sensitive enzymes and proteins against external drugs and antibiotics (Dipti Mayee et al., 2020). Previously, Maruthupandy et al. (2020) reported that the EPS is given size and shape for bacterial biofilm formation and it leads to biofilm matrix formation. Based on these concerns, we have targeted the EPS in our study using SNEOs. The result of actual degradation effect in EPS was 94% at the 250 μg/mL concentration (Fig. 5). The result was stated that the total virulence factors of P. mirabilis were lost due to the influence of in SNEOs treatment. The SNEOS penetrated into the P. mirabilis through cell wall and damaged the fimbriae, flagella and slime responsible proteins, and extended to intracellular organelles leads to DNA, nucleic acid damages. Capsular polysachharides mediated inhibition was very effective in biofilm formation (da Silva et al., 2019). The EPS inhibition mechanism was successfully correlated to previous reports of Xinjun et al. (2020). EPS inhibition is an essential key factor to destroy the cells completely within the biofilm matrix and extended target sites.

Fig. 5.

EPS degradation of Solanum nigrum essential oils against biofilm producing P. mirabilis by phenol–sulphuric acid method.

The invitro EPS arrest method was validated by CRA plate method, and suggested that the SNEOs has anti-biofilm ability. Initially, the black color of the CRA plate was indicated as EPS production, later the black color of its pathogenicity was hide step by step using increasing concentration. At 250 μg/mL concentration, the black color colonies were completely arrested and it exhibited pink color colonies. The result was proved that the SNEOs have virulence factors inhibition. Because, it arrested the black color of pathogenicity in P. mirabilis, but the antigenicity was still present in inside of the bacteria due to the production of pink color. At the same concentration, the bacteria P. mirabilis was lost their replication, nucleic acid synthesis and other responsible factors of virulence factors. Finally, the result was strongly agreed the invitro EPS inhibition study and it suggested SNEOs has anti-biofilm ability against P. mirabilis.

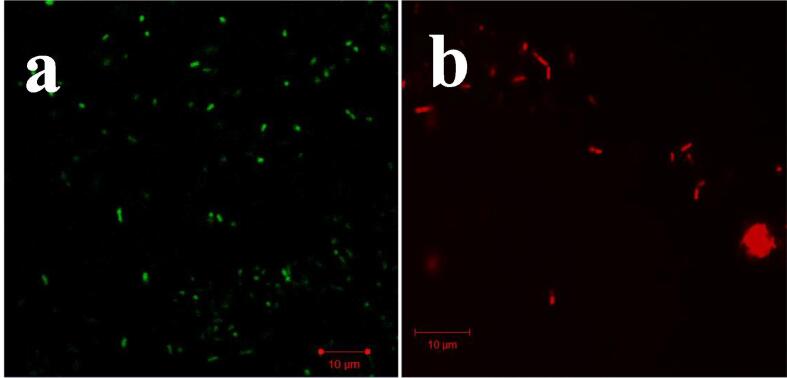

3.6. Live/dead damage of SNEOs effect by CLSM

The intracellular death of the SNEOs treated P. mirabilis was effectively viewed at the 40x magnification of CLSM. The BIC treated P. mirabilis was shown with increased cell death compared with untreated P. mirabilis. AO/EB is a fluorescence dyes that used to bind with treated or untreated bacterial cells intracellular. In our result, the dye of AO/EB was entered into the bacterial cells and bind into intracellularly, and it glows on green colored emitted cells only as suggested untreated control (Fig. 6a). Whereas, the above said procedure of treated cells were glowed with red color cells as suggested as treated cells (Fig. 6b). The bacteria with rough surface, condensed structure and irregular shape of the P. mirabilis were seen at 200 μg/mL concentration of treated cells image. Instead, the smooth surface, normal bacterial structure with regular rod shape of the P. mirabilis was seen in untreated cells image. Therefore, the result was notified, the plant SNEOs has intracellular inhibition ability at 200 μg/mL concentration against biofilm forming P. mirabilis. The previous statement was supported to our result, and the intracellular damage differentiation was identified by AO/EB fluorescence dye (Maruthupandy et al., 2020). Previously, the green color and red color differentiation of treated and untreated bacterial cells were shown by CLSM as a confirmation method for bacterial damage intracellularly (da Silva et al., 2019). In addition, this result was supported to evidence of BIC, EPS, XTT assay result and the BIC concentration was very effective against biofilm forming P. mirabilis.

Fig. 6.

Live/dead variation of control (a) and Solanum nigrum essential oils treated (b) P. mirabilis by CLSM.

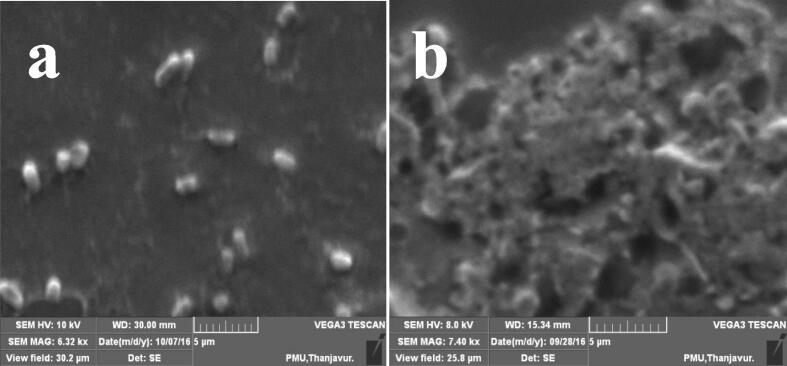

3.7. Morphological treatment of SNEOs

Weather the morphology and cell wall damages in the SNEOs treated P. mirabilis was evidently proved by SEM. In SEM, the fixed cells were degraded by ethanol gradient series with degradation (Fig. 7). In this step, the adherent bacteria were utilized the ethanol and anchored the cover slip tightly in live condition. Consecutively, the death cells were abolished by washing with phosphate buffer saline and distilled water (Wang et al., 2019). After t-butanol treatment, the cells were clumped each other and exhibited native structure (Lindsay et al., 2019). Followed statement, the exhibited SNEOs treated P. mirabilis was showed more morphological and cell wall damages by SEM. The continuous development of belbing and shape modification was indicated as SNEOs effect (Cansu Feyzioglu and Tornuk, 2016). In treated cells morphology was showed with some leakages material compared with smooth rod shape of the P. mirabilis. In some places, the rod shape was changed and shown irregular morphology. In addition, the SNEOs attached cells morphology was shown with clumps of SNEOs and complete damages. Therefore, the SEM result was morphologically supported to CLSM and suggested that the P. mirabilis was inhibited by SNEOs at their respective BIC.

Fig. 7.

Morphological modification of control (a) and Solanum nigrum essential oils treated (b) P. mirabilis by SEM.

4. Conclusion

After careful consideration with agar well diffusion and invitro experiments, the plant SNEOs has increased anti-biofilm activity against biofilm forming P. mirabilis effectively. At 200 μg/mL of BIC, the bacteria were sensitive to SNEOs and lost their virulence factors. Initially, the anti-biofilm ability was proved by agar well diffusion method and BIC. In addition, the deactivation of bacterial survival and damaged biofilm structure arrangement was proved by XTT and EPS measurement experiments respectively. The microscopicy studies of intracellular and morphological modifications in the presence of SNEOs containing P. mirabilis was showed by CLSM and SEM. Therefore, all the invitro experiment results were strongly supported that the SNEOs as a promising anit-biofilm agent against Gram negative bacteria, particularly for P. mirabilis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number IFKSURG-1438-091.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Michael O., Sarah L.M., Aaron Z.W., Damon P.E. Urinary tract infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- producing Gram-negative bacteria: identification of risk factors and outcome predictors in an Australian tertiary referral hospital. Int. J. of Inf. Dis. 2015;34:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak N., Lenka R.K., Padhy R.N. Surveillance of multidrug resistant suppurative infection causing bacteria in hospitalized patients in an Indian tertiary care hospital. J. Acute Dis. 2014;3(2):148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jarratt L.S., Miller M.P.H. The relationship between patient characteristics and the development of a multi-resistant healthcare-associated infection in a private South Australian hospital. Healthc. Inf. 2013;18:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi Karam M.R., Habibi M., Bouzari S. Urinary tract infection: Pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance and development of effective vaccines against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Immunol. 2019;108:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehri H., Mohammad Reza A.K., Saeid B. Evaluation of the effect of MPL and delivery route on immunogenicity and protectivity of different formulations of FimH and MrpH from uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis in a UTI mousemodel. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015;28:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran S., Rajesh A., Mathimani T., Melvin Samuel S., Shanmuganathan R., Brindhadevi K. Efficacy of crude extracts of Clitoria ternatea for antibacterial activity against gram negative bacterium (Proteus mirabilis) Biocatal. Agricult. Biotechnol. 2019;21 [Google Scholar]

- Rajivgandhi G., Vijayarani J., Kannan M., Murugan A., Vijayan R., Manoharan N. Isolation and identification of biofilm forming uropathogens from urinary tract infection and its antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. Int. J. Adv. Lif. Sci. 2014;7:352–363. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah F., Yousefi M., Pourmand M.R., Hashemi A., Nazari Alam A., Afshar D. Phenotypic and genotypic study of biofilm formation in Enterococci isolated from urinary tract infections. Microb. Pathog. 2017;108:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahar Z., Saba H., Hammad A., Rani F. Emergence of hypervirulent K. pneumoniae causing complicated UTI in kidney stone patients. Microb. Pathog. 2019;135 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didem K., Samiye Y.C., Emirhan N. Altered metabolomic profile of dual-species biofilm: Interactions between Proteus mirabilis and Candida albicans. Microbiolog. Res. 2020;230 doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2019.126346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombo G.T.A., Emanghe U.E., Amefule E.N., Damen J.G. Nosocomial and community acquired uropathogenic isolates of Proteus mirabilis and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles at a university hospital in Sub–Saharan Africa. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Dis. 2012;2(1):7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sabir Nargis, Ikram Aamer, Zaman Gohar, Satti Luqman, Gardezi Adeel, Ahmed Abeera, Ahmed Parvez. Bacterial biofilm-based catheter-associated urinary tract infections: Causative pathogens and antibiotic resistance. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2017;45(10):1101–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J.W., Makrina T., Luke P.A., Richard I.W., Danilo G.M., Mark A.S. Comparative proteomics of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during growth in human urine identify UCA-like (UCL) fimbriae as an adherence factor involved in biofilm formation and binding to uroepithelial cells. J. Proteom. 2016;131:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajivgandhi Govindan, Vijayan Ramachandran, Maruthupandy Muthuchamy, Vaseeharan Baskaralingam, Manoharan Natesan. Antibiofilm effect of Nocardiopsis sp. GRG 1 (KT235640) compound against biofilm forming Gram negative bacteria on UTIs. Microb. Pathog. 2018;118:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasantha Packiavathy I.A.S., Priya S., Karutha Pandian S., Veera Ravi A. Inhibition of biofilm development of uropathogens by curcumin – An anti-quorum sensing agent from Curcuma longa. Food Chem. 2014;148:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadevi S., Kaleeswaran B., Ilavenil S., Upgade Akilesh, Tamilvendan D., Rajakrishnan R., Alfarhan A.H., Kim Y.-O., Kim H.-J. Effect of traditionally used herb Pedalium murex L. and its active compound pedalitin on urease expression – For the management of kidney stone. Saudi J. Biolog. Sci. 2020;27(3):833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain Muhammad Delowar, Ahsan Sunjukta, Kabir Md. Shahidul. Antibiotic resistance patterns of uropathogens isolated from catheterized and noncatheterized patients in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2014;26(3):127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Robert, Spitzer Eric D. Promoting appropriate urine culture management to improve health care outcomes and the accuracy of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2017;45(10):1143–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razali F.N., Sinniah S.K., Hussin H., Abidin N.Z., Suriza Shui A. Tumor suppression effect of Solanum nigrum polysaccharide fractionon Breast cancer via immunomodulation. Int. J. Biolog. Macromol. 2016;92:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murungi Lucy K., Kirwa Hillary, Torto Baldwyn. Differences in essential oil content of berries and leaves of Solanum sarrachoides (Solanaceae) and the effects on oviposition of the tomato spider mite (Tetranychus evansi) Indus. Crops Products. 2013;46:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Jin Boo, De Lumen Ben O., Jeong Hyung Jin. Lunasin peptide purified from Solanum nigrum L. protects DNA from oxidative damage by suppressing the generation of hydroxyl radical via blocking fenton reaction. Cancer Lett. 2010;293(1):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallika J., Chennam Srinivasulu S.D. Antiulcerogenic and ulcer healing effects of Solanum nigrum (L.) on experimental ulcer models: Possible mechanism for the inhibition of acid formation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;104:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez M.D., Blazquez M.A. Phytotoxic effects of commercial essential oils on selected vegetable crops: Cucumber and tomato. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020;15 [Google Scholar]

- Uen Wu-Ching, Lee Bao-Hong, Shi Yeu-Ching, Wu She-Ching, Tai Chen-Jei, Tai Cheng-Jeng. Inhibition of aqueous extracts of Solanum nigrum (AESN) on oral cancer through regulation of mitochondrial fission. J. Tradition. Complement. Med. 2018;8(1):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xinjun Y., Govindan Nadar R., Govindan R., Naiyf S.A., Shine K., Jamal M.K., Taghreed N.A., Natesan M., Rajan Viji. Preparative HPLC fraction of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis essential oil against biofilm forming Klebsiella pneumonia. Saudi J. Biolog. Sci. 2020;27:2853–2862. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digambar S.P., Jyoti G., Sahera N. Antimicrobial activity and HR-LCMS analysis of methanolic extract of Calotropis gigantea. Int. J. Advan. Sci. Res. 2019;4:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Amalraj Augustine, Haponiuk Józef T., Thomas Sabu, Gopi Sreeraj. Preparation, characterization and antimicrobial activity of polyvinyl alcohol/gum arabic/chitosan composite films incorporated with black pepper essential oil and ginger essential oil. Int. J. Biolog. Macromol. 2020;151:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.02.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajivgandhi G., Senthil R., Ramachandran G., Maruthupandy M., Manoharan N. Antibiofilm activity of marine endophytic actinomycetes compound isolated from mangrove plant Rhizophora mucronata, Muthupet Mangrove Region, Tamil Nadu. India. J. Terr. Mar. Res. 2018;2:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Migahid, A.M., 1996. Flora of Saudi Arabia. University Libraries, King Saud University. 4th edition.

- Maruthupandy M., Rajivgandhi G., Kadaikunnan S., Veeramani T., Alharbi N.S., Muneeswaran T.M., Khaled J., Wen Jun F., Alanzi K. Anti-biofilm investigation of graphene/chitosan nanocomposites against biofilm producing P. aeruginosa and K. pneumonia. Carbohyd. Polym. 2020;230 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajivgandhi G.N., Ramachandran G., Maruthupandy M., Manoharan N., Naiyf S.A., Shine K., Jamal M.K., Taghreed N.A., Wen-Jun L. Anti-oxidant, anti-bacterial and anti-biofilm activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Gracilaria corticata against biofilm producing K. pneumonia. Colloids and Surf. A: Physicochem. Engin. Aspect. 2020;600 [Google Scholar]

- da Silva P.M., da Silva B.R., de Oliveira Silva J.N., de Moura M., Soares C.T., Feitosa A.P.S., Brayner F.A., Alves L.C., Paiva P.M.G., Damborg P., Ingmer H., Napoleao T.H. Punica granatum sarcotesa lectin (PgTeL) has antibacterial activity and synergistic effects with antibiotics against β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;135:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran G., Rajivgandhi G.N., Murugan S., Alharbi N.S., Kadaikunnan S., Khaled J.M., Almanaa T.N., Manoharan N., Wen-Jun L. Anti-carbapenamase activity of Camellia japonica essential oil against isolated carbapenem resistant klebsiella pneumoniae (MN396685) Saud. J. Biolog. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar S., Rajan S., Thirunalasundari T., Jeeva S. Antifungal activity of Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa (Rutaceae) leaf extract on dermatophytes, Asian Pac. J Trop. Biomed. 2011;4:309–312. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(11)60049-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana B.K., Singh U.P., Taneja V. Antifungal activity and kinetics of inhibition by essential oil isolated from leaves of Aegle marmelos. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1997;57:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaz D., Idris M., Onyebuchi C. Physiochemical characterization, antioxidative, anticancer cells proliferation and food pathogens antibacterial activity of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with Cyperus articulatus rhizome essential oils. Int. J. Biolog. Macromol. 2019;123:837–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Lin, Mao Xuefang, Sun Yanhui, Rajivgandhi Govindan, Cui Haiying. Antibacterial properties of nanofibers containing chrysanthemum essential oil and their application as beef packaging. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019;292:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z., Jie K., Yunfei X., Yahui G., Yuliang C., He Q., Weirong Y. Essential oil components inhibit biofilm formation in Erwinia carotovora and Pseudomonas fluorescens via anti-quorum sensing activity. LWT. 2018;92:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Milica P., Zorica S.R., Marija G., Marina D., Niko R. Anti-virulence potential of basil and sage essential oils: Inhibition of biofilm formation, motility and pyocyanin production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;141 doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamila M., Marcin T.S., Małgorzata M., Wojciech J., Mariola O., Katarzyna C. Inhibition of quorum sensing-related biofilm of Pseudomonas fluorescens KM121 by Thymus vulgare essential oil and its major bioactive compounds. Int. Biodeteriorat. Biodegradat. 2016;114:252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Banu S.F., Rubini D., Shanmugavelan P., Murugan R., Gowrishankar S., Karutha Pandian S., Nithyanand P. Effects of patchouli and cinnamon essential oils on biofilm and hyphae formation by Candida species. J. de Mycolog. Méd. 2018;28:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipti Mayee D., Jabez O. Rapid biodegradation and biofilm-mediated bioremoval of organophosphorus pesticides using an indigenous Kosakonia oryzae strain -VITPSCQ3 in a Vertical-flow Packed Bed Biofilm Bioreactor. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safet. 2020;192 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Bai H., Lu C., Hou C., Qiu Y., Zhang P., Duan J., Mu H. Light controllable chitosan micelles with ROS generation and essential oil release for the treatment of bacterial biofilm. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019;205:533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cansu Feyzioglu G., Tornuk F. Development of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) essential oil for antimicrobial and antioxidant delivery applications. LWT. 2016;70:104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay M., AveryaChristina A., SutherlandaDavid P. Nicolau, vitro investigation of synergy among fosfomycin and parenteral antimicrobials against carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Diagnostic Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019;95:216–220. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]