Abstract

Background

Patient registries are organized systems that use observational methods to collect uniform data on specified outcomes in a population defined by a particular disease, condition, or exposure. Data collected in registries often coincide with data that could support clinical trials. Integrating clinical trials within registries to create registry-embedded clinical trials offers opportunities to reduce duplicative data collection, identify and recruit patients more efficiently, decrease time to database lock, accelerate time to regulatory decision-making, and reduce clinical trial costs. This article describes a project of the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (CTTI) intended to help clinical trials researchers determine when a registry could potentially serve as the platform for the conduct of a clinical trial.

Methods

Through a review of registry-embedded clinical trials and commentaries, semi-structured interviews with experts, and a multi-stakeholder expert meeting, the project team addressed how to identify and describe essential registry characteristics, practices, and processes required to for conducting embedded clinical trials intended for regulatory submissions in the United States.

Results

Recommendations, suggested practices, and decision trees that facilitate the assessment of whether a registry is suitable for embedding clinical trials were developed, as well as considerations for the design of new registries. Essential registry characteristics include relevancy, robustness, reliability, and assurance of patient protections.

Conclusions

The project identifies a clear role for registries in creating a sustainable and reusable infrastructure to conduct clinical trials. Adoption of these recommendations will facilitate the ability to perform high-quality and efficient prospective registry-based clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s43441-020-00185-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Clinical trials, Randomized registry trials, Registry-embedded clinical trials, Methodology, Multi-stakeholder

Background

For decades, well-conducted clinical trials have helped assure the safety and effectiveness of drugs, biologics, and devices entering the marketplace. However, the evolution of clinical trial science and regulatory oversight has resulted in a substantial increase in the cost and complexity of clinical trials and concerns about lack of generalizability to typical clinical practice. Many believe that alternative approaches to the design and execution of clinical trials should be considered [1–4].

A registry is an organized system that uses observational methods to collect uniform data on specified outcomes in a population defined by a particular disease, condition, or exposure. At their core, registries are data collection tools created for one or more predetermined scientific, clinical, or policy purposes. Entry in a registry is generally defined either by diagnosis of a disease (disease registry) or prescription of a drug, device, or other treatments (exposure registry) [5, 6]. Registries are often used to identify and understand trends in incidence and prevalence of diseases or to observe how patients are treated in the real world, including the identification of practice changes over time [7–9].

Use of registry data for clinical trial planning is common, such as hypothesis generation, refining eligibility criteria, estimating sample size, and predicting performance of a clinical trial site. [7, 10–19] However, the ability to infer causal relations between treatments and outcomes with observational registry analyses is limited due to risks of selection bias and confounding [20–23]. Registry-embedded clinical trials offer the ability to combine the strengths of conventional clinical trials and large registries [23, 24].

The CTTI Registry Trials Project was initiated to provide recommendations for the assessment and design of registries that could be suitable for conducting registry-embedded clinical trials. The primary goal of the project was to identify and describe the essential characteristics, practices, and processes required to embed and conduct registry-based clinical trials to support regulatory decision-making. The scope of the project included the conduct of trials of drugs, devices, biologics, and procedures within the context of appropriate registries. Use of other datasets (e.g., electronic health records and claims databases) to facilitate clinical trials was outside the scope of this project. This article describes the resulting resources intended to help investigators to either (1) determine if an existing registry is suitable for conducting an embedded clinical trial or (2) design a new registry with the intention of embedding clinical trials within the registry.

Materials and Methods

CTTI is a public–private partnership founded in 2007 by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and the US FDA. Its mission is to develop and drive adoption of practices that will increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials. CTTI projects utilize multi-stakeholder project teams that follow an evidence-based methodology to identify impediments to research, gather evidence to identify gaps and barriers, explore results by analyzing and interpreting findings, and finalize solutions by developing recommendations and tools [25]. The CTTI Registry Trials Project Team consisted of stakeholders representing academia, pharmaceutical and device industries, government agencies, patient representatives, and patient advocacy organizations (https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/projects/registry-trials). Evidence gathered in the execution of this project included a reviewing published registry-based clinical trials and commentaries, a series of interviews with subject matter experts, and the output of a multi-stakeholder expert meeting. The protocol for the interviews was reviewed by the Duke University Health System IRB (Protocol ID: Pro00064484) and declared exempt from IRB review (45CFR46.101(b)).

Interviews with Subject Matter Experts

Interviews were conducted to gather expert opinions regarding, but not limited to, barriers to and potential solutions for using clinical registries for prospective clinical trials. A semi-structured interview guide was created and refined in collaboration with Research Triangle Institute (RTI) (Research Triangle Park, NC). Thirty-seven experts with knowledge and experience on the use of registry data in clinical trials were identified and invited to participate. Of the 29 respondents, 25 were prioritized by the project team and RTI to achieve the widest variety of perspectives. All 25 experts gave verbal consent to be interviewed, have their interviews digitally recorded, and be listed as interviewees within the report. To summarize responses and identify recurrent themes for each question, the responses were coded in an iterative manner. The full report is provided in the Appendix.

Expert Meeting

After completion and assessment of the interviews, an expert meeting was held on March 30, 2016, in Silver Spring, MD, which included 42 stakeholders from industry, academia, patient advocacy organizations, and government agencies. A summary of published registry-based clinical trials, findings from the expert interviews, and case examples of previously conducted randomized registry trials were presented. The attendees were asked to provide feedback on potential benefits and existing barriers to the use of registries in clinical trials and to reach a consensus on best practices to encourage the adoption of the use of clinical trials within registries. An executive summary, list of meeting participants, the agenda, and presentations can be accessed at https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/briefing-room/meetings/brave-new-world-registry-based-clinical-trials.

Following the expert meeting, the project team used the data from the evidence-gathering activities, information provided in the draft guidance on the use of real-world evidence to support regulatory decision-making for medical devices [26], and input from the expert meeting to create project recommendations and tools. Finally, the CTTI Executive Committee reviewed and approved the resources.

Results

Published registry-embedded clinical trials and commentaries and the results of the expert interviews reinforced the advantages of the combined methodology in controlling for confounding factors while also to enrolling a large and generalizable patient sample [20, 23, 24]. Registry-embedded clinical trials offer opportunities to identify highly qualified sites, reduce duplicative data collection and site workload, identify and recruit patients more efficiently, reduce patients lost to follow-up, decrease time to database lock, accelerate time to regulatory decision-making, and reduce clinical trial costs [20, 24, 27–29]. Registry type and characteristics are important for determining appropriateness for conducting clinical trials. Designing or modifying registries to accommodate clinical trials involves a number of key dimensions, including, but not limited to, informed consent, governance, interoperability, connectivity, flexibility, sustainability, data quality, regulatory, privacy, and business considerations. The need for guidance on how to assess existing registries appropriateness for, or design a new high-quality registry capable of, conducting clinical trials emerged as a recurring theme. Therefore, the project team created the following recommendations, divided into those applying to existing registries and those intended for new registries.

Recommendations

To determine if an existing registry is appropriate for embedding clinical trials:

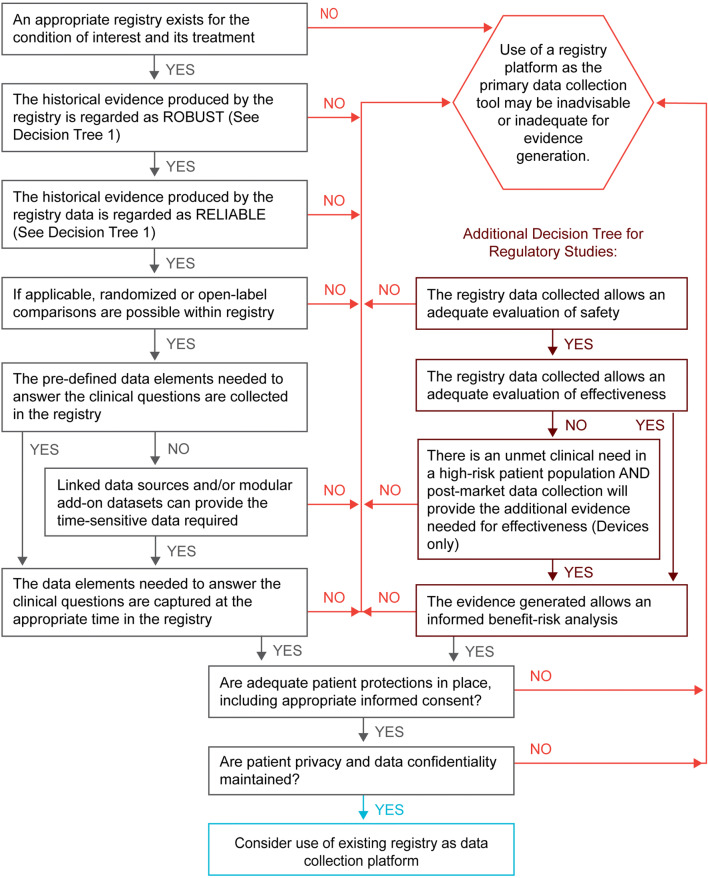

Assess whether the historical evidence generated by an existing registry has demonstrated the relevancy, robustness, and reliability necessary to provide a platform for collecting data in an embedded clinical trial to support regulatory decision-making, with assurance of patient protections (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

- Assess if an existing registry contains the elements needed to support a randomized clinical trial. Satisfaction of all the following requirements suggests that the existing registry, together with any appropriate configurable elements, may provide high-quality evidence suitable for regulatory decision-making (see Fig. 2 and Table 2):

- Are the data previously generated by the baseline registry historically regarded as robust and reliable (i.e., high-quality data)?

- Can the baseline registry and its dataset provide the core data needed to answer the question at hand (i.e., relevant or fit-for-purpose)?

- Can any processes or data not provided by the baseline registry be added or the registry reconfigured to accommodate these needs (e.g., programming to allow identification of suitable trial participants or documentation of informed consent, modular add-on datasets or linkages to other databases, and appropriate data accessibility with maintenance of patient and data privacy)?

To design a new registry suitable for embedding clinical trials, we recommend following software industry guidelines, as well as guidance documents provided by regulatory agencies, to assure that the registry complies with both industry and regulatory standards (see Table 3).

Figure 1.

Decision tree 1, existing registry—historical assessment.

Table 1.

Existing registry—historical assessment.

| Requirements | Recommendations | Suggested practices |

|---|---|---|

| Registry data must demonstrate relevancy and robustness to support regulatory decision-making |

Data are relevant Data are adequate in scope and content Data are generalizable: Registry reflects high site and patient participation rates compared with total population Data are robust—acceptable for use in one or more of the following Validated risk prediction Quality assurance Performance improvement Benchmarking Informing practice guidelines Post-market surveillance Generating peer-reviewed publications Comparative effectiveness research |

Evaluate if data generated by an existing registry are adequate for evaluating clinical outcomes or supporting regulatory decision-making Assess whether data and evidence that are generated can address the question at hand (i.e., fit for purpose) Connectivity: Establish whether there are linkages or the ability to link to other existing datasets for additional data not captured directly in the registry Data should be suitable for adequate statistical analysis Data should be interpretable, i.e., evidence derived from analysis of de-identified aggregate data should be sufficient to allow for regulatory decision-making |

| Registry data must reliably be able to support regulatory decision-making | Design: The registry should be designed to capture reliable data from real-world practice (no protocol-driven treatment) |

A standard operating procedure document should exist that defines the processes and procedures for data capture and management The system should have a basic validation package to assure that the software acts as intended |

| Patient population: The patient population should be limited to those with specific diseases, conditions, or treatment exposure(s) |

The patient population for the registry is associated with a specific disease, condition, family of procedures (e.g., orthopedic surgery), or treatment exposure(s) Inclusion and exclusion criteria should be clearly defined (e.g., total population or population subset) |

|

| Data collection forms: The data collection forms should be standardized |

The existing data elements should be fixed and predefined There should be an audit trail for any changes The forms should use standard and uniform data definitions |

|

| Datasets: Data elements should be able to be mapped to industry standards to allow for more direct comparison of data analyses | Documentation should be available that describes the data elements and datasets | |

| Timing of endpoints/outcomes: The timepoints of each endpoint/outcome in the data collection form should be documented | Evaluate the ability to calculate timing of treatment and treatment outcome (e.g., stroke at discharge or at 30 days post index procedure) | |

| Timing of data collection: Data collection/entry can occur at any time | The system should be live 24/7 and web-based | |

| Data completeness and accuracy: Data should be complete, accurate, and attributable |

Missing data should be minimized and statistically assessed Assure processes are in place for data collection and entry with documented training The system should allow identification of the data originator (e.g., person[s] performing procedure[s]), data source (e.g., point of care, EHR, procedural record), and data entry person Data logic checks should be included at the time of data entry Processes should be in place to assure accuracy of the data |

|

| Registry has assurance of patient protections |

Documentation of informed consent or IRB waiver of informed consent is needed for access to the data (e.g., by investigators, patients, regulators) Patient privacy must be assured: Assess for use of de-identified data vs. line-item data |

Access to the data needs to be supported by patient informed consent or IRB waiver of informed consent Use a single IRB of record where possible with a broad-use informed consent document Data encryption and security protections should be in place Control/ownership of proprietary data should be addressed If informed consent is waived by the IRB, additional patient protections must be in place to share line-item patient level data (i.e., HIPAA consent or waiver for research) |

EHR electronic health record, IRB investigational review board, vs versus

Figure 2.

Decision tree 2, existing registry—suitability assessment.

Table 2.

Existing registry—suitability assessment.

| Requirements | Recommendations | Suggested practices |

|---|---|---|

| Registry must be able to support the proposed clinical trial |

The existing registry is appropriately focused on the patient population, disease, and intervention of interest Historically, the evidence collected within the registry is robust (see Table 1) Historically, the evidence collected within the registry is reliable (see Table 1) |

See Table 1 for recommended assessment of a registry for use as the data collection platform for conducting prospective randomized clinical trials, including assessment of applicability, strengths, and weaknesses based on historical use |

| Registry data must be fit for purpose (relevant) | Assignment of therapy: Processes must be integrated for identification, assignment, and documentation of eligible participants |

Assess ability to incorporate methods required for identification of study-appropriate patients Evaluate ability to embed processes for randomization into registry workflow Evaluate ability to embed processes for assurance and documentation of informed consent |

| Adequacy of data: Assure available data elements collected in the registry generate the information/evidence needed to answer the question at hand |

Supplement missing and/or longitudinal data elements needed for evidence generation through the use of modular add-on datasets or linkages to other datasets The eventual goal should be linkage to the EHR for procedural and long-term data collection and incorporation of data collection into the normal workflow |

|

| Ensure availability of appropriate data and analysis tools |

Identify analysis tools necessary to allow the data collected within the registry to generate interpretable results (i.e., evidence) Develop pre-specified endpoints and a statistical analysis plan Consider suitability of the totality of the data (i.e., body of evidence supporting the clinical benefit-risk assessment) |

|

| Registry data must be of sufficient quality (reliable) to support a prospective clinical trial | Data collection must be sufficient to support regulatory decision-making | Assess the adequacy of the registry’s data collection form as a CRF |

| Data should be complete and accurate |

Assure appropriately trained personnel are available at study sites for data collection and abstraction Registry should incorporate use of a uniform data dictionary Registry should incorporate appropriately defined timing for collection of key data points |

|

| Employ adequate data quality assurance procedures | Assess the need for enhanced auditing and monitoring of data to assure completeness and accuracy | |

| Establish processes for accountability of study patients |

Minimize patient withdrawals Minimize patients lost to follow-up |

|

| Source data should be available for key data elements; site-reported data without independent assessment may not provide enough accuracy for key outcomes in randomized trials |

Use independent assessors for key data, such as: Independent blinded core labs when needed for data interpretation Clinical Events Committee when needed for adjudication of key outcomes and adverse event data |

|

| Registry data and evidence generated must be accessible, with adequate provisions for patient privacy and data confidentiality | Establish data availability to the sponsor and/or clinical investigators, with considerations for patient privacy and data confidentiality |

Assure informed consent adequately describes data accessibility and maintenance of patient privacy and data confidentiality Assure accurate identification of all study-enrolled patients within registry Assure ability to sequester records of study-enrolled patients (i.e., patient privacy and data confidentiality) Define timing and timeliness of sequestered record transfer for sponsor (i.e., product-specific proprietary data) Define timing and timeliness of data transfer to analytic dataset |

| Ensure availability of line-item data to regulators | Define timing and timeliness of data and analysis transfer to regulators | |

| Establish necessary associations to other data sources |

Determine and provide the necessary linkages to other registries, administrative or government databases, EHRs, etc. Identify new records generated in linked databases for longitudinal follow-up of patients enrolled in research studies |

|

| Develop plan for data dissemination |

Define timing and timeliness of data transfer to the study sponsor(s) for dissemination of outcome analyses to study participants and participating physicians As appropriate, define process for release of data and analyses to other stakeholders (e.g., clinicaltrials.gov, payers, etc.) |

CRF case report form, EHR electronic health record

Table 3.

Designing a new registry with the capability of embedding a clinical trial.

| Requirements | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Clearly articulate the concept of the registry in a transparent manner | The registry design document should articulate the vision, mission, reason, and value proposition of the registry |

| Define and describe participant characteristics |

The registry must minimize barriers for inclusion, thus maximizing inclusion of those having the disease/condition to be studied. The registry must allow for disparate treatment modalities, including drugs, biologics, devices, and combination products |

| Select clinically relevant data elements |

Data elements should efficiently capture and convey information in order to provide evidence based on meaningful clinical endpoints and outcomes Definitions used for data elements should conform to recognized standards and nomenclature There must be the ability to: Document informed consent Document randomization/assignment of patients Configure/add additional data elements There should be the ability to: Identify clinically eligible patients for trial participation Accept external data if not collected in the registry (e.g., EHR, reliable external datasets) Measure product performance Document adjudication or core lab determinations for key trial outcomes |

| Data collection processes must be systematic, consistent, reproducible, and reliable |

The registry must be 21CFR Part 11 compliant Data traceability must include attributability of data originators and data entry personnel, with date and time stamps for all transactions Data should be usable for clinical care purposes Data collection should be integrated into the process of care All processes must be supported by documented training and education of those entering data (e.g., data managers, data entry personnel, and registry participants) |

| Assure the registry conforms to informatics standards |

The registry should support: Publication of the data dictionary Defined and semantic interoperational data elements Use of common data elements/controlled vocabularies Use of a common data model Use of the FDA’s UDI, if device Referential integrity via use of single source (e.g., RxNorm, GUDID) |

| Evaluate and assure data quality across multiple dimensions | The data must be contemporaneous, accurate, legible, consistent, complete, and reliable |

| Patient protections must be assured |

Assure patient protections by including the following elements: Documentation of appropriate informed consent Data confidentiality policies System security compliance and security audits Published explanation of intentional data uses Training of data originators (i.e., data entry personnel) and managers IRB oversight and review |

| Assure registry design is valid across multiple stakeholder analyses |

Data should support pre- and post-market regulatory as well as other stakeholder evidentiary needs Data ownership and access to trial-specific data should be established prior to the start of an embedded trial (e.g., processes for sequestration of trial data from the full registry data and access limitations prior to product approval). For site-based users, the registry should support: Quality assurance and performance improvement Risk reduction Benchmarking based on risk-adjusted outcomes Anticipate distributed query and aggregate analysis |

| Incorporate patient-reported information within the registry |

Provide guidelines for participants in reporting to the registry Provide technologies/structures to support the systematic, periodic query of participants |

CFR code of federal regulations, UDI unique device identifier

Discussion

Embedding clinical trials into registries can contribute to the transformation of the clinical research enterprise to facilitate lower-cost, high-quality evidence generation. We report the results of a project about registry-based clinical trials including a literature search, in-depth interviews, a convened meeting of experts, and collaborative discussions of a multi-stakeholder project team. We have compiled these findings and developed recommendations for determining the suitability of an existing registry, or designing a new registry, for the purposes of conducting registry-based clinical trials. We have determined that registries can be well suited to facilitate clinical trials if they are relevant, robust, reliable, and respectful of patient privacy and data confidentiality.

The recommendations and tools presented here are intended to facilitate the path forward to the effective and efficient use of registries as reusable platforms for evidence generation and to encourage their use, as an alternative to creating de novo case report forms and databases for each new clinical trial. The recommendations are meant to identify key best practices and principles. Of note, these recommendations are not intended to be either a mandatory or exhaustive checklist. We recognize that some registries will not be suitable for conducting embedded clinical trials, but should continue to be used as successful tools to facilitate clinical trials through activities such as identifying and recruiting patients, conducting trial feasibility assessments, and reducing the amount of baseline and/or follow-up data that need to be collected for a clinical trial.

Collecting most or all data needed for a clinical trial from a registry is possible in some cases, i.e., registry is the primary data collection tool. However, a review of randomized registry-based randomized trials found that half used more than one registry [23]. Linkage of registries for registry-embedded trials is commonly conducted in countries where unique patient identifiers are used in national health registries [24, 30–33]. However, in situations where additional data sources are not available or the available registry data lack sufficient granularity (e.g., depth, definitional uncertainty, or insufficient temporal assessment) for clinical or regulatory purposes, targeted modular add-on data can be designed for use within the registry or as a separate case report form, to collect the additional essential data needed to reach a clinical or regulatory decision. This combined registry and case report form strategy was used in both the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) Registry Treat to Target (T2T) and Study of Access site For Enhancement of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Women (SAFE-PCI for Women) trials. [29, 34].

Regulatory agencies have long accepted registry and other post-marketing data sources to collect safety information, such as surveillance for adverse events and conduct of post-approval studies [35–39]. Furthermore, data from registries can be used to accelerate expansion of patient access to an intervention, and generate evidence to identify potential new label indications [14, 40–42]. Recently, the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has signaled its commitment to develop policies regarding use of real-world data (RWD) sources—including registries—to support efficacy claims [43–47]. Guidance for devices, and draft guidance for drugs and biologics, regarding use of RWD and real-world evidence for regulatory purposes have been released [26, 48]. These recommendations were designed to assist in assessing the acceptability of data and evidence from registries that would meet the standard of acceptability for regulatory submissions in the United States. Researchers and those engaged with registry-embedded trial development are encouraged to interact with regulators early in study planning to ensure that planned data collection will be acceptable for regulatory submission.

The following limitations apply to the project and recommendations. The scope of the project was registries only. However, registries can be populated from other data sources such as electronic health records or claims data [49, 50]. The recommendations provided, particularly for assessment of historical evidence (Table 1), are applicable to assessment of other sources of real-world data whether they are being used to populate a registry, as an additional linkage to a registry, or alone [51]. These recommendations do not explore the costs of using registries for clinical trials, as they focus on acceptability. Although per-patient costs have shown to be lower in registry-embedded trials, there are costs associated with access to the data, building add-ons for a trial, and technical work required to establish connections to other datasets [13, 20, 28, 52]. These costs are an additional consideration when assessing registry-embedded trial feasibility. Greater efficiency and cost savings are possible when a registry or group of registries may be reused for multiple trials. Finally, these recommendations apply to the suitability of registry-embedded trial data for regulatory decision-making in the United States. Recently, the European Network for Health Technology Assessment (HTA) released a tool and vision paper to assess the quality of registry data and acceptability for HTA and regulatory purposes [53].

Conclusions

The CTTI Registry Trials Project has taken an evidence-based and highly collaborative approach to accomplishing its goal of providing recommendations for registry assessment and design regarding their suitability for conducting embedded clinical trials. We anticipate that these recommendations will encourage clinical trial stakeholders to collaborate effectively to increase utilization of prospective patient registries to facilitate high quality, efficient, registry-embedded clinical trials.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Teresa McNally, PhD, and Karyn Hede, MS, for editorial assistance in the development of this article. Both are employees of Whitsell Innovations, Inc., Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and received no compensation for their work on this article other than their usual salary.

Funding

This work was supported by the US Food and Drug Administration (Grant Number R18FD005292) awarded to Duke University as the host of CTTI. Views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services, nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the US government. Additional support is provided by CTTI member organizations, whose annual fees support CTTI infrastructure expenses and projects. https://www.ctti-clinicaltrials.org/membership.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Arlene Swern is an employee and stockholder for Celgene Corp. E. Dawn Flick is a current employee of Celgene Corp., and a past employee of Genentech, Inc. Nicolle Gatto was an employee and shareholder of Pfizer at the time of manuscript submission, she is a current employee of Aetion, Inc. John Laschinger was at the U.S. FDA at the time of the project, he is a current employee of W. L. Gore & Associates. Emily Zeitler was at the Duke Clinical Research institute at the time of the project, she is a current employee of the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College.

References

- 1.DiMasi JA, Hansen RW, Grabowski HG. The price of innovation: new estimates of drug development costs. J Health Econ. 2003;22(2):151–185. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(02)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisfeld N, English R, Claiborne AB. In: Envisioning a Transformed Clinical Trials Enterprise in the United States: Establishing An Agenda for 2020: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC); 2012. [PubMed]

- 3.Morgan S, Grootendorst P, Lexchin J, Cunningham C, Greyson D. The cost of drug development: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2011;100(1):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrigan-Curay J, Sacks L, Woodcock J. Real-world evidence and real-world data for evaluating drug safety and effectiveness. JAMA. 2018;320(9):867–868. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gliklich RE, Dreyer N, Leavy MB. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user’s guide. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB, editors. Registries for Evaluating Patient Outcomes: A User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency . Scientific Guidance on Post-authorisation Efficacy Studies, 2015. London: European Medicines Agency; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashley L, Jones H, Thomas J, et al. Integrating cancer survivors’ experiences into UK cancer registries: design and development of the ePOCS system (electronic Patient-reported Outcomes from Cancer Survivors) Br J Cancer. 2011;105(Suppl 1):S74–S81. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed B, Piper WD, Malenka D, et al. Significantly improved vascular complications among women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the Northern New England Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(5):423–429. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.860494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauerman HL, Rao SV, Resnic FS, Applegate RJ. Bleeding avoidance strategies. Consensus and controversy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peelen L, Peek N, de Jonge E, Scheffer GJ, de Keizer NF. The use of a registry database in clinical trial design: assessing the influence of entry criteria on statistical power and number of eligible patients. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(2–3):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig JC, Webster AC, Mitchell A, Irwig L. Expanding the evidence base in transplantation: more and better randomized trials, and extending the value of observational data. Transplantation. 2008;86(1):32–35. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817d5095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Wright NC, Xie F, et al. Use of health plan combined with registry data to predict clinical trial recruitment. Clin Trials. 2014;11(1):96–101. doi: 10.1177/1740774513512185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao SV, Hess CN, Barham B, et al. A registry-based randomized trial comparing radial and femoral approaches in women undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SAFE-PCI for Women (Study of Access Site for Enhancement of PCI for Women) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(8):857–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll JD, Edwards FH, Marinac-Dabic D, et al. The STS-ACC transcatheter valve therapy national registry: a new partnership and infrastructure for the introduction and surveillance of medical devices and therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowling NM, Olson N, Mish T, Kaprakattu P, Gleason C. A model for the design and implementation of a participant recruitment registry for clinical studies of older adults. Clin Trials. 2012;9(2):204–214. doi: 10.1177/1740774511432555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen VJ, Greene ME, Bragdon MA, et al. Registries collecting level-I through IV Data: institutional and multicenter use: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg. 2014;96(18):e160. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Blieck EA, Augustine EF, Marshall FJ, et al. Methodology of clinical research in rare diseases: development of a research program in juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (JNCL) via creation of a patient registry and collaboration with patient advocates. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabbagh MN, Tariot PN. Commentary on “a roadmap for the prevention of dementia II. Leon Thal Symposium 2008.” A national registry to identify a cohort for Alzheimer’s disease prevention studies. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(2):128–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achiron A, Givon U, Magalashvili D, et al. Effect of Alfacalcidol on multiple sclerosis-related fatigue: a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Mult Scler. 2015;21(6):767–775. doi: 10.1177/1352458514554053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James S, Rao SV, Granger CB. Registry-based randomized clinical trials–a new clinical trial paradigm. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(5):312–316. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ieva F, Gale CP, Sharples LD. Contemporary roles of registries in clinical cardiology: when do we need randomized trials? Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2014;12(12):1383–1386. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.982096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, Ezekowitz JA. Similarities and differences in patient characteristics between heart failure registries versus clinical trials. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10(4):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathes T, Buehn S, Prengel P, Pieper D. Registry-based randomized controlled trials merged the strength of randomized controlled trails and observational studies and give rise to more pragmatic trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;93:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li G, Sajobi TT, Menon BK, et al. Registry-based randomized controlled trials-what are the advantages, challenges, and areas for future research? J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;80:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corneli A, Hallinan Z, Hamre G, et al. The clinical trials transformation initiative: methodology supporting the mission. Clin Trials. 2018;15(1_suppl):13–18. doi: 10.1177/1740774518755054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Use of Real-World Evidence to Support Regulatory Decision-Making for Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov/media/99447/download. Published 2017. Accessed 25 Nov 2019.

- 27.Thuesen L, Jensen LO, Tilsted HH, et al. Event detection using population-based health care databases in randomized clinical trials: a novel research tool in interventional cardiology. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5:357–361. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S44651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauer MS, D’Agostino RB., Sr The randomized registry trial–the next disruptive technology in clinical research? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1579–1581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess CN, Rao SV, Kong DF, et al. Embedding a randomized clinical trial into an ongoing registry infrastructure: unique opportunities for efficiency in design of the Study of Access site For Enhancement of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Women (SAFE-PCI for Women) Am Heart J. 2013;166(3):421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frobert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1587–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gotberg M, Christiansen EH, Gudmundsdottir IJ, et al. Instantaneous wave-free ratio versus fractional flow reserve to guide PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(19):1813–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedberg S, Olbers T, Peltonen M, et al. BEST: bypass equipoise sleeve trial; rationale and design of a randomized, registry-based, multicenter trial comparing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with sleeve gastrectomy. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;84:105809. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) BMJ. 2011;342:d442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrold LR, Reed GW, Harrington JT, et al. The rheumatoid arthritis treat-to-target trial: a cluster randomized trial within the Corrona rheumatology network. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mack MJ, Brennan JM, Brindis R, et al. Outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the United States. JAMA. 2013;310(19):2069–2077. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta AB, Chandra P, Dalal J, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of BioMatrix™-Biolimus A9™ eluting stent: the e-BioMatrix multicenter post marketing surveillance registry in India. Indian Heart J. 2013;65(5):593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oza SR, Hunter TD, Biviano AB, et al. Acute safety of an open-irrigated ablation catheter with 56-hole porous tip for radiofrequency ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: analysis from 2 observational registry studies. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25(8):852–858. doi: 10.1111/jce.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green A, Ramey DR, Emneus M, et al. Incidence of cancer and mortality in patients from the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(10):1518–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jankovic J, Adler CH, Charles PD, et al. Rationale and design of a prospective study: Cervical Dystonia Patient Registry for Observation of OnaBotulinumtoxinA Efficacy (CD PROBE) BMC Neurol. 2011;11:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genentech. FDA Approves Expanded Indication for ACTEMRA® in Rheumatoid Arthritis. www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14187/2012-10-12/fda-approves-expanded-indication-for-act. Accessed 7 July 2016.

- 41.Matsukage T, Yoshimachi F, Masutani M, et al. A new 0.010-inch guidewire and compatible balloon catheter system: the IKATEN registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73(5):605–610. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell ME, Friedman MI, Mascioli SR, Stolz LE. Off-label use: an industry perspective on expanding use beyond approved indications. J Interv Cardiol. 2006;19(5):432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2006.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman RE. Real-world evidence—what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2293–2297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1609216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherman RE, Davies KM, Robb MA, Hunter NL, Califf RM. Accelerating development of scientific evidence for medical products within the existing US regulatory framework. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(5):297–298. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuren J, Califf RM. Need for a national evaluation system for health technology. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1153–1154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faris O, Shuren J. An FDA viewpoint on unique considerations for medical-device clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1350–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1512592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Framework for FDA’s Real-World Evidence Program. https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download. Published 2018. Accessed 22 May 2019.

- 48.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Submitting Documents Using Real-World Data and Real-World Evidence to FDA for Drugs and Biologics. Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/124795/download. Published May 2019. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- 49.Platt R, Takvorian SU, Septimus E, et al. Cluster randomized trials in comparative effectiveness research: randomizing hospitals to test methods for prevention of healthcare-associated infections. Med Care. 2010;48(6):S52–S57. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbebcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. Accessed 27 Nov 2019.

- 51.Gliklich RE, Leavy MB. Assessing real-world data quality: the application of patient registry quality criteria to real-world data and real-world evidence. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s43441-019-00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang SS, Septimus E, Kleinman K, et al. Targeted versus universal decolonization to prevent ICU infection. New Eng J Med. 2013;368(24):2255–2265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NU, French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé), (France). H. Vision Paper on the Sustainable Availability of the Proposed Registry Evaluation and Quality Standards Tool (REQueST). https://eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/EUnetHTAJA3_Vision_paper-v.0.44-for-ZIN.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed 26 Nov 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.